Rochester Institute of Technology

RIT Scholar Works

Theses

Thesis/Dissertation Collections

5-1-1997

An Investigation into the growing popularity of

script typefaces and the technical means by which

they are created today

Yacotzin Alva

Follow this and additional works at:

http://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses

Recommended Citation

Rochester

Institute

ofTechnology

SCHOOL OF PRINTING MANAGEMENT

AND SCIENCESAn Investigation

into

the

Growing Popularity

of

Script Typefaces

and

the

Technical

Means

by

which

They

are

Created Today.

A

thesis project submittedin

partialfulfillment

oftherequirements

for

thedegree

ofMaster

ofScience

in

theSchool

ofPrinting

Management

andSciences

oftheCollege

ofImaging

Arts

andSciences

oftheRochester

Institute

ofTechnology

Yacotzin

Alva

Thesis

Advisor: David Pankow

Technical

Advisor: Archibald Provan

School of Printing Management and Sciences

Rochester Institute of Technology

Rochester, New York

Certificate of Approval

Master's Thesis

This is to certify that the Master's Thesis of

Yacotzin Alva

With a major in Graphic Arts Publishing

has been approved by the Thesis Committee as satisfactory

for the thesis requirement for the Master of Science degree

at the convocation of

May, I997

Thesis Committee:

David Pankow

Thesis Advisor

An

Investigation

into

the

Growing

Popularity

ofScript Typefaces

and

the

Technical

Means

by

whichThey

areCreated Today.

Acknowledgments

I

wouldlike

to

expressmy

appreciation tothe

people whohave been

a great supportduring

the completion ofthis research.Especially,

I

wouldlike

to extendmy

sincerest gratitudeto

David

Pankow,

Curator

oftheCary

Graphic Arts

Collection,

for

theassistance and guidance thathe

has

given me.I

wouldalsolike

to thankProfessor Archie

Provan,

andthe typedesigners

who returnedTable

of

Contents

List

ofTables

viAbstract

viiChapter

iIntroduction

iHistory

of scriptfaces

2Precursors

3

*

Development

of scriptfaces

nTechnical

considerations14

Endnotes for Chapter

1 16Chapter

2Review

ofliterature

in

thefield

ofstudy

17

Chapter

3

Methodology

20Chapter

4

The

influence

oftechnology

21Digital

toolsfor

typedesign

22Ikarus

22Metafont

23

Fontographer

23

FontLab

23

FontStudio

24

Chapter

5

Script

typeface classification 26Script

typefacedefinitions

28Joined

scriptfaces

30Unjoined

scriptfaces

41Endnotes for

Chapter

5

83

Chapter

6

Questionnaire

results and conclusions84

Conclusions

91Endnotes for Chapter

6

93

Chapter

7

Recommendations

and suggestionsfor further

study

94

Appendix

1Index

oftypefaces95

Appendix

11Index

ofdesigners

101Appendix

inIndex

oftypefoundries

109

List

of

Tables

and

Figures

Table

i:Latin

alphabetletterform

styles anddates

of popular use3

Figure

i:Roman

capitals ofthe

Trajan Column

5

Figure

2:Capitalis

quadrata5

Figure

3:Capitalis

rustica5

Figure

4:Uncials

5

Figure

5:Half-uncial

6

Figure

6:

Insular

script7

Figure

7:Carolingian

minuscule8

Figure

8:

Bastarda

10Figure

9:Gothic

book

hand

10Figure

10:Humanistic

cursive 10Figure

11:Edward Johnston

handwriting

12 [image:8.552.58.521.150.414.2]Abstract

The

examination ofany

current type specimenbook

invariably

discloses

alarge

number offaces

designed

toimitate

someform

ofhandwriting.

Strictly

speaking,

suchdesigns

areknown

asscripttypes.

It

is

a matter of opinion which typefaces shouldbe

classified asscripts,

especially

since allearly

typedesigns

werederived

from

writtenforms.

Today,

wetypically

label

atypeface as a scriptif it

retains thelook

ofhaving

been

writtenwitha pen or otherwriting implement.

Type

specimen catalogues ofthe nineteenthcentury

list

numerous examples ofsuch writtenforms,

though thesearemostly

restrictedto stylesdeveloped

by

theseventeenth-and

eighteenth-century writing

masters.Modern

scriptsdiffer

from

those ofthelast century because

ofabewil

dering

variety

of structuresderived from forms

createdby

different writing

instruments,

includ

ing

thebroad-edged

pen,

the steelpen,

and thebrush.

In

addition to such traditionalsources,

morerecent scripts

have been inspired

by

thefelt-tipped

marker, pencil,

ruling

pen,

ball

pointpen and even thespray

paint can.For

this thesisproject,

theauthorpreparedahistorical introduction

andthenattemptedto classify

asmany historic

andcontemporary

scriptfaces

as possiblein

order todetermine how

typedesigners

arebreaking

newgroundin

the structure ofthesefascinating

letterforms.

Many

recentscript

faces

areradically different

from

traditionalmodels,

while some explore thevery

limits

ofstyle,

legibility,

and technicalfit.

Such

experimentation wouldhave been

much moredifficult

in

the

days

when types were castfrom

metal or evenwhen types were madefor

photocompositiondevices.

Today,

thenumber andvariety

of scriptfaces

areincreasing

at arapid ratedue

toimprove

mentsin

computer typedesign

software.Therefore,

this thesis project also reviews some ofthepowerfultype

design

software anddigital

technology

now available which allowdesigners

to

create types of greatoriginality.Also

included

are the results of a questionnaire sentto selected contemChapter

1

Introduction

For

6,000

years,

humans have

communicated throughwritten symbols.The

evolutionof an effective

symbol setfor

a particularlanguage

orlanguages,

from

the earliestpictograms to our currentalphabet

(in

theWestern World

),

wasdriven

by

aquestfor

simplicity

andefficiency.For

centuries,

handwritten documents

were theprimary

means ofrecording human

endeavor;

surviving

examples afford us awindowto the past.

The

basic

design

elements or structuralforms

ofthelatin

alphabetwe usetoday

were established

during

theItalian Renaissance

andby

the end ofthefifteenth

century.The

elegant andpractical

letterforms

ofthistime

were the products of along

evolution andderived

part oftheircharacter

from

thebroad-edged

pen.These

letterforms

had

asweeping influence

onhow

textswere created and

led

to the creation of roman anditalic

types aswell as the scriptfaces

thatweuse today.

As

soon astheseforms

werefixed

in

metal,

therewaslittle

chancefor

aradicaldepar

ture

from

the"norms"

established

by

the printer and the typefounder. Personal

communication,

however,

was still carried on throughhandwriting;

a newprofession,

that ofthewriting

master,

was

already

establishedby

theearly

sixteenthcentury

andcorrespondents and record-keepers weretrained

in

themost elegant styles.By

theearly

seventeenthcentury,

with the establishmentof copperplateengraving

as a meansof

reproducing letterforms

andillustrations,

formal

handwriting

had

evolvedtoemulatethekinds

of

lines

madeby

the engraver's pointedburin.

