PHOSPHATASE LEVELS IN PATIENTS WITH CHRONIC

PERIODONTITIS BEFORE AND AFTER NON -SURGICAL

PERIODONTAL THERAPY: A COMPARATIVE STUDY

A Di ss ertat ion submi tted

in partial fulf ilment of the requir ements for the degree of

MASTE R O F DENT AL SURGE RY

BRANCH – II PE RIO DO NTOLO GY

THE TAMIL NADU DR. M.G.R. ME DI CAL UNI VERS ITY CHENNAI- 600032

DE PART MENT O F PE RIO DO NTOLO GY CERTI FICATE

This is to cert if y t hat Dr. M.J.RENGANATH, Pos t Graduat e student (2014 -2017) in the Departm ent of Peri odontics, Adhi paras akthi Dental Coll ege and Hospital, M elm aruvathur – 603319, has done this diss ert ati on titl ed “EVALUATION OF SERUM AND SALIVARY ALKALINE PHOSPHATASE LEVELS IN PATIENTS WITH CHRONIC PERIODONTITIS BEFORE AND AFTER NON-SURGICAL PERIODONTAL THERAPY: A COMPARATIVE STUDY” Under our di rect guidance and supervision in parti al ful film ent of t he regul ati ons l ai d down b y the Tami lnadu Dr.M.G.R Medi cal Universit y, Chennai – 600032 fo r M DS., (Branch - II) P eriodontology degree ex ami nati on.

Co-Guide Guide

Dr.N. Manisu ndar, MDS ., Dr.T. Ramak rishnan, MDS., Reader Professor & Head

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

I am extremely grateful to Dr.T.Ramakrishnan MDS., Guide, Professor and Head, Department of Periodontology , Adhiparasakthi Dental College and Hospital, Melmaruvathur. Words cannot express my gratitude for his quiet confidence in my ability to do the study, his willingness to help to clear the stumbling blocks along the way and his tremendous patience till the end of the study.

It is my duty to express my thanks to my Co -Gui de Dr.N.Mani Sundar MDS., Reader for his expert guidance and moral support during the completion of this study. I consider myself privileged, to have studied, worked and completed my dissertation under them in the department.

My sincere thanks to Dr.S.Th illainayagam MDS. , our beloved Principal, Adhiparasakthi Dental College and Hospital, Melmaruvathur for providing me with the opportunity to utilize the facilities of the college.

I thank our Correspondent Dr.T.Ramesh, MD., for his vital encouragement and support.

I am extremely thankful to my teachers Dr.Vidyasekar MDS., Reader, Dr.M.Ebenezer MDS., Senior lecturer,Dr.P.SivaRanjini MDS., Senior lecturer, for their valuable suggestions, constant encouragement and timely help rendered throughout this study.

I am extremely grateful to Dr.S.Sakthidasan MD., Professor, Department of Biochemistry, MAPIMS, Melmaruvathur for granting me permission to conduct the study in his department and helping me to bring out my study.

I thank Dr.S.Pandian, Madras Veterinary College and hospital, Vepery, Chennai, for helping me with the statistics in the study.

I also wish to thank my post graduate colleague, Dr.S.Anitha devi and I warmly acknowledge my juniors Dr.P.Shobana, Dr.J.Irudaya Nirmala, Dr.R.Dhivya and Dr.P.Indumathi for their help and support.

A special mention of thanks to all my patients for their consent, co-operation and participation in this study.

I thank ALMIGHTY GOD for answering my prayers and making me what I am today.

I owe my gratitude to my father Mr.K.Murugan and my mother Mrs.M.Jeyasree who stood beside me during my hard time and sacrificed so much to make me what I am today. I also thank my loving brother Mr.M.J.Kailash for his constant help and encouragement throughout my career.

My acknowledgement wouldn’t be complete without mentioning my well-wishers Dr.T.C.Giri MDS., Dr.P.G.Senthilkumaran MDS., Dr.B.Sivaramakrishnan MDS., for being my strength, by giving me continual support all the time.

DECLARATION

TIT LE OF THE DISS ERTAT ION

Evaluation of s erum and s ali var y alkali ne phos phat ase level s i n pat ients with chronic periodonti tis before and aft er non -surgi cal periodont al therap y: A comparative s tud y P LACE OF THE S TUDY Adhi paras akt hi Dent al C oll ege and

Hospital, Melm aruvathur – 603319 DUR AT ION OF THE

COURS E 3 years

NAME OF THE GUIDE Dr.T. Ramakri shnan, MDS., NAM E OF C O-GU ID E Dr. N. M anisundar, MDS.,

I hereb y decl are that no part of the di ss ert ati on will be uti li zed for gai ning financial assist ance or an y promoti on wit hout obt aining prior permi ssion of the Pri nci pal, Adhiparas akthi Dent al C ol lege and Hospital, Mel maruvathur – 603319. In addition, I declare t hat no part of this work wil l be published eit her in print or in el ect ronic medi a without t he gui des who has been acti v el y invol ved i n dis sert ation. The aut hor has the ri ght to res erve for publis h work sol el y with the permiss ion of the Princi pal , Adhi parasakthi Dent al College and Hospital, M elm aruvathur – 603319

Co-Guide Guid e & H ead of d epartmen t

BACKGRO UND:

Diagnosis of the active phas e of peri odont al dis eas e and identif yi ng the pat ients at risk for acti ve di seas e i s bei ng a chall enge for cli ni cal investi gat ors . The t raditi onal met hod of diagnosi ng periodonti tis one i ncl udes assessm ent of clini cal param et ers and radiographic aids t o evaluat e the peri odontal tis sue dest ruction. Sali va has the pot ent ial to be us ed as t he di agnosti c flui d for oral diseas e. It s eas y m et hod of collection through non -i nvasi ve methods. Evaluati on of ALP b y sim plified method of s pect rom etr y and i ts cheaper anal ys is cost makes the biom arker ALP as a resil ient and reliabl e one for th e diagnos is of peri odontal dis ease activit y

AI M:

The aim of t his stud y is to compare t he quantit ative level s of Alkaline phosphat as e in sal iva and serum before and aft er s caling and root pl ani ng in pat ients with chroni c generali sed periodontit i s.

MATE RI ALS AND METHO DS:

A t otal number of 50 subject s (40 with chronic generali sed periodonti tis and 10 periodont all y healthy volunt eers) of 30 t o 50 years were included in the stud y. Aft er getti ng the informed consent si gned, all the indi viduals parti ci pated in the stud y were su bject ed t o measurement of cli nical parameters such as OH I -S, Gingi val i ndex, probing depth and CAL and then saliva and blood sam ple coll ect ion was done and anal ysed for A LP l evels b y s pect rom et r y. The clinical paramet ers, s ali va and serum ALP were re-eval uat ed after 30 da ys foll owi ng phas e 1 peri odont al therap y. The resul ts were st atisti call y anal ys ed us ing paired t t est and One -wa y ANOVA.

