Precis.

The study is primarily concerned with measuring and explaining the extent of industrialization in one country, the Philippines. The work is organized in two parts covering the two periods of industrial growth before and after independence of that country in 1946.

In the first period, industrialization made its beginnings in the export sector where the extension of trade preferences in the U.S. market led to a rapid expansion in output of these industries and radical changes in their technology of production. The latter could be summed up as a change from handicraft to factory system of production. Both local and foreign sources of capital played their part in this transformation and growth and on the available evidence it appears that foreign investment and entrepreneurship took the lead to be followed shortly after by local efforts when the profitability of this investment had been demon strated.

Industrialization for the home market during this period vas much less impressive, being confined to one or two factories in several indust ries which for a variety of reasons were able to withstand the competition of duty free imports from the U.S. These factors are analysed in Chapter 4. Contrary to general belief however, these ’few' factories constituted the major part of domestic manufacturing, and although handicrafts and

I

household manufacturing continued to grow, they remained relatively small in terms of aggregate output and capital investment. In terms of employment however, they dominated this sector.

Congress promising full independence to the Philippines in 19^6. From 1931* on, Philippine relations with the U.S. turned around the single issue of the terms on which trade between these two countries would be conducted during the transition period. For it was then assumed that after inde

pendence, Philippine exports would enter the U.S. market on much less favour able terms than they had been accustomed to, and the economy had to be

adjusted accordingly. It was out of this necessity that deliberate

efforts to industrialize arose, and from the outset, this was to take the form of developing industries for the home market by replacing imports of manufactures.

Little progress had been made in pursuing this objective when World War II spread to the Philippines and all programmes of industrialization were abandoned* When efforts were resumed again after the War it was in a new and in many ways a more favourable setting. The prewar policy of direct government participation in financing and running industrial

enterprises was abandoned in favour of reliance on various incentives and sanctions to persuade tne private sector to undertake the task of industrial development. The most effective of these were the protection and subsidies provided by the foreign exchange and tax exemption policies, supplemented by selective credit controls and deficit financing on a modest scale.

Under these stimuli, the rate of growth of manufacturing accelerated sharply over itw prewar pace. From 1950 to I960, industrial output

replacement, though in several industries, the growth of aggregate demand was the dominant source of growth.

Maurice Haddad.

Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Australian National University,

Canberra.

The greater part of this study was undertaken while I was a re

search scholar in the Department of Economics in the Research School of

Pacific Studies3 at the Australian Rational University. I wish to thank

the Commonwealth Government for financial assistance and the Australian

Rational University for the use of research facilities.

I am also indebted to Mr. David Bensusan-Butt and Dr. Max Corden

for their supervision at various stages in the preparation of this thesis;

to Dr. Helen Hughes and other members of the Department of Economics for

their valuable criticisms.

The bulk of the data for this study was collected during an eight

months visit to the Philippines in 1963. These months have been invaluable

to me in understanding the Philippine milieu and I wish therefore to thank

the Philippine Government and the staff of the Bureau of Census and Stat

istics 3 the Rational Economic Council3 the Department of Agriculture and

Ratural Resources3 and the Research Department of the Central Bank for

information generously supplied. Thanks are due also to the University of

the Philippines3 to Dr. Amado Castro and the staff of the Institute of

Economic Development and Research and of the College of Business Administ

ration.

Finally3 I should like to thank Mrs. Helen West for typing and

printing the text.

CONTENTS

Page

Acknowledgements

PART I.

III

Chapter I

Introduction1

PART 1 1 .

Chapter 2

The Development of the PhilippineEconomy to World War II.

14

Chapter 3

Manufacturing for Export: 1900 - 194034

Chapter 4

Industrialization for the Home Market1900 - 1940.

67

PART III.

Chapter 5

The Postwar Setting87

Chapter 6

Objectives3 Plans and Policies103

Chapter 7

The Growth of Selected Industries144

Chapter 8

The Extent and Pattern of PhilippineIndustrialization

179

Chapter 9

Conclusions214

Appendices

23t

Bib!iography

27®5

Introductory.

1

This study is a description and an analysis of the process of industrialization in the Philippines. It is directed primarily to students of Philippine affairs but it may have interest for others as an example of development policy in a newly independent country.

Much has been written on the Philippine economy especially in the postwar period. Most of it, however, has been in the form of commentry on current policies and short term changes in the economy and it therefore lacked much of the advantages of a "long view"where- by policies and events may be seen as part of a pattern rather than

ad hoc measures and disturbances. In particular, no detailed study of the Philippine effort to industrialize exists and this study attempts to fill this gap.

Although occasional references will be made to earlier and later years, the study is restricted to the period 1910 - 1960. The end of the period was determined partly by the availability of data. The census of population was taken in 1960 and the latest published survey of manufactures is that of 1960. But there is also a more telling reason why this is a convenient date. From 1949 until that year businesses operated under what has been collectively termed

2.

devaluation in that year. The fruits of these new policies are not yet fully assessable at least not until further information is pub lished concerning changes in the major aggregates in the economy.

Initially, the intention was to study the period 1946 - 60 covering the early postwar reconstruction and the decade of controls which followed. But in the course of research it was found that a

considerable segment of Philippine industry had already been developed in the prewar years. It was also found that much of the postwar

industrial growth and policies could not be explained without frequent references to events of the prewar years. This was in fact no more than the realization that a thorough analysis of industrialization must begin at the beginning of the process when there were no indust rialization in the sense defined below. The year 1910 then became a logical point to begin our account of industrial growth, for it marked the establishment of the first mechanised factories in the Philippines.

1 1

.

Industrialization has never been defined in the sense that a demand curve has been defined. It has consequently acquired many and indefinite meanings largely because it describes a process of change involving what seem to be rather complex relationships which have so far proved elusive.

On scanning the literature in this subject, one finds that 1

the meanings of the term seem to cluster around two 'poles'. At one pole industrialization means the growth of the manufacturing sector

in an economy where manufacturing means little more than the production of goods that are not agriculture, not extractive, not services and growth can be measured relatively or absolutely in terms of output produced or the quantity of labour and capital employed. At the other pole, industrialization connotes large scale enterprises and especially

1 when scale is measured in terms of the amount of capital employed: one usually means large mechanised factories as opposed to small handi craft establishments employing only a few workers and with very little plant and equipment.

