MICHAEL K. CHAPKO, PHD, PETERMILGROM, DDS, MARILYN BERGNER, PHD, DOUGLAS

CONRAD, PHD,

AND NICHOLAS SKALABRIN, DDSAbstract: One hundred and twenty-sixdentaloffices in

Wash-ington Statekeptarecordof each timeanexpandedfunctionwas

performed bythe dentist, hygienist, or assistant. There were five

two-weekrecording periodsstartinginFebruary1979andendingin

February 1981. Consistent with increasing productivity, dentists

mostfrequently delegatetaskstodental assistants rather thandental

hygienists and delegate an individual task consistently if it is

Introduction

TheWashington State DentalAuxiliariesProject

exam-ined the impactofdelegating expanded functions todental assistants and dental hygienists in 126 private dental

prac-tices. Otherpapers havereported on the

economic,

patientandjob satisfaction, and quality ofcare

findings

from the project. 1.2 The averagepracticehad 1.58full-time equivalent assistants and .44 full-time equivalent hygienists.' Through delegation, the averagedentistsaved38percentof the totalamountof time that could have been saved the dentist if all

legallydelegatable tasksweredelegated.'Although previous

research indicates that delegation has the potential for

increasing income, leisure, andprofessional esteem,3-6

find-ings from the Washington State Dental Auxiliaries Project

only weakly supported suchrelationships.' Delegation was

relatedto agreaternumberof servicesbeingdeliveredbythe practice andtogreater grossincome, butnottogreaternet

income for the dentist. Delegation was weakly related to

hours workedbythedentist. No consistent relationshipwas

observed between delegation and the dentist's satisfaction with professional esteem.

The present paper reports the pattern of delegating individualtasks withinadentalpractice. Onlyafew

publica-tions exist on the extent of delegation in private dental

practices'78and these publicationsfocus onthedifferences betweenhigh and low delegating practices rather thanwhy

some tasks are delegated and others are not. The

litera-ture9'10 on delegation to physician assistants does focus on

thedelegation ofindividualprocedures.Physiciansaremore

willingtodelegateclerical rather than technicaltasks," and patients with less serious presenting complaints and fewer

diagnoses.'0'2 There are, however, two important

distinc-tions between what may be delegatedtophysician assistants anddental auxiliaries: 1)diagnosisis specifically prohibited

fordentalassistantsanddentalhygienists;and2)irreversible

tasks arelimitedtothe dentist. This means thatatleastone task limited to the dentist is required to complete most procedures. In Washington State, forexample, a hygienist

may perform most of the tasks necessary for an amalgam restoration: give aninfiltration and block injection, placea

rubberdam, place a matrix orwedge, and place and carve From theDepartments of HealthServicesandofCommunity Dentistry,

University of Washington. Address reprint requests to Dr. Michael K.

Chapko, DepartmentofCommunityDentistry, SM-35,University of

Wash-ington, Seattle,WA98195. This paper,submitted to the Journal July 18, 1983, wasrevised and accepted for publication September 3, 1984.

C 1985AmericanJournalofPublic Health0090-0036/85$1.50

delegatedatall.For tasks thatmaybedelegatedto theassistant,a

relationship wasfoundbetween thepercentofdentistsdelegating

anindividal task and the amount of the dentist's time that is freed

through delegating that task. From the perspective of quality of

care, the per cent of dentists who delegate a task was inversely related tothe complexity of the task. (Am J Public Health 1985;

75:61-65.)

the

amalgam. However,

the dentistmust prepare the toothfor the

amalgam.

