Comprehensive textbook of psychotherapy: Theory and practice (2 ed.) (pp. 106-120). New York: Oxford University Press. © 2015 Oxford University Press. This is

an author final version and may not exactly replicate the published version. It is not the copy of record.

Humanistic-Experiential Psychotherapy in Practice: Emotion-Focused Therapy Robert Elliott

University of Strathclyde Leslie S. Greenberg

York University

Authors’ Note. Robert Elliott, Ph.D., School of Psychological Sciences and Health, University of Strathclyde. Leslie Greenberg, Ph.D., Department of Psychology, York University, North York, Toronto, Canada. For correspondence regarding this chapter please contact Robert Elliott, Ph.D., School of Psychological Sciences and Health, University of Strathclyde, 40 George Street, Glasgow G1 1QE, Scotland, UK or via email at

robert.elliott@strath.ac.uk.

Summary

In this chapter, we provide an overview of emotion-focused therapy (EFT), a contemporary humanistic psychotherapy that integrates person-centered, gestalt, and

existential approaches. After sketching its history and main theoretical concepts, we outline a set of emotion change principles. These guide an emotional deepening process in which therapists help clients move from undifferentiated distress to secondary reactive emotions to primary maladaptive emotions to core pain and thence to primary adaptive emotions and emotional transformation. To do this, the therapist responds to key markers offered by clients, proposing appropriate therapeutic tasks such as unfolding problematic reaction points or two-chair work for internal conflicts. In addition, we briefly summarize the relevant outcome data, review the EFT case formulation process, lay out treatment principles, consider its

application to diverse client populations, and provide a brief case example.

Keywords: humanistic-experiential psychotherapy, emotion-focused therapy, emotion, therapeutic tasks, social anxiety

Historical Background and Evolution of the Approach

Emotion-Focused Therapy is an integrative, humanistic, empirically-supported treatment based on a program of psychotherapy research going back into the 1970’s (Elliott, Watson, Greenberg, Timulak & Freire, 2013; Rice & Greenberg, 1984). Drawing together Person-Centered, Gestalt, and existential therapy traditions, EFT provides a distinctive perspective on emotion as a source of meaning, direction, and growth.

Emotion-Focused Therapy (EFT), has come to be applied to the individual therapy (Greenberg & Paivio, 1998) and some versions of the couples therapy (Greenberg & Goldman, 2008).

Like other humanistic therapies, EFT is based on a set of core values (Elliott, Watson, Goldman & Greenberg, 2004), which it strives to foster; these values have been updated in light of contemporary emotion theory (Greenberg, 2002) and dialectical constructivism (Elliott & Greenberg, 1997):

• Experiencing is central and emerges out of an evolving, dynamic synthesis of multiple emotion processes (emotion responses and schemes).

• At the same time, human beings are fundamentally social and have strong attachment needs, which require human contact in the form of presence and authenticity.

• Agency or self-determination is an evolutionarily adaptive motivation to explore and master situations.

• Pluralism/diversity within and between persons is unconditionally accepted, validated and even celebrated, leading to relationships based on equality and empowerment.

• A sense of wholeness is adaptive and is mediated by emotion. Instead of an over-arching, singular executive self, however, wholeness stems from friendly contact among disparate aspects.

• Growth is supported by innate curiosity and adaptive emotion processes, and tends toward increasing differentiation and adaptive flexibility.

EFT originated as an individual treatment for depression and a couples intervention for relationship problems, organized around a set of emotion theory concepts, treatment principles, and in-session tasks. Since then, it has continued to evolve, driven by work with clients suffering first from complex trauma and abuse (Paivio & Pascual-Leone, 2010) and more recently with anxiety (Elliott, 2013) and eating difficulties (Dolhanty & Greenberg, 2007). Application to these new client populations has led to the development of new therapeutic tasks, which has in turn led to more general understandings of core change processes and the process of emotional deepening and change (Pascual-Leone & Greenberg, 2007). At the same time, organized EFT training has been developed in many parts of the world, which has also helped bring greater clarity to its theory and practice. Moreover, treatment manuals have been written addressing EFT overall (Elliott, Watson, Goldman & Greenberg, 2004), as well as how to treat depression (Greenberg & Watson, 2005), and address complex trauma (Paivio & Pascual-Leone, 2010) with EFT.

Principles of Change and Case Conceptualization

We will describe two sets of guiding principles of change in EFT. First, we will present the original set of general treatment principles that provided the foundation from which EFT developed; after that, we will lay out a more specific set of emotional change principles.

General EFT Practice Principles

The actual practice of EFT is based on a set of six general practice principles. These include principles focused on the relationship and those that emphasize task facilitation.

what they want to work on in the session, their emotion or what is most poignant, what it is like to be the client more generally, and what is unclear or emerging.

2. Therapeutic bond. Following Rogers (1957) and consistent with current assessments of the research literature (e.g., Norcross, 2011), the therapeutic relationship is seen as a key curative element. For this reason, the therapist seeks to develop a strong

therapeutic bond with the client, characterized by communicating three intertwined relational elements: understanding/empathy, acceptance/prizing and presence/genuineness. Empathy or understanding of client emotions and meanings can be expressed in many ways, including reflection and exploration responses and appropriate tone of voice and facial expression. Acceptance is the general "baseline" attitude of consistent, genuine, noncritical interest and tolerance for all aspects of the client, while prizing goes beyond acceptance to the immediate, active sense of caring for, affirming, and appreciating the client as a fellow human being, especially at moments of client vulnerability (Greenberg et al., 1993). The therapist's genuine presence (Geller & Greenberg 2002) to the client is also essential, and includes being in emotional contact with the client, being authentic (congruent, whole), and being

appropriately transparent or open in the relationship (Lietaer, 1993).

