Volume8,Issue1 2011 Article41

Emergency Management

Active Shooter on Campus: Evaluating Text

and E-mail Warning Message Effectiveness

David N. Sattler,

Western Washington University

Katy Larpenteur,

Western Washington University

Gayle Shipley,

Western Washington University

Recommended Citation:

Sattler, David N.; Larpenteur, Katy; and Shipley, Gayle (2011) "Active Shooter on Campus: Evaluating Text and E-mail Warning Message Effectiveness,"Journal of Homeland Security and Emergency Management: Vol. 8: Iss. 1, Article 41.

and E-mail Warning Message Effectiveness

David N. Sattler, Katy Larpenteur, and Gayle Shipley

Abstract

Recent events involving active shooters on campus underscore the importance of promptly notifying the campus community so students, faculty, and staff can take protective action as the incident develops. This study (a) developed warning messages informing the campus of an active shooter that can be delivered to cellular telephones and e-mail accounts, and (b) assessed their effectiveness. Participants were 264 (76 men, 188 women) undergraduate students at Western Washington University who indicated their understanding of and anticipated responses to text and e-mail messages. Participants indicated that they understood the instructions and would take the actions indicated in the messages. The results indicate text and e-mail messages are effective ways to notify and provide coherent instructions to the community during a life threatening emergency. This approach may be modified to create templates for other emergencies and disasters (e.g., earthquakes, tornadoes).

KEYWORDS: active shooter, warning message, emergency warning, emergency preparedness, message template, text messages, e-mail messages

Author Notes: The warning messages were written by David N. Sattler, Gayle Shipley, Paul Cocke, and the Western Washington University Emergency Management Committee. We thank the editor, three anonymous reviewers, and Virginia Shabatay for their helpful comments. Address correspondence to David N. Sattler, Department of Psychology, Western Institute for Social Research, Western Washington University, Bellingham, Washington 98225-9172; email: david.sattler@wwu.edu.

United States federal law requires higher education institutions to “immediately notify the campus community upon the confirmation of a significant emergency or dangerous situation involving an immediate threat to the health or safety of students or staff occurring on the campus” (Jeanne Clery Disclosure of Campus Security Policy and Campus Crime Statistics Act, Public Law 110-315; U.S. Department of Education, 2008).

Recent events across the country (e.g., active shooter at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University; University of Alabama) underscore the importance of promptly notifying students, faculty, and staff so they can take protective action as an incident develops. Between 2005 and 2007, there were 12,181 aggravated assaults and 104 murders on public and private 4-year college campuses (U.S. Department of Education, 2008).

Higher education institutions are taking new measures to notify the campus community about an emergency situation, including the use of text messages sent to cellular telephones and e-mail messages. However, few projects have assessed the effectiveness of these messages or their ability to accurately convey information about an event. This is especially important in the case of text messages sent to cell phones because they are limited in length and typically have an upper limit of 160 characters and spaces per message (Plummer & Johnson, 2008). Can vital information be conveyed in 160 characters or less? Can receivers comprehend abbreviated information contained in a text message? Will recipients trust the source of the e-mail and text messages?

This project assesses the effectiveness of text messages and e-mail messages that were developed to be issued in the case of an active shooter on a university campus. Cell phone text messaging and e-mail have several benefits when compared to more traditional media (e.g., television, radio). Most students own a cell phone, carry the phone with them on campus, and use e-mail and the internet (Junco & Cole-Avent, 2008). While on campus, students likely have greater access to a cell phone or e-mail than to television or radio. Furthermore, text and e-mail messages are issued and delivered by the original source of information (viz., the institution’s communications office; Lindell & Perry, 2004). However, text messaging and e-mail also have limitations. Cell phones and the internet may be more vulnerable to service disruption than television or radio. There are concerns as to whether all necessary information can be included in a text message that is limited to 160 characters and spaces.

Effective warning messages must (a) describe the situation clearly so that people understand the danger, (b) be issued by a credible source, (c) include specific information indicating the location and time of the event, and (d) state

protective actions (Mileti & O’Brien, 1992; Mileti & Peek, 2000). The message must include sufficient details about the situation in order for the recipient to perceive a threat, and have trust and confidence in the message source, content, and recommendations. If more than one message is issued, subsequent messages must be consistent with prior messages in order to avoid contradictory and confusing information.

