ROBERT S. LORIMER - INTERIORS AND FURNITURE

DESIGN

Lindsay Macbeth Shen

A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD

at the

University of St Andrews

1994

Full metadata for this item is available in

St Andrews Research Repository

at:

http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/

Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item:

http://hdl.handle.net/10023/15334

ROBERT S. LOR1MER

ProQuest Number: 10167233

All rights reserved

INFORMATION TO ALL USERS

The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted.

In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed,

a note will indicate the deletion.

uest

ProQuest 10167233

Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author.

All rights reserved.

This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C o d e Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC.

ProQuest LLC.

789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346

ROBERT S • LORXMER

INTERIORS AND FURNITURE DESIGN

LINDSAY MACBETH SHEN

THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY

1-(i) I, Lindsay Macbeth Shen, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 83,000 words in length, has been written by me, that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree,.

date 22-4-1993 Signature of candidate .

(ii) I was admitted as a research student undp^

Ordinance No. 12 in January 1990 and as a candidate for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy in July 1990; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out

in the University of St. Andrews between 19/90 and 1993-^

date 22-4-1993 Signature of candidate.

...

/

(iii) I hereby certify that the candidate ha,s fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution ahd

Regulations appropriate for the degree of Do'ctorate of Philosophy in the University of St. Andrews and that the candidate is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree.

date ... Signature of supervisor...

In submitting this thesis to the University of St. Andrews I wish access to it to be subject to the

following conditions:

B RESTRICTED

for a period of 5 years from the date of submission, the thesis shall be made available for use only with the consent of the Head/Chairman of the department in which the work was carried out.

I understand, however, that the title and abstract of the thesis will be published during this period of restricted access; and that after the expiry of this, period the thesis will be made available for use in accordance with the regulations of the University Library for the time being in force, subject to any copyright in the work not being affected thereby, and a copy of the work may be made and supplied to afay bona

fide library or research worker. ■■ ' "

VOLUME 1

CONTENTS

List of Contents ii

Acknowledgements iii

List of Abbreviations iv

List of Plates v

Note on Layout xviii

Abstract xx

Introduction 1

Chapter 1: The Scottish Tradition 8

Chapter 2: Collecting, and the Influence of 73

Antiques on Furniture Design

Chapter 3: The Architect as Interior Designer 156

Chapter 4: Attitudes to the New: Tradition and

Technology 223

Chapter 5: Workmanship 303

Conclusion 364

Appendix 1: The Marchmont Pallet, Whytock . 368

and Reid

Appendix 2: Furniture provided for Balmanno 373

Castle by Whytock and Reid

Appendix 3: Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society: 375

List of Work by Robert Lorimer

Bibliography 378

VOLUME 2 PLATES

INTERIORS, DRAWINGS, DECORATIVE ARTS AND RELATED MATERIAL

VOLUME 3 PLATES

A C K N O W L E D G E M E N T S

I would like to thank the following for their help in the production of this thesis:

Neil Adams and Peter Burgess of Burgess Adams Architects, Renier Baarsen, June Baxter and the

National Trust for Scotland East Fife Members' Centre, Laurance Black, Stephanie Blackden, E.A.H. Blythe,

Baron St. Clair Bonde, Louise Boreham, John Bruce, Patrick Buchanan, Ronald G. Cant, Wilma Capperauld, Annette Carruthers, Jack Clow, Alan Crawford, The Earl of Crawford and Balcarres, Charles, Isla and David Crichton, Elizabeth Cumming, Peter Donaldson, Sheila Downie, The Baron and Baroness of Earlshall, Sandy

East, East Neuk of Fife Preservation Society, the staff of Edinburgh University Library, Special Collections, Iain Flett, Martin Forrest, Chloe Forrester, John Frew, the Gapper Bequest, Christopher Gilbert, Ian Gow,

Elspeth Hardie, Christopher Hartley, David Jones,

Juliet Kinchin, William Laing, Julian Llewellen Palmer, Helen Lloyd-Jones, Mrs Christopher Lorimer, Hew

Lorimer, William Lorimer, Audrey and Ewan Macbeth, Max

Mackay-James, David Maclure, Alexander Mair, Stuart

Matthew, Deborah Mays, Mary Miller, the staff of the Mitchell Library, Glasgow, Frederick Multon, Andrew Myl'ius, the staff of the National Art Library, Victoria and Albert Museum, the staff of the National Library of Scotland, the staff of the National Monuments Record of Scotland, John Noble, Ross Noble, P. A. Oppenheim, Mr. Pearson, John and Marjorie Perry, Bruce Pert, J.

Pollard, Campbell and David Reid, and the staff of Whytock and Reid, Norman Reid, Harriet Richardson, Agnes Robertson, Pamela Robertson, Julia Rolfe,

Alistair Rowan, the staff of the Royal Institute of British Architects Library, the Russell Trust, Peter Savage, David Scarrat, Byron Ciping Shen, Robert Smart, Lady Sutherland, Margaret Swain, University of St.

Andrews Reprographics Department, Dawn Wadell, Lorna Wadell, Eliane Wheeler, Rena Williamson, the late Hugh L. B. Worthington, Elizabeth Wright.

L I S T O F A B B R E V I A T I O N S

AIA American Institute of Architects

BGA Bromsgrove Guild Archive

BP Bruce Pert

DIA Design and Industries Association

EAA Edinburgh Architectural Association

EAS Edinburgh Architectural Society

ECA Edinburgh College of Art

ECL Edinburgh Central Library

EUL SC Edinburgh University Library, Special ■

Collections

GUA Glasgow University Archive

HWC Heriot-Watt College Archive

LS Lindsay Shen

NAL National Arts Library, Victoria and Albert

Museum

NGS National Gallery of Scotland

NLS National Library of Scotland

NMRS National Monuments Record of Scotland

NMS National Museums of Scotland

PA Peter Adamson

QIAS Quarterly of the Incorporation of Architects

in Scotland

RIBA Royal Institute of British Architects

RIBA DIA DIA Archives, RIBA Library

RIBA DIAP DIA Archives/Peach Papers, RIBA Library

RSA Royal Scottish Academy

SM Stuart Matthew

SRO Scottish Record Office

WRA Whytock and Reid Archives

WRA/B Whytock and Reid Archive, Basement

L I S T O F P L A T E S

Unless otherwise stated, work illustrated is by Robert Lorimer.

VOLUME 2

FIGURE 1 Earlshall, Leuchars, Fife. The hall, south

end. Architectural Review 46 (July - Dec. 1919).

FIGURE 2 Earlshall. The hall, north end. Architectural Review 46 (July - Dec. 1919) .

FIGURE 3 "Sideboard which purports to have belonged to

Queen Margaret, Queen of James IV". Paton, Scottish

National Memorials (Glasgow, 1890).

FIGURE 4 Scott Morton and Company. 25 Learmonth

Terrace, Edinburgh, billiard room from the ingle. Art

Journal 49 (1897).

FIGURE 5 George Walton. Chair for Buchanan Street Tea

Rooms, Glasgow, 1896. Larner, The Glasgow Stvle.

FIGURE 6 Charles Rennie Mackintosh. Chair for hall at

Windyhill, Kilmacolm. H. 133.7cm. w. 73.2cm. d.

54.5cm. Oak, stained dark. Billcliffe, Charles Rennie

Mackintosh 1901.31.

FIGURE 7 Caqueteuse chair. Oak. Photographed in

Whytock and Reid's showroom. LS 1992.

FIGURE 8 Wheeler workshop, Arncroach, Fife.

Caqueteuse chair. H. 113cm. w. 59cm. d. 42.5cm.

1904. Oak. The Earl of Crawford. LS 1990.

FIGURE 9 Balcarres Estate Office. Caqueteuse chairs

and octagonal rent table. The Earl of Crawford. LS

1990.

FIGURE 10 Caqueteuse chair. Provenance St. Monans,

Fife. Oak. 1618. The East Neuk of Fife Preservation

Society. PA 1990.

