Theses Thesis/Dissertation Collections

8-3-1997

Family environment: Seen through the eyes of

adolescents labeled as emotionally disturbed

Jon KoengFollow this and additional works at:http://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses

This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Thesis/Dissertation Collections at RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contactritscholarworks@rit.edu.

Recommended Citation

Rochester, New York

Family Environment: Seen Through the Eyes

of Adolescents Labeled as Emotionally Disturbed

Master's Thesis

Submitted to the Faculty

Of the School Psychology Program

College of Liberal Arts

ROCHESTER INSTITUTE of TECHNOLOGY

By

Jon F. Koeng

In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of

Master of Science

August 3, 1997

Approved: _

(Committee Chair)

(Committee Member)

Dean:

-PERMISSION GRANTED

Title of thesis fClrol

\'1

E.nvlc"'r'".. e.""t: See..-. lhro ....1sh ""''" E¥u of.-Alo[e.f>c.e..-.f.:.., La..b...

!e.J

Q.Ij: G-...,f.,'o...fly

O,'sI-vclo ..J

I

J"'o,,",

K0U1

16

hereby grant permission to theWallace Memoria! L rary of the Rcchester Institute of Technology to reproduce my thesis in whole or in part. Any reproduction will not be for commercial use or profit.

Date:

S -

iLl· 97

Signature of Author:PERMISSION FROM AUTHOR REQUIRED

Title of thesis _

I prefer to be contacted each time a

request for reproduction is made. I can be reached at the following address:

PHONE: _

Date: _ Signature of Author: _

PERMISSION DENIED

TITLE OF THESIS _

I hereby deny permission to theWallace

Memorial Library of the Rochester Institute of Technology to reproduce my thesis in whole or in part.

Abstract

Emotionallydisturbed adolescent's perceptions oftheirfamilyenvironments were assessedusing

theFamilyEnvironmentScale(FES)(Moos, 1994). The sampleconsisted of27 students

classified asemotionallydisturbed according totheNew York State Part 200guidelinesfor

specialeducation, ranging in agefrom fourteento eighteen, andfallinginto five familytypes:

two-parentintactfamilies, stepfamilies, extendedfamilies, singleparentfamilies, and other. Results

indicatethatsubjectsdiffer significantly fromtheFES normative sample on six often variables

includingCohesion, Expression, Conflict, Achievement-Orientation, Intellectual-Cultural

Orientation, andMoral-Religious Orientation. Findingssuggestthatfamily relationships and

FamilyEnvironment: Seen Through the Eyes

ofAdolescents Labeled asEmotionallyDisturbed

Howdo adolescents and childrenlearnto copewithproblems? Isit upto thechild alone, to facethe day-to-daystressesthat accompanylife? Isittheresponsibilityofparentsto model

appropriatecopingstrategies andteach theirchildrento dealwith stressfullife situations? Is itthe

responsibilityofthe schoolto seethatit's studentsbecome psychologicallyandemotionally stable? Thesequestionsaredifficulttoanswer. Theratesofsubstanceabuse,juveniledelinquent

crimes, school drop-out, and suicideamongadolescents remain staggering,inspite of social servicesupport, teenoutreachprograms, andpsychologicalprogramsfocusingon child

psychotherapy.

Psychologists inthepublic schoolshave few alternativesforthe treatmentof emotional

problems experiencedbystudents: they canbereferred outto alocal agency, oriftheproblems are associated withschool,whichinmost casestheyare, the studentcan be labeledas Seriously EmotionallyDisturbed (SED)undertheguidelines oftheIndividualswithDisabilities Act(PL

101-476, IDEA). The Federalguidelinesforprovision ofservicesunderthe SED classification

are not specific with regardto particular diagnoses,but describe symptomsthat leaveroomfor

interpretation (Stein&Merrell, 1992). Intermsof more specificdiagnoses, thesesymptoms

could stemfrom disorders ranging from anxiety and mooddisordersto conduct andpersonality

disorders.

Studentswith emotionalandbehavioral problems who areidentified and receive special

education services undertheclassification ofSED aretypicallyprovidedbothchildfocused

encompass avarietyofindividual and grouptechniques designedto helpadolescents overcome

some personaldeficiency(Kazdin, 1987). Kazdin(1987) identifies severalformsoftherapyused

inthe treatmentof children who exhibit antisocialbehavior. One technique isindividual

psychotherapy, throughwhich acounselor mayprovideanadolescentwith corrective emotional

experiences andinsight into his/her behavior. Group psychotherapyfollows asimilarapproach,

butincludesapeergroupthroughwhichto processtheseexperiences. Behaviortherapyinvolves

retraining, modeling, andtheuse ofreinforcement, designed tomodifytheadolescent's behavior

and/or methods ofdealingwith situations. Social-skillstrainingis anotheralternativethat

involvesteachingandpracticing step-by-step approachesto avarietyofinterpersonalsituations.

Allofthese approachescenter onchangingtheadolescents'

ways ofthinking about, andreacting

to, themselves andtheir environments.

