Rochester Institute of Technology

RIT Scholar Works

Theses

Thesis/Dissertation Collections

5-17-1985

The Image and Its Pot

Gary Baxter

Follow this and additional works at:

http://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses

This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Thesis/Dissertation Collections at RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion

in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact

ritscholarworks@rit.edu.

Recommended Citation

ROCHESTER

INSTITUTE

OF

TECHNOLOGY

A

Thesis

Submitted

to

the

Faculty

ofThe

College

ofFine

andApplied

Arts

in

Candidacy

for

the

Degree

ofMASTER

OF

FINE

ARTS

THE

IMAGE

AND

ITS

POT

By

Gary

D.

Baxter

APPROVALS

Advisor:

Graham Marks

Date:

5/17/85

Ass

0

cia t e Ad vis

0

r:

---!:::B:..::o:..!:b::....::::S..::c~h~m~it=z

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

_

Date

:

~5~/~1~7/~8~5

________________ ___

Ass

0

cia t e Ad vis

0

r:

--=!..J!::::o.!.-'n!....!D=o:..::d~d:!....-

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

_

Date:

~5~/~1~7/~8~5~

________________ _

Assistant to the Dean

for G r ad u ate A f f air s:

-!...F.!..:re::.:d~M~eJ-y..::e.!...r

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

_

Dean, College of

Fine

&

Applied Arts:

Date:

~8~/~1~1/~8~5

________________ ___

Dr. Robert H. Johnston Ph. D.

Date:

~8~/~13~/~8~5

________________ ___

I, Gary D. Baxter, hereby grant permission to the

Wallace Memorial Library of RIT, to reproduce

my thesis in whole or in part.

Any reproduction

will not be for commercial use or profit.

Gary D. Baxter

TABLE

OF

CONTENTS

LIST

OF

ILLUSTRATIONS

iv

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

vINTRODUCTION

1

THREE

SHORT

STORIES

3

ON

IMAGE

AND

FORM

8

CONCLUSION

15

ENDNOTES

18

ILLUSTRATIONS

19

APPENDIXES

3 1

BIBLIOGRAPHY

33

LIST

OF

ILLUSTRATIONS

1.

Zuni

Water

Jar,

c.1880

19

2.

Zuni

Ceremonial

Jar,

c.1890

20

3.

Korean

Ewer,

Koryo

Dynasty,

c.1200

21

4.

Iranian

Bowl,

c.1300

22

5.

Dark

Forest

,1958

(by

Milton

Avery)

23

6

.Rabbit

Platter

24

7

.Frog

Platter

2 5

8

.Frog

Platter

2 6

9

.Frog

Vase

2 7

I

0

.Black

andOrange

Frog

Vase

2

8

II.

Detail

ofblack

and orange vase29

I

2

.Dead

Frog

Container

3 0

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I

wouldlike

to expressmy

thanks

toGraham

Marks,

Bob

Schmitz

andJohn

Dodd

for

serving

onmy

thesis

committee andsharing

theirinsights

with me .

The

input

and motivation providedby

the

people

I

sharedthe

ceramics studio with wasalso

very

helpful.

For

keeping

myself andmy

family

relativelyout of

debt,

I

wouldlike

to thankHoughton

College

for

making

this

financially

possible.Most

ofall,

I

thankmy

wife,

Wendy

for

taking

uponherself

the

responsibilitiesI

had

to

neglectin

order to makethe

most ofthis

INTRODUCTION

Prior

to

graduate schoolmy

experience withclay

wasmainly

the

production of utilitarianpottery.

The

shape of eachpot,

the

relationship

of

its

parts andits

surface wasdetermined

by

each pot'sintended

use.This

meanttaking

into

account suchthings

asthe

vulnerability

of a

spout,

the

ease with which a spoon orfork

could remove

food

from

aninside

corner,

orthe

relationship

of ahandle

to

ahand.

To

have

first

made a pot and

then

figured

outhow

to

useit,

would

have

seemedludicrous.

To

have

realized anew

activity

in

the

routine oflife

andthen

develop

a pot

for

that

reason,

seemed tofill

the

pot withmeaning

and personal expression.The

thesis

project provided anopportunity

to

focus

upon waysin

whichform,

imagery,

texture

and color could

be

used toheighten

the

meaning

and personal expression of a pot.

