VOLUME 81 #{149}FEBRUARY 1988 #{149}NUMBER 2

Pedtrs

Behavioral

Pediatrics:

A Time for Research

Robert

J. Haggerty,

MD

From the William T. Grant Foundation and Department of Pediatrics, Cornell University Medical College, New York

There are many children with problem behav-iors who are not being helped, in large measure

because we do not know enough about the causes of their problems or the effectiveness of therapy for them. The study of office visits by Starfield et al’ demonstrated that at least 15% of children have psychosomatic problems and another 5% to

10%

social and behavioral problems (Table 1). The cause and impact of these problems are like the interrelated layers of an onion, with biologic and social environmental forces interacting to ulti-mately affect the functioning of the child. Theseare not new problems. Although

.

the term “the new morbidity” has been applied to many of them, most are not “new.” In colonial times in America, one third ofthe women were pregnant at the time of their marriage. Premarital conception was an issue then as it is now. It is only the solution or consequences that are different today. The great frequency of these problems yesterday and today, the serious impact that they have, and the failure to treat or prevent most ofthese problems suggest that a major effort should be placed on research.Advocating research does not mean that we should scrap current service programs as

advo-cated

by some2 or isolate the research worker fromReceivedforpublicationSept22, 1986;acceptedMarch 11, 1987. Based on the annual lecture to the Society of Behavioral Pe-diatrics, Washington, DC, May 8, 1986.

Reprint requests to (R.J.H.) William T. Grant Foundation, 919 Third Aye, New York, NY 10022.

PEDIATRICS (ISSN 0031 4005). Copyright © 1988 by the American Academy of Pediatrics.

the stress and difficulty of coping with clinical problems and real people. Romano3 said, “clinical medicine is not a spectator sport,” and I would add that clinical research in behavioral pediatrics cannot be a spectator sport but is best done by those who are actively caring for children with problem behaviors. Insights into the causes and development ofpromising therapies come as often from active clinicians as from theoretically based researchers. We need both working together, stimulating each other to solve these serious prob-lems of today’s children.

WHO

SHOULD

DO RESEARCH

IN

BEHAVIORAL

PEDIATRICS?

Clinicians need to join with behavioral scien-tists and epidemiologists to study this field. The recent advances in neurobehavioral sciences em-phasize the need to maintain strong links between biology and behavior in research. Not all of the problems of behavior are going to be solved by modern molecular biology, but some are, and pe-diatricians need to keep a foot in this camp. The research team should be small-no more than three or four key people; otherwise, communica-tion can be difficult-but it should include differ-ent disciplines working together on the same problem.

Epidemiologic

Longitudinal-Natural History Nosologic

Psychophysiologic

Screening and Diagnostic Tests

Effectiveness of Preventive and Therapeutic Interventions

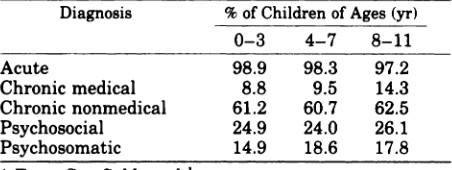

TABLE I. Childhood Mor tion-Based Office Practice*

bidity as Seen in a

Popula-Diagnosis % of Children of Ages (yr)

0-3 4-7 8-11

Acute

Chronic medical Chronic nonmedical Psychosocial Psychosomatic

98.9 98.3 97.2

8.8 9.5 14.3

61.2 60.7 62.5

24.9 24.0 26.1

14.9 18.6 17.8

* From Starfield et al.x

do not have the answer to all of the behavioral

problems ofchildren. We need to know much more

about the causes of behavioral problems, which

other behavioral scientists, such as sociologists and epidemiologists, can make greater

contribu-tions. Some of these problems require

psycho-therapy, some medication, and others change in environment or education. But for some problems behavioral therapy is appropriate. Pediatrics is in the enviable position of being able to choose the best from all disciplines. But in many areas we need new ideas and hypotheses, not ill-conceived interventions. Here, ethnologists or anthropolo-gists can be useful. The personal characteristics of the scientist, such as openness to new ideas, flexibility, tolerance of another’s discipline and research skills, together with sound sophisticated research methodology (whether it be

