SCREENING FOR

ALCOHOL RELATED BRAIN DAMAGE

AMONG

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINALS

WITH

DRINKING PROBLEMS

Trevor J. Cocks

This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment

of the requirements for the degree of

Master of Clinical Psychology at the

Australian National University

DECLARATION

I declare that this thesis reports my original work and that no part of

it has previously been accepted or presented for the award of a degree

or diploma by any university.

To the best of my knowledge no

material previously published or written by another person is included

except where due acknowledgment is given.

Trevor J. Cocks

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I wo ul d like to express my grateful a p p re c i a ti o n to the following people and organisations for their con tri b u tio n to the preparation of this thesis:

My course supervisor, Dr Don Byrne for his patience and invaluable feedback; technical staff at the ANU Ps ych ol ogy Department for their advise on computing hardware and for building the speed test jig; the publisher, Psychological As sessmen t Resources Inc. for giving special permission to reproduce aspects of the W C ST from the Heaton manual (1981); Margaret Borger and Linda Wilson of the Alice Springs Alcohol Drug Re sou rce & Education Service and D e b b i e C or dn er for their c o n s t a n t p e r s o n a l and a d m i n i s t r a t i v e s u p p o r t ; Phil B e r ri e from MacVisions for his superb co mputer p ro g ra m m in g skill and talent for i n t e r d i s c i p l i n a r y c o op e r a t i o n ; Y v o n n e P i t t e l k o w for her statistical tuition and Michael Adena from INTST AT , for loaning the expensive s t a t i s t i c a l s o f t w a r e ; S p o n s o r s for the J o h n H a w k i n s M e m o r ia l Scholarship and the National Ca mpaign Ag ainst Drug Abuse for their generous financial support; the Aus tral ian Institute of Abori ginal & Torres Strait Islander Studies and the Alcohol & Drug Foundation of Aus tralia for their ex cellent library re s o u rc e s and helpful staff; the many staff members at Alice Springs Hospital for their considerable cooperation both during and after data collection, including Librarian Pe te r Ralph, a d m i n i st r a t o r s, m edi cal , n u r si n g an d other staff; the Institute of Abori ginal De v el op m en t for their willi ng ne ss to provide Aboriginal interpreters; Maggie Brady from the Australian Institute of Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Studies and Research Officer Dr Carol Watson from the NT Department of Health & Community Services, for their considerable en couragement and advice in the formulation of this study; Doug Walker and Billy Armstrong for their invaluable help as Aboriginal consultants on the modification of western psychological t e s t s .

Finally, I wish to thank all the patients who participated in the study, w h o s e pe rs o n a l ef f or ts have c o n t r i b u t e d to our u n d e rs t a n d i n g of A b or ig in al drin kin g p ro b lem s and h o p e fu ll y will inspire others to investigate culturally appropriate interventions for alcohol misuse.

DEDICATION

CONTENTS

DISCLAIMER

i

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ii

DEDICATION

iii

TABLES

xv

ABSTRACT

xvi

INTRODUCTION

1

Cros s - Cul t ural Cogni tive Assessment 2 Hi s t o r i c a l Per s pe c t i ve ' s

Cognitive Deficit Tradition

Pioneering Australian Studies

3

New Directions and the Difference-Deficit Controversy

4

Cont emporary Approaches

to

Aboriginal Cogni tion6

Psychic Unity of Mankind

Different Learning Styles

7

Cognitive Testing Approaches

Integrated

Approaches

8

Test i ng American Indians 9

Characteristic Performance Profile

Intra-cultural Variability

10

Test i ng Australian Abori gi nal s 1 1

Norm-referenced Tests

Culture Sensitive Approaches

Ethnographic Approach

1 2

N e u r o p s y c h o l o g i c a l - I n t e l l i g e n c e Test Di s t i n c t i o n

Neuropsychological Tests

1 3

Intelligence Tests

Combined Approach: Impairment Index

1 4

Probl em Solving

Hierarchy of Tactics

Effect of Acculturation

1 5

Modifying Test Context 16

Clarify Misunderstandings

Familiar Stimuli

Appropriate Instructions

1 7

Story Format

Trained Response

1 8

Guide-lines

for Cross-Cultural

Testing

18

Testing Aboriginals for ARBD

1 9

C u l tu r a l

Assessment

2 0

Continuum of Cultural Effects

Mythology of Culture-Fair Tests

2 1

A c c u l t u r a t i o n

23

Aboriginality

Measurement

24

Alcohol

Problem Assessment

2 5

Nature of Alcohol Problem

Drinking pattern

2 6

Dependence syndrome

Alcohol related psychosocial and biomedical problems

Alcohol Problem Screening Accuracy 27

Test Sensitivity

Test Specificity

Self Reported Drinking Pattern 2 8

Classification of Alcohol Problems 2 9

P s y c h o m e t r i c A s s e s s m e n t 30

Purpose

Alcohol Dependence Syndrome

Single Laboratory Tests 3 2

Gamma Glutamyl Transferase

Mean Corpuscular Volume

3 4

Aspartate Transferase

3 5

Alkaline Phosphatase

Neuropsychological Correlates of Laboratory Tests

Laboratory Test Limitations

3 7

C om b in ed A pp r o a c he s 3 8

Combined Laboratory Tests

Combined Assessment Methods

3 9

Culture and Alcohol Problem Assessment

Drinking Pattern Differences

Alcohol Withdrawal Across Cultures 4 0 A ss es sm en t of the Acute Withdrawal Syn dr om e 4 1 ADS Scale Applications Across Cultures 4 2 C u l tu r e - R ed u c ed Assessment of W ith dr aw al Severity

A l c o h o l R e l a t e d B r a i n D a m a g e 4 3

R e s e a r c h M e t h o d o l o g y

Alcoholic Samples

Social Drinking Samples 4 5

M e t ho d s Used

E p i d e m i o l o g y o f A R B D 4 6

C u r r e n t Lim itations

Incidence of ARBD 4 7

N e u r o p s y c h o l o g i c a l I m p a i r m e n t 4 8

Reasoning Skills

C om ple x Perceptual Motor Skills 4 9

New Learning Ability

Tem po ral Gradient of Memory Deficit 5 0

C o r r e l a t e s o f I m p a i r m e n t 5 1

An im al Models H u m a n Studies

R e c o v e r y f r o m A R B D 5 2

Short Term Recovery

Long Term Recovery 5 3

Correlates of Recovery 5 4

Process o f ARBD

T em p or ar y Organic Mental Disorder 5 5 L o c a l i s e d I m p a i r m e n t

C o n t in u u m of Im pairment

F a c t o r s E f f e c t i n g NP P e r f o r m a n c e 5 6

Family History of Alcoholism

N e u r o m e d i c a l Risk 5 7

A g e 5 9

E d u c a t i o n 6 0

A ff e ct iv e States 6 3

Drin ki ng History 6 4

Th e P r e s e n t S t u d y

C r o s s - C u l t u r a l C o g n i t i v e A s s e s s m e n t

Cul t ural As s e s s me nt 65

Alcohol Problem Assessment 6 6

Drinking Pattern

Laboratory Tests

SADD Scale

6 7

Composite Measure of Excessive Drinking Risk

Aim

of the

Study6 8

Cross-Cultural Efficacy of NP Tests

Differential Diagnosis for ARBD

Research Design

Criterion Measures

Control Group

6 9

Multiple Regression Analyses

I n d e p e n d e n t V a r i a b l e s

Acculturation

Neuromedical Risk

Excessive Drinking Risk

De p e n d e n t Var i ab l e s

NP Test Scores

Weighted Impairment Index

Research Quest i ons

Nature and Extent of Relationship

Screening for ARBD

7 2

H y p o t h e s e s

Ho

Hi

Predicting NP Test Efficacy

Sensitive to Western Contact

Sensitive to Brain Damage

7 3

Sensitive and Specific to ARBD

METHOD

7 0

7 1

No n - Ra n d o m Sampl i ng

Selection Criteria 7 4

Exclusions

Inclusions

S ubj e c t s

Age and Gender

A b o r i g i n a l i t y

Territorial Affiliation

7 5

D a t a L i m i t a t i o n s

P r o c e d u r e 7 6

I n t e r p r e t e r s

Patient Consent 7 7

I n t e r v i e w Sch edu le

L ab o r a to r y Tests 7 8

S t a t i s t i c a l A n a l y s i s 7 9

Graphical Analysis

Composite Scale De velopment

M u lt iv a r ia te Analysis 8 1

N e u r o p s y c h o l o g i c a l T e s t i n g Cultural Modifications

Fam iliarisatio n Task 8 2

Aboriginal Maze Test 8 3

Card Match Test 8 5

Speed Test 8 7

M em or y Screening Test 8 9

A c c u l t u r a t i o n S c a l e 9 1

U r b a n i s a t i o n L ang ua ge Use

W e s t e r n Ways 9 2

Reading Skills 9 4

Verbal Skills 9 5

N e u r o m e d i c a l R i s k S c a l e 9 6

Medical Risk

L iver Function 9 8

A g e

E x c e s s i v e D r i n k i n g R i s k S c a l e 9 9 Exce ssive Cons um ptio n

