The Relationship between Coping Strategies and Internalizing Symptoms in Young Adulthood Lauren M. Everhart

Distinguished Majors Project University of Virginia

May, 2012

Advisor: Joseph P. Allen, Ph.D.

Acknowledgements

Foremost, I would like to thank Professor Joseph Allen and Joanna Chango for their invaluable guidance throughout the DMP process. I am indebted to them for their constant availability, support and advice. I am extremely grateful for the countless hours Joanne gave guiding me through the steps of this project; from initially teaching me how to use the data analysis computer software to making suggestions for improvement in the final stages of writing. I am grateful for Joseph Allen for his willingness to meet with me and teach me how to ask the correct research question.

I would also like the thank Professor Gerald Clore and Professor Vikram Jaswal for their support, guidance, and encouragement this past year. They both spent this past year investing into my work and helping prepare me for the completion of this project. Finally, I would like to thank Professor N. Dickon Reppucci for agreeing to be my second reader despite his busy schedule.

Abstract

The relationship between specific positive and negative coping strategies and internalizing symptoms was investigated using a structural cross-lagged regression model of analysis. The study used longitudinal data from a diverse community sample of 184 target participants and their closest peers. As hypothesized, positive coping strategies (e.g. positive reframe and humor) predicted relative decreases in self reported anxiety one year later while negative coping

strategies (e.g. venting of emotions and substance use) predicted relative increases in self reported depressive symptoms one year later. The relationships between positive coping strategies and depressive symptoms, and negative coping strategies and anxiety, were not

significant. The current findings indicate the potential importance of specific coping strategies in the development and maintenance of internalizing symptoms. Potential explanations and

The Relationship between Coping Strategies and Internalizing Symptoms in Young Adulthood

Emerging Adulthood is a period defined by identity exploration, instability, and feeling “in-between” (Arnett, 2004). Although this age allows for unparalleled opportunities and hope for the future it can also be a stressful time marked by difficult decisions, changes, and life transitions (Arnett, 2004). This period may be a time when individuals are at a heightened risk for depression and anxiety, as research has shown that psychosocial stress is a significant predictor for psychopathology (Grant et al., 2003). Distressing situations incite individuals to find various ways to handle stress. Some tactics are more adaptive than others. A large body of research has been dedicated to understanding how people cope with these distressing situations, why they choose certain coping strategies compared to others, and what impacts their choices have on their mental health (Billings & Moos, 1984; Compass, Conner-Smith, Saltzman,

Thomsen, & Wadsworth, 2001; Horwitz, Hill, & King, 2010). The current study investigates the relationship between coping behavior and internalizing problems, specifically depression and anxiety, in a diverse community sample of young adults.

Coping can be defined as “constantly changing cognitive and behavioral efforts to manage specific external and/or internal demands that are appraised as taxing or exceeding the resources of the person” (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984, p. 141). Coping, according to this

definition, can include strategies used to decrease negative emotions as well as strategies used to solve a problem that is causing distress. This definition allows for anything the person thinks or does, in order to manage stress or a difficult situation, to be considered coping, regardless of whether it is helpful or not.

Research has focused on investigating the significance of specific coping strategies as they relate to and predict internalizing symptoms. A vast amount of research has been conducted on the direct relationships between coping and depression and anxiety. Over the years theorists and researchers have identified different strategies as being adaptive or maladaptive. A recent meta-analysis examining the associations between emotion regulation and psychopathology found links between coping behavior and mental health (Aldao, Nolen-Hoeksema, & Schweizer, 2010). The meta-analysis demonstrated that many adaptive strategies are related to positive mental health outcomes while maladaptive coping strategies are related to increased depression, anxiety, and other negative mental health outcomes. However, much of this research was cross sectional and investigated psychopathology in clinical and college samples. It is possible that coping strategies and psychopathology are manifested differently in clinical samples compared to community samples. For example, in a clinical sample, depression may have a greater influence on coping behavior because the depressive symptoms may be so great that the individual does not have the cognitive or emotional resources to employ positive coping

strategies and therefore chooses to engage in a more negative style of coping. It is possible that, in a community sample, individuals experience lower levels of depressive symptoms and

therefore have more cognitive and emotional resources to allocate towards coping, rendering them more able to employ a positive method of coping. It is then possible that, in the community sample, the use of positive coping strategies aids in maintaining lower levels of depressive symptoms. Little research has investigated this possibility that internalizing problems manifest themselves differently in non-clinical populations as well has how coping strategies are utilized in non-clinical populations.

In past research,positive reappraisal was proposed as an adaptive way of regulating emotions and handling distress. Positive reappraisal involves imposing positive interpretations or perspectives on a situation causing distress. It involves reinterpreting one’s circumstances and cognitive thoughts and “putting a positive spin” on them, so as to view their current situation in a more positive light. It was proposed that maladaptive reappraisal processes are at the root of depression and anxiety (Beck & Steer, 1976). This assumption suggests that positive reappraisal, as a coping strategy, may serve as a protective factor against negative mental health outcomes, such as depression and anxiety. It also suggests that the absence of adaptive positive reappraisal or the use of negative cognitive appraisals can serve as a risk factor for developing negative mental health outcomes. Gross and John (2003) found that, in a sample of college students, positive reappraisal was positively correlated with greater expression and experience of positive emotion, as reported by the target participants’ closest peer. It was also negatively correlated with negative emotion expression and experience. Providing further evidence for the

relationship between positive mental health and positive thinking, one study found that optimists displayed smaller increases in depression and stress during their first semester of college when compared to pessimists (Brissette, Scheier, & Carver, 2002). Thinking optimistically potentially serves as a buffer against the negative effects depression and stress. However, both optimists and pessimists still displayed increases in depression and stress upon starting college, which emphasizes young adulthood, and its accompanying challenges, as a stressful time period. Also, this study investigated how coping was related to changes in depression and stress over time, but coping was only assessed at the beginning of the semester. Thus, the relationship between depression, stress, and changes in coping over time, was unexamined. Furthermore, positive reappraisal serves as the backbone for cognitive behavioral therapy, which is widely used for its

efficacy in decreasing psychological stress and improving mental health (Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979).

