ABstrAct

Myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) are rare, yet potentially life-threatening, disorders caused by overproliferation of bone marrow stem cells. The symptom burden experienced by patients with the BCR-ABL1-negative MPNs (also referred to as the clas-sical MPNs, i.e., essential thrombocythemia [ET], polycythemia vera [PV] and myelofibrosis [MF]) can be significant and can neg-atively impact quality of life (QOL). Since patients with these MPNs can live for several years, thereby requiring long-term treat-ment and follow-up, nurses play an essential role in communicat-ing with these patients, assesscommunicat-ing their symptoms, and educatcommunicat-ing them on treatments and self-management strategies that can reduce their symptom burden. This article, which is the second of a two-part series, was developed to provide nurses and other healthcare professionals with practical guidance for managing the symptom burden associated with the classical MPNs in order to help enhance their patients’ overall health and QOL.

Key words: myeloproliferative neoplasms, essential thrombo-cythemia, polycythemia vera, myelofibrosis; symptom burden, nursing management

iNtrODuctiON

T

he most common BCR-ABL1-negative MPNs (also referred to as the classical MPNs) are essential thrombocythe-mia (ET), polycythemia vera (PV) and myelofibrosis (MF). The severity of these MPNs can range from mild to aggressive, and can severely affect patient quality of life (QOL) due to debili-tating symptoms and an increased risk of thrombotic events. Since patients with these disorders can live for many years and often require long-term treatment and follow-up, nurses require a good understanding of the common BCR-ABL1-negative MPNs, their associated symptoms and how to help patients manage these symptoms. This article – the second of a two-part series – was developed by a group of Canadian nurse practitioners and specialized hematology/oncology nurses to provide nurses and other healthcare professionals with prac-tical guidance for managing the symptom burden associated with the most common BCR-ABL1-negative MPNs. The first article in this series (also available in this issue) provides a review of the diagnosis and treatment of these disorders.WHAt is tHe Nurse’s rOle iN MANAGiNG

tHe sYMPtOMs OF PAtieNts WitH MPNs?

MPNs are long-term chronic illnesses and the symptom bur-den associated with these disorders can be severe. The recent MPN Landmark survey, which was conducted from May to July 2014 and included 813 patients with MPNs (MF, n = 207; PV, n = 380; ET, n = 226) in the United States, was designed to assess the disease burden associated with MPNs (Mesa et al., 2016). The survey found that these patients experience a broad symp-tom burden that leads to reductions in QOL, functional status, activities of daily living, and work productivity. Nurses play a key role in recognizing these symptoms and educating patients on self-management strategies, as well as identifying patients with unmet needs who may benefit from treatment modifications.

HOW cAN Nurses Assess tHe sYMPtOM

BurDeN OF MPNs?

Some patients with MPNs do not recognize their symp-toms because they can develop gradually over time and, hence, can be dismissed as normal effects of aging, such as increased fatigue and inactivity. Thus, it is important for nurses to com-municate regularly with patients to identify symptoms early on so that appropriate interventions can be initiated. The 10 most clinically relevant disease-related symptoms of MPNs are: fatigue, concentration problems, early satiety, inactivity, night sweats, pruritus (itching), bone pain, abdominal discomfort, weight loss, and fever (Emanuel et al., 2012).

Myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) – Part 2:

A nursing guide to managing the symptom

burden of MPNs

by Sabrina Fowlkes, Cindy Murray, Adrienne Fulford, Tammy De Gelder, and Nancy Siddiq

ABOut tHe AutHOrs

Sabrina Fowlkes, RN, BScN, Nurse Clinician, Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia/ Myeloproliferative Neoplasms, Jewish General Hospital, Montreal, Quebec Cindy Murray, MN, NP (Adult), Nurse Practitioner, Malignant Hematology, UHN Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, Toronto, Ontario

