Association of Parental Role Overload and Youth Transition Readiness among Parents of Youth with Chronic Illness

By

Laura Hart

A Master’s Paper submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Public Health in

the Public Health Leadership Program.

Chapel Hill

2017

_________________________________________________ Advisor:

_________________________________________________ Date

_________________________________________________ Second Reader:

Table of Contents

Abstract of Masters Paper……… 2

Systematic Review Abstract………... 4

Systematic Review……….. 6

References……… 15

Figures……… 17

Tables……….. 18

Original Manuscript Abstract………. 25

Original Manuscript……….. 27

References………... 36

Tables………. 38

Appendix A……….. 42

Appendix B……….. 44

Abstract

As more and more youth with chronic illness survive into adulthood, more efforts are underway to help ensure them a safe and smooth health care transition (HCT) from pediatric to adult-oriented care. These efforts include programs and materials aimed increasing HCT readiness among youth, which is the ability of youth to understand and manage their medical needs. The family-centered paradigm of pediatrics means that parents play a key role in their child’s medical care, and thus have an important role in HCT as well.

The purpose of this master’s paper is to understand the parental experience of their child’s HCT and how that experience affects their child’s HCT readiness. The paper begins with a systematic review of qualitative interviews and focus groups of parents’ perspectives of their child’s HCT. Overall, parents reported many concerns about HCT, including fears of leaving old providers, finding new providers that were trustworthy, maintaining their child’s safety during the process, and worries about letting go of medical management of their child’s illness.

The Experience of Parents During their Child’s Transition

to Adult-Oriented Care: A Systematic Review

Abstract:

Background: Parents of youth with chronic illness play a critical role in maintaining the health and well-being of their children. As youth with chronic illness approach adulthood, they experience many transitions, including a healthcare transition (HCT) from pediatric to adult-oriented care. Because parents play such an important role prior to HCT, it is not surprising that theoretical models of HCT highlight the importance of parents in the HCT process. Thus, the perspectives of parents are critical to understanding HCT.

Objectives: To describe the perspectives of parents regarding their child’s HCT. Search Strategy: We searched the PubMed database from January 2012 to January 2017.

Selection Criteria: Included articles needed to describe results of qualitative interviews or focus groups that included parents of youth with chronic illness as participants. Due to health systems differences that might affect the parent experience of HCT, studies had to be conducted with participants from the United States.

scored using the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) guidelines.

Results: The search resulted in 286 unique results, of which 111 underwent full-text review and 9 were deemed to meet all inclusion criteria. With the 9 studies of the review, four major themes emerged. Parents felt comfortable having their children in pediatric care due to being familiar with the providers. Many felt that providers and adult-oriented health systems were not equipped to manage the medical needs of young adults with childhood-onset illness. In general, they felt that their children were not fully prepared for HCT and would have liked more support from pediatric providers with HCT prior to the transfer to adult-oriented care.

Conclusions: Parents are concerned about their children’s HCT for a variety of

Background

The emphasis on family-centered care in pediatrics means that parents of youth with chronic illness play a central role in the health and well-being of their children.1,2 In the family-centered care paradigm, parents are seen as partners with health providers in managing a child’s illness.1,2 While parents are the key

informants and partners in family-centered care when their children are young, as children become adolescents and young adults, the family-centered care framework suggests that the adolescent or young adult should take a larger role in care.1 To fully address this process of increasing the role of adolescents and young adult in their health care, guidelines to address the health care transition (HCT) from pediatric to adult-oriented care have been established to assist providers in supporting youth as they move into a more central role in health care settings and ultimately to their maximum level of independence.3,4 HCT is defined as the planned and orderly process of change from pediatric to adult systems of care.5 Transfer is the step within the transition process where an adolescent or young adult moves from pediatric to adult-oriented care.3

Social-ecological model of readiness for transition (SMART) model places emphasis on the dynamic interactions between patients, parents, and providers during HCT.7,8

As a result of their prominence in the care of their children, parents of adolescents and young adults with chronic illness have valuable information to add to the understanding of HCT as patients and families are currently experiencing it. Such information can be used in developing interventions or programs to aid in the HCT. For this reason, we sought to undertake a systematic review to collect parents’ perspectives on HCT.

Methods

Search Strategy

We searched PubMed using the search string “(parents) AND transition to adult care” as MeSH terms, limited to those articles published in the last five years. The search was completed on January 12, 2017.

Study Selection

We reviewed the titles and abstracts of all articles identified during the electronic search and removed any studies that did not meet inclusion criteria. For the remaining articles, full texts were obtained and reviewed with any articles that did not meet criteria also being excluded.

Data Abstraction and Quality Assessment

We abstracted the following data from each article: number of parents involved, numbers of other types of participants involved, qualitative method used, the diagnoses of the children in each study, and key findings from each study. Key findings were then reviewed to identify themes found across studies.

To assess study quality, each study was evaluated using the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) guidelines.9 These guidelines were developed using an extensive literature review to determine an agreed upon set of criteria of what to include in qualitative studies with the aim of ensuring more standardized reporting of qualitative studies.

Results

A total of 286 articles were captured with the original search. After abstract review, 111 remained. Of the 111 that underwent full-text review, 9 studies were found that met all eligibility criteria.10-18 See Figure 1 for the PRISMA19 diagram.

The 9 included studies are summarized in Table 1. Studies included

diagnoses, including autism spectrum disorders,10,11,16 diabetes,11,16 cystic

fibrosis,11,16 IBD,14,16 cystinosis,13 history of organ transplant,15 epilepsy,17,18 and

cerebral palsy.11,12,16 Most studies included participants other than parents in

addition to parents.10-17

Four concepts were found in multiple studies: preference for the pediatric

health care system,10-15 difficulties making the transfer from pediatric to adult

care,10-12,14,15,17,18 the financial considerations of transition,10,11,14,16,17 and a conflict

between the desire for children to be more independent and desire to ensure the

health and well-being of their children.10,11,13-17 Representative quotes for each

domain can be found in Table 2.