Another coping strategy that has demonstrated buffering effects in stressful or aversive situations is the use of humor. It has been suggested that humor plays a role not only in managing stress but in enhancing the experience of positive life moments (Martin, Kuiper, Olinger, & Dance, 1993). For example, in a college sample, greater levels of humor were associated with a more positive self-concept, more positive and self-protective cognitive

appraisals in the face of stress, and greater positive affect in response to life events. Importantly, the use of humor has been associated with lower loneliness, lower depression, and higher self-esteem in college students (Overholser, 1992). These positive effects of humor were proposed to be rather short-term in nature, having disappeared when the subjects were re-tested seven weeks later. The existing literature, however, has not explored how humor and internalizing symptoms change over a period of time greater than two months. Interestingly, past research has also not investigated whether these effects are present in non-college samples of young adults.

Nevertheless, findings suggest that humor, as a coping strategy, was inversely related to the stress and depressive symptoms, providing further evidence that adaptive coping strategies help individuals manage stress and difficult situations in ways that promote positive mental health outcomes.

Maladaptive coping strategies, in contrast to adaptive coping strategies, are typically related to negative mental health outcomes, such as increases in depression and anxiety. The meta- analysis conducted by Aldao and colleagues (2010) described specific maladaptive strategies that have been linked with increased depressive symptoms and anxiety. For example, in a clinical sample of adults, emotion based coping was shown to be linked with relative

increases in depression (Billings & Moos, 1984). Some individuals tend to focus on their negative emotions, its causes, and consequences. Researchers argue that this type of rumination is related to relative increases in self-reported depressive symptoms (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991). A study conducted using participants who recently experienced the loss of a loved one found that individuals with a ruminative coping style at one month reported greater levels of depression 6 months later (Nolen-Hoeksema, Parker, & Larson, 1994). Rumination has not only been linked with increased depression but has been positively associated with the duration of depressive episodes (Nolen-Hoeksema, Morrow, & Frederickson, 1993). Regression analyses, conducted using an undergraduate college sample, suggested that the more participants engaged in

ruminative coping, the longer their periods of depressive episodes, even after controlling for the initial severity of reported depression. However, past research has focused on how rumination is related to changes in depression over time and has not examined how depression is related to changes in rumination over time.

Rumination is generally viewed as an internal coping strategy that involves lingering cognitively on a stressful or negative situation. Venting potentially can be viewed as

rumination’s external counterpart. Venting, as a coping strategy, involves lingering on negative emotions by continuing to talk about them. This verbal expression stems from negative

cognitions, because in order to verbalize an idea or emotion an individual must think about it first. Therefore it is possible that rumination and venting operate in a similar manner, and stem from the same or similar underlying mechanisms, but express themselves in different ways, with one being more internal and the other external. Venting, like rumination, may do more harm than good, in relation to mental health, but little research has investigated the effects of this coping strategy on mental health.

While evidence suggests that focusing on negative emotions is maladaptive, avoiding the experience of emotions and distressing situations may also be maladaptive. The meta-analysis demonstrated that avoidance was associated with negative mental health outcomes, such as depression and anxiety (Aldao et al., 2010). For example, the high use of avoidance coping was shown to predict postnatal depression (Honey, Morgan, & Bennet, 2003). Avoidance-based coping also predicted higher levels of depression in an urban sample consisting of young adults who had experienced being physically victimized (Hassan, Mallozzi, Dhingra, Niti, & Sara, 2011). Experiential avoidance is described as “the unwillingness to experience unwanted thoughts, emotions, or bodily sensations and an individual's attempts to alter, avoid, or escape those experiences” (Plumb, Orsillob, & Luterekc, 2004). Avoidant coping includes strategies that orient the individual away from the source of stress. For example, substance use can be a form of avoidance. Avoiding a distressing situation or emotion may be the direct goal, but using drugs or alcohol as an escape is the coping strategy used to achieve that goal. A great deal of research has examined the links between substance use and psychopathology. For example, in a college sample substance abuse was shown to have maladaptive psychological effects and is associated with major depression (Deykin, Levy, & Wells, 1987). Additionally, research has shown that depression and substance use disorders are often comorbid in the general population (Swendenson & Merikangas, 2000). Interestingly, little research has been conducted

investigating substance use, specifically, as a coping strategy. It is logical, considering the general negative effects of substance use that substance use as a coping strategy is potentially maladaptive. Maladaptive coping strategies can put individuals at risk for developing

internalizing disorders. Coping behavior and the strategies one chooses to employ when stressed are important because they affects one’s mental health and therefore their overall quality of life.

Coping strategies and their outcomes have significant implications for the individual as well as society. According to the National Institute of Mental Health mood disorders have a cumulative twelve month prevalence affecting 9.5% of the adult population (National Institute of Mental Health [NIMH], 2012). Half of these cases are classified as severe (e.g. 4.3% of the adult population). Generalized Anxiety Disorder affects approximately 3.1% of the adult population, with 32.3% of these cases is classified as severe (NIMH, 2012). Depression and anxiety are not only a burden for the individual but these disorders create a burden for society as a whole. In 1990, the estimated annual cost of depression was $43.7 billion (Greenberg, Stiglin, Finkelstein, & Berndt, 1993). This estimate included direct costs of medical and psychiatric care, mortality costs arising from depression- related suicides, and costs associated with depression in the workplace. In 2002 the impact of depression on labor costs (e.g. work absence and reduced performance while at work) in the US workforce was an estimated $44 billion. Generalized Anxiety disorder follows a similar cost pattern and it was estimated that the annual cost in 1990 was between $42 and $47 billion (Wittchen,2002). Depression and anxiety have significant individual and societal costs, therefore the investigation of the relationship between these internalizing problems and coping strategies is essential.

Over the years theorists have attempted to explain the relationship between internalizing problems and coping behavior. Theorists have proposed that coping and emotion have a

mutually reciprocal relationship (Folkman & Lazarus, 1988). The behavioral flow begins when a stimulus is encountered. At this moment, a cognitive appraisal is made which influences coping, which influences the person-environment relationship, and then the emotional response. For example, if a person is confronted with a stressful situation it can be appraised in many ways; as threatening, challenging, or even beneficial. If it is appraised as threatening, denying

the situation may follow as a coping strategy and the emotional response may include stress and anxiety. A cyclical relationship ensues as the coping and emotional responses influence and feed each other. In this dynamic relational pattern changes in emotional response may alter the coping mechanism employed and vice versa. Other theorists have proposed a similar reciprocal relationship between cognitions and depression.