First Drink 1 0 3

Last Drink

I n t o x i c a t i o n 1 0 4

Alco ho l Problems 1 0 5

SADD Scale

L a b o r a to r y Tests 1 0 6

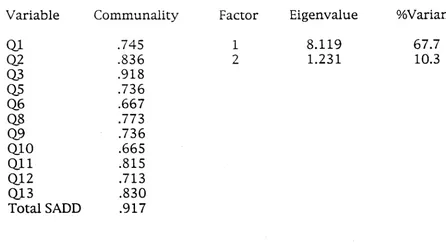

R E S U L T S 107 S ADD Scale Factor Validity

Factor Analysis

Model Diagnostics 108

Factor Statistics

Factor Interpretation 1 1 0

C o m p o s i t e I n d e p e n d e n t V a r i a b l e s

Ac c ul t u r at i on Scale Factor Analysis

Model Diagnostics 111

Factor Statistics

Factor Interpretation 1 1 3

Neuromedical Risk Scale 114

Factor Analysis Model Diagnostics

Factor Statistics 1 1 5

Factor Interpretation

Excessive Drinking Risk Scale 117

Factor Analysis Model Diagnostics

Factor Statistics 118

Factor Interpretation 120

C o m p o s i t e D e p e n d e n t V a r i a b l e s 121

S t a n d a r d i s e d I mp a i r me n t Index Ordinal Transformation

Constituent Measures

Factor Model Impai rment Index Factor Analysis

Model Diagnostics 122

Factor Statistics 123

Factor Interpretation

M u l t i p l e R e g re ssio n A nalysis 125

Eval uation of Model Assumptions

General Findings 126

1 2 6 Maze Test

Non-significant Results

Total Maze Error

127

Total Maze Speed

Maze Position Error

Card Match Test 131

Speed Test

Memory Screening Test 133

Non-significant Results

Total Memory Screening Error

NP I mpai rment Index

Gr a ph i c a l Anal ysis 135

Laboratory Test Comparisons

History of Unconsciousness

136

Acculturation

Age

137

Age and Acculturation

Age and Laboratory Measures

D I S C U S S I O N

138

Modified SADD Scale

Relevance of Composite Scales 140

Acculturation

Neuromedical Risk

141

Excessive Drinking Risk

142

Mu l t i v a r i a t e Regressi on Anal ysi s 144

General Findings

Maze Test

145

Card Match

14 8

Speed Test

151

Memory Screening Test

153

Screening for ARBD 155

M e t h o d o l o g i c a l Probl ems 158

C o n c l u s i o n 160

A P P E N D I C E S

1631. The m odified SADD Scale

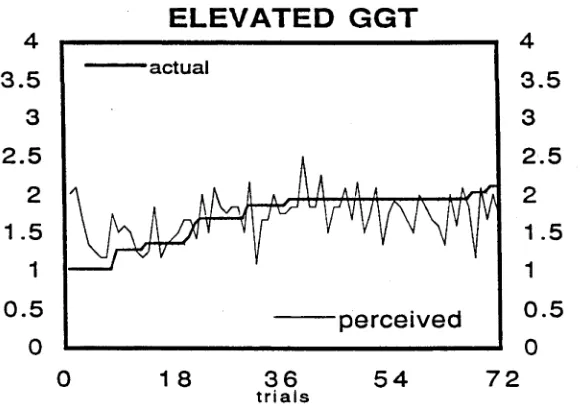

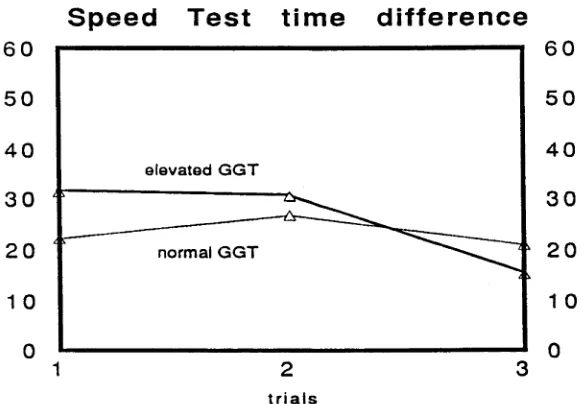

2. NP p e rfo rm a n c e co m p ariso n s fo r n o rm a l and 164 e le v a te d L a b o r a to r y T e sts:

Figure 1 Mean Maze Error per trial for patient groups with normal (n=3) and elevated (n=12) median GGT

Figure 2 Mean Maze Error per trial for patient groups with normal (n=3) and elevated (n=12) median GGT

Figure 3 Mean Maze Error per trial for patient groups with high (>85, n=10) and low (<=85, n=6) MCV

165

Figure 4 Mean Maze Speed per trial for patient groups with high (>85, n=10) and low (<=85, n=6) MCV

Figure 5 Mean Maze Error per trial for patient groups with normal and elevated AP (nearest lab test)

166

Figure 6 Mean Maze Speed per trial for patient groups with normal and elevated AP (nearest lab test)

Figure 7 Card Match Perseverative Error Index for

patients with a history of elevated and normal GGT

167

Figure 8 Card Match category shift per trial for patients groups with normal and elevated median GGT

Figure 9 Card Match cumulative error for patient groups with normal and elevated median GGT

168

Figure 10 Card Match cumulative error divided by actual shift per trial for patients groups with normal and elevated median GGT

Figure 11 Card Match cumulative perseverative error for patient groups with normal and elevated median GGT

169

Figure 12 Card Match cumulative perseverative performance ie. (cum. persev. error/category attained) per trial for patient groups with normal (n=4) and elevated (n=12) GGT

170

F i g u r e 13 C a r d M a t c h c u m u l a t i v e p e r s e v e r a t i v e p e r f o r m a n c e 170 i e . c u m . p e r s e v . e r r o r / ( t o t a i c a t e g o r y s h i f t + 1 ) p e r

t r i a l f o r p a t i e n t g r o u p s w i t h n o r m a l ( n = 4 ) a n d e l e v a t e d ( n = 1 2 ) G G T

F i g u r e 14 A c t u a l a n d p e r c e i v e d C a r d M a t c h c a t e g o r i e s f o r p a t i e n t s w i t h e l e v a t e d m e d i a n G G T

F i g u r e 15 A c t u a l a n d p e r c e i v e d C a r d M a t c h c a t e g o r i e s f o r 171 p a t i e n t s w i t h n o r m a l m e d i a n G G T

F i g u r e 16 C a r d M a t c h t i m e t a k e n t o r e s p o n d b y p a t i e n t s w i t h e l e v a t e d m e d i a n G G T a n d n o r m a l G G T

F i g u r e 17 M e a n S p e e d T e s t m o v e m e n t t i m e f o r p a t i e n t g r o u p 1 7 2 w i t h n o r m a l ( n = 6 ) a n d e l e v a t e d ( n = 1 1 ) m e d i a n G G T

F i g u r e 18 M e a n S p e e d T e s t s t o p p e d t i m e f o r p a t i e n t g r o u p s w i t h n o r m a l a n d e l e v a t e d m e d i a n G G T