The preference for the pediatric health care system was found in findings both positively describing the pediatric system and negatively describing the adult-oriented system. Parents had trust in and comfort with the providers that their

children had been seeing for many years,10,11,15 and expressed a preference for the

multi-disciplinary clinic approach used frequently in the pediatric system.12 Parents

felt the adult providers lacked understanding of their child’s diagnoses in

particular10,12,13 or just felt that the overall quality of care dropped after transfer to

adult care.14 In one study, parents had been warned of poor experiences in adult

care from other families who had transferred to adult care already.13

Many studies had findings about the difficulties parents had experienced during the transfer from pediatric to adult care. Parents reported feeling rejected

by the pediatric health system,18 and that the relationship with pediatric providers

assistance from providers during the transition process would ease these

problems.12,14,15 Confusion around guardianship rules also contributed to confusion for parents during the transfer to adult care.10,17

The financial considerations during transition came in two major groups. First, parents reported concerns about their children’s ability to continue to afford necessary care. Parents worried about insurance changes at adolescents reached the age of 19 and Medicaid rules changed.11 Age-dependent availability of resources like home nursing and home equipment were also a concern.16 Other parents

worried that children would skip medications or visits if their children were not on solid financial footing.14 The other major financial issue around transition was more prominent among parents of young adults with disabilities who felt the need to ensure financial stability for their children, even though those children would not be able to manage full-time employment.10,17

Parents demonstrated a conflict between wanting more independence for their children as they reached adolescence and young adulthood while also wanting to ensure the health and safety of their children. Parents reported wanting their children to have productive lives,16,17 even if they couldn’t be fully independent.17 In one study, a sub-set of parents were looking forward to transition as an opportunity for their children to gain some amount of independence.11 Parents also stated that they appreciated providers’ efforts to help their children build skills.15 Parents felt that they were overly involved in their child’s care as their children reached

same time, parents were reluctant to cede control of care to their children13 and

placed a high priority on their children’s safety.17

Discussion

In this systematic review, we found several themes that were elicited in multiple qualitative evaluations of parents’ experiences and feelings around their child’s HCT. Parents in general preferred pediatric care because they felt more comfortable with familiar providers and felt that adult-providers were not

adequately equipped to meet the needs of young adults with pediatric-onset chronic conditions. Parents found the transfer process to be difficult and wanted more assistance and planning for transition and transfer. Financial considerations were common, including maintaining insurance access and ensuring financial stability for adults who could not maintain employment. Parents also reported a conflict

between wanting more independence for the adult-aged children and also wanting to ensure their children’s health and safety.

that parents are hesitant to leave, this study suggests that deeper investigation into this possible link is warranted.

Parents felt that discussions about transition and transfer happened abruptly and they felt unsupported during the transfer to adult care. Despite the guidelines’ recommendation to start HCT conversations early,3 providers have a tendency to start the HCT discussion around the time of transfer,22 giving parents and patients little time to plan or organize. Providers should consider being proactive about engaging in HCT discussions early not simply because guidelines say so, but also because parents have expressed a preference for that approach.12,14,15 Guidelines might also do well to emphasize that patients and families do indeed want to talk about the transition process with their providers. If providers are consistently trying to engage in family-centered care, knowing that these discussions are part of family-centeredness may result in greater adherence to guidelines among providers.

The financial concerns that parents expressed serve as an important

reminder that the HCT is one of many transitions a young adult with chronic illness is experiencing. Providers and health systems would do well to remember that while the HCT is their primary focus, patients and families may have competing interests and concerns from the other transitions that they need to address before addressing HCT. Many have advocated for a flexible, individualized approach to transition that recognizes the individual needs of a particular patient and

family.3,23,24 The findings of this study support that call.

between the traditional definitions of pediatric and adult care. Parents recognize on

some level that they should let their children be as independent as possible, but they

also feel responsible for their child’s healthy and safety. Striking the balance is

difficult for them because their children are neither clearly dependent nor clearly

independent. They are no longer children and not yet adult.

Providers also have difficulty with the fact that patients in transition do not

fit into the usual groups that the medical field has demarcated. Pediatric providers

report concerns around managing adult patients for their whole lifetimes.25,26 On

the other end, internists are licensed to care for adolescents and young adults with

and without chronic disease, but feel unprepared for “pediatric” problems.27 Family

practice providers deliver care during the whole life span, giving them experience

with “pediatric” and “adult” problems. However, data suggest that they may not

fully recognize nor fully address the many other steps of transition, such as

educating patients and ensuring their growth toward independent

self-management, because they do not have to transfer the patient to a new provider.28

Therefore, it is possible that some of the difficulties parents are having with HCT are

a function of the fact that providers are also having difficulties with HCT. As

providers consider how to improve HCT, they will need to consider the views

parents have about the process in its current form to help ensure that interventions

address the concerns that patients and parents have.

This review does have limitations. No search of the gray literature was done

as part of this review, so any relevant results from the gray literature are not

looking farther back would have almost certainly found other relevant articles.

Finally, only PubMed was searched for this review, which means that articles that

would have been found from searches of other databases are not included.

Nonetheless, we feel that it provides a good representative sample of perspectives

from parents about a child’s HCT.

Conclusions

This systematic review demonstrates that parents have a range of concerns

regarding HCT for their children with chronic illnesses. While parents report a

preference for pediatric providers and systems of care, they also recognize the

importance of HCT as a part of assisting their children in achieving their maximum

level of independence. Parents reported wanting more assistance from providers

during HCT and that they had many financial concerns regarding HCT. As providers

and health systems consider ways to improve HCT, they can consider these

concerns from parents to help ensure that proposed interventions meet the needs of

References

1. Arango P. Family-centered care. Academic pediatrics. 2011;11(2):97-99. 2. Jolley J, Shields L. The evolution of family-centered care. Journal of pediatric

nursing. 2009;24(2):164-170.

3. Cooley WC, Sagerman PJ. Supporting the health care transition from

adolescence to adulthood in the medical home. Pediatrics. 2011;128(1):182-200.

4. GotTransition. Guide for Transition Youth to Adult Health Care Providers. http://www.gottransition.org/providers/leaving.cfm. Accessed September 8, 2016.

5. Singh SP, Paul M, Ford T, et al. Process, outcome and experience of transition from child to adult mental healthcare: multiperspective study. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;197(4):305-312.

6. Betz C, Ferris M, Woodward J, Okumura M, Jan S, Wood D. The health care transition research consortium health care transition model: a framework for research and practice. Journal of pediatric rehabilitation medicine.

2014;7(1):3-15.

