UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN QUEENSLAND

Dialogic inquiry: From theory to practice

A Dissertation submitted by

Jennie Swann, BA, MEd, Cert Online Ed

For the award of

Doctor of Philosophy

ABSTRACT

This study used theories of social learning, dialogue and inquiry to develop an

interactive website to support dialogic inquiry online. The literature on online

learning often takes a technological rather than a pedagogic perspective which

appears to assume that today’s university

studentsknow how to learn through

inquiry using social media online. Yet there is a great deal of evidence that this is

not the case. An examination of the literature of adult learning and primary

school pedagogy in terms of their relevance for social learning online, together

with an exploration of notions of dialogue and community, led to the

CERTIFICATION

OF

DISSERTATION

I certify that the ideas, experimental work, results, analyses, software and

conclusions reported in this dissertation are entirely my own effort, except where

otherwise acknowledged. I also certify that the work is original and has not been

previously submitted for any other award.

Signature of candidate

Date

ENDORSEMENT

Signature of Primary Supervisor

Date

In memory of

Matthew Lipman

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I should like to thank the many people who made this thesis possible. I owe my sincere gratitude to my supervisors, Dr Peter Albion and Dr Shirley Reushle. Being a distance student has meant that I could meet them in person only rarely, yet both in their different ways have given me immeasurable support throughout my research and writing. Peter has extended my thinking in many directions while at the same time helping me to stay on, or at least near, the path of my thesis journey. Shirley’s warmth and expertise in facilitating online dialogue has helped me connect the theory to the practice which is essential in design research.

I am also deeply grateful to Lorraine Parker and Stanley Frielick, my managers, for allowing me the research time to work on my PhD while still being employed full-time and also to AUT University for awarding me a Vice-Chancellor’s Scholarship for one semester in 2011. I would certainly never have been able to complete the work without that period of sustained and continuous effort.

I should also like to thank the staff and students who took the time to participate in my research. Dr Catherine Kell and the students in her adult literacy and numeracy paper, Susan Kohut and her students of the theory of Western acupuncture, and Mieke Couling and her large class studying emergency management. I would also like to thank Helen Cartner, Lynn Grant, Kevin Roach and Lynette Reid, who also participated in the study. The online dialogues they facilitated and their reflections on those dialogues were insightful, even though too few of their students returned ethics consent forms for me to be able to use their data.

I also owe a debt of gratitude to Dr Jens Hansen, who asked the awkward questions and who introduced me to some of the other people who were on journeys like mine. The shared lunches at Woodhill Park were always filled with new perceptions and

compassionate understanding. Dr Chris Jenkin, Jo Perry, and many more, thank you! Thank you too to Marica Ševelj, who began my PhD journey by spotting a flaw in my first version of a facilitation model; to Julia Hallas for the endless conversations we have had about pedagogy, knowledge, thinking and learning. I have learned so much from you. I would also like to thank Ailsa Haxell for introducing me to the international online community of PhD students and Yvonne Wood for introducing me to Scrivener. I wish I had found both earlier.

And thank you to Dr Ann Kerwin, Philosopher in Residence at AUT University, whose seminar series “Invite the Unexpected” gave me the confidence to think that I might be able to do a PhD at all. Thank you too Ann for the cards and notes of encouragement, and faith that I could complete it.

Finally I would like to thank my family for their support and tolerance of “the elephant in the room” for so many years. My sister Sarah Brock helped me to understand my own writing process through analogy with her practice as an artist and my other sister

NOTATION

Māori words: Pākeha = White or European people; whanau = family

Electronic books: Where reference has been made to ebooks which are not paginated, a location number has been provided in the citation itself, and the total number of locations in the full reference. Together these should provide sufficient information for a quotation to be found in a paper edition of the same book.

Online sources: Where reference has been made to online sources not available in print form, such as blogs and wikis, a paragraph number has been provided rather than a page number.

Personal pronouns:

Use of personal pronouns: since both I and all of the tutors who participated in this research are female, I have used the pronoun “she” in many cases rather than attempting to use the more unwieldy gender-nonspecific terms. “She” should of course be taken to include “he,” and so on.

Identification of discussion forum posts

A full record of all the posts in all the discussion forums studied is provided in Appendix A. Each post is numbered and quotes from these posts are identified by number of iteration, number or letter identifier of forum, and post number. Thus in Iteration 1, where three threads of Discussion Forum 10 were analysed, the identifier 1.1.1 refers to the first iteration, first thread, first post; where students were assigned to groups, the identifier 2.A1.1 refers to the second iteration, Group A1, first post; and the identifier 3.A.1 refers to the third iteration, Group A, first post.

Quotations from discussion forums

In order to retain their authenticity, all quotes from discussion forum posts are reproduced verbatim, without correction or indication of error. They are likely to be more comprehensible to a reader without the repeated introduction of the term (sic).

Terms used: Pedagogy: Although the participants in this research study were university tutors and students, a great deal of relevant educational theory has been developed through work with children. Therefore the word “pedagogy” has been used in preference to the less-common term “andragogy.”

The West: This is perhaps the best-known means of referring to the developed world, and in this thesis to the Eurocentric views of thought and knowledge associated with that culture. This term has been used in this dissertation because of its common use, and its brevity outweighs its lack of accuracy. For us in the Antipodes, of course, these “Western” countries are in the North.

Tutor: Throughout the dissertationall participating lecturers have been referred to as tutors. This was a reflection of their role in the research study rather than a measure of their employment status. Abbreviations: The following abbreviations have been used. All have been

explained when they were first used.

ARGUNAUT A European Union funded project which used artificial

AUT University Auckland University of Technology (brand name)

CCS Classroom Community Scale (Rovai, 2002a) a questionnaire used by permission of its creator.

CoI Community of inquiry

DA Discourse Analysis

DR Design research

DF Discussion forum

IBL Inquiry based learning

LMS Learning Management System (Blackboard at AUT) MOOC Massive open online course

NZQA New Zealand Qualifications Authority

SNA Social network analysis

SNAPP Social Networks Adapting Pedagogical Practice software tool that allows visualisation of the network of interactions in discussion forums. First developed by a consortium of Australian and Canadian universities

(http://research.uow.edu.au/learningnetworks/seeing/snapp/index. html), an updated version is now available from

Contents

ABSTRACT ... i

CERTIFICATION OF DISSERTATION ... ii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ... iv