Adrienne Fulford, NP-PHC, MScN, CON(C), Nurse Practitioner, Hematology Oncology, London Health Sciences Centre, London, Ontario

Tammy De Gelder, MN, NP (Adult), CON(C), Nurse Practitioner, Hamilton Health Sciences, Juravinski Hospital and Cancer Centre, Hamilton, Ontario Nancy Siddiq, RN, BScN, CON (c), MSN in Education, Clinical Nurse Specialist for Myeloproliferative Neoplasms (MPN), Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, Toronto, Ontario

Corresponding author: Cindy Murray, MN, NP (Adult), 610 University Ave.,

Toronto, ON M5G 2C4

Phone: (416) 946-4501 ext. 5919; Email: Cindy.Murray@uhn.ca DOI: 10.5737/23688076284276281

The MPN-10, formerly known as the Myeloproliferative Neoplasm Symptom Assessment Form Total Symptom Score (MPN-SAF TSS), is a validated instrument designed to quanti-tatively assess the burden of symptoms in patients with MPNs (see Figure 1) (Emanuel et al., 2012). It can also be used to track disease progression and response to treatment, thereby facilitating disease management and enhancing the communi-cation between nurses and patients.

The MPN-10 is available in paper form or as a web app (http://www.mpn10app.com/) and includes the 10 most clin-ically relevant symptoms of MPNs. Each symptom is scored from 0 (absent/as good as it can be) to 10 (worst imaginable/as bad as it can be), with higher scores indicating a higher symp-tom burden. Repeating the MPN-10 assessment at subsequent visits can help provide a chronologic impression of symptom burden over time and determine the effects of treatment inter-ventions, as well as symptom-management strategies.

WHY DO tHese cOMMON sYMPtOMs

Occur AND WHAt strAteGies cAN Be

useD tO HelP PAtieNts WitH tHese

clAssicAl MPNs MANAGe tHese

sYMPtOMs?

Regardless of the type of MPN, fatigue (which often leads to inactivity) is the most commonly reported disease-re-lated symptom, occurring in 80-95% of patients with MPNs (Scherber et al., 2011). It can be one of the most debilitating MPN symptoms, affecting not only physical and social func-tioning, but also substantially impairing QoL (Mesa et al., 2007). In fact, it is one of the main reasons for the inability of patients with MPNs to work (i.e., 31% of patients with ET, 40% of patients with PV, and 59% of patients with MF are unable to work due to fatigue) (Michiels, 2016).

Fatigue is multifactorial in nature, resulting from: the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines (particularly interleukin [IL]-1, IL-6, IL-8, and tumour necrosis factor [TNF]-α); impaired hema-topoiesis causing anemia, infection, thrombosis and microvascu-lar symptoms; deconditioning; depression; and even medication side effects (Radia & Geyer, 2015; Scherber et al., 2016). Given the multifactorial nature of this symptom, fatigue is often diffi-cult to assess and treat. Management generally requires a multi-faceted approach that includes treatment of the particular MPN, treatment of any underlying contributing factors (such as antibi-otics for infection, red blood cell transfusions for anemia, platelet transfusions for low platelet counts, and antidepressant therapy for depression) and advising patients on various non-pharmaco-logical approaches. The latter may include: encouraging patients to engage in regular physical activity; advising on sleep optimi-zation and stress reduction strategies; monitoring fatigue pat-terns and planning activities according to peak energy periods; and referral to rehabilitation programs (Howell et al., 2015). A recent survey of more than 1,700 MPN patients found that many non-pharmacological strategies were used to reduce fatigue (Scherber et al., 2016). Participants reported that the most help-ful strategies included: scheduling activities during times of peak energy, pacing activities, setting priorities, labour-saving devices, and walking. One of the most striking findings of this study was the strong correlation between exercise and reduced fatigue; sub-jects who were physically active reported less fatigue compared with those who were sedentary.