The two meanings normally run together. A highly industrial ized country will have a large manufacturing sector (however one measures ’large’) and many large enterprises (however one defines 'many and

large).

Perhaps for some purposes exact numerical measures of

’industrialization' or precise definitions of the term are worth adopt ing. This might be necessary, for example, in comparative studies of countries for which there are full statistical apparatuses available. But this is a study of one country and one that is still on any reckoning low in any scale of industrialization and one for which there are singularly scrappy and shifting statistics. We shall use the term therefore in a broad and sometimes vague sense as describing the composition and growth (absolute and relative) of the

A ing sector as that term is used in Philippine sources. It is impre cise, but it does have the advantage of enabling us to present inform ation which usually cannot be fitted into a strict statistical series but which nevertheless helps us to present a more recognizable picture of the extent of Philippine industrialization,

111

.

The work is arranged into two parts corresponding to the periods of industrial growth before and after World War II. In each there is an opening section - Chapter 2 in Part I and Chapters 5 and 6 in Part II - devoted to sketching in general terms the historical- policy setting of each period. This is followed by two chapters in Part I (3, A) and one in Part II (7) on the development of manufactur ing industries for the export and home markets. Chapters 3 and A are an elaboration of Chapter 2. Both cover the same period but the former delve into more details and take the major export and home industries of the prewar period one by one describing their growth and mechanisation. Chapter 7 analyses the growth of both types of industries in the postwar period.

As a f u r t h e r p r e l i m i n a r y b e f o r e we b e g i n our n a r r a t i v e , t h i s

c h a p t e r c o n c l u d e s w i t h a few s h o r t n o t e s on some m a j o r n o n - e c o n o m i c

a s p e c t s o f t h e P h i l i p p i n e s . T h i s i s a s t u d y i n t h e e c o n o m i c s o f one

c o u n t r y and a p a r t o n l y o f t h e m. But we s h a l l i n t h e c o u r s e o f t h e

s t u d y r e p e a t e d l y make r e f e r e n c e t o some a s p e c t s o f t h e P h i l i p p i n e

p o p u l a t i o n , t h e i r s o c i a l a nd p o l i t i c a l h i s t o r y and t h e i r i n s t i t u t i o n a l

s t r u c t u r e w h i c h was a l s o b e i n g d e v e l o p e d d u r i n g t h i s p e r i o d . Hence

i t i s c o n v e n i e n t t o l a y o u t t h e s e r e m a r k s a t t h e o u t s e t , w i t h the

w a r n i n g t h a t t h e y a r e t h e r e m a r k s o f an a m a t e u r i n H i s t o r y and

S o c i o l o g y .

D u r i n g t h e p e r i o d u n d e r s t u d y , t h e g r o w t h o f p o p u l a t i o n

was n e v e r a ' p r o b l e m ' in t h e s e n s e i n w h i c h i t i s g e n e r a l l y r e g a r d e d

t o d a y i n o t h e r u n d e r d e v e l o p e d c o u n t r i e s . The r a t e o f g r o w t h was

l o w e r and t h e s i z e o f t h e t o t a l p o p u l a t i o n much s m a l l e r when modern

i n d u s t r y f i r s t made i t s a p p e a r a n c e i n t h e P h i l i p p i n e s . The f i r s t 1 Ce ns us t a k e n i n 1903 e s t i m a t e d t h e p o p u l a t i o n a t 7*6 m i l l i o n . By

1939 t h e number i n c r e a s e d t o 16*0 m i l l i o n and d e s p i t e t h e l a r g e

l o s s e s d u r i n g t h e s e c o n d Worl d War, t h e 1948 C ens us e s t i m a t e d t h e

P h i l i p p i n e p o p u l a t i o n a t 19*2 m i l l i o n . I n t h e s u b s e q u e n t 12 y e a r s ,

t h e r a t e o f g r o w t h a c c e l e r a t e d , i n c r e a s i n g f ro m 1*9 p e r c e n t t o 3*2

p e r c e n t t o b r i n g t h e t o t a l p o p u l a t i o n t o t h e f i g u r e o f 27 m i l l i o n

IV.

6. in I960.1

These figures rank the Philippines among the fastest growing populations. Other countries e.g. the Argentine, Brazil, Canada and Malaya, have shown similar rates of increase during the same period, but these countries owe a large share of their growth to immigration

2

which has been of minor importance in the Philippines. Growth rates of this order of magnetude must make population growth a dynamic force in the economy. How this affected the pace of industrialization will become more evident in the course of the subsequent chapters.

The Philippines is well endowed with natural resources and this heritage made possible such rapid increase in the size of the population without producing the strain on resources that has been the misfortune of the more conspicuous cases of underdeveloped countries. With 1,100 islands and a land area of about 115,000 square miles the Philippine population so far has had a comfortable spread. The climate is tropically mild and allows cultivation throughout the whole year. An estimated 12*5 million hectares

(42 per cent of total area) is still forest land. Of the remainder, 37*3 per cent is agricultural and pasture. About 3 million hectares of arable land remain untilled and most of it is in the sparsely populated island of Mindenao in the south.

1. See U.N. POPULATION GROWTH AND MANPOWER IN THE PHILIPPINES N.Y. I960, pp 1 - 4.

2. This is largely due to restrictive immigration laws intro duced by the American Administration mainly ggainst the Chinese. After independence, the law was retained by the Philippine Government.

The extension of cultivation seems to have kept pace with the growth of population, but much of it has been devoted to the production of export crops with the consequence that the Philippines depends upon imports for a significant part of its food supply, especially of basic • products like rice and fish.

The country is also rich in minerals. The full extent of its resources is not yet known (only one quarter of its total area has been surveyed) but mineral products, especially gold, copper, iron, chromite, manganese and mercury have been among the major exports of the country

over the last four decades. The scarcity of mineral fuel however, has been conspicuous. A small quantity of coal has been found and used in the manufacture of cement and despite extensive explorations, no commercial quantities of petroleum have been discovered. To date, the annual rate of extraction has been around 1*0 per cent of known mineral reserves and it is estimated that some of the richest deposits are still untouched. The Suriago area in the south, for example, contains 82 per

cent of the country's iron ore deposits but as yet, mining on a commercial scale has not been attempted.

The development of agricultural and mineral resources forms a large part of the economic history of the Philippines and it is a part which will be largely omitted in this study except perhaps where this development bears directly on the progress of industrialization.

