protection were won for all children.8’9 Unfortu-nately, it was not until Kempe’s’#{176} description of the

battered child syndrome in 1962 that child abuse

was widely recognized by the medical community.

Despite

growing

concern,

corporal

punishment

re-mains a common practice among parents and

edu-cators

alike.

In

1975,

the

US

Supreme

Court”

up-held the right of schools to use corporal

punish-ment. As recently as 1984, 47 states allowed the use of corporal punishment in school.4

The

negative

effects

of corporal

punishment

are

well described. Immediate emotional and

psycho-logic

effects

include

embarrassment

and

sense

of

worthlessness. Spanking creates an air of mistrust,

anger,

resentment,

and

confusion

on the

part

of the

child.’2

It has

further

been

suggested

that

spanking

may contribute to delinquency and

counterproduc-tive

behavior.”2

Corporal

punishment

may

tempo-rarily alter behavior; however, it is an ineffective long-term solution.6 In addition to the adverse

psy-chological

effects

and

lack

of

long-term

efficacy,

spanking can result in severe physical injury and

even

death.

Major

tissue

damage,

central

nervous

system hemorrhage, spinal injury, and sciatic nerve

damage

are

documented

complications.’2

The

pa-tient

we describe

is unique.

She

had

sufficient

sub-cutaneous

bleeding

to result

in hypovolemic

shock;

yet there was no initial bruising. This case supports

the commonly ignored fact that spanking a child

with any object may result in severe injury. Clearly,

no matter how controlled a parent or educator may

intend

to be,

his

or her

anger

and

frustration

may

inadvertently intensify the severity of the punish-ment.6 This case reemphasizes the need for parents,

educators,

and

especially

health

care

professionals

to condemn the use of physical force as a means of

discipline. The American Academy of Pediatrics4

has firmly stated its opposition to the use of

cor-poral

punishment

in school.

Pediatricians

are

in an

ideal position as advocates for children to educate

parents and educators about the consequences and

futility of corporal punishment and offer practical, efficacious nonviolent alternatives.7

Scorr

P.

EICHELBERGER,MD

DOUGLAS

W.

BEAL,MD

RONALD

B.

MAY,MD

Dept

of Pediatrics

East Carolina University School of Medicine

Greenville,

NC

3. Hiner RN. Children’s Rights, Corporal Punishment, and Child Abuse. Bull Menninger Clin. 1979;43:233-248

4. American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on School Health. Corporal punishment in schools. Pediatrics. 1984; 73:258

5. Smith JD, Pulloway EA, West KG. Corporal punishment and its implications for exceptional children. Except Child. 1979;45:264-268

6. Wessel MA. The pediatrician and corporal punishment.

Pediatrics. 1980;66:639-641

7. Christophersen ER. The pediatrician and parental disci-pline. Pediatrics. 1980;66:641-642

8. Riis JA. The Children of the Poor. New York, NY: Arno Press and The New York Times;1971:142-152

9. Radbill

SX.

Children in a world of violence: a history of child abuse. In: Helfer RE, Kempe, RS, eds. The Battered Child. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press;1987:3-22 10. Kempe CH, Silverman FN, Steele BF, Drolgemueller W,Silver HK. The battered child syndrome. JAMA. 1962;

181:17-24

11. Ingraham V. Wright 1401, 1407, 1408, 1409, 1410 (97 Su-preme Court 1977)

12. Hymen IA, Wise JH. Corporal Punishment in American Education: Readings in History, Practice, and Alternatives.

Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 1979

Collodion

Baby,

Sign of Tay

Syndrome

Contemporary

pre-

and

neonatal

care

has

pro-longed

the

survival

of newborns

with

severe

gen-odermatoses,

including

the

harlequin

and

collodion

baby

phenotypes.’

This

has

provided

an

excellent

opportunity

for longitudinal

observations

that

have

illustrated the nonspecificity of these clinical

con-cepts

and

the

limited

number

of ways

integumen-tum commune has in responding to varied noxae.

