Reader Responsibility in Knowledge Organisation

Readers between Reference Books, Commonplace Books,

Wikipedia, and Pinterest

Lea Maria Ferguson (B.A.), s1283464 Master’s Thesis

Book and Digital Media Studies, Leiden University

First reader: Prof. A. H. van der Weel Second reader: P. Verhaar

Date of Submission: 1st July 2015

Abstract

The possibilities for exerting reader responsibility as an expression of democracy on the Internet are manifold. Reader responsibility may be seen as the process of finding,

accessing, making sense of, interpreting, judging, and putting to use the information that can be gained through reading, and thereby turning it into knowledge. However, the

'democratisation discourse' on the Internet is often (mis-)used to promote mere economic aims, even under the guise of ‘digital socialism’. This is not only an obstacle to

understanding reader responsibility and the process of reading, but also to gaining access to knowledge and making use of information resources successfully and effectively. It is encouraging to see though that the potential presented by reading and writing is (partly) being implemented. Historically, this occurred through commonplace and reference books, and currently it is happening through Pinterest and Wikipedia - despite some problematic economic and political circumstances. Embracing the responsibilities of the reading process will be conducive to developing the political potential of reading and as such be beneficial for society at large. Despite the connected and implied struggles of this, it is important to realise that readers can only turn information into knowledge and utilise it in their lives by being active and informed.

Keywords

Contents

Abstract... 2

Keywords ... 2

Reader Responsibility in Knowledge Organisation ... 4

Historical and Contemporary Reader Responsibility ... 5

Defining Reader Responsibility ... 7

Distinguishing Knowledge and Information ... 9

Outline of Argument ... 10

The Typographic and Spatial Organisation of Knowledge ... 11

(Non-)Materiality of Paper vs. Screen ... 12

Typographic Innovations within Information Management ... 16

Reading and Writing Commonplace Books ... 16

The Political and Social Side of Commonplace Books ... 18

Analogue Knowledge Organisation ... 19

Pinterest and Knowledge Navigation ... 22

The Communication and Discourse of Knowledge ... 27

Darnton’s Communications Circuit ... 29

What is a Reference Book? ... 30

Wikipedia and Digital Knowledge Organisation ... 31

Problematic Cases of Information Organisation ... 34

The Politics of (Communicating) Knowledge ... 36

Defining the Political ... 36

Reading in the Public Sphere ... 37

Reader Responsibility among Power, Conflict, and Antagonism ... 38

Hyperlink Reading and Reader Responsibility Online ... 41

An Outlook for Reader Responsibility ... 44

Reader Responsibility in Knowledge Organisation

Today’s perspective on what reading can mean is to a certain extent a paper one, the terminology we use reflects this when we speak of e-books and web pages, and these being “published, scrolled, browsed, and bookmarked”.1 While this is the case, we also strive to capture new developments and medial possibilities. This mindset spans from notions of making ‘the great unread’ accessible through distant reading to Goodreads’ virtual online book clubs. Also new inventions are meant to aid in this process, as for instance portable ‘eye tracking glasses’ that are intended to facilitate the reading process by continuously supplying the reader with translations and definitions and highlighted words to encourage easier deep reading and, at other times, speed reading. Such novel inventions and neologisms have become firmly rooted in today’s language. This extends also to sites as Wikipedia, combining the ‘wiki’ with encyclopaedias, and Pinterest, where one can ‘pin’ interesting images and texts to virtual boards. In this thesis I strive to analyse these digital phenomena, numerical in nature and “composed of digital code”,2

of information creation, organisation, navigation, and sharing – in comparison to analogue media.

Two interesting comparative examples of traditional media for knowledge organisation are commonplace books3 and reference books. These are different textual genres,4 but they share many aspects. Ann Blair’s study Too much to know (2010) clarifies the connecting elements, namely the practice of information management, or as mentioned in this thesis’ title, (textual) knowledge organisation. In this thesis I will analyse the process of ordering and accessing of knowledge through the exertion of reader responsibility. Commonplace and reference books make use of excerpts of other texts and information as a means of coping with information overload, and countering information loss. They both facilitate the (social) discussion and communication of ideas.5 The same seems to be the case in Pinterest and Wikipedia. This thesis attempts to analyse the potential for active

engagement for the reader that such resources provide.

1 A. Van der Weel, “Explorations in the Libroverse”, K. Grandin (ed.) Going digital: Evolutionary and Revolutionary

Aspects of Digitization. Nobel symposium 147 (Stockholm: Centre for History of Science, 2011), p. 36.

2 L. Manovich, The Language of New Media (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2001), p. 27.

3 The term commonplace book stems from the Latin locus communis, thus it held “phrases worthy of imitation

under topical headings” so the writer-reader could find them again easily when the time arose to make use of them in conversation (A. M. Blair, Too much to know: Managing Scholarly Information before the Modern Age (New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 2010), p. 69f.).

4 One very important distinction in this is of course whether the books were handwritten, printed, for private use,

or intended for wider distribution. Thus, while I first focus on spatiality and typography regarding mostly hand-written commonplace books, the notion of communication, exchange, and influence on a wider audience will be scrutinised in this thesis, as well, under consideration of printed reference books. Some of these reference books were based on hand-written common place books, as e.g. the Officina by Johannes Ravisius Textor (1520), (Blair, Too much to know, p. 131f.), and then made accessible to larger audiences by print. Important to note is that these different genres of information organisation aim at presenting the reader with many different options to choose from instead of only presenting one single source (Blair, Too much to know, p. 6).

5 Further genres and terminologies that might be interesting in this regard are encyclopaedias – with the intention

Historical and Contemporary Reader Responsibility

From today’s perspective, we may be able to investigate the past anew. Of course, the present comes with its own ‘blinders’ and limitations, and one should not forget this either. Through comparisons, however, we might be able to realise what analogue reading was, and simultaneously, what digital reading may become.6 To examine reading in its analogue and digital forms, the role and

responsibility of the reader is vital, as he or she is to be found at the core of the reading process and essentially brings it to life. I believe, as Robert Darnton does, that turning to history provides a promising starting point for this investigation.7 The history of reading presents many insights into the emancipatory power of reading such as emerging mass education connected to literacy in the 18th and 19th centuries. Important was also the increasing enablement of auto-didacticism, for instance the ability to question the church’s teaching by reading the Bible oneself. The emerging literacy of women and other previously suppressed social classes presented more people with the access to information resources. Of course, one needs to bear in mind that the emancipatory power of reading – then and now – never was available to all members of society. In the following, I will thus also engage with this notion of emancipation critically.

