Demographie aspects of abortion

in Eastern Europe:

a study with special reference

to the Czech Republic and Slovakia

by

Libor Stloukal

A thesis submitted for the degree of

Doctor of Philosophy

at The Australian National University

Declaration

Except where otherwise indicated this thesis is my own work carried out during my PhD scholarship in the Demography Program, Division of Demography and Sociology, Research School of Social Sciences, at The Australian National University from June 1992 to June 1995.

June 1995

[a 'Av v

Acknowledgments

Many people have contributed to the completion of this thesis. To all of them I owe my deepest gratitude, but I first wish to acknowledge the assistance and patience of those who were, for varying periods of time, members of my supervision panel. These include, in alphabetical order, Dr. Gordon A. Carmichael, Dr. Lincoln H. Day, Professor Geoffrey McNicoll, and Dr. Christabel Young. Each one made a unique contribution, and collectively they provided me with the benefit of their critical intelligence and encouraged me to be clear, consistent, and accurate in my thinking and writing. To Gordon, who was my supervisor from beginning to end, I owe special thanks for his perceptive remarks, careful and prompt reading of drafts, and insightful suggestions which helped clarify many issues.

I owe a sincere debt of gratitude to Dr. Lado T. Ruzicka, who not only had assisted me in my efforts to pursue doctoral studies in Australia, but also provided a permanent support during my stay in Canberra which proved truly invaluable. With his integrity and kindness, Lado buttressed me personally, and with his far-ranging knowledge and expertise in social science, he inspired me professionally.

Special thanks are due also to the following people who have read the manuscript for this thesis, in whole or in part, at one or another stage of completion, and offered their candid advice: Dr. Mariah Evans, Dr. Alan Gray, Ms. Yvonne E. Pittelkow, Dr. Mirka Prazak, Professor Harry Rigby, and Dr. Vladimir Srb. I greatly appreciate the painstaking work of Ms. Wendy H. Cosford who edited drafts of the thesis chapters. Wendy was extremely helpful in putting my Czech English into English English and also offered some highly appreciated moral support.

particularly grateful to Professor Zdenek Pavlik, for education, consistent support, intellectual stimulation, and an example in excellence.

I thank The Australian National University for the hospitality and postgraduate scholarship which have enabled me to produce this work. I am grateful to all the staff in the Demography Program of the ANU for their teaching, supervision, and all kinds of assistance which made my stay in Australia enjoyable and memorable. I also wish to express my appreciation for support from the following institutions: Demography Department at the Charles University in Prague; Czech Statistical Office; Czech Family Planning Association; Hungarian Central Statistical Office in Budapest; and Social Science Data Archive at the ANU.

Abstract

During the post-World War II period, widespread resort to induced abortion became a well-known peculiarity of the demographic situation in Eastern European countries. The generally high East European abortion levels resulted from the interplay of several determinants. This study focuses first on population policies and the broader socio-economic and demographic conditions that characterized Eastern Europe during the period 1950-90. It is demonstrated that the emergence of the high-abortion regime coincided demographically with the final stage of secular fertility decline in the region, and politically with the establishment of Soviet-style socialism — a system typified by egalitarian social policies, low material standards of living, limited availability of contraceptives, and policies suppressing personal autonomy and perpetuating inequality between the sexes. Despite the many similarities of the countries under consideration, however, abortion levels differed regionally as well as temporally, reflecting local mores and the effects of country-specific policies related to family and birth control.

With this in mind, using data from official registration sources, the study goes onto examine levels, trends, and selected demographic aspects of abortion in the Czech and Slovak populations, applying both period- and cohort-specific modes of analysis. The findings show that the dominant force behind the resort to abortion was the desire to prevent second and higher-order births in families, whereas its use to space childbearing or avoid it altogether was much less typical. Changes in abortion legislation generated some transitory behavioural responses, but had only limited effect on abortion patterns in the long term. There were substantial differences in the resort to abortion between Czech and Slovak women; this indicates that factors such as socio-economic status, religion, respect for certain social norms, and attitudes to contraception were powerful determinants of reproductive and birth-preventing behaviour. Overall fertility levels were not unaffected by changes in abortion legislation, but the net effects were less dramatic than a simple trend analysis would suggest because the observed fertility declines were partly produced by differences in childbearing patterns between cohorts.

Table of contents

Declaration...ii

Acknowledgments... iii

Abstract...v

Table of contents... vi

List of tables... ix

List of figures... xiii

Chapter 1 Introductory overview...1

1.1 The main theme... 1

1.2 Defining Eastern Europe... 3

1.3 Defining abortion... 6

1.4 Abortion in historical context... 10

1.5 Preliminary review of the literature on abortion in Eastern Europe... 23

1.5.1 Abortion policies... 24

1.5.2 Abortion behaviour... 28

1.5.3 Causes and consequences of abortion practices... 30

1.6 Aims and organization of the present study... 35

Chapter 2 The politics of abortion policy in the countries of Eastern Europe...38

2.1 Introduction... 38

2.2 Population and the Marxist classics... 39

2.3 Soviet Union, 1917-36: revolutionary law and order... 45

2.4 Soviet Union, 1936-55: family revitalized... 51

2.5 Soviet Union, 1955-89: abortion relegalized... 60

2.6 Eastern Europe, 1955-60: following the Soviet lead...68

2.7 Eastern Europe, 1960-89: from monolith to polymorph... 76

2.7.1 Yugoslavia... 81

2.7.2 East Germany...82

2.7.3 Poland...84

2.7.4 Czechoslovakia... 86

2.7.5 Hungary... 88

2.7.6 Bulgaria...90

2.7.7 Romania... 91

2.7.8 Albania...94

2.8 Conclusion... 95

Chapter 3 Fertility in Eastern European countries, 1950-90...98

3.1 Introduction... 98

3.2 Demographic developments before 1950... 99

3.3 Fertility trends and patterns, 1950-90...106

3.3.1 Trends in overall period fertility... 106

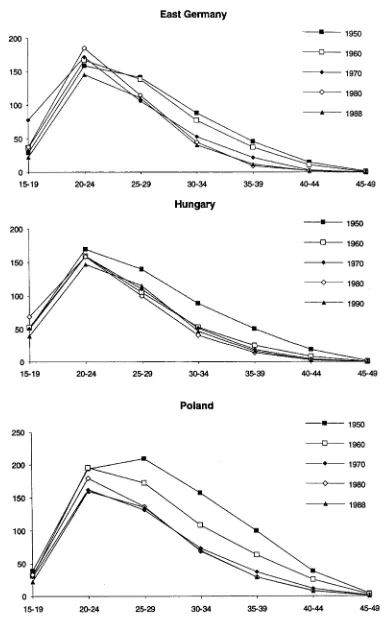

3.3.2 Age-specific period fertility...112

3.3.3 Cohort fertility...123

Chapter 4 Determinants of reproductive behaviour in Eastern Europe... 126

4.1 Introduction... 126

4.2 Socio-economic factors... 127

4.3 Welfare policies... 133

4.3.1 Implementation of 'socialist' policies... 138

4.3.2 Populationist stage... 139

4.3.3 The 1970s and 1980s...140

4.4 Role and status of women... 144

4.5 Marriage and divorce patterns...148

4.6 Desired family size... 158

4.7 Contraception... 164

4.8 Conclusion... 170

Chapter 5 Demographic significance of induced abortion in Eastern European countries... 172

