Council on Education for Public Health Adopted on October 13, 2012

REVIEW FOR ACCREDITATION OF THE

SCHOOL OF PUBLIC HEALTH AT THE

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

COUNCIL ON EDUCATION FOR PUBLIC HEALTH

SITE VISIT DATES:

March 21-23, 2012

SITE VISIT TEAM:

Ian Lapp, PhD, Chair

Marie Diener-West, PhD

Sylvia E. Furner, PhD, MPH

Penney Reese, MS

SITE VISIT COORDINATOR:

Table of Contents

Introduction ... 1

Characteristics of a School of Public Health ... 2

1.0 THE SCHOOL OF PUBLIC HEALTH. ... 3

1.1 Mission. ... 3

1.2 Evaluation and Planning ... 5

1.3 Institutional Environment ... 7

1.4 Organization and Administration ... 10

1.5 Governance ... 11

1.6 Resources ... 13

2.0 INSTRUCTIONAL PROGRAMS. ... 14

2.1 Master of Public Health Degree ... 14

2.2 Program Length ... 16

2.3 Public Health Core Knowledge ... 16

2.4 Practical Skills ... 18

2.5 Culminating Experience ... 21

2.6 Required Competencies ... 22

2.7 Assessment Procedures. ... 24

2.8 Other Professional Degrees. ... 25

2.9 Academic Degrees ... 26

2.10 Doctoral Degrees ... 27

2.11 Joint Degrees ... 27

2.12 Distance Education or Executive Degree Programs ... 28

3.0 CREATION, APPLICATION AND ADVANCEMENT OF KNOWLEDGE. ... 29

3.1 Research. ... 29

3.2 Service ... 30

3.3 Workforce Development ... 32

4.0 FACULTY, STAFF AND STUDENTS. ... 34

4.1 Faculty Qualifications ... 34

4.2 Faculty Policies and Procedures ... 34

4.3 Faculty and Staff Diversity ... 35

4.4 Student Recruitment and Admissions ... 36

4.5 Student Diversity ... 38

4.6 Advising and Career Counseling ... 38

Introduction

This report presents the findings of the Council on Education for Public Health (CEPH) regarding the School of Public Health at the University of Michigan (UMSPH). The report assesses the school’s compliance with the Accreditation Criteria for Schools of Public Health, amended June 2005. This accreditation review included the conduct of a self-study process by school constituents, the preparation of a document describing the school and its features in relation to the criteria for accreditation, and a visit in March 2012 by a team of external peer reviewers. During the visit, the team had an opportunity to interview school and university officials, administrators, teaching faculty, students, alumni and community representatives, and to verify information in the self-study document by reviewing materials provided on site in a resource file. The team was afforded full cooperation in its efforts to assess the school/college and verify the self-study document.

The University of Michigan was one of the first public universities in the United States. It was founded in 1817 and moved to its current location in Ann Arbor in 1837. The university has 19 schools and colleges, including the School of Public Health and the following: College of Architecture and Urban Planning; College of Engineering; College of Literature, Science and Arts; College of Pharmacy; Rackham School of Graduate Studies; School of Art and Design; School of Business Administration; School of Dentistry; School of Education; School of Information; School of Kinesiology; School of Law; School of Medicine; School of Music; School of Natural Resources and Environment; School of Nursing; School of Public Policy; and School of Social Work.

The UMSPH was founded in 1941. It offers a range of academic and professional public health degrees, including professional and academic master’s degrees and academic doctoral degrees. The academic degrees are officially conferred by the Rackham School of Graduate Studies, though these degrees, like the professional degrees, are administered by the school.

The UMSPH has been accredited since 1968. Its last review, in 2005, resulted in a seven-year term of accreditation with no required interim reporting.

Characteristics of a School of Public Health

To be considered eligible for accreditation review by CEPH, a school of public health shall demonstrate the following characteristics:

a. The school shall be a part of an institution of higher education that is accredited by a regional accrediting body recognized by the US Department of Education.

b. The school and its faculty shall have the same rights, privileges and status as other professional schools that are components of its parent institution.

c. The school shall function as a collaboration of disciplines, addressing the health of populations and the community through instruction, research, and service. Using an ecological perspective, the school of public health should provide a special learning environment that supports interdisciplinary communication, promotes a broad intellectual framework for problem-solving, and fosters the development of professional public health concepts and values.

d. The school of public health shall maintain an organizational culture that embraces the vision, goals and values common to public health. The school shall maintain this organizational culture through leadership, institutional rewards, and dedication of resources in order to infuse public health values and goals into all aspects of the school’s activities.

e. The school shall have faculty and other human, physical, financial and learning resources to provide both breadth and depth of educational opportunity in the areas of knowledge basic to public health. As a minimum, the school shall offer the Master of Public Health (MPH) degree in each of the five areas of knowledge basic to public health and a doctoral degree in at least three of the five specified areas of public health knowledge.

f. The school shall plan, develop and evaluate its instructional, research and service activities in ways that assure sensitivity to the perceptions and needs of its students and that combines educational excellence with applicability to the world of public health practice.

These characteristics are evident in the University of Michigan School of Public Health. The school is located in a regionally-accredited university, and the faculty have the same rights, privileges and status as other professional schools. The school’s faculty are trained in a variety of different disciplines, and collaboration both within the school (between departments) and within the university (with other university schools and colleges) is evident in the school’s research, teaching and service. This collaboration fosters interdisciplinary communication. The school has strong ties to the public health workforce in Michigan and beyond, and these linkages foster the development of professional public health concepts and values. The school’s policies and procedures align with its public health mission and vision. The school has resources to support all of its educational offerings, including professional master’s degrees and academic doctoral degrees in the five core areas of public health knowledge. The school has a well-developed system of planning and evaluation that is very responsive to student feedback and involves students at all levels and that responds to current and emerging public health practice needs.

1.0 THE SCHOOL OF PUBLIC HEALTH. 1.1 Mission.

The school shall have a clearly formulated and publicly stated mission with supporting goals and objectives. The school shall foster the development of professional public health values, concepts and ethical practice.

This criterion is met with commentary. The school’s mission statement encompasses three major functions of public health: education, research and service. The mission statement focuses on “health equity” and disadvantaged populations who suffer disproportionately from illness and disability.

The school’s mission statement is as follows:

The University of Michigan School of Public Health seeks to create and disseminate knowledge with the aim of preventing disease and promoting the health of populations worldwide. We are especially concerned with health equity and thus have a special focus on disadvantaged populations who suffer disproportionately from illness and disability. We serve as a diverse and inclusive crossroads of knowledge and practice, with the goal of solving current and future public health problems.

The school’s vision statement is as follows:

The University of Michigan School of Public Health will be the premier academic institution in public health recognized for the way it integrates research, teaching, service and practice in a diverse environment to develop effective solutions to public health problems.

The goals reflect a commitment to prepare public health leaders, conduct innovative research, partner with communities and public health organizations, serve as a valued resource and recruit and retain high-quality faculty and staff to support the mission. The school defines its goals and supporting objectives within four major functions by which the mission will be attained. These functions and goals follow:

1. Education:

a. Goal: To prepare leaders with the knowledge and skills to effectively prevent disease, assure delivery of health services, promote population health, and solve public health problems worldwide.

