Effects of Sleep Position on Infant Motor Development

Beth Ellen Davis, MD*‡; Rachel Y. Moon, MD§i; Hari C. Sachs, MD¶; and Mary C. Ottolini, MD, MPH§i¶

ABSTRACT. Background. As a result of the American Academy of Pediatrics’ recommendation that healthy in-fants be placed on their side or back for sleep, the per-centage of infants sleeping prone has decreased dramat-ically. With the increase in supine sleeping, pediatricians have questioned if there are differences in the rate of acquisition of early motor milestones between prone and supine sleeping infants.

Methods. To examine this question, we performed a prospective, practice-based study of healthy term infants. Infants were recruited before the age of 2 months. Par-ents were asked to record infant sleep position and awake time spent prone until 6 months of age. A devel-opmental log was used to track milestones from birth until the infant was walking. Age of acquisition of eight motor milestones was determined, and the mean ages of milestone attainment of prone and supine sleepers were compared.

Results. Three hundred fifty-one infants completed the study. Prone sleepers acquired motor milestones at an earlier age than supine sleepers. There was a significant difference in the age of attainment of rolling prone to supine, tripod sitting, creeping, crawling, and pulling to stand. There was no significant difference in age when infants walked.

Conclusions. The pattern of early motor development is affected by sleep position. Prone sleepers attain several motor milestones earlier than supine sleepers. However, all infants achieved all milestones within the accepted normal age range. Pediatricians can use this information to reassure parents. This difference in milestone attain-ment is not a reason to abandon the American Academy of Pediatrics’ sleep position recommendations.Pediatrics 1998;102:1135–1140; sleep position, sudden infant death syndrome, infant development, motor development.

ABBREVIATIONS. AAP, American Academy of Pediatrics; SIDS, sudden infant death syndrome.

I

n 1992, the American Academy of Pediatrics1(AAP) published a recommendation that

“healthy infants, when being put down for sleep, be positioned on their side or back” in an attempt to decrease the incidence of sudden infant death syn-drome (SIDS). Since these recommendations and a subsequent national public education campaign, “Back to Sleep,” the percentage of infants sleeping prone has decreased dramatically from 70% in 1992 to 27% in 1995.2

With the increase in supine sleeping, several pedi-atricians in our community have observed differ-ences in the rate of acquisition of early motor mile-stones between prone and supine sleeping infants. This observation is consistent with data reported from other cultures where supine is the predominant sleep position for infants.3–7Since the sleep position recommendations, there have been no published prospective, longitudinal studies that have quanti-tated the association between sleep position and early motor development. Some recent studies sup-port the observation that supine and prone sleepers may acquire milestones differently. A recent retro-spective chart review demonstrated that sleep posi-tion influences the age when infants roll over.8 In addition, Dewey et al9distributed questionnaires re-garding development to participants in the Avon Longitudinal Study of Pregnancy and Childhood when the infants were 6 and 18 months of age. They found that prone sleepers had higher scores in gross motor, social skills, and overall development at 6 months but not at 18 months.

We conducted a prospective, longitudinal, prac-tice-based study of healthy infants to determine the relationship between sleep position and the age of attainment of motor milestones in the first year of life. Based on our clinical observations, we hypothe-sized that supine sleeping would be associated with later age of attainment of certain motor milestones. Because prone positioning encourages use of upper body strength used in acquisition of many infant motor milestones, it may be that supine sleepers lag in milestone development in the first year because the upper body contributes less to daily movement than for predominantly prone positioned infants.

METHODS

This study was approved by the institutional review boards of Children’s National Medical Center, Holy Cross Hospital, Walter Reed Army Medical Center, and the Uniformed Services Univer-sity of the Health Sciences.

