Representations of the grave in nineteenth-century English poetry:

A selected commentary.

Ph.D. Thesis submitted for examination in October 1997

by

Samantha Matthews.

Department of English, University College London.

All rights reserved

INFORMATION TO ALL USERS

The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted.

In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed,

a note will indicate the deletion.

uest.

ProQuest U642978

Published by ProQuest LLC(2015). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author.

All rights reserved.

This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC.

ProQuest LLC

789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346

Representations of the grave In nineteenth-century English poetry: A selected commentary.

The Victorian ‘celebration of death’ is most evident to us now in large suburban cemeteries with their ostentatious monuments; yet they show only one aspect of nineteenth- century death and burial, concealing the Romantic opposition to material memorialisation which runs through the century’s poetry. In this project I present readings of grave-poetry set in the socio-historical context, and explore moments of self-reflexive anxiety about personal and literary mortality, when poets contemplate their own graves, their children’s graves, and the graves of precursor poets.

Most of the poets considered are not canonical (in the sense of being widely read or taught); they include William Allingham, Alexander Anderson, Edwin Amold, Alfred Austin, William Edmondstoune Aytoun, Edmund Gosse, Cecil Frances Humphreys, Letitia Landon, Eugene Lee-Hamilton, David Macbeth Moir, Francis Tumer Palgrave, John Critchley Prince, Bryan Waller Procter, Hardwick Drummond Rawnsley, Douglas B. W. Sladen, Robert Southey, John Thelwall, Martin F. Tupper and William Watson. I respond to the critical challenges presented by ‘less read’ poems by employing an ‘eclectic hermeneutics’ which includes a family- orientated revision of Harold Bloom’s anxiety of influence’ thesis.

Chapter 1 examines poems which reflect the social history of burial in the nineteenth century, covering issues such as the country churchyard aesthetic, body-snatching, city churchyards, suburban cemeteries and cremation. Chapter 2 is concemed with the parent- poet’s representation of children’s graves, specifically fathers and their anxiety about disruption of the generational order. Chapter 3 discusses representations of the graves of Keats and Shelley in the Protestant Cemetery, Rome, where for example I read Adonais in the context of premature death and a Victorian myth of poetic brotherhood. Chapter 4 examines poems about the graves of five significant poets (Hemans, Wordsworth, the Brownings and Tennyson), looking at the the influence of gender on tribute verse and the Romantic rejection and Victorian recuperation of Poets’ Comer and the Laureateship.

The grave is a rich and varied trope, found in elegies, eulogies, ballads, devotional and consolatory verse, poems of social criticism, suicide, marginality and political injustice. The poems I discuss were derived from a survey of the period 1800-1900 on the Chadwyck-Healey

Volume I: The Thesis and Reference Lists. 2 Abstract.

4 List of Illustrations. 5 Acknowledgements. 6 Notes.

7 Abbreviations.

9 Introduction: Sepulture and the great body of English Poetry.

24 Chapter 1 : The country churchyard aesthetic and social history of death.

70 Chapter 2: Paternal tears and little graves: fathers’ responses to their children’s deaths. 116 Chapter 3: Keats, Shelley, and the Protestant Cemetery, Rome.

160 Chapter 4: Pilgrimages to poets’ graves. 163 Felicia Hemans.

174 William Wordsworth.

188 Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Robert Browning. 200 Alfred Tennyson.

213 Conclusion: Great poets and small poets.

222 Texts not included in the Chadwyck-Healey English Poetry Full-Text Database, Software Version 4.0 (1995).

235 Bibliography 1 : Poets.

308 Bibliography 2: Secondary works consulted.

Volume II: Appendices and Supporting Documents.

2 Contents. 12 Notes.

Appendix 1: Survey of incidences of search terms grave,’ graves,’ tomb,’ tombs’ and burial’ in English poetry 1800-1900.

13 1800-1835. 106 1835-1870. 209 1870-1900.

Appendix 2: Account of tropes and poem types in which graves appear in English poetry 1800-1900.

Unsourced photographs are the author’s own.

Figure Page

1 Francis Chantrey, Monument to David Pike Watts. 1817-26. Marble, life-size. 20 Ham, Staffordshire (Janson 1985, p.76).

2 Bury St. Edmunds Cathedral churchyard, Suffolk, 1996. 26 3 Typical body stones in the churchyard of the Ancient Mother of Churches,

Stoke Newington, London, 1996.

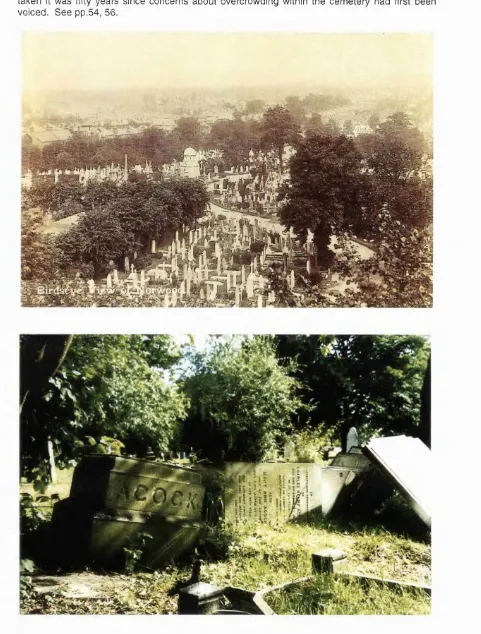

4 South Metropolitan Cemetery, West Nonfood, c.1907 (Friends of West 55 Norwood Cemetery 1994).

5 Collapsed Acock family monument, Camberwell Old Cemetery, Forest Hill, 1995.

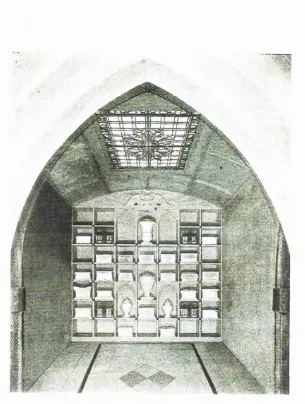

6 Ilford Crematorium, interior of Columbarium (Jones and Noble 1931, p.50). 63 7 Facsimile of three posters issued by the Cremation Society [‘Adopt Cremation," 66

‘Cremation prevents pollution,’ ‘Purification by Fire Pollution by Burial’] (Jones and Noble 1931, p. 139).

8 American amateur portrait of deceased child on bed between grieving parents. 72 c. 1920 (Ruby 1994, p.56).

9 Late-Victorian amateur post-mortem portrait of an infant (Linkman 1993, p.121). 97 10 Card photograph of an unknown deceased child in a buggy, Indiana, U.S.

c. 1890s (Ruby 1993, p.55).

