THE COPING ROUES OF OFFSPRING OF ALCOHOL DEPENDANTS: THEIR MEASUREMENT AND VALIDITY

A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of

the requirements for the degree of Master of Clinical Psychology

by

Cindy Devine

Department of Psychology Australian National University

STATEMENT

I hereby certify that this sub-thesis is my own work unless otherwise stated.

C J Devine

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to express warm thanks to my supervisor, Dr Valerie Braithwaite, who showed much patience and interest in this study, and whose tolerance and readiness to help went beyond the call of duty.

I am also grateful to the individuals who helped in my efforts to access adolescents for the study.

Many thanks to the numerous adolescents who gave up their time to complete questionnaires.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Acknowledgements i

Table of Contents ii

List of Tables v

Abstract vii

CHAPTER Is INTRODUCTION 1

HISTORICAL OVERVIEW

. Physical Health Status . Cognitive Abilities

. Social and Emotional Adjustment

EVOLUTION OF A FAMILY PROCESS APPROACH 10 . Application of a Family Systems Approach

to the Effects of Parental Alcohol

Dependency 13

THE COPING ROLES 16

RESILIENCE AND MODERATING VARIABLES 22 . Positive Adjustment Among COAs 22

EXPLANATION OF ADJUSTMENT 25

. Stress and Coping Models 25

. Variability in Family functioning 27

. Moderating variables 29

. Coping Strategies 31

THE PRESENT STUDY 33

RESEARCH GOALS 38

CHAPTER 2: METHOD 39

RESPONDENTS 39

MEASURES: PARENTAL ALCOHOL DEPENDENCY 40 . Children of Alcoholics Screening Test

(CAST) 40

. Children of Alcoholics Families

Instrument (CAF) 42

. Frequency of Parental Drinking

(BEST Item) 43

vo

co

Page

MEASURES: FAMILY DISORGANIZATION 44

. Family Deliberateness 45

. Emotional Support 45

. Family Cohesiveness 46

MEASURES: COPING ROLE INSTRUMENT 47

MEASURES: WELL-BEING 4 8

. General Health Questionnaire 12

(GHQ-12) 48

. Life Satisfaction Scale 49

PROCEDURE 50

RESULTS 52

CHAPTER 3. INTERRELATIONSHIPS AMONG THE INDEPENDENT VARIABLES AND MEASUREMENT OF THE COPING

ROLES 53

INTERRELATIONSHIPS AMONG DRINKING MEASURES 54 . Demographic correlates of the drinking

measures 55

INTERRELATIONSHIPS AMONG FAMILY

DISORGANIZATION VARIABLES 56

INTERRELATIONSHIPS AMONG DRINKING MEASURES AND FAMILY DISORGANIZATION

VARIABLES 58

MEASUREMENT OF THE COPING ROLES 60

REVISED TYPOLOGY 64

. Demographic correlates of the revised

coping roles 68

RELATIONSHIP OF COPING ROLES WITH ADJUSTMENT 69 CHAPTER 4: PREDICTING ROLE TYPE FROM FAMILY

CHARACTERISTICS AND PARENTAL

DRINKING 72

INTERRELATIONSHIPS OF COPING ROLES WITH FAMILY

VARIABLES AND PARENTAL DRINKING 72

Page

CHAPTER 5: DISCUSSION 81

VALIDITY OF THE COPING ROLES 82

SOCIO-DEMOGRAPHIC CORRELATES OF ROLE CHOICE 84 PARENTAL DRINKING AND ADOPTION OF COPING

ROLES 86

CONTRIBUTION OF FAMILY DISORGANIZATION TO

ADOPTION OF COPING ROLES 90

RELATIONSHIP OF COPING ROLES TO

WELL-BEING 91

LIMITATIONS 93

CONCLUSION 95

REFERENCES 97

APPENDIX 1 - QUESTIONNAIRE

APPENDIX 2 - ITEMS REPRESENTING THE REVISED TYPOLOGY

LIST OF TABLES

Page

Table 1 Survival roles of COAs and

associated social settings. 19

Table 2 Frequencies of response to

CAF item categories. 43

Table 3 Frequencies of response to

BEST item categories. 44

Table 4 Intercorrelations of the three

drinking measures. 54

Table 5 Correlations of the three

drinking measures with age, sex

and employment status. 56

Table 6 Intercorrelations of the family

disorganization variables. 57

Table 7 Correlations of the family

disorganization variables with age,

sex and employment status. 58

Table 8 Intercorrelations of the parental

drinking measures (CAST, CAF,

BEST, and NEWCAST) with the family disorganization variables (emotional support, cohesiveness and

deliberateness). 59

Table 9 Means, standard deviations, alpha

reliability coefficients and

interscale correlations for the 5 coping roles of nonCOAs (CAST<2)

and COAs (CAST>2). 61

Table 10 Means, standard deviations, alpha

reliability coefficients and interscale correlations of the 5 coping roles for the group as a

whole. 63

Table 11 Rotated factor structure of the 5

coping roles 65

Table 12 Means, standard deviations, alpha

reliability coefficients and interscale correlations for the

Page

Table 13 Intercorrelations of the 5 coping

roles with sex, age and employment

status. 68

Table 14 Intercorrelation of the coping roles

with the GHQ and Life Satisfaction

Scale. 70

Table 15 Intercorrelations of the 5 coping roles

with parental drinking and family

disorganization. 73

Table 16 Regressing the hero role on

demographic and family

characteristics and parental

drinking. 75

Table 17 Regressing the lost child role on

demographic and family

characteristics and parental

drinking. 76

Table 18 Regressing the mascot role on

demographic and family

characteristics and parental

drinking. 77

Table 19 Regressing the scapegoat role on

demographic and family

characteristics and parental

drinking. 78

Table 20 Regressing the placater role on

demographic and family

characteristics and parental

[image:8.558.66.519.33.787.2]ABSTRACT

In an attempt to bridge the gap between clinical and empirical research on the children of alcohol dependents

CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION

The risks of parental alcohol dependency to the well-being of their offspring has been well documented in recent years (Wolin et a l ., 1979; Moos & Billings, 1982; Adler & Raphael, 1983; Hesselbrock, 1986; Russell et al., 1985; West & Prinz, 1987; Roosa et al., 1988; Reich et al. , 1988; Velleman & Orford, 1990) . That there exists a potential for the development of a range of behavioural, emotional and psychosomatic problems in these children remains undisputed within both the clinical and empirical literature. Nevertheless, the large body of empirical evidence which has arisen on children of alcohol dependants has been contradictory at times due to disparity in samples and methods employed to examine a wide range of dependent variables (Adler & Raphael, 1983; Blane, 1988; Burk & Sher, 1988) . As a result comparison of findings has been difficult, and the body of research remains fragmented without a unifying theoretical or conceptual framework to guide future research.

drinking or 'alcoholism' (Velleman & Orford, 1990). Many of the studies reviewed by West and Prinz (1987) overlooked other adverse familial and environmental factors which may accompany parental drinking and may influence child outcomes. The relative importance of family disharmony and disruption which so often accompanies alcohol abuse, as against the impact of the alcohol abuse itself, has been considered all too rarely (Adler & Raphael, 1983). The possibility of positive outcome with appropriate family support is also often ignored. As a consequence, current literature provides us with facts about outcomes for children of alcohol dependants (COAs), but does not explain the process by which having a dependent parent can lead to psychological problems.

resulting in dysfunctional behaviours when the child matures and leaves home.

These coping strategies have been described as "survival roles", each with a characteristic set of behaviours. COAs are said to take on one or more of these roles as a defence against family stress caused by a problem drinking parent. Principles of recovery are the same for family members as for the alcohol dependent member, and according to this model, all offspring of alcohol dependants are adversely affected. Arising simultaneously with this now popular model has been a clinical COA movement aimed at offering a variety of psychosocial services to reduce current levels of distress and dysfunction, and to prevent future negative outcomes.

The many programmes and activities developed as a result of the writings of clinicians such as Wegscheider and Black, have occurred largely independently of research on COAs. Although there have been serious attempts in more recent years to bring research and practice into harmony (Black et al., 1986; Rhodes & Blackham, 1987; Velleman & Orford,

chosen to ignore the typologies described completely (West & Prinz, 1987), while others have called for research to evaluate their scientific merit (Blane, 1988; Burk & Sher, 1988; Woodside, 1988). Until recently, empirical studies had not attempted to examine the types of COAs Wegscheider and Black have identified on the basis of clinical experience. A recent investigation of the validity of the survival roles (Rhodes & Blackman, 1987) has produced inconclusive evidence for the existence of the typologies described by Wegscheider and Black, among the offspring of problem drinkers. Empirical support for the existence of these coping strategies or survival roles has, therefore, yet to be found through rigorous research.

stress during their upbringing, and that in many cases other factors inside and outside the family may have operated to buffer the stress to which a child has been exposed. The term COA is currently defined broadly to refer to any person, adult or child, who has a parent identified in any way as having a significant problem related to alcohol use (Russell, et al., 1985). This broad description implies negative outcome for all COAs. This is despite evidence from a large body of literature which suggests that a number of COAs experience positive outcomes (eg. Heller, et a l ., 1982; Russell et al., 1985; Werner, 1986; Barnard & Spoentgen,

1987) .

Most recently, approaches to studies of resiliency in children from other kinds of disorganized family environments have been applied to the children of alcohol dependants. This has led to increasing support over the past decade for the view that some children are protected from the adverse effects of parental alcohol dependency.

alcohol abuse, as distinct from other family environment factors, in the adoption of coping roles.

HISTORICAL OVERVIEW

The characteristics of children that can be linked with parental alcohol dependency have since been extensively documented. Psychological research has yielded a large body of data about COA health status, cognitive abilities, emotional consequences and adaptive behaviours (Woodside, 1988). There have been consistent reports in the literature of the increased likelihood that offspring will develop alcohol problems (Goodwin & Guze, 1974; Winoker et al. , 1970; Cotton, 1979; Rydelius, 1981), disrupted interpersonal relationships (Chafetz, 1979; Franks & Thacker, 1979), and disturbances in emotional and physical well-being (Hughes, 1977; Moos & Billings, 1982; Matajcek & Baueriva, 1981). While a detailed description of the findings of this large body of research would be prohibitive in the present context, the more robust findings will be briefly outlined.

Physical Health Status

Intrauterine effects of maternal alcohol consumption include physical deformities, central nervous system disorders, behaviour problems, physical and/or mental retardation

As infants, COAs may be inclined to feeding problems, vomiting and incessant crying (Nylander, 1960; Cork, 1969). As preschoolers, they have been found to be 65 percent more likely to be ill than other youngsters (Putnam, 1985) and to exhibit a range of physical complaints such as migraines, tiredness, sleep problems, asthma and enuresis

(Schneiderman, 1975; Steinhausen et al., 1982). Heightened sensitivity to noise, bright lights, heat and cold have also been documented (Fine et al., 1976). A review of the literature on COAs by West and Prinz (1987) revealed that three out of five studies (Beik, 1981; Roberts & Brent, 1982; Steinhausen et al. , 1982) reported a tendency for COAs, especially females, to present with health problems at a higher rate than those from other families. In these studies, however, other family stressors were not controlled or assessed as factors which also may have accounted for variability in health status among these children.