Until independence in 1946, the Philippines had been a colony for almost four centuries, first under Spain and then the United States. The influence of this status on the development of the economy was

8

.something needs to be said (by way of introduction) of the indirect influence of western culture during this long period on the social and political environment in which industrialization took place. For in this influence may lie the explanation to many of the peculiarities of Philippine economic development.

Spanish rule lasted from 1565 to 1898 and for most of this period until that country became independent, the Philippine colony was administered through Mexico. Many of the experiments tried out in Mexico were repeated in the Philippines but with some important amendments particularly with regard to the treatment of the local population, the distribution of land grants and the laws regarding slavery and plantation workers.

The uniformity of the civil and religious administration of the islands had by the end of the period submerged much of the cultural diversity and isolation which separated the various tribes in the

regions. This unifying influence was particularly felt by the native governing class, the principalesj and the educated middle class many

of whom had been educated in Madrid. Nor was there any evidence of resistance to the cultural influence of the Spanish colonizers. On the contrary, the Filipino liberals had been towards the end of the nineteenth century, demanding assimilation of the Philippines as a

1 Spanish province with representation in the Spanish Cortez.

The failure to obtain this and other reforms led in 1892 to 1. See D.G.E. HallJ A HISTORY OF SOUTH-EAST ASIA3 (2nd ed.)

the formation of the Katipunan, a secret society whose aim was to obtain independence by force. Few years later a national revolt broke out against Spain but was very soon interrupted by the Spanish-American War over Cuba which had been extended to the Philippine Colony. The defeat of Spain and the declaration of sovereignty over the islands by the United States deprived the revolutionaries of any hope of immediate independence. The Philippines was to remain a colony for another 48 y ears.

American rule in the Philippines was guided by a mixture of motives of commercial gain, defence strategy and idealism; and it seem

ed as if the United States never quite made up its mind as to whether

1

it was going to stay or leave the islands. Uncertainty of this kind was to have important consequences c. the inflow of American invest ment and the development of the economy during this period. On the one hand, the U.S. set about the task of preparing for and granting of self government almost from the outset. A legislature was elected in

1907 and seven years later a Senate, a House of Representatives and a Supreme Court were instituted. In 1934, self government over internal affairs was granted with the promise of full independence in 1946. Throughout the whole period, Filipino participation at all levels of the administration was consistently encouraged and at times appeared to be proceeding at a rate almost too rapid for efficiency especially during the Democratic term of office in the United States. On the

1. See H. P. Willis, THE ECONOMIC SITUATION IN THE PHILIPPINES, The Journal of Political Economy, Vol. Xlll, March 1905. See also T. W. Friend 11American Interests and Philippine Independence". Philippine Studies, Vol 11, No. 4 and Vol

10.

other hand, economic policy especially with regard to foreign trade, was drawing the Philippine economy into more and more dependence on the U.S. economy. In 1902, a 25 per cent tariff preference was accorded

to Philippine products; in 1909 free trade with quota restrictions on tobacco and sugar was granted and four years later, trade between the two countries was made completely free, but the Philippines tariffs with the rest of the world were set at U.S. levels.

During the latter half of the nineteenth century, Philippine exports consisted mainly of three products; tobacco, sugar and abaca, while imports were manufactures and food products. The free trade with

the U.S. accentuated this specialized pattern and increased the con centration of trade in the one market. By the 1930’s, more than 80 per cent of Philippine exports and over 70 per cent of their imports were to and from the United States.

The dependence of the Philippine economy on foreign trade and the latter upon the trade preferences in the U.S. market became the central issues in the negotiations of the transitional provisions of the Independence Act of 1934. They were also the initial reasons for the government’s commitment to an industrialization programme, first in 1935 and more vigorously in the postwar period.

The United States of course entered the field of colonial administration relatively late and its venture in the Philippines was made without previous experience. The idealism which initially prompted

provides for a republican form of government with strong presidential powers and centralisation of government in the national institutions. The 54 provinces are completely subordinated to the central govern ment in Manila. This particular feature is a carry over from the

Spanish colonial administration and is perhaps more akin to the Mexican republic than to the American federal system.

As in the United States, the initiation and implementation of economic policy lie largely in the office of the President. Congression al powers over revenue, however, have provided an important check on Presidential powers and it is through Congress that the political power of the landed aristocracy (caciques ) and of interested groups such as the "sugar bloc" has expressed itself.

The executive control over economic policy is to some extent diffused among the number of executive agencies under the office of the President. The main ones are, the Monetary Board of the Central Bank, the Cabinet, the Budget Commission and the National Economic Council. This diffusion has made the implementation of economic policies in many cases ineffective because of the conflicts between agencies in areas where they have concurrent authority as, for ex ample, in the case of the foreign exchange controls in the 1950's.

Formally, the political system in the Philippines is

democratic but in practice its democratic character is largely lost because of the concentration of power in the hands of a minority class of the caciques and the commercial and industrial elite who had

1

always been the 1principales' of Philippine society. The

1 2.

cally dominant class of peasants and the small industrial working class are largely unrepresented and their interests unexpressed through the formal political channels. Trade union organization is very weak and is found in relatively few industries (mainly the waterfront). The small middle class of professionals, shop-keepers and minor industrial ists became significant only in the postwar period.

One peculiarity of the political system is worth noting at the outset. Political parties are organized not on the basis of ideological differences nor on economic interests, but on a complex and shifting system of personality groupings representing the main factions in the elite class. Moreover,(and perhaps because of this basis of organization), party allegiance is very weak and splits and

reorganizations have been very frequent ever since the first party was formed in 1900. It may also be due to the fact that in the first

three decades of the history of political parties, Philippine politics was dominated by the single issue of independence on which no political

leader or group could afford to dissent and the struggle for independ ence was associated with the names of individual personalities rather than of particular groups or parties.

One characteristic much more noticeable than in developed Western countries has remained unchanged and unaffected by American

Partly for this and partly for economic reasons, the

government bureaucracy particularly after independence has been open to widespread nepotism and corruption. The prevalence of these practices is on such scale that one hesitates to regard them as an aberration. In a society where the responsibility of the individual to the family (and vice versa) takes precedence over his responsibility to the community at large, nepotism is inevitable and is scarcily

regarded as wrong. This is further strengthened by the underdeveloped nature of the Philippine economy: with relatively scarce employment opportunities and the concentration of economic and political power in a small minority, the system easily breeds and sustains nepotism and bureaucratic opportunism. A Filipino seeking employment or an

opportunity for material advancement has little alternative to seeking the aid of influential people especially family relatives. At the same time, the political elite have used the spoils system and the family-clan structure to win votes and this has in turn reinforced the anomalies in the system.

