DESIGN

DISCOURSE

Composing and Revising

Programs in Professional

and Technical Writing

Edited by

David Franke

Alex Reid

Anthony DiRenzo

DESIGN DISCOURSE

Design Discourse: Composing and Revising Programs in Professional and Technical Writing addresses the complexities of developing profes-sional and technical writing programs. The essays in the collection offer re-flections on efforts to bridge two cultures—what the editors characterize as the “art and science of writing”—often by addressing explicitly the tensions between them. Design Discourse offers insights into the high-stakes deci-sions made by program designers as they seek to “function at the intersection of the practical and the abstract, the human and the technical.”

David Franke teaches at SUNY Cortland, where he served as director of the professional writing program. He founded and directs the Seven Valleys Writ-ing Project at SUNY Cortland, a site of the National WritWrit-ing Project.

Alex Reid teaches at the University at Buffalo. His book, The Two Virtuals: New Media and Composition, received honorable mention for the W. Ross Winterowd Award for Best Book in Composition Theory (2007), and his blog, Digital Digs (alex-reid.net), received the John Lovas Memorial Academic We-blog award for contributions to the field of rhetoric and composition (2008).

Anthony Di Renzo teaches business and technical writing at Ithaca College, where he developed a Professional Writing concentration for its BA in Writing. His scholarship concentrates on the historical relationship between profes-sional writing and literature.

Perspectives on Writing

Series Editor, Michael PalmquistThe WAC Clearinghouse

http://wac.colostate.edu

PERSPECTIVES ON WRITING Series Editor, Mike Palmquist

The Perspectives on Writing series addresses writing studies in a broad sense. Consistent with the wide ranging approaches characteristic of teaching and scholarship in writing across the curriculum, the series presents works that take divergent perspectives on working as a writer, teaching writing, administering writing programs, and studying writing in its various forms.

The WAC Clearinghouse and Parlor Press are collaborating so that these books will be widely available through free digital distribution and low-cost print editions. The publishers and the Series editor are teachers and researchers of writing, committed to the principle that knowledge should freely circulate. We see the opportunities that new technologies have for further democratizing knowledge. And we see that to share the power of writing is to share the means for all to articulate their needs, interest, and learning into the great experiment of literacy.

Existing Books in the Series

Charles Bazerman and David R. Russell, Writing Selves/Writing Societies (2003) Gerald P. Delahunty and James Garvey, The English Language: from Sound to

Sense (2010)

Charles Bazerman, Adair Bonini, and Débora Figueiredo (Eds.), Genre in a Changing World (2009)

COMPOSING AND REVISING

PROGRAMS IN PROFESSIONAL

AND TECHNICAL WRITING

Edited by

David Franke

Alex Reid

Anthony Di Renzo

The WAC Clearinghouse wac.colostate.edu

Fort Collins, Colorado

Parlor Press

www.parlorpress.com

The WAC Clearinghouse, Fort Collins, Colorado 80523-1052

Parlor Press, 3015 Brackenberry Drive, Anderson, South Carolina 29621

© 2010 David Franke, Alex Reid, and Anthony Di Renzo. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication

Design discourse : composing and revising programs in professional and technical writing / edited by David Franke, Alex Reid, Anthony DiRenzo.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-60235-165-3 (pbk. : alk. paper) -- ISBN 978-1-60235-166-0 (hardcover : alk. paper) -- ISBN 978-1-60235-167-7 (adobe ebook : alk. paper)

1. English language--Rhetoric--Study and teaching (Higher)--United States. 2. Academic writing--Study and teaching (Higher)--United States. 3. Technical writing--Study and teach-ing (Higher)--United States. 4. Writteach-ing centers--Administration. I. Franke, David, 1960- II. Reid, Alex, 1969- III. DiRenzo, Anthony,

PE1405.U6D47 2010 808’.0420711--dc22

2010001091

Copyeditor: Annabelle Bertram Designer: David Doran

Series Editor: Mike Palmquist

The WAC Clearinghouse supports teachers of writing across the disciplines. Hosted by Colo-rado State University, it brings together scholarly journals and book series as well as resources for teachers who use writing in their courses. This book is available in digital format for free download at http://wac.colostate.edu.

Preface

ixComposing

31 The Great Instauration: Restoring Professional and

Technical Writing to the Humanities

5Anthony Di Renzo

2 Starts, False Starts, and Getting Started:

(Mis)understanding the Naming of a Professional Writing Minor

19 Michael Knievel, Kelly Belanger, Colin Keeney, Julianne Couch,and Christine Stebbins

3 Composing a Proposal for a Professional / Technical Writing Program

41 W. Gary Griswold4 Disciplinary Identities: Professional Writing,

Rhetorical Studies, and Rethinking “English”

63Brent Henze, Wendy Sharer, and Janice Tovey

Revising

875 Smart Growth of Professional Writing Programs:

Controlling Sprawl in Departmental Landscapes

89Diana Ashe and Colleen A. Reilly

6 Curriculum, Genre and Resistance: Revising Identity in a Professional

Writing Community

113David Franke

7 Composing and Revising the Professional Writing Program

at Ohio Northern University: A Case Study

131Minors, Certificates, Engineering

1518 Certificate Programs in Technical Writing: Through Sophistic Eyes

153 Jim Nugent9 Shippensburg University’s Technical / Professional Communications

Minor: A Multidisciplinary Approach

171Carla Kungl and S. Dev Hathaway

10 Reinventing Audience through Distance

189Jude Edminster and Andrew Mara

11 Introducing a Technical Writing Communication Course

into a Canadian School of Engineering

203Anne Parker

12 English and Engineering, Pedagogy and Politics

219 Brian D. BallentineFutures

24113 The Third Way: PTW and the Liberal Arts in the

New Knowledge Society

243Anthony Di Renzo

14 The Write Brain: Professional Writing in the

Post-Knowledge Economy

254Alex Reid

Post-Scripts by Veteran Program Designers

27515 A

Techné

for Citizens: Service-Learning,

Conversation, and Community

277James Dubinsky

16 Models of Professional Writing / Technical Writing Administration:

Reflections of a Serial Administrator at Syracuse University

297 Carol LipsonDavid Franke

This book grew out of the challenges of starting and sustaining a Profes-sional and Technical Writing program at the state college where Alex Reid and I were hired (nearby, co-editor Anthony Di Renzo began his program at Ithaca College in New York a few years before us). We found ourselves building our program at the intersection of several academic and semi-academic discourses— rhetoric, English, new media, business, publishing, composition and others. We had plenty of theory from these fields and personal experience as students, teachers, writers, and freelancers. Yet as we established our identity as a major, we found that our interactions with other departments (especially English), our entanglement with the long-standing academic tensions between “liberal” and “vocational” education, the demands of staying abreast of new technology, the way our resources and students were distributed across many disciplines—all these pressures and others combined in unexpected ways, presenting us with a bit of a paradox in that we were compelled to make sense of the whole while we struggled with the day-to-day work of running a new program; simultaneously, most day-to-day decisions depended on a sense of our whole—our mission, rhythms, audiences, and strengths. Seen from a purely analytical perspective, what we were trying to do seemed impossible.

