PHIOS CORPORATION WHITE PAPER

New Tools for

Managing Business Processes

March 1999

Phios

One Broadway, Suite 600Phios CorporationCambridge, MA 02142 617-621-7171 www.phios.com

New Tools for Managing Business Processes

This Phios white paper gives an overview of the problems of business process management and how the Phios Process Repository tools can help address these problems.

The problem: Managing business processes

In the last decade or two, most companies’ use of data has been transformed through initiatives like decision support systems, information resource management, data repositories, enterprise resource planning systems, and— most recently— knowledge management. It is now hard to find a large, successful company that has not made significant progress in computerizing and integrating their data across the company. Many companies, for example, now have extensive customer histories available on-line to the service representatives who help customers on the phone. Some leading companies are deriving significant additional benefits from “mining” their corporate data for detailed insights into which customers and which products are most profitable.

Compared to their use of data, however, most companies today are still very primitive in the ways they manage their processes. Business processes are inconsistent across applications, locations, functions, and divisions. Few people understand how their work relates to the overall processes in which they participate. Even though process maps, task documentation, and job aids exist in isolated cases, most knowledge about how things are— or should be— done is stored in incompatible and disconnected ways. Usually this knowledge is not even written down at all, but exists only in people’s heads.

Why is this a problem?

This informal and haphazard management of processes has a number of undesirable consequences:

• Customers receive inconsistent and often inadequate service from different parts of the company, sometimes compromising the entire corporate brand image.

• Managers continually struggle to manage the “horizontal” interactions between people in different parts of the company who don’t understand how their work fits into an overall corporate process.

• Best practices and other ideas for improving how things are done are discovered and shared haphazardly, and often repeatedly re-invented in different parts of the company.

• In general, the problems of continually adapting to a rapidly changing world— new competitors, new products, new technologies, and new business models— are getting more and more important, but the tools most companies have for dealing with them are increasingly inadequate.

Needed: Better process management

In the same way that information technology has already helped most companies manage their data more effectively, we believe that one of the next big opportunities for using information technology is to help companies manage their processes more effectively. We define process management as:

Systematically understanding, tracking, and improving the business processes that matter.

In fact, we believe that many successful companies in the 21st century will devote as much attention to managing their processes as they currently devote to managing their

products.

More and more companies today are already beginning to make the changes in culture and managerial mindset needed to manage in this new way. For instance, the very process of implementing an enterprise resource planning (ERP) system often requires a company to think much more explicitly about their business processes than they ever have before.

As more companies move in this direction, they are beginning to realize that— in order to manage their processes more effectively— they need more systematic ways of managing their process knowledge: What things need to be done? Who is responsible for them? What works well and what doesn’t? How do other companies do these things? What are innovative new ways of doing these things?

It is, of course, possible to manage this kind of knowledge in the ad hoc, haphazard ways most companies do today. But to do this well requires specially designed electronic knowledge repositories.

The Phios approach: Process repositories

The Phios mission is to be the leading supplier of these electronic knowledge repositories that help companies better manage their business processes. These “process repositories” include both software tools and knowledge content to help companies explicitly define and manage their own processes and find state-of-the-art knowledge about how other companies do similar things.

We define process repositories as:

Consistent, easy-to-use collections of process knowledge, used for multiple purposes.

For example, in addition to just storing process maps, these repositories can be used to organize process documentation, “best practice” libraries, measurement and benchmarking data, software configuration and change data, linkages to relevant web sites, and many other kinds of knowledge. In some cases, these additional kinds of process knowledge will be actually stored in the process repository. In other cases, the repository will only store links to information that is physically stored somewhere else (e.g., on separate web pages or in a document repository)

We view process repositories as a critical component of a company’s knowledge management strategy. Unlike most other approaches to knowledge management, process repositories focus on “know how” rather than “know what”. However, these repositories can also be used to organize many kinds of “know what” by categorizing them according to the business activities for which the knowledge is relevant.

