AND WORLD TRADE

E

u r o p e a n

U

n io n

t r a d e

d e v e l o p m e n t s

FOR THE YEAR 1996,

COMPARISON WITH THE UNITED STATES AND JAPAN

★

★

Cataloguing data can be found at the end of this publication.

Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, 1997

ISBN 92-828-2282-6

© European Communities, 1997

Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged.

Printed in Belgium

GENERAL REMARKS...

i

SUMMARY OF DEVELOPMENTS ... ii

CHAPTER 1 - WORLD ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENTS...

1

Trade in goods and commercial services... ... 3

Developments of merchandise trade in volume by region... 4

CHAPTER 2 - EUROPEAN UNION EXTERNAL TRADE...

7

CHAPTER 3 - UNITED STATES EXTERNAL TRADE ... ... 14

CHAPTER 4 - JAPANESE EXTERNAL TRADE... 20

CHAPTER 5 - EUROPEAN UNION UNITED STATES JAPAN TRADE -

BREAKDOWN BY PRODUCT GROUP... ...

27

SPECIAL SUBJECT

Regionalism in world trade...

40

1) Sources and trade data

Data for the European Union for 1995 and 1996 originate from the database COMEXT of

EUROSTAT. However, data from 1992 to 1994 are extracted from the COMTRADE

database managed by the UN Statistical Office. This is also the source for the US and

Japanese figures from 1992 to 1996.

Import values include CIF (cost, insurance and freight) and export value are FOB (free on

board).

All trade flows (imports, exports and trade balances) reflect the data as given by the

reporting countries. There may be a divergence between the level of trade reported by

one country and the equivalent trade flow reported by a partner country.

2) Country groupings

The aggregate of the various country groupings is not equal to the value of "EXTRA 15" or

"WORLD", since some countries appear in more than one grouping, whilst others are not

included in any group. The composition of the various groupings is listed in the annex.

3) Exchange rates (1 ECU - ...)

Year

US dollar

Yen

1992

1.298

164.20

1993

1.172

130.10

1994

1.190

121.31

1995

1.308

123.01

1996

1.270

138.08

Signs and abbreviations

data not available

percentages exceeding 1000

bn

billion

World economic growth quickened during 1996 (+4% in real terms) following

widespread deceleration of activity in 1995.

The favourable global economic conditions were underscored by the continued

robust performance with low inflation in the United States, the pickup in growth in

Japan and a moderate recovery in the European Union and Canada.

Among the developing countries, activity strengthened in Africa, Middle East and

Latin America and more than compensated for the moderate slowdown in some

developing Asian countries.

For the countries in transition, considered as a group, the contraction of the economic

activity seems to have bottomed out in 1996 after six years of deep decline. However

the recovery in the Central and Eastern European countries was counterbalanced by

a fall in the Russian GDP.

The value of

world merchandise exports

showed a +3.7% increase in 1996

compared to 1995, totalling 5,100 bn US dollars. The slowdown in the growth rate

(from nearly +20% in 1995) exceeded by a wide margin the deceleration in volume

terms, as dollar prices of globally traded goods stagnated in 1996 after increasing by

+10% in 1995.

Also, exports of commercial services slowed down remarkably in 1996 (+5% growth

rate compared to +14% in 1995) and reached the value of 1,200 bn US dollars.

In volume terms, world trade growth was similar to the growth reported for the first

four years of the decade and below the levels recorded in 1994 and 1995, that were

unusually high. As a result, the large excess of trade growth over output growth

observed each year since 1990 was sharply reduced in 1996.

Among the reasons for the important slowdown of world trade growth in 1996, there

was the easing of the industrial countries' imports and the sluggish performance of

Asia. The export growth of this region in 1996 was not only below its output growth,

but also the smallest among the analysed regions.

On the contrary, Latin America registered a very outstanding export performance

(nearly triple the world average).

The value of EU merchandise trade balance,

which had been always in deficit since

1958 (except for the 1986-87 small surpluses) turned into the black in 1994, and

reached a remarkable figure of +43.4 bn ecu in 1996. This was mainly due to the

turnaround of the EU-US balance into a small surplus, and to the constant reduction

for the fourth consecutive year of the huge trade deficit with Japan.

On the products side, the European Union’s structural deficit in the primary sector

(almost completely concentrated in the fuel products sector) was more than

compensated for by the surplus in manufactured products (which more than doubled

between 1994 and 1996).

as compared to that of the European Union. The bulk of its deficit is concentrated in

the manufacturing sector while in the primary sector (excluding the fuel products

deficit) agricultural products and other raw materials are structurally in surplus.

The combination of the economic recovery and the structural changes which

occurred in the Japanese trade patterns, due to the increase of FDI abroad, more

than compensated for the increase in price competitiveness due to the yen

devaluation, which began in the last quarter of 1995. As a consequence, Japanese

trade surplus in ecu terms went down again in 1996 to +48.6 bn ecu. The fall in the

Japanese overall trade surplus was mainly accounted for by the decline in the

manufactured products surplus, although the traditional Japanese deficit in primary

products also widened.

All the Triad countries registered a deterioration of their primary products deficits in

1996. Boosted by the increase in the international oil prices, imports of primary

products registered quite dynamic growth rates that, for the EU and the USA, were

even bigger than the corresponding rates for manufactured products. On the

contrary, export growth was more moderate and, in the case of Japan, even negative

(in line with the overall reduction of the ecu value of Japanese imports).