Kazdin (1987) identifiesdirect familytherapyastypicallyfocusing onthe communication,

relationships, and structurewithinthefamily. Forexample, parent management trainingisa

familyfocusedtherapythat teachesparentsto developprosocialbehaviors intheirchildren

through sociallearningtechniques. Itis importanttonotethatwhentheseapproachesare used, it

is typicallywithfamilies of adolescentslabeledwithdisruptivebehaviordisorders. However,

familytherapyisnotfrequentlycitedas aformoftreatmentforadolescentinternalizingdisorders

(Kazdin, 1991).

Numerousstudies haveevaluated theeffectivenessofpsychotherapywith children and

adolescents. In ameta-analysis, Casey andBerman(1985)foundsignificant outcome effectsfor

fourtherapeutic treatmentsused with problems such ashyperactivity/impulsivity, phobias, and

problemin SED. Theyalsofoundthatbehavioralbasedtreatmentshad higheroutcomeeffects

thannon-behavioraltreatments. Whenthefocusoftherapywas social adjustment, asinthecase

ofSED, outcome effectswereextremely limitedwhentheoutcome measures wereinareas of self

concept and achievement.

Hazelrigg, Cooper, andBorduin (1987)conductedareviewofstudies ontheeffectiveness

offamilytherapy withadolescentswithbehaviorproblems. Theyconcludedthat outcomes

following familytherapywereconsistently betterthan alternativetreatments, andthanno

treatment. Thereisaneedfor furtherresearch ontheeffectiveness offamilytherapywith children

and youthlabeledas SED.

Typically, adolescentslabeledSED, demonstrate aninabilitytoreactappropriatelyto

various stressful lifesituations, probably becausetheypossessinadequateorinefficientschemas

fordealingwiththe consequences ofdailyexperiences, (copingstrategies) developedduringtheir

earlylife. Therefore, aprimarygoal ofinterventionistobuildthese coping strategies. Child

focused psychotherapy has beenshowntobe inadequate fordealingwiththeseissues (Casey&

Berman, 1985);thusfamilybased interventionneedstobe implementedandevaluated. By

changingthefocus oftreatmentfromchildrentothefamily,theparents,who havemore control

overthe child'senvironment, arethusbetterableto effect real change, andbecomenotonlythe

focus oftreatment, but alsotheinstrumentsofchange.

The Problem

InaBiennial Evaluation Reporton Chapter 315: Programs for Childrenwith Serious

EmotionalDisturbance(CFDA84.237) for 1993 and 1994, thefollowing statistics were

Disturbed studentsleave schoolwithoutgraduating, withmostdroppingoutbytenthgrade. SED

students werefoundto havelowergradesthanany othergroupofstudents, andto failmore

courses andminimumcompetencyexaminationsthandoes anyothergroup ofdisabled students.

Twentypercent ofEmotionallyDisturbedstudentswerefoundtobearrestedatleastoncebefore

theyleave school, and35%were arrestedwithinafewyears ofleaving school. Thesenumbers

indicatethat thecurrent strategiesused inspecial educationsettingsforthe treatmentofSerious

EmotionalDisturbance,which arepredominantlychild-focused (Kazdin, 1987), are notnearlyas

effective astheycouldbe.

FamilyEffects onEmotional Development

Developmentofself-confidence, aneasy-goingdisposition,andthedisinclinationto use

avoidantcoping strategies, areallimportanttothepsychological developmentofthe child

(Holahan &Moos, 1986) andit is primarilythrough thefamilythat theseare learned.

Characteristicsofthefamilyenvironment playa major partintheunderstandingofanyindividuals

emotional well-being. Asarnow, Carlson, and Guthrie, (1987) suggestthat familyenvironment

hasasignificantinfluence ona child's social and emotional development becausechildren

interpretandcope with stimuliinwaysthathavebeenmodeledby familymembers. Thewaysin

which each member ofafamilyreactsto aninfinite numberofsituations, shapes and moldsthe

mindofa child.

McCubbin andMcCubbin (1988)identified a number of critical characteristicsinwhat

have beentermed "resilientfamilies,"

orfamilieswhotend toberesistantto disruption intheface

ofchange and adaptiveintheface of crisis. Theypoint outthat allfamilies face hardships,

are definedas resilient. Forexample, those thatcelebrate special events and maintain various

positivetraditionslikeholidays, are moreresilientinthefaceofdisruptionsto thefamilylife

cycle. Thosethatemphasizecommunication, and positiverelationshipsbetweenin-laws,relatives

and friendsare more resilient. Therefore, parental modelingofbehaviorsthatencouragepositive

self-image andbehavior, and effectivecoping strategies, takeon apreventativeroleinchild and

adolescent emotionaldisturbance.