History of the Phios approach: The MIT Process Handbook Project

The Phios Process Repository approach is based on over 7 years of research at the MIT Sloan School of Management, involving over 30 person-years of effort. Drawing on research in computer science, organization theory, and coordination science, these MIT researchers developed a pioneering process repository, called the “Process Handbook.” This repository includes knowledge about over 5000 business processes and activities. It also includes a variety of software tools to edit and view this knowledge base.1

In order to commercialize the results of this research, MIT has licensed to Phios, on an exclusive basis, all the intellectual property resulting from the project. This intellectual property includes the software, the repository contents, and patents covering the basic approach to process representation. In addition, the researchers who led this project at MIT are co-founders of Phios.

The Process Compass

One of the most important features of the Phios Process Repository approach is its use of the “Process Compass” to help people organize--and navigate through--richly interconnected networks of related processes and activities. As shown in Figure 1, the Process Compass represents the four different directions you can go from any activity (or process) in the repository.

The vertical dimension of the compass represents the conventional way of analyzing processes: according to their different parts. You can go down to the different parts of the activity (its “subactivities”) or up to the larger activities of which this one is a part (its “uses”).

Figure 1. The “Process Compass” shows two dimensions for analyzing business processes. The vertical dimension distinguishes different parts of a process; the horizontal dimension distinguishes different types of a process.

Almost all process-mapping techniques use only this vertical dimension. The Phios Process Repository adds a novel second dimension, the horizontal one. This dimension deals, not with the parts of a process, but with the types of a process. You can go right

from an activity to its different types (or “specializations”), and you can go left from an activity to the different activities of which this one is a type (its “generalizations”).

In addition to providing an intuitive way of organizing large collections of processes, this approach also simplifies the problems of maintaining them using a concept called “inheritance” from computer science. More details of this approach are included in the appendix of this paper.

Phios products

Software products

Phios is developing three primary software products:

• Process editor – This tool lets “power users” create and maintain the knowledge in a process repository. This knowledge can include process maps (such as flowcharts), text and graphics about the processes, and links to Web sites. The tool uses software loaded onto a user’s PC to edit either a local or shared process repository.

• Process repository server – This software allows users with standard Web browsers (such as Internet Explorer or Netscape Navigator) to view the contents of a process repository (such as a repository containing their own company’s processes). This installation includes database and Web server software. The software is installed on a server computer (usually on a company’s own Intranet).

Uses

Specializations

Subactivities Generalizations

• Stand-alone process viewer – This tool lets users view the contents of a process repository on their own PC without being connected to a network. It can be used, for example, to view processes on an airplane or in a meeting where connection to the Internet is not convenient.

Content products

Phios is also developing the following content-based products:

• Business process knowledge – The Phios Process Repository currently includes over 5000 process and activities. This knowledge base includes (a) a detailed “skeleton” for representing knowledge about all business processes, (b) a number of business process reference models, and (c) case examples, best practices, and links to other kinds of business knowledge from a variety of sources.

Some companies may use the Phios software tools to represent only their own business processes, but we expect that many will want to use some of this other knowledge provided by Phios as a starting point for organizing or supplementing their internally generated process knowledge.

• Public web site – For companies that do not use the Phios software tools, the Phios business process knowledge will also be available via a public web site. Some of this content will be available for free; other parts will require subscriptions or other forms of payment.

Product architecture

As shown in the figure below, the Phios software includes three primary levels: (a) a relational database (such as Microsoft Access, SQL Server, Oracle, etc.), (b) a “process repository engine” layer that adds the “object-oriented” features described in the appendix on top of a standard relational database, and (c) a variety of different user interfaces and links to other tools. The Process Handbook Applications Program Interface (PH API) between the top two levels simplifies the development of multiple alternatives at these two levels.

The Phios content is available as information stored in a company’s local process repository or via the public Phios web site.

Figure 2. The Phios product architecture

A typical customer configuration

While different customers will have different needs, we expect a typical product configuration for a company using the Phios Process Repository tools to include:

(1) One or more process repository servers to make the company’s internal process knowledge available over the company’s Intranet to people involved in performing and managing the processes in the repository.

