M a n a g i n g A n t a r c t i c t o u r i s m

by

Phillip John Tracey, BAppSc(Hons)

Submitted in fulfihnent of the requirements

for the Degree of

Doctor of Philosophy

• r - I

Institute of Antarctic and Sdhlthem Ocean Studies

University of Tasmania

This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by

the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and

duly acknowledged in the thesis, and to the best of my knowledge and belief no

material previously published or written by another person except where due

acknowledgment is made in the text of the thesis.

This thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying in accordance with

the Copyright Act 1968.

/o/^/o/

Abstract

Antarctic tourism began before the Antarctic Treaty was signed, and is now a substantial industry exhibiting rapid growth. Concern has been expressed about the effects of tourism on scientific, environmental and other important Antarctic values. The Protocol on

Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty forms the main mechanism for managing Antarctic tourism within the Antarctic Treaty System (ATS). This thesis argues that despite the framework provided by the Protocol, the tourism management system is inadequate, and that the management systems governing similar forms of tourism in other natural areas provide a superior model.

The research included a comprehensive analysis of the industry and its development. Physical, environmental, operational and geographical aspects of Antarctic tourism were analysed. An examination of site use and the spatial development of tourism shows that concern about high use levels is justified for a small proportion of sites, and identifies trends in the geographic spread of tourism activity. The impacts of tourism on Antarctic values were reviewed, with the main concerns identified as low-risk, high-magnitude impacts, and cumulative impacts. Social, economic, and industrial aspects of tourism were analysed. The economic analysis shows the market economic value of the industry to be

approximately fifty five million US dollars for the 1996/97 season. A forecast of the

development of Antarctic tourism predicts continued growth, increasing diversification, and development of substantial new markets.

The management of Antarctic tourism was examined in detail. The system includes tourism management within the ATS, measures imposed from outside the ATS, and industry self regulation. An analysis of the legislative and administrative approaches of different nations shows that there is considerable variation in the way that tourism management provisions of the Protocol are interpreted and applied.

Detailed case studies were conducted on the management of tourism at southern oceanic islands and northern polar locations. The case studies show that cruise tourism is managed very differently in these areas than in the Antarctic, with management planning regarded as the most appropriate model for management. Management measures specific to cruise tourism in high latitude locations were identified.

It is argued that there are significant shortcomings in the tourism management system, based on analysis of the existing system, the characteristics of the industry and the Antarctic environment, management planning theory, and the standards set by management of similar activities in the case study areas.

Acknowledgments

I am very grateful to Bmce Davis, Marcus Haward and Rosemary Sandford for advice, insight, support and patience as supervisors.

The financial support of an Austrahan Postgraduate Award, and an Antarctic Cooperative Research Centre top-up scholarship is gratefully acknowledged. My employers over the period of my candidature have my appreciation for their understanding. I am indebted to the students and staff of the Institute of Antarctic and Southern Ocean Studies, University of Tasmania, and the Antarctic Cooperative Research Centre for the supportive and stimulating academic environment in which I studied. Thanks are due to my office colleagues,

especially Ilse, Siobhan, Edmund and Caroline.

I would like to thank the following for kind and generous assistance, comment on the research, responses to requests for assistance, research materials, case study material, or other assistance: Tom Maggs, Martin Belts, Ewan Mclvor, Lome Kriwoken, Joe

Montgomery, J. Brady, Michael Hall, Margaret Johnston, Peter Timonin, Gary Gauthier, Geoff Copston, Ruth Davis, Gorden Cessford, Paul Dingwall, Greg Mortimer, Darrel Schoeling, Kelvin Michael, Bill Fox, Lynn Peplinski, Marc Maguet, Clay Anderson, Toril Bakken, Svein Halvorsen, and many others. Important information was supplied by the following organisations among others: WWF Arctic Programme, Ministry of Environment (Norway); US NPS-Sitka National Historic Park; US NPS-Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve; US Environment Protection Agency; US NPS-Kenai Fjords National Park;

Marine Section, Prairie and Northern Region, Transport Canada; Northern Region Canadian Coast Guard; Australian Antarctic Division; the UTAS Library Document Delivery Service; and Tasmanian Parks and Wildlife Service.

Many thanks are also due to my friends and family.

Contents

ABSTRACT iv

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS v

CONTENTS vi

FIGURES, TABLES, AND MAPS xiii

ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS xv

INTRODUCTION xvii

i. 1 MANAGING ANTARCTIC TOURISM xvii i.2 DEFlNrriONS AND KEY TERMS xviii i.3 INTRODUCTION TO ANTARCTIC TOURISM xix

i.4 RESEARCH AIMS AND METHODOLOGY xxiv

i.4.1 Aims and objectives xxiv i.4.2 Justification for the research xxv

i.4.3 Limitations of the research xxvi

i.5 THE RESEARCH APPROACH XXvi

i.5.1 Case study design ^^^^^^ i.5.2 Choosing the case studies xxviii

i.5.3 Units of aruxlysis xxix

i.6 THE STRUCTURE OF THE THESIS XXxi

CHAPTER 1: MANAGEMENT LITERATURE AND ANTARCTIC VALUES 1

1.1 ISSUES FROM THE ANTARCTIC TOURISM MANAGEMENT LITERATURE 1

1.1 .a Legal issues: sovereignty, jurisdiction and third parties 2

1.1.b Enforcement 5 1.1.c Growth of tourism 5 1.1.d ATS responses 5 1.1 .e Protected areas and ASTIs 6

1.1.f Status of Recommendations 6 1.1.g Enabling legislation 7 1.1 .h Role of states and national law 7

1.1 .i Need for tourism research, monitoring and evaluation 7

1.1 .j Vessel safety, liability, and insurance 9

1.1.1 Problems with the existing system 9 1.1.2 Debate over the need for change 14 1.1.3 Suggested management options 16

1.1.3.a Comprehensive approaches 21 1.1.3.b Summary of proposed management solutions 25

1.1.4 Recent and ongoing tourism research 27 1.1.5 Summary of the management literature 30

1.2 ANTARCTIC VALUES 32

1.2.1 Use values ^^ 1.2.2 Non-use values ^^ 1.2.3 Non-economic values ^6 1.2.4 Public preference values 36 1.2.5 Wilderness and aesthetic values 36 1.2.6 Physical, chemical and biological systems values 37

1.2.7 Tourism related values 38

CHAPTER 2: PHYSICAL, ENVIRONMENTAL, OPERATIONAL AND GEOGRAPHICAL

ASPECTS OF ANTARCTIC TOURISM 41

2.1 PHYSICAL, BIOLOGICAL AND CULTURAL CHARACTERISTICS 42

2.1.1 Physical resource 42 2.1.2 Biological resource 45 2.1.3 Cultural resource 46

2.2 TOURISM HISTORY AND GROWTH 47 2.3 SHIP BASED TOURISM OPERATIONS 50

2.3.1 The ships 51 2.3.2 Ship and ship to shore operations 54

l.'i.l.z Ice navigation 54

2.3.2.b Ship to shore operations 55

2.3.3 Management of voyages and landings 56

2.3.3.a Crew and passenger briefings 57 2.3.3.b Landing management 57

2.3.4 Environmental aspects of operations 59

2.3.4.a Prevention of oil pollution 59 2.3.4.b Waste management 59 2.3.4.C Preventing the introduction of alien species 59

2.3.5 Incidents arul accidents 59 2.3.6 Operations outside the Peninsula region 60

2.4 AIRBORNE TOURISM 61

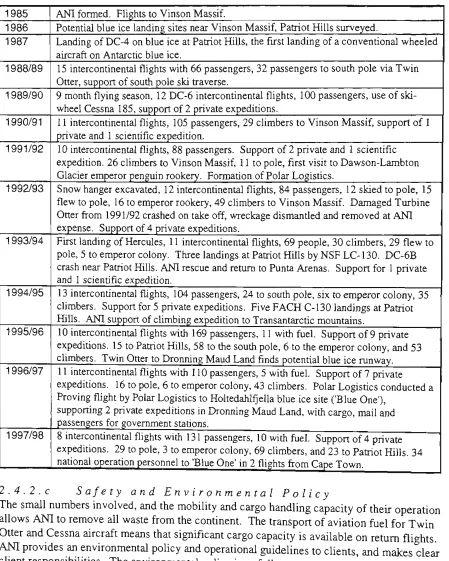

2.4.1 Operations landing tourists 61 2.4.2 Adventure Network Intematiorml 62

l.A.l.d. Development of ANI 63

2.4.2.b Land based facilities 63 2.4.2.C Safety and Environmental Policy 64

2.4.2.d ANI tourist experience . 66

2.4.2.e Incidents 67

2.4.3 Overflights 68 2.4.4 Potential developments in airborne tourism 70

2.4.4.a Airfield availability 70 2.4.4.b Summary and implications 71

2.5 COMMERCIAL YACHT OPERATIONS 72

2.6 SITE USE 72

2.6.1 Site selection and itinerary planning 74

2.6.2 Peninsula Region 74

2.6.2.a Frequency of site use across seasons 75 2.6.2.b Frequency of landings across seasons 75