But of course it wasn’t impossible. Our experience beginning a PTW program at the State University of New York at Cortland was typical in many ways. The undergraduate program we were hired to bring to fruition, like many others, was simply hard to define, lacking a deep sense of tradition that English and even rhetoric programs often enjoy. Our program was defined more by what it was not than what it was: not literature, not journalism, not composition. De-spite this, the program grew, in part because we were able to invent an attractive curriculum, and our success introduced a new problem in that we were quickly understaffed: we had only three Professional and Technical Writing faculty in an English department of 50-odd full-time and part-time faculty. The demands on the three of us, all in new jobs, were sometimes intimidating. Actually, they were often overwhelming, as several authors in this volume have also experienced in their own schools. In front, we met the challenge of teaching new classes. At our back was an avalanche of paperwork. Struggling to keep moving forward, we found ourselves grasping for information and models. Like any academic in a new situation, we depended on our research skills first, and started reading.1 The

wpa-l.html) gave us valuable clues to how writing programs run on a day-to-day basis, though its focus is of course more on Freshman English. National conferences, especially ATTW (Association of Teachers of Technical Writing) and CPTSC (Council on Programs in Technical and Scientific Communica-tion), provided invaluable information about internships, key courses, recent theory—and at these conferences we found something the readings did not pro-vide: warm, anecdotal, human stories. I sought first-person narrative accounts that presented the PTW administrator’s logic and commitments, a constructive, sustained, intelligent set of discussions in relation to which we could shape our own history. To complete and understand our own program, we needed reflective stories that demonstrated and reflected on the process of making key, high-stakes decisions in the unfamiliar situation of running a professional writing program.

This narrative gap is what prompted my colleague Alex Reid and me to put out a call for papers that would, we hoped, assemble a community of narratives. Alex and I asked that PTW curriculum designers discuss how they composed and revised their PTW sites. We emphasized that we were looking for case studies in first person that revealed how designers made sense of and organized their particular location—in other words, how they historicized their work. Their stories would reveal the praxis of those in PTW programs work-ing simultaneously as both teachers and administrators, often from the margins of English, Engineering, Composition/Rhetoric, and on the line between the liberal arts and professional schools. The focus was not to be pedagogical, but architectural, with an emphasis on design problems.

In its final form, each of the essays was to examine the complexities of developing, sustaining, or simply proposing non-literature curricula, from entire programs to individual classes. The authors were generally new assistant professors when these essays were written, and their contributions reflect an acute sensitivity to the practical contexts within which they worked—the political, historical, and financial realities—as well as a sense of vitality, a sense that something untested and unique could emerge and succeed at their respective locations. In the best pragmatic tradition, these essays explain how to both picture and perform a task, in this case the task of developing communities and curricula in PTW, with the belief that other designers might benefit from their narratives.

com-ments. The results were strongly positive. Invested in the volume, peers generally commented critically and generously on one another’s work and appreciated the additional feedback they received while revising. Doing so also helped contribu-tors minimize overlap with other essays and gain a better picture of the volume as a whole. Conscious that many of our contributors are new to the field, we also invited several well-known figures in the field to read a grouping of essays and write “Post-Script” pieces based on their experience as program designers. Michael Dubinsky and Carol Lipson, experienced members of the field, graciously agreed to reflect on their careers in a way that gives context to the essays collected here.

Many of the articles collected here address what Robert Connors calls the “two-culture split” between the art and science of writing. That is, many of us struggle with practical answers to a question asked in various ways: are we to encourage insight or technique, liberal or vocational education, good citizens or good workers? This question is of course addressed by our theory, but has to be confronted also in even the most bureaucratic decisions about program require-ments, a semester’s course offerings, or even class sizes. This tension is also pres-ent every time a PTW faculty member sits down to write for publication. What balance does one provide for the reader between theoretical speculation and practical orientation? To put it another way, when we write for our colleagues in PTW, are we to provide interesting questions or interesting answers, the prob-lematics of a course of inquiry or the results of a course of action?

The chapters here provide both, taking a stance that bridges the two cultures and often explicitly addresses the tensions between them. Faculty un-der the gun to organize a program do not have the luxury of waiting for the conclusion of big-picture arguments about the history, nature, and status of the field; likewise, short-term best-guess decisions won’t sustain a program for very many semesters. Bringing together problem posing and problem solving is exactly what a program designer must do in order to begin and sustain his or her PTW program. This both/and thinking has direct application to the students’ learning. The PTW programs here refuse to choose between teaching students to reflect or teaching them the skills to “succeed” – with “success” a term that teachers tend to think about even more critically than their students.

the practical uses of knowledge, and eloquently turns Bacon’s insights to prag-matic advice for those facing the challenge of beginning and beyond. Turning then to the concerns at a specific site, collaboratively written “Starts, False Starts, and Getting Started: (Mis)understanding the Naming of a Professional Writing Minor” (Michael Knievel, Kelly Belanger, Colin Keeney, Julianne Couch, and Christine Stebbins) historicizes the process of naming their minor as it unfolds at their particular institution over several decades. By tracing the various impli-cations of their program’s name, they present a nuanced study of how various stakeholders choose to interpret—and misinterpret—their program. They pres-ent the process of naming as an inquiry, guided by a set of ethical and practical questions, into their identity and audience: “are these expectations [raised by the program’s name] at odds with each other? Which expectations can realistically be met given resources like faculty, funding, and goodwill?”

Two other articles in this first section discuss the process of designing in PTW in the face of serious challenges. As W. Gary Griswold puts it in “Compos-ing a Proposal for a Professional / Technical Writ“Compos-ing Program,” writ“Compos-ing the RFP (Request For Proposals or grant) for his program was a matter of “one week and five pages.” A case study of the under-represented (and over-feared) process of submitting a grant application, Griswold’s essay includes the original request for proposals and his response.

Completing this section, Brent Henze, Wendy Sharer and Janice Tovey’s piece on “Disciplinary Identities: Professional Writing, Rhetorical Studies, and Rethinking ‘English’” narrates their attempt to establish their proposed program in Rhetorical Studies and Professional Writing. The proposal itself was not well received. As they put it, they had inadvertently “thrown open the floodgates of disagreement about what a degree in ‘English’ means.” Their candid narrative examines with equanimity not only the choices they made, but also what they might have done differently, making it useful to program designers who simi-larly have to traverse disputed academic territory.

commu-nities. My own essay studies change in our undergraduate PTW program in a small New York college. I draw from genre theory, which argues that established types of written texts, though they may appear “frozen” or inert, are in fact pow-erful and dynamic forces shaping a community. Yet I began the program with a fairly naïve understanding of how the curriculum-as-genre, as a published docu-ment, would function. I describe learning to work with that curriculum as an “en-abling constraint,” one that pushed us to evolve while also restraining our growth. Change is also the theme of Jonathan Pitts’ “Composing and Revising the Pro-fessional Writing Program at Ohio Northern University: A Case Study. Charged with developing, sustaining, and creating coherence for his nascent major, Pitts shows how he deliberately planned for change without sacrificing coherence. His chapter includes the specific course offerings in his program and a vivid narrative of his experiences; it concludes with snapshot essays of several graduates from his program. In “Foundations for Teaching Technical Writing,” Sherry Burgus Little explains that the “design and development” of certificate programs “crystallizes” the pervasive and long-standing debate over the ends of education (283). They inevitably raise questions about what sorts of knowledge is essential for students to do their work as PTW professionals.

teach their students to make decisions situationally. They draw from Thomas Kent and post-colonialist theory to articulate their approach, one in which stu-dents learn to “participate in meaning-making and to recognize their role in meaning-making.”