NOTATION ... v

List of figures ... xv

List of tables ... xvii

Foreword ... 1

Chapter One : Introduction ... 3

PART I: LITERATURE REVIEW Learners and learning in an internet

age ... 9

Chapter Two : Who are our learners? ... 11

2.1 The net generation? ... 11

2.2 Students and reading ... 15

2.3 The study of adult learners ... 16

2.4 Capacities of adult learners ... 18

Chapter Three : Theories of knowledge and ways of knowing ... 22

3.1 The nature of knowledge ... 22

3.2 Ways of knowing... 27

3.3 Networked learning and connectivism ... 30

3.4 Testimony ... 31

Chapter Four : Perspectives on learning theory ... 33

4.1 Definitions of learning ... 33

4.2 Behaviourist and cognitivist theories of learning ... 33

4.3 Constructivist theories of learning... 34

4.4 The relationship between individual and social learning ... 35

4.5 Sociocultural theories of learning ... 37

4.6 The individual learner in a social context ... 37

4.7 Collective learning ... 38

Chapter Five : Learning is inquiry ... 41

5.1 The nature of inquiry ... 41

5.2 Lipman’s community of inquiry ... 44

5.3 Wegerif’s community of inquiry... 46

5.4 The ARGUNAUT project ... 47

Chapter Six : Dialogic inquiry ... 49

6.1 Four genres of dialogue ... 49

6.2 Thinking and dialogue ... 50

6.3 Conversation and dialogue ... 50

6.4 Monologue and dialogue ... 51

6.5 Critical thinking in dialogic inquiry ... 52

6.6 Socratic dialogue ... 55

6.7 Mediation of critical thinking through dialogue ... 57

6.8 Creativity and creative thinking ... 59

6.8.1 What is creativity? ... 60

6.9 Bohm’s dialogue as a creative process ... 62

6.10 Mediating creative thinking through dialogue ... 63

6.10.1 Recognising creative thinking ... 63

6.10.2 Connecting the sparks ... 64

6.11 Mindful, or caring, thinking ... 64

6.11.1 The “dark side” of caring ... 65

6.12 Bakhtin’s dialogism and responsiveness to “the other” ... 67

6.13 Mediation of caring dialogue ... 69

6.14 Dialogue and the written form ... 70

PART II: Methodology and methods ... 73

Chapter Seven : A design research approach ... 75

7.1 What is design research? ... 75

7.2 Criticism of design research ... 77

7.3 Design research for a PhD ... 79

7.4 Rigour ... 82

7.5 Reflection ... 83

Chapter Eight : Methods of data analysis ... 89

8.1 Framework for testing the artefact ... 89

8.2 Discourse analysis ... 90

8.2.1 Critical reasoning ... 91

8.2.2 Dialogic reasoning ... 92

8.2.3 Dialogic engagement ... 92

8.2.4 Moderation ... 93

8.3 Social network analysis ... 94

8.4 Participant reflections ... 95

PART III: Analysis and discussion of data ... 97

Chapter Nine : Gathering and analysing the data ... 99

9.1 The research questions ... 99

9.2 The process ... 99

9.3 Data analysis... 101

9.4 Organisation of data analysis section ... 101

Chapter Ten : Perceptions of dialogic inquiry online ... 104

Chapter Eleven : Iteration 1 ... 107

11.1 Intended artefact 1 ... 107

11.2 The context ... 108

11.3 Implemented artefact 1 ... 109

11.4 Dialogic inquiry 1 ... 110

11.5 Discourse analysis 1 ... 111

11.5.1 Critical reasoning ... 112

11.5.2 Dialogic reasoning ... 113

11.5.3 Dialogic engagement ... 114

11.5.4 Moderation ... 114

11.6 Social network analysis 1 ... 114

11.7 Participant reflections 1 ... 119

11.7.1 Students ... 119

11.7.2 Tutor ... 120

11.8.1 Changes to the model ... 122

11.8.2 Changes to the artefact ... 123

11.9 Reflection 1 ... 124

11.9.1 Point reflection ... 124

11.9.2 Line reflection ... 125

11.9.3 Triangle reflection ... 126

11.9.4 Circle reflection ... 126

11.10 Conclusion 1 ... 127

Chapter Twelve : Iteration 2 ... 129

12.1 Intended artefact 2 ... 129

12.2 Context 2 ... 129

12.3 Implemented artefact 2 ... 130

12.3.1 The critical dialogue dimension ... 130

12.4 Dialogic inquiry 2 ... 131

12.5 Discourse analysis 2 ... 131

12.5.1 Critical dialogue ... 133

12.5.2 Dialogic reasoning ... 135

12.5.3 Dialogic engagement ... 136

12.5.4 Moderation ... 138

12.5.5 Willingness to challenge... 138

12.6 Social network analysis 2 ... 140

12.7 Participant reflections 2 ... 144

12.7.1 Student perspective ... 144

12.7.2 Tutor perceptions ... 144

12.8 Evaluation 2 ... 145

12.9 Reflection 2 ... 147

12.9.1 Point reflection ... 147

12.9.2 Line reflection ... 148

12.9.3 Triangle reflection ... 150

12.9.5 Circle reflection ... 153

12.10 Conclusion 2 ... 153

Chapter Thirteen : Iteration 3 ... 156

13.1 Intended artefact 3 ... 156

13.2 Context 3 ... 157

13.3 Implemented artefact 3 ... 157

13.4 Dialogic inquiry 3 ... 158

13.5 Discourse analysis 3 ... 158

13.5.1 Dialogic reasoning ... 159

13.5.2 Dialogic engagement ... 160

13.5.3 Moderation ... 161

13.6 Social network analysis 3 ... 162

13.6.1 Single leader ... 163

13.6.2 No clear leader ... 165

13.7 Participant reflections 3 ... 168

13.7.1 Student perceptions ... 168

13.7.2 Tutor perceptions ... 169

13.8 Evaluation 3 ... 169

13.9 Reflection 3 ... 171

13.9.1 Point reflection ... 171

13.9.2 Line reflection ... 171

13.9.3 Triangle reflection ... 172

13.9.4 Circle reflection ... 173

13.10 Conclusion 3 ... 173

Chapter Fourteen : Conclusion ... 176

14.1 Aim of the research ... 176

14.2 Summary of findings ... 177

14.2.1 Research question 1 ... 177

14.2.2 Research question 2 ... 178

14.3 Limitations/critique ... 181

14.3.1 Credibility ... 182

14.3.2 Transferability ... 183

14.3.3 Dependability ... 183

14.3.4 Confirmability ... 183

14.4 The future ... 184

References ... 187

APPENDICES ... 211

Appendix A: Discussion forum discourse analysis ... 213

169001_2009_01: Adult literacy—Contemporary perspectives ... 215

Week 10 Thread 1: Multimodality and interactivity ... 215

Week 10 Thread 2: Multimodality and interactivity ... 220

Week 10 Thread 3: An article on academic literacies ... 237

588723_2010_01: Theoretical concepts of Western acupuncture ... 247

Discussion Group A1 Bivins question ... 247

Discussion Group A2 Lui question ... 257

Discussion Group Z1 Park answer ... 269

Discussion Group Z2 Lui question ... 282

Discussion Group Z4 Park question ... 300

577213_2010_02: Emergency planning ... 313

Group A: Volunteers ... 313

Group B: Volunteers ... 322

Group C: Volunteers ... 335

Group D: Volunteers ... 346

Group E: Volunteers ... 362

Group G: Volunteers ... 373

Discourse analysis coding summaries and percentages ... 386

Discussion forum activities and readings ... 387

Iteration 2 ... 389

Iteration 3 ... 392

Appendix B: SNA tables from SNAPP 2 ... 393

Iteration 1 ... 395

Week 10 forum: Multimodality and interactivity ... 395

Iteration 2 ... 397

Group A1: Bivins question ... 397

Group A2: Lui question ... 397

Group Z1: Park answer ... 397

Group Z2: Lui question ... 398

Group Z4: Park question ... 398

Iteration 3 ... 398

Group A: Volunteers ... 398

Group B: Volunteers ... 399

Group C: Volunteers ... 399

Group D: Volunteers ... 400

Group E: Volunteers ... 400

Group G: Volunteers ... 401

Iterations 1-3 SNA measures ... 402

Iteration 1 ... 402

Iteration 2 ... 402

Iteration 3 ... 403

SNA MAPS ... 405

Iteration 1 ... 405

Iteration 2 ... 407

Iteration 3 ... 409

Appendix C: Participant perceptions ... 415

Survey data ... 417

169001 Adult literacy: Contemporary perspectives Sem 1, 2009 ... 417

Iteration 2 ... 421

588723 Theory of Western acupuncture Sem 1, 2010 ... 421

CCS total scores 2 ... 425

Iteration 3 ... 427

577213 Emergency planning Sem 2, 2010 ... 427

CCS total scores 3 ... 432

L

IST OF FIGURESFig. 2.1: The re-centring process (adapted from Tanner et al., 2009, p. 39) ... 13

Fig. 3.1: Bloom’s and Anderson and Krathwohl’s versions of educational

objectives in the cognitive domain ... 23

Fig. 3.2: The DIKW view of knowledge ... 24

Fig. 4.1: Constructivist metaphors for mind and world-models (Ernest, 1996, p.