A prospective cohort of healthy infants was recruited at a community hospital nursery and in participating pediatricians’ offices before the age of 1 month. Infants were eligible for

partic-From the *Department of Pediatrics, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland; ‡Department of Pediatrics, Walter Reed Army Medical Center, Washington, DC; §Department of General Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, Children’s National Medical Center, Washington, DC;iDepartment of Pediatrics, George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Washington, DC; and ¶Holy Cross Hospital, Silver Spring, Maryland.

The results from this article were presented in part at the Ambulatory Pediatric Association meeting, Washington DC, May 1997.

The opinions and assertions contained herein represent the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the Department of the Army, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, or the Department of Defense.

Received for publication Jan 8, 1998; accepted Jun 2, 1998.

Reprint requests to (B.E.D.) Department of Pediatrics, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, 4301 Jones Bridge Rd, Bethesda, MD 20814 – 4799.

ipation if they were full term, healthy, and regularly seen by a pediatrician participating in the Children’s Pediatric Research Network. The Children’s Pediatric Research Network consists of 10 suburban private practices, 3 urban pediatric centers, and the Walter Reed Army Medical Center in the Washington, DC, area. The target population was healthy, full-term infants in the United States that represent the recent trends in changing sleep positions, well documented in the literature.2A total sample size of 276 was needed to demonstrate a difference of at least 1 month between the comparison groups. Because of the longitudinal design of the study and the transient nature of the population in the Washing-ton, DC, area, we estimated 25% to 40% drop-out during the 15-month study period. A total of 400 infants comprised this convenience sample. The power of the study was 80%. Infants were excluded from entry into the study for the following reasons: 1) gestational age,37 weeks; 2) orthopedic problems that might affect motor development (eg, torticollis, metatarsus adductus, club foot, developmental dysplasia of the hip); 3) hyperbiliru-binemia requiring hospitalization; 4) any genetic or metabolic abnormalities (eg, hypothyroidism); and 5) asymmetric neurologic examinations. In addition, families who did not have a working telephone for monthly contacts were excluded.

Infants were enrolled from November 1995 to September 1996. Research assistants approached parents being discharged from a full-term nursery two weekdays and one weekend day every week during the study period who would be followed by one of the participating pediatric practices. Approximately 15% of acces-sible parents met exclusion criteria or chose not to enroll, mostly because of time constraints or knowledge of a relocation in the upcoming year. Parents completed an initial questionnaire regard-ing demographic information, birth history, and child care envi-ronment after giving informed consent. They were provided a brochure and advised on enrollment to place their infant on the side or back for sleep according to the AAP recommendation.1

Parents kept a sleep position log, listing the average number of hours per day that their infants spent sleeping and the percentage of time that infants slept in the prone, supine, or side position during the first week of life, and then monthly for the first 6 months of life. Sleep position was defined as the position in which the parents placed the infant for sleep. Using this definition for sleep position has been shown to be reliable until infants begin to choose their own sleep positions at 6 to 7 months of age.10 Fur-thermore, data shows that .95% of younger infants placed in either supine or prone will wake up in the same position, and

.80% of infants placed on the side will wake up in either the side or supine position. Only 0.5% of side-lying infants will awaken prone.11In addition, parents recorded the percentage of time that the infant spent in the prone position while awake. Investigators were blinded to the sleep and awake positions during the study. Parents completed an infant developmental log to track infant milestones. The developmental log included 18 sequential devel-opmental items representing different motor skills, usually occur-ring at a rate of 1 to 2 acquisitions each month. This encouraged consistent parental observation of motor development between major milestone attainments. Standardized questions from the Revised Prescreening Developmental Questionnaire,12,13 a stan-dardized parent-answered questionnaire based on items from the Denver Developmental Screening Test were utilized, with illus-trations of each milestone depicted next to the description for further clarification. The reported test-retest reliability of this type of measure is very high, as is reliability among all socioeconomic groups.14The selected milestones were: lifting chin from surface when prone, lifting head 45 degrees when prone, bringing hands together to midline, rolling prone to supine, grasping item within reach, rolling supine to prone, no head lag when pulled to sitting position, touching feet, sitting supported (tripod), transferring small objects between hands, sitting unsupported, getting to sit-ting position, working for toy, creeping (defined as pulling self along on abdomen), crawling (defined as moving on hands and knees, or hands and feet, with trunk off the ground), pulling to stand, cruising, and walking 10 to 15 steps independently. Parents recorded the age and/or date at which their infant performed the specified milestone. To ensure year-long durability and consis-tency of use, the developmental logs were plastic covered and magnetically mounted.