The relationship between the humanities and the sciences is developed in Anne Parker’s reflective essay, “Introducing a Technical Communication Course Into a Canadian School of Engineering: A Case Study of the Professional and Academic Contexts.” There, she discusses developing a coherent and persua-sive model for teaching writing that draws on the habits of thought internalized by engineering. Holding a position on the faculty in the Engineering school, she presents working as an “insider” to effect change there. Her chapter tacitly traces strategies for dealing with a complex and gendered institutional context. She also gives a helpful and detailed discussion of how to keep various elements of her course vital and interactive: her team, the collaborative process, and product. Also concerned with Engineering, Michael Ballentine of Case Western Univer-sity shows us a successful approach for developing a writing pedagogy for engi-neers at his university. Dealing both with the graduate practicum course and the particular course for engineers that it prepares teachers for (over 350 students take it each year!), his “English and Engineering, Pedagogy and Politics” dis-cusses the political and practical negotiations necessary to embed successfully an engineering program into an English department.

The penultimate section of the book, “Futures,” is composed of two forward-thinking essays: “The Third Way: PTW and the Liberal Arts in the New Knowledge Society” by Anthony Di Renzo and “The Write Brain: Professional Writing in the Post-Knowledge Economy” by Alex Reid. Di Renzo’s essay ar-gues that PTW programs are a much-needed bridge for educational institutions torn between traditional liberal arts educational values and new pre-professional imperatives. PTW can provide an urgently needed social service by graduating rhetors with the know-how and eloquence to communicate between the vari-ous professions and disciplines, adept at responding to the demands of the new knowledge economy. Di Renzo’s essay is essentially promoting a new image of what an “educated person” might look like, free of an affected disdain for world-ly affairs or for intellectual play, and he argues persuasiveworld-ly that PTW programs are an apt site in which to begin education’s “third way.”

econ-omy” that has gone “offshore”; the consequent need for writers with rhetorical and critical skills; the rise of new Web 2.0 technologies which demand we teach students how to think “in” new media; the linked demands that Web 2.0 puts on us as faculty to teach and use such media to build knowledge webs and the like (Reid mentions wikis, blogs, and podcasts along with del.icio.us and flickr.com). His is not a repudiation of the humanistic, rhetorical tradition, but a reinscrip-tion of it (or “remediareinscrip-tion” as Jay David Bolter might have it), accomplished in new media. Reid gives us a conceptual and pragmatic sketch of how these sea changes can and will affect our working lives in PTW programs.

Finally, in “Post Scripts” we have reflections from two experienced pro-gram designers, Carol Lipson of Syracuse University and Jim Dubinsky of Virgin-ia Polytechnic Institute and State University. Dubinsky’s “A Techné for Citizens: Service-Learning, Conversation, and Community” reflects on the decade-long process of creating an undergraduate PTW curriculum that is both practical and reflective, rewarding not only for the student but also for the student’s communi-ty. He lays out the choices, both theoretical and practical, of designing a program that supports constructive civic action. The goal here is setting up students who can work with others on common problems, a harmony he likens to a form of reverence. Developing detailed and workable solutions to common problems is both a humanistic and technical commitment in Dubinsky’s program, articulated clearly in this helpful reflective essay. Whereas Jim Dubinsky’s essay addresses the process of getting up to interstate speed, Carol Lipson’s reflective essay “Models of Professional Writing/Technical Writing Administration: Reflections of a Serial Administrator at Syracuse University” traces her journey through several differ-ent incarnations of professional and technical writing, stretching nearly three decades, at Syracuse University in New York. Her experience clearly contrasts two paradigms. In the first, program leaders are segregated and pursue somewhat independent paths in a clearly defined hierarchy; in the second, the leaders of various initiatives are (ideally) peers who share a complex and intertwined set of partially overlapping agendas. Hierarchy is less explicit, if not absent. Lipson’s essay is candid about the complex institutional and administrative challenges that faced her as a PTW program designer, and gives a trajectory of her academic career which new PTW leaders will find useful and interesting.

notes

1 We found the following texts particularly helpful: Katherine Adams’ A

His-tory of Professional Writing Instruction in American Colleges: Years of Acceptance, Growth, and Doubt (Southern Methodist U.P., 1993); Teresa C. Kynell and Mi-chael Moran’s collection Three Keys to the Past: The History of Technical Commu-nication (ATTW, 1999); New Essays in Technical and Scientific Communication: Research, Theory, and Practice, edited by Paul Anderson, R. John Brockman, and Carolyn Miller (Baywood, 1983); Katherine Staples and Cezar Ornatowski’s

Foundations for Teaching Technical Communication: Theory, Practice, and Program Design (ATTW, 1998); Coming of Age: The Advanced Writing Curriculum, edited by Linda K. Shamoon, Rebecca Moore Howard, Sandra Jamieson and Robert A. Schwegler (Boynton/Cook Heinemann, 2000).

works cited

Bolter, Jay David, Writing Space: Computers, Hypertext, and the Remediation of Print, Second Edition. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2001.

Conners, Robert J. “Landmark Essay: The Rise of Technical Writing in America.” In Three Keys to the Past: The History of Technical Communication. Teresa C. Kynell and Michael G. Moran. Vol. 7 ATTW Contemporary Studies in Tech-nical Communication. Ablex: Stamford, CT., 1999. 173-195.

Little, Sherry Burges. “Designing Certificate Programs in Technical Writing.” In

Anthony Di Renzo

“I hold every man a debtor to his profession; from which as men of course do seek to receive countenance and profit, so ought they of duty to endeavor themselves, by way of amends, to be a help and an ornament thereunto. This is performed in some degree by the honest and liberal practice of a profession . . . ; but much more is performed if a man be able to visit and strengthen the roots and foundation of the science itself.”(546)

Sir Francis Bacon, “Preface,” Maxims of the Law (1596)

Perhaps Giambattista Vico was only half right when he proposed his cy-clical theory of history. Besides returning to the same key ideas, civilizations tend to suffer from the same nagging headaches.1 This is equally true, on a smaller

scale, of academic disciplines. They are defined less by their innovations than by their recurring problems and dilemmas.

This paradox certainly applies to professional and technical writing. At the dawn of the new millennium, our discipline faces the same vexing questions it confronted fifty years ago: Are we primarily practitioners and consultants or scholars and teachers? Do we train or educate students? Should we situate our practice in the classroom or the workplace? Is our subject closer to rhetoric and communications or the natural and social sciences?