7. Schwartz LA, Brumley LD, Tuchman LK, et al. Stakeholder validation of a model of readiness for transition to adult care. JAMA pediatrics.

2013;167(10):939-946.

8. Schwartz LA, Tuchman LK, Hobbie WL, Ginsberg JP. A social-ecological model of readiness for transition to adult-oriented care for adolescents and young adults with chronic health conditions. Child: care, health and development. 2011;37(6):883-895.

9. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International journal for quality in health care. 2007;19(6):349-357.

10. Cheak-Zamora NC, Teti M. "You think it's hard now ... It gets much harder for our children": Youth with autism and their caregiver's perspectives of health care transition services. Autism : the international journal of research and practice. 2015;19(8):992-1001.

11. Cruz S, Neff J, Chi DL. Transitioning from Pediatric to Adult Dental Care for Adolescents with Special Health Care Needs: Adolescent and Parent

Perspectives--Part One. Pediatric dentistry. 2015;37(5):442-446.

12. DiFazio RL, Harris M, Vessey JA, Glader L, Shanske S. Opportunities lost and found: experiences of patients with cerebral palsy and their parents

transitioning from pediatric to adult healthcare. Journal of pediatric rehabilitation medicine. 2014;7(1):17-31.

13. Doyle M, Werner-Lin A. That eagle covering me: transitioning and connected autonomy for emerging adults with cystinosis. Pediatric nephrology (Berlin, Germany). 2015;30(2):281-291.

14. Gray WN, Resmini AR, Baker KD, et al. Concerns, Barriers, and

Perspectives of Patients, Parents, and Health Professionals. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2015;21(7):1641-1651.

15. Lochridge J, Wolff J, Oliva M, O'Sullivan-Oliveira J. Perceptions of solid organ transplant recipients regarding self-care management and transitioning. Pediatric nursing. 2013;39(2):81-89.

16. Okumura MJ, Saunders M, Rehm RS. The Role of Health Advocacy in Transitions from Pediatric to Adult Care for Children with Special Health Care Needs: Bridging Families, Provider and Community Services. Journal of pediatric nursing. 2015;30(5):714-723.

17. Rehm RS, Fuentes-Afflick E, Fisher LT, Chesla CA. Parent and youth priorities during the transition to adulthood for youth with special health care needs and developmental disability. ANS Advances in nursing science.

2012;35(3):E57-72.

18. Schultz RJ. Parental experiences transitioning their adolescent with epilepsy and cognitive impairments to adult health care. Journal of pediatric health care : official publication of National Association of Pediatric Nurse Associates & Practitioners. 2013;27(5):359-366.

19. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

20. Pediatrics AAo. Department of Research. Survey: transition services lacking for teens with special needs. AAP News. 2009;30(11):12.

21. ODPHP. Healthy People 2020 Objectives - Disability and Health. 2014; https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/objective/dh-5. Accessed September 7, 2016.

22. Burke R, Spoerri M, Price A, Cardosi A-M, Flanagan P. Survey of primary care pediatricians on the transition and transfer of adolescents to adult health care. Clinical pediatrics. 2008;47(4):347-354.

23. Schor EL. Transition: changing old habits. Pediatrics. 2015;135(6):958-960. 24. Sharma N, O’Hare K, Antonelli RC, Sawicki GS. Transition care: future

directions in education, health policy, and outcomes research. Academic pediatrics. 2014;14(2):120-127.

25. Fernandes S, Khairy P, Fishman L, et al. Referral patterns and perceived barriers to adult congenital heart disease care: results of a survey of US pediatric cardiologists. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2012;60(23):2411.

26. Kenney LB, Melvin P, Fishman LN, et al. Transition and transfer of childhood cancer survivors to adult care: a national survey of pediatric oncologists. Pediatric blood & cancer. 2017;64(2):346-352.

27. Peter NG, Forke CM, Ginsburg KR, Schwarz DF. Transition from pediatric to adult care: internists' perspectives. Pediatrics. 2009;123(2):417-423.

Figure 1. PRISMA Diagram of Studies in Systematic Review

Records identified through Pubmed search

(n = 286)

Records screened (n = 286)

Records excluded (n = 175)

Full-text articles assessed for eligibility

(n = 111)

Full-text articles excluded, with reasons

(n = 101)

!22 had no primary data !23 focused on topics

other than transition !22 survey studies !11 done outside the US !11 other types of papers (program evaluation, tool validation, case studies)

!8 had no data from parents

!3 with interviews and surveys ! 2 non-English Studies included in

e

1:

Summary

of

Fin

din

gs

from

In

cl

ude

d

Artic

le

s

Au th or (s ) Ye ar N umb er o f Parent s Includ ed Oth er par ticipants Quali tati ve Me th od Used Chil d’ s Dia gn osis/ es Su mma ry o f K ey F in di ng s fr om Pa re nt s Chea k-Za mo ra a nd Tet i 201519 (17

mo th er s) Yo uth age s 15 to 25 Focu s gr oups Au ti sm sp ec tr um disorders ! Par ents ar e wor ried about los ing rel at ion ship s w it h tru st ed providers an d fel t t ha t su pp ort for tra nsit ion w as la ck ing. ! Par ents

feel that ad

ult pr ovid er s lack un de rs ta nd in g of a ut is m. ! Par ents found guar dians hip and pr ivacy la w s di ff ic ul t t o ma na ge . Cru z, et a l. 2015

59 (81%

mo th er s) Yo uth age s 13 to 17 Focu s gr oups and int erview s Va ries ! Many par ents r epor ted feeling co mf or ta bl e co nt in ui ng in p ed ia tr ic c ar e indefinit el y, ra ther t ha n t ra nsit ioning t o ad ult car e. ! Par ents wor ried about ins ur ance changes resul

ting in l

ack

of access t

o care,

par

ticular

ly with Med

DiFa zio, et a l. 2014 8 (6 mo th er s) Ad ul t

patients ages 2

4 to 44 Focu s gr oups Cereb ra l pals y ! Par ents felt lef

t out of

the tr ans ition pr oces s and

felt that ped

iatr ic pr ovid er s ended t he rel at ionship t oo a brupt ly. ! P ar en ts w an te d mo re ti me to p la n he al th care t ransit

ion and w

ant

ed providers t

o gi ve th em a pl an a s to h ow tr an si ti on wo uld be e xpe cte d to proceed. ! Par ents

