Age and Height

at Diagnosis

in Turner

Syndrome:

Influence

of Parental

Height

Guy G. Massa,

MD, and

Magda

Vanderschueren-Lodeweyckx,

MD, PhD

From the Department of Pediatrics, Catholic University of Leuven, Leuven, Belgium

ABSTRACT. Age and height at diagnosis was studied in

100 patients with Turner syndrome: 41 with the 45,X

karyotype and 59 with various other karyotypes. In 15 patients diagnosis was made at birth. In the remaining patients median age at diagnosis was 12.9 years in those with 45,X karyotype and 11.6 years in the others. Mean ± SD height standard deviation score at diagnosis was -3.2 ± 0.9 for the patients with 45,X karyotype and -2.8 ± 0.9 for the others. A significantly negative correlation

was found between age and height standard deviation score at diagnosis (r = -.51; P < .005). Corrected mid parental height was significantly correlated with height standard deviation score at diagnosis (r = .49; P < .005),

but not with age at diagnosis (r = -.08). It is concluded

that although Turner syndrome is a congenital disorder, the diagnosis is usually made too late, at a chronological age when a marked height deficit is present. To make an early diagnosis, a cytogenetic examination should be nec-ommended for all girls with height more than 2 SD below the mean for age on more than 2 SD below corrected mid parental height. Pediatrics 1991;88:1148-1152; diagnosia, parental height, short stature, Turner syndrome.

ABBREVIATIONS. hGH, human growth hormone; TS, Turner

syndrome; SDS, standard deviation score; CMPH, corrected mid

parental height.

Several recent studies’4 have shown that treat-ment with human growth hormone (hGH) is effec-tive in promoting height velocity in patients with

Turner syndrome (TS). Although the ultimate

ef-fect on adult height remains to be determined, the increment in height velocity during treatment seems to be greater in young patients,2’4 stressing

Received for publication Dec 28, 1989; accepted Sep 29, 1990.

Reprint requests to (G.G.M.) Dept of Pediatrics, University

Hospital Gasthuisberg, Herestraat 39, B 3000 Leuven, Belgium.

PEDIATRICS (ISSN 0031 4005). Copyright © 1991 by the

American Academy of Pediatrics.

the potential importance of early diagnosis.

Al-though TS is a congenital anomaly, it appears that

the diagnosis of TS is usually suspected at a much

later age.57 Since in the literature few data are available on this aspect of the disorder, we studied

the age and height at diagnosis and the influence of parental height and spontaneous puberty in 100 patients with TS.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

The patients studied were referred to the division

of pediatric endocrinology between 1972 and

1988.

The Table shows the reasons for referral. The

din-ically suspected diagnosis of TS was confirmed by

chromosomal analysis of peripheral lymphocytes.

Forty-one patients had the 45,X karyotype whereas the remaining 59 had various mosaicisms or

struc-tural anomalies of the X chromosome (Table). In 2 patients cytogenetic examination ofperipheral lym-phocytes was normal but the diagnosis was con-firmed by careful cytogenetic analysis of cultured

skin fibroblasts. The age at which the diagnostically

cytogenetic examination was performed has been

considered as the age at diagnosis. In patients aged 3 years or older, height at the time of diagnosis was

expressed as standard deviation score (SDS) from

the mean of age-matched normal girls.8 Puberty

was evaluated according to the five stages of

Tan-ner.9 Only girls with breast stage 3 or more were

considered to have spontaneous puberty. Parental height was measured mostly by Harpenden stadi-ometer and the corrected mid parental height

(CMPH) was calculated.’#{176}

Results are expressed as median values or as the

Karyotype No. (5)* Reason for Referral (No.)

