1

Do Financial Expert CEOs Matter for Newly Public Firms?

D. Gounopoulos, P. Loukopoulos and G. Loukopoulos

1This draft: December 1, 2018

Abstract

In this paper we analyse the relation between financial expert CEOs and the long-term viability of Initial Public Offering (IPOs). We uncover strong evidence that IPO firms run by financial expert CEOs have a lower probability of failure and longer time to survive in the aftermarket. In an attempt to identify the underlying causes of this relationship, we find that CEOs with a career background in finance get better access to the IPO market, as evidenced by lower absolute revisions during bookbuilding and a lower amount of money left on the table. In addition, they exhibit lower volatility in the immediate after market, stronger stock market and higher operating returns. Taken together, our results show that financial expertise is a crucial factor in determining the success of an IPO.

JEL Classifications: G3, G10, G14

Keywords:Initial Public Offerings, Financial Expert CEOs, IPO Survival

1

Dimitrios Gounopoulos (corresponding author) is from the University of Bath, E-mail: d.gounopoulos@bath.ac.uk

Panagiotis Loukopoulos is from the University of Strathclyde, E-mail: panagiotis.loukopoulos@strath.ac.uk

2 1. Introduction

Do CEOs matter? A burgeoning recent literature aims to understand the role that chief executive officers (CEOs) play in the firms they run (see Bertrand, 2009 for a review). In this respect, a variety of studies on CEO-specific heterogeneity considering either specific personality traits (e.g., Kaplan et al., 2012; Graham et al., 2013; Malmendier and Tate, 2008; Malmendier et al., 2011; Hirshleifer et al., 2012) or career experiences (Malmendeir and Tate; 2005; Custodio and Metzger, 2014; Custodio and Metzger, 2014), show that managerial background plays a crucial role in shaping management styles and has important implications for firm performance.

Despite the conceptual interest on whether CEOs meaningfully affect corporate policies and value creation, much of prior work has focused on large, well-established organizations. However, much less is known about the manner in which CEO heterogeneity affects young, entrepreneurial with substantial growth opportunities. Are the future prospects of these firms contingent on the manager’s skill set? If so, does this relationship depend on the type of the CEO’s functional background? Or should it be ignored under the traditional assumption that rational decision makers behave identically if faced with the same problems?

To shed light on these questions, we explore how CEOs with past experience in finance-related roles affect the survivability of firms that undergo an Initial Public offering (IPO). Because a financial oriented background in the part of CEO provides access to cheaper financing, IPO firms headed by financial expert CEOs will better cope with environmental challenges and possibly to better capitalize post-issue growth opportunities (Custodio and Metzger, 2014). However, financial experts are worse innovators and seem to have skills which are less valuable for companies being at an early stage in their life cycle (Custodio and Metzger, 2014) or at high-growth industries (Hoitash, et al., 2016). Therefore, given growing importance of a knowledge-based economy in young ventures, IPO issuers will need easy access to the equity market as well as superior innovation capacity, in order remain competitive. As such, we cannot provide a clear-cut prediction on the net effect of financial

expertise on IPOs. 2

We start our analysis by establishing a novel empirical finding: companies with CEOs who have prior work experience either in banking and investment firms or in finance-related roles are exposed to lower failure risk (i.e., delisting probability) than their counterparts. Survival analysis of U.S data on 1,167 IPOs over 2000-2012 indicates that the risk of delisting due to negative reasons of

2

3

IPO issuers with a financial expert CEO is 30.8 % of the delisting risk of firms with a nonfinancial expert CEO. A better sense of economic magnitude, though, is provided by accelerated failure time (AFT) model, as it shows that, on average, the survival time of firms headed by a financial expert CEO increases by 25.72 months. Notably, these results are robust to several sensitivity tests, including alternative definitions of financial expertise, IPO failure, and industry time-invariant effects.

Although we would like to view our findings as evidence for a direct effect of financial expertise on firm viability, our results could simultaneously reflect observed and unobserved omitted personal or firm characteristics correlated with financial and real outcomes. To deal effectively with this type of bias, ideally, would like to consider fixed-effects specifications either at the firm or CEO level, or both. However, this is infeasible in our context, given that every firm goes public only once. Nonetheless, to alleviate some of these concerns, we include in our baseline models an array of additional variables that allow us to control for executive talent, general work experience, the structure of business operations, as well as the quality of corporate governance mechanisms. Results from controlling for observable heterogeneity at the CEO and firm level are consistent with our based survival analysis: we document a negative correlation between financial expertise and IPO failure.

To address with unobservable heterogeneity, and hence with spurious correlation between our measure of financial expertise and some other unobservable superior skills, we conduct an indirect test: we investigate whether financial expert CEOs receive higher total compensation than nonfinancial expert CEOs. We find no significant differences results along these lines. This finding provides some assurance that financial expertise does not merely capture other potentially important skills for the CEO position. Most importantly, it helps us to rule out the possibility that financial specialist CEOs might self-select firms close to their preferences, as otherwise they would be willing to accept a lower remuneration.

Even if our proxy measures superior financial skills satisfactory, there are still two possible interpretations of the documented negative relationship between financial experience of the CEO and IPO survival. One interpretation is endogenous matching of CEO and firms. Endogenous matching suggests that financial expert CEOs tend to be hired by particular firms that demand a superior financial skill set. For example, firms with a need to raise external capital to fund their growth may choose to hire a CEO with financial experience for this purpose. Alternatively, a career path in finance may not be part of the selection criteria in choosing a CEO. Under this scenario, the imprinting of financial training exogenously affects executive decisions, and therefore exerts a direct influence on corporate policies.

4

CEO-firm matching occurs either because the firm believes that the CEO might be crucial in implementing specific financial policies or because she can imprint a personal style on corporate decisions that is value enhancing. Custodio and Metzger (2014) exploit a sample of seasoned firms provide evidence of assortative CEO-firm matching based on the life cycle of the firm and the career background of the CEO. Similarly, in our IPO sample, we demonstrate evidence of CEO matching based on the firm’s business model, as indicated by a higher representation of financial expert CEOs in firms that are less inclined to innovative technology products (i.e., firms with low concentration in the internet and technology sector and in Nasdaq).

Notwithstanding the above, evidence from a matching estimator based on observable differences between firms with and without financial specialists as well as from a two-stage Heckman approach provide added confidence for a causal interpretation of our findings. Importantly, additional analysis based on the timing of CEO hiring indicates that, even if the choice of the new CEO is endogenous, it does not drive our results, as the negative impact of financial sophistication on IPO failure is not limited to recently appointed CEOs; rather, it extends to CEOs with tenure of at least 4 years.

Although the preceding discussion provides a coherent set of results supporting the view that financial expertise matters in young, entrepreneurial and fast growing firms, it does not illustrate how exactly it might enhance the survival of firms that plan to go public. Toward this end, we perform a vast set of exploratory tests to evaluate the contribution of financial expert CEOs’ actions and decisions at a micro-level. Specifically, we hypothesize that financial expert managers affect IPOs through two channels: reputation and ability. The reputation effects arise because financial specialists are repeat players in the financial markets, and hence they may be more effective in certifying and communicating the issue than nonfinancial experts (Chemmanur and Paeglis, 2005). Likewise, they have powerful motives to price the equity fairly, as their future career path is dependent of potential deliberate mispricing attempts (Chemmanur et al., 2009). On the other hand, the ability channel suggests that the financial sophistication in the part of CEO permits the firm to make informed investment decisions (Custodio and Metzger, 2014).

