Depression and anxiety in residential aged care:

Attitudes, help-seeking and effectiveness of

group-based cognitive behaviour therapy

Tushara Wickrarnariyaratne

A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Psychology (Clinical)

of the Australian National University

I hereby certify that the work embodied in this thesis

is the result of original research and contains

acknowledgement of all non-original work.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This thesis would not have possible without the kind and generous assistance of many people. In particular, I would like to thank:

All the older adults who participated in this research and care managers of the facilities for providing me your time and allowing me into your lives. Your contribution is invaluable, not only to this thesis but to our continued efforts to try and improve our service to you.

My supervisor, Don Byrne, for seeing me through numerous false starts right to the end. I truly appreciate your patience and guidance.

Mike Bird, for inspiring me to work with older adults in the first place. Your generosity in imparting your skills and knowledge in your down-to-earth manner is something I will always be grateful for.

Katrina and Annaliese, for your advice and feedback on the content of my thesis. I am truly thankful for your support and ability to calm my nerves.

My friends, who are too numerous to name individually, for listening over endless cups of tea, your kind words and continued encouragement.

My parents, Tushan, Tushira, Iris and Sandosh for your unwavering love and support.

ABSTRACT

TABLE OF CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1 Introduction

CHAPTER 2 Depression and anxiety in older adults

Depression in older adults Epidemiology

Experience and expression of depressive symptoms in older adults Late onset versus early onset

Medical comorbidity

Functional impairment/disability Cognitive impairment

Suicide

Anxiety disorders in older adults' . Epidemiology

Experience and:,expression·of anxiety symptoms in older adults Medical comorbidity·

Cognitive impairment

Functional impairment/disability Comorbid depression and anxiety

Treatment of depression and anxiety in older adults Pharmacotherapy

Psychotherapy

Mental health service utilisation among older adults Summary and conclusions

CHAPTER 3 Help-seeking behaviour for mental illness in older adults

Theoretical frameworks

Behavioural model of health services use Theory of planned behaviour

Factors influencing help-seeking behaviour among older adults Summary and conclusions

CHAPTER 4 Depression and anxiety in residential care

Characteristics of RACF residents Demographics

Care needs of residents

Depression in residential care Anxiety in residential care

Comorbid depression and anxiety in residential care

Particular vulnerabilities of older adults in residential care Management of depression and anxiety in residential care

Overcoming barriers to care for depression and anxiety in RACFs Summary and conclusion

CHAPTER 5 Residential-dwelling older adults' help-seeking behaviour for

56 57 57 57 59 61

62

62

65 69 71depression and anxiety 73

The present study 74

Method 75

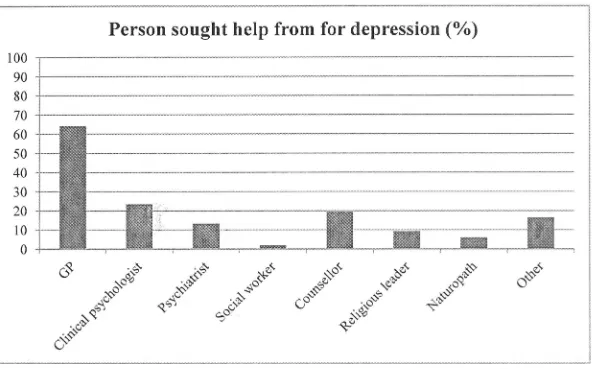

Results 82

Older adults' attitudes to depression 82

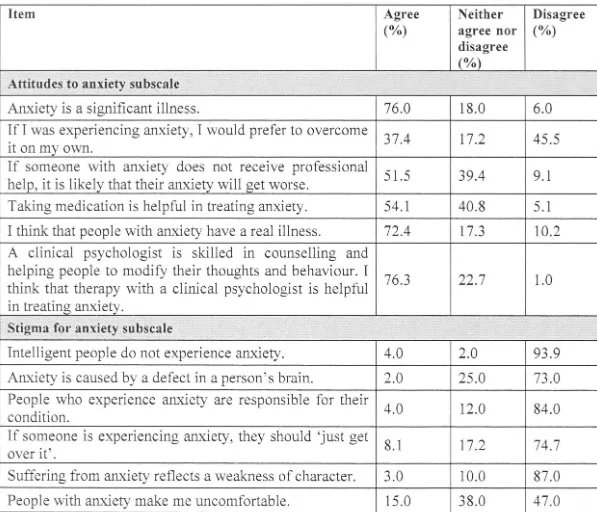

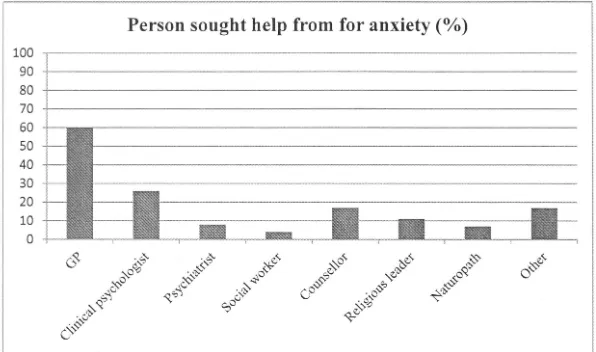

Older adults' attitudes to anxiety 90

Discussion 100

CHAPTER 6 Cognitive Behaviour Therapy for depression and anxiety

with older adults 106

Treatment for geriatric depression and anxiety 107

CBT for depression with older adults 109

CBT for anxiety with older adults 110

Tailored CBT for older adults 111

Group CBT with older adults 115

,

Group CBT for depression and anxiety in RACFs 116

CHAPTER 7 Group CBT for anxiety and depression in residential care 119

The present study 120

Method 120

Results 127

Discussion 132

CHAPTER 8 General discussion 138

The relationship between attitudes and help-seeking 141

The role of GPs in ensuring the .mental wellbeing of their older clients 141

The effectiveness of group-based CBT in treating depression and anxiety in

RACFs 142

Limitations 143

Future directions 144

Conclusion 145

References 148

CHAPTER!

Introduction

Late-life anxiety and depressive disorders have been largely under-researched until recently, even though older adults are particularly vulnerable to developing these mental illnesses due to multiple risk factors such as comorbid physical and cognitive illness (Bird & -Parslow, 2002; Blazer, 2003). Unsurprisingly, the prevalence of depression and anxiety in older people is high, particularly among those who live in permanent residential aged care (Teresi, 2001 ). Unfortunately, depressed and anxious older adults are . chronically under-diagnosed and under~treated . (Alexopoulos, 2005; Bagulho, 2002; Wolitzky-Taylor, Castriotta, Lenze, Stanley, & Craske, 2010), resulting in ongoing distress, reduced quality of life and increased risk of suicide. The rate of depression in residential aged care facilities (RACFs) has been found to be up to four times that of older people living in the community (Jongenelis et al., 2004) and up to 50% of depression occurring in RACFs goes undetected by physicians (Davison et al., 2007), yet older people in permanent residential care have continued to be explicitly excluded from mental health research. As a result, little, if anything, is known about the help-seeking behaviour of older adults in residential care, and what strategies can be implemented in order to improve the current dismal rates of diagnosis and treatment of depression and anxiety in RACFs.