Cognitive Abilities

dependants have been found to exhibit a lessened ability to categorize, organize and plan (Schulsinger et al., 1985), and to experience deficits in perceptual-motor ability, memory, and language processing (Tarter et al., 1984; Schaeffer et al., 1984). Greater impulsivity, poorer verbal skills and more disrupted schooling have also been noted amongst adolescent COAs compared with controls without a problem drinking parent (Knop et al., 1985). Again the relative contribution of parental alcohol dependency is difficult to estimate since factors such as conduct disorder, delinquency, marital discord and truancy may impact on school performance.

Social and Emotional Adjustment

teenagers from alcohol dependent family environments were twice as likely to receive psychiatric treatment for conduct disorders and anxiety-depressive symptoms (Herjanic, 1971). West and Prinz (1987), in a review of the literature on COAs, concluded that of all psychopathological symptomatolgy identified among COAs the most prominent form was the externalizing problems of restlessness and inattention, conduct problems, and poor academic performance.

EVOLUTION OF A FAMILY PROCESS APPROACH

Information such as the above has been important in providing descriptions of the effects of parental alcohol dependency on their offspring. The contribution of clinicians has been to delineate models explaining the dynamics at work in the family.

members has been achieved in more recent years through the application of an interactive (systems) approach. The primary contention of this approach is that an adequate understanding of dysfunctional behaviour cannot be achieved independent of an adequate understanding of significant social contexts in which members develop and function (Jacob et al., 1989).

Systems theory asserts that if the behaviour of an individual is to be understood we must consider the significant group or system of which that individual is a part, the relationships within the group and the

individual's contribution to maintaining the system (Wilson, 1982) . According to this view, the family unit is the focus of intervention, as each member is interdependent on the other. This interdependency suggests that any change in one part of the family will result in changes in the other parts, since a family system will always try to keep itself balanced.

necessarily imply that the family is functioning well. The family might, for example, include as part of this stabilization pattern a piece of chronic psychopathology (such as alcohol dependency) . However, regardless of the quality of stabilization, there are strong forces within families that operate to maintain homeostatis and appear to resist changes in family level behaviour.

An important tenet of systems theory is that the family evolves a structure of roles through which its functions are achieved. These are social roles (eg. housekeeper, breadwinner, parent, child) and emotional roles (eg. comforter, calm decision maker, trouble maker) which are necessary for the working of the family system and for maintenance of emotional homeostasis (Wilson, 1982). These roles are considered to be the property of the system, not of the individuals who play them. Thus, if one member of the system is unable or unwilling to play his or her allotted roles, another member must take over if the system is to continue functioning normally. Gradually, family members settle into roles which help to maintain the often dysfunctional nature of the family interaction and to inhibit each individual's positive growth (Perkins, 1989).

that an individual's behaviour is a response to a complex set of regular and predictable "rules" governing family members, though these rules may not be consciously known to them. Family rules determine the functions of each person, the relationship between persons, the goals toward which they are heading, how they intend to get there, and what will be required and forbidden along the way.

Application of a Family Systems Approach to the Effects of Parental Alcohol Dependency

insecurity, and the inconsistent behaviour of the dependent parent leads to an atmosphere of unpredictability. Household rules and emotional climate change abruptly according to the dependant's level of intoxication

(Woodside, 1988).

The view of alcohol dependency as a "family disease" has arisen from this family systems perspective. Wegscheider (1976) proposes that it is in response to the disease of alcoholism that family members unconsciously play a role that counterbalances the dependant's behaviour maintaining equilibrium. The longer lasting and more subtle the dependency, the greater the chance of its acceptance as the norm for this system. Homeostasis, rigidly protected by the system's distorted reality, delusions, and denial (or family rules), will be maintained unless it becomes disrupted by a crisis.

and stability for themselves. Black (in Ackerman, 1986) describes the roles as compensatory changes or reactions to parental alcohol dependency which allow children to maintain a sense of balance or homeostasis. These roles have been labelled "survival roles", since they serve the function of helping an individual and the system to survive by ensuring the least amount of personal stress.

Since parental alcohol dependency is a secret within and outside the family, offspring are made partners in the family's denial that a parent is drinking (Woodside, 1986). Role adoption, therefore, also involves denial and enables avoidance of real issues which are emotionally distressing.

the family system, the more rigid and static it becomes, and the less flexible it is in readapting to life's challenges. Rigidity and inflexibility within the alcohol dependent family is thought to be a function of the chronicity of dependency and the chaos which arises from it.

THE COPING ROLES

Wegscheider describes four basic roles played out by offspring in virtually every alcohol dependent family. She has labelled these the hero, the scapegoat, the lost child, and the mascot.

Scapegoat - The function of the scapegoat is to protect the system from further disintegration by becoming the family's "problem" and displacing its focus onto him or herself. The scapegoat accomplishes this through self-destructive behaviour, which results in negative attention both within and outside the family system. The scapegoat runs a high risk of becoming another alcohol dependant, rejecting the family system by running away, rebelling and acting-out.

Lost child - The function of the lost child is to provide relief by not being a burden to the family. This child spends much time alone, demanding little attention from the family. The lost child has learned that involvement in the family brings only pain and therefore withdraws, consequently experiencing the pain of loneliness. The lost child becomes self-reliant, quietly and unobtrusively withdrawing from the family system. Wegscheider suggests that those who adopt this role are the most likely to experience difficulties in establishing intimate relationships with others.