McCubbin, Needle, andWilson (1985), identified "adaptive

resources,"

ortraits thatare

usedby familymembers, thefamilysystem, andthecommunitytomeet demandsplacedonthem,

suchasfamilydefinitionand meaning, aswell ascoping skills. Theydefinefamilydefinitionand

meaningashow "familiesand adolescentscognitively interprettheirsituation intermsofthe

demandstheyexperiencerelativeto theresources availableto meetthedemand. "(pg. 54)

"Copingisdefinedasthecognitive andbehavioralresponses oftheindividual(adolescent) orthe

familyto thedemands experienced."(pg. 54) Similarly, Olsen, Russell, andSprenkle(1979) view

themostimportantvariableinthemanagementoffamily stress asfamilycohesionand

adaptability. Theyalso identify familypride, parent-adolescent andmarital communicationskills,

andtheabilityto resolve conflicts ascriticalresourcesforadaption.

It isnot only importantthatparentsmodelthese skillsinpositive environments. Parents

must alsohelp challengethechild to developindependence, and togeneralize skillsto situations

outsidethefamily. Inastudy ofthe developmentof moralreasoning, WalkerandTaylor, (cited

inAllen, Hauser, Bell, &O'Connor, 1994)foundthathighlevelsof conflict and ofdisparityin

moral development betweenparents andchildrenwerepredictive of greaterdevelopmentalgains

contentionthattheco-occurrence ofchallenging and supportivebehaviorsbest predictfuture

development. Allen, et al. (1994) have indicatedthat the exhibition ofautonomy alongwith

relatednessinfamilyinteractions is stronglyrelatedtoboth egodevelopment andself-esteemin adolescents. Interms ofparents'

rolesintheirchildren'semotional development, this suggeststhat adolescentswho haveanopportunityto testtheirindependenceinasafe and supportive

environment arelikelyto havethegreatestsocial and emotionalgains. Similarly, Perosaand

Perosa(1993)found forthedevelopmentofa stableidentityandpositive copingstrategiesby

young adults, abalance betweenenmeshment and disengagement inthefamilyisnecessary. They

foundthatafamilyenvironmentinwhichmembers are ableto express(and resolve) conflictis

primaryto theseaspectsofdevelopment.

FamilyProblemsRelatedtoEmotional Disturbance

There are a numberoffamilycharacteristicsthathave beenassociated withthe

development of emotionalproblemsinchildren and adolescents(Fauber &Long, 1991). Thefirst isparental conflict or divorce. Inalongitudinal studyoffamiliesofdivorceandremarriage, Hetherington(1989) delineatedanumber of problems experiencedbychildren and adultsduring

thefirsttwoyears followingadivorce: Childand parent emotional distress; poor psychological

health andbehaviorproblems; disruptions infamily functioning; andproblems adjustingtonew

roles, relationships, andlifechanges associated withthealteredfamilysituation. Aftertwo years,

themajorityof parents and children werefoundtobeadaptingreasonablywellor showingsigns

aftertwo years, most girlstended tobefunctioningwell and hadpositiverelationshipswiththeir

custodialmother(Hetherington, 1989).

In anotherstudyofdivorcedfamilies, Shaw, Emery, andTuer(1993) foundthat

differencesinchild adjustment were more relatedto thedifferences in parentingstylesbetween

"to-be-divorced"

families and "always-married" families. Familiesthatweregoingtobe divorced,

with sons, showed significantlyless concernforchildren, higherlevels ofrejection, economic

stress,and parental conflictpriorto the divorcethanintact families. "Parentalconflictwasthe

onlyconsistent predictor of adjustmentacrosstime and

gender."

(pg. 130) Thus, divorce seems

tobe highlyrelatedto thedevelopmentof emotionalproblems,butthisis more relatedto the

parental conflictthat leadsto divorce,ratherthantothedivorce itself.

Fauber, Forehand, Thomas, and Wierson, (cited in Fauber andLong, 1991) statedthat

"most oftherelationbetweenmarital conflict andinternalizingand externalizingproblems of

young adolescenceisprimarily explainedthroughperturbations in parenting

practices."

(Pg. 816)

Theynoteparticularlyinconsistentmonitoring and discipline ordecreasedparental warmth and

involvement. FauberandLong (1991)identifiedparental psychopathology, parentaldrug and

alcohol abuse,familyviolence, child abuse andneglect, and poorbehaviormanagement skills as

significant factors inthedevelopment of social and emotional problems. Whenparentsdisplay

these problems,they are notonly creatinganunhealthy environment, theyalso aremodeling

inappropriate copingstrategies. Thus,familystressesleadnot onlyto emotional problems and

inappropriate coping strategies, butalsoto healthriskbehaviors,like smoking, alcohol anddrug

abuse(McCubbin, Needle, &Wilson, 1985). Whenthefamily failsto meettheneeds ofthe

Peers mayplace pressureontheadolescentto participatein inappropriate orhealthriskbehaviors

like smoking, drinking, andtheuse ofdrugs.