anthropol-ogic, sociolanthropol-ogic,

psychologic,

or epidemiologic), are the necessary ingredients of effective collabora-tive team research.It is never too late in a career to do research. Sometimes it is only with considerable clinical ex-perience that one begins to perceive the associa-tions that lead to research hypotheses. But be-cause behavioral pediatrics is complex, multifactorial, and difficult, those who contem-plate a research career should obtain the rigorous training early in their life with a mentor who is actively doing research, usually in conjunction with a sophisticated multidiscipline group. There can be

too

much classroom learning of research methods. Theory needs to be given high priorityin research but not at the expense of hands-on

research activity. Physicians should take long enough to master research skills and concentrate on an area. Doctorate students in the behavioral sciences spend 3 to 4 years learning research skills. Physicians cannot expect to do this in much less time.

WHAT

RESEARCH

SHOULD

RECEIVE

PRIORITY

At one level, “what” can be answered with:

“Any question that stirs one’s curiosity.” But that

is too superficial an answer. With so few people doing sophisticated research in behavioral pedi-atrics, and so few resources for support ofthe field, we must use these resources wisely to takle only the problems that are significant and do-able. Do-ability is an important point. A common mistake young investigators make is to tackle too large a problem initially-one that does not have a clear methodology available. It is obviously important to have reliable and valid methods as well as an important problem. One way to categorize the

types

of research that can and should be done in behavioral pediatrics, and for which there are generally good methods available, is shown in Fig1.

Epidemiology

Epidemiology has been neglected by behavioral pediatricians. Most data concerning frequency of behavioral problems have been derived from cross-sectional data (that is, the same children were not followed throughout time). Cross-sec-tional data do not tell us the cause(s) of these phe-nomena and they oversample those with persist-ent problems at the expense of those who move in and out of problem status, but they do stimulate a lot of questions and they are much easier to do. Epidemiology means “upon the people.” The key point in epidemiologic research is to have a de-fined population (people)-either of patients or of nonpatients, preferably of both. For instance, in-vestigators of the epidemiology of teenage sui-cide-a most important problem-need to look at the proposed causal factors such as alienation, depression, peer pressure, peer imitation, school pressure, drug use, and exposure to media in matched samples among those not attempting or committing suicide as well as those who do. Most of these types of attitudes and psychologic states are present in many children who never attempt or commit suicide. All

too often

in epidemiologic studies in which only clinical populations are used factors are attributed as causal when their fre-quency is equal in a matched nonaffected sample. Some of the most common and disabling behavior problems of children that should be the target ofSuicide

School dropout (underperformance) School.age pregnancy

Substance abuse Delinquency

Unemployment

Sexually transmitted diseases Poor health habits

Accidental injuries

Biologic susceptibility Chronic physical disease

Family breakup-conflict, violence Poverty-economy-lack of jobs Neighborhood disorganization Peer influences

High stress

Delayed mature role Developmental problems

Fig 2. Common and disabling problem behaviors of

children.

epidemiologic and other studies are listed in Fig

2.

Some ofthe many factors found associated with these problems in previous studiesare

shown

in Fig 3. But association does not equal causation. Only longitudinal studies can do this.Longitudinal

Studies

Follow-up of the same cohort throughout con-siderable time is most important and is really the only way to establish cause and effect relations between environmental and genetic factors and outcome. Robins4 in his Howland Award Address

urged

us

to take the long view. When outcomes are separated in time from causal factors by many years, we have difficulty relating cause and effect except by longitudinal studies. There are major difficulties in carrying out longitudinal studies in this country, however. These include the expense, the mobility of both subjects and investigators, and the often small and unrepresentative samples in such studies. The Social Science Research Council recently catalogued existing longitudinalstudies of children.5 More than 116 were found.