The cognitive model of depression emphasizes that negative cognitions can influence the development and maintenance of depression (Teasdale, 1983). It is proposed that negative cognitions produce depression which increases the probability that a person will experience the negative cognitions. This creates a cycle where the negative cognitions feed depression and depression feeds the cognitions which can intensify depression. These evidence based theories demonstrate that a reciprocal relationship may exist between coping behaviors and internalizing problems, such as depression and anxiety. Extensive research has been conducted on coping strategies as predictors of internalizing symptoms; however, very little research has been conducted investigating whether a reciprocal relationship exists between specific coping styles and internalizing symptoms. For example, how mental health predicts or causes changes in coping behavior over time. Furthermore, little research has been conducted investigating whether or not these two variables operate in a mutually reciprocal relationship, meaning that both variables have equal weight in driving the cyclical relationship.

The present study seeks to improve our understanding of the relationship between specific coping strategies and internalizing symptoms in a diverse community sample of young adults. Past research suggests that specific adaptive coping strategies have positive effects on mental health and are related to relative decreases in reported psychopathology while specific maladaptive coping strategies have negative effects on mental health and are related to relative

increases in reported psychopathology (Aldao et al., 2010). However, whether internalizing symptoms and coping change and influence each other over time is not fully understood. For example, little research has been conducted investigating how internalizing symptoms are related to changes in coping behavior over time. Therefore, it is possible that internalizing symptoms actually cause negative coping strategies, or prevent the engagement in positive coping

strategies.

To begin to further understand the relationship between coping and internalizing symptoms, research is now needed that is longitudinal and that assesses changes in coping behavior and internalizing symptoms over time. The current longitudinal, multi-reporter study sought to address these concerns. This study explored how depressive and anxiety symptoms and coping change over time, and examined predictions of change after accounting for baseline levels of reported coping and symptoms. The possibility that coping and internalizing symptoms operate in a reciprocal relationship was examined by utilizing a cross-lagged regression

approach. Although, it was expected that coping strategies would predict changes in symptoms over time, the main goal of this study was to examine whether or not a mutually reciprocal relationship exists between the two constructs. For example, it is well understood that coping influences symptoms over time, but what is less understood is whether or not symptoms

influence coping over time. Based on past research on the relationships between specific coping strategies and psychopathology, it was hypothesized that the specific positive coping strategies, positive reframing and humor, would show negative associations with depressive symptoms and anxiety over time. It was also hypothesized that the negative coping strategies, venting of emotions and substance abuse, would show positive associations with depressive symptoms and anxiety over time.

Method Participants and Procedure

This study is drawn from a larger longitudinal investigation of adolescent social

development in familial and peer contexts and included 184 participants (86 male and 98 female) and their closest friends. The sample was racially/ethnically and socioeconomically diverse: 58% identified as Caucasian, 29% identified as African America, and 13% identified as other and/or mixed minority groups. The participants’ parents reported a median family income in the US$40,000- US$59,999 range during the first year of the study (M=$43,500, SD=$22,580).

Participants were initially recruited from the seventh and eighth grades of a public middle school drawing from suburban and urban populations in the Southeastern United States.

Participants were recruited via an initial mailing to all parents of students in the school along with follow-up contact efforts at school lunches. Families of participants who indicated they were interested in the study were contacted by telephone. Of all students eligible for

participation, 63% agreed to participate. The resulting sample was similar to the larger

community population in terms of both socioeconomic status and racial/ethnic background. All participants provided informed consent before each interview session. Interviews took place in private offices within a university academic building.

The current study uses 2 waves of measurement, collected one year apart, to investigate how coping behavior and internalizing problems influence each other over time. Participants were approximately 22 (age: M = 21.66, SD = .96) at the first wave of data collection and were approximately 23 (age: M = 22.80, SD = .96) during the second wave of measurement. During these two waves the target participants were asked to nominate their “closest friend” to be included in the study. This gives the clearest possible picture of the participant’s recent close

peer interactions during early adulthood, and eliminates the problem of repeatedly assessing a peer who may no longer be close to the target participant, perhaps due to circumstances that have nothing to do with the friendship (e.g., geographic moves). If target participants appeared to have any difficulty naming close friends, it was explained that naming their “closest” friend did not mean that they were necessarily very close to this person, but rather that they were close relative to other acquaintances they might have. The average length of friendship was approximately 8 years (M = 7.66, SD = 5.71) during the first wave and approximately 9 years (M = 8.69, SD = 5.95) during the second. The target participants and their close peers also reported how close their friendship was. This was assessed using a 5-point Likert scale from 1- “not close” to 5- “very close”. Participants reported that their relationship was very close during the first wave (target participants: M = 4.46, SD = .68; peers: M = 4.64, SD = .62) and during the second (target participants: M = 4.38, SD = .88; peers: M = 4.57, SD = .73).

In the initial introduction and throughout each session, confidentiality was assured to all participants. A Confidentiality Certificate, issued by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services protected all data from subpoena by federal, state, and local courts.

Measures

Coping behavior. The target participants’ coping behavior was assessed using closest peer ratings on the brief COPE inventory (Carver, 1997), which was administered to the target participant’s closest peer. Each of the subscales of the brief COPE are comprised of 2 items assessed on a 4-point Likert scale asking the close peer if the target participant engages in the coping strategy “not a lot,” “a little bit,” “a medium amount,” or “a lot”.

Positive coping behavior. Positive coping behaviors investigated by the current study include the following subscales: positive reframing, the use of instrumental support, and humor.

The positive reframing scale assesses individuals’ attempts to view their situation in a more positive way. This scale includes items such as, “He/she usually looks for something good in what is happening,” and, “He/she usually tries to see it in a different light, to make it seem more positive”. The instrumental support scale assesses individuals’ attempts to seek out advice about how to handle a situation. This scale includes items such as, “He/she usually tries to get advice or help from other people about what to do,” and, “He/she usually gets help and advice from other people”. The humor scale assesses individuals’ attempts to make light of and joke about their current situation. This scale includes items such as, “He/she usually makes jokes about it,” and “He/she usually makes fun of the situation”. Internal consistency for each subscale was good (Cronbach’s α for Positive Reframing subscale = .76 at age 22 and .87 at age 23;

Instrumental Support subscale = .90 at age 22 and .91 at age 23; Humor subscale = .90 at age 22 and .84 at age 23).