The aim of this dissertation is to augment current knowledge about the delivery of effective treatment for depression and anxiety to RACF populations through a two-pronged approach. Firstly, by exploring the attitudes that older adults who live in

influence help-seeking for these disorders and secondly, by offering and evaluating an evidence-based psychotherapy to depressed and anxious older people in residential care. This approach has informed the design of two studies which will be presented in this thesis. It is anticipated that the findings of these studies will highlight possible ways to improve the rates of under-treatment of depression and anxiety among older people living in permanent aged care.

The following chapter opens with an overview of depression and anxiety among older adults, including prevalence rates and the unique manifestation of these disorders among older populations. The particular risk factors faced by older adults for depression and anxiety such as physical illness, cognitive impairment and functional disability will then be explored in tum, followed by a brief discussion of existing pharmacological and psychological treatments available despite current low rates of detection, diagnosis and treatment.

The focus of the literature review in Chapter 3 then turns to help-seeking behaviour among older adults. The theoretical framework underpinning health-seeking behaviour will be discussed and applied to help-seeking for depression and anxiety among older adults. The factors influencing older adults' help-seeking for mental illness will be explored in detail and reveal a dearth of current knowledge on the specific attitudes that older populations have towards anxiety and depression and more importantly, how that would affect their willingness to seek help for these disorders.

developing late-life depression and anxiety. Chapter 4 focuses on older people in residential care, who are arguably the most impaired group of older adults. A review of the literature will reveal an incongruity between the heightened susceptibility for residential aged care populations to develop anxiety and depressive disorders and the significant inadequacy of current modes of mental health service delivery in meeting their needs.

Study 1 is presented in Chapter. 5, and aims to uncover the attitudes that older people in residential aged care have towards depression and anxiety, and how their attitudes affect their willingness to seek help for these disorders. Furthermore, older people's preferences for who they would seek help from and perceived barriers to help seeking will be explored. Positive attitudes to'.vards depression and anxiety and a high level of willingness to seek external help for,.these disorders were found ainong the older people surveyed. The main practical barrier to treatment cited was cost.

Chapter 6 reviews the available treatments for geriatric depression and anxiety, with a focus on cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT). Different modalities of CBT for depression and anxiety with older people are also explored, revealing that group CBT is particularly beneficial for RACF populations. Findings from Study 1 suggest that older people in residential care are willing to engage in therapy for depression and anxiety, and the literature confirms that there are effective evidence-based non-pharmacological treatments for older adults.

standardised measures and the results revealed that providing psychotherapy to older people in RACFs is worthwhile.

CHAPTER2

Depression and anxiety in older adults

Australia's population, as is in the rest of the developed world, is rapidly ageing. The proportion of older adults ( aged 65 and above) in the Australian population was 8.3% in 1970 and increased to 13.5% or 3 million people by June 2010 (Commonwealth of Australia, 2010). Alarmingly, by 2050, the number of people aged 65 and above in Australia will reach approximately 8.1 million, or 22.6% of the total population. Interestingly, the number of oldest old (people aged 85 and above) has been projected to rise the most rapidly, from 1.8°/o in 2010 to 5.1 % in 2050 (Commonwealth of Australia, 2010).

Depression in older adults

Geriatric or late-life depression refers to the occurrence of depressive syndromes in

adults aged 65 and above. Depression significantly reduces the quality of life in older

adults, and is believed to be the most frequent cause of emotional suffering in later

life (Blazer, 2003). According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-IV),

the features of a major depressive disorder include the presence of five or more of

the following symptoms: depressed mood, loss of interest or pleasure, weight loss or

gain of more than 5% of body weight, insomnia or hypersomnia, psychomotor

agitation or retardation, fatigue, feelings of worthlessness or inappropriate guilt,

reduced concentration and recurrent thoughts of death or suicide (American

Psychiatric Association, 2000).

In

addition, at least one of the symptoms must beeither depressed mood or loss of interest and pleasure, and the syndrome should

endure for at least two weeks, cause distress or functional impai.tment, and not be a

result of substance abuse, a general medical condition or bereavement (American

Psychiatric Association, 2000). Older adults can also experience depression as part

of dysthymic disorder, bipolar affective disorder or adjustment disorder with

depressed mood.

Epidemiology

The current version of the DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) does

not provide specific diagnostic criteria for depression for older adults, which has led

to disagreement about the recognition and true prevalence rates of geriatric

depression (Bryant, 201 O; O'Connor, 2006). Though some authors have speculated

that the prevalence of mood disorders in the older population decreases compared

discrepancies in prevalence rates are the product of inconsistent sampling and

measurement. Nevertheless, adverse effects of depression on the quality of life,

morbidity, non-suicide mortality and suicide rates of older people cannot be ignored

(Alexopoulos, 2005; Blazer, 2003; Nordhus, 2008; Smits et al., 2008; Zisook &

Downs, 1998).

The reported prevalence rate for geriatric depression varies widely, from 1-16% in

older people who live in the community (Alexopoulos, 2005; Blazer, 2003; Koder,

Brodaty, & Anstey, 1996) and much higher rates of 12-30% in acute medical and

psychogeriatric settings (Bryant, Jackson, & Ames, 2009; Park & Unlitzer, 201 1)

and up·.to 50% in residential aged care facilities (RACFs), nursing homes or

long-term care facilities (Hoover et al., 201 O; Teresi, 2001 ). The highest prevale.nce · of

depressive symptoms have been found amongst the oldest-old, reaching 13% in

people aged 85 and above (Blazer, 2003; Zisook & Downs, l 9_98). Throughout the

adult life cycle, female gender is a risk factor for depression, but this gender

difference in the prevalence of depression seems to narrow after age 80 (Samuelsson,

McCamish-Svensson, Hagberg, Sunstrom, & Dehlin, 2005; Zisook & Downs, 1998).

Other risk factors for depression in older adults are those associated with ageing,

including physical disability, cognitive impairment and lower socioeconomic status

(Blazer, 2003; Samuelsson, et al., 2005).

In further evidence demonstrating that depression can be expressed differently in

different age groups and cultures, a recent study comparing rates of geriatric

depression in 10 developed and 8 developing countries found that prevalence rates

for depression decreased with age in developed countries, but increased with age in

developing countries (Kessler et al., 2010). The authors did not investigate the

explore the characteristics of older adults with depression in developed versus developing countries in order to uncover the mechanism underlying the expression of depression in different groups. This may also be a step to uncovering how depression might operate differently in older populations compared to younger populations.

