Leiden University

Faculty of Governance and Public Affairs

MSc in Public Administration

9 June 2016

The Impact of Chinese Loans on Good Governance

in Latin America

Master Thesis

Table of Contents

1. Introduction……….2

2. Theoretical Framework………...8

2.1 Literature Review……….8

2.2 Conceptual Framework………20

2.2.1 Key Concepts………...20

2.2.2 Main Hypothesis and Competing Hypotheses………28

3. Research Design……….…31

3.1 Operalisation of Concepts………...31

3.1.1 Dependent Variables……….31

3.1.2 Independent Variable………35

3.1.3 Extraneous Variable……….35

3.2 Research Approach……….36

3.3 Case Selection……….39

3.4 Research Method……….47

3.5 Limitations………..50

4. Data Analysis and Results………52

4.1 Data Collection and Analysis……….52

4.1.1 Dependent Variable 1: Voice………...52

4.1.2 Dependent Variable 2: Performance………...56

4.1.3 Dependent Variable 3: Accountability……….63

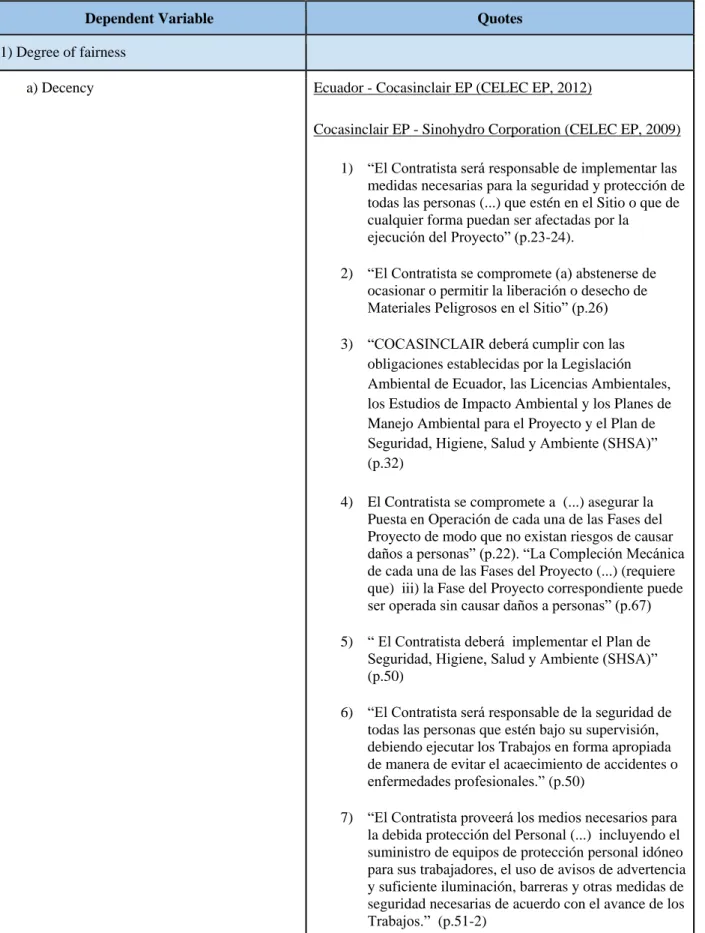

4.1.4 Dependent Variable 4: Fairness………..72

4.1.5 Extraneous Variable: National Regulations………...77

4.2 Results………...82

5. Conclusion………....…………...85

1. Introduction

In 2014 China surpassed the United States as the world’s largest economy in terms of purchasing power parity according to the IMF (Bird 2014, pars.1,3). Its economic success is particularly remarkable considering that less than four decades earlier it was still one of the world’s poorest countries (Zhu 2012, p.103). From 1979 to 2014, China experienced an impressive GDP growth average of 10%, which is only now slowing down to around 6-7% (Morrison 2015, p.1; The Economist 2015a, par.1).

The origins of China’s economic ascent can be traced back to the program of economic reforms introduced by Deng Xiaoping in 1978. Following the Cultural Revolution, the Chinese government adopted a policy of Gaige Kaifang or ‘reform and opening up’, intended to strengthen its legitimacy through strong economic growth and higher living standards (Zhu 2012, p.110). To begin with, a new system of incentives for agricultural production was introduced, enabling farmers to sell part of their produce at market prices (McMillan et al. 1989, p.785). Then, various special economic zones were established along the coast, intended to promote competition, foster technological innovation and attract foreign investment through a more liberal regulatory environment (Stoltenberg 1984, p.639). Gradually, a variety of reforms was introduced over the years, which effectively relaxed the central government’s control over economic policy-making: state-owned enterprises were given over to local governments and permitted to operate at market prices, individuals were allowed to start their own businesses and price controls were abolished in stages. Additionally, trade barriers and tariffs were gradually removed, as China shifted its economy towards an export-led growth strategy (Morrison 2015, p.4).

efficiency following the economic reforms, which "boosted output and increased resources for additional investment in the economy" (Morrison 2015, p.7).

Together, these two factors contributed to China’s vertiginous economic rise, the effects of which have been felt not only domestically, where over 800 million people have been raised out of poverty, but also globally (World Bank 2016, par.1). China’s international trade has expanded significantly, in the form of high exports of low-cost products, which have increased global manufacturing competition, and a strong demand for raw materials, which have maintained global commodity prices high (Plumer 2014, par.2; The Economist 2015b, par.1). Furthermore, it is now an important source of investments and loans for rich and poor countries alike (Friedman 2011, par.9). In short, China has become a major economic power and a “key driver of the world economy” (Associated Press 2016, par.12).

The rise of China has had a particular impact on the developing world, both indirectly, through the emergence of an alternative development model, and directly, in the form of its growing economic influence over these countries resulting from an increase in trade relations and in the provision of aid, loans and investment. The present research will focus on China’s impact in one region in particular: Latin America.

China’s economic ties with the region consist mainly of trade, investment and loans. Between 2000 and 2013, Latin America’s trade with China grew at an average of 27 percent per year, rising from $12 billion to $289 billion (Elson 2014, p.44; Pineo 2015, par.4). This year China is expected to become the region’s most important trading partner after the United States, overtaking the European Union (Coyer 2016, par.3). It already is the largest trading partner of Brazil, Chile and Peru and the second largest of Argentina and Venezuela (Pineo 2015, par.5). Additionally, China has established free trade agreements with Chile (2006), Peru (2010) and Costa Rica (2011) (Pineo 2015, par.15).