RESULTS :

serum A LP level s were si gni fi cantl y decreas ed following phas e 1 periodont al therap y along wit h improvem ent in cli nical param et ers t hus exhibiti ng a posit ive correl ati on between cli nical param et ers with bot h sali va and serum ALP l evels. P val ues from the st atis t ical t est s pres ent ed were found to be st atis ticall y hi ghl y si gnifi cant at P-value .000**

CONCLUS ION:

CONTENTS

S.NO TITLE PAGE

No.

1. INTRODUC TION 1

2. AIM AND OBJ EC TIVES 4

3. GENER AL R EV IEW 5

4. REV IEW OF LITER ATURE 8

5. MATER IA LS AND METHODS 29

6. RESULTS 46

7. DISC USS ION 55

8. CONC LUS ION 65

9. REFERENCES 68

LIST OF PICTURES

Fig.No TITLE PAGE

No. 1. Chroni c general ized periodonti tis pre -operat ive 1 40 2. Chroni c generalized periodontitis pre -operati ve 2 40 3. Chroni c generalized periodontitis pre -operati ve 3 40 4. Probi ng depth >5mm at bas eline 41 5. Fol lowing non -s urgi cal therap y 1 41 6. Fol lowing non -s urgi cal therap y 2 41 7. Fol lowing non -s urgi cal therap y 3 42 8. Probi ng depth aft er phas e 1 periodont al therap y 42

9. Collecti on of blood 42

10. Collecti on of s aliva 43

11. Collect ed blood sam ple 43

12. Collect ed s aliva s am ple 43

13. Cent ri fuge m achi ne 44

14. Cent ri fuged s aliva and s erum sampl es 44

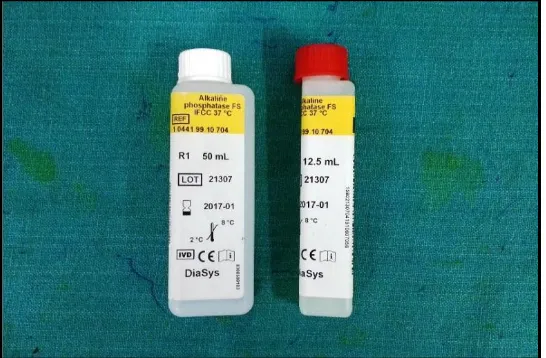

15. ALP kit (Di as ys ®) 44

16. Semi aut o anal ys er for ALP estim ation 45

[image:9.595.87.514.136.674.2]LIST OF TABLES

Table.No TITLE PAGE

No. 1. Mean change in OHI-S s core from baseline t o

post -operative i n st ud y group

48

2. Mean change in G I s core from bas eline t o post -operative in s tud y gr oup

49

3. Mean change i n probing depth & C AL from bas eli ne to pos t -operative i n stud y group

50

4. Compari son of m ean bas eli ne s ali va & serum ALP l evels between control group and stud y group

51

5. Comp ari son of m ean bas eli ne s ali va & serum ALP values wit h post -operative A LP values of stud y group

52

6. Compari son of m ean bas eli ne s ali va & serum ALP values of cont rol group with post -operative ALP val ues of stud y group

LIST OF CHARTS

Chart.No TITLE PAGE

No. 1. Mean change i n OHI-S s core from bas el ine t o

post -operative i n st ud y group

48

2. Mean change in G I s core from bas eline t o post -operative in s tud y gr oup

49

3. Mean change in probing depth & CAL from bas eli ne to pos t -operative i n stud y group

50

4. Compari son of m ean salivar y ALP l evels i n control group wit h baseli ne and post -operati ve ALP l evel s of s tud y group

54

5. Compari son of m ean s erum ALP levels in control group wit h baseli ne and post -operati ve ALP l evel s of s tud y group

LIST O F ABB REVATIO NS

ACP : acid phosphat ase ALP : alkaline phosphat as e ALT : al anine ami not ransferase AST : aspart ate transferase

BOP : bleedi ng on probing

BUN : blood urea nit rogen Ca : calci um

CAL : clini cal att achm ent l evel CEJ : cementoenam el j unct ion C I-S : calculus index score CK : creatine kinase

CP ITN : comm unit y periodont al i ndex of treatm ent needs CS : chondroiti n sulphat e

DI-S : debris index s core

DNA : deox yribose nucl ei c acid

ED : est rogen -defi cient ES : est rogen -suffi ci ent

GC F : gi ngi val crevi cul ar fl uid GGT : gamm a glut amil transferas e GI : Gingi val Index

HH : h ypergonadot ropi c hypogonadis m

IFCC : Int ernational Federat ion of C lini cal Chem istr y IL-1β : Int erleukin -1β

K : Potas sium

LDH : lactate deh ydrogenase

OH I-S : oral h ygi ene index -si mplifi ed SRP : scaling and root pl aning

1

INTRODUCTION

Chronic periodontitis has been defined as “an infectious disease resulting in inflammation within the supporting tissues of the teeth, progressive attachment loss, and bone loss.

Although periodontitis is an infectious disease of gingival tissue origin, changes that occur in the bone are crucial as the alveolar bone destruction is responsible for tooth loss. The most common cause of alveolar bone destruction in periodontitis is the extension of inflammation from the marginal gingiva to the underlying periodontal tissues.1

Biochemical markers can detect inflammatory changes in short period of time whereas longer period is required to detect measurable changes in bone density using radiographs.

Salivary constituents for diagnosing periodontal dise ase includes enzymes and immunoglobulins, hormones of host origin, bacteria and bacterial products, ions, and volatile compounds.2

2

ALP is a hydrolase enzyme responsible for removing phosphat e groups from many types of molecules and is a marker of bone metabolism. It is a me mbrane -bound glycoprotein produced by various number of cells, such as polymorphonuclear leukocytes, macrophages, fibroblasts and osteoblasts, within the area of the periodontium and gingival crevice.3

Studies demonstrated that the elevated serum ALP level is associated with patients with chronic kidney disease .4 Studies have also shown increased ALP activity in Pos t-menopausal women with periodontitis compared with non -periodontitis individuals.5

ALP is very important enzyme in the periodontium, as it is part of normal turnover of periodontal ligament, root cementum and maintenance, and bone homeostasis.

Various studies have assessed the levels of salivary ALP with respect to gingivitis, chronic periodontitis and correlation with clinical parameters. But there is lagging evidence regarding the comparative effects of ALP in serum and saliva following periodontal tr eatment.

3

findings in the study conducted by Todorovic et al. 7 that there was an increased activity of salivary ALP in patients with periodontal disease in relation to periodontally healthy group. The study group further showed a positive correlation betw een the salivary enzyme activity and gingival index values thereby indicating that ALP levels of an individual may best serve as a mark er in periodontal treatment pla ning and monitoring.8 , 9

4

AIM AND OBJECTIVES

The aim of this study is to compare the quantitative levels of ALP in serum and saliva before and after scaling and root planing in patients with chronic generalised periodontitis.

For this purpose, the following objectives were undertaken:

1. To evaluate and compare the saliva and serum ALP levels in chronic generalized periodontitis patients with that of periodontally healthy individuals.