The

pointed pen soon replaced thebroad-edged

pen,

giving

rise to a style ofhandwriting

known

as copperplate.For

the next300years,

avariety

of pointed-pen

handwriting

styles were practicedby

professionals and amateurs alike.The

handwriting

oftoday

is

a mixture ofstyles,

written with awidevariety

ofinstruments. It

is

aneveryday activity

with resultsranging

from

aswiftly

scrawleddisposable

note to afine

pieceofcalligraphy.

Whether

one writesin

atraditionalorunconventionalmanner,

aformal

orinformal

style,

one'spersonality,

intellect,

and mood often shine through.Ultimately,

theprimary

purposeHistory

of

Script

faces

Script

types,

because

they derive

from

a profusion ofhandwriting

styles,

aredifficult

to

organizeinto

atidy

classification scheme.Even

theword"script"

is

hard

to

define

sinceit

meansdifferent

things to

different

people;

thus

thesimplestdefinition

mightbe

to

declare

thatthey

are typefacesmade

in imitation

ofhandwriting.

However,

since alltypefaces

canbe

tracedback

tohandwrit

tenorigins,

a more precisedefinition

is

required.To

begin

with,

there arefour

general stylisticclasses oftypes thatpredominate

in

thewesternhemisphere:

roman,

italic, decorative,

and script.i.)

Roman

types arebased

on theinscriptional

capitals usedin

Roman

monuments and on theCarolingian

minuscule.In

general,

roman types came tobe

preferred overblackletter forms in

Europe

andAmerica,

thoughboth

werederived from

a common origin.For

thatreason,

thisstudy

will notinclude any

scriptfaces based

onblackletter

structures.A

separatestudy

ofblack-letter

scripts,

however,

wouldbe

wellworthwhile.2.)

Italic

typeswerefirst developed

by

Francesco

Griffo

da

Bologna

in

1501for

theVenetian

printerAldus Manutius

andwere usedfor

printing

pocketbooks

ofthe classicsfor

the use ofhumanist

scholars.

This

early

cursive oritalic,

asit

was called almosteverywhere,

was animitation

oftheCancellaresca

corsiva usedin

Italy

at thattime.

Italic

types soon were used as companions toroman

types;

theirshapes are calm alongside theclear,

serious and uprightroman.23.)

Decorative

typesaremuchfreer

in

design,

sometimes so muchso astobe

barely

recognizable.The

good printer usesthem

sparingly

to

addinterest

to

atitlepage orto grab the attention of areader.

4.)

Script

typesderived from

thosehandwritten letterforms

and styles thatpersisted and evolvedlong

after thedesigns

ofromananditalic

forms had

been

fixed.

It

is important

tobear

in

mind thatwereonly

types oftheearly

sixteenthcentury

tobe

considered,

it

wouldbe difficult

todistinguish between

italic

and scriptfaces.

The

Chancery

hand for

example

first developed

in

Italy

during

thefifteenth

century,

and characterizedby

the calli graphic styles ofAxrighi,

Celebrino, Amphiareo, Tagliente,

andPalatino

was acursive,

someAldus

Manutius

ofVenice.

This

newtype

ofAldus

served as themodelfor

many

subsequentitalic

faces.3For

the purposes ofthis thesis

then, it is

important

to emphasize that thoughitalic

andscript

faces

share a commonorigin,

thelatter

arepredominantly designs

thatdeveloped along

with changesin writing

instruments,

techniques

and tastes.Precursors

All

scripttypefacesgrewout ofpre-Gutenberg

inscriptional

lettering

and manuscriptbookhands

and

it may

be

usefultobriefly

reviewthemhere.

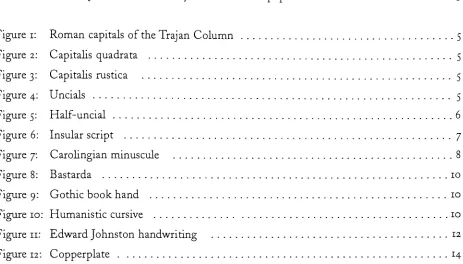

Table

ibelow

provides abrief

chronological summary

ofthebasic

stylisticdevelopments

in

thelatin

alphabet since thefirst

century

a.d.Square Capitals

ca. 1-500Rustic Capitals

ca. 1-500Uncials

ca. 300-900Half-Uncials

ca. 400-900Caroline Minuscule

783-1000Gothic

ca. 1150-1500Bastarda

ca. 1200-1500Humanistic

ca.1400-Cursive Humanistic

(Italic)

ca.1400-Copperplate

ca.1600-Foundational

1916TABLEI.LATIN ALPHABETLETTERFORM STYLES AND DATES OF POPULAR USE4

Up

to about1450,

handwriting

wasused to reproduce allforms

oftext,

from

informal

notesto

book-length

manuscripts.With

thedevelopment

oftheprinting

press,

however,

handwriting

wasincreasingly

relegated to personal communication andrecord-keeping.Each

ofthestylisticforms

[image:12.552.123.410.305.554.2]Square Capitals

orCapitalis Quadrata

areplainly

relatedtoearly

Roman

carvedinscriptional

let

ters and can

be

seen attheir

finest in

the

famous

inscription

(114

c.e.)

at thebase

oftheColumn

of

Trajan

in

Rome.

Square Capitals

attemptedto

imitate

thecapitalletters,

derived from

the technique of

chiselling,

by

turning

the penin

a certainway

that an exaggerated contrastbetween

thickandthinstrokes was created.

"Stone inscriptional

carving

was ahighly

developed

craftin

Rome,

asemperors wished to

immortalize

their

deeds

anddeclare

theglory

ofthe empire.All facets

ofimperial inscriptions

were planned and executedwith the goals ofclarity,

legibility,

andbalance."5These formal

letters,

also calledmajuscules,

may

alsohave been

reservedfor

thefinest

manuscripts.Though Square

Capitals

weregenerally

reservedfor

monuments,

scribesbegan

to use a compactscript

known

asRustic Capitals

(1-500

c.e.)

These

arefreer,

compressed,

andeconomical.First

seenin

a papyrus manuscript ofthefirst

century,

Rustic

Capitals

survived untilthebeginning

ofthesixth century.

"When

compared toSquare

Capitals,

a vertical compression oftheletters is

obvious.

Diagonal

strokes thathad been

seen straightwere nowcurved,

such as theA, X,

andV;

thelatter

looked

almostlike

aU.

The

G, O,

andQ_became

more elliptical."6The

thin strokes thatcharacterizethese

letters

suggestthat thepen orbrush

usedmay have been

cut withaleft-oblique

edge

giving

theimpression

that theletters

wereinfluenced

by

pen andink

usedspecifically

onpapyrus or parchment.