Pictorial

imagery

was

especially

appealing.In

additionto

being

new and

refreshing,

pictorialimagery

was away

to

bring

togethermy

interests

in

narrative subjectmatter,

drawing

and pottery.The

problem wasthat

a particular

image

interfered

withmy

approachto

functional

pottery.Carved

lines,

distorted

surfaces and expressive

textures

gotin

theway

of

the

domestic

activities such ascooking,

serving,

eating

anddrinking

that

I

generally associatedwith utilitarian pottery.

And

yetit

wasimportant

to

retainthe

vesselformat

because

ofits

accessibility

-its

long

standing placein

the

home.

As

my

thinking

along theselines

evolved,

I

became

less

concerned withthe

connectionsbetween

pottery

andfood

anddecided

to explorethe

useof pottery

forms

to

express otherinterests

andexperiences .

Those

experiences whichhave

comefrom

time

spent

in

natural settingshave

been

theprimary

source of

inspiration

for

the

workin

this

thesis.Using

clayto

alludeto

somethingbeyond

my

expectation of utilitarian pottery

has

been

veryhelpful.

During

this

attemptto

translate sometrace

of memory orfeeling

into

a clavobject,

my

understanding ofthe

expressive potential ofclay

andthe

firing

process,

and of myexperiences,

THREE

SHORT

STORIES

My

first

trip

to

the

forest

river was madeon a

sweaty

summerday.

Walking

through

the

undergrowth of

ferns

andivys

filled

the

air withmoisture and

the

bittersweet

smell ofbroken

vegetationExcept

for

the

faint

sound offlying

insects,

everything

was quiet and still.At

the

edge ofthe

riverthere

was a sudden transitionfrom

thedim,

heavy

air ofthe

woodsto

thebright,

dry

air above

the

river.The

water was clearand,

until steppingin,

had

the

illusion

ofbeing

still.Sore

muscles,

sticky skin and mosquito

bites

wereinstantly

forgotten

in

the

cold water.Dark

shadows of troutflashed

across

the

colored stones anddisappeared

beneath

the glare of sunlight all around me.

Not

far

from

where

I

was standing there wa<= something goldenin

the

midst of aniridescent

shimmer.The

iridescense

was causedbv

the

silvery-blue sheenof a

colony

offresh

water clams.The

golden sparkleturned out to

be

a wristwatch with a slimyhalf

rotted

leather

band

still connectedto

one side.So

I

woundit

up andit

workedfine

for

severalyears until

I

lost

it

somewhere.Of

courseit

The

trout

never returned and soI

packed up myfishing

pole and some clams and continued withthe

hike

Not

far

from

the

riverthere

was an area wherethe

ground

began

to

be

soft.Eventually

this

turned

into

a narrow

band

of mud andthen

asmall,

stillbrook

nomore

than

eighteeninches

wide and afoot

deep.

For

some reason

I

decided

to

fish.

As

there

was no placeto

cast aline,

I

put a worm ontothe

hook

anddangled

it

overthe

water.Just

asthe

wormtouched

the

watera

fish

bit

atit

and gotitself

hooked.

The

fish

wasa small

brook

trout

withbright

pinkish-orangeblushes

on

its

sides andbelly.

Brilliant

speckles ofred,

green and yellow were scattered everywhere except

its

dark

greenback.

These

little

fish

continuedto

leap

out of

the

water andbite

atthe

worm wheneverit

waslowered

to

within about twoinches

ofthe

water.Eventually,

I

walked on.After

following

the

path ofthis

waterwayfor

aquarter mile or

so,

it

began

to

turninto

mud again andthen

soft ground.Apparently,

it

was either atiny

ribbon of surfaced ground

water,

or a streamthat

had

had

adirect

connectionto

theforest

riverduring

somepast springtime.

The

story about the wild rabbits andthe

tame

appleillustrations

atthe

end ofthese

words.This

story

developed

over a period of several years andhad

to

do

with

my

hobby

ofgrowing

apples and thebiggest

obstacle

I

had

to

overcome.While

inspecting

severalrecently

planted treesone summer

morning,

I

discovered

that

most ofthe

branches

had

been

bitten

off nearthe

trunk.So,

in

order

to

keep

out whateverhad

attackedthem,

I

positioned a

little

fence

around each tree.A

few

days

later

I

drove

up

the

driveway

at night and caught aglimpse of one rabbit

trying

to reach through afence

to

the

appletree

within.Several

other rabbits wentscurrying

away

in

the

light

ofthe

headlamps.

It

wasvery

satisfying

to

have

found

out and outsmarted theserabbits

in

just

afew

days.

The

trees

grew well therest of that

first

summer,

but

the

rabbitshad

notmade their

final

effort.During

the

course of thefollowing

winter,

sixor eight weeks passed without a thaw.