3. Task collaboration. An effective therapeutic relationship also entails involvement by both client and therapist in developing overall treatment goals and immediate within-session tasks and therapeutic activities (Bordin, 1979), aiming to engage the client as an active participant in therapy. In general, the therapist accepts the goals and tasks presented by the client, working actively with the client to explore the emotional processes involved in them (Greenberg, 2002). In addition, the therapist offers the client information about emotion and the therapy process to help the client develop a general understanding of the importance of working with emotions and to provide rationales for specific therapeutic activities, such as two-chair work.

4. Emotional deepening through work on key therapeutic tasks. In EFT, therapists begin by working with clients to develop clear treatment foci and goals, then track clients’ current tasks within each session, particularly those tasks associated with their treatment goals. For example, given a choice of what to reflect, therapists emphasize experiences associated with treatment foci; in addition, therapists gently persist in offering clients opportunities to stay with key therapeutic tasks, or to come back to them when distractions, sidetracks, or blocks occur. In doing so, therapists are partly guided by their knowledge of the natural resolution sequence of particular tasks, and so gently offer clients opportunities to move to the next stage of the work (for example, giving the critic in two-chair dialogue an opportunity to soften), if they are ready to do so. It is also important for the therapist to be flexible and to follow the client when they switch to an emerging task that is more alive or central for them.

5. Self-development. EFT therapists emphasize the importance of clients’ freedom to choose their actions, in therapy as well as outside therapy. Beyond their general stance of treating clients as experts on themselves, the therapist supports the client's potential and motivation for self-determination, mature interdependence with others, mastery of difficulties, and self-development, including the development of personal power (Timulak & Elliott, 2003). For example, the therapist might hear and reflect the assertive anger implicit in a depressed client's mood, or they might offer a hesitant client the choice not to go into exploration of a painful issue. We have found that clients are more willing to take risks in therapy when they feel they have the freedom to make therapy as safe they need it to be.

mindful receptive focus on immediate perceptual experiences or specific memories; careful attention to immediate bodily experience and felt meaning; awareness and symbolization of immediate emotional experience; expressing wants or needs or the actions that go with them; reflecting on the meaning, value, or understanding of experience. A common sequence is for clients to start by attending to external events, then move back and forth between reflection on meaning and accessing and expressing emotions (Angus & Greenberg, 2011). This general principle will next be elaborated in the form of a further set of emotion change principles.

Emotion Change Principles

From the EFT perspective, change occurs by helping people make sense of their emotions through awareness, expression, regulation, reflection, and transformation

(Greenberg, 2011), all in the context of the more general EFT change principles, including a therapeutic relationship characterized by a therapist who is actively engaged, emotionally present, and empathically attuned, and offers positive regard and unconditional acceptance.

1. Awareness. Increasing awareness of emotion and its various aspects is the most fundamental overall goal of treatment and involves accessing and becoming aware of one’s emotions. Once people know what they feel they reconnect to their needs and are motivated to meet them. Emotional awareness involves accepting emotions rather than avoiding them; it also involves feeling the feeling in awareness rather than simply thinking about it. Lieberman et al. (2007) have shown that naming a feeling in words helps decrease amygdala arousal. EFT therapists thus work with clients to help them access, approach, tolerate, accept, differentiate, and symbolize their emotions.

2. Expression. Expressing emotion in therapy does not involve the venting of secondary emotion but rather overcoming avoidance to strongly experience and expressing previously constricted primary emotions (Greenberg & Safran, 1987; Greenberg, 2002). Doing this can also help clarify and focus attention on central concerns and needs, which in turn promotes pursuit of important goals. The role of emotional arousal and the degree to which this can be useful in therapy and in life depends on what emotion is expressed, about what issue, how it is expressed, by whom, to whom, when and under what conditions, and in what way the emotional expression leads to other experiences of affect and meaning.

Greenberg, Auzra and Hermann (2007) found that it was the manner of processing aroused emotions, rather than arousal alone that distinguished good from poor outcome cases. They defined productive emotional expression as occurring when a client was aware of emotion in a “contactful” way.

stress. Promoting clients’ abilities to receive and be compassionate to their emerging painful emotional experience is a key step towards tolerating emotion and self-soothing. Soothing of emotion can be provided by individuals themselves, reflexively or from another person, including the therapist, in the form of empathic attunement, acceptance, and validation.

4. Reflection. In addition, promoting self-reflection on emotional experience helps people make narrative sense of their experience and promotes its assimilation into their ongoing self-narratives (Angus & Greenberg, 2012). Reflection helps make sense of aroused experience. In this process, feelings, needs, self-experience, thoughts, and aims are all clarified and organized into coherent narratives, and different parts of the self and their relationships are identified. The result of this reflection based on aroused emotion is deep experiential self-knowledge. Situations are understood in new ways and experiences are reframed, which leads to new views of self, others, and world.

5. Transformation. Probably the most important way of dealing with emotion in therapy involves the transformation of emotion by emotion (Greenberg, 2002, 2011). In EFT an important goal is to arrive at maladaptive emotion in order to make it accessible to

transformation. The co-activation of the more adaptive emotion and the maladaptive emotion, in response to the same eliciting cue, helps transform the maladaptive emotion. Change in previously avoided primary maladaptive emotions such as core shame or fear of

abandonment is brought about by the activation of an incompatible, more adaptive,

experience such as empowering anger and pride or self-compassion, which undoes the old response. This involves more than simply feeling or facing the feeling in order to diminish it. Rather, for example, the withdrawal motivated by a primary maladaptive emotion such as fear and shame is transformed by activating the approach tendencies that stem from anger or contact/comfort seeking. A key method for accessing new more adaptive emotion involves focusing on what is needed (Greenberg, 2002, 2010). New emotional states enable people to challenge the validity of perceptions of self/others connected to maladaptive emotion, weakening its hold on them. These states provide new, corrective emotional experience with the therapist, which undo old patterns of maladaptive interpersonal experience (Greenberg & Elliott, 2012). Thus, experiences that provide interpersonal soothing, disconfirm pathogenic beliefs or offer new success experience can correct patterns set down in earlier times. For example, an experience in which a client faces shame in a therapeutic context and

experiences acceptance, rather than the expected disgust or denigration, has the power to change the feeling of shame.