WORLD ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENTS

WORLD ECONOMY

+4% real growth in

world output in 1996.

Advanced economies

went up by +2.5%.

Developing countries

output was quite

dynamic with a

+6.5% growth rate.

Recovery started in

the transition

economies (+0.1%).

The advanced

economies (15%

world population)

produced 57% of the

world GDP; while

developing countries

(77% population)

less than 40%.

Industrial countries'

GDP grew by +2.3%

in 1996.

EU output went up by

a mere +1.6%.

Japanese and US

economies expanded

briskly (+3.6% and

+2.4% respectively).

Growth in the NIEs

slowed down as a

result of a slowdown

in exports.

In 1996 the world economy grew by +4% in real terms1. This

result was due to a combination of a relatively moderate growth

of +2.5% registered by the “advanced economies”2, a still

buoyant momentum (+6.5%) in the developing countries and

the start of the recovery among the transition economies,

whose GDP grew by 0.1% compared to the previous year.

On the one hand, this growth was accompanied by a low level

of global inflation, and by the reduction of fiscal imbalances in

many countries, which should help contain real long-term

interest rates and foster higher investment.

On the other hand, economic growth is not yet sufficiently high

to solve the big employment problems in the industrialised

countries and to reduce the areas of poverty in many

developing countries.

However, wealth seems to dwell on a more and more enlarged

share of the world population. In 1996 the output per capita

went up by +1.9% in the advanced economies (representing

56.6% of the world output and 15% of the world population),

while it jumped by +4.9% in the developing countries (where

77% of the population produces 39.2% of the total output).

The year 1996 was characterised by a quite important recovery

in the traditional

industrial countries

(+2.3% GDP growth

rate, the best result since 1989).

In the

European Union

growth was moderate for 1996 as a

whole (+1.6%), but economic activity recovered during the year

from the set back triggered by the monetary turbulence of

1995. Progress in convergence achieved on the road towards

EMU, as witnessed by budgetary consolidation and improved

price stability, makes it less likely that macroeconomic

obstacles, like a distorted policy-mix or monetary turbulence,

harm sustained growth and job creation in the future.

Outside the European Union, the dramatic increase in the

revenues of energy products export boosted the output in

Norway,

while in Switzerland the protracted recession due to

weak internal demand left the economy stagnant for the sixth

successive year.

The

United States economy expanded by +2.4% in real terms

and inflationary pressures remained low despite high resource

utilisation, including a tight labour market.

The recovery in Japan became more broadly based in 1996

(+3.6% in real terms) and the economic climate improved

under the influence of supportive fiscal and monetary policies.

Among the other countries recently included in the “advanced

economies” grouping, in Israel the recent restrictive economic

policies slowed down the output growth rate to a (still

remarkable) +4.4% in 1996. The protracted trend of economic

growth in the NIEs continued, even if at a slower pace partly as

a result of a slowdown in exports. Output in Korea went up by

+7.1% in 1996, followed by Singapore (+7%), Taiwan (+5.6%)

and Hong Kong (+4.5%).

The +6.5% increase in the global GDP of the developing

countries is the result of the important output growth in Africa

(+5%), the Middle East (+4.5%) and Latin America (+3.5%)

which more than compensates for the moderate slowdown in

some developing Asian countries. However, the latter area still

showed an important rate of growth (+8.2%).

Africa’s growth performance in 1996 (+5%, the strongest in

the last 20 years) was boosted mainly by the strong expansion

of the primary sector, in particular agriculture. However, in

some countries, the growth also included the manufacturing

sector. Improved production performances reflect continuing

advances in liberalisation efforts and the macroeconomics and

structural policies being introduced by a number of low-income

African countries.

In South Africa, the region’s most important economy, reforms

and stabilisation policies enhanced the growth, even if the

+3.1% increase was somewhat weaker than expected.

Growth in the Middle East region (+4.5%) was stronger than

expected, partly as a result of economic reforms introduced in

recent years, but also reflecting the higher-than-projected level

of oil prices. The combination of structural reforms, together

with cyclical factors, led to particularly positive GDP growth

rates for Egypt, Jordan, Syria, Lebanon and the Arab Emirates.

In contrast, lax fiscal and monetary policies and rampant

inflation could threaten the economic outlook in Turkey.

In Asia3 the slowdown towards more sustainable expansion

rates is partly the result of tight monetary policies established

to dampen the growth of domestic demand and avoid the risks

of overheating.

In addition, the slowdown in the region’s export growth in 1996

helped contain inflationary pressures in India, Malaysia,

Indonesia and Thailand.

China has also taken measures to reduce overheating (soft

landing policy) and real GDP growth slowed to just under

+10% with inflation slowing further to 6%, down from +22% in

1994.

In many Latin American countries, the economy is continuing

to recover following the 1995 Mexican crisis. In particular,

3 This text refers only to the 1996 developments. The effects and consequences of the 1997 financial crisis are therefore not included in this text.

2

In the developing

countries as a group,

growth picked up to

+6.5% in 1996 from

+6% the previous

year.

output grew remarkably in Mexico (5.1%) and Argentina (4.4%)

which together represented more than 40% of the global GDP

of this region. In Brazil growth slowed down slightly while

inflation fell to 9% by the end of the year, the lowest in the last

35 years. In Chile, the most successful economy in the region

(+7.2% growth), inflation fell to a 36 years low of 6.5% and

demand pressure eased in response to tighter monetary

policies.