These restrictions mean that while thephysicianassistant maysubstitute forthephysician,'0"'3the

dentalauxiliary maybe anextender butnot asubstitutefor

thedentist. Since the dentistmustseealmostallpatientsat

each office visit, patient characteristics maybe less

impor-tant in

delegation

decisions within dentistry. Bergner andcolleagues2

report nodifference in age, general oralhealth,

orcomplexity ofthe restoration in patientswhose

restora-tionwas

placed by

ahygienistversuspatientswhoserestora-tion was placed by a dentist. Examination offactorsother

than patientcharacteristics which influence adentist's

will-ingnessto delegate individual tasks mayhelptoexplain the lack of

high

delegation in most practices and thevariability

indelegation betweenpractices.Sincedentistsarerestrictedin most casesfrom

delegat-inganentireproceduretotheauxiliary, theymustfind other

meansofefficiently delegating. Threeprinciples of

efficient-ly delegating individual tasks are: 1) tasks which save the dentist the most time should be delegated; 2) if a task is

delegateditshouldbedelegatedconsistently; and 3) the task shouldbedelegatedtotheleastexpensive auxiliary, i.e., the assistant rather than thehygienist. This paper willexamine

the degree to which these principles are employed

by

dentists and the degree to which quality ofcare

consider-ationstemper theapplication of these

principles.

Methods

TheWashington State Dental Auxiliaries Project

exam-ined private practices selected from those in which the dentistworked more than 20hours per week, was ingeneral

practice, had more than one operatory, and did not share incomewith anotherdentist. The 1,013 practices whichmet

these criteria were stratified by number of operatories and

region ofthe state. Participating practices were randomly

sampled from thesestrata.One hundred twenty-sixpractices

agreedtoparticipatein 1979.One hundred thirteenpractices

remained in thestudyuntil it ended in 1981.

Datanecessarytodetermine the degree of delegation in

a practice were collected during five two-week periods in February 1979, August 1979, February 1980, August 1980,

and February 1981. Datawere supplied by the practiceon

operatory logs. One log was completed for each patient.

Eachlogindicated whether the dentist, the hygienist,and/or

the assistant performed the expanded functions. The logs

alsocontained information regarding proceduresperformed

for the patient and when the dentist or a staff member

manual and a three-hour in-office training session for data collection.

Estimates of the time it takeadentisttoperform each of

the 32expandedfunctions identified in theWashingtonState

DentalPractice Act were obtained from three sources: the

operatorylogs kept byparticipating practices (20 expanded functions); previouslypublished times (five expanded

func-tions);7'4'15 or estimates made by dentists associated with

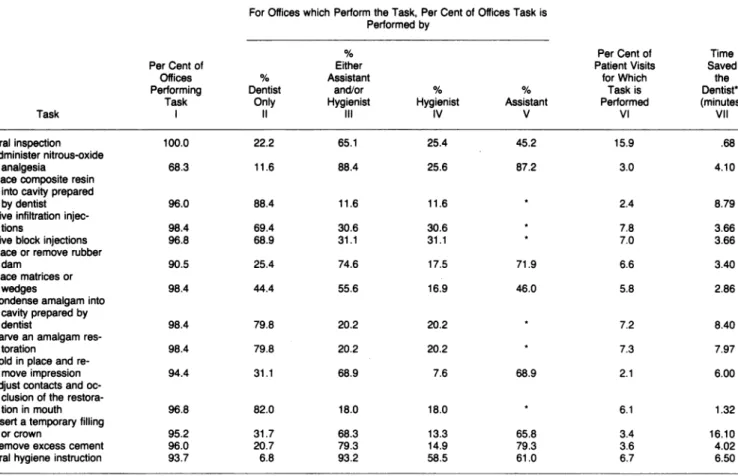

theproject(sevenexpandedfunctions). Prioritywasgivento operatorylogtimes sincethey would be the closesttoactual times for dentists in Washington State. ColumnVIIin Tables

1 and 2 presents the estimate of time saved the dentist for selected expandedfunctions.