5

GENERAL REVIEW

ALP is a me mbrane -bound glycoprotein produced by numerous cells, such as osteoblasts, macrophages, polymorphonuclear leukocytes and fibroblasts within the area of the periodontium and gingival crevice. ALP activity in serum has been extensively studied for the past few years, and it was suggested that ALP allows bone mineralization by releasing an organic phosphate, contributing to the deposition of calcium -phosphate c omplexes into the osteoid matrix. ALP might also promote mineralization by inorganic pyrophosphate hydrolyzation, which acts as a potent inhibitor of hydroxyapatite crystal mineralization and dissolution, within the extracellular calcifying matrix vesicles .1 0

In general, accelerated bone loss is related to an increased bone turnover rate, accompanied by increased levels of serum and urine biochemical markers of bone turnover, such as collagen cross -links, alkaline phosphatase (ALP), and osteocalcin.

6

DIAGNOSTIC SIGNIFICANCE OF ALP

Higher levels of ALP is having more value for diag nostic significance in the evaluation of hepatobiliary and bone disorders. In hepatobiliary disorders, elevations are seen more predominantly in obstructive conditions than in hepatocellular disorders. In bone disorders, elevations are seen when there is i nvolvement of the osteoblasts.

In biliary tract obstruction, ALP levels range from 3 to 10 times due to increased synthesis of the enzyme induced by cholestasis. In contrast, 3 fold increase is seen in hepatocellular disorders like hepatitis and cirrhosi s.

The bone isoenzyme increases due to potent osteoblastic activity and also the levels are normally elevated in children during periods of growth and in adults older than age 50 years, where an elevated ALP level may be difficult to interpret.

Individuals who have blood group B or O shows presence of intestinal ALP isoenzyme in serum. Furthermore, in these individuals, increases in intestinal ALP occur after consumption of a fatty meal. Increased levels are also found in patients undergoing chro nic hemodialysis.

7

returns to normal within 3 days to 6 days. Elevations also may be seen in complications of pregnancy such as hypertension, preeclampsia and eclampsia, as well as in threatened abortion.

Elevated ALP levels may be seen in a variety of bone disorders. Conceivably the highest elevations of AL P activity occurs primarily in Paget’s disease (osteitisdeformans). Other bone disorders including rickets,osteomalacia, hyperparathyroidism, and osteogenic sarcoma were also documented with increased ALP levels. In addition, increased levels are seen in t he case of healing bone fractures and during periods of physiologic bone growth. 1 3

ALP levels are significantly decreased in the inherited condition of hypophosphatasia. Subnormal activity is due to the absence of the bone isoenzyme and results in inad equate bone calcification.

ALP levels have often been evaluated in gingival crevicular fluid (GCF) to validate the relationship between periodontal conditions and disease activity.1 2 , 1 3

8

REVIEW OF LITERATURE

The diagnosis of active phases of periodontal disease and the identification of patients at the risk for active disease are challenges for clinical investigators and practitioners alike. Researchers are confronted with the need for innovative diagnostic te sts that focus on the early recognition of the microbial challenge to the host. Optimal innovative approaches would correctly determine the presence of current disease activity, for future periodontal breakdown and to evaluate the response to periodontal i nterventions. Hence, a new paradigm for periodontal diagnosis would ultimately improve the clinical management of patients with periodontal disease. 1 6

SALIVA IN THE FIELD OF DIAGNOSIS: 1 7

Analysis of blood and its compounds has been used for several decades for lab diagnostic procedures. However, other biological fluids are also utilized frequently for the diagnosis of disease, for example, urine, cerebrospinal fluid and thus saliva which could offer some distinct advantages in certain situations.

9

circulation. This makes saliva as a potentially valuable fluid for the diagnosis of various systemic diseases.

There are 3 major salivary glands (Parotid, submandibular and sublingual) that secrete saliva into the oral cavity. Saliva from these glands provides different mixtures of serous and mucinous derived fluid and is primarily useful for the detection of gland spe cific pathology.

Whole saliva, by contrast is composed by a mixture of oral fluids from the major salivary and minor salivary glands and also contains constituents of non salivary origin, including Gingival Crevicular Fluid (GCF), serum transudate from th e mucosa and sites of inflammation, epithelial and immune cells, food debris and many microbes. Whole saliva is most frequently studied because, its collection is easy, non -invasive and rapid to obtain without the need for specialised equipment.

Unstimulated saliva is commonly collected by the draining method, where the subject’s head is tilted forward so that saliva moves towards the anterior region of the mouth and the pooled saliva is drooled into a wide sterile container. To date, unstimulated whole saliva has been used in the majority of diagnosis studies.

SALIVARY BIOMARKERS OF PERIODONTAL DISEASE:

-10

invasive to collect and generally readily abundant. However, few studies have longitudinally monitored salivary biomarker profiles in patients with respect to periodontal status or determined if salivary biomarkers accurately represent periodontal disease status over time, its concentration of analytes should diminish in response to periodontal therapy.1 8

11

“Potential biomarkers” are defined using identical crit eria to robust biomarkers with the exception that there are 2 replicated cross -sectional studies showing disease discrimination in addition to possible supporting evidence from longitudinal studies but for which there may be limited contradictory studies. It is accepted that the entries in the robust and potential categories may be interchangeable depending on the existence of further studies which remain unpublished for commercial reasons.

“Uncertain biomarkers” are proteins for which there are only singl e study showing discrimination of periodontitis or for which there are several studies from which the evidence is contradictory.

“Unlikely biomarkers” are those proteins for which there are 3 or more studies which fail to provide evidence for an associati on with periodontitis in the absence of any evidence to the contrary. 1 9

MARKERS OF ALVEOLAR BONE LOSS:

12

Badersten A et al., 1981 2 0

Investigated healing after non -surgical periodontal therapy in patients with periodontal pockets depth of 4 -7mm in 15 patients. Patients were treated by supra and subgingival scaling either with hand or ultrasonic instruments. Clinical parameters like plaq ue scores, bleeding on probing, probing pocket depths and probing attachment levels were evaluated. There was improvement in clinical parameters during the initial 4 –5 months after start of therapy and then a little change occurred during the rest of the 1 3-month observation period. Total of 106 sites demonstrated probing pocket depths ≥ 6 mm. At 13 months only 13 such sites were observed. The results revealed that the conservative treatment of patients with 4 –7 mm deep pockets shown better clinical outcome s in the study, provided with the raise of question to what extent nonsurgical therapy is feasible also in patients with severely advanced lesions.

Isidor F et al., 1984 2 1

Evaluated the effect of root planing as compared to that of

surgical periodontal treatment in 17 patients with advanced periodontal

disease. Following initial examination, the teeth were scaled and the

patients were given instruction in performing proper oral hygiene. The

hygienic phase for the individual patient was continued until less than

20% of the tooth surfaces demonstrated plaque at 2 succeeding

appointments. After re -assessment of the periodontal status, 1 side in

both the maxilla and mandible was treated with modified Widman flap

13

reverse bevel flap surgery was used. Bone contouring was not

performed in any of the surgical procedures. The last quadrant was

subjected to meticulous root planing under local anaesthesia .