2.6.2.C Visitor numbers to sites 76 2.6.2.d Summary of landing site use 78 2.6.2.e IRB cruising and helicopter overflights 78

2.6.2.f Change in site use over time 79 2.6.2.g Seasonal site use mapping 80

2.6.3 Continental sites 102

2.6.4 Summary HI

2.7 IMPACTS OF TOURISM 111 2.7.7 Types of impact 113

2.7.1.a Impacts on science 113 2.7.1 .b Impacts on the environment 114 2.7.1 .c Impacts on cultural heritage 118 2.7.1 .d Impacts on wilderness and other values 118

2.7.l.e Positive impacts 119

2.7.2 Identified or postulated impacts 120 2.7.3 Measuring arui monitoring impacts 123

2.7.4 Summary ^^3

CHAPTER 3 : S O C R L , ECONOMIC AND INDUSTRY ASPECTS OF ANTARCTIC

TOURISM 125

3.1 DEMOGRAPHIC AND ATTITUDINAL CHARACTERISTICS O F ANTARCTIC TOURISTS 126

3.1.1 Gender, age, work status, occupation and previous visits 126

3.1.2 Nationality of visitors 127 3.1.3 Attitudes, behaviour and ethics 128

3.1.4 Satisfaction, highlights and desire to return 128

3.1.5 Passenger education 129

3.2 T O U R I S T MOTIVATION 129

3.2.1 Motivations arui expectations 130 3.2.2 Motivational summary 131

3.3 E C O N O M I C CONSIDERATIONS 132

3.3.1 Literature on Antarctic tourism economics 132

3.3.2 Tourism and economic issues 133 3.3.3 Antarctica as a common property resource 134

3.4 A PRELIMINARY ANALYSIS OF ANTARCTIC TOURISM ECONOMICS 135

3.4.1 Methodology 136

3.4.1 .a Calculation of airborne tourism estimate 136 3.4.1.b Calculation of overflight estimate 136 3.4.1 .c Calculation of minimum estimate for shipbome tourism 136

3.4.1.d Calculation of enhanced revenue for shipbome tourism 137 3.4.1 .e Assumptions and limitations of shipbome tourism calculations 138

3.4.2 Results 139

3.4.2.a Results for airbome tourism component 139

3.4.2.b Results for overflights 139 3.4.2.C Results for shipbome tourism 140 3.4.2.d Enhanced revenue results 141

3.4.3 Summary of results and conclusions 141

3.5 T H E TOURISM EXPERIENCE 143 5.5.7 Tourism attractions and the tourism experience 144

3.5.2 Education as part of the tourism experience 145

3.5.3 Other activities 146

3.6 ANTARCTIC TOURISM IN THE BROADER TOURISM INDUSTRY 147

5.6.7 Antarctica as a tourism destination 148

3.6.2 Antarctica in the destination life-cycle 151 3.6.3 Antarctic tourism as ecotourism 151 3.6.4 Global tourism and cruise tourism 153

3.6.5 Expedition cruising 155

3.7 STAKEHOLDERS 156

5.7.7 Non-governmental conservation organisations 156 3.7.1.a Antarctic and Southern Ocean Coalition 157 3.7.1 .b Other NGOs with Antarctic policies 15 8

3.7.l.c World Conservation Union 158 3.7. l.d Oceanites foundation 159

3.7.2 Non-governmental industry organisations 160

3.7.2.a International Association of Antarctica Tour Operators 160

3.7.2.b Other bodies 164 5.7.3 Science and science support organisations j ^

3.7.4 Government agencies 755 3.7.5 Domestic stakeholders 755 3.7.6 Other uses of Antarctica 755

3.8 FUTURE DIRECTIONS FOR ANTARCTIC TOURISM 167

5.5.7 Growth and change in shipbome tourism 757

3.8.2 Growth and change in airbome tourism 76S

3.8.3 Factors limiting growth 170 3.8.4 Changes in tourism products, experiences and markets 7 77

3.8.5 Use of larger vessels 172 3.8.6 Geographic change 174 3.8.7 Land based tourism 174

CHAPTER 4: THE ANTARCTIC TOURISM MANAGEMENT SYSTEM 179

4.1 TOURISM-SPECmC ATS MEASURES 179

4.1.1 From concern to grudging acceptance: 1966-1970 180

4.1.2 The beginning of regulation: 1972-1979 182 4.1.3 Slow progress and the need for review: 1981-1990 183

4.1.4 Emerging options and a middle path: 1991-1994 184 4.1.5 The abandoned draft tourism annex to the Protocol—ATOM XVII 185

4.1.5.a The debate over the draft annex 186

4.1.6 ATCMXVin, Kyoto 1994 187 4.1.7 Fine-tuning and regrouping: 1995-1998 187

4.2 NON-ATS AGREEMENTS 190

4.2.1 Compliance and re-flagging issues 190 4.2.2 Agreements applying to Antarctica 190 4.2.3 Ice navigation-a regime gap 191 4 . 3 RESPONSBELMES OF PARTIES 193

4 . 4 A T S ALTERNATIVES 1 9 4 4.5 ENABLING THE PROTOCOL—LEGISLATION, REGULATIONS, AND PROCEDURES 195

4.5.1 Australia 196 4.5.2 Chile 197 4.5.3 Finland 197 4.5.4 Japan 197 4.5.5 New Zealand 199 4.5.6 The Netherlands 200

4.5.7 Norway 200 4.5.8 Russia 201 4.5.9 South Africa 202 4.5.10 United States 202 4.5.11 Features of the legislative approaches 203

4.6 THE ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT SYSTEM IN PRACTICE 206

4.6.1 impact assessment issues 207

4.7 PROTECTED AREAS 209 4.8 INSPECTIONS AND OBSERVER PROGRAMS 214

4.9 VOLUNTARY MANAGEMENT MECHANISMS 215

4.9.1 Membership oflAATO 215 4.9.2 Guidelines and codes of conduct 216

4.9.2.a The lAATO guidelines 218 4.9.2.b The ATS guidance documents 220 4.9.2.C Effectiveness of voluntary guidance documents 221

4.10 TOURISM AND SCIENCE 222

4.10.1 Managing tourism visits to stations 223

4.11 CONCLUSIONS 224

CHAPTER 5: SOUTHERN OCEANIC ISLANDS TOURISM MANAGEMENT CASE

STUDIES 227

5.1 SOUTHERN OCEANIC ISLANDS 227 5.7.7 The case study region 228

5.1.2 The case studies 228 5.1.3 Case study presentation 231 5.1.4 General description of southern oceanic islands 231

5.2 TOURISM ON SOUTHERN OCEANIC ISLANDS 232 5.2.7 Tourism on non case study islands 233

5.2.2 Southern oceanic island tourism research 235

5.2.2.a Overview papers 235 5.2.2.b SCAR/IUCN Workshop on protection, research and management of subantarctic islands 236

5.2.2.C Social research 237 5.2.2.d Physical impacts 238 5.3 TOURISM MANAGEMENT FOR THE NEW ZEALAND SUBANTARCTIC ISLANDS 238