FIGURE 11 Sketch of oak cabinet at Edinburgh Museum,

May 1889. Sketchbook 52. NMRS (Lorimer Collection).

FIGURE 12 Ellary, Argyllshire. Chimneypiece. Oak.

Inlay by Morison and Company. Shaw Sparrow, British

Home.

FIGURE 13 Hallyburton, Perthshire. Dining room. Oak. Architectural Review 2 0 (July - Dec. 19 06) .

FIGURE 14 8 Great Western Terrace, Glasgow.

Chimneypiece. EUL SC (Lorimer Collection).

FIGURE 15 8 Great Western Terrace, Glasgow. Window

corner of dining room. Shaw Sparrow, British Home.

FIGURE 16 Sketch of a chest in Munster Museum, 2 6-9

1913. Sketchbook 71. NMRS (Lorimer Collection).

FIGURE 17 8 Great Western Terrace, Glasgow. Detail of

staircase. Oak. LS 1990. ,

FIGURE 18 Ardkinglas, Argyllshire. Plasterwork

ceiling. Country Life 34 (27-9-1913): Architectural

Supplement.

FIGURE 19 Monzie Castle, Perthshire. Door furniture

FIGURE 20 Monzie Castle. Bedroom in earlier part of

castle. Lorimer Office scrapbook, SM.

FIGURE 21 Hill of Tarvit, Fife. Buffet niche on

staircase. LS 1990.

FIGURE 22 Hallyburton. Glazed cupboard in dining

room. LS 1990.

FIGURE 23 Charles Rennie Mackintosh. Sketch of a

chair. Sketchbook A 5 . Hunterian Art Gallery,

University of Glasgow, Mackintosh Collection, AC 3118.

FIGURE 24 Charles Rennie Mackintosh. Sketch of a

wooden bench. Sketchbook A 2 . Hunterian Art Gallery,

University of Glasgow, Mackintosh Collection, AC 3053.

FIGURE 25 Charles Rennie Mackintosh. Windyhill.

Dining room. Billcliffe, Charles Rennie Mackintosh

1901.F.

FIGURE 26 Wheeler workshop. Chairs. Dundee City Archives, East Brothers of Lochee Papers GD/MUS

112/3/1.

FIGURE 27 Chair. H. 94cm. w. 53.5cm. d. 56cm.

Trossachs and Perthshire. Highland Folk Museum,

Kingussie, KNB 24. LS 1991.

FIGURE 28 Wheeler workshop. Chairs and cabinet work. Dundee City Archives, East Brothers of Lochee Papers GD/MUS 112/3/1.

FIGURE 29 Philip Clissett. Spindle-back chair. Oak,

elm seat. Cotton, English Regional Chair.

FIGURE 30 Earlshall. Garden room. Photograph National Trust for Scotland, Kellie Castle.

FIGURE 31 Charles Rennie Mackintosh. Stick-back chair

for Glasgow School of Art Library. Billcliffe, Charles

Rennie Mackintosh 1910.9.

FIGURE 32 Cabinet. H. 214cm w. 176cm. d. 77cm.

Flemish or Dutch. Oak with marquetry. Holyrood

Palace.

FIGURE 33 A. Muir. Details of inlay panel on cabinet,

March 1907 [fig. 32]. National Art Survey of Scotland.

NMRS (National Art Survey) NAS 1362.

FIGURE 34 John William Small. Drawing of marquetry on

"Queen Anne's Press". Small, Scottish Woodwork.

FIGURE 35 A. Muir. Details of marquetry panel on

Dutch cabinet, March 1907 [fig. 32]. National Art

Survey of Scotland. NMRS (National Art Survey) NAS

1362 .

FIGURE 36 Cabinet [fig. 32]. Detail of marquetry. LS 199-0.

FIGURE 37 J. F. Smith. Measured drawing of a toilet

stand in Holyrood Palace, Dec. 1895. National Art

Survey of Scotland. NMRS National Art Survey) NAS

1439.

FIGURE 38 Monzie Castle. Drawing room. NMRS (Lorimer Collection) PT/5839.

FIGURE 39 Monzie Castle. Drawing room. NMRS (Lorimer Collection) PR 4631.

FIGURE 41 Scott Morton and Company. Carved panels for

Monzie Castle drawing room. Scott Morton and Company

album, EUL SC E81/27.

FIGURE 42 Hill of Tarvit. Drawing room. Lorimer Office, SM.

FIGURE 43 Scott Morton and Company. Carved wood panel

for Hill of Tarvit drawing room. LS 1990.

FIGURE 44 Ardkinglas. Morning room. Lorimer Office, SM.

FIGURE 45 Hallyburton. Morning room. LS 1990.

FIGURE 46 Hallyburton. Morning room, detail of wood

panelling. LS 1990.

FIGURE 47 54 Melville Street, Edinburgh. Drawing

room. NMRS (Lorimer Collection).

FIGURE 48 54 Melville Street, Edinburgh. Drawing

room. Country Life 34 (27-9-1913): Architectural

Supplement.

FIGURE 49 Sketch of furniture details, including

armoire. Sketchbook 63. NMRS (Lorimer Collection).

FIGURE 50 Wylie and Lochhead. Drawing room. Wylie

and Lochhead 1900 catalogue. GUA HF 48/11/4.

FIGURE 51 Monzie Castle. Drawing room. Lorimer Office, SM.

FIGURE 52 Window shutter. Oak. Louis XV. Museum of

Science and Art, Edinburgh. Rowe, French Wood

Carvings.

FIGURE 53 Panel from cupboard door and fragment of

panel. Louis XIV. Glasgow City Corporation Art

Galleries. Rowe, French Wood Carvings.

FIGURE 54 Hill of Tarvit, Fife. Drawing room. Lorimer Office, SM.

FIGURE 55 54 Melville Street, Edinburgh. Dining room. Lorimer Office, SM.

FIGURE 56 Armoire. Photographed at Gibliston, Fife. NMS Gibliston album.

FIGURE 57 Nathaniel Grieve. Armoire. Lorimer Office album, SM.

FIGURE 58 Scott Morton and Company. Doors for Hill of

Tarvit drawing room. Oak. Scott Morton and Company

album, EUL SC E81/27.

FIGURE 59 Sketch of part of a balustrade made in 1511

for the Court of Holland in The Hague. Sketch made in

1899, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. Sketchbook 63. NMRS

(Lorimer Collection).

FIGURE 60 Hill of Tarvit, Fife. Staircase, from hall. LS 1990.

FIGURE 61 Scott Morton and Company. Staircase at the

Glen, Peeblesshire. Oak. Architectural Review 27

(Jan. - June 1910) .

FIGURE 62 Stone staircase. Rouen. Lorimer Office scrapbook, SM.

FIGURE 63 Morris and Company. Stanmore Hall,

FIGURE 64 Sketch of early eighteenth-century sofa in

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. Sketchbook 63. NMRS (Lorimer

Collection).

FIGURE 65 Sofa. Dutch, early eighteenth-century.

Walnut, with petit point embroidery cover.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, NM 9754.

FIGURE 66 Chest of drawers. Northern Netherlands,

first quarter eighteenth century. Rijksmuseum,

Amsterdam, RBK 1959-24.

FIGURE 67 Sketch of a chest of drawers. Letter to

Dods, 22-12-1896. EUL SC (Lorimer Collection), MS

2484.

FIGURE 68 Tea table. Dutch, first half eighteenth

century. Mahogany. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, inv. 1955

81.

FIGURE 69 Zaandijk. Council chamber in the Town Hall Sluyterman, Old Interiors in Holland.

FIGURE 70 Monzie Castle. Tiled fire surround. LS 1990.

FIGURE 71 Zwolle. Room of the Committee of the

Emmanuel Houses. Sluyterman, Old interiors in Holland

FIGURE 72 Cabinet on stand. Dutch. Walnut veneer. National Trust for Scotland, Kellie Castle.

FIGURE 73 Room from Hindeloopen. Frisian Museum,

Leeuwarden. Sluyterman, Old Interiors in Holland.