2. Research:

a. Goal: To conduct innovative research that leads to new approaches, expands basic knowledge, and leads to effective public health policies, programs, and technologies worldwide.

b. Goal: To partner with public health systems and community stakeholders to design and conduct relevant, collaborative research.

3. Service and Practice:

a. Goal: To partner with academic, government, practice, and lay communities to facilitate reciprocal learning and the application of scholarship that contribute to improving population health.

b. Goal: To serve as a valued resource in supporting the efforts of communities and public health organizations to address their priority health issues and challenges.

4. Faculty and Staff:

a. Goal: To recruit and retain a diverse, high-quality faculty and staff to support the mission of the School.

b. Goal: To support faculty and staff as they develop their careers as leaders in public health research, teaching, and service

There are sixteen objectives in the self-study that support the above goal statements. These objectives indicate the intent to increase quality in the functional areas of education, research, service and faculty/staff.

The first area of commentary, however, relates to the lack of established goals and objectives that address the school’s concern, articulated in the mission statement, with health equity and the special focus on disadvantaged populations who suffer disproportionately from illness and disability. When asked about how the school measures achievement of this component of the mission, school leaders and faculty stated that it is a guiding principle that is difficult to measure and noted that they struggle with this challenge. However, they note that health equity is reflected throughout the curriculum, and it was clear to the site visit team that health equity is well embedded in the curriculum and other school functions. For example, the school has research centers that are focused on reducing health disparities. Further, the school’s Center for Research on Ethnicity, Culture, and Health (CRECH) is a mentorship and training program that is responsible for leading the school’s response to dramatic changes in the racial and ethnic composition of the United States, and the center draws students and faculty who are specifically interested in health equity as a primary focus. Additionally, the dean made large investments in global health. Though the activities noted above do indicate that the school is taking steps to implement this aspect of the mission, the discrepancy between the mission statement and the defined goals and objectives that measure attainment of the mission leads to confusion and draws into question how effectively the goals and objectives measure achievement of the mission.

The second area of commentary relates to quantitative measures associated with some of the goals and objectives. While metrics are provided in tabular form, the objectives are not measurable in isolation from the metrics. They are not as specific and measurable as they would be if a model such as the SMART (Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Relevant, Timely) model for writing objectives were applied. Educational and service objectives, for example, use difficult-to-measure terms such as “expose,” “promote,” “strengthen” and “foster.” Faculty/staff objectives refer to “excellence” without explicitly defining the term. Overall, the metrics, provided in tabular format, support the objectives. However, a more systematic method to effectively measure goals could begin with writing objectives that clearly state the measures. For example, a SMART objective for the school’s Goal 1, Objective 2 could read, “Increase experiential learning in 2013 by 30% to ensure students have sufficient practice opportunities in the core areas of public health and in their area of specialization.”

In 2011, with the naming of a new dean, the school underwent a rigorous and systematic process to review and revise the mission, vision and values statements. The process included internal and external input and guidance. External guidance was provided by the Dean’s Advisory Board and the Alumni Board of Governors. Internal inputs were provided by a working group of deans and department chairs, faculty and students.

The school last defined its goals and objectives in 2006. In May 2012, the goals and metrics will be revised to support the mission. When asked about planned and past processes for establishing metrics and measuring success, faculty noted that a summit was conducted with 10 faculty and public health practitioners, and these stakeholders used a previously-defined Innovation Action Plan to define specific metrics. School leaders also noted that metrics are based on outcomes that can readily be measured and tied to data that can be feasibly collected.

There school would benefit from sharing its mission, goals, objectives and values more broadly. While the mission and core values are made public on the schools website, they have not been publicized in other forms of medium (eg, school brochure) and the school’s goals and objectives for supporting the mission have not been made publicly available. While faculty indicated to site visitors that they share these statements amongst the public health community, such as in school departments, in meetings and emails, the site visit team concluded that opportunities exist to further integrate programmatic mission, goals, objectives and values in public materials and all aspects of the school’s culture.

The core values were developed concurrently with the mission and vision statements, and they are published on the school’s website. The self-study states that the core values are integrated into teaching, research and service activities. Faculty who met with site visitors gave a number of examples of activities and initiatives that provide evidence of the school’s commitment to various core values. For example, in May 2012 the school will implement new models for teaching innovation that incorporate an interdisciplinary focus to support the core value, “excellence in innovation.”

1.2 Evaluation and Planning.

The school shall have an explicit process for evaluating and monitoring its overall efforts against its mission, goals and objectives; for assessing the school’s effectiveness in serving its various constituencies; and for planning to achieve its mission in the future.

This criterion is met. The school involves many constituents in the monitoring and evaluation process relative to the mission, goals and objectives. The school conducts an annual faculty retreat and utilizes standing and ad hoc committees to engage faculty, students and other stakeholders in the analysis, monitoring and revisions of the mission, goals and objectives. Faculty stated that it is a benefit that the school’s departments operate in a very autonomous fashion, but decentralized management makes monitoring and evaluation more challenging. The school is analyzing and identifying how to more

effectively coordinate and centralize evaluation efforts. As a result, the school assigned the evaluation role to a single individual as a core responsibility, and centralizes a number of monitoring and evaluation activities through the dean’s office.

The self-study document defines metrics for monitoring the school’s effectiveness in meeting the mission, goals and objectives. This includes target levels regarding the schools performance for the last three years. In the self-study, a diagram presents “Inputs,” which illustrate the process for involving constituents, and “Process,” which illustrates data sources and types. This diagram could be more effective if an additional column were added to illustrate “Outcomes,” which could indicate how evaluation results are used to make changes in the school’s operations.

When the site team asked for an example of how the school analyzes and uses evaluation data to enhance the quality of school programs, the school responded with specific areas they are evaluating, such as matriculation rates, graduation rates and student-faculty ratios (SFR). In all three cases, when the school identified data that did not meet targets or that otherwise seemed anomalous, the school instituted new policies, enhancing recruitment in specific areas and modifying policies on continuous enrollment, designed to rectify concerns.

The school has a structure for obtaining input and broad-based participation in evaluating and monitoring the mission, goal and objectives. Constituent groups, including faculty, staff, students, alumni and community partners, provide inputs on collaborations, establishing research centers, evaluating the school’s public profile, short and long-term issues, school priorities, promoting interaction among students and alumni, reviewing and recommending curriculum and degrees and recommendations for research policy. Also, ad hoc committees developed the strategic plan, report on ethics, a diversity statement and a school vision. The self-study describes each constituent group’s role and frequency of meetings.

When the site team asked students if they have sufficient opportunities to provide constructive feedback to the school regarding concerns and suggestions for improvement, they stated that the school queries them with surveys periodically and that faculty and staff members are very open to receiving feedback through an open door policy. Students feel comfortable giving informal feedback directly to faculty. Further, the dean conducts annual town hall meetings with students. If a student prefers to be anonymous, an online link on the school’s website provides an option for submitting anonymous feedback to faculty. Students stated that there is a high response rate to course evaluations and that faculty members do in fact incorporate student feedback into the courses. Overall, faculty members have a sincere interest in receiving feedback from students and in quality improvement of courses and programs.