344) ... 35

Fig. 4.2: Characteristics of groups and networks (adapted from Dron and

Anderson, 2007, p. 20) ... 39

Fig. 5.1: A framework for inquiry-based learning (Levy, Little, McKinney,

Nibbs, & Wood, 2010, used by permission) ... 42

Fig. 5.2: Lipman’s community of inquiry model (2003, p. 200, used by

permission) ... 45

Fig. 5.3: Three dimensions of dialogue (Wegerif, 2007, p. 153, used by

permission) ... 46

Fig. 5.4: Digalo2’s main screen (Krauß, 2008) ... 47

Fig. 6.1: Mental acts which can develop into thinking skills (adapted from

Lipman, 2003, pp. 151 and 166–171) ... 58

Fig. 6.2: Elaboration of factors in thinking (adapted from Lipman, 2003, p. 152)

... 59

Fig. 7.1: The compleat design cycle (Middleton et al., 2008, p. 32) ... 80

Fig. 7.2: Overview of the research process ... 87

Fig. 8.1: Framework for collecting and analysing the data ... 89

Fig.11.1: SNA map of Week 10 discussion forum ... 115

Fig. 11.2: SNA map of Week 10, Thread 1 ... 116

Fig. 11.3: SNA map of Week 10, Thread 2 ... 117

Fig. 11.4: SNA map of Week 10, Thread 3 ... 118

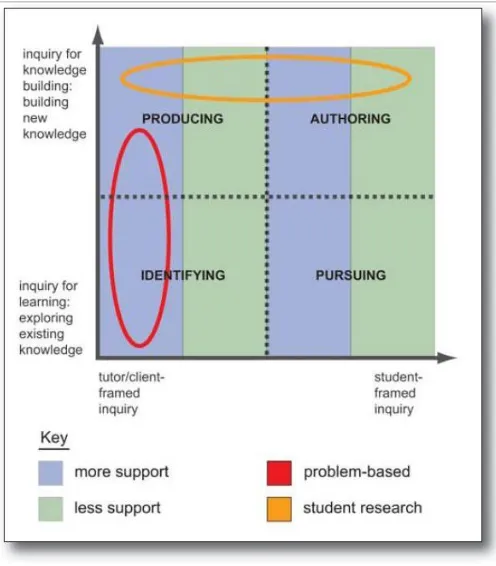

Fig. 11.5: Modes of IBL diagram (Levy et al., 2010, p. 9, used by permission)

... 122

Fig. 11.6: Dialogic inquiry model version 1 ... 123

Fig. 12.2: SNA map of Group A2 ... 142

Fig. 12.3: SNA map of Group Z4 ... 143

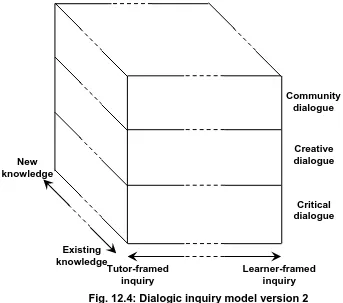

Fig. 12.4: Dialogic inquiry model version 2 ... 146

Fig. 13.1: SNA map of Group A ... 163

Fig. 13.2: SNA map of Group D ... 163

Fig. 13.3: SNA map of Group B ... 165

Fig. 13.4:SNA map of Group C Thread 1 ... 166

Fig. 13.5: SNA map of Group C Thread 2 ... 167

Fig. 13.6: SNA map of Group C Thread 3 ... 167

Fig. 13.7: SNA map of Group G ... 168

Fig. 13.8: Dialogic inquiry model version 3 ... 170

Fig. 13.9: Screenshot of critical talk macroscripts with “How to evaluate the

alternatives?” selected ... 175

Fig. 14.1: www.dialogicinquiry.net main page ... 179

Fig. 14.2: www.dialogicinquiry.net community talk macro-script titles ... 180

L

IST OF TABLESTable 4.1: Individual and collective processes and outcomes (de Laat, 2006, p.

18) ... 37

Table 6.1: Burbules’ genres of dialogue (1993, p. 112) ... 49

Table 7.1: Functions and strategies matrix (McKenney & Reeves, 2012, loc.

3395) ... 82

Table 7.2: Four strategies for structured reflection on educational design research

(McKenney & Reeves, 2012, loc. 3709) ... 85

Table 8.1: Relationship between research questions and data sources ... 95

Table 11.1: Coding of each of the threads in Discussion Forum 10 ... 112

Table 11.2: Degree and centrality of participants in Week 10 forum ... 116

Table 11.3: Degree and centrality of participants in Thread 1 ... 116

Table 11.4: Degree and centrality of participants in Thread 2 ... 117

Table 11.5: Degree and centrality of participants in Thread 3 ... 118

Table 12.1: Overview of discourse analysis coding results for Iteration 2 ... 132

Table 12.2: Examples of epistemic movement (adapted from Lipman, 2003, pp.

150 and 166-171) ... 133

Table 12.4: Degree and centrality of participants in Group A1 ... 141

Table 12.5: Degree and centrality of participants in Group A2 ... 142

Table 12.6: Degree and centrality of participants in Group Z4 ... 143

Table 12.7: Epistemological reflection model (Baxter Magolda, 1992, p. 30) . 152

Table 13.1: Overview of discourse analysis coding results for Iteration 3 ... 159

Table 13.2: Degree and centrality of participants in Group A ... 164

Table 13.3: Degree and centrality of participants in Group D ... 164

F

OREWORD

The first undergraduate lecture I ever attended was in economics, and the lecturer began by saying something like this:

Some of you will be successful in business regardless of what I can teach you. Some of you will never be successful in business, regardless of what I teach you. I’m here for the rest of you, the majority, because I can help you to be better in business than you would be otherwise.

Although it is situated in a different arena, the purpose of my PhD research study is very similar. Some people are naturally good at facilitating dialogue online. Their subtle interjections shift the argument slightly, open up new perspectives and encourage those on the fringes to enter the dialogic space. In my experience, the majority of tutors do not have this natural facility. It is something that they want to be good at, and are prepared to work at, and it is my job, as an academic adviser in a university centre for learning and teaching, to help them. But how? This is the question which I have sought to answer in this research study.

I have always been interested in language and communication. My first degree subject choice, economics, was the result of parental pressure: “You’ll only become an English teacher.” After a post-graduate teaching qualification and a couple of years teaching economics and statistics, I did become an English teacher and I found it fascinating. I spent 20 years teaching academic English in universities and polytechnics in Singapore, Hong Kong and Malaŵi and an MEd in applied linguistics and teaching English as a foreign language further increased my desire to learn more about how people of diverse cultures and backgrounds could come to understand each other through talking together and listening to each other with respect.

