MPRA

Munich Personal RePEc Archive

Exploring corporate disclosure on climate

change: Evidence from the Greek

business sector

George Halkos and Antonis Skouloudis

Department of Economics, University of Thessaly, Department of

Environment, University of the Aegean

2015

Online at

http://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/64566/

Exploring corporate disclosure on climate change:

Evidence from the Greek business sector

George Halkos

1and Antonis Skouloudis

2 1Laboratory of Operations Research, Department of Economics, University of Thessaly

2

Centre for Environmental Policy and Strategic Environmental Management, Department of Environment, University of the Aegean

Abstract

An increasing number of large corporations around the world engage in accounting for and reporting on their plans and measures towards climate change, as part of their environmental responsibility agenda. Using a disclosure index, this study investigates the status of the disclosure practices of the top 100 companies operating in Greece with respect to the pivotal issue of climate change. Determinants which drive Greek companies to publicly disclose such information are examined while overlapping perspectives for the Greek case are outlined. The analysis suggests that only a small group of leading Greek companies appears to endorse a climate change discourse as an instrument of empowering stakeholders’ decision-making. Most other corporations still tend to disregard disclosure practices of their actions towards this global issue.

Keywords: Climate change; corporate disclosure; corporate social responsibility; content analysis; Greece.

Introduction

Climate change poses potentially unprecedented threats to modern societies

and reflects a much-debated issue as it is strongly interlinked with current lifestyles

and development policies. While scientific assessments suggest that the overall

impact from climate change is most likely unpredictable, they seem to denote that

extreme weather conditions are to be expected among the various geographical

regions in the years to come1. Moreover, such unpredictability refers to significant

changes in the distribution of precipitation, affecting the intensity and frequency of

draughts and floods, severe disease and pest outbreaks and well as widespread fires in

forested areas.

The need for co-ordinated action to mitigate climate change impacts is an

essentially complex public policy problem of modern times; a problem where

meaningful actions from the business community should represent a key component

in shaping effective policy responses and appropriate mitigation measures. Given the

difficulties of the global community in defining concrete ways to confront climate

change, the exploration of the discretionary disclosure of organizational responses to

climate change makes a useful endeavour. Moreover, under the critical circumstances

climate change posits, companies need to maintain the support and approval of their

stakeholders by introducing or refining practices that will counteract possible

legitimacy threats or risks related to climate change.

1. Background and conceptual underpinning

Discretionary corporate climate change disclosure (hereafter CCD) has been

identified as a valuable legitimation instrument which can mitigate conflicts with

1

For information on the dimensions of the problem of climate change and its economic effects see Halkos (2014, 2015).

stakeholders and a practice with a mediating effect in convincing societal members

that the organization is fulfilling their expectations (Dowling and Pfeffer, 1975;

Lindblom, 1994). The concept of legitimacy according to Dowling and Pfeffer (1975,

p.122) is defined as “a condition or status which exists when an entity’s value system

is congruent with the value system of the larger social system of which the entity is a

part’ and add that ‘when a disparity, actual or potential, exists between the two value

systems, there is a threat to the entity’s legitimacy”.

Legitimacy theory posits a systems-oriented perspective to the

business-and-society relationship, where the firm influences and is influenced by the social context

within it operates. It sets forth a form of a ‘social contract’ where society provides the

company with a range of resources to conduct its activities along with an overarching

‘licence to operate’, in return for the provision of socially acceptable (i.e. legitimate)

business conduct (Mathews, 1993; Deegan, 2002). Whenever the organization’s

operation is not meeting the society’s set of norms and values then the latter can

revoke its ‘licence’ and for the firm to retain its legitimacy practical demonstrations

of adherence to such expectations are essential.