45,X 41 (2) Small stature (22)

Dysmorphic features (13)

Cardiopathy (4)

Absence of puberty (1)

Sleep disturbances (1)

45,X/46,XX 12 (8) Small stature (51)

45,X/46,XX/47,XXX 1 (1) Absence of puberty (3)

45,X/47,XXX 6 (4) Ambiguous genitalia (1) 45,X/46,XY 2 (0) Dysmorphic features (1) 45,X/47,XYY 1 (0) Obesitas (1)

45,X/46,Xi(Xq) 12 (1) Headache (1)

45,X/46,Xr(X) 6 (0) Psychological disturbances (1) 45,X/46,Xfr(X) 3 (0)

45,X/46,Xdel(Xq) 1 (0)

46,Xdel(Xp) 4 (4)

46,Xi(Xq) 5 (1)

46,Xi(Xq)/47,XXi(Xq) 1 (0)

* In this column, the number

spontaneous puberty.

in parentheses represents the number of patients with

15- - 45.Xkaryotype

LI

other karyotypesE

10-

C-a)

:

30

#{163}20

C

0

jun

0 5 10 15

age at diagnosis (years)

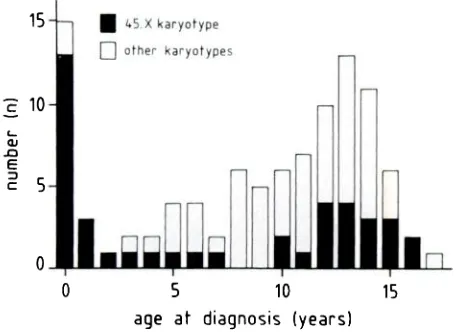

Fig 1. Distribution of age (years) at diagnosis in 100 patients with Turner syndrome.

1]

--th 151

-‘5 -4

II1

1 8

-2 -1 0

height at diagnosis (SOS)

Fig 2. Distribution of height, expressed as standard

de-viation score (SDS), at diagnosis in 81 patients with

Turner syndrome olden than 3 years of age. TABLE. Pertinent Data on 100 Patients With Turner Syndrome

RESULTS

Age at Diagnosis

Figure 1 shows the age distribution at diagnosis in 100 patients with TS. The distribution is bimo-dal, with a peak at birth and a second one around the age of 13 years. In 15 patients TS was diagnosed at birth because of dysmorphic features, mainly

edema of the hands or feet. Nearly all had the 45,X

karyotype.

One patient with ambiguous genitalia had a 45,X/46,XY karyotype. Between 1 and 3years, TS was diagnosed in only 3 more patients. Thereafter TS was diagnosed in a progressively increasing number of patients, with a peak between 12 and 14 years. Most of the patients with a

post-natal diagnosis were referred for short stature. Only

4 were seeking medical help for primary

amenor-rhea and another 4 were referred by the pediatric cardiologist. When the patients in whom TS was diagnosed at birth were excluded, median age at diagnosis was 12.9 years for those with the 45,X karyotype and 11.6 years for the others (Mann-Whitney U test; P > .05).

Height at Diagnosis

Figure 2 represents the distribution of height, expressed as SDS, at the time of diagnosis in 81 patients aged 3 years or older at time of diagnosis.

Height SDS ranged from -0.8 to -5.2 with a mean ± SD of -3.2 ± 0.9 for the patients with 45,X

karyotype,

and -2.8 ± 0.9 for the others (unpaired Student’s t test; P > .05). Height was more than 2 SD below the mean for chronological age in 6645 xkaryofype

0 L,1 U, -2 0 C ‘ni

-#{149}0 ‘ni 4 0 0+ +: 0

0 0 0

0 0

.

0 0 0 .80 c#{149}

- 0 %c .oo

00 I45X karyotl

-

0 other karyotypes‘I 10 15

age at diagnosis (years)

Fig 3. Relationship between age (years) and height

(standard deviation scone [SDS]) at diagnosis in 81

pa-tients with Turner syndrome (r = -.51; P < .005).

(81%) of 81 patients. As shown in Fig 3, a negative

correlation was found between age and height SDS at diagnosis (r = -.51; P < .005).

Influence of Parental Height

Mean ± SD height of the mothers and fathers was 160.6 ± 6.0 cm and 174.0 ± 6.6 cm, respectively.

Expressed as SDS for the normal adult population,

it was -0.3 ± 1.0 and -0.1 ± 1.0, respectively. In 5 mothers and 4 fathers height was more than 2 SD

below the mean for the normal adult population.