Subsequently, the patients were recalled every second week for

professional tooth cleaning. The periodontal status of each patient was

assessed at 3r dand 6t h months following treatment. Clinical gain of

attachment was obtained following all 3 modalities, but root planing

resulted in slightly more gain of attachment than the 2 surgical

procedures.

Ramfjord SP et al., 1987 2 2

14

Greenstein G 1992 2 3

Addressed the advantages and limitations of non -surgical periodontal therapies to treat patients with mild to moderate chronic periodontitis by controlled clinical trials and assessed the efficacy of following treatment methods like mechanical instrumentation, ultrasonic debridement, supragingival and subgingival irrigation along with local drug delivery and systemic antibiotic therapy, hos t modulation therapy and concluded that most patients with mild to moderate periodontitis can be treated with non -surgical therapy.

Haffajee AD et al., 1997 2 4

Examined the effect of SRP on clinical and microbiological

parameters in 57 subjects with adult periodontitis. Clinical and

microbiological examination was done prior to and 3, 6 and 9 months

after full -mouth SRP. Clinical parameters included plaque, redness,

suppuration, BOP, pocket depth and attachment level. Subgingival

plaque samples for the pres ence and levels of 40 subgingival taxa were

determined using whole genomic DNA probes and checkerboard DNA

-DNA hybridization. Sites with pre -therapy pocket depths of <4 mm

showed a non -significant increase in pocket depth and attachment

level. 4 –6 mm pocke ts showed a significant decrease in pocket depth

and a non -significant gain in attachment post -therapy, while 6 mm

pockets showed a significant decrease in pocket depth and attachment

level measurements post -therapy. Clinical improvement post -SRP was

accompanied by a modest change in the subgingival microbiota,

15

suggesting potential targets for therapy and indicating that radical

alterations in the subgingival microbiota may not be necessary or

desirable in many patients.

Cobb CM 2002 2 5

Analysed the Egyptian hieroglyphics and medical Papyri to evaluate the clinical significance of non -surgical therapy: the collective evidence from numerous clinical trials reveals a cons istency of clinical response in the treatment of chronic periodontitis by SRP remains the “gold standard” thus controlling sub -gingival bacterial populations, removal of calculus, root smoothness and also improvement in clinical parameters like probing dep th, attachment levels, bleeding on probing and gingival inflammation. It was also added that SRP acts as a significant component on a relatively new paradigm of complete mouth disinfection in a compressed time frame.

Hue AC et al., 1961 2 6

16

Ishikawa I et al., 1970 2 7

Investigated the correlation between Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) level of activity in Gingival exudate and various clinical parameters, collected from incisor and canine region in 21 patients aged 18 -65 years with extensive gingival inflammation an d periodontitis. Clinical parameters included PMA index, Gingival index, periodontal pocket. Radiographic evaluation for bone loss by Marshall -Day and Shourie (1949). ALP was measured in 10μl of fluid and 20μl of serum by colorimetric technique. The result s of analysis showed positive correlation between ALP levels in GCF with that of alveolar bone loss in patients with periodontitis along with increased clinical parameters concluded stating the prime relevance of ALP levels for diagnosing periodontal disea se.

Miglani DC et al., 1974 2 8

17

Chapple IL et al., 1994 2 9

Investigated GCF ALP levels in the health and in the presence of gingivitis in 30 patients. In gingival health, there was a site specific pattern of ALP concentration with higher enzyme concentrations around the upper and lower anterior teeth. Furthermore, clinically normal sites that had been subjected to different levels of plaque control produced significantly different ALP levels, which indicates that the biochemical components of GCF may be used to measure the sub-clinical inflammatory status. The ratio of GCF to serum ALP varied from 6:1 to 11:1 suggesting that the major source of enzymes is through local production and analysis of plaque within the s tudy group demonstrated very low levels of ALP, indicating that the enzyme is likely to be largely derived from the periodontal tissues.

Chapple IL C et al., 1999 3

18

Gibert P et al., 2003 1 5

The author studied the activity of ALP isoenzyme among the other isoforms in the serum of 83 patien ts (59 with periodontal disease - chronic periodontitis, 24 as control group) by determining the total serum ALP activity and percentage of the different isoforms (bone, kidney and intestinal type) by Ektachem analyser and Gel agarose electrophoresis respec tively. The comparison between the two groups resulted a relationship between loss of attachment in periodontal disease and a drop in bone ALP activity in serum. Moreover, these results suggested a gender based difference as well, with lower activity more frequent in women than in men.

DaltabanÖ et al., 2006 3 0

19

and that a patient’s estrogen status may possibly influence local ALP levels in GCF.

Todorovic T et al., 2006 7

The authors examined the activity of CK, LDH, AST, ALT, GGT, ALP and ACP in saliva from 30 patients with periodontal disease before and after phase I periodontal treatment and from 20 healthy individuals. Periodontal disease was determined based on clinical parameters (Gingival Index, bleedi ng on probing and probing depth). The obtained results shown statistically significant increase of activity of CK, LDH, AST, ALT, GGT,ALP and ACP in saliva in patients with periodontal disease in relation to control group along with a positive correlation between activity of salivary enzymes and value of Gingival index and there was significant decrease in activity of all salivary enzymes after treatment. Hence it was assumed that the activity of these enzymes in saliva, as biochemical marker for periodonta l tissue damage, may be useful in diagnosis, prognosis and evaluation of therapy effects in periodontal disease.

Desai S et al., 2008 3 1

20

was concluded that the ALP levels in saliva was increased with the increase in the CPITN score. Group C0 had the least while group C4 had the highest ALP levels. Hence, concluded that the salivary ALP levels may be useful as a potential bone turn over marker to establish the diagnosis and prognosis of periodontal disease.

Perinetti G et al., 2008 3 2

The study aimed to improve the understanding of how the healing of chronic periodontitis following scaling and root planing (SRP) affects GCF ALP activity after 15 days and 60 days in 16 sytemically healthy patients with moderate to advanced generalised chronic periodontitis. 92 pockets were randomized at the split mouth level with half receiving SRP and other half left untreated. Plaque index, probing depth, CAL, BOP were recorded at baseline, after 15 days and 60 days. GCF was collected from each pocket included in the study at the 3 time points for ALP estimation. Results shown a large and significant decrease in GCF ALP activity in 15 days after SRP with improvement in clinical parameters after 60 days, an increase in GCF ALP back to baseline levels was recorded along with further improvements in clinical parameters. Hence, it was concluded that GCF ALP reflects the short term pe riodontal healing/ recurrent inflammation phases in chronic periodontitis patients.

Üsal B et al., 2008 3 3

21

with hyperg onadotropic hypogonadism (HH) in 41 patients divided into 4 groups. 9 with HH and periodontitis, 11 with HH and gingivitis, 9 with systemically healthy and periodontitis, 12 with systemically healthy and periodontally healthy individuals. Clinical evaluati on included Plaque index, gingival index, probing depth and CAL. The ALP IN GCF were measured by ELISA. The concentrations and total amounts of ALP in GCF were significantly higher in both periodontitis group compared to healthy and gingivitis groups. The serum ALP levels were significantly higher in the HH and periodontitis group when compared to the other groups. Thus it was concluded that HH could be implicated as a contributing factor to the progress of periodontal disease with increased ALP levels.