5.1 Introduction... 172

5.2 Data problems... 172

5.3 Levels and trends of induced abortion... 178

5.3.1 Consequences of liberalizing legislation.... ... 181

5.3.2 Consequences of restrictive legislation... 190

5.4 Fertility-inhibiting effects of abortion and other factors compared... 194

5.5 Conclusion... 198

Chapter 6 Demographic dimensions of abortion in the Czech Republic and Slovakia, 1960-90: a period perspective...200

6.1 Introduction... 200

6.2 The Czech Republic and Slovakia compared... 200

6.3 Styles of measurement applicable to available data...210

6.4 Ages of abortion seekers...213

6.4.1 Age-specific abortion rates...214

6.4.2 Median age at abortion...218

6.4.3 Relative concentration of abortion rates by age... 219

6.4.4 Age-specific abortion ratios...222

6.5 Ages of abortion seekers and historical time... 225

6.5.1 3-D plots of age-specific abortion rates... 225

6.5.2 Total abortion rates... 228

6.6 Marital statuses of abortion seekers... 231

6.6.1 Percentage distribution by marital status... 232

6.6.2 Decomposition of TARs by marital status... 234

6.6.3 Abortion rates specific for age and marital status... 235

6.6.4 Decomposition of regional differences in TARs...240

6.6.5 Some explanations... 242

6.7 Parities of abortion seekers...244

6.7.1 Abortion ratios specific for parity, age, and marital status... 246

6.7.2 Abortion rates specific for parity, age, and marital status... 251

6.8 Types of abortions according to circumstances... 254

Chapter 7 Abortion behaviour of Czech and Slovak women:

a cohort perspective... 262

7.1 Introduction...262

7.2 Theoretical considerations... 263

7.3 Computation of cohort measures from period data... 266

7.4 Age-patterns of cohort abortion rates... 269

7.5 Age-specific differences between cohort abortion rates... 274

7.6 Differences in cohort abortion ratios... 281

7.7 Differences in cumulative cohort abortion rates...285

7.8 Conclusion...290

Chapter 8 Estimating fertility responses to abortion policy measures in the Czech Republic and Slovakia... 293

8.1 Introduction... 293

8.2 Policies relevant to fertility and abortion: a recapitulation.... 293

8.3 General trends in fertility, abortion, and conception rates.... 294

8.4 An APC approach to analysing demographic change... 302

8.5 An age-period-cohort model...306

8.6 Data... 311

8.7 Fitting the model... 315

8.8 Separating APC effects... 319

8.8.1 Age effects...320

8.8.2 Cohort effects... 321

8.8.3 Period effects... 323

8.9 Estimating demographic responses to abortion policies implemented in 1957 and 1986... 325

8.10 Analysing components of difference... 331

8.11 Conclusion... 336

Chapter 9 Rethinking Eastern Europe's abortion experience...339

9.1 Summary of previous chapters...339

9.2 Difficulties in explaining abortion experience of Eastern Europe...341

9.3 Policies... 342

9.4 Institutional adjustments and non-adjustments... 347

9.4.1 Health services... 348

9.4.2 Sex education... 349

9.4.3 Mass media... 352

9.5 Behavioural adjustments... 355

9.5.1 Social values... 355

9.5.2 Contraceptive fatalism...359

9.6 Agenda for future research...363

Appendix tables... 370

References...393

Key to symbols used in tables: n.a. not applicable

List of tables

Table 1.1 Definitions of the main demographic terms related to abortion... 11 Table 1.1 Reported births and abortions in Moscow, 1911, 1914,

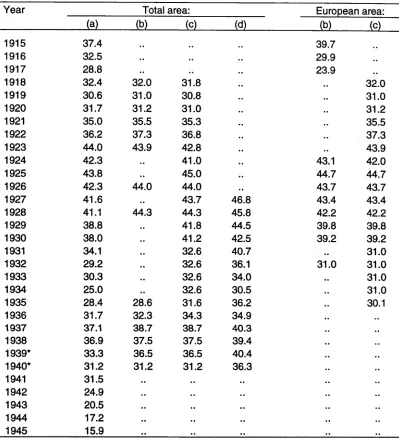

1921-27, 1934-35... 50 Table 2.2 Estimates of crude birth rates for the Soviet Union, 1914-45... 54 Table 3.1 Some socio-demographic data for selected European

countries, selected years 1920-50...102 Table 3.2 Proportions never married at selected ages in some

European populations around 1930... 103 Table 3.3 Estimated populations of Eastern European countries,

selected years 1938-50... 105 Table 3.4 Summary statistics for linear regression analyses of trends

in TFRs in Eastern European countries, 1950-90... 110 Table 3.5 Classification of Eastern European countries according to

types of age pattern of fertility, selected years 1950-90... 117 Table 3.6 Adjusted Gini ratios for fertility rates with respect to age:

Eastern European countries, selected years 1950-90... 120 Table 3.7 Estimated completed fertility in Eastern European

countries (excluding Albania), 1930-60 birth cohorts... 124 Table 4.1 Percentage of population in urban areas in Eastern

European countries, selected years 1950-90...128 Table 4.2 Percentage of labour force engaged in agriculture and

forestry in Eastern European countries, selected years

1950-90...128 Table 4.3 Economic growth in Eastern European countries, 1950-89:

average annual rate of growth of net material product

(per cent)...129 Table 4.4 Percentage of population 25 years of age and over with

no more than first-level education, Eastern European

countries, selected years 1950-90...130 Table 4.5 Waiting periods for housing in selected Eastern

European countries in the 1980s...134 Table 4.6 Overview of the main demographic policies in

Eastern European countries, 1947-89...136 Table 4.7 Percentages of women economically active in selected

age groups in Eastern European countries, selected years

1950-91... 145 Table 4.8 Average desired / ideal number of children in Eastern

Europe, selected countries and years... 161 Table 4.9 Distribution of family size preferences in Czechoslovakia

(per cent) according to results of selected fertility surveys... 162 Table 4.10 Patterns of contraceptive use in Eastern European

Table 4.11 Attitudes towards contraception among Czechoslovak

women in 1991 (percent)...170

Table 5.1 Estimated total legal abortion rates for selected developed countries, selected years 1950-90...179

Table 5.2 Estimated indices of fertility-inhibiting factors, implied and actual total fertility rates, and total abortion rates, selected countries, selected years 1959-91... 196

Table 6.1 Modernization indicators for the Czech Republic and Slovakia, selected years 1950-91... 202