Yet with all this, the Philippines has emerged an independ ent orderly country with internal peace and external security, with much ability in the governing classes. It ended its long history of

14

.

C H A P T E R 2.

The Development of the Philippine Economy to World War II.

I

The development of the industrial sector was, in the Philippines as elsewhere, part and parcel of the development of the economy as a whole. Before it is described, therefore, it is proper to sketch the wider history and to such a sketch, the present chapter is devoted.

The discussions and descriptions in this chapter have been deliberately kept on a general level mainly to avoid making the work a history of the Philippine economy rather than a study of its

industrialization. We begin with a review in section II of the state of the economy around 1900 at the beginning of American Administration, and in the subsequent sections carry the story through the next forty years until World War II spread to the Philippines. Postwar develop ments are left to Chapter 5 in Part II.

II

When sovereignty over the Islands was transferred from

devoted to crops destined for export. The main products of the country were the export crops, Abaca (Manila hemp), sugar, tobacco, copra, and for domestic use, rice and corn. These together accounted for 90 per cent of the total area under cultivation.

Unlike most other colonial economies, there was in the Philippines a conspicuous absence of foreign-owned plantations. The

1918 Census Report showed that 98*2 per cent of the farms were owned by Filipinos and only the remaining 1*8 per cent by Europeans,

Americans and Asiatics. Moreover,the f .ie"S were small.Of the 1,955,276

farms only 3,433 were 100 hectares or more in size.These large units covered a total area of 967,410 hectares of which only 246,061 hectares were under cultivation (10*2 per cent of the total under cultivation). 1,545,100 hectares (or 64 per cent of the cultivated land consisted

I

of farms less than 10 hectares in size. Thus, not only was foreign ownership small, but plantation holdings were also a very small pro portion of the area under cultivation.

Before 1830, trade with Spain had very little effect on the A

Philippine economy since it was largely an entrepot trade between China and the Spanish Colony in Mexico. Subsistence activity in both agriculture and handicraft manufacturing was still the occupation of the vast majority of the population. The only significant export commodity was tobacco which had been developed as a government mon opoly since 1781. Small quantities of rice and sea foods were ex ported to China and native textiles to Mexico, to supplement the

1 6

.

silk trade.

In 1830, Philippine ports were opened to foreign shipping and non-Spanish merchants. This provided the first big stimulus to the development of foreign trade. The second came with the opening of the Suez Canal in 1867, reducing transport costs and speeding up deliveries to the European markets. With these encouragements and the help of financial loans from the merchant houses, Philippine agriculture began to develop on a commercial scale for the export market. Exports increased in value from 1*8 million pesos in 1831 to 22 million in

1865 and 36*7 million in 1895. Imports increased almost as rapidly from 1*3 million pesos in 1831 to 17*9 million in 1865 and 25*4 million in 1895.^

Symptomatic of the transformation which the economy was undergoing during the latter half of the nineteenth century, were the changes in rice and textile production - the two major subsistance activities. From being export commodities in the 1850's they had become the major import items at the turn of the century. In 1902

rice imports constituted 26*4 per cent of the total value of imports and 30 per cent of total rice consumption. In the same year imports

2 of textiles were almost 50 per cent of total value of imports. From about 1870 on, imports of textiles and rice had been increasing in parallel with the growth of exports, indicating a transfer of land

and labour from rice cultivation and handicraft weaving to the

pro-1

duction of export crops.

Accompanying the growth of export industries there was, also in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, evidence of a branching out of investment in railway construction, tramways and processing of

2

export products. Even though valuable deposits of coal, copper and iron had been discovered, mining activity was not carried out on a commercial scale, chiefly it would seem because of the lack of cheap

3 transport facilities.

Manufacturing on a factory scale was inconspicuous and re stricted mainly to the export industries. Writing in 1905, H. P. Willis noted that:

"The economic conditions in the Philippines must be

1. The Census Report 1903^ attributes the sharp increase in rice

imports in 1898 to the exceptional factors of the Spanish-American w a r 3 rinderpest destroying the corabaos (work animals)s locusts a nd cholera e p i d e m i c s. However3 it also recognizes the long term trend which had been evident since 1870... 'As the production of more p r o

fitable crops such as sugar and hemp increased., the

cultivation o f rice diminished and from becoming an

article of export it changed to one o f importation as the population and their food requirements increased'.

(Census I V p.87.) Also p.218: 'the proceeds derived from

the sale o f hemp from a given amount o f land will purchase much more rice than could be grown on the same area and as

long as this remains true the islands will undoubtedly depend to a large degree on importations o f the grain '. In 1960j despite government efforts to achieve

self-sufficiencyj rice was still being imported.

2. See T . H. Pardo de Tavera in Census 19033 Vol. IV

p. 356.

18.

considered from two standpoints - that of foreign trade and that of domestic agriculture. Manufacturing is to all practical purposes non-existent and is not likely to amount to much in the future. A few simple industries like cigar making, distilling and the pro duction of essential oils exist and will do so always; but the prosperity of the country must be dependent

chiefly upon its capacity to produce agricultural 1

products for export.

Manufacturing was in existance and quite widespread, but the bulk of it was of the kind the natives had always undertaken, small scale production in the home for use in the home or for sale in the

2

village square. There was a small handicraft sector which produced a surplus. The 1903 Census enumerated 4,334 establishments each with an annual output of PI,000 (= $500) or more. These had a total capital stock of P70*l million, a monthly average employment of 125,153 workers

2 and a total output of P48*3 million.

This period of rapid export expansion and commercialization of agriculture was also one in which the population of the Philippines

1. H. P. Willis THE ECONOMIC SITUATION IN THE PHILIPPINES Journal of Political Economya Vo'l. XIII3 N o. 23 p. 146. See also Census of the Philippine Islands 1903

,

Vol. IV3 p. 461. The Census prefaced its report with the general observation3 ’the chief source of wealth of the Philippines. . . . has been the production and exportation of agriculturalcommodities’3 ibid3 p.ll. 2. CENSUS> 1903s p. 461.

grew greatly in absolute terms, though the rate may seem almost low by some present day standards. From 3*5 million in 1854 the population

1 increased to 7 million in 1902.