The

accumulationof snow was

four

tofive

feet

deep.

As

aresult,

the

cottontails could not reach

any

ofthe

vegetationthey

were accustomed to

eating

during

the

winter months.In

their

desperation,

they

decided

to

try

my

appletrees

once again.

The

snowhad

raisedthe

groundlevel

(for

a

light

footed

rabbit) tothe

sameheight

asthe

tops

they

were ableto

walk up and eatthe

tendertops

ofthe

trees

very

comfortably.Thev

atethe

entiresummer's growth and

then

some.There

is

a sensein

which

I

kept

the

rabbitsfrom

eatingthe

trees

during

the

summermonths,

whenthey

reallydidn't

needthem,

so

that

they

could eatthem

in

the winterto

keep

from

starving.

And

soit

has

gonefor

the

past severalyears: some summers

the

trees

put ontwo

feet

of newgrowth,

and some summersthey

regain what was eatenby

the

rabbitsduring

the

winter.Some

ofthe

weaker treesdie

in

the

process.The

one aboutthe

two

crows andthe

hawk

is

verysad.

I

have

long

felt

that crows arethe

mostobnoxious of all

birds.

One

day

an especiallyhideous

cawing

by

two of themlured

me outside toinvestigate.

They

were on ahigh

branch

taking

turns pecking at alarge

hawk

that wasstanding

between

them.I

wonderedwhy

this

greatbird

wastolerating

suchabuse,

whenit

suddenly

left

the

branch.

The

crowsfollowed

immediately

As

the

hawk

flew

awavrecklessly,

I

could see abloody

leg

dangling

severalinches

lower

than

the

hawk's

other

leg.

I

walked afterthem,

but

they

had

soonflown

out of view.The

hawk

was exhausted andthe

crowswould not

let

it

rest.It

was toobad

that

crowsThere

are manv other storieswhich,

like

these,

have

left

me vivid and accessible memories.These

experiences are more

than

just

easyto

recall;they

continually

fill

my mind withtheir

sights and soundsand

feelings.

As

the

memories and new experiencesoverlap and run

together,

thev

cause adeeper

awarenessand appreciation of nature.

Out

ofthis

fullness

comesa

desire

to

share whatI

have

learned.

Hopefully,

the

images

generated are as accessible and meaningfulON

IMAGE

AND

FORM

The

first

attempt attelling

one ofthese

storieswas a simple

line

drawing

through

athin

whiteslip

to

a

dark

clay

potbelow.

Every

image

that

was part ofthe

story

wasincluded.

The

shape ofthe

pot wasirrelevant.

It

wasprobably

naiveto

thinkthat

I

could

take

a stick and make adrawing

in

wetclay

thatexpressed

my

feelings

about nature.And

it

wasjust

as

unlikely

that

similarfeelings

mightbe

felt

by

someone else

if

they

consideredthe

drawing.

Still,

it

was a placeto

begin.

One

important

realization was that an experiencesuch a

wading

through aforest

riverhas

as muchto

do

withthe

other senses asit

has

with seeing.Another

was thattaking

someoneto

the

forest

riveritself

could not arousethe

feelings

that

I

had

felt.

In

fact,

returning

there myselfhas

never reproducedfeelings

like

the

onesI

recall.It

was adifferent

day:

the

air tasteddifferently,

my

motive wasdifferent

.Eventually,

I

cameto

realizethat

the

story

wasnot as

important

as theimages

andforms

the

story

important

image

orimages

allowedfor

a work that wasless

confusing

and more engaging.The

pots are stillnarrative,

but

the

curiosity

of a singleimage

promptseach person

to

usetheir

ownimagination

andinterject

their

own experiences.Substituting

carefully selectedlines,

colors andtextures

for

an abundance ofimagery

(whether

real orimagined),

resultedin

a moreinteresting

story.

This

is

notto

suggest thatby

"carefully

selected"I

am referring to aforming

process that was slow andmeticulous.

Once

a specific shape andimage

had

been

settled

upon,

a series of ten totwenty

pieces werethrown on

the

potter'swheel,

altered anddecorated

in

a

day

or two.All

ofthe

forming,

drawing

and coloring(except

for

the

colorimparted

by

the

fire)

wasdone

while

the

pieces were still malleable.Out

ofthis

relatively rapid

process,

I

was ableto

further

develop

a vocabulary of

drawing

and shaping possibilities.For

me,

thishelps

to

keep

the

workfresh

and alive.It

allows me

to

workintuitively

andbe

surprised oncein

awhile.