Negative coping behaviors. Negative coping behaviors investigated by the current study include the following subscales: venting of emotions and substance abuse. The venting of emotions scale aims to assess individuals’ efforts to release their emotions. This scale includes items such as, “He/she usually says things to let their emotions escape” and, “He/she usually expresses their negative feelings”. The substance use scale measures individuals’ efforts to use drugs or alcohol to handle a difficult situation. This subscale includes items such as, “He/she usually uses alcohol or other drugs to make themselves feel better,” and, “He/she usually try uses alcohol or other drugs to help them get through it”. Internal consistency for each subscale was marginal to adequate (Cronbach’s α for Venting of Emotions subscale = .55 at age 22 and .66 at age 23; Substance Abuse subscale = .91 at age 22 and .94 at age 23).

Depressive Symptoms. The target participants’ depressive symptoms were assessed using self reports on the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck & Steer, 1987). The BDI is a 21-item self report questionnaire designed to assess the severity of depression in adolescents and adults. Each item is rated on a 4-point scale (0–3), producing a summary score, with a higher score indicating more severe depressive symptoms. The internal consistency for this measure was good (Cronbach’s α = .88 at age 22 and 23).

Anxiety. The teens’ anxiety was assessed using the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) (Spielberger, Gorsuch, Lushene, Vagg, & Jacobs, 1983), a self-report measure of two dimensions of anxiety: state and trait. The current study made use of the trait anxiety subscale (rather than the state subscale). Trait anxiety involves the general tendency to experience anxiety symptoms over a wide range of stressful situations (McNally, 1996). Therefore the participants’ general, overall anxiety was assessed versus their anxiety in relation to a specific stressor. This was thought to give a more comprehensive picture of the participants’ experience of anxiety. Each item is rated on a 4-point scale, indicating the degree to which an individual experiences a symptom (0–4.) A summary score for trait anxiety was created, with higher scores indicating higher levels of anxiety symptoms. The internal consistency for this measure was good (Cronbach’s α = .92 at age 22 and .91 at age 23).

Results Preliminary Analyses

Means and standard deviations for all substantive variables are presented in Table 1. 20% of participants scored above the suggested cutoff for mild depression at age 22 and 14% scored above the cutoff at age 23 (a scale score of 10, Beck & Steer, 1987). When looking at anxiety, 41% of participants scored above the cutoff for mild anxiety (a scale score of 40,

Spielberger et al., 1983) at age 22 and 35% of participants scored above the cutoff at age 23. For descriptive purposes, Table 1 also presents simple correlations among each of the study’s key variables. As expected, anxiety and depression were moderately correlated. There were moderate correlations between positive coping strategies (e.g. positive reframe and humor) as well as between negative coping strategies (e.g. venting and substance use). Gender and income were significantly related to several variables and as a result were included as covariates in all of the subsequent primary analyses.

Primary Analyses

The central goal of this study was to examine the reciprocal relationships between coping behavior and internalizing problems. The hypotheses were tested using structural cross-lagged regression models with Mplus Version 6.0 (Muthe´n & Muthe´n, 1998–2006). The advantage of this analysis is that cross-lagged effects are estimated while controlling for autoregressive and

concurrent associations. This type structural modeling highlights direct effects (e.g. coping behavior significantly predicts coping behavior one year later), cross-effects (e.g. coping behavior significantly predicts internalizing problems one year later, or vice versa), and reciprocal cross-lagged relationships if they exist (e.g. coping behavior significantly predicts internalizing problems and internalizing problems predict coping behavior one year later). This analyses followed Ferrer and McArdle’s (2003) guidelines and controlled for the demographic variables of gender and family income. In all models the following significant direct effects were observed: coping behavior at age 22 significantly predicted coping behavior at age 23, depression at age 22 predicted depression at age 23, and anxiety at age 22 predicted anxiety at age 23.

Hypothesis 1. Positive coping styles, a) positive reframing and b) humor, will show negative associations with depressive symptoms and anxiety over time.

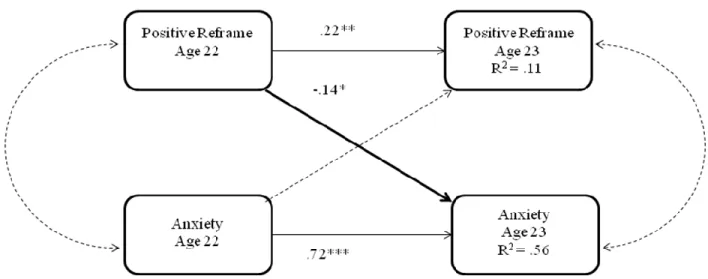

Positive reframing. Analyses investigating the associations between depression and positive reframing demonstrated that there are no significant cross lagged relationships in this model. When looking at anxiety, however, the model investigating the associations between anxiety and positive reframing produced a significant cross-effect from positive reframing at age 22 to anxiety at age 23. A reciprocal cross-lagged relationship was not observed. Results presented in Figure 1 demonstrate that using positive reframing at age 22 predicted relative decreases in anxiety one year later, after accounting for coping and self reported anxiety at age 22, but anxiety does not significantly predict the use of positive reframe.

Humor. Analyses investigating the associations between humor and internalizing problems produced results similar to those described for positive reframing. Results did not find evidence of cross-lagged relationships between depression and the use of humor as a coping strategy, but a significant relationship was found between anxiety and humor. As seen in Figure 2, a negative cross-effect was observed from humor at age 22 to anxiety at age 23, such that participants’ increased use of humor at age 22 significantly predicted relative decreases in reported anxiety at age 23.

Hypothesis 2. Negative coping styles, a) venting of emotions and b) substance abuse, will show positive reciprocal associations with depressive symptoms and anxiety over time.