The development of the Philippine economy during the nine teenth century was a simple case of "growth through trade" in which the pattern of production was determined more or less by the

principles of comparative advantage and international specialization. The Philippines was producing and exporting agricultural products with a minimum of processing and importing factory manufactures and basic food products. The growth of the economy was thus geared to the growth of foreign demand.

III.

The general pattern of specialization remained practically unchanged during the four decades of American rule and foreign trade

continued to provide the impetus it had given the Philippine economy in the nineteenth century. Tariff preferences at first and free access later gave Philippine products a price advantage over their

2

competitors in the United States market. 1. ibid, p 443.

2. Four trade periods oan be distinguished according to the extent of preferences

granted:-1902 - 9 Philippine products granted tariff preference of 25%. 1909-13 Free access to all products except r i c e s u g a r and

tobacco which were restricted by quotas.

1913-35 Completely free trade between the U.S. and the Philippines.

C o n s e q u e n t l y p r o d u c t i o n o f t h e m a j o r e x p o r t c r o p s e x p a n d e d an d new

p r o d u c t s w e r e a d d e d t o t h e l i s t . F r e e t r a d e w i t h t h e U . S . A . , h o w e v e r ,

c o n c e n t r a t e d P h i l i p p i n e e x p o r t s i n t h a t s i n g l e m a r k e t w h i l e a t t h e

same t i m e f r e e e n t r y f o r U . S . p r o d u c t s i n h i b i t e d t h e d e v e l o p m e n t o f

l o c a l i n d u s t r i a l i z a t i o n .

A g r i c u l t u r a l p r o d u c t i o n d u r i n g t h i s p e r i o d r e m a i n e d a s t h e

p r e d o m i n a n t a c t i v i t y i n t h e I s l a n d s . I n 1938, 65% o f t h e e mp loy e d

l a b o u r f o r c e and 30 p e r c e n t o f r e a l n a t i o n a l p r o d u c t w e r e i n t h e

1

a g r i c u l t u r a l s e c t o r . I f s u b s i d i a r y p r o c e s s i n g i n d u s t r i e s and

s e r v i c e s a r e i n c l u d e d , t h e s h a r e o f t h e r u r a l s e c t o r i n g r o s s n a t i o n a l

2

p r o d u c t a mount s t o 56*2 p e r c e n t .

T h e r e was a r a p i d i n c r e a s e i n t h e l a n d a r e a u n d e r c u l t i v a t i o n

d e t a i l s o f wh i c h a r e shown i n T a b l e 1.

2 0.

O

TABLE 1 - AREA UNDER CULTIVATION BY MAJOR CROPS; 1 902. 1 918, 1938.

( 1 , 0 0 0 H e c t a r e s )

R i c e Corn C o t t o n C o f f e e S u g a r Abaca Coconut Toba cco A l l

P r o d u c t s

1902 593 108 3 1 . 0 72 215 150 31 1299

1918 1058 364 2 1 . 4 147 361 400 72 2416

1938 1912 702 1 . 9 1 . 6 228 508 643 75 4510

S o u r c e s : Census 1 9 0 3 , V ol . I Ce ns us 1 9 1 8 , V o l . I l l

Ce ns us 1 9 3 8 , Summary R e p o r t .

1. S e e M. F. GOODSTEIN, ' THE PACE AND PATTERN OF PHILIPPINE

ECONOMIC GROWTH: 1938, 1 948, 1 956. D ata P a p e r No. 4 3, Cor

n e l l U n iv . P r e s s , I t h a c a , N .Y . 1963, p . 9 . S e e a l s o CENSUS OF THE PHILIPPINE ISLANDS 1938.

2. THE JOINT PHILIPPINE-AMERICAN FINANCE COMMISSION: REPORT &

RECOMMENDATIONS. M a n il a 19 4 7 , pp 1 0 3 - 4 .

T h e r e w e r e a l s o s i g n i f i c a n t c h a n g e s i n t h e r e l a t i v e s h a r e s o f t h e m a j o r

c r o p s i n t o t a l f a r m l a n d c u l t i v a t e d . T a b l e I I I g i v e s t h e p e r c e n t a g e d i s

t r i b u t i o n and shows t h e i n c r e a s e o f c o r n and c o c o n u t s b e t w e e n 1902 and

1938 m a i n l y a t t h e e x p e n s e of r i c e and Aba ca . C o c o n u t s a n d s u g a r d e

c l i n e d b e t w e e n 1918 and 1938 due t o c h a n g e s i n t h e e x p o r t m a r k e t .

T h i s r a p i d e x t e n s i o n o f a c r e a g e i s r e f l e c t e d i n t h e s t a t i s t i c s

o f e x p o r t s . From a l e v e l o f P79*9 m i l l i o n i n 1903, t h e i r t o t a l v a l u e

i n c r e a s e d t o P270*4 m i l l i o n i n 1918 and r e a c h e d a p e a k l e v e l o f P333»9

1

m i l l i o n i n 1937. Some o f t h i s i n c r e a s e was due t o p r i c e r a t h e r t h a n

q u a n t i t y e s p e c i a l l y d u r i n g t h e F i r s t World War, b u t m o s t o f i t was

a s c r i b a b l e t o i n c r e a s e s i n v ol ume f o l l o w i n g t h e e x t e n s i o n o f t r a d e

p r e f e r e n c e s t o P h i l i p p i n e p r o d u c t s i n t h e U . S . m a r k e t . T h i s i s c l e a r

l y s u g g e s t e d by t h e f o l l o w i n g f i g u r e s of a v e r a g e a n n u a l e x p o r t s d u r i n g

t h e p o o r t r a d e p e r i o d s i n w h i c h p r e f e r e n c e s w e r e i n c r e a s e d .

TABLE I I .

21 .