Results

Tables 1 and 2 present in column I the percentage of offices in which each taskwasperformed duringthe

Febru-ary 1979 data collection period. These data were obtained

priorto any practice receivingand being influenced bythe continuing education.*

ColumnVIofTables 1and 2presentsthemean percent-ageof patients who received each taskduringthesametime

period. Infrequently performed tasks (see Table 2) are

associated primarily with surgical and orthodontic treat-ment.

*One purpose ofthe project was to. evaluate theeffect of continuing

education.These findings will bereported elsewhere.

Tasks associated with patient examination and oral hygiene are delegated in most practices. Tasks associated with operative dentistry and orthodontics are delegated in fewerpractices. ColumnIIin Tables 1 and 2presents the per cent of practices in which the task is performed by the dentist only, if it isperformed inthatpracticeatall. Column IIIpresents the per centof practices in which each taskwas

delegated at least once to either the assistant or hygienist during the two-week data collection period. Tasks differ greatly intermsof the number of dentists which delegate the tasks to an auxiliary. The mostcommonly delegated tasks include: oral hygiene instruction, nitrous oxide, fluoride treatment, removing excess cement, takingimpressions, oral

inspection, and placing or removing the rubber dam. The least delegated tasks are infiltration or block injections, applying tooth separators, condensing, carving or adjusting amalgams, placing composites, placing of retraction cord,

packing and medicating extracted areas, and fitting

orth-odontic bands.

No relationship was found between the per cent of

dentists delegating a task and the relative time saved the

dentistby delegation (r= .08) orthe skillrank'6of thetask (r

= .09).Asubstantialcorrelation was found between the per

centof dentists delegatingataskand thecomplexityscore'7

of the task (r = .68). Delegation of individual tasks was

foundtobepositivelyrelated (r= .50) to dentists' attitudes toward delegating the tasks as taken from a paper by Koerner and Osterholt.18Thesecorrelations are based upon

TABLE1-PercentageofOffices Delegating Frequently Performed TaskstoDentalAssistantsorHygienistsduringFebruary1979 ForOfficeswhich Perform theTask,PerCent of Offices Taskis

Performedby

% PerCentof Time

PerCent of Either Patient Visits Saved

Offices % Assistant for Which the

Performing Dentist and/or % % Taskis Dentist**

Task Only Hygienist Hygienist Assistant Performed (minutes)

Task II IlIl IV V VI VIl

Oralinspection 100.0 22.2 65.1 25.4 45.2 15.9 .68

Administernitrous-oxide

analgesia 68.3 11.6 88.4 25.6 87.2 3.0 4.10

Placecomposite resin

intocavity prepared

by dentist 96.0 88.4 11.6 11.6 * 2.4 8.79

Give infiltration

injec-tions 98.4 69.4 30.6 30.6 7.8 3.66

Give block injections 96.8 68.9 31.1 31.1 7.0 3.66

Placeor removerubber

dam 90.5 25.4 74.6 17.5 71.9 6.6 3.40

Placematricesor

wedges 98.4 44.4 55.6 16.9 46.0 5.8 2.86

Condenseamalgaminto

cavity prepared by

dentist 98.4 79.8 20.2 20.2 7.2 8.40

Carveanamalgam

res-toration 98.4 79.8 20.2 20.2 7.3 7.97

Holdinplace and

re-moveimpression 94.4 31.1 68.9 7.6 68.9 2.1 6.00 Adjust contacts and

oc-clusionofthe

restora-tion in mouth 96.8 82.0 18.0 18.0 6.1 1.32

Insert a temporaryfilling

orcrown 95.2 31.7 68.3 13.3 65.8 3.4 16.10

Remove excess cement 96.0 20.7 79.3 14.9 79.3 3.6 4.02

Oralhygieneinstruction 93.7 6.8 93.2 58.5 61.0 6.7 6.50

*Thesetasks may not bedelegatedtoanassistant. -Thesearethetimesit takes thedentisttoperform the tasks.