The

unforgiving act of engraving adeep

line

in

wet clay thrives on spontaneity andintuition.

The

thick and thin quality of thelines

was afunction

ofthe

depth

ofthe

lines

into

the

clay

andthe

angleto

which the toolhad

been

sharpened.Depth

tool.

By

inscribing

adeeper

line,

adarker

shadowwould

be

contrasted

withthe

adjacent surfaces and awider path was established.

The

dimension

of theline

was always a response

to

that

segment ofthe

image

whichthe

line

was producing.The

contourline

drawings

ofmany

artistshave

been

inspirational

because

theirlines

suggest

three-dimensional

form

across theflat

shapesthey

create.As

the

nature of my ownlines

became

morecomplex,

fewer

ofthem

were usedto

develop

a particularimage.

As

color,

texture

andthe

shape of the potitself

contributed

to

the

image,

the

quantity oflines

necessary was reduced

further

still.Sometimes

the

edges of an area of poured or

trailed

slip

createdlines

which were as

visually

active asthe

incised

lines.

Lines

which could suggest movement were also createdby

finger

painting

into

a thick application of slip.Finger

painting

in

slip

was also a means ofacheiving textures which could

be

usedto

suggestrippling

water,

trees or rabbitfur.

A

richtexture

which suggested

fur

could alsobe

obtainedby

drawing

a comb or coarse

brush

through the wet slip.Building

up two or more

layers

ofdifferent

colored slips withcut paper stencils over an undercoating of

slip

produceda subtle texture and

the

illusion

oftransparent

layers

and

depth.

The

texture causedby

the

salt-glazing

But

the

salt couldbe

usedto

addto

the

variety

oftextures

and colorsby

juxtaposing

areas ofslip

that

resisted salt with onesthat

did

not.Most

ofthe

color was achievedthrough

the

use ofthese

coloredclay

slips.Color

consistedprimarily

ofearthy

shades ofblue,

gray,

green,

brown,

white andblack.

For

the

mostpart,

color was usedliterally.

Blue

was usedfor

water andsky,

greenfor

afrog

orvegetation,

white orbrown

for

a rabbit and soforth.

On

the

most recentpieces,

black

was usedto

convey

death.

The

salt-glazing

processbrightened

these colorssomewhat and

the

ashfrom

the

wood-fire processdulled

them

somewhat.Manipulations

ofthe

fire

and theway

pots were

loaded

into

thekiln

producedflashes

oforange,

pink or red.

It

was much easier to producethese

atmospheric colors on

the

verticalforms

such as vasesand

jars

thanit

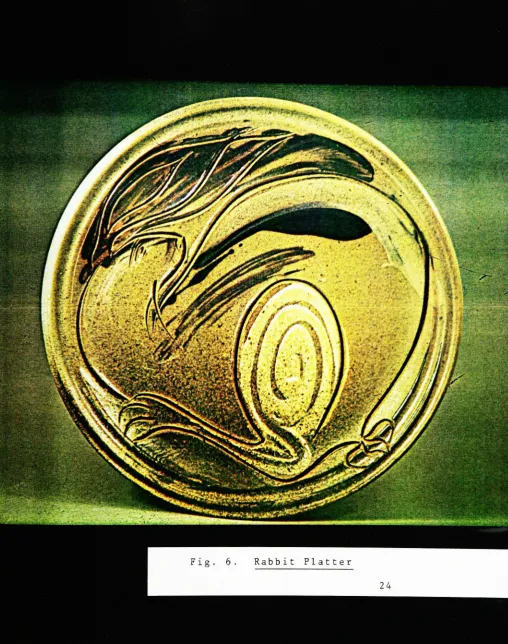

was on the platters.Platters

were chosenbecause

ofthe

large,

flat

areas

they

providedfor

drawing.

Historically,

platters

have

oftenbeen

usedfor

commemorative andnarrative

purposes,

andintended

for

hanging

or someother means of

display.

The

plattersin

this

body

ofthesis

work were alsointended

for

hanging

on awall,

inside

ah

ome .a

frame

to

contain and even constrictthe

centralimage.

By

preserving

the

roundness ofthe

rim,

a certaindistance

was createdbetween

the

viewer andthe

piece.When

the

inside

boundary

ofthe

rim wasinterrupted

by

the

drawing,

this

distance

waslessened.

And

whenthe

entire rim

had

been

alteredto

emphasizethe

shape ofthe

image,

there

was nodistance

andthe

sense ofcontainment and constriction was

lacking.

