Commitment Therapy

(ACT) in practice:

ACT consistency of multidisciplinary professionals

in the Dutch pain rehabilitation

!

Author: Alicia HoppeSupervisors:

Hester R. Trompetter, Msc. Karlein M. G. Schreurs, PhD Department of Psychology

Abstract

Objective: This study investigates the implementation of Acceptance and

Commitment Therapy (ACT) in nine Dutch chronic pain rehabilitation centers. In this study, an existing, qualitative coding scheme was evaluated and adjusted. Afterwards, consistency in ACT practice was analyzed. Therefore adherence to the ACT protocol and competence in working with ACT were scored.

Method: In an iterative process the coding scheme of Scholten (2014) was reviewed. Using the revised coding scheme, adherence to the ACT protocol and competence in working with ACT of three psychologists, five occupational therapists, three

physiotherapists and four social workers were analyzed.

Results: The final coding scheme uses a coding unit of one minute, adds a column to write down the content, scores every competence separately, and allows scoring of ACT processes twice (or more). All participating professionals worked in adherence to the ACT protocol and were competent in working with ACT. No significant differences were found between both adherence and competence and the different subgroups. The implementation can be rated as successful.

Samenvatting

Achtergrond: In deze studie werd de implementatie of Acceptance and Commitment Therapie (ACT) in negen chronisch pijn revalidatiecentra in Nederland geëvalueerd. Daarnaast werd een bestaand kwalitatieve codeerschema geëvalueerd en aangepast. Op basis van dit schema, werd vervolgens ACT consistent werken geanalyseerd. Hiervoor werden adherence aan het ACT protocol en competentie in werken met ACT gescoord.

Methode: In een iteratief proces werd het codeerschema van Scholten (2014) herzien. Met het finale codeerschema werd adherence aan het ACT protocol en competentie in ACT consistent werken van drie psychologen, vijf ergotherapeuten, drie

fysiotherapeuten en vier maatschappelijke werkers geanalyseerd.

Resultaten: Het finale codeerschema gebruikt een codeereenheid van een minuut, bevat een kolom om de inhoud neer te schrijven, iedere competentie wordt

afzonderlijk gescoord en ACT processen kunnen in het geval dat ze langer aanwezig zijn meer dan een keer gescoord worden. Alle participanten hebben adherent aan ACT en competent met ACT gewerkt. Geen significante verschillen zijn gevonden tussen adherence en competentie en tussen de verschillende subgroepen. Dit geeft

aanwijzing dat de implementatie of ACT succesvol is geweest.

Table of Contents

Introduction ... 5!

Treatment of patients with chronic pain ... 5!

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy ... 6!

Treatment Integrity ... 9!

Purposes and Hypotheses ... 10!

Method ... 12!

Previous implementation (October 2010-October 2012) ... 12!

Material ... 13!

Participants ... 15!

Data analysis ... 15!

Study 1 ... 16!

Study 2 ... 16!

Results ... 17!

Study 1 ... 17!

Study 2 ... 19!

Discussion ... 24!

Limitations ... 28!

Future research ... 29!

Conclusion ... 31!

References ... 32!

Appendix ... 35!

Appendix A ... 35!

Appendix B ... 39!

Appendix C ... 45!

Introduction

In the Netherlands, an estimated 18% of the population suffers from chronic pain, with prevalence in Europe ranging from 12% to 30% (Breivik, Collett, Ventafridda, Cohen, & Gallacher, 2006). Chronic pain has severe impact on patients’ daily functionality. It is a substantial problem for the individual person, their social environment and our society in general. Many patients experiencing pain were less able or no longer able to take part in various activities such as sleep, household chores, and social activities. A total of 19% had lost their jobs because of pain (Breivik et al., 2006). The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) defines pain as “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage” (IASP Taxonomy Working Group, 2011). Notably, the subjectivity of the experienced pain are central in this definition, rather than its cause, whether they be physiological, tissue damage, or otherwise. Common chronic pain conditions are headache, back or neck pain, and arthritis or joint pain (Tsang et al., 2008). Pain is said to be chronic if it persists or occurs repeatedly over a period of more than three month

(Merriam-Webster, 2014).

Treatment of patients with chronic pain

A study on chronic pain and its treatment in the Netherlands indicates that a substantial proportion of patients receive drug treatment for their pain, and a

significant number of patients reported using a range of different

The results of a study of Turk, Wilson, and Cahana (2011) suggest that none of the more commonly prescribed treatment regimens are, by themselves, sufficient to eliminate pain and to increase physical and emotional functionality in most patients with chronic pain. Gatchel, Peng, Peters, Fuchs, and Turk (2007) and Turk et al. (2011) advocated the multidisciplinary pain management approach, which implied the use of comprehensive treatment of emotional, cognitive, behavioral and psychosocial dimensions. Furthermore, Turk et al. (2011) recommended including dialogue with the patient about realistic expectations of pain relief focusing on improvement of functionality instead of fighting the pain.

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

The Acceptance and Commitment therapy (ACT) focuses not on fighting the pain but on improving the functionality of chronic pain patients, which can be performed by a multidisciplinary team. According to ACT, the primary source of psychopathology is the way language and cognition react to negative events, such as pain, producing an inability to change behavior (Hayes, Luoma, Bond, Masuda, & Lillis, 2006). The result is psychological inflexibility. ACT has the goal to change behavior, but if behavior changes, psychological barriers are met. Those barriers are, at the same time, addressed through the processes of ACT (Hayes et al., 2006; Luoma, Hayes, & Walser, 2007). Thus, to overcome those barriers and the

psychological inflexibility, ACT consists of six core processes, with none of them standing alone, but being all interrelated and influenced by each other (Figure 1; A-Tjak, 2009; A-Tjak & De Groot, 2008; Hayes et al., 2006; Hayes, Strosahl, & Wilson, 2012; Luoma, Hayes, & Walser, 2007). The six processes can be combined in three response styles. The first is the ‘open response style’ that unites the core processes

himself or herself from negative events and embrace them actively and with

Figure 1. The six core processes of ACT

Participants, who completed an ACT treatment, reported on average significantly higher levels of satisfaction with the treatment than patients who

received cognitive behavioral therapy (Wetherell et al., 2011). Results from a study of Wicksell, Melin, Lekander, and Olsson (2009) suggest that an ACT oriented

pain control groups. The effectiveness of ACT has also been supported through the findings of additional studies (Dahl, Wilson, & Nilsson, 2004; Kratz, Davis, & Zautra, 2007; McCracken, MacKichan, & Eccleston, 2007; Vowles, Wetherell, & Sorrell, 2009; Wicksell, Olsson, & Hayes, 2010). The results of an exploratory meta-analysis of studies on the effects of acceptance-based therapies on mental and physical health in patients with chronic pain, suggest that ACT can be a good alternative to CBT, but additional high-quality studies are needed for a more definitive conclusion (Veehof, Oskam, Schreurs, & Bohlmeijer, 2011).