In addition,

such

observations

reflect

the

long-term

dynamics of skin changes. The dynamics could lead

to

a string

of sometimes

even

contradictory

mor-phologic

diagnoses.

I describe

a collodion

baby

by

phenotype,

a girl

who

in time

had

several

different

diagnoses.2

Eventually,

an

8-year

period

of

reeval-uations with several cutaneous biopsies and hair

analysis resulted in a diagnosis considered accurate

and

etiologically

sound.

CASE

REPORT

The patient was the product of the second uneventful pregnancy for a nonconsanguinous 21-year-old mother and 23-year-old father. Fetal activity was reportedly

corn-REFERENCES

1. Welsh RS. Spanking: a grand old American tradition? Chil-dren Today. January-February 1985:25-29

2. Dubanoski RA, Inaba M, Gerkewicz K. Corporal punish-ment in schools: myths, problems, and alternatives. Child Neglect. 1983;7:271-278

Received for publication Jan 24, 1990; accepted May 7, 1990. Reprint requests to (B.G.K.) Regional Genetics Program, Uni-versity of South Florida College of Medicine, Box 15-G, 12901 Bruce B. Downs Blvd, Tampa, FL 33612-4799.

,

I

Fig 1.

Collodion baby phenotype at birth.572

PEDIATRICS

Vol. 87

No. 4 April

1991

parable with that of the previous pregnancy. The delivery was by cesarean section for fetal distress at 37 weeks’ gestation. Birth weight was 1900 g and length 45.8 cm (small for gestation). Parchment-like skin was noted with underlying erythema (Fig 1). Limited range of motion was present in all large joints. A diagnosis of collodion baby secondary to lamellar ichthyosis, a proven autoso-mal recessive trait (Mendelian inheritance in man (MIM) number 24230)3 was presumed. Horizontal nystagmus was noted shortly after birth. With adequate feeding, meticulous skin care and physical therapy, the infant grew slowly. Developmental milestones were recorded as “sat at 6 months, crawled at 12 months, and took steps with support at 13 months.”

Skin biopsy at age 12 months showed hyperparakera-totic squamous epithelium with multifocal acanthosis. The granular layer was preserved. Mild increase of dermal collagen fibriles and a few lymphocytic infiltrates were present. The interpretation was congenital autosomal recessive ichthyosiform erythroderma (MIM 24210). At age 19 months, short stature, intermittent horizontal nystagmus, dry, scaly skin, sparse scalp hair, and mild dystrophy of the nails were present (Fig 2). Cataracts were not evident. Renal, gastrointestinal, pancreatic, and thyroid functions appeared normal. Immunoglobulins, sweat test, and computed tomographic head scan showed no abnormalities. On skeletal survey, coarse reticulation of the lumbar vertebrae and pelvis were present. The bone age was delayed (12 months). Repeat skin biopsy showed a dense keratotic layer with a few keratin plugs.

Fig 2.

Proposita at 19 months of age. Top, Great change in appearance. Note nail involvement. Bottom, Sparse short hair with underlying scaling.at Viet Nam:AAP Sponsored on September 2, 2020

www.aappublications.org/news

The granular layer was thin and the malpighian layer appeared normal. No inflammatory changes were noted. The impression was ichthyosiform dermatitis with his-tology reminiscent of ichthyosis vulgaris, a proven auto-somal dominant trait (MIM 14670).