The characteristics of individuals who receive the message (e.g., gender, age, self-efficacy, disaster experience, locus of control) influence the likelihood whether they will perceive the situation as an emergency and take protective action (Mileti & Peek, 2000; Riad, Norris, & Ruback, 1999; Sjoberg, 2000). For example, someone low in self-efficacy may be less confident in his or her ability to take preventive actions (Lindell & Perry, 2004). Individuals with an internal locus of control (the belief that the individual can control what happens to him or her) tend to take more preventive actions in disasters than those with an external locus of control or fatalistic beliefs (Sattler, Kaiser, & Hittner, 2000). Other factors that may influence risk perception include community involvement and the behavior of other people in the same situation (Lindell & Perry, 2004; Peek & Mileti, 2002). Most research assessing warning message effectiveness has focused on natural and technological disasters (e.g., Riad, Norris, & Ruback, 1999; Sattler & Marshall, 2002; Smith-Jackson, 2006). Few studies have examined text or e-mail messages designed to notify campus communities of active shooters or other emergencies (e.g., earthquakes, tornadoes).

The current study extends past research by assessing text and e-mail warning messages concerning an active shooter on campus. “An active shooter is a person who appears to be actively engaged in killing or attempting to kill people in a populated area; in most cases active shooters use firearm(s) and there is no pattern or method to their selection of victims. These situations are dynamic and evolve rapidly, demanding immediate deployment of law enforcement resources to stop the shooting and mitigate harm to innocent victims” (Indiana University Police Department, 2009). Because these situations are dynamic and evolve rapidly, university communications offices, the university police department, or other appropriate departments will be required to quickly write coherent messages. However, it can take time to write and edit the information to fit within the 160 character limit for text messages. Furthermore, because clarity and accuracy of the information are essential, it would be beneficial to know whether students, faculty, and staff interpret and understand the information in the messages (via a pilot study).

The authors of this study and the Emergency Management Committee at Western Washington University have prewritten text and e-mail message templates, based on recommendations by police officials, emergency management departments at universities across the country, and disaster researchers (Lindell &

Perry, 2004; Peek & Mileti, 2002). The messages were written over a period of months and underwent numerous revisions. Table 1 presents these templates and shows that more information about an incident is presented based on the anticipated developments. The messages include specific information concerning the location of the incident and recommended actions students, faculty, and staff should take.

In addition to assessing the clarity and comprehensibility of these text and e-mail messages, this study also evaluates the relationships among demographic characteristics, perception of risk, trust, locus of control, experience with disasters, self-efficacy, comprehension of the message, and predicted action the individual might take in response to the message. Although the e-mail messages contain more characters and words than the text messages, both include the same critical information. We expected that the text messages and e-mail messages would effectively convey the critical features of the situation and protective actions to take. Based on past research, we expected that self-efficacy, internal locus of control, greater experience with emergencies, higher trust in the source, and perceiving a higher risk in the situation would be positively associated with intent to take protective actions and actions consistent with the message content.

Method

Design and Participants

The design was a 2 (Delivery type: cell phone text message, e-mail message) x 6 (Message content: serious threat on campus, serious threat on campus and leave the area, serious threat on campus and stay in the location (“shelter in place”), an active shooter on campus, update to the situation, and the situation is resolved) between-subjects analysis of variance (ANOVA).

The participants were 264 (76 men, 188 women) undergraduate students at Western Washington University. The average age was 19.3 years (SD = 2.3). Most participants were Euro American, (81%), not married (97%), and did not have children (99%). About half had training in CPR, first aid, or lifesaving (54%) and about one-third (30%) had experienced a life threatening event.

Materials

A consent form described the purposes of the study, and all materials were printed on 8 1/2” x 11” paper. In the text message conditions, participants saw a large image of a cell phone with the text message presented within the cell phone. In the e-mail conditions, participants saw a large image of a computer monitor with the e-mail message presented within the monitor. Table 1 shows the e-mail and

text messages. After reading the message, participants answered questions presented in the following sections on a survey.

Demographic characteristics. Nine items asked for demographic information, training in CPR, First Aid, or Lifesaving, knowledge about campus shootings, and experience with a life threatening situation. Participants indicated their answers by checking a box or writing their answer.

Message clarity. Twenty-four items assessed the clarity and comprehensibility of information presented in the messages. Examples of the items include, “The message says watch for updates;” “The message says to avoid all windows;” and “The message says Police are on the scene.” Participants used a 2-point no/yes scale to indicate their answers.