Malhotra R et al., 2010 3 4

22

periodontal disease marker as it can distinguish between healthy and inflamed sites.

Perozini C et al., 2010 3 5

Evaluated the levels of Interleukin -1β (IL-1β) and ALP in GCF and correlate these measurements with clinical characteristics of 36 individuals subdivided as 3 group healthy individuals and patients with gingivitis and periodontitis. GCF samples were obtained from 2 sites for each patient and were measured using Periotron 8000 whereas IL -1β levels were evaluated using the ELISA and ALP was measure d by the kinetic method. The amount of ALP differed significantly among the 3 groups. The amount of IL -1β in periodontitis group was significantly higher than in the other groups, but no significant difference was found between the control group and the gi ngivitis group. There was no evidence for correlation between IL -1β and ALP levels thus concluding that monitoring immune markers may give additional information on healthy or diseased sites.

Jaiswal G et al., 2011 3 6

23

mean serum ALP level in the test group was higher than the control group and the difference was statistically significant. The older age group liver cirrhosis patients exhibited higher values for bone loss, CAL and serum ALP levels. Hence, it was concluded that there is a strong positive correlation between periodontal breakdown an d serum ALP level in liver cirrhosis patients.

Dabra S et al., 20123 7

24

Kunjappu JJ et al., 2012 3 8

The study compares the levels of GCF ALP in pa tients with chronic periodontitis before and after scaling and root planing in 20 patients with localised periodontitis. The GCF was collected from the affected site prior to scaling and root planing for ALP estimation. The probing depth and plaque index a t the sites were also measured at baseline, 7, 30 and 60 days for re -assessment. The obtained results showed a sustained, statistically significant decrease after treatment and thee was a positive correlation with probing depth but not with plaque index, m easured at each interval. It was thus concluded that the assessment of level of periodontal disease and effect of mechanical plaque control on progression and regression of the disease can be evaluated precisely by the corresponding GCF ALP levels. Hence, ALP level is not only a biomarker for pathology, but also an indicator of prognosis of periodontitis.

Trivedi D et al., 2012 3 9

25

derived from degenerating gingival tissue or systemic circulation due to infectious change in membrane permeability, thus increased levels of intracellular enzymes LDH, AST, ALP in unstimulated saliva can be used for the diagnostic tool in screening of periodontal disease.

Sanikop S et al ., 2012 4 0

The study aimed to determine the presence and levels of ALP activity in GCF in periodontal health, gingivitis and chronic periodontitis from 45 sites, which were equally divided into 3 groups. Various clinical parameters like Gingival index, pl aque index, probing pocket depth, CAL were also evaluated and correlated with the GCF ALP levels. The results showed that the difference between the mean ALP levels between the healthy and gingivitis group was found to be non-significant and that between t he chronic periodontitis group and healthy as well as gingivitis group was found to be highly significant along with significant correlation existing between ALP levels and gingival index, probing depth as well as CAL. The findings suggests that and confir ms the relationship between ALP levels and periodontal disease, thus indicating that GCF ALP levels can be used as potential biochemical marker for detection and progression of periodontal disease.

Ramesh A et al., 2013 5

26

II of 20 post -menopausal women with chronic periodon titis. The results shown significant increase in alkaline phosphatase in post -menopausal women with chronic periodontitis. Hence it was concluded that ALP can be used as a diagnostic marker of periodontitis in post -menopausal women; however ALP cannot sole ly be responsible for periodontitis, but it can be used as an addition aid in diagnosing periodontitis.

Khongkhunthian S et al., 2014 4 1

27

Perumal CL et al., 2014 4 2

The study was carried out to compare the serum total ALP level among 31 healthy individuals and 36 chronic periodontitis patients in Tamilnadu and to evaluate the racial behaviour in the enzyme levels. Comparison of the total ALP activity between the healthy and chronic periodontitis group showed an increase in total ALP activity among chronic periodontitis. Thus, the results were simil ar to other studies, suggestive of using serum ALP measurement as a reliable assay for chronic periodontitis and there was no racial or ethnic differences.

Caúla AL et al., 2015 4 3

The study aimed to evaluate the relationship between severe chronic perio dontitis and serum creatinine and ALP levels. 100 patients were evaluated, 66 with severe chronic periodontitis and 34 periodontally healthy individuals. Blood samples were collected after an overnight fast and serum creatinine and ALP levels were determin ed. The results showed that the patients with periodontitis exhibited a lower mean creatinine level and higher mean alkaline phosphatase levels than in control group. Also there was significant correlation between the periodontal parameters and serum creat inine and ALP levels. Hence it was concluded that severe chronic periodontitis was associated to lower creatinine and higher ALP levels.

Luke R et al., 2015 4 4

28

parameters to saliva of healthy subjects, gingivitis patients and patient s with chronic periodontitis. The study included 40 male subjects of age group 21 to 50 years. Clinical parameters like OHI -S, sulcus bleeding index, probing depth, CAL and periodontal index were recorded. The results showed significant increase of activity of AST, ALT, ALP and BUN in saliva from patients with periodontal disease in relation to gingivitis and control group. There was also an increase in pe riodontal parameters with an increase in salivary enzymes. Thus it was concluded that salivary enzymes can be used as biomarker to determine periodontal tissue damage, which may be useful in diagnosis, prognosis and evaluation of post therapy effects in pe riodontal disease.

Soud P et al., 2015 4 5

29

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A clinical study was conducted at the department of periodontology, Adhiparasakthi dental college and hospital (APDC&H), Melmaruvathur . A total number of 50 subjects in the age range of 30 to 50 years were selected from the out -patient division of Periodontics, APDC&H. Ethical clearance for the study was obtained from the Institutional review board, APDC&H (Reference No:2014 -MD-BrII-SAS-05). All the subjects participated in the study were informed about the nature of the study and all the participants signed an informed consent form.

Method: Sample size:

Control Group:10 individuals (periodontally healthy individuals)

Study Group:40 pati ents (chronic generalised periodontitis)

Inclusion criteria:

Control group: Participants with at least 20 natural teeth and probing pocket depth of 2 -3mm with no attachment loss and bleeding on probing with< 20% sites.

30

Exclusion criteria:

Any systemic diseases

Smokers

Pregnancy

Has not undergone any periodontal therapy for the past 1 year.

Patients who are not maintaining their oral hygiene.

The following clinical indices and parameters were recorded:

OHI-S Index(Greene & Vermillion)

Gingival Index(Loe&Silness)

Probing pocket depth

CAL

The followi ng biochemical markers were analysed:

Salivary ALP level

Serum ALP level

Method to be followed:

31

planing should be completed within 15 days from the baseline in two subsequent visits. On 30t h day after completion of phase 1 periodontal therapy, patients are reviewed where saliva and blood samples are collected and analysed again for ALP activity.