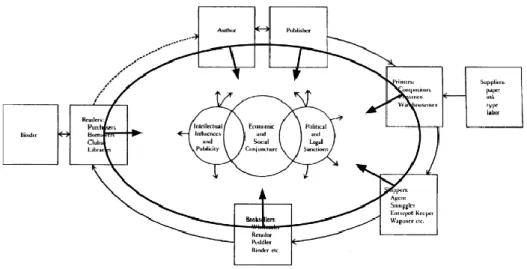

This historical perspective also reveals the challenges that readers might experience with exerting responsibility in the reading process. In a hierarchical system of analogue knowledge production, as outlined e.g. by Darnton’s Communications Circuit,8 the reader may be seen as lacking agency and being a mere recipient of the works and knowledge created by others. Concerning the context of (scholarly) knowledge creation, however, one may argue that there has been a lesser degree of hierarchy. More ‘horizontal’ and equal relations between producers and consumers of knowledge are possible in this context. These ‘producers and consumers of knowledge’ and their affiliated

institutions often were, and still are today, involved both in the creation and reception of information. Within the digital era of knowledge creation via wikis, this might be facilitated even more

successfully.9

In the following, I will delve into knowledge creation and reception and the question of how reading came to present a potential for responsibility and also which tensions accompanied this form of agency. In this thesis there will be a particular focus on early modern and contemporary digital case studies. Considering the scope of this thesis, remarkable cases were chosen so they do not necessarily

6 Cf. also Van der Weel, A., Changing Our Textual Minds: Towards a Digital Order of Knowledge (Manchester & New

York: Manchester University Press, 2011), Van der Weel, A. “Book Studies and the Sociology of Text Technologies”, Material moments: Essays in honour of Gabriele Müller-Oberhäuser, Simon Rosenberg, & Sandra Simon (eds.) (Peter Lang, 2014), pp. 269-82.

7 R. Darnton, The Case for Books: Past, Present, and Future (New York: Public Affairs, 2009).

8 This will be discussed in more detail in the following in the chapter: “The Communication and Discourse of

Knowledge”.

cover an entire given time period. I believe, as Rolf Engelsing does, that it is important to look closely and not necessarily everywhere within a certain time frame.10

The notion of the hierarchy of communication between author and reader has also already been challenged in the analogue world and more recently in the context of poststructuralism, where “the birth of the reader” and the “death of the author” have been proclaimed by Roland Barthes.11

Today in the digital era, one might argue that even more fundamental changes concerning this constellation are occurring within reader responsibility. The digital world can be seen as enabling more egalitarian relationships for it brings readers, authors, and other involved agents into an easier and faster

multidirectional contact. It is thus claimed that many structural, political, and tangible hierarchies that once governed our world and particularly information exchange within it, may be overcome in the digital era. It is believed by some that information exchange today occurs between many different, equally responsible and active members of society.12

One needs to be critical of this ‘democratisation discourse’ surrounding the Internet however, and especially so in times of the Web 2.0.13 In present discussions, structural elements and

technological affordances are often seen as automatically enabling democracy and freedom. As pointed out by Matthew Hindman, though, one has to differentiate between the normative and the descriptive statements concerning the Internet and its effect on democracy.14 While there is the structural and theoretical potential for the Internet to further and support democracy by allowing the members of society to have more interaction,15 in practice this is not necessarily implemented successfully. Simultaneously, this democratisation discourse is used to justify political and economic decisions that are actually countering the Internet’s democratisation potential. In light of the digital divide and many people’s inability to access the Internet regularly, reliably, and through high-speed

10 R. Engelsing, Der Bürger als Leser (Stuttgart: J. B. Metzler, 1974), p. 1.

11 R. Barthes, “From Work to Text.” Modern Literary Theory: A reader. P. Rice, & P. Waugh (eds.), (London & New

York: Edward Arnold, 1989), p. 170. While this thesis does not address the writing and reading of fiction but of non-fictional texts, this poststructuralist insight by Barthes is important nonetheless. The ‘death of the author’ is more than just an observation about the end of the author’s authority concerning fictional developments. Rather, it signifies the necessity of the reader to take an active role in interpreting and bringing to life of the text for it does not exist effectively otherwise. Only through being read by a reader does any text come into existence and may assume any meaning. It is this that can be learnt from Barthes and that also plays a great role for knowledge creation and textual communication. Knowledge also only exists when there is someone creating it and thereby consciously holding it.

12 Cf. P. Aigrain, & S. Aigrain, Sharing: Culture and the Economy in the Internet Age (Amsterdam: Amsterdam

University Press, 2012) and D. Tapscott, & A. D. Williams, Wikinomics: How Mass Collaboration Changes Everything (New York: Portfolio, 2008 [2006]).

13 This means the World Wide Web as enabling multi-way communication between different user as opposed to

‘Web 1.0’ users with only a few active creators and many passive consumers. The term Web 2.0 was coined by Darcy DiNucci but made known by Dale Dougherty and Tim O’Reilly. In a BBC interview Tim Berners-Lee, the inventor of the web, refuses this terminology for he holds that this use of the web was always its intended purpose, BBC Interview with M. Lawson, “Berners-Lee on the read/write web”, BBC, 8th September 2005,

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/technology/4132752.stm (7th June 2015), n. pag. Seeing as the ‘buzzword’ is used for

the implication of easy and fast interaction, I will make use of it nonetheless in this thesis.

14 M. Hindman, The Myth of Digital Democracy (Princeton & Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2009), p. 6. 15 Van der Weel, “Feeding our reading machines”,

connections, the all-embracing nature of democratisation through the Internet also becomes questionable.16 New gatekeepers and information hierarchies seem to be establishing. The political agendas at work in the discourse surrounding ‘democratisation’ and their effective outcomes for readers are thus to be scrutinised carefully. A critical investigation into reader responsibility will thus be my pursuit in the following.

Defining Reader Responsibility

Reader responsibility may be seen as coming into existence before the digital age. I define it as the process of finding, accessing, making sense of, interpreting, judging, and putting to use the

information that can be gained through reading, thereby turning it into knowledge. Depending on how far back one wants to go in the defining of the process of reading, one may claim, as David Olson does, that it “is the recovery/postulation of an audience-directed intention for a text which is justifiable on the basis of the available graphic evidence”.17 The idea of intention highlights the communicative aspect that reading always and necessarily involves.

Robert Darnton also alludes to what I summarise as ‘reader responsibility’ when he writes the following: “Segmental reading compelled its practitioners to read actively, to exercise critical judgment, and to impose their own pattern on their reading matter. It was also adapted to ‘reading for action’, (...) for [those] who consulted books in order to get their bearings in perilous times, not to pursue knowledge for its own sake or to amuse themselves”.18

With this statement, Darnton at once reaffirms my idea that reading may have political repercussions and affect one’s actions, as well as that reading in itself may be seen as an active process of knowledge creation. In his analysis of ‘digital readers’ responsibilities’, Alain Giffard also addresses this notion when describing the reader’s responsibility as being exerted when the reader ‘closes the text’, i.e. when she or he “selects, collects, and binds together the different fragments of texts”.19

In highlighting the “responsibility for one’s reading”,20

Giffard also introduces the political dimension of this discussion that I will turn below. As Van der Weel claims, “intellectually the reader has never been the passive recipient Plato famously saw”;21

he draws the difference between the intellectual process of reading as deciphering/decoding, as also Stanislas Dehaene speaks of in Reading in the Brain,22 and the technologically mediated process, in which the affordances of the respective medium matter and influence the extent to which reader responsibility may be exerted. However, I believe that these two

16 Cf. A. Taylor, The People’s Platform: Taking Back Power and Culture in the Digital Age (New York: Metropolitan

Books, 2014), p. 109f.