5

conservative initial offer prices, lower offer price changes, reduced underpricing, and eventually a greater amount of proceeds. As expected, our tests provide strong empirical support to these conjectures.

In our second set of exploratory tests, we examine the role that financial expertise might play in the aftermarket. Consistent with the notion that it reduces the valuation asymmetry surrounding the offering, we find that the financial expert CEOs display lower stock return volatility. In addition, we show that either due to either lower investor heterogeneity or irrational pricing, financial expertise relates positively with future stock market performance three years after the IPO. In an attempt to more fully understand why financial expertise affect the perceptions of investors in the aftermarket, we find that these CEOs face lower termination risk and have higher subsequent accounting performance. Finally, we show that they follow aggressive financial policies, while they restructure the firms’ operations inorganically, i.e., via acquisitions.

Our work is related to a growing literature in finance and economics that highlights the importance of the person in charge of an organization, as exemplified by Bertrand and Schoar (2003). This literature usually takes on of two approaches. The first approach studies the corporate implications of CEO-specific heterogeneity by focusing on personal characteristics (e.g., Malmendier and Tate, 2008; Kaplan et al., 2012; Graham et al., 2013; Benmelech and Frydman, 2015), whereas the second approach explores whether the type of the CEO’s work experiences (e.g., Custodio et al., 2013; Badolato et al., 2014; Custodio and Metzger, 2014; Bernile et al., 2016).

Perhaps, most comparable to our work is Custodio and Metzger (2014), who analyse the role of financial expert CEOs. They focus on seasoned firms and show that financial specialists engage actively in cash and leverage policies, and are mostly beneficial in companies that are at a later stage in their life cycle. We complement and expand the findings of this study along the following dimensions. By focusing on the IPO setting, we demonstrate that, while superior financial skills come at the cost of a skill-set that is particularly relevant for young, entrepreneurial firms, they still exert an economically meaningful and lasting effect, as they enable companies that are typically at earlier life cycle stages to survive for a longer time. In addition, we point out that financial specialist CEOs do not only engage in conventional financial policies such as the management of cash holding and leverage, but also play a surprisingly integral role in the firms’ most important financing decision, namely, going public for the first time.

6

on the interaction between CEO financial expertise and IPO underpricing. In this regard, our study is closely related with Chemmanur and Paeglis (2005). This study utilizes information on demographical, education, and governance characteristic at the board levels and demonstrates that top management reputation and quality plays a certification role in IPOs. Unlike this study, we focus solely on the CEO, and document a prominent role for the CEOs’ functional expertise in IPO performance as well.

The paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 describes the data and then main methodology. In section 3, we establish the importance FE for the survival of IPOs, while in Section 4 we discuss identification and alternative interpretations in detail. In Section 5, we examine the mechanism that allows FR CEOs to perform better. In Section 6, we identify environments in which CEOs’ abilities are particularly important. We conclude in Section 7.

2. IPO sample, Variables Description and Methodology

We obtain our initial sample of IPOs from the Thomson ONE Banker database from 1st

January 2000 to 31st January 2012. Following prior literature, we impose the following restrictions: (1) the offer price is at least five dollars a share, (2) the IPO is not a spin-off, a privatization, an American Depository Receipt (ADR), a unit offering, a rights issue, a leveraged buyout (LBOs), a real investment trust (REIT), a limited partnership, a closed end fund, and a financial institution (SIC codes 6000-6999). We extract financial statement information from Compustat database, stock prices and delisting information from the University of Chicago’s Center for Research in Security Prices (CRSP). After merging the databases and eliminating observations with missing values, our final sample consists of 1,167 sample IPOs.

7 2.1 Sample Description

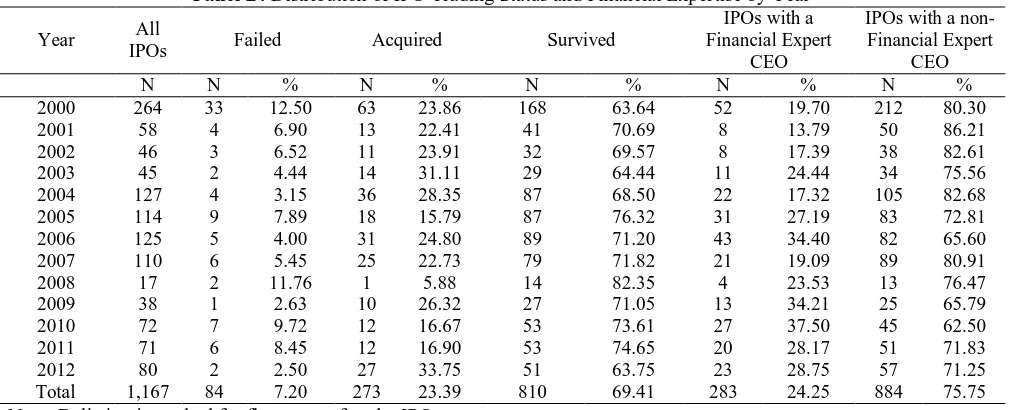

Table 1 presents the distributional characteristics of our sample IPO firms. Panel A categorizes the IPOs based on the trading status from 2000 to 2012. Tracking for five years after the issue date, 69% of the firms survived (i.e., were non-delisted or exchanged), 24% were acquired, and 7% were failed (i.e., dropped or liquidated).

Panel B shows the distribution of IPO activity and trading status by issue year. There is a clustering of IPOs in 2000 and around 2004-2007. The dot-com bubble in 2001 and the more recent financial crisis in 2008 considerably reduced the number of IPO deals being initiated during 2001-2003 and 2008-2009, respectively. The percentage of failed firms within five years after the issue is highest for firms going public in 2000 and 2008, which is consistent with the notion that economic crises have an adverse impact on the firms’ survivability. The proportion of firms being acquired in five years after the issue is highest for IPOs in 2012 (34%) and lowest for those in 2008 (6%). As for the survived firms, more than half of the firms survived for five years after the IPO, and this percentage ranges from 63% (2012) to 77% (2008).

Panel C displays the distribution of IPO activity and delisting rates by two-digit SIC code industry. The majority of IPOs are concentrated in industries that develop high technological products including chemical products, computer equipment and services, and electronic equipment. The highest percentage of failed firms is found in the entertainment services (15%), whereas computer equipment and services and scientific instrument are the industries with the highest (lowest) percentage of acquired firms (29% and 27% respectively). In all industries, the majority of IPOs survived for five years subsequent to the initial stock offering and ranges from 62% to 85%.

Panels B and C also illustrate the proportion of financial expert CEOs’ by year and by industry. The percentage of IPO firms with a financial expert CEO exhibits a considerable variation in our sample period and takes the lowest values during the global financial crisis (2007-2008). Regarding the industry distribution of CEOs’ with financial experience, it is worth noting that, the financial expert CEOs with the largest representation can be found in in oil and gas and computer equipment and services sectors, whereas in entertainment and product manufacturing industries are the lowest number of financial expert CEOs.