Case Conceptualization

In keeping with the intervention and emotion change principles described above, EFT case conceptualization focuses more on process than content and relies primarily on a set of emotion theory concepts, such as emotion schemes and emotion response types.

Emotion schemes. In EFT emotions are conceptualized as organizing networks of interrelated experiences known as emotion schemes. These networks consist of many elements, among them: a) situational-perceptual experiences, including affectively-tinged memories and immediate appraisals (e.g., noticing that one is alone and isolated from others and remembering oneself as a lonely child); b) bodily sensations and expressions (e.g., a sinking feeling in the chest accompanied by quivering lips); c) implicit verbal-symbolic representations including stock phrases and self-labels (e.g., “Unlovable”); and d) motivation-behavioral elements including needs and action tendencies (e.g., needing another person’s affirming presence, while at the same time withdrawing from contact). When activated and attended to, this produces a conscious emotional experience, which can be considered as a fifth emotional element (e.g., an old familiar sadness at feeling abandoned and unloved).

to the current situation that would help us take appropriate action. For example, if a person is being violated by someone, anger is an adaptive response because it helps the person to take assertive action to end the violation; sadness on the other hand indicates loss and motivates the need for connection. Primary maladaptive emotion responses are also initial, direct reactions to situations; however, they involve overlearned responses based on previous, often traumatic, experiences. For example, a client with borderline processes may have learned when they were growing up that caring offered by others was usually followed by physical or sexual abuse. As a result, the therapist’s empathy and caring are responded to with anger, as a potential violation of boundaries. With secondary reactive emotional responses, the person reacts to their initial primary emotional response (which can be either adaptive or

maladaptive), so that it is replaced with a secondary emotion. For example, a client who encounters danger and begins to feel fear may become angry about the fear, even when angry behaviour increases the danger. Finally, instrumental emotion responses are strategic displays of an emotion for their intended effect on others, such as getting others to pay attention to or to approve of the person. Common examples include "crocodile tears" (instrumental sadness), "crying wolf" (instrumental fear), and intimidation displays (instrumental anger).

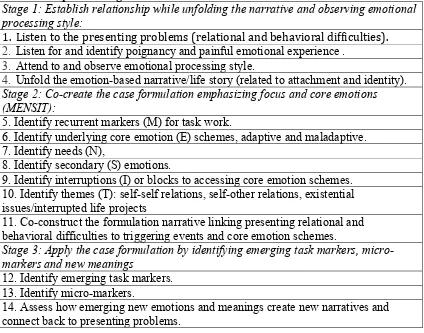

Case conceptualization process. In order to promote a focus during brief treatment, EFT has developed a context-sensitive approach to conceptualizing clients, referred to in EFT as case formulation (see Goldman & Greenberg, 2014; Greenberg & Goldman 2007). In this approach, however, process is privileged over content, and process diagnosis is privileged over person diagnosis. In other words, EFT case formulation focuses primarily on developing a shared understanding of the client’s core painful emotion, key in-session presenting issues, and recurring task markers, and only secondarily on their character structure or patterns of relating to self and others. In a process-oriented approach to treatment, case formulation is an ongoing process, as sensitive to the moment and the in-session context as it is to developing a more global understanding of the person.

Case formulation is helpful in facilitating the development of a treatment focus and in fitting the therapeutic task to the client’s goals, thereby aiding in the establishment of a productive working alliance. In our view, formulations are always co-constructions that emerge from the relationship, rather than being formed by the therapist alone. The

establishment of a problem definition is tantamount to the agreement on treatment goals in the formation of the initial alliance (Bordin, 1994). Table 1 depicts the steps that have been identified to guide clinicians in the development of case formulations (Greenberg &

Goldman, 2014).

To aid in the formulation of momentary states, therapists also distinguish between primary, secondary, and instrumental emotional responses (Greenberg & Safran, 1987; Greenberg et al, 1993). In order to formulate successfully, EFT therapists also develop a pain compass, which acts as an emotional tracking device for following their clients’ experience (Greenberg & Watson, 2006). Therapists focus on the most painful aspects of clients’ experience and identify clients’ chronic enduring pain; this leads to identifying core maladaptive emotion schemes, which become the center of the formulation. Painful events provide clues as to the source of important core maladaptive emotion schemes that clients may have formed about themselves and others. For example, in working with a client presenting with social anxiety, the therapist and client will identify markers (M in Table 1) such as self-criticism and unresolved experiences of abuse and may come to share the understanding that underlying the secondary hopelessness and anxiety (S) is a core

maladaptive emotion scheme (E) of shame. This core shame points to the client’s need (N) for validation. . In response, the therapist offers the validation needed to counter the painful sense of shame; however, the client initially interrupts (I) the process through in-session states of numbing . The theme (T) of the therapy focuses on lack of self worth.

Research on the Efficacy and Effectiveness of Emotion-Focused Therapy EFT is an empirically-supported psychotherapy. It is the product of extensive psychotherapy process-outcome research, that has been reviewed in several publications (Elliott, Greenberg & Lietaer, 2004; Elliott, Watson, Greenberg, Timulak, & Freire, 2013; Greenberg et al., 1994). Rice and Greenberg (1984) first adapted the method of task analysis from research on cognitive problem solving and used it to develop and test micro-process models of the steps clients go through to resolve key therapeutic tasks such as internal conflicts or puzzling personal reactions. Similarly, Elliott’s research on therapist response modes (Elliott, Hill, Stiles, Friedlander, Mahrer, & Margison, 1987) and client within-session helpful experiences (e.g., Elliott, James, Reimschuessel, Cislo, & Sack, 1985) provided the descriptive basis for key elements of EFT. For the past twenty years, however, much of the research on EFT has been on outcome, complemented by process-outcome prediction studies, qualitative research, and case studies (reviewed in Elliott et al., 2013).