Working as a volunteer at Malaŵi College of Distance Education while my children were babies showed me the determination that some people can have to get an education even when it is very difficult for them. At that time Malaŵi had sufficient places for only 15% of those who were eligible to attend secondary school. For the other 85%, distance learning was the only option. Young people would queue for days in the hot sun to register to study African history and geography, agriculture, home economics, and also English literature, sciences and maths. Most of them became better-educated farmers, workers and parents and a few became the pride of their villages by entering, and graduating from, the University of Malaŵi. Graduation ceremonies were noisy, colourful and emotional as a single beat of the great drum gifted to the University by Mzee Jomo Kenyatta marked the achievement of each new graduate.

Education can be a strong force for development but it can also perpetuate the agendas of the dominant countries of the world. When I began my own distance learning, tutored by two of the fathers of distance education, John Bäath and Börje Holmberg, my interest was in exploring ways of making it more open and more reflective of the needs and aspirations of its learners, the citizens of tomorrow. On the one hand the students I taught brought their own cultures and ways of thinking with them to university, and on the other, they were there in order to obtain an education which would equip them to understand and work with people of the developed world. As a teacher of academic literacies I found myself again and again exploring these different perspectives on thinking and reasoning.

Over the past few decades, Western culture has shifted the goal of public discourse from understanding what is going on in the world to winning an argument, in a way which has been detrimental to education. There seems to be a gulf between the ideal

argument, yet public discourse in Western culture has taken on a combative metaphor— the war on drugs, the battle of the sexes—causing ritualised conflict, rather than genuine examination of opposing ideas (Tannen, 1998). An example of this in action occurred in an edition of New Zealand TV1’s Close Up on 6th October, 2011, when Perth-based professor of obstetric medicine Dr Barry Walters was questioned about his alleged assertion that women who opt to have children later in life were being selfish. Both in his original comments and during the interview Dr Walters made it clear that he was referring only to women over the age of 40 with existing age-related medical conditions which could cause a pregnancy to be fatal for both mother and child. Nevertheless, neither the presenters of the program nor the viewers whose opinions were reported at the end of the item appeared to deviate from their original assumption that he was referring to all women over the age of 35. This was not an argument. It was not even a dialogue, and still less an inquiry. It was a series of monologues in a competition which had to have a winner.

Against such a backdrop, it is perhaps hardly surprising that I have often found that my students resist engagement in dialogue online. Many students, of many different

Chapter One

: Introduction

@easegill (Nigel Roberts) Students never claimed to be digital natives and we should stop beating them up for not being expert online learners. Teach them! #icelf11 11:40 PM Nov 29th, 2011 from Twitter for iPad

The purpose of this research study was to find a way of helping people to explore their own and each other’s worlds through dialogic inquiry. Such help would be potentially useful for any group or network of people exploring any aspect of human thought or action through the medium of any digital application which allows human discourse. The focus of this study, however, was far less broad, concentrating on tutor facilitation of dialogic inquiry in post-graduate courses through discussion forums. Three claims have been made, which guided the study. The first is that true learning is essentially inquiry. From the three-year-old’s incessant, “Why?” to post-graduate research, learning is most effectively driven by genuine questions about authentic issues. A second claim is that Prensky was wrong. Roberts’ tweet at the beginning of this introduction succinctly expressed a widely-articulated challenge to Prensky’s digital native characterisation of young people and its implication that students have no need to learn how to learn online because they already know (Prensky, 2001a, 2001b). There are many books and papers which suggest that this is the case, almost all based on anecdotes of individuals or single classes who have achieved such self-directed learning (for examples see D. Thomas & Seely Brown, 2011, Ch. 1) but, as is argued in Chapter 2, there is little research evidence to support this. Technology does not of itself cause learning to occur, “Networks do not think; thinking occurs in dialogues” (Wegerif & de Laat, 2011, p. 318). A third

argument is that university tutors need help to facilitate learning through dialogic inquiry online. University education today is based on a mediaeval model, on an industrial scale, in a digital age and given that this is driven by a reward system which promotes research above teaching, it is no wonder that so many tutors are finding the adjustment to teaching online so difficult.

Thus, the goal of this research study was to develop an online means of support for university tutors which would help them to facilitate dialogic inquiry online. The main research question was:

How can tutors of postgraduate university programs be helped to facilitate dialogic inquiry online?

In order to answer this question an “artefact” was developed, initially in the form of professional development workshops plus associated documents, and the content and use of these was tested through three iterations in order to develop and refine both an underlying theoretical model and an artefact to a point where the latter could be made available in a freely-available online form. The three subordinate questions which guided this research were as follows.

Research Question 1: What do tutors and students in post-graduate programmes perceive as the main challenges of facilitating dialogic inquiry online? What do they find does/does not assist?

Research Question 2: What theoretical model could provide an effective foundation for the practical support of dialogic inquiry online?

Research Question 3: What features would an “artefact” need to have in order to

The context of the study was university learning in which tutors were primary facilitators, and post-graduate courses were selected as the focus of the research

because, of those accessible for study, it was these which were fully-online. In a blended course dialogue may occur in a classroom, corridor or cafe and attempts to capture this for analysis could have influenced the discourse itself, rendering it inauthentic.

A design research approach was taken so that the main outcome of the study could be an artefact which was ready for use by other tutors in other contexts. In educational design research, an artefact may be a computer application, or a curriculum design, or a professional development intervention, for example. In this research study, called the

Dialogic Inquiry project, the artefact was developed in the course of three iterations of testing into a support website containing 20 sets of open questions which could be embedded within a content course to facilitate the development of critical, creative or caring dialogue online. Research Question 1 informed an analysis of the perceived support needs of participating tutors and students which was compared with evidence of challenges and influencing factors derived from the research of others in the field. Research Questions 2 and 3 guided the three iterations of development of the theory, and refinement of the artefact.

All educational design research must be based on a theoretical foundation, and this study was underpinned by Lipman’s community of inquiry theory (2003) in the dialogic form expressed by Wegerif (2007). These theories are explored in depth in Chapter 5 and the reasons for choosing them have been published in an article in the Australasian Journal of Educational Technology.

Salmon (2000, 2002) provides perhaps the only model which is specifically designed to help tutors to facilitate discussions online and many have found it extremely effective as a starting-point. However, Stages 1 and 2, learning to use the technology and online socialisation, are both in practice revisited repeatedly throughout the life of an online discussion (Swann & Ševelj, 2005). The dialogue often stalls at Stage 3, information sharing or “cumulative dialogue”; the true collaboration of Stage 4 has proved more elusive (see for example Chai & Myint, 2006). From a tutor’s perspective, many of the issues of facilitating learning dialogue online are much the same even when different tools are used. A non-linear model may be more realistic.

Baker, Jensen and Kolb’s (2002) conversational model focuses on “a space where conversation can occur” (p. 64). They propose five dialectical dimensions of this space which need to be engaged simultaneously in order for learning to occur. These are:

the integration of concrete experience and abstract thought; the integration of reflection and action;

the spiral nature of these two;

the relationship between separate and connected knowing; and the balance between collaboration and leadership.