Table 6.2 Religious affiliation in the Czech Republic and Slovakia, 1950 and 1991...205

Table 6.3 Selected demographic indicators for the Czech Republic and Slovakia, annual averages, successive periods 1921-25 to 1985-89... 206

Table 6.4 Average ideal family size in the Czech Republic and Slovakia, results of selected fertility surveys...207

Table 6.5 Patterns of contraceptive use in marriage in the Czech Republic and Slovakia in 1985...208

Table 6.6 Ethnic compositions of the Czech Republic and Slovakia, selected years 1950-91... 209

Table 6.7 Decomposition of period total abortion rates with respect to marital status: Czech Republic and Slovakia, selected years 1961-90... 235

Table 6.8 Components of difference in total abortion rates between the Czech Republic and Slovakia, selected years 1961-90... 241

Table 6.9 Circumstances of abortion: operational definitions... 257

Table 7.1 Comparison of minimum and maximum age-specific abortion rates recorded for cohorts during 1960-90: Czech Republic and Slovakia...277

Table 7.2 Comparison of minimum and maximum age-specific abortion ratios per 100 known pregnancies recorded for cohorts during 1960-90: Czech Republic and Slovakia... 285

Table 8.1 Main policy interventions relevant to fertility and abortion implemented in Czechoslovakia between 1950 and 1990...293

Table 8.2 Levels of analysis within an APC framework...306

Table 8.3 Summary of various models of fertility rates — I ... 317

Table 8.4 Summary of various models of abortion rates — I ... 317

Table 8.5 Summary of various models of fertility rates — I I ... 318

Table 8.6 Summary of various models of abortion rates — I I ...318 Table 8.7 Observed total fertility rates for age group 18-35,

corresponding estimated TFRs derived from APC model, and estimated policy effects: Czech Republic and Slovakia,

Table 8.8 Observed total fertility rates for age group 18-35,

corresponding estimated TFRs derived from APC model, and estimated policy effects: Czech Republic and Slovakia,

1984-90... 328

Table 8.9 Observed total abortion rates for age group 18-35, corresponding estimated TARs derived from APC model, and estimated policy effects: Czech Republic and Slovakia, 1984-90... 329

Table 8.10 Total fertility rates for age group 18-35 derived from APC model under different assumptions, and components of difference between estimated TFRs: Czech Republic and Slovakia, 1957-62...333

Table 8.11 Total fertility rates for age group 18-35 derived from APC model under different assumptions, and components of difference between estimated TFRs: Czech Republic and Slovakia, 1985-90...334

Table 8.12 Total abortion rates for age group 18-35 derived from APC model under different assumptions, and components of difference between estimated TARs: Czech Republic and Slovakia, 1985-90...335

Appendix tables Table A3.1 Total fertility rates for Eastern European countries, 1950-90...371

Table A3.2 Age-specific fertility rates for Eastern European countries, selected years, 1950-90... 372

Table A5.1 Births and abortions, rates and ratios: Albania, 1950-90...374

Table A5.2 Births and abortions, rates and ratios: Bulgaria, 1950-90...375

Table A5.3 Births and abortions, rates and ratios: Czechoslovakia, 1950-90...376

Table A5.4 Births and abortions, rates and ratios: East Germany, 1950-90... 377

Table A5.5 Births and abortions, rates and ratios: Hungary, 1950-90... 378

Table A5.6 Births and abortions, rates and ratios: Poland, 1950-90... 379

Table A5.7 Births and abortions, rates and ratios: Romania, 1950-90...380

Table A5.8 Births and abortions, rates and ratios: Yugoslavia, 1950-90...381

Table A5.9 Births and abortions, rates and ratios: Soviet Union, 1950-90... 382

Table A5.10 Trends in total fertility rates in first five years following liberalization of abortion legislation in selected Eastern European countries...383

Table A6.2 Age-specific abortion rates for five-year age groups:

Slovakia, 1960-90... 385 Table A6.3 Estimated abortion rates specific for age and marital status:

Czech Republic, selected years 1961-90...386 Table A6.4 Estimated abortion rates specific for age and marital status:

Slovakia, selected years 1961-90... 387 Table A6.5 Estimated abortion rates specific for age, marital status,

and parity: Czech Republic, 1970 and 1980... 388 Table A6.6 Estimated abortion rates specific for age, marital status,

and parity: Slovakia, 1970 and 1980...389 Table A7.1 Age-specific abortion rates for selected birth cohorts:

Czech Republic... 390 Table A7.2 Age-specific abortion rates for selected birth cohorts:

Slovakia... 391 Table A8.1 Total fertility, abortion, and conception rates: Czech

List of figures

Figure 1.1 Political divisions of Eastern Europe during 1945-91

and as at June 1993... 5 Figure 2.1 Crude birth rates: Eastern European countries, 1948-90... 78 Figure 3.1 Total fertility rates: Eastern European countries

(excluding Albania), 1950-90...107 Figure 3.2 Regression lines for total fertility rates: Eastern European

countries (excluding Albania), 1950-90... 111 Figure 3.3 Age-specific fertility rates for Eastern European countries,

selected years 1950-90... 113 Figure 3.4 Lorenz curves for the age concentration of fertility,

and relative contributions made to the total fertility rate by women in individual age groups: Albania, 1960, and

East Germany, 1980...121 Figure 3.5 Association between total fertility rate and adjusted Gini

concentration ratio: Eastern European countries,

various dates 1950-90... 122 Figure 4.1 Female total first marriage rates: selected European

countries, selected years 1950-90... 150 Figure 4.2 Female median age at first marriage: selected European

countries, selected years 1950-89... 153 Figure 4.3 Total divorce rates (per 100 marriages): selected European

countries, selected years 1950-90...155 Figure 5.1 Estimated total legal abortion rates: Eastern European

countries, 1950-90... 180 Figure 5.2 Rates per 1,000 population of total registered pregnancies,

live births, and legal abortions: selected Eastern European

countries, 1950-90... 182 Figure 5.3 Observed and expected trends in total fertility rates in the

years around the liberalization of abortion legislation:

selected Eastern European countries, various years... 186 Figure 5.4 'Other' abortions as a proportion of total abortions:

Czechoslovakia, 1958-90... 191 Figure 6.1 Distribution of family size preferences among married

women in the Czech Republic and Slovakia:

1959, 1970, and 1985 fertility surveys... 207 Figure 6.2 Age-specific period abortion rates: Czech Republic and

Slovakia, 1960-90... 215 Figure 6.3 Annual average age-specific rates of abortion: Czech Republic

and Slovakia, successive periods 1960-64 to 1985-90...217 Figure 6.4 Median ages at abortion and childbearing: Czech Republic

and Slovakia, 1950-90... 219 Figure 6.5 Proportion of reproductive life span that produced 50 per cent

Figure 6.6 Age-specific abortion ratios per 100 known pregnancies:

Czech Republic and Slovakia, 1960-90...223 Figure 6.7 First view of 3-D plot of age-specific abortion rates:

Czech Republic and Slovakia, 1960-90...226 Figure 6.8 Second view of 3-D plot of age-specific abortion rates:

Czech Republic and Slovakia, 1960-90...227 Figure 6.9 Total abortion rates: Czech Republic and Slovakia, 1960-90.... 229 Figure 6.10 Annual percentage distributions of abortions by marital status:

Czech Republic and Slovakia, 1960-90...223 Figure 6.11 Abortion rates specific for age and marital status: Czech

Republic and Slovakia, selected years 1961-90... 237 Figure 6.12 Age-specific abortion rates for married and unmarried women:

Czech Republic and Slovakia, 1961-90... 239 Figure 6.13 Parity-specific abortion ratios per 100 known pregnancies

for married and unmarried women: Czech Republic

and Slovakia, 1960-90...247 Figure 6.14 Age-parity-specific abortion rates for married and unmarried

women: Czech Republic and Slovakia, 1970 and 1980...252 Figure 6.15 Relative frequency of abortions according to circumstances:

Czech Republic and Slovakia, 1961-90... 258 Figure 7.1 Lexis diagram illustrating the estimation of cohort-specific

measures from period data...267 Figure 7.2 Age-specific abortion rates for selected birth cohorts:

Czech Republic and Slovakia, 1925-70 birth cohorts... 270 Figure 7.3 Cohort-specific abortion rates for selected ages: Czech

Republic and Slovakia... 275 Figure 7.4 Cumulative fertility rates to exact age 27.5 and abortion rates

at ages 25-29 for cohorts 1935-60: Czech Republic and

Slovakia... 278 Figure 7.5 Age-cohort-specific abortion ratios per 100 known pregnancies,

selected cohorts 1925-70: Czech Republic and Slovakia...282 Figure 7.6 Cohort-specific abortion ratios per 100 known pregnancies

for selected ages: Czech Republic and Slovakia... 284 Figure 7.7 Cumulative abortion rates to specified exact ages: post-war

Czech and Slovak birth cohorts...287 Figure 7.8 Cumulative abortion rates: selected post-war Czech and

Slovak birth cohorts... 287 Figure 8.1 Total period fertility and abortion rates: Czech Republic and

Slovakia, 1950-90... 295 Figure 8.2 Shaded contour maps of age-specific fertility and abortion

rates: Czech Republic, 1950-90... 297 Figure 8.3 Shaded contour maps of age-specific fertility and abortion

rates: Slovakia, 1950-90... 298 Figure 8.4 Age-specific fertility and abortion rates: Czech Republic and

Figure 8.5 Estimated total conception rates: Czech Republic and

Slovakia, 1960-90... 301 Figure 8.6 Observable differences within an APC framework... 305 Figure 8.7 Lexis diagram illustrating age, period and cohort arrangement

of demographic data...313 Figure 8.8 Estimated effects on fertility and abortion from APC models

plotted against age (effect for age 22 is set to 1.0):

Czech Republic and Slovakia, 1950-90...320 Figure 8.9 Estimated effects on fertility and abortion from APC models

plotted against birth cohort (effect for 1945 cohort is set to 1.0): Czech Republic and Slovakia, 1950-90...322 Figure 8.10 Estimated effects on fertility and abortion from APC models

plotted against period (effect for year 1970 is set to 1.0):

[image:15.554.57.478.68.281.2]Chapter 1: INTRODUCTORY OVERVIEW

1.1 The main theme

Dramatic political and social changes that have been taking place in Eastern European societies since 1989 necessitate updating of information and interpretation of the region's past social developments. The present and the future of the former communist bloc have never ceased to depend on a depth of understanding of the region's communist past. Only now, as the newly independent societies in Eastern Europe struggle with serious political, economic, and social troubles, is the so-called 'black box' of Soviet-style communism being opened. In this important sense, Eastern Europe's experience with communism is far from being a topic for historians.

Certainly Eastern Europe could not be viewed merely as an evenly coloured

region on the world political map. Cultural, historical, and social contrasts have

always been enormous. Throughout this study it becomes clear that there have

also been substantial demographic differences between the former Soviet

societies and those of neighbouring countries, as well as between the

non-Soviet populations in Eastern Europe themselves. For many Western observers,

the massive divergences between people living in this region have become fully

apparent only after the end of communist rule, and one of the aims of this work

is therefore to correct the erroneous assumption of 'sameness'.

The choice of questions considered has been limited by the availability of

relevant information (hence the phrase 'aspects of' in the thesis title). The study

relies predominantly on aggregate data and its focus is mainly on the Czech and

Slovak populations. Had it been possible to include comparatively detailed

analyses for other populations of the region or to examine abortion behaviour

using individual-level data, this would have been done, but very little appropriate

information was available. In this context it is important to note that in the

communist regimes of Eastern Europe statistical information was regarded not

only as practically important but also as politically highly sensitive.

Consequently, all published information was carefully censored to serve the

official viewpoint. Inability to prevent unplanned conceptions and unwillingness

to carry such pregnancies to term typically were seen by the political authorities

as inappropriate forms of behaviour, and were therefore not much publicized.

For students of social change wishing to look at issues such as differential

abortion or individual abortion histories, there were officially erected barriers that

prevented or discouraged work which was perceived to be politically sensitive.

The massive political upheavals in 1989 opened the doors to change in all the

formerly Soviet-type countries, yet it is doubtful whether the reformed statistical

services will be able retrospectively to redress the numerous gaps in historical

data series. It is to be hoped that more studies will be undertaken on specific

aspects of abortion in particular Eastern European countries which will add

depth to comparative work in this field.

The aim of this chapter is to give an introductory overview on the issues relevant

to the demographic study of abortion in Eastern Europe. In the initial part,

attention is devoted to the definitions of basic geographic and demographic

terms used in this study. At the core of the discussion are the questions of what

and 'abortion'. Because abortion as a social phenomenon and an object of public policies has a remarkable history, which is important if one seeks to comprehend the role it plays in the contemporary world, the next section of this chapter briefly summarises what is known about the development of the ideological, legal and demographic aspects of abortion since ancient times. The following portion of this chapter is a preliminary overview of the demographic literature that has contributed most significantly to the study of abortion in Eastern Europe in the period since the 1950s. The last section identifies topics that deserve more detailed consideration and presents the organization of the thesis.

1.2 Defining Eastern Europe

Geographic terms attempting to embrace subcontinents or groups of countries often fail to command universal acceptance in demographic writings. The present study investigates abortion and selected related aspects of reproductive behaviour in the former communist-ruled countries of Europe: Albania, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Hungary, Poland, Romania, and Yugoslavia (Figure 1.1a). Of course, the USSR cannot be struck from the list, for it played a crucial role in political and social developments in the eastern part of Europe from the mid-1940s. These nine countries are treated here as one region, but they were at all times very different from one another in their demographic histories, as well as in many aspects of their societies and cultures. Although these countries shared after World War II a similar political fate which has caused deep, far-reaching changes, they never constituted what could be called a true geographic entity (Turnock, 1989). The Soviet Union itself was extremely heterogeneous in every respect; but even within Eastern Europe proper the ethnic and cultural diversity was great.* 1 Perhaps this is why it has always been difficult to give the area comprising these nine countries a simple title.