According to Gray et al. (1987), such disclosure practice refers to “the process

of communicating the social and environmental effects of organizations (particularly

companies) beyond the traditional role of providing a financial account to the owners

of capital, in particular shareholders. Such an extension builds upon the assumption

that companies do have wider responsibilities than simply to make money for their

shareholders” (Gray et al., 1987, p. 9). In line with the multidimensionality of the

corporate social responsibility (CSR) construct, CCD encompasses a diverse range of

information, including vision and strategic posture to address climate change, risks

operational impact and control emissions, quantitative information of greenhouse gas

emissions, voluntary initiatives to reduce emitted greenhouse gases, etc.

A considerable number of the largest corporations around the world adds

emphasis and allocates resources towards climate change mitigation plans and

measures (Carbon Disclosure Project, 2013). In this respect, corporations are called

upon to shape voluntary disclosure practices for such courses of action in order to

address potential legitimacy deficits (Kolk, 2008). Indeed, the overlapping and

multifaceted impacts of climate change are acknowledged as significant and

far-reaching for business (Business Roundtable, 2007). Still, relevant corporate

communication channels which incorporate such considerations leave much to be

desired with Doran et al. (2009) to indicate that a mere 24% of the Standard and

Poor’s (S&P) 500 companies referred to climate change in their SEC filings.

CCD has received increased attention in the academic literature with a

growing number of empirical studies to explore this aspect of corporate

accountability. In this regard, two dominating groups of research streams are

identified. A considerable number of scholars focus on trends and patterns of CCD in

specific national-regional and/or industries while another group of studies attempts to

shed light on determinants and predictors of CCD (e.g. Stanny and Ely, 2008;

Freedman and Jaggi, 2009).

With this in mind, this study aims to contribute to the literature by shedding

light on the comprehensiveness of CCD by large firms in Greece and investigate a

number of determinants of such disclosures.

Next, the research questions of the study are described along with the methods

employed and the sample identification. The following section presents the analysis

of data and relevant findings. In the final section, implications are discussed and

2. Research questions

Prior research suggests a positive relationship between corporate size and the

extent to which corporations disclose information (Ahmad et al., 2003; Freedman and

Jaggi, 2009; da Silva Monteiro and Aibar-Guzmán, 2009; Stanny and Ely, 2008).

Larger organizations encapsulate high public visibility and significant social and

environmental impacts (Watts and Zimmerman, 1986). They also have more

resources to invest in CCD (Belal, 2001) and aim to present a positive image towards

their stakeholders. Therefore, we hypothesize that CCD of Greek firms is dependent

on organizational size.

Literature also suggests a strong industry effect on environmental and social

disclosure. In particular, companies in the mining, oil and chemical sectors seem to

disclose more information regarding environmental management and employees’

health and safety measures (Line et al., 2002), while the financial sector, and the

tertiary-service sectors in general, seem to give more emphasis to labor practices,

product responsibility and broader social issues (Line et al., 2002).

In addition, corporations in sectors with high environmental sensitivity tend to

disclose more information regarding their environmental performance than others

(Hackston and Milne, 1996; Patten, 1991; Roberts, 1992; Ahmad et al., 2003; da

Silva Monteiro and Aibar-Guzmán, 2009). Finally, business organizations with high

proximity to the final consumer (i.e. companies of the banking, retailing, utilities or

food and beverages sector) are expected to provide more non-financial information in

general (Arulampalam and Stoneman, 1995), since promoting a positive corporate

image that assures responsible conduct, increases brand loyalty and motivates

consumers to buy products of the specific brand (Meijer and Schuyt, 2005). Thus, we

postulate that CCD of Greek firms varies by business sector and that Greek

We also postulate that Greek companies with high proximity to the final consumer

will provide more CCDs.

Prior findings on the relationship between business profitability and

non-financial disclosure are ambiguous (e.g. Belkaoui and Karpik, 1989; Patten, 1991;

Roberts, 1992). Nevertheless, increased profitability can have a direct effect on the

extent of environmental and social disclosure (Bo, 2009). Supporting arguments for

this claim point out that a profitable organization is more exposed to social scrutiny

(Ng and Koh, 1994), and is most likely managed by skilled and insightful executives

who can potentially foresee the benefits of social responsiveness (Belkaoui and

Karpik, 1989), but mostly that it has the available economic resources to engage in

voluntary disclosure (Hackston and Milne, 1996; Roberts, 1992). Thus, we postulate

that CCD of Greek firms is dependent on profitability.