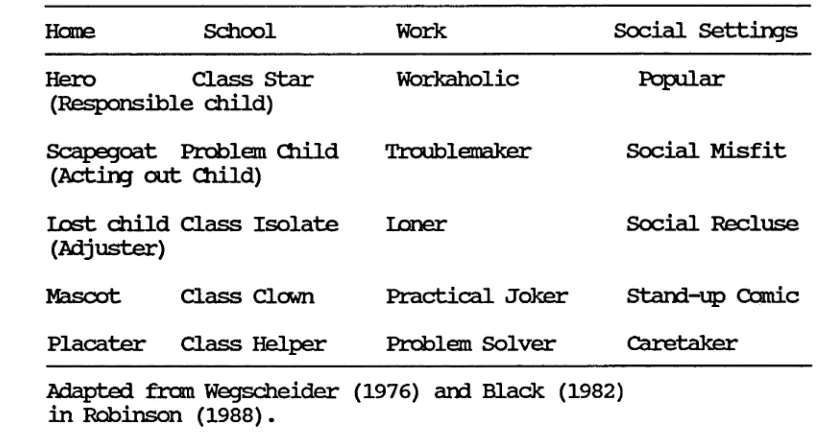

Black (1982) has described four role patterns which resemble those of Wegscheider. She has labelled these the responsible child, the adjuster, the placater and the acting-out child - a single unitary role which occurs in isolation. The main difference between the two typologies is the existence of a mascot role within Wegscheider*s clinical descriptions, and a placater role in Black's. The placater is the family comforter who is compelled to smooth over family conflicts. According to Black those individuals who take on the placater role are often very sociable and strive to help others adjust and feel comfortable. Placaters are also preoccupied with the emotions of others to the detriment of their own, taking responsibility for the family's emotional well-being. The role is often adopted to alleviate a sense of guilt over the drinking behaviour of a parent (See Table 1).

f o r each person, but th e r o le s t h a t an in d iv id u a l assumes

may s h i f t , depending on th e fa m ily 's needs.

Table 1: S u rv iv al r o le s o f COAs and a s s o c ia te d s o c ia l

s e t t i n g s

Horae School Work Social Settings

Hero Class Star

(Responsible child)

Workaholic Popular

Scapegoat Problem Child (Acting out Child)

Troublemaker Social Misfit

lo st child Class Isolate (Adjuster)

loner Social Recluse

Mascot Class Clown Practical Joker Stand-up Comic

Placater Class Helper Problem Solver Caretaker

Adapted from Wegscheider (1976) and Black (1982) in Robinson (1988).

Wegscheider su ggests t h a t th e r o le s occur in a l l tro u b le d

f a m ilie s and o c c a s io n a lly in h ealth y fa m ilie s in tim es of

s t r e s s . She a s s e r t s , however, t h a t in alcohol dependent

fa m ilie s th e s e r o le s are more r i g i d l y fix ed and a re played

w ith g r e a t e r i n t e n s i t y , compulsion, and d e lu sio n .

O ccasio n ally , when circum stances change or one r o le becomes

to o uncom fortable, a person may t r y another r o l e . In an

alco h o l dependent fam ily, however, sw itching r o le s f o r any

reason i s b eliev ed to be uncommon, sin ce th e in d iv id u a l

becomes trapped in to one r o le . Personal p o t e n t i a l s are

g ra d u a lly deformed to f i t i t s demands as he or she slowly

[image:29.558.89.503.191.413.2]Presumably, such rigidity in behaviour among the offspring of alcohol dependents is a function of the chronic nature of parental drinking and an attempt by them to impose structure and stability within their chaotic lives. This is especially important for COAs because of the unpredictability of parental behaviour and possible family disorganization.

A major assumption of the role acquisition theory proposed by both Black and Wegscheider, is that while the coping roles adopted by COAs are functional in the alcohol dependent family, they become increasingly dysfunctional as each child matures and leaves home (Black, 1981). The roles do not necessarily change on leaving the home environment, instead, becoming patterns carried into adulthood. Thus, while adaptive within the alcohol dependent home, these roles ultimately become maladaptive since the individual is thought to make personal sacrifices of autonomy and affective expression in childhood and adolescence that result in serious outcomes for adult functioning.

exposure to parental alcohol abuse, suggesting that the dynamics which occur within an alcohol dependent family are in some way different from those in families experiencing other forms of disruption. Also, little consideration is given to the variability in functioning among alcohol dependent families.

RESILIENCE AND MODERATING VARIABLES

A major criticism of Wegscheider and Black's conceptions of the COAs experience is that they are at odds with other empirical findings and with developments in the vast stress literature. Research which conflicts with the propositions put forward by these clinicians falls into two major

categories:

research which has reported COAs as well adjusted; and

stress research which suggests that individuals differ in the extent to which they perceive chronic stressors such as parental alcohol abuse as a threat, loss or challenge.

Positive Adjustments Among COAs

ignoring the possible existence of resilient children. Some even argue that children growing up in an alcohol dependent family experience some positive outcomes (Heller, et al., 1982; Russell et al., 1985). Nardi (1981) suggests that some roles may lead to important skills useful in later work or personal situations. Few have considered the potential strengths resulting from major task and role rearrangements during socialization in an alcohol dependent family.

within normal limits. In Werner's (1986) study of COAs, 59% were found to be coping well at 18 years of age.