Parentsmust notonlymodel appropriate skills, butthose skills mustbeapparentto the

child oradolescent. Inastudyofdepressedand suicidal children, Asarnow,Carlson, andGuthrie

(1987) foundthat:

The strongest predictorsof suicidalbehaviorwerechildren'sperceptions oftheir

familyenvironment. Childrenwhothoughtofandattempted suicidetended to

perceivetheirfamilyenvironments as unsupportive andstressful, withpoor

control, high conflict, and alackofcohesiveness. (pg. 365)

This,when considered with other research onfamilycharacteristics, suggeststhat thesefactors

identifiedbyAsarnow, Carlson, and Guthrie (1987)shouldbe viewed as riskfactorsratherthan

causalfactors. It furthersuggeststhat earlyintervention, specificallywithfamilies, hasthehighest

potentialforpreventionoffurthersocial and emotional problemsinchildren and adolescents.

Goals ofthis Study

Thegoal ofthis studywasto investigatefamilyvariablesinchildren with Serious

EmotionalDisturbance, andtoidentifyparticularareas offamily functioningthatmight serve as

theprimary focusofintervention. Finally, it mayprovidedirection for planningfamilyoriented

formsoftreatmentandindividualtherapywithEmotionally Disturbedchildren.

Byeliciting

adolescents'

perspectives ontheirfamilyenvironment, a more accurate

understanding ofthefamilyfactorsinvolved inemotional disturbancemaybegained. The

perspectiveoftheparents, and ofprofessionals, maybe significantly different fromthat ofthe

EmotionallyDisturbed adolescents'

views oftheirfamilyenvironments areinvestigatedin

thecurrent study usingtheFamilyEnvironment Scale(FES)(Moos, 1994)and comparedtoits

normative sample. Thisscale assessesthreeaspects ofthefamily environment: Relationships,

personal growth, and system maintenance. The relationship dimensionassesses how involved

people areinthefamily, howtheyhelpeachother, andhowtheyexpressfeelingsto eachother.

Thepersonal growthdimensionassessesthewaysinwhichthefamilyencouragesor suppresses

areasof personal growthlikeindependence, intellectuality, or morality. The system maintenance

dimensionassessessuchthingsasorganization, and clarity ofexpectations, control and order.

Methods

Subjects

The sample was madeup of23 male students and4female students,ingrades 9to 12.

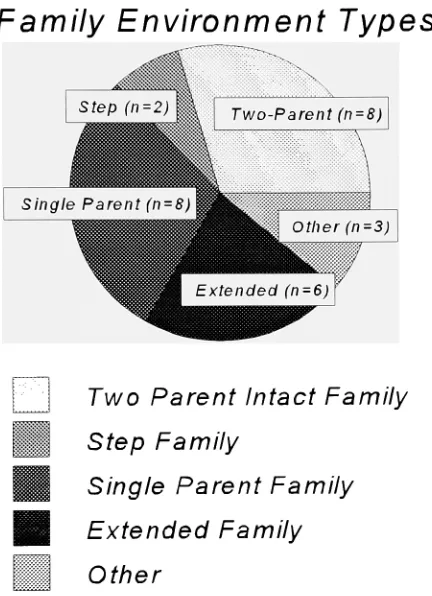

Subjects describedthemselvesasfallinginto one offivefamilyenvironmenttypes: two-parent

intactfamily, stepfamily, singleparentfamily, extendedfamily, orother. Figure 1 showsthe

break downoffamilyenvironmenttype.

Insert Figure 1 abouthere

All subjects werelabeledasEmotionally Disturbed, accordingtoPart 200 ofthe

RegulationsoftheCommissioner ofEducation, SubchapterP, ofthe State ofNew York(1993).

All subjects wereservedinthe 6: 1:1 (students: teachers: assistantteachers)program atthe

Monroe Board ofCooperativeEducational Services(BOCES) #1, AlternativeHighSchool. All

home schooldistrict. BOCES facilitiesare supportedby fundingfromaconsortium of area schooldistricts, andwere createdto provide special servicesthatindividual schooldistrictscould not provide. TheAlternative High Schoolis asection oftheMonroe BOCES#1 whichprimarily servesEmotionallyDisturbedadolescents.

Instrumentation

TheFamilyEnvironment Scale(FES)isone often Social Climate Scales developedby MoosandMoos (1994). The FES ismadeup ofninetystatements whicharemarkedas either

trueorfalsebytherespondent. The FES hasthreeforms: arealform(FormR), anIdeal Form (FormI), and anExpectations Form (Form E). Forthis study,Form Rwas usedbecauseit addresses

adolescents'

perceptionsoftheircurrentfamilyenvironment. Form RoftheFES has

beenusedbyclinicians, consultants, andprogramevaluatorsto "understand individuals'

perceptions oftheirconjugal and nuclearfamilies, ...formulateclinical casedescriptions, ...monitor

change, ...describeandcompare familyclimates, ...predictand measurethe outcomeoftreatment,

...focusonhow families adapt, ...andunderstandtheimpact ofthefamilyon children and adolescents"

(Moos, 1994, pg. 2). A copyoftheFES appearsin Appendix I.

The FES assessesthreedimensionsofthefamily environment: theRelationship dimension,

designedto"reflect meaningfuland conceptuallydistinctaspects offamily

environment."