(2) A number of process editor tools to be used by process analysts, process managers, and others involved in defining and maintaining the process knowledge base for the company.

(3) If some users need to access the repository when it is difficult to connect to the Internet (e.g., in meetings or on airplanes), stand-alone process viewers for these users. TOOL INTERFACES USER INTERFACE CLIENTS PROCESS REPOSITORY Database System Process repository server Stand-alone process viewer Process editor Process Model Translators Other add-on tools

Process Handbook API Process Repository Engine

Process Content

Web browsers

Other software tools Workflow systems

Enterprise software packages Other process modeling tools

(4) A corporate license to use the Phios business process knowledge in the company’s internal repository

(5) A corporate subscription to access the Phios repository on the public web site.

Using the Phios Process Repository: Company examples

Dow Corning Corporation: Implementing SAP and supply chain management

Dow Corning Corporation is a leading producer of silicone materials and polycrystalline silicon. The company has annual revenues of approximately $2.5 billion, with greater than 50% of it's sales base being outside the U.S. They are nearing completion of the installation of SAP's integrated software suites (an Enterprise Resource Planning System) worldwide. This is enabling the identification of a number of business process improvements. Dow Corning is taking advantage of these opportunities through rationalizing and standardizing many of their global business processes. They feel it is particularly important that these process changes be documented to provide a basis for continued process innovation from future learning.

Before working with Phios, they had developed initial models of the business processes they expect to use with SAP. These models are quite detailed, including color coding to indicate which activities in the process are performed using SAP functions, which are performed manually, and which are performed with legacy software systems.

Dow Corning represented these models using the Visio business diagramming tool. As such, the models were essentially isolated drawings: Whenever an arrow from one diagram pointed to another diagram, or whenever the same activity was used in multiple diagrams, consistency between the different diagrams had to be maintained manually. In their discussions with Phios, Dow Corning realized that what they really wanted was an underlying process repository that would maintain a single consistent representation of all their business processes and would allow different subsets of the processes to be viewed in different ways at different times.

Working with Dow Corning, Phios developed software to automatically import the existing Dow Corning Visio diagrams into the Phios Process Repository. Phios also developed software to edit the contents of the repository using Visio as a “live” user interface. This Visio-based user interface is now the primary user interface in the Phios

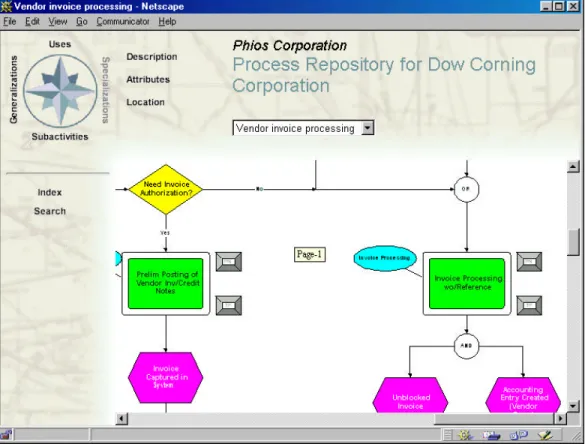

Dow Corning now has over 30 SAP-related business processes represented in the Phios Process Repository, each including a number of activities and events (see example in Figure 3). They are preparing to use the Phios Process Repository to make these process models and related documentation available on their corporate Intranet to the people who manage and carry out these processes.

Figure 3. A sample view of the Dow Corning business processes over the Web.

After initially representing their SAP-related processes in the Phios Process Repository, Dow Corning also became interested in using the Phios repository to analyze their processes from an integrated supply chain perspective. The supply chain model they wanted to use was the Supply Chain Operations Reference (SCOR) model developed by the Supply Chain Council (described in more detail in the next section). In doing this

supply chain modeling, however, Dow Corning wanted to take as much advantage as possible of the work they had already done on representing SAP processes.

The Phios repository already included the SCOR model, and working with Phios, Dow Corning created a new specialization of the SCOR model that was specific to Dow Corning. Then, they modified this specialized model to include linkages to the detailed Dow Corning SAP-related processes used to do the various supply chain activities. In this way, Dow Corning was able to re-use the same detailed models in multiple ways for different purposes.