Corrected mid parental height was positively

cor-related with height SDS for chronological age at

diagnosis (r = .49; P < .005; n = 81), but not with

age at diagnosis (r = -.08; not significant). Height at diagnosis was more than 2 SD below CMPH in 64 (79%) of 81 patients aged 3 years or older. Considering both criteria (>2 SD below the mean

for chronological age or >2 SD below CMPH), 91% of the patients were found to be too small.

Influence of Spontaneous Puberty

Twenty-one patients showed signs of sponta-neous puberty. In none of them had TS been diag-nosed at birth. Their median age at diagnosis was 12.2 years. In TS patients without spontaneous

puberty it was 9.7 years (Mann-Whitney U test; P

< .05). When the patients in whom TS was diag-nosed at birth were excluded, the difference

be-tween both groups was no longer significant (12.2

years vs 12.3 years; Mann-Whitney U test; P >

.05). Mean ± SD height SDS at diagnosis was -2.7 ± 0.8 for the patients with spontaneous puberty and -3.0 ± 1.0 for the others (unpaired Student’s t

test; P > .05).

DISCUSSION

This study clearly shows that the majority of the cases of TS are diagnosed at a late chronological

age, when a marked height deficit is present. In only 15% of the patients the diagnosis was made at

birth, most of them having the 45,X karyotype.

This figure is comparable with those reported by Palmer and Reichmann5 and Park et al,6 who found

that TS was diagnosed at birth in, respectively,

11% and 23% of the patients, all with the 45,X

karyotype.

In 56% of our patients TS was diagnosedafter

the age of 10 years, a finding identical withthat (53%) reported by Park et al.6 In a transcul-tural study Nielsen and Stradiot7 found that the final diagnosis of TS was made before the age of 15 years in only 51% of the patients, with a variation

from

0% in Hungary to 70% in Canada and Den-mark.Short stature was the principal cause for referral. All patients had indeed a negative value for height SDS and although some were above -2 SDS, the

lower normal limit, most of them had a serious

height deficit at the time of diagnosis, comparable

with that reported in patients with growth hormone

deficiency.1”2 Short stature is the most consistent

clinical finding in TS5”3 and is caused by an

intra-uterine growth retardation and a stunted growth between a bone age of 2 and 11 years.’4’15 As

ex-pected from the disease-specific growth charts,’4’6 we found a negative correlation between the age

and height at diagnosis. This means that most of

the patients suffered from short stature for several years before the diagnosis ofTS was made, stressing once more that the diagnosis of TS is still easily missed.

In TS patients significant positive correlations between parental height and that of their mature

offspring have repeatedly been reported.’5”72#{176} We

recently showed that in girls with TS older than 6

years of age, significantly positive correlations, comparable with those reported in normal

chil-dren,21 are found between height at different ages and parental height.’5 In the present study a signif-icant correlation was found between height at

di-agnosis and CMPH, suggesting that in general, the taller the parents are, the taller the child with TS will be at diagnosis; this observation is similar to

one reported in patients with growth hormone de-ficiency.22 No relationship was found between

pa-rental height and the age at diagnosis. In 81% of

diagnosis of TS has to be excluded not only in girls whose stature is more than 2 SD below the mean for chronological age, but also and more particularly in those whose height is more than 2 SD below

CMPH. This seems to be a most important

auxo-logical finding, very helpful in the differential

di-agnosis of small stature since the typical dys-morphic features of TS may be moderate to almost absent.23

Signs of spontaneous puberty occur in 10% to 20% of the patients with TS6”5’24 and are accom-panied by a small growth spurt.’5 Prepubertal growth and final adult height are, however, similar to those of TS patients without spontaneous pu-berty.’5 In the present study, no significant differ-ences were found for age and height at diagnosis between patients with and without spontaneous puberty. It seems, however, very likely that in a considerable number of TS patients with signs of puberty, the diagnosis is not being made by the pediatrician but at a later age by the gynecologist because of fertility problems. In a recent study of Hens et al,25 sex chromosome anomalies were found in 18 of 86 adult women consulting for primary or secondary amenorrhea.