Rustic Capitals

movefurther

away

from

theRoman

capital stylethroughits

condensedform.

Only

twoknown Christian

manuscripts,

oneby

Prudentius

andthe otherby

Sedulius,

were writtenin

Rustic Capitals.

Both

styles wereusedin

theRoman

period asbook-hands

and went out of styleby

thesixthcentury

but

werelater

revivedin

Carolingian

times

wherethey

werebasically

usedfor

tides,

headings,

andbegin

ningsof chapters.

Another

book-hand,

theUncial,

seenin

the oldest copies oftheBible,

had

evolvedby

the endofthe third

century

andthebeginning

ofthefourth

century

and wastheliterary

hand for fine books

from

thefifth

to the eight centuriesin

certain parts ofEurope. It

owesits

form

to the quill pen andto thevellum substrate.

The

pen makes roundedforms

easily;

theseroundedletters

supplanted theangularones ofthe earlier

capitals.7

specific script style was attached to them.

Uncials

were stillaround in800

c.e.,wherethey

served asheadings in

manuscripts written in more"modern"

scripts.

During

thefifth

and sixth centuries,the spread of

Christianity

allowed thediffusion

ofboth

uncial andhalf-uncial

scripts as themajormonastic hands.3

All

threeforegoing

scriptsbelong

to thefamily

ot"formal"

hands.

Figure

1.Roman

capitalsof

theTrajan Column.

The

shapesiftheclassicalRoman

capitalcopiedfaithfully

from

thebest

charactersof

theTrajan

column inscription.VELAMENACAN

VOTAFVTVRAE

DESCITQVETVEl^

Figure

2.Capitalis

quadrata.Fragment of Virgil's Sangallensis.

jrd or 4th century.

iVONUSiN-MONUS'

ViaVliOiKOi&LCK

VI-LlNVS-KAEGtLLi-D

Figure

j.Capitalis

rustica.6th

century.The dots have

perhapsbeen

addedlater

andareintended

toindicatetheworddivisions.

<\Iiut

ikjsu;v pjequi si

INKC&US

hum\Nis

Figure

j.Uncials.

[image:14.552.41.230.256.538.2]Literate Romans did

notusually

writein

theformal book hand.

A

roman cursive or informalhandwriting

was usedby

most people who wrote their correspondence on wax tablets or papyrusin an

everyday

cursive script.This

cursivewriting

wasdeveloped from

theformal

capitals,but

there was a tendencywhenwriting

quickly

to make theletters

in

a moredirect

and economicalbut

less

precise manner andled

to considerabledeviations from

thecapitals,

changes that weredeveloped gradually

-withoutaffecting

the scripts immediately.Differences

in writing

instrumentsand materials also caused scriptto evolve.

The

letters

producedby

scratching

the surface of a wax tabletwill nothave

the same character andform

as those writtenby

quill on vellum or papyrus.ltis

from

the cursive scripts ofthefirst

three centuries ofChristianity

that mostof our smallletters

or minuscules trace their origin.

A

modifiedform,

mixture of uncial and cursive script resultedin

thedevelopment

ofthefirst

minuscule script called

Half-Uncial,

which appearedin

southernEurope,

particularly

inItaly

andFrance,

andquickly

gainedpopularity,

marking

a significantstep

forward

in thedevelopment

of the modernRoman

alphabet.The

half-uncials

were importantfor

thedevelopment

ofwriting

because

ofthe ascenders anddescenders

on some ofits characters.The

smallletters fall between

four

imaginary

horizontal

lines,

instead

oftwo,

because

oftheextensions of certainletters:

b, d,

f

h, k,

and1

whichhave

ascenders,

andg,

j,

p,

q,

andy,

whichhave

descenders.

These

hybrid

forms

appeared

in

thefifth

century

and thrivedin

thesixth.Half-uncials

couldbe

written morerapidly,

and morewords couldbe

written perpage.Cursive

script anddocumentary

hands influenced

thehalf-uncial

script more than the uncials themselvesdid.

They

where used as abook-hand

andcould

be

considered animportant link between

Roman

cursives and vernacularhands.

eRajLTinapicnsquasi

au

"Each

monasticscriptoriumdeveloped

its

own variations on uncials andhalf-uncials,

withinfluencesfrom

cursive anddocumentary

hands

oftheir ownprovinces.''9

Such

scripts areknown

asNational

Hands.

Between

the sixth and the ninthcenturies,

theIrish

scribesdeveloped

what isknown

asthe most importantnational

hand,

theInsular

script.They

canbe identified easily

by

theirclarity

and

elegance,

by

thethickening

oftheserifs,

thewedge-shaped tops oftheascenders,

andby

thecurve in some ofthe vertical strokes.

It

is considered tohave

reached itshigh

point ofdevelop

mentin the

Book

ofKells,

anoutstanding

example oftheInsular

script,

in

Trinity-College

Library,

Dublin.10

The

Visigothic

script orTote

tana wasdeveloped

in the seventhcentury

inSpain. The

pen wasused in a vertical

form

andthe scriptbecame

laterally

compressed anddecorative.

A

page writtenwith this script was

very

ornamental,

but lacked

thelegibility

oftheInsular

script.All

the nationalscripts evolved

from

thelater

Roman

cursive and thetendency

to transform it into abookhand.11

mdueRcucmrouajbusTiru^-ps

^^^biceboGjas

cjuocurngu^ii^ii^j^

us ruclomum iUjcinan6j&-"QbwG(

lecrjojcheRiutT-aos<

Tx^TTicajiurnttb--^*.'

^cexjurjcs

iUj pi*cmdi033bcriJU~iiE-Tf

)o<rrnceuaccrn

a^r^za^toterrio.

[image:16.552.153.429.386.635.2]vna.jTH]tea:ifX]()a3JU^cuTJ8f25ajK/bCeD

Figure 6. Insular

scriptThe

gentle,

roundedCarolingian

minuscule,

amedievalbook

hand

alsoknown

asLittera

Galhca

orScrip

turaFrancisca,

wasdeveloped

as a reaction against the ornamental characters of the nationalhands

that prevailedduring

the seventh and eighth centuries.They

developed

as the result ofachange in calligraphic taste

in

Frankish

conventsduring

the ninthcentury,

under the influence ofa

Quarter-Uncial

that appeared at about the same timein

northernItaly.

The

Carolingian hand

later became extremely

important as a guidefor Renaissance

humanists.

It

is

not certain whetherthe

Carolingian Minuscule

(named

afterCharlemagne)

arosefrom

amixture ofcursives andhalf-uncial,

but

its clearletters

wontor

it a proud placein

thehistory

ofthe scripts.Its

earliest versionappeared

berore

7S5,

m thededication

oftheGospel Book

ofCharlemagne

writtenby

aFrankish

scribe called

Godescalc. It

remainedthedominant

scriptin

Europe

untilabout theyear 1000.The

Carolingian

script wasdeveloped

bv

theEnglish

scholarAlcuin,

who standardized itsforms

andsupervised itsuse

in

Charlemagne's

publishing

projects .Alcuin

was responsiblefor

the productionof

many

manuscripts that utilized whatis known

as theCarolingian

minuscule,

andhe is usually

credited with

formalizing

this script.The

Carolingian

minuscule spread and was soon adoptedfor

writing

all religiousbooks,

thenfor

secularliterary

works andlegal documents.