Chapple and Moon (2005) argue that the level of internationalization of a firm

can lead to increased CSR and, in our case, to increased CCD efforts. They denote

that “...as businesses trade in foreign countries, they see the need to establish their

reputations as good citizens in the eyes of new host populations and consequently will

engage in CSR as part of this process” as well as that “...the emerging systems of

world economic governance create incentives for greater CSR” (p. 419). In a similar

vein, Cooke (1989) and Tang and Li (2009) stress that a firm’s presence in foreign

markets postulates that it is bound to disclose more comprehensive information in line

with the reporting rules of the foreign business system. In addition, Robb et al. (2001)

offer empirical support that international presence can be a strong determinant for

non-financial disclosure. In line with these arguments, we explore the hypothesis that

CCD of Greek firms depends on their level of internationalization.

Isomorphic patterns and mimetic processes as reflected in the subscription to

Powell, 1983; Matten and Moon, 2008) have a mediating role in the non-financial

disclosure practices of firms. In this context, the growing number of stand-alone CSR

reports in Europe (KPMG, 2013) has been identified as a marking example of such

processes in the homogenization of institutional environments across national

boundaries (Matten and Moon, 2008: p. 412). In view of the above, we hypothesize

that Members of the Hellenic CSR Network and the Greek Business Council for

Sustainable Development provide more CCDs.

Secchi’s (2006) evidence from Italy reveals that there is heterogeneity in the

non-financial reporting practices of government-owned and privately-owned firms. In

this respect, the size of the (notably larger) strongly bureaucratic, centralized public

sector in Greece has aggravated calls for new public management techniques

(Phillipidou et al., 2004). Yet, efforts towards the modernization of the state are

admittedly slow and previous transformational processes have proved unsuccessful

(Kufidou et al., 1997; Philippidou et al., 2004). Key factors for such failure include

Greek state organizations’ resistance to change, the myopic focus on regulations, the

absence of robust strategic planning, the lack of employee motivation and stimuli to

undertake initiatives in order to offer and apply new thinking in the organization

(Ministry of Internal Affairs, 2000 in Phillipidou et al., 2004: p. 324).

Moreover, according to preliminary arguments and tentative findings

(Tsakarestou, 2004; Hackston and Milne, 1996; Tang and Li, 2009), it is reasonable

to hypothesize that subsidiaries of foreign multinationals (MNCs), which have

adopted a robust CSR agenda, can act as moral agents in the country and will be more

active in non-financial disclosure than those companies headquartered within the

country.

Finally, companies listed on the Athens Stock Exchange (ASE) constitute ‘the

and form an essential driving force of the domestic economy via their linkages with

other, non-listed, enterprises. These firms are not only well-known to the financial

and business analysts’ community, but they tend to draw more public attention and

receive more extensive media coverage than unlisted firms (Branco and Rodrigues,

2006; Halkos and Sepetis, 2007). Given these, we explore that CCD of Greek firms

varies by ownership identity and if Greek government-owned and government-linked

corporations provide less CCDs. Similarly we investigate whether subsidiaries of

foreign MNCs provide more CCDs and if companies listed on the Athens Stock

Exchange provide more CCDs.

In view of the above, our study is guided by the following research questions:

a) Is CCD a common practice among large Greek corporations? and

b) Do organizational parameters such as those described in this section affect CCD?

3. Material and methods

The sample used in this study consists of the 100 largest companies operating

in Greece (based on annual revenues) according to the ICAP’s annual “Greece in

Figures” report. Out of the companies in question, 32% belong to the manufacturing

sector, followed by firms engaged in trade/retail activities (31%), the

banking-insurance sector (12%) and the utilities sector (11%). No other business sector

yielded more than 10% of the sample (construction and building materials firms

represent 6% while firms pertaining to other tertiary/service sectors represent 9% of

the sample). Moreover, 36% of the firms are listed in the ASE, 7% are

government-owned, and 29% are privately-owned while 28% are subsidiaries of foreign

multinationals.

