Linda Miller, Emma Pollard,

Fiona Neathey, Darcy Hill

Gender segregation in apprenticeships

Linda Miller, Emma Pollard, Fiona Neathey, Darcy Hill and Helen Ritchie

Institute for Employment Studies

First published Spring 2005

ISBN 1 84206 140 2

EOC WORKING PAPER SERIES

The EOC Working Paper Series provides a channel for the dissemination of research carried out by externally commissioned researchers.

The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Commission or other participating organisations. The Commission is publishing the report as a contribution to discussion and debate.

Please contact the Research and Resources team for further information about other EOC research reports, or visit our website:

Research and Resources

Equal Opportunities Commission Arndale House

Arndale Centre Manchester M4 3EQ

Email: research@eoc.org.uk Telephone: 0161 838 8340

Website: www.eoc.org.uk/research

You can download a copy of this report as a PDF from our website, or call our Helpline to order a copy:

Website: www.eoc.org.uk/research Email: info@eoc.org.uk

Helpline: 0845 601 5901 (calls charged at local rates)

CONTENTS

PageTABLES AND BOXES i

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ii

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY iii

1. INTRODUCTION 1

1.1 Background 1

1.2 Gender segregation in MAs 2

1.3 Current statistics on MAs 5

1.4 LLSCs and their partner organisations 7

1.5 Structure of the report 10

2. METHODOLOGY 11

2.1 Interviews 11

2.2 Postal surveys of LLSCs 12

2.3 Case study research 13

2.4 Reporting data 13

3. THE CONTEXT FOR ACTION ON GENDER SEGREGATION 15

3.1 Tackling skill shortages 15

3.2 Enhancing training capacity 16

3.3 Providing labour market information 17

3.4 Data collection 18

3.5 Key groups for tackling gender segregation 21

3.6 Priorities and targets 23

3.7 Conflict and pressure in priorities 27

4. EXTENT OF ACTIONS TO TACKLE SEGREGATION IN MAs 30

4.1 LLSC actions 30

4.2 Actions by partner bodies 32

4.3 Connexions 35

4.4 Government programmes and initiatives 38

5. WIDER BARRIERS TO PROGRESS 42

5.1 Traditional attitudes 42

5.2 Segregation in MAs 46

6. CHALLENGING STEREOTYPICAL VIEWS 47

6.1 Developing publicity materials 47

6.2 Drama and discussion 51

6.3 Vocational options 53

7. RECRUITMENT AND EMPLOYMENT OF APPRENTICES 58

7.1 Employment of apprentices 58

7.2 Engaging with employers 63

7.3 Advertising apprenticeship positions 63

7.4 Availability of training provision 65

7.5 Pay and benefits of apprentices 66

Page

8. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS 76

8.1 The five sector perspectives 76

8.2 Overview of the research findings 77

8.3 Suggested ways forward 81

TABLES AND BOXES

PageTABLES:

1.1 Female share of Modern Apprentices in training, England, 2001 4 1.2 Modern Apprenticeship starts, England, 2002-03 6

3.1 Skill shortages in LLSC areas 16

3.2 Percentage of LLSCs stating whether demand for training could be met

by local providers 17

3.3 Use of data collected by LLSCs 20

3.4 Attempts to encourage partners to address equality issues 22 3.5 Sectors identified as priorities by LLSCs 25

4.1 Percentage of LLSCs taking action to address gender segregation in MAs 30

BOXES:

3.1 LLSC labour market information 18

4.1 EEF West Midlands Technology Centre - Birmingham 33 4.2 North London Garages Group Training Association 33 4.3 Horizon Housing Group Ltd, Changing Rooms Project 34 4.4 Prospects, Tottenham Connexions Service 36 4.5 North London Garages Group Training Association 39 4.6 3Es programme in Birmingham and Solihull 40

6.1 Birmingham and Solihull LLSC 48

6.2 Waltham Forest Chamber of Commerce Training Trust 50 6.3 Impact Theatre Group, Birmingham and Solihull 51 6.4 North Yorkshire Business Education Partnership 52

6.5 Derwent Training Association 55

6.6 4Real project, Birmingham 56

7.1 London North LLSC 63

7.2 EEF West Midlands Technology Centre - Birmingham 65 7.3 North London Learning Partnership Manager 71

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank David Perfect, Anne Madden, Sue Botcherby and David Darton at the EOC for their support and enthusiasm throughout the project.

We would like to thank the following individuals for their help and advice in designing the LLSC survey questionnaire:

• Colin Forrest (West Yorkshire LSC).

• Paul Kent (Shropshire LSC).

• Steve Pierpoint (South Yorkshire LSC).

• Sandy Zavery (Leicester LSC).

In addition, we thank all those individuals at the various Sector Skill Councils, the NLSC and at ALI who generously gave their time to be interviewed for the project:

• Ian Carnell and Phil Haworth (SEMTA).

• Richard Dorrance and Olivia Borthwick (EYNTO).

• Peter Lobban (CITB-ConstructionSkills).

• Karen Price and Christine Donnelly (e-skills UK).

• Keith Marshall and Kathryn Morgan (SummitSkills).

• Benita Holmes (National LSC).

• John Landeryou (ALI).

Our thanks also go to the many LLSC officers who made the effort at a busy time of year to complete and return the questionnaire.

We also wish to thank the many training providers, employers, apprentices and representatives of Education Business Partnerships, LLSCs and Connexions who agreed to be interviewed for the project as part of the case studies.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

In June 2003, the Equal Opportunities Commission (EOC) launched a General Formal Investigation into gender segregation in five occupational areas where there are skills shortages: construction, engineering, information and communication technologies (ICT) and plumbing (all male-dominated), and childcare (female-dominated). The investigation is being undertaken with funding from the European Social Fund (ESF).

This research focuses on apprenticeships. Previously called Modern Apprenticeships (MAs), these are currently the main vocational training route into work for young people in Britain.1 The aim of the research was to investigate what the National Learning and Skills Council (NLSC) and its local arms (LLSCs) have done within the 'investigation sectors' to address gender segregation in MAs. A further aim was to consider the actions taken by partner organisations that work with LLSCs, such as training providers, employers, the Connexions service, Sector Skills Councils (SSCs) and the Education Business Partnerships (EBPs).2

The research had thee elements: interviews with representatives of the sectors, the National LSC (NLSC) and the Adult Learning Inspectorate (ALI); a survey of all LLSC offices in England (42 out of the 47 responded); and case studies conducted in five LLSC regions (Birmingham and Solihull; North Yorkshire; London North; London South; and Devon and Cornwall).

KEY FINDINGS

Gender segregation in apprenticeships

Patterns of gender segregation in MA registrations across Britain mirror those seen in employment. The five investigation sectors are both amongst the most strongly segregated and those in which substantial skills shortfalls are reported. Indeed, at least two-thirds of the LLSCs that were surveyed reported some or extreme skills shortages in four of the five sectors: childcare, construction, plumbing and engineering. The majority of LLSCs also reported similar findings for ICT.