According to United Nations terminology (UN, 1991a), the family of European communist states was broken into three parts. The USSR was recognized as a separate entity; six countries, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Hungary, Poland, and Romania, were labelled 'Eastern Europe'; and Albania and Yugoslavia were held to be parts of 'Southern Europe'. In order to draw attention to the geo-political realities of the period of communist regimes, some scholars have named the whole region (often excluding the USSR) in slightly different ways: 'Eastern Europe' (Hecht, 1986; Blayo, 1991a), 'East Central Europe' (Kosinski, 1977; Batt, 1991), or 'Central and Eastern Europe' (David and McIntyre, 1981); often, however, without offering a clear explanation of what led them to choose a particular term. A critique of these terms is offered by Ash (1989: 250), who argues that the expression East Central Europe, and the like, confuse the notions of post-1945 Eastern Europe and pre-1914 Central Europe, and therefore should be avoided:

By post-1945 Eastern Europe one means the formally independent member states of the Warsaw Pact... The term Central Europe ... for the period before 1914 ... may be taken to mean those countries that, while subsumed in one of the great multinational empires (Austro-Hungarian, Prussian-German, or Russian), nonetheless preserved major elements of Western traditions: for example, Western Christianity, the rule of law, some separation of powers, a measure of constitutional government and something that could be called a civil society. The western Ukraine and the Baltic states are thus excluded by the first criterion, while Bulgaria is excluded by the second. Romania is a borderline case.

Following 1989, as a result of the fall of communist governments in the Soviet bloc, re-unification of Germany, disintegration of the Soviet Union, territorial division of certain other states, and the subsequent establishment of several new nation states, the 45-years-old division of Europe has disappeared and much of the former political geography has lost its previous meaning (Figure 1.1b). These days, there is less agreement than ever about what groups of countries are to be called 'Central Europe', 'Eastern Europe', or 'Southern Europe'. The use of these labels continues to reflect more the desire to differentiate between socio-political systems than to refer to actual geographic or cultural facts (Batt, 1991; Tismaneanu, 1992; Xiang, 1992). This applies in particular to the expressions 'Central Europe' and 'Eastern Europe', which never

Fig

u

re

1

.1

:

P

o

li

ti

c

a

l

d

iv

is

io

n

s

o

f

E

a

s

te

rn

E

u

ro

p

[image:20.554.66.474.111.700.2]represented phenomena of geography but rather spiritual notions more or less synonymous with the words 'West' and 'East' in their old ideological senses (Kundera, 1984).

In selecting the title for this study, various geographic terms were considered, and for the sake of brevity the term 'Eastern Europe' was finally adopted as the general heading for all the European countries under examination. Thus, in contrast to the terminology used by the United Nations, Albania, the former Yugoslavia, and the former USSR are considered to have been parts of Eastern Europe, because of being higher-fertility, less developed, non-free-market countries. The collapse of the communist bloc after 1989 and the following territorial changes are largely ignored for the purpose of this analysis as they do not materially affect the major arguments. It cannot be overstressed, however, that the term 'Eastern Europe' is used here in relation to a territory which is full of inequities and contradictions, resulting from the divergent historical experiences of the particular national populations.

1.3 Defining abortion

The events in human experience that are most important for demographic research are essentially the facts of life with which people generally are familiar. What the student of demographic change needs, however, is not only a general familiarity with the events that constitute the process of demographic change but also a knowledge of their exact definitions. In the case of induced abortion, moreover, the choice and use of terms are often revealing of societal attitudes (Roe, 1989). That is why the terminology used in discussing abortion is so confused, is slow in changing, and varies from country to country as well as among disciplines dealing with the issue. Broad agreement has yet to be reached on nomenclature, so it is vital to examine briefly the range of abortion- related terms in use.

Statistical Institute and the Health Organization of the League of Nations. However, the standards internationally recommended by these institutions were seldom widely accepted, and many countries preferred their own definitions of vital events for legal and registration purposes (UN, 1954).

In 1950, the Third World Health Assembly adopted the recommendation of a World Health Organization Expert Committee on Health Statistics that the definition of 'foetal death' should be the reverse of 'live birth'. These two definitions are still valid and continue to be the only internationally recommended standards in this area of demographic terminology (WHO, 1950:

12):

Live birth is the complete expulsion or extraction from its mother of a product of conception, irrespective of the duration of pregnancy, which, after such separation, breathes or shows any other evidence of life, such as beating of the heart, pulsation of the umbilical cord, or definite movement of voluntary muscles, whether or not the umbilical cord has been cut or placenta is attached; each product of such a birth is considered live born.

Foetal death is death prior to the complete expulsion or extraction from its mother of a product of conception, irrespective of the duration of pregnancy; the death is indicated by the fact that after such separation the foetus does not breathe or show any other evidence of life, such as beating of the heart, pulsation of the umbilical cord, or definite movement of voluntary muscles.

Unfortunately, the 1950 World Health Assembly did not define the term abortion. It merely recommended dividing foetal deaths into three major categories: early foetal deaths at less than 20 completed weeks of gestation, intermediate foetal deaths at 20 weeks but less than 28 weeks, and late foetal deaths at 28 weeks or more. The Assembly also stated that the last group should be regarded as synonymous with the older and widely accepted concept of stillbirth (WHO,

1950).

months, nearest month, or ordinal month of pregnancy.2 To avoid these

inconsistencies, the use of completed weeks rather than months is generally

regarded as the preferable measurement. As an alternative to the 'conventional

duration of pregnancy' in menstrual weeks, a counting of the 'true duration of

pregnancy' in weeks from the date of conception would also be possible. This

method, however, is seldom employed, since the exact beginning of pregnancy

— the date of fertilization of an ovum by a sperm cell — is usually difficult to

determine; in most cases, it can only be estimated as 10-14 days after the

beginning of the last menstruation (UN, 1954).

How does the term 'abortion' fit into this terminology of foetal deaths? The word

comes from the Latin aboriri — to disappear, pass away, perish by untimely

birth (Lewis, 1980). Etymology itself, however, does not reveal much in this

case. Over the centuries of its use, the term 'abortion' has assumed a variety of

meanings, as well as a number of specific connotations that are dependent on

its context. Medical tradition, for instance, bases the definition of abortion on the

absence of 'viability' in the foetus. Thus, in strictly medical usage, the word

designates the ending of an intra-uterine pregnancy after the implantation of the

fertilized ovum in the endometrium and before the foetus has become capable

of surviving, with appropriate life support, and eventually maintaining an

independent extra-uterine life (Llewellyn-Jones, 1982). For many years, it was

believed that viability is reached at roughly 28 weeks of gestation,

corresponding to a foetal weight of approximately 1,000 grams and a foetal

length about 35 cm (WHO, 1969, 1970; IUSSP, 1982).