F i g u r e 19 M e a n S p e e d T e s t d i f f e r e n c e b e t w e e n m o v e m e n t 173 a n d s t o p p e d t i m e f o r p a t i e n t g r o u p s w i t h n o r m a l

a n d e l e v a t e d m e d i a n G G T

F i g u r e 2 0 M e m o r y S c r e e n i n g W o r d E r r o r p r o f i l e 1 7 4

F i g u r e 21 M e m o r y S c r e e n i n g S e n t e n c e E r r o r p r o f i l e

F i g u r e 2 2 M e m o r y S c r e e n i n g F i g u r e E r r o r p r o f i l e 175

3. C o m p a r i s o n o f NP test p e r f o r m a n c e for p a t i e n t s 176 with and w i t h o u t a h i s to r y of u n c o n s c i o u s n e s s :

F i g u r e 2 3 M e a n M a z e E r r o r p e r t r i a l f o r p a t i e n t g r o u p s w i t h ( n = 9 ) a n d w i t h o u t ( n = 8) a h i s t o r y o f u n c o n s c i o u s n e s s

F i g u r e 2 4 M e a n M a z e S p e e d ( s e c o n d s ) p e r t r i a l f o r p a t i e n t g r o u p s w i t h ( n = 9 ) a n d w i t h o u t ( n = 8 ) a h i s t o r y o f u n c o n s c i o u s n e s s

F i g u r e 2 5 T o t a l C a r d M a t c h E r r o r f o r p a t i e n t s w i t h a n d 177 w i t h o u t a h i s t o r y o f u n c o n s c i o u s n e s s

F i g u r e 2 6 T o t a l P e r s e v e r a t i v e E r r o r f o r p a t i e n t s w i t h a n d w i t h o u t a h i s t o r y o f u n c o n s c i o u s n e s s

F i g u r e 2 7 C a r d M a t c h t i m e t a k e n t o r e s p o n d b y p a t i e n t s 178 w i t h a n d w i t h o u t a h i s t o r y o f u n c o n s c i o u s n e s s

4. Effect of acculturation on NP test performance: 179 Figure 28 Mean Maze Position Error against WAIS-R vocabulary

scaled scores (adjusted for age using manual norms)

Figure 29 Mean Maze Errors for total and first trial against WAIS-R vocabulary scaled scores (adjusted for age using manual norms)

Figure 30 Mean Maze Time for total and first trial against 180 WAIS-R vocabulary scaled scores (adjusted for

age using manual norms)

Figure 31 Card Match error performance (ie. total and

perseverative) after adjustm ent for total number of category shifts, against WAIS-R vocabulary scaled scores (adjusted for age using manual norms)

Figure 32 Mean Card Match category shift against WAIS-R 181 vocabulary scaled scores (age adjusted using

manual norms)

Figure 33 Mean Speed Test Difference against WAIS-R vocabulary scaled scores (age adjusted)

Figure 34 Mean Speed Test movement and stopped time 182 against WAIS-R vocabulary scaled scores

(age adjusted)

Figure 35 Mean Total Memory Screening Error against WAIS-R vocabulary scaled scores (age adjusted)

5 . NP test performance and the age of patients: 183 Figure 36 Mean Maze Errors per trial (total and first trial)

against Age (variable n)

Figure 37 Mean Maze Speed per trial (total and first trial) against Age (variable n)

Figure 38 Mean Maze Errors (total and position) against 184

Figure 39

Age (variable n)

Card Match mean category shift against Age cohort (variable n)

185

Figure 40 Card M atch error perform ance (ie. total and

p ersev erativ e) after a d ju stm en t for to tal num ber of category shifts m ade, against Age

Figure 41 Speed T est m ovem ent and stopped tim e difference for d ifferen t ages (variable n)

Figure 42 Speed Test m ovem ent tim e for d ifferen t ages (v ariab le n)

186

F igure 43 Speed T est stopped tim e for d ifferen t ages (v aria b le n)

F igure 44 T otal M em ory Screening E rror for d ifferen t ages (variable n)

187

6 . T h e r e l a t i o n s h i p o f A g e t o A c c u l t u r a t i o n ( r e p r e s e n t e d b y r e a d i n g t e s t p r e d i c t e d I Q a n d W A I S - R v o c a b u l a r y s c o r e s ) :

188

Figure 45 Predicted IQ from N A RT + Schoneil reading tests, ag ain st Age

Figure 46 W A IS-R vocabulary test raw scores, against Age

F igure 47 W A IS-R vocabulary scaled scores, against Age 189

Figure 48 W A IS-R vocabulary scaled scores (age adjusted) against Age

7 . T h e m o s t

r e l a t i o n s h i p o f p a t i e n t a g e c o h o r t t o t h e i r r e c e n t L a b o r a t o r y T e s t m e a s u r e s :

190

F igure 49 M ost recent % GGT m easures against Age

(expressed as a % of the upper reference range)

F ig u re 50 M ost recent MCV (fl) m easures against Age (95 fl is a typical upper reference lim it)

F ig u re 51 M ost recent % AP m easures against Age

(expressed as a % of the upper reference range)

191

REFERENCES

192T A B L E S

T a b le 1 F in a l S ta tistic s fo r F a c to r A n a ly s is o f th e S A D D Q u e s t i o n n a i r e

109

T a b le 2 R o ta te d F a c to r M a trix fo r th e S A D D Q u e s tio n n a ire

T a b le 3 F in a l S ta tis tic s fo r F a c to r A n a ly s is o f A c c u ltu r a tio n 112 T a b le 4 R o ta te d F a c to r M a trix fo r th e A c c u ltu r a tio n

C o m p o n e n t s

T a b le 5 F in a l S ta tis tic s fo r th e F a c to r A n a ly s is o f N e u r o m e d ic a l R is k

116

T a b le 6 R o ta te d F a c to r M a trix fo r N e u r o m e d ic a l R is k T a b le 7 F in a l S ta tis tic s fo r F a c to r A n a ly s is o f E x c e s s iv e

D r in k in g R is k

119

T a b le 8 R o ta te d F a c to r M a trix fo r E x c e s s iv e D rin k in g R is k

T a b le 9 F in a l S ta tis tic s fo r F a c to r A n a ly s is o f N P T e sts 124 T a b le 10 R o ta te d F a c to r M a trix fo r N P T e sts

T a b le 11 S ta n d a r d M u ltip le R e g r e s s io n o f A c c u ltu r a tio n , N e u r o m e d ic a l R isk a n d E x c e s s iv e D r in k in g R isk S c a le s on T o ta l M a z e E rro r.

128

T a b le 12. S ta n d a r d M u ltip le R e g r e s s io n o f A c c u ltu r a tio n , N e u r o m e d ic a l R isk a n d E x c e s s iv e D r in k in g R isk S c a le s on T o ta l M aze S p eed .

129

T a b le 13. S ta n d a r d M u ltip le R e g r e s s io n o f A c c u ltu r a tio n , N e u r o m e d ic a l R isk a n d E x c e s s iv e D r in k in g R is k S c a le s on M aze P o s itio n E rro r.

130

T a b le 14 S ta n d a r d M u ltip le R e g r e s s io n o f A c c u ltu r a tio n , N e u r o m e d ic a l R isk a n d E x c e s s iv e D r in k in g R is k S c a le s on T o ta l M e m o ry S c re e n in g E r r o r.

132

T a b le 15 S ta n d a r d M u ltip le R e g r e s s io n o f A c c u ltu r a tio n , N e u r o m e d ic a l R isk a n d E x c e s s iv e D rin k in g R is k S c a le s on th e N P Im p a ir m e n t In d e x .