In support of her theory that adult COAs experience a greater level of psychological distress than non COAs, Black and her associates surveyed 409 self-reported COAs and 179 non COAs. They concluded that COAs were more likely to report psychological problems than controls, though the latter did experience similar primary problem areas to the COAs. Burk and Sher (1988) have criticised the study on the grounds of a non-representative sample (subjects were enlisted through two drug and alcohol journals) with a likely heightened interest in alcohol dependency issues, and a significant number of nonCOAs endorsing the same problems as COAs. This, they argue, provides evidence contrary to the notion that COAs experience a uniquely negative outcome from living in a stressful family environment. Furthermore, a significant proportion of COAs were found to be relatively symptom free, indicating that some escape the adverse effects of parental drinking behaviour. The data support the view that parental drinking need not be harmful and that mediating factors may be operating which buffer the effects of parental alcohol dependency.

these families have been found to be similar to controls, whereas families of relapsed alcohol dependants were found to be less cohesive, less expressive, more reclusive and also more likely to experience mental health problems (Moos & Billings, 1982; Callan & Jackson, 1986). Such evidence of resiliency and recovery among COAs contradicts Wegscheider and Black's assumptions that all COAs are adversely affected and continue to exhibit dysfunctional behaviour into adulthood.

EXPLANATIONS OF ADJUSTMENT

Stress and Coping Models

alcohol abuse. Stress research suggests that those working with COAs need to more fully recognize the importance of the context of stress and the impact of situational (eg. social support) and psychological factors (eg. coping strategies) in mediating and/or moderating an individual's reaction to stressors.

The relevance of the stress paradigm for the COA experience is further supported by the growing recognition that there are multiple independent variables to be considered in the alcohol dependent family. The need to address the issues of variability in functioning among families, and those factors which act as moderators for the effects of parental alcohol abuse has arisen from contemporary studies of COAs. The literature pertinent to these issues will now be reviewed.

Variability in Family Functioning

Recently, research has focused on the identification of family environmental factors, other than parental alcohol dependency, that significantly increase or decrease the risks to offspring in the development of psychopathology. Reports in the literature of greater family disruption within the home environments of alcohol dependents are common. A number of studies describe the high frequency of marital discord and breakdown (Chafetz et al., 1971; McLachlan et al., 1973; El Quebaly & Offord, 1977; Wilson & Orford, 1978; Moos & Billings, 1982; Schulzinger et al.,

involved, and over offspring taking on care for a parent or parental responsibilities. A lack of secure family cohesiveness was also shown by McLachlan et al (1973) to differentiate families of alcohol dependants from controls.

A preliminary analysis of the home environments of COAs compared with nonCOAs by Reich et al (1988) found homes of COAs to function significantly more poorly in a number of areas, suggesting that parental alcohol dependency causes 'a global diminished functioning' of the family. Other studies of the home environments of alcohol dependents have shown them to be characterised by unemployment, tumult and chaos

(Nylander, 1960; Fine et al., 1976; Wilson & Orford, 1980).

Moderating Variables

Recognition of the variation in adjustment of COAs has lead to attempts to delineate factors which moderate the effects of parental alcohol dependency. West and Prinz (1987) focused on family relations, identifying three specific risk factors as disrupted family routine, inadequate parental guidance and nurturance, and modelling of maladaptive coping styles. According to Holden et al (1988) adolescents with alcohol dependent parents were less likely to identify their parents as a source of support and thus had fewer numbers of supports than those from non-dependent families. Two studies that explored the impact of other risk factors (Moos & Billings, 1982; Schuckit & Chiles, 1978) found that children's emotional functioning was further adversely affected by divorce, avoidance coping, anxiety, affective disorder in either parent, and undesirable changes in the family environment and life situation.

Studies of family processes (Wolin et al., 1979; Bennett et al., 1988; Reich et al., 1988) indicate that children from dependent families are less likely to become alcohol dependent themselves if family members are able to maintain family rituals such as Christmas, or regular mealtimes, and to keep these times relatively stress-free. The ability of the family to remain cohesive and to maintain family rituals relatively undisturbed by the alcohol dependant's drinking has been found to be protective (Moos et al., 1979; Moos & Billings, 1982; Wolin et al., 1979). The former showed a better treatment outcome for the alcohol dependant in cohesive families who maintained an active recreational orientation and social participation (Adler & Raphael, 1983) .

from alcohol dependent families with high levels of deliberateness are less likely to develop drinking problems than children from dependent families characterized by low

'levels of deliberateness' (Reich et al., 1988).

Other studies have highlighted the personal characteristics of COAs that may help them avoid the damaging effects of parental alcohol dependency. Werner's (1986) study of COAs revealed several differences between those who where coping well at 18 years of age and those not functioning satisfactorily. Those coping well had been affectionate children, at least of average intelligence with good expressive skills, they had an internal locus of control, high self-esteem, a desire for achievement and were responsible and empathetic.

Coping Strategies

children of heavy drinkers used fewer different methods of coping with anxiety or depression than children of abstainers. There was, however, no attempt to detail the types of coping used or to examine the relationship between coping and adjustment. A study of young adult COAs by Clair and Genest (1987) revealed that they tended to use more emotion-focused than problem-focused coping in response to environmental stress than a comparison group. They also tended to use more wishful thinking and avoidant strategies than nonCOAs.

environment of COAs with nonCOAs, Reich et al (1988) reported no difference in respect to coping skills between the two groups, and no evidence, therefore, of an adaptive pattern corresponding to that of the hero.

THE PRESENT STUDY

This work raises the question of whether the typologies outlined by Wegscheider and Black represent strategies which if used by COAs, will protect them from psychopathology. As yet empirical data have not resolved this issue. More fundamentally, data which support the validity of the typology is sparse. In an attempt to directly assess the validity of the four roles described by Black amongst COAs, Rhodes and Blackham (1987) developed scales with reasonable

Before proliferating typologies, or abandoning the work of Wegscheider and Black, there is merit in testing the roles in a different context, with different measuring instruments, and with a methodology which enables us to control for the confounding risk factor of family disorganization identified by Rhodes and Blackham.

