EXPERIENCE & REASON

Brugada Syndrome Masquerading as Febrile Seizures

Jonathan Robert Skinner, MB, ChB, FRACP, FRCPCH, MDa,b, Seo-Kyung Chung, BScb,c, Carey-Anne Nel, BSc, MSc(Med)b,d, Andrew Neil Shelling, BPhEd, BSc, PhDb,d, Jackie Robyn Crawford, NZCSa,b, Neil McKenzie, MB, ChB, FRACPe,

Ralph Pinnock, MB, ChB, DCH(SA), MHSc, FRACPf, John Kerswell French, BMedSc, MB, ChB, MSc, PhDb,g, Mark Ian Rees, BSc, PhDb,h

aGreenlane Paediatric and Congenital Cardiac Services andfDepartment of Paediatrics, Starship Children’s Hospital, Grafton, Auckland, New Zealand;bCardiac Inherited

Disease Group, Auckland City Hospital, Grafton, Auckland, New Zealand; Departments ofcMolecular Medicine anddObstetrics and Gynaecology, Faculty of Medical and

Health Sciences, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand;eDepartment of Paediatrics, Christchurch Public Hospital, Christchurch, New Zealand;gDepartment of

Cardiology, Liverpool Hospital, Liverpool, New South Wales, Australia;hMolecular Neuroscience Group, School of Medicine, University of Wales Swansea, Swansea,

United Kingdom

The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

ABSTRACT

Fever can precipitate ventricular tachycardia in adults with Brugada syndrome, but such a link has not been reported in children. A 21-month-old white girl presented repeatedly with decreased conscious level and seizures during fever. During a typical episode, rapid ventricular tachycardia was documented. The resting 12-lead electrocardiogram revealed a Brugada electrocardiogram signature. Resting electrocardiograms of the asymptomatic brother and mother were normal, but fever in the mother and pharmacologic stress with ajmaline in the brother revealed Brugada

electrocardiogram features. Genetic testing revealed anSCN5Amutation in the affected family members.

F

EBRILE SEIZURES ARE a common, benign phenome-non that occur in children between the ages of 6 months and 6 years. Death from febrile seizures has notbeen described.1The seizures are typically brief and

trig-gered by a rapid rise in temperature, usually caused by a viral illness. The prognosis is good, although a minority

of children develop epilepsy without fever in later life.2,3

However, death during and after “epileptic” seizures is not infrequent and has its own pseudonym of SUDEP

(sudden unexpected death in epilepsy).4

Sudden death syndromes are attributed partly to car-diac arrhythmia syndromes, in particular long QT

syn-drome and cardiomyopathic disorders.5,6 In Brugada

syndrome, sudden unexpected death can occur as a re-sult of ventricular fibrillation or rapid ventricular

tachy-cardia.7 The 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) typically

reveals an elevated ST segment in the anterior precordial leads with a right bundle branch block-like appearance. Approximately 10% to 30% of affected Brugada syn-drome cases have been linked to mutations within

SCN5A, a gene that codes for the ␣subunit of the

volt-age-gated sodium channel Nav1.5 and is also associated

with long QT syndrome type 3.8–11

In this report we present a child with a series of seizures associated with fever. The presentation initially led to an erroneous diagnosis of benign febrile seizures. However, rapid ventricular tachycardia was found with a resting ECG compatible with Brugada syndrome. A

mutation withinSCN5A, inherited from the mother, was

discovered in the child. Such a presentation has not been described in children; therefore, features of the investi-gation, diagnosis, and treatment are discussed here.

CASE REPORT

A 21-month-old previously healthy white girl presented to the emergency department during the night after a third episode of seizure with a high fever. The patient had been seen at the same hospital 3 months earlier (during the second attack) with a high fever (38.5°C) that was diagnosed as a febrile seizure. On all 3 occa-sions, occurring some months apart, she woke the par-ents with a cry of distress; they found her in her cot with the sheet covering her while she was jerking rhythmi-cally. She was “either asleep or unconscious.” She felt

Key Words:fever, seizures, ventricular tachycardia, cardiac channelopathies, Brugada syndrome

Abbreviations:ECG, electrocardiogram;SCN5A, gene encoding for sodium channel, voltage-gated, type V, alpha; SCN5A/Nav1.5, gene product/protein sodium channel,

voltage-gated, type V, alpha; dHPLC, denaturing high-pressure liquid chromatography www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2006-2628

doi:10.1542/peds.2006-2628

Accepted for publication Nov 1, 2006

Address correspondence to Jonathan Robert Skinner, MB, ChB, FRACP, FRCPCH, MD, Green Lane Paediatric and Congenital Cardiac Services, Starship Children’s Hospital, Park Road, 1141 Auckland, New Zealand. E-mail: jskinner@adhb.govt.nz

very hot, and after uncovering her, the jerking, which affected both arms, rapidly ceased. After this she was limp, very pale, and unresponsive, but she was breath-ing. With efforts to cool her, her conscious level in-creased over a few minutes. During a third episode, described by the parents as identical to the previous 2 but lasting longer despite cooling, she presented to the emergency department.