Now, in addition to their SAP and supply chain modeling, Dow Corning is also investigating using the Phios Process Repository for other purposes such as ISO 9000 modeling and compliance with regulated processes such as those for handling hazardous materials.

The Supply Chain Council: Managing and sharing a process reference model

The Supply Chain Council is a trade association of over 400 companies interested in supply chain management (see www.supply-chain.org). The founding members of the group include AMR Research, Bayer Corp., Compaq Computer, Pittiglio Rabin Todd & McGrath (PRTM), Procter & Gamble, Lockheed Martin, Nortel, Rockwell Semiconductor, and Texas Instruments. Formed in 1997, the Council developed the Supply Chain Operations Reference (SCOR) model, which has quickly become the de facto standard model for cross-industry supply chain modeling. The SCOR model contains standard process definitions, standard terminology, standard metrics, supply-chain best practices, and references to enabling information technology.

The Supply Chain Council has recently chosen the Phios Process Repository as the tool with which they will manage and extend the SCOR model. The current version of the SCOR model is now incorporated in a Phios repository, and the Phios tool is already providing a simple, easy-to-use way for SCC members to view the model using the World Wide Web. For example, Figure 4 shows part of the SCOR model as viewed over the Web.

In the future, by providing a single, integrated, repository, the Phios tool is also expected to help the Council much more easily manage and maintain consistency among different parts of the model, successive releases of the model, and multiple versions of the model.

Figure 4. A sample view of the Supply Chain Council’s SCOR model.

Firm A: Getting innovative ideas about hiring

Firm A is a large, well-known services company, which doesn’t want to be explicitly identified. As part of the MIT research project on which the Phios products are based, MIT worked with AT Kearney (one of the MIT research sponsors) and Firm A (one of AT Kearney’s clients) to generate highly innovative new ideas about how Firm A could improve its hiring process.

This project was motivated by the fact that Firm A was experiencing increasing problems with hiring. They were growing rapidly in a tightening labor market, and they had a culture of independent, competitive business units. Together, these factors led to increases in the time and cost to hire people and to increasingly frequent instances of business units “hoarding” candidates or bidding against each other for the same candidate. Before this project began, Firm A had already invested a great deal of time and energy into “as is” process analysis using techniques such as flowcharting.

The project team’s first step was simply to see how the hiring process was represented in the process repository. Several of the steps in the activity called “Hire human resources” were similar to those already identified by the “as is” analysis (e.g., identify need, determine source, select, and make offer). One immediate insight, however, resulted

from the fact that the repository included a step of “pay employee” which had not been included in the “as is” analysis. Even though they hadn’t previously thought of it in this way, the team members from Firm A found it surprising and useful to realize that the employee receiving a first paycheck is, in a sense, the logical culmination of the hiring process. Receiving a (correct) paycheck, for instance, confirms that the hiring information has been entered correctly in the relevant administrative systems.

To generate further ideas, the team looked at the specializations of the overall hiring process and then at the specializations of each of its subactivities. (In other words, they looked to the right on the Process Compass.) In doing so, they came across dozens of examples of innovative practices other companies used in hiring (see Figure 5). For instance, one interesting example involved how Marriott uses an automated telephone system to screen job applicants. The system asks job candidates a series of questions about their qualifications and salary requirements over the telephone, and candidates answer these questions using their touch tone telephone keys. Then, at the end of the call, the candidates are immediately told if they're qualified for the position and invited to schedule an interview through the system's automated scheduling feature. Although this approach would be very inappropriate in many situations, the team members from Firm A thought this approach might be very useful for some of their entry-level positions.

After looking at a number of these examples of innovative hiring practices, the team’s next step was to look further afield in the repository for distant analogies (or “cousins”) of the hiring process. That is, they looked first at generalizations (“ancestors”) of the hiring process and then at other specializations (“descendants”) of these generalizations. (In terms of the Process Compass, they moved left and then right again.)