5.5.7 Physical and environmental resource 238

5.3.2 Historical use and resources 240

5.3.4.a Guidelines for tourism 243 5.3.4.b Minimum impact code 244

5.3.4.C Other features 244

5.3.5 Summary 244

5.4 TOURISM MANAGEMENT FOR MACQUARE ISLAND 245

5.-^.7 Physical and environmental resource 245

5.4.2 Historical use and resources ^46

5.4.3 Tourist visits 246 5.4.4 Management of tourism 247

5.4.4.a Guidelines for tourism 248 5.4.4.b Minimum impact code 249

5.4.5 Summary 250

5.5 TOURISM MANAGEMENT FOR HEARD AND MCDONALD ISLANDS 250

5.5.7 Physical arui environmental resource 250

5.5.2 Historical use and resources 251

5.5.3 Tourist visits 252

5.5.4 Management of tourism 252

5.5.4.a Guidelines for tourism ^^ 5.5.4.b Code of conduct '^^^

5.5.5 Summary

5.6 TOURISM MANAGEMENT FOR THE PRINCE EDWARD ISLANDS 255

5.6.7 Physical and environmental resource 255

5.6.2 Historical use and resources 256 5.6.3 Management of tourism 257 5.6.4 EIA of tourism on Marion Island 258

5.6.5 Summary 259

5.7 TOURISM MANAGEMENT FOR GouGH ISLAND WILDLIFE RESERVE 260

5.7.7 Physical and environmental resource 260

5.7.2 Historical use arui resources 261 5.7.3 Management of tourism 262

5.7.4 Summary 264

5.8 TOURISM MANAGEMENT FOR SOUTH GEORGIA 264

5.S.7 Physical and environmental resource 265

5.8.2 Historical use and resources 266

5.8.3 Tourist visits 266 5.8.4 Marmgement of tourism 267

5.8.4.a Proposed visitor management policy 268

5.8.5 Summary 269

5.9 SUBANTARCTIC TOURISM MANAGEMENT DISCUSSION 270

5.9.7 Management planning 270

5.9.2 Policies on tourism 275 5.9.3 Shore management provisions 275

5.9.4 Administration 277 5.9.5 Differences between the southem oceanic islands and the Antarctic 278

5.9.6 Drawing on other research 279

5.10 CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS FOR ANTARCTIC TOURISM 280 CHAPTER 6: TOURISM MANAGEMENT FOR NORTHERN POLAR LOCATIONS 283

6.1 INTRODUCTION 283

6.7.7 Rationale and case selection 283

6.1.2 The northem polar region 285 6.1.3 Regional tourism activity 288

6.2 ARCTIC-WIDE TOURISM PRINCIPLES 289

6.3 TOURISM MANAGEMENT FOR SVALBARD 292 6.5.7 Physical and environmental resource 292

6.3.2 Historical use and resources 293 6.3.3 Tourism on Svalbard 294 6.3.4 Cruise tourism 295 6.3.5 Management of tourism 296

6.3.5.C Tourism management plan zoning 298 6.3.5.d Additional elements of the management plan 299

6.3.6 Summary ^QQ

6.4 TOURISM MANAGEMENT FOR G L A C E R B AY NATIONAL PARK AND PRESERVE, ALASKA 301

6.4.7 Physical arui environmental resource 302

6.4.2 Historical and cultural use 303

6.4.3 Tourism use J03

6.4.3.a Cruise vessels 303 6.4.3.b Tour boats 304 6.4.3.C Visitor numbers 304 6.4.3.d Tourist characteristics 305

6.4.4 Management planning 305 6.4.5 Vessel management plan 306

6.4.5.a Daily entry restrictions 307 6.4.5 .b Seasonal entry restrictions 307 6.4.5.C Other regulations 307 6.4.5.d Concession system 307 6.4.5.e Other management 308

6.4.6 Summary 308

6.5 TOURISM MANAGEMENT FOR THE CANADIAN ARCTIC 310

6.5.1 Physical and environmental resource 311 6.5.2 Land tenure, ruitional parks and protected areas 312

6.5.2.a Nunavut 312 6.5.2.b Northwest Territories 313

6.5.2.C Yukon 313

6.5.3 Tourism activity 313

6.5.3.a Geographic areas 314 6.5.3.b Tourist characteristics 315

6.5.4 Vessel management and regulation 315

6.5.5 Additional requirements 319

6.5.5.a Federal requirements 319 6.5.5.b Territory government requirements 319

6.5.6 Summary 320

6.6 T H E RUSSIAN ARCTIC AND THE NORTH POLE 322

6.6.7 USSR cruise activity 323

6.6.2 Foreign involvement and access 325

6.7 CRUISE TOURISM TO OTHER ARCTIC DESTINATIONS 326 6.8 NORTHERN POLAR REGIONS TOURISM MANAGEMENT DISCUSSION 327

6.8.1 General discussion 527 6.8.2 Destination characteristics and tourism experiences 328

6.8.3 Management systems and management planning 329

6.8.3.a Environmental assessment 329 6.8.3.b Visitor experience 330 6.8.3.C Limits on tourism 330 6.8.3.d Research and monitoring 330 6.8.3.e Codes of conduct 330 6.8.3.f Management presence 330 6.8.3.g Wildlife dismrbance issues 331 6.8.3.h Administrative arrangements 331

6.8.4 Ice navigation 331

6.9 CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS FOR ANTARCTIC TOURISM 331

CHAPTER 7: EVALUATING THE ANTARCTIC TOURISM MANAGEMENT SYSTEM 333

7.1 ATS GOALS FOR TOURISM MANAGEMENT 333 7.2 PROTECTED AREA MANAGEMENT PLANNING THEORY 335

7.2.7 A sample planning system 335

7.2.2 Wilderness management 337 7.2.3 Visitor management 339

7.2.3.a Carrying capacity 339 7.2.3.b Recreation Opportunity Spectrum 339

7.2.3.C Limits of Acceptable Change 341 7.2.3.d Agency specific visitor management models 342

7.3 RESULTS OF CASE STUDY ANALYSES 346 7.5.7 Southem oceanic island tourism nv2nagement 346

7.3.2 Tourism managementfor northem polar locations 347

7.4 EVALUATING THE ANTARCTIC TOURISM MANAGEMENT SYSTEM 348

7.4.1 Coverage 348 7.4.2 Adequacy 350

l.A.l.z. Lack of a strategic management approach 350

7.4.2.b Lack of a mechanism for implementing management measures 350

7.4.2.C Unclear distribution of regulatory responsibility 351

7.4.2.d Lack of management institiitions 352 7.4.2.e The environmental assessment system 352 7.4.2.f Binding and non-binding measures 354

7.4.2.g The protected area system 354 7.4.2.h Neglect of wildemess and aesthetic values 355

7.4.2.i Monitoring 356 7.4.2.J Site management and management presence 357

7.4.2.k Prevention of pollution 357

7.4.2.1 Safety 358 7.4.2.m Self-sufficiency and contingency planning 358

7.4.2.n Lack of an ice navigation regime 359 7.4.2.0 Conservation of flora and fauna 359

7.4.2.P Level of impact 360

7.5 CONCLUSIONS 361

CHAPTER 8: CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 363

8.1 GENERAL DISCUSSION 364 S.7.7 Factors influencing and constraining tourism mxinagement 367

8.1.2 A need for change 368 8.2 EVALUATION OF PROPOSED MANAGEMENT OPTIONS 369

8.2.1 Comprehensive management systems 372 8.3 MANAGEMENT RECOMMENDATIONS 376

5.5.7 Antarctic tourism management needs 378

8.3.2 Management strategies and actions 381

8.3.3 A way forward 383 8.3.4 Implementing a system within the ATS 385

8.4 CONCLUDING COMMENT 387

APPENDIX 1: ELEMENTS OF THE ANTARCTIC TREATY SYSTEM 389

a l . 1 THE ANTARCTIC TREATY SYSTEM 389

a7.7.7 The Antarctic Treaty 389

al.1.2 Functioning of the ATS 391 al.1.3 Additional components of the ATS 391

al.2 THE PROTOCOL ON ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION TO THE ANTARCTIC TREATY 393 a7.2.7 The Convention on the Regulation of Antarctic Mineral Resource Activities 393

al.2.2 The negotiation of the Protocol 394

al.2.3 The Protocol Articles 394 al.2.4 Annex I to the Protocol: Environmental impact assessment 397

al.2.5 Annex II to the Protocol: Conservation of Antarctic fauna and flora 398

al.2.6 Annex III to the Protocol: Waste disposal and waste management 399

al.2.7 Annex IV to the Protocol: Prevention of marine pollution 400 al.2.8 Annex V to the Protocol: Area protection arui management 401

al.2.9 The proposed liability annex to the Protocol 402

APPENDIX 2: THE PROPOSED TOURISM ANNEX TO THE PROTOCOL 405

APPENDIX 3: RECOMMENDATION XVIH-l AND RECOMMENDATION Vm-9 407

REFERENCES 417

F i g u r e s , t a b l e s , and maps

F I G U R E S

Figure 1.1 Figure 2.1 Figure 2.2

Figure 2.3:

Figure 3.1: Figure 4.1 Figure 4.2 Figure 6.1: Figure 6.2: Figure 7.1:

Value categories and Antarctic values 35

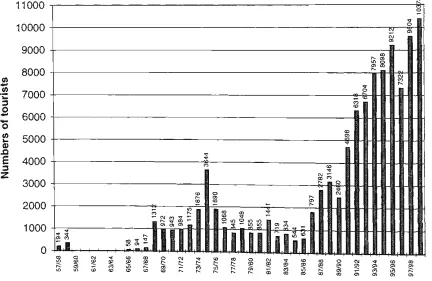

Seaborne tourist numbers 48 Forecast seaborne tourist numbers, lAATO forecast, and line of best fit

based on 1985/86 to 1998/99 figures 49 Total number of landings over nine seasons at each landing site (Peninsula

region) 76 Product and destination life cycles 150

A summary of Rec. XVIII-1 189 Responsibilities of parties relating to tourism 193

Code of conduct for Svalbard tourism 300 Growth in visits on cruise ships and tour boats 304

Framework for NPS Park Planning and Decision Making 335

T A B L E S

Table i. 1: Timeline of events relating to tourism in the Antarctic xx

Table 1.1: Tourism related values 38 Table 2.1: Potential and actual activities by landform 45

Table 2.2: Number (actual and forecast) of operators, ships, and voyages 1992/93 to

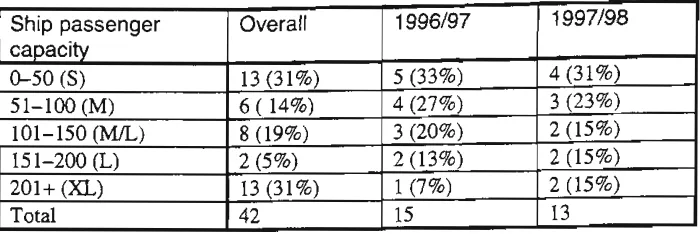

2001/02 50 Table 2.3: Industry structure—ship passenger capacities 52

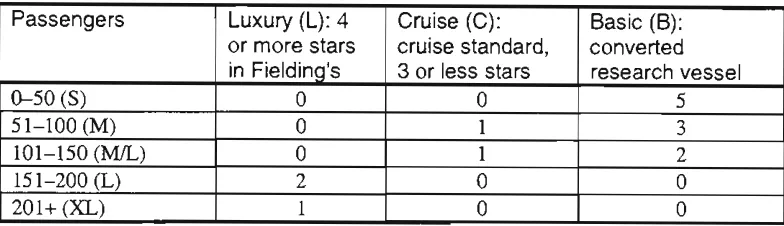

Table 2.4: Antarctic tourism fleet vessel characterisation (1996/97) 53

Table 2.5: Passengers carried by vessel type 1996/97 53 Table 2.6: ANI and Polar Logistics activities and other use of Patriot Hills 64

Table 2.7: Predicted or potential impacts of ANI activities 66 Table 2.8: Reported ANI client numbers participating in different Patriot Hills

programs over 6 seasons 67 Table 2.9: Number of seasons sites were used (Peninsula region) 75

Table 2.10: Total visits over 9 seasons (Peninsula region) 76 Table 2.11: Average visitor numbers by number of sites (Peninsula region) 77

Table 2.12: Details of sites where average annual visitation is more than 1(X)0

(Peninsula region) 77 Table 2.13: Peninsula sites ranking top 5 most visited for 3 or more of 9 seasons 78

Table 2.14: Regularity of site use for IRB cruising or helicopter overflights (Peninsula

region) 79 Table 2.15: Total visits over 7 seasons for IRB cruising or helicopter overflights

(Peninsula region) 79 Table 2.16: Total landing sites and introduction of new landing sites 80

Table 2.17: Areas used for visit mapping (Peninsula region) 101 Table 2.18: Landing site use seasonal distribution (Continental region) 102

Table 2.19: Average visitor numbers by number of sites (Continental region) 103 Table 2.20: Continental region sites where average annual visitation is more than 150 103

Table 2.21: Summary of predicted and actual tourism impacts 121 Table 3.1: Gender, age, work status and previous visits of Antarctic tourists 127

Table 3.2: Nationalities of ti-avellers 1994/95 to 1997/98 127

Table 3.3: Why people visit Antarctica 131 Table 3.4: Total revenue calculation for airbome tourism 139

Table 3.5: Overflight revenue per flight 139 Table 3.6: Suinmary of minimum vessel / company calculations 140 Table 3.7: Comparison between minimum revenue and enhanced revenue estimates 141

Table 3.8: IndusO^ structure: revenue and passengers by company 142

Table 4.2: Table 4.3: Table 5.1: Table 5.2: Table 5.3: Table 5.4: Table 5.5: Table 5.6: Table 5.7: Table 5.8: Table 5.9: Table 5.10: Table 6.1: Table 6.2: Table 6.3: Table 6.4: Table 6.5: Table 7.1: Table 7.2: Table a l . l :

Implementing the Protocol through legislation Application of Protocol implementing legislation Southem oceanic islands

Island visits—companies offering visits 1996/97 season New Zealand subantarctic island visitor characteristics Visits to New Zealand subantarctic islands

Visits to Macquarie island

Southem oceanic islands—management planning

Southem oceanic islands—shore management provisions Southern oceanic islands—administrative and other provisions Southem oceanic islands—conservation characteristics Tourism management provisions

Protected areas in the Arctic

Sununary of WWF principles for Arctic tourism. Code of Conduct for operators, and Code of conduct for tourists

Tourism management provisions for Svalbard

Cruise tourism management. Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve Ship types and Shipping Safety Control Zone entry dates

Relevant lUCN Protected area management categories Steps in the Limits of Acceptable Change Process Summary of the provisions of the Antarctic Treaty

198 199 230 234 238 240 247 271 272 273 274 281 287 290 301 310 318 335 343 390

M A P S

Map 2.1: Inflatable mbber boat (IRB) cmising or overflights - Peninsula Sites Map 2.2: Peninsula site use change series - 89/90 season

Map 2.3: Peninsula site use change series - 90/91 season Map 2.4: Peninsula site use change series - 91/92 season Map 2.5: Peninsula site use change series - 92/93 season Map 2.6: Peninsula site use change series - 93/94 season Map 2.7: Peninsula site use change series - 94/95 season Map 2.8: Peninsula site use change series - 95/96 season Map 2.9: Peninsula site use change series - 96/97 season Map 2.10: Peninsula site use change series - 97/98 season

Map 2.11: Major features and tourist sites (Ross Sea region, Gates Land and West Antarctica)

Map 2.12: Major features and tourist sites (East Antarctica, Enderby Land to Terre Adelie)

Map 2.13: Major features and tourist sites (Dronning Maud Land, Weddell Region and western East Antarctica)

Map 5.1: Southem oceanic islands Map 6.1: Northem polar regions

Map 6.2: Arctic Canada including Shipping Safety Control Zones

Acronyms and abbreviations

AAT AEPS AIRSS AMAP ANARE ANI ANLICA ASAC ASMA ASOC ASPA ASPPR ASTI ATCM ATCP ATP ATS BAScc

CCAMLR CCGN CEE CEMP CEP CITES CLIA CMS COMNAP CRAMRA DPWH EIA EPA FACH GNWT HRSCERA lAATO L^CS ICAIR lEE M O IP IRB lUCN IWC LACAustralian Antarctic Territory

Arctic Environmental Protection Strategy Arctic Ice Regime Shipping Standards (Canada) Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme Australian National Antarctic Research Expeditions Adventure Network International

Alaskan National Interest Lands Conservation Act Antarctic Science Advisory Committee (Australia) Antarctic Specially Managed Area

Antarctic and Southem Ocean Coalition Antarctic Specially Protected Area

Arctic Shipping Pollution Prevention Regulations Area of Special Tourist Interest

Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting Antarctic Treaty Consultative Party Antarctic Treaty Party

Antarctic Treaty System British Antarctic Survey Carrying Capacity

Convention on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (also Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources)

Northem Region Canadian Coast Guard Comprehensive Environmental Evaluation CCAMLR Ecosystem Monitoring Program