Beginning of a

recovery in the

transition countries.

Output grew by

+0.1% in 1996.

CEECs economies

showed a +1.6%

growth for the

second consecutive

year.

Russian GDP

dropped again by

-2

.

8

%.

In contrast, the other

former USSR

Republics grew

slightly.

For the

countries in transition,

considered as a group, the

contraction of the economic activity seems to have bottomed

out in 1996 (+0.1 %)4 after six years of deep decline. However

among them individual countries showed quite different trends.

For the second consecutive year in 1996, the global output of

the

Central and Eastern European countries

showed a

recovery (+1.6%). Most of these countries are now reaping the

rewards of structural reforms and stabilisation policies pursued

with determination over several years. The economic

performance was positive in Croatia, the Czech and Slovak

Republics, Poland, Romania and Slovenia, thanks to the

growth in the manufacturing sector and increase in the internal

demand. In Hungary, by contrast, the growth slackened due to

tight monetary and fiscal policies, while the Baltic States

continued their recovery.

Russian GDP continued to fall in 1996 (-2.8%) due to a drop in

both production and investments, even if some important

results were obtained on price stabilisation. On the contrary,

the other former Soviet Union Republics,

except Tajikistan

and Turkmenistan, registered positive growth rates. These

were particularly strong in Georgia, Armenia and Kyrgyz

Republic.

Trade in goods and commercial services

According to WTO estimates, the 1996

value of world

merchandise exports

(5.100 bn dollars) showed a +3.7%

increase compared to the previous year. This slowdown in the

growth rate (from nearly 20% in 1995) exceeded by a wide

margin the deceleration in volume terms, as dollar prices of

globally traded goods stagnated in 1996 after increasing by

10% in 1995. As a matter of fact, price increases for crude oil

and certain other primary products were offset by the changes

in the exchange rate of the US dollar vis-a-vis the currencies of

several major traders5. In 1995 the situation was exactly the

opposite with the dollar values “swollen up” due to the

American currency depreciation.

Trade in products which had benefited from exceptionally

4 It should be emphasised that output data for these countries may underestimate actual growth because they may

WORLD TRADE IN

GOODS AND

SERVICES

In 1996, world

exports of goods and

services grew by

+3.7% and 5%

respectively in value

tenris.

Commercial services

increased by 5%

reaching $US 1,200

billion.

World trade (goods

and services)

represented 21% of

the world GDP that

was estimated at

almost $US30,000

billion.

World trade

(goods+services)

went up by 5.6% in

volume tenns.

strong demand and/or price trends in 1995 - office and telecom

equipment, iron and steel, and non-ferrous metals - was

affected by price declines and weaker demand in 1996.

Consequently, the growth in the value of trade in these

products was less than 5% in 1996. In contrast, exports of

fuels increased by more than 10% in value terms - the biggest

annual gain in trade since 1990 (29%).

Also exports of commercial services slowed down

remarkably in 1996 (+5% growth rate compared to 14% in

1995) and reached the value of 1,200 bn dollars. This can be

attributed both to the effect of the dollar's appreciation against

a number of major currencies, and to the sluggish economic

activity in Western Europe6 which alone accounts for one-half

of the world's trade in commercial services.

Even if there is no perfect comparability, due to differences in

statistical methodologies, the global value of exports of goods

and commercial services amounted to 6,300 bn dollars. This

represented around 21% of the world GDP at market prices

(30,000 billion US dollars in 1996).

The IMF estimated the growth rate of world trade7 in volume

terms at +5.6%. As is evident from Figurel .2, the increase in

1996 was similar to the growth reported for the first four years

of the decade and below the levels recorded in 1994 and 1995

that were unusually high.

As a result, the large excess of trade growth over output

growth observed each year since 1990 was sharply reduced in

1996. This change can be attributed primarily to developments

in Asia, where trade growth (both exports and imports) fell

below GDP growth. While the gap between trade and GDP

growth also narrowed in other regions, trade growth (exports

and imports combined) remained at least twice as large as

GDP growth in North America, Latin America and Western

Europe.

Developments of merchandise trade in volume by region

WORLD TRADE IN

GOODS

The volume of world

merchandise exports

went up by +4% in

1996.

Remarkable

slowdown of Asian

trade (+2%).

In 1996, world merchandise exports increased by an

estimated +4% in volume terms8, slightly less than half the rate

recorded in 1995 (Table 1).

The surprising feature of the geographic breakdown of 1996

trade developments was the performance of Asia. Export

growth in 1996 (+2.5%) was not only below output growth, but

also the smallest among the regions. Asia's imports held up

somewhat better, matching the world average and exceeding

export growth by 2 percentage points. A partial explanation of

this performance could be the above-average importance of

office and telecom equipment in Asia's exports, which implies

that the “boom and bust” cycle of this product group had a

stronger impact in Asia than elsewhere. In addition, exchange

6 WTO grouping including the 15 EU member States, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Malta, Norway, Switzerland, Turkey, Bosnia, Croatia, Slovenia, FYROM and Serbia-Montenegro.

7 Goods and services.

8 WTO Secretariat's report on trade developments in 1996, (world includes intra-EU trade).

Industrial countries'

trade also registered

a more moderate

growth rate (+6.3%).