Although less important than trade, investment and loans are also a significant component of Sino-Latin American relations. When it comes to China’s investments in the region, these have reached an annual average of $10.7 billion during the last five years, and are expected to increase in the future. Most of these investments come from state-owned firms and tend to concentrate on specific sectors, with 57 percent of them financing commodity extraction (Dussel Peters 2015, p.9). As for loans, since 2005 China has lent nearly $100 billion to Latin America (Elson 2014, p.45). Lending by China was at its highest in 2010, when Chinese loans to the region were equivalent to those from the World Bank, Inter-American Bank and Export-Import Bank of the United States combined, but has since then decreased (Elson 2014, p.45). These loans tend to go to countries with limited access to alternative sources of funding, such as Venezuela, which alone has received around half of China’s loans to the region. Furthermore, they are often tied to specific projects and repaid in kind through oil sales (Elson 2014, p.45).

same time, many of the projects financed by China have been beset by problems linked to “social and political instability, environmental disputes, labor controversies, and disputes with local communities” (Dussel Peters 2015, p.10). Furthermore, Chinese loans to Latin America should be understood as unofficial components of China’s broader ‘One Belt, One Road’ strategy, an ambitious global infrastructure investment project aimed at maximising China’s geopolitical influence and access to resources (Chanda 2015, pars.2,11). Therefore, there are doubts as to whether these projects will contribute to the region’s long-term development “beyond serving as conduits for commodity flows”(Dussel Peters 2015, p.11).

The effects of China’s rise as a major loan provider in Latin America are likely to extend beyond the economic sphere. A defining feature of Chinese loans is that, unlike those provided by Western lenders, they come with no conditions attached. Since the 1980s, the international development assistance regime has been characterized by the practice of conditionality, that is, making development loans and aid contingent on the implementation of certain economic and/or political reforms in the recipient country (Babb & Carruthers 2008, p.13). At first, conditionality was understood mainly in economic terms, in the form of the stabilisation and structural adjustment programs of the IMF and World Bank (Selbervik 1999, p.12). These programs sought to fundamentally transform developing countries’ economies in accordance with the neoliberal economic orthodoxy of the Washington Consensus, through market-friendly policies such as privatisation, trade liberalisation and reduction of public spending (WHO n.d., pars.1-2). However, since the 1990s the concept of conditionality has been expanded to include political reforms aimed at improving good governance in recipient countries (Selbervik 1999, p.13). Therefore, most multilateral lenders now make their loans conditional on the implementation of reforms promoting “effective participation in public policy-making, the prevalence of the rule of law and an independent judiciary, institutional checks and balances through horizontal and vertical separation of powers, and effective oversight agencies” (Santiso 2001, p.5).

good governance in developing countries, leading to a more undemocratic and corrupt world (Kaplinski et al., 2007; Manning, 2006; Naim, 2009).

This leads us to our research question: What is the impact of Chinese loans on good governance in Latin America? The present study will conduct a comparative case analysis of three development projects in Latin America, one financed through Chinese loans and two financed through loans from the international financial institutions. The projects will be assessed in terms of four key dimensions of good governance: voice, performance, accountability and fairness. The aim of the research is therefore to compare the level of good governance of Chinese development projects vis-à-vis IFI-funded development projects so as to determine whether the increase in number of projects financed through Chinese loans will have a negative, neutral or positive impact on good governance in Latin America.

2.Theoretical Framework

In the present chapter we will introduce the research’s theoretical framework. The chapter will begin by presenting a literature review of the academic discussion surrounding the thesis’ main topics: good governance and China’s role in Latin America. Then, it will introduce and define its key concepts: good governance and development loans. Finally, it will present the thesis’ main hypothesis and its competing hypotheses.

2.1 Literature Review

Good Governance

The concept of good governance has its origins in the development literature of the late 1980s and the 1990s, a period which saw a renewed interest in the role of the state and its institutions among development scholars (Grindle 2010, p.4). This shift in attitudes was cemented by the publication of the World Bank’s 1997 World Development Report, subtitled The State in a Changing World. The report placed the state at the forefront of development thinking by highlighting its role as an important actor in the promotion of economic development. It therefore ushered in a clear break with the anti-statism which had dominated the previous decades (Weiss 2000, p.803). Since then, the concept of good governance has gained immense popularity among development scholars and practitioners and it is now widely employed by most international organisations (Gisselquist 2012, p.5).

The good governance debate was initiated and has been dominated by the international development agencies, each of which has its own definition of the concept (Wouters & Ryngaert 2004, p.4). For the World Bank, good governance is “the combination of transparent and accountable institutions, strong skills and competence, and a fundamental willingness to do the right thing”, which together “enable a government to deliver services to its people efficiently” (Wolfowitz 2006, cited in World Bank 2007, p.1). For the UNDP, good governance “refers to governing systems which are capable, responsive, inclusive, and transparent” which entails “meaningful and inclusive political participation” (Clark 2011, pars.2-3). The African Development Bank defines governance as “a process referring to the manner in which power is exercised in the management of the affairs of a nation, and its relations with other nations” and good governance as the presence in the aforementioned process of “accountability, transparency, combating corruption, participatory governance and an enabling legal/judicial framework.” (African Development Bank 1999, p.2).

In any case, we can say that definitions of good governance tend to make reference to either a government’s level of responsiveness to its citizens and ability to maintain the rule of law, or to the extent to which political institutions provide the proper incentives for government officials to do so (Keefer 2009, p.440). In other words, some scholars analyse good governance in terms of outcomes and others analyse good governance in terms of processes, although many definitions cross this divide.

consequences of this are confused analysis, inappropriate and counterproductive policy advice and eventually disillusionment with the concept itself as it inevitably fails to deliver in practice (Grindle 2010, p.9). Additionally, Doornbos argues that its ambiguity opens the concept to exploitation by actors who might use it as a “political tool” to justify decisions taken for other, less disinterested reasons (2001, p.104).

Various solutions are provided to the problems of ambiguity and idea inflation. Grindle advances the idea of “good enough governance”, that is, a move towards a minimalist conception of good governance which would strip it down to include only those elements which are absolutely essential for development to occur (Grindle 2010, p.14). Alternatively, Gisselquist suggests that academic researchers should disaggregate their analysis and focus on each component of good governance individually (rule of law, accountability etc.). This would furthermore enable them to engage with the already extensive literature covering each of these principles on its own (Gisselquist 2012, p.2).

In addition to new institutionalism, Max Weber’s theory of bureaucracy has also served as a source of inspiration for some good governance scholars (Andrews 2008, p.381). Weber’s work focused on bureaucratic institutions, which he argued were the most efficient type of organisation due to their rationality, standardised procedures, and technical expertise (Rockman n.d., pars.1-2). In any case, the theoretical foundations of good governance are decidedly underdeveloped. For instance, Andrews is critical of the “limited references to theory in the good governance literature” which furthermore, with the exception of North’s ideas, “are not consistent, referencing modernist Weberian models at some junctures, post-modern new public management at others” (2008, p.397).