felt that ad

ult pr ovid er s lacked ex perience ca

ring for pa

tient s w it h cereb ral pal

sy and ex

pressed a desire for

th e mu lt i-discip lina ry ca re set tings tha t ar e co mmo n in p ed ia tr ic c ar e to c on ti nu e in a dul t ca re. ! Par ents would like to

know that the

pr

ovid

er

s they ar

e going to in ad

ult car e ar e kno wn to and tr us te

d by th

ei r ped iatr ic pr ovid er s. Doyl e an d We rne r-Lin 2015

24 (13

mo th er s) Ad ul t

patients ages 1

8 to 47 Focu s gr oups and int erv iew s Cyst in osis ! Mother

s in par

ticular expr es sed fear of le av ing tr us te d pe di atr ic pr ov id er s. ! Many par ents had hear d s tor ies of bad ou tc ome s fo r pa ti en ts a ft er le av in g ped iatr ic car e. ! Par ents wer e r

eluctant to ced

Gra

y, et

a

l.

2015

16 (14

mo th er s) 15 pa ti ents (avg. age 2 0

years) 13

pr ovid er s (a dul t a nd ped iatr ic) Focu s gr oups IBD ! Al l g ro up s, in cl ud in g pa re nt s, e xp re ss ed concern ab out

a drop in care qual

it y aft er tr ans fe r to ad ult -orient ed ca re. ! Par ents being involved pr evented the pa ti en ts fr om le ar ni ng s el f-ma na ge me nt . ! P ar en ts w or ri ed th at th ei r ch ild re n ma y sk ip a pp oi nt me nt s or me di ca ti on s du e to cost s aft er t hey w ere responsib

le for t

heir

care. ! P

ar en ts w an te d mo re g ui da nc e du ri ng tr ans iti on and d ur ing tr ans fe r and wante d tr an sf er to o cc ur “ du ri ng a ti me o f st ab ilit y.” e, et al. 2013 10 (7 mo th er s) 10 pa tient s age s 1 7 to 22 Inter views Tra nsp lant recip ien ts ! Par ents wor ried

about leaving tr

us ted pr ovid er s. ! Par ents felt over ly involved in their chil dren’s care. ! Par ents appr eciated pr ovid er s tr ying to bui ld a pati ent’s ind epe nd enc e and wante d to s uppo rt th ei r ch ild re n’ s mo ve to w ar d

independence. ! Par

ents w an te d mo re a ss is ta nc e fr om pr ovid er

s with tr

O ku mu ra , e t al. 2015 9 (gender not sp ecified) 13 pa tient s (a

ges 16 t

o

25) 12

hea lt hca re pr ovid er s 7 co mmu ni ty

service provid

er s Inter views Va ries ! Par ents r epor ted

that they f

elt they

needed to “fight” for

the ser vices their chil dren needed. ! P ar en ts c on fr on te d ma ny lo gi st ic al ba rr ie rs to g et ti ng n ee de d eq ui pme nt a nd se rv ic es , s uc h as c on fu si ng r eq ui re me nt s or l

oss of services a

t a cert ain a ge. ! Par ents found it helpf

ul when pr

ovid er s hel ped t heir chil dren t hink a bout the fu tu re. R eh m, e t a l. 2012 77 (gender not sp ecified) 64 pa ti ents age s 1 4 to 26 27 hea lt h care pr ovid er s 46 sp ecia l educa tion te ac he rs Fiel d st udy (incl uded int erview s wi th par ents ) Va ries ! Par ents wanted their child

ren to be as

independent

a

s possib

le, recognizing t

ha t th is ma y ne ve r be fu ll in de pe nd en ce . !

Keeping health cond

itions und er contr ol was a to p pr io ri ty fo r par ents . ! P ar en ts w er e fo cu se d on ma in ta in in g a sa fe and secu re environ me nt fo r th ei r chil dren, w het her t heir chil dren l ived w it h th em fo r no t. ! F inancial concer ns and guar dians hip co ns id er at io ns w er e co mmo n. ! Par ents wanted their child

ren to have

pr od uctive and enjoyable lives as ad ults , but f ind ing th e appr opr iate ave nue for par

ticipating in s

Schultz 2013 7 (gender not sp ecified) None Inter views Epileps y and severe or pr of ound int el lect ua l disa bil it y (chil dren of par ticipating par ents had to h av e bo th ) ! Par ents

felt the tr

ans ition was s par ked by a c ri si s, s uc h as a c hange in i ns ur anc e. ! Par ents fr equently expr es sed feelings of rej ect ion . ! Pa re nt s of te n as su me d th e ro le o f ad vo cate and co or di nato r f or th ei r chil dren d urin g tr ans ito n. ! Par ents had d ifficu lt y get ting accu ra te in fo rma ti on , a nd fo un d th at o ft en th e ag en ci es s et u p to h el p th em w er e th e le as t he lp fu l s ou rc e of in fo rma ti on . ! Par ents wer e f

requently in s

Table 2: Themes and Representative Quotes

Theme Representative Quotes

Preference for Pediatric Care

“There’s so many more comprehensive interdisciplinary pediatric services period for any illness than there are for adults.”12

“They (adult providers) don’t do that, that care, and they’re not on you all the time.”14

“My honest opinion is I don’t think anyone should get asked to leave before they are ready to leave, because if someone is afraid to leave, there is a reason for it.”15

Difficulties Making the Transfer from Pediatric to Adult Care

“You’re kicking me to the curb.”18

“I think a discussion needs to occur earlier, a lot earlier and they just need to bring this up with the two parents and adolescent at an earlier age so that everybody, parent and child become

comfortable with the fact that we are going to have a transition period…”12

Financial

Concerns “I mean there may well be a time in which [my daughter's] career choices will be affected by not only the need to get insurance but also by her experience with the medical care system, which it should.”16

“As I’m staring at that, trying to figure out all the ramifications of if he gets a job and he doesn’t get a job, what could Section 8 do for us, and could I get a voucher for him?”17

Conflict

between Desire for Child’s Independence and Desire for Child’s Health and Well-being

“I can’t get any information. I can’t get anything. So, that’s why we went in for guardianship.”10

“we want him to eventually be as healthy and as independent as (possible).”11

“We’ve been so focused on keeping them healthy and keeping up

with their meds. It’s hard to give that control over to them.”13

Table 3: Quality Assessment of Included Articles Based on COREQ

Guidelines

Article

Research team and reflexivity score (out of a total possible of 8)