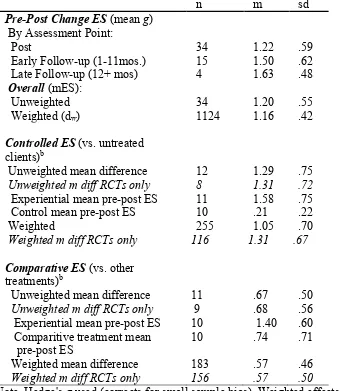

The larger meta-analytic data set used by Elliott et al (2013) includes data from almost 200 outcome studies on humanistic-experiential therapies. This overall data set shows large pre-post client gains and controlled effects, along with equivalent outcomes for

humanistic-experiential therapies and other therapies, including CBT. Table 2 summarizes 34 studies on EFT taken from this data set. The uncontrolled pre-post effects are even larger than for the larger data set (weighted ES = 1.16; n = 1124). Twelve studies compared EFT to no-treatment or waiting-list controls, for a very large weighted, controlled ES of 1.05 (n = 255). Finally, in eleven studies comparing EFT to some other non-humanistic therapy, a medium weighted, comparative ES of .57 (n = 183) was found, favoring EFT. However, a limitation of the existing research is that it is predominated by research carried out by advocates of EFT.

Assessment and Selection of Clients Assessment

particularly compatible with EFT include the Personal Questionnaire (Elliott et al., 2015), an individualized, weekly outcome measure consisting of ten problems identified by the client for work in therapy, used to identify presenting problems and potential therapy tasks and to monitor outcome; the Working Alliance Inventory (Horvath & Greenberg, 1989; see revised 12-item short form: Hatcher & Gillaspie, 2006), a brief client measure of the therapeutic relationship as it is conceptualized in EFT; the Client Task Specific Change – Revised Form (Watson, Greenberg, Rice & Gordon, 1997), a client post-session impact rating scale; the Resolution Scale (Singh, 1994), a client outcome measure assessing perceived resolution of EFT tasks; and the Self-Relationship Scale (Faur & Elliott, 2007), a measure of client-perceived treatment of self (e.g., self-attack, self-control).

Selection of Clients

As noted in the earlier discussion of case formulation, assessment in EFT is

collaborative and emphasizes the emotion processes implicit in client presenting problems. EFT has now been applied to a wide range of clients, including those presenting with depression (Greenberg & Watson, 2005), couples difficulties (Greenberg & Johnson, 1988), attachment injuries and unresolved relationships (Paivio & Greenberg, 1995), complex trauma (Paivio & Pascual-Leone, 2010), anxiety (Elliott, 2013; Shahar, 2013), and eating difficulties (Dolhanty & Greenberg, 2007).

Treatment

In EFT, what the therapist actually does can be described at two levels: therapist responses modes and EFT tasks and markers.

Therapist Response Modes

Some of the key therapist experiential response modes used in EFT (Elliott et al, 2004) include:

1. Empathic understanding. Consistent with its person-centred heritage, the foundation of therapist responding in EFT is empathic reflection and following, using responses that try to communicate understanding of the client's message, including simple reflections and brief acknowledgements (“Uh-Huh's”). For example, when Carol, one of our clients with severe social anxiety said,

C: This is what I’ve never had, is the feeling of being OK. her therapist reflected with:

T: To be seen as OK, to be regarded as good enough.

2. Empathic exploration responses. The most characteristic EFT response, however, is empathic exploration (Elliott et al., 2004). These responses both communicate understanding and help clients move toward what is difficult or painful to say. Empathic exploration responses take many different forms, including evocative reflections (which use imagery or metaphor), exploratory questions (“What comes up inside when you hear that?”), “fit” questions (“Does that fit your experience?"), and empathic conjectures, or guesses about what the client is experiencing but has not yet said out loud. Here is a brief excerpt from the same socially anxious client exploring her sense of being left out of ordinary social life:

T: So what happens when you feel that wall against you? [exploratory question] C: I just want to go, to bed [crying], because I can’t work it out now, I don’t know, where to take it, I don’t know where to go.

T: So when you get faced with that kind of being pushed out and judged, you just are paralyzed [evocative reflection]

C: I don’t know where to go

T: The feeling is really, really painful? [empathic conjecture]

T: Because you really want to belong [empathic conjecture]

3. Process guiding. In support of the different therapeutic tasks in EFT, therapists also offer various process guiding responses. These include process suggestions, offering opportunities for clients to engage in particular in-session activities, such as speaking to an imagined self-aspect in the other chair. EFT therapists also sometimes provide experiential teaching, for example giving orienting information about the nature of emotional experience, or they offer gentle support, orienting suggestions or encouragement for working on the task at hand (task structuring responses). At other times, they may tentatively offer an

experiential formulation of a process or self-aspect for the client ("unfinished business," "critic") in the service of work on a therapeutic task. Finally, at the end of the session EFT therapists may offer awareness homework, encouraging them to continue work from the session on their own. Many of these are illustrated in this segment from session four with Carol as she began to work with the process by which she makes herself afraid of other people:

T: So come over here and be them [the other students in your counselling skills practice group]. [process suggestion]

C: Ohh [C gets up and moves to other chair]

T: [With enthusiasm:] This is this chair stuff we do! [experiential teaching] C: Oh dear! Is it?

T: So be them as you are afraid they are responding to you. [process suggestion] C: Be them?