It is clear that as a society we will not be able to fund that large a number, and we are unlikely to have more than a few national longitudinal stud-ies like the three British “birthday” longitudinal studies of all children born in a country during a given week. Somewhere between these two ex-tremes we need to do some creative thinking about how to develop the needed longitudinal studies. An example of one such recently

com-Fig 3. Factors associated with problem behaviors.

pleted way is a study that developed a “follow-back” investigation ofchildren born to a large na-tionally representative sample of young people who have been studied throughout many years. In this US Department of Labor survey of 12,000 young people as they entered the work force, there

are

now more than 6,000 children born to them. There has been a great deal of data collected dur-ing the years concerning the parents’ behavior as they emerged from adolescence into adult work roles and established families. Data have now been collected about the children and correlated in a “prospective way” with these previous data. This major project, supported by the US Labor De-partment, was unknown to most of us in the child development field, but it provides a two-genera-tion, semilongitudinal study without having tostart

at birth with a new cohort. No investigator will ever live long enough to complete a lifetime study of an individual or cohort, but if studies are done in segments of the life span and linked with existing studies, a great deal can be learned from such semilongitudinal studies.Another example of using existing samples to create longitudinal studies is Steinberg’s6 use of the Chess and Thomas sample of children to cor-relate temperament measured many years earlier in childhood with type A behavior now that the children are young adults. Another excellent ex-ample of a longitudinal study during one segment of time-the first 10 years-is the study by Wer-ner and Smith7 ofhigh-risk children in Kauai, HI,

especially the report on resilient children. Their focus on resilience is another much needed ap-proach. Rutter,89 as usual, says it so well, “There is a regrettable tendency to focus gloomily on the ills of mankind. . . . It is unusual to con-sider the factors that promote support, protect and ameliorate problems of children raised in depri-vation.” Still another short-cut to overcome the problems of longitudinal research is the case-con-trol method. Epidemiology ofbehavioral problems offers a great deal as a way to understand their origins and natural history.

Nosology

Nosology,

the science of classification of dis-eases, sounds esoteric and dull, but how we labela problem has a great deal to do with how we treat it (and how we get reimbursed for care!). We need to pay more attention to how we classify common problem behaviors of children. The Diagnostic

and Statistical Manual ofMental Disorders, ed 3,

and the International Classification of Diseases,

rev 9, are inadequate classification schemes for

neatly as Christmas packages when they present themselves for help, and they do not distinguish themselves at first as having either solely behav-ioral or solely biologic problems. We should spend a good deal more time working on a practical clas-sification of behavior problems in children, using symptoms and complaints as well as presumed

diseases or syndromes only.

Psychophysiologic

Problems

Psychophysiologic problems of children should receive much more emphasis, especially from medical people. Although there are many problem behaviors of children that have no physiologic basis, it is surprising that pediatricians have been negligent of this area. Child psychiatry has re-cently begun to show great interest in the field with studies of neurotransmitters in disorders such as autism or Tourette syndrome or the in-teraction of psychosocial factors on hormone and antibody production and their relation to the onset of illnesses such as juvenile diabetes or asthma. There are major technical difficulties in this field, but if the methods of

modern

biologic scientists are used, there are now many measures that can be made, often in noninvasive ways, that could illuminate the biobehavioral interface.Sal-ivary

cortisol

and norepinephrine, secretory IgA in the pharynx, urinary cortisol and norepineph-rine, skin resistence, cardiovascular responses in-cluding 24-hour monitoring of heart andrespi-ratory

rate and BP are such examples of measures in well populations. In children who are already ill with diseases such as asthma or diabetes, blood levels of various hormones, antibodies, WBCs, CSF endorphines and are but a few of the phys-iologic measures that could be obtained to study the biobehavioral interactions. An excellent re-view of the field has appeared recently.9Environmental stress and its relation to infec-tion has proven to be a fruitful example of studies at this interface. The classic work of Jemmott et al’#{176}demonstrated decreased secretory IgA in pha-ryngeal secretions of students who were stressed by examinations. The importance of this study is not merely that it demonstrated the relation be-tween stress and illness, but it also defined the interaction between certain personalities (those who were high in the need for power and control and who had a high reactivity to the stress of ex-aminations), and specific biologic reactions. They also demonstrated the mechanism of increased susceptibility to infection in these students, namely, reduced secretory IgA in the pharynx, one of the body’s first lines of defense against

infections.