The school used a systematic process for developing the self-study document, which included involvement by all relevant stakeholders. The effort began in 2010 when the school developed an Accreditation Committee comprised of faculty from five school departments, the associate dean for academic affairs, the assistant dean for finance, master’s and doctoral students, representatives from the Office of Public Health Practice and a local health department representative. The committee members were divided into work groups to focus on specific criteria. A cross-cutting fifth group addressed the practice and service criteria. The accreditation process was managed by a senior research staff member and a project coordinator. Information was shared via the CTools system. Internal and external communication was facilitated via the accreditation website, launched in spring 2011. Additionally, 53 students representing eight student organizations reviewed the self-study and provided feedback. Overall the self-study was well written and well organized.

At the time of the site visit, reviewers identified a concern regarding the need for more developed and integrated approaches to evaluation and planning. The school has clearly demonstrated a capacity for data collection and analysis, the connection between evaluation results and implementation of changes in operations and policy was less apparent. However, in its response to the site draft visit report, the school thoroughly described their comprehensive approach to the collection and utilization of data to improve the school and for decision-making.

1.3 Institutional Environment.

The school shall be an integral part of an accredited institution of higher education and shall have the same level of independence and status accorded to professional schools in that institution. This criterion is met. The University of Michigan School of Public Health (UMSPH) is an integral part of an accredited institution and has the same level of independence and status as all colleges and schools in the institution.

The University of Michigan, founded in 1817, is one of the first public universities in the United States. First located in Detroit, the university moved to Ann Arbor in 1837. Currently there are over 42,000 students and 5,700 faculty members on the Ann Arbor campus. The mission of the University of Michigan is to “serve the people of Michigan and the world through preeminence in creating, communicating, preserving and applying knowledge, art and academic values, and in developing leaders and citizens who will challenge the present and enrich the future.” The university has produced many distinguished graduates and is an impressive institution with many areas of academic strength and a rich array of resources and opportunities.

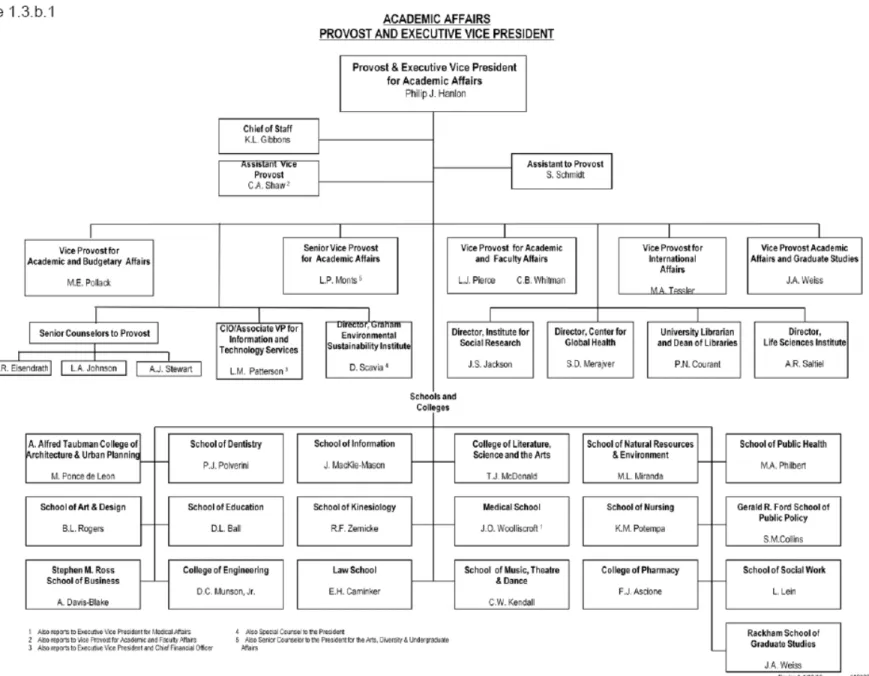

The UMSPH, founded in 1941, is one of 19 schools and colleges. There are two additional major initiatives offering resources and opportunities for the faculty of UMSPH, namely, the Life Sciences Institute and the Biomedical Research Core Facilities. Figure 1 presents the university’s organization.

The university is accredited by the North Central Association of Colleges and Schools, Higher Learning Commission, with the next accreditation to occur in 2019-2020. Within the school, there are four specific programs that are accredited by separate accrediting bodies: Industrial Hygiene (Accreditation Board for Engineering and Technology, next review 2012); Dietetic Program (American Dietetic Association, next review 2013); Preventive Medicine Residency Program (Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, next review 2012); and Masters of Health Services Administration (Commission on Accreditation for Healthcare Management Education, next review 2014).

The university is governed by a Board of Regents, with eight members elected in a biennial statewide process. The Regents are charged with “general supervision” of the university along with the control and direction of all expenditures from the institution’s funds.

The provost, the chief academic officer of the university, is responsible for all academic and budgetary affairs and reports directly to the president of the university. The deans of all 19 colleges and schools work with the provost in setting academic priorities and allocating monies for these priorities. The dean of the UMSPH has the same participatory role and degree of autonomy and responsibility as that of all other deans. The SPH dean is a member of the Academic Program Group (APG), convened by the provost and comprised of all deans and senior staff in the provost’s office. Within the APG, issues, such as budget, planning, facilities and development, are discussed.

University practices are guided by the University of Michigan Standard Practice Guide (SPG). This document provides information on the university’s general operating policies and procedures. This document outlines the university’s policies and procedures regarding personnel recruitment, selection and advancement, establishment of academic standards and information on services and facilities. There is opportunity for individual units to include sections in the SPG for matters pertinent to their particular operation.

1.4 Organization and Administration.

The school shall provide an organizational setting conducive to teaching and learning, research and service. The organizational setting shall facilitate interdisciplinary communication, cooperation and collaboration. The organizational structure shall effectively support the work of the school’s constituents.

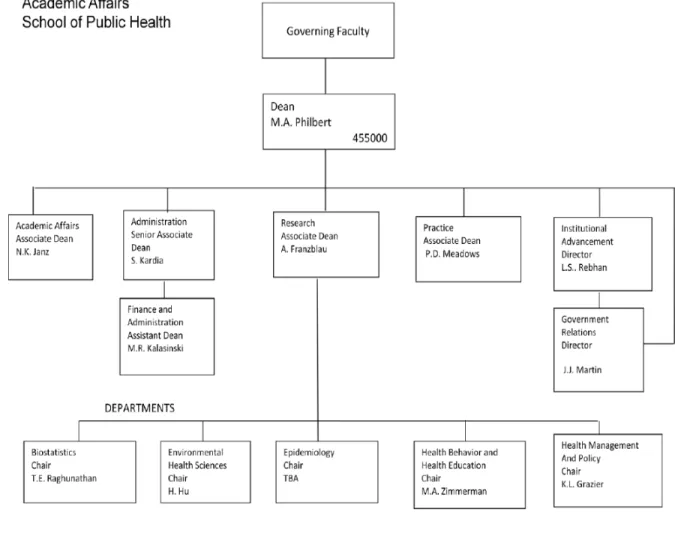

This criterion is met. The UMSPH is organized into five departments: biostatistics (BIOS), environmental health science (EHS), epidemiology (EPID), health behavior and health education (HBHE) and health management and policy (HMP). Each department is headed by a chair who reports directly to the dean. The dean is the chief executive officer of the school and has administrative responsibility for the school, in concert with the department chairs and the associate and assistant deans. There are four associate deans (administration, academic affairs, research and practice), an assistant dean (finance and administration) and seven directors (academic affairs, information technology, government relations, advancement, marketing and communication, innovation and social entrepreneurship, executive education and life-long learning and global public health) who carry out administrative functions. The associate deans are ex-officio members of the UMSPH-elected Executive Committee (six faculty members plus the dean), and it is here that policy, budget and personnel issues for the school are handled. Figure 2 presents the school’s organization.