T: She’s just lost you, right. She just lost you, right? [task structuring]

C: Oh, OK. What’s up with you? Who do you think you are? You’re not a tutor. T: “You have no right to say this to us.” (C: No) Say that to her: “You have no right to tell us.” [process suggestion]

C: You don’t have any right to tell us to do anything.

4. Experiential presence. In EFT, therapist empathic attunement, prizing,

genuineness, and collaborativeness are largely communicated through the therapist's genuine presence or manner of being with the client. There is a distinctive, easily-recognized EFT style: For example, when offering process guiding, the therapist typically uses a gentle, prizing voice (and sometimes humor), while empathic exploration responses often have a tentative, pondering quality. Presence is also indicated by direct eye contact at moments of connection between client and therapist. Therapist process (in session) and personal (more general) disclosures are really explicit forms of experiential presence, in that they are

commonly used to communicate relationship attitudes. For example, the therapist began the first session of Carol’s therapy with a process disclosure of his own anxiety:

T:...I don’t know how it is for you, but I’m a bit nervous, because we are just starting out.

Markers and Tasks

A defining feature of the EFT approach is that intervention is marker guided.

Research has demonstrated that clients enter specific problematic emotional processing states that are identifiable by in-session statements and behaviors that mark underlying affective problems and that these afford opportunities for particular types of effective intervention (Elliott et al 2004; Greenberg, Rice & Elliott, 1993; Rice & Greenberg, 1984;). Client markers indicate not only the type of intervention to use but also the client’s current

readiness to work on this problem. EFT therapists are trained to identify markers of different types of emotional processing problems and to intervene in specific ways that best suit these problems.

specified. Thus, models of the actual process of change act as maps to guide the therapist intervention. Many task markers and their accompanying interventions have now been identified and described; here are some of the most common ones (Elliott et al., 2004; Greenberg et al., 1993).

Problematic reactions expressed through puzzlement about emotional or behavioral responses to particular situations. For example a client saying “on the way to therapy I saw a little puppy dog with long droopy ears and I suddenly felt so sad and I don’t know why.” Problematic reactions are opportunities for a process of systematic evocative unfolding. This form of intervention involves vivid evocation of experience to promote re-experiencing the situation and the reaction in order to establish the connections between the situation, thoughts, and emotional reactions, thus helping the client to finally arrive at the implicit meaning of the situation that makes sense of the reaction. Resolution involves a new view of self-functioning.

An unclear felt sense occurs when the person is confused about something or unable to get a clear sense of their experience (“I just have this feeling but I just can’t put my finger on it”). This marker calls for focusing (Gendlin, 1996) in which the therapist guides clients to approach the embodied aspects of their experience with attention and curiosity in order to experience them and to put words to their implicit, often subtle feelings. A resolution involves the creation of new meaning along with a release of bodily tension.

Conflict splits involve one aspect of the self being critical, coercive, or interruptive towards another aspect. For example, a woman quickly becomes hopeless and defeated but also angry at the prospect of being seen as a failure by her sisters: “I feel inferior to them: It’s like I’ve failed and I’m not as good as them.” Self critical conflict splits like this offer an opportunity for two-chair work, in which two parts of the self are put into live contact with each other. Thoughts, feelings, and needs within each part of the self are explored and communicated in a real dialogue to achieve a softening of the critical voice. Resolution involves an integration of the two sides. Self-interruptive conflict splits arise when one part of the self interrupts or constricts emotional experience and expression: “I can feel the tears coming up but I just tighten and suck them back in, no way am I going to cry.” In this case, the therapist helps the client to enact and make explicit how the interrupting part of the self does this, for example by physical act (choking or shutting down the voice), metaphorically (caging), or verbally (“shut up, don’t feel, be quiet, you can’t survive this”), so that they can experience themselves as an agent in the process of shutting down and then can react to and challenge the interruptive part of the self and express the previously blocked experience.

An unfinished business marker involves the statement of a lingering unresolved feeling toward a significant other, such as the following said in a highly involved manner: “My father, he was just never there for me. I have never forgiven him. Deep down inside I think maybe I’m grieving but then I just tell myself, ‘what’s the point, there’s no use dwelling on the past’.” Unfinished business toward a significant other calls for an empty-chair intervention. The client imagines the other present in the other empty-chair in order to activate their internal view of a significant other and then to experience and explore their emotional reactions to the other and make sense of them. Shifts in views of both the other and self occur. Resolution involves holding the other accountable or understanding or forgiving the other.

different emotion. In this task, the therapist first helps the client deepen their sense of anguish so that they can access their core existential pain and express the unmet need associated with it. Then, the therapist offers a two-chair process to the client in which they enact providing what is needed (e.g., validation, support, protection) to themselves. This can be done either directly or with the needy part symbolized as a child or close friend experiencing the same things that the client is. The comforting aspect is represented either as a strong, nurturing aspect of self or as an idealized parental figure.

A number of additional markers and interventions such as alliance rupture and repair, confusion and clearing a space, high distress and meaning making, and more, have been added to the original six markers and tasks identified above (see Elliott et al. 2004). In addition, a new set of narrative markers and interventions combining working with emotion and narrative, such as same old story, empty story, untold story, and healing story have been specified (Angus & Greenberg, 2011).

Diversity

EFT is routinely offered to a diverse range of clients of all persuasions, origins, and abilities. EFT training and practice are carried out successfully, with appropriate cultural sensitivity, in most parts of the world. While EFT might seem to most naturally fit clients from individualistic Western cultures who enter therapy with emotion processing styles that allow them to engage almost immediately in the empathic exploration and experiential

search, it is also true that some clients in Northern European cultures (especially male clients) can struggle with the focus on exploring and expressing emotion, as opposed to working with cognition or action. Such clients nevertheless typically respond well to a relational offer that is both no-nonsense and genuinely empathic and caring, especially when accompanied by clear structure and experiential teaching about the nature and importance of emotion.