17 D. Olson, The World on Paper: The Conceptual and Cognitive Implications of Writing and Reading (Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press, 1994), p. 273.

18 R. Darnton, The Case for Books, p. 170.

19 A. Giffard, “Digital readers’ responsibilities”, in J. Kircz, & A. Van der Weel (eds.), The Unbound Book (Amsterdam

University Press, 2013), p. 83.

20 Giffard, “Digital readers’ responsibilities”, p. 83.

21 A. Van der Weel, “Towards a new digital order of knowledge”, Pre-publication Draft, p.10.

22 S. Dehaene, Reading in the Brain: The New Science of How We Read, (New York & London: Penguin Books,

levels are more interconnected than one might think initially, and also that the affordances are not more practical or tangible than the theoretical considerations about what reading is and may mean. Despite the seemingly greater difference between the screen and paper from e.g. paper and clay – this difference is only a conceptual one, for reading is never natural, as stressed by Maryanne Wolf.23 I emphasise this because appealing to greater degree of ‘reality’ or ‘tangibility’ when trying to elevate some forms of reading over others is a mere attempt of persuasion – all reading is ‘artificial’ in that it is human-made and an acquired ability, and in this, of course, also lies its potential. However, I do not mean to negate the rather different medial circumstances under which reading may take place and the different repercussions this might bear. Precisely because “[r]eading is not innate; [and] is (…) learned, it is always learned in a particular literate social environment”.24

It is these environments that I want to compare and analyse in the following. Not to come to a value judgment about the best single one of them, but to locate advantages and disadvantages among the many currently available cultural, economic, and political possibilities of and for reading.

The definition of texts, thus the what is being read in Donald McKenzie’s words is best suited for my endeavour of comparing commonplace books, reference books, Pinterest, and Wikipedia – by texts McKenzie means:

verbal, visual, oral, and numeric data, in the form of maps, prints, and music, of archives of recorded sound, of films, videos, and any computer-stored

information, everything in fact from epigraphy to the latest forms of discography.25

While his definition of reading focuses on the ‘what’ in terms of the medium and the form, there is also another way of looking at the process of reading that implies the universal character of reading and also supports the notion that (almost) anything may be read as text. This conception focuses on the approach and set of mind required for reading. It thereby presupposes McKenzie’s broad recognition of text.26 A particular interest of mine in this thesis then lies with online reading and digital reading and the question how the modes of reading here compare to traditional reading.

Despite often treated as the ugly step-sibling of traditional reading – I believe that there might be hope for this ‘new’ type of reading. When referred to as “close reading 2.0”,27

for example, this becomes very interesting for it implies the possibility of continuing (some of) the implied advantages of e.g. traditional, analogue, paper-based, deep, and close types of reading. It seems to me that the most important aspect of this attitude towards reading is the concentrated, thorough, attentive, and critical

23 M. Wolf, Proust and the Squid: The Story and Science of the Reading Brain (New York & London: Harper

Perennial, 2007), p. 215.

24 Van der Weel, “Towards a new digital order of knowledge”, p.17.

engagement with the respective text. This is required in order to understand the “woven state, the web or texture of the materials” as McKenzie describes it.28

With this notion of a web in mind, I would like to turn to the important difference between information and knowledge.

Distinguishing Knowledge and Information

At this point, the distinction between information and knowledge is vital. Maryanne Wolf raises an important notion when she asks: “Will unguided information lead to an illusion of knowledge, and thus curtail the more difficult, time-consuming, critical thought processes that lead to knowledge itself?”.29

While I will address this problem of (de-)contextualisation of information in detail below, I will firstly look at terminology. Simply, while information is the ‘content’ of a certain medium, knowledge is what readers extract from or make out of this content through processing it. Blair distinguishes between these terms by clarifying that “we speak of storing, retrieving, selecting, and organizing information, with the implication that it can be stored and shared for use and reuse in different ways by many people – a kind of public property distinct from personal knowledge”.30 Thus, while information is what can be put on paper – or captured in bits and bytes and be portrayed on the screen – knowledge is what readers, i.e. people, make of it through using their critical, reflective, creative minds. In the case of sharing and communicating thus, it makes sense to speak of both, information and knowledge: to make information communicable, it needs to be actively held as knowledge by someone.

However, as Peter Burke writes, we live in a time of plural ‘knowledges’ instead of one singular knowledge.31 Hence, debates may arise around different forms and areas of discourse and the question which knowledges are to be preferred over others. Renear is also aware of this and writes that: “[i]n the past, information seeking was seen to be the first step to creating knowledge. Now… it is a continuous process”.32

Does this mean though, that knowledge cannot ever be obtained and that we are caught in a perpetual mode of searching without ever finding what we are looking for? This same conundrum seems to exist irrespective of time and situation, because it has already confused the Ancients, among them Seneca and Plato, later then the medieval scholars, the humanists, as well as it is troubling us today.33 In the following, I will expose ways in which information may be ‘turned into’ knowledge and also how this is possible in analogue, as well as digital, media. In this, I wish to object the notion of ‘unguided information’ as presented by Wolf and explain how reader responsibility can function as a contextualising and reflective force, and that it may be learnt to improve general social and political circumstances.

28 McKenzie, Bibliography and the sociology of texts, p. 13. 29 Wolf, Proust and the Squid, p. 221.

30 Blair, Too much to know, p. 2.

31 P. Burke, A Social History of Knowledge Volume II (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2012), p. 5.

32 A. H. Renear, C. L. Palmer, “Strategic Reading, Ontologies, and the Future of Scientific Publishing”, Science 325

(2009), p. 829.

Outline of Argument

One may argue that in the digital world, the potential for reader responsibility is greater because of a more egalitarian relationship between reader and author and that this is a welcome development for it grants the reader the potential to emancipate him- or herself, but one may also argue that this is a problem because the reader has to be extremely active, and potentially bear a greater responsibility than he or she is capable of. It is my claim that despite the better and more elaborate possibilities for participation for the reader in academic, social, cultural, and political actions and processes, these opportunities are too seldom sought out and that this needs to be ameliorated. Within the scope of this Master Thesis, I will investigate the challenges and opportunities posed to the reader by focusing on reader responsibility in the knowledge (creation) context considering scholarly as well as

non-scholarly readers.34 I will investigate commonplace books, reference books, Pinterest, and Wikipedia. In this, I limit myself to the case of knowledge creation that arguably presents a special case for reader responsibility, as will be highlighted in the following. It is the underlying claim of this thesis that reader responsibility is historical in origin, necessary in the reading process, and extends itself into the digital age, where it is strongly linked to the development of democracy, and might also be seen as being conducive to it.