Study design score (out of a total possible of 15)

Analysis and findings score (out of a total

possible of 9)

Total score (out of a total possible of 32)

Cheak-Zamora and

Teti, 2015 4 9 7 20

Cruz et al., 2015 2 9 8 19

DiFazio, et al., 2014 3 14 9 26

Doyle and

Werner-Lin, 2015 0 11 9 20

Gray, et al., 2015 6 13 7 26

Lochridge, et al.,

2013 1 11 7 19

Okumura, et al.,

2015 3 10 7 20

Rehm, et al., 2012 1 6 8 15

Association of Youth Health Care Transition Readiness to

Role Overload among Parents of Children with Chronic

Illness

Abstract

Background: Models of health care transition (HCT) from pediatric- to

adult-oriented care for youth with chronic conditions include the importance of the

parent-child relationship as a factor in HCT success, including the development of

HCT readiness for youth. A parent’s level of role overload has been shown to be

associated with negative outcomes for youth, suggesting that it may be associated

with less HCT readiness as well. We sought to assess this relationship.

Methods: Youth with chronic conditions attending a therapeutic camp and their

parents were invited to complete an on-line survey that assessed their demographic

characteristics, the degree of parental role overload and the youth’s HCT readiness.

Results: Out of 546 parents invited to complete the survey, 152 did so, for a

response rate of 28%. Out of 546 youth approached, 58 completed the survey, for a

response rate of 11%. For this analysis we focused on the 50 pairs where both

parent and youth completed the survey. After controlling for youth’s age, sex, and

degree of youth’s educational support, parental role overload and HCT readiness

Conclusion: In this study, a parent’s level of role overload had little effect on youth

HCT readiness, even after controlling for confounders. This unexpected result may

be due to this study’s small sample size, the limitations of the measures used, or the

Background

The numbers of adults with childhood-onset chronic illness are growing.1-5

As such, increased attention is being paid to the successful health care transition

(HCT) of youth as they age out of the pediatric health system and move into

adult-oriented care. Improvements in HCT have been included as a Healthy People 2020

goal.6

HCT is a process in which children and adolescents (youth) with chronic

conditions and their parents are gradually moved from pediatric to adult-oriented

systems of care.7 Several models have discussed the importance of parents in the

HCT process. The HCTRC model describes HCT as an interplay between four

overlapping domains, of which the family and social support system is one.8 The

SMART model9 centers on the interactions between patients, parents, and providers,

as these are the likely targets of any intervention to improve HCT.9 Both models lay

out an excellent broad overview of HCT that allow for targeted research to explore

HCT further. In particular, they highlight the importance of eliciting the discrete

characteristics of parents that contribute to or detract from the HCT process. For

this paper, we chose to explore how a parent’s level of role overload influences

youth HCT readiness.

Role overload is a concept that has been developed in the sociology and

psychology literature. It is defined as a situation when the total demands on time

and energy associated with the prescribed activities of multiple roles are too great

to perform the roles adequately or comfortably.10 A person experiencing role

roles due to a lack of time or energy. Previous studies have shown that role

overload in parents is associated with poorer outcomes, including increased marital

conflict,11 decreased warmth in parents and adolescents,12 and increased

parent-adolescent conflict.13 For this reason, we hypothesized that higher levels of parent

role overload would be associated with less HCT readiness among youth. We sought

to test this hypothesis through surveying parents of youth attending the therapeutic

Victory Junction camp, which is specifically geared toward youth with significant

chronic diseases and developmental disabilities.

Methods

Population and Recruitment Procedures: Victory Junction is a therapeutic

summer camp for children ages 6 to 17 with a variety of chronic conditions. For this

study, all youth attending Victory Junction Camp during the summer of 2016 and

their parents were approached via email prior to their youth attending camp as well

as in person on the first day their youth were attending camp. Youth were not

excluded based on diagnosis or age. Previous work has found that experiences are

not substantially different across diagnoses and that there are commonalities due to

the presence of any chronic condition.14 Thus, we did not feel that focusing on a

particular diagnosis was necessary for this study.

Surveys and consent from parents and assent from youth were completed

online via a Qualtrics™ survey at the time of survey completion. There was no

incentive for participation in the study. This study was approved by the UNC

Measures

Role Overload: The Reilly Role Overload Scale is a 13-item scale developed by

Michael Reilly and first published in 1982 in an article looking at how role overload

correlated with convenience food consumption in working wives.15 Since its

development, it has been utilized to assess role overload in parents.11,12,16,17 For our

study we used the version that was validated in parents by Thiagarajan et al. using a

confirmatory factor analysis of the full scale.17 This analysis showing that a 6-item

scale had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.87-0.89 (online vs. mail-in surveys). For a full list

of the questions in the scale, please see Appendix A.

HCT Readiness: The outcomes of HCT readiness was self-reported by youth with

chronic conditions using the STARx Questionnaire. 18,19 This questionnaire was

developed with input from youth about its relevance,19 and has been validated in

youth with a variety of health conditions.18 It consists of questions asking about a

youth’s confidence with a variety of skills, including disease knowledge (“How much

do you know about your illness?”), medication management (“How often do you

remember to take your medications on your own?”), and engaging with health care

providers (“How easy or hard is it to talk to your doctor?”).19 All questions are

answered on a 5-point Likert scale, with the answer choices varying the questions.

For questions starting, “How often…,” responses ranged from “Never” to “Always.”

For questions starting, “How much…,” responses ranged from “Nothing” to “A lot.”

For questions starting, “How easy…,” responses ranged from “Very Hard” to “Very

All questions are scored from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating greater

HCT readiness. There are a total of 18 questions on the scale that were chosen for

their clinical relevance. However, factor analysis done previously indicates that the

scale has a three-factor structure made of 13 of the 18 questions in the scale.20

These factors are Disease Knowledge, Self-Management, and Provider

Communication.

Previously, the score for the STARx has been calculated using a total score for

each participant. However, not all youth with a chronic illness take medications, so

they would look less HCT ready if this addition strategy were used. Thus, for this

study, we reported each domain and the total scores as the mean of the answered

items in order to include those who took no medications. Thus, the scores for the

domains and total score ranged from 1 to 5.