After

these

alteredplatters,

came altered vasesand

jars.

I

began

withdrawings

offrogs

in

variouspositions on

paper,

andthen

cutthem

out.By

considering

their

silhouttes,

it

was possible toidentify

apottery

shapethat

seemed appropriate orwould emphasize

the

image

ofthe

frog.

In

this

manner,

a

very

formal

relationship

between

the

image

andits

pot was established.

One

shape was madefor

afrog

diving

through

the

water,

onefor

asquatting

frog

andanother

for

adead,

floating

frog.

The

connectionbetween

the

image

andthe

pot wasfurthered

by

pressing

bulges

out of

the

pot which corresponded withthe

eyes,

abdomen and

legs

ofthe

frog

image.

Almost

every

culture with a ceramichistory

has

atradition of

pottery

forms

andimages

on pots whichare about nature.

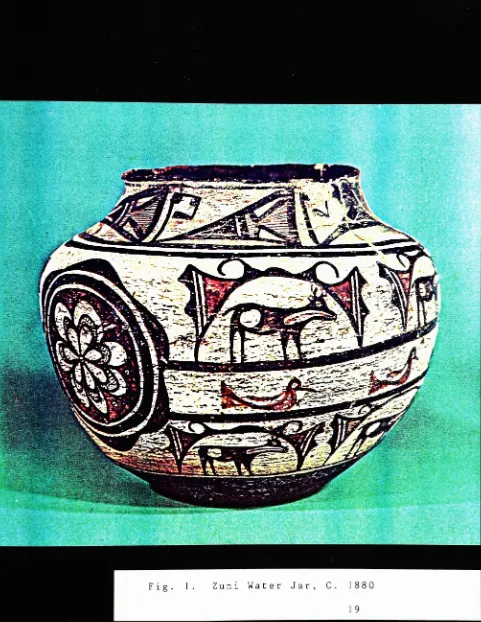

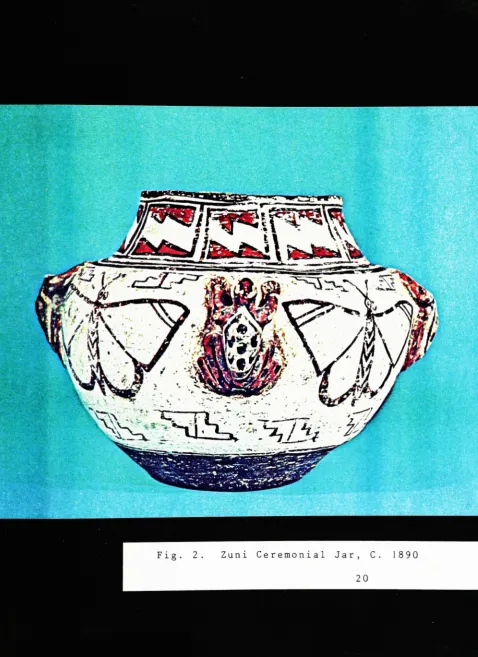

Zuni

Pueblo

Indians

used avariety

of motifs and

images

which symbolized anddepicted

water,

frogs,

tadpoles anddeer.

While

these

ceremonial potswere used

primarily

for

prayer andthanksgiving,

they

relect

their

users'direct

dependence

upon naturefor

survival and

inspiration.

Another

important

sourcefor

mehas

been

the

manyKorean

wares which suggest a more contemplative andappreciative attitude

towards

nature.The

soft celadonglazes over wine ewers

in

the

form

ofbamboo

shoots weremore about

their

attitudestoward

life

and naturethan

they

were aboutbamboo.

These

pots enabled theirusers to

bring

afragment

oftheir

natural surroundingsinto

their

indoor

living

spaces.They

providedthe

romantic

function

ofenriching

the

sterility

of aninterior

space andthe

occasion oftheir

use.This

desire

tobring

the

outdoorsindoors

can alsobe

observedin

eighteenth and nineteenthcentury

Japanese

architecture.These

architects perfected agradual transition

from

a natural space to a manicuredgarden to open porches and,

finally

to

interior

spacesenclosed with translucent panels.

Frank

Llovd

Wright

was

inspired

by

this

romanti

c/

organi

cideal,

anddeveloped

the

prarie styledwellings

that providethis

samekind

of outdoor

indoor

presence.The

attitudes ofthese

peopletowards

theirenvironments,

andhow

they

responded with whatthey

made,

has

been

helpful

in

the

development

ofmy

ownresponse .