Intra-EU trade nearly

stagnated (+2%),

while EU exports to

third countries grew

above the average

(+5%).

Outstanding export

performance of Latin

American countries

(globally up by

+

11

%)

Imports of the

countries in transition

registered the most

dynamic growth

(+12%).

rate developments - in particular the stronger dollar - reduced

competitiveness of those countries which peg their currency to

the United States dollar.

The other reason for the important slowdown of world trade

growth in 1996 was the easing of the industrial countries’

imports

that together represented around two thirds of world

imports. This slowdown (from 7.7% in 1995, to 6.3% in 1996

according to OECD estimates) involved the main European

Union countries (except the UK), the USA and in particular

Japan and Canada. As the EU accounts for roughly 40% of

world merchandise trade, the impact on global trade was

marked.

After two years of strong growth9, intra-EU exports nearly

stagnated in 1996 (+2%), while exports to third countries rose

by +5%, a rate significantly faster than extra-EU imports

(+2.5%). Consequently, as in 1995, external demand helped to

sustain output in the EU during 1996.

The

outstanding export performance of Latin America

(nearly triple the world average) can be attributed largely to

Mexico, where export volume expanded by more than +20%

for the second year in a row. Excluding Mexico, Latin

America's exports expanded by +5% in both 1995 and 1996. In

contrast, Brazil's export volume has been stagnant in the last

two years.

Latin America's imports, which grew in volume terms by only

+3% in 1995 due to the sharp recessions in Mexico and

Argentina, recovered strongly in 1996 with an expansion of

+10.5%. Among the major traders, Argentina's and Mexico's

imports were up +17% and +24% respectively, with the result

that the steep fall in imports provoked by the recession in 1995

has been completely offset. A particularly strong deceleration

could be observed for Brazil where the volume of imports, after

expanding by more than one-quarter annually between 1993

and 1995, only increased by about +6% in 1996.

Exports of the transition economies,

which recorded the

strongest export growth of all the major regions in 1995 (up

+14.5%), decelerated sharply in 1996 to just under the global

average. Import growth, in contrast, reached +12% in 1996, the

highest level among the major regions.

Table 1 - GROWTH IN WORLD MERCHANDISE TRADE BY SELECTED

COUNTRIES/REGIONS

(Annual % change in volume)

EXPORTS

IMPORTS

1995

1996

1995

1996

WORLD

8.5

4.0

8.5

4.5

USA (a)

10.6

7.6

8.9

7.0

European Union (b)

7.3

4.0

5.6

2.5

Latin America

12.0

11.0

3.0

10.5

Transition Economies

14.5

13.5

11.5

12.0

Asia

9.5

2.5

14.0

4.5

Japan (a)

3.3

0.5

12.5

3.4

Six East Asian traders(c)

14.5

3.5

15.5

4.0

Source: W T O and (a) O E C D (b) Extra + Intra-Trade

(c) Hong Kong, South Korea, M alaysia, Singapore, Taiw an and Thailand

%

Fig. 1.2 - World GDP and trade (goods+services)

(annual % change in volume)