8

financial industry and auditing firms or in a financial role in a nonfinancial firm.3 The work histories

of financial specialists CEOs typically include experience in around 1.5 firms and positions. 84% of financial specialist CEOs has gained financial experience in another firm, while the tenure of such experience is approximately 5.40 years. Looking at detailed finance experience, we see that among the CEOs with financial or accounting experience 28% have worked as a CFO, 20% as a (investment) banker, 8% as an auditor, 6% as an accountant, 10% as a treasurer, 9% as a VP of finance, and 19% in other financial roles.4

Panel B shows descriptive statistics on CEO characteristics. The CEOs are overwhelmingly male (88%). The typical CEO in our sample is 49 years old, and has been managing the firm for around 4 years. 32% of the CEOs are firm founders, while 55% are also the chairman of the board. In terms of compensation, a CEO earns annually an average of $1,3 million and the most of this consist of cash compensation (salary and bonus). In addition, 4% of the CEOs hold a professional qualification in finance and/or in accounting, while approximately 20% of the panel has a university degree in some level (undergraduate, master, or doctorate) of financial education, e.g., an MBA, or an economics or business-related degree, of which 15% were obtained from an Ivy League institution.

Financial experts CEOs differ mainly from nonfinancial experts in terms of tenure, founder status, the number of board-roles undertaken, the degree of exposure to international experiences and the graduates from an Ivy League institution. Particularly, financial expert CEOs tend to have less time in the office at the time of the IPO and a lower probability of being the founder than nonfinancial expert CEOs. In contrast, the percentages of CEOs holding dual positions as a CEO and a chairperson, and of those with an international background (either in terms of ethnicity or education), are significantly higher for the sample of IPOs with a financial expert (41% and 36%, respectively).

Unlike Custodio and Metzger (2014), we observe no significant differences between financial experts CEOs and their counterparts in terms of academic or professional education (4%), and career path (previous work experience). Additionally, we do not find any significant differences in total CEO remuneration. As discussed later, this finding indicates that in our sample, financial specialist CEOs do not have preferences for firms with particular characteristics, as otherwise they would tolerate a relatively low compensation in order to run a firm that matches their preferences.

3

Custodio and Metzger (2014) report a substantially higher percentage of financial expert CEOs (41%), though, it should be kept in mind that they argue that CEOs with financial expertise prefer large, seasoned firms, i.e., firms at mature stages of the firm life cycle. In subsequent sections, we evaluate the extent to which our results are subject to such selection bias.

4

9

Panel C illustrates firms and offering characteristics for all IPOs, IPO firms with and without a financial expert CEO. On average, IPO firms are 15 years old and have total assets of $0.7 million. In general, 35% of IPOs are underwritten by top-tier underwriters (investment banks), 47% are audited by Big Four audited firms, and 53% are ventured-backed. In addition, IPO firms have a mean leverage ratio of 34%, 30% of total assets is invested in R&D. and only 5% is directed to capital expenditures, while the incidence of positive earnings per share is 50%.

Compared to IPO firms with a nonfinancial expert, those with a financial expert CEO have similar age or size. Nonetheless, they manage to achieve higher offer sizes. Also, they differ in terms of pre-IPO investment policies before the IPO, as they invest more in tangible and intangible assets. Furthermore, it is interesting to note, that firms with financial expert CEOs tend to have lower underpricing, are less venture-capital backed, and attract more prestigious underwriters, as opposed to firms with nonfinancial expert CEOs. We observe no significant differences in the remaining variables.

2.2 Methodology

2.2.1 Survival Analysis Methodology

To investigate the impact of IPO firms with financial experts we employ survival analysis as it is a statistical technique for analyzing the expected duration of time until one or more events happen (such as the death of a public firm) and has been used extensively in prior research to examine determinants of IPO survival (e.g., Jain and Kini, 2000; Carpentier and Suret, 2011; Alhadab et al., 2014; Buchner et al., 2017; Gounopoulos and Pham, 2017).

The main advantage of survival analysis compared to the other methods (e.g., ordinary least squares and the tobit or probit models) is that it allows us to take into consideration the survival time of each firm. It is also very useful to censored data (e.g., IPO data), i.e., delisting evens that have not yet occurred or have different survival horizons. Therefore, in our case we use the Cox proportional hazard model and estimate the following model:

( ) ( ) (3)

10 2.3 Control Variables

We include various firm, CEO, and offerings characteristics as control variables that are suggested by prior IPO literature as important determinants of pre and post-IPO performance. Gounopoulos et al. (2018) find that firms with high compensated managers have lower failure risk. We also control for CEO power using the CEO tenure, duality and whether CEO is also the founder of the firm. Han et al. (2016) suggest that entrenched CEOs perform worse than non-entrenched CEOs, and as a result we expect that firms led by powerful CEOs are less likely to survive. Additionally, we use offer size (proceeds) to control for the company size and underpricing as issue characteristic. For instance, in contrast to the seminal study by Hensler et al. (1997), Espenlaub et al. (2016) documents that underpricing is negatively related survival time.

With respect to risky investments, we use as controls R&D and capital expenditures. Demers and Joos (2007) suggest that firms with high leverage are associated positive with the failure risk. In addition to that, Gounopoulos and Pham (2018) find that firms with positive earnings have higher probabilities of failure. Thus, we account for the impact of firms’ financial policies by using firm leverage and earnings per share (EPS). To capture the maturity of the firm, we utilize firms’ age and measure it as the date since its incorporation to issue date. Furthermore, Bhattacharya et al. (2015) suggest that VC-backed companies with top-tier underwriters have lower mortality rates, while Espenlaub et al. (2012) do not find a significant effect of venture capitalists. Following these studies and to control for the financial and accounting intermediaries, we include Big 4 auditor, VC, and underwriter. Finally, to alleviate any concerns that our results are driven by any specific industries, we use dummy variables to control for the presence of internet and technology firms.

3. Empirical Findings

3.1 Estimation of the Cox Proportional Hazards Model on Financial Expert CEO

11

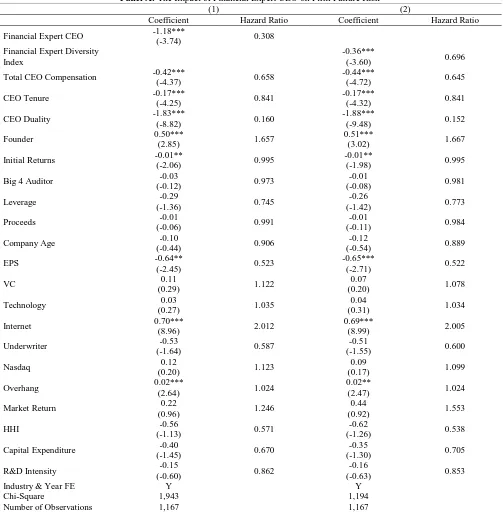

In Specification (2) we replace financial expert with financial expert diversity index which is the first factor of applying principal components analysis to four proxies of the diversity of financial

experience.5 The hazard ratio of 0.696 of the variable financial expert diversity index shows that for

each unit increase in the index, the firm’s failure risk decreases by 69.6%. Specifications (1) to (4) in Panel B of Table 3 estimate the regressions on the four measures of managerial skills employed to generate the index, specifically, number of firms, number of roles, CEO past financial experience, and time duration on financial positions. The sign and significance of the components of financial diversity index remain negative and significant. The variable number of firms has the risk ratio of 0.364. This implies that for each additional number of firms in which the CEO worked in a financial role, the failure risk decreases by 36.4%.