Demographics: Parents were asked to provide demographic information about themselves and their youth, including the parents’ age and sex, youth’s age and sex,

and characteristics about the youth, such as diagnosis, age at diagnosis, educational

support received in school.

Youth diagnoses and Educational Support: The youth’s diagnoses were categorized by primary organ system involved. For example, asthma and cystic

fibrosis were categorized as pulmonary disorders, and inflammatory bowel disease

was categorized as a gastrointestinal disorder. Educational support was categorized

as having no specific educational support, having a 504 plan in school, and having an

individualized education plan (IEP) in school with or without a 504 plan. A 504 plan

a child’s medical diagnosis, such as a child with ADHD sitting in the front of a

classroom to avoid distraction or a child with migraines having a water bottle with

them to help them stay hydrated, but does not necessarily allow for more extensive

changes to educational expectations, such as extended time for tests. An IEP is a

specialized education plan made by the school with input from parents and youth

that provides for these more extensive modifications, and extra support services,

such as occupational therapy or speech therapy, for children who require them.

Statistical Analysis: We performed an analysis on those pairs of parents and youth who both completed the survey, using the parent’s response for role overload and

the youth’s response on the STARx as the measure of HCT readiness (n= 50). We

opted for this approach because it allowed us to most effectively relate parent’s role

overload to youth HCT readiness within this particular data set.

We initially examined the characteristics of the sample to determine

distribution of variables as well as to assess for missing data. Means and standard

deviations were calculated for continuous variables and frequencies were calculated

for categorical variables. We made the a priori decision to assess for possible

confounding due to child’s age, child’s sex, and child’s educational support. Older

age21,22 and female sex23,24 were chosen because they are associated with higher

levels of HCT readiness in the literature. Intellectual disability appears to be

associated with less HCT readiness,25 so we included the child’s education support

as a marker of intellectual difficulties. We performed bivariate analyses assessing

the association between these possible confounders and the STARx factor and total

STARx factor and total scores. Finally, we used linear regression to evaluate for the

associations between HCT readiness and parent overload, adjusted for the

confounders assessed previously.

Because this was an exploratory study, we did not make adjustments for

multiple comparisons, as this increases the likelihood of a Type II error,26 which

could potentially cut off important avenues of research prematurely while still in an

exploratory phase. All analyses were performed using STATA 14 (College Station,

TX). Significance level was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Out of 546 pairs of parents and youth approached for participation, 152

parents and 58 youth participated, for participation rates of 28% for parents and

11% for youth. For this paper, we focused on the 50 parent-youth dyads where

both parents and youth completed the survey.

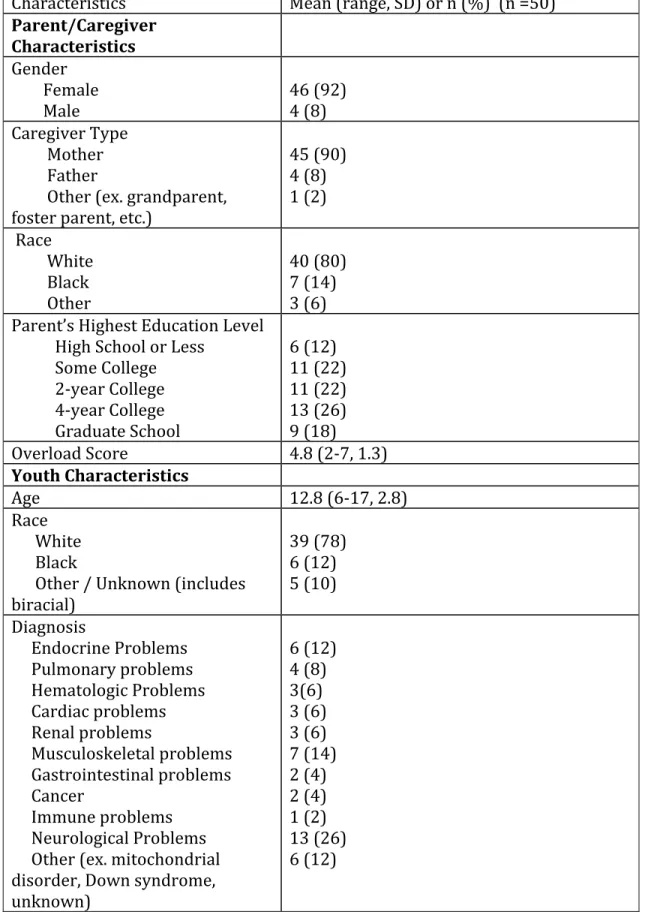

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the parents and children in

this study. Most of the parents (90%) were mothers and had completed at least

some college. Children had a mean age of 12.8 years, and most (78%) were white.

The majority (58%) were covered by private health insurance.

The bivariate comparisons showed that in this sample educational support

was associated with HCT readiness in that those with an IEP had lower mean HCT

readiness scores than those with a 504 plan or no educational support. Child’s age

and sex were not associated with HCT readiness scores in this sample.

Table 2 shows the unadjusted associations between parent overload and the

score. Parent overload was not associated with STARx score overall or to any of the

factors.

Table 3 shows the adjusted associations between parent overload and STARx

factors and between parent overload and the STARx total score. Even after

adjusting for child’s age, child’s sex, and child’s educational support, there was no

significant association between parent overload and any of the STARx measures.

Discussion

In this study, we hypothesized that higher levels of parent role overload

would be associated with lower levels of youth HCT readiness. However, the data

did not support this hypothesis. In fact, there was no statistically significant

relationship between level of parent overload and youth HCT readiness in

unadjusted or adjusted analyses.

Possible reasons for this discrepancy between our hypothesis and the data

include the small sample size of the study, limitations in the measures used, and the

high level of variability in the youth in the study. This study included 50

parent-youth dyads, and while this is comparable to some other studies that have looked at

associations of HCT readiness to other youth characteristics,21,27-29 it may have been

too small to detect the association between parent overload and HCT readiness. The

STARx Questionnaire20,22 and Reilly Role Overload Scale15,17 have shown good

reliability and internal validity when these have been assessed. However, as with

any measure, they are not perfect in their abilities to describe the phenomena we

we were unable to detect it with these measures. Additionally, parent role overload

may not influence youth HCT readiness but may be associated with other facets of

HCT, such as ability to get to appointments with new providers, which were not

measured here. Finally, the youth participants in this study had a large range in age

(6-17) and in diagnoses. It is possible that the relationship between parent role

overload and HCT readiness does hold for certain age groups or for certain

diagnoses. Because we chose to combine the sample into one analysis, we were

unable to detect any sub-groups for which this is true.