Treatment Integrity

ACT has been implemented systematically in nine Dutch rehabilitation centers between 2010 and 2012. Over the course of two years professionals were trained in ACT through various workshops, interventions and supervision (more information: Trompetter, Schreurs, & Heuts, 2014). In order to investigate if the implementation of ACT is performed successfully, treatment integrity will be examined in this study. Treatment integrity refers to the degree in which a treatment is implemented consistently with the underlying theory (Perepletchikova, Treat, & Kazdin, 2007; Plumb & Vilardaga, 2010; Southam-Gerow & McLeod, 2013). Even though

competence, are highlighted in most definitions, with adherence referring to the extent to which a professional uses interventions prescribed by the treatment manual, protocol or model and with competence referring to the level of skill at which the professional is operating (Plumb & Vilardaga, 2010; Waltz et al., 1993). Additionally, it is defined that adherencedoes not necessarily encompass competence, meaning that following the protocol does not automatically equate to therapist competence (Plumb & Vilardaga, 2010; Waltz et al., 1993).

Investing treatment integrity has several advantages, including linking treatment effects to the specific processes the model predicts to be related to change. Second, treatments can be compared across settings as well as across therapists and studies. Third, treatment integrity checks provide information for training and supervision procedures and are an essential tool to discriminate between different treatments (Waltz et al., 1993). Additionally, if we know about the quality of the ACT implementation performed in the Netherlands, the quality of further research on the effectiveness of ACT for chronic pain patients will be higher and the contribution to future research will be greater.

Purposes and Hypotheses

enhancement. The aim of the first study is to support the development of a scheme, which provides necessary tools for future integrity checks of ACT.

In order to measure the success of the ACT implementation, the second study examines the treatment integrity of the participating professionals in working with ACT. The emerging research question of the explorative study 1 is ‘To what extent is the existing treatment integrity scheme sufficient, and what needs to be added to the

existing treatment integrity scheme to make it more sufficient?’ For study 2, the

research questions ‘To what extent were the participating professionals adhering to

the ACT protocol and were they competent in working with the ACT protocol’

emerges.We expectedthat the participating professionals would score above average

in adherence and competence. Furthermore, we expected differences in adherence and

competence between the different groups of professionals, between early and late

adopters, and among participating professionals with various levels of work

experience with ATC, with ‘junior’ having lower and ‘senior’ having higher scores in

adherence and competence.

We found the competence to use ACT processes and interventions flexible

depending on the client, and the content of the sessions to be more ACT specific than

the other competences which led us to the assumption that more training or

experience will lead to higher scores on this competence. We expected that there may

be a difference among the scores of the various subgroups (early and late adopters,

participating professionals with a different amount of work experience with ACT) on

that ACT specific competence. We further explored this interesting indication in a

Method

Previous implementation (October 2010-October 2012)

The current study evaluates the implementation of ACT in nine Dutch pain rehabilitation centers between October 2010 and October 2012, all of which had no prior experience with the technique. ACT was introduced using a two-part ‘train-the-trainer’ approach (Figure 2). In each institution a multidisciplinary team received an initial 6-day training course called ‘ACT for pain-teams’, in which the theoretical background as well as the practical application of ACT was conveyed. Over the following 6 months, the team adopted ACT while being supported by three external supervisions. During the initial 6 month adoption period, the participating

professionals received continuous online support and met every 4-6 weeks to discuss progress and possible problems in working with ACT. After these 6 months, the participating professionals took over the role of mentors and trained other

Figure 2. ‘Train-the-Trainer’ approach used for the implementation of ACT. In each institution a team received a 6-day training course called ‘ACT for pain-teams’. After this team (‘early adopters’) gained experience in working with ACT, they started to train other practitioners, based on their training in a 2-day workshop (‘late adopters’).

Material

Questionnaires. At the beginning of the implementation in October 2010 all participating professionals were asked to fill in a standardized questionnaire

developed by the main researcher, Hester Trompetter, to provide relevant background information such as age, profession and work experience with ACT (Appendix C).

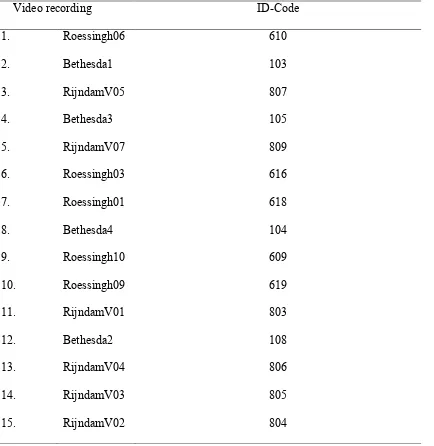

recorded. Furthermore, twelve recorded therapy sessions were held in consulting offices. Three recorded therapy sessions were held in work or gymnastic rooms where the patients were working with material provided by the participating professionals. The data received through the participating professionals was treated completely anonymously, allocating one ID-code to a video recording and the associated questionnaires (Appendix A).

Scoring scheme of Scholten (2014). The coding scheme of Scholten (2014) provides instructions on how to score and rate the consistency of professionals working with ACT. According to this coding scheme, every minute of a video recording should be watched and scored (cf., Appendix B). The first step is to determine which of the six ACT processes the participating professional applies. Second, adherence is rated by assigning scores ranging from 1 (not adhering to ACT interventions appropriate to core process) to 5 (complete adherence to ACT

order to create room for experience instead of just talking about it (Scholten, 2014). Competence is rated by assigning a score from 1 (not complying to ACT

competencies) to 5 (completely complying with ACT competencies). This should also be done for every minute. In case of absence of an ACT process, the rater is still allowed to assign scores to thecompetencies.