When used as indicated for the treatment of MPNs, ruxoli-tinib has been shown to reduce fatigue symptoms by approx-imately 50% compared to standard therapy (standard therapy was selected by the investigators and could include hydroxy-urea, interferon, pipobroman, anagrelide, immunomodula-tors, or no medication) (Vannucchi et al., 2015). Ruxolitinib has also been shown to reduce spleen size (which may improve activity levels) and to improve appetite (which may indirectly improve fatigue and inactivity by increasing energy levels) (Mesa et al., 2013; Verstovesk et al., 2012).

Abdominal-related complaints in patients with MPNs, such as early satiety and abdominal discomfort/pain, are largely attributable to splenomegaly (Radia & Geyer HL, 2015). The development of splenomegaly in MPNs is believed to result from splenic sequestration of blood cells and extramedullary hematopoiesis (Mughal et al., 2014). The splenic enlargement prevents stomach expansion when eating and, hence, patients cannot eat large volumes, resulting in early satiety. In general, abdominal discomfort is due to the mechanical pressure of the spleen, but it can also result from splenic infarction causing pain that often requires analgesia.

The key goal for the management of early satiety is to max-imize nutritional intake with minimal volume. Therefore, patients should be advised to consume small, frequent, high-energy, high-protein meals and snacks, as well as ener-gy-dense liquids between meals to help meet fluid require-ments (BC Cancer Agency, 2005).

Patients experiencing abdominal discomfort should be instructed to take medications that have been shown to reduce spleen size (e.g., hydroxyurea and ruxolitinib—discussed in Part 1 of this two-part series), as prescribed (Cervantes, 2011;

Harrison et al., 2012, 2016). Splenectomy (surgical removal of the spleen) may also be beneficial for relieving abdominal pain. However, given the risks associated with this procedure, it is usually reserved for patients who are refractory to drug treatment, or who have transfusion-dependent anemia that is unresponsive to therapy, or portal hypertension (Cervantes, 2011). Splenic radiation is also an option for poor surgical can-didates and for palliation of severe pain from splenic infarcts. However, the effects of radiation may not be durable.

Pruritus, described as generalized itching, prickling, or burn-ing, tends to be more common in patients with PV than other MPNs (Mesa et al., 2015). It is usually triggered by exposure to water of any temperature (aquagenic pruritus), but may also be triggered by other stimuli such as a sudden change in tempera-ture, sitting next to a fire, sweating after exercise, alcohol con-sumption, or the use of warm bedclothes at night (Saini et al., 2010; Radia & Geyer, 2015). It can also develop spontaneously, without recognizable precipitating factors, or be constantly pres-ent. Although the pathophysiology of pruritus in patients with MPNs is not completely understood, it is believed to be related to the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines. The management of PV-associated pruritus is largely based on empirical evidence, and may include interferon-alpha, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), antihistamines, avoidance of triggers, use of emollients, and narrow band ultraviolet B (UVB) phototherapy for severe cases (Saini et al., 2010; Radia & Geyer, 2015).

Bone pain can be a presenting or late feature of MF. Although the pathophysiology of bone pain in MF is not com-pletely understood, it is believed to be due to overproliferation of the bone marrow, periostitis (inflammation of periosteum, which is the layer of connective tissue surrounding bone) and osteosclerosis (hardening of the bone) associated with MF (Neben-Wittich et al., 2010). Opioids are commonly used for bone pain in MF, but some patients may not experience relief from these medications. Case reports have shown low-dose radiation to be effective in patients unresponsive to pain medi-cations (Neben-Wittich et al., 2010).