The self study provided several examples of how the school supports interdisciplinary activities. These include: interdisciplinary programs within the school and/or its 32 research centers, joint faculty appointments, joint degrees, cross-listed courses, collaborative research, four interdisciplinary certificates and a biennial Public Health Symposium.

The school is committed to fair and ethical dealings in all its activities, and policies are written and accessible to all the constituents of the school. All who engage in research at UMSPH must complete the University’s Program for Education and Evaluation in Responsible Research and Scholarship as well the appropriate HIPPA training module. Site visitors learned during the discussions with faculty that a decision has been made to require all students in the school to be trained in the Responsible Conduct of Research Course.

The importance of ethics is communicated at student orientation and in the Student Handbook and via emails. Incoming students are required to complete an online academic ethics workshop during their first semester of enrollment. In 2008, the UMSPH adopted a Diversity Statement that is used to guide the conduct of all of the members of the school’s community.

There are clear policies for student grievances, and the self study indicated that only two grievances in the three years reported had gone through a formal process, and each of these was filed through the Rackham Graduate College, indicating that the student filing each grievance was either an MS or PhD

student. The school indicates that student grievances and complaints are more likely to be addressed at the department level and are typically resolved before getting into the formal process.

Figure 2. University of Michigan School of Public Health Organizational Structure

1.5 Governance.

The school administration and faculty shall have clearly defined rights and responsibilities concerning school governance and academic policies. Students shall, where appropriate, have participatory roles in conduct of school and program evaluation procedures, policy-setting and decision-making.

This criterion is met. The administration and faculty of UMSPH have clearly defined rights and responsibilities regarding the governance and academic policies of the school. The key administrative and governance structure of the school includes the Office of the Dean, the Executive Committee, Department Chairs, various faculty committees and the Student Government Association. Governance policies and procedures are outlined in the Faculty Handbook.

The self-study provides descriptions of the school’s governance and committee structure and processes as they affect general school policy development, planning, budget and resource allocation, student recruitment, admission and award of degrees, faculty recruitment, retention, promotion and tenure, academic standards and policies and research and service expectations and policies. The school governance includes the following standing committees:

• Advisory Committee on Academic Programs (ACAP) • Advisory Committee on Academic Rank (ACAR) • Affirmative Action Committee

• Diversity Committee • Executive Committee • Practice Advisory Council • Research Council • Dean’s Advisory Board • Public Health Alumni Society

Policies and procedures for standing committees were made available for review by the site visit team, and the functions of the standing committees are described in appropriate detail to make an assessment. Tables in the self-study document list current members on the various committees.

During the site visit, there were many examples given of faculty engagement in governance of the school. The site visit team observed that the school has appropriate checks and balances between senior leadership, department chairs and faculty committees. In particular, the site visit team heard faculty, on multiple occasions, praise the role of school-wide faculty meetings as not merely informational but discussion-oriented and consultative before policies and actions were implemented. Another key observation was a governance structure that faculty noted promoted a collective good and transdisciplinary collaboration with a school-wide orientation, rather than constituent-oriented politics focused on departments – a stark contrast noted by some UMSPH faculty from their experience at other SPHs and professional schools. The approach that fostered this orientation was not only structural but philosophical; the dean referred to school governance as a “matrix model” of leadership, with information brought to the Executive Committee, departments and other governance components at the same time. Students play an important role in the structure and function of the governance of UMSPH and are appropriately represented on school and university committees. It was clear from the site visit that student input is sought and highly valued. The students’ spoke of UMSPH as a student-centered school and the faculty and staff echoed this philosophy in both observable actions and words.

1.6 Resources.

The school shall have resources adequate to fulfill its stated mission and goals, and its instructional, research and service objectives.

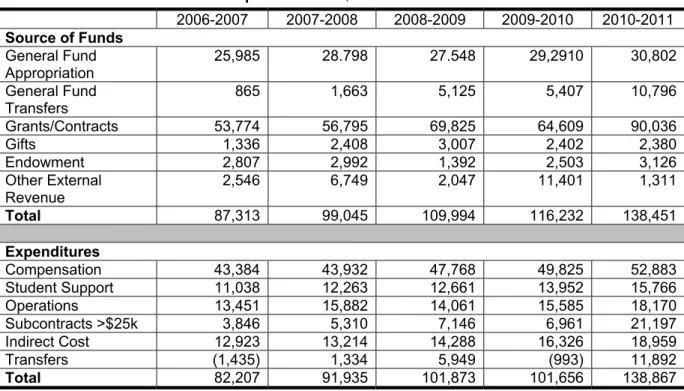

This criterion is met. UMSPH documents a strong fiscal position with an outstanding resource base to carry out its mission. It is financially independent and has authority over its resources, and operating budget allocations from the university are deemed appropriate and fair. The school has robust and growing revenue sources from grants, contracts and indirect cost recovery. Table 1 presents the school’s budget for the past five years. The vast majority of tuition flows to the academic units, which receive 75% of tuition funds for UMSPH students and 25% for students from other university schools and colleges who enroll in SPH classes. The indirect cost recovery rate is 54.5%, and the indirect cost recovery follows the direct costs. The policy on distribution of indirect costs fosters collaboration across departments in the school as well as cross-school collaborations. The school’s leadership and faculty are proud of this fiscal framework.

Table 1. Sources of Funds and Expenditures in $000

2006-2007 2007-2008 2008-2009 2009-2010 2010-2011

Source of Funds General Fund

Appropriation 25,985 28.798 27.548 29,2910 30,802

General Fund

Transfers 865 1,663 5,125 5,407 10,796

Grants/Contracts 53,774 56,795 69,825 64,609 90,036

Gifts 1,336 2,408 3,007 2,402 2,380

Endowment 2,807 2,992 1,392 2,503 3,126

Other External Revenue

2,546 6,749 2,047 11,401 1,311

Total 87,313 99,045 109,994 116,232 138,451

Expenditures

Compensation 43,384 43,932 47,768 49,825 52,883

Student Support 11,038 12,263 12,661 13,952 15,766

Operations 13,451 15,882 14,061 15,585 18,170

Subcontracts >$25k 3,846 5,310 7,146 6,961 21,197

Indirect Cost 12,923 13,214 14,288 16,326 18,959

Transfers (1,435) 1,334 5,949 (993) 11,892

Total 82,207 91,935 101,873 101,656 138,867

In 2011, the school‘s faculty complement was 115 core and 23 secondary and adjunct faculty. This size faculty was deemed sufficient to provide an acceptable student faculty ratio of roughly eight to one. The school exceeds minimum expectations for faculty resources and for student-faculty ratios in core public health knowledge areas. In addition to an impressive number of high caliber faculty, the school also maintains an appropriate staff of 423 individuals to support the education, research and service mission of the school, including 46 post-doctoral fellows. All staff have a specific statement of roles and responsibilities guiding their activities and assignment.