Interestingly, the direction of the point estimates for the betas was consistent

with our hypothesis. For example, the beta estimate for the adjusted STARx

Questionnaire total score and parent overload was -0.06, suggesting that if a

relationship between parent overload and STARx score were to be significant, it

would be an inverse relationship with higher levels of overload being associated

with less HCT readiness. So it seems very possible that the hypothesized

relationship does exist, but this data set did not detect it.

In considering the implications should the findings of this paper prove to be

true, these results, should they be replicated, would influence the models that have

been developed to understand HCT. As discussed in the introduction, parents are

considered a key driver of the HCT process for youth in the models that have been

published.8,9 What this study suggests is that a youth’s ability to obtain HCT

readiness skills is not tied to the degree to which his or her parent’s experience role

overload. In other words, parent role overload neither prevents youth from

future work continues to demonstrate this finding, the current models can be further refined to clarify exactly where and how parents influence the HCT process, and interventions can be tailored accordingly.

This study is limited by the small size of the sample, which may have led to a Type II error. Additionally, the participation rate for the youth in the study was quite low. It is also limited in its use of self-report for all items, which can affect accuracy of the data. Our choice to include those participants who don’t take medication and use the mean of the available items for the STARx results may have affected the results as well. Nonetheless, we feel it adds to our ability to refine the models of HCT.

Conclusions

References:

1. About Cystic Fibrosis. www.cff.org/What-is-CF/About-Cystic-Fibrosis/. Accessed September 8, 2016.

2. Fast Facts: Data and Statistics about Diabetes.

http://professional.diabetes.org/content/fast-facts-data-and-statistics-about-diabetes/?loc=dorg_statistics. Accessed May 4, 2016.

3. Childhood Cancers. http://www.cancer.gov/types/childhood-cancers#3. Accessed June 30, 2016.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Down Syndrome: Data and Statistics.

https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/birthdefects/downsyndrome/data.html. Accessed June 30, 2016.

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Most Recent Asthma Data. https://www.cdc.gov/asthma/most_recent_data.htm. Accessed July 6, 2016. 6. ODPHP. Healthy People 2020 Objectives - Disability and Health. 2014;

https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/objective/dh-5. Accessed September 7, 2016.

7. Cooley WC, Sagerman PJ. Supporting the health care transition from

adolescence to adulthood in the medical home. Pediatrics. 2011;128(1):182-200.

8. Betz C, Ferris M, Woodward J, Okumura M, Jan S, Wood D. The health care transition research consortium health care transition model: a framework for research and practice. Journal of pediatric rehabilitation medicine.

2014;7(1):3-15.

9. Schwartz LA, Tuchman LK, Hobbie WL, Ginsberg JP. A social-ecological model of readiness for transition to adult-oriented care for adolescents and young adults with chronic health conditions. Child: care, health and development.

2011;37(6):883-895.

10. Voydanoff P. Linkages between the work-family interface and work, family, and individual outcomes An integrative model. Journal of Family Issues.

2002;23(1):138-164.

11. Perry-Jenkins M, Goldberg AE, Pierce CP, Sayer AG. Shift work, role overload, and the transition to parenthood. Journal of Marriage and Family.

2007;69(1):123-138.

12. Wheeler LA, Updegraff KA, Crouter A. Work and Mexican American parent– adolescent relationships: The mediating role of parent well-being. Journal of Family Psychology. 2011;25(1):107.

13. Crouter AC, Bumpus MF, Maguire MC, McHale SM. Linking parents' work pressure and adolescents' well being: Insights into dynamics in dual earner families. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35(6):1453.

14. Perrin EC, Newacheck P, Pless IB, et al. Issues involved in the definition and classification of chronic health conditions. Pediatrics. 1993;91(4):787-793. 15. Reilly MD. Working wives and convenience consumption. Journal of consumer

research. 1982:407-418.

17. Thiagarajan P, Chakrabarty S, Taylor RD. A confirmatory factor analysis of Reilly's Role Overload Scale. Educational and Psychological Measurement.

2006;66(4):657-666.

18. Cohen SE, Hooper SR, Javalkar K, et al. Self-Management and Transition Readiness Assessment: Concurrent, Predictive and Discriminant Validation of the STARx Questionnaire. Journal of pediatric nursing. 2015;30(5):668-676. 19. Ferris M, Cohen S, Haberman C, et al. Self-Management and Transition

Readiness Assessment: Development, Reliability, and Factor Structure of the STAR x Questionnaire. Journal of pediatric nursing. 2015;30(5):691-699. 20. Ferris M, Nazareth M, Hart LC, et al. STARx-P, a Parent Version of the STARx

Questionnaire: Initial Reliability in a Multi-institution Study. Paper presented at: Health Care Transition Research Consortium Research Meeting; October, 2016; Houston, TX.

21. Cantu-Quintanilla G, Ferris M, Otero A, et al. Validation of the UNC

TRxANSITION ScaleVersion 3 Among Mexican Adolescents With Chronic Kidney Disease. Journal of pediatric nursing. 2015;30(5):e71-81.

22. Ferris M, Cohen S, Haberman C, et al. Self-Management and Transition Readiness Assessment: Development, Reliability, and Factor Structure of the STARx Questionnaire. Journal of pediatric nursing. 2015;30(5):691-699. 23. Sawicki GS, Lukens-Bull K, Yin X, et al. Measuring the transition readiness of

youth with special healthcare needs: validation of the TRAQ--Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire. Journal of pediatric psychology.

2011;36(2):160-171.

24. Javalkar K, Fenton N, Cohen S, Ferris M. Socioecologic factors as predictors of readiness for self-management and transition, medication adherence, and health care utilization among adolescents and young adults with chronic kidney disease. Preventing chronic disease. 2014;11:E117.

25. Beal SJ, Riddle IK, Kichler JC, et al. The Associations of Chronic Condition Type and Individual Characteristics With Transition Readiness. Academic pediatrics. 2016;16(7):660-667.

26. Rothman KJ. No adjustments are needed for multiple comparisons.

Epidemiology. 1990;1(1):43-46.