As for the findings about the other control variables, their sign and significance is generally consistent with prior studies in all specifications. In line with Gounopoulos et al. (2018), we find that IPO firms with high remunerated managers tend to have lower failure risk. Also, our findings suggest that firms led by CEOs who are also the chairman and have been serving for many years with (high tenure) are more likely to survive, which is consistent with Adams et al. (2005). However, IPO firms managed by founder CEOs have higher probabilities of failure. Moreover, we find that firms with high insider ownership (overhang) and internet firms to have higher failure risks in subsequent periods and survive for a shorter time, while more profitable firms have a lower probability of failure and a longer time to survive. With respect to the accounting and financial intermediaries, our results indicate that these variables do not have a significant impact on firm failure risk, which is inconsistent with the prior literature (Bhattacharya et al., 2015; Espenlaub et al., 2016).

4. Robustness Analysis

In this section, we investigate the robustness of our results in various ways. We begin by using alternative methods, employing alternative definitions of the dependent variable (i.e., survivors or non survivors) and then alternative industry definitions.

4.1 Accelerated Failure Time (AFT) Method

The results so far indicate that financial expert CEOs enhance IPO survivability. For robustness check, we further examine this hypothesis, by estimating an Accelerate Failure Time (AFT) model of IPO time-to-failure. In contrast with Cox model, this approach uses as dependent

5

12

variable the survival time which is the natural logarithm of the time to delist which is measured in months. Thus, a positive (negative) coefficient in the financial expert CEO implies a longer (shorter) period to survive.

In Table 4 we present both the coefficient estimates and the time ratios along with their associated p-values. The results in Table 4 show that the coefficients on financial expert CEO and financial expert diversity are positive and significant at the 1% and 5% level, respectively. In particular, the coefficient on financial expert CEO is 0.25, which suggests that, on average, the survival time of firms with financial expert CEO increases by 28.4%. This translates to an increase in the survival time from 90.57 months (7.55 years) to 116.29 months (9.69 years).

4.2 Alternative Definitions of Failure Risk and Industries

In the analysis so far, we classified M&A delistings as survivors, and as a result, classify as failures only the firms that were liquidated or dropped. In this section, we classify M&As as either “censored survivors” or as genuine delistings. Fama and French (2004) suggest that managers who have personal benefits may be reluctant to lose control unless forced to do so because of financial difficulties, arguments suggesting that low-quality IPO firms are more likely to be acquired. On the other hand, Zingales (1995) finds that the IPO may be the first step in a gradual sale of the company. Therefore, not all M&A-related survivors are necessarily negative news to investors of target companies. Due to this vagueness, we investigate the robustness of our findings by considering some M&A as “censored survivors”, and some as failures.

To identify the censored survivors, we acknowledge that, due to poor performance or financial difficulties, some M&A delistings are typically less attractive to target shareholders than other M&As. We follow Espenlaub et al. (2012, 2016) and distinguish such cases by using a performance criterion. More specifically, we locate M&A delisting of well-performing companies either the year prior to the acquisition or in the year prior to the IPO by ranking firms on the basis of four performance measures: cash to total assets, total liabilities to total assets, operating income to total assets, current assets to current liabilities. Firms that rank below (above) the median based on all four indicators are considered as failures (censored survivors).

re-13

examine the association between financial expert CEO and IPO survival by investigating whether each company continues to be listed three instead of five years after the issue date.

The results of our robustness checks are shown in specifications (1), (2) and (3) of Panel A of Table 5, and are qualitatively similar to the baseline results. In particular, the coefficients on financial expert CEO continue to be negative but with weaker economic and statistical significance. For example, the hazard ratio of the second alternative definition (0.766) shows that the failure risk of IPO firms with a financial expert CEO is 76.6% of the failure risk of firms without a financial expert CEO.

Finally, we rerun our baseline regressions, but instead of using the Fama-French 17 industry classification scheme to control for time-invariant unobservable industry characteristics we employ the Fama-French 30 and Fama-French 49 specifications. In addition to that, we examine the robustness of our results by also excluding the industry fixed effects. The results in Panel B of Table 5 reveal that our results in terms of sign and significance are consistent with our prior findings, which means that our results are not affected by industry membership.

5. Identification and Alternative Interpretations

Our results so far establish a robust negative (positive) relationship with IPO failure (survival). It is possible, however, that endogeneity concerns plague our empirical analysis. In particular, our tests are vulnerable to two key identification issues. These are: i) observable or unobservable omitted variable bias (hidden bias, see, e.g., Armstrong et a., 2010) i.e., some other/unknown CEO or firm factors affecting both the failure rates and the financial expert index in a similar manner that remain excluded in the regressions and ii) the possibility of non-random assignment of a FE CEO to a firm, i.e., selection effects.

As such, there are different alternative explanations of our findings: we group them into three broad categories: Omitted Firm Characteristics (firm heterogeneity), Omitted CEO Characteristics (CEO heterogeneity), and endogenous firm-CEO matching. In the following sections, we provide some pieces of evidence inconsistent with a pure endogeneity explanation of our results, suggesting that at least part of the financial expertise-survival relationship is causal.

5.1 Omitted Firm Characteristics

14

results is that firm-level characteristics that can be associated with FE of the CEO are driving our results. This suggests that better controls for firm quality should dissipate the FE effect.

As before, the inclusion of firm fixed effects would control for all observed and unobserved time-invariant firm characteristics that may be correlated with IPO success. Since we observe every firm only once, we cannot implement this approach. Instead, the closest substitute, in our context, is the inclusion of firm characteristics that capture firm quality or corporate governance that can be assumed to remain reasonably stable during the IPO process.

We focus on two main issues: corporate governance and firm quality. Prior empirical evidence suggests that experienced, prestigious and independent directors are expected to have more stringent monitoring process of CEOs (Fama and Jensen, 1983; Gilson, 1990; Filatotchev and Allcock, 2013). From this perspective, we examine if and how the quality of corporate governance can affect our results by constructing a corporate governance measure. In addition, to our governance quality measure, we can also measure the quality of the corporate governance by examining whether or not the CEO is powerful. Finally, we use a dummy that indicates the diversification of the firm.

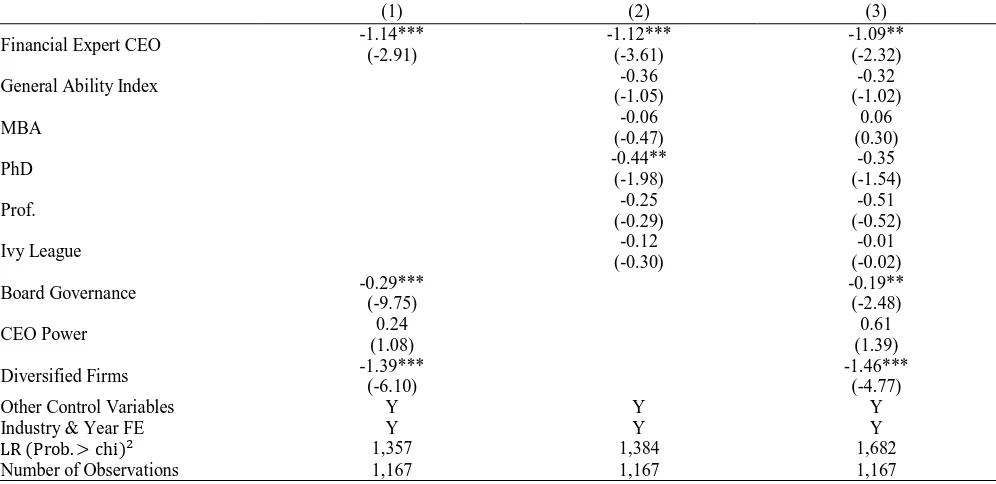

In Column (1) of Table 6 we control for some additional firm characteristics. Our results show that, diversified firms with strong corporate governance have longer survival rates, while the sign and significance of financial expert CEO remain robust.