In order to explore the publicly available CCDs, a web-based search was

performed during the first quarter of 2011, locating the official websites of the sample

press releases, webpages, etc.) was identified. In cases of annual, stand-alone,

non-financial reports (environmental, health and safety, CSR and/or sustainability), the

most recent one was included in the analysis. Among the 100 corporate websites, one

was under construction while three foreign subsidiaries redirected interested parties to

the global website of the parent company.

CCD is assessed according to a numerical grading scheme where zero

corresponds to non-disclosure and 1 stands for organizations disclosing information

on internally adopted and implemented policies, plans and/or programs towards

climate change mitigation. A number of independent variables are used in this

empirical analysis. Specifically, company size is measured by the number of

employees and turnover2. Business sector is measured by a six-scale dummy variable

pertaining to the segmentation of the top Greek firms presented in the sample’s

description. Profitability is measured using return on assets (ROA), return on equity

(ROE) and net profit margin3. Internationalization is operationalized by the

percentage of sales exported to other countries as well as by the number of countries,

besides Greece, where the organization operates. Environmental sensitivity, consumer

proximity and subscription to CSR initiatives are also expressed by a binary zero/one

dummy variable, where one designates a company falling in these categories and zero

if it is does not. Ownership identity is measured by a four-scale dummy variable

pertaining to the segmentation of the top Greek firms presented in the sample’s

description.

2

Turnover is defined as the income that a company generates from its business activities.

3

ROA is calculated as the ratio of the profit (loss) before tax over the average total assets in time t and t-1. It calculates the yield of total assets of a corporation providing a possible criterion for the evaluation of the management tasks achieved. ROE is calculated as the ratio of the profit (loss) before tax over the average equity in time t and t-1. It shows the profitable capability of the corporation and estimates the efficiency with which the corporation exploits its equity. Similarly As expected there was a very high correlation between ROA and ROE and thus we omitted this ratio from our analysis. Similarly the ratio of net profit margin for a corporation is usually expressed as the ratio of net profits over revenues showing what portion of each earned € by the company ends up to profits.

3.1 The proposed econometric model formulation

In our model formulation we treat the dependent variable climate change

disclosure (CCD, Yi) as a dichotomous variable taking the value of 1 (organizations

disclose brief or extensive coverage on specific topics) with probability Θ and the

value of 0 (non-disclosure) with probability 1-Θ.4 This random variable has a discrete

probability distribution:

Pr (Yi , Θi ) = Θi Θ

Yi(1− )1−Yi (1)

With likelihood function:

L(Y;β) = e e X i n X i n ij j k j ij j k (β ) β β 0 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 + = + = = = ∑ + ∑

∏

∏

(2)Apart of the estimation of the slopes in the logistic regression model

formulation we also calculate the connection between the independent variables and

the dependent entailing the Odds Ratio (OR) parameters. These are identified as the

ratio of the probability that CCD will occur (event E that Y=1) divided by the probability that CCD will not occur (1- event E). That is:

Odds (EX1, X2, …, Xn) = Pr( ) Pr( ) E E 1− (3)

In this way the form of the logistic model is defined as

logit [Pr(Y=1)]=loge[odds (Y=1)]=loge

Pr( ) Pr( ) Y Y = − = 1 1 1 (4) 4

4. Empirical results

4.1 Descriptive statistics

As concerns the CCD behavior on behalf of the companies operating in

Greece, the descriptive analysis of our sample shows that the sizable majority of the

companies (74%) take no measures at all for disclosure, with only a 26 of the

organizations disclosing information. It is obvious from the above that the dialogue

potential CCD encapsulates is not utilized effectively to enable and stimulate a

fruitful component of corporate non-financial accountability. Quantitative

information in terms of performance indicators (e.g. direct and indirect greenhouse

gas emissions or CO2 reductions achieved over the reporting period) is very little,

mostly located in CSR reports and absent from annual reports and investor relations

statements.