Besides the definition of the concept, a second important debate among good governance scholars focuses on its link with economic development. Most scholars agree that good governance is a worthy goal in itself. However, there is disagreement on whether good governance can also be considered a prerequisite for economic development or not. Indeed, these concerns stand at the very root of the concept’s creation. Following the failure of structural adjustment programs in preventing widespread economic crises in the Third World in the 1970s and 1980s, the international financial institutions began to look for explanations. Their conclusion was that weak institutions and corruption in developing countries had prevented successful reform implementation and therefore economic growth (Kjaer 2014, p.1). To use Grindle’s term, good governance became a “fig leaf” for the failure of the IFIs’ policy advice (2010, p.5).

Among supporters of the good governance-development link we have first of all the World Bank. In its 1989 report Sub-Saharan Africa: From Crisis to Sustainable Growth, the organisation asserts that “sound macroeconomic policies and an efficient infrastructure” are by themselves not enough to ensure economic growth. Instead, they have to be accompanied by good governance measures which will foster an environment conducive to private sector initiative and entrepreneurship (World Bank 1989, p.xii).

construct six aggregate indicators measuring six dimensions of good governance: voice and accountability, political instability and violence, government effectiveness, regulatory burden, rule of law, and graft. After analysing the performance of developing countries in each of these dimensions, they find a “strong causal relationship from good governance to better development outcomes such as higher per capita incomes, lower infant mortality, and higher literacy” (Kaufmann et al 1999, p.1).

Keefer (2009) also argues that good governance has a positive impact on development. Furthermore, he makes an important contribution by noting that different components of good governance have a different influence on development. For example, while government credibility and the security of property rights have a strong positive impact on development, the link weakens when it comes to voice and accountability. Therefore, he concludes that future research would benefit from focusing on each component of good governance separately (Keefer 2009, pp.439-440).

Similarly, Resnick and Birner (2006) assert that good governance does have a positive impact on development, but that the causal relationship varies among its dimensions. While dimensions of good governance which relate to “a sound decision-making environment for investment and policy implementation” (ie. rule of law and political stability) contribute to economic growth, their impact on poverty reduction is unclear. Conversely, while dimensions of good governance which contribute to “transparent political systems” (ie. civil liberties and political freedom) contribute to poverty reduction, their impact on economic growth is unclear (Resnick & Birner 2006, p.iii).

then enable them to successfully improve good governance (Khan 2009, p.9). Similarly, Kurtz and Schrank argue that it is far more probable that it is economic development which produces good governance, rather than the other way around (2007, p.539).

Finally, the good governance agenda more generally has been the target of criticisms, which can be divided into two categories.

First of all, some scholars criticise the imposition of a one-size-fits-all model. For instance, Andrews argues that the good governance model has limited replicability: its various elements can lead to unexpected or even counterproductive results when applied to developing countries because “every context has prevailing structures that need to be built upon or given time to evolve” (2008, p.394,397). Furthermore, there exists great institutional variation even among the developed states which are frequently cited as examples of good governance. For example, Sweden, Denmark and the United States all have high-quality health and education; however, while in Sweden and Denmark the government is greatly involved in these sectors, in the United States it plays a relatively smaller role (Andrews 2008, p.385). In a similar vein, Messick’s (1999) analysis of the introduction of rule of law reforms in developing countries exposes the potentially negative consequences of one-best-way governance models. He discovers that “the sudden introduction of a formal mechanism to resolve legal disputes can disrupt informal mechanisms without providing offsetting gains” (Messick 1999, p.118).

health, education, worker benefits and rights among others” (1999 p.213, as cited in Reif 2013, p.65).

To summarise, good governance is a highly contested concept, which generally refers to a government’s level of responsiveness to its citizens, either at the process level or at the outcomes level depending on the specific definition. It was first introduced by the international development agencies, which continue to dominate the discussion. Although most scholars agree that good governance is a worthy goal in itself, disagreement exists on whether it has also a positive impact on development. Finally, some scholars are critical of the good governance agenda due to its imposition of a one-size-fits-all model and to its ties to neoliberalism.

China in Latin America

China’s growing economic influence in the developing world through the provision of development aid and loans with few conditionalities attached has sparked considerable academic debate. The discussion is divided into two broad sides, one portraying China as a threat to the economic development and political stability of developing countries, the other as a benevolent development partner (Alden 2007, p.111). In this section, an overview of the academic debate surrounding China’s emergence as a major donor and investor will be provided. It will begin by assessing the literature concerned with the impact on the developing world in general, to then move on to that focusing on the impact on Latin America in particular.

First of all, various scholars argue that China’s growing economic ties with developing countries is reinforcing their dependency on the export of natural resources as a source of income, thereby preventing them from pursuing the economic diversification necessary to promote long-term sustainable development. For instance, Konings describes how, whereas China’s imports from Africa are predominantly raw materials, in return it “exports the full gamut of its manufactured goods”, which range from textiles to high tech products (2007, p.357). As a result, cheap Chinese imports are displacing local products, undermining local African manufacturing industries (Konings 2007, pp.255-257). Similar concerns are raised by Zafar, who argues that the competition provided by growing imports of Chinese manufactured goods might “hinder economic diversification in Africa and contribute to deindustrialization” (2007, p.126). Furthermore, he predicts that Chinese investments in the extractive industries will provide no significant contribution to local job creation or human capital development - nor, for that matter, to “the continent’s long-term economic development” (Zafar 2007, pp.121, 126). Even Alden’s generally positive account of Sino-African relations admits that Africa’s long-term development will require a transformation of actual trade dynamics (2007, p.113). Finally, according to Coxhead similar dynamics are visible in Southeast Asia, where, due to the combined effects of China’s export boom and its demand for primary products, several countries are experiencing a reconfiguration of their economies favouring low-skill manufacturing and natural resource extraction to the detriment of high-value added production (2007, pp.1100, 1115).

The second main criticism leveled against China’s economic involvement in the developing world concerns the negative political impact caused by its provision of development aid and loans without conditionalities. According to Naim, China represents a threat to good governance worldwide by providing what he defines as “rogue aid”, or unconditional development assistance which is “nondemocratic in origin and nontransparent in practice” (2009, par.4). By providing aid without requiring any human rights or good governance policy reforms in return, China is undermining the efforts of Western development agencies to promote these values. It is therefore hurting the citizens of the countries it lends to and creating a world which is “more corrupt, chaotic, and authoritarian” (Naim 2009, par.11). This argument is supported by Kaplinski et al. (2007), who aim to demonstrate how China is weakening good governance in the developing world by citing the cases of Sudan, Angola and Zimbabwe, where, following Western donors’ withdrawal or refusal of aid due to concerns over corruption and human rights violations, China stepped in as an alternative donor, effectively removing any financial incentive for change. Similarly, Manning argues that the availability of non-conditional aid and loans could not only delay reforms, but also entrench “poor standards of governance and accountability” (2006, p.381). Finally, even Pehnelt (2007), who presents an otherwise relatively sympathetic account of China’s behaviour in Africa, accepts this criticism. According to him, as a late-comer to international commodity markets, China has higher “opportunity costs of morality”: it cannot afford to discriminate among its potential clients on the basis of humanitarian concerns (Pehnelt 2007, p.7). Consequently, “Chinese engagement enables African governments to reject demands made by the IMF, the World Bank and other donors for enhancing transparency, implementing anti-corruption strategies, and furthering their democratization efforts” (Pehnelt 2007, p.8).