FIGURE 74 John F. Matthew. Sketch of a table, drawn

at Adams, Queensferry St. John F. Matthew sketchbook,

SM.

FIGURE 75 Hill of Tarvit. Dining room. Scott Morton and Company album, EUL SC E81/27.

FIGURE 76 Hill of Tarvit. Dining room. Nicoll, Domestic Architecture in Scotland.

FIGURE 77 Monzie Castle. Dining room. LS 1992.

FIGURE 78 Monzie Castle. Dining room. LS 1992.

FIGURE 79 Sketch of firescreen table with workbox

(left). Sketchbook 71. NMRS (Lorimer Collection).

FIGURE 80 Sketch of a revolving bookcase (right).

Sketchbook 66. NMRS (Lorimer Collection).

FIGURE 81 Marchmont, Berwickshire. Saloon. Mid

eighteenth century. Country Life 57 (Jan. - June

1925).

FIGURE 82 Marchmont, Berwickshire. Plan for morning

room. NMRS (Lorimer Collection) BWD/61/51.

FIGURE 83 Sketch of a table seen in Vicenza, 12-5

1923. Sketchbook 71. NMRS (Lorimer Collection).

FIGURE 84 Ardkinglas. Corridor to staircase. LS 1991.

FIGURE 85 Ardkinglas. Upper hall. Nicoll, Domestic Architecture in Scotland.

FIGURE 86 Ardkinglas. Niche fitted with radiator

behind metalwork grill. LS 1991.

FIGURE 87 Ardkinglas. Saloon, by 1908. Nicoll, Domestic Architecture in Scotland.

FIGURE 89 Sketches of furniture seen in Italy.

Sketchbook 71. NMRS (Lorimer Collection).

FIGURE 90 Sketches of furniture seen in Italy.

Sketchbook 71. NMRS (Lorimer Collection).

FIGURE 91 Sketches of furniture seen in Italy.

Sketchbook 71. NMRS (Lorimer Collection).

FIGURE 92 John William Small. Design for a sideboard. Small, Ancient and Modern Furniture.

FIGURE 93 Balmanno Castle, Perthshire. Drawing room. Country Life 69 (Jan. - March 1931).

FIGURE 94 Balmanno Castle. Parlour. LS 1991.

FIGURE 95 Fettercairn, Kincardineshire. Library. Weaver, House and Equipment.

FIGURE 96 Fettercairn. Design for proposed library,

elevation. 1898. NMRS (Lorimer Collection).

FIGURE 97 Balmanno Castle. Drawing room plan. NMRS (Lorimer Collection) PTD/32/44.

FIGURE 98 Balmanno Castle. Billiard room plan. NMRS (Lorimer Collection) PTD/32/45.

FIGURE 99 Balmanno Castle. Hall plan. NMRS (Lorimer Collection) PTD/32/46.

FIGURE 100 Balmanno Castle. Dining room. Country Life 69 (Jan. - March 1931).

FIGURE 101 Balmanno Castle. Plasterwork frieze in

bedroom, executed by Thomas Beattie. LS 1992.

FIGURE 102 Whytock and Reid. Tracing on linen of

design for a breadboard. WRA/O A34. ■

FIGURE 103 Bromsgrove Guild. Light fittings for

Hallyburton. Architectural Review 20 (July - Dec.

1906) .

FIGURE 104 Drawing for fireirons for Aberlour House,

Banff. 1892. Photograph, SM.

FIGURE 105 Walter Camm of Thomas William Camm.

Stained and painted glass window for main stair turret,

Balmanno Castle. H.90cm. w.30cm. LS 1992.

FIGURE 106 Walter Camm of Thomas William Camm.

Stained and painted glass window for main stair turret,

Balmanno Castle. H.93cm. w . 68.5cm. LS 1992.

FIGURE 107 Bedcover. Embroidered in wool by Mrs

Skinner. Shaw Sparrow, Modern Home.

FIGURE 108 Touch House, Stirling. Drawing room

upholstery. LS 1992.

FIGURE 109 Touch House. Linen on bedroom wall. LS 1992 .

FIGURE 110 Monzie Castle. Curtain fabric in library. LS 1990.

FIGURE 111 Balmanno Castle. Veneered panel, door in

drawing room. LS 1992.

FIGURE 112 George Walton. Corner of a bedroom. Shaw Sparrow, British Home.

FIGURE 113 Monzie Castle. Main hall. SM.

FIGURE 114 Westfield, Colinton. Sliding doors between

FIGURE 115 Westfield. Fitted china cabinet in drawing

room. LS 1992.

FIGURE 116 Westfield. Fireplace wall, dining room. LS 1992.

FIGURE 117 Binley Cottage, Colinton. Fireplace in

drawing room. LS 1992.

FIGURE 118 Almora, Colinton. Pierced wood carving on

staircase. LS 1992.

FIGURE 119 The Hermitage, Colinton. Shelving and

cupboard space. LS 1992.

FIGURE 120 Glenlyon, Colinton. Zodiac plasterwork

panel on staircase. LS 1992.

FIGURE 121 Huntly, Colinton. Stained glass window,

ground floor. LS 1992.

FIGURE 122 Balmanno Castle. Fitted bedroom cupboard. LS 1992.

FIGURE 123 Balmanno Castle, Perthshire. Fitted

cupboards in ground floor pantry. LS 1992.

FIGURE 124 Gibliston, Fife. Drawing room, showing

fitted book shelving. Photographed at Gibliston. NMS

Gibliston album.

FIGURE 125 Lympne Castle, Kent. Library bookcase. Weaver, House and Equipment.

FIGURE 126 Lympne Castle. Ante-room to dining room. Weaver, House and Equipment.

FIGURE 127 Thomas Hadden. Wrought iron grill to cover

radiator at Ardkinglas. Country Life 34 (27-9-1913):

Architectural Supplement.

FIGURE 128 Bromsgrove Guild. Light fitting for

Hallyburton. LS 1990.

FIGURE 129 Bromsgrove Guild. Light fitting for saloon

at Ardkinglas. LS 1992.

FIGURE 130 Touch House. Indirect lighting in present

day map room. LS 1992.

FIGURE 131 Ardkinglas. Shower fitting. Aslet, Last.

FIGURE 132 Balmanno Castle. Fitted washstand in

bedroom. LS 1992.

FIGURE 133 Touch House. Fitted washstand in main

bedroom. H.185cm. w.86.5cm. d.56cm. Padouk burr.

LS 1992.

FIGURE 134 Kaare Klint and Carl Petersen (left).

Chair. H. 72cm. w. 56cm. d. 57cm. 1914. Denmark.

Oak and woven cane.

Carl Malmsten (right). Armchair. H. 84.5cm. w.

56.5cm. d. 48.5cm. Sweden. Walnut and woven cane.

McFadden, Scandinavian Modern Design.

FIGURE 135 Probably Wheeler workshop, with carving by

Robert Lorimer. Chair. H. 96cm. w. 42cm. d. 40cm.

Oak. National Trust for Scotland, Kellie Castle. LS

1992 .

FIGURE 136 Wheeler workshop. Chair. H. 96cm. w.

42cm. d. 40cm. Oak. National Trust for Scotland,

FIGURE 137 Chairs after eighteenth-century models (see

cat. 68). Lorimer Office album, SM.

FIGURE 138 Wheeler workshop. Patterns for fretted

chair back splats. Dundee City Archives, East Brothers

of Lochee Papers GD/MUS 112/3/1.

FIGURE 139 Wheeler workshop? Chair. H. 84.5cm. w.

42cm. d. 36cm. Oak. National Trust for Scotland,

Kellie Castle. LS 1990.

FIGURE 140 Embroidered seat cover for chair

illustrated as figure 139. LS 1990.