Kolb’s experiential learning cycle has been in regular use for over 20 years and it has proved an effective basis for some types of learning, e.g. skills-based workshops. However, there has been criticism of its theoretical underpinnings. Oxendine, Robinson and Willson (2004 para. 30) argue that “the concepts outlined by Kolb are too ill-defined and open to various interpretations and that the ideas he presents are an eclectic blend of ideas from various theorists that do not fit logically.” There are difficulties too with the notion of concrete experience, since it does not really include the social aspects of experience. Also in practice university students often “experience” something by reading about it; this is two levels of abstraction (speech and text) away from the concrete (Laurillard, 2002). Further, Kolb cites Dewey (1910/1991) in support of his reflection/action dimension of learning whereas in fact Dewey believed that we do not generally reflect on our experience unless it has produced a noticeable contradiction (Oxendine et al., 2004, para. 24).

Laurillard (1993, 2002) has proposed a conversational model of learning based on a phenomenographic approach on the grounds that this is more democratic. “Democratic” is used to mean “giving full representation to students’ as well as tutors’ conceptions … The learning process must be constituted as a dialogue between tutor and student” (1993, p. 94). Laurillard’s conversational model is criticised on the grounds that the community of practice concept of progression from novice to expert which it entails is extended too far (Wise & Quealy, 2006). While it is appropriate for fostering research communities it is less helpful as a model for

university teaching and learning. Wenger’s (1998) community of practice model is based on his work with large industrial firms and in this

environment communities grow, mature and die over a period of years. Membership of a community is voluntary and changes during the community’s life cycle as the original core moves on and peripheral members gain expertise and move towards the centre. In a modular university system a one-semester course does not allow sufficient time for such a community to form, let alone mature, and students are not generally given the option of not participating (Carusi, 2006; Wilson, Ludwig-Hardman, Thornam, & Dunlap, 2004).

A significant amount of research has been done on the various aspects and implications of this model for online learning. There has been research on teaching presence, particularly teacher immediacy in design and setup (e.g. Melrose & Bergeron, 2007), and also on ways of supporting social

presence (Tu, 2002; Weaver & Albion, 2005). Research has been done on social identity (Merchant, 2006), teamwork (B. G. Davis, 2002; Meeuwsen & Pederson, 2006), collaboration and co-operation (Allen & Lawless, 2003; Cameron & Anderson, 2005), participation (Chai & Myint, 2006; Williams, 2003), and peripheral participation (Hung, Chen, & Koh, 2006). In the area of cognitive presence, there has been work on reflection (Stefani, 2004), schemata (Grossera & Lombard, 2008), cognitive load (Hron & Friedrich, 2003), also on teaching thinking skills (Duron, Limbach, & Waugh, 2006; MacKnight, 2000). A review of 252 reports from 2000-2008 which referenced Garrison, Anderson and Archer’s community of inquiry framework (Rourke & Kanuka, 2009) indicated “that it is unlikely that deep and meaningful learning arises in CoI” (p. 19). There was a rapid response to this from Garrison and others (Aykol et al., 2009), however it is interesting to note that this fundamental criticism came from two members of the group who originated this model. Another point of interest is that, while the focus of the Garrison, Anderson and Archer model is the people having the dialogue, that of Lipman’s model is the dialogue of itself. (Swann, 2010, pp. 51–53)

Lipman’s community of inquiry model has been repeatedly shown to be effective with children of a range of ages (Wegerif, 2010, p. 14) and Wegerif’s dialogic form of the model has been used in schools (Wegerif, 2007, 2010). The model was extended for use in adult education by Lipman himself (Burgh, Field, & Freakley, 2006; Lipman & Sharp, 1978). It has been used with adults in the field of public administration, reinforcing its roots in Dewey’s notions of democracy (Shields, 2003), and it was fundamental to the ARGUNAUT project, a large European Commission funded project which applied the model to dialogue using two synchronous online applications, called Interloc and Digalo, in seven universities and schools in the UK, Germany and Israel (Asterhan, Wichmann, Mansour, Wegerif, Hever, et al., 2008; Asterhan, Hever,

Schwarz, Mishenkina, Gil, et al., 2008; de Laat & Wegerif, 2008; Nicolopoulos, 2009). So it was Wegerif’s version of the community of inquiry model which formed the basis of the artefact developed in this design research study. Each of the three iterations focused on one of the three dimensions of the model, caring, critical and creative dialogue, and the dialogic data was obtained from discussion forums. It may be argued that discussion forums have nowadays been superseded by more modern forms of online social interaction: Indeed, one of the reviewers of the paper quoted above referred to the analysis of discussion forums as “a hoary old chestnut.” However, the technology of a discussion forum allows a dialogue to be captured and analysed without the technical and methodological difficulties associated with selecting participant blogs or Facebook interactions, for example. A discussion forum is designed primarily for dialogue and so was an appropriate test environment for the purposes of this research. However, no such constraints apply to the use of the artefact in the practice of learning and teaching: It could be used in any online environment, or indeed face-to-face.

The framework for analysing the data was similar to the triangular approach taken by de Laat (2006, p. 108), and involved discourse analysis of online dialogue, social network analysis of forum participation and participant feedback though interviews and surveys (see Fig. 8.1 on p.89). The coding categories for the discourse analysis were adapted from those used in the ARGUNAUT project (de Laat & Wegerif, 2008; Wegerif et al., 2009). Each iteration of the research was evaluated for feasibility and soundness, of the underlying model, the artefact, and the research process itself, using guide questions suggested by McKenney and Reeves (2012) and the same authors’ process of structured reflection was applied to draw out from the findings insights which could inform the development of both model and artefact for the next iteration.

Educational design research projects can be large and complex, involving teams of researchers over an extended period of time and it may be thought that a single researcher’s PhD study would be too small for anything substantial to be achievable. However, design research projects develop and test artefacts through a number of different cycles, characterised by Nieveen (cited in McKenney & Reeves, 2012, loc. 3387) as developer screening, expert appraisal, pilot and tryout. This study may be seen as the developer screening stage, with thesis supervision and examination providing expert appraisal. This is thus a work in progress, which will continue beyond the PhD study.

The rest of this dissertation is structured as follows. Part I of the dissertation is the literature review which sets dialogic inquiry in a socio-cultural context in which university students learn together through the media of online digital applications. The selection of literature for review was based on a design research approach to theory described by diSessa and Cobb (2004) which suggested that three levels of theory should be addressed, which they called, “grand theories,” “orienting frameworks,” and “frameworks for action.” The grand theory underpinning the Dialogic Inquiry study was Vygotsky’s theory of human development (1930, 1934), the orienting framework was sociocultural theory (much of which is documented in the journal Culture & Psychology in the years 2002—2009), and the framework for action was community of inquiry theory (Lipman, 2003; Wegerif, 2007). In order to relate these theories to the research questions, the literature review was organised as follows.

Chapter Two: Who are our learners? and Chapter Three: Theories of knowledge and ways of knowing address Research Question 1 from the perspective of existing research and theory. This research question, essentially a needs analysis, was: “What do tutors and students in post-graduate programmes perceive as the main challenges of facilitating dialogic inquiry online? What do they find does/does not assist?” An account of the perceptions on this question of participant tutors and students is given in Chapter Ten. Chapter Four: Perspectives on learning theory, situates online learning in within current and historical theories of learning and argues for a socio-cultural approach. Chapters Five and Six: Learning is inquiry, and Dialogic inquiry explore community of inquiry and dialogic theory in depth to address Research Question 2: “What theoretical model could provide an effective foundation for the practical support of dialogic inquiry online?”