First of all, Brautigam (2009) presents the emergence of China as a major donor as a positive development. She describes Sino-African economic relations as a “win-win approach” characterized by the prioritisation of investment partnerships over paternalistic aid; by the engagement of investment, trade and technology in the service of development; and by the mutually beneficial provision of credit in exchange for natural resources and contracts for Chinese businesses (Brautigam 2009, p.311). Another supporter of China’s economic relationship with the developing world is Woods, who argues that its aid recipients and trade partners "are enjoying higher growth rates, better terms of trade, increased export volumes and higher public revenues" (2008, p.1208). Similarly, for Kelley “Chinese investment in infrastructure and modernizing industry has the potential to kick-start stagnant African growth and begin a new era of economic development” (2012, p.41). Furthermore, if the right policies are adopted by Chinese and African governments, this economic growth could propel African countries out of the “resource curse” and into the path of sustainable development (Kelley 2012, p.41).

Scholars on this side of the debate are skeptical of accounts which portray China as entrenching dependent development in the Third World. For Brautigam, the competitive pressure created by China’s manufacturing exports is offset by Chinese investment into local industries. Contradicting Zafar (2007), she describes how these investments are creating employment for local workers (2009, p.308). As for the negative impact of the “resource curse” on good governance described by Kaplinski et al. (2007) and Zafar (2007), Brautigam argues that since Chinese loan agreements usually tie resource revenues to specific development projects, Chinese banks could in fact act as “agencies of restraint” on African leaders, reducing rent-seeking behaviour (2009, p.307). Su et al. (2016) similarly discredit the dependent development argument. Based on an empirical analysis of systematic data from 135 developing countries from 1995 to 2007, they conclude that there is no evidence in the developing world of a link between an increase in China’s economic presence and a decline in economic growth and manufacturing (Su et al. 2016, p.33).

First of all, it overestimates the effectiveness of traditional donors’ conditional aid and loans in promoting good governance, as “conditionality alone does not improve standards” (Woods 2008, p.1212). Secondly, she reminds us that China’s rise as a major donor is partly fueled by developing countries’ disillusionment with traditional donors’ imposition of conditionalities, perceived as excessively complicated and “misaligned with their priorities” at best, and undermining their national sovereignty at worst (Woods 2008, p.1217). Similarly, Brautigam argues that “where the West regularly changes its development advice, programs and approach in Africa (...), China does not claim to know what Africa must do to develop”, noting that policy conditionalities are now being criticised even by Western economists (2009, p.308).

China’s relationship with the developing world has generated considerable academic discussions. However, up until now the debate has been dominated by accounts of Sino-African relations. China’s impact in Latin America has produced a very limited although growing amount of academic literature, despite the impressive speed at which trade, investment and aid flows between the two have grown over the past fifteen years. Furthermore, most scholars have concentrated on trade relations rather than development aid or loans (Gallagher et al. 2012, p.3). The literature on China’s economic relations with Latin America can be divided along the same lines as the literature on its relationship with the developing world in general, with China portrayed as either a development partner or an exploitative power.

However, other scholars provide a more negative account by presenting China as following an exploitative, mercantilist strategy which will increase economic dependency and harm development in Latin America. According to Jenkins (2012), trade relations between China and Latin America are highly asymmetrical and defined by the same core-periphery dynamics which have undermined the region’s development for centuries. Similarly, Ortiz (2012) argues that Latin America is becoming increasingly dependent on exports of primary resources to China, which is problematic for its long-term economic development. Finally, according to Farnsworth, China pursues a “transparently mercantilist strategy” in the region, which is threatening the manufacturing sectors of countries such as Mexico and Brazil (2011, par.6,12). Furthermore, its loans are decreasing “the ability of the United States and other Western nations to promote labor and environmental protections, human rights and the rule of law in Latin America” (Farnsworth 2011, par.43).

To conclude, China’s economic presence in the developing world has attracted the attention of numerous scholars, divided between those who view China as an exploitative power and those who view it as a development partner. However, thus far the academic literature on China’s impact in Latin America has been very limited, especially with regards to development aid and loans. Studies of China’s international economic relations would benefit from giving greater attention to this underdeveloped research area in the future.

2.2 Conceptual Framework

2.2.1 Key Concepts

The present section will introduce the two key concepts of the research: good governance and development loans.

Good Governance

starting point is represented by the distinction between good governance in terms of outcomes and good governance in terms of processes (Keefer 2009, p.440). For the purposes of this research, it is the latter category which is the most relevant. First of all, since China’s economic presence in Latin America is a relatively recent phenomenon, it would be too early to properly assess its impact on good governance in terms of outcomes. Secondly, the thesis’ analysis of development projects will focus on their design, rather than on their results. Consequently, the following definition by the Good Governance Guide is particularly appropriate: good governance is “about the processes for making and implementing decisions. It’s not about making ‘correct’ decisions, but about the best possible process for making those decisions” (n.d., par.1). In other words, good governance refers to the existence of procedures and incentives which ensure that policy-makers are responsive to their citizens and deliver optimal results.

However, as defined above the concept of good governance remains quite ambiguous. What characteristics should the “best possible process” possess? Therefore, for greater precision it is necessary to outline the various components or principles of good governance. For this purpose, the UNDP provides a list of characteristics which are particularly relevant because they appear in most definitions of good governance across the literature (Graham et al. 2003, p.3). The UNDP’s characteristics of good governance are: participation, rule of law, transparency, responsiveness, consensus orientation, equity, effectiveness and efficiency, accountability and strategic vision (UNDP, 1997). However, in practice some of these characteristics tend to overlap and affect each other. To address this issue, Graham et al. group the UNDP’s characteristics into five broad principles of good governance: Legitimacy and Voice, Performance, Accountability, Fairness and Direction (2003, p.3). Therefore, in its analysis of good governance the present research will adopt Graham et al.’s set of principles, which will now be introduced in greater detail.

the right to freedom of speech (Art.19) and the right to freedom of association (Art.20) (UN, 1948). Participation is vital because it enables citizens to engage in shaping processes and institutions which have a direct impact on their lives, while at the same time allowing governments to “tap new sources of idea, information and resources when making decisions” (Caddy 2001, par.4). As for consensus orientation, it consists of taking into account the views of all groups in society with the aim of reaching a broad consensus which balances their various interests (Graham et al. 2003, p.3).

The second principle of good governance is Performance, which has two components. The first is effectiveness and efficiency, which refers to processes which “produce results that meet needs while making the best use of resources” (Graham et al. 2003, p.3). The second is responsiveness, which is present when “ institutions and processes try to serve all stakeholders” (Graham et al. 2003, p.3). However, since this second component seems to overlap with some of the others (ie.consensus orientation, accountability and equity), it will be omitted in this research.