With this thesis, I wish to investigate the repercussions of reader responsibility in the digital age by comparing the aforementioned historical and contemporary case studies. It seems that today in the digital age, where more possibilities and freedoms exist structurally for the reader, in many cases, not enough chances are actually taken as opportunities to act upon. Thus, capitalism and ‘fake’ visions of democracy may often be seen as hindering reader responsibility from assuming any real power and becoming effective. By invoking “[a] world where only the connected will survive”,35 Don Tapscott and Anthony D. Williams in Wikinomics (2006) present a programmatic vision for this problematic situation. Furthermore they demonstrate the successful interplay of the Internet, the ideology of ‘sharing’, and capitalism. The problems connected to this vision are aptly summarised by Astra Taylor, who abridges Tapscott’s book’s opening anecdote with the following words: “a banker-turned-CEO goes from rich to richer (of course, there was no mention of the workers in the mine and the wages they were paid for their effort, nor an acknowledgment (…) of human rights and

environmental violations)”.36

The implications of this conception of society, economy, and politics will be addressed in detail below and I will also present a revised view on democracy that encourages means of re-conceptualising and also countering these issues.

34 This might be somewhat difficult for the demarcation between scholarly and non-scholarly readers might be

conducive to this process. One might argue that the hierarchy between readers and authors in the academic context was always less. For the scope of this thesis, I extend this claim for the knowledge creation context. Further research into the different types and fields of readers might be interesting.

35 D. Tapscott, & A. D. Williams, Wikinomics: How mass collaboration changes everything (New York: Portfolio, 2008

[2006]), p. 12.

36 A. Taylor,The People’s Platform: Taking Back Power and Culture in the Digital Age (New York: Metropolitan Books,

However, to do so, I will first contextualise the reading process and its potential for democracy and political change via its influence on information organisation. In this, digital media also present readers with many new and unforeseen possibilities that may lead to more egalitarian exchanges of information, and may also enable more instances of diverse knowledge creation. It is this thesis’ intention to locate the problems in exerting reader responsibility by engaging in a comparison between historical and contemporary case studies and then propose ways in which they may be successfully dealt with, or at least understood in order to develop coping strategies. The digital and analogue case studies chosen for this thesis lend themselves well for comparison because in them, several aspects converge. The chapters of this thesis will thus analyse the spatial/typographic organisation of knowledge, the communicative and social aspect of knowledge, and the political dimension of knowledge creation. The overarching question I want to answer with this thesis is how reader responsibility can be conceptualised in order to mobilise political agency within today’s digital environment, and how inspiration can be drawn from past developments for this.

The Typographic and Spatial Organisation of Knowledge

The joint (and inseparable) history of text production/distribution and text consumption is the history of the Order of the Book and the making of Homo typographicus. (…) We have come to function as textually literate beings to the extent that the printed word assumes an almost tangible reality.37

Bearing in mind this quotation, one may ask in how far digital reading may assume this ‘tangible reality’ – which seems to be so readily understandable in the analogue world of reading. Reading as a process occurs in several different layers of coding: the individual characters and sentences on the page, the mise-en-page, the mise-en-livre, and the overarching infrastructure or cultural meaning of the book.38 Due to reasons of scope, I will not be able to explore all these different levels in detail. However, it needs to be highlighted that they are all important for reading: they define analogue, as well as digital knowledge creation, and find similar as well as different applications in commonplace and reference books. Within the present chapter, I will concentrate on the mise-en-livre to approach this topic, with some elaborations into the mise-en-page as constitutive of the mise-en-livre: “the way we place text two-dimensionally on the page and three-dimensionally in books” are strongly

interconnected.39 In these two levels, reader responsibility is of utmost importance, for the

reader/writer has to recognise the unity or relations between the different elements coming together on

the page and in the book. Only through the process of this transfer, the reader/writer is able to organise and understand the information presented and turn it into knowledge of her or his own.40 The questions I will be investigating in this chapter are: How does the spatial and typographic arrangement and organisation of knowledge differ between historical (early modern)41 commonplace books and contemporary Pinterest-boards?42 How does this enable different modes of responsibility? And which levels of the typographical organisation of knowledge can exist in the world of Pinterest?

In an online environment, there seems to be a fluidity of the page as well as the ‘book’ and its infrastructure. One might go as far as denying the existence of these categories in the digital era. I am interested in what this may mean for reading and the creation and organisation of knowledge. There is a strong case to be made for the analysis of the tangibility of the digital page and the online

typography used in relation to the intended meaning and also a clarification of the reading process at work.43 Van der Weel claims though that “fixity is a (…) vital precondition for the emergence of the Order of the Book” and as such vital also to the creation of the ‘literal mindset’ needed for knowledge organisation in an analogue and paper world.44 The question then is, whether the openness and flexibility made possible by the digital medium are destructive to this ‘literal mindset’ or whether it can also be constructive in new and unforeseen ways.45

(Non-)Materiality of Paper vs. Screen

Bonnie Mak begins her book, How the page matters with the following words:

This book is about how the page matters. To matter is not only to be of importance , to signify, to mean, but also to claim a certain physical space, to have a particular presence, to be uniquely embodied.46

40 There are many interesting studies investigating the relationship between reading, writing, and memory (e.g. Blair’s

Too much to know).While this is a fascinating topic, it is outside of the scope of this thesis, i.e. the psychological and neurological effects of spatial knowledge representations and the effect of writing and reading on the creation and up-keeping of memories will not be investigated. Further interesting studies on the psychological issues or neuroscientific conceptualisations of reading can be found in Reading in the Brain by Stanislas Dehaene and Proust and the Squid by Marianne Wolf. Katherine Hayles also touches upon these elements in How we think (2012) – while again I will not delve into her psychological research, I will address her concept of hyper reading below because of its political potential.

41 While this is a term coined in hindsight, as most terms describing historical eras – thus also relying on the

accuracy of these other eras in turn –, ‘early modern’ refers to “the period which falls roughly between the end of the Middle Ages and the start of the nineteenth century” (E. Cameron, Early Modern Europe (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), p. vxii).

42 Cf. Fig. 4 on p. 24 for an example.

43 Schofield, S., & Weber, J., “Opening the Early Modern Toolbox: The Digital Interleaf and Digital Commonplace

Book”, Scholarly and Research Communication 4.3 (2013), http://src-online.ca/index.php/src/article/view/127/324 (3rd June 2015).

44 Van der Weel, “Feeding our reading machines”, n. pag.

45 While I will delve into the political potential and meaning of this in the third chapter, this chapter is concerned

with the extent of reader responsibility required in navigating the typographic and spatial information display.

46 B. Mak, How the Page Matters: Studies in Book and Print Culture, (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2011), p.