We ensured current and ongoing documentation of milestone attainment by two different methods: 1) a research assistant tele-phoned the families monthly to record the age of attainment of

milestones and to remind parents to keep the sleep position and development logs current; and 2) independent assessment of health, growth, and development was performed by pediatricians at each well-child check, including a specific physician statement at the infant’s 12-month visit stating that “this infant is healthy and neurologically normal at 12 months of age.” Because the research assistant called in monthly intervals, parental compliance was very good as both predictor and outcome variables remained the same for weeks at a time. Periodic chart review was performed by one of the investigators to verify physician documentation of developmental milestones. The validity of parental report was supported by physician observation of developmental milestones. Approximately 5% of parent reports differed from physician as-sessment as documented in the medical record. In those rare instances, the latter was used for analysis. Infants were followed until they could walk independently for 10 or more steps.

To better compare the effects of prone and supine sleeping on development and to minimize the effect of changing sleep position with age, we identified consistently prone and supine subgroups within the cohort. These sleep positions have been reported to be the most stable (ie, infants placed prone tend to remain prone).15 Infants were categorized as prone sleepers if they were placed in the prone sleep position.70% of sleep time from age 1 month to 5 months. Supine sleepers were defined as those placed in the supine sleep position.70% of sleep time from age 1 month to 5 months. Five months was chosen as the cutoff because we antic-ipated that some infants would begin to change sleep position spontaneously thereafter, diminishing reliability of sleep position based on parental placement. All other infants were reported to be mixed/side sleepers.

Of the 18 developmental tasks on the log, we included the 8 major motor milestones. Based on previous work by Capute et al,16 these major motor milestones are identified as such by a high reported frequency of parental recall and traditionally occurring within a narrow range of variation. For this reason, we selected the 8 major motor milestones for analysis purposes: rolling prone to supine, rolling supine to prone, sitting supported (tripod), sitting unsupported, creeping, crawling, pulling to stand, and walking independently. Additionally, the fine motor milestone of transfer-ring small objects between hands was chosen.

The frequency and distribution of sociodemographic variables were calculated for all participants. We determined the age of acquisition of the 8 major motor milestones for all participants, and we compared the age of acquisition of motor milestones among the subgroups by univariate analysis with the Kruskal-Wallis test. Linear regression analysis was then performed to compare the mean ages of milestone attainment between predom-inantly prone and supine sleepers, while controlling for possible confounders, such as infant size, gender, ethnicity, presence of siblings, and maternal education.

RESULTS Demographic Data

Of the original 400 enrollees, 351 (87%) completed the study. Thirty-seven enrollees were lost to fol-low-up because of disconnected telephones, families not answering multiple telephone calls, family moves, or change to a nonparticipating pediatric practice. The remaining 12 patients developed med-ical conditions after enrollment which precluded fur-ther involvement in the study: congenital adrenal hyperplasia (n51), hypothyroidism (n51), condi-tions necessitating physical therapy referrals (n53), developmental hip dysplasia requiring use of Pavlik harness (n52), metatarsus adductus requiring cast-ing (n 5 2), and nonspecific asymmetric examina-tions requiring neurologic evaluation (n 5 3). No cases of SIDS occurred in this cohort.