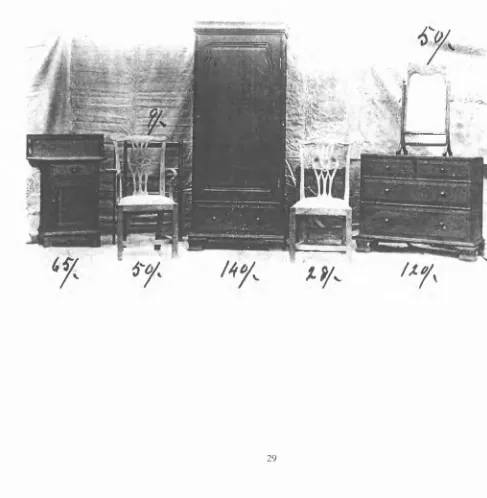

FIGURE 141 Wheeler workshop. Furniture samples. Dundee City Archives, East Brothers of Lochee Papers GD/MUS 112/3/1.

FIGURE 142 Wheeler workshop. Cockpen or "T chair". Dundee City Archives, East Brothers of Lochee Papers GD/MUS 112/3/1.

FIGURE 143 Wheeler workshop. Patterns for front legs and front seat rail of "T chair". Magnus Dunsire and

Sons, Colinsburgh, Fife. PA.

FIGURE 144 Wheeler workshop (William Wheeler the elder at centre). c.1901. Hay, "Chair to a Fiddle".

FIGURE 145 Frank Deas . Kinfauns Castle, Perthshire.

Staircase. Recent English Domestic Architecture 1910.

FIGURE 146 Frank Deas. Kinfauns Castle. Staircase,

pierced frieze below handrail. Recent English Domest-ic

Architecture 1910.

FIGURE 147 Frank Deas. Kinfauns Castle. Carved

finials on newels of staircase. Recent English

Domestic Architecture 1910.

FIGURE 148 Carved finials for newel posts. Architectural Review 27 (Jan. - June 1910).

FIGURE 149 Frank Deas. Cleeve Grange,

Gloucestershire. 1910. Recent English Domestic

Architecture 1911.

FIGURE 150 Scott Morton and Company. Drawing room mantel carvings for Cleeve Grange, remodelled by Frank

Deas, 1910. Scott Morton and Company album, EUL SC

E81/27.

FIGURE 151 Whytock and Reid. Plaster casts. LS 1992.

FIGURE 152 Whytock and Reid. Working drawing for

dressing glass dated 27-2-1907. WRA/O D 8 . LS 1992.

FIGURE 153 Members of the Bromsgrove Guild. c. 1909. From left to right: A. Pillon, Charles Bonnet, Garscia

(seated), Leopold Weiss, Celestino Pancheri, Cyril

White, Louis Weingartner, three unidentified. BGA,

Hartlebury Castle, source material file.

FIGURE 154 Bromsgrove Guild. Drawing of bell push.

H. 23.5cm. w. 17cm. Lorimer Office, SM.

FIGURE 155 Maquette for door handle, w. 12cm. Wood.

Coll. LS. LS 1992.

FIGURE 156 Bromsgrove Guild. Detail of drawings of

door handles. H. 52cm. w. 18cm. (whole). Lorimer '

FIGURE 157 Bromsgrove Guild. Detail of drawings of

door furniture. H. 51cm. w. 16.5cm. (whole). Lorimer

Office, SM.

FIGURE 158 Bromsgrove Guild. Detail of drawings of

door furniture. H. 51cm. w. 16.5cm. (whole). Lorimer

Office, SM.

FIGURE 159 Bromsgrove Guild. Sample door handle, w.

12cm. Brass, silver plated. LS 1992.

FIGURE 160 Bromsgrove Guild. Stock furniture and door

fittings. BGA, Hartlebury Castle 1966/170.

FIGURE 161 Bromsgrove Guild. Dolphin shutter pull.

Briglands, Kincardineshire. 1. 5cm. LS 1992.

FIGURE 162 Bromsgrove Guild. Diana door handle.

Ardkinglas. LS 1991.

FIGURE 163 Bromsgrove Guild. Stag door handle

(matching pattern of fig. 162). Hallyburton. LS 1990.

FIGURE 164 Bromsgrove Guild. Stock door handles.

Diana and quarry handles middle, left and right. BGA,

Hartlebury Castle 1966/170.

FIGURE 165 Bromsgrove Guild. Sample door handle, w.

13.5cm. Cast bronze. Coll. Martin Forrest, Forrest

McKay. LS 1992.

FIGURE 166 Sketch. Pencil on paper. Coll. William

Lorimer. LS 1990.

VOLUME 3

Complete details accompany each plate

CATALOGUE 1 Dressing table. H. 71cm. w. 128cm. d.

59cm. Oak with burr insets. Trustees of the National

Museums of Scotland SVL 10.

CATALOGUE 2 Sideboard. H. 148.5cm. w. 231cm. d.

56cm. Oak. Trustees of the National Museums of

Scotland SVL 18.

CATALOGUE 3 Chest of drawers. H. 130cm. w. 114cm d.

56.5cm. Pale oak with burr insets. National Museums

of Scotland SVL 12. NMS Gibliston album. 3a Trustees

of the National Museums of Scotland.

CATALOGUE 4 Bureau. NMS Gibliston album.

CATALOGUE 5 Chest. H. 65.5cm. w. 131cm. d. 45cm.

Dark oak. National Trust for Scotland, Kellie Castle

LS 1990.

CATALOGUE 6 Settle. H. 86.5cm. w. 152.5cm. d.

39.5cm. Oak. National Trust for Scotland, Kellie

Castle. PA. 6a PA.

CATALOGUE 7 Bedstead. Oak. Studio Yearbook of Decorative Art (1907) 90.

CATALOGUE 8 Bedstead. H. 178cm. w. 91cm. Oak

National Museums of Scotland SVL 13. NMS Gibliston

album.

H. 91.5cm. w. 110cm. d. 50.5cm. Oak. National

Museums of Scotland SVL 5. NMS Gibliston album.

9b Trustees of the National Museums of Scotland

CATALOGUE 10 Bed. w. 110cm. 1. 205cm. Wood and

caning. Private coll. LS 1990.

CATALOGUE 11 Basin stand. H. 73cm w. 92cm. d. 52cm

chestnut? Private coll. LS 1992. 11a LS 1992.

CATALOGUE 12 Wardrobe. H. 200cm. w. 125cm. d. 55cm

Private coll. LS 1990.

CATALOGUE 13 Chair. H. 95.5cm. w. 50cm. d. 43.5cm.

Elm. National Trust for Scotland, Kellie Castle. PA

1990.

CATALOGUE 14 Chair. H. 96cm. w. 55cm. d. 49cm.

Elm. Private coll. PA 1990

CATALOGUE 15 Chair. H. 91cm. w. 53cm. d. 47cm.

Chestnut. Private coll. LS 1992

CATALOGUE 16 Chest of drawers. H. 119cm. w. 115cm.

d. 57cm. Oak and inlaid woods. National Trust for

Scotland, Kellie Castle. PA

CATALOGUE 17 Chest. Oak, with inlaid woods. Studio (Oct. 1896 - Jan. 1897): 197.

CATALOGUE 18 Writing bureau. Oak. 111. Studio 9 (Oct. 1896 - Jan. 1897): 197.

CATALOGUE 19 Buffet. W. 147cm. Elm with inlaid

woods. Shaw Sparrow, British Home.

CATALOGUE 20 Dresser. H. 170cm. w. 90cm. d. 42cm.

Elm. National Museums of Scotland SVL 19.

Christie's, Earlshall lot no. 394.

CATALOGUE 21 Settle. W. 160cm. Oak. Private coll. LS 1990

CATALOGUE 22 Chest. H. 71cm w. 171cm. d. 58cm.

Oak, with inlaid woods. Trustees of the National

Museums of Scotland SVL 16. 22a National Trust for

Scotland, Kellie Castle.

CATALOGUE 23 Chair H. 91cm. w. 60.5cm. d.44cm.

Ash. National Trust for Scotland, Kellie Castle. BP

1992. 23a LS 1992.

CATALOGUE 24 Chair. H. 103cm. w. 58cm. d. 43cm.

Oak. National Trust for Scotland, Kellie Castle. LS

1992. 24a NMRS (Lorimer Collection).