11 Thomas Banks, Tomb of Penelope Boothby. 1793. Marble, life-size. 105 Ashbourne, Derbyshire (Janson 1985, p.21).

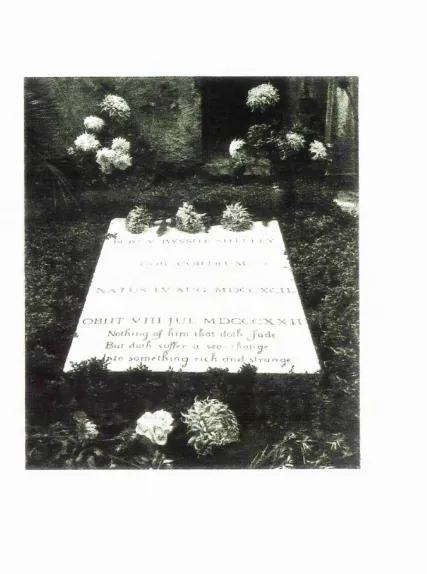

12 The grave of Percy Bysshe Shelley (Beck-Friis 1956, p.27). 120 13 The graves of John Keats and Joseph Severn in the Protestant Cemetery, 142

Rome, with the Pyramid of Caius Cestius in the background (Beck-Friis 1956, p.16).

14 Edward Onslow Ford, Shelley Memorial. Completed c.1890. Marble and 155 bronze, life-size. University College, Oxford (Janson 1985, p.243).

15a St. Oswald’s Church, Grasmere (Middleton 1910, p.11). 177 15b The Wordsworth family plot, St. Oswald’s churchyard, Grasmere (Middleton ”

1910, p.39).

16 Frederic, Lord Leighton. Tomb of Elizabeth Barrett Browning in the Protestant 190 Cemetery, Florence (Jones, Newall et al. 1996, p.82).

17 ‘The late Robert Browning - the Funeral Ceremony in Westminster Abbey,’ 196 January 1890 (Flood-Jones).

18 ‘The Last Look: A Sketch at the Funeral of Lord Tennyson at Westminster 206 Abbey yesterday,’ October 1892 (Flood-Jones).

This project would not have been done without the support of a British Academy Three- year Studentship awarded in 1993-6, and a one-year teaching fellowship in 1996-7 in the English Department at University College London. I would also like to express my gratitude to the British Library, especially the North Library staff, and the University of London Library, particularly the Middlesex South Library staff for their patience while I monopolised English Poetry.

I wish to thank Chadwyck-Healey Ltd. for permission to reproduce materials from

English Poetry: A Bibliography of The English Poetry Full-Text Database (1995) and the Chadwyck-Healey English Poetry Full-Text Database, Software Version 4.0 (1995); also Louisiana State University Press for permission to reproduce Christina Rossetti’s ‘Death’ and Penguin Books for permission to reproduce Emily Bronte’s ‘The Prisoner (A Fragment).’

Other people and organisations for whose help I am grateful include: the Friends of Nunhead Cemetery, with whom I gained first-hand experience of the history and contemporary management of a great Victorian cemetery; Dawn at the Friends of Highgate Cemetery, who sought out the grave of William Canton’s daughter, Winifred; Miss Reynolds in the Westminster Abbey Library who helped locate images of Poets’ Corner and the funerals of Browning and Tennyson; Frank Lalor who visited and documented Felicia Hemans’s memorial plaque in St. Anne’s Church, Dawson Street, Dublin; the organisers of the Romantic Grave symposium held on 23 March 1996 in conjunction with the Dulwich Picture Gallery exhibition Soane and Death,

and Roger Bowdler and Christopher Woodward who organised several sepulchral study days in 1996-7.

I would like to thank my friends and correspondents for their tolerance and conversation, particularly Maxim Anderson, Claire Lemmon and Meike Marten. Kathrina Glitre, Peter Swaab and David Trotter read parts of the thesis and made helpful suggestions. Danny Karlin read the thesis in various permutations and responded with valuable professional advice and friendship.

This project is based almost entirely on poems that are not well known. The scale of the appended material is such that I have reluctantly decided not to give the texts of these poems; however, the majority of poems discussed appear on the Chadwyck-Healey English Poetry Full-Text Database, and are therefore accessible at present through major libraries and university computer networks. Texts not on English Poetry appear in a short appendix at the end of the main text of the thesis (volume I, pp.222-34), or exceptionally in the ‘Anthology’ (volume II, pp.328-452).

All poems discussed were examined in original volumes at the British Library, but most primary texts are referenced to their line-numbering in English Poetry because of its greater accessibility. I allude to several works made up of shorter lyrics, and these are referred to by section number and line number within that section (e.g., Eugene Lee-Hamilton’s MImma Bella,

Tennyson’s In Memorlam, and John Thelwall’s ‘Parental Tears’).

Sources are identified in short form by the author’s surname, date of publication and volume, page or line numbers as appropriate. Details of these sources are given in two reference lists: one of poetry (Biblioaraohv 1 : Poets) and another of secondary and miscellaneous materials (Bibliography 2: Secondary works consulted). Bibliographic details of the 450 poets surveyed on the Chadwyck-Healey English Poetry Full-Text Database, Software Version 4.0 (1995) are reproduced from English Poetry: A Bibliography of The English Poetry Full-Text Database (1995). The context should indicate whether I am discussing poetry or prose, but in the few cases of ambiguity (such as consolation anthologies) the reference appears in both lists. Where several titles by a single author are used, they are listed alphabetically. Bibliography 1 gives full details; Bibliography 2 gives short details only.

English Poetry. Chadwyck-Healey English Poetry Fuil-Text Database: Software Version 4.0 (1995).

Fiood-Jones'. Samuel Flood-Jones Newscuttings Collection, Westminster Abbey Library.

NCBEL: New Cambridge Bibliography of English Literature. Edited by George Watson. Volume 3

1800-1900 (Cambridge 1969).

Lillian Parker, Dickie Hucks.

Dedicated to

The great body of English Poetry, ... it has been remarked is more rich on the subject of sepulture than the poetry of any other nation.

Edwin Chadwick, A Supplementary Report... into the practice of interment in towns, 1843.^

He must be a churl indeed, who would refuse two feet of earth to even a doubtful fame. ... Do not fear to remember too much; only be upon your guard not to forget any thing that is worthy to be remembered.

William Godwin, ‘Essay on Sepulchres,’ 1809.^

When I first began using the Chadwyck-Healey English Poetry Fuii-Text Database (hereafter

English Poetry) in 1994, my purpose was to sketch a background to famous instances of a particular image in nineteenth-century poetry: the grave. I knew about the graves in The Excursion, in Memoriam and the 'Ode on the Death of the Duke of Wellington’; I knew Arnold’s ‘Stanzas In Memory of the Author of Obermann,’ ‘Haworth Churchyard’ and ‘Heine’s Grave,’ Browning’s ‘The Bishop Orders His Tomb at St Praxed’s Church,’ Swinburne’s ‘Ave Atque Vale,’ and Dickinson and Whitman’s responses to death. Given my interest in the social history of death and changes in burial practice during the century, it was important to know whether these incidences in well-known texts were typical or idiosyncratic, whether they reflected social change or the poet’s subjectivity. Searching English Poetry for key words such as ‘grave,’ ‘graveyard,’ ‘churchyard’ or ‘sepulchre,’ I was overwhelmed not only by the quantity of uses, but the diversity of genre, tone and literary sophistication. Of the 1,250 poets represented in English Poetry, 450 were active in 1800-1900, and there are around 80,000 poems from that period on the database. On an initial search of the words ‘grave’ and ‘tomb’ alone the database generated up to 9,000 poems (discounting irrelevances).® There were literal epitaphs and grave inscriptions of a few lines, and metaphorical graves in apocalyptic multi-part epics. There were lengthy ballads which used the grave to originate or terminate storytelling, and there were limited conceits. There were sensational love affairs in tombs, beautiful corpses as the object of sexual desire, and accounts where the grave was transcended by sentiment and memory.