—-#— Trade GDP

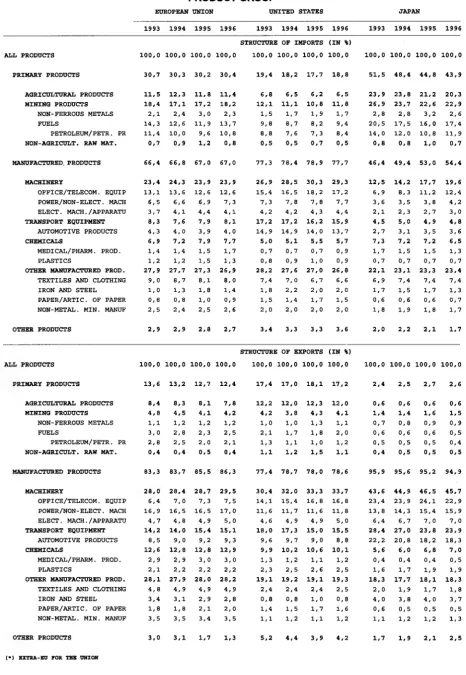

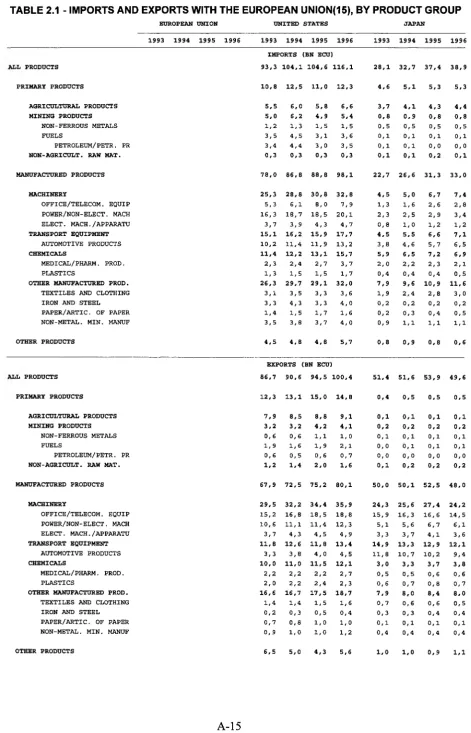

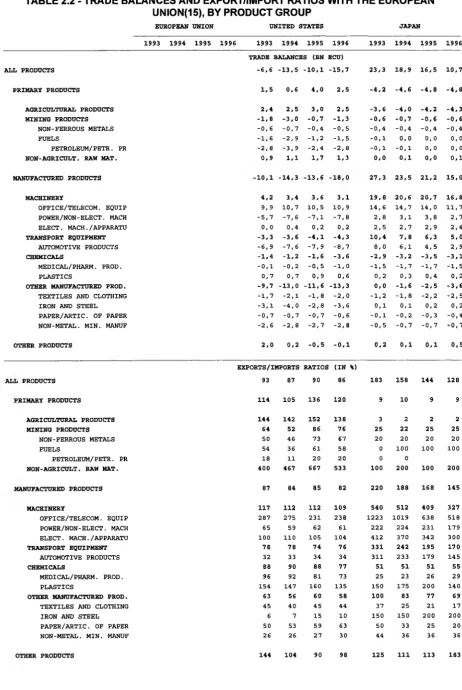

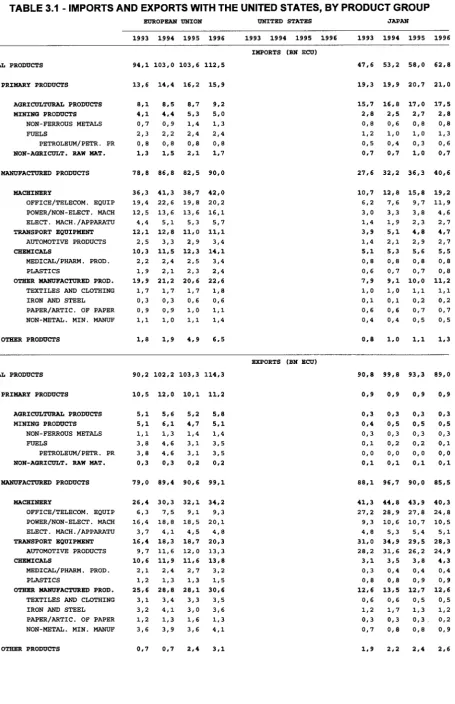

[image:12.595.99.510.559.781.2]EUROPEAN UNION EXTERNAL TRADE IN GOODS

TRADE BALANCE

BY PARTNER

The merchandise

trade balance of the

EU registered a

remarkable surplus of

+43.4 bn ecu in 1996.

This is the third

positive result in a

row.

The EU-USA deficit

turned into a +1.8 bn

ecu surplus.

Remarkable

increases in the

surpluses with the

CEECs, the

Mediterranean

countries and the

NIEs.

The biggest deficits

were registered with

Japan and China (-17

and -15 bn ecu

respectively).

The EU trade balance, always in deficit since 1958 (except

for the 1986-7 small surpluses) turned into the black in 1994,

progressed further in 1995 and reached a remarkable figure of

+43.4 bn ecu in 1996. This last result was due to the

combination of a still buoyant export growth rate (+8.9%), and

of a slow rate of imports that went up by only +6.5%.

The EU’s trade balance with the group of countries made up of

the USA, Japan, Canada, EFTA and Australia-New Zealand

improved considerably in the last four years. The deficit was

reduced from the -35 bn ecu registered in 1993 to less than -

12 bn 1996.

This was mainly due to the turnaround of the EU-US balance

into a small surplus, thanks to the vitality of the American

economic climate and the appreciation of the dollar against the

ecu (+3%). Another reason was the constant reduction for the

fourth consecutive year of the huge trade deficit with Japan (to

-17 bn ecu), despite the deterioration of the EU competitive

position as the ecu appreciated by +11 % vis-a-vis the yen in

1996. On the other hand, the balance with the 3 EFTA

countries that was almost in equilibrium in 1995 registered a

small deficit of -2.2 bn ecu.

In 1996, the Union registered remarkable improvement in its

trade positions with the CEECs (the surplus almost doubled

from +8.8 to +16.4 bn ecu), the CIS (deficit down from -4.1 to

-1.6 bn ecu), the Mediterranean Basin (the surplus increased

by +3.5 bn compared to 1995), Latin America (improvement

of +3.3 bn) and the 4 NIEs (from +10.5 to +13.5 bn ecu

surplus).

The trade balances with ACP and OPEC countries

deteriorated due to the increase in the international oil and

other commodities prices reaching -3.4 and -3 bn ecu deficits

respectively.

Trade with China1 registered the second largest trade deficit in

absolute terms reaching -15.3 bn ecu (compared to -7.4 bn

ecu in 1993). However, in relative terms (i.e. as a percentage

of bilateral trade) the EU-China trade recorded the highest

deficit in 1996 (-34.3%), whereas Japan ranked in second

place (-19.1 %). [See fig. 2.1.]

EXPORTS BY

PARTNER

EU exports up by

+9% in value terms

and +5% in volume in

1996.

USA largest outlet

with 18.3% share.

Exports to CEECs

and CIS grew by

more than +19%.

Slowdown of EU

sales in Asia.

Dynamic momentum

of the exports to the

Mediterranean.

IMPORTS BY

PARTNER

After the slowdown in

1995, EU imports

increased by +6.5%

in value and around

+2.5% in volume in

1996.

USA first supplier with

almost 20% share.

Purchases from

China and ASEAN

countries expanded

at a double figure

rate.