The school maintains impressive space for its activities, and since the last accreditation, has added $70 million in capital projects. Computing and library facilities are substantial. The school’s IT infrastructure is more than sufficient to support the research mission of the school, and the distance education platform, and support for it was praised by faculty and staff as superb.

The university has demonstrated a commitment, through its new Third Century Initiative and a recent provost’s office initiative to hire 100 new faculty across the university, to supporting the current and future needs of the SPH. The site visit team observed in its conversation with the provost a high regard for the work of the SPH and a clear commitment to its continued success.

In summary, UMSPH has an excellent base of resources to implement its mission; the strong state of the program’s resources is notable in particular considering the volatility of the global and US economy and the dramatic economic changes in the state of Michigan since the last site visit.

2.0 INSTRUCTIONAL PROGRAMS.

2.1 Master of Public Health Degree.

The school shall offer instructional programs reflecting its stated mission and goals, leading to the Master of Public Health (MPH) or equivalent professional masters degree in at least the five areas of knowledge basic to public health. The school may offer other degrees, professional and academic, and other areas of specialization, if consistent with its mission and resources.

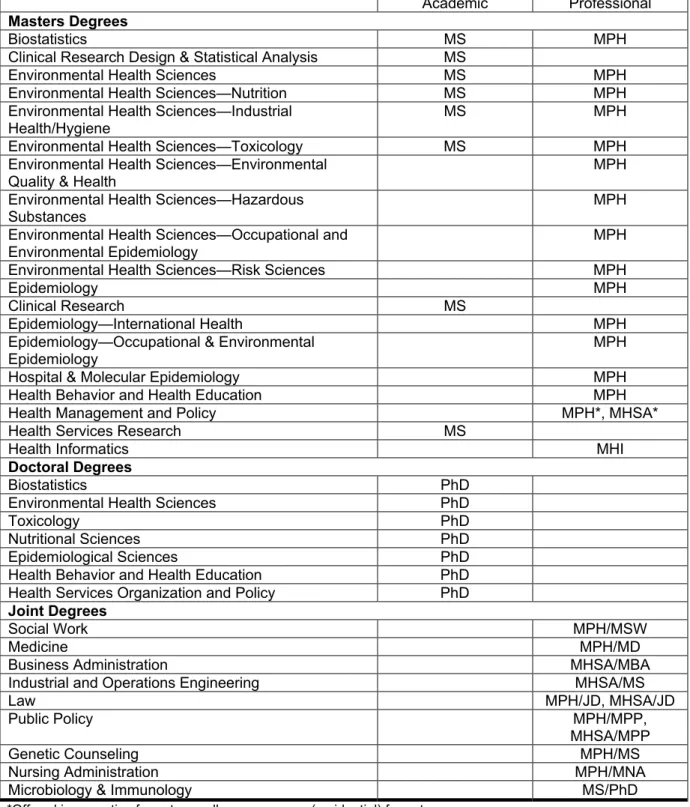

This criterion is met. Each of the school’s five departments offers at least one MPH degree and one PhD degree. The Department of Environmental Health Sciences offers multiple concentrations for its MPH and PhD degrees. Four departments (biostatistics, environmental health sciences, epidemiology and health management and policy) offer academic MS degrees, and the Department of Health Management and Policy offers a professional MHSA degree, with curricular requirements that are nearly identical to the department’s MPH. Finally, the school offers a non-public health professional degree, the master of health informatics, and a number of joint degree programs that allow students to pursue a degree in another University of Michigan school while pursuing the MPH, MS or MHSA degree. A clearly defined set of curricular requirements applies to each degree. Table 2 presents the school’s degree offerings.

Table 2. Degrees Offered

Academic Professional

Masters Degrees

Biostatistics MS MPH

Clinical Research Design & Statistical Analysis MS

Environmental Health Sciences MS MPH

Environmental Health Sciences—Nutrition MS MPH

Environmental Health Sciences—Industrial

Health/Hygiene MS MPH

Environmental Health Sciences—Toxicology MS MPH

Environmental Health Sciences—Environmental

Quality & Health MPH

Environmental Health Sciences—Hazardous

Substances MPH

Environmental Health Sciences—Occupational and Environmental Epidemiology

MPH

Environmental Health Sciences—Risk Sciences MPH

Epidemiology MPH

Clinical Research MS

Epidemiology—International Health MPH

Epidemiology—Occupational & Environmental

Epidemiology MPH

Hospital & Molecular Epidemiology MPH

Health Behavior and Health Education MPH

Health Management and Policy MPH*, MHSA*

Health Services Research MS

Health Informatics MHI

Doctoral Degrees

Biostatistics PhD

Environmental Health Sciences PhD

Toxicology PhD

Nutritional Sciences PhD

Epidemiological Sciences PhD

Health Behavior and Health Education PhD Health Services Organization and Policy PhD Joint Degrees

Social Work MPH/MSW

Medicine MPH/MD

Business Administration MHSA/MBA

Industrial and Operations Engineering MHSA/MS

Law MPH/JD, MHSA/JD

Public Policy MPH/MPP,

MHSA/MPP

Genetic Counseling MPH/MS

Nursing Administration MPH/MNA

Microbiology & Immunology MS/PhD

2.2 Program Length.

An MPH degree program or equivalent professional master’s degree must be at least 42 semester credit units in length.

This criterion is met. All MPH degrees require completion of at least 42 semester credits; many MPH programs require 48 to 60 semester credits. The university defines one credit as one weekly class contact hour, with the expectation that each hour of class time will be accompanied by two to three hours spent in reading and preparation. Laboratory courses may have differing contact hour requirements based on the nature of the coursework.

2.3 Public Health Core Knowledge.

All professional degree students must demonstrate an understanding of the public health core knowledge.

This criterion is met. For each of the professional master’s degree programs, students must take a set of required courses, called the Breadth, Integration, and Capstone (BIC) courses, which cover the five core areas of public health knowledge. Students may choose to take the courses designated as “primary” BIC courses or may choose from a list of “secondary” BIC options that have been designated as appropriate and equivalent substitutes for the courses on the primary list. Students with strong academic preparation in biostatistics and epidemiology may qualify to take an exemption exam in one or both areas during the orientation period. Similarly, site visitors learned about a new self-assessment strategy for identifying matriculating students with weaker quantitative skills for early identification and remediation of math skills. There is also a procedure for students to seek approval to take an alternate course, which is not listed as a primary or secondary BIC option, for each core knowledge area.

The school’s list of primary BIC courses reflect its stated mission and goals in the five core public health knowledge areas: Introduction to Biostatistics (BIOSTAT 503); Principles of Environmental Health Sciences (EHS 500); Strategies and Uses of Epidemiology (EPID 503); Survey of the U.S. Health Care System (HMP 602); and Psychosocial Factors in Health-Related Behavior (HBHE 600). These five courses total 16 credit hours. The self-study provided a table that mapped the core MPH competencies to these primary BIC classes, and reviewers verified that the primary BIC courses align well with the designated MPH core competencies.