These questions have become more urgent on college campuses, as pro-fessional and technical writing undergoes another turn on Vico’s spiral of his-tory. The traditional liberal arts paradigm of higher education is being displaced by a new emphasis on professional and technical training, and emerging PTW programs—especially at small liberal arts colleges—find themselves caught in the middle of the culture wars, simultaneously welcomed and resented, courted and resisted. During this time of risk and opportunity, of breakdown and break-through, what is our role and where is our place?

of professional and technical writing, this means again proposing that our prac-tice is essential to the humanities. However, I am not simply repeating Carolyn Miller’s ideas, already twenty years old, for a more humanistic professional and technical writing practice, much less updating Frank Aydelotte’s humanities-centered engineering curricula from the early twentieth century. Instead, taking a cue from Beth Tebeaux’s scholarship, I want to suggest returning to the instruc-tional roots of our discipline by re-examining the educational ideas of one of its founders, Sir Francis Bacon (1561-1626).

As a scholar and a rhetorician, Francis Bacon straddled three worlds: the literary and philosophical, the administrative and professional, and the scientific and technical—-the same mixed audience facing any proponent of professional/ technical writing in today’s academy. But Bacon is our contemporary in more important ways. Unlike most Renaissance humanists, he located the New Learn-ing (what we now call the humanities) within the related contexts of scientific discovery and invention and professional training and development. Conse-quently, his proposed educational reforms challenged both the Scholastics, who adhered to the cloistered ideal of the medieval university, and the Ciceronians, who slavishly imitated models of classical rhetoric for imaginary audiences in make-believe situations.

In contrast, Bacon—-a believer in public service and the via activa— wanted to draw knowledge from and apply knowledge to the natural and social world; and his great treatise, The Advancement of Learning (1605), later revised and expanded as De Augmentis Scientiarum (1623), is a gigantic curricular blue-print to achieve that end. True education, Bacon argues, should:

• Enhance the professions to make them more ethical, more historically conscious, and more civic-minded.

• Emphasize the material and political conditions of knowledge for the sake of concrete, pragmatic application in the real world.

• Stress the rhetorical underpinnings of organizational and disciplinary discourse, both oral and written.

• Study the media and technologies of science and communications to better government, to reform public and private institutions, and to im-prove quality of life.

To show how, let me gather some of Bacon’s educational ideas from his various writings and apply them to the five stages of undergraduate program development: planning, implementation, mission, design and development, staff-ing and administration. Following Bacon’s example, I will use aphorisms, since such maxims, he said, force a writer to distill abstract information into concrete principles and to resist the kind of systematic, a priori thinking that shuts down inquiry before one examines the facts.

aphorisms for building ptw programs

in the humanities and sciences

Planning

“He that builds a fair house upon an ill seat, committeth himself to prison.”(193)

Sir Francis Bacon, “Of Building” from The Essays (1625)

• To minimize the possibility of failure, construct your program on a solid

foundation of research. Just because you build it, doesn’t mean they will

come, pace Kevin Costner. Before you draft a blueprint, do some basic marketing. If you already offer one or two basic PTW courses, study their enrollment patterns going back five years minimum and note how these classes fulfill the requirements of outside majors. If you start from scratch, interview departments in the natural and social sciences and the profes-sional schools, determine their academic and profesprofes-sional writing needs and curricular restrictions, and design fitting and responsive courses. These steps will prevent your field of dreams from becoming a bog of screams.

“There are in nature certain fountains of justice, whence all civil laws are derived but as streams; and like as waters do take tinctures and tastes from the soils through which they run, so do civil laws vary according to the regions and governments where they are planted, though they proceed from the same fountain.” (287)

Sir Francis Bacon, Book Two, The Advancement of Learning (1605)

• Study the PTW programs of comparable schools, map and analyze

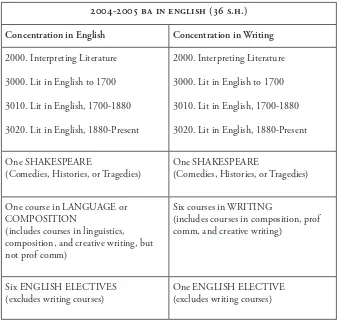

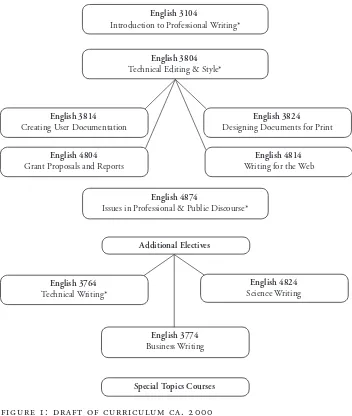

program. Use induction to discover the fundamental principles under-lying most PTW curricula. Generally, most have five stages, each with specific developmental goals and their corresponding courses. For illus-tration, the following table feature courses from the proposed PTW con-centration within Ithaca College’s general BA in Writing:

stage goal courses

1. Initiation Use first-year college writing to prepare for professional writing.

WRTG-16300 Writing Seminar: Business

WRTG-16400 Writing Seminar: Science

2. Orientation Teach the building blocks of professional and technical writ-ing at the sophomore level.

WRTG-21100 Writing for the Workplace

WRTG-21300 Technical Writing 3. Application Develop and fine-tune skills

through practice and specialization at the lower junior level.

WRTG-31100 Writing for the Professions WRTG-31300

Advanced Technical Writing WRTG-31400

Science Writing WRTG-31700 Proposals, Grants, and Reports

4. Reflection Frame discipline and practice through history, theory, and rhetoric in upper junior- and senior-level seminars.

WRTG-3600 Composition Theory

WRTG-41500 Senior Seminar (PTW) 5. Action Consult for or intern at an

Significantly, these stages correspond to Bacon’s four divisions of logic and rhetoric in The Advancement of Learning: (1) inquiry and invention, (2) judgment, (3) memory, (4) delivery.

“Studies serve for delight, for ornament, and for ability. Their chief use for delight, is in privateness and retiring; for ornament is in discourses; and for ability, is in the judgment and disposition of business.” (209)

Sir Francis Bacon, “Of Studies” from The Essays (1625)

• Be comprehensive. A hearty education, Bacon believed, should feed the

three faculties of the human mind: reason, which sees patterns in the world, analyzes data, and posits general principles; memory, the mental storehouse of experienced events and material facts; and imagination, which channels and articulates the passions and makes intuitive leaps. Even professional and technical training, therefore, should include phi-losophy, history, and literature.

Implementation

“The ripeness or unripeness of the occasion . . . must ever be well weighed: and generally it is good to commit the beginnings of all great actions to Argus with his hundred eyes, and the ends to Briareus with his hundred hands, first to watch, then to speed.” (125)

Sir Francis Bacon, “Of Delays” from The Essays (1625)

• Although curricular planning should be slow and painstaking,

implemen-tation should be relatively swift. Once you have proposed your program,

you are obliged to deliver it. First, create a beachhead to cover your service component, to stake out future development, and to raise expectations. Begin with the nucleus of your projected curriculum, the core courses serving both your majors and outside students, then phase in more spe-cialized classes. Ideally, curricular sequencing should unfold like a paper flower in water.

“As the births of living creatures at first are ill-shapen, so are all innovations, which are the births of time.” (132)

• Don’t worry, however, if your program assumes a different shape and

direction than your original proposal. Provided these changes are

re-sponses to student and institutional need, they indicate evolution not devolution. Being audience-centered and market-oriented, PTW cur-ricula should be flexible and adaptive.