TABLE2-PercentageofOfficesDelegating InfrequentlyPerformed TaskstoDentalAssistantsorHygienistsduringFebruary1979

ForOffices which Perform theTask,Per cent of Offices Task is Performedby

% PerCent of Time

PerCent of Either Patient Visits saved

Offices % Assistant for which the

Performing Dentist and/or % % Task is Dentist"

Task Only Hygienist Hygienist Assistant Performed (minutes)

Task II ll IV V VI VIl

Measureand mark

peri-odontalpockets 38.9 54.4 45.5 41.6 6.5 1.4

Takeimpressionsforstudy

models 31.7 22.1 77.9 14.0 75.6 .7 13.80

Deliversedative capsule 84.1 40.0 60.0 15.0 50.0 .5

Applytooth separators as forplacement ofClassIlIl

goldfoil 81.0 75.0 25.0 0 25.0 .1

Polish restoration 19.8 43.6 56.4 30.7 36.6 1.6 7.41

Acidetch 28.6 55.6 44.4 10.0 37.8 1.3 1.32

Selectshadeand mold 17.5 63.4 36.6 2.9 33.7 1.1 8.00

Take impression for

oppos-ingstudy model 12.7 23.6 76.4 4.5 75.5 1.0 3.22

Placement ofretraction cord 11.1 69.6 30.4 2.7 29.5 1.5 1.53

Removesutures 61.9 41.7 58.3 10.4 52.1 .2 7.27

Packandmedicate

extract-ed areas 71.4 69.4 30.6 0 30.6 .2 7.27

Placeorremoveperiodontal

packs 85.7 55.6 44.4 11.1 33.3 .1 8.00

Applyseparatorsfor

orth-odontictreatment 96.0 40.0 60.0 20.0 40.0 .0

Fit orthodontic bands 92.9 66.7 33.3 0 33.3 .1

Placeorremoveorthodontic

wires 86.5 64.7 35.3 5.9 35.3 .2 5.00

Acid etch and applysealant 72.2 54.3 45.7 11.4 42.9 .2 20.00

*Times couldnot bedetermined forthesetasks becauseofinadequatedata. "Thesearethetimes ittakes thedentisttoperform thetasks.

alltasks.

However,

evenwhen the sixhigh complexity

taskslegally

restricted to thehygienist

areeliminated,

only onecorrelation

changes

appreciably:

the correlation betweendelegation

and relative (column VI times columnVII) timesaved the dentistincreases to .54. In sum,

delegation

wasrelated most strongly to the

complexity

of the task and totime saved the dentist.

For

frequently performed

tasksconsistency

ofdelega-tion

depends

upon the number ofpractices

delegating

thetasks. Tasks thatarenot

delegated

in manyofficesarelikely

tobe

delegated

infrequently

whendelegated atall.Infiltra-tion

injections

exhibit this type of distribution(Figure

1).Tasks that are

delegated

in a large number ofoffices,

however,

exhibit a bimodal distribution. Most practiceseither do not delegate the task, ordelegate it more than 90 per cent of the time.

Taking

impressions

forstudy

models exhibits this type ofdistribution(Figure

1).Some tasks whichare not

consistently delegated

(anes-thetic administration and restorativetasks)

can be legallyperformed

inWashington

State only by thehygienist

(ordentist). Placing

of matrices andwedgesalsoexhibits incon-sistentdelegation

but isperformed

primarily

by assistants. Theconsistently delegated

tasksarepredominantly

delegat-ed to assistants and exhibit bimodal distributions. The

exception

is "measure and mark periodontal pockets"which is predominantly delegated to hygienists. Although

the tasks restricted to hygienists appear to contradict the

consistency

hypothesis,

mosthygienists

are notemployed

full-time,

andconsistency

indelegation

is thereforedifficult.The

frequency

ofdelegation

was also analyzed on a dailybasis. Duringanygiven day the mostcommonpattern isto

delegateatask to thehygienist at least 90 per cent of the time if the taskisdelegatedto thehygienist atallon thatday.