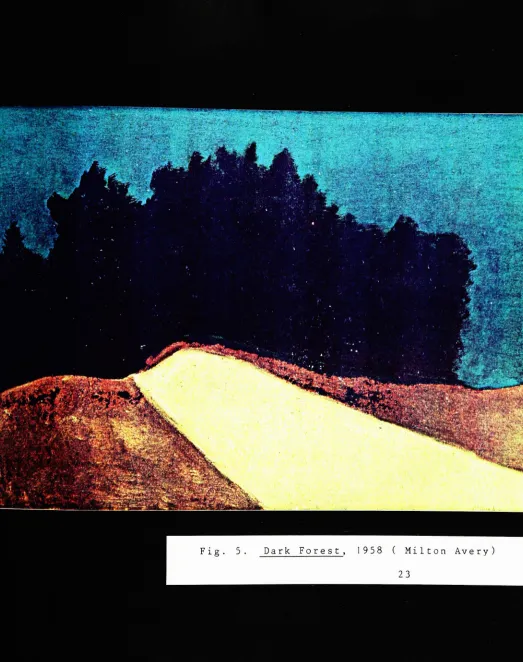

Milton

Avery.

In

his

workhe

managesto

expresshis

joy

of nature and capturethe

mood of a particularday,

or

hour

ofday.

At

the

sametime,

the

workis

generalenough

to

allow meimmediate,

personal participation.This

is

accomplishedthrough

his

ability

to

simplifywhat

he

has

seen,

and orderthese

simple shapes withina

key

ofharmonious

color.In

her

book

aboutAvery,

Barbara

Haskell

said:...

Avery's

work revealshis

deep

responseto

nature.His

landscapes

conveythe

grandeur of nature -

but

a nature whose

character

is

arcadian rather than alienand

threatening.

One

feels

looking

at anAvery

landscape

thatthe

highest

human

experience

is

being

alone and at peacewith

the

land.

Trying

to strike a meaningfulbalance

between

the

complex grandeur of nature and

the

simple experienceCONCLUSION

As

the

intentions

behind

the

potsI

wasmaking

gradually

shiftedfrom

utility

to

story

telling,

I

felt

less

andless

restrictedby

functional

necessity.A

long

time

passedbefore

I

was comfortable withthe

excessive weight caused

by

a potthat

was thick enoughto

accomodate adeeply

engravedline.

But,

towards

the

end,

making an expressivedrawing

onthe

surface of apot

became

moreimportant

than

the

potitself.

I

wasinterested

in

manipulating

the

shape,

color andtexture

of

the

potsin

any waythat

might enhancethe

narrativecontent of their

drawings.

In

the

process,

a moremeaningful

relationship

between

art andlife

has

been

established

for

myself.Pottery,

whether utilitarian ornot,

is

associated2

with

the

concerns oflife.

This

direct

connectionto

life

is

animportant

reasonfor

meto

work within apottery

format.

The

message around whichthe

potshave

been

structured was afurther

attempt to strengthenand clarify

this

connection.I

feel

thatthe

potis

anappropriate vehicle

for

my work.When

it

is

nolonger

appropriate or

hinders

the

message,

it

willbe

time

to

abandon

the

idea

ofthe

pot altogether.of

my

work a stepfurther.

Many

ofthe

beautiful

sights which

Milton

Avery

wrote and painted aboutduring

the

first

half

ofthis

century

aredestroyed

today.

The

environment

has

suffered moreduring

the

last

seventy-five

yearsthan

it

did

during

all previousrecorded

history.

A

statement madeby

Aldo

Leopold

parallels my own observation:

One

ofthe

penalties of an ecologicaleducation

is

that

onelives

alonein

aworld of wounds.

Much

ofthe

damage

inflicted

onland

is

quiteinvisible

to

laymen.

An

ecologist must eitherharden

his

shell and makebelieve

that

the

consequences of science are none of

his

business,

orhe

mustbe

the

doctor

whosees

the

marks ofdeath

in

acommunity

that

believes

itself

well anddoes

not wantto

be

told

otherwise.As

long

as artis

aboutitself

orthe

trivialities

oflife,

it

can affordto

be

so generalthat

it

becomes

universal and eternal.This

attitudeabout

art,

which was soinf luent

ial

ly

promotedby

4

Clement

Greenberg

and othertheorists

ofmodernism,

contributed much

to

the

presentimpotency

of art.Modernism

weakened artby

taking

the

concerns of artbeyond

the

concerns oflife.