Sixty per cent of LLSCs regarded gender segregation as one of their priority issues. Nearly half (20) had taken action to address segregation in MAs in one or more of the investigation sectors. However, the proportion that had done so was much higher in

1 Partway through the research, Foundation Modern Apprenticeships were renamed Apprenticeships

and Advanced Modern Apprenticeships were renamed Advanced Apprenticeships.

some sectors than in others. Around two-fifths of LLSCs had taken some action in engineering and construction; however, only about a quarter had done so in childcare, a fifth in plumbing and 12 per cent in ICT.

Some LLSCs were also involved in national projects, such as JIVE and GERI, or were working with SSCs, while a number reported taking action to address gender segregation in non-investigation sectors.

Thirty LLSCs were able to provide data on the numbers of females and males starting and completing MAs in the five investigation sectors. However, many were unable to do so for all five, in particular for plumbing and ICT, in part because the various systems to collate and report statistics were not fully compatible.

No LLSC reported that it collected pay data for apprenticeships.

Three-quarters of LLSCs with Equality and Diversity Impact Measures (EDIMs) in place had developed one or more of these measures to address gender segregation. However, many of these either related to general intentions to raise the participation and attainment of young men in education and training, or were not focused on work-based learning.

LLSCs also experienced some conflict in prioritising their efforts, and reported that a lack of time, resources and specialist knowledge impeded their efforts to address gender segregation.

It was thought that the newer emphasis on completions, rather than starts, might make providers more cautious about recruiting apprentices from under-represented groups, since they might be perceived as being less likely to complete.

In addition to the systemic barriers identified above, interviewees and respondents in all stages of the research were agreed that there are a number of major barriers confronting organisations seeking to challenge gender segregation, both in general and specifically in MAs. These are:

• Traditional attitudes regarding the proper jobs for women and men.

• Social stereotypes.

• The poor image of some sectors.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Two further barriers affecting MAs were also identified. These were the lack of apprenticeship places, which is likely to impact more on under-represented groups than on applicants from majority groups; and the fact that training providers typically only become involved with apprentices after they have been recruited by employers. This restricts their ability to influence the diversity of apprentices recruited.

LLSCs, SSCs and training providers were agreed that funding incentives need to be put in place to encourage efforts to attract apprentices from under-represented groups.

LLSCs partner organisations

The case study research revealed a range of activities being undertaken by LLSCs, training providers, EBPs, SSCs, employers and the Connexions service. These actions included developing publicity materials; commissioning drama productions to raise the profile of the sectors and encourage applications from under-represented groups; and providing hands-on experience of these sectors to young people at school. Difficulties encountered by organisations in undertaking this work included a shortage of funding for the development of publicity materials (and a lack of knowledge regarding where to seek such funding), and a shortage of role models to feature in publicity materials.

LLSCs have contractual relationships with colleges, work-based learning providers and EBPs and were able to use this means to influence these partners. However, they saw employers, the Connexions service, SSCs and parents as being particularly well-placed to help reduce gender segregation in training and employment, but felt that they themselves were largely not able to influence these groups.

A number of LLSCs identified projects initiated in their regions by partners such as SSCs and training providers. Case study visits provided examples of providers’ activities that were designed to recruit atypical groups. Some providers had also designed new ‘feeder’ programmes to encourage women to take courses that could provide entry routes to MAs or National Vocational Qualifications (NVQs), while others were offering training and support to employers in equal opportunities and diversity.

Government programmes

As part of the survey, LLSCs were asked whether various government programmes that were being piloted, or had recently been introduced, would contribute towards challenging gender segregation in apprenticeships.

LLSCs were cautious about the extent to which the Entry to Employment (E2E) programme would result in more atypical recruits to apprenticeship programmes. However, several noted that it was helping to provide young people with the opportunity to experience a wide range of employment opportunities and evidence from the case study interviews with providers indicated that the initiative is proving successful in encouraging young people to try out atypical areas of work. In some cases, young people were gaining NVQ units in non-traditional areas while on the programme, and there were examples of them subsequently moving into apprenticeships.

There was no evidence that the Employer Training Pilots (ETPs) were providing an entry route into apprenticeships for atypical groups. Given that this programme is focused on older workers, it is unlikely to provide an entry route to apprenticeships in general until the age cap on apprenticeships has been removed.3

While the Adult Learning Grant (ALG) could be focused towards the needs of priority groups, only one LLSC had used the funding to encourage women to consider an atypical area, and so it was not possible to determine whether the programme would have any longer term impact on the recruitment of atypical groups.

Recruitment and employment of apprentices

Since 2003, apprentices have mostly needed to be in employment in order to commence an apprenticeship. Almost all partners saw this as a barrier to increasing the diversity of the apprentice population. A shortage of starter jobs limited the number of apprenticeship places available, and any such shortage of places was likely to impact more heavily on under-represented groups. The large number of small employers in construction and plumbing also restricted the availability of places. Providers and SSCs were nonetheless keen to retain employed status for apprentices.

The research revealed that some employers continue to discriminate against apprentices from under-represented groups in both overt and more subtle ways.

3 In May 2004, two months after the conclusion of the fieldwork for this project, the government

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

A number of apprentices who were interviewed reported that they lacked information about vocational options. This could in part be a reflection of the lack of consistency across LLSCs in terms of the provision of local labour market information (LMI). Only 17 made LMI available.

Funding problems had led to shortages in the numbers of college places available in some vocational areas. In one of the case study areas, a new feeder route programme had been designed to encourage women to move into construction trades, only for the intended destination NVQ programmes to close at the college.

Several young female apprentices had experienced bullying from other apprentices and one had been driven from her apprenticeship as a result. Training providers and LLSCs were concerned about the social isolation of apprentices from under-represented groups and some had taken actions to address this issue.

THE WAY FORWARD

On the basis of the evidence presented in the report, the authors make a number of suggestions:

Sound data collection

• LLSC management information systems are upgraded as a priority.

• Staff development is provided for LLSC staff to ensure that they are fully able to utilise existing systems and, subsequently, any new system introduced.

Targets

• The NLSC and LLSCs make better use of EDIMs to tackle gender segregation in sectors experiencing skills shortages.

Careers advisory roles

• Induction, training and continuing development programmes for those in careers advisory roles are reviewed to ensure that a proactive approach is taken to promoting young people’s options.

Information on vocational options

Funding issues

• Specific, ring-fenced, targeted, premium funding is provided centrally to enable LLSCs to take action to address gender segregation in apprenticeships. This is in line with the arguments made by the LLSCs themselves

Pay data

• The NLSC considers the best way in which to collect and report data on pay rates for apprentices; this might be possible through slight changes to the Labour Force Survey, or more readily obtained directly from employers as part of the apprentice registration process.

• Whichever approach is adopted, such data should be reported by gender, ethnicity and disability.

• All other SSCs are encouraged to follow the good example of those sectors which have ensured that there are publicly reported pay rates for apprentices.

Key role for employers

• LLSCs work with employers to encourage them to make a commitment to interview atypical applicants who meet selection criteria.

• LLSCs investigate the possibility of bringing together small employers to share the costs and benefits of an apprentice and co-ordinate this process if it is feasible.