The

principle ofthe

Carolingian

script,

underxAlcuin'sdirection,

fixed

the vertical proportions oftheletter

forms,

which

had become

exaggeratedby

extremely

elongated ascenders anddescenders in

the nationalhands.12

menxi

*rcxdr>m Con

fuLarrr

ft

ae-fr

duortarrr

2cpudfbrnctipfofirmiff

"By

the eleventhcentury,

capitalization oftheinitial

andimportant

wordsbegan;

it became

more common

in

thethirteenth

century,

and wasfixed

in

the

sixteenth.The

spreadofCarolingian

minuscule as an authoritative script

in

the ninthcentury

throughFrance, Germany,

andNorthern

Italy

guaranteedits

success internationally."13The

variety

offaces

whichdeveloped

in

the eleventh tofifteenth

centuries constituted thelast

phase of

invention in

the periodpreceding

the standardization effectedby

thecasting

ofprinting

types though

both

calligraphicproduction of manuscripts and thedevelopment

ofpenmanship

as a

fine

art werefeatures

ofthepost-Gutenberg

era."As

the scriptbecame

more compressed andthe nib ofthe quill pen was cut

wider,

theletters

assumed ablacker

and more angularaspect."14

The

Blackletter

scripts oftheMiddle Ages

(sometimes

calledgothic)

comefrom

Carolingian,

thechangedshapesofthe

letters

being

due,

amongst other possiblereasons, to

lateral

compression orto atendency

to make roundedletters

somewhat angularwhenwriting

thehand

toofreely.

It

offersa

striking

contrastto the earlierforms,

since theblackletter

became

aprecise, angular,

compressed,

black,

ornamentalletter,

thoughlacking

thepracticality

ofits

clear andfreer

ancestor;

atits

worst,

it

waslifeless

andhard

to read.Blackletter

scriptswere characterizedby

theirlack

of curves andemphasizedverticals and straight

lines.

For

threecenturies,

blackletter

scripts werepredominant.They

were atits

best

in

thethirteenth

century in

France. Its

many

versionshave been

given names such aslettre

batarde,

black

letter,

fraktur,

rotunda,

and so on.The

Bastarda

orlettre

batarde,

acursiveform

oftheblackletter

script,

appeared after

1200,

in

manuscriptsfor university

studies,

for

government and commercialdocu

ments,

andfor

vernacularliterature.

The

scholars wrote this scriptfaster,

giving it

theimpression

of

being

lighter

than the standardblackletter. The

term"gothic" sometimes usedto

describe

this

style,

is derived

from

thename oftheperiod of arthistory

in

whichthis

script was popular.During

the transitional periodknown

as theItalian Renaissance

characterizedby

the enthusiasmdis

played

for

the remains ofantiquity,

for

thestriving

for

spiritualfreedom,

andfor

the scientificrediscovery

ofthe world and of man so-calledhumanists

sawnothing

spiritualin

blackletter

scripts and

instead

revived theforgotten

works ofthe classicLatin

authors whichthey

found

in

various

monasteries,

libraries,

etc.,

writtenin

theCarolingian

minuscule ofthetenth

and eleventh centuries.They

also assumedit

was much older thanit really

was andtherefore

calledit

Littera

Antiqua.

The

clearwriting

ofthe classics accordedwith the spiritofthe"new

birth,"

adopted the earlier

hands for

their own usage.Through

rapidwriting,

the uprightRenaissance

handwriting

gradually came to slopein

thedirection

of the writing.These

rapidly

writtenCarolingian hands developed

into

theHumanistic

cursive.By

the middle ofthefifteenth

century,

humanistic

replacedblackletter forms

as the standard scriptfor

the classics.Humanistic

scribes attempted to eliminate most ofthe abbreviations andligatures

usedin

theearlier scripts.

The humanistic

scriptlooks

similar to theCarolingian

minuscule,but its

charac ters are more even andregular,

eliminating differences between

thickand thin strokes andmaking

the

letters

more closelyspaced.Figure

8.Bastarda.

Western Upper

Bavaria,

14J2.[Tffloimosjglrtqtms

a

smug

hottuheg

ftjhtffl

Figure

9.Blackletterbook hand

Wurzburg,

middleof

therjth century.rvwm quod

partim

vro vwlwntat?

cuDevelopment

of

Script

Typefaces

With

theintroduction

ofprinting

in

the1450s,

writing

abook

by

hand

was nolonger

necessary,

and

few

lengthy

manuscriptbooks

were madein

thesixteenth century.Though

blackletter

scripts were thebasis for

typefaces

in

Germany

and other parts ofEurope for

a certainperiod,

romantypes

from

Italy,

based

onhumanistic

hands,

eventually

replaced theblackletter

throughout most ofEurope.

Handwriting

became

a skillto

use oncorrespondence,

officialdocuments,

commemo rativecertificates,

and the occasionalbook.

The

italic,

thesupplementary

sloping

type usedby

printersfor

the purposes of contrast andemphasis,

is

derived from

a more cursive variant ofthe revivedCarolingian

letter

and owesits

simplerform

to thetendency

ofthehand

to seektheeasiercourse andto avoiduneconomicalpen-lifts.

A difference between

roman anditalic lowercase

typesis

that theformer derives

from

aformal

hand

whilethelatter derives from

a cursive.Fluency

is

helped

by

theuse oflinking

joins,

particularly

those of adiagonal

kind,

but

not allletters

arejoined.

The

slope and compression ofitalic

letters

are alsocursive characteristics.The

clarity

and convenience ofthehumanistic

cursivehand

led

toits

useboth

as abook-script

andfor

correspondence.Its

adoptionin

thePapal

Chancery

for

thewritings ofbriefs

musthave

contributedtoits

acceptancein

European

countries.A

moreflourished

versionofthescript cametobe

termedasLittera de brevi

orLittera Cancellaresca

in

Italy,

theofficial scriptin

thepapal chanceries and recommended asageneralhand

by

chancery

scribeLudovico degli Arrighi

in

his

manual onhandwriting,

La Operina.

It

wasin

1522 thatArrighi,

awriter ofapostolicbriefs

aswell as aprinter, scribe,

anddesigner

ofitalic types,

produced thefirst writing

manualto

deal

withitalic

handwriting.

The

pages oiLa

Operina,

printedin

1522from

engravedwood-blocks,

offerinstruction in writing

andillustrate

thebeautiful

Cancellaresca

hand.