I would like to investigate in how far this ‘page’ needs to be made of paper47

and whether a page as constituted by Pinterest might also fall under such a category and support the reader in her or his exertion of reader responsibility. The term ‘to have a particular presence’ is especially interesting in this, for denying digital media the presence they have seems to be a common misconception of their role within the media landscape. And as Mak goes on to explain in her introduction: “the page (…) is not always what we may think it is”.48

In her view, “[d]igital pages are complex interfaces that provide a point of contact between designer and reader. Like their analogue counterparts, these pages communicate verbally, graphically, aurally, and tactilely, and are constructed in a material way that influences how they are read and understood”.49 The digital page has “its own distinct materiality” and it has different boundaries than the printed page, sometimes it even has no boundaries.50

However, as David M. Berry rightly interjects, this page-like thinking is too limited to

understand the possibilities offered by Web 2.0 (Fig. 1). While the Internet might have traditionally been intended by its adversaries such as Tim Berners-Lee as a structure of “pages and websites”, we are moving away from this towards “the newer industrial Internet and the concept of ‘real-time streams’” as well as APIs (application program interfaces) and all-embracing social networks.51

So, might we say that the paper-analogy is an imagined and outdated framework for understanding the digital world? Or are we, in imagining this connection to the analogue world of paper, pen, and print, creating the framework through which we are first able to conceptualise the Internet at all? Berry’s outlook is rather bleak and he ties it closely to political and economic situations:

The importance of patterns in computation capitalism will likely produce a kind of cognitive dissonance with the individual expecting pattern aesthetics

everywhere, understood as a form of apophenia, that is, the experience of seeing meaningful patterns or connection in random and meaningless data.52

Berry implies that the reader all-too readily infers meaning where there is none and hereby feeds into capitalist economic circumstances. So, does it make sense to view reading online as page-like?

47 David Olson in his work The world on paper seems to answer this question rather directly with the title of his

book already. While I agree that paper played an important role in the beginning of this process, I believe that the notion of “thinking about thought” (Olson, The World on Paper, p. 282) does not solely rely on or end with paper. I aim to go beyond his conception of reading and also include digital reading and its potential for critical, and most importantly, political thought.

48 Mak, How the Page Matters, p. 4.

49 Ibid., p. 62. Cf. also Van der Weel, “Book Studies and the Sociology of Text Technologies”, where he refers to

the ‘digital counterparts’ of analogue media and by choosing this terminology implies the equivalence of these different media and calls for researchers and scholars to take them all equally serious.

50 Mak, How the Page Matters, p. 62.

Fig. 1 Web 2.0 word/tag cloud.53

Roger Chartier is also critical of digital developments. He writes that “[t]he electronic representation of texts completely changes the text’s status”, and he praises the navigation that a codex enables and the way in which it may oppose “the free composition of infinitely manipulable fragments”.54

While he elaborates on these negatively open and unfixed aspects of digital text, he also allows for the infinity of possibilities that this type of reading may present the reader with, e.g. an important chance to exert reader responsibility: “The distinction that is highly visible in the printed book between writing and reading, between the author of the text and the reader of the book, will disappear in the face of an altogether different reality: one in which the reader becomes an actor of multivocal composition or, at the very least, is in a position to create new texts from fragments that have been freely spliced and reassembled”.55

Also, Chartier is aware that the meaning of every textual work is created in and through the reader for “a text exists only because there is a reader to give it meaning”,56 and that these ‘created’ works then “have no stable, universal, fixed meaning”.57

What he claims here about printed works, is just as true for digital works. And it is highly important that he heralds the openness of meaning within print. This shows how alike print and digital are concerning this aspect, he hereby he counters the often perceived opposition between these different media for reading. Can the openness of the page and the book thus be ways of framing digital reading?

Most convincingly, McKenzie bridges the ‘material’ divide between analogue and digital texts. He speaks of a “shift from fashioning a material medium to a conceptual system, from the weaving of fabrics to the web of words”.58

He thereby explains how reading is not merely the deciphering of characters or signs recorded on a medium, but rather the creation and organisation of knowledge by a responsible reader. This freeing of reading from the material context and recognising it beyond the

53 “A tag cloud (a typical Web 2.0 phenomenon in itself) presenting Web 2.0 themes”, Wikipedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Web_2.0#/media/File:Web_2.0_Map.svg (6th June 2015).

54 R. Chartier, The Order of Books: Readers, Authors, and Libraries in Europe Between the 14th and 18th Centuries

(Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1994), p. 18.

55 Ibid., p. 20. 56 Ibid., p. 2. 57 Ibid., p. ix.

boundaries of paper (page, or book) is a necessary move – today more than ever, but also in 1999, when McKenzie published his book Bibliography and the sociology of texts.

Analogue reading is a concept retrospectively informed by and in a way thus tainted by the knowledge of digital reading. This is connected to the recognition that printed text is fixed, which was encouraged by becoming aware of digital text’s lack of fixity. Nevertheless, it is difficult to clearly differentiate in how far these modes of reading, analogue and digital, differ and what this means for reader responsibility. Especially interesting is the relationship between the coding, the medium, and the reader: While design and layout of digital text (e.g. flowable e-pub) may be adapted to a reader’s preferences, a stable and controllable mise-en-page can only exist in the analogue manuscript or print, or in PDF.59 One may thus ask, how does the way readers can exert their preferences facilitate and/or obstruct their reader responsibility? The dynamic natures of Pinterest and Wikipedia may be seen as impediments to ‘secure’ knowledge creation. However, one may also argue that in an uncertain world, and within the continuous process of research new ideas should be allowed to come up and replace other ideas. The idea of stable knowledge might prove fallacious in itself, for is not constant revision necessary for critical and reflective thought? Thus, the fluidity of the digital media, while criticised for making information retrieval (more) difficult, is also an adequate portrayal of the (fast) changes that are occurring in the world. These changes have been occurring ever since information collection began, and ever since authors, readers, and scholars could complain about information overload.

Most importantly however it is not the fluidity or flexibility of the new media that harm knowledge creation. The often criticised ‘decontextualisation’ is not a necessary consequence of the fast moving digital media. Rather it can be found in various forms throughout history. The problems and strengths of context arise from its power to manipulate and frame information in a certain way. This can be done in print and online. The aforementioned critical knowledge however, can only be achieved when the reader can engage critically with a text’s context, its sources, and justifications for framing information in a certain way. As I will show in this thesis, the presently discussed analogue media such as commonplace and reference books, as well as Pinterest, often engage in an obscuring of context – by hiding it behind authority or by simply ignoring it. And while this partly is also true for Wikipedia, this platform at least may be seen as offering a tool for engaging in discussions about the framing of information. It is this possibility to counter the problematic ‘decontextualisation’ that is vital for the reader to assume responsibility. Of course, this requires a very active reader. In a way, one can argue that the act of contextualising is also aided greatly by the digital media. With this idea in mind, I will now turn to the spatiality of knowledge creation.