The range and mass of this material did not simply reinforce the received wisdom that the Romantic and Victorian poets were profoundly interested in death and its rituals;^ it suggested that here was a significant body of poets and texts poised at a moment of resurrection. By noting a certain poem as interesting or rejecting it as banal and unreadable, I could revive a poet or relegate him or her to pre-English Poetry obscurity; the immediate problem was what makes a poem ‘worthy to be remembered.’ The metaphorising of this process as salvation or damnation was prompted by the topos I was researching; but it also

'Chadwick 1843, p. 131. ^Godwin 1993, pp.27-8.

The database generated more than a thousand examples of the homograph ‘grave’ meaning serious or weighty, or the tag ‘grave or gay.’

expressed for me in a newly dramatic form the difficulties of canonicity. Unlike the subjective critic, English Poetry is incapabie of distinguishing the aesthetic merits of a text; mobilised by the search for a single word or phrase, it indiscriminately generates poems by (for instance) Coventry Patmore, Joseph Noei Raton and Emily Pfeiffer. This apparent iack of discrimination comprises the tool’s weakness and strength. It gives the interested reader a quantity of material in a democratic and equalising environment, without prescriptions and value-judgements, but also without a sense of context. It lists devotional writers with freethinkers, working-class protest-poets with literary dilettantes, ‘poetesses’ with poiiticised women poets. Poet Laureates with virtual unknowns. In this relatively uncritical environment, many reader-assumptions and agendas are usefully bypassed; however, the concrete historical contexts of production and reception are one group of factors among many which may be obscured.

The discovery of all these grave-poems was novel and stimulating, and made me feel like a pioneer in new country; but simuitaneously it was daunting and even threatening. For as I began reading these thousands of poems tangentially relevant to my project, it became apparent that I was involved in a selective process which restored many of the critical judgements the database had discarded. To adapt Godwin’s warning, my fear that there was too much to remember was making me begrudge even a brief revivai to these poets of ‘doubtful fame.’ My agenda was pragmatic: to reduce the number of poems, to find texts which compiemented or opposed the canonical works I already knew, and to identify poems which might be susceptible to critical exegesis. Over the weeks I worked through these poems, pouncing on unusual or striking representations, and discarding the repetitive or irksome, my critical assessments - and my project - fundamentally changed. I became fascinated by these unfamiliar poems and whether they would be doomed to obscure, marginal lives as documentary fiiler or footnotes, or whether they could be redeemed critically. Many of these poets employ a communal Romantic idiom and share assumptions about the priority of nature, feeling and the famiiy. The stylistic banality, repetition and adherence to convention which I had dismissed initially, acquired an independent significance. The canonicai poets who prompted me to make the original search were repositioned, and appear in the finished thesis as significant points of reference and concern to these less known poets, but rarely as active poetic practitioners.

In order to read these poems it was necessary, in Kathleen Hickok’s restatement of Nancy K. Miller’s formulation about noncanonical women’s poetry, to ‘attempt to encounter each text “as if it had never been read, as if for the first time”,’ and to exercise ‘critical and evaluative forbearance’ (Hickok 1995, pp.13, 21). My experience suggests that in practice this edenic condition of reading remains an attempt and an ideal, particularly when so many texts are involved; but the mood of openness and receptivity it indicates, is I think appropriate to the initial reading of all poets, although considerations of gender and status may become significant later in the interpretative process. English Poetry makes a vast quantity of material accessible to the general reader, but criticism is still working to make it readable.

poets/ However some recent critics in this field are interrogating the effects of certain strategies, and drawing conclusions relevant to less-read poetry in general. Hickok warns against ‘the temptation to find the text we seek’ (p.21); that is, to formulate a theory around (for instance) the woman poet’s paradoxical exclusion from and imprisonment within culture, and to find poems which illustrate that theory. Hickok also cites Isobel Armstrong’s doubt that a criticism focused on incidences of female protest in poetry ‘retrieves the protest, but not the poem’ (Armstrong 1993, p.319). I would suggest that these two views, expressed in the 1995

Victorian Poetry women’s poetry special issue, have a broader relevance to the problems of value which I encountered in searching the nineteenth-century materials on English Poetry.

After the theoretical rigidity of much recent criticism, Hickok’s recommendations appear subversive in their very simplicity. She suggests prioritising the text, and finding the critical strategies which best serve it:

I want to propose an eclectic and responsive approach that allows the potential pleasures of the reader to materialize before the operations of the critic overwhelm them .... I want to privilege the unfamiliar text itself, at least initially, rather than the critical responses to it, and I want to defer hypotheses and generalizations until the text has been allowed to breathe, (p.21)

Potentially this non-judgemental position releases the poem from some of the burdens of critical expectation, and consciously gives it breathing space. So determined are we as critics to define what is good or bad about a poem, that less-read poems are liable to be scanned and discarded. Reading these grave-poems, it was tempting to dismiss the Romantic idiom and conventional tropes which were used until late in the century; however doing so would have obscured the important scene of the country churchyard, made it difficult to evaluate idiosyncratic transformations, and ignored the fact that many poets chose to speak in this communal voice. This is not to deny that some texts respond much more productively than others, or that some poems deserve obscurity and will not be revived by any amount of sympathetic reading and breathing space. In any mass of material, quality and interest vary widely; but poets and poems which have been forgotten, suppressed, misrepresented or seriously affected by the circumstances of their production, respond to critical strategies which are flexible, receptive and constructive.

This condition of critical open-mindedness is of course only a beginning. What the critic desires are texts which can be written about and from which a story can be made, and I suggest that ingenious theoretical models are usually poorly adapted to making the most of less-known poems. These poems resist basic tenets such as aesthetic sophistication, or postmodern emphases on disrupted discourses and subversion, and so the critic must seek different strategies. Hickok’s ‘eclectic hermeneutics’ (p.21) of women’s poetry elects nonaesthetic criteria not necessarily predicated on a discourse of social or cultural oppression, and evokes the values cf new historicism and cultural studies. It embraces a variety of approaches including biography, social and historical context, reception, genre, literary history and tradition, affect, technique and style. Hickok accepts that her criteria are subjective and provisional, and offers

them as a starting point for discussion and comparison since ‘No aspect of critical inquiry should be rejected, and, conversely, none by itself will be sufficient to explore these many-faceted poems fully' (p.25).

These strategies, suggesting a radical revision of new critical values under feminist and new historical pressure, retain their significance as a working model when applied to the diverse body of poetry written by both sexes in the nineteenth century. The extant traditions were less troubled and politicised for male than for female poets, but I think that we are less likely to misjudge traditions, poems and individual cases by considering the range of poetry as a whole, than by depending upon one gendered tradition or critical model.

