ARTICLE

Variation in Standards of Research Compensation

and Child Assent Practices: A Comparison of 69

Institutional Review Board–Approved Informed

Permission and Assent Forms for 3 Multicenter

Pediatric Clinical Trials

Michael B. Kimberly, MBea,b, K. Sarah Hoehn, MD, MBec, Chris Feudtner, MD, PhD, MPHa,b,d, Robert M. Nelson, MD, PhDb,c,e,

Mark Schreiner, MDc,f

aPediatric Generalist Research Group,eCenter for Research Integrity, andfChildren’s Clinical Research Institute, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania;bCenter for Bioethics anddLeonard Davis Institute of Health Economics, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania;cDepartment of Anesthesiology and Critical Care, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVE.To systematically compare standards for compensation and child partici-pant assent in informed permission, assent, and consent forms (IP-A-CFs) ap-proved by 55 local institutional review boards (IRBs) reviewing 3 standardized multicenter research protocols.

METHOD.Sixty-nine principal investigators participating in any of 3 national, multi-center clinical trials submitted standardized research protocols for their trials to their local IRBs for approval. Copies of the subsequently IRB-approved IP-A-CFs were then forwarded to an academic clinical research organization. This collection of IRB-approved forms allowed for a quasiexperimental retrospective evaluation of the variation in informed permission, assent, and consent standards operation-alized by the local IRBs.

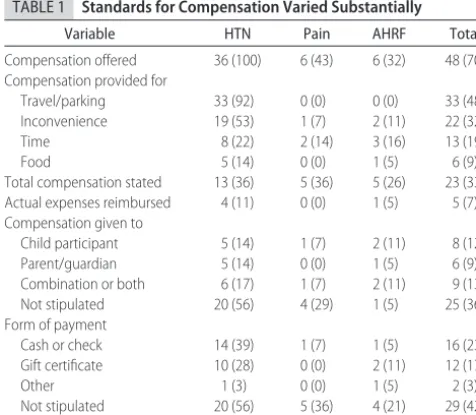

RESULTS.Standards for compensation and child participant assent varied substan-tially across 69 IRB-approved IP-A-CFs. Among the 48 IP-A-CFs offering compen-sation, monetary compensation was offered by 33 as reimbursement for travel, parking, or food expenses, whereas monetary or material compensation was offered by 22 for subject inconvenience and by 13 for subject time. Compensation ranged widely within and across studies (study 1, $180 –1425; study 2, $0 –500; and study 3, $0 –100). Regarding child participant assent, among the 57 IP-A-CFs that included a form of assent documentation, 33 included a line for assent on the informed permission or consent form, whereas 35 included a separate form written in simplified language. Of the IP-A-CFs that stipulated the documentation

of assent, 31 specifiedⱖ1 age ranges for obtaining assent. Informed permission or

consent forms were addressed either to parents or child participants.

CONCLUSION.In response to identical clinical trial protocols, local IRBs generate IP-A-CFs that vary considerably regarding compensation and child participant assent.

www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/ peds.2005-1233

doi:10.1542/peds.2005-1233

Key Words

ethics, institutional review board, permission, assent, informed consent, research subjects, quasiexperimental design

Abbreviations

IRB—institutional review board IP-A-CF—informed permission, assent, and consent form

CCRI—Children’s Clinical Research Institute PI—principal investigator

AHRF—acute hypoxemic respiratory failure

Accepted for publication Nov 2, 2005

Address correspondence to Michael Kimberly, MBe, 597 Orange St, New Haven, CT 06511. E-mail: mbk@alumni.princeton.edu

H

OW DO DIFFERENT institutional review boards (IRBs) vary in their application of standards for compensation and child participant assent for identical pediatric clinical trial protocols? The standards and spirit of informed consent, an essential component of ethicalconduct of human subjects research,1–4 are

operational-ized in pediatric research in 3 distinguishable forms: per-mission of parents or guardians, assent of child subjects in accord with their developmental level, and consent of

emancipated adolescents and young adults.5For each of

these forms of permitting, assenting, or consenting to re-search participation, controversy remains over what con-stitutes best practices at an operational level of detail.