5.2 Omitted CEO Characteristics

We examine the possibility that omitted CEO-level characteristics are driving the FE effect on IPO survival. CEO may have observed and unobserved, time-invariant characteristics that are correlated with FE and the long-term viability of IPO issuers. For example, some CEOs have traits that are correlated with undertaking a high ranking finance-related role – such as conservatism, ethical principles, or exceptional leadership ability that allows one to build a unique financial skill set and rise quickly through the ranks – which may also make them more inclined to be engaged in firms with particular characteristics. It might be the case, for instance, that CEOs with financial experience work in companies with better access to capital markets or business models that focus on less innovative products than their counterparts. Hence, this measure might simply capture the effect of other skills.

15

managerial skills or experiences correlated with FE. These explanations suggest that inclusion of CEO fixed should make the FE effect disappear.

To evaluate whether the above hypotheses induce a spurious or biased effect on the link between FE and IPO survival, we would ideally like to compare IPO different delisting cases for the same CEO, once with and once without FE. This approach typical involves the inclusion of CEO-firm fixed effects and controls for fixed unobserved and observed CEO heterogeneity, thereby mitigating concerns that some alternative explanations are driving the results. However, in our context we are not able to observe within-CEO-firm variation, as every issuer can conduct an IPO only once. Instead, we can assume that, at the time of the IPO, some observable CEO characteristics might be considered as time-invariant, and hence absorb to some extent the influence of total unobserved fixed heterogeneity, i.e., omitted CEO attributes that might be correlated with FE.

Initially, we seek to capture the skills of the managers by differentiating them into specialists and generalists (Custodio et al., 2013). Another concern is that the completion of an IPO where the CEO has prior financial experience is related with his or her talent. Following prior literature (e.g., Custodio et al., 2013; Falato and Milbourn, 2015; Custodio and Mentzger, 2013; Gounopoulos and Pham, 2018), we utilize educational attainments to construct four different proxies for CEO talent: MBA, PhD, Prof. and Ivy League. These variables take a value of one if the CEO holds an MBA, a PhD degree, a professional degree (e.g., CPA, ACCA, CFA and ICEAW) or an academic degree from an Ivy League School, respectively.

In Column (2) of Table 6 we control for the CEO’s general managerial skills along with CEO educational attainments. We find that the inclusion of these controls does not meaningfully affect the FE effect. Specifically, the controls for experience and talent do not have any statistical significance. An exception is the PhD, which appears to be negatively related to IPO failure. Therefore, their

omission does not pose a problem for the validity of the FE.6 In Column (3) we simultaneously

control for CEO and firm characteristics and find that after controlling for these factors the FE effect does the attenuate. Overall, this battery of tests alleviates the concern that other CEO and/or firm characteristics that are merely associated with CEOs’ financial expertise are driving our results.

5.3 Omitted CEO Ability, Self-Selection and Compensation

Our results are consistent with two non-mutually exclusive views. Under the “financial skills view” FE is useful to the implementation of a given financial policy (e.g., going public), and firms optimally appoint financial experts when financial policies are more important than other policies.

6

16

However, the results are also consistent with the view under which the skills of CEO do not matter (i.e., the “no financial skills view”). This could be the case when FE CEOs have an idiosyncratic preference for specific corporate policies or specific type of firms, and firms hire CEOs with the preferences to match their needs (i.e., their life cycle stage or their business model). The observed assortative matching is based in the conjecture that FE CEOs have a preference for less risky business models and would prefer to match themselves to these firms accordingly. In this case, hiring a FE CEO might be the cheapest way to implement such their predetermined strategy.

The existence of an assortative matching mechanism between FE CEOs and firms could be also justified by other reasons not directly associated with financial expertise. For instance, FE CEOs might have a useful yet unobservable skill-set that tends to be correlated with financial sophistication. If observing FE is a side-effect of some superior ability or primary skill which is (unobservable to researchers and) unrelated to preferences but known to the board of directors, we should expect that FE CEOs can earn higher compensation.

To distinguish convincingly between the financial and no financial skill views, it would be ideal to break the optimal and endogenous matching by allocating CEOs with different set of skills in a random fashion to firms with different business models. However, this test is not feasible because we observe each CEO-form pair only once. Instead, we rely on an indirect methodology and test above conjectures by a running a compensation regression with a set of firm-level and CEO-level controls, as commonly used in the CEO compensation literature (see, for instance, Custodio et al., 2013).

17 5.4 Propensity Score Matching

Panel B of Table 2 shows that there substantial differences in some characteristics among firms that have FE and firms that do not. FE CEOs are more likely to have Ivy League degrees, more foreign experience, chairmanship, but less likely time in the office. Also firms with FE have more prestigious underwriters, auditors, less venture capital backing, and are characterized by less innovative business models. These differences raise the possibility that the effect of FE on IPO survival might be a statistical artefact stemming model misspecification or explained by observable differences, given that certain observable firm and CEO attributes might simultaneously affect FE and IPO failure rates.

To mitigate any potential endogenous selection (i.e., non-randomized) biases relating to

observable characteristics and to minimize the impact of observable confounding variables on the dependent variable, we employ a one-to-one matching estimation (Rosenbaum and Rubin, 1983; Hirano et al., 2003; Armstrong et al., 2010; Roberts and Whited, 2012). This technique involves the creation of pairs of firms that have a similar probability of having a financial expert CEO given their characteristics but that actually have different types of CEOs (e.g., a nonfinancial expert CEO for each FE CEO). As such, it ensures that that there is little difference in observable characteristics between the treatment (with a FE CEO) and the control (with a nonFE CEO) group of firms, so that the variation in the dependent variable (IPO survival) can be attributed to the variation in the test variable (FE) with greater confidence.

In implementing this method, we run a conditional probit regression to estimate propensity scores based on the probability or receiving the treatment (i.e., FE CEOs) conditional on a set of carefully selected control variables. For each treatment firm featuring a financial expert CEO, we select a matching control firm featuring a non-financial expert CEO from the same year, with the requirement that the absolute difference of the propensity score among pairs does not exceed 0.01. We employ this method without repetition, that is, if there is a concentration of firms with nonFE CEOs that meet this criterion, we keep only those with the smallest difference in the propensity scores. In estimating the propensity score for each firm, we consider a set of controls that essentially capture all the CEO and firm determinants used in the baseline regression. We also include, the Fama-French industry membership, since some industries (e.g., Oil and Gas or Computer Equipment and Services) are more likely to feature a FE CEO compared to other industries (e.g., Products Manufacturing).

difference-in-18

difference means become statistically insignificant for the matched sample, consistent with the view that the propensity score matching approach succeeds in making the sample of firms with FE managers comparable to the sample of firms with no FE managers.