Part II of the dissertation justifies the use of an educational design research methodology for this study and explains how it has been applied in Chapter Seven: A design research approach, and Chapter Eight: A framework for data analysis. Part III presents an

context and focus of each one, the artefact as intended and as it was applied in practice, together with discourse and social network analysis of the discussion forum data and feedback on the intervention from tutors and students. Each of these three chapters ends with an evaluation of the underpinning theory and of the research process in terms of their relevance and effectiveness, together with a mainly structured reflection which focussed on the development and refinement of the artefact itself. Chapter Fourteen, the conclusion, summarises the contribution made by this study as it revisits the three research questions, critiques the trustworthiness of the study through an examination of its credibility, transferability, dependability and confirmability (McKenney & Reeves, 2012, loc. 4780) and looks to the future of this ongoing educational design research study.

PART

I:

LITERATURE

REVIEW

Chapter Two: Who are our learners?

Chapters 4, 5, and 6 of this literature review present the arguments for a dialogic community of inquiry as a theory on which to base the artefact developed in this

research study. Before this, however, Research Question 1 asked how the participants in the study saw dialogic learning online and, in addition to the data collected and

discussed in Chapter 10, this question has been addressed from a variety of perspectives in the research literature. These are explored in this chapter and the next. As will be shown, there is a great deal of literature in the field of online learning which makes assumptions about the characteristics and abilities of today’s learners (famously, Prensky, 2001a, 2001b). Although Prensky’s assumptions have more recently been discredited (Jones, 2011) their influence on modern theories of learning in a digital age has been strong (see, for example, Siemens, 2004). Yet, as shown in Section 3.3, these beliefs have been shown to cause disengagement among our students. In order to examine thes beliefs and their effects on current notions of online learning, this chapter compares the literature on online learners with earlier studies of adult learning and development.

2.1

The net generation?

Prensky famously characterised those born during or after the general introduction of digital technology as “digital natives” (Prensky, 2001a, 2001b, 2011). This has been echoed by others, who have referred to these students as “the net generation” (Oblinger & Oblinger, 2005) and as “millennials” (Howe & Strauss, 1991, 2000). Given the uneven and in some places rapid development of this technology in different parts of the world, exact dates vary, but generally these terms are used to refer to those born since 1980. The term “Generation Y” is also used, (e.g. by Weiler, 2005) although more in the fields of advertising and marketing than in education, and it refers to those born between 1980 and 1994. There has been a more recent modification of the native/immigrant dichotomy to one involving residents and visitors (D. White, 2008). However, this is related to technology use, rather than learning.

There has been a prevailing argument—perhaps better described as an Internet meme— that members of this cohort are highly skilled in using technology, have a different approach to learning from their predecessors and even that their thinking processes are markedly different from that of their predecessors (Downes, 2006; Oblinger & Oblinger, 2005; Prensky, 2001b; Siemens, 2006; Tapscott & Williams, 2010; D. Thomas & Seely Brown, 2011). It is argued here that while the students at Auckland University of Technology, and perhaps in other universities, may in the long run prefer to learn in a different way, many of them have been so heavily influenced by their previous

educational experience (see for example E. J. White, 2009) that they need support, and even persuasion, to change both their ways of thinking and their ways of learning. Indeed, while many of the students who participated in this research project were highly competent in the use of some digital technologies, these competences were

predominantly in the area of personal use rather than for learning.

effectively removing their raison d’être. Both Jones and Bates argue that Tapscott and Williams, like many others, oversimplify their characterisation of current university teaching, criticising it as all transmission-based while at the same time, for example, perpetuating that tradition by advocating the use of podcasts, and using the generational argument to separate many lecturers from their students by a notional chasm which is too deep for them to cross. Both Jones and Bates contend that changing the way we teach and learn is not a technological imperative; it remains a matter of choice. There are factors other than age which affect the uptake of new technologies; for example, the point in time when the technology was introduced, gender, local infrastructure,

ethnicity, and culture (Jones, 2011). In fact, evidence of great diversity in students of this generation has been found in South Africa, Australia and the UK (Czerniewicz, Williams, & Brown, 2009; Kennedy, Judd, Churchward, Gray, & Krause, 2008; Margaryan, Littlejohn, & Vojt, 2011 respectively) and the variables affecting this generation are far more complex than issues of access or age. Jones argues that although characteristics of these new technologies “afford certain types of social engagement” which need further exploration, the idea that new technologies have changed a whole age cohort’s view of the world should be abandoned (Jones, 2011, p. 42).

Fig. 2.1: The re-centring process (adapted from Tanner et al., 2009, p. 39)

Within Australasia, the most recently available Australian statistics show that 64.9% of all students in tertiary education in 2010 in Australia were aged 19-29 and 13.4% were aged 30-39 (Australian Department of Education, Employment and Workplace

Relations, 2011). New Zealand statistics are less detailed: In 2010, 43.4% of all students in tertiary education in New Zealand were aged 19-24 and 29.2% were aged 25-39 (NZ Ministry of Education, 2011). In other words, in both countries at this time the greatest

family-of-origin adol-

escent parent(s)

Stage 1: Launch position: Adolescent transitions from dependent status to emerging adulthood

Stage 2: Emerging adulthood: The emerging adult is peripherally tied to identities and roles of childhood/adolescence and, simultaneously, is committed to

temporary identities and roles of adulthood

family-of-origin emerging

adulthood

parent(s)

Stage 3: Young adulthood: The young adult leaves Stage 2 through more permanent identity and role commitments

family-of-origin young

adulthood

proportion of students in tertiary education was emerging adults and approximately three quarters of all of them were either emerging adults or young adults. The participants in this research project were graduate and post-graduate students and although their ages ranged from 21 to 50, the majority were aged between 25 and 40, emerging and young adults.

Research in this field provides a predominantly White and Western view, in which a high proportion of emerging adults enter tertiary education straight from school and have varying degrees of self-sufficiency in decision-making in a number of spheres— financial, personal, career, study and so on. Some will be working in jobs related to their study area, others will not. Some will be independent in terms of transport and others not. In the fields of love and work, there is considerable exploration of identity. Risky behaviour—sexual, drinking, and on the roads—peaks during emerging adulthood. Risk is the reverse of responsibility and this also includes responsibility for study. If a student has not had to work for an income, juggle time between job, study and family, she or he may be less ready to take responsibility for her or his own learning (Arnett, 2000). In other cultures people marry younger, and in some of these, as well as in others such as religious communities, the transition is often shorter and more structured. Tanner and her colleagues found slightly different time-frames and slightly different characteristics in their studies in China, and Argentina (Tanner et al., 2009) and although Arnett mentions a 1991 study of 186 traditional cultures in which this life stage was identified in only 20% of cases (2000, p. 477) he went on to argue that the progress of

globalisation and economic development is likely to increase this proportion. The cohorts studied in this research study included international students, mainly from China and Korea, who were generally unmarried and away from home for the first time. There was also a small number of Indian and Fiji Indian students, who tended to be more mature in terms of their family responsibilities. Both these groups were committed to studying for a higher qualification, although their perceptions differed about what this entailed. These perceptions are explored in greater detail in Chapter 3. The cohorts also included a number of Māori and New Zealand born Pacific Island students who were generally a little older (young adults) and had strong whānau (family and community) commitments. The Pākeha (White) students were the most diverse: They included 21-year-olds living at home, students in their twenties living in shared flats or with a partner and perhaps children, as well as older students with children who were in school or had left home. Many of these older students brought with them a great deal of life and work experience, rather than educational experience. While it cannot be claimed that the findings of this study are widely generalisable, the expansion of universities into

international markets, together with the increasing availability of university education to minority groups may indicate that the participants in this research study were reasonably representative of the diversity of today’s students.