The third principle of good governance is Accountability. This principle has two components: accountability and transparency. Accountability requires that decision-makers are subject to the oversight of the public (Graham et al. 2003, p.3). This entails both answerability, or the provision of justification for their actions, and enforcement, the power to sanction decision-makers for misbehaviour. There are two forms of accountability: horizontal and vertical. Horizontal accountability is the oversight exercised by governmental institutions over one another. Vertical accountability is the oversight exercised by citizens and civil society over decision-makers. Despite this division, it is important to note that some mechanisms of horizontal accountability, for example parliaments, can also play a role in vertical accountability, and viceversa (Stapenhurst & O’Brien 2005, p.1). As for transparency, it refers to the “free flow of information” (Graham et al. 2003, p.3). Information about state institutions and their initiatives must be available to the general public and especially to those directly affected by them; furthermore, the information must be easy to access and to understand (Graham et al. 2003, p.3).

their wellbeing” (Graham et al. 2003, p.3). This component is enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which states that “all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights…” (Art.1), “without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status” (Art.2) (UN, 1948). As for rule of law, it consists in the fair and impartial application of “well-established and clearly written rules, regulations, and legal principles”, particularly those concerning human rights (Voigt 2013, p.xv)(Graham et al. 2003, p.3). It is based on the UDHR’s Article 7 (“All are equal before the law”), Article 10 (“Everyone is entitled in full equality to a fair and public hearing by an independent and impartial tribunal…”), Article 5 (“No one shall be subjected to arbitrary arrest, detention or exile”) and Article 17 (“No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his property”)(UN, 1948).

The fifth and final principle of good governance is Direction. Its main component is strategic vision, which requires that government officials have a strong long-term commitment to good governance and human rights which shapes and determines their decision-making (Graham et al. 2003, p.3). However, since this principle is suitable for the national and/or institutional levels of analysis but not quite as relevant for the project level of analysis, it will not be included in our research.

Development Loans

Global development finance is characterised by a complex architecture involving various state and non-state actors. Financial flows to developing countries can occur through private or official channels. Private flows include foreign direct investment (FDI), worker remittances, portfolio equity, and private debt and grants. More relevant to the present research are official flows, which can be further subdivided between Official Development Assistance (ODA) and Other Official Flows (OOF) (Brautigam 2011, p.204).

the recipient country (Brautigam 2011, p.203; OECD 2008, p.1). These must be “concessional in character” and contain “a grant element of at least 25 per cent (calculated at a rate of discount of 10 per cent)” (OECD 2008, p.1). There are two forms of ODA: grants and concessional loans. Concessional loans differ from regular market loans in that they offer more generous terms, whether through lower interest rates or longer grace periods (OECD 2003, n.p.).

As for other official flows (OOF), these include military aid, export-facilitating bilateral transactions, subsidies or other forms of funding which support the private investments in recipient countries of companies from the donor country, and loans which are not concessional or which do not have a grant element of at least 25% (Brautigam 2011, p.204).

In this research, the umbrella term ‘development loans’ will be utilised to refer to all loans provided to developing countries by official institutions which contribute to some extent to the development of the recipient country. It therefore includes both ODA loans and OOF loans: they can be concessional or non-concessional and have any percentage of grant element. Furthermore, this concept will be subdivided into two subcategories: development loans from China and development loans from the IFIs, to which we now turn.

While most donor countries provide some degree of bilateral assistance through their own agencies, it is the international financial institutions (IFIs) which sit at the heart of the global development assistance regime. Foremost amongst them are the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the Bretton Woods institutions established at the end of the Second World War to maintain global economic stability.

loan negotiations are conducted between the Bank and the recipient country, in which the objective, outputs and operational plan of a specific development project or program are determined. The loan is then approved and it is up to the recipient country to implement the project, with the continuous supervision of the World Bank, which at the end evaluates the project’s results. Furthermore, “all loans are governed by operational policies, which make sure that operations are economically, financially, socially and environmentally sound” (World Bank n.d.[a], section 5).

As for the IMF, it is an international organisation which provides financial assistance to countries who find themselves unable to secure sufficient funds through capital markets to repay their external debt while maintaining appropriate reserve levels. Its loans help them “tackle balance of payments problems, stabilize their economies, and restore sustainable economic growth” (IMF n.d., par.2). While the World Bank provides funding for local development projects, the IMF focuses on macroeconomic issues (IMF n.d., par.3). It is not a development bank nor an aid agency, so its loans are given out on the condition that recipients repay them expediently and implement in exchange a series of Structural Adjustment Policies (SAPs) (Heakal n.d., par.12). While the World Bank generally lends to developing countries, with more favourable conditions for the poorest of them, the IMF offers financial assistance to all its members (Driscoll 1996, pars.11-12). However, in the past few years its role as a provider of development assistance has expanded. In 2010, it established the Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust, which offers concessional loans to low-income countries through three channels: the Extended Credit Facility, the Standby Credit Facility and the Rapid Credit Facility (IMF 2016, p.1). In 2015, the IMF expanded developing countries access to concessional loans. More recently, it “adopted a strategy to support concessional lending of about $1.8 billion a year over the longer term…” (IMF 2016, p.1).

par.1). The Bank provides financing for development projects through two credit windows: Ordinary Capital and the Fund for Special Operations (FSO). The Ordinary Capital provides loans with more generous terms than market loans, available to all countries, while the FSO provides loans with extremely low interest rates and extended repayment periods, available only to the region’s poorest countries (State Secretariat for Economic Affairs & Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation 2015, p.2)

In recent years, China has increasingly come to challenge the traditional donors’ monopoly over international development assistance. The Chinese government provides three forms of official development assistance: grants, interest-free loans and concessional loans (Brautigam 2011, p.204). However, the majority of China’s international development assistance is composed of various OOF-like financing instruments: export credits, OOF-type loans, overseas investment support and multilateral financing mechanisms (Snell 2015, pp.11-12, 23). China’s OOF-type loans can be subdivided into three categories. The first is non-ODA concessional loans, which contain a grant element lower than 25 percent and can be tied to the purchase of Chinese goods and services. The second is nonconcessional loans, which are loans with a commercial interest rate. The third is resource-backed loans, which are loans “repaid through the sale of natural resources to donor entities; can be concessional, earmarked for infrastructure projects, and/or tied to exports” (Snell 2015, p.12). Most of China’s international development assistance is provided by China Eximbank and China Development Bank, while China’s Ministry of Commerce oversees the provision of grants and interest-free loans (Brautigam 2011, p.204).

Causal Relationship: Development Loans and Good Governance

Proponents of political conditionality argue that conditional development loans can have a positive impact on good governance. For instance, the World Bank’s 1998 report Assessing Aid: What Works, What Doesn’t, and Why called for a more selective approach to development assistance based on countries’ commitment to political reform. According to the the World Bank, this would enable donor agencies to create the incentives for wider good governance reform among developing countries (World Bank 1998, pp.118-119). Since then, most bilateral and multilateral aid agencies have adopted the practice of conditional lending, through which good governance has become an objective of the development assistance regime (Singh, 2003).