Committee for Environmental Protection (of the ATS)

Convention on Intemational Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna

Cruise Line Intemational Association Conservation Management Strategy

Council of Managers of National Antarctic Programs

Convention for the Regulation of Antarctic Mineral Resource Activities

Department of Parks, Wildlife and Heritage (Tasmania) Environmental Impact Assessment

Environmental Protection Agency, US Fuerza Aerea de Chile

Government of the Northwest Territories

House of Representatives Standing Committee on Environment, Recreation and the Arts (Australia)

Intemational Association of Antarctica Tour Operators Intemational Association of Classification Societies

Intemational Centre for Antarctic Information and Research Initial Environmental Evaluation

Intemational Maritime Organisation Information Paper (of the ATCM) Inflatable Rubber Boat

Intemational Union for the Conservation of Nature and Namral Resources (World Conservation Union)

Intemational Whaling Commission

MARPOL 73/78 MBO MPA NERC NGO NMFS NORDREG NPI NPS NSF NWT PAC PATA PEE PERM Polar Code Protocol Rec. ROS SCALOP SCAR SCUBA SGSSI SOLAS SOPEP SPA SPRI SRA SSSI TANGO TAP Treaty UKAHT UN UNCLOS USFWS VAMP VERP VIM VMP WCMC WP WTO WWF

The Intemational Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships, 1973, as modified by the Protocol of 1978

Management By Objectives Multiple-use Planning Area

National Environment Research Council (UK) Non-governmental Organisation

National Marine Fisheries Service (US) Arctic Traffic System (Canadian Coast Guard) Norwegian Polar Institute

National Park Service (US)

National Science Foundation (US) Northwest Territories

Project Antarctic Conservation Pacific Asia Travel Association

Preliminary Environmental Evaluation

Preliminary Environmental Review Memorandum Intemational Code of Safety for Ships in Polar Waters

Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty Recommendation (of the ATCM)

Recreation Opportunity Spectrum

Standing Committee on Antarctic Logistics and Operations (of COMNAP)

Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research Self-contained Underwater Breathing Apparatus South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands

Intemational Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea, 1974 Shipboard Oil Pollution Emergency Plan

Specially Protected Area

Scott Polar Research Institute (UK) Specially Reserved Area

Site of Special Scientific Interest

Tourism and Non-Governmental Operations (working group of COMNAP)

The Antarctica Project Antarctic Treaty of 1959 UK Antarctic Heritage Trast United Nations

United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea US Fish and Wildlife Service

Visitor Activity Management Process

Visitor Experience and Resource Protection Framework Visitor Impact Management process

Vessel Management Plan

World Conservation Monitoring Centre Working Paper (of the ATCM)

World Tourism Organisation

Introduction

i . l M A N A G I N G A N T A R C T I C T O U R I S M

Antarctic tourism continues to grow rapidly, activities of tourists are diversifying, and the industry and destination is maturing. Interest is being shown in the destination by global cmise corporations. Access to the Antarctic as a tourism resource remains open and unregulated. Despite the recent entry into force of a broad environmental protection

instmment within the Antarctic Treaty System (ATS), concerns remain about the impacts of tourism on the Antarctic environment and on science, and about the appropriateness and effectiveness of present management systems.

This thesis is a multidisciplinary smdy of the Antarctic tourism industry, the management of the industry, and case studies of tourism management in other high latitude cmise tourism locations. This research contributes significantly to the understanding of the industry, its stmcture, operations, development, use of the Antarctic resource, and its place in the broader cmise tourism industry.

The thesis argues that the present management system has key weaknesses when the characteristics of the industry, the stated and implied aims of the ATS as regards tourism and conservation management, and best practice management for cmise tourism in similar environments (as established from theory and case smdy research) are taken into account. The thesis supports long-standing calls for more comprehensive regulation of the Antarctic tourism industry.

The last significant management measure passed within the ATS relating to tourism was at the 1994 Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting (ATCM) (Rec. XVIH-l), while the primary instmment, the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty (the Protocol), has been in existence for almost a decade, but has only been in force since 1998. Much of the academic attention paid to tourism regulation dates from the first half of the 1990s. Significant growth of the industry has occurred since that time. Sufficient time has elapsed, and enough progress has been made on implementation of the Protocol, for a consideration of the effectiveness of the tourism management system to be made.

This research provides a comprehensive analysis of the present state of Antarctic tourism and its management. Previous studies have concentrated on specific aspects, including impacts on wildlife, on-site behaviour, site management, or visitor expectations, yet few studies have attempted an overview of all aspects of the industry. Additionally, many authors have called for the examination of tourism management systems in other locations. This thesis provides the first detailed comparative case study research examining cmise tourism management for southem oceanic islands and high latitude northem locations.

This thesis argues that sufficient information is available to make decisions over the need for more comprehensive regulation, the objectives of such regulation, and the form that it should take. This position is in contrast to some who suggest that a better understanding of tourism impacts is required before regulation should be extended. A course of action that can take into account all aspects of Antarctic tourism—^the experiential, economic, legal, and operational aspects of the industry, environmental impacts, the consensus nature of the Antarctic Treaty and Protocol, and interaction with other values of Antarctica—is proposed.

The research has five broad components:

including economics, visitor experience, characteristics of tourists, and tourism theory;

2. an examination of the management system presently in place;

3. case study analyses of cmise tourism management in other high latitude natural areas;

4. an examination of management theory applicable to tourism in natural areas, and an assessment of the present management system; and

5. conclusions and recommendations.

The research used primary sources (multilateral agreements, ATS documents, data on site use, government policy and management documentation, management plans, legislation, non-govemment organisation documents, marketing documents, and industry documents including environmental assessments), as well as drawing on secondary sources and the research of others. Supply of case study documents was the result of the considerable efforts and generosity of many protected area managers and others. Working papers (WP) and information papers (IP) tabled at ATCMs are referred to in the text with details of the author, paper number, year, and meeting, and are listed in a separate reference list.

i . 2 D E F I N I T I O N S A N D K E Y T E R M S

It is necessary to define what is meant by Antarctic tourism. Human activities in the Antarctic include scientific activities conducted by governments, private expeditions,

organised commercial tourism, private self-organised tourism, information activities such as documentary making and joumalism, conservation related activity (such as monitoring of the activities of others, or protest actions), resource activity (such as fisheries activity), and blends of all of these. Further complicating any definition is the fact that many of the activities of people in Antarctica, regardless of the primary reason for their presence, are undertaken for pleasure and recreation. Scientific personnel and support staff are involved in recreational activities during leisure time, which is tourism according to some definitions. On the other hand, the fact that there are no local resident populations removes one

complicating factor.

In defining Antarctic tourism, the insights of other authors are instmctive. A simple definition is used by Enzenbacher (1992b) 'Tourists are defined as visitors who are not affiliated in an official capacity with an established National Antarctic Program' (p. 17). A broader definition, provided by an Australian parliamentary committee, is 'all existing human activities other than those directly involved in scientific research and the normal operations of Antarctic bases' (HRSCERA 1989, p. 3), which includes the recreational activities of government personnel. Hughes and Davis (1995) take a similar approach. Hall and Johnston (1995a) review a number of definitions and identify some definitional

problems. Generally, most find it convenient to break all activity down into two groups— governmental activities (which are relatively easily dealt with by the ATS), and

non-governmental activity, including commercial tourism and private expeditions (which are less easy for the ATS to deal with). When examining tourism management, a definition based on the govemmental nature of activity may be unsatisfactory because of the non-touristic nature of some private expeditions (those conducted by Greenpeace, for example). Some distinguish between commercial and non-commercial tourism activity (Hall &

Johnston 1995a).

incorporating private expeditions. While this research is concerned with many of the same issues as P. Davis, it is felt that the commercial and economic aspects of the tourism industry are fundamentally important for management. Tourism study, as an area of research, also has much to offer an understanding of Antarctic visitation, and rejection of a tourism perspective may limit the adoption of such insights. In addition, all visitation is motivated by values held by individuals for visiting Antarctica, and commercial tourism, rather than being distant from the considerations of conservation, is a direct expression of the values held by travellers.