Feelings of trust, control, self-efficacy, and perceptions of risk. Eighteen items asked participants to indicate their reactions if they received the message during an emergency. Examples include, "Would you think the threat is serious?”, “Would you feel like you have control in this situation?”, and “How much emotional distress do you think you would feel?” Participants used a 5-point scale (1 = not at all to 5 = very much) to indicate their answers.

Actions in response to the message if participants were at the location of the incident. Sixteen items asked about actions participants predicted they would take if they were in the dangerous location when they received the message. Examples include, “I would call the police”, “I would avoid all windows”, and “I would not know what to do.” Participants used a 5-point scale (1 = not at all to 5 = very much) to indicate their answers.

Actions in response to the message if participants were not at the location of the incident. The same 16 items from the previous section asked about actions participants predicted they would take if they were not at scene of the incident when they received the message.

Cell phone use and familiarity with the University Alert System. Five items asked participants if they had a cell phone, if their cell phone receives text messages when on campus, if they had registered their cell phone number with the University Alert System, if they take their phone to class and leave it on during class, and if their phone alerts them when a text message is received. Participants used a 2-point no/yes scale to indicate their answers.

E-mail use and computer access on campus. Five items asked participants to estimate what percentage of buildings on campus their phone worked in, how many hours a day they are on a computer, how often they check their e-mail, how often they visit the University’s website, and if they bring a laptop to class. Participants also were asked to anticipate how often they would check the University website for updates if they received a text or e-mail about an ongoing active shooter situation. Participants wrote in a number to answer each question.

Procedure

Participants completed the survey in their classes. All responses were anonymous and confidential. It took approximately 15 minutes to complete the survey. Participants were debriefed and any questions were answered. The project was approved by the Western Washington University Human Participants Review Committee.

Results

Access to Cell Phones and E-mail on Campus

Almost all participants had a cell phone (99%), were able to receive text messages (99%), were registered with the Western Washington University alert system (65%), take their cell phone to class (98.4%), leave their cell phone on during class (88%), and set their cell phone to alert them when they receive a text message (88%). On average, participants estimated they had cell phone service in most campus buildings (77%, SD = 17.27), indicated they spend 3.3 (SD = 3.1) hours per school day on a computer, check their e-mail 3 (SD = 2.5) times per school day, and visit the university website 3.15 (SD = 6.9) times per school day. About one-tenth (11%) used a laptop in class. Participants reported they would check the university website for updates every 23 (SD = 49) minutes if they received the alert via text message and every 23 (SD = 40.3) minutes if they received the alert via e-mail.

Text and E-mail Message Comprehensibility

Text message comprehension. Table 1 shows that for the text messages, the vast majority of participants understood the degree of threat, the actions to be taken, and that they should not reply to the text message. However, on average, only about two-thirds (63%) correctly understood that “INFO: emergency.wwu.edu” indicated updates would be presented on the website. Thus, we suggest to use “UPDATES” rather than “INFO” to clearly convey the intent.

E-mail message comprehension. Table 1 shows that for the all e-mail messages, the vast majority (96% or greater) understood each component of the message. These e-mail messages also specifically indicated to check a website for updates. However, the “all clear” message appeared to convey two contradictory statements. One component indicated the campus is safe but another component indicated to stay away from the location of the incident. For this message, about two-thirds (67%) believed the campus was safe. Table 2 presents the actions

participants indicated they would take even though these actions were not indicated in either the text or e-mail messages.

Table 1. Percentage who Correctly Understood Content of Text and E-mail Warning Messages (N = 264).

Situation Message Content Percent

Status Correct

__________________________________________________________________

Text Messages

Serious WWU ALERT. Serious threat at Smith Hall. 98%

Threat Watch 4 updates. Info: emergency.wwu.edu Dont reply

Serious WWU ALERT. Serious treat. Leave Smith Hall 99%

Threat: now. Stay away. Watch 4 updates.

Leave Area Info: emergency.wwu.edu Dont reply

Serious WWU ALERT. Serious threat at Smith Hall. 98%

Threat: Stay Stay away. If at location go 2 room/barricade

in Room door. Info: emergency.wwu.edu Dont reply

Active WWU ALERT. Shooter at Smith Hall. If on 96%

Shooter campus go 2 room/barricade door. Dont come

on Campus 2 campus. Info: emergency.wwu.edu Dont reply

Active WWU ALERT. Shooter contained at Smith Hall. 94%

Shooter If on campus stay in place. Dont come 2 campus.