In addition, EFT can be used successfully with clients whose styles are generally external or interpersonally dependent, which can be associated with more collectivistic as opposed to individualistic cultural backgrounds (Kitayama, Markus, & Kurokawa, 2000). For these clients, it is essential for the therapist to provide solid empathy for client experiences

grounded in different cultural values, such as the need for social harmony, respect for elders, or traditional religious beliefs and practices. In these situations it is still important to work with clients to gradually create an internal focus through consistent empathic exploration of their inner experience and by occasional experiential teaching. In addition, treatment with these clients may emphasize the use of the more process guiding tasks such as focusing and empty-chair work.

As it is currently formulated, EFT is as not well suited for clients with psychotic processes, impulse control or antisocial personality patterns, or those in need of immediate crisis intervention or case management (e.g., acutely suicidal or experiencing current domestic abuse). In addition, we are not inclined to utilize this approach with those few clients who develop strong negative reactions to its internal exploration and

self-determination aspects or who find the therapist's relatively nondirective stance of not advising or interpreting to be unacceptable. It is best to refer such clients on to other treatments.

Clinical Illustration

met the diagnostic criteria for severe social anxiety, centering on fears of social situations, especially weddings and parties. She had a history of alcohol misuse but had been sober for at least 15 years and had had previous unsuccessful cognitive-behavioral therapy. She had a childhood history of emotional and sexual abuse. At the end of therapy she “confessed” that she had been severely suicidal when she started and had planned to kill herself if the therapy failed.

In terms of EFT case formulation (see Table 1), Carol’s main presenting problems were extreme social isolation and hypervigilance in social situations (Step 1); she was able to describe these painful experiences quite clearly and poignantly (Step 2). In spite of her external focus on others’ potential reactions to her, she was also able to turn her attention inward and to express her emotions in sessions openly and unguardedly (Step 3).

In the early stage of therapy, Carol described her history (Step 4) and explored her current and past experiences of social anxiety, which was a secondary reactive emotion, under which there was core primary maladaptive shame about her appearance, awkwardness, and being unwanted (Steps 6 & 8). In terms of themes (Step 10), her main treatment of self was one of self-attack/blame/neglect, while her view of others was that they were critical and rejecting; and she found herself unable to work or to form meaningful, close relationships with others. The key markers (Step 5) that she presented were unclear feelings (pointing to focusing), anxiety and self-critical splits (pointing to two-chair work), unresolved relational issues with her mother and father (pointing to empty-chair work) and unregulated anguish (pointing to the need for compassionate self-soothing).

Carol’s distress started at high levels through the first half of the therapy as she began to work with her anxiety splits and then moved into work with the deeper self-critical split, where her attempts to change led to harsh reprisals from her terrified inner critic, which interrupted her attempts to change and led to a sense of impasse and anguish (Step 9).

Through the use of these tasks (Steps 12 & 13), she and her therapist began to co-construct a useful formulation of the different emotion processes described above and their connection to her life narrative and presenting difficulties (Step 11); at the same time, she began to access a range of primary adaptive emotions and, through these, important unmet needs (Step 7): Thus, she more fully experienced her connecting sadness about the time and relationships she had lost, and with this the need to connect with other people, which

motivated her to seek out social situations (Step 14). Gradually over time she also began to access protective anger about the abuse she had suffered (and the associated need for better boundaries) and self-compassion for all she had been through, along with the need to comfort and support herself. Ultimately, she was able to feel pride for who she was and what she had been able to accomplish in her therapy. Her ability to access, symbolize, and regulate her painful emotions improved, and her sense of self was strengthened, to the point where the critical aspect became less afraid and diminished in power so that she was able to move past the impasse. She was largely improved by session 16; at that point her recent changes still felt fragile, so the last four sessions took place at monthly intervals providing an ad hoc

consolidation phase to her treatment, as she began attending social events and working in the profession that she had long trained for but never practiced. (A consolidation phase is not a formal part of EFT, but in this case one emerged spontaneously out of Carol’s change process.) Her large post-therapy gains were maintained at 6 and 18-month follow-up assessments.

After session 16 and before her four monthly consolidation sessions, Carol was interviewed by a researcher, and reported:

“When I think back from very, very early on in working with him, it’s been so

greatest thing that I’m feeling: It’s that I’m feeling a sense of belonging … Just this sense of general belonging.”

Conclusions/Key Points

Emotion-Focused Therapy (also known as Process-Experiential Therapy) is a contemporary, evidence-based humanistic psychotherapy that integrates person-centered, gestalt and existential approaches. It is based on contemporary emotion theory, and posits that human experience is organized around key emotion schemes and that emotion processes are essentially adaptive. Emotions can become problematic, however, through under- or over-regulation or when the primary adaptive emotion response is replaced by secondary reactive, primary maladaptive, or instrumental emotion responses. EFT is guided by a set of emotion change principles, including awareness, symbolization, regulation, expression, reflection, and transforming emotion with emotion. It is organized around an emotional deepening process in which therapists help clients move through the following sequence of emotion responses: undifferentiated distress; secondary reactive emotions; primary maladaptive emotions; core pain; and primary adaptive emotions. To do this, the therapist responds to key markers offered by clients, proposing appropriate therapeutic tasks such as unfolding problematic reaction points or two-chair work for internal conflicts. EFT has been applied to a wide range of clients, especially those presenting with depression, anxiety, interpersonal difficulties, as well as eating difficulties and other self-damaging activities. Finally, as EFT training has spread to different parts of the world, especially East Asia and South America, it has

increasingly embraced clients from different cultures. We have found that although cultures vary in terms what emotions (especially anger, shame, and sadness) are seen as appropriate to express in which situations and what key human needs (e.g., social harmony vs.

independence) are particularly culturally valued, basic human emotion processes and the needs associated with them are universal.