This

is

notto

deny

the

tremendous contributions which

the

seige of modernismhas

brought

to art and artists.But

important

issues

that

effect everyone needto

be

brought

before

everyonein

a waythat

canbe

assimilatedby

everyone.The

deluge

of political art whichhas

sprung

up

around

the

issue

of nuclear armsin

the

past severalyears

falls

into

this type of clear and accessiblecategory.

Robert

Arneson

has

takenthe

risks ofbeing

this

specific and clear with some ofhis

recent ceramicwork.

Within

this

samecontext,

I

feel

a needto

attempta

body

of workthat

would raise questions concerningthe

lack

of environmentalresponsibility

so prevalenttoday.

When

I

talk aboutusing

artwork to explorethese

concerns,

I

amusually

admonished to considerthe

beauty

around meinstead.

Yet,

thatis

exactlyENDNOTES

Barbara

Haskell,

Milton

Avery

(New

York

Harper

&

Row

,1982),

p

.6

.'Wayne

Higby,

The

Vessel

:Ove

rcoming

the

Tyranny

of

Modern

Art

(NCECA

Journal,

Volume

3,

Number

1,

1982),

p.

11.

'Aldo

Leopold,

The

Mother

Earth

News

(Number

85,

January

1984),

p.6.

4

.Richard

Hertz,

Theor

ies

ofContemporary

Art

(Englewood

Cliffs,

New

Jersey:

Prentice-Hall

Inc

.,

1

985

)

,p

. xi .Fig

Zuni

Water

Jar,

C.

1880

[image:25.505.13.494.31.653.2]Fig.

2.

Zuni

Ceremonial

Jar,

C.

1890

[image:26.505.15.494.37.694.2]'**.

assi

Fig.

5.

Dark

Forest,

1958

(

Milton

Avery)

[image:29.544.11.534.30.692.2]**%

-*-Fig.

6.

Rabbit

Platter

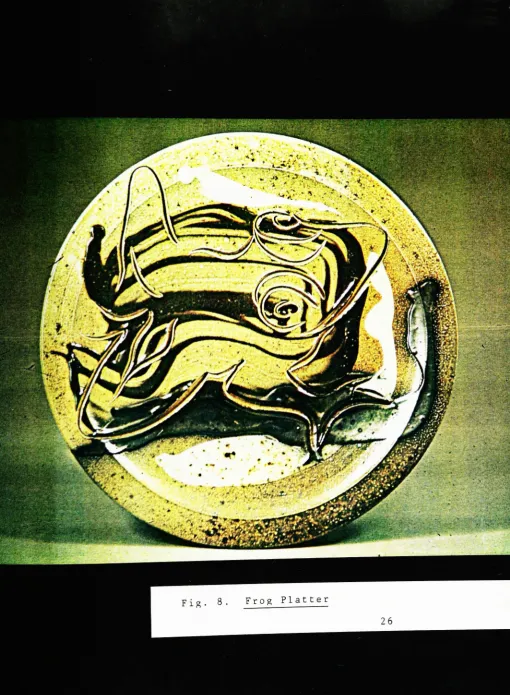

[image:30.522.9.518.41.685.2]Fig.

8.

Frog

Platter [image:32.522.11.522.18.713.2]J

^%ag^fe^^^M^i^w^^gg^^^l4' ,

\

\\

m

*<**,

!%,

:>\$''

m&

, .-.

'

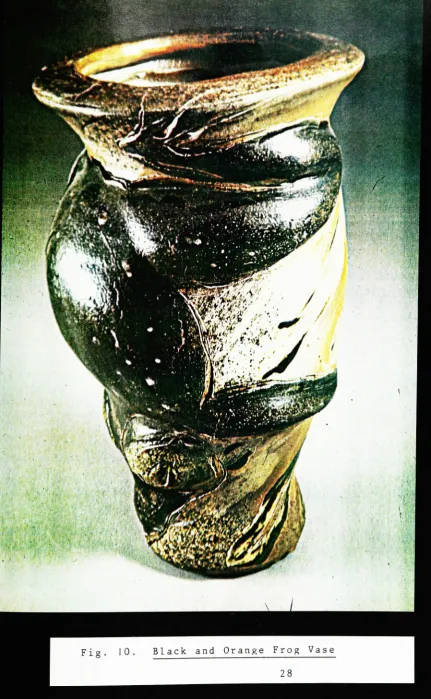

Fig.

10.

Black

andOrange

Frog

Vase

[image:34.505.37.469.8.708.2](h

?

itl

*&*'

'.**.'*'_:**

Ism.