In patients with growth hormone deficiency, total height gain during long-term substitution therapy with hGH is inversely related to the age at start of

therapy.22 The same may hold true for TS patients treated with hGH because the increment in height velocity is inversely related to the chronological or

bone age at start oftreatment.2’4 Although the effect of hGH therapy on final height remains to be

determined, it is logical to assume that young pa-tients with a great growth potential might benefit more from this treatment. Additional potential

ben-efits of early growth-promoting therapy are the normalization of height during childhood, which is likely to influence the child’s self-image and peer relationships,’ and the possibility of introducing feminizing doses of estrogen at a more physiological age than has been generally used in the past.26 It has been stated that growth-promoting treatment

has to be considered in TS patients as soon as height velocity falls below the 25th percentile for age.27 This stresses the need for early diagnosis.

In conclusion, although TS is a congenital anom-aly, the diagnosis is usually made too late, at a chronological age when a marked height deficit is present. Parental height seems to influence height, but not age at the time of diagnosis. To make an early diagnosis and eventually optimize treatment, a cytogenetic examination should be recommended in girls with small stature more than 2 SD below the mean for chronological age or below CMPH, even in the absence of dysmorphic features. In

addition, it needs to be stressed that even in the presence of signs of spontaneous puberty, TS is not

excluded per se and should not be overlooked.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported, in part, by a grant from the

Belgian “Nationaal Fonds voor Geneeskundig

Weten-schappelijk Onderzoek” (3.0047.89).

We thank Prof Paul Malvaux for permission to analyze

his patient data, and Dr Lutgarde Dooms for devoted

patient care.

REFERENCES

1. Rosenfeld RG, Hintz RL, Johanson AJ, et al. Three-year

results of a randomized prospective trial of methionyl

hu-man growth hormone and oxandrolone in Turner syndrome.

J Pediatr. 1988;113:393-400

2. Takano K, Shizume K, Hibi I, and Committee for the

Treatment of Turner’s Syndrome. Turner’s syndrome:

treat-ment of 203 patients with recombinant human growth

hor-mone for one year. Acta Endocrinol. 1989;120:559-568

3. Rongen-Westerlaken C, Fokker MH, Wit JM, et al.

Two-year results of treatment with methionyl human growth

hormone in children with Turner’s syndrome. Acta Paediatr

Scand. 1990;79:658-663

4. Vanderschueren-Lodeweyckx M, Massa G, Maes M, et al.

Growth promoting effect of growth hormone and low dose

ethinyl estradiol in girls with Turner syndrome. J Clin

Endocrinol Metab. 1990;70:122-126

5. Palmer CG, Reichmann A. Chromosomal and clinical

find-ings in 1 10 females with Turner syndrome. Hum Genet.

1976;35:35-49

6. Park E, Baily JD, Cowell CA. Growth and maturation of

patients with Turner’s syndrome. Pediatr Res. 1983;17:1-7

7. Nielsen J, Stradiot M. Transcultural study of Turner’s

syn-drome. Clin Genet. 1987;32:260-270

8. Tanner JM, Whitehouse RH, Takaishi M. Standards from

birth to maturity for height, weight, height velocity, weight velocity: British children 1965. Arch Dis Child.

1966;41:454-471, 613-635

9. Tanner JM. Growth atAdolescence. 2nd ed. Oxford, England:

Blackwell; 1962.

10. Tanner JM, Goldstein H, Whitehouse RH. Standards for

children’s height at ages 2-9 years, allowing for height of

parents. Arch Dis Child. 1970;45:755-762

11. Herber SM, Milner RDG. When are we diagnosing growth

hormone deficiency? Arch Dis Child. 1986;61:110-112

12. Tanner JM, Whitehouse RH, Hughes PCR, Vince FP. Effect

of human growth hormone treatment for 1 to 7 years on

growth of 100 children, with growth hormone deficiency,

low birthweight, inherited smallness, Turner’s syndrome,

and other complaints. Arch Dis Child. 1971;46:745-782

13. Lippe BM. Primary ovarian failure. In: Kaplan SA, ed.

Clinical Pediatric Endocrinology. Philadelphia, PA: WB

Saunders Company: 1990:325-366

14. Ranke MB, Pfluger H, Rosendahi W, et a!. Turner

syn-drome: spontaneous growth in 150 cases and review of the

literature. Eur J Pediatr. 1983;141:81-88

15. Massa G, Vanderschueren-Lodeweyckx M, Malvaux P.

Lin-ear growth in patients with Turner syndrome: influence of

spontaneous puberty and parental height. Eur J Pediatr.