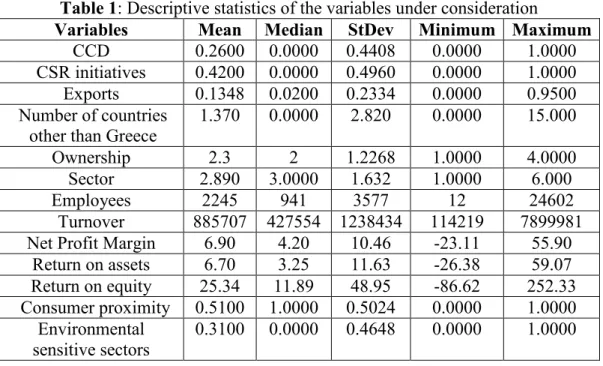

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics of the variables used in our empirical

analysis.

Table 1: Descriptive statistics of the variables under consideration

Variables Mean Median StDev Minimum Maximum

CCD 0.2600 0.0000 0.4408 0.0000 1.0000 CSR initiatives 0.4200 0.0000 0.4960 0.0000 1.0000 Exports 0.1348 0.0200 0.2334 0.0000 0.9500 Number of countries

other than Greece

1.370 0.0000 2.820 0.0000 15.000

Ownership 2.3 2 1.2268 1.0000 4.0000 Sector 2.890 3.0000 1.632 1.0000 6.000 Employees 2245 941 3577 12 24602

Turnover 885707 427554 1238434 114219 7899981 Net Profit Margin 6.90 4.20 10.46 -23.11 55.90

Return on assets 6.70 3.25 11.63 -26.38 59.07 Return on equity 25.34 11.89 48.95 -86.62 252.33 Consumer proximity 0.5100 1.0000 0.5024 0.0000 1.0000 Environmental sensitive sectors 0.3100 0.0000 0.4648 0.0000 1.0000

4.2 Econometric results

For our research, the model specification is:

logit[Pr(Y=1)] = f (size, sector, profitability, environmental sensitivity, consumer

proximity, internationalization, ownership identity, subscription

to CSR initiatives)

where Y is our dichotomous-choice dependent variable CCD with zero corresponding

to non-disclosure and 1 to organizations providing disclosures on climate change

mitigation. This dependent variable depends on a number of explanatory variables.

Namely, number of employees, turnover, sector, return on equity, return on assets, net

profit margin, internationalization, environmental sensitivity, consumer proximity,

exports, subscription to CSR initiatives and ownership identity.

In Table 2, columns 2-3 refer to the full model while columns 4-5 present the

final model consisting of the statistically significant variables and represented as:

logit[Pr(Y=1)] = β0 +β1 (subscription to CSR initiatives) +β2 (sector) +β3 (turnover) +

+β4 (return on assets) +β5 (consumer proximity) +β6 (environmentally

sensitive sectors) +β7 (number of countries other than Greece) + εi

where εi is the disturbance term with the usual properties.

As shown in Table 2, the coefficients have the expected signs. All variables affect

positively while sector and ROA affect negatively CCD. The magnitude of

subscription to CSR initiatives, consumer proximity and environmental sensitive

sectors are quite high while on the other hand the magnitude of turnover is negligible.

The constant term and the variables subscription to CSR initiatives and turnover

are significant in all significance levels (0.01, 0.05 and 0.1) in both model formulations. The variables sector and ROA are significant in the statistical level of 0.1 in both model formulations. The variable number of countries other than Greece is statistically

variables consumer proximity and environmentally sensitive sectors are statistically

insignificant in this model formulation. However they are both significant in the

statistical level of 0.1 in the second model formulation. The variables exports and ownership were statistically insignificant in both model formulations and were

omitted.