Problems with concentration are typically microvascular symptoms that result from disease activity occurring at a cap-illary level. They also appear to be related to the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines that disrupt neurohormonal signalling and impair neurotransmitter production (Geyer et al., 2015). Other common MPN-associated symptoms, such as fever, night sweats and weight loss, are also related to the release of inflammatory cytokines during the disease pro-cess (Geyer et al., 2015; Hermouet et al., 2015). Treatment with ruxolitinib has been shown to improve these constitu-tional symptoms compared to standard therapy or placebo (Vannucchi et al., 2015; Mesa et al., 2013; Verstovesk et al., 2012). For patients with concentration problems, relaxation, meditation, memory aids and mind-stimulating activities can be helpful (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013). For patients experiencing weight loss, referral to a dietician for nutritional counselling may be required.

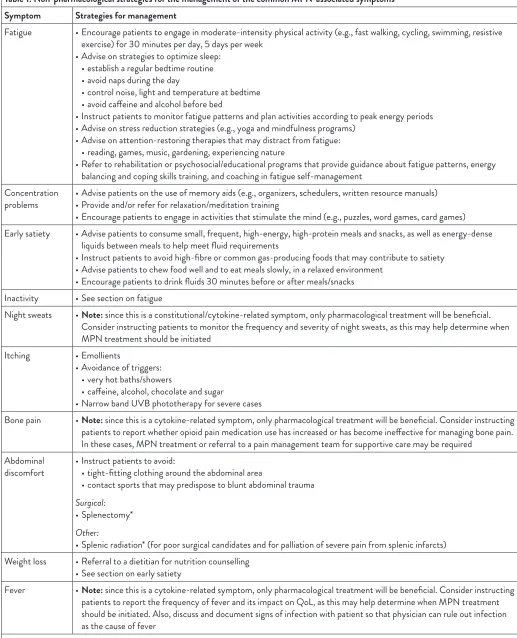

Table 1: Non-pharmacological strategies for the management of the common MPN-associated symptoms Symptom Strategies for management

Fatigue • Encourage patients to engage in moderate-intensity physical activity (e.g., fast walking, cycling, swimming, resistive exercise) for 30 minutes per day, 5 days per week

• Advise on strategies to optimize sleep: • establish a regular bedtime routine • avoid naps during the day

• control noise, light and temperature at bedtime • avoid caffeine and alcohol before bed

• Instruct patients to monitor fatigue patterns and plan activities according to peak energy periods • Advise on stress reduction strategies (e.g., yoga and mindfulness programs)

• Advise on attention-restoring therapies that may distract from fatigue: • reading, games, music, gardening, experiencing nature

• Refer to rehabilitation or psychosocial/educational programs that provide guidance about fatigue patterns, energy balancing and coping skills training, and coaching in fatigue self-management

Concentration

problems • Advise patients on the use of memory aids (e.g., organizers, schedulers, written resource manuals)• Provide and/or refer for relaxation/meditation training • Encourage patients to engage in activities that stimulate the mind (e.g., puzzles, word games, card games) Early satiety • Advise patients to consume small, frequent, high-energy, high-protein meals and snacks, as well as energy-dense

liquids between meals to help meet fluid requirements

• Instruct patients to avoid high-fibre or common gas-producing foods that may contribute to satiety • Advise patients to chew food well and to eat meals slowly, in a relaxed environment

• Encourage patients to drink fluids 30 minutes before or after meals/snacks Inactivity • See section on fatigue

Night sweats • Note: since this is a constitutional/cytokine-related symptom, only pharmacological treatment will be beneficial. Consider instructing patients to monitor the frequency and severity of night sweats, as this may help determine when MPN treatment should be initiated

Itching • Emollients

• Avoidance of triggers: • very hot baths/showers

• caffeine, alcohol, chocolate and sugar

• Narrow band UVB phototherapy for severe cases

Bone pain • Note: since this is a cytokine-related symptom, only pharmacological treatment will be beneficial. Consider instructing patients to report whether opioid pain medication use has increased or has become ineffective for managing bone pain. In these cases, MPN treatment or referral to a pain management team for supportive care may be required

Abdominal

discomfort • Instruct patients to avoid: • tight-fitting clothing around the abdominal area