59 The variability of screen and printer options may, too, create diversity of copies of the same text/website.

Typographic Innovations within Information Management

Ann Blair’s elaborations on the typographic innovations undertaken within the information

management environment are very relevant in this context. She explains how better legibility, access, and understanding of textual information could be achieved in reference works “through the use of blank space, varied fonts, and typographical symbols or woodblock decorations or illustrations”.60

By this she highlights the impact that printing had on knowledge and information resources. The

conventions established by printing however, also carried into manuscript writing, and the early modern commonplace books that will be discussed in the following show marks of these conventions at use. Blair describes how many of these conventions we now associated strongly with a book’s organisation and structure came about first within the printing process. The page numbers we know originated in “the numbering of sheets in the form of signatures [that was necessary] to aid printers and binders”.61

Eventually, they turned out to support readers in their orientation within the text, too, and established themselves as firmly rooted conventions. Other elements of books, such as the title page, are more connected to the necessary marketing of printed books that were not created on demand, but printed first and then advertised and sold to the emerging audience. Seeing as manuscript books were ordered by the readers and paid for in advance, the future owners did not require a title page for identification, they had ordered the book and were waiting for it; also, there were generally fewer books around so it was easier to navigate the information they held.62

Another interesting comparison may thus be drawn between early modern and contemporary information management; it concerns information stored and registered just in case, without having an actual application yet. While in the early modern times, such activities required well-developed systems of search and retrieval, indexing etc., today the belief persists that it is much easier to find information that has gone missing. And the presentation and storage of information ‘just in case’ has also become more popular and feasible. Inexpensive wikis, websites, and other online platforms may be used for this. Information recording and presenting is no longer limited by the shortage of paper. Reading and Writing Commonplace Books

In the most general sense, a commonplace book contains a collection of

significant or well-known passages that have been copied and organized in some way, often under topical or thematic headings, in order to serve as a memory aid or reference for the compiler. Commonplace books serve as a means of storing information, so that it may be retrieved and used by the compiler, often in his or her own work. The commonplace book has its origins in antiquity in the

60 Blair, Too much to know, p. 49. 61 Ibid., p. 49.

idea of loci communes, or ‘common places’, under which ideas or arguments could be located in order to be used in different situations.63

There is a long history of this genre of information structuring. It has its origins in the “rhetorical works of the Classical era” and then was practiced as well in medieval florilegia, the Renaissance commonplace books, and arguably still today through digital information curation platforms.64 A guiding idea in this is what Bob Whipple calls “unruly”, thus the personal and handwritten – and not “cleaned up” to be disseminated through printing – commonplace book: it bestows on the compiler many freedoms where she or he can “try out” ideas.65

This trying out and the process of creative invention is an important aspect of knowledge organisation.

Commonplace books were, and still might be seen by some as “trusted means of moral and rhetorical development” because in creating them, the creator interpreted, contextualised, and judged the claims and statements of another and thereby tested and trained his or her own values and

reference points.66 “Commonplace books ensured that no communicative encounter would render one dumbstruck, that one’s inventories of invention would never go empty”.67

Thus, while commonplace books formed the basis for outside discussions and meetings, Pinterest, a commercial photo sharing website that was launched in 2010, might be seen as doing something similar: providing food for thought, but also as constituting an arena where such ‘encounters’ may take place in the first place. In a way, thus, commonplace books are the ultimate site for reader responsibility taking place for they “reinforce (…) invention as a process that requires collection, organization, and reflection in the service of incorporating material into a larger communicative effort”.68

Blair highlights that “[w]hile most florilegia can be classed as commonplace books, ‘commonplaces’ were also used to organize material that did not consist of authoritative quotations but, for example, of precepts or examples”.69 As aforementioned, commonplace books may be analysed as belonging to the wider category of reference works. It is interesting to ponder them in proximity to Blair’s following statement:

Depending on their arrangement (alphabetical, systematic, or miscellaneous), reference works typically deployed one or more finding aids, including tables of contents, alphabetical indexes, outlines, dichotomous diagrams, cross-references,

63 “Commonplace Books”, Harvard Views of Readers, Readership, and Reading History,

http://ocp.hul.harvard.edu/reading/commonplace.html (20th June 2015).

64 “Commonplace Books: Collections Then and Now”, Beinecke Library, 14th January 2010,

http://beinecke.library.yale.edu/programs-events/events/commonplace-books-collections-then-and-now (19th June 2015).

65 B. Whipple, “Images, the commonplace book, and digital self-fashioning”,

http://wac.colostate.edu/books/copywrite/chapter5.pdf (20th June 2015), p. 100.

66 C. Geraths and M. Kennerly, “Pinvention: Updating Commonplace Books for the Digital Age”, Communication

Teacher (2015) 29.3, p. 1. “Like the original commonplace books, these new [digital] form allows students to assimilate social and scholarly knowledge, assemble arguments, and achieve copiousness in the service of their own communication” (Geraths and Kennerly, “Pinvention”, p. 7).

67 Ibid., p. 2. 68 Ibid., p. 2.

and a hierarchy of sections and sub-sections made visible on the page throughout the use of layout, symbols, and different scripts and fonts.70

This highlights once more the spatial and typographic nature of analogue information and the web-like structures that writing creates, as McKenzie sees it, and as which information may also be conceptualised. Particularly the structure of the web, a terminology prominently used in the digital age, lends itself well for such considerations for its manifold and changing interconnections. The Political and Social Side of Commonplace Books

The commonplace book is a communicational aid whose time has come … again.71

Bearing in mind this quotation from Cory Geraths and Michele Kennerly’s article “Pinvention: Updating Commonplace Books for the Digital Age” (2015), one may continue to observe that commonplacing as an activity of organising and accessing information has never gone out of fashion and is making quite a prominent existence in the digital world.72 Geraths and Kennerly, teachers at Pennsylvania State University, actively employ Pinterest as a mode of teaching and assessing students in their classes on debate and public speaking.73 Before I compare Pinterest to commonplace books though, I will first delve somewhat deeper into the history of commonplace books themselves.

Commonplace books were used mostly in the early modern period through to the 18th century. In the 19th and definitely the 20th century their use came to an end for they were considered an outdated mode of information organisation.74 Seeing as commonplace books were mostly used to prepare for discussion and debates, this may be seen as one of their social elements. They were also “meant to be passed on within a family” and hereby acquired a new dimension of exchange and communication between the generations of a family.75 The information stored in them was considered valuable for the later generations and members of the family. And is not the idea that the process of commonplacing itself is vibrant on the Internet today a strong counter argument against this process of having outlived its usefulness? One may argue that due to improved access and sharing of information the same is happening today: information relevant for family members and friends may be collected on Pinterest or other online curation platforms, and shared with the general public. This may be seen as shaping the way in which people view themselves and their social environment.76

70 Ibid., p. 4.

71 Geraths and Kennerly, “Pinvention”, p. 2.

72 Commonplacing may also be used as a verb (Blair, Too much to know, p. 117).

73 Geraths and Kennerly, “Pinvention”. Cf. also Fig. 4, p. 24 for a visualisation of how they imagine Pinterest may be

used for brainstorming.