Imports from oil

producer countries

went up by +15.5% in

value.

Dynamic momentum

of the ACP sales.

sales to Japan (stable at 5.7% share) registered a growth rate

slightly below the average (+8.2%).

Benefiting from the continuing structural strengthening of the

economy in the CEECs and the CIS, the value of exports to

these country groups expanded considerably, by more than

19%. This further increased the share in total EU exports to

10.2% for the CEECs, and 4% for the CIS.

After three years of extremely dynamic expansion, EU exports

to the Asian region slowed down, in particular to South Asia

(+4.7% growth rate) and China (+0.7%). However, since 1993

the Asian countries, with the exception of Japan, increased

their global share of the EU exports by +1.5%, going from

16.1% to 17.6%.

Exports to the Mediterranean Basin continued to grow even if

at a more moderate rate (+12.4%), resulting in an increase in

the share of these countries to 11.6% of total EU exports.

[See figs. 2.2 and 2.3.]

The value of EU purchases from the rest of the world

increased by +6.5% in 1996. This result was due to the +4%

increase in average import prices, while the quantity's growth

rate was only +2.5%.

Imports from Japan dropped by -3.3% in 1996. In the last four

years, a constant reduction in the Japanese share of EU

imports has occurred: it was 9.1% in 1996, compared to 12%

in 1993.

By contrast, the US sales to the EU markets increased well

above the average (+8.6%) after having stagnated in 1995.

This was probably due more to the effect of the dollar

appreciation (average import prices went up by +6.5%) than to

the slow economic recovery in Europe. As a result, the share

of US goods in total EU imports increased to 19.4%.

After the boom experienced in the last 3 years, imports from

the CEECs reduced their dynamism slightly below the average

(+6.1%), almost at the same rate registered by imports from

the CIS. However, as far as the former Soviet Union Republics

are concerned, the import slowdown had already begun in

1995. Nevertheless, their global share increased remarkably

in the last four years, reaching 12.7% in 1996.

Imports from Latin America (5.2% of the total) stagnated in

1996. Imports from South and Southeast Asia including

China (which alone represents 5.2% of the total EU

purchases) expanded at a double figure rate with the relevant

exception of the 4 Asian NIEs, whose sales to the European

Union, after the -3.5% drop in 1995, increased by only +4.7%.

Also worth noting is the sharp increase in the value of imports

from OPEC, due to the higher oil prices in dollars (+21% in

1996) and the stabilisation of the recovery in the imports from

the ACP countries which registered a growth rate well above

the average for the third year in a row. [See figs. 2.4 and 2.5.]

TRADE BALANCE

BYPRODUCT

For the third

consecutive year, the

manufactured

products surplus

(+150 bn ecu in 1996)

more than

compensated for the

primary products

deficit (-99 bn ecu).

The largest surpluses

were registered in the

transport equipment

and machinery

sectors.

EXPORTS BY

PRODUCT

Exports of

manufactured

products up by +10%

in 1996, representing

more than 86% of

total exports.

Machinery and

chemicals were the

most dynamic

sectors.

IMPORTS BY

PRODUCT

Machinery and

transport equipment

was the most

important sector with

32% share.

Imports of fuel

The European Union economy, based on the manufacturing

industry, has a structural deficit in the primary sector.

The

absolute value of the deficit slightly increased in the last four

years, reaching -98.7 bn ecu in 1996. However, the

exports/imports cover ratio was stable at 44% - a stabilisation

in relative terms.

This deficit was almost completely concentrated in the fuel

products sector (-64.2 bn ecu) followed by the agricultural

products sector (-17.3 bn ecu).

Between 1993 and 1996, the

surplus in manufactured

products more than doubled,

topping +149.5 bn ecu in

1996. This was due to the positive gaps between export and

import growth rates during this period, witnessed by the

increase of the cover ratio in value for the manufacturing

sector from 124% in 1993 to 138% in 1996.

The largest surplus was registered in the transport equipment

sector (+46.9 bn ecu followed by the machinery (mainly non

electrical machinery) and chemical sectors.

[See fig. 2.6.]

The European Union is a

traditional exporter of

manufactured

products

and this specialisation

has

increased over the last two decades. At the beginning of the

80’s, the share of manufactured products in total EU exports

was around 70%, while in 1996 this figure reached 86.3%.

The corresponding reduction in the share of raw materials was

mainly due to the declining importance of EU exports in fuel

products

(2.5% in 1996). Meanwhile, exports of agri-food

products were fairly stable at around 7-8%.

Among the primary products, in 1996 only the exports of fuel

products, boosted by the previously mentioned increase in

international oil prices, registered a growth rate above the

average (+15%). On the other hand, sales of non-agricultural

raw materials dropped by -10.3%.

As far as manufactured products are concerned, the most

dynamic sectors in 1996 were

machinery and chemical

sectors with +11.8% and +9.9% growth rates respectively.

Agricultural imports

registered slow

growth for the second

consecutive year.

from 1985 when raw materials prices fell, the share of

machinery and transport equipment began increasing and it

became the most important sector, globally reaching 32% in

1996.

Other manufactured products

also achieved a

remarkable increase to almost 27% in 1996.

After the slowdown registered in 1995, due to the slower pace

of economic activity in Europe, in 1996 the growth of imports

of

primary products

went up by +7.1% in value terms. This

increase took place in a context of rising commodity prices.