American, or other. Forty-two percent (n5146) were first born, 37% (n 5 130) had one sibling, and 21% had two or more siblings. The mean maternal age was 31.365 years, with only 2% of mothers younger than 20 years old. Ninety-three percent (n5 295) of the mothers were married. The mean maternal edu-cational level was 15.362.6 years. Six percent (n5

20) of the mothers had ,12 years of schooling, 71% (n5248) had received 2 to 4 years of college educa-tion, and 23% had.16 years of education. At enroll-ment, 90% of parents anticipated being the primary child care provider for the first year of life.

When the infants were subcategorized according to sleep position, they were similar for maternal age, gender, race/ethnicity, and birth weight. Prone sleepers were more likely to have older siblings (mean, 1.3 vs 0.81 for supine sleepers;P5.007), and their mothers were less likely to be married (P 5

.007). The mothers of prone sleepers had fewer years of education (mean, 14.08 years) than mothers of supine sleepers (mean, 15.39 years; P,.0001).

Sleep Characteristics

Twelve percent (n 5 42) of 1-week-old infants were placed prone for sleep, and 28% (n598) were placed in the supine position. The remaining 60% (n 5 210) of 1-week-old infants were placed in the side-lying position. At 6 months of age, 32% (n 5

112) were being placed prone and 48% (n 5 168) supine for sleep. Side sleepers decreased to 20% (n5

71). Only 44% of infants consistently slept in the same position from 1 to 5 months of age. Sixteen percent of infants (n 5 57) consistently slept in the prone position, and 28% (n 5 97) were consistent supine sleepers. To minimize overlap effects, we used the predominantly prone and predominantly supine sleepers for comparison groups when we looked at effect of sleep position on motor milestone acquisition.

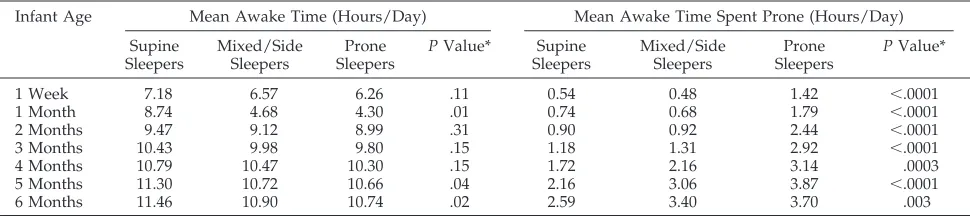

Awake Characteristics (Table 1)

All infants, regardless of sleep position, spent in-creasing amounts of time awake from 1 week of age to 6 months of age. Although the total awake time was similar for all of the infants, there was a signif-icant difference in time spent awake in the prone position. Throughout the first 6 months of life, prone sleepers spent much more time awake in the prone position than the supine or side sleepers. For the first 3 months of life, prone sleepers were awake in the

prone position more than twice the amount of time as the other groups.

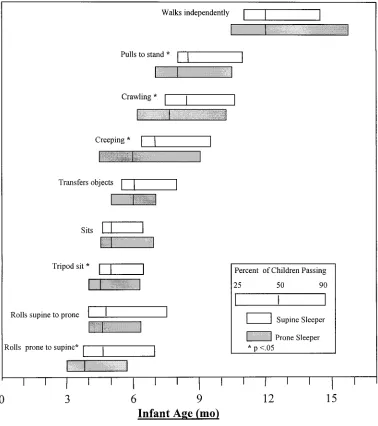

Milestone Attainment (Fig 1 and Table 2)

In general, prone sleepers acquired motor mile-stones at an earlier age than their supine sleeping counterparts. There was a significant difference (P,

.05) in the age of milestone attainment with the fol-lowing milestones: rolling prone to supine, tripod sitting, creeping, crawling, and pulling to stand. Mixed/side sleepers, in general, attained milestones before the supine sleepers and later than the prone sleepers but because this group of sleepers repre-sented significant variability, it was not used as a comparison group. There was no significant differ-ence in the age at which the infants rolled supine to prone, sat unsupported, transferred objects, or walked. Twenty-three percent (n 581) of the study participants never achieved the creeping milestone; 31% (n530) of the supine sleepers and 18% (n510) of the prone sleepers did not creep.