Participants

At the end of the implementation of ACT in the rehabilitation centers, video data of 25 professionals were collected. For this specific study, we analyzed 15 video recordings. The inclusion criterion was that the participating professionals had the profession of a psychotherapist, occupational therapist, physiotherapist or a social worker. The 15 analyzed video recordings include material from five participating professionals from the Roessingh rehabilitation center in Enschede, six from the Rijndam rehabilitation center in Rotterdam (Vlietlandplein) and four from the

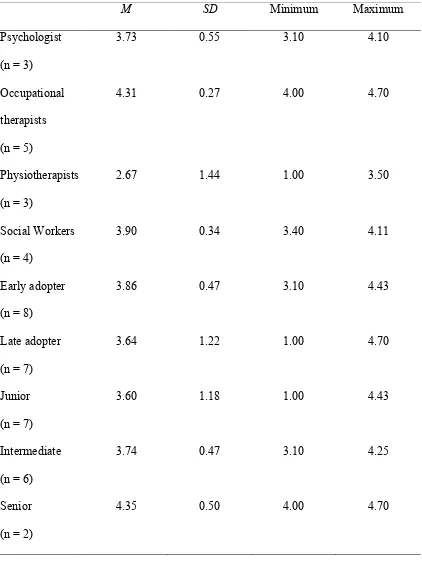

Bethesda hospital in Hoogeveen. The mean age of the participating professionals was 44.47 years (SD = 12.23), with a minimum age of 21 years and a maximum age of 60 years. Eighty percent of the participating professionals were female (n = 12). The

participants’ professions were psychologists (n = 3), occupational therapists (n = 5), physiotherapists (n = 3) and social workers (n = 4), and their average work experience with their current profession was 14.64 years (SD = 5.6). More background

information is available in Table 1 in Appendix A.

Data analysis

(Bohlmeijer & Hulsbergen, 2009) and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy – An experimental approach to behavior change (Hayes, Strohsahl, & Wilson, 1999).

Study 1

To answer the research question ‘to what extent is the existing treatment integrity scheme of Scholten (2014) sufficient, and what needs to be added to the existing

treatment integrity scheme to make it more sufficient’, an iterative process was used.

In this iterative process the randomly chosen video recording ‘Roessingh 6’

was watched alongside the main researcher Karlein Schreurs. In each repetition, the

focus was placed on a different point. The steps taken in order to achieve the current

coding scheme are presented in the result section.

Study 2

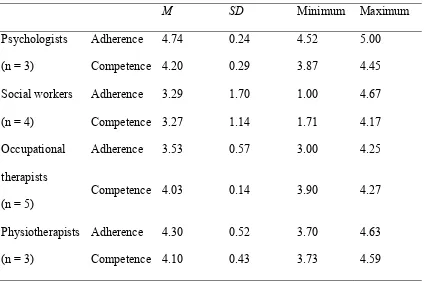

Video coding. Based on the adjusted coding scheme all 15 video recordings were coded pausing every minute of the video recording. In the first replay, it was checked to see if an ACT process was present, and in the second and third, adherence and competence were rated respectively. Afterwards, average scores for adherence and competence were calculated (Table 3).

Furthermore, we used an independent samples t-test to examine the

relationship between the participant’s designation as ‘early adopter’ or ‘late adopter’ to adherenceand competence and investigated if there is a possible difference between those two conditions.

Post hoc analysis. We further explored the possibility that there might be a correlation between participating professionals with a different amount of work experience or being an early or late adopter and their scores on the competence to use different ACT processes and interventions flexibly depending on the client and the content of the session.

Results

Study 1

Listed below are the steps taken to adjust the coding scheme developed by Scholten

(2014).

Material: Video recording ‘Roessingh 6’ has been watched and coded using the

coding scheme developed by Scholten (2014).

Considerations:

1. The coding unit of one minute is reviewed, because the researchers

experienced difficulties to adhere to this unit. The alternative idea was to

operate a unit based on content.

2. We tested the potential benefit of adding a summary of each minute’s contents

to the scale.

3. We tested whether important information would be lost when one

comprehensive score for competence is used, compared to when the three

4. We tested whether the code ‘the scoring runs through’ is sufficient or not. The

alternative idea tested was to code one process twice (or more), thus in one

minute and also in the other(s) if it was present longer than one (or more)

minutes.

5. The idea was to automatically calculate the mean of the adherence and

competence scores. Therefore it was tested to put the coding scheme into

spreadsheet software.

Results:

1. A unit based on content was found to be too subjective, with the consequence

being that there has been too much difference between the coding results of

the researchers. It is preferable to use a unit of one minute, running from 0.00

– 0.59 minute to evaluate every minute. The aim is to collect data, which can

be evaluated with statistical methods.

2. A column to note the content of every minute was added as a first column of

the revised scheme. The benefit is that the coder actively works with the

content before coding, which makes the coding more accurate.

3. Each of the three competences was scored separately. This allows for a more

accurate scoring of the competences because all three competences differ in

their content, and raters can vary the scores between the competences.

Furthermore, more information is available over the competences of the

practitioners.

4. An ACT process can be present two or more times in a video recording if the

ACT process is continuously present for a longer period. Also, more than two

ACT processes can be present at the same time.

Study 2

All video recordings were scored using the adjusted scheme. The mean scores of adherence are spread over the full range of the scale (1 to 5), with an overall mean of 3.84 (SD = 1.05). The mean scores for competencerange from 1.71 to 4.59, with an overall mean of 3.89 (SD = 0.69; Table 3). These scores indicate that the