Columns IV and V in Tables 1 and 2 indicate the percentageof practices thatdelegate tasks to the hygienistor

theassistant, respectively. Delegation to the hygienist is less than that to the assistant. Six tasks may not be legally delegated to an assistant so that if they aredelegated atall they must be delegated to the hygienist. Except for the six taskslegally restricted to the hygienist, only "measure and mark periodontal pockets" isdelegated in a larger percent-age of practices to the hygienist comparedto the assistant. Three of the tasks are delegated in approximatelyan equal number of practices to the assistant and hygienist: oral

inspection, polish restoration, and oralhygiene instruction. All of the remaining tasks are delegated in a far greater number of practices to the assistant. These findings are

based upon allpractices and do not take intoaccountthe fact that 46 per cent of the dentists donot employ ahygienist. When the per cent of delegation to the hygienist is based uponpractices which employahygienist, only measure and markperiodontal pockets, orgal inspection, polish

restora-tion,and orgalhygieneinstruction are delegatedmore tothe hygienist than the assistant.

Excluding tasks legally restricted to hygienists, we

found only weak and inconsistent correlations between the relative delegation of an individual task to the hygienist versus the assistant (per cent delegation to the hygienist minuspercentdelegationtotheassistant)andtask complex-ity (r = .25) orskill (r = .20).

100 GIVE INFILTRATION INJECTIONS 80- 60- 40- 20-o .01 I1I .21 .31 .41 .51 .61 .71 .81 .91 to10 .20 .30 .40 .50 .60 .70 .80 .90 1.00

Proportion of times taskis delegated

.~80-TAKE IMPRESSIONS FOR STUCYY MODELS

60- 40-

20-0 .01 .11 .21 .3 .41 .51 .61 .1 .8 .9

toO.1 2 3 40 .50 .60 .70 80 90

100U

Prprinof times task is delegated

FIGURE 1-Proportion of Times Task is Delegated duringFebruary 1979

(number oftimes taskisperformedbyanauxiliary/numberoftimestaskis

performedbyanyone)

Discussion

The per cent ofdentistsdelegatingataskwas foundto be related to the complexity of the task and toan indepen-dent measure'8 ofdentists' attitudes toward delegating the task. Both of thesemeasures reflectthe skillrequiredfor the task. For tasks that may be delegated to dental assistants,

delegation was also related to the product of two measures of potential forsavingthe dentist time: dentist time needed to perform the task, and per cent of patients for whom the task is performed. These findings suggest that the dentist takes

intoaccount bothcomplexity andtime saved whendeciding

which tasks todelegate.

Dentists need tofeelmorecomfortableaboutdelegating highlycomplex tasks before they will bedelegated to auxilia-ries. Additional

auxiliary

training with specified standards ofperformance would help. In 1979, almost one-half of the

assistants studied had noformal training inexpanded func-tions. A related problem is assistantturnover. The average

lengthofemploymentwas 2.3 years with a yearlyturnover

rate ofalmost 40 per cent. Increased staffstability would contribute to thewillingnessofdentiststo train staffand the resultingconfidence in staff.

The pattern ofdelegation for assistant tasks indicates

that the mostfrequentmode ofdelegatingistoconsistently delegate the task ifit is delegated at all. This is congruent

with the finding that delegation to assistants increases the

productivity of the

practice.'1'9

Routine delegation of these tasks suggests a protocol fordelegationand is aidedby the continual presence ofassistants.For theexpandedfunctionslegallyrestrictedto hygien-ists(Table 1), theoverall mode is eithernot todelegatethe taskortodelegate inconsistently. The dentistperformsthe

task most

frequently

in most practices. The inconsistentdelegation of taskstothehygienistisprobablyrelatedtothe lackof full-timeemployment ofahygienistinmostpractices