Another

very

popularwriting-book,

by

G. A.

Tagliente,

contains even morescriptsandalphabets,

and appearedin

1524.In

1540,

G. B. Palatino

publishedavaluable treasury

ofscripts.Similar books

appearedin

other countriesincluding

France, Switzerland, Spain,

the

Netherlands, Germany,

andEngland.15The

end ofthe sixteenthcentury

and thebeginning

of the seventeenthcentury

marked thebetween

theirtypefaces

andbook

typography.

In

Pans,

Louis Barbedor

wrote with a cursivewhosewords as well as

letters

were connectedin

astyleknown

as ronde inFrance

andRound Hand

in

England.

English

writing

masters werelovers

of cursives italics and penflourishes.

The

copy-books ofthe secondhalf

oftheeighteenthcentury

and those ofthe nineteenth century

showhands

in

which the copperplate style predominated.The hairlines

are oftenexceedingly

fine

and theshading

calledfor

carefully

controlled pressures ofthe pen.By

the end ofthe eighteenthcentury,

elaborate scripttypefacesweredeveloped,

among

others,

by

Giambattista

Bodoni,

who includedmany

ofthemin his

specimenbooks.

Not

until the nineteenth

century

however,

did

typefoundries

begin

to release numerous scriptfaces based

onflow

ing

handwriting.

Many

of them werebased

on calligraphichands

influenced

by

copperplateengraving

styles.These

soonbecame

widely

usedin advertising

designs,

while othersbecame

themainstay

ofsocialprinting,

while still otherswere usedfor formal

andlegal documents.

Toward

theend ofthe nineteenth

century,

scripts that showed more contrast were released andin

some caseswere accompanied

by

bold

and outline versions.Handwriting

was atits

lowest

ebbby

the end ofthe nineteenthcentury,

but

a renaissancein

modern

calligraphy

was made possibleby

Edward

Johnston,

whosehandwriting

developed in

stages,

going

from

thehalf-uncial,

Carolingian

minuscules and compressedblackletter

to a sixteenth-century

italic

whichhe

named"heavy

italic."

Between

1916 and1919

he

created theFoundational

script which wasbased

onalate

Carolingian

scriptfrom

atenth-century

manuscriptwritten

in

Winchester.

This

scriptbecame

one of the standards thatlater

calligraphers wereencouragedto master.

His

influence

on moderncalligraphy

wasprofound.16Owe

nw

npyjctuhp^Mlorqiud-f

My

Jtaffof

faith

io

wall<ub07is/

[image:21.552.173.402.551.649.2]Type founders

had

madeintermittent

attempts topopularizedisplay

scriptsfor

many

years,

but

not until the

late

nineteenthcentury did

they

began

to see extensive use.Many

ofthesedisplay

scripts were

in

essencethe

degenerate descendants

ofthe mid-nineteenthcentury faces.

The first

distinctively

contemporary

display

scriptto

obtain acceptance was calledHolla,

designed

by

Rudolf Koch

in

1932.This

typeface

is

sometimes cited as thedirect forerunner

of most ofthecharacteristic

informal

display

scripts oftoday,

and opened a newfield

ofdesign

based

ondifferent

treatments of pen and

brush

techniques.

A large

number ofnewscriptdesigns

wereinfluenced

by

Koch's

innovation.

Throughout

the twentiethcentury,

famous

typedesigners

and typefoundries

released aflood

of scripts which were

based

onletters

originally

handwritten

withpens, pencils,

brushes,

and moreradical

instruments,

many

ofthemfashioned

tosatisfy

the needs of modern advertising.Recendy,

numeroustypefaces

inspired

by

handwritten

scriptshave

appeared,

andthey

continueto reflect the age-old

desire

to capturethepersonality

and spirit ofthehandwritten

word on thepage,

suggesting

that ourincreasingly

technicalsociety

has

notlost

its

appetitefor

fine

aswellasinformal

handwritten

letterforms.

The

variety

of structures characteristic of modern scripts separates themfrom

those ofprevious

centuries,

whichis

due

primarily

to theuseofnewanddifferent

writing instruments.

One

canonly

guess at whatthenextcentury

willbring.

For

now,

thediversity

ofwriting

styles overthepastcenturies resists attempts to arrange script types

into

a consistent classification scheme.A later

Technical

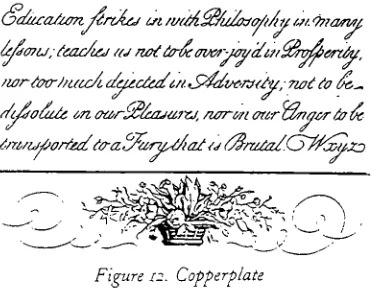

Considerations

Most

ofthe pre-twentieth centuryhistoric

scriptsmay

be divided

into

two categories: thebook-hands,

writtenwith abroad-edged

pen,

and the copperplate-hands,wntten with aflexible

pointedpen.

The

edged penmay

be

aquill,

areed, or a metalpen,

as used today.The

edgemay be

straightor oblique.

The

strokes naturallyproducedby

theedged pen are athickstroke as wide as the pen'sedge, a thin stroke

(hair-line)

atrightangles to the thickstroke,

andintermediate thicknessesand gradations governedby

thedirection

ofthe stroke and the angle ofthe pen.Curved

strokeshave

gradations of mathematical regularityThe

eighteenth-and

nineteenth-century

commercialhands

require aflexible

pointed penheld

so that thedown

stroke employs enough pressure tosplay

the points ofthe pen.Seemingly,

theaim was to

imitate

thestrokes thecopperplateengraving

toolproduced.Therefore,

it

couldbe

said that thepen was not masterinits

ownhouse.

The

hair-line

ofanearly

corsiva or chanceryletter

was madeby

a sideways movement ofanedged

pen,

whilst thehair-line

ofthecopperplate-hand

resultedfrom

a release of pressure on thenib.

Both

kinds

ofup

strokes are producedby

natural andeasy

movements.Not

so natural andeasy

are the uniform gradationsofthe copperplate-hands.6ci/uca//j7?zJ%rt&<y

ui wMffiuZttv/i/iu/j/.foamy,

u/diaru^azcAcjtu net'dtrtx ow'ycyai'wz&au'ertdu,

norfar//utc/i.c/cxcc&dt/i

S^diK'tttty,

7wtto <fc-r/t&toui6st-n(Mrc/aijuizj,narwi ortr (3nt7J>rtovcFigure

12.Copperplate

With

the exceptionof traditionalcopperplateformal

scripts,

there arefew,

ifany

scriptdesigns

inbefore

Formal

became

[image:23.552.187.374.437.583.2]to

formal

copperplatedesigns

were availablein

theuprightFrench

rondetradition,

but

theiruse wasequally limited

andthey

werelargely

overshadowedby

the

morefamiliar

inclined

scriptsin

the

nineteenth-century

copybooktradition,

whichderived from

the models ofthe eighteenth-century writing

masters,

such asMonotype

Dorchester

Script,

issued

in

1938.For

centuries, typefounders

have

triedto

imitate

handwriting

in

metal type.Script

faces,

particularly

joined

ones,

were not commonduring

theperiod when typewas castin

metalbecause

oftechnical

limitations

encounteredthroughout

theprocess.As

opposed tohandwriting,

where thehuman

hand

caneasily

introduce

awidevariety

offorms

onthepaper,

metal type mustoccupy

astrict three-dimensional space.