As these interpretative strategies are provisional and pragmatic, based on what "works' for the text, the materials provided by English Poetry are not authoritative or unproblematic. Poets covered by the database are represented fairly comprehensively; but the use of the New Cambridge Bibiiography of English Literature 1600-1900 (1969) (hereafter NCBEL) as a primary source inevitably excludes many marginal figures revived and discovered in the last thirty years, particularly women, minorities, anonymous, provincial and periodical poets, despite some efforts to supplement underrepresented areas.^ Equally, the generic definition of some authors as novelists or practitioners of minor fiction has led to anomalies, such as the omission of the poetry of Anne and Charlotte Bronte, George Eliot and George Meredith. Coupled with a necessarily pragmatic editorial policy which generally presents a single version of each poem, and the uneasy combination of a few scrupulous modern editions with a vast majority of unpredictable nineteenth-century first editions and Collected Poems, English Poetry is less comprehensive than it first appears. However, these provisos and cautions are hardly serious obstacles to the medium's experimental possibilities; the database has been improved considerably since its first two disk release, and further revisions are scheduled.^

What I offer here is one possible response to these challenges. In Appendix 1, I present the results of my searches of the period 1800-1900 on the Chadwyck-Healey English Poetry Full-Text Database: Software Version 4.0 (1995b) using the keywords ‘grave,' ‘graves,' ‘tomb,' ‘tombs' and ‘burial'; where the words ‘cemetery' or ‘churchyard' appeared with my search terms, these incidences were also recorded. In an attempt to indicate how English Poetrÿs agenda could be broadened, I supplemented these findings with manual volume searches.® I retained

'Daniel Karlin notes the perpetuation of NCBELs male bias in English Poetry {English Poetry

1995a, vi).

^David E. Latané notes that of the fifty poets included in Leighton and Reynolds’s Victorian Women Poets (1995), twenty-three are not on the database, and that many of the male poets in Ricks's New Oxford book of Victorian verse (1987) do not appear either (Latané 1995, pp.1-9). Chadwyck-Healey plan a detailed updating of English Poetry during development of

Literature On-Line {LION), its conglomeration of literary databases on the World Wide Web. ^1 emphasise that this was to enrich the survey results, and not an attempt at comprehensive

coverage. To find supplementary sources I used the British Library Catalogue, Fredeman and Nadel's Dictionary of Literary Biography volumes 32 and 35 {Victorian Poets Before

7850 [1984] and Victorian Poets After 7850 [1985]), Greenfield's Dictionary of Literary Biography volumes 93 and 96 {British flomantic Poets, 1789-1832 First Series [1990] and

NCBEUs division of the nineteenth century into three periods: 1800-1835; 1835-1870; 1870- 1900. Debatable as these divisions are, they help to maintain texts’ links with their historical context, and facilitate observations about broad cultural shifts in the use of certain tropes. Each incidence of a keyword was checked for relevance, keyed in and grouped under poet name, poem title and line number according to English Poetry, or referenced to a page number where texts were taken from other sources. Thus it is possible to make a rough evaluation of an individual poet or group’s response to the materiality of death by the number of poems in which the grave image occurs, and the depth of that examination by how frequently the grave is named in each text.

Inevitably my restricted search terms exclude poems which refer to the grave obliquely or euphemistically as a ‘sepulchre,’ ‘last home,’ ‘last rest,’ ‘long home,’ ‘vault,’ ‘cell,’ or by its marker (the ‘memorial’ or ‘monument’). As users of English Poetry know, successful searching depends upon the careful selection of key words. My search terms are biased towards materiality, and contain the assumption that the grave will be referred to directly; consequently my study emphasises the poet’s engagement with real and rhetorical burial-sites. Cross checking combined searches indicates that relatively seldom is the grave described without one of the search terms.^ However, the grave can be the real focus or subject of a poem in which it is not explicitly described, and one important line of further inquiry suggested by my study is this rhetorical technique of sensitive or tactful evasion of the g rave.^

This survey suggests that use of the five keywords was consistent and widespread in poetry up to 1870: there are 9,788 incidences in the early period, rising to 10,484 in the mid century. There is a significant decline in the late period to 6,806, but since the total number of poets included is smaller, the actual decline is less dramatic than at first appears.® It reflects a move away from representing death and the grave in material terms, towards a more euphemistic and metaphorical approach, with an emphasis on forgetting rather than remembering death. With the works of another eighty poets, included to fill obvious gaps and to broaden the impression of the century’s poetry, more than 12,200 poems appear in the survey.'* While it is difficult to calculate the density of usage of these terms, because English Poetry

counts epigraphs of a few lines and epics of several hundred pages both as single poems, when the number of incidences in any one poet’s works was averaged with the total number of their

’ Browning’s ‘Bad Dreams. IV’ is a good example of a grave-poem missed by my search: It happened thus: my slab, though new.

Was getting weather-stained, — beside, Herbage, balm, peppermint o’ergrew

Letter and letter: till you tried

Somewhat, the Name was scarce descried. (Browning 1888-94, v.XVII, p.26,1-5)

^For example see my discussion of parents’ attitudes to their children’s graves on pp.73, 89-99.

^English Poef/y includes 132 poets in the early period, 134 in the mid-century, and only 109 in the late period.

poems, the result usually confirmed my reading experience of which poets were most concerned with the grave image/

In Appendix 2, I present a brief descriptive account of genres and tropes in which the grave is significant, and a short anthology of poems as a guide to further research. Categories are illustrated by examples which can usually be found in Appendix 1, and are referenced back to Bibliography 1. While I have tried to reconcile classifications with traditional generic categories, my policy of allowing the texts to suggest tropes and themes, rather than seeking predetermined motifs, has resulted in a few idiosyncratic groupings. This subjective analysis was also created by the variety of genres in which the grave figures. Single poems might often be allocated to any one of five or six different categories, and prioritising one context above another is neither straightforward nor accurate. We are familiar with aspects of thanatological literary tradition, such as the domestic or public elegy, eulogy, pastoral, memento mori and epitaph; while I discuss important poems in the elegy tradition (such as Adonais and In Memoriam), and consider my approach corresponds to a materialist reading of elegy, many grave-poems are not elegies in any strict sense; the ‘grave’ is a subject or trope which is not widely recognised by literary history.

The classifications identified range from personal and domestic elegies for children, parents, friends, spouses and pets, to public odes for royalty, statesmen, and military heroes. There are lyrics where the speaker (or poet) chooses his or her own grave, and poems of literary pilgrimage where aftercoming poets position themselves in relation to precursors at the grave. There are genre poems on the graves of marginal social groups, such as the poor, insane, isolated or anonymous, which often employ a rhetoric of explicit social criticism. The grave is also used for satirical and comic ends. Poems about the graves of other marginal figures such as exiles and emigrants share significant characteristics with those about sea and desert graves or suicides' burial. Aside from elegies about women which define them by familial relationship, one tradition focuses explicitly on the graves of beautiful young women, and these often resemble Gothic representations of aestheticised or eroticised graves where the living lover pines for the dead, or the dead person actually speaks from the tomb. Devotional poems range from sonnets meditating on a scriptural text, to biblical epics. There are many meditations on mortality, usually located in a burial-place and strongly influenced by Gray’s ‘An Elegy written in

'Typically the average of these two figures was 0.2-0.4; I designated averages of 0.8 or above as unusually high. In the early period the grave was referred to most by: Caroline Bowles, Henry Boyd, Sir Samuel Brydges, Byron, Thomas Campbell, Joseph Cottle, George Croly, George Daniel, Ebenezer Elliott, Felicia Hemans, J. A. Heraud, William Herbert, Samuel Ireland, M. G. Lewis, Charles Lloyd, H. F. Lyte, John Mitford, Mary Russell Mitford, David Macbeth Moir, James Montgomery, John Moultrie, Ann Radcliffe, William Stewart Rose, Robert Southey, Thomas Talfourd, Henry Kirke White and John Wilson.