and aconflict with thehygienist's traditional role of perform-ing oral prophylaxis. Ourdataindicate that it iscommonfor specific days to be set aside for the hygienist to perform tasks related to operative dentistry. On other days, the hygienist either does oral prophylaxis oris not working in theoffice. Withina single day,

delegation

tothehygienistis quite consistent.Withafewexceptions,wefound that taskswhichcould be legallydelegatedto either the assistantorhygienistwere

delegated tothe assistantmore frequently. However,there stillwas somedelegationtohygienistswhich variedbytask. Since thehygienistis themorehighlytrainedauxiliary, one

would expect the morecomplex taskstobedelegatedtothe hygienist morefrequently thansimplertasks. Thiswas not

observed inourdata. Delegation tothehygienistishighfor procedures which are frequently performed in conjunction

with an oral prophylaxis, i.e., oral inspection and oral

hygieneinstruction. Delegation of these taskstothe

hygien-ist is reasonable because the tasksareshort andare

integrat-ed into a series of other tasks performed by the hygienist.

Delegationto the assistant woulddisruptthe flow of work. This same principle may be used to explain why placing matrices orwedges and acid etcharemorefrequentlydone

by the dentist than placing or removing a rubber dam and removingexcess cement.

State practiceacts set aceilingonthe number of tasks which may be delegated. Data from the Washington State Dental Auxiliaries Project indicate that dentists in general practicedelegate, onaverage, 38per centof what ispossible

in Washington State. Factors such as the availability of auxiliaries with adequate skills, dentists' attitudes and man-agement skills, increased costs, the low frequency with which many tasks are performed, and an adequate flow of

patientsmay act as anaturalceilingondelegation.Itshould

not be assumed that reducing the legal restrictions on

delegation will produce a dramatic change in the output of the dental healthdeliverysystem. Likewise,comparisons of the restrictiveness of state dental practice acts,20* based

uponthe assumption that all prescribed tasks will be

maxi-mally delegated, will overestimate the differences between

states.

*SavingTR,etal:Labor-Substitutionand the EconomicsoftheDelivery ofDental Services. FinalReport, DHEWContractNo.HRA-231-77-01325,

September30, 1978.

REFERENCES

I. MilgromP, Bergner M, Chapko M, Conrad D, Skalabrin N: The Washing-ton State dental auxiliary project: delegating expanded functions in

general practice.J Am DentAssoc 1983; 107:776-781.

2. BergnerM,MilgromP,Chapko M, Beach B,Skalabrin N: The Washing-tonState dentalauxiliary project: quality of care in private practice. J Am Dent Assoc 1983; 107:781-786.

3. Douglass CW, ColeKO: The supply of dentalmanpower in the United

States.J DentEduc 1979; 43:287-302.

4. Douglass CW, LipscombJ:Expanded functiondental auxiliaries: poten-tial for the supply of dental services in a national dental program. J Dent Educ1979; 43:556-567.

5. TaylorLF: The use ofexpanded-duty dental auxiliaries. NZ Dent J1976; 72:143-148.

6. SistyNL,HendersonWG, Paule CL: Review of training andevaluation studies inexpandedfunctions fordentalauxiliaries. J Am Dent Assoc

7. Marcus M, Yee D,Magyar P: DID: adirect measure ofdelegation. J Public Health Dent 1977; 37:23-30.

8. MullinsMR, Kaplan A, BaderJD,LangeKW, Murray BP, Armstrong

SR, Haney CA: Summary results of the Kentucky Dental Practice Demonstration: a cooperativeproject withpracticinggeneraldentists.J Am Dent Assoc 1983; 106:817-825.

9. RecordJC,McCally M,Schweitzer SO,Blomquist RM, Berger BD: New healthprofessionals after a decade and ahalf: delegation, productivity and cost inprimary care. J HealthPolitPolicyLaw1980; 5:470. 10. Crandall LA, Santulli WP, Radelet ML, Kilpatrick KE, Lewis DE:

Physician assistants inprimary care: patient assignment and task

delega-tion. Med Care 1984; 22:268-282.