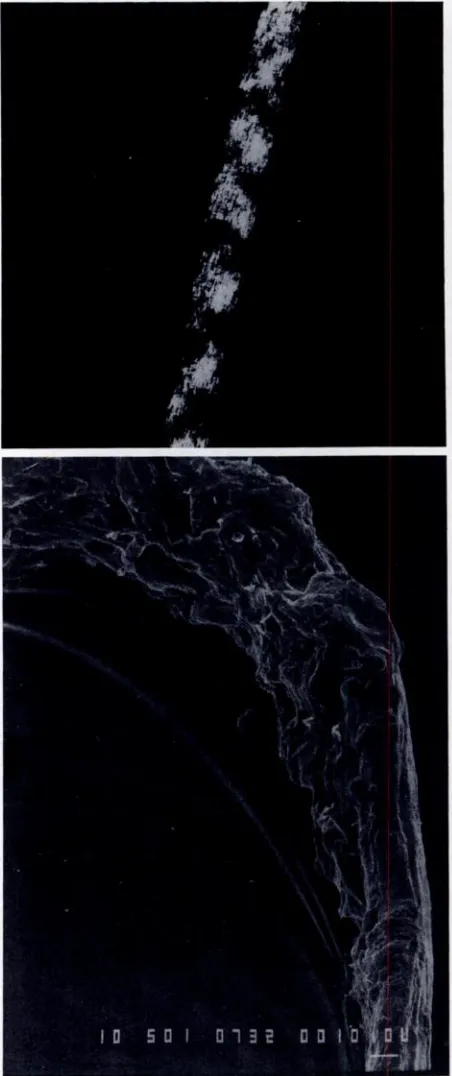

Light microscopy of scalp hair showed shafts with an undulating wavy contour. The pigment granules in the cortex had a similar wavy distribution. In many areas, the hairs were markedly flattened and folded over like a thick ribbon. Abrupt changes in hair shaft diameter were present in some areas. Trichorrhexis nodosa-like frac-tures were seen. Release of individual cortical cells, how-ever, was not a prominent feature. With polarized light, alternating bright and dark domains were seen along parts of the shaft (Fig 3, top). Scanning electron micros-copy at 500, 800, and 1000 magnification indicated severe dystrophy of the hair shaft. An amorphous coat of debris was present instead of cuticle (Fig 3, bottom). The cortex was practically nonexistent and extensive cavitation dis-rupted the cuticle. The sulphur content of the hair was markedly decreased: 1.83 ± 0.43% (control 4.61 ± 0.12%). The diagnosis was trichothiodystrophy.4The “ichthyosis” responded well to Neutroderm with 1% hydrocortisone. Subsequently, the patient showed slow

growth

rate de-spite excellent appetite and adequate caloric intake. After initial improvement, the contractures became worse.The patient started to walk at age 3 years. Mental retardation became apparent; serial psychometrics showed IQ scores between 40 and 50. The skin improved somewhat, but the hair remained sparse and would not grow longer than 2.5 cm. Asthma and allergies to food and medications required treatment. At age 4 years, ad-ductor tenotomy and anterior obturator neurectomy with casting improved the hip contractures. Solar hypersen-sitivity with blister formation after minimal exposure became apparent.

At age 6 years, a reevaluation showed a puny, obviously mentally retarded girl (Fig 4, top). Height and weight were 6 standard deviations less than the mean for age. Microdolichocephaly was evident (head circumference was 46.5 cm, 3 standard deviations less than the mean). Hypotelorism with inner canthal distance of 2.2 cm was present, as well as intermittent right exotropia and hor-izontal nystagmus. The palate was high with constricted maxillary arch and anterior overjet. Teeth were small, but the enamel was not hypoplastic. The skin was dry and shiny, with increased markings on face, neck, flexural folds, hands, and feet (Fig 4, bottom). Brownish-yellow scales were present on the scalp, lower legs, and feet. Scalp hair was sparse, brittle, and without luster. There were hardly any eyebrows. Fingernails showed mild hor-izontal ridging and thickening; trimming was not needed. Hips and knees showed 30#{176}flexion contractures. Ophthalmologic evaluation showed alternating exotropia, myopia, and multiple punctate opacities of fetal and juvenile nuclei of the lenses; the opacities did not impair

the vision. Serum copper was increased, 202 tg/dL. Serum zinc and ceruloplasmin were normal. Skeletal survey showed osteosclerosis reminiscent of osteopetrosis of all bones except the hands and feet; the latter were osteoporotic. Coxa valga were present. Bone age was 5 years 3 months. Scalp biopsy showed mild acanthosis and

Fig 3.