For example, “hiring” is classified in the repository as a specialization of “buying”, so a handbook user who looks at the generalizations of “hiring” will see “buying”. In retrospect, this connection may seem obvious (hiring is a form of buying someone’s time), but this analogy had not been obvious to the project team, and it was a very stimulating source of insights. For example, the team found a description of General Electric’s Internet-based purchasing system through which buyers can find and compare suppliers, and this example stimulated ideas about how Firm A might be able to use a similar system to identify job candidates using the Internet.

As a result of this project, Firm A identified dozens of new ideas for how they could do hiring. They also felt that, in addition to simply being a source of new ideas, the process repository could be useful as a framework for organizing and keeping track of all the ideas generated in the course of the team’s discussions.

Figure 5. A sample of innovative hiring practices viewed by Firm A.

Conclusion

Just as most companies today are far more sophisticated about systematically managing information than they were a decade or two ago, we believe that more and more companies are now beginning to recognize the benefits of systematically managing their processes as well. To realize its ultimate potential, this kind of systematic process management will require managerial and cultural changes similar to those that have occurred with information management. It will also require specially designed electronic repositories to help define, track, and share knowledge about business processes.

1

A detailed description of the results of the MIT research project is available in the following article: Malone, T. W., Crowston, K. G., Lee, J., Pentland, B., Dellarocas, C.,

Appendix:

Specialization of Processes

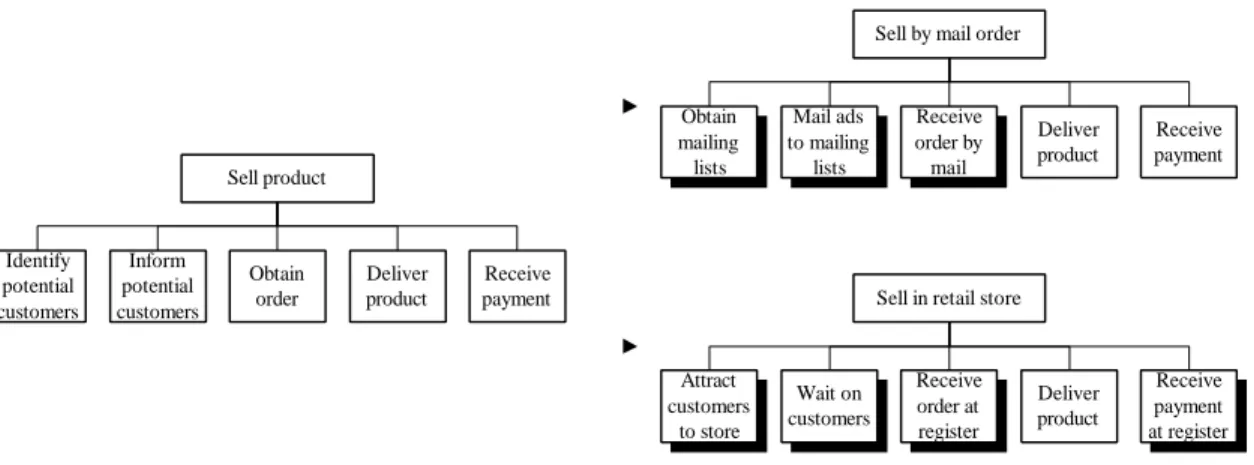

In addition to providing a powerful, but intuitive, way of organizing large collections of processes, this approach also lets us take advantage of the concept of “inheritance” from object-oriented programming in computer science. This means that each activity automatically “inherits” the subactivities and other properties of its generalization, except where the specialized activity explicitly adds or changes a property. For example, Figure 2 shows how the generic activity called “Sell product” is differentiated into types (or specializations) like “Sell by mail order” and “Sell in retail store”. Each of these specializations inherits some of the subactivities of “Sell product” and changes others. For instance, in “Sell by mail order”, the subactivities of “delivering a product” and “receiving payment” are inherited without modification, but “Identifying potential customers” is replaced by the more specialized activity of "Obtaining mailing lists."