Because there was an impressive difference in the amount of prone playtime seen in the prone versus supine sleepers, we also analyzed the influence of prone playtime in the small group of supine sleepers. Increased prone playtime was significantly associ-ated with earlier attainment of the following mile-stones: tripod sitting, sitting alone, crawling, and pulling to stand (P,.05). However, when maternal education, race, gender, birth weight, and number of older siblings was controlled for, the difference was significant only for the pull to stand milestone (P,.01).

DISCUSSION

The attainment of motor milestones has long been used by pediatricians and parents as an outward indicator of the progress of neurologic development during infancy, although there may be little associa-tion with general intelligence.17 Parental perception of normalcy during the first year of life is heavily influenced by the infant’s progressive attainment of motor milestones. Standardized screening tools used daily by general pediatricians stress developmental milestones that occur within a fixed age range in infants with normal development. Because delayed or skipped milestones are thought to place an infant at risk for abnormal development, identifying factors that influence the normal age range for milestone

TABLE 1. Awake Characteristics of Study Infants (n5351)

Infant Age Mean Awake Time (Hours/Day) Mean Awake Time Spent Prone (Hours/Day)

Supine Sleepers

Mixed/Side Sleepers

Prone Sleepers

PValue* Supine Sleepers

Mixed/Side Sleepers

Prone Sleepers

PValue*

1 Week 7.18 6.57 6.26 .11 0.54 0.48 1.42 ,.0001

1 Month 8.74 4.68 4.30 .01 0.74 0.68 1.79 ,.0001

2 Months 9.47 9.12 8.99 .31 0.90 0.92 2.44 ,.0001

3 Months 10.43 9.98 9.80 .15 1.18 1.31 2.92 ,.0001

4 Months 10.79 10.47 10.30 .15 1.72 2.16 3.14 .0003

5 Months 11.30 10.72 10.66 .04 2.16 3.06 3.87 ,.0001

6 Months 11.46 10.90 10.74 .02 2.59 3.40 3.70 .003

attainment is important. We found that sleep posi-tion significantly impacts early motor development. Traditional age ranges for motor milestone attain-ment in the United States were developed when prone infant sleeping was the norm. As early as 1960, Holt18 qualitatively reported that a small sample of prone sleeping American infants achieved certain

milestones at an earlier age than the supine sleepers. He observed that the prone sleeping American in-fants tended to crawl earlier and were more ad-vanced in their prone motor skills than would be expected of English supine sleeping infants.

Since the 1970s, there have been several reports from cultures in Asia and Europe where supine is the

Fig 1. Motor milestones in prone versus supine sleeping infants. This Figure represents the age range (25% to 90%) for attainment of the specified milestones for supine sleepers (white boxes) and prone sleepers (shaded boxes). The vertical line through the center of each bar represents the age at which 50% of children in that group have demonstrated the identified milestone.

TABLE 2. Mean Age (Months) for Milestone Acquisition

Milestone Prone Sleepers Mixed/Side Sleepers Supine Sleepers PValue* (Linear Regression)†

Rolls prone to supine 3.9361.2 4.4861.8 4.8761.33 .002 (.02) Rolls supine to prone 4.961.3 4.9761.9 5.061.6 .95 Sits supported 4.761.3 5.0261.4 5.1360.9 .003 (.03) Sits unsupported 5.1361.1 5.1761.2 5.1761.0 .80 Transfers object 5.8761.2 5.9966.5 6.2361.1 .11 Creeps 6.0761.9 6.4961.9 7.2361.6 .0002 (.001)

Crawls 7.8362.0 8.4762.1 8.661.7 .003 (.05)

Pulls to stand 8.161.6 8.761.5 8.7761.6 .01 (.04) Walks alone 12.162.0 12.262.0 12.261.7 .4 * RepresentsPvalue for prone sleepers versus supine sleepers.

predominant sleep position, demonstrating later at-tainment of early motor milestones, such as rolling over and sitting up, than would be expected by US norms.3–7 These findings have been sufficiently con-sistent in certain cultures that researchers have adapted and standardized the Denver Developmen-tal Screening Test and the Denver II to fit the cultural norms.3–5,19 The Asian studies specifically refer to supine positioning as a possible explanation for the differences seen in the gross motor milestones.