134

A B S T R A C T

Chron ic e x ce ss i v e c o n s u m p t i o n of alc o h o l can p r o d u c e co gnitiv e impairment known as Alcohol Related Brain Damage (ARBD). Affected individuals c o m m on ly have difficulties p e rfo rm in g tasks that require considerable information processing effort. This can comp ro mis e new learn ing and habit c h a n g e r e q u i r e d for the t r e a t m e n t of alcohol problems. How ever, co gn iti ve p e rf o r m an c e can also be affected by cultural factors. This study investigated the efficacy of using culturally modified neurops ych ol ogi cal tests to detect A R B D among Aboriginal patients at Alice Springs Hospital. Exploratory factor analysis was used to develop compo sit e scales to predict co gnitiv e test pe rformance in sta ndard multiple linear r e g r e s s io n anal ysis . On ly spe ed of Maze learning could be predi cte d from excessive d r in kin g variables while most of the variance in cognitive test pe rformance was explained by degree of we stern ed u ca ti o n al e xp eri enc e. N u m e r o u s meth od ol og ica l problems could explain the lack of significant results and the need for more controlled research in this neglected area was emphasised.

INTRODUCTION

I n d i g e n o u s people in A u s tr a l ia and ot her parts of the worl d have e x p e r i e n c e d d e v a s t a t i n g e p i d e m i c s of i n f e c t i o u s d i s e a s e f o l lo w in g e u ro p e a n colonisation. Survivors and their su c ce ss iv e g e n erat io ns now face a new wave of non-infectious yet equally devastating "d iseases o f m o d e r n i s a t i o n " (Ku nitz 1990 p25). The p r e v a l e n c e of h y p e rt e ns io n , obesity, diabetes, malnutrition and alcoholism vary in all communities as a fun ction of social policy and organi sa tio n, e c o n o m ic and industrial d e v e l o p m e n t , g e ne tic p r e d i s p o s i t i o n , lo c a l c u l t u r e , a n d g e o g r a p h i c location. Enough is known about the impact of these so called 'new diseases' on Australian aboriginals to understand the urgency with which att emp ts to c o m b a t them have grown in r ece nt years, parti cula rly in relation to alcohol abuse (Jensen, Stauss & Harris 1977; Larsen 1979; Woo d 1980; Hunt 1981; Weibel 1982; Kahn 1986; Hill 1989; Hunter 1989; Brady 1990a; Raffaele 1991; Sessional Committee on use and Abuse of Alco hol by the Co m mu ni ty 1991). Alth oug h there are prop ortion ally more aboriginal abstainers from alcohol than n o n- ab o r i g i n al abstainers, m o st a bo ri gi n al s who drink g rea tly e xc e e d r e c o m m e n d e d safe limits (Hunter 1990; National Health & Medical Research Council 1991; Watson, Fl em in g, Ale xan de r 1988). The outco me has been pr o po rt io n a lly more serious health, social and economic consequences of alcohol abuse among aboriginals than in the general population (Alexander, 1990). In response to the devastating effect of alcohol abuse on indigenous populations of the world, new and sometimes novel solutions have been sought to treat or p r e v e n t such m a n - m a d e c aus es of d is a b ili ty and d eat h (May 1986; C a et an o 1989; Miller 1990; P a r k e r 1990). H o w ev e r , p r ev e n tio n and t rea tm en t of alcohol pr oblems within the broad er eu rop ean comm un ity have r em ain ed elusive and often short-term. Our flagging success rate may be due in part to the di mi ni sh e d ability of some individ ua ls to ben efi t f r o m the cognitive and educa tio nal c o m p o n e n ts of mainstream a l c o h o l r e h a b i l i t a t i o n p r o g r a m m e s , d u e to a l c o h o l r e l a t e d br ain

i m p a i r m e n t or d a m a g e ( A R B D ) . P o o r c o g n i t i v e p e r f o r m a n c e on ne uropsychological tests (NP tests) can be the first medical sequelae to appear with chronic drinking. The role of NP tests in early detection, rehabilitation and prevention of alcohol problems is growing in treatment c e n t r e s a ro u n d the world. H o w e v e r , there is i n s u f f i c i e n t p u b lis he d research on the use of NP tests with aboriginal people and no information at all on their use with aboriginal problem drinkers. In response, the aim of the present study was to e xpl or e the e ffi cac y of using modified western neuropsychological tests to assess ARBD.

In or der to provide an ap prop riate c o n te x t for the neurops ych ol og ica l theme of this thesis, the following c hap ter s outline both its historical r e l a t i o n s h i p to c ro s s- c u lt u r al studi es of c o g n i t i o n and the prob lem s a s s o c i a t e d w i t h t h e a s s e s s m e n t o f f a c t o r s t h a t i n f l u e n c e neuropsychological performance (ie. culture, alcohol problems and ARBD).

C r o s s - C u l t u r a l C o g n i t i v e A s s e s s m e n t

H i s t o r i c a l P e r s p e c t i v e ' s

Cognitive Deficit Tradition

E a r l y c r o s s - c u l t u r a l c o m p a r a t i v e r e s e a r c h g e n e r a l l y c o n c l u d e d that indigenous people were deficient in cognitive abilities compared to those of european descent. These conclusions were based on the overall poor performance by indigenous subjects on Weste rn tests of cognitive ability and the difficulties they had with the e uro pe an education system. Large scale testing of adult illiterates in Af ri ca and the Pacific Islands by p i on ee r in g r es ear ch er s like M a c d o n a l d , Ord and B i es h eu ve l p ro duc ed p s y c h o m e t r i c m e a su r e s of g e n e r a l c o g n i t i v e a bi li ty that had good

criterion and predictive validity. How eve r, their tests were intended for the selection of military and factory pers on nel in de veloping countries and the de bate over the m ean ing of their test scores and the factors

influencing them became a focus for later m ultivariate research (Irvine & C arroll 1980 citing Grant 1969, Irvine 1969, Scribner 1974, St Georges 1974, P o o rtin g a 1971, Price-W illiam s 1962, K ellaghen 1968, M cLaughlin 1970, Okonji 1971, Cole & Gay 1972; Klich & Davidson 1984 citing similar r e f e r e n c e s ) .

In an h i s t o r ic a l o v e rv ie w of c o g n itiv e r e s e a r c h w ith A u s tra lia n A b originals, T urtle (1991) discussed the p ro m in en t research investigators since w hite settlem ent and the political and scientific influence that led them to p u rsu e the myth of cu ltu re-free ability testing. Many of the early p io n e e rs of cro ss-c u ltu ral research had id e n tifie d the difficulties p o se d by p s y c h o lo g ic a l testin g in test alien c u ltu re s but few had questioned their m ethods or purpose. The prom inence of Charles Darwin's e v o lu t i o n a r y th e o ry and the im a g e o f a b o r i g i n a l s as the d ire c t d e sce n d an ts o f "H om o fossilis" in flu en ced early resea rch e rs to believe they were studying a prim itive mental culture (T urtle 1991, reporting on the w o rk o f Fry 1930, Porteus 1931-33, P id d in g to n 1931). From this im plicit m eth o d o lo g ical bias, observing deficits in aboriginal perform ance became a self fulfilling prophesy (Irvine & Carroll 1980).

Pioneering Australian Studies

A n u m b e r of early re s e a rc h e rs tried to d e m o n s tr a te a h iera rch y of in tellig en ce am ong the races. The m ost notable in A ustralia were Berry and Porteus (1920, cited in Turtle 1991) for their com parative measures of cranial capacity and maze perform ance. D espite im plicit racist notions of eu ro p e an su p erio rity in m ental d ev elo p m en t, Po rteu s m ade im portant c o n te x tu a l o b s e rv a tio n s about ab o rig in al p e rfo rm a n c e on w estern tests (Turtle 1991). B rislin (1976, citing Porteus, B ochner, Russell & David 1967) show ed that when adequate attention was given to com m unication, rap p o rt and m o d ifica tio n of abstract p ro ced u res to m atch the real life e x p e rie n c e of a b o rig in a l su b jects, p e rfo rm a n c e on the Po rteu s Maze b ecam e e q u iv a le n t to that of eu ro p ean s for h e alth y ab o rig in als of a

sim ilar age. Similarly, Fry and Pulleine (cited in Turtle 1991) modified their instructions for the Porteus Maze and reported it to be a useful test for a b o rig in a ls fa m ilia r w ith the s to c k y a rd s o f the c a ttle industry. H ow ever, they concluded the test was too hard for aboriginal people in g e n e r a l.