Based on these matched sets of treatment and controls firms, we initially calculate the paired difference of the proportion of failed firms, and then we run multivariate tests with a full set of control variables and fixed effects. The results in Panel B and of Table 8, reinforces the baseline results. Specifically, Panel B and C re-run regression models of Table 3 using the Cox and PSM on the matched sample and confirm the significantly negative relation between FE and the incidence of failure. Overall, the PSM results continue to demonstrate that FE has a strong positive relationship with IPO survival, reinforcing the baseline inferences that that there is a systematic effect of FE on IPO survival rates.

5.5 Two-stage Heckman (1979) Procedure

While our tests mitigate endogeneity issues arising from differences in the distribution of observable covariates, it is still possible that unobserved correlated omitted variable or selection bias problem remains. For example, it is likely that more able managers prefer or are more likely to be selected by the board of prestigious firms. We attempt to alleviate these concerns using the two-stage Heckman (1979) test.

Following Srinidhi et al., (2011), the self-selection parameter (i.e., the Inverse Mills Ratio - IMR) is computed in the first-stage regression using a probit model that predicts the likelihood a firm has a financial expert CEO. To estimate the probit model, we regress the financial expert dummy on potential determinants of financial expertise to estimate IMR. The set of explanatory variables includes the standard set firm- and CEO-level controls used in Table 3 of the paper. In the second-stage regression, IMR is used as an additional control variable in our results.

19

However, the negative relation between financial experts and factors that indicate elevated inherent riskiness such as VCs, technology and internet companies as well firms listed on Nasdaq provide evidence of selection effect similar to that of the life cycle.

The second stage results in Column 2 of Table 9 show that, while there is evidence of selection, the coefficient on financial expertise remains significant (at the 1% level) and of similar magnitude as in our baseline regression in Column 1 of Table 3 of the paper. The results in Column 2 for the second stage regression after controlling for IMR, show a negative association between FE and IPO failure that is significant at the 1% level.

5.6 Endogenous CEO-firm matching and CEO Tenure

The two-stage Heckman analysis revealed the presence of selection bias in our results. This finding suggests that CEOs and companies are not matched randomly. Rather a CEO is chosen is by the board of directors. Financial experience might be a criterion for the appointment of a particular CEO. For instance, Custodio and Metzger (2014) find that financial expert CEOs tend to be hired in mature, seasoned firms rather than firms characterized by risky growth prospect. Using a similar reasoning in our context, the most obvious explanation for CEO-firm matching is that firm with relatively low riskiness or low propensity to innovate (low-tech, non-internet firms, or firms that are not listed on Nasdaq) prefer CEOs which have easy access to finance but not necessarily the skill set to undertake innovative risky projects.

While endogenous matching is entirely compatible with FE having a causal effect on firm survival, we would like to gain further insight about whether our findings are driven by causal effect of FE CEOs on survival or solely by matching. To do so, we restrict our sample to a subset for which matching is likely to be less important. As Hirshleifer et al. (2012) point out, because a firm’s growth opportunities vary over as its competitive position shifts, the matching effect between CEO FE and time-varying firm characteristics are likely to be strongest when the CEO is first appointed. Therefore, under the selection hypothesis, one would expect that financial sophistication would be more valuable for recently hired CEOS. If selection is driving the results, we would expect higher survival rates to be driven mainly by recently appointed CEOs.

20

statistically different from each other. These findings suggest that the relation between IPO survival and FE is not primarily driven by firms’ endogenous selection of managers with FE skills.

6. How Does Financial Expertise Affect IPO Performance?

We argue that financial expert CEOs will affect various aspects of the IPO and post-IPO performance through two broad channels: the reputation channel and the ability channel. Because the IPO performance can be affected by both channels in various ways, we initially outline why a certification and an ability effect exists. Then, we discuss how the interaction of these mechanisms may aid equity issuers in raising capital in the IPO market and managing the firm successfully in the aftermarket.

The reputation effect may arise as follows. Chemmanur and Paeglis (2005) assert that top managers build up reputational capital over their career through repeated dealings with financial intermediaries as part of their job. For instance, they may need to raise bank financing or capital through a private placement or a debt issue. In light of this, one would expect the importance of CEOs with extensive financial training to be elevated in the IPO context. In addition, these managers are well aware that their future job prospects as well as their remuneration trajectory are directly affected by their reputational capital in conducting successful fundraising events. Consequently, the greater the reputation a manager has at stake, the greater is the future loss from deceiving financial market players, and as such, financial expertise might play a certification role in the valuation of an IPO (Chemmanur et al., 2009). Accordingly, this reasoning implies that when conducting IPOs financial experts CEOs are more likely to price the firm’s equity more fairly than nonfinancial expert CEOs, as otherwise the IPO market might tarnish their personal reputational capital, thereby severely damaging their value in the labour market as well.

21

capital of the manager, thereby making it easier and cheaper for a private firm to go public (affecting various aspect of IPO pricing).

Second, if one thinks of CEOs as skilled professionals whose jobs involves gathering and analysing financial data, it seems reasonable that financial expert CEOs may perform better than their counterparts after the initial offering. One could give a number of reasons why financial expertise might be related to operating performance. For example, financial expert CEOs are less likely to fall into WACC fallacy trap, and hence less probable to under- or over-estimate the cost of capital of future projects (Custodio et al. 2013). As such, financial sophistication enables managers to select better projects as well as to implement them more ably (Chemmanur and Paeglis, 2005). Thus, it could be the case that financial expert CEOs are associated with stronger operating performance after the IPO.

6.1 The Role of Financial Expertise throughout the IPO Price Discovery Process

The preceding discussion suggests that, either due to reputational concerns or because of greater ability, financial experts are able to convey the intrinsic value of their firms more credibly to outsiders. Being more effective in certifying the quality of the issue reduces information asymmetries between insiders and outsiders, thereby facilitating the access to equity (IPO) market. However, what is less clear is the precise mechanism through which financial sophistication might lead to a successful offering. To better understand how this might happen, we consider the role of financial expertise through the entire IPO pricing process.

6.1.1 The Matching of Firms and Underwriters

22 6.1.2 Predictability of Price Revisions

After the issuing, firm chooses the investment banker(s), the pricing of an IPO can be thought of as occurring in three interrelated stages: the premarket due diligence where the issuer and the underwriter agree on a range of prices and draft an initial prospectus that is filed with the SEC; the bookbuilding where private information is gathered by informed investors during road shows; and the establishment of the market price during the first trading day in the stock market (Lowry and Schwert, 2004). However, to better understand the steps of the IPO pricing process and their valuation implication, we initially have to consider why the initial offer price might not be equal to the final offer.

Hanley and Hoberg (2010) contend that price changes during the IPO process might arise either because issuers intentionally set the initial offer below the fair value given the information known at the time of initial filing and/or due to new information revealed during bookbuilding. One plausible reason for the former is provided by Lowry and Schwert (2004), as they contend that the market perceives a final offer price less than the initial filing price to be a very negative signal about the future prospects of an IPO. Consistent with this intuition, they show that investment bankers that are more reputable are more conservative in setting the initial price range. Given that the value of financial expertise in the capital and labour market is also be based on reputational concerns, it seems reasonable that financial expert CEOs would also strive to avoid ending up with the value of the firm being worth less than they had initially forecasted. Under this scenario, issuers will deliberately lowball the initial price. In this case, one would expect financial expert CEO to be positively related with price updates/changes during bookbuilding.