1990;149:246-250

16. Lyon AJ, Preece MA, Grant DB. Growth curve for girls with

Turner’s syndrome. Arch Dis Child. 1985;60:932-935

17. Brook CGD, M#{252}rsetG, Zachmann M, Prader A. Growth in

children with 45,XO Turner’s syndrome. Arch Dis Child.

1974;49:789-795

18. Brook CGD, Gasser T, Werder EA, Prader A,

parents and mature offspring in normal subjects and in

subjects with Turner’s and Klinefelter’s and other

syn-dromes. Ann Hum Biol. 1977;4:17-22

19. Demetriou E, Emans SJ, Crigler JF. Final height in

estro-gen-treated patients with Turner syndrome. Obstet Gynecol.

1984;64:459-464

20. Lenko HL, S#{246}derholm A, Perheentupa J. Turner syndrome:

effect of hormone therapies on height velocity and adult

height. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1988;77:699-704

21. Tanner JM, Goldstein H, Whitehouse RH. Standards for

children’s height at ages 2-9 years allowing for height of

parents. Arch Dis Child. 1970;45:755-762

22. Vanderschueren-Lodeweyckx M, Van den Broeck J, Wolter

R, Malvaux P. Early initiation of growth hormone

treat-ment: influence on final height. Acta Paediatr Scand Suppl.

1987;337:4-11

23. Craen M, Lemay P, Dooms L, et al. Turner syndrome:

variability in clinical appearance. Acta Paediatr BeIg Suppi.

1981;19:145-152

24. Hibi I, Tanae A. Final height in Turner syndrome with and

without gonadal function. In: Rosenfeld RG, Grumbach

MM, eds. Turner Syndrome. New York, NY: Marcel Dekker, Inc; 1990;163-181

25. Hens L, Devroey P, Van Waesberghe L, Bonduelle M, Van

Steirteghem AC, Liebaers I. Chromosome studies and

fer-tility treatment in women with ovarian failure. Clin Genet.

1989;36:81-91

26. Rosenfeld RG. Update on growth hormone therapy for

Turner’s syndrome. Acta Paediatr Scand SuppL

1989;356:103-108

27. Brook CGD. Turner syndrome. Arch Dis Child.

1986;61:305-309

Grand Island, Nebraska

December 5, 1910

Whereas: The football season for 1910 closed for the year on Thanksgiving day, thereby relieving many of the Fathers and Mothers of our land of nervous

strain and anxiety for the fear that a dead or crippled son might be returned to the home as a price paid for the sport; it is proper at this time that an account be taken to determine whether or not the school officers and teachers ought

further

to encourage a game so destructive to life and so injurious to limb, and whereas, the game for the season last past has generally been conducted underthe so-called reform rules whereby the hazardous character of the game was supposed to be largely eliminated, yet the fatalities and injuries sustained for the year are as great, or nearly so, as resulted under the old rules in former years. Some of the most earnest advocates of the game now concede that it is utterly impossible under the strictest regime to relieve the game of the many dangerous plays incident thereto. Now, therefore, be it resolved that it is the sense of this Board that the game of football should no longer be conducted in connection with the public schools with the consent of or under the supervision of the Board, Officers or Teachers, and in lieu thereof a course in physical culture under competent teachers should be provided for in which all attending the public schools should participate.

EDWARDS

In cleaning the files in the Superintendent’s Office we found the attached letter concerning the

sport of football. You will note the date (December 5, 1910). We assume this letter was written by

the same Mr. H. A. Edwards who was a member of the Board of Education in 1902.

![Fig 3.Relationshiptientsbetweenage(years)andheight(standarddeviationscone[SDS])atdiagnosisin81pa-withTurnersyndrome(r=-.51;P <.005).](https://thumb-us.123doks.com/thumbv2/123dok_us/101618.1510526/3.612.75.293.529.691/fig-relationshiptientsbetweenage-years-andheight-standarddeviationscone-sds-atdiagnosisin-withturnersyndrome.webp)