The research strategy used to achieve this goal was to define the roles as clearly as possible using the work of both Wegscheider (1976,1981) and Black (1979,1981) to write items corresponding to the constructs they were describing. In so doing, distinctions were not drawn between the responsible child (Black) and the hero (Wegscheider), the adjuster (Black) and the lost child (Wegscheider), and the acting-out child (Black) and the scapegoat (Wegscheider). The fourth role in Black's typology, the placater, was differentiated from its counterpart in Wegscheider's model, the family mascot.

The research goal was to assess the detrimental effects on psychological well-being of parental drinking behaviour and family disorganization net of each other, and the role of family disorganization in exacerbating the effects of parental alcohol dependency. Conversely, it was expected that a high level of family organization (cohesive, deliberate and supportive) would buffer COAs.

The research design selected for this study was one which sampled children on a random volunteer basis from the adolescent population. This approach addressed a number of problems inherent within the literature on COAs. First, failure in the past to utilize non-alcohol dependent or non-problem families has resulted in an inability to assess the degree to which the problems of offspring are due to parental alcohol dependency per se or to growing up in a troubled family (Carter et al., 1990). A sample which is not truncated on either research variable allows the question of the confounding of these two variable to be addressed statistically through the use of regression models.

seek treatment or who come to the attention of the health and legal professions (El Guebaly & Offord, 1977).

COAs have been identified through treatment facilities of parents (eg. Cork). Others have been identified through advertising or based on the judgements of educators who interact with the child (eg. Jacob & Leonard, 1986; Rolf et al., 1988). Many studies have sampled adolescents who already come to be defined as "in trouble" because of delinquency, drug abuse or emotional problems and then used institution records or interviews to determine whether they came form alcohol dependent homes (eg. Ablon, 1976).

children's lives, that behaviour is characterized as 'alcoholic'.

RESEARCH GOALS

Using adolescents from the general population, the purpose of this study is therefore threefold:

1. to determine whether empirical support can be found for the survival roles outlined by Wegscheider and Black.

2. to develop a profile of the users of these roles within the general adolescent population.

CHAPTER TWO: METHOD

RESPONDENTS

MEASURES: PARENTAL ALCOHOL DEPENDENCY

Parental drinking behaviour was assessed using the Children of Alcoholics Screening Test (CAST), the Children from Alcoholic Family (CAF) instrument, and a single item (BEST) which questioned the frequency of parental drinking. In this section the psychometric properties of each of these measures will be examined.

Children of Alcoholics Screening Test (CAST)

Respondents were asked to complete the CAST (Jones, 1981). The CAST score was used as the primary measure of parental drinking for each respondent. Following Rhodes and Blackman (19 87) , this instrument was used to define homes in which parental drinking was a problem. The 30 item test assesses offspring perceptions of how they have been affected by and respond to a parent's drinking. Items which form the scale measure:

a) emotional distress associated with a parent's alcohol use/misuse (eg. Q2 Have you ever lost sleep because of a parent's drinking ?)

c) Attempts to control a parent's drinking (eg. Q3 Did you ever encourage one of your parents to quit drinking ?) d) Efforts to escape from parental drinking (eg. Q28 Did you

ever stay away from home to avoid the drinking parent or your other parent's reaction to the drinking ?)

e) Exposure to drinking related family violence (eg. Q7 Has a parent ever yelled at or hit you or other family

members when drinking ?)

f) Tendencies to perceive their parents as alcohol

dependants (’eg. Q22 Did you ever think your father was an alcoholic ?)

g) Desire for help (eg. Q26 Did you ever wish that you could talk to someone who could understand and help the

alcohol-related problems in your family ? (Jones,1982b)).

A reliability analysis of the scale revealed an alpha reliability coefficient of .97. This compared favourably with previous reliability estimates of .98 found by Jones (1981 a & b) , and Dinning and Berk (1989) which were in the mid .90s. With a possible range of scores from 0 - 3 0 , the mean for the scale was 5.81 (SD=8.30). According to Jones'

(1983) criterion, 67 respondents (61.%) were identified as children of non-alcohol dependents (CAST score 0 - 1), 10 (9.2%) were identified as children of problem drinkers/possible dependants (score 2 - 5 ) , and 32 (29.3%) were identified as children of alcohol dependants (score >

6) . A 3 category system was used for subsequent analyses, in which 1 indicated nonCOAs, 2 children of problem drinkers/possible dependants, and 3 COAs. As expected, the recoded CAST (NEWCAST) was highly correlated with the original CAST measure (r = .86, p<.001).

Children of Alcoholic Families instrument (CAF)

both of your parents would drink less ?". The item relies on children's reactions to parental drinking, rather than a detailed characterization of that drinking. Respondents were provided with response categories rarely, sometimes or often. The range of scores on this 3 point rating scale was from 1 - 3 , and the mean of was 1.48 (SD=.72). The numbers responding to each of the response categories are presented

[image:53.558.62.507.71.508.2]in Table 2.

Table 2: Frequencies of response to CAF item categories.

Answer Frequency Percentage

1 Rarely 73 65.2

2 Sometimes 24 21.4

3 Often 15 13.4

N = 112

As shown, over 30 percent of respondents indicated having wished at least sometimes that a parent would drink less.