(Moos,

1994, pg. 25) T-scores (Mean=

50, Standard Deviation=

10) are obtainedfor eachfactorofthe

FES, and canbe comparedto thenormative sample. NormativedatafortheFES was obtained

for 1,432 normal and 788distressed families, fromallareas ofthe country, andfromvarious

familytypes. ThetenfactorsoftheFES are describedin Table 1.

Insert Table 1 abouthere

The FES has beenshownto havegoodpsychometric properties. Table 2providesthe

reliability data forthe tensubscalesoftheFES. Edman, Cole, andHoward (1990) found good convergentvalidity betweentheFES and FamilyAdaptabilityand Cohesion Evaluation Scales-third edition(FACES-III) (Olsen, Portner, &Lavee, 1985). PerosaandPerosa(1990)

similarly foundthat cohesion asmeasuredbytheFES, was stronglyrelatedto cohesionas measuredbytheFamily Assessment Device(FAD) andthe StructuralFamilyInteraction Scale

(SFIS-R).

Insert Table 2abouthere

Procedure

Allsubjects completedthe 90item FES. Eachsubjectwasinstructedto write onthefront

cover oftheirresponsesheetwhattypeoffamilytheyconsiderthemselves a part of:two-parent

identifyinginformationwasobtained. SubjectscompletedtheFES in smallgroup settingsduring

freeperiods and electivetime, during schoolhours. Structuredclasstimewas notinterrupted.

All subjectswereinformedpriorto completingthe survey, ofthepurposeofthisstudy, ofthe

voluntarynatureofparticipation, andthatit wascompletelyanonymous.

Datawas analyzedbycomparingthe sample ofthe currentstudy, as onegroup,withthe

normative sample oftheFES, usingconfidenceintervalsdeveloped usingthe standarderror ofthe

mean(seenotein Table 3). Samplemeansthathad 95%confidenceintervalsthat didnot contain

thenormative mean of50wereconsideredtobe statistically different. Data forfamilytype

subgroupswasnot analyzeddueto small sample sizes.

Results

Thecurrentsample ofEmotionallyDisturbed adolescents perceivedtheirfamily

environmentsasbeingsignificantly different fromthenormativesample oftheFamily

Environment Scaleon severalfactors. Means and standard deviationsofthecurrent sample were

comparedto thoseoftheFES normative sampleusing confidenceintervals developedusingthe

standard error ofthemean. Table 3 provides adetailedlookatthemeansforeachfactor as rated

bythe total sample.

Insert Table 3 abouthere

AllthreefactorsoftheRelationshipDimensionweresignificantly different fromthe

normative sample. CohesionandExpressionwereboth significantly lowerthan thenorm, while

Intellectual-CulturalOrientation, andMoral-ReligiousEmphasis, weresignificantly lowerthan the

normativesample, whileIndependence andActive-Recreational Orientationwerenot significantly

different fromthenorm. Inthe System-MaintenanceDimension, neitherOrganizationnorControl

was significantly differentfromthenormative sample.

Discussion

Relationships

Emotionallydisturbed adolescentsperceivedtheirfamiliesasdifferent fromthenormative

families oftheFES on several dimensions. Someofthese atypical characteristicshave been

identified intheliterature as"risk

factors"

foremotionalproblems. Thisisparticularlytrue of

thosefactorsassessedintheRelationshipDimensionoftheFamilyEnvironment Scale(FES).

Subjectsofthecurrent study reportedsignificantly higherlevels ofconflict intheirfamilies.

Subjectsresponsesdo notindicatea specific areaofconflict, nordotheyindicate betweenwhich

familymembers conflicts occur. They simplyrevealthat thereare often conflictsbetweenfamily

members. Asshownbytheresearch ofAsarnow, Carlson, and Guthrie (1987), theperceptionof

highconflictbyteenswasamongseveralstrong indicators ofsuicidalbehavior. Also, studies of

divorce (Hetherington, 1989; Shaw, Emery, &Tuer, 1993) have shownthatvaryingtypesof

conflictamong families oftenleadto emotionalproblems among children. Alternatively, Perosa

andPerosa(1993)indicatedthat afamilyenvironment inwhichmemberscanexpress and resolve

conflict is primaryto thedevelopmentof adequate emotional development.

Olsen, Russell, & Sprenkle (1979) suggested cohesion andadaptability arethemost

importantvariablesincopingwithfamilystress. Subjectsresponsesinthe current studyindicate

conflictisviewed as astrongpromoter offamilystress, then theselowlevelsof cohesionindicate

that theseadolescents areinan environmentthatisnot abletocope wellwith, norresolve,

conflict. Further, thelow levelsof expression perceivedby subjects, suggeststhat theyalso have

limited abilityor opportunityto express conflictinahealthyway. Interms ofMcCubbin and

McCubbin's (1988)research, theselow levelsof expression suggestthat thesefamiliesdo not

emphasizecommunication, animportantcharacteristicof"resilient

families."