CATALOGUE 25 Sketch on working drawing for cutty-back

stool. Whytock and Reid. LS 1992.

CATALOGUE 26 Chest of drawers. H. 76cm. w. 71.5cm.

d. ‘32.5cm. Oak with inlaid woods. National Trust for

Scotland, Kellie Castle. LS 1990. 26a LS 1990. 26b

National Trust for Scotland, Kellie Castle.

CATALOGUE 27 Napery cabinet. H. 187cm. w. 135cm. d

51cm. Walnut, with inlaid woods. Lorimer Office, SM.

27a National Trust for Scotland, Kellie Castle.

CATALOGUE 28 Bookcase. H. 75cm. w. 37cm. d. 32cm.

Mahogany. Private coll. Lorimer Office, SM.

CATALOGUE 29 Bookcase. H. 94cm. w. 170cm. d. 28cm.

Mahogany. Private coll. Lorimer Office, SM.

Walnut, with fabric upholstery. Private coll. LS 1990

CATALOGUE 31 canape. H. 91cm. w. 184cm. d. 56cm.

Walnut, with fabric upholstery. Private coll. LS 1990

CATALOGUE 32 Chaise longue. H. 84cm. w. 167cm. d.

66cm. Walnut, with fabric upholstery. Private coll.

LS -1990.

CATALOGUE 33 Armchair. H. 89cm. w. 68cm. d. 56cm.

Walnut, with fabric upholstery. Private coll. LS

1990 .

CATALOGUE 34 Stool. H. 53cm. dia. 48cm. Walnut,

with fabric upholstery. Private coll. LS 1990. .

CATALOGUE 35 Side chair. H. 79cm. w. 42cm. d. 38cm.

Walnut. Private coll. LS 1990. 35a LS 1990.

CATALOGUE 36 Sofa. H. 94.5cm. w. 202cm. d. 56cm.

Walnut, with fabric upholstery. National Trust for

Scotland, Kellie Castle. PA

CATALOGUE 37 Bookcase. H. 156cm. w. 82cm. d. 41cm.

pale tulipwood, with marble top. Private coll. LS

1990.

CATALOGUE 38 Bookcase. H. 157cm. w. 84cm. d. 56cm.

Walnut veneer, with marble top. National Trust for

Scotland, Kellie Castle. PA. 38a, 38b PA.

CATALOGUE 39 Desk. H. 76cm. w. 142cm. d. 73cm.

Kingwood. Private coll. LS 1990.

CATALOGUE 40 Table. H. 72cm. w. 45cm. d. 32cm.

Kingwood. Private coll. LS 1990. 40a L S .

CATALOGUE 41 Card table. H. 70cm. w. 82cm. d. 41cm.

Kingwood. Private coll. LS 1992.

CATALOGUE 42 Display cabinet. H. 264cm. w. 146cm.

d. 58cm. Oak. Trustees of the National Museums of

Scotland SVL 11.

CATALOGUE 43 Corner display cabinet. H. 250cm. w.

81cm. Oak. National Trust for Scotland, Kellie Castle

BP 1992.

CATALOGUE 44 Corner display cabinet. NMS Gibliston album.

CATALOGUE 45 Cradle. Oak. Shaw Sparrow, British Home.

CATALOGUE 46 Piano. H. 100.3cm w. 123.2cm. d.

200.2cm. Savage, Lorimer and the Edinburgh Craft

Designers fig. 169.

CATALOGUE 47 Dining table. H. 68.5cm. w. 173cm. d.

89cm. Oak. Lorimer family coll. LS 1990

CATALOGUE 48 Table. H. 69.5cm. dia. 114cm. Oak.

National Trust for Scotland, Kellie Castle. PA

CATALOGUE 49 Table. H. 74cm. w. 166cm., extending to

256cm. d. 119cm. Oak. National Galleries of

Scotland, on loan to the National Trust for Scotland,

Kellie Castle. PA.

CATALOGUE 50 Table. W. 550cm (extended) d. 122cm.

Oak'. Phillips, Scotland, 1989.

CATALOGUE 51 Sideboard. W. 259cm. d. 53cm. Oak. Phillips, Scotland, 1989.

CATALOGUE 52 Bench. H. 46.5cm w. 137cm. d. 46.5cm.

walnut veneer upholstered with horsehair. National

Trust for Scotland, Kellie Castle. LS 1990. 52a LS

1990.

CATALOGUE 53 Chest of drawers. H. 83cm. w. 89cm. d.

55cm. Walnut veneer, marble top. National Trust for

Scotland, Kellie Castle. PA.

CATALOGUE 54 Tea table. Walnut. Lorimer Office album, SM.

CATALOGUE 55 Armchair. Elm? with burr. H. 93cm. w.

58cm. d. 48cm. Private coll. LS 1991.

CATALOGUE 56 Dressing glass. H. 180cm. Private coll.

LS 1990. .

CATALOGUE 57 Dressing glass. Walnut. H. 77cm. w.

39cm. National Trust for Scotland, Kellie Castle. LS

1992 .

CATALOGUE 58 Tea table. Phillips, Scotland 1990 58a National Trust for Scotland, Kellie Castle.

CATALOGUE 59 Armchair. H. 84cm. w. 58cm. d. 55.5cm.

coll. Hew Lorimer. PA.

CATALOGUE 60 Bureau bookcase. H. 231cm. w. 94cm. d.

53cm. Mahogany. Trustees of the National Museums of

Scotland SVL 14. 60a Trustees of the National Museums

of Scotland.

CATALOGUE 61 Corner chair. H. 76cm. w. 46cm. d.

46cm. National Museums of Scotland SVL 2. NMS

Gibliston album.

-CATALOGUE 62 Corner chair. H. 79cm. w. 62cm. d.

58cm. Lorimer Office album, SM.

CATALOGUE 63 Tea table. Walnut. Shaw Sparrow, Modern Home.

CATALOGUE 64 Carving table. H. 71cm. w. 136.5cm. d.

76cm. Mahogany. Private coll. LS 1992.

CATALOGUE 65 Sideboard, H. 96.5cm. w. 229cm. d.

75.5cm. Mahogany. Private coll. LS 1992.

CATALOGUE 66 Table. H. 84cm. w. 152cm. d. 65.5cm.

Walnut. Private coll. LS 1992.

CATALOGUE 67 Card table. H. 72.5cm. dia. 94cm.

Stained mahogany. Private coll. LS 1992.

CATALOGUE 68 Armchair. H. 98cm. w. 53cm. d. 45.5cm.

coll. Hew Lorimer. LS 1992.

CATALOGUE 69 Firescreen table. H. 93cm. w. 61cm. d.

45cm. National Trust for Scotland, Kellie Castle. PA

CATALOGUE 70 Revolving bookcase (right). Mahogany Phillips, Scotland, 1989.

CATALOGUE 71 Armchair. Mahogany. Christie's, 1984.

CATALOGUE 72 Side chair and armchair. Walnut. Christie's, 1984.

CATALOGUE 73 Side chair. Burr elm and walnut. Christie's, 1984.

CATALOGUE 74 Tripod table. W. 61cm. Mahogany. Christie's, 1984.

CATALOGUE 75 Table. W. 183cm. Walnut. Christie's, 1984.

CATALOGUE 76 Basin stand. W. 122cm. Mahogany.

Christie's, 1984.

CATALOGUE 77 Table. Private coll. NMS Gibliston album.

CATALOGUE 78 Display table. H. 76cm. w. 121cm. d.

49cm. Private coll. LS 1991. 78a LS 1991.

CATALOGUE 79 Table. H. 69cm. dia. 83cm. Private

coll. LS 1991.

CATALOGUE 80 Desk. H. 73cm. w. 122cm. d. 60cm.

Private coll. LS 1991.

CATALOGUE 81 Sofa table. H. 74cm. w. 305cm. d.

74cm. Ash. Private coll. LS 1991.

CATALOGUE 82 Desk. H. 94cm. w. 153cm. d. 65cm.