Site visitors also reviewed the school’s analysis of competency coverage in the secondary BIC options. The approved options for biostatistics, health management and policy and social and behavioral sciences satisfy all core MPH competencies. Site visitors also clarified that one of the listed secondary BIC options, Applied Statistical Methods (Statistics 400), is an upper-level undergraduate course offered by the College of Literature, Science and the Arts, but provides an alternative pathway to the exemption exam in biostatistics and is rarely utilized.

At the site visit there was a concern related to the fact that not all of the approved BIC options fully cover the core competencies in the areas of environmental health sciences and epidemiology. A specific analysis of the courses and their alignment with core MPH competencies follows. This analysis was based on the school’s own competency analysis, presented in the self-study appendix, and on site visitors’ additional review of syllabi for the courses in question.

• Principles of Risk Assessment (EHS 508) satisfies environmental health sciences MPH core competencies one through five and seven, but not six and eight.

• Introduction to Occupational and Environmental Health (EHS 550) satisfies competencies one through seven, but not eight.

Environmental health competency six is “Explain the general mechanism of toxicity in eliciting a toxic response to various environmental exposures” and competency eight is “Develop a testable model of environmental insult.” Site visitors noted that the one-credit elective course entitled Topics in Environmental Health Sciences (EHS 688) satisfies both competencies six and eight; this course could be added to the options in order to potentially satisfy all of the competencies. However, the school’s response to the draft site visit report outlined an error in the self-study, accidentally omitting competency #8 from the set of competencies covered by EHS 550. Thus, this BIC course does cover all competencies. The school’s response also documented that EHS 508 has been removed as a BIC option, and a new integrative BIC course (PH 600) is now available (referenced below) that provides additional EH content.

• Principles and Methods of Epidemiology (EPID 601) satisfies epidemiology MPH core competencies one through four and six through ten, but not competency five.

• Epidemiology majors take EPID 600, which satisfies competencies one through four and six through 10, but not competency five.

Epidemiology competency five is “Comprehend basic ethical and legal principles pertaining to the collection, maintenance, use and dissemination of epidemiologic data.” Site visitors noted that the new course in responsible conduct of research and ethics, which the associate dean for research indicated will be required of all students during the upcoming academic year, would likely address competency five. The school’s response documents that Responsible Conduct of Research and Scholarship (RCRS) Certification is a graduation requirement for all SPH students. The mandatory training was initiated in 2011-12 at SPH, and the eight modules provide content that meet or exceed all NIH requirements for researchers and address epidemiology competency #5.

MPH and MHSA students in the Department of Health Management & Policy address the core area of social and behavioral sciences through two departmental required courses rather than through the standard BIC courses. Site visitors verified that the two courses do, in fact, cover all defined MPH core

social and behavioral sciences competencies. The Health Services System I (HMP 600) satisfies competencies one through four, six through seven and nine and 10; Introduction to Public Health Policy (HMP 615) satisfies competencies two through 10; together, these two courses satisfy all of the social and behavioral sciences competencies.

An exciting curricular innovation is the development of a new four-credit integrative course entitled Cross-Disciplinary Approaches to Public Health Challenges (PUBHLTH 600) which aims to address competencies across the core disciplines of environmental health, health services administration and social and behavioral sciences. This course emphasizes the added value of integration of core knowledge and use of case studies for problem solving and communication. The course is being offered for the first time during the winter semester of 2012, and there will be a two-year pilot phase during which students can choose to take the integrative course or the three separate core course requirements from the BIC primary and secondary courses. The mid-term evaluation of this course was highly positive, with more than two-thirds of students indicating that they learned more or much more than in other classes in developing skills for multidisciplinary thinking and considering a broader context. Students were also extremely positive about the course organization, professors’ interactions and the experience with group work and discussions.

At the time of the site visit, the school had not yet formally analyzed the syllabus for the integrative course to ensure that all core competencies in the three disciplinary areas are covered, and because of the complexity of the course, site visitors were not able to independently analyze or verify the coverage. In order for the integrative course to function as a substitute for three separate classes, the school must ensure that there are no gaps in competency attainment. Site visitors noted that the pilot phase could provide an opportunity to evaluate the success of the integrative approach by randomizing students to take the integrative course versus the primary BIC options. The school’s response documented that senior faculty have assessed/analyzed PUBHLTH 600 and ensured that it has content that covers all core competencies for environmental health sciences, health management and policy and social and behavioral sciences.

2.4 Practical Skills.

All professional degree students must develop skills in basic public health concepts and demonstrate the application of these concepts through a practice experience that is relevant to the students’ areas of specialization.

This criterion is partially met. The school’s practicum, called the internship, offers students an opportunity to apply knowledge and skills learned in coursework to real world experience in local public health agencies and community-based organizations. The school attempts to place students in appropriate internships that support the students’ desired skills, knowledge and hands-on experience.

The school’s structure for placing students in internships to gain practice skills includes a Practice Council, which is comprised of representatives from all school departments and from community-based organizations. The council is charged to advise students on practice activities in the community, to identify training and competencies needed by community partners and to keep the school updated on skill needs in the field. The council acts as liaison between faculty members and students and the community, with a primary focus on local and state health departments.

In EHS, EPID and HBHE, the student is responsible for finding a practicum site and arranging it, and the school provides resources to guide them in finding and funding their internships. In HMP, students complete a survey of their interests and are placed with a site by the Residential Master’s Committee. Students in EHS, EPID, HBHE and HMP are required to have practice experience as a condition of graduation and are required to work a minimum of 320 hours. Overall, the school does community outreach annually to secure new internship sites. Each department has a different process for approving internship sites, and all internships are approved by the student’s academic advisors. Students are responsible for completing a field placement agreement to define desired learning objectives and competencies. This form is also used for logistics (eg, contact information).

The first area of concern relates to the fact that there is no required internship/practical experience for BIOS MPH students. Only five students have enrolled in the BIOS MPH during the past three years. Since the program is very small, the department has not developed an internship system that differs from the research-based practicum offered to BIOS MS students. All BIOS MPH students, like BIOS MS students, are required to complete a project-based course (BIOSTAT 699), which requires students to write and present reports on final results of case studies.

The internship process is decentralized, and each department is responsible for oversight of internships. Each employs a different process and criteria for determining whether an internship placement is a good match for students. The EHS, EPID, HBHE and HMP departments each have a departmental internship handbook available to students. Each department also has its own database or list of potential preceptors. A centralized school-wide database to track internships is currently in development. The school plans to use the database to list internship sites and preceptor information. At this time there are no plans to add a competency, skill, monitoring and evaluation component to the database (eg, tracking students’ performance or cataloging students’ work products).

Most departments do not have a formal process for selecting preceptors, for determining if they are qualified and for evaluating them, though all have more informal means, including personal contacts and individual vetting by faculty and staff, that they use to make individualized assessments. HMP is the only department that has a formal evaluation in place to measure preceptor qualifications. In 2012, two

additional departments will implement a preceptor evaluation. In all departments, each student’s faculty advisor serves as a first point of contact if issues arise. Also, the student contacts the departmental internship coordinator for a resolution if the preceptor is not doing their job or issues arise. In HMP, the Residential Master’s Committee is responsible for securing the internship site, setting expectations for preceptors and students and monitoring completion of the practicum. The faculty advisor is responsible for issues that arise during the internship. The on-site supervision is provided by the preceptor.