OHI-S (Greene and Vermillion, 1964) 4 6

The Simplified Oral Hygiene Index (OHI -S) differs from the original OHI (The Oral Hygiene Index) in the number of the tooth surfaces scored (6 rather than 12), the method of selecting the surfaces to be scored, and the scores, which can be obtained. The criteria used for assigning scores to the tooth surfaces are the same as those use for the OHI (The Oral Hygiene Index).

The OHI-S, like the OHI, has two components, the Debris Index and the Calculus Index. Each of these indexes, in turn, is based on numerical determinations representing the amount of debris or calculus found on the preselected tooth surfaces.

Selection of tooth surfaces

The six surfaces examined for the OHI -S are selected from four posterior and two anterior teeth.

32

In the anterior portion of the mouth, the labial surfaces of the upper right (11) and the lower left central incisors (31) are scored. In the absence of either of this anterior teeth, the central incisor (21 or 41 respectively) on the opposite side of the midline is substituted.

Criteria for classifying debris

Scores Criteria

0 No debris or stain present

1 Soft debris covering not more than one third of the tooth surface, or presence of extrinsic stains without other debris regardless of surface area covered

2 Soft debris covering more than one third, but not more than two thirds, of the exposed tooth surface.

3 Soft debris covering more th an two thirds of the exposed tooth surface.

Criteria for classifying calculus

Scores Criteria

0 No calculus present

1 Supragingival calculus covering not more than third of the exposed tooth surface.

2 Supragingival calculus covering more than one third but not more than two thirds of the exposed tooth surface or the presence of individual flecks of subgingival calculus around the cervical portion of the tooth or both.

33

Interpretation

Individually DI -S and CI-S is scored as follows: 0.0 to 0.6 = Good oral hygiene

0.7 to 1.8 = Fair oral hygiene 1.9 to 3.0 = Poor oral hygiene

An OHI-S is scored as follows: 0.0-1.2 = Good oral hygiene 1.3 -3.0 = Fair oral hygiene 3.1 -6.0 = Poor oral hygiene

Oral Hygiene Index = Debris Index + Calculus Index

Gingival Index: 4 7

Gingival Index (GI) was introduced by Loe and Silness in 1963

GI could be used in all teeth or selected teeth and in all surfaces or selected surfaces.

The examination done by blunt probe.

34

Calculation:

GI = Total scores / No. of surfaces examined

If we want to calculate the maximum score for gingival index (4 surfaces and 6 teeth)

Interpretation: Score Criteria

0 - No inflammation.

1 - Mild inflammation, slight change in color, slight edema, no bleeding on probing.

2 - Moderate inflammation, moderate glazing, redness, bleeding on probing.

3 - Severe inflammation, marked redness and hypertrophy, ulceration, tendency to spontaneous bleeding.

GI is scored as follows: 0.1-1: Mild gingivitis 1.1- 2: Moderate gingivitis 2.1- 3: Severe gingivitis

Probing pocket depth (PD): 4 8

35

lingual, and mesiolingual. As a general rule, a probe reading that falls between two calibrated marks on the probe should be rounded upward to the next highest millimetre. Out of 6 surfaces per tooth, the highest probing depth value is taken as the probing depth of that individual tooth.

Clinical Attachment Level (CAL): 4 8

CAL is the distance from the cementoenamel junction (CEJ) to the base of the periodontal pocket. CAL measurement also involves measuring with a calibrated periodontal probe (UNC -15) around the tooth and recording the deepest point at each of six tooth surfaces from the CEJ: distof acial, facial, mesiofacial, distolingual, lingual, and mesiolingual.

Collection of saliva:

36

Collection of blood:

5ml of fasting blood samples were collected from each individuals transferred to the nearby biochemical laboratory for assay. After an hour, the supernatant serum was extracted and Total ALP levels were evaluated semi -autoanalyser (BTS 350, BIOSYS®) with the IFCC recommendati ons and the results expressed in U/L.

Non-surgical periodontal therapy:

Following the sample collections, complete ultrasonic scaling was performed to all the patients in study group. All the patients were instructed to maintain their oral hygiene with M odified Bass brushing technique and to use Chlorhexidine mouth wash twice daily. Root planing, wherever required was done after 15days from baseline within 2 subsequent visits. All the patients were recalled on 30t h day following completion of phase 1 peri odontal therapy for review and post-operative sample collection (both blood and saliva).

ALP ESTIMATION BY SPECTROMETRY: Method:

Kinetic photometric test, according to the International Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine (IFCC).

Principle:

37

Reagents:

Components and Concentrations:

R1: 2-Amino-2-methyl-1 -propanol pH 10.4 1.1 mol/L

Magnesium acetate 2 mmol/L

Zinc sulphate 0.5 mmol/L

HEDTA 2.5 mmol/L

R2: p-Nitrophenylphosphate 80 mmol/L

Storage Instructions and Reagent Stability:

The reagents are stable upto the end of the indicated month of expiry, if stored at 2 -8 °C and contamination is avoided.

Reagent Preparation: Substrate Start

The reagents are ready to use.

Sample Start

Mix 4 parts of R1 + 1 part of R2 (e.g. 20 mL R1 + 5 ml_ R2) = monoreagent

Stability:

4 weeks at 2-8 °C 5 days at 15 -25°C Specimen

Stability:

38

Sample start

Blank Sample or calibrator Sample or calibrator - 20 μL

Dlst. Water 20 μL - I Monoreagent 1000 μL 1000 μL

Mix, read absorbance after 1 min. and start stopwatch. Read absorbance again after 1, 2 and 3 min.

Performance characteristics Measuring range

On automated systems the test is suitable for the determination of AP activities up to 1400 U/L.

In case of a manual procedure, the test is suitable for AP activitieswhich correspond to a maximum of AA/min of 0.25.

If such values are exceeded the samples should be diluted 1+9with NaCl solution (9 g/L) and results multiplied by 10.

Specificity/Interferences:

No interference was observed by ascorbic acid up to 30 mg/dL, conjugated bilirubin up to 60 mg/dL, unconjugated bilirubin to 25 mg/dL, hemoglobin up to 100 mg/dL and lipemia up to 2000 mg/dL triglycerides.

Sensitivity/Limit of Detection:

39

Basic Armamentarium: 1. Mouth mirror 2. UNC 15 probe

3. Universal curettes - 2R/2L & 4R/4L 4. Gracey curettes- #1-14

5. Surgical gloves 6. Mouth masks 7. Tweezers 8. Cotton rolls

40

[image:52.595.162.437.314.497.2]Figure 1: Chronic generalised periodontitis Pre -operative 1

Figure 2: Chronic generalised periodontitis Pre -operative 2

[image:52.595.161.437.552.735.2]41

[image:53.595.163.433.308.489.2]Figure 4: Probing depth >5mm at baseline

Figure 5: Following non -surgical therapy 1

[image:53.595.163.433.545.725.2]42

[image:54.595.161.433.308.489.2]Figure 7: Following non -surgical therapy 3

Figure 8: Probing depth after phase 1 periodontal therapy

[image:54.595.162.434.545.723.2]43

[image:55.595.163.433.307.490.2]Figure 10: Collection of saliva

Figure 11: Collected blood sample

[image:55.595.162.434.545.724.2]44

[image:56.595.161.435.306.490.2]Figure 13: Centrifuge machine

Figure 14: Centrifuged saliva and serum samples

[image:56.595.162.435.546.725.2]45

Figure 16: Semi auto analyser for ALP estimation

[image:57.595.161.436.324.504.2]46

RESULTS

This study was conducted to evaluate the levels of serum and salivary ALP in patients with generalized chronic periodontitis before and after non -surgical periodontal therapy and to compare the outcomes with healthy subjects. A total of 40 chronic generalised periodontitis (study group) and 10 periodontally healthy subjects (control group) were selected from the out -patient sec tion of department of periodontics, Adhiparasakthi dental college and hospital. All clinical parameters were measured at baseline with saliva and blood samples collected on the same day and then 30 days after phase 1 periodontal therapy. Saliva and blood s amples were sent for spectrometric analysis for ALP estimation. The obtained results were tabulated and the data collected were subject to statistical analysis.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS:

The collected data was subjected to statistical analysis through SPSS ( Statistical Package for Social Science).