• contact sports that may predispose to blunt abdominal trauma

Surgical:

• Splenectomy*

Other:

• Splenic radiation* (for poor surgical candidates and for palliation of severe pain from splenic infarcts) Weight loss • Referral to a dietitian for nutrition counselling

• See section on early satiety

Fever • Note: since this is a cytokine-related symptom, only pharmacological treatment will be beneficial. Consider instructing patients to report the frequency of fever and its impact on QoL, as this may help determine when MPN treatment should be initiated. Also, discuss and document signs of infection with patient so that physician can rule out infection as the cause of fever

Although this article focuses on managing the unique physical symptoms of patients with MPNs, the authors recog-nize that nurses may also play an important role in address-ing the psychosocial needs of patients with these disorders, which are similar to those of patients with other forms of can-cer. A detailed review of the psychosocial impact of cancer and how nurses can support the emotional, social and psycholog-ical needs of patients with malignancies is beyond the scope of this review. However, the authors have included helpful psychosocial resources, such as the Canadian Association of Psychosocial Oncology (CAPO) website, in Table 1 (see “Other Resources for Nurses and Patients” section).

cONclusiONs

The symptom burden experienced by patients with the clas-sical MPNs can be significant and can negatively impact QOL, activities of daily living, and the ability to work and be productive,

even in patients with low prognostic risk scores and a low symp-tom burden. Improvements in sympsymp-tom recognition and imple-menting strategies to help patients with MPNs manage these symptoms can ameliorate these negative effects and, thereby, help enhance the overall health and lives of patients with MPNs. As a primary patient contact, nurses play an essential role in communicating with patients with MPNs, assessing their symp-toms and educating them on treatments and strategies that can reduce their symptom burden. Ideally, all patients with MPNs should be managed in a shared-care model, with close collabora-tion between nurses, a community hematologist/oncologist and a tertiary-care centre with expertise in MPNs.

In addition, nurses could play an important role in conduct-ing future research on the use of non-pharmacological inter-ventions for the management of the symptoms associated with MPNs, given the limited evidence on the use of these modali-ties in these patient populations.

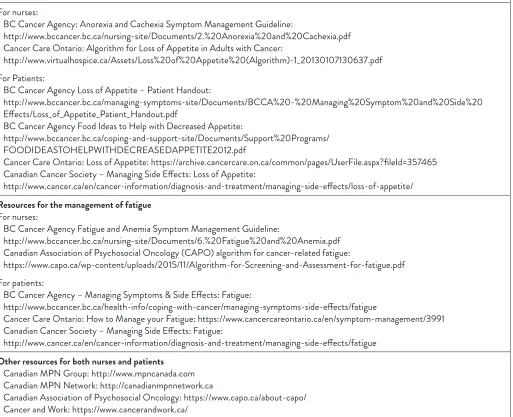

Table 2: Nursing and patient resources

Resources for the management of loss of appetite/weight loss For nurses:

• BC Cancer Agency: Anorexia and Cachexia Symptom Management Guideline:

http://www.bccancer.bc.ca/nursing-site/Documents/2.%20Anorexia%20and%20Cachexia.pdf • Cancer Care Ontario: Algorithm for Loss of Appetite in Adults with Cancer:

http://www.virtualhospice.ca/Assets/Loss%20of%20Appetite%20(Algorithm)-1_20130107130637.pdf For Patients:

• BC Cancer Agency Loss of Appetite – Patient Handout:

http://www.bccancer.bc.ca/managing-symptoms-site/Documents/BCCA%20-%20Managing%20Symptom%20and%20Side%20 Effects/Loss_of_Appetite_Patient_Handout.pdf

• BC Cancer Agency Food Ideas to Help with Decreased Appetite:

http://www.bccancer.bc.ca/coping-and-support-site/Documents/Support%20Programs/ FOODIDEASTOHELPWITHDECREASEDAPPETITE2012.pdf