However, there are also those who argue that development loans with political conditionalities fail to promote good governance and in some cases can even discourage it. First of all, conditionalities fail to create the incentives to improve good governance because sustainable, long-term political reform cannot be externally imposed or bought when there is domestic opposition or unwillingness (Killick 1998, p.163; Santiso 2001, p.8; Stiglitz 1999, p.591). Secondly, the imposition of conditionalities can negatively impact good governance by undermining sovereignty and replacing domestic democratic processes (Santiso 2001, p.9; Stiglitz 1999, p.591). Finally, development lending can sometimes create a dependency which fosters corruption in recipient countries. Therefore, there is the concern that an overreliance on conditional loans might actually be counterproductive for the promotion of good governance (Melese n.d., par.13; Santiso 2001, p.9).

anti-corruption reforms, considering that “anti-corruption is still commonplace within Chinese businesses themselves” (Condon 2012, p.7).

2.2.2 Main Hypothesis and Competing Hypotheses

The present research aims to assess the impact of China’s development loans on good governance in Latin America. However, Chinese lending in this region seems to concentrate predominantly on the extractive and infrastructure sectors (Gallagher et al. 2012, p.2). For this reason, analysing its impact in terms of good governance at the national level might not be appropriate or indeed even possible. Therefore, the research will shift its level of analysis to focus on good governance at the project-level. In other words, the level of good governance of Chinese development projects vis-à-vis IFI-funded development projects will serve as a proxy indicator for the impact of China’s loans on good governance in Latin America. The present section will now introduce the thesis’ main hypothesis and its two competing hypotheses.

Main Hypothesis: China’s loans have a negative impact on good governance

China’s development lending strategy focuses on economic goals and does not contain a good governance component (Naim 2009; Kaplinski et al. 2007; Manning 2006; Penhelt 2007). Consequently, we might expect its development projects to be designed with little concern for participation, transparency, accountability or other principles of good governance. Therefore, we hypothesize that development projects financed by China will have a lower level of good governance than development projects financed by the IFIs. The propagation of development projects with below-average levels of good governance will in turn lower overall good governance standards in the recipient country. As a result, China’s loans will have a negative impact on good governance in Latin America.

Competing Hypothesis 1: China’s loans have no impact on good governance

might thus have been adapted to some extent to those of the traditional donors, if not at the policy and strategy level, then at least at the implementation level.Therefore, it is possible that development projects financed by China will have a similar level of good governance to development projects financed by the IFIs. As a result, China’s loans will have no significant impact on good governance in Latin America.

Competing Hypothesis 2: China’s loans have a positive impact on good governance

3. Research Design

To answer our research question, we will conduct a comparative case analysis of three development projects in Latin America, one financed by Chinese loans and two financed by the IFIs’ loans. More specifically, the contracts of each project will be evaluated in terms of good governance, using content analysis as a research method.

In the present chapter, the thesis’ research design will be introduced in greater detail. The chapter will begin with the operationalisation of the two key concepts into four dependent variables, one independent variable and one extraneous variable. Then, it will introduce the thesis’ research approach, the Most Similar Systems Design. This will be followed by a section on the thesis’ case selection. The chapter will then introduce the research method, content analysis. Finally, the chapter will present a set of limitations to our methodology.

3.1 Operationalisation of Concepts

3.1.1 Dependent Variables

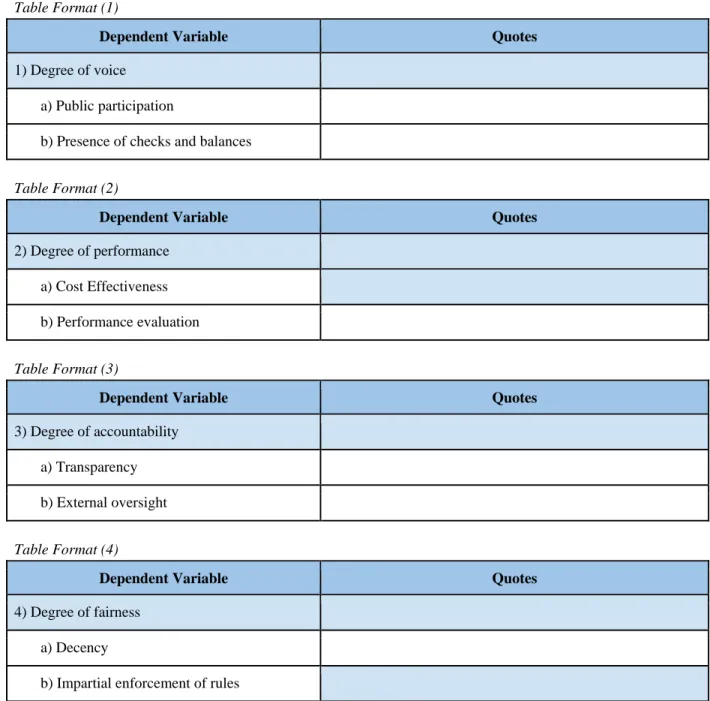

The concept of good governance can be transformed into four dependent variables, each corresponding to one of its four dimensions, which are voice, performance, accountability, and fairness. In order to properly assess the projects’ level of good governance we must in turn assign to every dependent variable a set of measurable indicators. We will create two indicators for each dependent variable so as to ensure a balance between the four dimensions of good governance. These indicators will be reflective of the dimension components which were outlined in the previous chapter. The data for the indicators of the dependent variables will be obtained primarily from the analysis of project contracts and secondarily from the analysis of academic and NGO reports.

difficulties, as most pre-existing good governance indicators focus on governance at the national level (ie. the World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators, the OECD’s Sustainable Governance Indicators and the Global Integrity Index). Therefore, to maximise relevance our measurements will be based on the less well-known governance indicators provided in Abrams et al.’s handbook Evaluating Governance. The handbook presents a set of guidelines for participatory assessments of good governance levels in the management of protected areas (Abrams et al., 2003). While not immediately evident, its indicators are appropriate to our research for three reasons. First of all, development projects and protected areas involve similar levels of governance, as they both have a relatively small-scale or local scope. Secondly, they both require governance which strikes a balance between national interests and local stakeholders’ rights. Thirdly, development projects must deal with many of the issues characteristic of the governance of protected areas, such as environmental damage and the rights of local communities. Therefore, the thesis’ good governance indicators will be based on those provided in Abrams et al.’s handbook, with some modifications. We will now explain in greater detail each dependent variable and its indicators.

The first dependent variable is degree of voice. It refers to the extent to which the planning and implementation of a development project were conducted in accordance with the principle of voice. In other words, this variable measures the degree to which decision-makers enabled citizens to participate in the project’s development and strove to reach a balance between the interests of the various stakeholders.

without fear of reprisals. Furthermore, the project’s decision-makers must be responsive to these criticisms and modify or at least justify their decisions accordingly.