However, there is a difficulty in using the traditional criteria of viability, since they

were based merely on the observation that infants born before 28 weeks of

pregnancy, or weighing less than 1,000 grams, had little chance of survival (UN,

1954; Pressat, 1985). Owing to advances in obstetric technologies and methods

of resuscitation from the 1950s onwards the traditional definition of viability has

become debatable, because increasing numbers of infants delivered at fewer

than 24 weeks of gestation or weighing less than 600 grams at birth have been

reported to have survived (WHO, 1970; Tietze, 1983). The resulting disparity in

definitions of abortion was revealed by an inquiry made in 1969 by the World

Health Organization. Among the 66 countries which answered that they had a

definition for statistical purposes, the majority (45) used a criterion of duration of pregnancy; but another eight referred simply to 'viability' without any detailed definition of that term; five countries claimed to use 'the WHO definition' or 'the UN definition' of abortion, neither of which existed in those days; and the remaining eight countries defined abortion by the weight or length of the foetus or by other criteria. In summary, the replies to the WHO survey indicated that 'when countries state that they collect information on abortion, they do so irrespective of whether the country has a definition of the term' (WHO, 1969: 40).3

Because the understanding of viability remains a matter for disagreement, the most suitable way to define an abortion seems to be to use the arbitrary criterion of a dead foetus expelled at less than 28 completed weeks of gestation, measured from the beginning of the last menstruation.4 This definition is used by most of the countries that have adopted a definition of abortion; in addition, it complements the definition of a stillbirth recommended by WHO, and corresponds to definitions used in the International Classification of Diseases since 1938 (WHO, 1970, 1978). Some may argue that even the application of the definition of abortion based on menstrual weeks is not free of obstacles. There are well-known difficulties in determining gestational age in cases where a woman does not remember the date of the beginning of her last menstrual period; never menstruated after a previous pregnancy; or experienced bleeding episodes after pregnancy had been established (WHO, 1969, 1970). Apart from these difficulties of physiological circumstance, there is also a whole set of problems related to social and individual perceptions of abortion. For instance, if a woman undergoes an abortion procedure without really knowing whether a pregnancy has begun, should she be counted as an aborter? These days, in the field of demographic statistics, the term abortion relates to cases where pregnancy has been verified or is at least suspected (Tietze, 1983). Yet some psychologists and gynaecologists tend to view any abortion procedure, even when performed on a non-pregnant woman, as an abortion (Moore-Cavar, 1974). No wonder, then, that discussion about the general definition of abortion itself has a very long, and still continuing, genesis. It remains to be seen whether any new definition, widely acceptable, practically relevant, and better than that using criterion of (estimated) menstrual weeks, will ever be introduced into statistical practice.

The two major categories of abortion are induced and spontaneous. Induced

abortions are those initiated by deliberate action undertaken with the intention of

terminating pregnancy. Abortions not intentionally induced, by contrast, are

called spontaneous, even if an external factor such as a trauma or

communicable disease is involved. Induced abortions carried out according to

the law of a particular country are legal abortions. Procedures induced contrary

to law are called illegal or criminal abortions; they may be performed under

unsafe, unsanitary conditions, or may be as safe as legal abortions, especially

when performed by trained physicians operating outside the law. Legally

induced abortions are often classified according to the legal grounds on which

they were performed. Those procedures undertaken for medical reasons, when

pregnancy is regarded as a condition the cure for which is abortion, are

conventionally described as therapeutic abortions. According to the technique

used, there are abortions induced by curettage, abortions by vacuum aspiration,

abortions by dilatation and evacuation, hysterectomies, and abortions by

medical induction procedures.5

In this study, the term 'abortion1, unless otherwise noted, refers to legally

induced abortions. The word 'miscarriage', often used by the lay public as

equivalent to spontaneous or accidental terminations of foetal life, is rather

obsolete in the scientific context and is avoided for that reason, except in

quotations. Definitions of the main abortion-related terms used in this study are

shown in Table 1.1.

1.4 Abortion in historical context

Abortion is a subject which has long been clouded by secrecy and

misunderstanding. It has been only during the twentieth century that abortion

has moved from the fringes of public concern to the central stage of open

discussion in many countries over the world. As a topic of public and scientific

concern and debate, then, abortion is a relatively recent phenomenon. But as a

very real and private matter, and a component of demographic behaviour, it has

merely continued its ever-present existence. Historians and anthropologists

Table 1.1: Definitions of the main demographic terms related to abortion

Term_____ Conception Foetus

Pregnancy, gestation

Duration of pregnancy

Abortion

induced

legal

illegal, criminal therapeutic spontaneous

Definition_______________________________________ Result of fertilization of an ovum by a sperm cell.

Product of conception developing in the mother's body, until its expulsion or removal. If death occurred before delivery, the term 'foetus' is used even after delivery. Condition of having a developing foetus in the body, normally in the uterus, following conception.

Length of time a woman spends pregnant measured conventionally as the interval between the onset of the woman's last menstrual period and the expulsion or removal of the foetus.

Termination of pregnancy resulting in a dead foetus by less than 28 completed weeks of gestation.

Abortion initiated by deliberate action with the intention to terminate the pregnancy.

Induced abortion performed within the limits of the law. Induced abortion performed contrary to the law.

Legal abortion undertaken for medical reasons. Abortion occurring without deliberation or intent.

Sources: Grebenik and Hill (1974), Moore-Cavar (1974), IUSSP (1977, 1982), Tietze (1982, 1983), Petersen and Petersen (1986).

remind us that 'every known culture, whether literate or preliterate, primitive or modern, has engaged in abortion' (Mall, 1983: 1). However, the extent of abortion practice has varied substantially over time, and has been affected by evolving religious, medical, and philosophical preoccupations, as well as by wide social and economic differentials between particular communities, geographic areas, or historical periods. This section presents a short overview of the history of abortion from pre-Christian times, with the emphasis on developments in Europe.

Abortion may be assumed to be one of the oldest and commonest forms of fertility control. Records of folk-medicine techniques of producing abortion constitute the oldest evidence about the practice of terminating a pregnancy at will. There are indications of the use of abortives under a variety of circumstances in many primitive societies.6 Contemporary doctors would probably remark that ancient abortifacients could hardly be effective; what has to be recognized, however, is that these recipes had both a practical and a symbolic value, and that they demonstrated a serious intent to exercise control over procreation.