Overall, theperceptionsofthecurrent sampleofemotionally disturbedadolescents, in

termsoftherelationship dimensionsoftheFES, suggestthattheyseethemselvesasbeingin

familyenvironmentswith significantlevels ofconflict, and withlimited abilityto communicate or

resolvetheseconflicts. The elevatedlevelsofconflict, andthelow levels of expressionand

cohesion areconsistent across allfamilytypes, suggestingthatthesemay be animportantaspect

forvarioustreatment approaches.

Personal Growth

Subjects inthecurrent studyseetheirfamilyenvironments as havinglowachievement

orientation, low intellectual-cultural orientation, and lowmoral-religious emphasis. Looking

again atthework ofMcCubbinandMcCubbin(1988), parentsmodelingbehaviorsthatpromote

positive self-image, behavior, and effectivecoping strategiesisessentialto the buildingof

"resilientfamilies," andisessentialin preventing emotional problems amongchildren and

adolescents. Thelowachievement orientationreportedinthefamilyenvironmentsofthecurrent

studyindicatesthatfamilymembersexpectlittle ofthemselves, and/or expectlittleof other

members ofthefamily. Clearlytheseparentalbehaviorspromote somethingotherthana positive

The lower intellectual-cultural orientationreported inthesefamiliesindicates limited

interest inpolitical, intellectual, and cultural activities. Thisis consistent withalower

achievement orientation and suggeststhat thesefamilyenvironments place lessemphasis onthings

likeacademics, and education.

Thelowermoral-religious emphasis reportedinthesefamiliespresupposesthatfamily

members donot place an emphasis onmoralbehavior, orreligion. However, inmore general

termsitmay beviewedasan absenceofthemodelingof some specific positivebehaviors, and/or

theabsence of possible coping strategies.

TheindependencefactorontheFES, was ratedas consistent withthenormative sample.

This ratingsuggeststhat thisis an area of strengthforthesefamilies. However, it's"normality"

may in fact be problematic, dueto the absence of othersupportive aspectsofthefamily

environment. Allen, et al. (1994), foundthatadolescentswho havetheopportunitytotest their

independence in a safeand supportive environment will likelyhavethegreatest socialand

emotional gains. However, thepoorrelationshipsinthefamily environments ofemotionally

disturbed adolescents, suggestthatpromoting independence may bemore afunctionof

indifferenceonthepart ofotherfamilymembers,than afunctionofthepromotionof personal

growth.

Theperceptions ofthe emotionally disturbedadolescentsinthe current sampleindicate

thattheyviewtheirfamily environments asplacing littleemphasis on personalgrowth, and as

beinglessresilientto hardships,transitions, and crisisthanotherfamilies. These adolescentsview

theirfamilies asplacing littleemphasis on personalachievement andpromotingwhat mightbe

termedan"every-man-for-himself

'

SystemMaintenance

Thefactthatbothfactorsofthesystem maintenancedimensionwereperceived bysubjects

inthecurrent studyasbeingconsistent withthenorm sample oftheFES suggeststhat thereis

some consistencytothe organizationofthesefamilies, thatexpectations are clear, andthat there

iscontrol and orderinthefamilyenvironment. However, thisscaledoes notprovideinformation

ontheorientation, either positive ornegative, of system maintenance. Itispossiblethat thereis

organizationand control,butifthosefactorsare inflexibleorunfair, and enforced inan

unsupportive environment,thentheymay be creatingmore conflictthan stability.

Implications

Theresults ofthe currentstudy suggestthataprimary focusofinterventionwith SED

studentsshouldbe ontherelationshipswithintheirfamilies. Reducingconflict andbuilding

communication inorderto cope withconflictswhenthey do arise couldhelpto create a more

supportive environment foradolescents. Activities designedto promote cohesion amongfamily

members andto promote opportunitiesforexpressionmayhelpto resolveconflicts.

Teaching parentstomodel positive self-image and behavior may bea productive method

ofintervention. Aparent canbecomean instrument of changeby becominga model for hisor her

child, continuingto allowthemto beindependent, but modelingpositivecopingskills andusing

positive relationshipsto supportthemwhentheymake mistakes. Treatmentprofessionalsmay

takeadvantageof current systems of organization and controlto providestability, butmusttarget

themeans usedto maintainthis control andorganizationbyteaching parentshowto develop

positive focus intheirhousehold rules.

and not around. By helpingthefamiliesof adolescentswith emotional disturbancetofoster

positive relationshipsthatcopewith conflict, andthatchallengechildren togrowin asupportive

environment, onewill providetheadolescentwithgreater opportunitiesto make changes

themselves,thanbytryingto changethemdirectly.

Limitations

The sampleused inthecurrent studywas small;thus, it is difficultto makeinferences

regardingthefamilyenvironmentsofthevariousfamilytypes, andtheoverall population. The

sampleused wasalso madeup solelyofvolunteers, and maynotberepresentative of all

emotionally disturbed adolescents. Also, thenature ofthe SED disabilitymakestheresults less

reliable dueto the significantpossibilityofstudent exaggeration: eitherthroughawfulizing or

normalizing.