6.1.3 Predictability of Absolute Price Revision and Underpricing

Irrespective of whether the initial offer price is biased downward in the presence of reputable managers, as mentioned above, price changes might also occur due to information revelation during bookbuilding. However, Hanley and Hoberg (2010) argue that, in that case several complications may arise, since there exists a trade-off between pricing an issue using information acquired from premarket due diligence and information gathered from investors during bookbuilding.

By engaging in price discovery prior to the filing of the initial prospectus with the SEC, the

issuing firm, the underwriter (and their legal counsel) choose to expend substantial resources on due

23

substance of the initial price will be reflected in lower absolute price changes. Importantly, it will also reduce the need for information generated during bookbuilding (Benveniste and Spindt, 1989), thereby lowering compensation to informed investors in the form of higher initial returns via the well-known partial adjustment process (Hanley 1993). However, these benefits are offset by the potential cost of revealing strategic or proprietary information to rivals (Bhattacharya and Ritter, 1983; Darrough and Stoughton, 1990; Bhattacharya and Chiesa, 1995; Boone et al., 2016).

If, on the other hand, the cost of gathering information in the premarket is prohibitively expensive relative to the benefit of more accurate initial pricing and lower underpricing, the issuing firm and its investment bankers may choose, instead, to engage in price discovery during bookbuilding. While this reduces the cost of premarket information production, the issuer and the underwriter rely to a greater extent on information produced by informed investors to price the issue. In this case, the opportunity cost of the issue increases as investors must be rewarded through both

increased allocation and initial returns for truthfully revealing their assessment of the issue.

In our context, we believe that the decision on which method is preferable by financial experts depends on two factors: the credibility accompanying the estimates of the proposed offer price and the potential risk of revealing proprietary information to product market competitors. Regarding the first factor, we expect that initial price estimates provided by firms run by financial expert CEO to be highly perceived by outside investors, because, as discussed earlier, managers with high financial sophistication are not only able to better communicate financial information but they are also reputational liable for the provision of any false or misleading value estimates.

As for the second factor, it should be noted that Custodio and Metzger (2014) demonstrate that financial experts are generally worse innovators than their counterparts. If this is so, it is reasonable to expect that firms run by financial expert CEOs are exposed to less risk arising from the disclosure of proprietary information. As a consequence, we anticipate that the premarket information production process in more attractive than the bookbuilding process for firms run by financial experts, especially after considering that the former choice recedes the reliance on the bookbuilding valuation process, thereby resulting in a lower amount of information generated from informed investors. In this case, CEOs with financial sophistication are more likely to not only generate more accurate initial offer prices but also to incur lower costs in terms underpricing returns as a compensation to informed

investors for providing private information.7 Taken together, we hypothesize that financial expert

CEOs are associated with lower absolute price revision and lower underpricing.

7

24

6.1.4 Results on the Influence of Financial Expert CEOs on the IPO Pricing Process

Table 11 provides the results about the matching between underwriters and financial experts as well as the link between financial expertise and the IPO price discovery process. Consistent with the notion that career background of a firm’s manager is being used by underwriters as an indicator of firm quality, Column 1 reports that the coefficient for financial expert is positive and significant. This finding is important, given that prestigious underwriters provide all-star coverage, more reputable syndicates, and higher valuations (Fernando et al., 2012). In addition, it indicates that, apart from firm’s financial information (Fernando et al., 2005), the IPO firm’s top management team also plays an important role in attracting reputable underwriters.

In Column (2), we find that financial expert CEOs are associated with higher proposed changes in offer prices, which is consistent with the idea that reputable managers are more conservative in pricing an issue. Nevertheless, as expected financial experts reduce information asymmetry during bookbuilding and this is evident in lower absolute revision and lower underpricing, as shown, in Columns (3) and (4), respectively.

6.2 The Link between Secondary Market Information Asymmetry and Financial Expertise The IPO process involves significant uncertainty about the money to be raised, and most importantly, about the fair price for the equity (Beatty and Ritter, 1986; Rock, 1986). However, several studies acknowledge the possibility that the associated uncertainty is not fully resolved at first trading day (Lowry et al. 2010). Hence, it is plausible that the resolution of uncertainty surrounding the IPO information environment extends beyond the IPO date. In this regard, given that financial expert CEOs mitigate pre-IPO information asymmetry, we anticipate that they will also be related to lower information asymmetry in the days and weeks immediately following the IPO. To examine this possibility we consider the equity return volatility the immediate aftermarket.

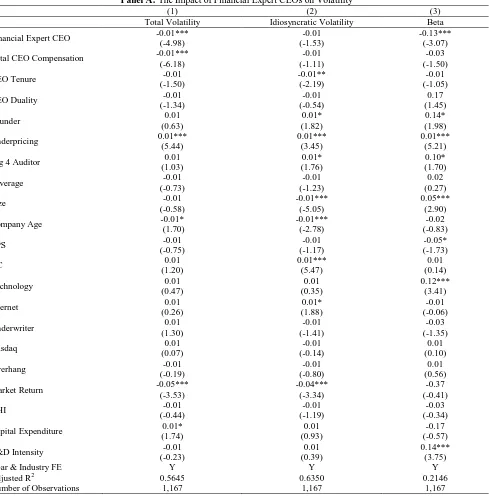

Following, Barth, Landsman and Taylor (2017), we use three measures of post-IPO volatility: total volatility, idiosyncratic volatility, and beta. If firms run financial expert CEOs have less inherent information uncertainty in the equity market, they will be exposed to lower information risk in terms of total equity volatility. However, as mentioned before, financial expert CEOs tend to invest less in the generation of new knowledge and products than their counterparts. In this case, the ratio of private information to public information would be greater for firms with nonfinancial specialists CEOs.

25

Therefore, any reduction in total risk associated with financial experts would be less contingent on firm-specific price variation. In other words, variation in total risk associated with financial sophisticated managers should be driven by the systematic component of equity risk rather than the idiosyncratic component.

6.2.1 Results on the Influence of Financial Expert CEOs on the Immediate IPO Aftermarket The results on the influence of financial specialists CEOs are reported in Panel A of Table 12. In Column (1) we find a strong negative relationship between financial expertise and total stock return volatility, consistent with the notion of lower information asymmetry. In Columns (2) and (3) we decompose total volatility into its idiosyncratic and systematic components, respectively. We find that the negative link between total stock return variability and financial expertise is driven by the systematic rather than the systematic component.

6.3 Financial Expertise and Post-IPO Stock Market Performance

If financial expertise is indeed an important aspect of CEO’s human capital then it may explain to some extent the potential of future projects to generate cash flows, and therefore serve as a determinant of a firm’s stock market value and future operating performance (Gompers et al., 2004). As Chemmanur and Paeglis (2005) point out, better quality managers have better foresight into the potential value of future investment opportunities. In turn, this enables them to select better projects (in term of NPV) and implement more effectively and efficiently. In analogous manner, we expect that, if financial experts CEOs possess to some extent these abilities, then they will be characterized with greater subsequent operating cash flows. In addition, since the market value of the firm is essentially the present values of the firm’s expected future cash flows, in a symmetric information setting financial expert CEOs will be related to higher market values.