In this practice-based study, we prospectively fol-lowed a cohort of term, healthy infants from birth through their first year of life, using parental logs to document age of attainment of motor milestones and sleep position. To minimize recall bias, a research assistant called families each month to update the logs and to ensure accurate and current documenta-tion. In addition, the medical records of all study infants were reviewed by one of the investigators to verify parental report and to identify any medical problems that would potentially affect motor devel-opment. We then analyzed the relationship of sleep position and age of attainment of 8 major milestones (rolling to supine, rolling to prone, sitting tripod, sitting unsupported, creeping, crawling, pulling to stand, and walking).

Despite the fact that all parents were counseled on study entry to place their infants supine for sleep, 12% the of 2-week-old infants in our study were being placed prone for sleep, and this number in-creased to 32% by 6 months of age. Although it is unfortunate that some of the parents in this cohort did not follow the current sleep recommendations, this is consistent with recent studies that demon-strate that one-fourth to one-third of parents who are aware of the sleep recommendations continue to place their infants prone for sleep.20,21

In a retrospective study, Jantz et al,8 determined that prone sleepers rolled over at an earlier age than nonprone sleepers but did not find significant differ-ences in other milestones. In this and other recent studies looking at effects of sleep position,8,9,11 an assumption was made that infant sleep position did not change during the time period. Thus, the position that parents placed infants at 1 month of age was the position used for assessment, even at 6 months of age. Our study demonstrated variability in sleep po-sition choice during the course of the first 6 months. Despite 88% of parents placing infants in a nonprone position at 4 weeks of age, only 28% of the infants consistently slept in the supine position from 12 to 20 weeks of age. In 1973, Modlin et al22reported that it was difficult to predict the sleep position in 7-month-old infants by their sleep position at birth, and that only 38% of the infants in their sample had slept in the same position since birth. To ascertain more ac-curately the effects of sleep position, we differenti-ated from the large group of nonprone sleepers (n5

265) a smaller group of supine sleepers (n 597) for comparison with the prone sleeping infants. In the predominantly supine sleepers, we found not only a significant delay in rolling prone to supine, but also significant differences between the groups for tripod sitting, creeping, crawling, and pulling to stand.

The AAP, in its most recent statement regarding infant sleep position, recommended that infants spend some time in the prone position while awake and observed.2In our survey, however, we discov-ered that many parents avoided placing their infants prone, even when the children were awake, because they were fearful of the possibility of SIDS. This is consistent with a previous report, in which 26% of parents never placed their infants prone for play.23 We also noticed that many of the supine sleepers did not want to be placed prone while awake. When we asked parents to determine how much time their infant spent prone while awake, many parents pref-aced their response with “My baby doesn’t like his/ her tummy!” In our study, the prone sleepers spent significantly more time prone while awake. The amount of prone playtime may be a contributing factor to the effect of supine sleeping on motor devel-opment. At the least, it seems to amplify the effect of supine sleeping, and it may be the primary factor that influences motor development. In our small sample of supine sleepers, we found that increased prone play-time did result in earlier milestone attainment. How-ever, further, larger scale studies are indicated to de-termine if increased prone playtime does indeed accelerate motor development in supine sleepers.