Walnut. Private coll. LS 1991. '

CATALOGUE 83 Table. H. 69cm. dia. 82cm. Ash

Private coll. LS 1991. •

CATALOGUE 84 Table. H. 72cm. w. 121cm. d. 62cm.

Oak. Private coll. PA 1991.

CATALOGUE 85 Display table. H. 71cm. w. 244cm. d.

61cm. Oak. NMS Gibliston album.

CATALOGUE 86

Display table. H. 75cm. w. 150cm. d. 44cm.

Oak. National Museums of Scotland SVL 6. NMS

Gibliston album.

CATALOGUE 87 Games table. Oak, with marble top. NMS Gibliston album.

CATALOGUE 88 Table. H. 71cm. w. 152.5cm. d. 84cm.

Oak. National Trust for Scotland, Kellie Castle. PA

1992 .

CATALOGUE 89 Display table. H. 82cm. w. 118.5cm.

Walnut. Private coll. LS 1991.

CATALOGUE 90 Stool. H. 42cm. w. 58cm. d. 31cm.

Sabicu with magnolia veneer. Private coll. LS 1991.

CATALOGUE 91 Chair. H. 80cm. w. 42cm. d. 39cm.

Private coll. LS 1991.

CATALOGUE 92 Library table. H. 73.5cm. w. 246.5cm.

d. 77.5cm. Chestnut. Private coll. LS 1990.

CATALOGUE 93 Etagere. H. 68cm. w. 73cm. d. 30cm.

Walnut. Private coll. PA 1991. 93a PA.

CATALOGUE 94 Table. H. 71cm. w. 176cm. (extending to

274.5cm.) d. 91.5cm. Oak. Private coll. PA 1991.

CATALOGUE 95 Table. H. 71cm. dia. 107cm. Oak.

Private coll. PA 1991.

CATALOGUE 96 Sideboard. H. 82cm. w. 232cm. d. 57cm.

Oak. Private coll. PA 1991.

CATALOGUE 97 Side table. H. 84cm. w. 225cm. d.

60cm. Oak. Private coll. PA 1991. .

CATALOGUE 98 Press cabinet. H. 246cm. w. 107cm. d.

69cm. Oak. Private coll. PA 1991.

CATALOGUE 99 Bed headboard. H. 137cm. w. 92cm.

Walnut veneer. Private coll. PA 1991.

CATALOGUE 100 Frame. Lorimer Office album, SM.

CATALOGUE 101 Overmantel (detail) Lime, gilded.

Touch House, Stirling. LS 1992. 101a WRA, LS 1992.

CATALOGUE 102 Bookcases. Lower h. 84cm. w. 81cm. d

29.5cm. Upper h. 60.5cm w. 60.5cm. d. 22.5cm. Coll

Hew Lorimer. PA.

CATALOGUE 103 Table. W. 132cm. Walnut, mahogany and

marble. Phillips, Scotland, 1989.

CATALOGUE 104 Chest of drawers. H. 100.5cm w.

75.5cm. d. 48.5cm. Elm and walnut. National Trust

for Scotland, Kellie Castle. LS 1990. 104a LS 1990.

CATALOGUE 105 Display cabinet. H. 87cm. w. 119cm.

d. 40cm. Walnut. National Trust for Scotland, Kellie

Castle. LS 1990.

CATALOGUE 106 Bookcase. H. 80cm. w. 80cm. d. 30cm.

NOTE ON LAYOUT OP THESIS AND

ILLUSTRATIONS

For reasons of coherency and accessibility, the

following format has been adopted. Volume One contains

the text, organised thematically into five chapters

discussing Lorimer's domestic furniture designs and how

the furniture is arranged in the interior. Volume Two

contains photographs of interiors at Lorimer

commissions, drawings and sketches by the architect,

and comparative material by other architects and

designers.

Yet, Lorimer did not conceive of his furniture as

subordinate to the interior, and thus it would do his

designs little justice to present them in this manner.

For this reason, the illustrations of the moveable

furniture referred to in the text are arranged in a

separate volume (Three) accompanied by a brief

descriptive catalogue.

This catalogue is not intended as a definitive

list of Lorimer's furniture designs. Furniture is far

more ephemeral than architecture; the majority of

Lorimer's designs were never photographed, and the

requirements of confidentiality have hindered the

tracing of items following their sale. Nor has it been

possible to compile a catalogue by way of the drawings

preserved by Whytock and Reid. The documentation on

these was not always consistent; many of the early

drawings have been lost or damaged, and of the remnant

some contain only clients' surnames. In addition,

Lorimer's practice of repeating designs has made the

concept of a complete catalogue impracticable.

However, the presence of a fragmentary collection

of working drawings has been invaluable in the

compilation of documentary information on some of the

designs discussed. The furniture chosen for

examination in this thesis spans Lorimer's career from

his early participation in the Arts and Crafts

Exhibitions, to his work at Touch House in

Stirlingshire. Yet a thematic rather than

chronological approach to the catalogue has been

adopted, following the order of the text in Volume One.

In this way, the individual items of furniture may be

more easily studied in conjunction with the text and

ABSTRACT

• Chapter 1, entitled "The Scottish Tradition",

builds on the early twentieth-century consensus that

Lorimer had resuscitated a moribund Scottish tradition

of design. While critics have examined the Scottish

roots of Lorimer1s architecture, the native sources of

his furniture design have received little corresponding

attention. This section aims to demonstrate the ways

in which Lorimer's interest in historical Scottish

architecture and woodwork informed his interior and

furniture design. In particular, his use of vernacular

and regional forms is juxtaposed with the revival of

traditional types and motifs he shared with

contemporary designers.

Complementing a concern with indigenous design is

Lorimer1s interest in continental antique furniture.

Lorimer's personal collection, and those of his

clients, may be identified as formative in the

development of his design. Chapter 2 examines the main

sources, against the social background of Scottish

furniture and interior design during the period. The

circumstances of the commissions discussed here reveal

Lorimer1s combination of the roles of architect and

interior designer, the focus of Chapter 3 on Lorimer's

wide-ranging activities at Balmanno Castle, Perthshire.

Chapter 4 seeks to redress the balance between

Lorimer as traditionalist and agent for reform,

particularly in the area of design education. It will

be argued that his own design innovations were

secondary to the latter achievement. His attitudes to

industrial design and handcraft are considered here,

which leads to the final chapter on workmanship. This

section is comprised of an in-depth study of Lorimer's

working relationship with the executants of his

designs; the variant use of handwork and machinework is

discussed, and finally some attempt is made to discern

and acknowledge the peculiar contributions of designer

In a letter to Hermann Muthesius, Charles Rennie

Mackintosh expressed generous, though unrequited,

admiration for his Edinburgh contemporary, Robert

Lorimer: "We consider him the best domestic architect

in Scotland and admire his work very much".l With

ninety years' hindsight, this is a striking concession

from one whose own reputation has come to eclipse that

of Lorimer, at home, and even more so abroad.

Mackintosh's furniture designs, canonised as

International Masterpieces, have for many years been

reproduced by several companies; his work has an

unrefuted place in the literature of modern furniture

design, and has been approbated in Scotland as a

cultural symbol, having the same emotive resonance as,

for example, the Eiffel Tower, or Gaudi's Sagrada

Familia.

Sightings of Lorimer1s name in the canon of modern

design are rather more desultory. His furniture has

suffered from its inevitable comparison with

Mackintosh's work, the tendency being to dismiss it as

retrogressive, beside the progressive achievement of

the Glasgow designer. After Lorimer's death in 1929,

his traditionalist and craftsmanly approach to

furniture was at variance with the machine aesthetic of

much modern work, such as the glass and tubular steel

productions by the Bauhaus, or Le Corbusier, which

again have been sanctioned, and familiarised, through

reproduction.