• LLSCs and training providers work with employers to improve workplace culture and support mechanisms for trainees from under-represented groups.

Good practice dissemination

• The NLSC should take the lead in facilitating wider national dissemination of local successes. For example, it could establish a web-page at which LLSCs, training providers, EBPs and SSCs can post details of actions that are being tried out around the country, details of how they are being monitored, and, in due course, the extent of their success.

INTRODUCTION

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1 Background

In June 2003, the Equal Opportunities Commission (EOC) launched a General Formal Investigation into gender segregation in five occupational sectors where there are skills shortages: construction, plumbing, engineering, information and communication technology (ICT), and childcare. These five ‘investigation sectors’ remain amongst the most strongly segregated. In the case of construction, plumbing and engineering, and to a slightly lesser extent in ICT, the vast majority of the workforce is male. In contrast, in childcare, women account for the overwhelming majority of employees. The investigation is being undertaken with funding from the European Social Fund (ESF).

Gender segregation in employment is of concern for two other reasons: segregation into different areas of work remains a key factor contributing to the gender gap in earnings (Forth, 2002); and gender segregation contributes to continuing skills

deficits in the UK (Hewitt, 2001).1

The remit of the investigation also includes education and training. Previously called Modern Apprenticeships (MAs), apprenticeships are currently the main vocational

training route into work for young people in Britain.2 The White Paper 21st Century

Skills - Realising Our Potential (DfES, 2003) identified particular skills deficits in

intermediate skills at apprenticeship, technician, higher craft and associate professional level. These are the levels for which MAs prepare young people.

The EOC has commissioned a series of research studies to support the investigation. The first of these was carried out by the Institute for Employment Studies (IES). This work consisted of a review of research and an analysis of current labour market and training statistics in the five investigation sectors (Miller, Neathey, Pollard and Hill, 2004) and confirmed the extent of gender segregation in employment. It also revealed that MAs in these sectors remain extremely gender segregated.

In August 2003, the EOC also commissioned IES to conduct the second of the investigation research studies. As outlined in Chapter 2, its aim was to build on

1 On the basis of an analysis of the National Employers Skills Survey (Institute for Employment Research and IFF Research Ltd, 2004), the EOC concluded in its Phase One investigation report that there was a relationship between the under-representation of women in occupations and skills shortages (EOC, 2004).

earlier research on MAs, as well as the evidence uncovered in the first study, by investigating the actions that have been taken within these five sectors to address gender segregation in MAs. The main focus of the research was the actions taken by Local Learning and Skills Councils (LLSCs) in England to tackle gender segregation in MAs, since LLSCs have the primary responsibility for funding training and overseeing provider performance. A further aim was to consider the actions taken by the partner organisations that work with LLSCs, such as training providers, employers, the Connexions service, Sector Skills Councils (SSCs) and the Education

Business Partnerships (EBPs).3

1.2 Gender segregation in MAs

At present, patterns of gender segregation in registrations for MAs mirror those seen in employment. This has been the case since the introduction of MAs in 1995, as previous research has shown.

In May 1998, the HOST consultancy examined gender imbalances in MAs for the, then, Department of Education and Employment (DfEE) and the Local Government National Training Organisation (LGNTO). The researchers concluded that, rather than helping to break down gender stereotype barriers, MAs were adding to the problem of gender segregation in the labour market. The research indicated that social conditioning, parental and peer pressure, and fear of being ‘different’ from their friends, were barriers to young people moving into ‘atypical’ apprenticeships; while resource pressures, competing priorities and lack of monitoring information restricted the attempts of the, then, National Training Organisations (NTOs) to take action on gender imbalance. The study also found that, where action was taken to tackle gender imbalance, most often this was ‘unilateral’ - it was taken by NTOs, or by providers working on their own. The study observed that, to be most effective, initiatives needed to be co-operative and involve several stakeholders. In addition, the report observed that effective action would most likely be locally based and:

… informed by sound intelligence and in particular mapping the nature of imbalances and defining key sectors or geographical areas that need to be targeted.

(DfEE/LGNTO, 1998, p. 29).

A memorandum submitted to the Select Committee on Education and Employment by the NTO for engineering manufacturing (EMTA) also noted the strong gender segregation in the engineering sector (EMTA, 1998). It observed, furthermore, that while the image of engineering is a barrier to both women and ethnic minority groups,

INTRODUCTION

discrimination by some employers might also be a factor, particularly discrimination based on the belief that women are ‘not suitable’ for engineering. Its report concluded with a list of the various initiatives EMTA had undertaken to promote careers in engineering. These included the provision of resource packs for primary schools; videos to promote engineering in general and MAs in particular; support for New Deal advisors; and training packages for small and medium-sized enterprises.

In 1999, the, then, DfEE published research on the extent to which TECs (Training and Enterprise Councils, the forerunner organisations to the current LLSCs) were prioritising the issue of gender segregation within MAs (Quality and Performance Improvement Division, 1999). In particular, the study investigated whether TECs felt that they should address gender segregation in MAs and, if so, what their strategy was for doing so. It also considered the extent to which TECs were working with the careers service and with providers to tackle gender segregation and with employers to encourage non-discriminatory practices in recruitment. The research found that:

• The main priority equal opportunities issue for TECs was the

under-representation of people from ethnic minorities, with the under-achievement of young males and social exclusion of people with disabilities gaining increasing importance.

• The success in increasing the overall number of females participating in MAs

meant that the gender-segregated nature of participation tended to assume a lower priority.

• While gender stereotyping was seen as a constraint on young women, the

tendency of men to be clustered in some occupations and absent from others was not seen as being problematic by TECs.

• Not all TECs used their management information systems and monitoring

procedures to establish the participation rates of young women and men across different sectors of employment.

• TEC review and audit procedures of providers did not give a high priority to

equal opportunities and the challenging of gender stereotypes.

participation by MA framework and gender (see Table 1.1). Noting the extremely gender-segregated nature of these entry patterns to MAs, the Modern Apprenticeship Advisory Committee (MAAC) recommended that:

… concerted action [be taken] to address imbalances between the participation of young men and young women in particular sectors.

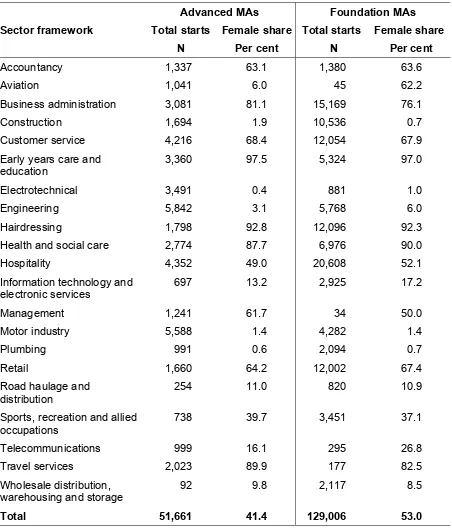

[image:17.595.68.524.240.655.2](Cassels, 2001, p. 46).