At a general level, guidance on the proper content and process of informed consent and assent follows from several authoritative sources. Federal regulations pro-mulgated in 1981, and today known as the Common

Rule,6require institutions that receive federal funding to

use IRBs to review human subjects research proposals and to evaluate and approve informed consent forms. In 1998 the US Food and Drug Administration updated the

Guidance for Institutional Review Boards and Clinical Inves-tigators outlining in greater detail its expectations for

documentation of informed consent and assent.7In the

pediatric research setting, IRBs review a broader set of documents that appropriately correspond with chil-dren’s developing capacity to make decisions for them-selves. These forms document agreement to participate in the research study by the child’s guardian’s informed permission, the child’s assent, or the emancipated mi-nor’s or young adult’s informed consent. Although the labels affixed to these documents vary, we refer to them collectively as informed permission, assent, and consent forms (IP-A-CFs).

At a detailed level, the exact parameters for meeting the enumerated elements of IP-A-CFs are still left essen-tially to the discretion of local IRBs. Federal regulations promulgated in 1983 and reiterated by the Food and Drug Administration in 2001 grant IRBs wide discretion to determine whether child assent should be obtained or

documented in addition to parental permission.8,9Unless

the research protocol offers the child direct benefit not otherwise available, researchers are required to obtain assent unless the child is not capable. Yet, unlike the informed consent standards, the regulations specify no

key elements of assent.9

Despite the latitude afforded to IRBs, little research addresses how different IRBs vary in their handling of

informed consent and assent. A previous study10

de-scribed variability in IRB chairpersons’ opinions about discretionary aspects of child assent and compensation; nonetheless, how chairpersons believe their IRBs should exercise discretion may, in fact, differ from actual IRB

behavior. Two other studies11,12each used a combination

of methods to describe variation in the process of local IRB review of protocols and IP-A-CFs, although neither

study analyzed IP-A-CFs themselves. Because variation in how IRBs operationalize informed consent and child participant assent has implications regarding the current state of human subject protection, particularly with re-gard to compensation and assent, we conducted a retro-spective systematic evaluation of IP-A-CFs generated by local IRBs at different sites in response to the same multicenter clinical research protocols.

METHODS

Design

We performed a retrospective quasiexperimental study in which multiple local IRBs were exposed to identical study protocols, so that variation in IRB-approved forms indicate variation in IRB standards as opposed to varia-tion in study design. Three pharmaceutical companies each independently contracted with the Children’s Clin-ical Research Institute (CCRI), an academic clinClin-ical re-search organization located at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, to oversee the conduct of 3 national, phase III, multicenter clinical trials conducted for 3 pharma-ceutical products. For each of the 3 clinical trials, CCRI solicited principal investigators (PIs) at sites across the country, sending those who agreed to participate the standardized research protocols and template IP-A-CFs. PIs submitted the research protocols and forms to their IRBs for approval. After PIs made the alterations re-quired by their local IRBs, they each returned a copy of their IRB-approved IP-A-CFs back to CCRI for approval and for record keeping. This collection of IRB-approved forms allowed for a quasiexperimental retrospective re-view of informed consent and assent standards for each of the 3 clinical trials across multiple sites.

Subjects and Setting

In total, 55 different IRBs in 23 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico were exposed to 69 research protocol submissions divided among 3 different multi-institutional pediatric randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials.

Trial Study Protocols

The hypertension study (n ⫽ 36 submissions) was a

dose-escalation, randomized, withdrawal trial. Children with hypertension who responded to high dose medica-tion were randomized to either placebo or low-,

medi-um-, or high-dose ramipril. The pain study (n ⫽ 14

submissions) randomized children with breakthrough cancer pain to either oral transmucosal fentanyl citrate or placebo (with rapid availability of active rescue med-ication if needed for pain) after a dose-finding and phar-macokinetic phase. The acute hypoxemic respiratory

failure (AHRF) study (n⫽19 submissions) randomized

Analysis

Data were abstracted using a standard spreadsheet and included site-specific requirements for compensation and assent. Data were abstracted and cross-validated by 2 investigators (MBK and KSH).

Our unit of analysis was the discrete protocol submis-sion and review that yielded 69 IP-A-CFs. We did not study the 55 IRBs per se, because variability of standards within a given IRB for the same study precluded a clear classification of specific IRBs regarding their standards (eg, 1 IRB approved different levels of compensation for 2 different PIs using the same protocol). The data from all 69 of the IP-A-CFs were analyzed using simple de-scriptive statistics of proportions.