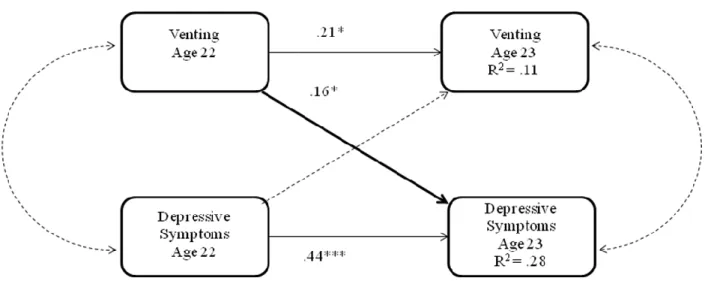

Venting of emotions. Analyses next considered the relationships between negative coping styles and depression and anxiety. Results presented in Figure 3 indicate that, as hypothesized, a positive cross-effect from venting at age 22 to depression at age 23 was significant, such that increased venting at age 22 predicted relative increases in depressive symptoms at age 23. A

reciprocal cross-lagged relationship between venting and depression does not exist. The results did not find evidence of cross lagged relationships between venting and anxiety.

Substance abuse. As hypothesized, a positive cross-effect from substance abuse at age 22 to depressive symptoms at age 23 was significant, such that using substance abuse to cope at age 22 predicted an increase in depressive symptoms one year later. Figure 4 demonstrates this pattern. The results did not find evidence of cross lagged relationships between substance use and

anxiety.

Discussion

Using cross-lagged regression analysis, this study explored the relationship between specific coping strategies and internalizing problems, specifically depression and anxiety, and whether a mutually reciprocal relationship exists between the two sets of constructs over a one- year period. Positive coping strategies (e.g. positive reframe and humor) were significant predictors of relative decreases in anxiety, and negative coping strategies (e.g. focus on venting of emotions and substance use) were significant predictors of relative increases in depressive symptoms. As hypothesized there were negative associations from positive coping strategies to reported anxiety, and there were positive associations from negative coping strategies to depressive symptoms. Results did not find evidence of a mutually reciprocal cross-lagged relationship between coping and internalizing symptoms because although coping strategies predicted internalizing symptoms, depressive symptoms and anxiety were not significant predictors of coping behavior one year later. Although coping behavior and internalizing symptoms may potentially influence each other, this pattern of findings suggests that the influence is not equal and that coping may have more weight in driving the relationship. The results highlight the potential importance of coping behavior in the development and

maintenance of internalizing problems during young adulthood. Each of these findings will be discussed in turn below.

Using positive coping strategies was found to predict relative decreases in reported anxiety but was not significantly associated with depressive symptoms. When looking at

anxiety, the current findings suggest that using positive reframe and humor as a way to cope with stress or difficult situations is a potential protective strategy against future anxiety. These

findings add to the current body of research showing negative associations between these specific coping strategies and anxiety. For example, previous research found that positive reappraisal was marginally negatively associated with anxiety (Aldao et al., 2010). Earlier research has shown similar links between humor and anxiety. One study found that highly anxious undergraduates exposed to humorous forms of an exam performed significantly better than those who were exposed to a non- humorous form of the exam (Smith, Ascough, Ettinger, & Nelson, 1971). The current study provides greater evidence for a direct relationship between humor as a coping strategy and anxiety. Our study provides inconclusive evidence when

focusing on the specific positive coping strategies and depression. Previous research shows that there are negative relationships between positive coping strategies and depression. Positive reappraisal and humor were found to predict relative decreases in depression (Aldao et al., 2010). Interestingly, while positive coping strategies significantly predict anxiety, the current study found that negative coping strategies significantly predict depressive symptoms one year later.

The current study found that specific negative coping strategies, the focus on venting of emotion and substance use, significantly predicted depressive symptoms one year later. This finding is consistent with previous research (Aldao et al., 2010) emphasizing that negative coping behavior plays an important role in the expression of depression. A vast amount of

research has been conducted investigating the link between rumination and depression. The current findings emphasize that while thinking repeatedly about negative emotions is

maladaptive for mental health speaking repeatedly about it is also maladaptive. At first glance this inference may seem to conflict with positive coping strategies that involve seeking out help and talking to someone about the problem, such as seeking instrumental support and problem solving (Aldao et al., 2010; Hong, 2007). The distinction, however, may rest in the motivation or the purpose behind the coping strategy. For example, instrumental support and problem solving are ways in which an individual can take control of their difficult situation and attempt to change it; they are active in attempting to alleviate distress. Venting, however, may be a passive form of coping. As assessed by the brief COPE, when an individual focuses on venting their emotions they are not seeking advice or help in altering their current situation they are simply allowing their negative emotions to escape. So the distinction is not whether or not an individual talks about their emotions but how they talk about them and why they talk about them. Findings suggest that venting to release emotions is not an adaptive way to cope.

The current findings are consistent with previous research and provide greater support for the negative association between substance use and depression. Little research has been

conducted investigating the direct link between substance use, as a coping strategy, and

depressive symptoms. Past research has focused on investigating avoidance as a coping strategy and how substance use is typically related to avoidance and depression (Aldao et al., 2010). The current study suggests that substance use, as a specific coping strategy, is maladaptive and is possibly a risk factor for depressive symptoms. It is possible that using substances to cope is a risk factor because it is a form of avoidance but it is also possible that the link between substance use and depression operates through a different pathway. For example, being under the influence

of drugs or alcohol may affect an individual’s cognitive abilities, making it harder to use other adaptive strategies such as problem solving and positive reframing. Therefore substance use may be a risk factor because it is hindering the use of more adaptive coping strategies.

Most importantly the current findings suggest that coping behavior and internalizing symptoms do not operate in a mutually reciprocal relationship. This study found that coping strategies significantly predicted internalizing symptoms one year later, but internalizing symptoms did not predict coping strategies one year later. Theorists may still be correct in that coping and emotion are reciprocally related and influence each other in a cyclic nature, but these results suggest that coping is more likely to be influential in the development and maintenance of depressive symptoms and anxiety.

If this pattern is replicated and extended beyond correlational designs it suggests the potential value of preventing or reducing the development of depressive symptoms and anxiety by considering these specific coping strategies as protective and risk factors. It would suggest that coping may have more weight in the relationship and may be an underlying driving factor influencing the cycle. The current study’s research design, however, is not sufficient to support causal inferences. Future research should address this limitation by employing an experimental design. Importantly, future research should also explore possible unmeasured third variables that may be driving both coping and internalizing symptoms. For example, personality may be a factor that influences coping behavior and creates a predisposition for internalizing symptoms. Future research should also investigate whether these findings generalize to other coping strategies not investigated in the current study.