She was pale and unwell; her temperature was 38.0°C and pulse rate was 200 beats per minute, with a gallop rhythm and poor peripheral perfusion. She was limp, distressed, and whimpering, not vocalizing clearly, and did not recognize her parents as being distinct from nursing staff.

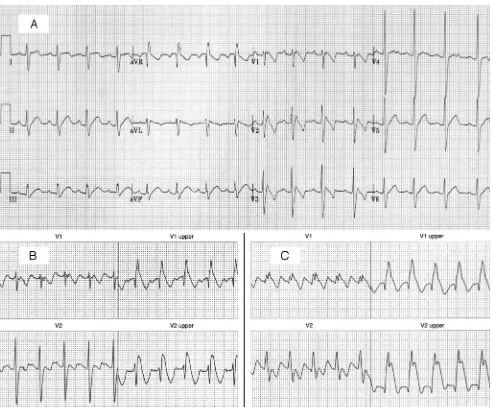

There were clinical signs of an upper respiratory tract infection. The precordium was noted to be hyperactive. The 12-lead ECG showed a rapid, broad-complex tachy-cardia (Fig 1). The patient received 3 bolus doses of

adenosine (50, 100, and 250g/kg), to no effect. After a

cough, her sinus rhythm returned (Fig 2A). Immediately her color improved and she sat up, talked to her parents, and started naming objects in the room. She was started on oral sotalol 2 mg/kg twice daily. The fever took some days to settle and was managed with paracetomol; no additional seizures or tachycardias recurred. Brugada syndrome was suspected from the resting ECG (Fig 2A), and she was transferred to a pediatric cardiology unit for additional investigation.

The working diagnosis, therefore, was that she had had reduced conscious level and seizure triggered by low

cerebral perfusion as a result of a fever-triggered ven-tricular tachycardia.

The family history revealed no incidences of seizure, sudden death, or syncope, and resting ECGs on the brother and both parents were normal. An echocardio-gram and cardiac MRI scan were normal. An intrave-nous challenge with ajmaline, a short-acting

sodium-channel– blocking agent,12 was performed. The result

was strongly positive, with very marked exaggeration of the precordial ST segment elevation at low doses (0.2 mg/kg) (Fig 2B). The family was provided with an au-tomatic external defibrillator for home use, given open access to the local hospital, and advised to treat fevers aggressively with paracetomol and tepid sponging. The sotalol was continued because of its apparent early ther-apeutic benefit, with no recurrence of seizures or ven-tricular tachycardia with subsequent fevers over the first few days. Before planned ajmaline tests on the parents, both of whom had normal resting ECGs, the mother had some palpitations during an attack of influenza. At the time of high fever, her ECG revealed typical Brugada features (Fig 3). An invasive electrophysiology study did not induce ventricular arrhythmias. The brother also had a normal resting ECG, but his ajmaline test was also positive, although the ECG changes occurred at higher doses than those of his sister (0.8 mg/kg).

GENETIC ANALYSIS OFSCN5A

After obtaining informed consent for genetic testing, blood samples were taken from the presenting child for

FIGURE 1

mutation analysis ofSCN5A. The genomic DNA was used for polymerase chain reaction– based assays covering the coding and flanking intronic regions of the gene, and the polymerase chain reaction products were screened for heterozygous profiles by using conventional denaturing high-pressure liquid chromatography (dHPLC) technol-ogy (Transgenomic, Omaha, NE). The output profiles from the dHPLC were scrutinized for abnormal profiles indicating the presence of heterogeneous DNA mis-matching. Abnormal dHPLC profiles were sequenced in both directions (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), and sequence changes were verified by restriction frag-ment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis when avail-able. RFLP studies of mutation frequencies were con-ducted on 2% molecular screening agarose gels (Roche,

Indianapolis, IN) using 150 random normal-control cases to evaluate candidate pathogenic mutations within the general population.

RESULTS

Genetic Testing

The dHPLC screening revealed several abnormal profiles

that required sequencing. Sequencing ofSCN5Aexon 24

demonstrated a novel, heterozygous 1-base pair (bp) insertion mutation (InsG) in position nt4392– 4396 of theSCN5Acoding sequence (Fig 4). This mutation was also found in the mother and brother but not in the father. In the absence of differentiating restriction-en-zyme– digest profiles, the mutation was excluded from FIGURE 2

300 normal-control chromosomes by dHPLC profiling (not shown). No other mutations were found.