In the mid-century: Thomas Aird, Matthew Arnold, William Edmondstoune Aytoun, Philip James Bailey, Thomas Lovell Beddoes, Alexander Bethune, J. S. Bigg, Horatius Bonar, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Robert Browning, Robert Buchanan, Thomas Cooper, Sydney Dobell, R. H. Horne, Ernest C. Jones, Letitia Landon, Gerald Massey, Robert Montgomery, Caroline Norton, John Walker Ord, E. H. Plumptre, Alexander Smith, William Sotheby, Lady Emmeline Stuart-Wortley, Henry Taylor and Isaac Williams.

a Country Churchyard,’ while a smaller group elaborates that poem’s contrast between noble and humble dead. Another large group of poems evokes abstract and metaphorical graves in a melancholic effusion, while many long ballads use the grave to organise a narrative. Mythological stories with resurrection motifs, many of Celtic origin, may have a contemporary application which allies them with uses of the grave as a metaphor for political oppression, revolution or anti-patriotic protest, and in turn intersect with the group focusing on marginal social figures.

Even this short résumé indicates surprising as well as expected contexts: the grave is a conventional motif in poetry, but also a flexible and fertile hybrid. I concur with Hickok’s wish ‘to register and retain the uniqueness of each poem, even when ... many similar poems can be collected and shown to constitute a genre or tradition in which a theme is consistently treated with similar imagery, form, and rhetoric’ (p. 13). These traditions can be remarkably consistent, as for example in poems about the slave’s g rave but an apparent lack of originality is not necessarily a justification for discarding the poets who sustain the tradition. Comparing superficially similar terms of reference, as in comparisons of different textual versions, can emphasise the different nuances which contribute to a poet’s voice, while an ironised or divided interpretation may be suggested precisely in these minute distinctions.

Linda K. Hughes proposed that the issue of Victorian Poetry which I have taken as a sample of critical strategies, was intended ‘to indicate the range of material available for research and to encourage reopened narratives of individual poets and of what constitutes “Victorian poetry’” (Hughes 1995, p.5). These objectives harmonise with the methodology I have used, as does Hughes’s recommendation that ‘complex accounts of historical context (including interrelationships of female and male writers as well as constraints of class and locale)’ (p.6) might avoid the overdetermined readings which have sometimes marked feminist- influenced responses to less-read poems. In this case, the primary historical context is developments in cultural approaches to burial during the nineteenth century. British preoccupation with death shifted from grave-robbing to cremation by way of the exposure of burial abuses, campaigns for sanitary reform, the closure of urban burial-grounds and the opening of private then public cemeteries.^ Change in burial-practice is traumatic for any society, but when that change is sudden, far-reaching and forced by dangers to public health, the impact must be great. By focusing on the grave I seek to bring attention to the importance of the body after death and when it is out of sight, and explore poets’ rhetorical negotiation of this site.^

'See II, pp.320, 429.

^This emphasis on historical specificity has limited my use of works on death culture in France and America. Important books such as Philippe Aries’s The Hour of Our Death or David Sloane’s The last great necessity present histories which are broadly comparable but differ significantly in detail from Britain’s. I refer to American texts only where they have a clear influence on British culture.

The moral purpose of much grave-poetry suggests that the use of conventional tropes and imagery does not simply indicate a paucity of ideas. Such poems often commemorate a person who has died, or remind the living that we too will die, and must look after our immortal souls. Mortality is a universal fact, and so the language of mortality tends to address us generally rather than individually. Wordsworth’s recommendations for epitaph-writing in the ‘Essays on Epitaphs’ include using the general language of humanity as connected with the subject of death’ (Owen and Smyser 1974, v.ll, p.57) and that the memorialist should describe a dead man’s character in a way that ‘spiritualises and beautifies’ it, since a memorial is a public object with a moral and instructive role. As part of this generalising and equalising purpose, he says, ‘in no place are we so much disposed to dwell upon those points, of nature and condition, wherein all men resemble each other, as ... by the side of thé grave’ (p.59).^

This explicit notice of the material grave-site recognises the identification of the living with the dead, but also suggests that this equality of all men in the sight of death tends towards the use of an accessible and shared language to express likeness and common feeling. Thus the affirmative gestures towards Christian salvation which recur in most genres of grave-poetry, indicate at once (usually) sincere hopes for future life, and are a means of universalising specific experience; for while denominations may confiict, most creeds embrace the immortality of the soul in some form. Such conventional language also performs a ritual function. The twentieth- century passion for modernist individualism has led to a caricaturing of conventional language as imitative, passive and the preserve of the cowardly and unoriginal; and in some cases this is true. However when imaginatively handled such language can approach the transcendent function then associated with it. Faced with the trauma of loss, the decision to use phrases and vocabulary apparently burnished by centuries of use, a ‘general language of humanity,’ suggests an ambitious intent as often as it does a weak one.

After giving these poems (as far as possible) a fair hearing, and setting them in the context of contemporary attitudes to disposal, commemoration and burial landscape, I reconsidered the question which first interested me in grave poetics: how does the fear of death interact with the creativity of a person who identifies him or herself as a poet? I follow Elizabeth Bishop in believing that ‘there is an element of mortal panic and fear underlying all works of art,’^ and find this creative (and destructive) energy especially pertinent to poetic representations of the grave. Our private imaginings of death tend to run to the extremes so thrillingly exploited by gothic; when externalised morbid fantasy can have a cathartic effect, not least in showing manners of death and horror which are unlikely to be replicated in our own lives and deaths. Fictionalising and representing death gives a sense of control over the unimaginable and uncontrollable, by limiting - if only temporarily - the anarchic potential of loss of consciousness and physical decay. However the most popular mode for framing and controlling the idea of death was not gothic, but pastoral. Faced with an almost gothic reality, the imagination reverted

’Wordsworth’s ‘Essay on Epitaphs’ was more influential than Godwin’s ‘Essay on Sepulchres.’ First published in Coleridge’s periodical The Friend \n 1810, excerpts were quoted as an authority in Edwin Chadwick’s A Supplementary Report on the results of a special Inquiry Into

the practice of Interment In towns (1843), and it was reprinted in Joseph Snow’s Lyra Memorlalls (1847).

to a more reassuring and contained image, typified by Thomas Gray’s churchyard; the social and existential anxieties latent in nineteenth-century attitudes to death sustained the literary and cultural norm of the peaceful rural churchyard/ These conventional values are also reflected in poems of homage to older, greater poets which are often located at or refer to the grave. Tribute-poetry is an inherently conservative genre which, like much of the less-read material on

English Poetry 1800-1900, is elegiac in impulse, defending and upholding an anachronistic near religious zeal for poetry and the bardic authority of great poets. For many, personal ambition was constrained or tempered by a lingering faith in this cult of authority, represented most strikingly by Wordsworth and Tennyson.^

However, conventionalising impulses coexist with the author’s desire to control his or her own destiny, to personalise ending - and to keep writing. The writer dramatises and fictionalises his or her life-experiences in mediated forms, and the anticipation of death and burial is in certain respects just another of these experiences. In terms of historical fact, the grave is a site of uncertainty, violence, disgust and even depravity; in writeriy terms it is a site of passivity and silence which paradoxically can only be described using the vocabulary of life.^ The writer responds to this anticipated loss of articulation and control, by asserting the individual and personal as a protest against death’s wordless anonymity.'* Composition is a hopeless defence against inevitable decomposition, and writing about the grave is a way of trying to articulate the inexpressible, to replace the abstract and unknown with familiar and consoling images.