74 N. Carr, The Shallows: How the Internet is Changing the Way We Think, Read and Remember (London: Atlantic

Books, 2011 [2010]), p. 180.

75 Blair, Too much to know, p. 86.

In his book Reading Revolutions (2000), Kevin Sharpe investigates the political power of

reading, especially in the context of commonplace books in early modern England. And, despite some disagreements with Sharpe about the meaning and use of postmodern theory within history and the reception thereof, Darnton largely agrees with Sharpe on the importance of commonplace books, and also sees them “as sites to be mined for information about how people thought”.77

By selecting and arranging snippets from a limitless stock of literature, early modern Englishmen gave free play to a semi-conscious process of ordering experience. The elective affinities that bound their selections into patterns reveal an epistemology at work below the surface. That kind of phenomenon does not show up in conventional research and cannot be understood without some recourse to theory. Foucault probably offers the most helpful theoretical

approach. His ‘archaeology of knowledge’ suggests a way to study texts as sites that bear the marks of epistemological activity, and it has the advantage of doing justice to the social dimension of thought.78

Darnton goes on to highlight that authors and readers came to be merged within the commonplace tradition, for they were necessarily performing both functions. Through this double activity, “they developed a still sharper sense of themselves as autonomous individuals”.79 Sharpe then sees a potential for political action in this, for reading as an act of interpretation is an exertion of “the reader’s own judgment”,80

and in this sense an important prerequisite for becoming an active participant in democracy. For him, commonplace books are central in this because they are a site where the selection, organisation, and creation of knowledge takes place.81

Analogue Knowledge Organisation

The mise-en-page is an important constituent of knowledge creation in the early modern

commonplace book. An interesting case study that Ann Blair talks about in her treatment of reference books in Too much to know, is the Polyanthea, an anthology of literary fragments and excerpts, by Nani Mirabelli, first published in 1503.82 It was an alphabetical collection of information, including quotations, definitions, translations, biblical and religious texts, and humanist ideas, that Mirabelli

77 R. Darnton, The Case for Books, p. 169. 78 Ibid., p. 169.

79 Ibid., p. 170.

80 K. Sharpe, Reading Revolutions: The Politics of Reading in Early modern England (New Haven & London, Yale

University Press, 2000), p. 292.

81 Ibid., p. 339.

deemed noteworthy and wanted to collect and preserve for future generations and “for the common utility”.83

It became a very popular work: copied, printed and re-edited several times.84

An interesting example from this book is the following branching diagram in Fig. 2:85 “The diagram offers not a finding device to the contents of the article but an outline of how one might teach or preach the topic”; it thereby presents a ‘mind-map’ of a particular topic, in the case of Fig. 2,

abstinentia.86 One might argue that this is comparable to the links one can follow on Pinterest when searching for the posts pertaining to one category or posted from one user. The board or ‘home page’ displays the potential elements relating to this topic and thus may be compared to this ‘mind-map’. Also, when following up on the images and links provided, one might be guided to other websites and further information and as such the board may serve as this aforementioned outline on the respectively presented topic. It is interesting that Geraths and Kennerly use Pinterest as a teaching strategy, too – quite in the spirit Blair outlines for early modern commonplace books. The idea in both cases is to be presented with a manifold variety of options to approach a given theme; the reader must then

consciously choose which links or ideas to follow and in which order and thus exerts reader responsibility.

Fig. 2 Branching Diagram from Polyanthea.87

While Pinterest is all about creating an assembly of snippets of information under a common heading, there is another early modern technique of information management that serves a similar purpose and that was also used by authors who wrote commonplace books themselves: the note closet (Fig. 3). In it, “[n]otes taken on slips of paper were stored on the hooks attached to the metal bars, each hook was associated with a topical heading inscribed on the front of the bar. The closet could accommodate 3.000 to 3.300 headings. At least two such closets were built”.88

This is an even more literal spatialisation of information.

Another vital interest in the closet that e.g. Vincent Placcius, as an early modern scholar, had in this closet was the enablement of other scholars to consult and cooperate in the note-taking process. While there were only few of these closets in use and they may be seen as experiments rather than reading reality, it is interesting to see that Pinterest in a way makes possible what readers and scholars have been dreaming of for a long time: (virtual) spatial organisation, social interaction, flexibility in knowledge management, easy findability, and retrievability.

Fig. 3 Note Closet as described by Vincent Placcius in De arte excerpendi

(1689).89

Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc (1580-1637) and his work present another interesting case of the use of spatial arrangement within commonplace books for information management. He did not publish anything, but he took many notes with an interesting typographic system, using blank sheets to start new sections, respective topical heading in the upper left, and all his papers were sorted into bundles with wrappers stating what they contained.90 One might be able to compare this to Pinterest’s board-structure.

It is precisely these notions that Geraths and Kennerly allude to in their attempt to revive the commonplace book with the help of Pinterest. Inspired by the early modern ideals of cooperation between researchers, they investigate the communicative potential of Pinterest. However, they hereby partly ignore the implied hierarchy in the early modern model of delegating the lower tasks of

research:91 “A humanistic reader had full knowledge of belonging to an intellectual elite, but was also interested in the expansion of that elite”.92

The idea of egalitarian cooperation, already difficult in early modern times, is complicated today by economic and ideological aspects just as well. Therefore, I will now look more closely at the structure and workings of Pinterest.

Pinterest and Knowledge Navigation

When trying to assess the role Pinterest may play in knowledge organisation, several questions need to be addressed: How does Pinterest function, what are underlying economic motivations, and how does it relate to information management and knowledge creation in relation to reader responsibility? One might find it difficult to see it as presenting text at all, because Pinterest is “an online medium devoted almost entirely to photographs and images”.93

However, when remembering McKenzie’s wide definition of text, one can see how the usage of Pinterest may be understood as reading. Due to its “noncompetitive environment without prominent display of number of followers”,94

Pinterest may be described as an environment well-suited for the exchange of ideas and comments, as well as the free expression of thoughts and sentiments. In line with this set-up, H. C. Sashittal and A. R. Jassawalla found in their research conducted with 16 Pinterest participants that:

Pinterest usage produces an experience of enrichment; college students [who use it] feel they have become more expressive and organized, and better connected with themselves and with [each other].95

90 Ibid., p. 86ff. 91 Ibid., p. 102.

92 C. Font Paz, & J. Curbet, “The Renaissance”, Cultural History of Reading, G. Watling (ed.) (Westport & London,

Greenwood Press, 2009), p. 146.

93 H. C. Sashittal, J. R. Jassawalla, “Why Do College Students Use Pinterest?: A Model and Implications for Scholars

and Marketers” Journal of Interactive Advertising (2015) 15.1, p. 1.