Clinical Outcome

The girl was continued on sotalol, and an advisory ex-ternal defibrillator was provided for the family. Fevers were managed with paracetomol. Three and a half years later, the girl remains well, having had many febrile episodes and no more seizures or clinically evident tachycardias. Her resting ECG remains abnormal. No intervention was given for the mother or brother, who both remain well. Dislocation of the genetic maternal family has thwarted efforts to screen more distant family relatives for Brugada syndrome.

DISCUSSION

Brugada syndrome most commonly causes sudden

un-expected death in young Asian men during sleep.11It is

inherited in an autosomal dominant manner with vari-able clinical expression, and females are significantly less

likely to die suddenly.13We have not been able to find a

single case report of death after a febrile seizure, which suggests that Brugada syndrome, with a fever-triggered ventricular arrhythmia causing decreased conscious level during fever, must be a very rare mimic of this usually benign condition. Nevertheless, ECGs are not typically a routine part of clinical assessment after a seizure associated with fever, and the condition may be more frequent than suspected. Furthermore, there may be a reluctance by forensic pathologists to attribute deaths during or after seizures to febrile seizure because of their benign nature by definition. Deaths with sei-zures secondary to long QT syndrome have been

erro-neously ascribed to epilepsy in the past.14

The Brugada syndrome mutations inSCN5A cause a

dominant negative effect or loss of function in the so-dium current, which is a determinant of the phase 0 and

phase 1 segments of the cardiac action potential.15

Car-riers of Brugada syndrome can have a normal resting ECG, but recent observations in adults have demon-strated that classical Brugada ECG features, even ven-tricular tachycardia and death, can be precipitated by

fever.16–20No such link to fever has been shown in

chil-dren, yet 3 independent cases of infants with ventricular fibrillation or ventricular tachycardia have been reported

recently in association with mutations inSCN5A: 2

ciated with long QT syndrome type 3 and one in

asso-ciation with Brugada syndrome.21–23

In our patient, the 1-bp insertion causes the reading

frame ofSCN5Ato be disrupted; a premature stop codon

(at position 1483 of SCN5A[1483X]) results in a

trun-cated SCN5A polypeptide. Other suchSCN5Amutations

that generate a premature termination codon are asso-FIGURE 3

V1–V3 extracted from a 12-lead ECG from the mother of our patient during an attack of influenza. The Brugada-type pattern is most obvious in lead V2; the arrow indicates the pathologic ST segment.

FIGURE 4

ciated with distinct clinical phenotypes; 4196delA (V1397X) is associated with Brugada syndrome, and 5280delG(1768X) is associated with conduction

dis-ease.24,25 Electrophysiological studies of both of these

mutants failed to express any sodium currents; thus, it is

likely that the SCN5Amutation in the present case will

also fail to produce sodium currents. Although cellular electrophysiology has not been performed, the ECG changes in the family are so characteristic that the Bru-gada phenotype is not in doubt.

This case is the first reported incident in which the febrile-onset phenomenon has occurred in a young child and is made more remarkable by the fact that she is both female and white. Overheating is a known risk factor for

sudden infant death syndrome and the SCN5A gene is

the most common of any to be linked to sudden infant

death.26It is tempting to speculate that this correlation

may be attributable in part to heat-triggered ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation in such genetically vulnerable infants.

Our patient and her mother have a fever-dependent expression of the phenotype. In the case of our patient, the ventricular tachycardia may have happened during a critical developmental window, as reflected by the ab-sence of ventricular tachycardia or seizures during sub-sequent febrile illness. A family with young-age–specific sudden death was described recently with a Brugada

SCN5Amutation.27It is also possible that sotalol therapy

or liberal use of antipyretics have stopped a recurrence. No medications (including sotalol), with the emerging

possible exception of quinidine,28have proven

therapeu-tic benefit for Brugada syndrome. Although pure

blockers, in large doses, can unmask Brugada ECG

changes and may be arrhythmogenic,29 we have been

reluctant to discontinue sotalol (which has both

-block-ing and repolarization-prolong-block-ing [Vaughan-Williams type III] properties) because of the apparent beneficial effect on arrhythmia prevention during our patient’s

many subsequent high fevers over⬎3 years.