Program Mission

“Expert men can execute, and perhaps judge of particulars, one by one; but the general counsels, and the plots and marshalling of affairs come best from those that are learned.” (209)

Sir Francis Bacon, “Of Studies” from The Essays (1625)

If your program is housed in the Humanities and Sciences, it should reflect

lib-eral arts values. Unlike PTW programs at polytechnics or research universities,

those at small liberal arts colleges should be dedicated less to technical specializa-tion than to what Chase CEO Willard Butcher calls “applied humanities,” using the liberal arts to frame and to inform students’ future careers (426). A broad base of disciplines and a commitment to civics, Peter Drucker insists, are the best foundation for young “knowledge workers” (5).

“They who have hitherto written upon laws were either philosophers or lawyers. The philosophers advance many things that appear beautiful in discourse but lie out of the road of use, whilst the lawyers, being bound and subject to the decrees of the laws pre-vailing in their several countries, whether Roman or pontifical, have not their judgment free, but write in fetters. But this task properly belongs to statesmen, who best under-stand civil society, the good of the people, natural equity, the custom of the nations, and the different forms of states; whence they are able to judge laws by principles and precepts as well as natural justice and politics.” (282)

Sir Francis Bacon, Book 8, Ch. 3, De Augumentis (1623)

• Always think socially and institutionally, not only in running your

pro-gram but in teaching your students. Professional and technical writing

pedagogy, and curricular design should all reflect that reality. This can be as simple as integrating community service learning into first-year academic writing or as complicated as teaching the classical ideal of the citizen-orator to juniors and seniors.

“Exercises are to be framed to the life; that is to say, to work ability in that kind whereof man in the course of action should have the most use.” (118)

Sir Francis Bacon, “A Letter and Discourse to Sir Henry Savile” (1604)

• Whatever its ideals, your program must provide students with marketable,

transferable skills. Without this “real world” application, your curriculum

will be useless.

Curricular Design and Development

“The marshalling and sequel of sciences and practices: Logic and Rhetoric should be used and to be read after Poesy, History, and Philosophy. First exercise to do things well and clean; after promptly and readily.” (119)

Sir Francis Bacon, “A Letter and Discourse to Sir Henry Savile” (1604)

• Provide your students with a clear curricular framework and a coherent

disciplinary narrative from the very beginning. Such context will prevent

lower-level courses from becoming too generic and upper-level courses from becoming too specialized.

“Reading maketh a full man; conference a ready man; and writing an exact man” (209) Sir Francis Bacon, “Of Studies” from The Essays (1625)

• Students should progress from research and analysis, to dialogue and

de-bate, to execution and evaluation. This curricular staging ultimately

“The mechanical arts, having in them some breath of life, are continually growing and becoming more perfect. As originally invented, they are commonly rude, clumsy, and shapeless; afterwards, they acquire new powers and more commodious arrangements and constructions . . . [till] they arrive at the ultimate perfection of which they are capable. Philosophy and the intellectuals sciences, on the contrary, stand like statues, worshiped and celebrated, but not moved or advanced.” (8-9)

Sir Francis Bacon, The Great Instauration (1620)

• Stress tools, not rules. Since professional and technical writing is

practice-driven and context-specific, shun all abstractions. Technology, document design, media dynamics, and institutional constraints should determine your program’s curricular philosophy, not the other way around. “Pass from Vulcan to Minerva,” Bacon advised (141). Move from praxis to the-ory. Never place theory before praxis. That, Bacon would say, is like build-ing a mansion from the roof down.

“Of the choice (because you mean the study of humanity), I think history the most, and I had almost said of only use.” (105)

Sir Francis Bacon, “Advice to Fulke Greville” (1596)

• Historicize your subject. That means more than teaching about the

de-velopment of professional and technical writing. It means tracing the dis-cipline’s roots back to classical rhetoric, studying the growth of various social institutions, and reviewing the evolution of different media and technologies. History provides your students with a formative narrative and connects your program to the humanities.

“Histories make men wise, poets witty, the mathematics subtle, natural philosophy deep, moral [ethics] grave, logic and rhetoric able to content.” (210)

Sir Francis Bacon, “Of Studies” from The Essays (1625)

• Use case studies to train your students. Just as young lawyers study past

stud-ies are the ideal forum for argumentation and ethical speculation, where students can practice institutional and technological advocacy before multiple audiences.

“There is in human nature generally more of the fool than of the wise; and therefore those faculties by which the foolish part of men’s minds is taken are most potent.” (94)

Sir Francis Bacon, “Of Boldness” from The Essays (1625)

• Be honest about the politics and absurdity of institutional writing. Most

textbooks skirt this issue by presenting straightforward models and forms and ideal collaborative situations. Your program must address the rever-sals, rivalries, and irrational thinking that characterize most writing proj-ects and suggest effective countermeasures. At the very least, coping strate-gies. If you send lambs to the corporate sheering floor, you are guilty of fleecing yourself.

“For it is a rule in the doctrine of delivery, that every science which comports not with anticipations and prejudices must seek the assistance of similes and allusions.” (175)

Sir Francis Bacon, Book 6, Ch. 2, De Augmentis (1623)

• Stress the finer points of style and persuasion. Arrangement, formatting,

even striking visuals are not enough to create a winning presentation. Sometimes the telling phrase, the striking metaphor, the provocative anal-ogy carry the day.

“It is a trivial grammar-school text, but yet worthy a wise man’s consideration. Question was asked of Demosthenes. What was the chief part of an orator? He answered, Action. [Delivery.] What next? Action. What next again? Action.” (94)

Sir Francis Bacon, “Of Boldness” from The Essays (1625)

• Aim for results. “Rhetoric,” Bacon claimed, “applies Reason to the

feedback, therefore, from potential employers in industry and technology, as well as college administrators, promoters, and admissions officers. And whether or not Bacon actually wrote Shakespeare’s plays, make this line from Act 3, Scene 2 of Coriolanus your motto:“In such business action is eloquence.” (79).

Staffing and Administration

“They that have the best eyes are not always the best lapidaries [jewelers]; and according to the proverb the greatest clerks are not always the wisest men.” (105)

Sir Francis Bacon, “Advice to Fulke Greville” (1596)

• Staff courses according to experience and expertise, not seniority and

ad-vanced degrees. This concept seems heretical but makes the best sense and

does the most justice to both students and subjects. A full- or part-time instructor who worked for five years as a technical and promotional writer in a county hospital is better qualified to teach medical writing than an assistant or associate professor who graduated from RPI. Scholars can sup-ply practitioners with outside readings, but practitioners cannot supsup-ply scholars with inside knowledge.