As Geraths and Kennerly explain, Pinterest may be conceptualised as “a social networking platform geared toward the visual and spatial” representation of ideas and grouping of these according to certain overarching topics and themes.96 Creative knowledge creation, comparable to that within the historically established genre of commonplace books, may thus be seen as taking place on Pinterest. As Deborah Lui writes, “individual acts of collection on the site contribute to a new kind of public construction of knowledge online”.97 This may be also called the potential of ‘digital curation’ offered by Pinterest: the (re-)organisation of images, statements, quotations, visualisations, and graphs may be compared to the practice of assembling commonplace books.98 Especially interesting is also why and how people use Pinterest, especially the aforementioned students, who might be seen as an audience bridging the academic and lay audience.99 Knowledge creation thereby receives another dimension, namely the social and communicative – this will be investigated more closely in the following chapter, after a more in-depth discussion of the workings of Pinterest:

When entering the site, the user finds his or her ‘home page’. It is compiled from images and pins from boards, users, and topics that the user is following. Pins are images, texts, or items that can be posted to boards which can be given titles or subjects. These boards can be made public or kept private. Pinterest is dynamic and “discovery-based”,100

which is meant to bring more flexibility and creativity as well as the element of chance to the searching process. While one might debate the workings and algorithms behind this, the “indefinite number of pathways that one can take” are also an interesting reconceptualization of the aforementioned mise-en-page and mise-en-livre. One might claim that this constitutes a complete destruction of these structures. However, this might also visualise the fluidity that these structures have always possesses already, albeit formerly, in a more theoretical manner. The ‘actual’ fluidity and flexibility of knowledge creation and information organisation on Pinterest highlights the underlying necessity for reader responsibility in all instances of reading.

On his blog, Alan Jacobs interestingly carves out the main points of comparison necessary when investigating commonplace books and some of their digital counterparts. Firstly, he distinguishes between two different types of commonplace books, the scrapbooks that may be seen as the predecessor of today’s “Everything Bucket”, i.e. the wild mixture of “recipes, notes from sermons, remedies for common maladies”, and the more selective commonplace book that “was to gather a collection of the wisest statements, usually of the ancients, for future meditation”.101 His main point of

96 Geraths and Kennerly, “Pinvention”, p. 2. As H. C. Sashittal and J. R. Jassawalla point out (cf. p. 1), Pinterest is

dominated by females, whereas Wikipedia – as will be discussed below – is dominated by males. In both cases, an in-depth study concerning gender and the respective medium is be called for – particularly concerning public awareness, depiction, influence, and bias. Within the current scope of this thesis this is not possible however.

97 Lui, “Public Curation and Private Collection”,p. 129.

98 M. Zarro, C. Hall, “Exploring Social Curation”, D-Lib Magazine (December 2012) 18.11/12,

http://www.dlib.org/dlib/november12/zarro/11zarro.print.html (27th June 2015).

99 H. C. Sashittal, J. R. Jassawalla, “Why Do College Students Use Pinterest”?. 100 Lui, “Public Curation and Private Collection”, p. 134.

emphasis lies with the intentionality of collecting the different textual elements. It was possible – then and now – to cut/copy and paste information without being very attached to or conscious of it.

However, one may, of course, also be intellectually invested in this process of information recycling through actively reflecting on it. An advantage that the digital world offers is that information can be more easily shared because the sources from which we might like to borrow texts, snippets, images, etc., do not have to be cut apart and destroyed anymore: anyone can copy the information and the original source may remain intact.102

On Pinterest, with its ‘pin and board’-structure, “each pin functions like a discrete entry in a traditional commonplace book”.103

Thus,

in turning to the past as a source for future design, humanists must reflect on the principles behind even the most familiar of communicative acts. The benefits of those reflections are immeasurable; they remind us, again and again, that how we read matters.104

Fig. 4 Screenshot of Michele Kennerly’s Pinterest Board CAS100A.105

The title of the board in Fig. 4 derives from the course “Effective Speech: Civic Engagement” at Pennsylvania State University in which Michele Kennerly teaches at the department of CAS

(Communication, Arts, & Sciences). This board is used as an example of how Pinterest may be used as a brainstorming device and a help for knowledge organisation and management within the teaching of the aforementioned course. Pinterest may then be understood in terms of the ‘docuverse’ as

described by Van der Weel:106

102 Ibid., n. pag.

103 Geraths and Kennerly, “Pinvention”, p. 3.

104 Schofield & Weber, “Opening the Early Modern Toolbox”, p. 7.

The docuverse also integrates the realms of moving images, still images, sound, that can be accessed by anyone who is connected to the network every moment of every day of the year. In the docuverse the collection level (that is to say, the infrastructure) and the content level merge.107

In all of the aforementioned cases, commonplace books and Pinterest, reader responsibility is of importance, for the reader and/or writer must piece together different elements, ideas, and notions and thereby create knowledge. The question is however, in how far is this feasible and has chances of success? What would be holding the user back in this? One important factor influencing the reader online, mostly through untransparent but highly effective means, that needs to be considered is increasing commercialisation:

The Internet has its roots in a non-profit environment, usually succinctly paraphrased by ‘the information wants to be free’ slogan. We do not know for how much longer.108

One has to bear in mind that Pinterest as a commercial company is intricately part of the capitalist system and promotes economic gain through user ‘surveillance’.109 Pinterest is often framed as a tool for marketing and branding, and one might see this as a clash to information providing for the sole sake of sharing and creating knowledge. At this point it needs to be remembered that also print was and is governed by capitalism, and that this does not necessarily eradicate its critical, reflective, or positive potential. However, the social side of exchange in Web 2.0 may also be seen as endangering privacy, 110 and open it up to commercial exploitation and political surveillance, especially in terms of data mining and user data analysis for search engine optimisation, marketing, and other commercial uses.111 Another complicating factor is the lack of ‘new’ information on Pinterest: 80% of the pins are ‘recycled’ instead of created ‘originally’.112

While this might largely be comparable for commonplace books, it does highlight the boundary of the ‘newness’ of information creation.

One may ask then, is Pinterest the best example for a digital environment for commonplace books? Many researchers are suggesting their own, other, digital platforms and programs to use for digital commonplace book note-taking, reading, and researching – there is a plethora of available

107 Van der Weel, “Feeding our reading machines”, n. pag. 108 Van der Weel, “The Communications Circuit Revisited”,p. 23.

109 Discussions on whether Pinterest is actually harming or supporting real-life shops and businesses or the

data-mining of “retailers and ad networks” to facilitate the selling of their products illustrate this (Lui, “Public Curation”, p. 140).

110 Miha Kovać in J. Kircz, & A. Van der Weel (eds.), The Unbound Book (Amsterdam University Press, 2013), p. 14. 111 Lui, “Public Curation and Private Collection”, p. 132.