To monitor and evaluate internships, academic advisors follow up with students three times (beginning, mid-point and end) during the internship to identify whether students are meeting their internship objectives. In EPID, EHS, HBHE and HMP, students are required to write a one page abstract and present a poster on the internship experience at the school’s annual poster session. In EPID and EHS, students are required to complete an evaluation of the internship experience. HBHE requires students to create a reflection document in their e-portfolio on departmental competencies achieved through the internship experience. HMP requires students and preceptors/supervisors to complete a survey. Survey results are reported on the department’s intranet site and made available to future students. All departments (except BIOS) require the student to write a report, write a reflection paper, complete a self-evaluation and present a poster on the internship experience at the school’s annual poster session. The overarching concern relates to a lack of systematic processes for measuring and evaluating practicum learning as it relates to competencies and learning objectives that students are expected to achieve during their internship experience. This includes a lack of clear statement about who, when and how the evaluations are reviewed and what is done with the results. While the site team realizes these processes are decentralized and handled in the departments, a consistent structure is not in place within departments. There is not a consistent process to ensure that the student’s internship competencies and learning objectives are achieved and assessed and that all evaluation results are reviewed and communicated to the student with feedback for improvement.

Additional concern relates to the need for attention to avoiding clinical and research-based placements. While such placements do sometimes offer the type of applied public health practice experience required by this criterion, clinical and research placements must be used sparingly and only in cases where the spirit of the practice requirement is explicitly verified. The self-study states that some students do research as a practicum, whereas the intent of the practicum is to gain experience outside the school. The school must ensure that the practicum experience is truly a practice-based, applied learning opportunity that transcends the academic environment and allows interaction with and mentorship from practitioners who are not full-time faculty members.

The final area of concern relates to the policy of granting waivers to selected students in HMP and EPID. The school does not require a practicum for HMP students who are concurrently enrolled in an MD program, or for EPID students who enter with a prior doctoral degree (eg, MD, DDS). Faculty explained that in both cases, these students’ clinical practice experience serves to ensure that they have experience applying skills outside the classroom. In the case of HMP, faculty note that requiring a practicum would force students to remain in the program longer than desired and would make the MPH program unattractive to those who are concurrently completing an MD. Clinical experience, however, is not an appropriate basis for a waiver, as it does not uniformly translate to public health practice experience. The school does not provide evidence of individualized, competency-based criteria for internship waivers for these students.

2.5 Culminating Experience.

All professional degree programs identified in the instructional matrix shall assure that each student demonstrates skills and integration of knowledge through a culminating experience. This criterion is met. A culminating experience is required for each professional degree program, but the required experiences vary by department. Each department requires a capstone course associated with the culminating experience for its professional degree programs. The culminating experiences across the departments reflect the achievement of students’ skills and integration of knowledge in multifaceted ways. In particular, the e-portfolio systems utilized by the Departments of Health Behavior and Health Education and Health Management & Policy are innovative and provide integrative tools not only for a student’s current degree program but also for their future professional use and development.

The Department of Health Behavior and Health Education utilizes the e-portfolio and students take the capstone course (HBHE 669) each semester. There is an HBHE MPH Handbook which provides a detailed overview of curriculum, internship and capstone requirements. With supervision by their academic advisors, MPH students show that they have achieved competencies, completed coursework and demonstrated service, practice and professional development via the completed e-portfolio. Students work incrementally on their e-portfolio throughout their two-year program. In addition, the MPH/MS dual degree in Health Behavior and Health Education and Genetic Counseling requires a master’s thesis or paper in addition to the e-portfolio.

MPH students in the Department of Epidemiology are required to take a capstone course in their specialty area (either EPID 659, EPID 656 or EPI 665), conduct an analysis of epidemiologic data, prepare a written report and present a poster of their work. Expectations are detailed in the Department of Epidemiology MPH Student Handbook, and students are supervised by either their academic advisors or a faculty advisor with expertise in the student’s topic. The analysis is intended to integrate with the student’s summer internship.

For MPH students in the Department of Environmental Health Sciences, the course entitled Professional Perspectives in Environmental Health (EHS 600) is required and completed during the second semester of the second year. Students work in small groups to prepare a briefing for a speaker, develop key questions and lead classroom discussion. The intent is to use and integrate their summer internship experiences as learning tools in achieving competencies. All students present a poster from their internships during semester after completion. The EHS Field Experience Handbook outlines internship requirements. The faculty instructors for the capstone course advise and evaluate student performance in their course.

The Department of Health Management & Policy requires MPH and MHSA students to complete one of two possible capstone courses. Students taking Applied Health Policy Analysis (HMP 664) perform policy analyses and present their findings. Students taking Case Studies in Health Services Administration (HMP 682) address issues in healthcare delivery and proposed solutions and alternative strategies. In addition, completion of the m-portfolio throughout the two-year period demonstrates that students have gained competences. Advisement is by the academic advisor.

MPH students in the Department of Biostatistics take the BIOSTAT 699 course entitled Design and Analysis of Biostatistical Investigations. In this structured course, students critically review journal articles, participate in discussion and work on three to four applied data analysis projects for which they prepare intermediate and final oral and written reports. The projects help the students integrate and demonstrate competencies achieved throughout their curriculum. The policies for this culminating experience are described in the course syllabi and the end products are evaluated by the course instructors.

2.6 Required Competencies.

For each degree program and area of specialization within each program identified in the instructional matrix, there shall be clearly stated competencies that guide the development of educational programs.

This criterion is partially met. The school identifies 57 core competencies that all MPH students are expected to attain. The school also identifies specific competencies for each concentration in the MS and PhD degrees and most, but not all, MPH concentrations. The school has mapped the core competencies to all core MPH course options discussed in Criterion 2.3. The school also mapped core competencies to the required coursework for each concentration, though no similar map links the courses required for the concentration to the specific competencies defined for each concentration.

The concern relates, first, to the need for further implementation of the competency framework as the guiding force for the school’s curriculum. Most syllabi do not list learning objectives or easily map to competencies, though some syllabi list “course objectives” that may or may not be stated in measurable terms. Indeed, while some course syllabi are very well-developed in terms of articulating the relationship

between course activities, learning objectives and competencies (eg, EHS 601), syllabi are inconsistent across departments and, to a lesser extent, within departments. Few syllabi provide evidence that activities are connected to competency-building, and conversations with faculty during the site visit support the assertion that competency mapping is less explicit for MPH concentrations than for core MPH classes and least explicit for the academic degrees. The interpretive language for this criterion states, “Competencies should guide the curriculum planning process and should be the primary measure against which student achievement is measured.” Neither the written evidence submitted with the self-study and appendix nor the on-site conversations with faculty and students supported the assertion that competencies are central to student curricula in the degree programs offered by the departments of biostatistics, environmental health sciences or epidemiology.

Additional concern relates to the fact that, while the Department of Epidemiology offers four options for the MPH, including concentrations in international health, occupational and environmental epidemiology and hospital and molecular epidemiology (in addition to the general epidemiology MPH), it has not defined competencies for the concentrations nor has it mapped the required concentration coursework (typically two to four courses) to competencies.

The HBHE and HMP departments present strong evidence of the centrality of competencies, particularly for masters degree students. As discussed in Criterion 2.5, both departments require students to complete electronic portfolios that are framed in terms of the defined competencies, and students and faculty were well-versed in the competencies and their relationship to the curriculum.