Another element of the definition is the geographical area in question. Antarctic tourism is centred on the Antarctic continent. The concem is that of how far from the continent into the Southem Ocean should the definition be extended (which ultimately becomes a question of which islands are to be included in the definition). Fortunately, an arbitrary boundary, used for the purposes of the Antarctic Treaty (the Treaty) is suitable—that of 60° south latitude. This boundary roughly converges with areas that are 'Antarctic' in character, and encompasses much of the sea ice zone, the continent and nearby islands. This research distinguishes between the Antarctic and the subantarctic on the basis of sovereignty (some subantarctic islands are subject to sovereign control), and on the basis of the psychological and experiential differences available to tourists (while both the Antarctic and subantarctic islands may be visited in a single voyage, the visitor experiences available are different in a number of respects). The Antarctic Treaty boundary of 60° south latitude is therefore used in the definition of Antarctic tourism employed for this research.

Hall and Johnston (1995a) choose a definition based on intent of the individuals in question, that intent being pleasure or adventure (their definition is for polar tourism rather than Antarctic tourism, but can be readily applied). Their definition takes into account the question of the secondary leisure activities of govemment personnel, by specifically

excluding those whose primary reason for travel is not pleasure related. The definition also concedes that some forms of adventure activity may not be strictly pleasurable. For this work, then, the definition of Antarctic tourism is that used by Hall and Johnston (1995a) limited to the Antarctic region (and excluding military and subsistence activities) as follows:

all travel and associated activities conducted for pleasure or adventure within the Antarctic Treaty area (that is, south of latitude 60° south), exclusive of travel for primarily governmental, resource extraction, or scientific purposes.

1.3 I N T R O D U C T I O N T O A N T A R C T I C T O U R I S M

Tourism is a well established activity in Antarctica. The numbers of visitors (presently around 10 000 people each season) are large in the context of Antarctic activity, and the range of places visited and experiences offered is diverse, and growing. Tourists have been visiting Antarctica for more than a century, although voyages for the sole purpose of tourism are more recent (Headland 1994b, Hall & Wouters 1995, Reich 1980). The majority of tourists travel to Antarctica by ship, normally ice strengthened passenger vessels, or on icebreaker class vessels. Ships provide accommodation, transport, and a vehicle for sightseeing, and obviate the need for shore based infrastmcture. Ships are equipped with inflatable mbber boats (IRBs) with outboard motors to transport passengers to shore, or for use in sightseeing, and some ships also carry helicopters for the same purpose (Hall & Wouters 1995). A small minority of tourists travel by air, most carried by a single company that also supports many of the activities of those engaging in adventure activities such as ski traverses or mountaineering. Other airbome activity includes non-landing overflight

sightseeing in large passenger jets, operating at present from Australia (Headland & Keage 1995). The industry generally involves a small number of operators. A rapid expansion of the industry has been seen in the past decade or so. Tourism is presently limited to a

tourism occurs in the region of the Antarctic Peninsula, as a result of a concentration of attractions, the shorter ship travel times from south American ports, and the relatively ice free waters (Hart 1988, Wace 1990, Enzenbacher 1992b, Cessford & Dingwall 1994, Hall & Wouters 1995).

The entire area south of the latimde of 60° south, which includes the Antarctic continent, ice shelves, and substantial areas of the Southem Ocean, is govemed by the ATS, and is

referred to here as the Treaty area. The Antarctic Treaty of 1959 (the Treaty) from the outset incorporated unusually progressive features, preserving Antarctica as a place of peace and science. The Treaty was negotiated by a number of nations with Antarctic interests, to agree on the disposition of the Antarctic, and the activities of nationals and states in the area. More recently, the major change in the ATS has been the development of an

environmental concem, and eventually of mechanisms to provide environmental protection. The present regime includes the Treaty and associated Recommendations and Resolutions, and the recent, comprehensive Protocol, as well as other instmments relating to specific aspects of the region (collectively known as the Antarctic Treaty System or ATS). Treaty signatories are referred to as Antarctic Treaty Parties (ATPs). Full membership of the ATS (where a state becomes an Antarctic Treaty Consultative Party (ATCP) with rights to participate in consensus decision making) is eamed by conducting scientific research activity in the Antarctic. Other parties may sign the Treaty and be bound by it, but do not have rights to participate in the consensus decision making carried out at ATCMs. As well as developing other agreements for specific issues, the ATCPs have passed

Recommendations (referred to here as Rec.) and more recentiy Resolutions, which represent additional 'mles' of the ATS. All of the decisions and mles of the ATS are applied and enforced through state domestic processes. In a general sense, there are no discriminatory mles applying to tourism—tourism is subject to the same provisions of the Treaty and Protocol as any other activity, although specific Recommendations have been passed referring to tourism issues.

While the history of tourism and relevant ATS provisions are described in detail later, it is useful to provide an overview of important events at this stage. Table i. 1 introduces some of the significant events relating to tourism, including ATS actions, the growth in tourist

numbers, and developments in the industry and in tour operations.

Table i.1: Timeline of events relating to tourism in the Antarctic

Year 1956 1957

1958

1959 1961 1964

1966

1966

1968/69 1968 1968 1968

Event

Tourist overflight of South Shetland Islands and Peninsula. Pan American Airways tourist aircraft lands at McMurdo, Ross Sea region.

First Antarctic tourist cmise, to Peninsula region {Les Eclaireurs), 100 passengers.

Antarctic Treaty signed.

ATCM I, Rec. 9, sets up stmcture for designation of historic sites. Agreed Measures for the Conservation of Antarctic Flora and Fauna, including provision for the declaration of Specially Protected Areas, adopted at ATCM III.

Treaty meeting makes Rec. IV-27, regarding tourist visits to stations.

First cmise organised by Lindblad Travel, on Lapataia, success in this and subsequent seasons prompts the company to build the

Lindblad Explorer. From 1966 tourist voyages run annually.

Tourist numbers exceed 1000 in a season for the first time. South pole overflight, with landing at McMurdo, 70 tourists.

ATCM V, Rec. IV provides for designation of historic monuments. _ Lindblad Travel tourist ship {Magga Dan), crosses Antarctic

circle, visits Ross Sea area for the first time

Reference Headland 1994b Headland 1994b

Reich 1980, Headland 1994b

Lewis-Smith 1994 Heap 1994

Heap 1994

Headland 1994b

Year 1970 1970 1971 1972 1972 1973 1974 1975 1977 1979 1979 1983 1985 1986/87 1987 1988 1989 1989 Event

Treaty Rec. VI-7 concerning: station visits; prevention of

disturbance of science activities; not entering Specially Protected Areas (SPAs); and respecting historic sites. States to ensure tourists abide by principles of Treaty.

First voyage of Lindblad Explorer, first purpose-built expedition cmising ship, built for Lars-Eric Lindblad.

National expeditions (Chilean and Argentine) carrying tourists. Rec. VIM. Moves towards drafting statement for tourists. Initial suggestion of Areas of Special Tourist Interest (ASTI).

Rec, i n of ATCM VII permits designation of Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI).

Large passenger vessel operates in Peninsula region, no landings. Seaborne tourist numbers peak for the decade at 3644.

ATCM Vin passes Rec. VIII-9, to include a Statement of Accepted

Practices and Relevant Provisions of the Antarctic Treaty and Guidance for Visitors to the Antarctic. Sets up mechanism for

ASTIs. Requires visit reporting.

Regular tourist overflights begin, with 40 flights during the next four years, carrying approximately 10000 people.

Statement of Accepted Practices arui Relevant Provisions of the Antarctic Treaty and a practical Guidance for Visitors to the Antarctic finalised and added to Rec. Vni-9. Rec. X-8 encourages

operators to use experienced guides. States to notify airlines that overflights exceed air traffic control, communications, and search and rescue capacities of national programs.

Air New Zealand DC-10 overflight crashes on Mt Erebus, Ross Island, with 257 deaths. Overflights end in Febmary 1980. Annual tourist flights to South Shetiand Islands begin, bringing tourists to Hotel Estrella Polar by 1984, some transfers to and from ships occurring.

Adventure Network Intemational (ANI) formed to provide transport to climbing destinations. Flights to Vinson Massif, refuelling at Teniente Rodolfo Marsh and Carvajal stations, with fuel supplied by Fuerza Aerea de Chile (FACH), and a FACH fiiel drop at Vinson Massif).

Shipbome tourist numbers jump to 1797 after remaining lower since the 1974/75 season. A trend of growth has continued since. ATCM acknowledges rapid increase in tourism and concentration in some sites, and the potential for impacts on science and the environment. A need for assessment and monitoring is noted. ATPs are urged to improve dissemination of existing tourism regulations. ANI landing of DC-4 on blue ice at Patriot Hills—the first landing by a heavy wheeled aircraft on an unprepared blue ice surface in Antarctica.