“Surely ever medicine is an innovation, and he that will not apply new remedies must expect new evils. For time is the greatest innovator, and if time of course alter things to the worse, and wisdom and counsel not alter them to the better, what shall be the end?” (132)

Sir Francis Bacon, “Of Innovations” from The Essays (1625)

• Anticipate change and plan for contingencies. To keep your program open

and flexible, be prepared to alter its focus and sequencing and to amend, combine, or jettison courses in response to market need and student de-mand. On the subject of adaptability, Bacon loved to quote Machiavelli: “If you can change your nature with times and circumstances, your for-tune will not change” (68).

direction than an indefinite, as ashes are more generative than dust.” (135)

Sir Francis Bacon, “Of Dispatch” from The Essays (1625)

• Compost your failures to fertilize future projects. Recycle rejected courses

as special seminars. Transplant background material from an aborted pro-posal into a program report. Boilerplate unread course descriptions when submitting a catalog copy. Waste nothing.

“Just as some putrid substances like musk or civet yield the best scent, so base and sordid details sometimes provide excellent light and information.” (122)

Sir Francis Bacon, Book One, Aphorism 120, The New Organon (1620)

• Even when things stink, welcome confusion and disappointment. If you

can bear the temporary din of frustration, your program’s elements even-tually will harmonize. In science as in music, Bacon said, dissonance is necessary to fine-tune an instrument.

A Baconian approach to curricular design and implementation offers three dis-tinct advantages to emerging PTW programs at small liberal arts colleges. First, Bacon’s educational principles and practices make a convincing apologia for most English departments and writing programs. The Lord Chancellor is the best lawyer to plead your case because he appeals to so many different audiences. Traditional humanists will be pleased to see how Bacon’s ideas about professional and technical writing fit historically within their own disciplines. Theorists and New Historians will respect his materialism and praxis, while department chairs and program directors will appreciate his shrewdness and practicality.

using professional and technical training to bridge the gap between the quad and the commons.

Last, Bacon’s radical rethinking of the sciences and the professions can inspire programs to re-imagine their pedagogy while providing the necessary theoretical scaffolding to paint the big picture. The loam of historical research can provide rich soil to grow good programs. Bacon, an avid gardener and land-scaper, makes this analogy in Book 6, Chapter 2 of De Augmentis Scientiarum:

For it is in arts as in trees—if a tree were to be used, no matter for the root, but if it were to be transplanted, it is a surer way to take the root than the slips. So the transplantation now practiced of the sciences makes a great show, as it were, of branches, that without the roots may indeed be fit for the build-er, but not for the planter. He who would promote the growth of the sciences should be less solicitous about the trunk or body of them and lend his care to preserve the roots, and draw them out with some little earth about them. (172)

However, we scholars and teachers of PTW should look back less to legitimize our practice for the sake of our critics than to look around and look ahead for the sake of our students. Bacon was no antiquarian, after all. Although he venerated history, he believed people should use the past primarily to secure present provisions for a future journey. The frontispiece of the 1620 edition of

The Great Instauration shows a billowing galleon returning through the Pillars of Hercules from its voyage on unknown seas. If the latest turn in the academy has made our discipline more valuable and necessary, if it is now our turn to define the rules of the game, if this collective return to our intellectual past is to be more than academic, then we must recapture our sense of wonder with our sense of mission. In T. S. Eliot’s words:

We shall not cease from exploration And the end of all our exploring Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time. (59)

works cited

Bacon, Francis. Advancement of Learning and Novum Organum.Revised Ed. Ed. and Trans. James Edward Creighton. New York: Colonial Press, 1899.

Bacon, Francis. “Advice to Fulke Greville.” The Oxford Authors: Francis Bacon.

Ed. Brian Vickers. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996. 102-106. Bacon, Francis. The Essays. Ed. John Pitcher. New York: Penguin, 1985.

Bacon, Francis. The Great Instauration and New Atlantis. Ed. J. Weinberger. Ar-lington Heights, IL: Harland Davidson, 1980.

Bacon, Francis. “A Letter and Discourse to Sir Henry Savile.” The Oxford Authors: Francis Bacon. Ed. Brian Vickers. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996. 114-119.

Bacon, Francis. “Maxims of the Law.” The Works of Lord Bacon. Vol. 1. Ed. James Spedding. London: Henry G. Bohn, 1854. 546-590.

Bacon, Francis. Novum Organum. Ed. and Trans. Peter Urbach and John Gibson. Chicago: Open Court Publishing, 1994.

Butcher, W. F. “Applied Humanities: They Will Pay You for the Other Five Per-cent.” Vital Speeches of the Day (1 August, 1990): 623-25.

Crowther, J. G. Francis Bacon: The First Statesman of Science. London: Cresset Press, 1960.

Drucker, P. F. The Effective Executive. Harper, 1966. Eliot, T. S. The Four Quartets. New York: Harcourt, 1971.

Machiavelli, N. The Prince. 2nd Ed. Ed. and Trans. Robert M. Adams. New York:

Norton, 1992. Shakespeare, William. Coriolanus. Ed. Jonathan Crewe New York: Penguin, 1999.

Writing Minor

Michael Knievel Kelly Belanger Colin Keeney Julianne Couch Christine Stebbins

introduction: naming as rhetorical

disciplinary/programmatic action

After several years of planning and development, the University of Wyo-ming Department of English now offers an undergraduate minor in professional writing. In thinking about our program, we have become increasingly conscious of the ways in which the name of this program, simply the “professional writing minor,” functions within our institutional context, a relatively small (approxi-mately ten thousandundergraduates) state university and a traditional English department offering both undergraduate and graduate (MA and MFA) degrees. All programs have names, but most, including our own, are not particu-larly noteworthy. Save for some notable exceptions in recent years (for instance, Central Florida’s doctoral program in “Texts and Technology”), most writing programs that identify their mission as distinct from composition or creative writing, regardless of size or status, rely heavily on a familiar word bank for their program titles: “rhetoric,” “communication,” “writing,” “technical,” and “professional.” But while this uniformity has helped fashion a quasi-recognizable disciplinary identity in “nonacademic” writing and communication, it also de-flects attention from the significance of signification. Awash in the hundreds of questions and issues that come with envisioning a program, teachers and administrators may move uncritically past this vital step in the development pro-cess, reaching for terms in the word bank without sufficiently considering their implications and the multiple lenses through which those words will be read.

acknowl-edges that the process of naming is complex and fraught with competing mo-tives, asking, “Is the naming of programs a determinist enterprise that takes on a life of its own? Or are we being creative in our endeavor to associate thing to thing, spiritual fact with embodied form?” Johnson recognizes the need to let local factors guide naming but cautions against promising more (or less) than can be delivered: “…should we think twice about unnaming ourselves in the process of trying to embrace too much?” Generally speaking, the implications of program naming have been inferred from broader conversations about con-nections between program development and institutional politics (Cunningham and Harris; Hayhoe, et al; Latterell; MacNealy and Heaton; Mendelson; Rentz; Sides; Sullivan and Porter) and intersections between disciplinarity and profes-sionalism (Faber, Savage).