New Directions and the Difference-Deficit Controversy

O p p o s in g e x p la n a tio n s for the c o m p a r a tiv e ly p o o r p e rf o r m a n c e on w e ste rn c o g n itiv e tests by in d ig e n o u s , s e m i- lite r a te or e co n o m ic ally d isa d v an tag e d people co n tin u e to p erm eate the c ro s s -c u ltu ra l literature and co n trib u te to co n tro v ersy (C ib o ro w sk i 1980). T he d eb ate reached racist notoriety in the early 1970's after A rthur Jen sen proposed that the higher normal IQ of white over black people was largely genetic (Darley, G lu ck sb erg & K inchla 1986). H ow ever, Jen so n m ay have spuriously assum ed the stimulus generality of his test m aterial and the equivalence of the construct of intelligence w ithin w estern c u ltu re and betw een its ethnic subgroups. The in tra-cu ltu ral study of F ra n k lin , Fulani, H enkind and Cole (1975, cited in C iborow ski 1980) is a sobering rem inder of the p otential fallacy of such assum ptions. They c o m p a re d black and white A m e ric an c h ild ren on free rec all tasks s e le c te d fro m stan d ard word category lists and a new list m ade up of categories used by lower class black children. Black children perform ed poorly when recall was based on the standard lists but did well when it was based on the new lower class b lack list. The rev erse o ccu rred for the m id d le to up p er class white children who perform ed poorly when recall was based on the lower class black list but did well when recall was based on the standard lists. For both groups of children poor perform ance was c h a ra c te rise d by lack of item clustering, a deficit previously associated w ith cognitive deficiency (Jenson & Fredericksen 1973, cited in Ciborowski 1980). A more realistic exp lan atio n for this outcom e was that both recall lists lacked stimulus g e n e r a lity w ith in w e ste rn c u ltu re . E ven w h e n the a s s u m p tio n s of stimulus generality and construct equivalence are valid, it can be difficult

to c o n tro l for all the v ariab les k now n to affe ct test p e rfo rm an c e in c o m p a ra tiv e studies.

D a v id so n (1983) claim ed re c e n t a p p ro a c h e s to c ro s s -c u ltu ra l research w ere more en lig h ten ed because they in v o lv e d e x p lo ra tio n of cognitive difference in order to u nderstand the underlying cognitive processes and fa c to rs a ffe ctin g vario u s p e rfo rm a n c e m e a s u re s (eg. so cial, cu ltu ral, educational, physiological, n eurological, m otivational, etc). This approach has led to the discovery of ab o rig in al c o g n itiv e strengths and avoided m uch of the eth n o cen tric bias of d e fic it o rie n ta te d resea rch . Turtle (1 9 9 1 ), describ ed a gradual sh ift in d irec tio n as early as 1939 from d eficit oriented research and p reo c cu p a tio n w ith cro ss-c u ltu ral measures of intelligence to more insightful studies which began to dem onstrate the cognitive assets of indigenous people (Turtle 1991, citing Fow ler 1940; Klich 1983, citing Lewis 1976, D avidson 1979; Klich & D avidson 1980; C ib o ro w sk i 1980, citing P ric e -W illia m s 1962, G lick 1968, Cole 1971, F ranklin et al 1975; Kearins 1976, 1988, 1990). H ow ever, in a scathing c o m m en ta ry on the status of A u s tra lia n a b o rig in al c o g n itiv e research, K lich (1 9 8 3 ) c o m p la in e d of in a d e q u a te s tu d ie s re p o r tin g ab o rig in al strengths. In his opinion research had largely rem a in e d deficit orientated with interpretations of cultural deficiency blam ed for the lack of western ed u catio n al ach ievem ent by ab o rig in al ch ild ren . K earney and M cElw ain (1976, p398) a few years earlier had reported a sim ilar inadequate data base "o f any depth". They c laim ed research on aboriginal cognition had b een too m e th o d o lo g ic a lly d e m a n d in g fo r so m e and so re c e n t an end eav o u r for others that it w as not unusual to find they had changed direction within a few years. B ryer (1976) noted few aboriginal studies h ad i n v e s tig a te d a d u lt c o g n it i v e f u n c tio n an d th a t m an y of the conclusions from research with children had only been assum ed to hold for the adults.

C o n t e m p o r a r y Approaches to Abori gi nal Cognition

Psychic Unity o f Mankind

According to several authors (Goodnow 1976; Brislin 1976; Sheehan 1976; C i b o r o w s k i l 9 8 0 ; Klich & Da vidson 1984), the search for a mythical ge ne ra l a d a p t a b i l it y fact or (ie. i n te l li g e n c e ) p r e o c c u p i e d m any early cros s-c ult ur al researchers. Irvine and Carroll (1980, citing Hunt 1973 and Ca r ro l l 1974) s ug g e st e d that p i o n e e r i n g r e s e a r c h in test alien c u l t u r e s u s e d only b lu n t i n s t r u m e n t s to e s t a b l i s h t h e i r g e n e r a l a d a p t a b i l i t y fact or. C o n t e m p o r a r y r e s e a r c h m e t h o d o l o g y and new d e ve lo pm e nt s in cognitive psyc ho log y have e n ab le d more recent cross-cultural research to assume perf or m anc e to be the product of universal cognitive processes which are mediated by personal, social, cultural, and other factors (Irvine & Carroll 1980; Davidson 1983). Lezak (1983 p21) c o n s i d e r e d "there is no gen era l intellectual f u n c t i o n , but rather many discrete ones that work together so sm o o th ly w h e n the brain is intact

th at the i n t e l le c t is e x p e r i e n c e d as a s i n g l e , s e a m l e s s a ttr ib u te ".

N e u r o p s y c h o l o g i c a l re s e a r c h has h e lp e d to r e d e f i n e the n a tu r e of i n te lli ge nc e by d em o n str ati n g that di ff eren ti al d e te r io r a ti o n of diverse p s y c h o l o g ic a l functions are in d e p e n d e n t of IQ w h e t h e r th rough brain injury, disease or aging (Lezak 1983). This human information processing model of performance has enabled us to assume that all cultures evolved to mee t spe ci fi c e n v i r o n m e n t a l d e m a n d s in a si m il a r m ann er . The problem solving style of its members should then be the manifestation of such adaptation and underlying universal cognitive processes. Cole and Scribner (1974, cited in Ciborowski 1980) supported such a formulation of the psychic unity of mankind, suggesting there was no evidence in the l it e ra t u r e o f any cu ltu re b e in g d e f i c i e n t in a b s t r a c t i o n , in f e r e n ti a l reasoning or categorisation processes. Blake (1991, p4) noted "no linguist has ever d i s c o v e r e d a language that a p p e a rs re m o t el y p ri m it iv e" and found ab o ri g i n al language v oc ab u la r y was q u an ti t at iv e l y e q u iv a le n t to that of an average english speak in g person. Fu r th e r m or e , Drin kwa ter

(1976) found the english dialect of mo nolingual aboriginal adolescents to have well-structured semantic systems and m e a ni n g f ul coding of verbal stimuli, albeit a somewhat limited vocabulary. Thus, in an appropriate cultural context the capacity to use any cognitive skill should be universal and the co g n it i v e abilities of i n d ig e n o u s p e o p l e should be no less primitive than their traditional and creole langua ges (Labov 1969, cited in Drinkwater 1976).

Different Learning Styles

Differences in problem solving style have been considered to account for d i f f e r e n c e s in w e s t e r n e d u c a t i o n a l a c h i e v e m e n t a n d c o g n i t i v e performance on cognitive tests alien to the culture being examined (Watts 1976; McIntyre 1976; Irvine & Carroll 1980; Ross 1984; Klich & Davidson 1984, citin g Har ris 1977). S e a g rim s a r d o n i c a l l y c o n c l u d e d that if aboriginal children had to becom e i nte lle ctu all y c o m p e te n t by western standards via western educational practices then they would have to be brought up by non-aboriginals (1977, cited in Klich & Davidson 1984). Kearins (199 0) in a study of the effe cts o f u r b a n i s a t io n fo und no difference in mem or y and direction finding skill between remote, semi- traditional aboriginal children and urban a b o ri g in al children of largely mixed descent, even though both p e rfo rm ed bett er than white controls. Traditional child rearing practices re s ist an t to acc u ltu rat io n may have pr oduced sim ilar and di stinctive p e r f o r m a n c e styles in the aboriginal children despite their geographical differences.