Each

character requires the creation ofits

ownmatrix.1'

Alternative

versions of certain characterswerealso cutaswere alltheligatures

requiredfor

a scriptfont.

The

mostdifficult

problem to solve concerned thekerning

oroverhanging

portions oftheletter

whichhad

to matchperfectly in design

and physical space withevery

otherletter

it

mightEndnotes

for Chapter

i.

Adobe

Systems,

Sanvito.

A

Two-Axis Multiple

Master Typeface

(California: Adobe

Systems

Inc.,

1993).2.

Albert

Kapr,

The Art of

Lettering.

The

History, Anatomy,

andAesthetics of

the

Roman Letterforms

(Munich: K.G.

Saur,

1983),

327-329.3.

Max

Caflisch,

"On

theHistory

ofScript

Typefaces,"

Font

& Function

15

(1995):

4.4.

Leda

Avrin,

Scribes,

Scripts

andBooks. The Book Artsfrom

Antiquity

to theRenaissance

(Chicago: American

Library

Association,

1991),

178.5.

Ibid,

178.6.

Ibid,

181.7.

Alfred

Fairbank,

A Book ofScripts

(Baltimore: Penguin

Books,

1968),

8.

8.

Avrin,

183-184.9.

Ibid,

185.10.

Johanna

Drucker,

The Alphabetic Labyrinth. The Letters in

History

andImagination

(London:

Thames 8c Hudson

Ltd,

1995),

96-98.11.

Kapr,

40.12.

Drucker,

100.13.

Avrin,

190. 14.Ibid,

192.15.

Erik

Lindegren,

ABC of

Lettering

andPrinting

Types

(Sweden:

Lindegrens

Boktryckeri

AB,

1976),

72.16.

Avrin,

200.Chapter

2

Review

of

Literature

in

the

Field

of

Study

The

following

abstractsdescribe books

thatwereparticularly helpful

in

thecompletionofthis thesis project.A

completelist

ofbook

andjournals

consultedfor

thisprojectis

containedin

thebibliog

raphy

at the end.A Book of

Scripts,

by

Alfred

Fairbank.

(Baltimore,

Maryland: Penguin

Books,

1968)

This

textwas writtenby

a prominenttwentieth-century

British

calligrapher and contains muchinformation

on the origins of script styles.It

covers a widerange,

from

thebeginnings

of theromanalphabetto

mid-twentieth-century

calligraphic styles.This book discusses

theimportance

ofthesecalligraphic

hands

and provides animportant

classification scheme.It

also contains alarge

number of examples so that the readermay distinguish between

thedifferent

script styles.This

book is

agood place tobegin

research.Scribes,

Scripts

andBooks. The Book Artsfrom

Antiquity

to

theRenaissance,

by

Lefla Avrin.

(Chicago:

American

Library

Association,

1991)

This

book

provides a completehistory

and progressofletterforms,

demonstrating

theirdevelop

ment

before

and throughoutthe age ofprinting.It

is

animportant

book

and a complete source ofinformation

for

anyoneinterested

in letterforms.

A Manual

of

Script

Typefaces,

by

R. S.

Hutchings.

(London:

Cory

Adams

ocMackay,

1965)

This

book

provides a goodintroduction

to the script types thatwere availablein

metalup

to theyearofpublicationand

includes

somenotes on thehistory

of script typesand their main charac teristics.The

author states that"typographers know

whatthey

meanwhenthey

speak ofscripts,

but

most ofthemwouldfind

it difficult

to

define

theterm

precisely

to

anyone unfamiliar withthe

broad

field

oftypeAnatomy

of

aTypeface,

by

Alexander Lawson. (Boston: David

R.

Godine,

1990)

Written

by

Alexander

Lawson,

anauthority

ontypeface

history,

thisbook

documents

a series offamous

types,

theirdevelopment

anduses,

their

antecedents and theirimportance,

with precisionand clarity.

Though

it

does

notdeal

with scriptfaces

directly

(almost

all ofthe typesdiscussed

areromans),

Lawson's book

is

enormously

helpful for

its

extensivebackground

information.Lawson

states that thisbook

is

"not

writtenfor

the printer convinced that there arealready

toomany typefaces,

but

ratherfor

that curious part ofthepopulation thatbelieves

theopposite;

thatthe subtleties of refinement as applied to roman and cursive

letters have

yet tobe

fully

investigat

ed andthat theproduction oftheperfecttypefaceremainsagoalto

be

as muchdesired

by

presentas

by

future

type designers."ABC of

Lettering

andPrinting

Types,

by

Erik Lindegren. (Sweden:

Lindegrens

Boktryckeri

AB,

1976)

This

book

provedto

be

animportant

sourcebecause it carefully

describes

thehistory

oftypefaces,

including

scriptfaces

andtheir connection to manuscriptbookhands.

With

its

thoroughdescrip

tion

ofcharactershapes and types ofcurves,

thisbook

becomes

avery helpful

toolin

determining

the

"genealogy"

of various

designs.

"On Script

Types,

"in

Selected Essays

onthe

History

ofLetter-forms in Manuscripts

andPrint,

by

Stanley

Morison. (Cambridge: Cambridge

University

Press,

1981)

This

is

one ofthe mostthorough studies of scripttypes

yet made.In

particularit

describes

thesefaces

in

theirhistorical

context andprovides comparison withitalic

types.The Art

of

Lettering.

Its

Mastery

andPractice,

by

Helm Wotzkow. (New York: Dover

Publications,

Inc.,

1967)

This

book is

apractical guideto theartofhand-lettering.

Wotzkow

gives advice on thespecialtools

whichare

necessary

tohand-lettering,

continuing

with ananalysis ofthedifferent

characters.This

elementary

(such

asthe

selection ofthe

drawing

tools)

to numerous professional considerations."To learn

how is

certainly

notalways tolearn

why,

but

to

know

why

is

the surestway

oflearning

how

andfinally

knowing

how."

The Art of

Lettering, History, Anatomy,

andAesthetics

of

the

Roman

Letterforms,

by

Albert

Kapr.

(Munich: K.G.

Saur,

1983)

This book

provides a completehistory

ofwriting

andlettering,

including

astudy

ofthe transitionofcharacters and the

development

ofthe alphabet.The Complete Font Software Resourcefor Electronic

Publishing,

by

Jeff

Level,

Bruce Newman

andBrenda

Newman.