With their focus on larger programmatic and disciplinary issues, many of the aforementioned authors typically address program naming in tangential fashion, although some acknowledge what might be at stake when naming a program or, in some cases, an entire field of inquiry. MacNealy and Heaton sug-gest that the name “Professional and Technical Communication” may best rep-resent the field’s scope and hope for acceptance: “…if we want to enhance our image among those outside the field, the term ‘professional’ might be a better choice than ‘technical’ because it is more inclusive and it sounds less mechanis-tic.” (55). Dayton and Bernhardt’s 2003 survey of ATTW (Association of Teach-ers of Technical Writing) membTeach-ers asked respondents what the field should be called, offering a variety of fixed-response possibilities from which to choose. The top three choices included: “Technical Communication” (39%); “Profes-sional Communication” (32%); and “Profes“Profes-sional Writing” (10%). However, in an open-ended follow-up question, respondents offered still more alternatives and noted the importance of having a name that communicated clearly to out-siders but that acknowledges specific contexts (29-30).

the present challenges of “getting started.” In doing so, we map the vast array of connected and disconnected questions, concerns, and values that come into play when a program of this kind is developed and named. We believe that the archaeology of a program name can be uniquely generative as a site of research, a catalyst for institutional critique, and, consequently, a means of reclaiming a name and program. And while we acknowledge the power of more abstract con-versation about naming, we assert that a local focus might yield more granular insight into this highly contextualized process, insight that has the potential to enrich—and complicate—our sense of the complexity of both naming and pro-gram development.

finding our own voices: windows to past,

present

In approaching the question of program naming, we prioritized the two broad currents identified above: 1) historically situated development and 2) program execution. To that end, we crafted a quasi-ethnographic approach to researching our name and the issues and events that both precipitated and emerged from it. In short, we compiled information and perspectives through examination of:

• our own personal narratives written from the perspective of writing fac-ulty deeply invested in planning, teaching in, and overseeing the program

• semi-structured interviews with past and present members of the English Department (faculty, students, administrators), many of whom played an integral role in the development and launch of the program

• files and archives containing a variety of documents pertaining to the mi-nor (e.g., course approval forms, meeting minutes, related grant propos-als, email correspondence regarding the curriculum, computer classroom, etc.).

As writer-researchers, we represent both a historical cross-section of the writing history at UW and the range of responsibilities for program execution at our university. All of us are situated in the Department of English. Some of us work as academic professional lecturers (APLs), which are extended-term teach-ing positions (six-year renewable appointment and opportunity for promotion). Others are assistant and associate professors, respectively, in writing-related fields.1 Some of us have a significant measure of professional writing

focused more specifically on writing in academic contexts. All of us have taught a variety of courses in our department’s professional writing minor, served on a range of related committees, and worked together on various writing-related initiatives in our department or on campus.

At UW, we have constructed a minor designed to capitalize on the range of experience and expertise that we, as teachers, bring to the program. At present, the professional writing minor consists of eighteen credit hours and em-phasizes flexibility. Students are required to take two three-credit core courses:

ENGL 2035 Writing for Public Forums

ENGL 4000 21st Century Issues in Professional Writing

In addition, they choose two of the following three-credit courses:

ENGL 4010 Technical Writing in the Professions ENGL 4020 Editing for Publication

ENGL 4050 Writer’s Workshop: Magazine Writing ENGL 4970 Professional Writing Internship

Finally, students select two writing-intensive elective courses, typically related to their major course of study and connected to their career objectives.

chronology: constructing our past,

considering our present

In the sections that follow, a series of narratives describes the myriad conditions, values, and beliefs that gave rise to a program named, somewhat serendipitously, the “professional writing minor” and demonstrates some of the consequences of this naming choice for various stakeholders within our institu-tional context.

Starts (1986-1993)

uni-versity as a whole.” Another colleague recalls their development of the Wyoming Writing Project, the Wyoming Conference, and the Writing Center during the seventies and early eighties. Their collaborative essay, “Liberatory Writing Cen-ters” (1984), both defined and helped establish university writing centers na-tionwide, and Tilly’s Writing Is Critical Action (1989) is still commonly cited in composition scholarship. In essence, the Warnocks were the first real representa-tives of composition and rhetoric—as we would define that discipline today—at UW, and were strident advocates for its acceptance.

The late 1970s also begat a pivotal course on campus: Scientific and Technical Writing (ENGL 4010), the name of which, interestingly, would be changed to “Technical Writing in the Professions” in 2001. As shall be seen, tracking 4010’s permutations constitutes a primary, connective thread through our narrative. If nothing else, one colleague notes, “I’m sure that (4010) proved the existence of a clientele” for an upper-level writing course beyond that era’s requirement for only two semesters of “freshman” composition. Twenty years later, meeting the needs of that “clientele” would, in part, spawn the professional writing minor.

On the other hand, the advent of Scientific and Technical Writing al-most immediately raised two counter-considerations. The course was developed within the English department from a direct request by the College of Engi-neering – to enhance their students’ writing skills – but the College of Busi-ness quickly came onboard and began requiring it of their majors. For obvious reasons, the course was immediately consigned to the “service” bin, with the result that very few English faculty members cared to teach it. This attitude was administratively underlined when the Dean of Arts and Sciences subsequently refused to accept work in this area for tenure or promotion deliberations. Be-cause of this, and beBe-cause the course was too advanced for graduate assistants to teach, 4010 was progressively shunted to temporary lecturers.

And then there was that name—“Scientific and Technical Writing.” Clearly, when marketing or accounting majors began queuing up for the course, it lost any technical edge or scientific facet it might have contained. Indeed, one faculty member who developed the original version of 4010 thought to himself, at that time, “This really isn’t a scientific and technical writing course … we ought to call it ‘professional writing.’”

union’s grievance against management. However, by concentrating on people— on those who teach and develop writing—the Resolution served as a cornerstone for comprehensive writing curricula across the country. Indeed, the Resolution helped make it possible to develop writing curricula by emphasizing improved working conditions, such as compensation and workload, for those who would develop and execute such programs. But as we now know, few of these achieve-ments came smoothly or without some sort of price, and writing development at UW was certainly no exception.

Without fanfare – and with virtually no attention from other depart-ment members – our assistant chair began a “cohort group” for 4010 instructors in 1987. The group’s initial function was twofold: to supply mutual support for those teaching this demanding course, and to improve consistency without limiting academic freedom. The cohort group’s overall success was confirmed by one colleague who joined the department a few years later: “The group… seemed to feel a justifiable sense of ownership of the course and pride in its high quality and had reached a (general) group consensus on standards and assign-ments.” Certainly these were no small accomplishments, but they frequently played second fiddle to larger topics within the group. For instance, for several years, the group maintained a running discussion of gender issues in the techni-cal writing classroom, such as why male instructors were often evaluated as being “tough but fair,” whereas our female colleagues were raked for being “too tough,” “unfair,” or “a bitch.” (Combined with being stuck in term-limited positions, teaching a devalued course, and working in an “unscholarly” discipline, this gender bias formed what one colleague dubbed a “quadruple whammy.”) Under the circumstances of the times, it was invisible work performed by an invisible group, but it “… solidified and brought together the APLs (lecturers) in the department who were working with 4010.”