Some of these studies ofphysiologic and clinical responses to stress are listed in Table 2.

Catecholamines and cortisol clearly have key roles in human responses to stress and are prob-ably the mediators for some of the diseases that sometimes follow stress. Frankenhauser” in Swe-den has done much to further our understanding of the psychophysiologic relations of these hor-mones. In the psychologic state of effort without distress (that is, the joyous or happy state), cate-cholamine levels increase, but cortisol levels de-crease. In effort with distress (that is, daily has-sles) both cortisol and catecholamine levels increase. In distress without effort (that is, the helpless state) the cortisol level alone increases. She has further demonstrated remarkable sex dif-ferences. Women are less likely than men to re-spond to achievement demands. That is, with

ef-fort,

with or without distress, their catecholamine levels do not increase as high as men’s. Some in-teresting studies in children immediately suggest themselves. For instance, how early in life do these differences occur? Are they different de-pending on personality or goals or gender? Are there hereditary patterns? Can they be modified?What

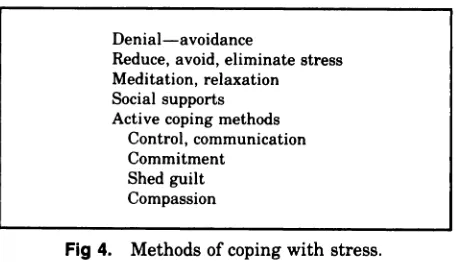

are the prices paid-that is, increased heart rate, increased BP, increased fatty acids-by those who do respond? There are some fascinating studies’2’4 of WBC metabolism with psychologic stress that demonstrate modifications oftheir me-tabolism in stressed humans. One such study demonstrated that lymphocytes from distressed psychiatric patients have slower rates of DNA re-pair after irradiation than those from psychiatric patients with low distress.’2 Some of the mediat-ing or coping skills found to be helpful in mod-erating adverse effects of stress are listed in Fig 4. Combining these interventions withphysio-TABLE 2. Studies of Biologic Correlates of Stress

Author and Reference No.

Population! Topic

Measures

Friedman et al’5 Parents of children with leukemia! bereavement

Urine cortisol concentration Clinical disease

Kiecolt-Glaser et al’2

Students! examination stress, loneliness

Herpes antibody

Boyce et al1#{176} Families/family routines

Respiratory infections Bartrop et al’3 Spouses!

bereavement

Lymphocytes

Schleiffer et al9 General population! bereavement

Lymphocytes

Jemmott et al’#{176} Students!

academic

stress

Denial-avoidance

Reduce, avoid, eliminate stress Meditation, relaxation

Social supports Active coping methods

Control, communication Commitment

Shed guilt Compassion

Fig 4. Methods of coping with stress.

logic measures should provide great insight into

stress-related problems.

There is also a great deal that could be learned

by research on animal models. Plaut and

Friedman16 used the mouse model to study the interaction of infection, stress, and crowding. Ader and Cohen’7 have more recently demon-strated that conditioning animals by giving sac-charine plus cyclophosphamide, which, of course, depressed the antibody response of the animals, resulted subsequently in depressing antibody pro-duction when the animals were given saccharine alone. Recent evidence that there are neurofibers to the spleen, thymus, and bone marrow as well as the lymph nodes suggests that these humoral and antibody responses are linked to the CNS. Other animal studies have demonstrated reduced natural killer lymphocytes and increased tumor

growth in animals taught learned helplessness.’8 One of the reasons why the study of biopsy-chologic reactions is important is that there may be pharmacologic approaches to therapy. For in-stance, haloperidol for Tourette syndrome or lith-ium for bipolar depression has been more effective

than psychotherapy alone. But even if under-standing of the physiology has not led immedi-ately to successful biologic therapy, the under-standing of the mechanism removes the mystical aspect of behavioral medicine. With the greater availability of noninvasive physiologic methods, we are now in a position to study the process and mechanisms of biobehavioral interaction.