Review Questions

1. What is the EFT understanding of how working with emotion brings about change? 2. What kinds of emotion response are there in EFT and how do they differ from one another?

3. Describe what a therapeutic task is and give an example of one.

4. What kind of client presenting problems has EFT been found to be effective with? 5. Name three emotion change principles.

Resources Additional Book on EFT Practice

• Watson, Greenberg & Goldman (2007). Case Studies in Emotion-Focused Therapy for Depression: A Comparison of Good and Poor Outcome. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Recommended EFT Videos:

• Emotion-Focused Therapy for Depression (Les Greenberg, 2 sessions; American Psychological Association, 2006).

• Emotion-Focused Therapy Over Time (Les Greenberg, 6 sessions, with voice-over commentary; American Psychological Association, 2008).

• Emotion-Focused Therapy for Complex Trauma (Sandra Paivio, American Psychological Association, 2013).

• Case Formulation in Emotion-Focused Therapy: Addressing Unfinished Business (Rhonda Goldman, American Psychological Association, 2014).

Websites

www.iseft.org [Website for the International Society for Emotion-Focused Therapy] www.process-experiential.org [Learning book resource website]

www.emotionfocusedclinic.org [Les Greenberg’s website]

www.experiential-researchers.org [Contains information on EFT-friendly research instruments]

References

Angus, L., & Greenberg, L. (2011). Working with narrative in emotion-focused therapy. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Bordin, E. S. (1979). The generalizability of the psychoanalytic concept of working alliance. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 16, 252-260.

Dolhanty, J., & Greenberg, L. (2007). Emotion-focused therapy in the treatment of eating disorders. European Psychotherapy, 7, 97–116.

Elliott, R. (2013). Person-Centered-Experiential Psychotherapy for Anxiety Difficulties: Theory, Research and Practice. Person-Centered and Experiential Psychotherapies, 12, 14-30. DOI:10.1080/14779757.2013.767750

Elliott, R., Bohart, A.C., Watson, J.C., & Greenberg, L.S. (2011). Empathy. In J. Norcross (ed.), Psychotherapy relationships that work (2nd ed.) (pp. 132-152). New York: Oxford University Press.

Elliott, R., & Greenberg, L.S. (1997). Multiple Voices in Process-Experiential Therapy: Dialogues between Aspects of the Self. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 7, 225-239.

Elliott, R., Greenberg, L.S., & Lietaer, G. (2004). Research on Experiential Psychotherapies. In M.J. Lambert (Ed.), Bergin & Garfield’s handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change (5th ed.) (pp. 493-539), New York: Wiley.

Elliott, R, Hill, C.E., Stiles, W. B., Friedlander, M.L., Mahrer, A., & Margison, F. (1987). Primary therapist response modes: A comparison of six rating systems. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 55, 218-223.

Elliott, R., James, E., Reimschuessel, C., Cislo, D., & Sack, N. (1985). Significant events and the analysis of immediate therapeutic impacts. Psychotherapy, 22, 620-630.

Elliott, R., Wagner, J., Sales, C., Rodgers, B. & Alves, P., & Café, M.J. (in press).

Psychometrics of the Personal Questionnaire: A client-generated outcome measure. Psychological Assessment.

Elliott, R., Watson, J. C., Goldman, R.N., & Greenberg, L.S. (2004). Learning emotion-focused therapy: The process-experiential approach to change. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Elliott, R., Watson, J., Greenberg, L.S., Timulak, L., & Freire, E. (2013). Research on

humanistic-experiential psychotherapies. In M. J. Lambert (Ed.), Bergin & Garfield‘s Handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change (6th ed.) (pp. 495-538). New York: Wiley.

Faur, A., & Elliott, R. (2007). Self-Relationship Questionnaire. Unpublished questionnaire, Counselling Unit, University of Strathclyde.

Geller, S. M., & Greenberg, L. S. (2002). Therapeutic presence: Therapists’ experience of presence in the psychotherapy encounter. Person-Centered and Experiential Psychotherapies, 1, 71-86.

Goldman, R., & Zurawic, A. (July, 2012). Self-soothing in emotion-focused therapy. Paper presented at conference of World Association for Person-centred and Experiential Psychotherapy & Counselling, Antwerp, Belgium.

Goldman & Greenberg (2014). Case formulation in emotion-focused therapy. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Greenberg, L. S. (2002). Emotion-focused therapy: Coaching clients to work through their feelings. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Greenberg, L. S. (2010). Emotion-focused therapy: A clinical synthesis. Focus: The Journal of Lifelong Learning in Psychiatry, 8, 32-42.

Greenberg, L. S. (2011). Emotion-focused therapy. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Greenberg, L. S., Auszra, L., & Herrmann, I. R. (2007). The relationship among emotional productivity, emotional arousal and outcome in experiential therapy of depression. Psychotherapy Research, 17, 482–493.

Greenberg, L. S., & Elliott, R. (2012). Corrective experience from a humanistic/experiential perspective. In L. G. Castonguay & C. E. Hill (Eds.), Transformation in

psychotherapy: Corrective experiences across cognitive behavioral, humanistic, and psychodynamic approaches (pp. 85-101). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Greenberg, L. S. Elliott, R., & Lietaer, G. (1994). Research on humanistic and experiential psychotherapies. In A.E. Bergin & S.L. Garfield (Eds.) Handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change (4th ed.) (pp. 509-539). New York: Wiley.

Greenberg, L.S., & Goldman, R.N. (2007). Case formulation in Emotion-Focused Therapy. In T.D. Eels (Ed.), Handbook of Psychotherapy Case Formulation (2nd ed.) (pp. 379-411). New York: Guilford.

Greenberg, L.S., & Goldman, R.N. (2008). Emotion-Focused couples therapy: The dynamics of emotion, love, and power. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Greenberg, L.S. & Johnson, S. M (1988). Emotionally focused therapy for couples. New

York: Guilford.