No cause and effect relationshipsmaybeestablishedbased onthecurrent study. Thatis,

it isnot clear whethertheperceptions ofthese adolescentswererelatedto familycharacteristics

thatledto theiremotional problems, or whethertheadolescents'

emotional problemsledthe

familytohavethereported characteristics. To answerthis question, itwould be necessaryto

studyfamilyenvironmentsbeforethestudent developed SEDproblems.

The findings ofthecurrent studyraise several questionsregardingpossibletreatment

approaches. Futurestudies mightinvestigatethe efficacyofknownfamilyinterventionsand/or

develop familyinterventionsthatcanproveeffectiveinadifficult area. Familyrelationships and

environments areimportant areasto target in treatment; however, methods mustbe devisedwhich

References

Allen,J. P.,Hauser, S. T., Bell, K. L.,& O'Connor, T. G. (1994). Longitudinal

assessmentofautonomyand relatednessinadolescent-family interactions as predictors of

adolescent ego developmentand self-esteem. Child Development. 65. 179-194.

Allen, J. P., Kuperminc, G., Philliber, S., &Herre, K. (1994). Programmaticprevention

ofadolescentproblembehaviors: Theroleofautonomy, relatedness, andvolunteerserviceinthe

teen outreach program. American JournalofCommunityPsychology. 22(5). 617-638.

Allen, J. P., Weissberg, R. P., &Hawkins, J. A. (1989). Therelationbetweenvaluesand

socialcompetencein earlyadolescence. Developmental Psychology. 25(3). 458-464.

Asarnow,J. R., Carlson, G. A., &Guthrie, D. (1987). Coping strategies, self-perceptions,

hopelessness, and perceivedfamilyenvironmentsin depressedand suicidal children. Journal of

ConsultingandClinical Psychology. 55, 361-366.

BiennialEvaluationReport, Chapter315, Programs for Childrenwith Serious Emotional

Disturbance, CFDA 84.237, (93-94).

Casey, R. J., &Berman, J. S. (1985). The outcome ofpsychotherapywith children.

PsychologicalBulletin. 98. 2, 388-400.

Cooke, B. D., Rossman, M. M., McCubbin,H. I., &Patterson, J. M. (1988). Examining

thedefinitionand assessment of social support: Aresourceforindividualsandfamilies. Family

Relations. 37. 211-216.

Edman, S. O., Cole, D. A.,&Howard, G. S. (1990). Convergentanddiscriminant

validityofFACES-III: Familyadaptabilityand cohesion. FamilyProcess. 29. 95-103.

thinkingabout parental conflict and its influence on children. Journal ofConsultingandClinical

Psychology. 60. 6, 909-912.

Fauber, R. L., &Long, N. (1991). Children in context: Therole ofthefamilyinchild

psychotherapy. Journal ofConsulting and Clinical Psychology. 59. 6, 813-820.

Fauber,R. L., &Long, N. (1992). Parentingin abroadercontext: A replytoEmery,

Fincham, and Cummings (1992). JournalofConsulting andClinical Psychology. 60. 6, 913-915.

Glyshaw, K, Cohen, L. H, & Towbes, L. C. (1989). Copingstrategies, and

psychological distress: Prospectiveanalyses ofearlyand middleadolescents. American Journal

ofCommunityPsychology. 17. 5, 607-623.

Hazelrigg, M. D., Cooper, H. M., &Borduin, C. M. (1987). Evaluatingtheeffectiveness

offamilytherapies: An integrativereview and analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 101. 3, 428-442.

Hetherington,E. M. (1989) Copingwithfamilytransitions: Winners, losers, and survivors.

Child Development. 60. 1-14.

Holahan, C. J., &Moos, R. H. (1986). Personality, coping, and familyresourcesin stress

resistence: A longitudinal analysis. Journal ofPersonalityand Social Psychology. 51. 2, 389-395.

Individuals withDisabilitiesAct, 20 U.S.C. Sec. 1400 (1990).

Kazdin, A. E. (1987). Treatmentof antisocialbehavior inchildren: Currentstatus and

future directions. PsychologicalBulletin. 102. 2, 187-203.

Kazdin, A. E. (1991). Effectivenessofpsychotherapywithchildren and adolescents.

Journal ofConsultingand Clinical Psychology. 59. 6, 785-798.

McCubbin, H. I., &McCubbin, M. A. (1988). Typologiesof resilientfamilies: Emerging

McCubbin, H. I., Needle, R. H, &Wilson,M. (1985). Adolescenthealthriskbehaviors:

Family stressand adolescent copingas critical factors. FamilyRelations. 34. 51-62.

Moos, R. H. (1994). The social climate scales: Auser's guide (2nd ed.). Palo Alto:

ConsultingPsychologistsPress, Inc.

Moos,R. H., &Moos, B. S. (1994). Familyenvironment scalemanual: Development.

applications, research(3rd ed.). Palo Alto: ConsultingPsychologistsPress, Inc.