(New York: Precision Type

Inc.,

1995)

This

is

one of the more complete catalogs of the typefaces availabletoday

in digital

form. It

includes

more than 13,000fonts from

almostsixty

different

sources.It

is

considered one ofthemost comprehensive

font

referencebooks

ever produced.American

Metal Typefaces

of

theTwentieth

Century,

by

Mac McGrew. (Delaware: Oak Knoll

Books,

1993)

This

book

coversevery known

typeface thathas been

designed

and castin

metalduring

the

twentieth century in

America. Detailed descriptions

of eachface,

including

designers,

foundries,

dates

of

issue

andsizesareincluded along

with anillustrated

version of thefull

alphabet.It

is

animportant

source

for

anyoneinterested in

type.Encyclopedia of

Typefaces,

by

Jaspert,

Berry

8c

Johnson.

(London: Bath

Press,

1983)

This

is

a majorinternational

referenceessentially

concerned with metaltypefaces,

designers

andtheir sources.

It

includes

a wide selection offaces

arrangedalphabetically

underthree

main secChapter

3

Methodology

1.

A

history

of scripttypefaces

wasprepared,

including

theiroriginsin

manuscriptbookhands

andsubsequent

development

aftertheinvention

of printing.This

background

researchwas conductedin

books

andjournals,

andthrough

correspondence with various typehistory

authorities.2.

A

carefulstudy

was made ofthe powerful typedesign

software anddigital

technology

nowavad-able to

determine

how

modern softwaretools enabledesigners

to create typesof great originality.3.

Extensive

researchin

typefoundry

specimens generated samplesfor

thecatalog

ofscriptfaces.

These

were classifiedby

meansof a systemdeveloped

by

theauthor,

but

because

oftheirhuge

number,

thecatalog

does

notinclude

allexisting

scriptfaces.

Each

typeface sampleis

accompaniedby

the name ofits

designer

and year of creation(where

known).

4.

An

important

aspect ofthis thesisinvolved contacting

selectedcontemporary

typedesigners

tosolicittheir opinions and views on various

issues

relatedto the proliferation of scriptfaces.

Contact

was madein

various ways:by

letters,

by

electronicmad,

and person-to-person.Each

designer

who agreedto participate received a questionnaire.Their

responseshave been

summarized

in

Chapter

6

ofthis

thesis.The

contemporary

typedesigners

who completedthequestionnaire are:

John Benson

Richard

Beatty

Tobias Frere-Jones

Robert Slimbach

Chapter

4

The Influence

of

Technology

The huge

increase in

the number oftypeface

designs

over thelast century

or sois very

much aresult oftechnical

developments

in

the typemanufacturing

process.Major

technologicaldevelop

ments

have

changedthe practice oftypedesign

andincreased

theproduction ofthem.Before

theprinting

press,

books

were producedby

scribes.The

process ofwriting

abook

by

hand

was alabor-intensive

one,

which remained true until theinvention

of movable typein

themiddle of the

fifteenth

century,

attributed toJohannes Gutenberg.

Minor

refinements to thesequence of

cutting

a punchfor

eachcharacter,

striking

a matrix andcasting

from

it in

ahand-mold were added

from

thelate

1400s to thelate

1800s,

when theindustrial

revolutionbrought

major

innovations

toprinting

technology.Typesetting

was transformedby

theintroduction

oftheLinotype

(1885)

and,

soonafter,

Monotype

casting

machines.The punch-cutting

method changeddramatically

with theinvention

ofthe pantographmachine,

developed

by

Linn Boyd Benton in

1884,

andlater

adapted to cut matrices.At

last,

type couldbe

designed

on adrawing

board

andtranslated

directly

into

matrices without the technical and economic restrictions ofengraving

apunch

in

metal atits

actualsize.1Another

innovation,

alliedto the

growth of offset-lithographicprinting,

was thedevelopment

of

phototypesetting

afterWorld War II. The

matrixfor

the type was nolonger

abrass

die but

aphotographic negative.

Without

theeconomic constraints of metal typeproduction,

typefaceproduction

was neithercostly in

termsoftime

norin

terms of capitaloutlay.Although

often still usedto

describe

"post-metal"

composition,

photosetting is

now amisnomer;

typeis

nowgenerally

stored as mathematical

formulas

in digital

form (a

techniquefirst

introduced

by

theGerman firm

of

Hell

in

1965),

andis

outputto

either paper orfilm

coated withan emulsion of silver via a cathode

ray

tube(crt)

orlaser

output device.2In

thevery latest

developments,

type canbe

outputdirectly

to

aplate orimaged

onto adrum

in

adigital

press orprinting

device.

An

important

breakthrough in

typedesign technology

started around 1973.The

earliest comdevices.

Each device had

its

own commandlanguage

and some ofthese

devices

are stillin

service.The Apple Macintosh

computer wasintroduced

in

1984

as alow-cost

personal computer with auser-friendly

"interface";

soon the "Mac"developed

into

a comprehensive graphicdesign

andtypesetting

toolbecause

ofits

immediacy

andflexibility.

Many

ofits

original virtueshave

nowbeen

echoed on thePC

platform as well.Using

digital

types

in

PostScript format (now

suppliedby

allmanufacturers),

the

Mac

andPC have

taken

typesetting

away

from

traditionaltypesetters

and put

it in

thehands

ofdesigners (and

everyoneelse),

thus

de-mystifying

thewhole productionprocess.

More

recently,

withthe

arrival oftype-designing

programs,

everyonehas

theopportunity

to

design

type.The

result ofthis

newdemocracy

is

visiblein

thework ofmany contemporary

typedesigners,

whosefonts have

startedto

change perceptions and chadenge accepted notions ofbeau

ty

andlegibility.3DIGITAL

TOOLS FOR

TYPE

DESIGN

Digital

typesetting

has brought

newopportunitiesfor

the creation oftypefaces.

There

arefive

major software packages avadable

specially

designed

to create typefonts:

Ikarus, Metafont,

Fontographer,

FontLab

andFontStudio.

Ikarus

The

Ikarus

system wasdesigned

by

Dr.

Peter Karow

ofURW

in

Germany

for high

quality

anddevice-independent

digital

imaging

andmanipulation.The

system,

usedby

many

typefoundries,

sets the standard

for

quality in

typedesign

and production.Models

canbe

createdby

scanning,

autotracing

orimportation

from PS

Typel

andT3

fonts. Ikarus

can produce multiplekern

andwidthtables

for

textsetting,

as well asfor

thetouching

andoverlapping

display

typeusedin

high

ly

specializedadvertising

typography.Ikarus has

15,000 x 15,000 unitsto

the em which ensuresmaximum

accuracy

and ahigh level

ofprecision and control.For autotracing

capabilities,

Ikarus

needs a separate program called

LinusM.

The

first

typeface producedfor

electronic compositionfrom

theIkarus

system wasMarconi

in

1977,

designed

by

Hermann

Zapf

the previous year andMetafont

Designed between

1977-1979

by

Donald E.

Knuth,

a professorof computer science andprofessor

ofelectricalengineering

atStanford

University.