Regular land based tourism flights begin, with ANI conducting 15 return flights in the 1988/89 season.

Argentine govemment resupply vessel, with 81 tourists goes aground near Anvers Island. Significant oil pollution resulted. Passengers and crew taken to nearby Palmer Station, and

tiransported to Teniente Rodolfo Marsh station and flown out. The ship later sank.

Rec. XV-10 provides for Specially Reserved Areas (SRAs)—areas of outstanding geological, glaciological, geomorphological, aesthetic, scenic or wildemess value. Multiple-use Planning Areas (MPAs) also introduced, intended to ensure multinational activities will not result in combined or cumulative effects on the

environment, or in interference with other activities.

Reference Heap 1994 Headland 1994b Headland 1994b Heap 1994 Lewis-Smith 1994 Headland 1994b Enzenbacher 1992b Heap 1994

Headland & Keage 1995

Heap 1994

Year 1989 1991 1991 1991 1991 1991/92 1992 1992/93 1993/94 1994 1995 1996 1996/97 1996/97 1997/98 1998 Event

ATCM explicitly recognises tourism as a legitimate use. ATCM agrees that a comprehensive review of tourism provisions was needed, and should be conducted by the special ATCM 1990. Working group II, Madrid session of the special consultative meeting initiates a review of tourism issues, agreeing that it would be continued at ATCM XVI.

Intemational Association of Antarctica Tour Operators (LAATO) formed by seven operators. Operational practices and guidelines produced.

Sub-working group of ATCM XVI conducts review of tourism provisions and arranges a meeting of states and others to address tourism regulation issues (Rec. XVI-13).

Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty

approved at XI Antarctic Treaty Special Consultative Meeting. Collapse of Soviet Union begins the process of making more ice strengthened ships available.

Shipbome tourist numbers reach 6318.

Meeting (firom Rec. XVI-I3) advises ATCM XI that tourism regulation issues were considered without any conclusions. Some had stressed that tourism is adequately regulated through the Protocol. Submissions relating to a draft tourism annex to the Protocol are considered.

Chilean flights of tourists to South Shetiand Islands cease.

Tourist overflights resumed (Qantas), with 6 flights. First landing of a wheeled Hercules at Patriot Hills by ANI, landings also by C-130 of the US National Science Foundation (NSF).

Rec. XVIII-1 relating to tourism passed, including a Guidance for

Visitors to the Antarctic, and a Guidance for those Organising and Conducting Tourism and Non-govemmental Activities in the Antarctic.

Resolution 3 (1995) outiines reporting requirements. Private climbing expedition, Transantarctic mountains supported by ANI. Decision by ATCM XX to use a standardised advance notification and post activity report form for a trial period of one year. ANI extends operations to Dronning Maud Land.

Ship-bome tourist numbers 9212.

First complete circumnavigation of Antarctica by tourist ship,

Kapitan Khlebnikov for Quark Expeditions.

Shipbome tourist numbers 9604. Protocol enters into force.

Reference Heap 1994 Heap 1994 Stonehouse 1992b Heap 1994 Heap 1994 Enzenbacher 1993a Heap 1994 Headland 1994b Headland & Keage

1995, Swithinbank 1994 ATCM 1994 ATCM 1995, Swithinbank 1995 ATCM 1996, Swithinbank 1997a NSF 1997 Splettstoesser, Headland & Todd

1997 NSF 1998 Richardson 1998

A preliminary review of the issues surrounding Antarctic tourism identified a range of important features. The broad geopolitical context is characterised by:

the absence of a single governmental / administrative authority. Instead, a system exists where nations signatory to a multilateral treaty reach consensus during regular meetings; • a geopolitical environment that lacks clear and recognised sovereignty, with resultant

legal implications;

• regulation based on an intemational treaty, expressed through enabling legislation in countries party to the treaty;

• political implications of tourism activity for different state actors—tourism has emerged as an issue for states within the ATS, and state involvement (through citizen

• the development of self regulation measures by the tourism industry, and a high level of responsibility demonstrated by operators; and

• the prominence given in the ATS to science and research, and the resultant need for tourism to co-exist with these uses.

Much of the Antarctic region is remote from developed infrastmcture and population centres. Conditions imposed by this remoteness are that:

monitoring, enforcement or assessment of tourist behaviour is very difficult; monitoring impacts and effects is difficult;

safe tourism operations are logistically complicated; activities occur over a vast continental area;

the visitor experience often involves substantial sea travel in rough waters; and

operations in many cases need to be autonomous, and include a capacity for self rescue.

Antarctic tourist operations are:

• predominantly ship based (supplying transport and accommodation);

• dependent on landings and cmising in small inflatable motor boats (or on the use of helicopters); and

• relatively high cost.

Climatic and physical conditions are also unusual. Conditions include:

• adverse climate, including potentially life threatening extreme cold, and high winds; • cold climate vessel operating hazards, such as sea ice and icebergs;

• a short operating season dictated by sea ice and climatic conditions;

• potentially dangerous terrain, including crevassed ice surfaces and other glacial hazards; • poor charting and mapping, increasing risks of navigation; and

• unstable near shore ice conditions, including wind affected sea ice and unstable icebergs.

The physical and environmental features of the Antarctic region: • include unique floral and faunal assemblages;

• mean that the region is sensitive to potential impacts;

• are a source of very important symbolic, non-use, and existence values of global importance;

• are a dominant component of the visitor experience; • include unique scenic values;

• provide important data for scientific activities; and • are an important source of biodiversity.

Very significantly, no local people or permanent inhabitants are present in the Antarctic, a feature unusual in tourism situations.

Two features stand out. First, Antarctic tourism operates in an environment that is highly valued for natural and scientific reasons, which imposes constraints on activities and on management. The region is laden with symbolic value, representing for many the 'last great wildemess'. These values are generally regarded as being of extreme importance. In addition, geography and climate create challenging conditions not equalled even in Arctic regions, conditions that are a dominant factor in shaping tourism. Second, Antarctic tourism operates in a unique intemational relations context. Antarctica, govemed according to the provisions of the ATS, is unique in that it lacks clear and undisputed sovereignty. Tourism operates within a multinational legal regime. These two factors dominate and direct the form and management of Antarctic tourism, and serve to differentiate it from other tourism situations.

Antarctic tourism relies on and affects the physical environment, while remaining a human and therefore social pursuit. For this reason, neither social nor physical science approaches alone are sufficient for understanding and managing Antarctic tourism, and a

multidisciplinary approach is necessary.

i.4 R E S E A R C H A I M S A N D M E T H O D O L O G Y

i . 4 . 1 A I M S A N D O B J E C T I V E S

The research aims and objectives were developed after a literature review (section 1.1) and a preliminary review of the tourism industry and management system. The literature review identified a number of important areas of research that require attention, as well as issues that need to be taken into account when considering Antarctic tourism management. As part of the literature review, recent and ongoing Antarctic tourism research was examined.

The central question surrounding Antarctic tourism relates to the need for a more

comprehensive regulatory regime. While the ATS agreed to the present system in the mid 1990s, there was significant support for a more comprehensive tourism regulation regime prior to that time, and many argue that such a regime will eventually be necessary.

This research therefore aimed to examine the need for a more comprehensive tourism management regime within the ATS.

Central propositions were selected to focus the research. These were:

that the present Antarctic tourism management system is deficient in some respects, when judged against nature tourism management theory, and against the examples provided by tourism management in other areas;

• that many of the problems encountered, and likely to be encountered in Antarctic tourism management are not unique, and that methods for coping with these problems have been developed and tested, and can be applied to Antarctic tourism management; and

• that the present form of the tourism management system is not the only form that could exist under the ATS.

The following objectives intended to satisfy the main aim of the research, and were derived from the literature review and from the preliminary review of Antarctic tourism. The objectives of the research were to:

conduct a comprehensive analysis of Antarctic tourism, including physical, environmental, operational, geographical, social, economic, and industry aspects; conduct a comprehensive and up to date (post-Protocol) analysis of the management system that applies to Antarctic tourism, including ATS components, those outside the ATS, self regulation, and implementation issues;

clarify the values surrounding Antarctic tourism;

examine and analyse tourism management in case study areas with similar characteristics to those pertaining in the Antarctic;

examine tourism theory, especially destination development theory to help understand likely developmental trends in Antarctic tourism;

examine management planning theory to identify important concepts and elements that may have application to the management of Antarctic tourism;

identify goals, aims and objectives for tourism management implied in the present regulatory system;

to the implied management goals, aims and objectives, case smdy management findings, and management planning theory;

examine alternatives to the present management system, and propose options and alternatives that would provide better outcomes for environmental protection, the industry, and ATS needs.