Cognitive Testing Approaches

Testing cognitive ability in non-western cultures can be divided into five t r a d i ti o n a l a p p r o a c h e s : P s y c h o m e t r i c ( P M ); P i a g e t i a n (PC); Field D if f er e nt ia tio n (FD); A n t h r o p o l o g ic a l C o g n i t i o n (AC); and Cog nitive Information Processing (CIP). Irvine and Ca rroll (1980) described the s i m il a r it i e s and d i f f e r e n c e s of t h es e a p p r o a c h e s and a d v o c a t e d a c on ve rg en c e betw een PM, AC and CIP for m or e valid cross-cultural

in v e s tig a tio n . A c c o rd in g to th ese a u th o rs th e PM a p p ro a c h o ffers m eth o d o lo g ic a l rig o u r th at is u n a v a ila b le to the PC school, but its constructs are often limited to the culture of origin. AC seeks stimulus or c o n c e p tu a l g e n eralitie s across c u ltu res th ro u g h c a re fu l o b serv atio n of n a tu rally o ccurring c o g n itiv e c o m p e te n cie s w ithin cu ltu res, but this is usually limited to single tests of such p henom ena w hose meaning remains q u e stio n a b le . This is the sam e p roblem for FD w hich can accurately categorise subjects from d ifferen t cultures but can only speculate about the m eaning of such partitioning. W hen com bined with the PM approach convergence of a num ber of these tests w ould assist interpretation of the meaning of their measures. Finally, CIP offers a theoretical framework for the m ental p rocesses underlying test m easures. W hen CIP is com bined with the rigours of construct validation offered by the PM approach and the cultural insights offered by AC, a more reliable interpretation of test score m eaning may follow.

Integrated Approaches

K lich and D av id so n (1 9 8 4 ) tried to in te g rate the PM , AC and CIP ap p ro ach es in research that so u g h t to d ev elo p a m odel of aboriginal c o g n itiv e function. T hey used Luria's n e u ro p s y c h o lo g ic a l model of the functional organisation of the brain to explain sim ilarity and difference in the perform ance style of aboriginal and white children on the Queensland T e s t (M c E lw a in & K e a rn e y 1970). T h e ir f a c to r a n a ly sis of QT p e rfo rm a n c e re v e a le d an id e n tic a l two fa c to r so lu tio n for both the aboriginal and nonaboriginal samples. The authors proposed this common fa c to r s tru c tu re re p re s e n te d sim u lta n e o u s and s u c c e s s iv e in fo rm a tio n processing ability. Previous AC research by the same authors showed that a b o rig in als and eu ro p e an s used d ifferen t m em ory c o d in g strategies to play card gam es (K lich & D av id so n 1984). S im ila rly , the cog n itiv e strategies used by aboriginal and white children in the QT study were not identical. Those of aboriginal children were com p arativ ely inefficient for

the successive processing tasks of the QT but more efficient than those of

white children for most of the sim ultaneous processing tasks. As the sub tests of the QT were pred o m in an tly su ccessiv e p ro ce ssin g tasks, white c h ild re n p erfo rm ed better than a b o rig in al c h ild re n ov erall. A lthough these findings do not prove underlying mental processes are the same for both cultures, they were consistent with Cole & Scribner's prediction that w hen a test has fu n ctio n al e q u iv a le n c e a cro ss c u ltu re s , no c u ltu ral d if f e r e n c e sh o u ld be found in basic c o m p o n e n t p r o c e s s e s of brain organisation (1974 cited in Klich & Davidson p l9 6 ).

Test i ng Ameri can Indians

Characteristic Performance Profile

M cS h an e and Plas (1984) ad v o cated the use of W e c h s le r in tellig en ce instrum ents to assess A m erican Indian intellectual deficits (and abilities) to enable prescriptive rem edial education. They d escrib ed a characteristic In d ia n p e rfo rm a n c e p ro file on these tests fo r w h ic h th ere was no adequate factor analytic explanation. A ccording to these authors an 8-19 p o i n t d i s c r e p a n c y on th e W I S C - R w a s t y p i c a l f o r I n d ia n v e rb a l/p e rfo rm a n c e IQ m easures w hile their g rea tes t stren g th s were in v is u a l- s p a tia l p ro c e s s in g . S im ila r v is u a l- s p a tia l s tr e n g th s have been observed in the perform ance of Australian aboriginal children on western psychom etric tests (Klich 1983; Kearins 1976, 1988, 1990). M cShane and Plas outlined a num ber of inter-related variables thought to affect Indian p erfo rm an ce and which should be inco rp o rated in any pred ictiv e model of Indian cognitive function. T hese in clu d ed p h y sio lo g ic al (eg. auditory acu ity and the role of O titis m edia, an e n d em ic m id d le ear disease; asy m p to m atic lead exposure; F o e tal A lco h o l S y n d ro m e and the direct e ff e c t o f a lc o h o l abuse on in te lle c tu a l f u n c tio n ) , n e u ro lo g ic a l (eg. h e m is p h e r e s p e c ia lis a tio n fo r la n g u a g e ), s o c io c u ltu r a l (eg. b ilin g u a l lan g u ag e orientation; non-verbal language preferen ces; acculturation; and child rearing style), age and sex.

I n t r a - c u l t u r a l Var ia bil ity

Brandt (1984) challenged the notion of using western intelligence tests with American Indian children, citing the lack of construct equivalence between the two cultures which could explain poor test performance. She considered the observations of M c Sh an e and Plas to be an artifact of the extreme variability in socio-cultural and linguistic skills of the American indian population. In particular, indians usually lived with other tribes in ethnic enclaves within reservations or in the larger white society. As each tribe had their own traditions and language, indian-english dialects were c o n s t r u e d along a c o n t i n u u m . S o m e d ia l e c t s had their own gr a m m a t i c a l rules i n de pe n d en t of st a n d a r d e n g li sh or their ancestral origins. Indians were som eti m es m o n o li n g u a l, bilin gu al or fluent in several langua ges and their living c o n d iti o n s r a n g e d fro m established towns with their own service structure to isolated comm un iti es without electricity or running water. Brandt co n si d er e d the degree of english language fluency and co mm un ic a tio n be tween the testee and tester (ie. sociolinguistic rules and conversational expectations) to account for most of the va ria bil ity in test p e r f o r m a n c e . She a rg u e d that the Indian population was too heterogeneous to assume stimulus generality for test i t e m s ( eg . i t e m d i f f i c u l t y ) a n d a l l e g e d t he i n s t r u m e n t w o u l d underestimate the abilities of Am e ric an Indians or fail to detect cases where re m e d ia l services were r eal ly w a r r an t ed . Sim ilarly, Davidson (1983, p276 citing Kearins 1976) c o n s i d e r e d the failure to replicate Kear in s s u p e ri o r visual m e m o r y p e r f o r m a n c e of Cen tra l Aus tralian aboriginal children over white children may have been due to " b e t w e e n and within community variability" of rele van t and extraneous variables.

T e s t i n g A u s t r a l i a n A b o r i g i n a l s

Norm-referenced Tests

In one of the few articles found on the subject, B adcock and Ross (1982) made a plea for more appropriate n eu ro psychological tests for Australian a b o rig in a ls . In d o in g so they b rie fly r a is e d the d if f e r e n c e - d e f ic it co n tro v ersy in the jo u rn al of the A u stra lia n P sy ch o lo g ist. They cited aboriginal hospital admission rates for alcoholism at 8 times that of n o n aboriginals (H ealth Com m ission of N SW , 1979) and were concerned that no c u ltu re -fa ir n e u ro p s y ch o lo g ica l tests w ere a v ailab le to assess those likely to be suffering from A R B D . They su g g ested practitioners were in a p p ro p ria te ly "extr apo la tin g f r o m e q u i v a l e n t e u r o p e a n - n o r m e d tests" in the absence of more suitable tests for aboriginals (p298). They were criticised the following year by Davidson (1983) for failing to be aware of c o n te m p o ra ry c ro s s-c u ltu ra l issues and new d e v e lo p m e n ts in co g n itiv e n e u r o p s y c h o l o g y .