2.2

Students and reading

Until recently, almost all online “dialogue” was in written form and much of it still is. Examples include blog and wiki posts and comments and text chat. Oral and written dialogue are different in many respects (see Section 6.14), one of which is that the interlocutors are reading each other’s dialogue rather than listening to it and another aspect of the digital native meme is the argument that today’s users of the Internet have lost, or not developed, the ability to read a text deeply and critically. Carr (2010a, 2010b) has claimed that our students are so deluged with information that they skip and skim online documents rather than reading them in any depth and that this carries over into their reading of paper-based texts as well. There is no doubt that people read differently online. The act of scrolling text past stationary eyes, rather than using peripheral vision to scan a complex page must cause differences in the way we decide what to read, and it is known that reading an online text which contains hypertext links is more taxing for the brain than reading text in a book or journal (Cull, 2011). The intuitive appeal of the argument that new technology is making today’s students superficial is evidenced by the extremely long history of this concern (Ong, 1982) and perhaps this is an indication that today’s tertiary students, though considerably more numerous and more diverse in many ways, are not really any less willing or able to study than those of earlier centuries.

Reading, for leisure or for study or work, has for quite a long time been the pastime of a relatively small, privileged elite (Griswold, 2008) and the spread of tertiary education to many whose parents did not have the opportunity to enjoy it may mean that many of today’s students are not members of that elite and have no family history of reading either for pleasure or for study. Further, the fact that young people spend so much of their time online does not necessarily mean that they develop the cognitive and information literacy skills required for deep reading, such as effective searching and evaluation of search results in terms of their value for intended purpose. There is evidence (see Cull, 2011, p. 8) that students who use a “good enough” strategy in their Internet searching for assignment work tend to get low marks, and yet this is not a characteristic of the entire tertiary student body. Evidence from the same source that university teaching staff also use skim-reading techniques while searching for online material may indicate that this is an essential information literacy skill, especially since this type of “horizontal” rather than “vertical” reading also occurs in the reading of paper-based text.

Experts seldom read a scholarly article or book from beginning to end, but rather in parts, and certainly out of order, actively using hands and fingers in flicking back and forth, underlining and annotating, often connecting their reading to their writing, and usually spreading pieces of paper around their desk (Hillesund, 2010, quoted in Cull, 2011, p. 9).

today’s students being markedly less able than their predecessors in terms of attention span and deep reading are not particularly new.

To summarise, the students who participated in this research project were mainly emerging or young adults, who from the theory were expected to be developing in terms of taking responsibility for their own learning, to have some experience of working in their chosen fields, to have some family and community commitments which might impact their commitment to their study and to have increasingly clear ideas about what they want to learn and why. This last is an essential part of the adult development process and one which has received more attention in the literature of adult learning than in the texts on online learning.

2.3

The study of adult learners

The field of adult learning has sometimes been called “andragogy.” This term derives from the more commonly used word “pedagogy” (from the Ancient Greek: paidos

meaning “child,” anēr with the stem andra meaning “man, not boy” or adult, and ágō

meaning “to lead”—girls and women were not educated in Ancient Greece). The word “andragogy” was first used in English by Edouard Lindeman, in a paper called

Education through Experience which he wrote with Martha Anderson in 1927. Lindeman was a friend and colleague of Dewey and his view of education was very similar to Dewey’s (1910, 1916/2008, 1938) in that he advocated authentic, co-operative learning through experience. However, perhaps the best known theorist of andragogy was Malcolm Knowles. Knowles met Lindeman in 1935 while he was working for the American National Youth Administration in Massachusetts and became very excited by Lindeman’s concept of andragogy. Both Lindeman and Knowles worked with youth in informal learning situations in the early part of the twentieth century and perhaps, given the longer lives and later marriage of today, the young adults they wrote of were in many ways quite similar to our emerging adults.

Knowles made a number of assumptions about the characteristics of adult learners. These were that as young people grow up they move from dependence on their families to self-directedness, a notion partly supported by Tanner’s model (Fig. 2.1 above); that over time adults develop an increasing amount of experience which forms both a resource and a driver for new learning; and that as people grow up, their educational focus is increasingly on learning which can be practically applied to the current demands of their own lives. Later, Knowles added two more assumptions: Adult

learners focus on solving problems which are authentic in terms of their own lives rather than on learning content; and they need to know why they need to know something in order for them to learn it (Merriam et al., 2007, p. 84).

The overlap between these and the learner characteristics which derive from the digital native argument (Sheely, 2008, p. 914) indicates that it is not technology which drives them but the development of adulthood, which nowadays occurs in a digital

environment. Although in earlier theory learning appears to have been seen as an individual rather than a social process, the first of Knowles’ adult learner

characteristics–the move from dependence to self-directedness—echoes Tanner’s re-centring process shown in Fig. 2.1. Of the others, self-directed learning has received the most attention in the literature of adult learning (Brookfield, 2009; Knowles, 1975; D. Thompson, 2009) and this is of interest in light of the current arguments that students can and should direct their own learning online (Downes, 2006; Siemens, 2004 among many others). Knowles described self-directed learning as a process “in which

maturity (1970, 1980), investigations of self-directedness, in terms of its goals, as a process and as a personal attribute of the learner (Brookfield, 2009; Merriam et al., 2007) have shown it to be difficult to learn and to teach. Further, a learner’s ability to be self-directed at the outset may be inhibited by a number of factors, of which perhaps the most important is known as Plato’s paradox and is expressed in the Meno as follows.

But how will you look for something when you don’t in the least know what it is? How on earth are you going to set up something you don’t know as the object of your search? To put it another way, even if you come right up against it, how will you know that what you have found is the thing that you didn’t know? (Plato, 1961, 80.d).

In other words learners need to know something about a field in order to be able to decide what else in it they need to know and there is evidence from the study of massive open online courses (MOOCs, discussed in Section 3.3) that this is not necessarily the case among emerging adult or young adult students. Students also need to have some technical and information literacy skills in order to be able to manage their own learning and in addition to skills in using digital applications, these include psychological tools such as those theorised by Vygotsky (1930/1978); and they also need to have confidence in their own competence as learners plus a strong commitment to learning at that point in time (Merriam et al., 2007). Brookfield, who has devoted a considerable number of years to researching this field, has recently argued that there is a political dimension to self-directedness as a goal of adult learning, since it directly contradicts any notions of core or national curriculum. It appears that there are in practice many aspects of formal learning which actually prevent true self-directedness. “Self-direction is an inauthentic confidence trick if it involves people making key decisions about their learning all the while being unaware that this is happening within a framework that excludes certain ideas or activities as subversive, unpatriotic, or immoral” (Brookfield, 2011, p. 39). These arguments raise a number of questions about the application of this principle to undergraduate or course-based post-graduate learning, for example. As Brookfield says, there would need to be an entirely different approach to curriculum design and learning outcomes in order for this to be feasible, but such a new approach is something which appears to be developing in the online sector, for example in the Open Education movement.