Table 3

Mean adherence and competence scores of all videos

Video

Adherence

M

Competence

M

Roess_6 3.00 3.13

Beth_1 4.70 4.29

Rijndam_5 4.67 4.07

Beth_3 4.50 4.17

Rijndam_7 1.00 1.71

Roess_3 5.00 4.45

Roess_1 4.42 3.87

Beth_4 4.25 4.27

Roess_10 4.57 4.59

Roess_9 3.40 4.00

Rijndam_1 4.63 4.11

Beth_2 4.00 4.00

Rijndam_4 3.70 3.73

Rijndam_3 3.00 4.00

Rijndam_2 3.00 3.90

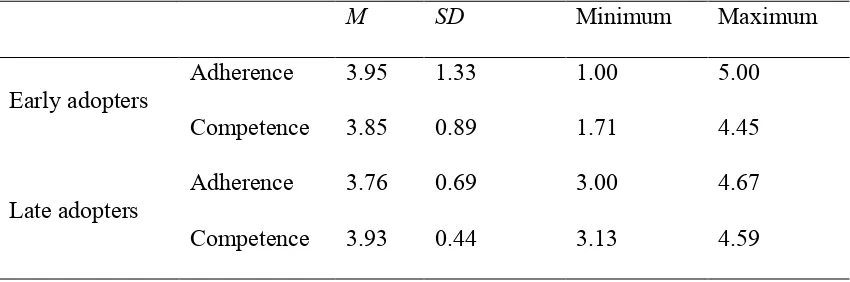

Scores of adherence and competence compared along early and late

adopters. The mean score of the early adopters for adherence is 3.95 (SD = 1.33) and for competence 3.85 (SD = 0.89). The late adopters have similar scores, with a mean score of 3.76 (SD = 0.69) for adherence and 3.93 (SD = 0.44) for competence (Table 5). Differences between groups of early and late adopters were insignificant; t(13) = .34, p = .742, and t(13) = -.23, p = .821, respectively (independent samples t-tests).

Table 5

Early and late adopters fare similarly well on measures of adherence and

competence.

M SD Minimum Maximum

Early adopters

Adherence 3.95 1.33 1.00 5.00

Competence 3.85 0.89 1.71 4.45

Late adopters

Adherence 3.76 0.69 3.00 4.67

Competence 3.93 0.44 3.13 4.59

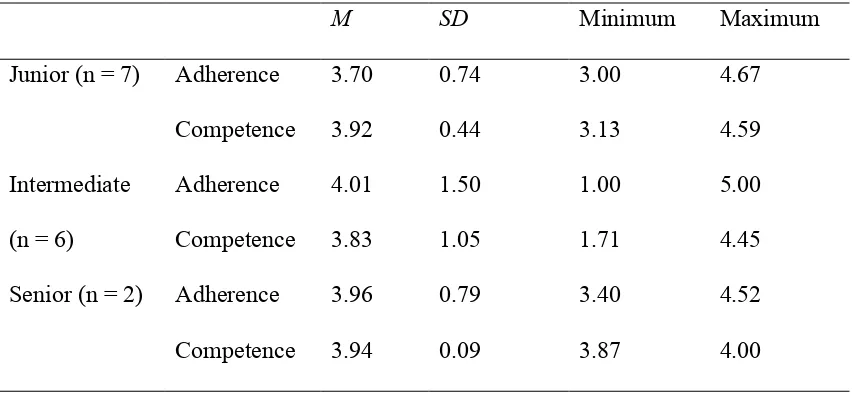

Scores of adherence and competence compared along work experience

Table 6

Participants with varying amount of work experience with ACT fare similarly well on

measures of adherence and competence

M SD Minimum Maximum

Junior (n = 7) Adherence 3.70 0.74 3.00 4.67

Competence 3.92 0.44 3.13 4.59

Intermediate (n = 6)

Adherence 4.01 1.50 1.00 5.00

Competence 3.83 1.05 1.71 4.45

Senior (n = 2) Adherence 3.96 0.79 3.40 4.52

Competence 3.94 0.09 3.87 4.00

Discussion

The overall goal of this study was to support the development of a sufficient treatment

of patients with chronic pain. As an alternative to the current chronic pain treatments,

ACT was implemented in nine Dutch chronic pain rehabilitation centers. We

investigated if this implementation was performed successfully.

First, the existing scoring scheme of Scholten (2014) was reviewed and

improved. Our resulting coding scheme uses a coding unit of one minute, adds a column to note the content of every minute, scores all three competences separately,

does score one ACT process twice or more if the process is present longer than a

minute, and is available as an spreadsheet file which automatically calculates the

average scores of the adherence and competence scores.

Second, the treatment integrity of the participating professionals in working with ACT was analyzed. The general hypothesis, that participating professionals score above average on both adherence and competence, was confirmed. This leads to

the conclusion that the implementation was successful. The participating

professionals, who received ACT training, are able to apply ACT. Furthermore, no

significant differences between the various subgroups have been found. Participants

with different professions do not seem to differ in their ability to apply ACT, and

neither do early and late adopters. Additionally, the level of work experience does not

seem to have influenced the ability to use ACT. This indicates that the

implementation is equally successful for all participating professionals. They are all

able to use ACT sufficiently and independently from the time which the participants

received treatment. This leads to the conclusion that if a small group of professionals

institution without a noticeable loss in quality. Training a small group of professionals

in ACT is thus a one-time investment.

Some points deserve further consideration. Contrary to our hypotheses, no

differences were found in the competence of early and late adopters, in the

competence of different professions, and in the competence of professionals with

varying amounts of work experience with ACT. To evaluate this outcome, the scoring

approach of competence was examined. In the approach of scoring competence, we

first scored three different competencies separately, and then calculated an average of

all scores. This procedure might have had negative effect on the results. Taking a look

at the competencies, we find that two out of three competencies are generic

competencies, as already introduced in the client-centered theory of Rogers (Rogers,

1957). ‘Rogerian’ psychotherapy is considered as a founding work in the humanistic

school of psychotherapies which means most of professionals in the social work area

studied his work during their education. The generic competencies are composed of

first, the willingness to address difficult and problematic inner experience of the

therapist and the client both during and outside the therapy session, and second,

maintaining an equivalent therapeutic relationship. Non-generic and ACT specific is

the third competency, which refers to the flexibility to use ACT processes and

interventions depending on the client and the content of the session. Looking at the

competencies separately leads us to the assumption that the scores on the ACT

specific competency might reflect the effect of the ACT training more accurately than

the scores on the two generic competencies. On basis of this assumption, a post hoc

analysis was performed to investigate if the scores on the ACT specific competency

indicate differences between the scores of the subgroups, such as the amount of work

participants with a greater level of work experience would have greater scores on the

ACT specific competency because they had more time to practice and use the specific

characteristics belonging to this competency. Contrary to our hypothesis, no

significant differences were found. Reason for this might be the small amount of

participating professionals, especially the lack of abundant number of participants

with a great amount of work experience with ACT.