Update Info: emergency.wwu.edu Dont reply

All WWU ALERT. Police believe campus now safe. 94%

Clear Stay away from Smith Hall. Classes cancelled. Info: emergency.wwu.edu Dont reply

Note. Only two-thirds (63%) of participants correctly interpreted “INFO: emergency.wwu.edu” as indicating updates would be presented on this website. We recommend replacing the word INFO with UPDATES to clarify the intent. Note: Table presents fictitious building name.

E-mail Messages

Serious There is a serious threat currently at Smith Hall. 96%

Threat Police are evaluating the situation. Watch for updates. WWU will provide updates via: your e-mail, a text

message to your cell phone (if you previously subscribed), websites. First, go to emergency.wwu.edu, then go to the WWU homepage, www.wwu.edu

Serious There is a serious threat currently at Smith Hall. Police 99%

Threat: are on the scene. Stay away from that location. If you

Leave are in that location, leave immediately. Watch for updates.

Area WWU will provide updates via: your e-mail, a text

message to your cell phone (if you previously subscribed), websites. First, go to emergency.wwu.edu, then go to the WWU homepage, www.wwu.edu

Serious There is a serious threat currently at Smith Hall. Police 96%

Threat: Stay are on the scene. If you are in that location, stay in or

in Room find a room. Lock or barricade the door. Avoid all windows. If you are not at that location, stay away from that location. Watch for updates. WWU will provide updates via: your e-mail, a text message to your cell phone (if you previously subscribed), websites. First, go to emergency.wwu.edu, then go to the WWU

homepage, www.wwu.edu

Active There is a shooter on campus at Smith Hall. You are at 99%

Shooter serious risk. Police are on the scene. If you are on

on Campus campus, stay in or find a room. Lock or barricade the door. Avoid all windows. Classes are cancelled until further notice. WWU will provide updates via: your e-mail, a text message to your cell phone (if you previously

subscribed), websites. First, go to emergency.wwu.edu, then go to the WWU homepage, www.wwu.edu

Active The shooter at Smith Hall has been contained. Stay away 97%

Shooter from that location. Police are on the scene. If you are on

Update campus, please remain where you are until the situation is resolved. If you are off campus, do not come to campus. Classes are cancelled until further notice. WWU will

provide updates via: your e-mail, a text message to your cell phone (if you previously subscribed), websites. First, go to emergency.wwu.edu, then go to the WWU homepage, www.wwu.edu

All Today, there was a situation involving a shooter at WWU. 98%

Clear Police have resolved this situation and are investigating. Police believe the campus is now safe. Stay away from Smith Hall as police investigate. If you are off campus, do not come to campus. Classes remain cancelled until further notice. WWU will provide updates via: your e-mail, a text message to your cell phone (if you previously

subscribed), websites. First, go to emergency.wwu.edu, then go to the WWU homepage, www.wwu.edu

Intent to Comply with Message Instructions

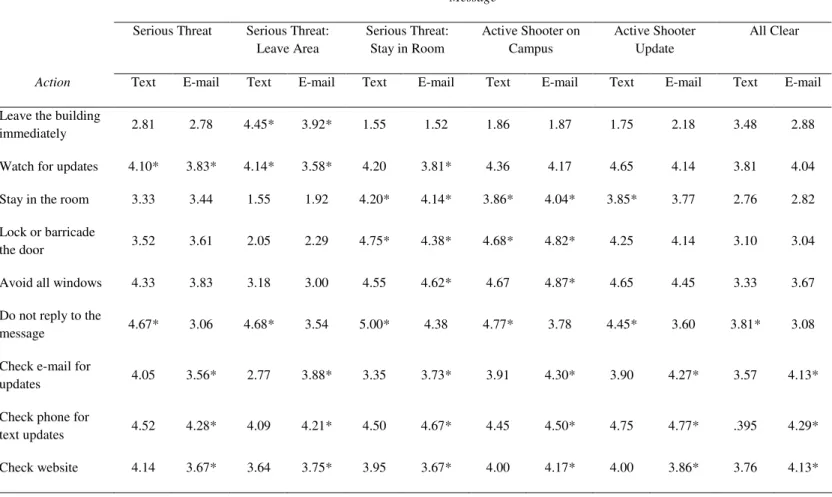

Table 3 shows that participants receiving the text message indicated they would take all of the actions indicated in the message, as well as additional protective actions that were not indicated in the text message, such as checking e-mail and text messages for updates. Table 3 also shows that participants receiving the e-message indicated they would take all of the actions indicated in the e-messages, as well as additional protective actions that were not indicated in the e-mail message, such as avoiding windows, locking or barricading the door, and not replying to the message.