Indeed, world prices for non-oil commodities rose by +6%

while oil prices grew at a faster rate: on average, the import

price of oil for the EU increased by more than +21% in dollar

terms. The depreciation of the ecu against the dollar (by -3%

in average terms) also increased the import bill. As a

consequence the

imports of fuel products

increased by

almost 23% in value, expanding their share in the total imports

to 13.7%, quite close to the 1993 level.

Finally, after having stagnated in 1995, imports of

agricultural

products increased by a mere +2.6%.

Fig. 21 - Geographic breakdown of EU trade balances in 1996

%

1 c

O

O

S

Hi JO .IB€ 8 g UJ j

© C O ° z <

N

z

*co

O a>

E

< B+■*

+5

« CO

—

I

3

<<

LU

(0

<<

CD

3

(0

w

3 « < c

r- CO

I

o<2

€0

OLU

%

2 0

-Fig. 2 2 - EU exports in 1996

(% change over 1905)

16-12.

8t-*

4 .

0.

BctraBJ

1

1

CO < ■o

1-CO LL c LU CO o

¥

Q . O C

o LU OJ

2

Q_

Q.

^

O

O

COo CO

N

z

.2

1

4-*(0

3

<

(0

(0

0

CO

c .2

35 »-

<

O

<0 (0

LU '25

5 <

<

CO

3

Z

<

LU CO

<

CO

o

■Q (0

<D

CQ

o

LU LU

O

20

15.

%

Fig. 2 4 - RJ imports in 1996

(% change over 1995)

UJ

-O-Fig. 2.5 - Geographical breakdown of EU imports, 1996

4 NIEs of Asia 7%

Others 15%

Fig. 2.6 - EU : Trade balances in primary products

and manufactured products

Bn ecu

200

~L

I Primary products Manfactured products .Trade balance 150 -100

50

0

-50-100

■

I

I

-150

US EXTERNAL TRADE IN GOODS

TRADE BALANCE

BY PARTNER

The US trade

balance showed a

-153 bn ecu deficit

in 1996.

The largest deficit

was registered with

Japan (almost -40

bn ecu), China (-33

bn ecu) and Canada

(-21 bn ecu).

Deficit with the EU

increased by 5 bn

ecu compared to

1995.

Small surpluses

occurred with

Australia-New

Zealand and the

Mediterranean

countries.

After the slow-down of the previous year, in 1996 the US

economy grew by +2.4%. The good economic momentum,

together with the return to a stronger dollar - a trend begun in the

second quarter of 1996 - boosted the US imports.

Consequently, the huge

US trade deficit that slightly reduced in

1995 went up again in 1996, reaching -153.4 bn ecu. However,

due to the positive gap between exports and imports growth

rates, if measured in relative terms, the deficit decreased slightly

from -13.8% to -13.5% of total US trade.

The largest trade deficit was again registered with

Japan.

However, it was reduced substantially, by over 8 bn ecu, to less

than -40 bn ecu - the lowest level since 1992. On the contrary,

after a drop in 1995, the deficit with theEU increased in 1996 by

more than 5 bn, reaching -15.7 bn ecu.

The trade balance with the

four newly industrialised

economies of Asia continued to improve slightly, while the deficit

with

China,

the second largest, grew dramatically totalling -33.4

bn ecu. The export/import ratio with China plunged to 22 per cent,

which is by far the lowest of all major US ratios.

Trade with Asia

as a whole represented 70% of the 1996 US

deficit in spite of the remarkable improvement in the trade

balance with Japan.

Meanwhile, the US trade balances with

Canada

(the most

important trading partner) and with the

Latin American

countries continued to reduce in 1996, reaching -21.4 and -14.6

bn ecu deficit respectively.

Finally, the US registered small surpluses with only Australia-

New Zealand and with

the Mediterranean countries

(+6.3 and

+2.1 bn ecu respectively), while the trade balance with the Gulf

States was almost in equilibrium.

[See fig. 3.1.]

EXPORTS BY

PARTNER

US exports grew by

10% in 1996 in ecu

terms, compared to

a small 3.5% in

1995.

Canada (21%

share) and EU

(20.5%) were the

most important

export markets.

CIS, CEECs and

EFTA countries

were the most

dynamic outlets.

In 1996, the ecu value of US exports

showed a growth rate of

+10.1%, a remarkable increase after the slow-down registered in

1995. This performance is due to a combination of an increase in

volume (+7.6%) and in export prices, bolstered by the dollar

appreciation vis-a-vis the ecu (+3% on average in 1996).

The three most important outlets for US exports,

Canada, EU

and Japan,

registered growth rates below average and, as a

consequence, their shares were slightly reduced. Nevertheless,

these partners still represent 52.6% of the global value of US

sales to third markets.

By contrast, impressive growth rates were recorded in exports to

the

CIS, CEECs and EFTA countries.

However, their double

figure growth rates (+37%, +23.5%, +35.6% respectively) should

be connected with the still limited value of the exports to these

countries, that in 1996 globally represented less than 3% of the

total.

Sales to Latin

America reached a

remarkable 16.6%

share.

IMPORTS BY

PARTNER

Imports growth rate

+9% in 1996 (only

+1.7% in 1995).

Imports from EU

(the second supplier

after Canada) went

up b y +11% in 1996.

Imports from Japan

dropped for the

second consecutive

year.

Latin America and

OPEC sales grew

more than 20%

compared to 1995.