Furthermore, we decided to score competence in working with the ACT

protocol even in instances where there is no ACT process present. In contrast, Waltz

et al. (1993) and Plumb and Vilardaga (2010) state that adherence is necessary to be

able to work competently with a protocol. Although, the approach of the final scheme

is in contrast with the theory of Waltz et al. (1993), scoring competence worked well.

With the ACT competencies being similar to generic competencies and CBT specific

competencies, adherence to the ACT protocol is not necessary to be able to score

competence. Overall, further research is necessary to explore the competence scoring

approach, with a special focus on the scoring of the third competency, because that is,

in contrast to the other competencies, linked to the use of ACT processes.

Moreover, in contrast to our hypotheses, no difference was found between

professions in the competence in working with ACT. Of all four analyzed professions,

psychologists gathered probably the most experience with CBT’s, and in

multidisciplinary teams, psychologists were both expected to be the initiators of new

therapeutic implementations or concepts (Brown & Folen, 2005), and expected to

perform better in therapeutic sessions, in this case in applying ACT. An explanation

why no significant differences between the professions were found might be that the

used data do not distinguish between the different ACT processes. Therefore,

lower is missing. Trompetter, Schreurs and Heuts (2014) differentiated between the

six different ACT processes in their study in the same implementation focusing on the

subjective competence of the participating professionals. They found that at the end of

the implementation, both early and late adopters rated their self-perceived

competencies adequate on almost all therapeutic processes, except on self as context

and cognitive defusion. Those two processes show little overlap with generic

competencies as well as other processes of CBT’s and are thus more challenging to

learn and use compared to ACT processes such as adherence or values (Trompetter,

Schreurs, & Heuts, 2014). Therefore, it is conceivable that an analysis of the use of

ACT processes could indicate differences in the ability of the different professions in

operating with ACT. Further research on the competence in working with the

different ACT processes is necessary to obtain better insight into this context and to

learn if the participating professionals need more support on some of the ACT

processes.

Another point, which deserves consideration, is that given the limited number

of participating professionals, statistical power was too small to detect existing

differences. Due to practical limitations, more video recordings could not be

analyzed. It is recommended to replicate this study with a greater number of

participants to get more reliable results.

Even though the results are contrary to our hypothesis, they also unveiled

intriguing results. The participating professionals were trained extensively for a

lengthy period of time. The results lead as to the conclusion that the training seems to

Limitations

Some methodological limitations of this study need to be reviewed. First, the

results cannot be controlled for inter-rater reliability. Due to practical limitations, the

video recordings are scored only by one rater. It is important to calculate the

inter-rater reliability to establish that the coders have been properly trained (Plumb and

Vilardaga, 2010). At the same time, a high inter-rater reliability allows for

generalization of results and results in conclusion that the developed scheme is an

objective method in scoring video recordings of participating professionals applying

ACT (Kottner et al., 2011).

Second, the main data sources are ten minutes of video recording of one

session per participating professional. In those video recordings the participating

professionals show that they are competent in working with ACT. However, one

video recording might not be representative of the adherence to the protocol during

the entire therapy because the professionals could decided on when and under what

circumstances the sessions were recorded (Nezu & Nezu, 2008; Plumb & Vilardaga,

2010). Furthermore, we may have to concede a ceiling effect. If all participants are

trained sufficiently enough to work effectively with ACT, factors such as work

experience and general education may become secondary. Each individual nearly

reached the (here) maximum measurable scores on adherence and competence, and

the results therefore, show no differences. This does not necessarily indicate that there

are zero differences. A psychologist with a work experience of ten years will most

likely score higher in extreme situations like dealing with an aggressive patient, than a

social worker with one year of work experience. It shows that the currently used

scheme did not set especially high standards. This is acceptable because the aim of the

sufficiently. The ideal result was to have all participants obtain high scores, especially

if the therapy will be found to have positive effects for the patients.

Third, a large variability is found in the assigned scores of the social workers,

suggesting large intra-group differences in the ability to operationalize ACT greatly.

However we only analyzed a small group of social workers, with one social worker

scoring much lower than the others. Analysis with a greater number of participants is

recommended to investigate the higher level of intra-group difference among the

social workers.

Future research

The overall goal was to develop a sufficient treatment for chronic pain patients to increase the treatment satisfaction and their overall well-being. We found all

participating professionals to be able to work sufficiently with ACT. The next step should be to investigate if the use of ACT is successful in increasing the treatment satisfaction and the well-being of the patients. It should be studied to see if the treatment sessions of all participating professionals had the same (positive) effect on the patients’ well-being. If differences between the participating professionals exist, they should be examined, even though there were not visible before due to the potential ceiling effect. Overall, if the study shows positive results, a change in the currently unsuccessful treatment of chronic pain patients is done.

Further research should be carried out to confirm if it is possible to improve

the implementation and to make it even more effective. The qualities of a

multidisciplinary team should be better utilized, noting the varying expertise of

different professions. The data show that the ACT processes acceptance and values

are used more often than other such as the ACT processes cognitive defusion and

ACT processes because they experience difficulties applying them or vice versa. If

this were the case, it should to be investigated to see if the ACT processes can be

subdivided into different professions so that not every professional has to learn and be

able to use every ACT process. Advantages would be a higher quality in all processes

as well as a shorter mandatory training period, because not everybody has to learn all

processes. Further research with a focus on the use of the different processes is

necessary to give more insight into this context.

Further more, since no significant differences were seen between the ‘early

adopters’ and ‘late adopters’ in the ability to work with ACT, it should be evaluated

to determine if a shorter training period will show the same positive results.

Therefore, further implementation should be carried out with a difference in the

training period to discover the shortest sufficient training period. Being able to apply

a shorter training period would save time and make the training more efficient.