Factor Analysis on Actions in Response to the Message Items

A principle component factor analysis with varimax rotation was performed on the 16 items asking about actions participants might take in response to the message. Four factors with eigenvalues greater than one and with factor loadings greater than .60 emerged.

Factor one assessed trust and quality of the message (α = .79) and

included three items: “Do the instructions in the message seem appropriate to you?”, “Would you trust those responsible for sending the message?”, and “Does the message provide enough information about the situation for you to make a good decision about what to do?”

Factor two assessed risk perception and distress (α = .76) and included

three items: “Would you feel at risk if you were in the location specified in the message?”, “Would you think the threat is serious?”, and “How much emotional distress would you feel?”

Table 2. Intent to Take Actions that Were Not Described in the Message if Individual was at Incident Location (N = 264). Note: Means presented. Rating scale: 1 = not at all likely to take this action to 5 = very likely to take this action.

Message

Serious Threat Serious Threat:

Leave Area Serious Threat: Stay in Room Active Shooter on Campus Active Shooter Update All Clear

Action Text E-mail Text E-mail Text E-mail Text E-mail Text E-mail Text E-mail

Ask nearest person

what to do 2.38 2.72 2.68 2.63 2.35 2.38 3.00 2.48 2.50 2.86 2.57 3.08

Follow what other

people do 2.62 3.06 2.82 2.83 2.60 3.00 3.23 2.70 2.95 2.91 2.76 2.96

Hide under the

nearest table/desk 2.62 2.56 1.59 1.88 3.15 3.19 3.10 3.57 3.85 3.27 2.33 2.04

Not know what to

do 2.90 3.11 2.32 2.21 2.00 1.81 2.14 2.43 2.60 2.32 2.29 2.54

Call a friend or

family member 2.81 3.17 2.36 2.96 2.85 3.05 3.36 3.17 3.15 3.14 2.90 3.21

Call the Police 2.76 3.06 2.14 2.42 2.50 2.95 3.5 2.61 3.10 2.86 2.95 2.79

Table 3. Intent to Take Actions that Were and Were Not Described in Message if Individual was at Incident Location (N = 264). Note: Means presented. * = Message indicates take this action; No * = Message did not indicate the action. Rating scale: 1 = not at all likely to take this action to 5 = very likely to take this action.

Message

Serious Threat Serious Threat:

Leave Area Serious Threat: Stay in Room Active Shooter on Campus Active Shooter Update All Clear

Action Text E-mail Text E-mail Text E-mail Text E-mail Text E-mail Text E-mail

Leave the building

immediately 2.81 2.78 4.45* 3.92* 1.55 1.52 1.86 1.87 1.75 2.18 3.48 2.88

Watch for updates 4.10* 3.83* 4.14* 3.58* 4.20 3.81* 4.36 4.17 4.65 4.14 3.81 4.04

Stay in the room 3.33 3.44 1.55 1.92 4.20* 4.14* 3.86* 4.04* 3.85* 3.77 2.76 2.82

Lock or barricade

the door 3.52 3.61 2.05 2.29 4.75* 4.38* 4.68* 4.82* 4.25 4.14 3.10 3.04

Avoid all windows 4.33 3.83 3.18 3.00 4.55 4.62* 4.67 4.87* 4.65 4.45 3.33 3.67

Do not reply to the

message 4.67* 3.06 4.68* 3.54 5.00* 4.38 4.77* 3.78 4.45* 3.60 3.81* 3.08

Check e-mail for

updates 4.05 3.56* 2.77 3.88* 3.35 3.73* 3.91 4.30* 3.90 4.27* 3.57 4.13*

Check phone for

text updates 4.52 4.28* 4.09 4.21* 4.50 4.67* 4.45 4.50* 4.75 4.77* .395 4.29*

Factor three assessed perceived control, self-efficacy, and ability to handle the situation (α = .76) and included three items: “How confident would you be in

your ability to handle this situation?”, “Would you know what to do in this situation?”, and “Would you feel like you have control in this situation?”