The Paired t test was used to assess the baseline and post -operative values of clinical parameters such as OHI -S, Gingival index, probing pocket depth, Clinical Attachment Level and biomarker parameters such as s erum ALP and salivary ALP levels.

47

Gingival index, probing depth, CAL and biomarker parameters such as serum ALP and salivary AL P levels.

48

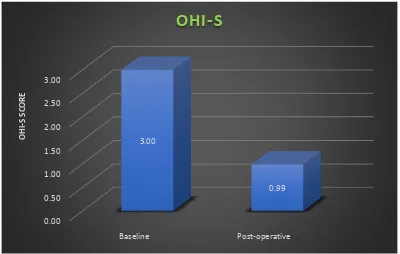

Table 1: Mean change in OHI S score from baseline to post -operative in study group

Significant at the 1% level. **Statistically highly significant difference

The mean OHI -S score of study group at baseline was 3.00 ± .04 and post -operative score was found to be 99 ± .02. On comparing baseline score with post -operative score, the reduction in the OHI - S score was found to be statistically significant with P -value .000**

Chart 1: Mean change in OHI S score from baseline to post -operative in study group

0.00 0.50 1.00 1.50 2.00 2.50 3.00

Baseline Post-operative

3.00

0.99

OHI

-S

SCO

R

E

OHI-S

BaselinePost -operative

T value P-value

49

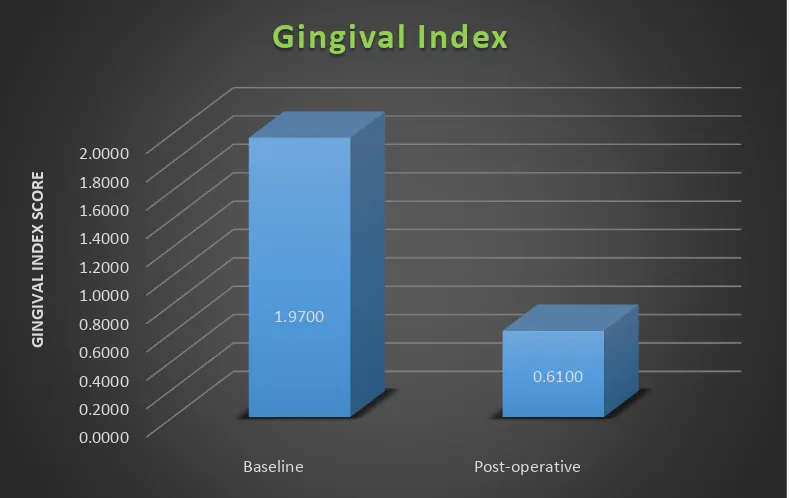

Table 2: Mean change in GI score from baseline to post-operative in study group

Significant at the 1% level. **Statisticall y highly significant difference

The mean GI score at baseline in study group was 1.97 ± .05 and post-operative score was found to be .61 ± .01. On comparing baseline score with post -operative score, the reduction in the GI score was found to be statistically significant with P -value .000**

Chart 2: Mean change in GI score from baseline to post-operative in study group

0.0000 0.2000 0.4000 0.6000 0.8000 1.0000 1.2000 1.4000 1.6000 1.8000 2.0000 Baseline Post-operative 1.9700 0.6100 G ING IVAL IND EX SCO R E

Gingival Index

Baseline Post -operativeT value P-value

50

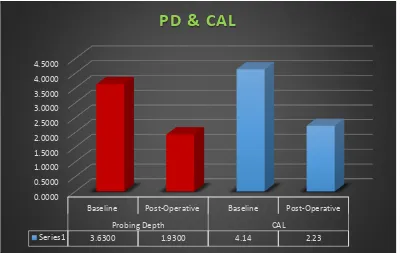

Table 3: Mean change in probing depth & CAL from baseline to post-operative in study group

Baseline Post -operative T value P-value

PD 3.63 ± .17mm 1.93 ± .09mm 17.88 .000** CAL 4.14 ± .19mm 2.23 ± .09mm 18.58 .000**

Significant at the 1% level. **Statistically highly significant difference

The mean probing depth & CAL in study group at baseline was 3.63 ± .17mm and 4.14 ± .19mm respectively and post -operatively 1.93 ± .09mm and 2.23 ± .09mm. On comparing baseline values with post-operative values, the reduction in the probing depth and gain in CAL post operatively was found to be statistically significant with P -value .000**.

Chart 3: Mean change in probing depth & CAL from baseline to post-operative in study group

0.0000 0.5000 1.0000 1.5000 2.0000 2.5000 3.0000 3.5000 4.0000 4.5000

Baseline Post-Operative Baseline Post-Operative

Probing Depth CAL

Series1 3.6300 1.9300 4.14 2.23

51

Table 4: Comparison of mean baseline salivary & serum ALP levels between control group and study group

Significant at the 1% level. **Statistically highly significant difference

On Comparing the mean baseline values of salivary andserum ALP levels of control group with baseline values of study group, the difference in salivary and serum ALP levels between control group (23.00 ± 6.67 and 72.70 ± 2.19) and study group (79.55 ± 6.40 and 97.62 ± 4.17) was found to be statistically significan t with P -value of .000** and .009** for saliva and serum respectively.

Control group Study group F value P-value

Saliva ALP 23.00 ± 6.67 79.55 ± 6.40 13.36 .000**

52

Table 5: Comparison of mean baseline salivary & serum ALP values with post -operative ALP values of study group

Significant at the 1% level. **Statistically highly significant difference

On Comparing the mean baseline salivary and serum ALP values with post -operative values in study group, the difference in salivary and serum ALP levels from baseline (79.55 ± 6.40 and 97.62 ± 4.17) to post-operative (49.47 ± 5.11 and 85.40 ± 4.10) was found to be statistically significant with P -value of .000** and .009** for saliva and serum respecti vely.