Not all stress is bad. Early successful coping with stress makes some children somewhat in-vulnerable to later life stresses, and children need to be prepared to face stress in the future. Neither does exposure to stress alone explain the adverse outcomes. Stress is filtered through the person-ality and life experience of the individual, as Boyce et al’9 have postulated (Fig 5). These

flu-ters-personality, coping skills, and inherit-ance-determine whether the result is detrimen-tal or not. As Plaut and Friedman’6 demonstrated in animals, the stress field is a complicated one. In their studies, stress in some species of animals with some infectious agents actually increasedre-Light _._. Filters Intensity

Rays

(Life

.-4

(Perception)-(Stress Effects)Change)

Fig 5. Life change stress is filtered by the individual’s perception, to result in different amounts of physiologic response, much as light rays are altered by filters.

sistance, whereas in others it decreased it. The need now is to study the complexity of these in-teractions and the interrelated mechanisms of be-havior and biology in man.

Screening

and Diagnostic

Tests

For Oftice

Pediatric

Practice

Reliable, valid, and predictive screening and

di-agnostic tests for behavioral problems in office practice should have a high priority for pediatri-cians in this field. A few are now adapting some of the standard research instruments such as the Achenbach child behavior checklist to office prac-tice and attempting to determine the relation of

such measures to improved pediatric practice. Much more needs to be done to develop practical office tests to detect behavior problems early, to determine functional health status of these chil-dren, and to select those at high risk for a variety ofbehavior problems to target interventions more

efficiently.

Eftectiveness

of Preventive

and Therapeutic

Interventions

Both preventive and therapeutic interventions are important. If proof of efficacy of a given in-tervention is established, physicians may still not make use of the procedures, and insurers may not pay for it; but if such information is not available,

it is clearly difficult to achieve either of these goals. The fact that we still do not have good stud-ies showing the effect of well-child supervision certainly has hampered efforts to sell to Congress the Child Health Initiative

Reform

Plan, famil-iarly called CHIRP-the plan to require health insurers to pay for health supervision if the pre-miums for insurance are to be tax deductible. Such research is difficult, but studies of outcome or efficacy can sometimes be done by finding ser-vice programs already in existence and thenmar-rying the research to the service program. This frees the researcher of the need to fund and ad-minister the service and removes potential bias by the researcher. This is called action research.2#{176}

immuni-:::::::::

Delinquency Teenage Pregnancy---4. Accidents School Failure Poor Health Habits zation) for a single type of problem and looks at

its efficacy. The other approach is large scale so-cial reform approach. The report of the Carnegie Commission on Chjldren2’ recommended income redistribution to eliminate poverty and increase provision ofjobs to permit the poor to control their own lives and achieve political influence. As im-portant as these reform efforts are-and without them we will probably never see large changes in the frequency of behavior problems that result from social factors-it is a mistake to limit in-tervention and research at either the narrow re-ductionistic or the large scale social reform level. An example of an intermediate approach is that of Old et al22 who used nurse home visitors, social

support networks, crisis interventions,

mentor-ing, and comprehensive medical care to improve the outcome of pregnancy and mothers. This ex-ample gives hope and encouragement to many others to develop larger scale programs. Barth and Schinke23 have been investigating the effect of a social skills-training program for young preg-nant women in two schools. The groups were led by social workers and met twice weekly for 10 weeks. Through role playing and discussion, so-cial skills are developed for resolving conflicts which threaten social supports. A controlled eval-uation compared students who did not participate with those who did and demonstrated improved social skills, increase in social supports, and pos-itive student feedback. The results of these stud-ies suggest a type of intervention for these high-risk young women which, could lead to improved parenting and reduction of risk of future un-wanted pregnancies and reduction of behavioral problems in these young mothers and their ba-bies. Some less orthodox interventions, such as hypnosis and suggestion, also have their place in therapy. Olness et a124 has conducted a controlled trial of self-hypnosis compared to propranolol for children with migraine headaches.