RESULTS

In our sample of 69 protocol submissions, IRBs demon-strated substantial variability in how they operationally defined the key elements of compensation and assent (Tables 1 and 2).

Compensation

All of the IRBs approved compensation for the hyper-tension study, which, among the 3 protocols in our study, imposed the greatest burden of participation, in-cluding 19 clinic visits and daily procedures at home during the early phases of the trial (Table 1). The max-imum level of monetary compensation varied by nearly eightfold, however, from $180 to $1425, with 22 IP-A-CFs (61%) offering between $500 and $1000 (Fig 1). In the pain study, 6 IP-A-CFs (43%) offered families com-pensation. In the AHRF study, 6 IP-A-CFs (32%) offered compensation for participation. Four IP-A-CFs (11%) in the hypertension study and 1 IP-A-CF (5%) in the AHRF

study offered reimbursement of actual documented ex-penses and are not included in Fig 1.

The form of compensation, as well as the recipient, also varied substantially among IRB-approved IP-A-CFs. A majority (29 [60%]) of the 48 IP-A-CFs offering com-pensation did not stipulate a form of payment. Nineteen (40%) clarified the form of payment, with 16 (33%) offering cash or check and 12 (25%) offering gift certif-icates. A total of 4 IP-A-CFs (8%) offered nonmonetary compensation, such as t-shirts or stuffed animals. Of the IP-A-CFs offering compensation, 25 (52%) did not indi-cate who was to receive the compensation. When the recipient was specifically stated, compensation was of-fered to children (8 [17%]), to parents (6 [13%]), or to both (9 [19%]). Of the 5 hypertension IP-A-CFs explic-itly offering compensation to the child participants alone, the children were offered sums of $180, $570, $760, $950, and $1425.

Assent

Overall, 57 IP-A-CFs (83%) included some method for documenting child participant assent (Table 2). Al-though children eligible for participation in the AHRF study were all seriously ill and required mechanical ven-tilation, 11 IP-A-CFs (58%) for the AHRF study included a mechanism for documenting assent. Of the 57 IP-A-CFs with assent documentation, 21 (37%) documented assent with only an assent signature line for the child on the parental permission form itself, whereas 36 (63%) included assent forms separate from the permission forms. Of those that included a separate assent form(s), 1 (2%) included a single separate assent form that used the same language as the permission form; 17 (30%) used a single separate assent form written in age-ad-justed language; 12 (21%) used a line on the permission form in addition to a single separate assent form written in age-adjusted language for different age-ranges of po-tential participants; and 6 (10%) used multiple separate assent forms with differentially simplified language for different age ranges of potential participants. Of the 57 IP-A-CFs that included some method for documenting assent, 31 (54%) stipulated specific but variable age ranges for providing assent (Fig 2). Only 5 IP-A-CFs (7%) overall provided a means of documenting a waiver of assent, 2 of which where in the AHRF study. Of the self-titled “informed consent forms,” 45 (65%) were addressed to the parents or guardians of the potential child participants, whereas the remaining 24 (35%) were addressed to the potential participants themselves despite their lack of standing to consent.

DISCUSSION

We found that IRBs differed substantially in how they operationalized compensation and assent in the in-formed permission procedure for pediatric human sub-jects research. Based on our data, we cannot determine

TABLE 1 Standards for Compensation Varied Substantially

Variable HTN Pain AHRF Total

Compensation offered 36 (100) 6 (43) 6 (32) 48 (70) Compensation provided for

Travel/parking 33 (92) 0 (0) 0 (0) 33 (48)

Inconvenience 19 (53) 1 (7) 2 (11) 22 (32)

Time 8 (22) 2 (14) 3 (16) 13 (19)

Food 5 (14) 0 (0) 1 (5) 6 (9)

Total compensation stated 13 (36) 5 (36) 5 (26) 23 (33) Actual expenses reimbursed 4 (11) 0 (0) 1 (5) 5 (7) Compensation given to

Child participant 5 (14) 1 (7) 2 (11) 8 (12)

Parent/guardian 5 (14) 0 (0) 1 (5) 6 (9)

Combination or both 6 (17) 1 (7) 2 (11) 9 (13)