1902 - 1908 . . . ( 2 5 p e r c e n t t a r i f f p r e f e r e n c e ) P 6 3 , 5 0 0 , 0 0 0 "

1909 - 1913 . . . (Duty f r e e e n t r y w i t h q u o t a

r e s t r i c t i o n s ) 8 9 , 0 0 0 , 0 0 0

1914 - 1935 . . . ( C o m p l e t e l y f r e e t r a d e ) 2 3 0 , 0 0 0 , 0 0 0

1936 - 1941 . . . ( F r e e t r a d e f o r a l i m i t e d p e r i o d ) 3 1 2 , 0 0 0 , 0 0 0

D u r i n g t h i s p e r i o d , t h e c o m p o s i t i o n o f e x p o r t s b ecame a l i t t l e

more d i v e r s i f i e d t h a n i t h a d b e e n i n t h e p r e v i o u s f i f t y y e a r s ( s e e

T a b l e I I I ) . But t h e y w e r e s t i l l c o n c e n t r a t e d i n t h r e e m a j o r p r o d u c t s

1. Commonwealth o f th e P h i l i p p i n e s : REPORT OF THE INSULAR

COLLECTOR OF CUSTOMS 1 9 3 8. M a n ila 1939 p . 84.

TA B L E I I I P R I N C I P A L PH IL I P P I N E EXP O RT S -S e l e c t e d y e a r s . P e r C e n t o f To tal E xp or t s b y Va lue 22

0 0 C N N OnO C O C O ' C T O O O C O < f o c o CO b^s • • • « • • * « • . • i •

o n C Oi O OO i C OC N OO o ^ < f CN ON

i—i CN r-H 0 0

H cO v O O N O C O O C d < r \ o o

c o B' S • . i .

oo o o c o <r < - * < f r - H f o CN CM CN

r-H CO CO r- H r- H r- H ON

n o O u o O O C N C O u O r —I C O •-H CO c o CO S' ? • • • • • • . • • . • i • ON m u o H O c o H c i H c o CO CN CO r—H c N <— i t-h i— i O '

O N O r ^ ' O C N I ^ t - H C N o f < r

u O • • • • * • • • • • . i •

CO B-S u O O '—i CO o f *—i C N i—1 c O u o CN CO

ON CO CO *” H i— 1 i— 1 O '

r-H

r ^

-d) CN

CO 0 0 CN ON CO LlO C ^ CM O 0 0 u o \ D r - r-H

1 cd • • i . 1

o P S'? CO r—1 0 0 O r-H r—1 0 0 UO CN r—H CO r-H

CO <u UO CN r-H ON ----\

O 'i > r-H cd

cu cu

ON cu

CN oo O u o r - H r ^ - o r ^ ' O 00 CO O ' UO »> .

1 cd • . i . > CN

uO P 6s? O ' —i CM uo CM r -1 o uo co i CN M O

CN 1) CO CO r-H r-H CN ON CN

ON > - •

r—H cd CO Cu

o

ON rr

NT <u r-H •

1 1 Ö0 uo < i - ~cr -4 " ■vO CO p

1 cd . . . • 1 1 i • 05 • H

o P B^ O ' CO CO O ' O ' o CN d a

r-H CU H CM CM CO ON 05 •

ON > d cu

*—H cd cu o

o

uo <u uo uo e o

ON 00 <}■ 00 00 uo CJM CN o p

1 cd . . . . • . p p

uo P B^S r-H i—H CO uo p 05

a; < r co i—* cd

00 > X CJ

r-H cd d>

p . cd <3

d r-H .

00 cN <j- < t oo < r d <3

1 cd . . . . . . o

< r P S'? cN no r - CO i—i cu

uo cu CO CN r - . cd <U

00 > o 05

r-H cd

NT 00

p ON CO

05 05 cu 1 1

P P d < f o

o x i—i a e UO r-H

d a ) cd d •H 00 ON

x ) p a ) x ) 05 H r-H r—<

O Cd s cu o dJ

P Ü CxO P •H X)

Jo Ph cd ü cd cd p -i p d

P P - H P X cu cd • «

■H p a . rH 05 a , p o X 05

X d o -h cu o o u •H P cu . . <U

o p d o o Q O c d u a O CL) <u a

g cd o o cd P NOcp <3 p

g oo a cd d d g P H d

o d o ,-Q o 6 3 O O o

which together accounted for 75-80 per cent of total value of exports. In the 5 years 1930-34, sugar alone made up, on average, 53.2 per cent of the total. These were the years of the independence debate in which duty free quotas to be based on existing production capacity were being proposed. Consequently, Philippine producers expanded their production

1

in order to maximise their quota allocations.

Table III also shows some significant changes in the relative importance of the nineteenth century major export as well as the

appearance of new commodities which increased their share during this period. Abaca, tobacco and coffee declined and coconut products in creased. Abaca exports had reached a peak in its relative share in 1902 when it constituted 67.4 per cent of total exports and average of 56.3 per cent in the previous six years. Tobacco products began their sharp decline after 1910 mainly because Spain had previously been the major market and the trade preferences in the U.S. were not sufficient

to meet the increasing competition from U.S. producers.

Coconut products were insignificant until the turn of the century. Exports were in the form of copra until the outbreak of the First World War provided the great stimulus for the construction of oil mills in the Philippines. Shortage of shipping space and higher prices made oil exports more advantageous than the bulky copra. Desiccated coconuts, a new product developed mainly for the American market, displaced imports from Ceylon.

24

.

Other minor products which made their appearance during this period were, embroideries, pineapples, minerals (not shown in Table III) and lumber. The latter did not become a major export until after World War II. Sugar on the other hand remained the leading export for most

of the period though its share in total exports fluctuated considerably. All these trends are of a kind that might have been expected even without the United States conquest, at any rate had good govern ment been otherwise achieved. But American rule had one profound con

sequence: it was followed by a huge switch in the direction of trade. From being an international trader, the Philippines became highly de pendent on the U.S. market. In 1899, the first year of American

administration, the U.S. took 26 per cent of Philippine exports. This proportion increased to 42 per cent in 1909, 70 per cent in 1920 and 86 per cent in 1933. The same drastic shift appeared also on the side of imports. From 7 per cent in 1899, the share of the U.S. in

Philippine imports increased to 61 per cent in 1920 and 64 per cent in 1933.1

2

By contrast, during the Spanish regime Philippine exports were more dispersed and Spain's share amounted to only 26.7 per cent at its peak level in 1886. The share of Britain, the biggest trading

1. See The American-Philippine Trade Relations: Report of

the Technical Committee to the President of the Philippines. Washington3 1944_, p.32. See also> A. A. Castro3 The

Philippines: A case study in Economic Dependence. Harvard 1955. (Ph.D. dissertation).

partner during this period, never exceeded 45 per cent.