\

I

('' >

W

'/

I

WW

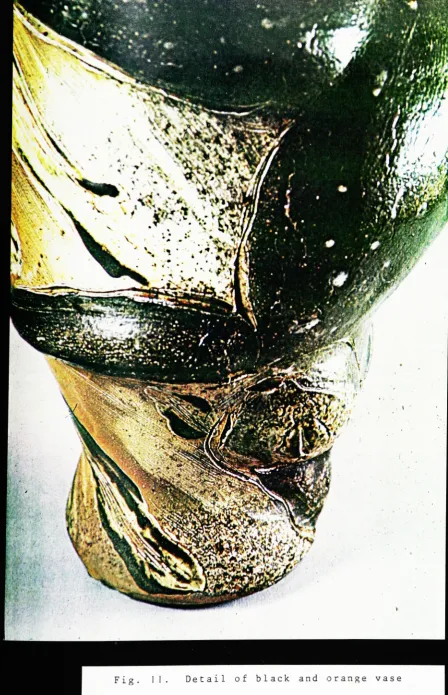

Fig.

1

1

Detail

ofblack

and orange vase [image:35.505.31.480.9.705.2]APPENDIX

A

CLAY

BODY

Batch

Formula

(Cone

10)

Grolleg

kaolin

25

poundsBall

Clay

25

poundsFireclay

25

poundsRed

art5

poundsAvery

kaolin

5

poundsCuster

feldspar

10

poundsFlint

10

poundsThis

clay

body

was very well suitedfor

thrown

and alteredforms.

It

dried

quickly,

without

cracking,

anddid

notslump

at cone12.

The

body

enduresonce-firing

and respondsAPPENDIX

B

SLIP

FORMULAS

(Cone

10)

White

slip

EPK

35

Ball

clay

25

Custer

feldspar

15

Fl

int

15

For

blue

add4%

cobalt carbonate andFor

brown

add4%

iron.

For

yellow add5%

rutile.For

black

add10%

black

Mason

stain.iron

Flashing

orangeslip

Grolleg

55

Avery

kaolin

50

Nepheline

syenite15

This

slip

workedbest

for

me whenit

was subjectedto mild

body

reductionbetween

cone012

and06.

The

sides ofthe

potsfacing

awayfrom

the

direct

path of

flame,

ash and salt seemedto

develop

thenicest shades of orange.

Green

slip

Some

very nice green slips andslip

glazes wereobtained

from

straightlocal

clays that weremixed with water and poured througha

100

meshscreen.

All

ofthe

above slips were applied to pots thatwere still malleable.

They

adhered to theclay

body

I

used atany

thicknessthey

were used.BIBLIOGRAPHY

Breeskin,

Adelyn.

Milton

Avery

.Greenwich,

Connecticut:

New

York

Graphic

Society

LTD.,

1969.

Brady,

J.J..

Mimbres

Painted

Pottery.

Albuquerque,

New

Mexico:

University

ofNew

Mexico

Press,

1977.

Frank,

Larry

andFrancis

H.

Harlow.

Historic

Pottery

of

the

Pueblo

Indians

1

600-1

800

.

Boston

,

Massachusetts:

New

York

Graphic

Society

LTD.,

1974.

Haskell,

Barbara.

Milton

Avery

.New

York:

Harper

andRow,

1982.

"~ " ~

Hertz,

Richard.

Theories

ofContemporary

Ar

t .Englewood

Cliffs,

New

Jersey:

Prentice-Hall

Inc.,

1985

.Higby,

Wayne.

The

Vessel:

Ove

rcoming

the

Tyranny

of

Modern

Art"!

Volume

3,

Number

1,

NCECA

Journal,

1 982

.Kim,

Chewon

andSt.

G.M.

Gompertz.

The

Ceramic

Art

of

Korea.

Great

Britain:

R.

MacLehose

andCompany

LTD,

1961.

Leopold,

Aldo.

"Let

theMen

andWomen

ofWisdom

Speak,"

The

Mother

Earth

News

No.

85

(January

1984),

6

.Lewis

,C

.S

. .Chronicles

ofNarnia

,The

Horse

andHis

Boy.

New

York:

Macmillan,

1970.

Martin,

Bill

Jr.

Spoiled

Tomatoes.

U.S.A.:

Bill

Martin

Corporation

for

Bonmar,

1970.

Rawson,

Phillip

S.

Ceramics.

Philadelphia:University

of PennsylvaniaPress,

1984.