Not stipulated 20 (56) 4 (29) 1 (5) 25 (36)

Form of payment

Cash or check 14 (39) 1 (7) 1 (5) 16 (23)

Gift certificate 10 (28) 0 (0) 2 (11) 12 (17)

Other 1 (3) 0 (0) 1 (5) 2 (3)

Not stipulated 20 (56) 5 (36) 4 (21) 29 (42) Nonmonetary compensation 4 (11) 0 (0) 0 (0) 4 (6)

whether these findings are generalizable to other local IRBs or to other research study protocols, identify the causes of this variation among IRBs, or answer defini-tively whether this variation is ethically problematic. These limitations not withstanding, however, the ex-treme variation observed among standards for compen-sation and assent warrants examination and discussion.

Compensation

Compensation ranged widely among institutions within the same multicenter trials, as well as among the ent multicenter trials. Indeed, given the eightfold differ-ence in compensation stated among the hypertension study IP-A-CFs, some IRBs may be either undercompen-sating or overcompenundercompen-sating participants.

Compensation for participation in research falls into 2 categories. First, compensation may aim to diminish fi-nancial disincentives to participation by reimbursing participants travel expenses and lost time, a practice that

is generally viewed as ethically appropriate.13,14Among

the 48 IP-A-CFs offering compensation, 33 (69%) of-fered reimbursement for travel and food expenses; 5 (10%) of those 33 reimbursed only documented

ex-penses that the participants had incurred, whereas the remainder offered a fix sum to cover estimated expenses (with the possibility of slight underpayment or overpay-ment unlikely to influence the decision regarding whether to participate; ref 15). Second, compensation may aim to motivate participation, either by expressing appreciation with a token gift (that is, an item of trivial value, such as a t-shirt, stuffed animal, or small gift certificate) or more forthrightly attempting to induce participants to accept the burdens of participation by

paying them.16 The impact of various compensation

schemes on research participation warrants further em-pirical investigation. Across the spectrum of compensa-tion, ranging from approaches that fail to reimburse the full amount of participant out-of-pocket expenses through to approaches that provide participants with payment well beyond the reimbursement of incurred expenses, these schemes may adversely affect research study access and participation decisions, especially for financially disadvantaged potential subjects.

FIGURE 2

The explicitly stated age range for documentation of assent varied considerably across IRB-approved A-CFs. Bars represent inclusive age ranges corresponding to each IP-A-CF with an explicitly stated age range(s); the first vertical bar, extending from age 7 to age 14, indicates a specified range of age 7 through age 13, or from the 7th birthday to the day before the 14th birthday. A break in a bar indicates that the overall specified age range was divided into 2 separate age ranges with 2 different forms of documentation.

TABLE 2 Standards for Obtaining and Documenting Assent Varied

Variable HTN Pain AHRF Total

Assent documented 32 (89) 14 (100) 11 (58) 57 (83)

Method of documentation

Signature line on permission form (PF) only 10 (28) 6 (43) 5 (26) 21 (30) Separate assent form (AF) with same language as PF 1 (3) 0 (0) 0 (0) 1 (1) Separate AF with age-adjusted language only 9 (25) 3 (21) 5 (26) 17 (25) Signature line on PF⫹separate AF with age-adjusted language 9 (25) 2 (14) 1 (5) 12 (17) Multiple AFs with different versions of age-adjusted language 3 (8) 3 (21) 0 (0) 6 (9)

Documented verbal explanation 2 (6) 2 (14) 2 (11) 6 (9)

Age range stipulated 17 (47) 9 (64) 5 (26) 31 (45)

Waiver of assent documented 1 (3) 2 (14) 2 (11) 5 (7)

Consent form addressed to:

Parent/guardian 20 (56) 7 (50) 18 (95) 45 (65)

Child participant 16 (44) 7 (50) 1 (1) 24 (35)

Data aren(%).