Greenberg, L.S. & Paivio, S. (1997). Working with emotions in psychotherapy. New York: Guilford.

Greenberg, L. S., Rice, L. N., & Elliott, R. (1993). Facilitating emotional change: The moment-by-moment process. New York: Guilford Press.

Greenberg, L. S., & Safran, J. D. (1987). Emotion in psychotherapy. New York: Guilford Press.

Greenberg, L.S., & Watson, J.C. (2005). Emotion-Focused Therapy for Depression. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Greenberg, L.S., & Watson, J.C. (2005). Emotion-Focused Therapy for Depression. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Hatcher, R.L., & Gillaspy, J.A. (2006). Development and validation of a revised short version of the Working Alliance Inventory. Psychotherapy Research, 16, 1215-25.

Horvath, A., & Greenberg, L.S. (1989). Development and validation of the Working Alliance Inventory. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 36, 223-233.

Ito, M., Greenberg, L.S., & Iwakabe, S., & Pascual, A. (May, 2010). A task analysis of self soothing in emotion-focused therapy. Presentated at conference of Society for the Exploration of Psychotherapy Integration, Florence, Italy.

Lieberman, M. D., Eisenberger, N. I., Crockett, M. J., Tom, S., Pfeifer, J. H., Way, B. M. (2007). Putting feelings into words: Affect labeling disrupts amygdala activity to affective stimuli. Psychological Science, 18, 421-428.

Lietaer, G. (1993). Authenticity, congruence and transparency. In D. Brazier (Ed.), Beyond Carl Rogers: Towards a psychotherapy for the 21st centrury (pp. 17-46). London: Constable.

MacLeod, R., Elliott, R., & Rodgers, B. (2012). Process-Experiential/ Emotion-focused Therapy for Social Anxiety: A Hermeneutic Single-Case Efficacy Design Study. Psychotherapy Research, 22, 67-81. DOI:10.1080/10503307.2011.626805

Mahrer, A. R. (1996/2004). The complete guide to experiential psychotherapy. Boulder, CO: Bull.

Norcross, J. (ed.) (2011). Psychotherapy relationships that work (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.

Paivio, S.C., & Greenberg, L.S. (1995). Resolving “unfinished business”: Efficacy of experiential therapy using empty chair dialogue. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 63, 419-425.

Paivio, S. C., & Pascual-Leone, A. (2010). Emotion-focused therapy for complex trauma. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Pascual-Leone, A, & Greenberg, L.S. (2007). Emotional processing in experiential therapy: Why "the only way out is through." Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 75, 875-887. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.6.875

Rice, L.N. & Greenberg, L. (Eds.) (1984). Patterns of change. New York: Guilford Press. Rogers, C.R. (1957). The necessary and sufficient conditions of therapeutic personality

change. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 21, 95-103.

Shahar, B. (2013). Emotion-Focused Therapy for the Treatment of Social Anxiety: An Overview of the Model and a Case Description. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy. Published online: DOI: 10.1002/cpp.1853

Singh, M. (1994). Validation of a measure of session outcome in the resolution of unfinished business. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, York University.

Sutherland, O., Peräkylä, A., & Elliott, R. (2014). Conversation Analysis of the Two-Chair Self-Soothing Task in Emotion-Focused Therapy. Psychotherapy Research. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2014.885146

Timulak, L., & Elliott, R. (2003). Empowerment Events in Process-Experiential

Psychotherapy of Depression: A Qualitative Analysis. Psychotherapy Research, 13, 443-460.

Table 1 Steps and Stages of EFT Case Formulation

Stage 1: Establish relationship while unfolding the narrative and observing emotional processing style:

1. Listen to the presenting problems (relational and behavioral difficulties). 2. Listen for and identify poignancy and painful emotional experience .

3. Attend to and observe emotional processing style.

4. Unfold the emotion-based narrative/life story (related to attachment and identity). Stage 2: Co-create the case formulation emphasizing focus and core emotions (MENSIT):

5. Identify recurrent markers (M) for task work.

6. Identify underlying core emotion (E) schemes, adaptive and maladaptive. 7. Identify needs (N),

8. Identify secondary (S) emotions.

9. Identify interruptions (I) or blocks to accessing core emotion schemes. 10. Identify themes (T): self-self relations, self-other relations, existential issues/interrupted life projects

11. Co-construct the formulation narrative linking presenting relational and behavioral difficulties to triggering events and core emotion schemes.

Stage 3: Apply the case formulation by identifying emerging task markers, micro-markers and new meanings

12. Identify emerging task markers. 13. Identify micro-markers.

Table 2

Summary of Overall Pre-post Change, Controlled and Comparative Effect Sizes for EFT Outcome Research

n m sd

Pre-Post Change ES (mean g) By Assessment Point:

Post 34 1.22 .59

Early Follow-up (1-11mos.) 15 1.50 .62

Late Follow-up (12+ mos) 4 1.63 .48

Overall (mES):

Unweighted 34 1.20 .55

Weighted (dw) 1124 1.16 .42

Controlled ES (vs. untreated clients)b

Unweighted mean difference 12 1.29 .75 Unweighted m diff RCTs only 8 1.31 .72 Experiential mean pre-post ES 11 1.58 .75

Control mean pre-post ES 10 .21 .22

Weighted 255 1.05 .70

Weighted m diff RCTs only 116 1.31 .67

Comparative ES (vs. other treatments)b

Unweighted mean difference 11 .67 .50 Unweighted m diff RCTs only 9 .68 .56 Experiential mean pre-post ES 10 1.40 .60 Comparitive treatment mean

pre-post ES

10 .74 .71

Weighted mean difference 183 .57 .46

Weighted m diff RCTs only 156 .57 .50

Note. Hedge's g used (corrects for small sample bias). Weighted effects used inverse variance based on n of clients in experiential therapy conditions.