However, renewed appreciation of regionalism, and

admiration for the qualities of craftsmanship,

exemplified, for instance, by the success of John

Makepeace and his School for Craftsmen in Wood, may

augur a more sympathetic assessment of a designer for

whom “material texture" was fundamental, and who, as

early as 1916, made a plea for the greater utilisation

of native rather than exotic timbers.2 in recent years

Lorimer1s furniture has appeared in survey literature

on Scottish design.2 That a suite of Lorimer tables

was exhibited in 1990 at Didier Aaron, Inc., New York,

is perhaps indicative of a wider and more receptive

audience for his quiet paraphrases of traditional

design.4

During Lorimer's career, his furniture received

some critical attention, with illustrations and/or

discussion appearing in the Studio, the Builder, and

the American journals House and Garden and House

Beautiful. Shortly after Lorimer's death, Christopher

Hussey included a review of the architect's furniture

in his 1931 monograph for Country L i f e .5 within the

context of a book covering the entirety of the

architect's output, this was by necessity limited in

scope. The same format was followed by Peter Savage in

1980; although a chapter was devoted to "The Edinburgh

Craft Designers", the major focus was again

architectural.6

The aim of this work is to present a more thorough

investigation of Robert Lorimer1s domestic furniture

designs. The research of Hussey and Savage has been

taken as a starting point, leading to a study of the .

extant office material, exclusively in relation to

domestic furniture and interior design. Although the

primary focus is on individual items of furniture,

consideration is accorded to the interiors for which

these were created. Lorimer's profession as an

architect in many ways compels such an approach, as

often the furniture is inseparable from its context.

The extensive material preserved from the

Lorimer/Matthew Office, such as account books,

abstracts and correspondence, discloses much

documentary information on the furniture designs.7

This is supplemented by the documentation recorded on

the working drawings for Lorimer designs, made by the

Edinburgh cabinetmakers Whytock and Reid. Until now,

this large collection has not been utilised for

verification of dates, clients and materials. Further,

communicated through these drawings is invaluable

evidence regarding the translation of Lorimer's designs

by draughtsmen and executants. Savage's discovery of

the Dods correspondence enabled him to discuss this,'to

an extent, from Lorimer1s perspective, yet the Whytock

and Reid drawings permit a wider and more thorough

analysis of working methods and relationships between

designer and workmen.

' However, the objective of this study has not been

solely to elaborate upon previous scholarship. The

Arts and Crafts context of Lorimer's furniture,

emphasised by Savage, must be expanded; Hussey's

appraisal of Lorimer's work in terms of modernism must

be engaged; and the tendency to summarise the furniture

designs purely as revivalist, should be reviewed.8

Although comparisons with Mackintosh's furniture are

almost inevitable, it is not the intention here to

recast Lorimer as a more moderate modern than

Mackintosh.

In discussing the work of this period of flux, the

danger arises of evaluating too much as simply •

transitional. Lorimer's career began in the late

Victorian period and continued well into the era that

saw the first monuments of the Modern Movement, and the

development, by architects, of such progressive

furniture as the cantilever tubular steel chair. 1929,

the year of his death, saw the introduction of Ludwig

Mies van der Rohe's influential "Barcelona chair",

still today a potent symbol of modernity. While it is

important to place Lorimer's work against such

developments, the full relevance of his furniture does

not lie in its rejection of the more florid sort of

Victorianism, or the extent to which it forecasts more

radical experimentation with form; in fact, Lorimer1s

design tends to elude classification as either

departure or precursor.

• The questioning of the assumptions to which

Lorimer's design has been prey has provided scope for

1 Charles Rennie Mackintosh, letter to Robert Lorimer, 5-1-1903, qtd. in Alistair Moffat and Colin Baxter, Remembering Charles Rennie Mackintosh (Lanark: Colin Baxter Photography, Ltd., 1989) 40.

2 Robert Lorimer, "The Neglect of Home Timber," Country Life 39 (Jan. - June 1916): 456-458.

2 For example, Wendy Kaplan, ed., Scotland Creates:

5000 Years of Art and Design (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1990) 153, 155-8.

4 The suite of dining-room tables from Rowallan appeared in the exhibition "Memories and Visions: Historic Revivals and Modernism, England 1850-1900," Didier Aaron Inc., New York, Nov. 8 - Dec. 1, 1990.

5 Christopher Hussey, The Work of Sir Robert Lorimer

(London: Country Life. Ltd., 1931).

6 Peter Savage, Lorimer and the Edinburgh Craft

Designers (Edinburgh: Paul Harris Publishing, 1980).

7 John Fraser Matthew was articled to Lorimer in 1893,

became office manager, then in 1927, Lorimer's partner. The office papers were preserved by him, and later his son, Stuart Matthew, who donated the larger portion to

Edinburgh University Library, and to NMR S. In this

thesis, reference shall be to the "Lorimer Office", until 1927.

8 See, for example, Elizabeth Cumming's interpretation

CHAPTER 1

"To be rooted is perhaps the most important and least recognized need of the human soul.

It is one of the hardest to define." Simone

Weill

What defines Lorimer1s work as Scottish? And how

is this expressed in his furniture design? It has long

been acknowledged that his architecture fulfilled a

need for rootedness. During his lifetime, he was

recognised as an architect resuscitating a moribund

tradition; following his death in 1929, his achievement

was assessed in the light of a Scottish Renaissance,

with Lorimer lauded a Robert Burns of architecture, a

revitaliser of the v e r n a c u l a r .2 Peter Savage stressed

the seminal experience of the land and its people to

Lorimer's work, and rightly so.3

Yet, what is Scottish about Lorimer's furniture,

is a question that has not satisfactorily been

resolved. It is easier, certainly, to recognise the

influence of the national style on Lorimer's

architecture. Where restoration was the object, the

existing building obviously determined the character of

the finished work. New houses, such as Rowallan or

Ardkinglas, clearly articulate their Scottish Baronial

borrowings, and their debt to vernacular architecture.

What is less clear is how the furniture designed

for such homes shares the same roots. Elizabeth

Cumming has maintained that traditional Scottish pieces

inspired the simple forms of Lorimer's furniture, yet

illustrates a table with exaggeratedly curvilinear

stretcher and supports, and a linen cupboard with a

marquetry design of swans and rabbits.4 Savage, on the

other hand, concluded that Lorimer had been restricted

by a dearth of old Scottish furniture, and consequently

he gave little space to examining the Scottish quality

of any of Lorimer's furniture designs.5 jn this, his

views are close to those of Hussey, who discussed the

eclecticism of Lorimer's furniture design against a

general British Arts and Crafts background.

It shall be posited here that Lorimer was hindered

neither by paucity of Scottish sources, nor by a

restrictive definition of what is Scottish in Scottish

design. The need for roots was one he recognised and

addressed in his architecture and furniture design;

with regard to the latter, the methods by which he met

this need deserve closer attention.

SELF DEFINITION

The late nineteenth century in Scotland was

markedly informed by a quest for self definition. Not

that this was a novel preoccupation; the exploration of

the Scottish tradition in literature had been initiated

much earlier. Architecturally, it had found expression

in, for instance, the work of William Burn and David

Bryce, and the publications of R. W. Billings, David

MacGibbon and Thomas Ross. The latter part of the

nineteenth century, however, saw the spread of this

concern to as yet uncharted areas. For instance, John

William Small1s publications on historic Scottish

woodwork and furniture were pioneering in their attempt

to raise consciousness of Scotland's design heritage in

the areas of woodwork and furniture. Concurrently,

seminal research was being conducted into the areas of

Scottish folklore and folk m u s i c .46 This was

predicated on the increasing recognition of the

contribution of regional and vernacular traditions to

Scottish identity.