FIGURE 1

More investigation is also called for to understand the sources of the many variations in compensation discov-ered in our study. For instance, among the hypertension study sites, the specified compensation (when divided by the time required to participate) ranged from $7.50 to nearly $60 an hour, resulting in a difference in total compensation of more than $1200. Compensation also varied importantly across different studies: the pain study required participants to assume the burdens of hospitalization and additional travel, lodging, and meal expenses, but only 6 IP-A-CFs (43%) offered families compensation. By contrast, participants in the AHRF trial were already hospitalized with central lines, yet 6 IP-A-CFs (32%) offered compensation for participation, although there was virtually no extra financial burden. Excessive variability in compensation may be because of the discretion afforded IRBs by federal regulations. Although codifying strict methodologies to determine precise and inflexible levels of compensation would be incompatible with the need to tailor compensation stan-dards to local population characteristics and even indi-vidual family characteristics, the unlimited latitude that IRBs can exercise in approving participant compensation likely promotes excessive variability. No data were avail-able to determine whether the variability in our study flowed from differences in opinion with regard to appro-priateness of reimbursement payments, incentive pay-ments, or both forms of payment. Additional empirical work is necessary to determine which factors generate this variability and to what extent and to characterize the standards that IRBs use when approving compensa-tion amounts, whether explicitly or implicitly.

Finally, despite recent guidance by the Institute of

Medicine to clearly disclose the recipient of payments,16

we found that, among IP-A-CFs offering compensation, most (25 [52%]) were ambiguous about to whom the compensation was offered. When they were specific, compensation was offered with about equal frequency to parents (6 [13%]), to children (8 [17%]), or to both (9 [19%]). The impact of either ambiguity regarding who receives the compensation or explicit specification of these different recipients should be studied with regard to both willingness of participation and voluntariness of permission or assent.

Child Participant Assent

Among the documents examined in this study, IRBs exhibited substantially different standards for requiring and documenting children’s assent to participate in re-search. Of the 69 IP-A-CFs reviewed in this study, 57 (83%) included methods for documenting assent, and, among those, 31 (54%) stipulated age ranges for obtain-ing assent. Despite the 1978 recommendation by the National Commission for the Protection of Human Sub-jects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research that assent

be obtained from all childrenⱖ7 years of age,1the age

ranges specified in the IP-A-CFs spanned from a lower limit of 7–13 to an upper limit of 15–18 and were often (13 of 31) divided into 2 sequential age ranges, each regarding a different mode of documentation.

The interpretation of these data regarding the age range of assent specified in the IP-A-CFs is subject to 2 primary limitations. First, the absence of a stipulated age range on an assent form does not necessarily indicate that a given IRB does not have a standing policy that specifies an age range for attempting to obtain assent across all research protocols. Second, the specification of an assent age range in a IP-A-CF document may not necessarily imply that assent must be obtained but rather that a good-faith attempt to obtain assent must be un-dertaken. However, even with these caveats in mind, the presence of stipulated age ranges for obtaining assent are good indications that a given IRB intends investigators to obtain assent in the indicated manner and, at a mini-mum, provide an important nuance to the interpretation

of a previous survey finding10that 89% of IRB

chairper-sons support the use of stipulated age-cutoffs for cate-gorically determining which children are capable of as-sent.

Different definitions of assent may explain much of the variation among IP-A-CFs regarding age ranges for documentation of assent. Some definitions formulate assent as a form of consent, in which case it is important that the assenting child understand the risks and benefits of participation. The elements of assent, defined in this way, are similar to those of informed consent itself, and most IRBs self-consciously rely on regulations for in-formed consent forms when approving the content of

assent forms.10Other definitions of assent emphasize the

process of gauging the child’s preference, indifference, or disinclination to participate in a study that may require additional needle pricks or an extra hour in the hospital. Given this definition of assent, a child’s cognitive ability to understand and process the risks and benefits of par-ticipation is not important, and so children of a younger age are capable of assenting. The differences between these 2 definitions may explain why 1 IP-A-CF required assent for ages 15–18, for instance, whereas another required it for ages 7–13.

addressing the informed permission and consent forms of pediatric protocols with children incapable of consent may only generate confusion about who has the author-ity to make participation decisions and about the role and importance that age-appropriate child assent plays in the research process.

Assent practices should also be clarified at the oper-ational level with respect to what constitutes a good faith effort to obtain a child’s assent and when assent can be waived. The participants eligible for the AHRP study, for instance, were seriously ill with a life-threatening con-dition (all required mechanical ventilation and most were likely to be nonresponsive because of either their underlying illness or analgesic medications), yet 11 (58%) of the 19 IP-A-CFs in this study included docu-mentation of assent, whereas only 2 (10%) included documentation of waiver of assent.