Metafont

is

the

name ofahighly

portablefont

generation systemthat readstext

files

prepared with"programs"

which

specify

the outline ofcharacters

in

fonts,

graphicalsymbols,

or other elementsfor printing

high quality documents.

Typesetting

systemslike TeX

make use ofthefont

metricinformation

producedby

Metafont

andprinter

devices

of screen previewers make use ofthe pixelinformation

to print.It

is

consideredanalgebraic

programming

language

specificady developed

for

typedesign. Each

characteris

defined

as a sub-program.

In

its

optimumform,

it is

parameter-driventypedesign

software,

meaning

thevarious characteristics ofthe

image

(weight,

width,

cap-height,

x-height, etc.)

canbe

specifiedpriorto

font

generation.Metafont,

is

most usefulfor

thegeneration of an entirefamily

ofrelatedfonts. Latest

version:2.71.4

Fontographer

In

1985,

Altsys

Corporation

introduced Fontographer for

theMacintosh. It

was thefirst

outline font

editorfor

any

personal computer.It

wasdesigned

tomodify existing fonts

or create newfonts from

scratch.Fontographer has

theflexibility

ofbeing

used onboth

Window

andMacintosh

platforms.

Having

gone throughseveral upgradesin

thelast

tenyears,

thelatest

version 4.1 contains over 200 enhancements to the previous one.

It

encouragesfont

experimentation,

allowing

the creationof

lighter

andheavier

versions ofexisting

fonts

andbuilding

newfonts

by blending

between any

twofonts

on the system.The

pressure-sensitive and calligraphic pen tools providemany

unique opportunitiesfor

thedesigner.

It

providesauto-hinting,

kerning,

andauto-tracing

capabilities

for

fitting

outlines ofscannedimages. Fontographer

is

themost popularfont

editorin

the world

for

personalcomputers."

FontLab

FontLab

wasdesigned in

St.

Petersburg, Russia,

in early

1990by

SoftUnion. FontLab

2.0 wasintroduced commercially in

1993,

upgradedtoversion2.5

in

1994,

whileversion 3.0wiUbe

releasedin 1997

andwiUbe

thefirst Windows-based Multiple Master digital

typeface editor.FontLab

is

andmodification

functions. It

is

adigital

typeface editorfor

theWindows

environment.It

is

usedto create, modify,

enhance orsimplify

Type

1

orTrueType

fonts

andincludes

two utilities:i)

ScanFont,

by

SoftUnion

usedfor auto-tracing

andconverting

TIFF

files

into

font

charactersIt

is

a picture andfont

converter and canbe

used to putanything

scannableinto

font

format.

It

imports

and exportsboth

TrueType

andType

1

fonts,

converting

obsoleteformat

fonts

toType

1

and

TrueType formats.

2)

FindFont,

by

SoftUnion

is

usedfor searching fonts

by

user-defined selection criteria.FontStudio

FontStudio

is

producedby

Letraset. It

is

the second mostpopularfont

editoron theMac

withan

elegant,

intuitive

userinterface.

It

contains ad thenecessary

drawing,

measuring,

scaring

andother standard

functions.

Untd

therelease ofFontographer

4.0,

FontStudio

wasthebest-designed

Endnotes for

Chapter

4

1.

Norman Walsh

(Ed). (1992-1996).

A

BriefHistory

of

'Type.

[Homepage

ofThe Comp.

fonts

FAQ],

[Online].

Available:

http://www.ora.com/homepages/comp.fonts/FAQ/cf_28.htm

2.

Ron Eason

andSarah

Rookledge,

Rookledges International

Directory

of Type

Designers.

A

Biographical

Handbook

(New

York: The

Sarabande

Press,

1994): xix-xx.3.

Norman Walsh

(Ed).

(1996-last

update).Digital Type

Design Tools.

[Homepage

ofTheComp.

fontsFAQ],

[Online].

Available:

http://www.Hb.ox.ac.uk/internet/news/faq/archive/fonts-faq.part6.html

4.

Nicholas Fabian

(Ed). (1994-last

update).Digital Toolsfor Type Design

[Homepage

ofNicolas

Fabian],

[Online].

Available:

http://webcom.net/nfhome/digital.htm

5.

James Felici (Ed). (1994-last

update).Fontographer

4.0.4.

[Homepage

ofMacWorld

Communications, Inc.],

[Online].

Available:

Chapter

5

Script

Typeface

Classification

As

indicated

by

thelarge

selection ofexamplesincluded in

thisclassification,

today'sgrowing

number of script

types

cadsfor

a revaluation oftheir placein

typedesign

history

aswell as typeclassificationsystems.

One

has

only

to turnthe pages ofcontemporary

magazines and newspapersfor

confirmationofthe

popularity

andvariety

of script types.Here

and there a smart stylizedline

orphrase shows adistant relationship

toformal

types, but

for

the most partentirely

new conceptionsbased

uponfreely

renderedbrush

or pentreatments

have

evolved.These

strongly

personalizedforms

aredic

tated

by

the caprices oftheletters,

andinfluenced

by

theliberties

orlimitations imposed

by

lay

out conditions.

More

andmore thesehmits have

been

lifted

so thattoday'sdesigners

often reachnew

heights

ofabandon.Under

suchcircumstances,

it is

moredifficult

toclassify

scripttypes;

they

are

potentially

as numerous as themany

different

kinds

ofpersonalhandwriting,

oftendefying

ready

classification andorganization.1The

fodowing

scripttypefaceclassification wasbased

onanexamination of as

many

scriptfaces

as possible.By

studying

type specimencatalogs,

it

was possible

toobtainmany

more samples thanoriginady

expected.There

were alsomany

cases where thesametypeface appeared under

different

namesin

typefoundry

catalogs.The

fodowing

classificationis

based

on a personal opinion andis dlustrated

with the mostimportant

and currentfaces.

In

many

cases,

however,

theauthorwas required to exercise substanCLASSIFICATION:

JOINED

pageFormal

... 30Ronde

35

Freestyle

.... 36Monotone

. . 38Inline

.... 40UNJOINED

Formal

41Informal

47

Civilite

52Chancery

53

Freestyle

55

Monotone

70Inline

78Script

Typeface Definitions

JOINED.

Joined

scriptsare thosein

which adlowercase

charactersjoin

onewith each other.UNJOINED.

These

include

thosetypefaces

where one or morelowercase

charactersdo

notjoin

withthe

foflowing

character.FORMAL.

Joined

orunjoined script typefaces createdwithgreat care and particularattention todetads

andlegibility.

Each

characteris

elegant and wedbalanced.

INFORMAL.

Unjoined

script typefaces with a casuallook,

evoking

afriendly

andinformal

quality.They

often express a morelively

personality.CIVILITE.

Unjoined,

upright scripttypefaceswith ornamentalflourishes.

RONDE.

Joined,

upright scripttypefacesderived from

theCivilite

anddecorated

with ornamental