Experience and expression of depressive symptoms in older adults

The wide vanance of prevalence rates of depression in older adults has been attributed to existing diagnostic criteria not being sufficiently sensitive to the unique manifestations of depression in older adults (Bryant, 201 O; Hybels, Landerman, & Blazer, 2011; Nordhus, 2008). Preliminary studies have found that older people with major depression seem to endorse different symptoms compared to younger patients, yet the symptom profile of depressed older adults have been found to be more varied

people are being overlooked and under-diagnosed (Jeste, Blazer, & First, 2005).

Hence, the push towards age-sensitive diagnostic criteria is an extremely urgent one.

Late onset versus early onset

The features of late-life depression can also differ depending on whether it is early or

late onset. Individuals with early onset depression are those who experience their

first depressive episode before the age of 60, and those with late onset depression

experience their first episode from age 60 and beyond. Late onset depression has

been associated with a lower family history of mood and other psychiatric disorders,

a higher prevalence of cognitive impairment and .. dementing illnesses; lower

incidence of personality abnormalities and less dysfunctional marital relationships

compared with early onset depression (Alexopoulos, 2005; Blazer, 2003; Jeste; et al.,

2005);

The interest in distinguishing between early and late onset depression has arisen

because it has been suggested that what contributes to the etiology of depression

corresponds to age of onset (Blazer, 2003; Jeste, et al., 2005). For instance, the role

of heredity is much more prominent in early onset depression compared to late onset

depression (Bagulho, 2002). In addition, vascular depression, believed to be linked to ageing-related vascular lesions in the brain is much more common with late onset

depression (Blazer, 2003; Blazer & Hybels, 2005; Jeste, et al., 2005).

Medical comorbidity

A major confounding factor in the assessment and diagnosis of depression in older

deteriorates functionally with time. It has been reported that up to 88% of older

adults suffer from one or more chronic illnesses; the most common of these being

arthritis, hypertension, hearing loss, urinary incontinence, heart disease, diabetes,

visual impairment and cerebrovascular disease (Blazer, 2003; Park & Unlitzer, 2011;

Zisook & Downs, 1998). Consequently, geriatric depression will often occur in the

context of one or more medical conditions (Alexopoulos, 2005; Blazer, 2003;

Bryant, et al., 2009; Jeste, et al., 2005; Loi & Chiu, 2011; Park & Unlitzer, 2011;

Zisook & Downs, 1998). Comorbid depression has been found to be particularly

high in older adults experiencing myocardial infarction and other heart conditions,

neurologic disorders, endocrine diseases, stroke, diabetes and cancer (Alexopoulos,

2005; Blazer, 2003; Park & Unlitzer, 2011 ).

The relationship between depression and medical illness among older adults is a

bi-directional one. Medical illness is a risk factor for depression, and depression is

associated with increased morbidity, mortality, delayed recovery and poorer

prognosis for those suffering from a medical condition (Park & Unlitzer, 2011 ). The

reciprocal relationship between depression and physical illness is complex (Zisook &

Downs, 1998), and it has been suggested that the stressful nature of experiencing a

debilitating illness that affects one's general wellbeing is the mechanism that

increases one's risk for depression (Bruce, 2001 ). Similarly, symptoms of depression

such as amotivation, hopelessness and anhedonia are associated with poor health

behaviours resulting in poor treatment adherence, low physical activity and poor diet

that may adversely affect outcomes of chronic medical conditions (Bruce, 2001; Park

& Unlitzer, 2011).

Despite the evidence demonstrating the increased risk for depression among

of chronic medical conditions increased with age in both developed and developing countries, the association between depression and chronic medical conditions decreased with age in developed countries (Kessler, et al., 2010). The authors proposed a few possibilities for their finding, one of which was that older adults are thought to be more accepting of the inevitability of physical illnesses than younger people, buffering them from adverse psychological effects associated with a physical illness. They also suggested that older adults may be more likely to utilise coping strategies that accept and adapt to the adverse situation rather than trying to change the situation or that older adults might have a reduced capacity to recognise and articulate mood states due to autonomic, endocrine or cognitive dysfunction. However, the authors acknowledged that the reasons for their surprising finding are unclear and more evidence is required to fully understand the causal processes in the association bet\veen depression and physical illness in old age (Kessler, et al., 2010).

Generally, older adults with depression tend to have a heightened focus on somatic rather than psychological symptoms (O'Connor, 2006; Zisook & Downs, 1998), which compounds the problem of under-diagnosis. The challenge therefore lies in distinguishing the symptoms of an underlying medical condition, symptoms of depression that result from a response to a medical condition, and depressive symptoms independent of a medical condition (Jeste, et al., 2005) in order to formulate an accurate diagnosis and corresponding treatment for the older person.

Functional impairment/disability

remain or improve together (Lenze et al., 2001 ). Anxiety has also been suggested to increase the risk for disability, but it has not been found to operate independently of depression, and this was the case even for people at the very old age of 90 years (Van der Weele, Gussekloo, De Waal, De Craen, & Van der Mast, 2009).

The World Health Organization considers depression to be the leading cause of disability and estimates that by 2020, depression will be the second largest contributor to global burden of disease (World Health Organization, 2012). Disability or functional impairment is defined as restriction or lack of ability to perform an activity because of impairment and covers basic activities of daily living (AD Ls) such as self-care tasks like eating, dressing, bathing, toileting and mobilising, and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) which are less basic tasks that are essential to living independently, such as food preparation, caring for the home and maintaining finances (Bruce, 2001; Lenze, et al., 2001 ).

The functional status of older adults is an important construct because their ability to carry out ADLs and IADLs directly affects their ability to live independently in the community, and also influences their quality of life (Rogers et al., 2010). An increase in physical disability has been found to be a significant predictor of RACF placement as well as increased health care utilisation (Lenze, et al., 2001 ).

with a 60% or higher increase in risk for disability (Bruce, 2001 ). The converse has also been found in other studies, where increases in disability level over time predicted the emergence of depressive symptoms (Bruce, 2001 ).

In

addition, this significant association between depression and disability cannot be accounted for by an existing general medical illness in older people experiencing depression (Lenze, et al., 2001 ).The documented synchronicity between depression and functional impairment lends

further support to the need for timely diagnosis and treatment of geriatric depression

in order to avoid an exacerbation of both conditions which could result in

detrimental effects to the older person's health and a severe decline in function,

warranting a nursing home placement.

Cognitive impairment

Late-life cognitive problems lie on a spectrum from normal age-related cognitive

decline to mild cognitive impai1ment and at the extreme, dementia. Cognitive

impairment commonly co-occurs with geriatric depression and is associated with

increased risk of adverse outcomes for physical health, functional status and

mortality (Steffens & Potter, 2008; Zisook & Downs, 1998). Between 30-50% of

older people with Alzheimer's disease, the most common form of dementia, also

experience clinically significant depressive symptoms (Alexopoulos, 2005; Blazer &

Hybels, 2005; Rozzini, Chilovi, Riva, Trabucchi, & Padovani, 2011; Steffens &

Potter, 2008). High levels of comorbid depression are also common in people with

other forms of progressive dementing illnesses such as vascular dementia (31.4%),

dementia with Lewy bodies, Parkinson's disease and Huntington's disease (Bagulho,

2002; Steffens & Potter, 2008).