CONCLUSIONS

Federal regulations implicitly grant IRBs significant dis-cretion for documentation of informed consent for hu-man subjects of research. Our sample of 69 sets of IP-A-CFs addressing 3 multicenter randomized, clinical trials reveals substantial variability in compensation and as-sent standards among IRBs across the country.

REFERENCES

1. National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research.The Belmont Report: Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research. Washington, DC: US Government Print Office; 1978 2. Annas GJ, Grodin MA.The Nazi Doctors and the Nuremberg Code: Human Rights in Human Experimentation. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1992

3. Faden RR, Beauchamp TL, King NMP.A History and Theory of Informed Consent. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1986

4. Levine RJ. Ethics and Regulation of Clinical Research. 2nd ed. Baltimore, MD: Urban & Schwarzenberg; 1986

5. Committee on Bioethics. Informed consent, parental permis-sion, and assent in pediatric practice. Committee on Bioethics, American Academy of Pediatrics.Pediatrics.1995;95:314 –317 6. Code of Federal Regulations. 45 CFR 46:116 –117.Federal Policy

for the Protection of Human Subjects (Subpart A). Washington, DC: United States Department of Health and Human Services; 1991 7. US Food and Drug Administration.Information Sheets: Guidance for Institutional Review Boards and Clinical Investigators. 1998 Up-date. Available at: www.fda.gov/oc/ohrt/irbs/default.htm. Ac-cessed October 30, 2005

8. US Department of Health and Human Services. 45 CFR Part 46: additional protections for children involved as subjects in re-search (hereafter “subpart D”).Fed Regist.1983;48:9814 –9820 9. Food and Drug Administration, US Department of Health and Human Services. 21 CFR Parts 50 and 56: additional safeguards for children in clinical investigations of FDA regulated prod-ucts.Fed Regist.2001;66:20589 –20600

10. Whittle A, Shah S, Wilfond B, Gensler G, Wendler D. Institu-tional review board practices regarding assent in pediatric re-search.Pediatrics.2004;113:1747–1752

11. McWilliams R, Hoover-Fong J, Hamosh A, Beck S, Beaty T, Cutting G. Problematic variation in local institutional review of a multicenter genetic epidemiology study.JAMA. 2003;290: 360 –366

12. Stair TO, Reed CR, Radeos MS, Koski G, Camargo CA. Varia-tion in instituVaria-tional review board responses to a standard pro-tocol for a multicenter clinical trial.Acad Emerg Med.2001;8: 636 – 641

13. Weise KL, Smith ML, Maschke KJ, Copeland HL. National practices regarding payment to research subjects for participat-ing in pediatric research.Pediatrics.2002;110:577–582 14. Dickert N, Grady C. What’s the price of a research subject?

Approaches to payment for research participation. N Engl J Med.1999;341:198 –203

15. Wendler D, Rackoff JE, Emanuel EJ, Grady C. The ethics of paying for children’s participation in research.J Pediatr.2002; 141:166 –171

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2005-1233

2006;117;1706

Pediatrics

Schreiner

Michael B. Kimberly, K. Sarah Hoehn, Chris Feudtner, Robert M. Nelson and Mark

and Assent Forms for 3 Multicenter Pediatric Clinical Trials

Approved Informed Permission

−

Comparison of 69 Institutional Review Board

Variation in Standards of Research Compensation and Child Assent Practices: A

Services

Updated Information &

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/117/5/1706

including high resolution figures, can be found at:

References

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/117/5/1706#BIBL

This article cites 9 articles, 3 of which you can access for free at:

Subspecialty Collections

_management_sub

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/administration:practice

Administration/Practice Management

following collection(s):

This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

Permissions & Licensing

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml

in its entirety can be found online at:

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

Reprints

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2005-1233

2006;117;1706

Pediatrics

Schreiner

Michael B. Kimberly, K. Sarah Hoehn, Chris Feudtner, Robert M. Nelson and Mark

and Assent Forms for 3 Multicenter Pediatric Clinical Trials

Approved Informed Permission

−

Comparison of 69 Institutional Review Board

Variation in Standards of Research Compensation and Child Assent Practices: A

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/117/5/1706

located on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 1073-0397.