11. Yankauer A, Connelly JP, Feldman JJ: Physician productivity in the delivery of ambulatory care: some findings from a survey of pediatricians. MedCare 1970; 8:35-46.

12. Ekwo E, Dusdieker LB, Fethke C, Daniels M: Physician assistants in primary care practices: delegation of tasks and physician supervision. Public Health Rep 1979;94:340-348.

13. Miles DL, Rushing WA: A study of physician's assistants in a rural setting. Med Care 1976; 15:987-995.

14. Mullins MR,Kaplan AL, Mitry DJ,Armstrong SR, Lange KW, Steuer RE,Johnson KH: Production-economics effectsof delegation and prac-tice size in a private dental office. J Am Dent Assoc 1979; 98:572-577. 15. Lotzkar S, Johnson DW, Thompson MB: Experimental program in

expandedfunctions fordental assistants: phase Ibaseline andphase 2 training. J Am Dent Assoc 1971; 82:101-122.

16. Kilpatrick KE, Mackenzie RS, Delaney AG: Expanded-function auxilia-ries in generaldentistry: a computersimulatioh. Health Serv Res 1972; 7:288-300.

17. MullinsMR,KaplanAL,MitryDJ:Effects of expanded function dental

auxiliariesinprivatefee-for-servicedentalpractice. Final summary report (vol 1). Lexington: Department of Community Dentistry, College of

Dentistry, University of Kentucky, October1976.

18. KoernerKR,Osterholt DA: Student surveyreport:Washington dentists questioned on expanded duties. J Am Dent Assoc 1973; 86:995-1000. 19. Lipscomb J,SchefflerRM: Impactof expanded-duty assistants on cost

andproductivityindental caredelivery.Health Serv Res1975;10:14-35.

20. Johnson DW,BernsteinS: Classification of states regarding expanding duties for dentalauxiliaries and selectedaspects of dental licensure-1970. Am JPublic Health 1972; 62:208-215.

Johnson

Foundation

Offers

Faculty

Fellowships

in

Health Care

Financing

TheRobert Wood JohnsonFoundation's Programfor FacultyFellowshipsin HealthCareFinance, established in 1984 to help meet the growing need for university faculty equipped with the skills necessarytoteachandconduct research in thisimportantfield,permits

selected

academicianstostudy andobtain first-hand experienceinthe rapidly changingfield of healthcarefinance, andtoencourageneededresearch. Funded by the Robert Wood JohnsonFoundation,theprogramisadministeredbythe JohnsHopkins Medical Institutions.

Uptosixfellows will be selected in 1985byaNationalAdvisory Committeeof eminent leaders in health management and health care finance. Successful candidates will generally have faculty

appointmentsin universityprogramsanddepartments where there isastronghealthcarefinanceand health policy focus. Stipendsupto $40,000per year, moving expenses, fringebenefits,andadditional

support arefinancedby theFoundation. Thefellowshipconsists of threeparts:

*Educational component-an intensive three-month education program conducted at Johns Hopkins Center for Hospital Finance and Management

*Placement component-a nine-month placement inalargeprivateorpublic healthcarefinancing

organization, major medical center, orhealth maintenance organization

*Research component-grants ofupto $15,000willbe made available in the yearfollowingthe

placement experienceto supportthecompletionof thefellow'sresearchproject. Thefellow's research plan must be approved by the program's National Advisory Committee, and a written commitment obtained from a university offering an appropriate faculty appointment allowing completion of the project.

Applications for the 1985 program are due by January 21, 1985. For applications and further

information, contact: Carl J. Schramm, PhD, JD, Director, Program for Faculty in Health Care Finance, Johns Hopkins Center for Hospital Finance and Management, 624 North Broadway, Hampton House, Baltimore, MD21205. Tel: 301/955-8316.