• Cancer Care Ontario: Loss of Appetite: https://archive.cancercare.on.ca/common/pages/UserFile.aspx?fileId=357465 • Canadian Cancer Society – Managing Side Effects: Loss of Appetite:

http://www.cancer.ca/en/cancer-information/diagnosis-and-treatment/managing-side-effects/loss-of-appetite/ Resources for the management of fatigue

For nurses:

• BC Cancer Agency Fatigue and Anemia Symptom Management Guideline:

http://www.bccancer.bc.ca/nursing-site/Documents/6.%20Fatigue%20and%20Anemia.pdf • Canadian Association of Psychosocial Oncology (CAPO) algorithm for cancer-related fatigue:

https://www.capo.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Algorithm-for-Screening-and-Assessment-for-fatigue.pdf For patients:

• BC Cancer Agency – Managing Symptoms & Side Effects: Fatigue:

http://www.bccancer.bc.ca/health-info/coping-with-cancer/managing-symptoms-side-effects/fatigue

• Cancer Care Ontario: How to Manage your Fatigue: https://www.cancercareontario.ca/en/symptom-management/3991 • Canadian Cancer Society – Managing Side Effects: Fatigue:

http://www.cancer.ca/en/cancer-information/diagnosis-and-treatment/managing-side-effects/fatigue other resources for both nurses and patients

• Canadian MPN Group: http://www.mpncanada.com • Canadian MPN Network: http://canadianmpnnetwork.ca

• Canadian Association of Psychosocial Oncology: https://www.capo.ca/about-capo/ • Cancer and Work: https://www.cancerandwork.ca/

cONFlict OF iNterest

Sabrina Fowlkes has received honoraria from Novartis for speaking engagements, education program development and as a nurse consultant. Cindy Murray has received honoraria from Novartis for educational purposes. Adrienne Fulford has

received honoraria from Novartis for speaking and a consultancy meeting. Tammy DeGelder has received honoraria from Novartis for speaking, education and consultancy. Nancy Siddiq has received honoraria from Novartis for educational activities. None of the authors received remuneration for writing of this article.

reFereNces

BC Cancer Agency. (2005). Nutritional Guidelines for Symptom Management: Early Satiety. Available online at http://www.bccancer. bc.ca/nutrition-site/Documents/Symptom%20management%20 guidelines/EarlySatiety.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013). Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/cfs/management/ treating-symptoms.html

Cervantes, F. (2011). How I treat splenomegaly in myelofibrosis. Blood Cancer Journal, 1(10), e37.

Emanuel, R.M., Dueck, A.C., Geyer, H.L., Kiladjian, J.J., Slot, S., Zweegman, S., te Boekhorst, P.A., … Mesa. R.A. (2012). Myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN) symptom assessment form total symptom score: prospective international assessment of an abbreviated symptom burden scoring system among patients with MPNs. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 30(33), 4098–4103.

Geyer, H.L., Dueck, A.C., Scherber, R.M., & Mesa, R.A. (2015). Impact of inflammation on myeloproliferative neoplasm symptom development. Mediators of Inflammation, 2015, 284706.

Harrison, C., Kiladjian, J.J., Al-Ali, H.K., Gisslinger, H., Waltzman, R., Stalbovskaya, V., McQuitty, M., … Barosi, G. (2012). JAK inhibition with ruxolitinib versus best available therapy for myelofibrosis.

New England Journal of Medicine, 366(9), 787–98.

Harrison, C.N., Vannucchi, A.M., Kiladjian, J.J., Al-Ali, H.K., Gisslinger, H., Knoops, L., Cervantes, F., … Barbui, T. (2016). Long-term findings from COMFORT-II, a phase 3 study of ruxolitinib versus best available therapy for myelofibrosis. Leukemia, 30,

1701–1707.