The early history of abortion is frequently linked to the study of ethics, theology and law. This is relatively well documented by written sources of both religious and secular origin, and may be traced to ancient times. Particularly for the broader Mediterranean area, where Christianity together with Jewish, Greek and Roman traditions shaped the principles of Western culture, such sources are not scanty, although their completeness and authenticity are often debatable. Given the lack of what could be called the quantitative dimension, the direct demographic relevance of these materials is usually not high. Moreover, demographers would prefer an approach viewing abortion in the context of reproductive behaviour and social life, rather than placed within philosophical and theological disputation. Nevertheless, the continuing attention given to abortion can at the very least be taken as evidence of the employment of such practices. The religious and legal proscriptive and repressive measures known from this period tell the story, just as 'stop' signs imply the existence of traffic in the modern world.

In ancient Greece, the control of fertility was clearly desired and believed to be possible. The general view was that a foetus was never more than potentially a human being; therefore abortion was not condemned. Plato (c.429-347 BC) viewed the termination of unwanted pregnancies as a part of state eugenic policy (Carrick, 1985). Aristotle (c.384-322 BC) recommended that couples practise induced abortion as a means of maintaining the family at an optimum size:

The proper thing to do is to limit the size of each family, and if children are then conceived in excess of the limit so fixed, to have miscarriage induced before sense and life have begun in the embryo (quoted by McLaren, 1990: 18).

Aristotle also maintained that man has a succession of souls: vegetable, animal, and rational; and that animation of the foetus occurred in the male 40 days and in females 80 days after conception (Sheeran, 1987). His theory of delayed ensoulment had a fundamental influence on Christian thinking on abortion for many centuries to come.

I will neither give a deadly drug to anybody if asked for it, nor will I make a suggestion to this effect. Similarly I will not give to a woman an abortive remedy. In purity and holiness I will guard my life and my art (quoted by Carrick, 1985: 69).

However, there has always been some vagueness about what the Hippocratic

oath actually represented. It is often speculated that much of it reflected merely

the conviction that doctors should leave both births and abortions to midwives,

as well as the hostility to surgery, which obviously influenced the medical theory

and practice of ancient Greece (McLaren, 1990). The uncertainty about the

meaning of the Hippocratic oath is augmented by another work ascribed to

Hippocrates which contains a remarkably detailed description of an abortive

technique (Potts, Diggory and Peel, 1977).

Most Romans shared the prevailing viewpoint of the Greeks that the foetus had

no independent existence, and considered it a part of the mother right up to the

birth. A typically liberal approval of abortion can be attributed to Stoics like

Seneca (4 BC - AD 65) who associated life with breath and held that the foetus

did not come alive until it began to breathe (Carrick, 1985). It is true that some

Roman physicians, such as Soranus of Ephesus (AD 98-138), Rome's greatest

writer on gynaecology, restricted abortions to narrowly medical indications; but

such views apparently represented a small segment of general opinion (Himes,

1970). In the Roman mind, a woman was usually considered competent to

request a termination of her pregnancy, and abortion was not as distinctly

separate from contraception as it would be in later societies.

The ancient Greeks' and Romans' predominantly utilitarian approach to

practices such as infanticide and abortion was not particularly intended to meet

the needs of an unwillingly pregnant woman. It was rather designed to

guarantee that the husband, as absolute head of the family, could judge

whether or not the new offspring was desirable. Likewise, if men opposed

abortion it was because they thought that it threatened their interests, not that it

violated foetal life. No wonder, then, that antiquity did not moralize much about

abortion. The idea that abortion is primarily a moral issue is an invention, not

discovery, which was left for the Jews and Christians to make.

The ancient Hebrews believed that the human soul was the one quality which

distinguished man from animals, and that it was only discernible from the

code of Judaism was crystallized in the Ten Commandments, including the

classical command Thou shalt not murder'. According to Exodus a part of the

Old Testament, Jewish law seemed to provide a penalty for an accidental

abortion, but this was not as harsh as the penalty for the killing of a human

being:

When men have a fight and hurt a pregnant woman, so that she suffers a miscarriage, but no further injury, the guilty one shall be fined as much as the woman's husband demands of him, and he shall pay in the presence of judges. But if injury ensues, you shall give life for life, eye for eye, tooth for tooth, hand for hand, foot for foot, burn for burn, wound for wound, stripe for stripe (quoted by Connery, 1977: 8).

It was only in the Septuagint, a Greek version of the Old Testament translated in

the third pre-Christian century, that instead of this wording the explicit penalty

for an intentional abortion appeared (Noonan, 1970). This interpretation was

later incorporated into early Christian dogma.

The advent of Christianity brought about a reorientation of values leading to a

change in attitude toward many issues. Where the new religion was truly

innovative was in making attitudes to sexuality and reproduction the symbols of

the difference between Christians and pagans and the key indicator of individual

morality. The early Christians adopted from the Jews their general respect for

human life at all stages, an attitude which put them in conflict with the

surrounding Roman world where abortion and infanticide were widely accepted.

From this competition, there gradually emerged a dominant Christian view that

not only made chastity a moral ideal but linked it with the concept of

reproduction as the only justification for sexual activity.

Christian objection to abortion was related mainly to speculation about the

existence of a soul, particularly a soul which was the creation of God. An

extensive debate about the origin of the soul and the nature of the foetus

developed over the first 400 years of Christianity, involving figures such as

Tertullian, St. Jerome, St. Augustine, St. John Chrysostom, and many others

(Noonan, 1965, 1970). The arguments from a theological perspective indicate

that the early Christians did not consider as murder an abortion performed

before the soul is in the body. Tertullian (155-220), one of the first Latin Fathers,

followed the ancient doctors in agreeing that one could not talk about the foetus

until quite some time after conception and that an abortion was justified if

(354-430), who played a key role in elaborating the early Christian moral codex,

wrote that 'no soul was present in foetal life until the moment of quickening,

when the mother-to-be detected the first stirrings of life within her body' (Smith,

1970: 27).

Also during the following centuries there were frequent discussions in the

Catholic Church about when life begins, but the debate produced controversial

prescriptions (Connery, 1977; Hurst, 1991). Usually, the church fathers

regarded abortion and contraception as very much the same — attempts to

enjoy sexual pleasure without bearing children — but they did not believe in the

immediate animation of the embryo. Gratian, the classical author in the area of

church legislation, in a codification of Canon Law in 1160 held that abortion was

not murder before the infusion of the soul (Connery, 1977). St. Thomas Aquinas

(1227-1274) maintained, as had Aristotle, that the human soul is infused into

the body of the male foetus about 40 days after conception and into the female

foetus after about 80 days (Rodman, Sarvis, and Bonar, 1987). The

fourteenth-century theologian John of Naples introduced into the debate the view that

aborting an inanimate foetus to save a woman's life should be tolerated, and his

view later found many followers. In the papal constitution Sedes apostolica,

issued by Gregory XIV in 1591 and effective for almost the next three centuries,

the penalty for abortion existed only for an abortion of an animated foetus

(Connery, 1977). Thus, the Catholic position on abortion was for a long time not

as absolute as is commonly believed.