Additionally, the professional background in multidisciplinary teams is

typically more varied than in the current study which features only four different

professional backgrounds. Future research should take other professions into account

This study was one of the first to investigate treatment integrity of ACT in the area of chronic pain rehabilitation. The implementation of ACT was successful and can be carried out as described. Trained professionals were successful in working with ACT and in training other professionals in ACT. The application of the ‘train-the-trainer’ approach was successful which provides advantage for future systematic

Late adopter 1 3 3 7 Self-assessment: level of

work experience with ACT at beginning of implementation

Junior 1 2 4 7

Intermediate 3 1 2 6

Table 2

Analyzed video recordings with associated ID-Codes

Video recording ID-Code

1. Roessingh06 610

2. Bethesda1 103

3. RijndamV05 807

4. Bethesda3 105

5. RijndamV07 809

6. Roessingh03 616

7. Roessingh01 618

8. Bethesda4 104

9. Roessingh10 609

10. Roessingh09 619

11. RijndamV01 803

12. Bethesda2 108

13. RijndamV04 806

14. RijndamV03 805

Codeer- en scoorschema voor ACT consistent handelen van professionals tijdens de behandeling van chronische pijn in Nederlandse revalidatiecentra

Video-opnames zullen de eerste 10 minuten bekeken en gescoord worden, waarbij de opname iedere minuut gepauzeerd word om te scoren. Hierbij loopt de 1e minuut van 0.00 tot 1.00 seconden, de 2e minuut van 1.01 tot 2.00 en zo verder. Mocht blijken dat hetgeen de therapeut zegt of doet behorende tot een ACT interventie of competentie doorloopt in de volgende minuut, dan geeft men met de woorden “scoring loopt door” aan dat men meerdere minuten achter elkaar bekijkt en scoort.

De volgorde waarin men de video-opname scoort is als volgt; 1. Geef aan om welk(e) ACT-kernproces(sen) het gaat (acceptatie en bereidheid, cognitieve defusie, hier-en-nu, zelf-als-context, waarden en/of toegewijde actie). Dit wordt genoteerd door het betreffende ACT kernproces volledig uit te schrijven. Wanneer er echter geen ACT-kernproces aanwezig is noteert men ‘n.v.t.’. 2. Scoor de mate van ‘adherence’. Wanneer men echter heeft aangegeven dat er geen ACT-kernproces aanwezig is, dan kan men ook geen score geven op ‘adherence’. 3. Scoort de mate van ‘competence’, dit is mogelijk ongeacht of men eerder heeft aangegeven dat er geen ACT- kernproces aanwezig is. 4. Geef een over-all score over de mate van ‘adherence’ en ‘competence’ gedurende de gehele video-opname.

Adherence

Bij ‘adherence’ wordt er gekeken naar de mate waarin ACT interventies behorende tot het behandelmodel en het ACT kernproces uitgevoerd worden. Scoring verloopt via een Likertschaal --/-/+-/+/++ (- - interventie helemaal niet passend bij ACT kenproces /++ interventie helemaal passen bij ACT kernproces).

Voorbeelden van ACT interventies

5

6

7

8

9

10

Overall score

whole video

Final coding scheme

Appendix C

The questionnaire the participating professionals filled in the beginning of the implementation and thus before the start of their ACT training:

Beste professional,

We willen u vragen de volgende vragenlijst in te vullen. De vragenlijst wordt aangeboden aan alle professionals die deelnemen aan de implementatie van ACT in de pijnrevalidatie. Er wordt hierbij geen onderscheid gemaakt tussen mensen die nu al ACT (gaan) toepassen of dit pas later in de implementatie gaan doen. Ook als u op dit moment nog geen ACT toepast is het dus belangrijk dat u de vragenlijst invult. De vragenlijst gaat over uw scholing en ervaring (algemeen & specifiek voor ACT), uw therapeutische vaardigheden in ACT en over verschillende factoren die een rol kunnen spelen bij de implementatie.

Deze vragenlijst ontvangt u aan het begin van de implementatie in uw instelling. Op twee andere momenten, later dit jaar, krijgt u opnieuw een vragenlijst. Dit zal halverwege (over ongeveer een half jaar) en aan het einde (over ongeveer een jaar) van het implementatietraject zijn. Door de vragenlijst meerdere malen af te nemen kunnen we de ontwikkelingen in de implementatie in kaart brengen.

Het invullen van de vragenlijst neemt ongeveer 50 minuten in beslag. Het is in het belang van het onderzoek dat u de vragenlijst zo waarheidsgetrouw mogelijk invult. Het is de bedoeling dat u per vraag één antwoord kiest, tenzij anders vermeld staat. Ook willen we u vragen de vragenlijst, wanneer u eenmaal begonnen bent, in één keer in te vullen. De ingevulde vragenlijsten worden vertrouwelijk behandeld en

Alvast hartelijk dank voor het invullen! Vriendelijke groet,

Hester Trompetter (Psycholoog/Onderzoeker Roessingh Research and Development & Universiteit Twente)

Karlein Schreurs (GZ-Psycholoog het Roessingh Revalidatiecentrum & onderzoeker Universiteit Twente

Algemene gegevens

Allereerst willen we u vragen enkele algemene gegevens in te vullen. Uw naam zal voor verwerking van de gegevens worden omgezet in een cijfercode, die enkel door de hoofdonderzoeker naar u te herleiden is.

Algemeen

1) Naam ………

2) Leeftijd ………… jaar 3) Geslacht 0 man

0 vrouw

4) Datum van invullen ... / ………. / ………...

Professioneel

5) In welke instelling werkt u?

6) Tot welke van de volgende groepen in de implementatie behoort u?

0 Trekker (u behoort tot een team binnen uw instelling dat de cursus ‘ACT bij pijnteams’ heeft gevolgd)

0 Volger (u behoort tot een team dat ACT zal gaan toepassen, nadat u scholing van collega’s hebt ontvangen)

0 Weet ik niet

7) Wat is uw functie?

0 Revalidatiearts 0 Psycholoog 0 Ergotherapeut 0 Fysiotherapeut

0 Maatschappelijk werker 0 Verpleegkundige 0 Sportdeskundige 0 Arbeidsdeskundige 0 Agogisch werker

0 Anders, namelijk ………

8) Staat u geregistreerd in het BIG-register? 0 Ja

0 Nee

9) Staat u geregistreerd in een Kwaliteitsregister van uw beroepsgroep? 0 Ja

10)In welk jaar bent u afgestudeerd? ………

11)Hoe lang bent u werkzaam als professional in de pijnrevalidatie? ... jaar

12)Hoe lang bent u werkzaam in uw huidige functie? ………….. jaar

13)Hieronder onderscheiden we drie ‘categorieën van deskundigheid’. Tot welke vindt u zichzelf behoren binnen uw eigen functiegebied?