Table 1.1 Female share of Modern Apprentices in training, England, 2001

Per cent:

Sector Advanced MAs Foundation MAs

Engineering manufacturing 2 3

Business administration 81 77

Customer service 69 67

Construction 1 2

Motor industry 1 2

Electrical installation 1 *

Hotel and catering 50 50

Health and social care 89 89

Hairdressing 93 94

Retailing 58 60

Childcare 98 96

Accountancy 61 58

Plumbing 1 1

Travel services 89 84

Telecommunications 14 58

Information technology 22 16

Heating, ventilation, air conditioning and refrigeration

1 1

Printing 7 9

Road haulage and distribution 14 18

Management 59 *

Notes: Data are for young women.

Source: Cassels (2001), Annex D: participation by framework and gender.

INTRODUCTION

report highlighted sectoral and systemic barriers that are serving to perpetuate occupational segregation in MA training and work and are inhibiting the sustainability and success of local good practice. It recommended a range of early actions to break down these barriers because of evidence that the under-representation of women in key sectors of the economy is a major factor in skills shortages and is undermining productivity. Government and stakeholders have been invited to respond to the recommendations, in particular the call for a new national cross-government strategy to challenge occupational segregation (EOC, 2004).

1.3 Current statistics on MAs

The Cassels Review had been able to obtain statistics for these frameworks broken down to show participation by gender. These statistics were obtained from the DfES. However, between the reporting of the Cassels Review and 2003, when the first of the INVESTIGATION studies was conducted, responsibility for collating and reporting statistics on MAs had passed from the DfES to the National Learning and Skills Council (NLSC).

Miller et al. (2004) found that, as a result, statistics for MAs broken down by gender were no longer routinely made available in the public domain. Since the completion of the fieldwork for this report, however, an important new website has been developed by the NLSC to give up to date information on apprenticeship frameworks.

Data are now available on this website to show the total number of starts for each apprenticeship framework in each LLSC area. In each case, the female proportion of starts is shown (as is the proportion of starts made by people with disabilities and by

ethnic minorities).4 The latest available data on starts in England as a whole are

shown in Table 1.2.

In keeping with the observations of the 1998 DfEE/LGNTO report, these figures still largely reflect the general proportions of women and men employed in these sectors. For example, virtually all those starting construction, electrotechnical, engineering, motor industry and plumbing apprenticeships were male. Conversely, almost all those starting apprenticeship in early years care and education, hairdressing, and health and social care were female. Thus the data show that little progress has been made since the Cassels Review concluded and suggest that, at current rates of qualification and entry to the labour market, and in the absence of any further action,

apprenticeships will have little impact on the current segregation of the labour market.

Table 1.2 Modern Apprenticeships starts, England, 2002-03

Advanced MAs Foundation MAs

Sector framework Total starts Female share Total starts Female share

N Per cent N Per cent

Accountancy 1,337 63.1 1,380 63.6

Aviation 1,041 6.0 45 62.2

Business administration 3,081 81.1 15,169 76.1

Construction 1,694 1.9 10,536 0.7

Customer service 4,216 68.4 12,054 67.9

Early years care and education

3,360 97.5 5,324 97.0

Electrotechnical 3,491 0.4 881 1.0

Engineering 5,842 3.1 5,768 6.0

Hairdressing 1,798 92.8 12,096 92.3

Health and social care 2,774 87.7 6,976 90.0

Hospitality 4,352 49.0 20,608 52.1

Information technology and electronic services

697 13.2 2,925 17.2

Management 1,241 61.7 34 50.0

Motor industry 5,588 1.4 4,282 1.4

Plumbing 991 0.6 2,094 0.7

Retail 1,660 64.2 12,002 67.4

Road haulage and distribution

254 11.0 820 10.9

Sports, recreation and allied

occupations 738 39.7 3,451 37.1

Telecommunications 999 16.1 295 26.8

Travel services 2,023 89.9 177 82.5

Wholesale distribution, warehousing and storage

92 9.8 2,117 8.5

Total 51,661 41.4 129,006 53.0

Notes: Data are for periods 1-12 (August 2002 - July 2003). The frameworks shown are those in which there were a minimum of 1,000 MA starts in total during this period.

[image:19.595.71.523.154.684.2]INTRODUCTION

Similar figures for the five investigation sectors were reported for Scotland by Miller et al. (2004). Further evidence was provided by another recent study (Thomson, McKay and Gillespie, 2004), which was commissioned by EOC Scotland to support the investigation. This found that, in Scotland, men predominate in the sectors in which apprenticeships have traditionally been found, such as engineering and plumbing. However, women form the majority of those in MA frameworks for occupations in which the notion of training through apprenticeship is a new one, such as business administration and hairdressing.

1.4 LLSCs and their partner organisations Learning and Skills Councils

In April 2001, the National and local Learning and Skills Councils were formed and took on the majority of the responsibilities that previously were the remit of the Training and Enterprise Councils. They fund all post-16 provision outside HE. Thus their remit extends to school sixth forms and sixth form colleges as well as further education colleges, specialist colleges and work-based learning providers.

The NLSC sets policy and takes a strategic role nationally, while its local offices (there are 47 at present) implement those policies locally within the region they serve. However, LLSCs are able to take strategic decisions that relate to the particular needs of their locality. This includes taking actions to respond to local skills needs, for instance by deciding to fund more courses or places in particular occupational areas in which there are local skills deficits.

In addition to funding post-16 continuing education, the other key role of LLSCs is to oversee the performance of local providers (colleges, work-based learning organisations etc.) including the way in which these providers are promoting equality as part of their provision. LLSCs are the co-ordinating bodies to which providers submit self-assessment reports and to which the Adult Learning Inspectorate and (for some institutions, primarily but not exclusively, school sixth forms and sixth form colleges) Ofsted submit their post-inspection reports.

It should also be noted that the NLSC is one of the few public sector bodies which has a duty to promote equality of opportunity between women and men.

Adult Learning Inspectorate

The Common Inspection Framework (CIF) sets out the seven areas within which inspectors will consider the performance of training providers. The seven questions that inspectors consider are as follows:

• How well do learners achieve?

• How effective are teaching, training and learning?

• How are achievement and learning affected by resources?

• How effective are the assessment and monitoring of learning?

• How well do the programmes and courses meet the needs and interests of

learners?

• How well are learners guided and supported?

• How effective are leadership and management in raising achievement and

supporting all learners?

The area of ‘leadership and management’ includes consideration of the extent to which institutions are achieving equality objectives. Post-inspection reports on training provider performance are forwarded to LLSCs to inform their decisions regarding provider performance and funding.

Education Business Partnerships

Although some EBPs have a longer history, the majority were established during the 1990s, with the following aims:

• Preparing young people for the world of work in particular and adult life in

general.

• Raising teacher awareness of the world of work and the work-related

curriculum.

• Contributing to the raising of standards of achievement via work-related

contents.

• Supporting the business community in its need to create a world class

competitive workforce for the future.

INTRODUCTION

There are now 138 EBPs across the 11 regions of England, Wales and Northern Ireland. There is a range of models for their operation, but in general the term refers to a partnership between educational and business organisations aimed at developing and promoting sustained links for the benefit of students, local schools and colleges. They contract with LLSCs to offer the following services:

• Work experience.