Not until the seventeenth century did Catholic thought consolidate against

induced abortion by assigning to foetal life an importance equal with that of the

mother. In 1620, the Belgian physician Thomas Fienus attacked the Aristotelian

idea of delayed animation of the foetus and worded a new theory of ensoulment

from the time of conception (Connery, 1977). However, it was only in 1869 that

Pope Pius IX, in his constitution Apostolicae sedis, officially promulgated a

marked change in Church law by eliminating the distinction between the formed

and unformed foetus. Even when an abortion was performed to save the life of

the pregnant woman, excommunication was henceforth the penalty for both the

woman and the service provider (Noonan, 1970). The teaching of the Catholic

Church was developed to an almost absolute prohibition of abortion in the

encyclical Humanae vitae issued by Pope Paul VI in 1968 (Carlen, 1983).

According to the theological interpretation of this instrument, only two

cancerous uterus (Callahan, 1970). In recent years, the Vatican's anti-abortion stance has become increasingly uncompromising. The two most authoritative pieces of contemporary papal teaching — the encyclicals Veritatis splendor and

Evangelium vitae issued by Pope John Paul II in 1993 and 1995, respectively —

unconditionally reject any manipulations that result in the destruction of human embryos, including those occurring in relation to procedures such as in vitro

fertilization, as these represent the worldwide expansion of a despicable 'culture

of death' (Fray, 1995). It is certainly not coincidental that the Catholic Church traditionally emerges as a male-dominated, hierarchical institution calling in conservative terms for women's return to their 'natural1, silent and subordinate role. Ironically, though, the Catholic clergy today finds itself in a position quite similar to the one which prevailed two millennia ago: surrounded by an environment in which abortion is broadly practised and tolerated.

This outline of the history of abortion would not be complete without at least a short reference to the views taken by non-Catholic churches in Europe. The Eastern Orthodox Church, like the Roman Church, also claims to be the only infallible Church of Christ, and, like Rome, strongly condemns abortion. St. Basil the Great, in his Three Canonical Letters (374-375), was apparently the first Christian theologian who explicitly rejected the distinction between the ensouled and unensouled foetus. He thus established a strongly anti-abortion tradition which is held by the Eastern Church to the present day (Callahan, 1970). Protestant thinking, in contrast, has always allowed considerable variation of approach to abortion. While the majority of Protestant churches remain silent about the question, some Protestant leaders openly support the idea of abortion as a private decision of the physician and his patient, but Protestant fundamentalists, like Luther and Calvin centuries ago, take the Catholic position (Fletcher, 1970; Sheeran, 1987).7 As regards Judaism, Jewish theology provides little direct guidance on abortion. In summary, Orthodox Jews tend to support a restrictive abortion position, while Conservative and Reform Jews seem to take rather liberal views (Moore-Cavar, 1974).

Little is known about the incidence of abortion in Europe before the twentieth century. Catholic historians such as Noonan (1965, 1970), Callahan (1970) and Connery (1977) have argued that Christians down through the ages always held a firm anti-abortion attitude both in theory and in practice, but apparently this

was not quite the case. The most telling aspect of the history of contradictions among Christian authorities in the timing of the onset of animation or life in the foetus is not their truth or falsehood, which cannot be established, but rather the tendency to harmonize religious tenets with existing social practices. It may be inferred from the repeated arguments of the mediaeval clergy that lay people throughout Europe often infringed religious prescriptions on abortion (Subrtova, 1991); presumably the practice had some currency or it would not have been condemned. Unfortunately, ecclesiastical sources provide no description of family limitation behaviour. Knowledge and practice of abortion are obvious, however, from a variety of other historical sources. For instance, the principal medical textbooks in use in the Western world from ancient times have usually mentioned abortion as a surgical procedure (Himes, 1970). Advances in surgery which took place during the Renaissance, combined with the rise in opposition to Catholic doctrine, probably encouraged the use of induced abortion not only when the mother's life or health were threatened by the pregnancy, but also as a method of fertility control (Rodman et al., 1987). According to a number of studies in historical demography, birth control in marriage was already practised on a more or less wide scale in the eighteenth century in some aristocratic circles in France, England, Belgium, Italy, Spain, Sweden, and Hungary, undoubtedly by means of contraception or abortion (Andorka, 1978; Livi-Bacci, 1986). However, the more general social conditions favouring small families were lacking in Europe until the beginning of the nineteenth century, and the practice of abortion before the transition from high to low fertility was probably rather limited (UN, 1973).

With the period of Enlightenment, the countries of Europe and of European settlement entered a new demographic era.8 European populations had probably never produced the maximum number of children possible, but until the eighteenth century their fertility rates were relatively high and stable. The modern decline in fertility, an integral part of the so-called demographic transition, began during the second half of the eighteenth century, when fertility started to fall in France and also to some extent in Switzerland and Belgium as women began to limit their fertility in marriage. In the nineteenth century, fertility also began to fall in Britain and Scandinavia, and later in Germany and Austria- Hungary. In other countries, especially in Southern and Eastern Europe and Russia, the decline did not commence until the end of the nineteenth or the

beginning of the twentieth century. By the 1930s, birth rates were low in virtually all European populations. There is no completely adequate explanation of why childbearing behaviour changed and precipitated the demographic transition. It is widely agreed, however, that the secular decline in fertility in the now industrialized countries was closely related to basic changes in social and economic conditions which occurred as part of the process of modernization of these societies. Among the crucial factors likely to have facilitated this change were the emotional and economic nucleation of the family, industrialization, urbanization, social mobility, rising levels of education, and reduction of the influence of churches (UN, 1973).

The shifts in attitudes towards reproduction are believed to have been conditioned, among other things, by improved knowledge and acceptability of contraception and abortion. Voluntary birth prevention was at first employed to avoid having children in excess of the number that couples wanted, and later to control the timing of births as well. The existence of such practices is shown, indirectly, by demographic data that indicate steep declines in fertility at older ages and ever-earlier stopping of childbearing by women in European countries throughout the nineteenth century. While abstinence and contraception by

coitus interruptus probably accomplished much of the reduction of fertility, there

is a widespread belief that abortion, as simply one more step on a continuum of fertility-controlling practices, often supplemented ineffective contraception. The frequency of abortions, though hard to establish because of their overwhelmingly secret character, is presumed to have been high even in such nominally Catholic countries as France and Italy.9 Also, medical literature and newspapers of the period suggest that women used folk remedies in the hope of inducing abortion.10 However, there is some evidence that these were such dangerous procedures that women resorted to them only in cases of extreme need, mostly outside of wedlock (Knodel and van de Walle, 1979). Having unplanned births continued to be a not very rare experience for women because there were limited options in the event of an accidental conception.

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the discussion of abortion and fertility, once dominated by the church, was gradually secularized, and the state

9 The broadly accepted explanation is that Catholic women who had had abortions did not really face excommunication because, when they confessed their sin, they were usually granted absolution. There is little doubt that this practice persists in many Catholic countries to the present day.