The research stmcmre and process was designed to accommodate these objectives and ensure the appropriate data for addressing the propositions would be obtained.

i . 4 . 2 J U S T I F I C A T I O N F O R T H E R E S E A R C H

The numbers of people visiting Antarctica represent a very small portion of global travel, yet Antarctic tourism receives considerable attention from environmentalists, politicians, NGOs, members of the public, scientists, and social researchers. This level of attention is indicative of the importance of Antarctic tourism. Any study of Antarctic tourism

management must recognise the underlying reasons for this importance. These include: the potential for important Antarctic values to be affected by tourism;

the symbolic importance of Antarctic tourism;

the stams of tourism as one of the largest uses of the continent; the recent and continuing rapid growth of tourism; and

political perceptions of tourism.

There are some powerful and compelling values associated with the southem continent. Some of these values may be affected by tourism. Section 1.2 describes a typology of values, including use and non-use values. Scientific values, by virtue of the unique geographical, biological, geological, and climatological characteristics of Antarctica, are very high. Environmental values (including values for living resources) are clearly significant, as is shown by support for Antarctic conservation in a variety of fomms. Wildemess values are very significant, and probably represent the most important value associated with Antarctica for the global public. Tourism is widely perceived to have the potential to impact on these values.

Antarctic tourism also plays a symbolic role. It represents human economic use of the last substantially unmodified continent, and is symbolic of the relationship between humans and the environment and human desires to 'conquer' all frontiers. This symbolism is highlighted by the fact that travel and tourism are represented by some as a non-essential, frivolous, unnecessary and privileged activity, in contrast to the other major use of Antarctica, science, which is generally represented as an important and valid use of Antarctica.

Tourism is the second substantial use of the continent itself, exceeded only by the activities of governments. Annual tourist numbers have for some time exceeded those of scientists and support staff. As a result, a significant proportion of the attention focused on Antarctic issues is directed toward tourism.

In the last fifteen years or so, Antarctic tourism has grown very rapidly. While fumre trends are uncertain, the possibility of continued growth must be entertained. The potential for continued growth increases the stakes in tourism management, and increases the possibility of unforeseen problems.

It is also suggested that Antarctic tourism has importance beyond the Antarctic region. Initiatives in Antarctic tourism, developed as a result of environmental concerns, may have wider application in tourism in natural areas in other parts of the world (Smith 1994).

Finally, Antarctic tourism is no less worthy of examination in its own right than any other Antarctic phenomenon. It is interesting as:

• it provides employment, generates income and wealth, and services the wants of people; an activity in Antarctica that interacts with other uses and with the natural environment; • a significant and problematic part of the intemational governance experiment of the

ATS;

• one of the few internationally cooperative activities on a continent dedicated to such values; and

part of a wider phenomenon of expedition cmising and cmise tourism.

All of these reasons validate further study and analysis of Antarctic tourism management.

i . 4 . 3 L I M I T A T I O N S O F T H E R E S E A R C H

There were a number of limitations to the research. First, despite the lengthy treatment of the material, it is not completely comprehensive. Constraints of time and access to information mean that some aspects of the research are less detailed than would be ideal. Case study analysis, for example, was directed at the most appropriate and comparable cases, but it is acknowledged that additional useful cases remain unexamined.

A second constraint related to the need to rely on the goodwill of other parties to provide documentation for many aspects of the research. Responses to requests for material were without exception generous and useful, but there are limits to the information that can be obtained using such methods. Personal visits to access management information, and to interview key people were not possible. The relationship between management intent (as expressed in planning and management documents) and management outcomes is not always certain. It would be desirable to have assessed the actual effectiveness of the management systems for the case studies.

Similarly, the research is limited by the fact that the author was unable to participate in a commercial tourism visit to Antarctica. While the author has previous Antarctic experience, direct observation of the industry would have been beneficial, although anything other than a limited exposure to one or a few operations would be difficult to achieve.

The research has not included a full historical analysis of the positions and policies of different ATPs. While such a review would be interesting, limitations of time precluded it, and the research was therefore restricted to considering broad factional positions and general ATS responses. Similarly, a comprehensive analysis of the positions of different stakeholders was not possible.

The analysis of most aspects of the industry includes information up to and including 1997/98. While by the time of completion of the thesis more information had become available, incorporation of it was not possible. Similarly, developments at ATCMs after 1998 were not considered, although no developments are known to have occurred that alter the arguments or conclusions of this thesis.

i . 5 T H E R E S E A R C H A P P R O A C H

Information was obtained to complete the objectives identified in section i.4.1. Information sources included academic papers and critiques, govemment policy statements and reports, submissions to ATCMs, non-govemmental organisation (NGO) documents, formal

Hall and Johnston (1995a) discuss the value of comparing the two polar regions. They contend that 'there is much to be gained by considering the two polar regions, despite their differences. The major issues are the same: regulation of tourists, protection of the

environmental and cultural heritage, management of transnational space, and effects on local populations' (p. 3). Shared problems and experiences can be demonstrated through analysis of tourism development, management and policy (Hall & Johnston 1995a). These authors also provide a broad comparison between Antarctic and Arctic tourism as a whole (Hall & Johnston 1995a, p. 4). The two most important differences identified by Hall and Johnston are sovereignty (the lack of it in the Antarctic, and the presence of it in the Arctic) and the presence of local and especially indigenous people in the Arctic. The Govemment of Norway felt that the development an appropriate management regime and codes of conduct for operators and visitors might benefit from the comparative study of polar tourism (cited in Johnston & Hall 1995). It is also clear from the preliminary review (section i.3) that the intemational relations environment in which Antarctic tourism is managed has had some effect on the way the management system has evolved. It is reasonable to assume that cases where the complicated intemational relations effects are not present may provide useful data about managing tourism in natural areas.

i . 5 . 1 C A S E S T U D Y D E S I G N

There is merit in the analysis of Antarctic tourism management in its own right. Additional information can be provided, however, using comparative case smdies. The basic principle behind the use of additional cases is that Antarctic tourism management can benefit from the experience available worldwide in nature tourism management. This assumes that these experiences are applicable, and that they have relevance for the Antarctic tourism simation. This research investigates this possibility, as well as the altemative—^that Antarctic tourism is so different that other management experiences have nothing to contribute. Based on the preliminary review it was considered likely that other cases would provide useful examples. Given this, the case study method used in the research needs to be briefly described. The method followed here is as described by Yin (1991). This approach is adopted for reasons of simplicity, clarity, rigour and practicality of application. In general terms, comparative case methods are widely used and accepted in research of this nature. Sufficient

information is presented here to validate the theoretical basis for the use of the case study methodology. According to Yin, a case study is an empirical enquiry that:

Investigates a contemporary phenomenon within Its real life context; when the boundaries between phenomenon and context are not clearly evident; and in which multiple sources of evidence are used. (1991, p. 23)

The research design involves a single case (Antarctic tourism) set beside a multiple case study of other tourism cases. The research does not intend to achieve parity between the Antarctic case and the other cases in terms of depth of analysis and detail. The case study method is useful for examining what Yin characterises as 'how' and 'why' questions, as it can deal with 'operational links needing to be traced over time, rather than mere frequencies or incidence'(Yin 1991, p. 18).

One difficulty with Antarctic tourism (and to some extent with any similar question) is the extent to which other experiences or situations can be considered comparable. Sartori argues that 'to compare is both to assimilate and to differentiate to a point, and that 'the comparisons in which we sensibly and actually engage are thus the ones between entities whose attributes are in part shared (similar) and in part non-shared' (1991, p. 246). This point forms the rationale for the multiple case approach of this research. While it may be argued that Antarctic tourism has unique characteristics and is therefore incomparable with any other situation, the reality is that it also shares many important characteristics with other situations, and that a comparative approach is therefore valid. As Sartori (1991, p. 246) points out, 'if two entities are similar in everything, in all their characteristics, then they are a same entity—and that is that.'