Hermouet, S., Bigot-Corbel, E., & Gardie B. (2015). Pathogenesis of myeloproliferative neoplasms: Role and mechanisms of chronic inflammation. Mediators of Inflammation, 2015, 145293.

Howell, D., Keshavarz, H., Broadfield, L., Hack, T., Hamel, M., Harth, T., Jones, J., … Ali, M, on behalf of the Cancer Journey Advisory Group of the Canadian Partnership Against Cancer. (2015). A Pan Canadian Practice Guideline for Screening, Assessment, and Management of Cancer-Related Fatigue in Adults Version 2-2015, Toronto: Canadian Partnership Against Cancer (Cancer Journey Advisory Group) and the Canadian Association of Psychosocial Oncology, April 2015.

Mesa, R.A., Gotlib, J., Gupta, V., Catalano, J.V., Deininger, M.W., Shields, A.L., Miller, C.B., … Verstovsek, S. (2013). Effect of ruxolitinib therapy on myelofibrosis-related symptoms and other patient-reported outcomes in COMFORT-I: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 31(10), 1285–1292.

Mesa, R., Miller, C.B., Thyne, M., Mangan, J., Goldberger, S., Fazal, S., Ma, X., … Mascarenhas, J.O. (2016). Myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) have a significant impact on patients’ overall health and productivity: the MPN Landmark survey. BMC Cancer, 16, 167.

Mesa, R.A., Niblack, J., Wadleigh, M., Verstovsek, S., Camoriano, J., Barnes, S., Tan, A.D., … Tefferi, A. (2007). The burden of fatigue and quality of life in myeloproliferative disorders (MPDs): An international internet-based survey of 1179 MPN patients. Cancer, 109(1), 68–76.

Mesa, R.A., Scherber, R.M., & Geyer, H.L. (2015). Reducing symptom burden in patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms in the era of Janus kinase inhibitors. Leukemia & Lymphoma, 56(7), 1989–1999.

Michiels J.J. (2016). Signs and symptoms of myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN), quality of life, social activity, work participation and the impact of fatigue in Dutch MPN patients: A one-country questionnaire investigation of 497 MPN patients. Journal of Hematology and Thromboembolic Diseases, 4, 241.

Mughal, T.I., Vaddi, K., Sarlis, N.J & Verstovsek, S. (2014). Myelofibrosis-associated complications: pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and effects on outcomes. International Journal of General Medicine, 7, 89–101.

Neben-Wittich, M.A., Brown, P.D., & Tefferi, A. (2010). Successful treatment of severe extremity pain in myelofibrosis with low-dose single-fractionradiation therapy. American Journal of Hematology, 85(10), 808–810.

Radia, D., & Geyer, H.L. (2015). Management of symptoms in polycythemia vera and essential thrombocythemia patients.

Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program, 2015, 340–348. Saini, K.S., Patnaik, M.M., & Tefferi, A. (2010). Polycythemia

vera-associated pruritus and its management. European Journal of Clinical Investigation, 40(9), 828–834.

Scherber, R., Dueck, A.C., Johansson, P., Barbui, T., Barosi, G., Vannucchi, A.M., Passamonti, F., … Mesa, R.A. (2011). The Myeloproliferative Neoplasm Symptom Assessment Form (MPN-SAF): International prospective validation and reliability trial in 402 patients. Blood, 118(2), 401–408.

Scherber, R.M., Kosiorek, H.E., Senyak, Z., Dueck, A.C., Clark, M.M., Boxer, M.A., Geyer, H.L., … Mesa, R.A. (2016). Comprehensively understanding fatigue in patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms. Cancer, 122, 477–85.

Vannucchi, A.M., Kiladjian, J,J., Griesshammer, M., Masszi, T., Durrant, S., Passamonti, F., Harrison, C.N., … Verstovsek, S. (2015). Ruxolitinib versus standard therapy for the treatment of polycythemia vera. New England Journal of Medicine, 372(5), 426–435.