The exact mechanisms underlying the relationship between depression and cognitive

impairment are yet to be established; particularly whether depression is a risk factor

or a prodrome of dementia. Indeed, various studies have found that a prior history of

depression increases one's risk for the development of dementia in later life, giving

rise to the idea that depressive symptoms may be an early manifestation of a primary

Jolles, & Verhey, 2011; Steffens & Potter, 2008). However, the co-occurrence of

depression and dementia reflects the complex, heterogeneous nature and etiologies

of both these conditions, which makes differential diagnosis between a depressive

disorder and an early dementing disorder a difficult task. There exists an overlap not

only in the cognitive symptoms of depression and dementia ( e.g. poor memory and

concentration), but also symptoms such as fatigue, social withdrawal and irritability

(Insel & Badger, 2002; Verkaik, Francke, van Meijel, Ribbe, & Bensing, 2009;

Zisook & Downs, 1998). Not surprisingly, misdiagnosis between depression and

dementia can commonly occur. Six percent of a random sample of hospital patients

with a main diagnosis of dementia were found to have been misdiagnosed and were .

instead experiencing depression (Ryan, 1994 ).

Interestingly, older adults presenting with a primary m0od disorder are more. likely

to minimise symptoms of dysphoria and have more complaints about memory

problems whereas individuals with a primary cognitive impairment are more likely

to minimise and compensate for their cognitive disturbances while openly expressing

their disappointment (Zisook & Downs, 1998).

Distinguishing between a presentation of depression, early cognitive impairment or

comorbid depression and cognitive impairment at assessment is essential for

treatment planning and providing sufficient support to not only the older person with

the disorder, but to their families as well, given the evidence that depression can

complicate the course of Alzheimer's disease by increasing disability and physical

aggression, which in tum can result in greater carer burden (Blazer, 2003). Accurate

diagnosis and treatment will ensure more positive prognoses for older adults whether

they are experiencing depression, cognitive impairment or a combination of these

Suicide

'·The most serious consequence of untreated depression is death" (Zisook &

Downs, 1998:83)

Older adults, together with younger males, are at higher risk for suicide than any

other age group globally (Conwell, Duberstein, & Caine, 2002; Woods, 2008b ).

Studies have found that the rate of completed suicide for older adults is

approximately twice that of younger age groups (Alexopoulos, 2005; Conwell, et al.,

2002; Zisook & Downs, 1998) and rates of suicidal ideation in community and

residential settings are similar at 6.5-7% in the month preceding assessment

(Malfent, Wondrak, Kapusta, & Sonneck, 2010). This is consistent with the finding

that rates of suicidal ideation and attempted suicide decrease with age, but that

among those who attempt suicide, older adults are more likely to succeed (Hepple &

Quinton, 1997; Nordhus, 2008). This is due to the fact that older adults tend to give

fewer warnings to others about their plans to suicide, use more lethal methods, and

enact these methods with greater planning and resolve, reflecting their diminished

physical resilience, greater isolation and greater determination to die (Conwell, et al.,

2002). Demographically, older age, male gender and white race are particular risk

factors for suicide, as males are around twice as likely to complete suicide compared

to females; a trend present at all ages (Conwell, et al., 2002; Woods, 2008b ). Elderly

men are twice as likely to use violent means to suicide, with hanging being the most

frequent method compared to drug overdose in females, though across gender, drug

overdose is the most common method with a third of older males and two thirds of

older women completing suicide by voluntary drug ingestion (Blazer, 2003; Woods,

The predominant independent risk factor for suicide in older adults across cultures is depression, which has considerably greater odds than any other risk factor (Bagulho, 2002; Conwell, et al., 2002; Malfent, et al., 201 O; Saz & Dewey, 2001; Sun, Schooling, Chan, Ho, & Lam, 2011 ). Older adults with depression have been found to be much more likely to commit suicide than depressed younger people in Australia (Snowdon, 1997). Depressive symptoms are present in about 80% of individuals aged 74 and above who complete suicide (Conwell, et al., 2002), yet less than a fifth were receiving mental health care at time of death (Woods, 2008b ). Older adults experiencing late onset depression who died by suicide have been found more often to be male, married, not living alone, were less likely to have a history of comorbid psychiatric illness or self-harm compared to those with early onset depression; however both groups used similar 1neans to suicide (Voshaar, Kapur, Bickley, \Villiams, & Purandare, 2011 ).

Physical illness, particularly those with associated pain, and functional impairment have also been found to elevate the risk for suicide, but they are largely mediated by depression (Conwell, et al., 2002; Woods, 2008b ). Other statistically significant risk factors for suicide in older adults are prior history of suicide attempts, anticipatory fear of being placed in a nursing home, bereavement, social isolation, loneliness, poor sleep quality, stressful life events such as financial hardship and family discord and obsessional or anxious personality traits (Blazer, 2003; Malfent, et al., 201 O; Woods, 2008b).

important factor in increasing suicide risk among older adults (Woods, 2008b ). In

addition, Conwell et al. (2002) found neuropathological changes in older people who

attempted or completed suicide, which may be associated with reduced executive

function found in people with depression. These findings strengthen the notion that

effectively addressing depressive disorders in older adults will drastically reduce the

rates of suicide in this high risk population.

Anxiety disorders in older adults

Anxiety disorders cover a number of conditions whose main features are persistent

and excessive worry. Anxiety disorders are common in older people and are

associated with high levels of emotional distress, impairment, reduced life

satisfaction and lowered quality of life. Similar to the case with depression, the

current diagnostic criteria for anxiety disorders in the DSM-IV (American

Psychiatric Association, 2000) do not have age specifiers for older adults, which

makes accurate diagnosis problematic, and has resulted in ambiguity about the nature

of anxiety in older adults and the prevalence of threshold level anxiety disorders in

this population (Bryant, Jackson, & Ames, 2008; Jeste, et al., 2005; Jorm, 2000a;

Mahlman et al., 2011).

Epidemiology

The prevalence of late life anxiety disorders ranges from 1.2% to 15% in community

settings and 1 % to 28% in clinical settings (Bryant, et al., 2008; Samuelsson, et al.,

2005; Wolitzky-Taylor, et al., 2010). The prevalence of anxiety symptoms

experienced by older people is much higher, however, from 15% to 52.3% in the

community and 15% to 56% in clinical samples (Bryant, et al., 2008; K vaal,

level anxiety in older adults, it would appear that older populations experience a

lower rate of anxiety disorders compared to younger populations (Wolitzky-Taylor,

et al., 2010). However, the extremely high rates of subthreshold level late life

anxiety lend credence to the increasingly accepted view that anxiety disorders are

indeed as common in older adults as they are in younger populations, but that current

diagnostic tools are not sufficient to accurately capture the manifestation of anxiety

in older people.