Baseline

Post -operative

F value

P-value

Saliva ALP 79.55 ± 6.40 49.47 ± 5.11 13.36 .000**

53

Table 6: Comparison of mean baseline salivary & serum ALP values of control group with post -operative ALP values of study group

Significant at the 1% level. **Statisticall y highly significant difference

On Comparing the mean baseline salivary and serum ALP values of control group with post -operative values of study group, the difference between the ALP levels in baseline of control group (23.00 ± 6.67 and 72.70 ± 2.19) to post -operative of study group (49.47 ± 5.11 and 85.40 ± 4.10) was found to be statistically significant with P -value of .000** and .009** for saliva and serum respectively.

Control group

Study group Post -operative

F value

P-value

Saliva ALP 23.00 ± 6.67 49.47 ± 5.11 13.36 .000**

54

Chart 4: Comparison of mean salivary ALP levels in control group with baseline and post -operative ALP levels of study group

Chart 5: Comparison of mean serum ALP values in control group with baseline and post -operative ALP levels of study group

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80

Control group Study group (baseline) Study group

(post-operative) 23

79.55

49.47

Salivary ALP levels

0.00 10.00 20.00 30.00 40.00 50.00 60.00 70.00 80.00 90.00 100.00

Control group Study group (baseline) Study group

(post-operative) 72.7

97.62

85.4

55

DISCUSSION

A comparative clinical study was conducted in department of Periodontology, APDCH, Melmaruvathur, Tamilnadu . The study population consists of 50 participants of which, 40 patients with chronic generalised periodontitis (Study group) and 10 periodontally healthy individuals (Control group ) were included in the study to whom the study design was explained and inf ormed consent was obtained from all the patients included in the study. Clinical indices including OHI-S, Gingival Index and clinical parameters including Probing depth, CAL were measured at baseline and following phase 1 periodontal for the study group. N o clinical parameters were evaluated for the control group, since the control group exhibited <20% of sites bleeding on probingand probing pocket depth of 2 -3mm and no attachment loss, along with good oral hygiene maintenance.

Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) l evels in serum and saliva were evaluated by collecting the blood and saliva samples from periodontally healthy individuals once and at baseline and then following phase 1 periodontal therapy in patients with chronic generalised periodontitis.

56

Therefore, better understanding and thorough knowledge of the biomarkers of health and disease leads to enhanced execution of appropriate and personalized preventive and therapeutic strategies to maintain finest health of an individual.

Periodontal pathogenic processes can be generally divided into three phases: inflammation; connective tissue degradation; and bone turnover. During each phase of the disease, specific host -derived biomarkers have been identified and therefore provide a general sense of stage of pathologic pr ocess the patient is currently undergoing.

Among several biomarkers of periodontal disease activity, alkaline phosphatase, being a phenotype marker of bone turnover rate has been found to be elevated in a variety of bone disorders with the highest elevati ons occur in Paget’s disease (osteitisdeformans). Other bone disorders including osteomalacia, rickets, hyperparathyroidism, and osteogenic sarcoma have also shown elevated levels of ALP. In addition, increased levels are also seen in the case of healing b one fractures and during periods of physiologic bone growth.

57

sampling from GCF is technique sensitive and takes longer time comparatively with the sample collection time for saliva.

Saliva, rich in serum albumin and in antimicrobial and immuno -modulary proteins, subsidise the lubrication of oral cavity, buffering of the tooth surface thus maintaining the int egrity of the oral cavity. Saliva also contains non -salivary elements, such as gingival crevicular fluid, desquamated cells, nasopharyngeal discharge, extraneous debris, and bacteria and bacterial by -products. 5 1

Numerous advantages lies in choosing saliva as a diagnostic tool which includes its readily available nature, it can be collected in a comfortable manner unlike blood collection by venepuncture and the associated fear of the needle, whereas saliva can be c ollection in a non -invasive manner, which makes patient compliance a reliable factor.

Various studies in the past few years have revealed the potential to identify and measure numerous biomarkers in saliva for the diagnosis of periodontal diseases and mon itoring its progression and health.

58

disease with a positive correlation with gingival index, when com pared with periodontally healthy individuals. Further study by Desai S et al., in 2008 3 1 evaluated ALP levels in unstimulated saliva of 120 patients with chronic periodontitis which were correlated with CPITN index. The study results showed that the ALP l evels in saliva was increased with the increase in the CPITN score.

Dabra S et al., in 2012 3 7 evaluated the salivary levels of ALP activity in patients with periodontal disease, before and after periodontal treatment resulted that there was significantly increased activity of ALP in saliva from patients with periodontal disease and also a significant reduction in the enzyme levels after conventional periodontal therapy.

59

patients with chronic periodontitis and the results showed significantly increased activity of ALP along with the other enzymes in saliva from patients with periodontal disease than that of gingivitis and control group.

All the studies conducted so far has aimed to rationalise the use of ALP as a biomarker in diagnosing the disease activity of periodontitis. The studies also have established the use of either saliva or serum or even GCF solely in evaluating the ALP levels in patients with chronic periodontitis and even comparison of the same with periodontally healthy individuals. But none of the studies have compared the serum and salivary ALP levels in chronic periodontitis patients and periodontally healthy individuals of same age group to validate the fact that saliva could be used over serum and GCF to assess the disease activity in patients with chronic periodontitis and also its significance of increased activity with periodontally healthy individuals.

60

The results indicated that there was a significant reduction in the mean OHI-S scores in the chronic periodontitis group from baseline to 30 days from 3.00 ± .04 to .99 ± .02 post-operatively. This implies the good oral hygiene maintenance of the patient following periodontal phase 1 therapy, which is of utmost importance factor in the p rognosis of the treatment outcomes.

There is a significant reduction in the mean Gingival Index scores from baseline to 30 days from 1.97 ± .05 to .61 ± .01 following periodontal phase 1 therapy which is in accordance with the study conducted by Todorovic T et al., in 2006. 7 This may be due to the elimination of local etiological factors which harbours numerous pathogenic strains

There is a significant reduction in mean probing pocket depth readings from baseline to 30 days from 3.63 ± .17mm to 1.93 ± .09mm following periodontal phase 1 therapy. This can be attributed to the scaling and root planing, as it leads to resolution of inflammatory response and cessation of periodontal disease progression, thereby resulting in reduction of probing depth which is in accordance with the studies conducted by Daltaban Ö et al., 2006 3 0 and Todorovic et al., 2006. 7

61

of Scaling and root planing as it leads to resolution of inflammatory response and cessation of periodonta l disease progression and hence resulting in a relative gain of clinical attachment level. Scaling and root planing also helps in eliminating the bacteria present at the site, thus reducing the colonization of periodontal pathogens resulting in making a fa vourable environment for oral hygiene maintenance by the patient.

Following phase 1 periodontal therapy, the patients with chronic periodontitis has shown a proportionate reduction in the ALP mean values in both saliva (79.55 ± 6.40 to 49.47 ± 5.11) and serum (97.62 ± 4.17 to 85.40 ± 4.10) respectively. The reduction in the values may be due to thorough scaling and root planing with proper oral hygiene maintenance of the patients. The results of this study is in accordance with the results obtained from t he study conducted by Dabra S et al., in 2011 3 7 for salivary ALP levels at baseline and post -operatively, which was (29.43±13.10 to 44.55±19.14).