Table 2: Econometric results of the proposed logit model formulations

Logit models

Variables Estimates Odds

Ratios Estimates Odds Ratios Constant -3.6882 [0.005] 0.02502 -3.5909 [0.004] 0.0276 Subscription to CSR initiatives 2.04485 [0.005] 7.728 2.228 [0.002] 9.2815 Sector -0.511 [0.073] 0.5999 -0.5086 [0.056] 0.6013 Turnover 0.0000014 [0.009] 1.000 0.0000015 [0.004] 1.000 Return on Assets -0.0687 [0.078] 0.9336 -0.0674 [0.068] 0.9349 Consumer Proximity 1.7258 [0.133] 5.6168 1.9014 [0.077] 6.6951 Environmentally sensitive sectors 1.6523 [0.133] 5.2190 1.7565 [0.091] 5.7918 Number of countries

other than Greece

0.2484 [0.019] 1.2820 Pseudo R2 0.48 0.44 LR χ2(7) χ2(6) 55.25 [0.000] 49.74 [0.000] Log Likelihood -29.682 -32.434 Hosmer Lemeshow 3.89 [0.867] 2.60 [0.957}

The estimated adjusted odds ratio for the variables subscription to CSR

initiatives, consumer proximity and environmentally sensitive sectors are 9.28, 6.695 and 5.792 respectively. This implies that the odds are about 9.3, 6.7 and 5.8 times higher

for a corporation which provides disclosures on climate change mitigation.

The percentage change in the odds

π

= == Pr( ) Pr( ) Y Y 1

0 for every 1 unit in Xi holding

all other X’s fixed can be also computed. For instance, in relation to sector the odds

the odds from a unit change in ROA is negligible (0.7%) while there is no change in

the case of organizational size expressed by turnover.

The overall significance of the models is given by X2 values equal to 55.25

and 49.74 with significance levels of P=0.000 in both cases and 7 and 6 degrees of

freedom for the first and second model formulation respectively. Based on this value

we can reject H0 (where H0: β1= β2=…=β7=0 and H0: β1= β2=…=β6=0) and conclude

that at least one of the β coefficients is different from zero (Χ20.05,7=14.067 and

Χ20.05,9=12.592). The Hosmer and Lemeshow values equal to 3.89 and 2.60 (with

significance equal to 0.867 and 0.957) for the first and second model respectively.

The non-significant X2 value indicates a good model fit in the correspondence of the

actual and predicted values of the dependent variable.

5. Concluding remarks and policy implications

In our research effort we have tried to relate CCD with a number of

explanatory factors like size, sector, profitability, environmental sensitivity, consumer

proximity, internationalization, ownership identity and subscription to CSR

initiatives. Presenting them in order of their magnitudes, we found that subscription to

CSR initiatives, consumer proximity as well as environmentally sensitive sectors, are significant variables affecting positively CCD. In contrast, sector and profitability (expressed by return on assets) have a significant negative effect on CCD while size

(expressed by turnover) has a positive yet negligible effect. Internationalization, expressed by the number of countries other than Greece that the company operates, and exports along with ownership identity seem to have no significant influence.

Deegan et al. (2002) assert that “where there is limited concern, there will be

limited disclosures” (p.335). In this respect, our findings suggest that Greek

sub-group of Greek firms actively engaged in the endorsement of CCD practices,

most other assessed corporations tend to treat such accountability perspectives

superficially and in a ‘window-dressing’ manner, offering primarily self-laudatory

information. Given that gathering and sharing climate change information can be

conceived as a reflection of a firm’s related performance as well as a useful ‘proxy’ to

assess it (Snider et al., 2003), most assessed firms appear to undertake inadequate

actions towards the identification of their exposure to climate change risks and

implicit opportunities.

Such information deficit fails to inform stakeholders’ decision-making and

adds very little to environmental policy and planning. Yet, domestic market forces

(suppliers, customers, investors, creditors, etc.) and bottom-up pressures (from civil

society actors and the wider public) in challenging the environmental accountability

of business have so far been weak and sporadic in Greece. Awareness, interest and

knowledge in environmental management are low (Kassolis, 2007) while ‘domestic

mobilization’ (Börzel, 2003) has generally been slack. Stakeholders’ demands and

expectations have so far proved to be moderate in stimulating the Greek business

community towards consistent environmental reporting and meaningful

environmental management.