The most common anxiety disorders occurring in late life are generalised anxiety

disorder (GAD) and specific phobia. The prevalence of GAD has been found to be between 1.2% and 7.3% (Gorn;alves, Pachana, & Byrne, 2011; Mackenzie, Reynolds, Chou, Pagura, & · Sareen, 2011; Wolitzky-Taylor, et al., 2010) and the prevalence of specific phobia ranges from 1.4 % to 10.2% (Bryant, et al., 2008;

Wolitzky-Taylor, et al., 2010). It is likely that the high rates of_ specific phobia are

due to a phenomenon unique to older adults: fear of falling, where 7% to 14% of community-dwelling older adults have · reported moderate to severe fear and

avoidance of numerous situations due to this fear (Mahlman, et al., 2011 ). The

prevalence of other anxiety disorders in older adults is relatively low, but as stated

above, these figures could be an under-representation due to a lack of sensitivity of current diagnostic criteria for older adults. 0.6% to 2.3% of older people have been diagnosed with social phobia, (Wolitzky-Taylor, et al., 2010), 0.4% to 2.8% with

panic disorder (Chou, 201 O; Wolitzky-Taylor, et al., 2010), 0.1 % to 0.8% with

Late onset anxiety disorders have been found to be unlikely, though the occU1rence

of first episode anxiety in late life have been observed (Chou, 2009; Gon9alves &

Byrne, 2012b; Nordhus, 2008). Unlike the case with depression, however, no

significant differences have been found between early onset and late onset anxiety

disorders in older people (Wolitzky-Taylor, et al., 2010).

Risk factors for late-life anxiety include female sex, chronic medical illness,

impaired subjective health, impaired physical functioning in ADLs, stressful life

events, having an external locus of control, being single, divorced or separated and

lower education level (Gon9alves, et al., 2011; Mackenzie, et al., 2011;

Wolitzky-Taylor, et al., 2010).

This dissertation will focus on GAD-type anxiety because of its high prevalence in

older populations, and its high level of comorbidity with geriatric depression

(Gon9alves, et al., 2011; Mackenzie, et al., 2011; Schoevers, Deeg, van Tilburg, &

Beekman, 2005).

Experience and expression of anxiety symptoms in older adults

The growing body of literature on anxiety disorders in older adults is increasingly

indicating that the nature and clinical expression of anxiety symptoms change with

age, resulting in older adults experiencing and reporting their symptoms of anxiety in

a different way to younger populations (Bryant, 201 O; Kogan, Edelstein, & McKee,

2000; Mahlman, et al., 2011; Wolitzky-Taylor, et al., 2010). A common example is

that older adults are more attuned to physiological symptoms of anxiety such as

dizziness and shakiness, and will therefore over-endorse somatic complaints and

under-report psychological symptoms (Mahlman, et al., 2011; Wolitzky-Taylor, et

anxiety is stigma and lack of knowledge about mental illness that exists within this cohort (Bryant, 201 O; Mahlman, et al., 2011 ).

The qualitative nature of worry content between younger and older age groups also differ, with older adults reporting more worry about health, disability and finances compared to work-related worries in younger adults (Gon9alves, et al., 2011; Kogan, et al., 2000; Mahlman, et-al., 2011 ). Age-specific fears have also been established, namely fears of falling, fears of being a burden and fears of losing one's independence, and associated age-specific maladaptive avoidance such as avoiding going out of the house or avoiding seeking help (Bryant, et al., 2008; Mahlman, et al., 2011; Wolitzky-Taylor, et al., 2010). Within specific anxiety disorders, age differences also exist. For instance, older adults with panic disorder have reported fewer panic symptoms, less arousal and anxiety and higher levels of functioning compared to younger· people (Wolitzky-Taylor, et al., 2010).. It has also been suggested that older adults experience and understand e1notions in a different manner to younger adults, with less negative affect and less autonomic responses to strong emotional states (Wolitzky-Taylor, et al., 2010), which will influence the perceived severity of reported distress.

under-treatment of anxiety disorders among older populations. A number of authors have

made suggestions about how current diagnostic tools can be modified in order to

rectify this shortcoming so that anxiety in older adults can be more accurately

diagnosed, and more importantly, responded to with treatment (Jeste, et al., 2005;

Lenze & Wetherell, 2011; Mahlman, et al., 2011 ).

An additional complicating factor that can lead to under detection of anxiety

disorders in older adults is that in retirement, older people can more effectively avoid

anxiety-provoking situations, and thus report less impairment in daily functioning

(Bryant, 2010). The knowledge and skill of clinicians in dealing with an older

population is also critical, because few clinicians are able to distinguish between

adaptive and pathological anxiety, and the tendency to misattribute anxiety

symptoms in old age to 'normal ageing' (Wolitzky-Taylor, et al., 2010). In the same

way, the criterion of excessiveness which is critical in the diagnosis of clinical

anxiety becomes vague because of the subjectivity of what is deemed excessive

worry in an older population (Mahlman, et al., 2011 ).

Medical comorbidity

As with depression, anxiety disorders in older adults frequently co-occur with

medical illnesses. Associations have been found between anxiety and conditions

such as cardiovascular diseases, gastrointestinal diseases, respiratory conditions,

vestibular problems, diabetes, pain disorders and arthritis (El-Gabalawy, Mackenzie,

Shooshtari, & Sareen, 2011; Mackenzie, et al., 2011; Mahlman, et al., 2011;

Wolitzky-Taylor, et al., 2010). In fact, El-Gabalawy and colleagues (2011) found

that the higher number of physical health conditions experienced by an older person,

admission to hospital, older adults have been found to report higher rates of comorbid anxiety compared to depression (Bryant, et al., 2009).

The relationship between anxiety and physical illness in older adults is bi-directional. Physical illnesses can directly elicit anxiety through emotional arousal resulting from the uncertainty of health outcomes (El-Gabalawy, et al., 2011) or through the symptoms of the disease itself. For instance, the symptoms of cardiac, respiratory and vestibular problems greatly mimic anxiety symptoms and can lead to further anxiety (Wolitzky-Taylor, et al., 2010). Conversely, prolonged physiological arousal associated with anxiety can lead to the deterioration of neural, bone and muscle tissue, thereby increasing one's susceptibility to medical conditions (El-Gabalawy, et al., 2011 ). Prolonged physiological arousal due to both anxiety and pain can also impair the cardiovascular and metabolic systems of the body, the brain and immune system, which in turn can lower pain threshold and therefore exacerbate subjective experience of pain in an older person (El-Gabalawy, et al., 2011 ). Anxiety disorders and physical health conditions can also mutually maintain one another if the older person experiencing anxiety feels less able to deal effectively with their medical issues, leading to lower adherence to treatment, which may then in turn worsen the physical health problem (El-Gabalawy, et al., 2011 ).