26

not fully rational, we hypothesize that CEO financial expertise will be positively related to the firm’s long-run stock performance.

6.3.1 Results on the Influence of Financial Expert CEOs on Post-IPO Market Performance The results on the influence of financial specialists CEOs are reported in B and C of Table 12. In Panel B, we find a strong positive relationship between financial expertise and stock return performance 12 months after the offering. In Columns (2) and (3) we extend the holding period up to 3 years and find that the positive relationship not only persists but becomes stronger. Interestingly, we reach similar a conclusion if we look at the relationship between FE and the average Tobin’s Q in the three years following the IPO.

6.4 Financial Expertise Accounting and CEO Turnover

To better understand why FE affects the perceptions of investor in the aftermarket, we examine several avenues. First, we test whether CEOs with low financial skills are more likely to experience turnover after the IPO. If financial expertise captures some aspect of managerial ability that is useful to IPO issuers, then it could predict future job loss. As shown in Panel D of Table 12, (Column (1)), there is evidence of a negative but insignificant relation between FE and CEO turnover in the three years after IPO. However, Column (2) expand the post-IPO period to all available years (which is five), and in this slightly longer time period, we find a significant negative relation between FE and future CEO turnover. FE’s ability to predict which CEOs retain their jobs suggests that it capture meaningful aspects of manager quality and provides one reason for the market’s incorporation of FE into price.

As a second test, we explore why nonFE CEOs might need to be replaced in the future: poor subsequent performance. As a proxy for (poor) performance, we examine subsequent accounting profitability (i.e., three-year post-IPO cumulative return on Assets). As shown in Column (2) of Panel C (Table 12), we find significant evidence of a positive relation between FE and future ROA. Collectively, these results provide a reason for incorporation of FE into long-run price or the subsequent turnover of (poorly perceived) CEOs.

6.5 Financial Expert CEOs and Financial Policies

27

view/interpretation that FE CEOs implement aggressive financial policies due to the easier access to the credit markets.

While these findings are consistent with literature suggesting that the managerial impact of financial policies is big (Graham and Harvey, 2001; Lins et al., 2010), it remains an empirical question whether FE CEOs impose their idiosyncratic styles on IPO companies. Unlike seasoned firms which have largely stable financial policies, new public firms are in the early stage of defining their financial policies. An additional layer of complexity is added by the fact that FE CEOs should also have easier access to the equity markets as indicated by our evidence on IPOs and the study of Chemmanur, Paeglis and Simonyan (2009) on Seasoned Equity Offerings (SEOs). Having this in mind, we would anticipate that FE CEOs running IPO firms to relate with negative cash reserves, while the ex-ante influence of FE on financial leverage in this context is ambiguous.

Table 13 confirms the cash holdings hypothesis as it reveals that in the years following the IPO CEOs accumulate on average less cash if they possess financial skills. On the other hand, the coefficient of FE on leverage is positive but indistinguishable from zero. In any case, the results from this section support the idea of imprinting effect of FE CEOs on financial policies

6.6 Financial Expert CEOs and Investment Policies

As a final empirical test, we evaluate how financial expert CEOs interact with investment decisions. We examine three investment policies, research and development (R&D), capital expenditures (CAPEX), and the decision to acquire assets inorganically via acquisitions. In Table 13 we find that firms run by financial experts do not seem to overinvest as indicated by the negative coefficients of research and development and capital expenditures, respectively. This finding is also consistent with the conclusion of Custodio and Metzger (2014) that financial experts are worse innovators. Interestingly, however, financial expert CEOs are associated with higher acquisition expenditures. Although an explanation of this finding is outside the scope of our paper, we conjecture that financial expert CEOs resort to this type of investment because their firms might have exhausted to stock of organic investment opportunities.

7. Conclusion

28

specifically, we analyze the effects of CEOs with a career background on finance on newly listed firms.

Employing survival analysis, our study suggests that IPO firms with financial expert CEOs have a lower probability of failure and a longer time to survive. Notably, further tests on the components of financial diversity index reveal that our baseline results are mainly driven by the number of firms and roles that the CEO has worked in financial roles. Our results are robust to estimating our regressions using alternative measures and after controlling for the potential endogenous CEO-firm matching by conducting numerous tests (e.g., PSM, Heckman). Further, we attempt to identify the underlying causes of this association and we document that CEOs with a career background in finance get better access to the IPO market, as evidenced by lower absolute revisions during bookbuilding and lower IPO first-day returns. In addition, our results indicate that firms to which the CEO has financial expertise tend to have lower volatility in the immediate after market and exhibit higher operating performance

29 References

Adams, R.; B. Almeida; and D. Ferreira. “Powerful CEOs and Their Impact on Corporate

Performance.” The Review of Financial Studies, 18 (2005), 1403-1432.

Alhadab, M., Clacher, I., and Keasey, K. 2014. Real and Accrual Earnings Management and IPO Failure Risk. Accounting and Business Research 45(1), 55-92.

Armstrong, S. C., Guay, W. R, and Weber, J. P. 2010. The Role of Information and Financial Reporting in Corporate Governance and Debt Contracting. Journal of Accounting and Economics 50 (2-3), 179-234.

Armstrong, S. C., Jagolinzer, A. D., and Larcker, D. F. 2010. Chief Executive Officer Equity Incentives and Accounting Irregularities. Journal of Accounting Research 48 (2), 225- 271

Badolato, P. E., Donelson, D. C., and Ege, M. 2014. Audit Committee Financial Expertise and Earnings Management: The Role of Status. Journal of Accounting and Economics 58, 208-230.

Barth, M., E., Landsman, W., R., and Taylor, D. J. 2017. The JOBS Act and Information Uncertainty in IPO Firms. The Accounting Review 92(6), 625-647.

Baron, D. P. 1982. A Model of the Demand for Investment Banking Advising and Distribution Services for New Issues. The Journal of Finance 37(4), 955-976.

Beatty, R., and Ritter, J. 1986. Investment Banking, Reputation, and the Underpricing of Initial Public Offerings. Journal of Financial Economics 15(1-2), 213-232.

Benmelech, E., and Frydman, C. 2015. Military CEOs. Journal of Financial Economics 117(1), 43-59. Bernile, G., Bhagwat, V., and Rau, P. R. 2016. What Doesn’t Kill You Only Make You More Risk-Loving: Early-Life Disasters and CEO Behavior 72(1), 167-206.

Bertrand, M. 2009. CEOs. Annual Review of Economics 1, 121-150.

Bertrand, M., and Schoar, A. 2003. Managing with Style: The Effect of Managers on Firm Policies. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 118(4), 1169-1208.

Bhattacharya, U.; A. Borisov; and X. Yu. 2015. Firm Mortality and Natal Financial Care. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 50, 61-88.

Bhattacharya, S., and Ritter, J. 1983. Innovation and Communication: Signaling with Partial Disclosure. Review of Economic Studies 50(2), 331-346.

Bhattacharya, S., and Chiesa, G. 1995. Proprietary Information, Financial Intermediation, and Research Incentives. Journal of Financial Intermediation 4(4), 328-357.