Scalp hair. Top, Alternating bright and dark bands seen with polarized microscopy. Bottom, Cavita-tion of cuticle with amorphous debris (x500).sparse hair follicles with hypoplastic sebaceous glands. The cuticle was markedly fragmented. The outer root sheath showed no abnormality. Electron microscopy showed trichoschisis and marked disorganization of the cuticle. Tripsin Giemsa karyotype of peripheral lympho-cytes was 46,XX.

At-COMMENT

574

PEDIATRICS

Vol. 87 No. 4 April

1991

At different points in time, based on skin biopsies

and phenotype, the diagnoses of this patient were

different

and

the

respective

genetic

counseling

dif-fered. Only the lengthy observation period with

reevaluations of the phenotype, repeat biopsies, and hair analysis enabled an accurate diagnosis.

With improved neonatal care, patients with

se-vere congenital genodermatoses, including

harle-quin and collodion signs could survive. The signs

are nonspecific and indicate heterogeneity. Years

may be necessary for the finite phenotype to

emerge. Thus, etiologic diagnoses for these signs

should be considered with caution. Whenever the

definite diagnosis is established, then the counsel-ing will be accurate and will reflect the relevant recurrence risk for the offspring of the proband and other family members.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The work was supported in part by a grant from State of Florida, Department of Health and Rehabilitative Services, Children’s Medical Services.

I thank Theresa Hudson for the expert secretarial assistance.

BoRIC

G.

KOUSSEFF, MDDivision of Medical Genetics University of South Florida

Tampa, FL

Fig

4. Proposita at 8 years of age. Top, Flexion contrac-tures of knees and hips and decreased subcutaneous tissue. Bottom, Shiny hands with increased cutaneous markings and nail changes.tempts to establish skin fibroblast culture failed. Subse-quently,

growth

increments per year were very small. The “ichthyosis” continued to improve gradually. The number of intercurrent infections decreased. The patient did well in a class for trainable handicapped children. Both par-ents and monozygotic male twin siblings were healthy, of average size for chronologic age, and of normal intelli-gence.REFERENCES

1. Lawlor F. Progress of a harlequin fetus to nonbullous ichth-yosiform erythroderma. Pediatrics. 1988;82:870-873

2. Kousseff BG, Esterly NB. Trichothiodystrophy, IBIDS syn-drome or Tay syndrome? Birth Defects. 1988;24:169-181 3. McKusick VA. Mendelian Inheritance in Man. Catalogs of

Autosomal Dominant, Autosomal Recessive, and X-Linked Phenotypes. 8th ed. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Univer-sity Press; 1988

4. Price VH, Odom RB, Ward WH, Jones FT. Trichothiodys-trophy: sulfur-deficient brittle hair as a marker for a neuroectodermal symptom complex. Arch Dermatol.

1980;1 16:1375-1384

5. Tay CH. Ichthyosiform erythroderma, hair shaft abnormal-ities, and mental and growth retardation. Arch Dermatol. 1971;104:4-13

at Viet Nam:AAP Sponsored on September 2, 2020

www.aappublications.org/news

1991;87;571

Pediatrics

BORIC G. KOUSSEFF

Collodion Baby, Sign of Tay Syndrome

Services

Updated Information &

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/87/4/571

including high resolution figures, can be found at:

Permissions & Licensing

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml

entirety can be found online at:

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or in its

Reprints

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml

1991;87;571

Pediatrics

BORIC G. KOUSSEFF

Collodion Baby, Sign of Tay Syndrome

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/87/4/571

the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is located on

American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 1073-0397.

American Academy of Pediatrics, 345 Park Avenue, Itasca, Illinois, 60143. Copyright © 1991 by the

been published continuously since 1948. Pediatrics is owned, published, and trademarked by the

Pediatrics is the official journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics. A monthly publication, it has

at Viet Nam:AAP Sponsored on September 2, 2020

www.aappublications.org/news