TRADE BALANCE

BYPRODUCT

Manufactured

products accounted

for 75% of the global

US deficit in 1996.

The deficit was

concentrated in the

automobile, textile

and computers

sectors.

Surpluses only in the

chemical and

agricultural products.

With the relevant exception of ASEAN, exports to the

Asian

countries

(including China) slowed down compared to the

remarkable performances of 1995.

On the contrary, sales to Latin

American countries,

after the

6%

drop registered during the

Mexican crisis of

1995,

grew by almost

18%,

increasing these

countries’ share to

16.6% of the total.

[See figs. 3.2 and 3.3.]

The value in ecu of

US imports

grew by

+9.3%

in

1996, 7.5

points more than the previous year. This must to a large extent be

attributed to the rise in the quantities imported (+7%).

After having stagnated in

1995,

the US imports from

EU

countries

went up by

+11%

in

1996.

This result reversed the

declining trend of the EU market share in the USA which

represented

18%

of the total (the second supplier after Canada

with

19.5%).

On the contrary, imports from Japan

went down

(-4.4%)

for the

second consecutive year and the Japanese share of the US

imports dropped by 4 percentage points compared to

1993, falling

to 14.4%.

The Asian countries

(except the NIEs) registered quite dynamic

growth rates in their exports to the American market. In particular

supplies from

China

went up by

+15.4%

in

1996

increasing this

country’s import share to 6.6% (5.6% in

1993).

In

1996, Latin American

sales to the United States

(60%

of

which came from Mexico) confirmed their strong momentum

which began in

1994,

recording a growth rate of more than

+20%.

In the last four years, the share of these countries in the total US

imports increased from

12.3% in

1993 to almost 15% in

1996.

Imports from

OPEC countries,

pushed by the rise in the

international oil prices, also increased by more than 21%.

However, the oil producers’ share of the American market was

still limited to a marginal 5.7%. [See figs. 3.4 and 3.5.]

The

product breakdown of the US trade balance

shows a

completely different picture as compared to the European Union.

As a matter of fact, in the primary sector - excluding the huge

fuel products deficit

(-51

bn ecu in

1996)

- agricultural products

and other raw materials are structurally in surplus (globally +20

bn ecu).

On the other hand, the bulk of the deficit is concentrated in

the

manufacturing

sector

(-114.5

bn

ecu).

Among

In the early 80’s the

structure of the US exports

was

characterised by a large share of raw materials (30% of the total).

In the last 15 years, however, a big shift occurred which made the

US export structure more similar to the European Union structure.

In 1996 the

primary products

represented only 17.2% of total

exports. These losses were distributed in all sectors even if the

recent increase in oil prices has boosted US exports of fuels

products

(+20% growth rate). Nevertheless their global value

was relatively small, covering only 2% of the total.

As far as

manufactured products

are concerned (79% of the

total in 1996); a partial shuffling in the relative weight of the

different sectors occurred. The

machinery sector

(in particular

office equipment and electrical machinery) increased its global

share by more than 3 percentage points since 1993. On the

contrary the

transport equipment sector,

despite the +14%

growth rate registered in 1996, lost 2.5 percentage points during

the same period.

Among

other manufactured products

(stable at 19% share), it

is interesting to note a 7% fall in the exports of iron and steel

(especially after the boom experienced in 1995) and the

remarkable increase in textile and clothing

sales (+14% growth

rate).

EXPORTS BY

PRODUCT

US exports were

concentrated in the

manufacturing

sectors (80% of the

total).

Good performance

of the US

manufactured

exports in 1996

(+11%), while the

primary products

sales slowed down

to a +5% rate from

+10.4% registered in

1995.

IMPORTS BY

PRODUCT

Primary products still

represented 19% of

the US total imports

in 1996.

Imports of primary

products up by

+16% compared to

1995.

Manufactured

products grew by

+7.5% only.

The structure of US imports also reflects the growing role of the

manufacturing sectors. Whereas, at the beginning of the 80’s, the

purchases of fuel products still represented one third of the total

value, a decade later their share had shrunk to 10% and than

stabilized in the most recent years at around 8-9%. This was

mainly due to the slump in energy prices and to the growing role

of intra-industry flows in international trade.

However, in 1996, the already mentioned rise in the oil prices

increased the import bill for these products by +27%. This factor,

together with the recovery in the US purchases of

agricultural

products

(+14.2% growth rate) more than compensated for the

dramatic fall (-22.5%) of non agricultural raw material imports. As

a result the

global share of the primary products

in the total

US imports went up by more than one percentage point

compared to 1995, reaching 18.8%.

The recent trends in the

manufacturing sectors

confirmed the

growing importance of the intra-industry trade.

Despite the 1996 slow-down, the share of the office equipment

went up by almost three percentage points in the last four years,

while the

transport equipment share

dropped by -1.3% in the

same period.

Fig. 3.2 - US exports growth rate in 1996

(% change over 1995)

Fig. 3.3 - Geographic breakdown of US exports in 1996

Others

OPEC

8%

Canada

Lat. Amer.

17%

25

20

.%

Fig. 3.4 - US imports growth rate in 1996

(% change over 1995)

(0

o

Fig. 3.5 - Geographic breakdown of US imports in 1996

Fig. 3.6 - U S : Trade balances in primary products and manufactured goods

1992 1993 1994 1995 1996