• Mentoring.

• Visits to the workplace.

• Enterprise activity.

• Professional development for teachers.

Sector Skills Councils

At the time of the research, the Sector Skills Councils (SSCs) were being formed. Their role will be to take on the responsibilities that had previously been the remit of NTOs and, prior to that, of the Occupational Standards Councils, Industry Lead Bodies and Industry Training Boards. This includes overseeing qualification development, so that awards are appropriate for the purposes of their sector, and training provision. Of particular interest in the context of this research is the role of SSCs as overseers of the frameworks for MAs, and their relationships with employers in seeking to promote the availability and uptake of MA training places. Their contract with the NLSC includes agreements regarding target intake numbers for MAs in any one year.

of the interview, therefore, the Early Years National Training Organisation (EYNTO)

was engaged in a holding operation to provide some continuity in the sector.5

1.5 Structure of the report

Chapter 2 outlines the methodology used in the research. Chapter 3 discusses which groups should play the key role in tackling gender segregation and considers their incentives for action. Chapter 4 describes what LLSCs and other bodies have done to tackle gender segregation in MAs. Chapter 5 examines barriers to progress, both generally in reducing gender segregation and specifically in MAs. Chapter 6 discusses the actions taken by stakeholders to challenge stereotypical views. Chapter 7 considers issues affecting the recruitment and employment of apprentices. Chapter 8 presents the conclusions and outlines the suggestions of the research team regarding the way forward.

METHODOLOGY

2. METHODOLOGY

The current study consisted of three components:

• Interviews were conducted in September or October 2003 with key stakeholders

within the sectors, the SSCs and the NTOs; the NLSC; and the ALI.

• A survey was carried out of all 47 LLSCs in England in late 2003.

• Case studies were undertaken between January and March 2004 in five LLSC

regions in which good practice had been identified by the survey.

2.1 Interviews

Interviews were conducted with:

• SEMTA - the science, engineering and manufacturing SSC.

• CITB-ConstructionSkills - one of the partner organisations within

ConstructionSkills, the construction industry SSC.

• e-skills UK - the SSC for the information technology and communications

sector.

• SummitSkills - the organisation that was in the process of submitting a proposal

to become the SSC for the plumbing, heating and ventilation sector.

• EYNTO, which was fulfilling a ‘caretaker’ role while issues concerning the

composition of the SSC for the childcare sector were being resolved.

Seven representatives of the SSCs/NTOs were interviewed face-to-face about the issues relating to MAs and gender segregation within their sectors, with a further three contributions by telephone interview and e-mailed questionnaire. In the following sections, we typically refer to the sectoral interviewees as ‘the SSCs’ or ‘SSC representatives’; where we do so, we mean by this the representatives of the three sector skills councils, the provisional sector skills council and the NTO.

Interviews with the NLSC and ALI

2.2 Postal survey of LLSCs

A postal survey of all 47 LLSCs in England was conducted. The draft questionnaire had been piloted with officers of four LLSCs prior to distribution and some modifications were made to it as a result of this process. The option of electronic completion and return was also made available where required. The survey returns were confidential and responses from individual LLSC survey responses are not identified in this report.

The survey asked for five types of information:

• Estimates of skills gaps and the ability of local providers to meet training needs.

• Data relating to numbers of females and males in MAs in the locality and

current pay rates.

• Descriptions of local initiatives undertaken by the LLSC and/or by partner

organisations.

• Any evidence that national pilots operating at the time of the survey were

impacting on gender segregation.

• Views on the parties best placed to counteract gender segregation and the

methods that LLSCs found most effective in encouraging partner organisations to take action to challenge gender segregation.

At the suggestion of one of the LLSC officers who had piloted the questionnaire, questions on the Adult Learning Grant and on special projects were also included. Another suggested requesting information on modern apprenticeships separately for the age groups 16-19 and 19 and over, as LLSCs themselves reported these groups separately. In order to meet a request from the DfES, questions were also included about the extent to which the Employer Training Pilots (ETPs) and Entry to Employment (E2E) had revealed examples of good practice in addressing gender segregation. It should be noted that both were relatively new government initiatives and that, as their name implies, the ETPs were still being piloted at the time of the research.

METHODOLOGY

far responded should do so. This generated further responses and in total, 42 questionnaires were received, representing a response rate of 89 per cent.

2.3 Case study research

The information from the LLSC survey was used to identify five regions for the subsequent good practice case studies. While the research was primarily designed to gain information on the actions taken by LLSCs themselves, the EOC was also interested in gaining information on actions taken by other organisations in the region (primarily providers). This information was therefore also taken into account in the selection process. The three considerations influencing the selection were:

• The range of initiatives reported by each LLSC in its survey response.

• The number of atypical apprentices (i.e. apprentices from the

under-represented gender) currently registered in each LLSC region.

• The geographical distribution of the LLSCs.

Using this information, the EOC selected five LLSC regions for the case studies in discussion with the research team: London North, Birmingham and Solihull, North

Yorkshire, Devon and Cornwall, and London South.6

In each case study, the intention was to interview, where possible:

• Representatives of the local LSC.

• Representatives of the local Connexions office.

• Representatives of the local college or training provider at which the atypical

apprentices were registered.

• Employers of the atypical apprentice(s).

• Apprentices.

2.4 Reporting data

Throughout the report, we adopt the following convention in reporting data obtained in the various phases of the work:

• As indicated in section 2.2, responses to the postal survey of LLSCs were anonymous, and therefore are not attributed to individual LLSCs, except where specific good examples of information or practice already in the public domain are cited.

• Comments from interviews with SSC representatives are attributed to the

relevant SSC.

• Where information on good practice from case study interviews with LLSC,

provider, EBP and Connexions representatives is cited, these are identified in the report.

• Where examples of poor practice were identified during the case study visits,

we have not identified the region from which the comment originated.

• The very small numbers of female atypical apprentices in the regions visited

would render them particularly prone to identification were either the location or the occupational sector to be given. For this reason, we do not give any details regarding our female apprentices other than whether they were undertaking a foundation or advanced modern apprenticeship.

• The quotes from interviewees were checked with respondents in July and

THE CONTEXT FOR ACTION ON GENDER SEGREGATION

3. THE CONTEXT FOR ACTION ON GENDER SEGREGATION

Chapter 3 sets out the broad context within which the local and national stakeholders operate. It starts by considering the nature of local skills shortages, training capacity and the provision of labour market information, as these factors can influence the ways in which LLSCs can address gender segregation. Next, we examine, from the perspective of the LLSCs, the contribution of key groups and organisations in tackling gender segregation at a local level. The final part of the chapter considers the priorities and targets of the local and national stakeholders to assess the degree of priority given to work on segregation.