27. Bingham CA, Scalzi L, Groh B, Boehmer S, Banks S. An assessment of variables affecting transition readiness in pediatric rheumatology patients. Pediatric rheumatology online journal. 2015;13(1):42.

28. Whitfield EP, Fredericks EM, Eder SJ, Shpeen BH, Adler J. Transition readiness in pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease: patient survey of self-management skills. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 2015;60(1):36-41.

29. Fenton N, Ferris M, Ko Z, Javalkar K, Hooper SR. The relationship of health care transition readiness to disease-related characteristics, psychosocial factors, and health care outcomes: preliminary findings in adolescents with chronic kidney disease. Journal of pediatric rehabilitation medicine.

Table 1: Characteristics of the Sample

Characteristics Mean (range, SD) or n (%) (n =50)

Parent/Caregiver Characteristics

Gender Female

Male 46 (92) 4 (8)

Caregiver Type Mother Father

Other (ex. grandparent, foster parent, etc.)

45 (90) 4 (8) 1 (2)

Race White Black Other

40 (80) 7 (14) 3 (6) Parent’s Highest Education Level

High School or Less Some College 2-year College 4-year College Graduate School

6 (12) 11 (22) 11 (22) 13 (26) 9 (18)

Overload Score 4.8 (2-7, 1.3)

Youth Characteristics

Age 12.8 (6-17, 2.8)

Race White Black

Other / Unknown (includes biracial)

39 (78) 6 (12) 5 (10)

Diagnosis

Endocrine Problems Pulmonary problems Hematologic Problems Cardiac problems Renal problems

Musculoskeletal problems Gastrointestinal problems Cancer

Immune problems Neurological Problems Other (ex. mitochondrial disorder, Down syndrome,

Insurance Public Private Both

8 (16) 29 (58) 13 (26) Educational Plans

No 504

IEP (with or without 504) Regular track

11 (22) 10 (20) 29 (58)

STARx Scores

Disease Knowledge Self-Management

Provider Communication Overall

Table 2: Unadjusted associations between STAR

xQuestionnaire

scores* and parent overload

Analysis Beta p-value 95% CI

STARx vs. Parent Overload -0.1 0.20 -0.25 – 0.05

Disease Knowledge vs. Parent Overload -0.14 0.12 -0.31 – 0.04

Self-Management vs. Parent Overload -0.13 0.10 -0.29 – 0.03

Provider Communication vs. Parent

Overload -0.05 0.70 -0.28 – 0.19

Table 3: Adjusted* Associations between STARx** Questionnaire

scores and parent overload

Analysis Beta p-value 95% CI

STARx** Total vs. Parent Overload -0.06 0.44 -0.21 – 0.09

Disease Knowledge vs. Parent Overload -0.11 0.18 -0.20 – 0.16

Self-Management vs. Parent Overload -0.10 0.22 -0.25 – 0.06

Provider Communication vs. Parent Overload 0.02 0.89 -0.23 – 0.26 * Adjusted for youth’s age, youth’s sex, and youth’s educational support

Appendix A: The Reilly Role Overload Scale

For the following questions, please rate how much you agree or disagree with the following statements, with 1 being “strongly disagree” and 7 being "strongly agree.”

Strongly

Agree Agree Somewhat agree Neu-tral Somewhat disagree Disagree Strongly disagree 1. I have to

do things that I do not really

have the time and energy for.

! ! ! ! ! ! !

2. I need more hours

in the day to do all the

things that are expected of

me.

! ! ! ! ! ! !

3. I cannot ever seem to catch up.

! ! ! ! ! ! !

4. I do not ever seem to have any

time for myself.

! ! ! ! ! ! !

5. There are times when

I cannot meet everyone’s expectation

s.

! ! ! ! ! ! !

6. I seem to

commitmen ts to overcome than some

other parents I

Appendix B: The STARx Questionnaire

Patients with chronic diseases have special skills and tasks they must do. How often have YOU done each thing in the PAST THREE MONTHS?

Never Almost Never Sometimes Always Almost Always

Not needed for my care

/ I don’t take medicines right now 1. How often

did you make an effort to understand what your doctor told you?

! ! ! ! ! !

2. How often did you take your

medicines on your own?

! ! ! ! ! !

3. How often did you ask the doctor or nurse

questions about your illness, medicines or medical care?

! ! ! ! ! !

4. How often did you make your own appointments?

! ! ! ! ! !

5. How often did you need someone to remind you to take your medicines?

6. How often did you use things like pillboxes, schedules or alarm clocks to help you take your medicines when you were

supposed to?

! ! ! ! ! !

7. How often did you use the internet, books or other guides to find out more about your illness?

! ! ! ! ! !

*Some patients know a lot about their health and some patients don't. *How much do you know?

*Please check the answer that best describes how much you feel you know TODAY

Nothing Not Much Some A Lot

Not needed for care / I don’t take medications right now 10. How

much do you know about your illness?

! ! ! ! !

11. How much do you know about taking care of your illness?

12. How much do you know about what will happen if you don't take your medicines?

! ! ! ! !

*Some patients may find it hard to do certain things. *How easy or hard is it for you to do the following things? *Please check the answer that best describes how you feel TODAY

Very Hard

Somewhat Hard

Neither hard nor

easy

Somewhat

easy Very Easy

Not needed

for my care / I don’t take medicines right now 13. How

easy or hard is it for you to talk to your doctor?

! ! ! ! ! !

14. How easy or hard is it for you to make a plan with your doctor to care for your health?

15. How easy or hard is it for you to see your doctor by yourself?

! ! ! ! ! !

16. How easy or hard is it for you to take your medicines like you are supposed to?

! ! ! ! ! !

17. How easy or hard is it for you to take care of

yourself?

! ! ! ! ! !

18. How easy or hard do you think it will be for you to move from pediatric to adult care?

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank everyone in the Maria Ferris lab for all of their help and

support with this project, with particular thanks to Dr. Maria Ferris, Dr. Richard

Faldowski, Dr. Robert Campbell, Meaghan Nazareth, and Maggwa Ndugga, who

helped me in particular with this project.

I would also like to thank Dr. Anthony Viera for his support and feedback on

this paper.

Lastly, I would like to thank all of the parents and campers from Victory

Junction Camp who completed the surveys that provided the data that allowed this