Culture Sensitive A pp roa ch es

D avidson (1983) ack now ledged the need for m ore appropriate ways to assess brain d am age in aboriginals but reje cted the B adcock and Ross notion of norm -referenced tests. He considered culture to be one of many variables that can affect test perfo rm an ce and that incorporating all of these in a set of norms for aboriginals w ould be "u n p r o f i t a b l e " (p274). In ste a d , D a v id s o n r e c o m m e n d e d s e v e ra l a lt e r n a t iv e a p p ro a c h e s for clinical p ractice and future research. In p a rticu lar, he suggested there was no rea so n to reject the w ealth of tec h n iq u e s already available to assess localised brain damage in no n -ab o rig in als. Provided the cultural and language background of the patient w ere taken into account during adm inistration and interpretation, he saw no reason why they could not

be applied to aboriginals. For example, in relation to reading, writing and sp e ak in g p r o c e s s e s , D a v id so n a rg u e d : "It is most unlikely that such disorders require different be h a vi o u ra l a ss e s sm e n t s in different cultures,

or that their association with localised lesions w ou ld alter f r o m culture to

cu lt u re " (p2 75) . On a p p r o p r i a t e test m o d i f i c a t i o n s he su g g e st e d : "Disorders are, more than likely, task specific, not culture-specific. Their

a s s e s s m e n t r e q u i r e s a n u m b e r o f c a r e f u l l y a d a p t e d t as k s th a t are

linguistically and schematically suited to the culture in which they are

u se d " (p275).

E th n og r ap hi c A p pr o a c h

Davidson considered there was an urgent need to undertake ethnographic investigation of aboriginal brain damaged behaviour to gain an aboriginal pe rs p ec t iv e on d is t in c t io n s b e tw ee n n o r m a l a nd d e f i c i e n t b eh av i o u r . Behaviour in an everyday context can have a direct bearing on clinical as sessme nt and could help establish the criterion validity of modified n e u ro ps yc ho l og i ca l pr ocedures (cf. Du n lo p 1988). A c o m b i n a t i o n of modified clinical tests and observations of real life activities in a natural context would sample the cognitive processes likely to be disrupted by k n o w n or h y p o t h e s i z e d l o c a t i o n s o f b r a i n d a m a g e . D a v i d s o n r e c o m m e n d e d using Lu ria 's p r o ce du r al m e t h o d of n e u r o p s y c h o l o g i c a l enquiry for aboriginals. This woul d in vol ve the sys tem ati c testing of hypotheses about brain imp ai rm en t involving tests, tasks and real life observations. Assuming the universal organisation of brain structure and function across cultures, this approach would lead to inferences about the f u n c t i o n a l i n t e g r i t y of br ain s y s t e m s . S y m p t o m s and p o o r task p e rf o r m a n c e may r e p r e se n t d i sr u p t io n of n o r m a l c o g n it i v e p ro ce ss es (Marin, Glenn & Walker, 1982).

N e u r o p s y c h o l o g i c a l - I n t e l l i g e n c e T e s t D i s t i n c t i o n

Neuropsychological Tests

These tests are designed to identify discrete cognitive functions within 4 m ajor in tellectu al classes, d e p en d in g on the type of test used (Lezak 1 9 8 3 ). S im p le te s ts i d e n t i f y m o r e s p e c i f i c f u n c t i o n s w h ile m ultidim ensional tests tap broader more com plex functions. However, all functions are in te rd ep e n d en t and no single test can id en tify a unitary function (W alsh 1985). D avidson (1983) d escrib ed NP assessm ent as a sy s te m atic p ro ce ss o rien ted p ro c e d u re th at d o e s not rely on norm- re fe re n c in g and is u sed to te s t h y p o th e s e s r e la te d to im p a irm e n t expected from know n or su sp ected areas of brain dam age. Tests are usu ally c h o sen for th eir s e n s itiv ity to p a rtic u la r c o g n itiv e p rocesses which if disrupted by structural dam age will result in test errors or loss of problem solving efficiency. They can be used to identify neurological or n e u ro p s y ch o lo g ica l sy n d ro m es, assess deg ree of im p a irm e n t, predict disability and assist rehabilitation.

Intelligence tests

In c o n tra s t, in te llig e n c e tests are u su a lly d e s ig n e d to sa m p le skill c o m p e te n c e s and are b a sed on m o d els of in d iv id u a l d iffe re n c e or deviation from a reference m ean. The reference m ean is usually adjusted for the sig n ific an t in flu e n ce o f o th er v aria b le s (eg. age, sex, so c io econom ic status, sch o o lin g , a c c u ltu ra tio n , etc.). S ta n d ard p sy ch o m etric tests (eg. WAIS-R and W M S) often tap only gross brain function and may be in sen sitiv e to localised d am ag e such as fro n to -te m p o ra l dysfunction found in head injury or chronic alcohol abuse (Shores, Kraiuhin, Zurynski, Singer, Gordon, M arosszeky & Fearnside 1990, citing Stuss 1987, Walsh 1985, L ezak 1988). For this reaso n they have been used to estim ate p rem o rb id in te lle ctu al fu n ctio n a g ain st w hich c u rre n t NP p e rfo rm an ce can be com pared (Lezak 1983; Ross 1984; W alsh 1987; Parsons, Butters,

C o m b in ed A p p ro a ch : Im p a irm en t Index

L u r ia 's q u a li t a t iv e m e th o d o f N P e n q u ir y has b een c o n s i d e r e d fu n d am en tally d ifferent to the q u a n titativ e NP test battery approach of the p sy ch o m etric school (G ilandas, T ouyz, B eum ont & G reenbern 1984). A c o n tro v e rsia l attem pt to co m b in e the two ap p ro ach es in the Luria- N ebraska NP Battery produced an index of cog n itiv e im p airm en t which incorporated norm -referencing (G olden 1981, cited in Lezak 1983). Ross

(1 9 8 4 , c itin g H o r a n l9 6 6 ) th o u g h t the p s y c h o m e tric Q u e e n s la n d T est could be sim ilarly used for aboriginals as "a usefu l index f o r organic c en tra l im p a irm e n t, p o ten tia l, a n d also a p o s s ib le index f o r rem edial

health m easures" (p374). How ever, D avidson (1983) considered the test too i n s e n s i ti v e to d i f f e r e n t i a t e n e u r o lo g ic a l i m p a i r m e n t fro m the p erfo rm an ce of norm al ab o rig in als, given the co n fo u n d in g in flu en ce of social, cultural and theoretical considerations on its scores.

P r o b l e m S o l v i n g

H ierarchy o f Tactics

M cElw ain (1976, p 133) proposed that when an individual is faced with a problem to solve he or she has a 'hierarchy o f tactics' f o rm a lly a v aila b le to approach the problem. W ithin any culture the m ost capable individuals may have larger tactic hierarchies available to them than the less capable (or less intelligent). The tactics or strategy at the top of such a hierarchy is likely to be used first and for the m ost cap a b le ind iv id u al it will p ro b ab ly be the m ost e ffe ctiv e or e ffic ie n t tac tic for the p res crib ed problem . The order of tactics in a hierarchy may be culture bound with those at the top evolving to m eet the com m on environm ental dem ands of that culture. Outside the individual’s own culture, his tactic of first choice may n o t be ap p ro p riate. T his w o u ld e x p lain p e rfo rm a n c e d ifferen c e s between cultures. On the other hand, even when perform ance on similar

activities is the same for individuals from d ifferen t cultures, they may have ev o k ed d ifferent tactics to solve the same p ro b lem s (D avidson &

Klich 1984). For example, aboriginals may use d ifferent verbal coding strategies to solve unfam iliar p roblem s (R oss 1984; Foggitt, M angan & Law 1972). M oreover, sim ilar p e rfo rm an c e by in d iv id u als w ithin the same culture does not n ecessarily m ean that they have used the same cognitive processing tactics in an equiv alen t context. Klich and Davidson (1984) found both their aboriginal and w hite ch ild ren used a range of tactics to solve the p roblem s p o se d by the Q u e e n s la n d T est (QT). M cElw ain believ ed the problem s p o sed by w estern p sy ch o lo g ical tests were usually not suited to aboriginals. If info rm atio n about the task and its operation is ambiguous and subjects are unable to check the accuracy of their response, their tactic of first choice may be inappropriate. Even with explicit goals and m inim um c o m m u n icatio n requirem ents, M cElwain & K earney (1970) found a b o rig in al p e rfo rm a n c e on th e ir QT to be dependant on degree of western contact.