3.1 Tackling skills shortages

Given that gender segregation has been identified by the EOC as contributing to skills shortages, one of the issues examined as part of the research was the question of whether pervasive local skills shortage led to action being taken either on gender segregation within MAs or in general, and either within the specific sectors examined as part of the investigation or more widely. As demonstrated both by the recent National Employer Skills Survey (Institute for Employment Research/IFF Research Limited, 2004) and the first IES study (Miller et al., 2004), some of the sectors identified for study by the EOC were those for which amongst the most extreme skills shortages had been reported nationally. In some cases, national bodies (such as CITB-ConstructionsSkills in construction and both SEMTA and the ETB for engineering) had made explicit reference to the need for a more diverse recruitment pool to be attracted to the sector if current skills shortages were to be remedied.

LLSCs were therefore asked about the extent to which skills in the five investigation sectors were in demand (‘extreme skills shortage’ or ‘some skills shortage’), skills demand was balanced with supply, or there was skills oversupply ('some skills oversupply’ or ‘skills oversupply and unemployment’) within their locality. Their responses are shown in Table 3.1.

Skills shortages were reported in all five of the named sectors. The most extreme shortages were reported in construction and plumbing. In both cases, almost all LLSCs reported either ‘some’ or ‘extreme’ skills shortages. In addition, more than three-quarters of LLSC respondents reported some or extreme skills shortages in engineering and childcare, but around a fifth stated that skill supply matched demand for skills.

oversupply of skills, with four LLSCs reporting some skills oversupply and one

[image:29.595.67.528.170.338.2]reporting skills oversupply and unemployment.

Table 3.1 Skills shortages in LLSC areas

Per cent:

Category of response Childcare Construction Plumbing Engineering ICT

Extreme skills shortage 18 34 32 8 3

Some skills shortage 60 63 65 72 54

Balance between skills supply and demand

23 2 3 21 31

Some skills oversupply 0 0 0 0 10

Skills oversupply and unemployment

0 0 0 0 3

Base: 40 41 40 39 39

Source: Survey of LLSCs, 2003.

3.2 Enhancing training capacity

As indicated in section 3.1, action to tackle gender segregation may arise from an awareness of local skills shortages. However, skills shortages can arise for many reasons. One reason may be the lack of applicants for courses or programmes offered in areas of skills shortage. However, skills shortages may also arise from capacity constraints in the provision of training places in these areas. Where restricted numbers of training places are available, this can make it much more difficult for any atypical groups to gain access to such courses or programmes.

For this reason, LLSCs were asked to comment on the extent to which local training providers were able to meet demand for courses in the five areas. While there are weaknesses with this measure (there may be sufficient places because there is negligible demand, for example), it nonetheless helps to give a more detailed picture of the source and nature of difficulties in meeting skills requirements. Data were requested for two separate age groups, 16-18 and 19 and over, as the LLSCs’ own funding structure differentiates between these two.

THE CONTEXT FOR ACTION ON GENDER SEGREGATION

[image:30.595.69.535.175.441.2]proportion of LLSCs reported that providers were unable to meet the demand from young people for training.

Table 3.2 Percentage of LLSCs stating whether demand for training could be met by local providers

Per cent:

Construction Childcare Plumbing Engineering ICT

16-18 19+ 16-18 19+ 16-18 19+ 16-18 19+ 16-18 19+

Not able to meet demand

10 10 5 0 20 18 0 0 5 3

Able to meet some of demand

45 50 33 33 50 55 32 34 26 29

Able to meet most of demand

33 28 44 50 20 18 47 45 45 45

Able to meet all of demand

13 13 18 18 10 10 21 21 24 24

‘Most’ plus ‘all’ 45 40 62 68 30 28 68 66 68 68

Base (N): 40 40 39 40 40 40 38 38 38 38

Source: Survey of LLSCs, 2003.

3.3 Providing labour market information

Local LSCs are also charged with distributing up-to-date labour market information (LMI) for their region. Provision of information about the sectors in which jobs are likely to be available (and, conversely, likely to be scarce) is intended to help individuals make decisions about training that will maximise their chances of employment. While the provision of LMI is not directly related to the goal of reducing gender segregation, providing such information may indirectly result in more individuals applying for atypical jobs where they are able to see there is a high demand for employees in those areas.

… [via] Connexions - LSC is not permitted to perform direct delivery of services.

It was clear that some LLSCs had put a great deal of thought into providing up-to-date LMI for young people in an attractive and accessible format. Two that particularly stood out were those from Coventry and Warwickshire and from Hertfordshire:

Box 3.1 LLSC labour market information

Coventry and Warwickshire LLSC has produced a floppy disk that sets out labour market forecasts from 2003-10. The envelope features a photograph of a diverse group of young people.

Hertfordshire LLSC has devised a website (which it runs in conjunction with Job Centre Plus) that contains all relevant information about jobs within the region. The current intention is to update the job trends data until 2008. The data forecast Hertfordshire employment trends by occupation across this timeframe, identifying wholly new jobs as well as those arising from turnover. As well as giving information about the qualifications that are required and the average pay levels, the site also gives information on possibilities for training, average length of service and the level of competition that an individual can typically expect when trying to enter an occupation (see www.jobtrends.co.uk for further details).

As indicated above, 14 out of the 17 LLSCs that made labour market information available to young people did so via their local Connexions offices. However, the link between the provision of information about areas of skills shortage and potential employment opportunities was not viewed by all Connexions offices as pertinent to the advice they provided for young people:

Although we do not work in isolation from the local labour market and we do look at the labour market, skills gaps are not so much a concern for Connexions. Society may need more men in childcare but Connexions are there to support individuals not solve society’s problems. However we do

work with partners who are concerned about skills gaps.

Case study interview, Connexions PA

3.4 Data collection

Starts and completions on MAs

THE CONTEXT FOR ACTION ON GENDER SEGREGATION

Thirty-eight of the responding LLSCs (90 per cent) reported that they collected data on males and females starting and completing MAs. Thirty supplied data. However, providing the data broken down by framework and gender caused difficulties for many LLSCs. Some were simply unable to supply data at all at present. One response was that:

This [information] is not currently available using this sector split but will be available shortly.

For others, while they were able to supply some data, they were unable to disaggregate it to provide information relating specifically to the areas of interest. The two areas that caused most difficulties were plumbing and ICT. Nine of the 30 LLSCs (30 per cent) which provided us with data were unable to report figures for plumbing. Many reported that statistics for plumbing were collected as part of the construction figures and they were unable to disaggregate these.

Similar difficulties were raised for engineering and ICT. One reported that ICT fed into engineering, while another stated that engineering was included within ICT. Similarly, several LLSCs reported that they could only supply data for clusters (e.g. engineering, technology and manufacturing; health, social care and public administration). This led several to provide data for the health, social care and public services grouping because they were unable to provide figures for childcare on its own. Others were more used to providing composite figures for work-based learning, or for various funding streams, rather than for occupational sectors.

These limitations on data had arisen for historical reasons in some cases. For example, plumbing originally had been part of the construction sector, but by the time this research was conducted had been a separate NTO for many years. Nonetheless, as indicated above, many of the LLSCs continued to collect and report data for plumbing combined with construction. This did not facilitate monitoring by the various sector skills councils:

I need data on plumbing, not construction. But the construction sector data is all aggregated together … It means more work for me to get the right stats. So we [SummitSkills] intend to take on registration because we do not get the right stats from the [N]LSC and they say they do not intend to change because of the implications for long-term statistics.