0 Junior (starter, weinig ervaring)

0 Medior (nog niet geheel volleerd, enkele ervaring) 0 Senior (een expert, veel ervaring)

A. ACT: Scholing en ervaring

Hieronder stellen we u enkele vragen die specifiek over ACT gaan. De vragen gaan voornamelijk over eventuele scholing in ACT en uw (werk)ervaring met ACT.

14)Hoe lang geleden hebt u voor het eerst kennis gemaakt met ACT? 0 In de laatste 6 maanden

15)Hebt u de cursus ‘ACT voor Pijnteams’ (van Peter Heuts en Karlein Schreurs) gevolgd?

0 Ja 0 Nee

0 Gedeeltelijk

16)Hebt u (naast de cursus ‘ACT voor pijnteams’) andere cursussen, workshops, en/of bijeenkomsten (die u als scholing beschouwt) in ACT gevolgd, die minstens 1 dagdeel duurden? Het gaat hierbij niet om intervisies of andere uren ter kennisdeling met collega’s.

0 Ja (beantwoordt ook 16a)

0 Nee (ga door naar 17)

16a) Hoeveel dagdelen heeft u in totaal deelgenomen aan dergelijke cursussen, workshops of andere vormen van scholing in ACT (naast de cursus ‘ACT voor pijnteams’)?

0 Minder dan 1 dagdeel 0 1 – 2 dagdelen

17)Hoeveel boeken over ACT hebt u gelezen? 0 Geen boeken

0 1 boek 0 2 boeken 0 3 boeken 0 > 3 boeken

18)Hebt u andere vormen van literatuur over ACT gelezen (artikelen, stukken in vakbladen etc)?

0 Ja 0 Nee

19)Kunt u (bij benadering) aangeven welk aandeel van uw wekelijkse behandeltijd u op dit moment ACT toepast of gebruik maakt van ACT? 0 0 – 20%

team waarmee ik ACT toepas in het uitvoeren van ACT.

Ik voel me gesteund door mijn leidinggevenden (management) in het uitvoeren van ACT.

0 0 0 0 0 0

Mijn directe collega’s vinden het belangrijk dat ACT ingevoerd wordt in onze instelling.

0 0 0 0 0 0

Mijn teamgenoten waarmee ik ACT (ga) uitvoer(en) vinden het belangrijk dat ACT ingevoerd wordt in onze instelling.

0 0 0 0 0 0

Mijn leidinggevenden (management) vinden het belangrijk dat ACT ingevoerd wordt in onze instelling.

0 0 0 0 0 0

Het team waarmee ik ACT (ga) toepas(sen), is in staat ACT op een goede wijze uit te voeren.

te sluiten.

4) De therapeut past interventies aan en ontwikkelt nieuwe metaforen, experientiële oefeningen en gedragsgerichte opdrachten die passen bij de ervaring van de cliënt, diens taalgebruik en diens sociale, etnische, en culturele achtergrond of context.

5) De therapeut laat zien dat hij/zij problematische onderwerpen accepteert (die bijvoorbeeld tijdens de behandelingen opkomen) en is tegelijkertijd bereid om bij de tegenstrijdige of moeilijke ideeën, gevoelens en herinneringen van de cliënt te blijven zonder enige drang om die op te lossen.

6) De therapeut introduceert experientiële oefeningen,

paradoxen en/of metaforen waar dat van toepassing is en ontmoedigt te letterlijke interpretatie daarvan.

7) De therapeut voert het probleem altijd terug naar wat de ervaring van de cliënt laat zien en vervangt die authentieke, persoonlijke ervaring niet door eigen meningen of opvattingen.

8) De therapeut gaat niet in discussie, preekt niet, dwingt niet en tracht de cliënt niet te overtuigen.

zelf en worden, voor zover passend, direct als ondersteuning en illustratie ter sprake gebracht in de therapeutische relatie.

Bereidheid/acceptatie ontwikkelen

10) De therapeut maakt duidelijk dat er bij de cliënt geen sprake is van schade, defecten of onvolkomenheden, maar dat hij/zij gebruik maakt van niet-werkzame strategieën.

11) De therapeut helpt de cliënt direct contact te maken met de paradoxale effecten van strategieën gericht op controle van emoties.

12) De therapeut maakt in zijn/haar interacties met de cliënt actief gebruik van het concept ‘werkbaarheid’ of ‘werkzaamheid’.

13) De therapeut moedigt de cliënt actief aan te experimenteren met het staken van de strijd om emotionele controle en doet de suggestie om bereidheid/acceptatie als alternatief een kans te geven.

14) De therapeut wijst op de tegenstelling tussen de werkbaarheid van controlestrategieën en de werkbaarheid van

bereidheidstrategieën.

16) De therapeut helpt de cliënt de nadelen van een gebrek aan bereidheid/acceptatie ten opzichte van een waardengericht leven

onder ogen te zien.

17) De therapeut helpt de cliënt met het ervaren van de eigenschappen en diverse aspecten van bereidheid/acceptatie.

18) De therapeut gebruikt oefeningen en metaforen om te laten zien, dat bereidheid/acceptatie een activiteit is die plaatsvindt bij moeilijke innerlijke ervaringen.

19) De therapeut treedt op als voorbeeld van

bereidheid/acceptatie in de therapeutische relatie en helpt de cliënt deze vaardigheden ook buiten de therapie toe te passen.

20) De therapeut kan oefeningen die betrekking hebben op bereidheid/acceptatie structureren en geleidelijk opbouwen.

21) Kunt u met een rapportcijfer aangeven in hoeverre u zich

in het algemeen bekwaam acht in het toepassen van het proces

‘bereidheid/acceptatie ontwikkelen’?

Zeer onbekwaam Zeer

bekwaam

10

Cognitieve fusie ondermijnen

22) De therapeut onderkent de emotionele, cognitieve, fysieke, of gedragsmatige belemmeringen die bereidheid/acceptatie in de weg staan.

23) De therapeut oppert dat gehechtheid aan de letterlijke betekenis van deze ervaringen het moeilijk maakt bereidheid vol te houden (en helpt cliënten innerlijke ervaringen te zien voor wat ze zijn en niet voor wat ze pretenderen of lijken te zijn).

24) De therapeut wijst actief op de tegenstelling tussen wat er volgens het verstand van de cliënt zal werken en wat er volgens zijn of haar ervaring werkt.