Factor four assessed external locus of control (α = .32) and included three items:

“Do you believe it is not always good to plan too far ahead because many things happen because of good or bad fortune?”, “Do you think it is likely that you may receive a message like this one this year?”, and “Do you believe that when you get what you want it is usually because you are lucky?” The first three factors had adequate reliability and the fourth factor had poor reliability.

Analysis of Variance Tests

Two-way between-subjects (Delivery Type x Message Content) ANOVA tests assessed the quality of the each message, perceptions of threat and distress, and perceived ability to control or handle the situation, and Tukey post-hoc comparisons were performed when appropriate.

Trust and quality of message. There was a main effect of message content on message reliability, F (5, 248) = 8.96, p < .001, MSE = .736, eta2= .153. The “active shooter on campus” message resulted in the highest level of trust and quality, followed by “active shooter update,” “serious threat-stay in room,” “serious threat-leave,” “all clear,” and “serious threat.”

Threat/distress. There was a main effect of message content on risk perception and distress, F (5, 248) = 8.96, p < .001, MSE = .495, eta2= .124. The “active shooter on campus” message was associated with more risk perception and distress than the “serious threat” message. The “serious threat-stay in room”, the “active shooter on campus”, and the “active shooter update” message were associated with more risk perception and distress than the “all clear” message.

Control/handle situation. There was a main effect of message content on perceived control and ability to handle the situation, F (5, 248) = 3.27, p = .007,

MSE = .718, eta2= .062. Participants felt as though they had more control and were better able to handle the situation when presented with the “serious threat-stay in room” message, the “active shooter update” message, and the “all clear” message rather than the “serious threat” message.

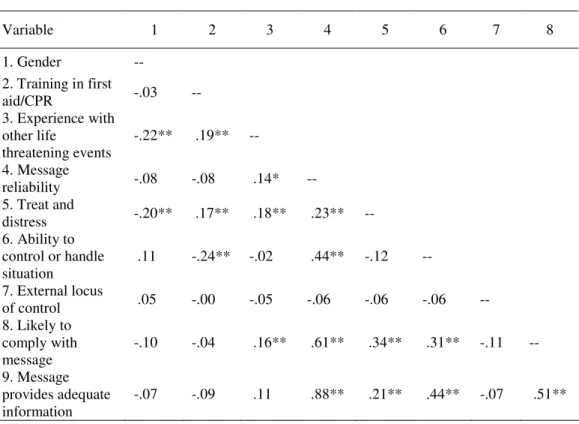

Correlations

Table 4 shows that message reliability and trust were strongly associated with believing that the message provided enough information, being likely to comply

with the message, and feeling able to control or handle the situation. Likelihood to comply with the message was strongly associated with feeling that the message provided enough information. Feeling able to handle or control the situation was associated with being likely to comply and feeling like the message provided enough information. Having training in First Aid/CPR was weakly associated with perceiving a threat and feeling distressed, and negatively associated with their ability to handle or control the situation.

Table 4. Correlations among Gender, Training, Experience, Message Reliability, Threat Perception, Ability to Control Situation, External Locus of Control, Likelihood to Comply, and Message Information (N = 264).

Variable 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 1. Gender -- 2. Training in first aid/CPR -.03 -- 3. Experience with other life threatening events -.22** .19** -- 4. Message reliability -.08 -.08 .14* -- 5. Treat and distress -.20** .17** .18** .23** -- 6. Ability to control or handle situation .11 -.24** -.02 .44** -.12 -- 7. External locus of control .05 -.00 -.05 -.06 -.06 -.06 -- 8. Likely to comply with message -.10 -.04 .16** .61** .34** .31** -.11 -- 9. Message provides adequate information -.07 -.09 .11 .88** .21** .44** -.07 .51** Note: * = p < .05; ** = p < .01. Discussion

Almost all participants (95%) understood the text and e-mail messages and indicated they would comply with the recommended self-protective actions. A small percent indicated they might take additional precautionary actions that were not discussed in the message, such as hiding under a desk, calling a friend or

family member, and following the actions of other people. Participants who received the “serious threat” and “active shooter update” messages also indicated they would lock or barricade the door and avoid windows, even though these actions were not discussed in the messages.

Message reliability and trust were strongly associated with likelihood to comply with the message and feeling able to control or handle the situation. Likelihood to comply with the message was strongly associated with feeling that the message provided enough information. This is consistent with prior research. Trusting the message source increases a person’s compliance with instructions (Mileti & Peek, 2002). Effective messages (a) describe the situation clearly so that people understand the danger, (b) are issued by a credible source, (c) include specific information indicating the location and time of the event, and (d) state protective actions (Mileti & O’Brien, 1992; Mileti & Peek, 2000). The present results indicate the messages effectively addressed each of these components in the context of an active shooter situation.