Cognitive impairment

Anxiety disorders are frequently comorbid with cognitive decline. As mentioned

earlier, cognitive impairment is best conceptualised as a spectrum from normal

age-related decline to dementia at the most severe end. Research suggests that normal

ageing decrements in cognitive function do not have a negative effect on older

adults, but clinical level anxiety symptoms and significant levels of cognitive decline

do (Beaudreau & O'Hara, 2008). The prevalence estimates for anxiety disorders in

people with dementia is between 5% to 21 % (Wolitzky-Taylor, et al., 2010). A study

found that the prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms ( e.g. agitation, apathy,

hallucinations, sleep impairment) including anx_iety were as high as 43% in people

with mild cognitive impairment and 80% in those with dementia (Lyketsos et al.,

2002).

The presence of anxiety symptoms in older adults with cognitive impairment is

associated with poorer prognosis, doubling the risk of mild cognitive impairment

converting to dementia, and accelerating the rate of cognitive decline (Beaudreau &

O'Hara, 2008). Anxiety or worry symptoms are present in about 70% of people with

Alzheimer's disease and have been found to be associated with higher rates of

behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) including wandering

and aggression (Beaudreau & O'Hara, 2008). On the other hand, cognitive

impairment is also related to poorer prognosis and treatment resistance for late-life

anxiety disorders (Beaudreau & O'Hara, 2008).

Differentiating between the symptoms of cognitive impairment and anxiety disorders

is challenging because of the significant amoun,t of overlap between symptoms ( e.g.

Wolitzky-Taylor, et al., 2010). However, the relationship between anxiety and cognitive

impairment is reciprocal and each condition increases the risk for the other

(Beaudreau & O'Hara, 2008; Mahlman, et al., 2011 ). Early investigations suggest that overlapping pathophysiological mechanisms in the brain associated with both

anxiety and cognitive impairment (i.e. neurochemical and structural alterations,

reduced neurotransmitter function, neuroendocrine dysfunction) provide a potential

substrate for this relationship (Beaudreau & O'Hara, 2008).

Functional impairment/disability

Though current research on anxiety and disability in older adults is not as extensive as that for depression, the indication is that anxiety is an independent predictor of disability (Brenes et al., 2005; Gon9alves, et al., 2011; Porensky et al., 2009;:'·

Wolitzky-Taylor, et al., 2010). The domains where impairment associated with

--anxiety have the greatest effect are ability to perform ADLs, social functioning, vitality and role limitations due to emotional health (Brenes, et al., 2005; Porensky, et al., 2009). This suggests that older adults with anxiety experience a reduction in their ability to not only carry out their regular daily activities, but also to socialise

with their friends and family (Porensky, et al., 2009). As a result, older adults with anxiety have been found to have a poorer quality of life and diminished wellbeing (Wolitzky-Taylor, et al., 2010).

As with the other significant conditions associated with anxiety disorders in older

people, the relationship between anxiety and disability is likely to be dynamic and

bi-directional, with more severe anxiety being associated with greater disability and

lower health-related quality of life (Porensky, et al., 2009). Anxiety could be linked

of anxiety such as shakiness or dizziness could affect an older person's ability to

walk or perform even simple physical tasks (Brenes, et al., 2005). Anxiety could also

heighten one's perceived level of risk and therefore increase avoidance behaviours

resulting in greater disability, or anxiety symptoms could indicate an underlying

comorbid medical condition which could directly affect one's level of physical

functioning (Brenes, et al., 2005). Regardless of the underlying mechanism,

disability associated with anxiety disorders significantly lowers the quality of life in

older adults.

Comorbid depression and anxiety

Depression and anxiety frequently present together in older adults, both at clinical

and subclinical levels (Blazer & Hybels, 2005; Lenze et al., 2000; Prina, Ferri,

Guerra, Brayne, & Prince, 2011 ). The prevalence rates for comorbid late life anxiety

and depression have been reported to be between 1.8°/o to 8.4% in community

settings and approximately 14.8% in primary care and psychiatric settings (Kvaal et

al., 2008; Prina, et al., 2011 ). A community-based study found that 4 7 .5% of older

people with a diagnosis of major depressive disorder had a concurrent

threshold-level anxiety disorder, and 26.1 % of those with an anxiety disorder also met criteria

for major depressive disorder (Beekman et al., 2000). The prevalence of comorbid

depression and aILxiety can be much greater in clinical settings compared to

community settings, which has been attributed to the increased likelihood of

treatment-seeking as a result of greater medical illness and/or psychological distress

associated with both depression and anxiety disorders (Lenze, et al., 2000).

The most common anxiety disorder co-occurring with geriatric depression is GAD

to have comorbid GAD (Lenze, et al., 2000), and 54% of older adults with GAD found to have major depressive disorder (Gon9alves, et al., 2011). A temporal sequence in comorbid GAD and depression has been found, with GAD generally preceding depression, and GAD tending to progress to depression or mixed anxiety-depression (Flint, 2009; Lenze et al., 2005; Schoevers, et al., 2005; Smits, et al.,

2008).

Co-occurence of late life depression and anxiety . 1s indicative of more · severe ·

psychopathology than if either disorder was to occur alone. Comorbid depression and anxiety in older adults is associated with poorer prognosis with longer time to remission, chronic and recurrent course, greater severity of symptoms, higher suicidality, increased ·autonomic symptoms, longer· response time to anti-depressant treatment, lower social functioning and greater disability· (Beekman, et al., 2000; Lenze, et al., 2005; Lenze, et al., 2000; Mahlman, et al., 201

t

Schoevers, et al., 2005; Steffens & McQuoid, 2005; Wolitzky-Taylor, et al., 2010).burden of disability in older adults, or older people who experience higher levels of

functional impairment are more susceptible to developing depression and anxiety

(Prina, et al., 2011 ).

Treatment of depression and anxiety in older adults

Existing treatment methods for anxiety and depression have been found to be

efficacious to varying degrees in older adults. The aims of treatment of late life

depression and anxiety include symptom reduction, prevention of suicidal ideation,

development of skills clients need to cope with their difficulties, improvement of

cognitive or functional status and prevention of relapse or recurrence of symptoms

(Alexopoulos, 2005; Zisook & Downs, 1998). An overall treatment goal is to

improve the quality of life of the older person presenting with depression and/or

anxiety.

Generally, depression and anxiety in older adults are treated through the use of

pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy, but the most significant gains have been found

when a combination of medication and psychotherapy have been utilised.

Pharmacotherapy

Preliminary evidence suggests that anti-depressants can be effective in the treatment

of both depression and anxiety in older adults (Anderson, 2001; Blazer, 2003;

Katona, 2000; Krasucki, Howard, & Mann, 1999; Wolitzky-Taylor, et al., 2010).

Selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRis) are considered to be the preferred

method of pharmacotherapy for older adults experiencing depression and/or anxiety

because of their efficacy and also because they seem to be better tolerated by older

effective in the treatment of anxiety and depression include serotonin-norepinephrine

reuptake inhibitors (SNRis) and tricyclic anti-depressants (TCAs) (Katona, 2000).

Electro-convulsive therapy (ECT) is also a treatment option for very severe or

treatment-resistant depression and anxiety (Anderson, 2001; Blazer, 2003; Zisook &

Downs, 1998).