We now turn to the second dependent variable, which is the degree of performance. It refers to the extent to which the planning and implementation of the development project were conducted in accordance with the principle of performance. In other words, this variable measures the degree to which the project is designed in such a way as to ensure optimal effectiveness and efficiency in its implementation.

The variable’s first indicator is cost effectiveness. It measures the extent to which the project is designed in such a way so as to make the best use of the recipient country’s financial resources. More specifically, this indicator will compare the conditions of the development loan financing the project to the conditions offered by other available loan providers, especially with regards to interest rates and repayment periods. The variable’s second indicator is performance evaluation. It measures the presence and comprehensiveness of mechanisms for assessing the project’s outputs vis-à-vis pre-established objectives during and/or after its implementation.

We now turn to the third dependent variable, which is the degree of accountability. It refers to the extent to which the planning and implementation of a development project were conducted in accordance with the principle of accountability. In other words, this variable measures the degree to which the project’s planning and implementation was subject to external oversight as well as the degree to which the public had access to complete and comprehensible information on the project itself.

mechanisms must be in place to prevent corruption, rent-seeking, mismanagement and waste throughout the project’s development.

Finally, the fourth dependent variable is the degree of fairness. It refers to the extent to which the planning and implementation of a development project were conducted in accordance with the principle of fairness. In other words, this variable measures the degree to which decision-makers strove to ensure that the project accords a fair and equitable treatment to all actors involved and is developed in respect of the rule of law.

The variable’s first indicator is decency. It measures the extent to which the project is designed and implemented “without humiliating or harming people”. We employ a broad definition of harm which includes environmental damage (Abrams et al. 2003, p.37). The variable’s second indicator is impartial enforcement of rules. It measures the extent to which the project is developed in accordance to national rules and regulations.

3.1.2 Independent Variable

3.1.3 Extraneous Variable

Finally, it is important to take into consideration the fact that the project contracts are embedded in a broader institutional context. The level of good governance of project contracts could be determined not only by the identity of the loan provider, but also by the national regulations of the country in which they are implemented, which might in some cases render unnecessary the inclusion of certain good governance provisions. In other words, it is possible that national regulations might act as an extraneous variable influencing the causal relationship between our independent and dependent variables. Therefore, in order to ensure the internal validity of the research, national regulations of relevance to the four dimensions of good governance will be analysed so as to control for their potential impact.

Table 1. Variables and Indicators

Dependent Variables Indicators

Degree of voice - Public participation

- Presence of checks and balances

Degree of performance - Cost effectiveness

- Performance evaluation

Degree of accountability - Transparency

- External Oversight

Degree of fairness - Decency

- Impartial enforcement of rules

Independent Variable Indicators

Identity of the main external lender - Percentage of the total cost of the project which is financed by the external lender, which must a) Represent at least 25% of total project cost

b) Be three times more than the total percentage contributed by all other external lenders

Extraneous Variable

3.2 Research Approach

The present research will be conducted through a qualitative case study approach. Case study research consists in the in-depth analysis of a single or a small number of cases with a strong attention to their context (Yin 2012, p.4). In turn, a case can be any “bounded entity” which serves as unit of analysis, for instance “a person, organization, behavioral condition, event, or other social phenomenon” (Yin 2012, p.6). Case study research is particularly suited to the determination of causality due to its emphasis on the detailed examination of processes and outcomes (Goodrick 2014, p.1).

Case study research has been deemed more suitable for the purposes of this thesis than large-n analysis or other forms of quantitative research due to the subjective nature of good governance. While it is a relatively straightforward process to assess the impact of development loans on child mortality, poverty levels or other quantifiable phenomenons, it is quite difficult to measure abstract values such as “participation” or “accountability”. As Singh states it, “the quality of governance cannot be measured in quantitative terms” (2003, n.p.). For this reason impact evaluations of development funding with regards to good governance have lagged behind despite the rising prioritisation of good governance among donors and lenders (Garbarino & Holland 2009, p.4). A further complication is caused by the fact that analyses of good governance are by their very nature evaluations of the quality of governments, the very actors which tend to be responsible for producing data on a country’s performance across various issue areas. This means that “no complete cross-country, objective data are available, particularly from the underdeveloped nation states” (Besançon 2003, p.5). Therefore, when analysts measure good governance, they tend to do so through subjective criteria, for example by systematically gathering the opinion of experts on each good governance dimension individually or by conducting surveys on the public’s and businesses’ perception of the level of good governance in their country (Court et al., 2007 p.8).

2016). Comparative (or multiple) case designs focus instead on obtaining and comparing data from two or more cases with the aim of testing one or more hypothesised causal relationships. Central to this is the concept of replication. Comparative case designs seek to determine causality by either selecting cases based on the expectation of similar outcomes (direct replication) or by selecting cases based on the expectation of contrasting outcomes (theoretical replications) (Yin 2012, p.8).

Since our research question seeks to analyse the impact of Chinese loans on good governance not in a specific country but across Latin America, the research will employ a comparative case design so as to increase generalisability. Furthermore, it will rely on theoretical replication. Instead of comparing various cases of Chinese-financed projects, it will contrast one Chinese-financed project with two IFI-financed projects, with the expectation of different impacts on good governance levels depending on the identity of the loan provider. The reason for this decision is that the rise of China as a major loan provider in Latin America is happening not in a vacuum, but instead in the context of the IFIs’ established dominance as the region’s main source of external funding. Therefore, the impact of Chinese loans on good governance in Latin America should be assessed in relation to the impact of the IFIs’ loans.

Comparative case studies can be further subdivided into the Most Similar Systems Design (MSSD) and the Most Different Systems Design (MDSD). The MSSD consists in the comparison of cases which are as similar as possible yet differ in the phenomenon of which we seek to explain the effects (explanatory variable). Conversely, the MDSD consists in the comparison of cases which are as different as possible, yet share a similar outcome (outcome variable), with the aim of explaining the causes behind this similarity (Anckar 2008, p.389-390).

vis-à-vis the effects of the IFIs’ loans, rather than explain the causes behind similar levels of good governance, the former approach will more suitable. Additionally, MDSDs usually require the comparison of cases which share the same outcome variable, while this is not necessary for MSSDs, which tend to require only that the cases have different explanatory variables (Anckar 2008, p.393-394). Therefore, since our research question is not concerned with explaining a specific outcome variable (ie. high or low good governance), the MSSD is the most relevant of the two approaches.