Future research should investigate CCD in other national contexts using more

detailed content analysis approaches. Moreover, longitudinal analysis of CCD could

contribute in examining whether and how the recent economic downturn affected the

climate change discourse of corporations. Finally, action research and qualitative

evidence could shed light on where climate change stands among the various

corporate reporting aspects and, ultimately, provide additional insights into factors

References

Agresti A. (2012). Categorical Data Analysis, 3rd edition, Wiley.

Ahmad Z., Hassan S. and Mohammad J. (2003). Determinants of Environmental Reporting in Malaysia, International Journal of Business Studies, 11, 69-90.

Arulampalam W. and Stoneman P. (1995). An investigation into the givings by large corporate donors to UK charities: 1979–86, Applied Economics, 27, 935-945. Belal A.R. (2001). A study of corporate social disclosures in Bangladesh, Managerial

Auditing Journal, 16, 274-289.

Belkaoui A. and Karpik P. (1989). Determinants of the corporate decision to disclose social information, Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 2, 36-51.

Bo W. (2009). Financial performance impacting on CSR disclosure - evidence from listed companies in 2006, Friends of Accounting, 12, 88-90.

Börzel T.A. (2003). Environmental leaders and laggards in Europe: Why there is (not) a 'Southern problem'. Aldershot, Ashgate.

Branco M.C. and Rodrigues L.L. (2006). Communication of corporate social responsibility by Portuguese banks: A legitimacy theory perspective, Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 11, 232-248.

Business Roundtable (2007). Climate change: Business roundtable supports actions to address global warming, http://www.businessroundtable.org/initiatives/growth/ climate.

Carbon Disclosure Project - CCDP (2013). Global 500 Climate Change report 2013, Carbon Disclosure Project - PriceWaterCoopers, London.

Chapple W. and Moon J. (2005). Corporate social responsibility in Asia: A seven-country study of CSR website reporting, Business and Society, 44, 415-441.

Cho C.H., Guidy R.P., Hageman A.M. and Patten D.M. (2012). Do actions speaker louder than words? An empirical investigation of corporate environmental reputation, Accounting, Organizations and Society, 37, 14-25.

Cho C.H. and Patten D.M. (2007). The role of environmental disclosures as tools of legitimacy: A research note, Accounting, Organizations and Society, 32, 639–647. Cooke T.E. (1989). Voluntary corporate disclosure by Swedish companies, Journal of

International Financial Management and Accounting, 1, 171-195.

da Silva Monteiro S.M. and Aibar-Guzmán B. (2009). Determinants of environmental disclosure in the annual reports of large companies operating in Portugal, Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 17, 185-204.

Deegan C. (2002). The legitimising effect of social and environmental disclosures - A theoretical foundation, Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 15, 282-311.

Di Maggio P.J. and Powell W.W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields, American Sociological Review, 48, 147-160.

Doran K.L., Quinn E.L. and Roberts M.G. (2009). Reclaiming transparency in a changing climate: Trends in climate risk disclosure by the S&P500 from 1995 to the present, Center for Energy and Environmental Security.

Dowling J. and Pfeffer J. (1975). Organizational legitimacy: Social values and organizational behaviour, Pacific Sociological Review, January, 122-136.

Freedman M, and Jaggi B. (2009). Global warming and corporate disclosures: A comparative analysis of companies from the European Union, Japan and Canada, Sustainability, Environmental Performance and Disclosures (Advances in Environmental Accounting & Management), 4, 129-160.

Gray R.H., Owen D.L. and Maunders K.T. (1987). Corporate social reporting: Accounting and accountability, Hemel Hempstead, UK: Prentice Hall.

Hackston, D., Milne, M. J., 1996. Some determinants of social and environmental disclosures in New Zealand companies. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 9, 77-108.