Despite the findings that older adults can benefit from pharmacotherapy, they are

also especially sensitive to potential side effects. It is believed . that this

hypersensitivity could be caused by pharmacokinetic changes associated with

ageing, drug interactions, effect on pre-existing medical conditions and the increased

vulnerability of older adults to certain side effects such as risk of falls (Katona, 2000;

Zisook & Downs, 1998). Thus, caution needs to be exercised when medication is

used to treat an older patient.

A combination of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy is considered to be the

optimal treatment strategy for depression and anxiety disorders in older adults, as is

in younger populations (Blazer, 2003; Katona, 2000). Studies have consistently

shown that combined treatment is associated with a considerably lower rate of

relapse than either regimen alone, and that improved prognosis is achievable with

adequate treatment (Blazer, 2003; Katona, 2000; Zisook & Downs, 1998).

Psychotherapy

Psychotherapy, and in particular, cognitive-behaviour therapy (CBT) for the

treatment of depression and anxiety in older people will be explored in detail in

Chapter 6 of this dissertation.

In

general however, a number of psychotherapies havebeen found to be helpful in the treatment of these disorders in an older population.

treatment of both depression and anxiety in older adults (Anderson, 2001; Hendriks,

Oude Voshaar, Keij sers, Hoogduin, & Van Balkom, 2008; Wolitzky-Taylor, et al.,

2010; Zisook & Downs, 1998). Other types of psychotherapy that have been found

to be helpful in the treatment of late life depression and anxiety are interpersonal

therapy (IPT), supportive psychotherapy, family therapy, psychodynamic therapy,

life review therapy and reminiscence therapy (Alexopoulos, 2005; Anderson, 2001;

Blazer, 2003).

Unfortunately, in spite of the existence of efficacious treatments for depression and

anxiety among older adults as discussed above, the problem of under-treatment of

older adults remain. Often, there is a nihilistic view among health service providers

that depression and anxiety are expected products of ageing (Bird & Parslow, 2002;

Unlitzer, Katon, Sullivan, & Miranda, 1999). The detrimental effect of such

erroneous thinking is that older people are at risk of either not being treated, treated

incorrectly or not treated intensely enough for a sufficient period of time. Another

barrier is the exclusion of certain subgroups that are presumed to be unable to engage

in treatment such as psychotherapy; namely older adults who live in residential care.

This group has been largely ignored from existing treatment studies and will be the

focus of this dissertation. Finally, help-seeking behaviour of older adults themselves

will affect whether or not they receive treatment for mental illnesses, and this issue

will be explored in Chapter 3.

Mental health service utilisation among older adults

Despite the fact that effective treatments for late life depression and anxiety exist,

these disorders remain largely undiagnosed ..and untreated (Alexopoulos, 2005;

Zisook & Downs, 1998). It has been reported that no more than 10% of cases of depression detected in primary care will be offered anti-depressant treatment, and less than 1 % will be referred to specialist mental health services (Anderson, 2001 ).

This finding is especially concerning given that it has been well-established that the small number of older adults who seek help for mental health concerns overwhelmingly do so from their general practitioner (GP) rather than directly from any specialised mental health service (Benek-Higgins, McReynolds, Hogan, & Savickas, 2008; Cole, McCusker, Sewitch, Ciampi, & Dyachenko, 2008; Highet,

Hickie, & Davenport, 2002; Park & Unlitzer, 2011; Robb, Haley, Becker, Polivka, & Chwa, 2003). In Australia, the rate of health service use (including GPs, mental

health professionals and hospital admissions) for mental health issues among older adults aged 65-74 was 38.9% and 22.6% among the older-old, aged 75-84 (Burgess et al., 2009). The older-old population recorded the lowest rate of health service use compared to other age groups (Burgess, et al., 2009).

Whilst seeking some help for mental health concerns is better than not seeking any help at all, older adults who seek care almost exclusively from the general medical

sector are denied the opportunity to receive more tailored treatment from specialised

mental health professionals (Crabb & Hunsley, 2006). Unfortunately, the rate of help-seeking among older adults with depression and anxiety disorders from mental health services are low. Studies have found that adults aged 65 and above with

service use for anxiety disorders among older adults was found to be even lower than

that for depression, though the presence of comorbid mood and anxiety disorders

increased the likelihood of help-seeking (Scott, Mackenzie, Chipperfield, & Sareen,

2010).

It is likely that a range of factors contributes to the low rate of help-seeking for

mental illness in older adults despite a well-documented need, and these will be

explored in the next chapter.

Summary and conclusions

Older adults as a group are particularly vulnerable to experiencing depression and

anxiety, due to multiple risk factors. These illnesses can lead to significant distress,

reduced quality of life and at worst, suicide. However, current diagnostic criteria for

depression and anxiety are not sufficiently sensitive to the manifestations of

depression and anxiety in older people and have resulted in significant

under-diagnosis and under-treatment of these disorders. What makes diagnosis even more

difficult in older adults is the high level of comorbidity with other psychiatric

illnesses, physical illness and cognitive impairment, whose symptoms can mimic

each other. Older adults who live in residential care have a combination of all of

these risk factors, but have been overlooked in existing literature and thus will be a

focus of this dissertation. While evidence-based treatment for geriatric depression

and anxiety have been found to be efficacious, access to these treatments seems to be

pa1iicularly problematic, perpetuating a phenomenon of under-treatment of these

disorders among older populations and under-utilisation of mental health services. In

CHAPTER3

Help-seeking behaviour for mental illness in older adults

Depression and anxiety disorders significantly decrease the quality of life of older

adults, highlighting the need for timely detection and treatment of these illnesses.

Despite the existence of evidence-based treatment for geriatric depression and

anxiety and the growing provision of specialist mental health services for older

adults, only a minority of older adults have been shown to access these services, with

the few of those who do seek help preferring to do so from their GP. Specialist

mental health service provision for older people is the first step towards improving

their wellbeing, but ensuring that they are willing and able to access available help is

just as important. Currently there is a wide gap between need and mental health

service use among older people. The reasons for the current pattern of

under-utilisation of mental health services among older adults paint a complex picture, and

range from the attitudes and beliefs that older people themselves have about mental

illness, to misconceptions held by health professionals about what constitutes normal

ageing, to practical issues like the cost of accessing services. Each of these factors

contribute to a perpetuation of under-diagnosis and under-treatment of depression

and anxiety disorders in older adults. These factors can be better understood using

theoretical models of help-seeking behaviour, such as the behavioural model of

health services use (Andersen, 2008) and the theory of planned behaviour (Ajzen,

1991 ). These models and the factors that affect help-seeking for mental illnesses in

Theoretical frameworks

Behavioural model of health services use

Andersen's (2008) behavioural model of health services use (Figure 3.1) highlights the various determinants of health service use by including multiple dimensions of access to care.

Fig. 3 .1 Behavioural model of health services use (Andersen, 2008)

Health

Contextual Characteristics Individual Characteristics Behaviors Outcomes

!