How much of this development of exports and their concentra tion in the U.S. market can be attributed specifically to American in vestment in the Philippines is difficult to specify. Available estimates

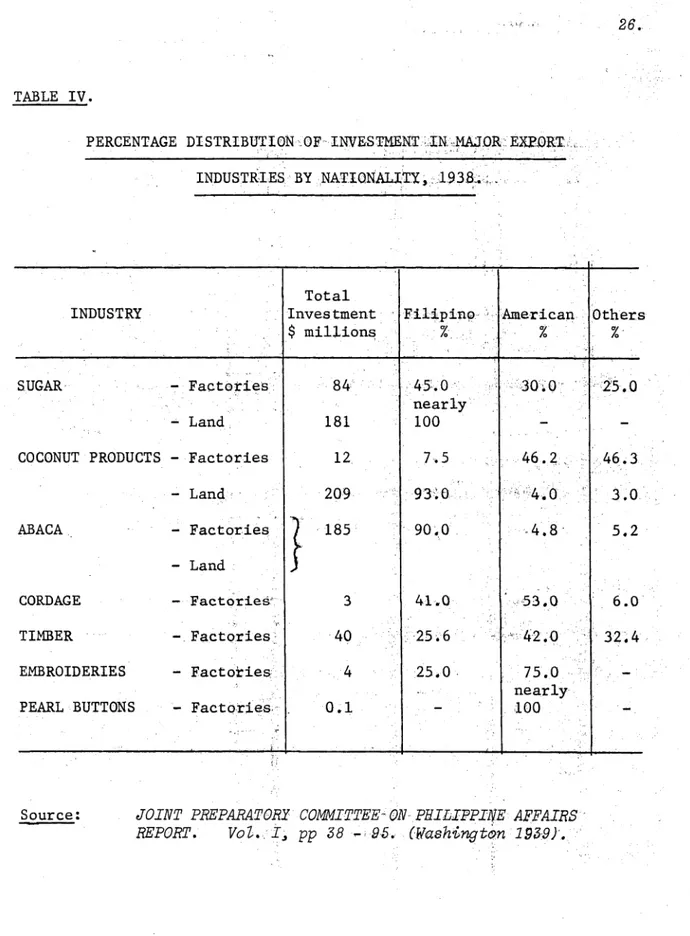

of American capital as of 1938, show total investment to be around $200 million. Of this amount, about $70 million only was invested directly in the export industries. Some indication of the importance of this investment is given in the following table of the percentage distribution of investment in the major export industries (see Table IV).

The table shows American investment to be concentrated in the processing sector of these industries while the crop cultivation is almost wholly Filipino. But these figures cannot be taken as a strict index of importance since much of the expansion in agricultural production was contingent upon the expansion of the processing

activities. Because of this the term "dependence" has little mean ing if used to assess the extent to which the Philippine economy relied upon its preferential trade relationship with the U.S.

It should also be noted that not all these industries and the American investment in them were the fruits of free trade. Copra, timber, minerals and abaca were in any case not subject to any duty in the U.S. and their development was determined by factors other than free entry into that market. More details on this point are laid out in the next chapter where we take a closer look at the history of in dividual industries.

2 6.

TABLE IV.

PERCENTAGE DISTRIBUTION OF INVESTMENT IN MAJOR EXPORT INDUSTRIES BY NATIONALITY,

1938-INDUSTRY

Total Investment $ millions

Filipino %

American %

Others %

SUGAR - Factories 84 45.0

nearly

30.0 25.0

- Land 181 100 -

-COCONUT PRODUCTS - Factories 12 7.5 46.2 46.3

- Land 209 93.0 4.0 3.0

ABACA - Factories

- Land

| 185

90.0 4.8 5.2

CORDAGE - Factories 3 41.0 53.0 6.0

TIMBER - Factories 40 25.6 42.0 32.4

EMBROIDERIES - Factories 4 25.0 75.0

nearly

-PEARL BUTTONS - Factories 0.1 100

Thus by much the most significant developments in the Philippine economy during the American rule were the rapid growth of

foreign trade and its concentration upon the United States. The pattern of specialization lay in the export of semi-processed agric ultural products and the imports of finished industrial goods and basic foodstuffs (meat, dairy products, wheat flour, fish products)

in which the Philippines appeared to have a comparative disadvantage. There was very little industrial development and what little there was, was mostly in the export industries - sugar centrals, coconut

oil mills, desiccated coconut factories, rope factories, cigar factor ies, pineapple canning, fibre hats. Approximately two-thirds of

I

manufacturing output in 1938 was destined for the export market, and a significant proportion of the remainder consisted of handicraft manufacturing in households and small workshops.

Observers in the latter part of this period were quick to note these features. Willis's observation in 1906 was re-echoed in

1938 :

" .... the present degree of industrialization is infinitessimal....as regards industrialization in the sense of large-scale manufacturing production, the Philippines may be classified as a non-industrial-ized country which has changed very little in the

2

last forty years."

1. Based on the CENSUS OF MANUFACTURES 1938 and the REPORT OF INSULAR COLLECTOR OF CUSTOMS 1938.

28

.Writing in the same year Mindinueto states that:

"The Philippines is still in the infant industry stage. Outside Manila and Cebu City, the indust ries are generally of the household type with . stray small factories here and there of a few hundred pesos of investment and a handful of

operators. The mechanised industries are

some-1

thing new to the provincial population.

These generalisations are amply confirmed by the 1938 Census of Manufactures which enumerated 139,407 establishments (80 per cent of which were household industries) producing an output valued at P357*3 million with an employment of 170,956 workers and a capital stock of P356*4 million. Of this output food manufactures accounted for 67*5 per cent, textiles 7*8 per cent, household goods and furnish ings 3*3 per cent. The prominence of the food industries is due to the sugar centrals which produced 31 per cent of total manufacturing output. Industries producing for the home market consisted in most cases of one or two medium sized factories.

The state of manufacturing activity in 1938 shows a marked progress when compared to 1903. Then there were only 2,704 establish ments enumerated by the census and output was valued at P40.9 million while the value of capital invested was only P50.7 million. These

figures for 1903 however represent only the marketed output. There was also as the census report noted, a significant amount of

pro-1. S. R. MINDINUETO "Industrial Philippines" in CON GRES INTERNATIONALE DE GEOGRAPHIC, Vol. 2, See 30.

duction carried on in households for self consumption.

IV.