Figure 6. Sample views of three different sales processes. "Sell by mail order" and "Sell in retail store", are specializations of the generic sales process "Sell product". The subactivities shown with shadows are changed relative to the corresponding activities in the generic sales process.

Using this approach, any number of activities can be arranged in a richly interconnected two-dimensional network. Each of the subactivities shown in Figure 6, for instance, can be further broken down into more detailed subactivities (e.g., "Type mailing list name into computer using SAP function #17A") or more specialized types (e.g., "Obtain mailing list from broker”, “Obtain mailing list from trade association”, “Obtain mailing list from current customer list”, etc.) to any level desired.

This approach can be used, for example, to create different types of the same generic process for: (a) different industries, (b) different companies, (c) different divisions of a

Identify potential customers Inform potential customers Sell product Deliver product Receive payment Obtain order Obtain mailing lists Mail ads to mailing lists

Sell by mail order

Deliver product Receive payment Receive order by mail Attract customers to store Wait on customers

Sell in retail store

Deliver product Receive payment at register Receive order at register

company, (d) different geographical regions of a company, (e) different software implementations (e.g., “purchase using SAP” vs. “purchase using Baan”), and many other dimensions.

This approach significantly simplifies the problem of maintaining large repositories because it explicitly represents the commonalties and relationships among different variations of the same generic process. Changes made at a high level, for instance, to the corporate standard process for “selling at Company X” are then automatically inherited to all the different specializations of this process (e.g., for different products or divisions) except where the specializations have already made other changes of their own.

Comparison with object-oriented programming

To readers familiar with conventional object-oriented programming techniques, it is worth commenting on the difference between this approach and conventional object-oriented programming. Traditional object-object-oriented programming inherits down a hierarchy of increasingly specialized objects, which may have associated with them actions (or “methods”). Our approach, by contrast, inherits down a hierarchy of increasingly specialized actions (or “processes”) which may have associated with them objects. Loosely speaking, then, traditional object-oriented programming involves inheriting down a hierarchy of nouns; our approach involves inheriting down a hierarchy of verbs.

There is, of course, nothing contradictory between these two approaches. We believe that both are often useful in the same system. In a sense, this “process oriented” inheritance can be considered the “missing half” of object-oriented programming. The process-oriented approach appears to be particularly appropriate for the analysis and design of business processes.

Bundles

We have also found it useful to combine specializations into what we call “bundles” of related alternatives. For instance, Figure 7 shows part of the specialization hierarchy for sales processes. In this example, one bundle of specializations for “Sell something” is related to how the sale is made: direct mail, retail storefront, or direct sales force. Another bundle of specializations has to do with what is being sold: beer, automotive components, financial services, etc.

Figure 7. Summary display showing specializations of the activity "Sell something". Items in brackets (such as "[Sell how?]") are "bundles" which group together sets of related specializations.

Trade-off tables

Comparing alternative specializations is usually meaningful only within a bundle of related alternatives. For example, comparing “retail store front sales” to “direct mail sales” is sensible, but comparing “retail store front sales” to “selling automotive components” is not. Where there are related alternative specializations in a bundle, our repository can include comparisons of the alternatives on multiple dimensions, thus making explicit the tradeoff between these dimensions.

For example, Figure 8 shows a “tradeoff matrix” that compares alternatives in terms of their ratings on various criteria; different specializations are the rows and different characteristics are the columns. For very generic processes such as those shown here, the cells usually contain rough qualitative comparisons (such as “High”, “Medium”, and “Low”); for specific process examples, they may contain detailed quantitative performance metrics for time, cost, job satisfaction, or other factors. In some cases, these comparisons may be the result of systematic studies; in others, they may be simply rough guesses by knowledgeable experts and, of course, in some cases, there may not be enough information to include any comparisons at all.

Figure 8. A tradeoff matrix showing typical advantages and disadvantages of different specializations for the generic sales process. (Note that the values in this version of the matrix are not intended to be definitive, merely suggestive.)

Copyright © 1999 Phios Corporation. All rights reserved.