~•

~l

I

PREDISPOSING -ENABLING-NEED PREOlSPOSING -EN.ABLING-NEED Personal Perceived Health Health

o.troogrept,rc 1-!e(i~h Policy . ErwirQflffientiil Demogriiphic Fifllll'lcing Perceived

Practices

I I I I I I

I

I

Sociiil Financing Pcpulatlon

I He~lncf~i f--jll $Qcial Or9ro1~on Evamted -JI

....

l I Process of Evaluated

&.!!iett Otgarillflioo

Beliefs Medical Care Health

-

I

I

Use of Consumer

Personal Satisfaction

Health

Services

i

'•••••,.N.• •. N.'-'·" .•. ".'·'••'-'·'• •• •••. •·.·•h,•N-"CC.'.'.wn,n. .. , , ,.. .,.•.v.•.•.·•· .•; ••• ... _.,_._,.._ . , .. ,_._._._...., ...

[image:42.777.100.667.442.713.2]in tu1n affect future predisposing, enabling and need characteristics of the population and their subsequent propensity to use health services.

Theory of planned behaviour

Ajzen's (1991) theory of planned behaviour (Figure 3.2) seeks to explain as well as predict hwnan behaviour at an individual level, and can be applied to health

behaviour. The theory has been shown to be a reliable predictor of behaviour over time (Armitage & Conner, 1999, 2001) and a central concept of the model is the individual's intention to perfo1m a given behaviour. Generally, the stronger one's intention to engage in a certain behaviour, the more likely that the behaviour will be performed.

Fig. 3.2 The theory of planned behaviour (Azjen, 1991)

Attitude

toward the

[image:43.794.232.642.617.967.2]evaluation of the behaviour in question. The subjective norm describes the perceived

social pressure to engage in or not engage in the behaviour. Perceived behavioural

control refers to the ease or difficulty of performing the behaviour. When an

individual has more favourable attitudes, subjective norms are more positive and the

individual perceives a greater amount of control, their behavioural intention will be

stronger, and in tum increase the likelihood that the behaviour will be performed.

Factors influencing help-seeking behaviour among older-adults

Help-seeking behaviour for mental illnesses in older adults is best conceptualised by

a combination of the behavioural model of health services use (Andersen, 2008) and

the theory of planned behaviour (Ajzen, 1991) (Figure 3 .3).

Fig. 3.3 The integrated model of the theory of planned behaviour (Azjen, 1991) and -behavioural -model of health services use (Andersen, 2008)

Individual characteristics Contertual characteristks Health behaYiours

l

Predisposing

-

I Enabling II

-

II I

·, '

/

(

\\

.!

I I

I I

I I

I I

I I

I I

I I

I I

I I

--.}

, ..•. ~

Attitude

• Mental he.al th lit era cv -·

• Older adulu' attitudetow·ards

help-seeking for mental illness

Subjective norm

• Stigma to,vardsmentalillness

Ptrceived behavioural control

• Knowledge c,favailable mental health s-eni<:es • Perceive.d eaie ofa.ccesBibilitv

to available s-er,ic.e£

Nt.;"'-d

Older adults'

perceiYed need fur f--il> mental health ca.re

\

'\'.

lntention

--.

I

~-.. --~-""_,,,-.

-l

i

Predisposing - : Enabling ... I

Need I

I ;

I I

Attitudes of I I • Referral to I I

Health

I I r---,,

health ,perol.i;t I

I policy

pro fe:;.sional.s menral ~~th ;

regarding

I

about 3er\liC5 I

geriatric Help-~eek:ing for

Availability

geriatric •

mental p.sycholo gical

mental of

pwfmion;Js health iBrue~ healthcare

with geriatric care

I

I menw health

I

I training

I I

I I

Utifaation of mental he.alth ser..ices

---

. ---__ ,...

-~-

-

-

-_..,..~.,,,. ~,II',..,,.

A - ;;.

-~---.;II"

[image:44.775.71.742.689.1120.2]This integrated model not only takes into account the individual and contextual

characteristics that affect help-seeking, but also explores the particular predisposing

and enabling factors at an individual level that influence the underlying mechanism

of intention that can directly predict performance of a health behaviour.

Individual characteristics

Individual characteristics that can influence health behaviours are broken down into

predisposing, enabling and need factors. Predisposing and enabling factors can

together be accounted for by the theory of planned behaviour (Ajzen, 1991). Older

adults' overall perceived behavioural control is shaped by the attitudes that they hold

towards mental illness, their mental health literacy, the level of stigma towards

mental illness they perceive which shapes social norms, their knowledge of available

mental health services and their perceived ease of accessing these services. These

three factors interact to influence intention to seek help for mental illness. A separate

factor that affects an individual's likelihood of performing a health behaviour is the

perceived need for mental health care. These factors will be explored in tum.

Attitudes toward help-seeking for mental illness

An individual's attitude towards seeking help for a mental illness is directly related

to the attitudes they have about mental illness in general, and can significantly

influence their help-seeking behaviour. Negative attitudes about mental illness in

older adults have been found to be associated with a lower willingness to seek

psychological help (Segal, Coolidge, Mincic, & O'Riley, 2005). These negative

attitudes have been found to be more common in older cohorts, who historically have

,

experienced difficult life events like the Great Depression and the Second World

own compared to later-born cohorts (Cunin, Hayslip, Schneider, & Kooken, 1998; Mackenzie, Scott, Mather, & Sareen, 2008; Morano & DeForge, 2004). Older adults who have more negative attitudes towards mental illness have also been found to

attribute more personal responsibility towards the cause of the illness and thus seeking help is seen as a personal weakness (Segal, et al., 2005). For instance, older

people have been found to believe that anxiety is not a serious illness, and avoidable

if one looks after oneself (Webb, Jacobs-Lawson, & Waddell, 2009). Consequently,

older adults believed that their peers who experienced anxiety disorders were more responsible for their condition, viewed more negatively than those experiencing

depression or schizophrenia and that they should 'just get over it' (Webb, et al.·, 2009). Personal attribution for the cause and therefore coping with depression was strongly endorsed by older adults from ethnic minority groups, and could account for the low rates of mental health service use among older adults from ethnic minorities (Lawrence et al., 2006).

Negative attitudes towards mental illness among older adults have been associated

with negative attitudes to ageing, where health problems tend to be attributed to 'old age' rather than illness (Quinn, Laidlaw, & Murray, 2009; Sarkisian, Lee-Henderson, & Mangione, 2003). One study found that 4 7% of the older adults sampled

considered ageing a likely cause of depression (Webb, et al., 2009). In another study, depressed older adults who attributed depression to ageing were 4 times less likely to

discuss feeling depressed with their doctor than those who associated depression

with illness (Sarkisian, et al., 2003). This finding strongly supports the notion that

attributing mental health conditions to normal ageing leads to older adults' not receiving required care. It has been suggested that loneliness and dependence may be