Thus in the early 1930’s the Philippines had adapted itself to a colonial economic status and had done by no means badly in that condition. But the outlook was dominated by the prospects of the independence it was partly seeking and partly having thrust upon it by the idealism of the United States (and the vested interests who suffer ed from the price admission of Philippine products). It was accepted then (more unquestionably than has been the case in e.g. post war Africa) that independence entailed the loss of privileges in the U.S. market, and much of the negotiations at the time turned on the trans

itional provisions required to enable this vast change to be made without economic disaster.

30.

additional 5 per cent every year until in 1946 when at 25 per cent they would equal the prevailing U.S. import duty. But the Philippine govern ment could not impose any tariffs or quota restrictions on imports from

the U.S. until 1946. Full duties could then be applied by each country to their respective imports.

These trade provisions were more a political compromise than the fruit of any real consideration of the transitional’needs of the Philippine economy. No one really knew what was required for this transition and a proper investigation was not made until the Act passed both legislatures. Philippine leaders were not satisfied with the trade provisions of the Act, but rather than delay independence, they accepted the Act in the belief that changes could be made

after-1

wards. This belief was based on a statement by President Roosevelt to Congress (March 2, 1934)

"I do not believe that further provisions of the original law need to be changed at this time. Where imperfections and inequalities exist I am confident that both can be corrected after proper

2

hearing and in fairness to both peoples."

Efforts to obtain more satisfactory terms were renewed immediately after the Act was passed by both legislatures in 1934.

1. President Quezon stated before the U.S.Senate Committee

on Insular Affairs that3 "there are-of course-' other provisions of the bill to which we object but we are willing to take it as it is now and we have given up any attempt at this time to have it in any way amended because we are relying upon the statement made by the President in his message to Congress> March 2, 1934. " Quoted in the Report of I

V. S. JOINT PREPARATORY COMMITTEE ON PHILIPPINE AFFAIRS. Vol. 13 p. 8

B e t w e e n 1934 a n d 1937 v a r i o u s c o m m i t t e e s made p r e l i m i n a r y s t u d i e s o f

t h e P h i l i p p i n e economy and i t s t r a d e r e l a t i o n s w i t h t h e U . S . F i n a l l y

i n 1 93 7 , t h e J o i n t P r e p a r a t o r y C om m i t t e e on P h i l i p p i n e A f f a i r s was

a p p o i n t e d t o s t u d y f u r t h e r t h e p r o b l e m o f P h i l i p p i n e - A m e r i c a n t r a d e

r e l a t i o n s a n d t o s u b m i t a r e p o r t w i t h r e c o m m e n d a t i o n s t o r emo ve any

" i m p e r f e c t i o n s a n d i n e q u a l i t i e s " i n t h e I n d e p e n d e n c e A c t and t o a l l o w

t h e economy t o a d j u s t t o t h e new t r a d e r e l a t i o n s .

The C o m m i t t e e made e s t i m a t e s o f t h e p r o b a b l e a d v e r s e e f f e c t s

o f t h e new t r a d e c o n d i t i o n s on e a c h of t h e e x p o r t i n d u s t r i e s and on t h e

economy i n g e n e r a l . I n t h e l i g h t o f t h e s e f i n d i n g s , i t recommended

t h e c h a n g e o f t h e d a t e o f t h e a p p l i c a t i o n of t h e f u l l U . S . t a r i f f f rom

1946 t o 1961 i n o r d e r t o p r e v e n t a t o o a b r u p t c o n t r a c t i o n o f some o f

t h e e x p o r t i n d u s t r i e s . I t a l s o recommended t h a t t h e e x p o r t t a x e s i n

t h e p e r i o d 1 9 4 1 - 4 6 b e c h a n g e d t o g r a d u a l l y d e c r e a s i n g d u t y f r e e q u o t a s .

The U. S. C o n g r e s s r e j e c t e d t h e f i r s t s e t o f r e c o m m e n d a t i o n s ,

b u t i n c o r p o r a t e d t h e l a t t e r i n t h e T y d i n g s - K o c i a l k o w s k i Ac t o f 1939.

The new Act was b e l i e v e d t o h a v e p r o v i d e d f o r " a more o r d e r l y l i q u i

d a t i o n " o f t h o s e e x p o r t i n d u s t r i e s m o s t s e r i o u s l y a f f e c t e d by t h e

l o s s o f t r a d e p r e f e r e n c e s .

I n a l l i t s t h i n k i n g a b o u t t h e t r a n s i t i o n , t h e P h i l i p p i n e

g o v e r n m e n t e n v i s a g e d t h e a d j u s t m e n t s i d t e r m s o f s e l f - s u f f i c i e n c y and

r e d u c e d d e p e n d e n c e on f o r e i g n t r a d e . I t was as su me d t h a t t h e i r

1. For d eta ils o f the recommendations and the analysis o f

the adverse e ffe c ts on the export in d u s tr ie s s e e the

R

eport of the committee3

v o i

. i.

2.

These were later incorporated in the Bell Trade Act o f

32

. primary exports could not be successfully redirected to other markets. This was perhaps a reasonable assumption considering the state ofworld trade in the 1930's. A search for new markets in those conditions would certainly have been painful and would most likely have involved much worse terms of trade than they had been accustomed to in the past. Hence, it is not surprising that the answer was seen to lie, unquest

ionably, in industrialization, a panacea that was gaining popularity in many other countries at that time.

It was also taken for granted (and apparently with little understanding of the financial and administrative problems involved) that this industrialization could and should be undertaken directly by the government. One suspects that the interventionist spirit of the New Deal and even ancestral memories of Spanish colonial planning contributed more to this attitude to the problem than any practical consideration of the feasibility of the task which the government had set itself.

Some description of what was done will be given in chapter 4. But very little had been achieved when Japan invaded the country in 1941 and all programmes of industrial development were then, nat urally, abandoned. The war added the problems of reconstruction to those already faced by the government of the Philippines when as scheduled, it became fully independent on July 4, 1946.

34

.C H A P T E R 3.

Manufacturing for Export: 1900 - 40.

I.

The economic history sketched in the last chapter makes it clear that the development of export industries had dominated the growth of the economy for almost a hundred years before World War II. It was also observed that industrialization during this period consist ed of little else besides the growth of processing factories in this sector. We now discuss the details of this growth. Section II be gins the analysis with a description of the change from subsistance to commercial agriculture for export which preceded the industrializ ation of this period. Its value is more than a historical background. For the forces underlying this change were chiefly responsible for the subsequent change from handicraft to factory production in the processing of these agricultural exports.