Research on interventions should be rigorous. Controlled trials with random assignment, if pos-sible, are best; and this technique is more often possible than many think, ifone has the discipline

to

try it. However, there has been too great an emphasis on trying to intervene for only one spe-cific behavioral problem. In this instance, the medical model has failed us. In the preantibiotic era, when there was no magic bullet, researchcon-cerning tuberculosis began to emphasize the mul-tiple causal factors, and interventions that ranged from improvement ofhousing, reduction of crowd-ing, street and home sanitation, improvement of nutrition, and rest and relaxation were developed as therapy. But when particularly effective inter-ventions with antimicrobial agents were

devel-CAUSES PROBLEMS

Personal

Poor Self Esteem

Peer Pressure Religious Practice

Physical Development

Education

Family Breakdown Poverty

Work Potential

Fig 6. Noncategorical approach to many different problem behaviors seems appropriate, given the fact that many of the same causal factors lie behind most problems.

oped, efforts at these broader, more general ap-proaches were forgotten. In the behavioral field, although there may be a few specific therapeutic interventions in the future similar to isoniazid for tuberculosis, at this time chances of this seem re-mote. Much more likely to be successful are pro-grams that will help young children to have com-petence and skill in dealing with problems and to feel of service to others. Such skills may then lead to a reduction in several problems rather than only one. This noncategorical approach seems ap-propriate when we see the same causal factors re-lated to many problems (Fig 6). Some of the in-terventions for children with a variety of problems such as learning disabilities, chronic physical illness, substance abuse, and teenage pregnancy have had more success when they have used a combination ofinterventions such as young people helping others, peer counseling, teaching kindergarten children how to read, or taking old people in nursing homes for walks, or cleaning up their neighborhood. Young people who feel good about themselves and have hope for the future do better. Such general intervention approaches may well lead to reduction in several ofthese problems, rather than the current fad of targeting an inter-vention on only one of these problems at a time.

Finally, there is the issue of how much the pro-vision ofbroad psychosocial services will diminish traditional medical illness and the use of health services. Cummings (Behavior Today, February 1986, p 7) reported that health maintenance

or-ganizations that provided three brief psychother-apy sessions reduced visits to physicians for other reasons by 65%. Others25 have reported similar reductions of health care use if psychiatric care is provided. Behavioral pediatricians should exam-me this important issue.

CONCLUSIONS

1. Never as many subjects as estimated available

2. Nobody knows what the controls experience 3. RateS of refusal are greater than expected 4. Crossover of experimental and controls will occur 5. During the demonstration both experimental and

controls get better

6. The control group shows almost as favorable effects as experimental

7. The experiment is never continued long enough 8. Any effects of the intervention dwindle and

evapo-rate with time

9. Every step in the experiment takes longer than planned

Fig

7. Rosenstock’s rules.if it is to achieve credibility. For some this means pursuing the usual path to success, namely, re-ductionist, often basic biologic research, but for others, it means the more challenging path of tak-ing a broad approach to the solution of children’s problem behavior, of trying intervention pro-grams that give children a sense of competence and service to others and an ability to commu-nicate and relate to others. In the process, this approach may result in prevention of a multitude of problems rather than any single behavioral

problem. The task of the serious student of

be-havior is to learn technologically sophisticated re-search skills, to learn to work with other

disci-plines, including the biologic, and yet at the same

time maintain a broad perspective. I am mindful of the lack of wisdom of those who in the past advised others, and I would urge that one keep a healthy skepticism about this advice. The path of research, especially intervention studies, is a rocky one. Rosenstock’s rules are Murphy’s law applied to research (Fig 7).