James Nicoll's Domestic Architecture in Scotland,

published in 1908, summarised the prevalent ideas on

the relevance of the Scottish tradition to modern house

building; an architecture derived from native

historical examples, constructed from mainly indigenous

materials, complemented by limited use of imported

ones, was the architecture best fitted to the country's

geography, climate and psyche.8 Yet, while the

validity of the vernacular had been affirmed from the

second quarter of the nineteenth century, a

corresponding programme for the furnishing of modern

domestic architecture remained nebulous.7

HISTORICAL SOLUTIONS

The romantic nationalism that had informed

architecture seemed to proffer an opportunity, if not

an obligation, to infuse interior design with the same

sentiment. Sir Walter Scott, as lodestar of the

Scottish romantic movement, had furnished Abbotsford

from 1817 with a richly eclectic mixture of antiques

and modern furniture, some of which had been made by

the English cabinetmaker, George Bullock. The antiques

ranged from such macabre relics as the sixteenth-

century Italian chest that had reputedly entombed

Ginevra of the "Mistletoe Bough", to the Wallace chair,

purportedly made of wood from the house in which

William Wallace had been murdered.8

Such items were valued primarily for their

associational qualities, and clearly could not be the

basis for the development of a national style of

furnishing adapted to twentieth-century requirements.

Billings and MacGibbon and Ross included a number of

interior views in their publications, and certainly

their researches were to inspire the composition, by

architects such as Burn and Bryce, of interiors after

historic models.9 Yet, the meticulous historical

detail of many of these schemes rendered them, by the

late nineteenth century, too obviously antiquarian.

Neither did the royal residence at Balmoral offer

a persuasive alternative. Rebuilt and furnished for

Victoria and Albert during the 1850s, the pervasive

tartan and stags' heads touted an ostensible

Scottishness that bore little relation to authentic

Scottish tradition. Moreover, the taste expressed here

had been called into question from the castle's

completion: "...the thistles are in such abundance that

they would rejoice the heart of a donkey if they

happened to look like his favourite repast, which they

don't."19 The challenge which presented itself to

Lorimer and the Scottish designers of his generation

was to replace the ersatz Balmoral thistle with

something both more palatable and identifiable.

Appositely, an assertion of Scott's seems to have

pointed to a possible solution: "Every Scottishman has

a pedigree. It is a national prerogative, as

unalienable as his pride and his poverty."H The

demonstration that Scotland's traditional poverty had

not thwarted a Scottish tradition of design was the

task assumed by John William Small, whose principal

importance lies in his role as propagandist for

historical Scottish woodwork. His first major

publication, Scottish Woodwork of the Sixteenth and

Seventeenth Centuries (1878), explicitly professed to

achieve for Scottish woodwork what had been achieved

for architecture - the identification and recording of

venerable e x a m p l e s .12 &s importantly, Small posited

that just as national characteristics had been

identified in architecture, the same might be

demonstrated for w o o d w o r k . 1 2

The agenda in Small's vocation was the

establishment of a canon of historical Scottish design

and, partially through this, the invigoration of the

country's modern furniture manufacture.14 Hence,

examples of Scottish woodwork were proposed as sound

models for imitation, with details and measurements

provided. Small himself reproduced seventeenth-century

furniture, both as proprietor of the North British Art

Furniture Works, and after the company's closure.15

The lists of subscribers to Small's works indicate

that his programme did engender the interest of his

intended audience. Cabinetmakers such as Morison and

Company of Edinburgh, William Scott Morton, Matthew

Pollock of Beith, and Gillows of Lancaster are among

those named. The influence of these publications was

further disseminated through illustrated reviews and

extracts appearing in trade journals such as the

Builder and the Furniture Record. 16 e importance of

periodical literature to the communication of Small's

agenda should not be underestimated. In conjunction

with his Scottish Woodwork. Leaves from mv Sketchbooks

(1880), and Ancient and Modern Furniture (1883), Small

contributed text and sketches of Scottish work to the

Cabinet Maker, with the expressed intention that

“maybe, some [furniture-makers] may get hints therefrom

which will be useful and beneficial in their everyday

work".17

A number of instances can be identified of the

reproduction by furniture manufacturers of Small's

chosen examples. The Third Marquis of Bute

commissioned the reproduction of a chair reputedly from

Lochleven Castle, recorded as Plate 42 in Scottish

W o o d w o r k .IS Messrs. Alexander and Howell, a Glasgow

cabinetmaking firm, exhibited at Edinburgh in 1886

their interpretations of Archbishop Sharp's cabinet,

and a cabinet from Linlithgow Palace, which had

appeared as Plates 1 and 7 in Scottish Woodwork.19

One of Robert Lorimer1s earliest fittings was his

close copy for Earlshall Castle, Fife, of the Falkland

Palace Screen, again illustrated by Small (fig. I).2®

At Earlshall, this reproduction might seem appropriate,

given the antiquarian leanings of Lorimer's client, R.

W. R Mackenzie, who had been a Fellow of the Society of

Antiquaries of Scotland since 1882.21 photographs of

the Earlshall interiors appearing in Architectural

Review in 1919, give some indication of Mackenzie's

personal collections of antique furniture and woodwork,

which included several Scottish caqueteuse chairs.

(figs. 1, 2).22

Encouraged, assuredly in part, by Small's example,

furniture manufacturers began reproduction on a wider

basis of authentic Scottish types such as the

caqueteuse armchair. This pattern seems to have

exercised a symbolic appeal, becoming almost synonymous

with historic Scottish design itself. Small had

identified the type as native in Scottish Woodwork,

although the earliest usage of the term caqueteuse in

relation to Scottish examples may have appeared in 1904

in Percy Macquoid's History of English F u r n i t u r e .23

Original caqueteuses were exhibited in Glasgow at the

1888 Exhibition, to which Small lent an example from

Neidpath C a s t l e .24 gy this date the importance of the

collection of the Aberdeen Trades Guilds' caqueteuses

was acknowledged; in a book published as a memorial to

the exhibition, it was asserted, "The Aberdeen chairs

form the finest existing illustration of the taste and

skill of Scottish craftsmen in the sixteenth and

seventeenth c e n t u r i e s 25 The Aberdeen caqueteuses

were again exhibited in Glasgow at the 1901

International Exhibition.26

Small's North British Art Furniture Works

manufactured copies of Reverend James Guthrie's '

caqueteuse in the McFarlane Museum, Stirling, as well

as upholstered examples,27 an(j Scott Morton and Company

of Edinburgh reproduced the type.28 The sale of Sir

William Fraser's substantial collection of historic

Scottish furniture in Edinburgh on December 3, 1898,

probably led to Wylie and Lochhead's reproduction of a

caqueteuse from Dunnottar Castle, previously belonging

to Fraser.29

However contextually apposite the Falkland Palace

Screen might have been for Earlshall, Lorimer early

recognised that the reproduction of Scottish

"touchstones" could not present an adequate formula for

modern home furnishing. The sentiments that had come

to surround much Scottish antique woodwork interfered

with the proper appraisal of its aesthetic qualities,

and sometimes its historical authenticity. This was

well demonstrated by the reconstruction of the Bishop's

Castle, by James Sellars, at the 1888 Glasgow .

Exhibition. Assembled here was purportedly the largest

collection of Scottish antiquities ever publicly

d i s p l a y e d .30 Regarding the furniture specifically,

romantic associations, the insistence on ascribing an

often aristocratic provenance, and the pervasive

Mariolotry, could obscure concerns over veracity, style

or form.31 Queen Margaret's prolifically carved

sideboard is but one example (fig. 3).32 <ptie Bishop's

Castle was reviewed in terms of a presentation of the

"heirlooms of Scottish Protestantism", the "souvenirs

of the religious struggles of the S c o t s".33

The ascent of the "relic setting" was a logical

extension of Scotland's self-reflexive concern with its

monarches and religious luminaries. As Ian Gow has

observed, Holyrood Palace "could provide a rallying

point for incipient romantic nationalism", culminating

in Mary Queen of Scots' anachronistically furnished

B e d c h a m b e r.34 John Knox's house in the High Street,

Edinburgh, endured a similar lack of discrimination,

having been acquired for the public in 1846.35

Arranged as a period setting as well as museum, the

house contained letters, portraits, articles belonging

to Knox and furniture contemporaneous with his time in

r e s i d e n c e .36 However, as MacGibbon and Ross were to

observe, most of the internal panelling was recently

constructed, although some carved woodwork probably

dated from the seventeenth c e n t u r y .37 Even as a

pastiche, though, the house carried an authority