Olsen, D., Portner, J., &Lavee, Y. (1985). FamilyAdaptability and Cohesion Evaluation

Scale (3rded.). St. Paul, Minnesota:Family Social Science.

Olson, D.,Russell, C, & Sprenkle, D. (1979). Circumplexmodel of marital andfamily

systemsII: Empirical studies and clinicalinterventions. In J. Vincent (Ed.), Advances infamily

intervention, assessment andtheory(pp 128-176). Greenwich, CT: JAI.

Perosa, L. M., &Perosa, S. L. (1990). Convergentand discriminantvalidity forfamily

self-report measures. Educationaland Psychological Measurement. 50. 855-868.

Perosa, S. L., &Perosa, L. M. (1993). Relationships among Minuchin's structuralfamily

model, identity achievement, and coping style. Journal ofCounselingPsychology. 40. 4, 479-489.

RegulationsoftheCommissionerofEducation, SubchapterP, Part200-Studentswith

Disablities(1993).

Shaw, D. S., Emery,R. E., & Tuer,M. D., (1993). Parentalfunctioning and children's

adjustmentin familiesofdivorce: Aprospective study. Journal ofAbnormal ChildPsychology.

21, 1, 119-134.

Stein, S., &Merrell, K. W. (1992). Differential perceptionsofmultidisciplinaryteam

29,320-331.

Vuchinich, S., Vuchinich, R. A., Hetherington, E. M.,& Clingempeel, W. G. (1991).

Parent-childinteraction and genderdifferencesin early

adolescents'

adaptionto step families.

Table 1.

FamilyEnvironment Scale Factorsand Descriptions

Factor Description

Relationship Dimension

Cohesion

Expressiveness

Conflict

thedegreeofcommitment, help, and supportfamilymembers

provideforone another

theextentto whichfamilymembers are encouragedto expresstheir

feelingdirectly

the amount ofopenlyexpressedanger and conflictamongfamily

members

Personal Growth Dimension

Independence theextentto whichfamilymembersare assertive, are selfsufficient,

and maketheirown decisions

Achievement-Orientation howmuch activities (suchas school orwork) arecastinto an

achievement-oriented orcompetitiveframework

Intellectual-CulturalOr. thelevel ofinterest inpolitical, intellectual, and cultural activities

Active RecreationalOr. the amountof participationinsocial and recreational activities

Moral-ReligiousEmphasis theemphasison ethicaland religiousissues and values

SystemMaintenance Dimension

Organization the degreeofimportanceof clear organization and structurein

Control howmuch set rules and procedures are usedto runfamilylife

Note. FromMoos, R. H., &Moos, B. S. (1994). Family environment scale manual:

Table 2.

FamilyEnvironment Scale-FormR: Internal Consistencies. Corrected AverageItem-Subscale

Correlations, and2-Monthand4 Month Test-Retest Reliabilities.

Corrected

Average

Item 2-Month 4-Month

Internal Subscale Test-Retest Test-Retest

Consistency Correlations Reliability Reliability

Subscale n=l,067 n=l,067 n=47 n=35

Cohesion .78 44 .86 .72

Expressiveness .69 .34 .73 .70

Conflict .75 43 .85 .66

Independence .61 .27 .68 .54

Achievement Orientation .64 .32 .74 .66

Intel.-Cult. Orientation .78 44 .82 .86

Active-Rec. Orientation .67 .33 .77 .83

Moral-Rel. Emphasis .78 43 .80 .91

Organization .76 42 .76 .73

Control .67 .34 .77 .78

Note. FromMoos, R. H, &Moos, B. S. (1994). Familvenvironment scale manual:

Table 3.

Mean Sample T-score. StandardDeviations, andConfidence Intervals, for Each factor oftheFES

(n=27)

Factor T-Score SD 95% ConfidenceInterval

Cohesion 37.59 17.95 33.82 <p.<41.36

Expression 45.37 12.1 41.6<|a<49.14

Conflict 56.7 12.63 52.93 <|i<60.48

Independence 49.15 12.39 45.38 <|a<52.92

Achievement Orientation 46.04 10.27 42.27 <[i<49.81

Intel.-Cult. Orientation 37.93 13.06 34.15<n<41.7

Active-Rec. Orientation 49.81 11.09 46.04<u.< 53.59

Moral-Rel. Emphasis 43.41 10.68 39.64 <|_i<47.18

Organization 47.26 9.70 43.49<p. <51.03

Control 49 11.49 45.23 <p< 52.77

Note. Confidence intervals determined b y Standard ErroroftheMeansforsampleusin;the

followingformula, appropriateforwhenaisknown : X

-zcv(aJ <\x< X+zcv(aj where ax

a//n , a

=

10, and zcv= 1.96 Confidence intervalsnot

encompassingthenullvalue of50

Figure 1. Family environmenttypesas describedbysubjectsinthecurrent study.

Family

Environment Types_____T~^x

_aiSK4i;Si

StepJn~2> m, Two-Parent(n=

8)

Two Parent Intact Family

Step Family