Thus poets of the grave are caught in a double bind: on one hand, they are attracted to a timeless image of death in nature, expressed in universai and transcendent language which will voice human and spiritual longings; on the other they strive to make individual rhetorical gestures in order to leave an idiosyncratic stamp on the world after death. This paradox articulates two fundamental and coexisting attitudes: the conscious will to accept death as inevitable, and the usually less conscious desire to fight against this inevitability. The tension between overt acceptance and covert refusal can be observed in most poems representing the grave. The ostensible 'message’ of the poem generally harmonises with the universalising and accepting impulse; however where questions of individual creativity are at issue (as when a father writes about his child’s grave, or a poet contemplates the grave of a precursor poet), the dissenting and personal voice may become more audible.

My conviction that the need to write is psychologically motivated by anxiety ultimately fuelled by fear of death, and by the desire to speak after a period of repression or to compensate for a felt lack, associates my critical approach with influential texts such as Harold Bloom’s The

‘ Herbert F. Tucker’s review essay on Isobel Armstrong’s Victorian Poetry {1993) suggests the contemporary relevance of this critical question; he says the book offers ‘worthy insights into the elegiac bases of Victorian poetry ... The dialectic whereby pain is repeatedly honoured, and Interpretively overcome, may be at once the most personal thing about VP [Armstrong’s book] and the most Victorian’ (Tucker 1995 p.187).

^John Critchley Prince’s 'The Poets’ begins ‘Oh! how deeply I venerate, how passionately I admire the Poets of all ages and climes’ and ends ‘Biessings on the Poets — I love them all!’ (Prince 1847, pp. 178-9).

Anxiety of Influence and The Map of l\/llsreadlng, or Garrett Stewart’s Death Sentences. Bloom’s assertion in The Map of Misreading (1975) that ‘a poem is written to escape dying,’ that ‘poems are refusals of mortality’ (p.19), is also pertinent to the elegiac and commemorative themes of this project, since most of these poems bear the ironic stamp of their critical mortality. According to Bloom’s thesis, this makes them failures, and critical concern with them is symptomatic of a disastrous revisionary regression. I do not find Bloom’s masculinist, canonical and psychoanalytic dogmatism sympathetic, and clearly his emphasis does small service to less-read poems.^

Many versions and revisions of Bloom’s theory of poetic tradition have been posited.^ I seek to reapply the idea that ‘Initial love for the precursor’s poetry is transformed rapidly enough into revisionary strife, without which individuation is not possible’ (p.10), in a noncanonical critical environment. My revision of Bloomian influence theory shifts the focus from intergenerational rivalry, ‘misprision’ of ‘strong’ poets and even from ‘individuation,’ to the different forms such relationships may take for less-read poets.® Instead of Bloom’s precursors and ephebes, Oedipal sons and warring brothers, I posit a less aggressive familial metaphor which gives room for subtler gradations of hostility and love, and is more accessible to female influence.^ I regard poetic tradition and (inter)relationship as a complex of kin-like relations, which Is sometimes manifested as an aggressive conflict between son and father, but includes other more ambiguous sororal and constructive associations.

This preoccupation with the family is historically appropriate to the nineteenth-century cults of domesticity and maternity, pertinent to the dominant tradition which constructed the grave as a home-like and private place, and is an attempt to make the generational model more flexible and inclusive. This familial metaphor inevitably retains some psychoanalytic associations with Freud’s ‘family romance.’ No single psychoanalytic model of family relations is consistently enabling when applied to a private person’s development or a poet’s relation to his precursors and peers. At the risk of oversimplification, I prefer to evoke plainer experiential concepts, again based in the historical context.

Many nineteenth-century middle-class authorities propounded a model of the family which was hierarchical and rigid, organised to cultivate moral and religious health in the rising generation. The forms of this ideal family varied, from a dignified miniature of the stratified social order, with the paterfamilias presiding over carefully moulded and strictly controlled wife ‘ E.g., ‘Strong poets are infrequent... Browning, Whitman, Dickinson are strong, as are the High

Romantics, and Milton may be taken as the apotheosis of strength. Poetic strength comes only from a triumphant wrestling with the greatest of the dead, and from an even more triumphant solipsism’ (Bloom 1975, p.9),

^See Grosman 1984, Federmayer 1984, Miner 1985, Sellars 1993 and Waswo 1989.

^See Bloom 1976, p.2: ‘A poetic “text,” as I interpret it, is not a gathering of signs on a page, but is a psychic battlefield upon which authentic forces struggle for the only victory worth winning, the divinating triumph over oblivion’; Bloom’s antithetical criticism succeeds by a process of stringent selection, such as subjectively deciding that certain privileged prose- writers are ‘poets.’

and children (see Figure 1, p.20), to a Romantic union of affection and unselfish mutual care. The popular Victorian novelists propounded these domestic ideals by juxtaposing the fates of irregular and vicious families with those of the idealised. Amidst the broken homes and dysfunctional families of Bleak House, the contrasted Jellyby and Bagnet families suggested that a well-ordered and respectable family depended on moral health and conviction rather than money.^ Regardless of how far real families differed from the model, with their scandalous separations, single parents, childlessness or infidelity, public faith in it remained strong.

I found the cult of domestic and familial affection to be particularly strong in these poems, although striking ambivalences and protests against the ideal, and its effect on women specifically, appear in the period 1870-1900. The priority of the mother as a force for moral good and social cohesion is an important counter to paternalistic interpretations of history. Given the conservative and conventionalising effect of the fear of death, it is not surprising that the cult of domestic values is so strongly upheld in poems about family deaths and graves.^ Death constitutes a threat to the family’s integrity, and this fear of fragmentation often inspires compensatory gestures and exaggerated statements of faith in familial continuity and in the afterlife.® Such appeals are seldom unqualified by indications of the speaker’s deep regret and fond memories of the deceased, and these mildly contradictory sentiments effectively express the gap between intellectual conviction that the dead are saved, and emotional regret for their loss.

I believe that each individual carries a private sense of what the family should be, and measures his or her own circumstances against this unseen ideal. In favourable situations this fantasy family matches closely to the reality, and of course involves none of the powerful involuntary emotions generated by actual familial relationships. But under stress individuals see deficiencies, absences or injustices which give these fantasies a greater emotional significance. I cannot speculate on the circumstances which make someone a writer, and for many of the nineteenth-century poets with whom I am concerned, writing is less a Romantic vocation than a labour, occupation, pastime or habit; but the impulse to write is frequently linked to the desire to create an alternative reality and compensate for lack.^

The act of writing is at once communicative and isolated, out-reaching and self- referential, and this approximates to my sense of the individual’s ambivalent relation to the family. Family members may be emotionally bonded by a sense of blood likeness, a similarity

^The Bagnets are the only remotely promising family group in the novel, although the next generation manage to redeem their backgrounds; while Mr. Bagnet is posited ironically as the arbiter of discipline, Mrs. Bagnet is the true source of moral and domestic order.