3.3 Case Selection

As stated in the previous chapter, since China’s loans to Latin America tend to concentrate on the extractive and infrastructure sectors, it is quite difficult to properly assess their impact on good governance at the national level. Therefore, we will instead analyse their impact on good governance at the project-level. The unit of analysis will be development projects and the population will be all development projects in Latin America. Since we are adopting a comparative research approach, this includes both development projects financed by China and development projects financed by the IFIs. More specifically, the research will conduct a comparative analysis of three development projects across two countries, Ecuador and Peru. The present section of the thesis will introduce and explain its case selection. First, it will provide an overview of the two countries selected. Then, it will provide an introduction to each of the three development projects which have been selected as the cases to be compared.

explanatory variable, in which they differ: since 2005, China has been Ecuador’s main lender, while Peru has continued to depend on the IFIs’ development loans. Therefore, our research will focus on development projects in Ecuador and Peru which were implemented between 2005 and 2015.

Ecuador is a country of around 16.3 million inhabitants on the west coast of Latin America (Focus Economics, 2016). It is classified as an upper-middle income economy by the World Bank and placed in the 0.700–0.749 band of the UN Human Development Index (UNDP, 2014; World Bank, 2015). Ecuador’s economy is characterised by the export of primary goods and the import of capital and manufactured products typical of developing countries (Puyana de Palacios 2014, p.120). For instance, Ecuador is excessively dependent on oil extraction, which represents over half of its export earnings and around 25% of its public sector revenues (CIA 2016, n.p.) Furthermore, net oil revenue is limited by the country’s inadequate refining capacity, which forces it to import refined petroleum products (U.S. Energy Information Administration 2015, par.1). Ecuador’s remaining top exports are bananas, crustaceans and cut flowers, while its main imports are refined petroleum, coal tar oil, cars, packaged medicaments and petroleum gas (Observatory of Economic Complexity n.d.[a], par.2).

In 2006, left-wing economist Rafael Correa became president promising political reform through a Constituent Assembly, the rejection of neoliberalism and increased independence from the IFIs and the United States (Wolff 2013, p.108). Under Correa, there has been a substantial increase in spending on agricultural subsidies and social programs in Ecuador, especially in the areas of health care, education and infrastructure (Encyclopædia Britannica 2016, par.4). As a result, the president has been able to maintain high approval ratings, so much so that in 2013 he was elected for a third consecutive term. However, Correa has also been criticised for his crackdown on independent media and been accused of “seeking to override Ecuador's democratic institutions and amass too much power for himself” (BBC 2013, par.12).

In 2008, Ecuador voluntarily defaulted on US$3.2 billion of foreign bonds, amounting to around 30% of its total public external debt (CIA 2016, n.p.). President Correa justified this decision on the grounds of irregularities in the 2000 negotiation process resulting in the contraction of the debt, which was therefore illegitimate (The Economist 2009, par.2). The following year, Ecuador repurchased 91% of its defaulted bonds in an international reverse auction (CIA 2016, n.p.).

As a consequence of its sovereign debt default, since 2009 Ecuador has had to become increasingly dependent on China as its only available source of loans. From 2010 to 2015 Ecuador received a total of $15.2 billion in Chinese loans, which makes it China’s fourth largest borrower in Latin America after Venezuela, Brazil and Argentina (Gallagher & Myers, 2014).These loans are often linked to Ecuador’s oil production, whether directly, in the form of various oil-for-loan deals through which loans repayments take the form of oil exports at market prices, or indirectly, in the form of “large-scale loans (...) that coincide with oil supply agreements” (U.S. Energy Information Administration 2015, par.8). Furthermore, they also come with the requirement that the projects they fund employ goods and services from Chinese companies (Krauss & Bradsher 2015, par.48).

same time there are some concerns over a potential entrenchment of Ecuador’s commodity dependence, since Chinese loans tend to fund infrastructure which essentially facilitates the transportation of resources out to China. Another criticism relates to Chinese companies’ lower occupational safety and environmental standards (Lee 2015, par.23).

The research’s second country is Peru, a country of around 31.9 million inhabitants which is also on Latin America’s western coast (Focus Economics, 2016). It is at a similar level of development as Ecuador, being also classified as an upper-middle income economy by the World Bank and placed in the 0.700–0.749 band of the UN Human Development Index (UNDP 2014, p.161; World Bank, n.d.[b]). Peru tends to export raw materials and import capital and manufactured products. Its main exports are gold, copper ore, refined petroleum, refined copper, and petroleum gas. As for its main imports, they are refined and crude petroleum, cars, delivery trucks and computers (Observatory of Economic Complexity n.d.[b], par.2).

Peru was one of the many countries transformed by Latin America’s neoliberal wave of the 1990s. Its neoliberal period began with the election of Alberto Fujimori in 1990, who saw an embrace of neoliberalism as the best strategy for achieving economic growth and stability in the country (Silva 2009, p.237). A comprehensive set of structural reforms was soon implemented, which included “foreign exchange rate unification and liberalization, deeper trade liberalization, removal of export taxes, capital market liberalization, state employment cuts, elimination of employment security laws, elimination of wage indexation, and flexibilisation of labor relations” (Silva 2009, p.238). Fujimori’s administration became increasingly repressive and authoritarian, and was marked by severe human rights violations. Through the dissolution of the legislature in 1992 and a constitutional reform in 1993 he was able to rule until 2000, when he was forced to resign by a corruption scandal (Taft-Morales 2013, p.1).

inadequate justice system, to stop the rampant corruption or to address the human rights violations inherited from the Fujimori regime (Silva 2009, p.246). Toledo was succeeded by Alan Garcia, whose presidency (2006-2011) featured a similar mix of orthodox macroeconomic policies, high growth, and socioeconomic exclusion (Taft-Morales 2013, p.1). Finally, in 2011 Ollanta Humala was elected president, promising both to maintain free-market policies and to address economic inequality (Taft-Morales 2013, p.2). Following his defeat by Garcia in 2006, Humala had abandoned his previous far-left nationalistic stance, reinventing himself as a centre-leftist along the lines of Brazil’s Lula da Silva (Reuters 2013, par.7). Humala has enjoyed higher approval ratings than his predecessors, in great part due to his implementation of extensive social programs for the poor (Reuters 2013, par.11). However, more recently his popularity has declined due to “failed campaign promises, (...) political scandals involving members of his government, (...) disenchantment with his handling of social conflicts”, as well as a slowing economy (Hollar 2016, pars.7-8).

When it comes to development loans, Peru has continued to the present day to rely on the international financial institutions, unlike Ecuador. For instance, from 1990 to 2015 it received over $7 billions in loans from the World Bank (Martin-Prevel & Kim 2015, p.2). Its structural adjustment reforms have earned it praise from the Bank: in 2016, it was ranked 2nd in Latin America by the Bank’s Doing Business survey, indicating a “regulatory environment (...) conducive to the starting and operation of a local firm” (World Bank n.d.[c], par.1). However, the activities of the World Bank and other IFIs’ have been criticised by some as detrimental to Peru’s environmental and social conditions. According to the Oakland Institute, “the World Bank’s projects and involvement with the private sector in the country have notably been associated with violent clashes with local communities” (Martin-Prevel & Kim 2015, p.8).