25) De therapeut gebruikt taalgereedschap (bijv. ‘stop met dat ‘gemaar’’), metaforen (bijv. ‘passagiers in de bus’) en experientiële oefeningen (bijv. ‘gedachten op kaartjes’) om een scheiding aan te brengen tussen de cliënt en diens geconceptualiseerde ervaring.

27) De therapeut gebruikt diverse oefeningen, metaforen, en opdrachten om de verborgen eigenschappen van taal bloot te leggen.

28) De therapeut helpt de cliënt zijn of haar verhaal te

verhelderen en contact te maken met de evaluatieve en redengevende eigenschappen van het verhaal.

29) De therapeut helpt de cliënt contact te maken met het arbitraire karakter van causale verbanden in het verhaal.

30) De therapeut merkt ‘denkerigheid’ (fusie) op tijdens de sessie en leert de cliënt die zelf ook op te merken.

32) Kunt u met een rapportcijfer aangeven in hoeverre u zich

in het algemeen bekwaam acht in het toepassen van het proces

‘cognitieve fusie ondermijnen’?

Zeer onbekwaam Zeer

bekwaam

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

10

In contact komen met het hier en nu

33) De therapeut kan loskomen (defuseren) van de inhoud die de cliënt inbrengt en de aandacht richten op het moment.

34) De therapeut brengt zijn of haar eigen gedachten en gevoelens van het moment in binnen de therapeutische relatie.

35) De therapeut gebruikt oefeningen om bij de cliënt het gevoel voor ervaringen als een voortgaand proces te versterken.

36) De therapeut merkt op dat de cliënt afdwaalt naar het verleden of de toekomst en leert hem of haar terug te komen bij het hier en nu.

vestigt de aandacht op het huidige moment wanneer dat nuttig is.

38) De therapeut oefent met de cliënt om uit zijn of haar hoofd te komen en terug te keren in het hier en nu in de sessie.

39) Kunt u met een rapportcijfer aangeven in hoeverre u zich

in het algemeen bekwaam acht in het toepassen van het proces

‘in contact komen met het hier en nu’?

Zeer onbekwaam Zeer

bekwaam

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

10

Het geconceptualiseerde Zelf onderscheiden van het Zelf als

Context

40) De therapeut gebruikt metaforen om de cliënt te helpen onderscheid te maken tussen enerzijds de inhoud en producten van het bewustzijn en anderzijds het bewustzijn op zich.

41) De therapeut gebruikt oefeningen om de cliënt te helpen contact te maken met het zelf als context en dit te onderscheiden van het geconceptualiseerde zelf.

helpen op te merken hoe de geest en het ervaren van emoties werken en helpt tegelijkertijd contact te maken met een zelf dat keuzes maakt en dingen doet met die ervaringen, in plaats van ten dienste van die ervaringen.

43) De therapeut helpt de cliënt het verschil te zien tussen het zelf dat evalueert en de evaluatie op zich.

44) Kunt u met een rapportcijfer aangeven in hoeverre u zich

in het algemeen bekwaam acht in het toepassen van het proces

‘het geconceptualiseerde zelf onderscheiden van het zelf als

context’?

Zeer onbekwaam Zeer

bekwaam

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

10

Richtinggevende waarden bepalen

45) De therapeut helpt de cliënt richtinggevende waarden voor zijn leven te verhelderen.

op.

47) De therapeut leert de cliënt om onderscheid te maken tussen waarden en doelen.

48) De therapeut maakt onderscheid tussen bereikte resultaten en betrokkenheid bij het leven als proces.

49) De therapeut geeft zijn eigen, voor de therapie relevante waarden en toont in handelen en gedrag het belang daarvan.

50) De therapeut respecteert de waarden van de cliënt en verwijst door of zoekt een ander alternatief als hij die niet kan ondersteunen.

51) Kunt u met een rapportcijfer aangeven in hoeverre u zich

in het algemeen bekwaam acht in het toepassen van het proces

‘richtinggevende waarden definiëren’?

Zeer onbekwaam Zeer

bekwaam

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

Patronen van toegewijd handelen opbouwen

52) De therapeut helpt de cliënt bij het formuleren van positief gewaardeerde levensdoelen en het opstellen van een daaraan gekoppeld actieplan.

53) De therapeut stimuleert de cliënt om ondanks ervaren

barrières (bijv. faalangst, traumatische herinneringen, verdriet, gelijk willen krijgen) commitments aan te gaan en deze na te komen. De therapeut geeft aan dat nog meer barrières te verwachten zijn bij het naleven van deze commitments.

54) De therapeut helpt de cliënt om de kenmerken van toegewijd handelen (bijv. vitaliteit, een gevoel van groei) te herkennen en waarderen. De therapeut helpt de cliënt kleine stappen te nemen terwijl hij contact blijft houden met deze kenmerken van toegewijd handelen.

55) De therapeut houdt de aandacht van de cliënt gericht op steeds grotere patronen van handelen/acties, om zo de cliënt te helpen in de loop van de tijd consistent naar zijn doelen te blijven handelen.

56) Zonder te oordelen integreert de therapeut vergissingen en terugval in het proces dat gericht is op het nakomen van

---

Een laatste vraag: Behandelaars in een multidisciplinair team hebben verschillende werkzaamheden (denk bijvoorbeeld aan het verschil in werkzaamheden van een psycholoog en een ergotherapeut). Hierdoor kan de bruikbaarheid, de toepasbaarheid en/of het belang van de zes ACT-processen anders zijn voor verschillende functies. Kunt u hieronder aangeven welke van de zes ACT-processen naar uw mening goed passen bij uw functie?

0 Bereidheid/acceptatie ontwikkelen 0 Cognitieve fusie ondermijnen 0 In contact komen met het hier en nu

0 Geconceptualiseerde Zelf onderscheiden van Zelf als Context 0 Richtinggevende waarden bepalen

handelen/acties.

57) Kunt u met een rapportcijfer aangeven in hoeverre u zich

in het algemeen bekwaam acht in het toepassen van het proces

‘patronen van toegewijd handelen opbouwen’?

Zeer onbekwaam Zeer

bekwaam

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

0 Patronen van toegewijd handelen opbouwen

Dit is het einde van de vragenlijst, nogmaals hartelijk dank voor uw medewerking!

Appendix D