SummitSkills

We are provided with data by the [N]LSC but it is in sector groupings, [engineering in with manufacturing etc.,] so we collect our own data by visits to the [L]LSCs …

Attempts were being made to address the difficulties at the time of the research:

In transferring data collection responsibilities to the [N]LSC, the agreement was to continue with reports in the same format for one year. The data came in from the local TECs, but they all had different computer systems. Data could be broken down by starts, age etc., and this information was sent on to the SSCs.

Responsibility for the Statistical First Return was passed to the [N]LSC. But with Modern Apprenticeships the data now need to be interpreted in a more useful way. We are currently trying to resolve this in terms of resourcing.

We want to be able to analyse by framework crosstabulated with, for example, ethnicity and local area. But we have not yet reached a decision about how to arrange this. We are intending to set up an Equal Opportunities Working Group with regard to MAs.

NLSC

As noted in 1.2, since the completion of the fieldwork, an important new website has been developed by the NLSC to give up to date information on apprenticeship frameworks, including by gender, ethnicity and disability.

Use of data

LLSCs were asked the purposes for which they used the data that they collected relating to MAs.

Table 3.3 Use of data collected by LLSCs

Per cent:

LLSCs using data on

Report to National LSC

Evaluate success of local initiatives

Monitor employer performance

Monitor training provider performance

MA registrations 38 57 17 88

MA completions 36 55 17 83

Notes: Base = 42.

Source: Survey of LLSCs.

THE CONTEXT FOR ACTION ON GENDER SEGREGATION

Rates of pay

Earlier research conducted by the EOC in 1999 revealed that rates of pay for apprentices in female-dominated sectors are lower than in male-dominated sectors (EOC, 2001). The EOC had obtained data on pay from a small number of TECs that had collected this information. It is currently not possible to obtain this information through analysis of the Labour Force Survey; neither is it a requirement for LLSCs to collect or make available as part of LMI, information on rates of pay in MAs. However, given that at least a small number of the TECs that had preceded the LLSCs had collected this information, it was of interest to determine whether any LLSCs were in fact currently collecting data on rates of pay for MAs. However, no LLSCs that responded to the survey reported that they were collecting these data.

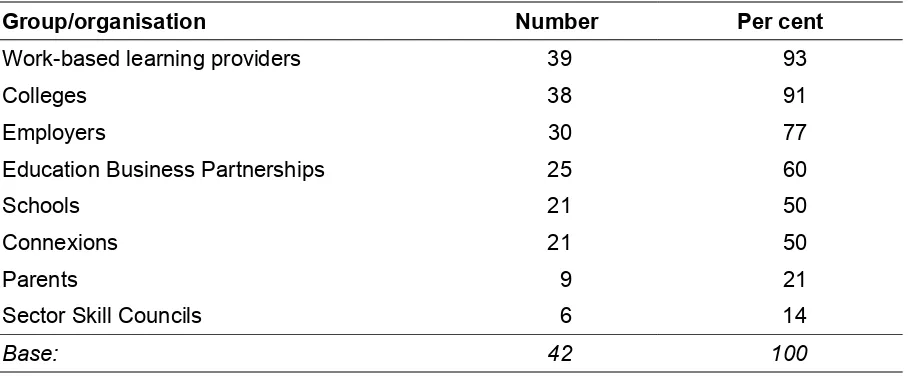

3.5 Key groups for tackling gender segregation

A wide range of groups and organisations other than LLSCs can play a part in challenging gender segregation at a local level. These include parents, schools, colleges, employers, work-based learning providers, the SSCs and NTOs, EBPs, and Connexions. LLSCs were asked in the survey to identify how influential each of these partner organisations was considered to be in challenging gender segregation. While the survey findings confirmed the importance of all of them, some were considered more influential than others.

LLSCs saw three of these partners - employers, Connexions, and SSCs - as being particularly influential, but other groups, including colleges, work-based learning providers, the NLSC, schools and EBPs were also viewed as being in a strong position to challenge gender segregation. Parents were seen as very influential, and many acknowledged that LLSCs themselves could be influences in this regard. However, there was no clear consensus regarding the extent to which any one group or organisation might be in the strongest position to challenge gender segregation, and this probably reflects that fact that all parties have a role to play. The need for all parties to be involved was reflected in the comments made by respondents:

All of the above organisations/agencies are in a strong position to challenge this issue. Improvement would be most quickly achieved if all of the above worked together to effect change.

There are a significant number of people that influence individual learners as they undertake the process of deciding upon their career and any future learning. Therefore, work should be undertaken on a collective basis between the full range of partners involved in the decision making chain to address the issues faced in challenging stereotyping.

Other points that emerged from the comments included the key role that Connexions can play in challenging young people’s choices. While employers are seen as being in a potentially influential position, respondents also acknowledged that there was also a need to influence and challenge the views of some employers. One noted that:

SSCs/NTO should be able to challenge employers who are probably the main organisations that need to be challenged regarding working practices and cultures. They could have the biggest effect on changing current practices.

LLSC survey response

LLSCs were asked whether they had tried to encourage any of their various partners to address equality issues. Most had tried to encourage a number of different partners. However, as Table 3.4 shows, colleges, work-based learning providers and employers were most frequently the target of such actions.

Table 3.4 Attempts to encourage partners to address equality issues

Group/organisation Number Per cent

Work-based learning providers 39 93

Colleges 38 91

Employers 30 77

Education Business Partnerships 25 60

Schools 21 50

Connexions 21 50

Parents 9 21

Sector Skill Councils 6 14

Base: 42 100

Source: Survey of LLSCs, 2003.

[image:35.595.70.524.361.552.2]THE CONTEXT FOR ACTION ON GENDER SEGREGATION

effective means of encouraging EBPs to take action on equality issues. There is no contractual relationship between LLSCs and Connexions offices, although the survey provided some evidence of the development of shared strategies and close working links between a minority of Connexions and LLSCs. For employers and schools, there was less direct LLSC involvement and more examples of the LLSC trying to influence these partners via intermediaries.

Asked if they had found any of these groups or organisations to be particularly helpful to them in addressing gender segregation, 22 LLSCs (52 per cent of respondents) identified one or more of their partners. Connexions was named by six LLSCs and SSCs by five. Five LLSCs mentioned that providers were particularly helpful, while four mentioned EBPs.

3.6 Priorities and targets

The current priorities and targets of the LLSCs and their relevant partners are likely to have an impact on their capacity to take action to address gender segregation. Priorities may be influenced by a range of considerations: targets set by government; limited resources; and the employment and training situation within the location or the occupational sector. The earlier work by DfEE/LGNTO (1998) had indicated that competing priorities could lead to gender segregation ‘dropping off the agenda’. The main priority issue for TECs then was the under-representation of people from ethnic minorities, with the under-achievement of young males and social exclusion of people with disabilities assuming increasing importance.