^John Wolffe has recently suggested that this familial cult extended to public figures. In reading late-Victorian memorial sermons he found that there was a 'growing tendency in this period for people to identify their personal bereavements with those of the Royal family: thus the

Duke of Clarence was every middle-aged parent’s rising hope and every young woman’s fiancé, just as Queen Victoria was to be everyone’s mother and grandmother and Edward VII everyone’s father’ (Wolffe 1996, p.293).

^Compare Robert Southey’s letter to his daughters in July 1826: ‘Did we consider these things wisely, we should perceive how little it imports who may go first, who la st;... You know how I loved your dear sister, my sweet Isabel, who is now gathered to that part of my family and household (a large one now!) which is in Heaven’ (Southey 1850, v.V, pp.256-7).

and identification which makes their interests unite; at the same time, the passing of time brings divisive changes to the family’s hierarchical structure, and the authorial impulse often involves individuation and separation from the larger unit.

This awareness of family shapes my concern with the biography of these less-read poets.^ Nineteenth-century families were extended and multi-generational, and these large complex units would often co-habit. I am concerned with details such as whether the poet wrote at home, how much time he or she spent directly caring for, playing with or nursing their children, and how they responded to deaths of family and friends, especially of their own children. Thus the Bloomian psychoanalytic preoccupation with literary fathers is literalised and historicised by investigation of the poet’s multiple private identities as parent, child, sibling, spouse, soulmate and so on.^

This approach also offers a fresh perspective on the poet’s negotiation of the future. For Bloom the past tradition is almost always triumphant, and the nineteenth-century poet is doomed to retrospection, repetition and pining to be Milton. However, poets who were also parents regarded their children’s future in a way which qualifies this combative view. The child’s survival into a future inaccessible to the poet affirms personal continuity through the creation of flesh by flesh, physical resemblance, perpetuation of family name, moral values and communal memory. Thus for a poet who is also a parent, the ambition to write great poetry may be less dominant, or at least differently arranged, than for someone without that experience; making children, like making poems, offers a negotiation of the future and hope of immortality. Where Bloom believed that Romanticism was ‘appalled by its own overt continuities, and vainly but perpetually fantasizes some end to repetitions’ (Bloom 1975, p.36), I suggest that many uncanonical Romantic and post-Romantic poets pursued and validated continuity in their writing as in their parenting. Presumably Bloom would see this as slavish imitation, confirmation of inferiority and creative death; in my less heroic view of poetic aspiration, poets might seek individuation precisely by re-using familiar tropes and motifs. Protected by respectful redeployment of the tradition, independent gestures may have a far smaller compass, but they are made possible in the humble transformation of the familiar.

This grounding in experience is an important influence on how graves were represented in poetry; for more than most literary images and tropes, the poet’s imagining of a grave is likely to be directed by personal experience. Even casual contact with death and its rituals can create a sense of personal anxiety or crisis, encouraging self-reflexivity or selfishness; we suffer at the death of another because we are deprived of them, but we also fear for the future moment of our own death. This anxiety for the self touches every poet’s representation of a grave, although it may be only a trace in texts with strong devotional or consolatory intent. Every grave

’Jürgen Schlaeger’s remark suggests parallels between writing biography and grave-poems: ‘In the face of a meaningless death, biography gives life an extension. It is, as such, one of the most successful efforts at secular resurrection.... Biography pits the abundance of past life against the present monotony of death.' Life in biography is luxuriant, death is sterile’ (Schlaeger 1995, p.68).

is potentially the poet’s own, or that of a loved one, and this image of terminated creativity haunts contemplations of past and future. Behind most textual graves, even some of the more abstractly treated, there are memories of material graves, and beyond that are memories of the beloved dead; but these formative models are indivisible from the individual’s anxiety about the end of his own consciousness. Like Scrooge guided through Christmases past, present and future only to arrive at his own headstone, ultimately the individual cannot deflect the grave; only the author can stage this triumph in writing.

Scrooge’s story is a helpful illustration of this thanatological primal scene. As the Victorian cult of Christmas was intimately related to the sanctifying of domestic affection, Scrooge’s denial of family, festivity, compassion or affection show he is a lost soul. The grave presented to him in Stave Four by the grim silent spirit of Christmas yet to come is symbolic and

drawn from life. It lies in one of the repulsive city churchyards which will haunt my first chapter, boxed in by the homes of the living, glutted with death, perpetuated even in ‘the growth of vegetation’s death, not life’ (Dickens 1971, p. 124). While A Christmas Carol’s overdetermined narrative leaves the reader in no doubt of the man’s identity, Scrooge denies the self-reflexive significance: ‘Here, then, the wretched man whose name he had now to learn, lay underneath the ground.’ The deathlike guiding spirit points doggedly at the end he must face, and only after negotiation and delay does Scrooge face his nemesis: ‘Scrooge crept towards it, trembling as he went; and following the finger, read upon the stone of the neglected grave his own name, EBENEZER SCROOGE.’^ This encounter with the ultimate memento mori image makes a powerful end to Scrooge’s lesson; but because this is a dream-vision, he has the chance to come back from the grave and redeem himself. In a similar way the poet’s encounter with the grave provides a strongly creative and life-affirming impulse, renewing the individual’s contract with life through varied rhetorical strategies.

The poet invokes the grave to transcend and control it, and incorporates it into poems to deny its power over life and creativity. The grave is the creative artist’s ultimate obstacle, but it is defused or distanced by troping and transformation into a literary medium, particularly where the speaker sets up a dialogue with the dead, using direct address or soliloquy to revive them for the poem’s duration. The grave’s lethal challenge to poetic identity haunts these poems, whether the grave belongs to the poet, a child, a friend or lover, or to members of an extended metaphorical family of close friends, sympathetic creative artists, and precursor poets. Yet at the same time poets reveal a desire to retain or preserve the grave’s image within their poems. If we generally regard the grave with abhorrence, we must to some degree learn to love the specific burial-place of a loved person, and by textualising the grave this loving memory stands more chances of preservation within the broader cultural memory. For this reason I have mostly discussed poems which affect to represent real graves, churchyards and cemeteries, and in which the grave has some peculiar or personal interest for the speaker. This lyric mode and personal investment is also conducive to moments where divisions between imagination, literary

representation and materiality are disturbed or transgressed, as the poet tries to bring the grave

into the poem, so making it the passive object of his or her own creation.

The groups of poems I discuss at length illustrate a few of the different generational relations and subject positions which might be significant for the grave-poet. Initially I concentrate on self-reflexive anxiety about the grave through individual reactions to changes in burial practice. In the rest of the thesis I explore two contrasted but intimately related themes; parents’ poems on the deaths and graves of their children, and poets’ responses to the deaths and graves of their literary parents.^ I have consciously made a division between poems which originate in domestic and private experience (Chapters 1 and 2), and those which stem ostensibly from literary and public impulses (Chapters 3 and 4). Thus the critical focus moves from domestic graves to public, literary graves and monuments which have a broad or national significance. By juxtaposing these private and public impulses, I wish to suggest that the emotional drives concerned are actually closely related, and that the familial attitudes taken in poems on a beloved child’s grave, have a metaphorical significance in tribute-elegies on the graves of precursor-poets. This contention is supported by close correspondences between the child-elegies of Chapter 2 and the tribute-poems to Keats, in particular, examined in Chapter 3.