Hughes S.B., Anderson A. and Golden S. (2001). Corporate environmental disclosures: Are they useful in determining environmental performance? Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 20, 217-240.

Halkos G.E. (2006). Econometrics: Theory and Practice. Giourdas Publications

Halkos G.E. (2007). Econometrics: Theory and Practice, instructions in using EVIEWS, MINITAB, SPSS, EXCEL. Gutenberg Publ.

Halkos G.E. and Sepetis A. (2007). Can capital markets respond to environmental policy of firms? Evidence from Greece, Ecological Economics, 63(2-3), 578-587.

Halkos G.E. (2014). The Economics of Climate Change Policy: Critical review and future policy directions, MPRA Paper 56841, University Library of Munich, Germany.

Halkos G.E. (2015). Climate Change Actions for Sustainable Development. International Journal of Innovation and Sustainable Development9(2): 118-136.

Kassolis M.G. (2007). The diffusion of environmental management in Greece through rationalist approaches: Driver or product of globalisation? Journal of Cleaner Production, 15, 1886-1893.

Kolk A. (2008), Sustainability, accountability and corporate governance: Exploring multinationals’ reporting practices, Business Strategy and the Environment, 17, 1-15.

KPMG (2013). International survey of corporate responsibility reporting 2013. Amsterdam, KPMG Global Sustainability Services.

Kufidou S., Petridou E. and Mihail D. (1997). Upgrading managerial work in the Greek civil service, International Journal of Public Sector Management, 10, 244-253.

Lindblom C. (1994). The implications of organizational legitimacy for corporate social performance and disclosure. Paper presented at Critical Perspectives on Accounting Conference, New York.

Line M., Hawley H. and Krut R. (2002). The development of global environmental and social reporting, Corporate Environmental Strategy, 9, 69-78.

Mathews M.R. (1993). Socially responsible accounting. London, Chapman Hall. Matten D.A. and Moon J. (2008) Implicit” and “explicit” CSR: A conceptual

framework for understanding of corporate social responsibility, Academy of Management Review, 33, 404-424.

Meijer M.M. and Schuyt T. (2005). Corporate social performance as a bottom line for consumers, Business and Society, 44, 442-461.

Ng E.J. and Koh C.H. (1994). An agency theory and probit analytic approach to corporate non-mandatory disclosure compliance, Asia-Pacific Journal of Accounting, 1, 29-44.

Patten D.M. (1991). Exposure, legitimacy and social disclosure, Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 10, 297–308.

Patten D.M. (2002). The relation between environmental performance and environmental disclosure: A research note. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 27, 763-773.

Philippidou S.S., Soderquist K.E. and Prastacos G.P. (2004). Towards new public management in Greek public organisations and the path to implementation, Public Organization Review: A Global Journal, 4, 317-337.

Robb S.W.G., Single L.E. and Zarzeski, M.T. (2001). Nonfinancial disclosures across Anglo-American countries, Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation, 10, 71-83.

Roberts R.W. (1992). Determinants of corporate social responsibility disclosure: An application of stakeholder theory, Accounting, Organizations and Society, 17, 595-612.

Secchi D. (2006). The Italian experience in social reporting: An empirical analysis, Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 13, 135-149. Snider J., Hill R. and Martin D. (2003). Corporate social responsibility in the 21st

century: A view from the world’s most successful firms, Journal Business Ethics, 48, 175-187.

SPSS Inc. (1999). SPSS Base 10.0 for Windows User’s Guide, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL.

Stanny E and Ely K. (2008). Corporate environmental disclosures about the effects of climate change, Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 15, 338-348.

Tang L. and Li H. (2009). Corporate social responsibility communication of Chinese and global corporations in China, Public Relation Review, 35, 199-212.

Tsakarestou B. (2004). Greece: The experiment of market expansion. In: Habisch A, Jonker J, Wegner M, and Schmidpeter R (Eds), Corporate social responsibility across Europe, Berlin, Heidelberg, Springer, p. 261–273.