For this reason, we explored the priorities and targets of the LLSCs and the five SSCs/NTOs with regard to gender segregation, MAs, and the investigation sectors.

LLSCs

Gender segregation and other priorities

LLSCs were asked in the survey whether addressing gender segregation was a priority issue for them at present. Sixty per cent of those who responded said that it was. In addition, LLSCs were asked whether they had identified any other issues as priorities. Those identified by at least four LLSCs were:

• Disability/special needs/learning difficulty.

• Race/black and ethnic minority participation/attainment.

• 14-19 or 16-18 agenda.

• Male participation/achievement.

A number of these were similar to those noted in the 1998 DfEE/LGNTO study.

Equality and Diversity Impact Measures

In 2003, the NLSC gave all LLSCs the task of developing Equality and Diversity Impact Measures (EDIMs) by which progress in meeting equality targets could be assessed for their locality. It was left to each LLSC to decide appropriate EDIMs for their locality and therefore they reflect perceived local priorities in terms of targets to be monitored. Thirty-six LLSCs (86 per cent) had EDIMs in place at the time of the survey. Of the remaining six, five had target dates for introducing EDIMs. Thirty-one LLSCs (74 per cent) were using EDIMs to address gender segregation, a higher proportion than rated gender segregation a priority issue. However, in many cases EDIMs related to attempts to improve the participation of young men generally in comparison with young women, but not in specific sectors and/or did not relate to work-based learning. Some examples of EDIMs are shown below:

Address gender/ethnicity/disability imbalances in work-based learning occupational areas [by measuring] percentage increase of representation of identified groups in each occupational sector each year.

Reduce the participation gap between males as opposed to females in engaging on structured council funded learning at the point of transition from Key Stage 4 (year 11, 16 year olds) [by aiming to increase] male entry to 90.0 per cent by November 2004.

Increase participation of female learners in the construction and engineering sectors and male trainees in the health care sector.

[Increase] participation of females in advanced modern apprenticeships in construction and engineering by 2 per cent per year and males in advanced modern apprenticeships in hair & beauty and Healthcare and Public services by 3 per cent per year.

LLSC survey responses

Twenty-eight LLSCs (67 per cent) reported that providers were, or would be, using the EDIMs, and the LLSCs would be using the EDIMs as part of their Provider Performance Reviews and provider three year development and action plans. One commented:

We noted that, in one of our providers, participation of females in engineering was low, so we set a target and the provider drew up an action plan. The provider then reviewed its marketing materials to ensure there were images of females in the roles, and targeted local girls schools.

THE CONTEXT FOR ACTION ON GENDER SEGREGATION

The same LLSC also reported that colleges and other providers were being given money through the Local Interventions and Development (LID) Fund to address equality and diversity issues.

The introduction of the EDIMs clearly has been an important step forward. However, at present the impact measures do not appear to carry the same weight as do the targets for overall rates for starts and completions.

Sector priorities

LLSCs were also asked in the survey if there were any priority sectors in their localities on which resources were being focused at present. The aim here was to assess the extent to which the investigation sectors were priorities (Table 3.5).

Table 3.5 Sectors identified as priorities by LLSCs

Sector Number Per cent

Health, social care and public administration 23 55

Construction 18 43

Engineering 16 38

Hospitality, travel and tourism 16 38

Manufacturing 11 26

Retail 10 24

Transport and distribution 7 17

Manufacturing food and drink 6 14

Financial and business services 6 14

Creative/cultural industries 4 10

ICT 3 7

SME management/leadership 3 7

Voluntary and community 3 7

Childcare 3 7

Call centres 2 5

Plumbing 2 5

Biosciences/bioengineering 2 5

Source: Survey of LLSCs, 2003.

[image:38.595.75.521.328.667.2]should be noted that plumbing is treated as a sub-section of construction by many LLSCs, and childcare may be classed as part of education or care (see Section 3.4 for details of the difficulties with the data). Thus it is possible that plumbing and childcare have not shown up as priority areas since they are included within these other sectors, which were flagged up as priority areas.

SSCs/NTOs

Several of the SSC representatives to whom we spoke have set their own targets (either within their business plans or in other documentation), for increasing the proportion of atypical trainees. Amongst the five SSCs interviewed as part of the research, three had independently set targets for addressing gender segregation either within apprenticeships or within the wider workforce: the CITB-ConstructionSkills had set targets for increasing the number of female CITB Managing Agency first year trainees within their business plan by 50 per cent; SEMTA was planning to raise participation by women by one percentage point a year; and SummitSkills had set a target to double the number of women in plumbing over the next three years as part of its licence bid. The EYNTO representative stated that the organisation would set targets for addressing gender segregation in the future, but was not able to pursue them actively yet, since it was in the transition phase between NTO and SSC.

For most of the SSCs, however, their main priority was to increase uptake and completion of MAs. The NLSC confirmed that the target against which the performance of SSCs would be assessed was a target rate of 24 per cent of people

entering MAs.7 For most of the sectoral representatives interviewed, recruitment to

the MAs (and to the sector more generally) was indeed a matter of some concern. One problem was the availability of MA places with employers; that is, the number of jobs available. A second problem concerned the provision of training places, both on-site or through college places.

Each sector had targets focused on promoting growth in the sector. For sectors such as engineering, such targets were set against a history of falling interest in this subject (and in science based subjects more generally) amongst young people, at HE level as well as at intermediate level. Such difficulties led to something of a ‘double bind’ situation. The sector organisations could see that increasing the pool of recruits was going to be necessary if they were to meet skill needs, but this goal also to some extent constrained their ability to focus on targets seen as desirable but less pressing. The pressure to meet recruitment targets needed to be prioritised over other targets:

THE CONTEXT FOR ACTION ON GENDER SEGREGATION

The key issue is motivating young people to apply, to get interested … Currently, there are 7,200 starts on AMAs. The target is to reach 10,000, so we have got to increase recruitment to reach this by 2005 (as set out in the sector workforce development plan). We have not seen the women and ethnic minority ratios improve over the last two to three years. We are putting the SSC resources into meeting the skills requirements of the sector. Doing that is the key priority, irrespective of how we meet that target.

SEMTA

The target is to increase numbers [coming through the MA route] by 29 per cent next year. The target is to get 40,000 over the next three years, although there is no set target for women, they are considered important for future skill needs.

e-skills UK

3.7 Conflict and pressure in priorities

The survey revealed that LLSCs have many competing priorities. Eight LLSCs stated that they were not at present taking any actions directly to confront gender segregation in the five identified sectors. However, one of these was clearly intending to do so in the future and others were taking indirect action to combat segregation; for example, one LLSC had invested significantly in equality and diversity training and auditing.

The LLSCs that were not currently tackling gender segregation in the investigation sectors stated that this was because:

• There was a lack of time, resources and specialist staff/specialist knowledge.

• Other priorities had been more urgent (e.g. supporting learners with complex

needs and learning difficulties; supporting providers in complying with equality legislation).

• Emphasis had been placed on improving achievement rates across the board in

MAs and also improving learner numbers.

• There was a lack of appropriate data.

Funding incentives