As this study was dependent on parental report-ing, the validity of these results is limited by the accuracy of the parents’ responses. Although it is acknowledged that parents may have been unwilling to admit to actual sleep positions, this would have had the effect of minimizing the differences that we found in milestone acquisition. To control for poten-tial differences in sociodemographic characteristics between prone and supine sleepers which we found and which have been reported by others,20,24we con-ducted a logistic regression analysis and found that sleep position retained a significant effect on early infant motor development. In addition, we at-tempted to minimize the bias introduced by parental report by also having the physicians assess the in-fants’ developmental progress at well-child visits. When physician assessment was discrepant with pa-rental report, the former was used in the analysis.

Although supine sleepers attained some motor milestones as much as 1 month later than the prone sleepers, it is important to emphasize that they still attained these milestones within the accepted time range for normal. In fact, even the supine sleepers achieved milestones at ages faster than traditional means. This may be the result of increased parental vigilance and awareness of motor milestone attain-ment from participating in the study. It is yet unclear if there are any long-term developmental effects from sleep positioning. Because there does not seem to be a difference in attainment of walking skills or of some of the 18-month-old milestones,9this difference in milestone attainment may be transient. However, further studies are indicated as this generation of predominantly supine sleepers becomes older.

As more of the US population adopts supine infant sleep positioning, pediatricians need to be able to provide parental reassurance that the differences in milestone acquisition are not developmental delays, but rather are still within well-accepted normal ranges for development. It must be emphasized that this difference in developmental acquisition is not a reason for parents or pediatricians to abandon the AAP sleep recommendations. Pediatricians also need to actively incorporate the encouragement of prone play at the 2- and 4-month well-child visits to max-imize development of upper-body strength.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank the following pediatricians in the Children’s Pediatric Research Network: Valorie Anlage, MD; Louis Bland, MD; Steven Brown, MD; Angela Gadsby, MD; James Kalliongis, MD; Albert Modlin, MD; My Huong Nguyen, MD; Edward Padow, MD; Ann Werner, MD; Pamela Parker, MD; Ellen Fields, MD; Nancy Cohen, MD; Denise DeConcini, MD; Carol Miller, MD; Toby Ascherman, MD; Daniel Shapiro, MD; Jeffrey Bernstein, MD; Linda Paxton, MD; Robin Witkin, MD; Marvin Tabb, MD; Eugene Sussman, MD; Elizabeth Lubas, MD; Bonnie Zetlin, MD; Timothy Patterson, MD; Earlene Jordan, MD; Linda Williams, MD; Ivy Masserman, MD; Herbert Berkowitz, MD; James Burgin, MD; Melvin Feldman, MD; Dan Glaser, MD; Alan Gober, MD; Leonard Lefkowitz, MD; John Lowe, MD; Nancy Tang, MD; Stuart Weich, MD; Cheryl Dias, MD; Richard Hollander, MD; Larry Cohen, MD; Blair Eig, MD; Robin Madden, MD; Ray Coleman, MD; Allan Coleman, MD; Viola Cheng, MD; Rosella Castro, MD; Carla Sguigna, MD; Nancy Zimmerman, PNP; and Patti Murakami, PNP. We thank Laurette Cressler and Naomi Bloom Gershon for data collection, and Bruce Sprague and Kantilal Patel, PhD, for statistical analysis. We also express appre-ciation to the families who participated in the study.

REFERENCES

1. American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on Infant Positioning and SIDS. Positioning and SIDS.Pediatrics.1992;89:1120 –1126

2. American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on Infant Positioning and

SIDS. Positioning and sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS): update.

Pediatrics.1996;98:1216 –1218

3. Ueda R. Standardization of the Denver Developmental Screening Test of Tokyo children.Dev Med Child Neurol.1978;20:647– 656

4. Song J, Zhu Y, Gu X. Restandardization of the Denver Developmental Screening Test for Shanghai children.Chin Med J. (Engl). 1982;6:95 5. Lim HC, Chan T, Yoong T. Standardization and adaptation of the

Denver Developmental Screening Test (DDST) and Denver II for use in Singapore children.Singapore Med J.1994;35:156 –160