As I have said, my intention was to shift the masculinist bias of Bloom’s ‘anxiety of influence’ thesis towards a more inclusive and feminised model, and to suggest the assimilation of male and female poets within a shared tradition. However it has become evident that several of the themes I researched are written about most fully and directly by male writers; nineteenth- century women wrote less about their dead children’s graves than men did, and they found the genre of tribute-poetry less compulsive. As a result, the work of male poets figures more prominently in my argument. Gender has a small effect on how poets react to topics of general social concern, such as body-snatching or city burial-grounds, but its effects are wide-reaching where male and female experience diverges. I have indicated some of the different approaches women poets make to these subjects in order to suggest the interesting work waiting to be done on the distinctive masculine and feminine conventions of grave-poetry.

Chapter 1 : The country churchyard aesthetic and social history of death.

Oh! how I hate the cumbrous pride Of plume and pall and scutcheon’d hearse, And all the rank and ready tide

Of venal prose and lying verse. Nor in the city’s churchyard, rife With close compacted crowds of dead. And clogged with thoughts of stir and strife, Would I consent to lay my head.

John Kenyon, ‘Written in a Country Churchyard,’ 1-8.^

John Kenyon’s decisive rejection of two possible burials places him with virtually every poet who wrote about graves in the nineteenth century. While the poem’s regular four-stressed lines and blunt alliteration may give the reader little aesthetic satisfaction, ‘Written in a Country Churchyard’ is an exemplary model of how poets imagine the grave. In the first stanza Kenyon dismisses the old-fashioned heraldic funeral, where publicity matters more than private feeling, and posthumous display is purchased independently of merit. The undertaker’s trappings are bought in the same way as the ‘venal prose and lying verse’ of obituary, biography, tribute-verse and epitaph, and all indicate a self-esteem which is almost materially ‘cumbrous’ in its outward signs. The second stanza’s urban grave is both a contrast to and extension of the first; the crowded graves suggest the opposite end of the social scale, where there is no money for display and little pride or even dignity, yet the accumulation of nouns indicates that both are products of a debased and materialistic culture. At one extreme, the poet shuns public and worldly commemoration; at the other, he does not ‘consent’ to obscurity amidst stifling ‘crowds of dead.’

With rare exceptions, nineteenth-century poets celebrated a grave which was not stately, public, urban or crowded. These negative criteria were answered by an iconography with a long tradition, and in making this choice such poems are direct inheritors of Thomas Gray’s ‘An Elegy written in a Country Churchyard,’ first published in an eleven-page booklet in 1751, and often cited as the most famous poem ever for its enduring popularity in innumerable editions.^ Not only does the poem end with an ‘Epitaph’ for the melancholy poet, but its author was buried in the churchyard rumoured to be the poem’s inspiration. Individual writers described this rustic churchyard in terms ranging from conventional abstraction to eccentric particularity, but variations do little to disturb the churchyard’s symbolic values. The rustic grave was natural, peaceful, homely and stable, close enough to places of habitation for mourners to visit and

'Kenyon 1838, p. 124.

^See II, pp.314, 381-3. It was republished on its own, with engravings, in collected editions of Gray’s poetry, and in anthologies of death meditations with poets of the more hectic

‘Grave-yard’ school. Partnered with Robert Blair’s ‘The Grave’ it ran through at least twelve editions between 1761 and 1817 alone. Blair’s poem was also revived by William Blake’s celebrated etchings (1808). The popular design for ‘Death’s Door’ shows an aged man crossing the threshold of a massive stone tomb, while the youthful, muscular resurrected soul gazes radiantly towards Heaven from the roof; Walt Whitman modelled his tomb from

remember, but separate and private enough for eternal rest, untroubled by curiosity, spite or disturbance (see Figures 2 and 3 on p.26). Avoiding extremes of publicity and obscurity, the lyric speaker imagined a quiet grave in nature, which was then immortalised in the poem. John Kenyon’s choice, anticipated by the title’s quotation from Gray, is specific but typical. He chooses a churchyard in the Quantocks’ rolling agricultural uplands, where the simple church is framed by ‘the coppice clustering green’ (11). He seeks a ‘quiet nook’ and ‘place of resting’ (17-18) with a loved one, beneath a ‘broad majestic oak’ (19):

But o’er the turf let sun and air And dew their blessed influence fling. And rosy children gather there The earliest violets of the spring; There let the cuckoo’s oft-told tale Be heard at flush of morning light; And there the pensive nightingale

Chaunt requiem half the summer night. (25-32)

Decorated simply by turf and violets, the grave is united with the elements, which cast a benediction over the scene. Healthy flower-like children pick flowers symbolising memory in a balmy almost timeless landcape; the seasons change only from spring to summer, while birdsong ritually signals the reassuring alternation of day and night. Only the nightingale’s ‘requiem’ suggests death, and this is less memento mon than Keatsian echo.

In other poems, the tree is a yew, cypress or laurel; daisies or lilies grow and the grave is marked with a modest stone; but these details do not fundamentally change the image’s meaning.^ The country churchyard is a homely burial-place, where the dead are remembered by the local community as they go to worship, the grave is untroubled by interference or development, and seasonal cycles symbolise continuity and minimise deathly associations.^ By choosing this grave at Broomfield, Somerset, Kenyon implied that death was not the end of life. Many poets were more dogmatic about salvation and spiritual transcendence of the earthly body; death cannot be avoided, but here its harsher manifestations are suppressed. The poet encourages our complicity in the benign self-deception that a beautiful and peaceful grave makes death less terrible.

‘Written in a Country Churchyard’ is a poetic last will and testament, a document which anticipates the poet’s grave, and directs survivors how to arrange the funeral to show most respect.^ This proleptic movement, which speculates on a future time when the poet’s consciousness has ceased, is a gesture of control which indicates a will to continue life; what (or

’Compare the churchyards in ‘The Widow and Her Son,’ ‘Rural Funerals’ and ‘The Pride of the Village’ in Washington Irving’s Sketch Book {1820).

^Christopher Wordsworth was one of many who made substantial claims for the churchyard’s moral effect. ‘It is ... favourable to religious meditation and prayer. The influences of air and sky, sun and stars, and the vicissitudes of the seasons, and the ever varying vegetation of shrubs and flowers blend their inaudible harmonies with the teaching of Holy Scripture, and with the solemn thoughts of Death, Judgement, Resurrection, and Eternity, breathed in silent and ceaseless eloquence from the graves’ (C. Wordsworth 1874, Preface).

Figure 2. Bury St. Edmunds Cathedral churchyard, Suffolk, 1995. This image of leaning headstones touched by early evening sun may catch the mood of Gray’s ‘Elegy,’ but the country churchyard in poems is rarely found in reality. If this place of grassy hummocks and wildflowers ever existed, it has been erased by generations of increasingly uniform funerary monuments.