Interestingly, the development of coping strategies is largely left to chance. There is often no formal setting in which we are taught how to cope. Instead, it is mostly informally

learned from parents, friends, and significant others (Szwedo, 2011). One of the few places we are taught how to cope in adaptive ways, or to realize when we are coping in maladaptive ways, is during intervention programs or other forms of mental health treatment programs, which suggests that an internalizing problem already exists. Therefore, understanding the influence of coping strategies, as well as possible third factors, on internalizing symptoms is of great

importance in the development of improved prevention and intervention techniques. The current study uses a multi-reporter method, including both self reports and the reports of the target participants’ closest peers, which serves to reduce the potential confound of the negative perceptual biases of depressed individuals (Gotlib, 1983). Although this eliminates the potential influence of a depressed individual’s negative perceptual bias, it introduces closest peer report bias when reporting about the target participants’ coping strategies. For example, some coping strategies are more internal in nature, such as self blame and denial, and may be under-reported by one’s closest peer. A second limitation is that the internal consistency for venting on the brief COPE was only marginal to adequate, which reduces the magnitude of the findings. A third limitation is that the current study used a community, normative sample that does not consist of particularly at risk for high levels of depression and anxiety. Therefore, the results of the current study cannot be generalized to young adults with clinical levels of

depression or anxiety. Future research should consider replicating the current study over a longer period of time in order to investigate how depressive symptoms and anxiety change over time. Future research should also investigate this relationship in other types of samples in order to examine how coping strategies are related to more severe cases of depression and anxiety.

References

Aldao, A., Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Schweizer, S. (2010). Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(2), 217-237. Arnett, J. J. (2004). Emerging adulthood: The winding road from the late teens through the

twenties (1st ed.). United States of America: Oxford University Press.

Beck, A. T., Rush, A. J., Shaw, B. F., & & Emery, G. (1979). Cognitive therapy of depression.

. New York: Guilford.

Beck, A. T., & Steer, R. A. (1987). BDI, beck depression inventory: Manual. New York: Psychological Corporation.

Billings, A. G., & Moos, R. H. (1984). Coping, stress, and social resources among adults with unipolar depression.

. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46(4), 877-891. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.46.4.877

Brissette, I., Scheier, M. F., & Carver, C. S. (2002). The role of optimism in social network development, coping, and psychological adjustment during a life transition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(1), 102-111. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.82.1.102 Cann, A., Holt, K., & Calhoun, L. G. (1999). The roles of humor and sense of humor in

responses to stressors. Humor: International Journal of Humor Research, 12(2), 177-193. doi:10.1515/humr.1999.12.2.177

Carver, C. S. (1997). You want to measure coping but your protocol's too long: Consider the brief COPE

. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 4(1), 92-100. doi:10.1207/s15327558ijbm0401_6

Compas, B. E., Connor-Smith, J. K., Saltzman, H., Thomsen, A. H., & Wadsworth, M. E. (2001). Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence:Problems, progress, and potential in theory and research. Psychological Bulletin, 127(1), 87-127. doi:10.1037//0033-2909.127.1.87

Deykin, E. Y., Levy, J. C., & Wells, V. (1987). Adolescent depression, alcohol and drug abuse.

American Journal of Public Health, 77(2), 178-182.

Ferrer, E., & McArdle, J. (2003). Alternative structural models for multivariate longitudinal data analysis. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 10(4), 493-524. doi:10.1207/S15328007SEM1004_1

Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1988). The relationship between coping and emotion: Implications for theory and research. Social Science & Medicine, 26(3), 309-317.

Frydenberg, E. (2008). Adolescent coping: Advances in theory, research and practice (2nd ed.). United States: Taylor & Francis US.

Gotlib, I. H. (1983). Perception and recall of interpersonal feedback: Negative bias in depression.

Cognitive Therapy & Research, 7(5), 399-412.

Grant, K. E., Compas, B. E., Stuhlmacher, A. F., Thurm, A. E., McMahon, S. D., & Halpert, J. A. (2003). Stressors and child and adolescent psychopathology:Moving from markers to mechanisms of risk. Psychological Bulletin, 129(3), 447-466.

doi:10.1037/0033-2909.129.3.447

Greenberg, P. E., Stiglin, L. E., Finkelstein, S. N., & Berndt, E. R. (1993). The economic burden of depression in 1990. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 54(11), 405-418.

Gross, J. J., & John, O. P. (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being.

. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 348-362. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348

Hassan, S., Mallozzi, L., Dhingra, N., & Haden, S. C. (2011). Victimization in young urban adults and depressed mood: Understanding the interplay of coping and gender. Violence and Victims, 26(3), 329-346.

Honey, K. L., Morgan, M., & Bennett, P. (2003). A stress-coping transactional model of low mood following childbirth. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 21(2), 129-143. Hong, R. Y. (2007). Worry and rumination: Differential associations with anxious and

depressive symptoms and coping behaviors. Behavioral Research and Therapy, 45, 277-290.

Horwitz , A. G., Hill , R. M., & King, C. A. (2010). Specific coping behaviors in relation to adolescent depression and suicidal ideation. Journal of Adolescence, 34(5), 1077-1085. John , O. P., & Gross , J. J. (2004). Healthy and unhealthy emotion regulation: Personality

processes, individual differences, and life span development. Journal of Personality, 72(6), 1301-1333. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00298.x

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal and coping. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company, Inc.

Martin, R. A., Kuiper, N. A., Olinger, L. J., & Dance, K. A. (1993). Humor, coping with stress, self-concept, and psychological well-being. Humor: International Journal of Humor Research, 6(1), 89-104. doi:10.1515/humr.1993.6.1.89

McNally, R. J. (1996). Anxiety sensitivity is distinguishable from trait anxiety. In: R. M. Rapee (Ed.), Current controversies in the anxiety disorders ( pp. 214 – 227). New York: Guilford.

Muthe´n, B. O., & Muthe´n, L. K. (1998-2006). Mplus (version 6.0) (6th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthe´n & Muthe´n.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (1991). Responses to depression and their effects on the duration of depressive episodes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100(4), 569-582. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.100.4.569

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Morrow, J., & Frederickson, B. L. (1993). Response styles and the duration of episodes of depressed mood. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 102(1), 20-28. Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Parker, L. E., & Larson, J. (1994). Ruminative coping with depressed

mood following loss. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(1), 92-104. Overholser, J. C. (1992). Sense of humor when coping with life stress. Personality and

Individual Differences, 13(7), 799-804.