More visible by far were the events of 1990-93 and the English depart-ment’s response to them. First, UW’s administration mandated development of a new University Studies Program (USP), and central to that plan was replacing the previously mentioned two-semester “frosh comp” requirement with writ-ing courses labeled WA (first-year), WB (sophomore/junior), and WC (senior/ capstone). After review and approval, any college, department, or program on campus could teach any of these multi-tiered writing courses. The English de-partment reacted by appointing a six-person Writing Committee and charged this group with qualifying, quantifying, and separating these different levels of written discourse.

the eyes of the university’s administration, at least, those who taught writing were suddenly elevated from second-class citizenship to being significant con-tributors. And while the Writing Committee’s official function was to determine what constituted WA, WB or WC writing only within this department, it was tacitly understood that our delineations ultimately would apply to all writing courses, campus-wide. One lecturer remembers, “We were considered ‘the pros’ when it came to writing, so we got to call the shots.” Therefore, through the act of defining, this small in-house group named writing at UW.

This section would be incomplete without mentioning a Department of English retreat held in the fall of 1993. This gathering produced the de-partmental decision to formulate a “writing program,” that focused on neither “academic” nor “creative” writing at its core and sparked the need for someone to develop and direct such a program. However, individual recollections of this event are varied. One participant remains convinced that this portion of the retreat’s agenda was orchestrated to the point of crafty manipulation (“… it was a nifty bit of stacking the deck”); two others would contend all of this “just hap-pened” with little to no forethought or planning; and at least one department member can recall precisely who catered the food – and nothing else. One might suspect that the clarity and tone of these memories depended on the individual’s proximity to writing and writing instruction, but that could be mere conjecture.

False Starts (1993-1998)

nearly all of whom were English department APLs, these WAC-focused years were busy. In addition to full course loads, most APLs were assigned to the Writ-ing Center for five hours a week to work with clients and perform extensive out-reach for the Center, often preparing and presenting numerous workshops and seminars each week to help guide the campus-wide implementation of WAC. In the end, however, APLs could claim little if any meaningful professional credit for this tremendous outlay of individual and collaborative time and effort; it was just expected. Ironically, but politically foreseeable, it was the relatively invisible, relatively powerless temporary writing instructors who were charged with help-ing to improve the level of writhelp-ing integration in the entire university.

When some WAC courses around campus were later dropped, depart-ments typically directed students to 4010 to meet graduation requiredepart-ments, and so course enrollments continued to burgeon. However, some English depart-ment faculty felt that this type of writing was too far outside the domain of traditional English Studies and a threat to the very identity of our department. In consequence, English majors were not allowed to take the technical writing course for credit in the major. One senior lecturer says, “The problem we’ve always had with the perception of 4010 is that people always saw it as a service class for people outside of the English department and of course, as you know, it wasn’t allowed to be counted for an English major… people saw it as being like fill-in-the-blank kind of writing and I guess they didn’t see it as “real writing” … they just saw it as a real sort of pedestrian writing.” Another faculty member notes, “…the course…has always had this marginal relationship to the depart-ment. I mean, it was so striking and odd to me that for a while that course didn’t count toward the major …that was one 4000-level course that ‘non-professors’ …could teach.”2

In the ensuing two-year gap between the departure of one rhet/comp professor and the hiring of another, there seemed to be growing consensus re-garding the need for a “tenure track presence… to give a new writing program legitimacy.” Throughout this tough time, the technical writing cohort hung to-gether, trying to keep spirits up, lives intact, and eyes looking forward as the pro-fessionals that members knew they were. The cohort kept abreast of new trends, technology developments, and the national debates about the many aspects of the discipline. The one thing members did not formally discuss, however, was a professional writing minor. Although the 4010 cohort group would later play a central role in constructing the minor, at this juncture, it was just “too pie in the sky” to have any real hope it might happen.

Getting Started (1998-2000)

However, in the October 1997 MLA Job Information List the UW Eng-lish Department publicly indicated its intention to develop a writing minor and sought a senior faculty member to serve as a “point person” for the new minor and the first-year writing program. The department’s intention to hire at the senior level indicated an awareness—born during the years of “starts” and “false starts”— of the political complications inherent in coordinating or developing writing programs within a department holding a traditional literature view of the English Department’s curricular geography (Sullivan and Porter 393). One senior literature professor, to whom a former department chair attributes the idea of developing a writing minor, also points to a generational shift in the department in which a cohort of faculty “came out [of graduate school] with a much different notion of what “English” meant for our students, and not just students who were going to show up in our English classes because of their great love of literature, but students who were actually living and working in English.” She explained in an interview that “for us, thinking about writing as a part of a student’s education wasn’t an add-on. We saw the integration.” She believes this integrative vision among some faculty members paved the way for the 1998 hir-ing of an Associate Professor of Composition and Rhetoric and for a significant store of goodwill among the literature faculty toward a possible new writing minor.

background and interest in collaborative program development that proved a relatively comfortable fit with a department whose literature and creative writ-ing faculty had only a nascent sense of composition, rhetoric, or professional/ technical writing as fields within English Studies, each with their own bodies of scholarship and intellectual traditions. Along with research interests in com-position, computers and writing, business communication, and literature, she also brought entrepreneurial experience from having developed a new writing program for unionized steelworkers in Ohio and, with business partners, a cof-feehouse/café. This generalist background to some extent mirrored the generalist strengths of the department’s richly experienced APLs. Even so, early on, some members of the 4010 cohort greeted the new “point person” with skepticism that made it difficult for the team and their appointed leader to see their com-mon interests in advancing the status of writing in the department. One senior APL proved a valuable intermediary, “translating” between other APLs and thus helping to clarify their overlapping goals. As the longtime leader of the cohort group put it, “I think we had the perception that something like [a writing mi-nor] couldn’t happen.”

Although we can’t identify the particular meeting or discussion during which we settled on the term “professional” to characterize the writing minor— indeed it seemed a name simply “in the air” that we gravitated toward—notes from a June 2000 Wyoming Conference on English writing workshops suggest that some members of the technical writing cohort group pondered early on the implications of the term “professional.” One note taker mused, “Professional writing is an umbrella term. Business writing/com, tech. writing, and scientific writing are all subsumed under the larger term ‘Professional Writing.’ Which of these terms work best for what we want to teach?” A senior APL explains, “We weren’t trying really to narrow our program because first of all we’re all kind of generalists.… And I think that we felt comfortable with a more general name, or general title, under which we could see ourselves as instructors. Professional writing minor seemed just right.”

Settling on the term “professional,” with its ever-expanding connota-tions, not only reflected the generalist background of faculty teaching in the minor, it also responded to a range of desires, anxieties, and assumptions on the part of the English Department and its faculty. While some, even many, faculty members might have welcomed more sustained discussion at least behind the scenes, the department appeared willing, even eager, to approve the minor with-out further discussion, perhaps for practical reasons of its own. Perhaps anxious not to go the way of impoverished, diminished humanities departments with no service course responsibilities, some faculty saw the new “professional” writing minor as a commodity to package and sell, a product more practical and market-able than its literature or creative writing courses. One colleague described using the term professional as a “packaging maneuver.” And in the early 1970s, teach-ing technical writteach-ing courses had seemed a wise career move for one literature professor we interviewed, who feared for his career in light of declining English majors. Another literature professor interviewed denied that his support for the minor had anything to do with concern about the viability of the English De-partment or major. Instead, he saw the minor as a way to address the perceived illiteracy of engineers and agronomists while potentially draw