Frequency of parental drinking (BEST item)

s i t u a t i o n ?", and p r o v i d e d w i t h four r e s p o n s e categories; p a r e n t s d o n ' t dri n k at all, p a r ents dri n k rarely, parents d r i n k s o m e t i m e s or parents d r i n k often. W i t h a poss i b l e range of s cores from 1 - 4 , the m e a n of the scale w a s 2.81 (SD = .90). F r e q uencies of response to each c a t e g o r y are p r o v i d e d in T a b l e 3. As shown, a p p r o x i m a t e l y 50 p e r c e n t of the sam p l e in d i c a t e d that parents d r ank alcohol sometimes, and a p p r o x i m a t e l y 20 p e r cent d e s c r i b e d f r equent alcohol consumption. Th i r t y p e r c e n t of r e s p ondents r e p o r t e d that alcohol c o n s u m p t i o n b y their pare n t s was e i t h e r rare or n o n - e x i s t e n t .

T a b l e 3: F r e q u e n c i e s of resp o n s e to the B EST i tem c a t e g o r i e s .

Response category Frequency Percentage

1 Parents do not drink 12 10.7

2 Parents drink rarely 21 18.7

3 Parents drink sometimes 55 49.2

4 Parents drink often 24 21.4

N = 112

MEASURES: FAMILY D I S O R G A N I Z A T I O N

[image:54.558.71.517.82.409.2]Family Deliberateness

Four questions were included about getting together as a family for special occasions, eating meals together, following through on family plans, and enjoying family occasions. These items, forming the Deliberateness Scale, were included in order to gauge the extent to which a respondent's family planned and carried out family rituals and celebrations. This measure was included in view of the importance placed on the establishment and maintenance of rituals within families as buffers for COAs. The alpha reliability coefficient for this scale was .76. With response categories for each of the four questions; rarely, sometimes and often, the possible range of scores was 4 -12. The mean for the scale was 9.07 (SD=2.35). High scores indicated greater levels of deliberateness within the respondent's family.

Emotional Support

were made on a three point rating scale identical to that used for the Deliberateness Scale. The possible range of scores was 2 to 6. The mean for the scale was 4.04 (SD=1.41). High scores indicated greater emotional support from parents.

Family Cohesiveness

Family cohesiveness was measured using the method outlined by Cooper et al (1983) . Respondents were presented with pictorial representations of families. Family members were depicted as small circles within the larger family circle, with mother and/or father defined. The spacing of the smaller circles reflected the distance or closeness of family members to each other. Respondents were required to choose a diagram which best represented their family situation and identify themselves within that family structure. A cohesive family was defined as one in which the participant was close to others who, in turn, were close to each other. Uncohesive families were those in which respondents felt isolated from other family members; respondents, together with their siblings felt distanced from their parents; and parents were divided and respondents were not close to both parents. .

59 (55%) adolescents within the uncohesive group, 29 indicated that they felt isolated from the family, 6 indicated that together with their siblings, they were distanced from parents, and 24 were from a divided family, where parents were not close to each other and offspring were not close to both parents. A total of 48 adolescents

(45%) indicated that their families were cohesive.

MEASURES: COPING ROLE INSTRUMENT

This measure comprised the thoughts, feelings, attitudes and behaviours characteristic of the five roles described by Wegscheider and Black. These included the roles of hero,

MEASURES: WELL-BEING

A measure of adjustment, or satisfaction with self and the surrounding world, was included in order to explore the extent to which coping role behaviour could be linked with maladjustment. Two scales, the shortened version of the General Health Questionnaire (Goldberg, 1972) and a single item measuring life satisfaction (Andrews & Withey, 1976) were administered. According to Scott (in Heaven & Callan

(Eds), 1990) the prominent foci of adjustment for most Australian adolescents are self, family, friends, school possessions, and recreation. The "self" as a focus of adjustment is represented in measures which tap self-esteem and neurotic symptoms (such as the GHQ). The other foci are reflected in expressions of satisfaction. Inclusion of both the GHQ and the life satisfaction measure thus tapped into both foci of adjustment, the self and expressions of satisfaction with life in general.

General Health Questionnaire 12 (GHQ-12)

scores indicated greater levels of psychopathology. The possible range of scores for this scale was 0 to 36. The mean for the sample was 13.59 (SD=7.78).

Life Satisfaction Scale

Perceived life satisfaction was measured through inclusion of a Life Satisfaction Scale developed by Andrews and Withey (1976) . Respondents were asked "How do you feel about your life as a whole ?", and answered on a seven point scale ranging from Delighted to Terrible. As recommended by the author the item was repeated at the end of the questionnaire, the mean of the two life satisfaction items providing the Life Satisfaction Scale. The correlation between the first and second administration of the item was .92. With a possible range of scores from 2 to 14, the mean for the sample averaged over the two occasions was 8.88 (SD = 3.26). High scores on this scale indicated high levels of life satisfaction.

PROCEDURE

Respondents obtained through self-help groups, youth centres and youth refuges were approached individually and asked whether they would like to participate in a study on adolescents, stress and parental drinking. Permission to approach individuals was obtained from refuge supervisors, youth centre and self-help group co-ordinators. Individuals were told that they would be required to complete a questionnaire which asked them . about their thoughts, feelings, and behaviours associated with the possible drinking behaviour of a parent or parents, and in relation to life in general. Each respondent was also informed that completion of the questionnaire would take between 20 and 30 minutes. It was emphasised that all responses would be confidential and that involvement in the project was on a voluntary basis. Volunteers were then provided with a parental consent form which was returned prior to participation in the study. Permission for adolescents from youth refuges to participate in the study was obtained from refuge supervisors. Questionnaires were completed individually by participants in the presence of the researcher.

was then arranged for the researcher to administer questionnaire to participants as a group.