Another of Knowles’ assumptions was related to adults’ experiences of life and learning and this is a major difference between children and adults as learners. With a few traumatic exceptions, adults generally have more experience of life than children and inevitably, in any group of students, the older they are the greater chance there is for diversity of thought and experience, and perspective. However, in the 1990s there was a great deal of psychological research which found that although this was the case, there were wide variations in this not only between adults and children but also between one adult and another. For adults, their experience can be a resource for learning and also learning often involves making sense of this experience (Merriam et al., 2007) which in turn can be a powerful motivator for the pursuit of learning. Whereas much of children’s learning is of new knowledge and skills, as adolescents move into adulthood there is a comparison and perhaps re-integration of what is known, and meanings and values may change either in rebellion against the previous generation or because cultural changes cause them to become inappropriate (Arnett, 2000). Yet for adults, more than for children or adolescents, experience can also be a barrier to new learning, perhaps because there is more of it to get in the way.

by choice, and of sense of purpose in study. Such students may be expected to be more aware of their own goals and by this time learning is not only “learning to do” or “learning to think” but also “learning to be” (Haythornthwaite, 2008).

However, the emerging adults of today may not have as much choice in their own education as older students do. The growing phenomenon of “helicopter parents” (i.e. those who “hover” protectively over their offspring throughout their education) indicates that in practice, at least at the start of her or his tertiary study, a student’s choice of what, where, or even whether to study may be heavily influenced by parents or other family members (Coburn, 2006; Lipka, 2007; Lum, 2006). In addition, the main motivation to study may derive from a worldview in which qualifications which relate closely to the current employment market are imperative, or from economic circumstances in which remaining employed, or employable, depends upon meeting increasing demands for tertiary qualifications.

Three perspectives on learning may also shed light on the ways in which adults learn online, particularly in a dialogic community of inquiry (Wegerif, 2007) of the sort which lay at the heart of this research study. They do not map neatly onto each other but co-exist and overlap in complex ways. These relate to the capacities of adult learners, theories of knowledge, and ways of knowing and are explored in the rest of this chapter, and in the next.

2.4

Capacities of adult learners

The four capacities of adults that develop through learning suggested by Brookfield (2003) may be seen as goals of the dialogic community of inquiry which lay at the heart of this research study. The first was the capacity to think dialectically: This form of adult reasoning is an ability to deal with the complexities and inconsistencies of life. It is associated with the contextual knowing discussed in Section 3.2 below in that it is the intersection of universal rules and context. For example, an adult may be against killing on principle, yet support the idea of an abortion for a young schoolgirl who has been raped. This is not formal reasoning but “everyday cognition” (Rogoff & Lave, 1984) of the sort employed by parents on a daily basis as they seek to set and maintain discipline boundaries for their children.

In Piagetian terms, adult learners may be said to have moved beyond the child development stages into “post-formal” operations which involve finding a sense of balance in an inconsistent world. Brookfield followed Basseches (1984) in calling it “dialectical thinking” but the word “dialectic” carries with it the rationalist notion of two sides of an argument—argument and counter-argument, thesis and antithesis. It is argued in this thesis that in a dialogic view there can be more than two perspectives on an issue (Bakhtin, 1975, and see also Chapter 6). King and Kitchener (1994) called this “epistemic cognition”; Habermas called it “intersubjective understanding,” and Mezirow called it “perspective-taking” (Brookfield, 2011, p. 45), all terms which allow for a broader range of perspectives than the two sides of a purely logical dialectic argument in the tradition of Descartes. It is the contention of this thesis, explored in depth in Chapter 6, that this may be seen as a capacity to think dialogically and to develop this through a community of inquiry online.

The dominance of formal logic, which could be seen in the emphasis on maths and the classics as a prerequisite for university entry in the days before mass education, has given way more recently to informal logic, and the resulting theories of argumentation can be very complex. Argumentation theory is prescriptive rather than descriptive and logic is not generally taught in schools, nor in most programs at university. Adults in general, as opposed only to those in tertiary education, are more likely to engage in “embedded logic” (Labouvie-Vief, 1980) or “practical logic” (Sinnott, 1998/2010). At its simplest, an argument is “a set of sentences such that one of them has been said to be true and the other(s) have been offered as reasons for believing the truth of the first” (Talbot, 2010) and this can provide a manageable starting point for students who are focusing on the development of their ability to think critically in a tertiary education context.

This sort of higher order thinking has been described, (e.g. by Resnick, 1987, p. 45) as “the hallmark of successful learning” but, like dialogic thinking and practical reasoning, it is much easier to recognise than to define. A similarly troublesome term is deep learning (Kember, 2000; Kember & Gow, 1991). Although a great deal of the theory of the development of learning and thinking relates to work done with children, it appears that the differences between adult and child learning emanate from a synergistic relationship among three factors, the learner, the context and the process of learning, with the last being the least different (Merriam et al., 2007, p. 423). Thus, it is argued here that there is much to be learned from research into the learning and teaching of children which is directly relevant to adult learning in an online environment. Indeed, theorists such as Vygotsky and Piaget, both of whom worked mainly with children in classrooms, are frequently referred to in the literature of online learning.

Vygotsky argued that mental functions such as memory, attention, perception and thinking appeared first in “elementary form” before being transformed into a higher form. For example a pre-literate person may remember things in terms of practical experiences but as mental functioning develops these memories become mediated by such things as counting systems, writing and so on (Vygotsky, 1930/1978). In a series of experiments with more than 300 children, adolescents and adults, Vygotsky asked participants to sort figures which differed in colour, form, height and size. When a figure was turned over, a nonsense word was revealed and the participant was asked to predict which of the other shapes would have the same word attached to it. When the patterns of selection were analysed an ontogenetic shift was observed from

“unorganised heaps” to “complexes” to “concepts” (Wertsch, 1985, pp. 99–102). Although more recent research has indicated a range of possible developmental paths, it appears that advanced mental functioning is characterised by “a linguistically created reality” (Wertsch, 1985, p. 35) for example for categorisation, the evaluation of premises and for the derivation of conclusions. So in this research study it was hypothesised that discourse analysis evidence of markers for the making of claims, questioning and reasoning would provide evidence of higher mental functioning or deep learning. A full description of the discourse analysis codes used is presented in Chapter 8.

functioning. This does not mean that context is unimportant, more that higher order thinking involves a separation of the notions of theory and context such that a principle may be modified differently in different contexts.

In the journey from complexes to concepts, Vygotsky argued that milestones were discernible (Kozulin, 1990, p. 161). As thinking in complexes may be a precursor of generalisation, “potential concepts” may be precursors of abstraction. Beginning to distinguish between essential and nonessential attributes in a process of classification, for example, may be evidence of the formation of a potential concept. Both

generalisation and abstraction are required for conceptual thinking. A more advanced form of complex reasoning is a “pseudoconcept” which Wertsch described as “the transitional construct between complexes and concepts” (Wertsch, 1985, p. 104). Not yet sufficiently developed to be a concept because it is still structured more like a complex, a pseudoconcept functions like a concept. However, such a concept may simply be incorrect (Mercer & Littleton, 2007) and feedback from a teacher or more knowledgeable fellow-student is an essential step in the development of self-regulation as a learner. “The awareness of one’s own cognitive operations comes only after the

practice of phenotypically similar operations, and their ‘endorsement’ by others” (Kozulin, 1990, p. 162, his emphasis). As an example of this, an approach to teaching this which has had some success involved asking students to innovate explanations, rather than to discover them, by working through a series of explanatory exercises (Schwartz, Chang, & Martin, 2008).

Vygotsky’s four major criteria for distinguishing between elementary and higher mental functioning were as follows:

1. a shift of control from the environment to the individual. In other words the learner begins to take control of their own learning, for example through student-initiated rather than tutor-initiated inquiry;

2. an emergence of metacognition;

3. a shift from individual to social learning, since higher mental functioning is social in origin and in nature, in terms of both the process o