Plumb, J. C., Orsillob, S. M., & Luterekc, J. A. (2004). A preliminary test of the role of experiential avoidance in post-event functioning. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 35(3), 245-257.

Smith, R. E., Ascough, J. C., Ettinger, R. F., & Nelson, D. A. (1971). Humor, anxiety, and task performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 19(2), 243-246.

doi:10.1037/h0031305

Spielberger, C. D., Gorsuch, R. L., Lushene, R., Vagg, P. R., & Jacobs, G. A. (1983). Manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press, Inc.

Steer, R. A., & Beck, A. T. (Eds.). (1997). Evaluating stress: A book of resources. evaluating stress: A book of resources. Lanham, MD, US: Scarecrow Education.

Stewart, W. F., Ricci, J. A., Chee, E., Hahn, S. R., & Morganstein, D. (2003). Cost of lost productive work time among US workers with depression. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 289(23), 3135-3144.

Swendsena, J. D., & Merikangas, K. R. (2000). The comorbidity of depression and substance use disorders. Clinical Psychology Review, 20(2), 173-189.

Szwedo, D. E. (2011). The development of emotion regulation strategies during adolescence and their associations with youths’ psychological adjustment in early adulthood

(Unpublished Manuscript), University of Virginia.

Teasdale, J. D. (1983). Negative thinking in depression: Cause, effect, or reciprocal relationship?

Advanced in Behavior Research and Therapy, 5(1), 3-25.

The National Institute of Mental Health. (2012). Generalized anxiety disorder among adults.

Retrieved 04/14, 2012, from http://www.nimh.nih.gov/statistics/1GAD_ADULT.shtml The National Institute of Mental Health. (2012). Mood disorder among adults. Retrieved 4/14,

2012, from http://www.nimh.nih.gov/statistics/1ANYMOODDIS_ADULT.shtml Wills, T. A., Sandy, J. M., Shinar, O., & Yaeger, A. (1999). Contributions of positive and

negative affect to adolescent substance use:Test of a bidimensional model in a longitudinal study. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 13(4), 327-338. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.13.4.327 Windle, M. (2000). Parental, sibling, and peer influences on adolescent substance use and

alcohol problems. Applied Developmental Science, 4(2), 98-110.

Wittchen, H. (2002). Generalized anxiety disorder: Prevalence, burden and cost to society.

Table 1

Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations among Primary Variables

Variable 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 M SD --- --- $43,500 $22,580 5.52 6.45 37.67 10.01 3.85 1.71 3.77 2.00 2.36 1.51 1.33 1.62 4.97 6.37 36.51 9.45 4.01 1.67 3.35 1.86 2.22 1.49 1.34 1.60 1. Adolescent Gender (1= Male; 2= Female) --- 2. Family Income (MR) -.11 --- 3. Depression (22) (SR) .03 .04 --- 4. Anxiety (22) (SR) .01 -.02 .65*** --- 5. Positive Reframe (22) (PR) -.03 -.19* -.03 -.06 --- 6. Humor (22) (PR) -.19* .16 -.01 -.08 .34*** --- 7. Venting (22) (PR) .07 .14 .11 .13 -.03 .19* --- 8. Substance Use (22) (PR) -.22** .13 .11 .08 -.07 .23** .46*** --- 9. Depression (23) (SR) .03 -.11 .42*** .41*** -.07 -.13 .24* .18* --- 10. Anxiety (23)(SR) -.02 .02 .48*** .74*** -.19* -.19* .22* .13 .56*** --- 11. Positive Reframe (23)(PR) -.09 -.18* -.06 -.13 .26** -.05 -.12 -.07 .08 -.11 --- 12. Humor (23) (PR) -.20* -.05 -.10 -.06 .17 .22* -.08 .17 .04 -.09 .35* ** --- 13. Venting (23) (PR) .11 .11 .13 .15 -.20* .03 .24** .16 .19* .13 -.38 * ** -.19* --- 14. Substance Use (23) (PR) -.20* .15 .12 .03 -.14 .14 .16 .37*** .07 .05 -.20* .03 .16 --- Note. SR = self report, MR = mother report, PR= peer report

Figure 1. Path diagram of cross-lagged regression model of positive reframe and anxiety. Dotted lines indicate non significant pathways and solid lines indicate significant pathways. Gender and family income are covaried in all analyses.

Figure 2. Path diagram of cross-lagged regression model of humor and anxiety. Dotted lines indicate non significant pathways and solid lines indicate significant pathways. Gender and family income are covaried in all analyses.

Figure 3. Path diagram of cross-lagged regression model of venting and depressive symptoms. Dotted lines indicate non significant pathways and solid lines indicate significant pathways. Gender and family income are covaried in all analyses.

Figure 4. Path diagram of cross-lagged regression model of substance use and depressive symptoms. Dotted lines indicate non significant pathways and solid lines indicate significant pathways. Gender and family income are covaried in all analyses. Note: *p < .05; ** p <.01; *** p<.001

Appendix A

Beck Depression Inventory- BDI

For each number, check the box that best describes how you have been feeling in the past week, including today. If more than one statement within a group seems to apply equally well, check each box that applies.

1 I do not feel sad.

I feel sad.

I am sad all the time and I can’t snap out of it. I am so sad or unhappy that I can’t stand it.

2 I am not particularly discouraged about the future.

I feel discouraged about the future. I feel I have nothing to look forward to.

I feel that the future is hopeless and that things cannot improve.

3 I do not feel like a failure.

I feel I have failed more than the average person.

As I look back on my life, all I can see is a lot of failures. I feel I am a complete failure as a person.

4 I get as much satisfaction out of things as I used to.

I don’t enjoy things the ways I used to.

I don’t get real satisfaction out of anything anymore. I am dissatisfied or bored with everything.

I feel guilty a good part of the time. I feel quite guilty most of the time. I feel guilty all of the time.

6 I don’t feel I am being punished.

I feel I may be punished. I expect to be punished. I feel I am being punished.

7 I don’t feel disappointed in myself.

I am disappointed in myself. I am disgusted with myself. I hate myself.