Effect of Acculturation

Acculturation is the process of social change associated with the dominant culture's influence upon the m em bers of a m inority culture and generally involves in flu e n ce during c h ild h o o d by e u ro p e a n s and the learning of w e ste rn w ays (K e a rn e y & F i t z p a tr ic k 1976, c itin g B ru n e r 1956). Fam iliarity with western problem solving tactics and the order in which they occur in M cE lw ain 's h iera rch y w o u ld d e p e n d on the e x ten t of w estern acculturation. This in turn w ould dep en d on degree of western c o n ta c t th ro u g h e u ro p e an m ed ia, e d u c a tio n , w o rk or p ro x im ity to european urban settlem ent (ie. urbanisation). M cIntyre (1976) com pared the problem solving style of rural and urban children of both aboriginal and e u ro p e a n d e s c e n t. He fo u n d p e r f o r m a n c e r e l a te d m o re to u rb an isatio n than culture as there w ere no d iffe re n c e s betw een rural aboriginal and rural white children on literacy or Q T performance. As the

QT was designed to predict capacity to learn w estern skills and was made up of basically abstract w estern tasks, its p erfo rm an c e profile could be used as an index of western acculturation (M cElw ain & Kearney 1970).

M o d i f y i n g T e s t C o n t e x t

Clarify M i s u n d e r s t a n d i n g s

Ciborowski (1980) suggested that poor cognitive performance on western tests by i n d i v i d u a l s f r o m a n o t h e r c u l t u r e wa s l a r g e l y due to m is u n d er s ta n d in g b etw een testee and tester. D i f f e r e n t e xp ect ati on s or interpretations of the test experience can advers ely affect psychological test p e r f o r m a n c e . The f o llo w in g studies il l u st r a te how c ha ng in g the c o n t e x t of the test s i t u a t i o n can i m p r o v e ( o r d i s a d v a n t a g e ) the p e r f o r m a n c e of p e o p l e u n f a m i l i a r wi th w e s t e r n tests of co g n it i v e function. Cole called this " e x p e r im e n t i n g with the e x p e r i m e n t " (1971, cited in Ciborowski 1980, p290).

Familiar Stimuli

Price-Williams (1962, cited by Ciborowski 1980 and Klich & Davidson 1984) c h a n g e d the c o n te x t of a P i a g e t i a n h i e r a r c h i c a l cla ss ifi cat ion experiment with Tiv children from Nigeria by using familiar objects from their env ironm ent (ie. various animal toys and plants) instead of objects from western culture. As a result, Tiv children were just as capable of grouping the more culturally familiar objects in different ways as were white children. However, the same Tiv children were not as capable as white c hi ld r en when ab str ac t shapes were used (ie. circle, triangle, square, etc) Co m p are d with natural objects the abstract test material lacked stimulus generality.

The Franklin et al study is an example of po o r stimulus generality for words (see page 4). Black American children recalled more words than white children when lists were made up of categories used by lower class black children (1975, cited in Ciborowski 1980).

Franklin, Fulani, Hen kin d and Cole (1975, cited in Ciborowski 1980) described a no the r study co mp ar in g black and whi te Am erican children

on free recall tasks selected from standard word category lists and a new list m ade up of categories used by low er class black children. Black children perform ed poorly w hen recall was based on the standard lists but did well when it was based on the new low er class black list. The rev e rse o ccu rred for the m id d le to u p p er cla ss w h ite c h ild ren who perform ed poorly when recall was based on the lower class black list but did well when recall was based on the standard lists. For both groups of children poor perform ance was characterised by lack of item clustering, a d e fic it p r e v io u s ly a s s o c ia te d w ith c o g n itiv e d e f i c ie n c y (Je n so n & F r e d e r ic k s e n 1973, c ite d in C ib o ro w s k i 1980). A m o re re a lis tic explanation for this outcom e was that both rec all lists lacked stimulus generality w ithin w estern culture.

A p p r o p r i a t e I n s t r u c t i o n s

Glick (1962, cited by C iborow ski 1980, p283) d e m o n strated the effect of different cultural expectations on a sim ilar c la ssificatio n experim ent with Kpelle tribesm en from the west coast of Africa. U sing standard Piagetian instruction the Kpelle sorted fam iliar objects in ways that they considered to be 'clever' in their cu ltu re (ie. b ased on p e rc e p tu a l or functional rela tio n s). H ow ever, 'i n t e l l i g e n t ' c o n c e p t u a l c l a s s i f i c a t i o n r e q u ir e d taxonom ic groupings of the objects, so the K pelle perfo rm an ce appeared deficient by western standards. W hen one subject was asked to sort in a 'stupid' way, his perform ance im proved d ram atically . It appears that the concept of intelligence in Kpelle and western cultures was not equivalent. The use of w estern tests to m easure the K pelle co n cep t of intelligence w ould have been like trying to m easure the tem p eratu re of the sun with a therm om eter designed for use on earth (Irvine & Carroll 1980).

Story Fo rmat

B ryer (1976, p303) tested A ustralian ab o rig in al c h ild ren from Aurukun on P ia g e tia n m atrices and fo u n d the task u n d e r s ta n d a rd Piagetian in stru ctio n s to be too vague fo r the ch ild ren . W h en she changed the

procedure to a sto ry f o r m a t the c h ild re n p ro d u c e d m ore a p p ro p riate solutions and explanations. A lth o u g h this train in g p ro ced u re m ade the test more acceptable to her children Bryer still thought it was a culturally inappropriate context for ability testing.

Tr ai ned Res ponse

C ole, F ra n k e l and Sharp (1 9 7 1 b , c ite d in C ib o ro w s k i 1980) made m o d ificatio n s to their p ro ced u re for assessing the free recall memory ability of Kpelle tribal children and adults. U nder standard instruction the K pelle re c a lle d very few f a m ilia r item s and sh o w ed no ev id en ce of a b strac t c o n c e p tu a l learn in g c o m p a re d to w e ste rn su b je cts. H ow ever, when p re s e n ta tio n of the o b jec ts in v o lv e d sp a tia l p ro m p tin g for the object category, Kpelle subjects used conceptual clustering to recall more objects than they had previously. Irvine and C arroll (1980) advised that responses required in the test p e rfo rm an ce m ust be learnt, not assumed; and w here necessary these sh o u ld be visually d em o n strated . Cole et al appear to have follow ed these p rin cip le s of sound c ro s s-c u ltu ral data collection with their use of chairs, over which the objects were held to prom pt conceptual learning. T hus, by changing the c o n tex t of the test p rocedure the authors were able to in fer there w ere no differences in cognitive ability between these radically d ifferent cultures.

Gui de-lines f o r Cross- Cul t ural Testing

A c co rd in g to Irvine and C a rro ll (1 9 8 0 ), the e th n o c e n tr is m and self fulfilling prophecy of past deficit research can be avoided when imposing a w estern theoretical fram ew o rk in cro ss-cu ltu ral research . To achieve this they reco m m en d ed re s ea rch e rs adhere to th e o ry -b a s e d propositions of c o g n itiv e d iffe re n c e ra th e r than d e fic it b a s e d in te r p r e ta tio n s of perform ance. M oreover, they suggested research ers adopt more rigourous m u ltiv a r ia te c o n tro l o v e r the m e th o d s they use to a p p re c ia te the influence of "sc ho ol ing , urbanism, work experience and learning" ( p 2 0 6 ) .