REFERENCES

1. Starfield B, Katz H, Gabriel A, et al: Morbidity in child-hood-A longitudinal view. N Engi J Med

1984;310:824-829

2. Murray C: Losing Ground: American Social Policy,

1950-1980. New York, Basic Books, 1984

3. Romano J: Requiem or reveille: The clinician’s choice. J Med Educ 1963;38:584

4. Robins FC: The long view. Am JDis Child 1962;104:499-530

5. Verdonik F, Sherrod LR: An Inventory of

LongitudinaiRe-search on Childhood and Adolescence. New York, Social

Science Research Council, 1984

6. Steinberg L: Early temperamental antecedents of adult type A behavior. Deu Psychol 1985;22:1171-1180

7. Werner EE, Smith RS: VulnerableButlnvincible: A Study

ofResilient Children. New York, McGraw-Hill Book Co,

1982

8. Rutter M: Protective factors in children’s responses to stress and disadvantage, in Kent MW, RolfJ (eds): Social

Competence in Children. Hanover, NH, University Press

of New England, 1979, vol 3: Primary Prevention of

Pay-chopathology, p49

9. Schleiffer SJ, Schleifer SJ, Keller SE, et al: Behavioral and developmental aspects ofimmunity. JAmAcad Child

Pay-chiatry 1986;26:751-763

10. Jeminott JB ifi, Barysenko JZ: Academic stress, power motivation, and decrease in secretory rate of salivary me-cretory immunoglobulin A. Lancet 1983;1:1400-1402

11. Frankenhauaer N: The sympathetic-adrenal and pitui-tary-adrenal response to challenge: Comparison between the sexes, in Dembraski TM, Schmidt TH, Blumchen G (eds): Behavioral Basis of Coronary Heart Disease. New York, S. Karger, 1982, pp 99-105

12. Glaser R, Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Speicher CE, et al: Distreme and DNA repair in human lymphocytes. J Behau Med 1986;8:311-320

13. Bartrop RW, Lazarus L, Luckhurst E, et al: Depressed lymphocyte function after bereavement. Lancet

1977;1:834-836

14. Baker GHB, Irani MS, Byom NA, et al: Stress, cortisol concentrations and lymphocyte subpopulations. Br Med J 1985;290:1393

15. Friedman SB, ChadoffP, Mason SW, et al: Behavioral ob-servation of parents anticipating the death of a child.

Pe-diatrics 1963;32:610-625

16. Plaut SM, Friedman SB: Psychosocial factors in infectious diseases, in Ader R (ed): Psychoneuroimmunology. New York, Academic Press, 1981, pp 3-30

17. Ader R, Cohen N: Behaviorally conditioned immuno-suppression and murine systemic lupus erythematosis.

Science 1982;215:1334-1336

18. Levy SM: Behavior as a biological response modifier: The psychoimmunoendocrine network and tumor

immunol-ogy. Behau Med Abstr 1985;6:1-4

19. Boyce WT, Cassel JC, Collier AM, et a!: Influence of life events and family routines on childhood respiratory tract illness. Pediatrics 1977;60:609-615

20. Rapoport RN (ed): Children, Youth, andFamilies: The

Ac-tion-Research Relationship. Cambridge, MA, Cambridge University Press, 1985, p 320

21. Keniston K, the Carnegie Commission on Children: All

Our Children: TheAmericanFamily UnderPressure. New

York, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1977

22. Olds DL, Henderson CR Jr, Tatelbaum R, et al: Improving the delivery of prenatal care and outcomes of pregnancy: A randomized trial of nurse home visitation. Pediatrics

1986;77:16-28

23. Barth RP, Schinke SP: Enhancing the social supports of teenage mothers. Social Casework, November 1984, pp 523-531

24. Olness K, MacDonald JT, Uden DL, et al: Comparison of self-hypnosis and propranolol in the treatment ofjuvenile classic migraine. Pediatrics 1987;79:593-597