8 I don’t feel I am any worse than anybody else.

I am critical of myself for my weaknesses or mistakes. I blame myself all the time for my faults.

I blame myself for everything bad that happens.

9 I don’t have any thoughts of killing myself.

I have thoughts of killing myself, but I would not carry them out. I would like to kill myself.

10 I don’t cry any more than usual. I cry more now than I used to. I cry all the time now.

I used to be able to cry, but now I can’t cry even though I want to.

11 I am no more irritated now than I ever am.

I get annoyed or irritated more easily than I used to. I feel irritated all the time now.

I don’t get irritated at all by the things that used to irritate me.

12 I have not lost interest in other people.

I am less interested in other people than I used to be. I have lost most of my interest in other people. I have lost all of my interest in other people.

13 I make decisions about as well as I ever could.

I put off making decisions more than I used to.

I have greater difficulty in making decision than before. I can’t make decisions at all anymore.

14 I don’t feel I look any worse than I used to.

I am worried that I am looking old or unattractive.

I feel that there are permanent changes in my appearance that make me look unattractive.

I believe that I look ugly.

It takes an extra effort to get started at doing something. I have to push myself very hard to do anything.

I can’t do any work at all.

16 I can sleep as well as usual.

I don’t sleep as well as I used to.

I wake up 1-2 hours earlier than usual and find it hard to get back to sleep. I wake up several hours earlier than I used to and cannot get back to sleep.

17 I don’t get more tired than usual.

I get tired more easily than I used to. I get tired from doing almost anything. I am too tired to do anything.

18 My appetite is no worse than usual.

My appetite is not as good as it used to be. My appetite is much worse now.

19a I haven’t lost much weight, if any, lately. I have lost more than 5 pounds lately, I have lost more than 10 pounds lately. I have lost more than 15 pounds lately.

19b I am purposely trying to lose weight by eating less. YES

NO

20 I am no more worried about my health than usual.

I am worried about physical problems such as aches and pains, or upset stomach, or constipation.

I am very worried about physical problems and it’s hard to think of much else. I am so worried about physical problems that I cannot think about anything else.

21 I have not noticed any recent change in my interest in sex.

I am less interested in sex than I used to be. I am much less interested in sex now. I have lost interest in sex completely.

Appendix B

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory- STAI

Below are a number of statements which people have used to describe themselves. Read each statement, and then check the appropriate box to indicate how you GENERALLY feel. There are no right or wrong answers. Do not spend too much time on any one.

Almost Never Sometimes Often Almost Always 1. I feel pleasant.

□

□

□

□

2. I tire quickly.□

□

□

□

3. I feel like crying.

□

□

□

□

4. I wish I could be as happy as others seem.

□

□

□

□

5. I am losing out on things because I can’t make up my mind soon enough.

□

□

□

□

6. I feel rested.

□

□

□

□

7. I am “cool, calm, and collected”.

□

□

□

□

8. I feel difficulties are piling up so that I cannot overcome them.

□

□

□

□

9. I worry too much over something that doesn’t really matter.

10. I am happy.

□

□

□

□

11. I am inclined to take things hard.

□

□

□

□

12. I lack self-confidence.

□

□

□

□

13. I feel secure.

□

□

□

□

14. I try to avoid facing a crisis or difficulty.

□

□

□

□

15. I feel blue.

□

□

□

□

16. I am content.

□

□

□

□

17. Some unimportant thought runs through my mind and bothers me.

□

□

□

□

18. I take disappointments so strongly that I can’t put them out of my mind.

□

□

□

□

19. I am a steady person.

□

□

□

□

20. I get in a state of tension or turmoil as I think over my recent concerns and interests.

Appendix C Brief C.O.P.E.

We are interested in how people respond when they confront difficult or stressful events in their lives. There are lots of ways to try to deal with stress. This questionnaire asks you to indicate what your friend generally does and feels, when they experience stressful events. Obviously, different events bring out somewhat different responses, but think about what they usually do when under a lot of stress.

Then respond to each of the following items using the response choices Listed below.

Please try to respond to each item separately in your mind from each other item. Choose your answers thoughtfully, and make your answers as true for your friend as you can. Please answer every item. There are no “right” or “wrong” answers, so choose the most accurate answer for

your friend, not what you think most people would say or do.

Indicate what your friend usually does when they experience a stressfull event.

1 = He/she usually doesn’t do this at all 2 = He/she usually does this a little bit

3 = He/she usually does this a medium amount 4 = He/she usually does this a lot

1. He/she usually concentrates their efforts on doing something about the situation they are in. 1 2 3 4

2. He/she usually takes action to try to make the situation better………...1 2 3 4

3. He/she usually tries to come up with a strategy about what to do...1 2 3 4

4. He/she usually thinks hard about what steps to take...1 2 3 4

5. He/she usually tries to see it in a different light, to make it seem more positive...1 2 3 4

6. He/she usually looks for something good in what is happening...1 2 3 4

7. He/she usually accepts the reality of the fact that it has happened...1 2 3 4

8. He/she usually learns to live with it...1 2 3 4

9. He/she usually makes jokes about it ...1 2 3 4

10. He/she usually makes fun of the situation...1 2 3 4

11. He/she usually tries to find comfort in their religious or spiritual beliefs...1 2 3 4

12. He/she usually prays or meditates...1 2 3 4

13. He/she usually gets emotional support from others...1 2 3 4

15. He/she usually tries to get advice or help from other people about what to do………..1 2 3 4

16. He/she usually gets help and advice from other people...1 2 3 4

17. He/she usually turns to work or other activities to take their mind off things...1 2 3 4

18. He/she usually do something to think about it less, such as going to movies, watching TC, reading,

Daydreaming, sleeping or shopping)...1 2 3 4

19. He/she usually says that “this isn’t real”...1 2 3 4

20. He/she usually refuses to believe that it has happened...1 2 3 4

21. He/she usually says things to let their emotions escape...1 2 3 4

22. He/she usually expresses their negative feelings ...1 2 3 4

23. He/she usually uses alcohol or other drugs to makes themselves feel better...1 2 3 4

24. He/she usually uses alcohol or other drugs to help them get through it...1 2 3 4

25. He/she usually gives up trying to deal with it ...1 2 3 4

26. He/she usually gives up the attempt of coping ...1 2 3 4