RESULTS

CHAPTER THREE

INTERRELATIONSHIPS AMONG THE INDEPENDENT VARIABLES AND MEASUREMENT OF THE COPING ROLES

INTERRELATIONSHIPS AMONG DRINKING MEASURES

The i n t e r c o r r e l a t i o n s among the three d r i n k i n g m e a s u r e s and the t r i c h o t o m i z e d CAST (NEWCAST) are p r e s e n t e d in Table 4

Table 4: Intercorrelations of the three drinking measures

Drinking Measure CAST CAF BEST NEWCAST

CAST CAF BEST NEWCAST

1.00 .71*** .40*** .86***

1.00 .38*** .63***

1.00

.40*** 1.00

M 5.18 1.48 2.81 1.68

SD 8.30 .72 .90 .90

*** p<.001

respectively. The implications of this finding are firstly, that asking respondents to describe the frequency of parental drinking behaviour may result in an underestimate of drinking behaviour. Second, the qualitative information obtained by asking adolescents about their perceptions of parental drinking is likely to be the more critical variable

in determining the effects of this behaviour on offspring.

Demographic Correlates of the Drinking Measures

Correlations of the drinking variables with age, sex and employment status are presented in Table 5.

Evidence of an effect for age was indicated by significant negative correlations between this variable and the CAST and CAF measures. The perception of problems associated with parental drinking and the wish that parents would drink less tended to be greater among younger adolescents. No significant age effect was found for responses to the BEST item. Neither sex nor employment status were related to perceptions of parental drinking behaviour.

does: parental drinking appears to pose a more serious

threat to younger adolescents.

Table 5: Correlations of the three drinking measures

wit h age, sex and employment status.

Demographic variables

Drinking measure Age Sex Emp

CAST -.24* .13 .15

CAF -.25** .17 .03

BEST -.12 .16 -.18

NEWCAST -.22* .04 .18

* p<.05 ** pc.Ol

INTERRELATIONSHIPS AMONG FAMILY DISORGANIZATION VARIABLES

As expected, the family disorganization variables were

intercorrelated (see Table 6) . Availability of emotional

support was most strongly associated with family

deliberateness and cohesiveness as a family unit. Higher

levels of emotional support were likely among cohesive

families who planned, followed through and enjoyed family

rituals. Cohesiveness as a family unit was also associated

with a tendency to plan, follow through, and enjoy family

[image:66.558.75.484.85.364.2]Table 6: Intercorrelations of family disorganization

variables.

Family variables 1 2 3

1 Emotional Support —

2 Cohesiveness .53***

-3 Deliberateness .53*** ,3 8*** —

* p<.05

** p<.01 *** pc.001

When the demographic correlates of the family

disorganization variables were examined, no significant

differences between males and females emerged, nor was there

any effect for age (see Table 7) . A significant negative

correlation between employment status and both cohesiveness

(r=-.31, p = .001) and deliberateness (r=-.40, p<.001)

suggested that respondents who were neither at school nor

working, but rather unemployed, were more likely to

experience less cohesive family relationships and lower

deliberateness within the family. A slightly weaker

negative correlation was found between employment status and

emotional support (r=-.20, p<.05). This suggested that

unemployed adolescents were also more likely to receive less

[image:67.558.78.512.134.638.2]Table 7: Correlations of the family disorganization variables with age, sex and employment status.

Age Sex Emp

Emotional Support -.00 .09 -.20*

Cohesiveness . 08 -.04 -.30**

Deliberateness .09 -.06 -.40*** * p < .05

** p<.01 *** p<.001

INTERRELATIONSHIPS AMONG DRINKING MEASURES AND FAMILY DISORGANIZATION VARIABLES

Intercorrelations of the three drinking measures with family disorganization variables are presented in Table 8. All family disorganisation measures correlated significantly with the CAST, NEWCAST and CAF instrument scores. Those adolescents who expressed concern about parental drinking were more likely to come from non-cohesive family units where family deliberateness was low. Furthermore, having an alcohol dependent parent was also associated with diminished emotional support.

emotional support seemed to be unaffected by the frequency

of parental drinking.

Table 8: Intercorrelations of the parental drinking

measures (CAST, CAF, BEST, and NEWCAST) with

family disorganization variables (emotional

support, cohesiveness and deliberateness).

Parental Drinking Measure

Family variable CAST CAF BEST NEWCAST

Emotional Support Cchesiveness Deliberateness

-.28** -.40*** -.52***

-.20* -.29** -.43***

-.13 -.35*** -.11

-.28** -.34*** -.52***

* p<.05

** p<.01 *** p<.001

In summary, these data demonstrate that adolescents who

indicate problems associated with parental drinking were

more likely to experience a family atmosphere of diminished

ritualisation and recreational orientation, family divisions

or detachment from the family unit, and to receive less

emotional support from their parents. Frequency of alcohol

use was related to family cohesiveness but not to emotional

support or deliberateness. The strong relationship with

cohesiveness suggests that the poor predictive power of the

frequency of alcohol use is not associated with poor

measurement. More likely the explanation lies in the

consequences of parental drinking. Where there are

[image:69.558.70.511.117.765.2]with family disorganization are found. Both the CAST and the CAF tap the adolescent's perceptions of threatening consequences, whereas the BEST does not.

MEASUREMENT OF THE COPING ROLES

The remainder of this chapter is devoted to the measurement of the five coping roles and an analysis of their demographic and adjustment correlates.

First of all, reliability analyses were conducted to assess the degree of coherence among items representing each of the five coping roles. It will be recalled that items were written to correspond with the role characteristics defined by Wegscheider and Black, so that it was possible to develop specific hypotheses about which items belonged to which scale. Alpha reliability coefficients for each role in the parental drinking group (CAST>2), the non-drinking group

(CAST<2), and the group as a whole, are presented in

Table 9. Means and standard deviations for each role are given, again broken down by group.