Another concern, however, relates to the definition of competencies in the Department of Health Management and Policy. The department uses the same set of competencies for all of its master’s degrees: the MPH, MHSA and MS. While the MPH and MHSA degrees have very similar curricula, the required coursework for the MS differs from the other degree programs in several areas. MS students are not required to take coursework in accounting (though they do take a course in health care cost-effectiveness that is not required for MPH and MHSA students), organizational theory or law, and they complete courses that MPH and MHSA students do not complete in economics. Examination of the competency list provided with the self-study suggests that the competencies that guide the MPH and MHSA curricula do not appear similarly well-matched to the MS degree.

Departments have primary responsibility for competency development and mapping, but the SPH Accreditation Committee played an advisory and review role, including making suggestions which were later addressed by the departments. The Accreditation Committee also took the lead in developing and mapping the MPH core competencies, beginning with the complete list of competencies developed by the Association of Schools of Public Health.

2.7 Assessment Procedures.

There shall be procedures for assessing and documenting the extent to which each student has demonstrated competence in the required areas of performance.

This criterion is met. Each department has processes in place, beyond tracking course grades, for monitoring and evaluating student progress in achieving competencies.

In the Department of Biostatistics, each student meets on an annual basis with the academic advisor. Together, the student and advisor evaluate the student’s performance on a Likert scale, and the advisor writes a “progress letter.” Other metrics include performance on qualifying exams and time to achieve milestones within the curriculum.

In the Department of Environmental Health Sciences, there is a Professional Degree Committee that reviews student progress. Doctoral students are evaluated with an annual progress report based on written and oral exams, doctoral student seminars, presentations of proposals, and work in progress. The department also has implemented an exit competencies survey for all graduates.

In the Department of Epidemiology, MPH students are assessed on their grades and the quality of the written report of their research projects (culminating experiences). Doctoral students have an annual review based on their written exams, presentation of proposal and work in progress. Students must demonstrate mastery of integrated competencies prior to undertaking their summer field placements. Prior to receiving a data set for analysis, students must demonstrate competencies in data management. The Department of Health Management & Policy has implemented a comprehensive competency model. A master’s student first performs a self-assessment and then reviews the model with his advisor. This is followed by monthly meetings with the advisor to review the student’s competency model progress; the student starts an e-portfolio in the second semester, which includes a resume and description of goals. Each semester, the student’s progress is evaluated either by the residential master’s or the executive master’s committee. The student’s internship is evaluated by the preceptor. HMP doctoral students are assigned an advisor with whom they regularly meet. Progress for HMP doctoral students is assessed via competency exams, oral exams and dissertation progress.

Student progress is assessed in the Department of Health Behavior and Health Education using the e-portfolio, which is organized by competencies. Students are assigned an advisor who monitors progress and students use the e-portfolio to check their own progress in achieving competencies and add their resumes, posters and other products to it. During the second semester, students are asked to outline competencies to achieve during their summer internships. The e-portfolio subsequently is used for reflection and to add new competencies and is tied into the capstone course. During the last semester,

the student uses the e-portfolio as a professional portfolio. Doctoral students are assigned an advisor with whom they regularly meet and progress is assessed via competency exams, oral exams, and dissertation progress.

The self-study documents graduation rates exceeding 90% for master’s students and over 75% for doctoral students in most departments. There are some departments with small numbers of doctoral students which results in some graduation rates lower than 70%, but overall rates for each degree meet this criterion’s expectations.

Surveys of employment status at six months post-graduation have high response rates and indicate a high percentage of graduates with job placements. Over 80% of graduates have jobs by six months after graduation. Site visitors’ meeting with alumni revealed a very high level of satisfaction with the skills and knowledge attained during enrollment; they noted that the skills and abilities they attained allowed them to be hired into gratifying and meaningful positions soon after graduation. Data on employer satisfaction with graduates’ training is similarly favorable, but the number of employers completing surveys has declined over the past three years.

2.8 Other Professional Degrees.

If the school offers curricula for professional degrees other than the MPH or equivalent public health degrees, students pursing them must be grounded in basic public health knowledge.

This criterion is met. The school lists one degree program as an “other professional degree.” This is a new program slated to begin in fall 2012 as a joint degree program between the school and the UM School of Information. The degree is a Master of Health Informatics (MHI).

The site visit team noted that the required curriculum far exceeded this criterion’s expectations of coverage of general public health knowledge in epidemiology, biostatistics, social and behavioral sciences, and health policy; however, there was no identifiable content in environmental health sciences in the degree curriculum. The site visitors learned that the school believed that it was not required to cover all core public health content areas in this degree program. While the curricular requirements provide a greater depth of basic public health knowledge in general—students complete MPH core courses in four of the five core knowledge areas—the lack of exposure to any ideas or themes relating to environmental health sciences constitutes a deficiency in the school’s ability to ensure that these students are grounded in basic public health knowledge. The school’s response to the draft site visit report acknowledged this deficiency and documented that effective immediately, environmental health content has been incorporated into two courses (all students must take one of the two) in the MHI curriculum.

2.9 Academic Degrees.

If the school also offers curricula for academic degrees, students pursuing them shall obtain a broad introduction to public health, as well as an understanding about how their discipline-based specialization contributes to achieving the goals of public health.

This criterion is partially met. The concern pertains to the academic degrees in biostatistics and in environmental health sciences, which do not consistently provide a “broad introduction to public health.” In biostatistics, where both the MS and the PhD academic degrees are awarded, students are required to take courses in epidemiology. Students must also select a “cognate area” in which to take classes. The site visit team learned that epidemiology is often chosen as the cognate area, but, over the years, all core public health knowledge areas have been selected as cognate areas. Cognate area selection on an individual basis does not assure a broad introduction to public health for the students. Academic degree students in EPID may also be exposed to introductory themes from public health areas other than their own during the weekly departmental seminars. However, the seminars are not required, and their content has not been systematically planned to ensure that they provide a broad introduction to public health. In EHS, academic degree seeking students are required to take courses in both epidemiology and biostatistics. They also take a “Topics in Environmental Health” course, which may cover other areas of public health, but, as above, the content has not been systematically planned to ensure that it provides a broad introduction to public health. One of the MS degrees in EHS does require a course in Principles of Community Air Pollution, which may have public health policy implications and expose students to additional public health knowledge, but this course is not required for the other academic degrees. In a discussion of the PhD program in epidemiology, the site team learned that it is rare that the doctoral program accepts students without a MPH degree, and EPID PhD students are required to take biostatistics as well as a seminar series which includes many presentations with public health content. Further, the site team was told that all EPID dissertations must include consideration of the public health implications of the research, and site visitors verified that this requirement is clear and explicit in documentation on the website where the dissertation’s written prospectus is defined.

The doctoral program in HBHE requires epidemiology and biostatistics in addition to four doctoral seminars wherein the students acquire a public health orientation.

In health management and policy (HMP), students in the MS in health services research program take epidemiology, biostatistics, public health program evaluation and public health policy. HMP PhD degree students are required to take epidemiology, biostatistics and doctoral seminars in health policy and health services and systems research. The site team was told that these seminars focus on major interdisciplinary public health issues.