6. Fung KP, Lau SP. Denver developmental screening test: cultural vari-ables. (Letter).J Pediatr.1985;106:343

7. Bryant GM, Davies KJ, Newcombe RG. The Denver Developmental Screening Test. Achievement of test items in the first year of life by Denver and Cardiff infants.Dev Med Child Neurol.1974;16:475– 484 8. Jantz JW, Blosser CD, Fruechting LA. A motor milestone change noted

with a change in sleep position.Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med.1997;151: 565–568

9. Dewey C, Fleming P, Golding J, ALSPAC Study Team. Does the supine sleeping position have any adverse effects on the child? II. Development in the first 18 months. Pediatrics 1998;101:(1). URL: http://www. pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/101/1/e5

10. Willinger M, Hoffman H, Scheidt PC, et al. Infant sleep position and SIDS in the United States. (Abstract).Am J Dis Child.1993;147:460 11. Hunt L, Fleming P, Golding J, ALSPAC Study Team. Does the supine

sleeping position have any adverse effects on the child? I. Health in the first six months.Pediatrics.1997;100(1). URL: http://www.pediatrics. org/cgi/content/full/100/1/e11

12. Frankenburg W, Fandal A, Thornton S. Revision of Denver Prescreen-ing Developmental Questionnaire.J Pediatr.1987;110:653– 657 13. Frankenburg W, Camp B, Van Netta P. Validity of the Denver

Devel-opmental Screening Test.Child Dev.1971;42:476 – 482

14. Rosenbaum M, Chua-Lim C, Wilhite J, Mankad V. Applicability of the Denver Prescreening Developmental Questionnaire in a low-income population.Pediatrics.1983;71:359 –363

15. Kemp JS, Livne M, White DK, Arfken CL. Softness and potential to cause rebreathing: differences in bedding used by infants at high and low risk for sudden infant death syndrome.J Pediatr. 1998;132:234 –239 16. Capute A, Shapiro B, Palmer F, Ross A, Wachtel R. Normal gross motor development: the influences of race, sex and socio-economic status.Dev Med Child Neurol.1985;27:635– 643

17. Capute A, Accardo P.Developmental Disabilities in Infancy and Childhood. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co; 1991

18. Holt K. Early motor development: posturally induced variations.J Pe-diatr.1960;57:571–575

19. Bryant GM, Davies KJ, Newcombe RG. Standardization of the Denver Developmental Screening Test for Cardiff children.Dev Med Child Neu-rol. 1979;21:353–364

20. Taylor JA, Davis RL. Risk factors for the infant prone sleep position.

Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med.1996;150:834 – 837

21. Rainey D, Lawless M. Infant positioning and SIDS: acceptance of the nonprone position among clinic mothers.Clin Pediatr.1994;33:322–324 22. Modlin J, Hawker A, Costello A. An investigation into the effect of sleeping position on some aspects of early development.Dev Med Child Neurol.1973;15:287–292

23. Mildred J, Beard K, Dallwitz A, Unwin J. Play position is influenced by knowledge of SIDS sleep position recommendations.J Paediatr Child Health.1995;31:499 –502

DOI: 10.1542/peds.102.5.1135

1998;102;1135

Pediatrics

Beth Ellen Davis, Rachel Y. Moon, Hari C. Sachs and Mary C. Ottolini

Effects of Sleep Position on Infant Motor Development

Services

Updated Information &

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/102/5/1135

including high resolution figures, can be found at:

References

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/102/5/1135#BIBL

This article cites 21 articles, 3 of which you can access for free at:

Subspecialty Collections

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/for_your_benefit

For Your Benefit following collection(s):

This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

Permissions & Licensing

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml

in its entirety can be found online at:

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

Reprints

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml

DOI: 10.1542/peds.102.5.1135

1998;102;1135

Pediatrics

Beth Ellen Davis, Rachel Y. Moon, Hari C. Sachs and Mary C. Ottolini

Effects of Sleep Position on Infant Motor Development

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/102/5/1135

located on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 1073-0397.