Almost all (99%) students reported having a cell phone, that they leave it on during class, and that the phone alerts them when a text message is received (88%). Although most students indicated that they check their e-mail several times throughout the day, only about one-tenth bring a laptop to class. These findings suggest text messaging may be one of the most important mediums to immediately notify students of an incident (cf. Junco & Cole-Avent, 2008). In order to receive a text message, however, students must register their cell phone number with the college or university. About two-thirds of students in this study reported having registered with the Western Washington University alert system database, and the University states that 82% of all students have registered with the system. Because the effectiveness of the warning system depends upon the percent of persons having preregistered with the system, institutions should take special effort to register students, faculty, and staff. Effectiveness also depends upon cell phone coverage and reception. Most cellular phone companies state that they cannot guarantee reception within buildings, and it is likely that cell phone service may be sporadic or unavailable in certain buildings. There also are concerns whether the cell phone company can process and send thousands of text messages in a timely manner.

Text messages are limited to 160 characters or less and this limitation means that careful thought is needed when crafting a clear, concise, and complete message that will result in the desired response from the recipients. The Western Washington University Emergency Management Committee developed the templates presented in this study to be used during an event, with the understanding that they can be modified if needed. Having the template and assessing the effectiveness of each message allows the Committee to revise components of messages that were not completely clear, such as how to get

additional information. Having templates will significantly reduce the amount of time needed to construct an effective message during a crisis situation. Higher education institutions also can prepare text and e-mail templates for other types of mass emergencies or disasters, including earthquakes, tornadoes, and hurricanes. Using the methodology presented in this study will provide critical feedback to aid Committees in assessing the clarity and effectiveness of the messages and in subsequent message revisions. One limitation of this approach is that participants received the message on paper during a study rather than on their cell phone or email, and actual behavior during an emergency might differ.

Future research should examine how people of various age groups and positions across the university respond to the messages, and might deliver the messages during a simulated emergency in order to study in more detail compliance with the message. Effective text and e-mail messages may minimize loss of life and injury by keeping the campus community informed as an incident develops.

References

Indiana University Police Department (2009). Responding to an active shooter. http://www.indiana.edu/~iupd/active_shooter.htm

Jeanne Clery Disclosure of Campus Security Policy and Campus Crime Statistics Act (2008), Public Law 110-315; U.S. Department of Education, http://www2.ed.gov/policy/highered/leg/hea08/index.html

Junco, R. and Cole-Avent, G. A., (2008). An introduction to technologies commonly used by college students. New Directions for Student Services, 124, 3-17.

Lindell, M. K. and Perry, R. W. (2004). Communicating Environmental Risk in Multiethnic Communities. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc. Mileti, D., & O'Brien, P. (1992). Warnings during disaster: Normalizing

communicated risk.” Social Problems, 39, 40-56.

Mileti, D. S., & Peek, L. (2000) The social psychology of public response to warning of a nuclear power plant accident. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 75, 181-194.

Peek, L. A., & Mileti, D. S. (2002). The history and future of disaster research. In R. B. Bechtel & A. Churchman (Eds.), Handbook of Environmental Psychology (pp. 511-522). NY: John Wiley and Sons.

Plummer, D., & Johnson, W. (2008). Planning for Battle. American School and University, 80(7), 30-33.

Riad, J. K., Norris, F. H., & Ruback, R. B. (1999). Predicting evacuation in two major disasters: Risk perception, social influence, and access to resources.

Sattler, D. N., Kaiser, C. F., & Hittner, J. B. (2000). Disaster preparedness: Relationships among prior experience, personal characteristics, and distress. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 30, 1396-1420.

Sattler, D. N., & Marshall, A. (2002). Hurricane preparedness: Improving television hurricane watch and warning graphics. International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters,20, 41-49.

Sjöberg, L. (2000). Factors in risk perception. Risk Analysis, 20, 1-11.

Smith-Jackson, T. L. (2006). Receiver characteristics. In M. S. Wogalter (Ed.), Handbook of warnings (pp. 335-343). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. U.S. Department of Education (2008). Campus Security. Retrieved May 6, 2009,

from U.S. Department of Education Web site: http://www.ed.gov/admins/lead/safety/campus.html.