Molecular defects in Nav1 channels have been

re-ported in association with temperature-sensitive disor-ders such as generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures plus and heat-induced myotonia and cold-induced

pa-ralysis in congenital paramyotonia.30–32 Furthermore, a

patient with a febrile illness and cardiac conduction dis-ease who experienced a syncope was reported to be a

carrier for a SCN5A G514C mutation.33 A 42-year-old

man who presented with fever-induced ventricular

fi-brillation carried a missense SCN5Amutation (F1344S);

cellular electrophysiological testing showed a

tempera-ture-sensitive sodium current.34 SCN9A(Na

v1.7)

muta-tions have also been reported in primary erythermalgia, a rare disorder that is characterized by intermittent burning pain with redness and heat in the extremi-ties.35,36

CONCLUSIONS

Fever can trigger ventricular tachycardia in young chil-dren with previously unrecognized Brugada syndrome, and the low-output state can trigger a seizure, the pre-sentation thus mimicking febrile seizures.

This case serves as a reminder that occult cardiac channelopathies should be borne in mind in the inves-tigation of childhood seizures with or without fever. However, we would not yet advise that all children who have a seizure or reduced conscious level during fever should have an ECG. It would be prudent to order an ECG if there are clinical features suggesting a cardiac arrhythmia (tachycardia out of proportion to the fever, weak peripheral pulses, hyperactive precordium, and marked pallor) or a family history suggesting Brugada syndrome, such as young sudden death, particularly in males at night.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The molecular genetics work was enabled by grants from Cure Kids, the Lion Foundation, the Greenlane Research and Education Fund, and the John Neutze Fund.

We thank Dr Iain Melton for providing information and ECGs on the parents, and we thank the parents of the child concerned, who enthusiastically supported the publication of this report.

REFERENCES

1. Waruiru C, Appleton R. Febrile seizures: an update.Arch Dis Child.2004;89:751–756

2. Nelson KB, Ellenberg JH. Prognosis in children with febrile seizures.Pediatrics.1978;61:720 –727

3. Verity CM, Golding J. Risk of epilepsy after febrile convulsions: a national cohort study [published correction appears inBMJ. 1992;304:147].BMJ.1991;303:1373–1376

4. Gordon N. Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy.Dev Med Child Neurol.2001;43:354 –357

5. Priori SG, Napolitano C. Genetics of cardiac arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death.Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1015:96 –110 6. Dumaine R, Antzelevitch C. Molecular mechanisms underlying

the long QT syndrome.Curr Opin Cardiol.2002;17:36 – 42 7. Brugada J, Boersma L, Kirchhof C, et al. Double-wave reentry

as a mechanism of acceleration of ventricular tachycardia. Cir-culation.1990;81:1633–1643

8. Wang Q, Shen J, Splawski I, et al.SCN5Amutations associated with an inherited cardiac arrhythmia, long QT syndrome.Cell.

1995;80:805– 811

9. Wilde AA, Remme CA, Derksen R, Wever EF, Hauer RN. Brugada syndrome.Eur Heart J.2002;23:675– 676

10. Napolitano C, Rivolta I, Priori SG. Cardiac sodium channel diseases.Clin Chem Lab Med.2003;41:439 – 444

11. Vatta M, Dumaine R, Varghese G, et al. Genetic and biophys-ical basis of sudden unexplained nocturnal death syndrome (SUNDS), a disease allelic to Brugada syndrome. Hum Mol Genet.2002;11:337–345

12. Wolpert C, Echternach C, Veltmann C, et al. Intravenous drug challenge using flecainide and ajmaline in patients with Bru-gada syndrome.Heart Rhythm.2005;2:254 –260

14. Skinner JR, Chong B, Fawkner M, Webster DR, Hegde M. Use of the newborn screening card to define cause of death in a 12-year-old diagnosed with epilepsy. J Paediatr Child Health.

2004;40:651– 653

15. Antzelevitch C, Brugada P, Brugada J, et al. Brugada syn-drome: a decade of progress.Circ Res.2002;91:1114 –1118 16. Porres JM, Brugada J, Urbistondo V, Garcia F, Reviejo K,

Marco P. Fever unmasking the Brugada syndrome.Pacing Clin Electrophysiol.2002;25:1646 –1648

17. Mok NS, Priori SG, Napolitano C, Chan NY, Chahine M, Ba-roudi G. A newly characterizedSCN5A mutation underlying Brugada syndrome unmasked by hyperthermia.J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol.2003;14:407– 411

18. Smith J, Hannah A, Birnie DH. Effect of temperature on the Brugada ECG.Heart.2003;89:272

19. Keller DI, Rougier JS, Kucera JP, et al. Brugada syndrome and fever: genetic and molecular characterization of patients car-ryingSCN5Amutations.Cardiovasc Res.2005;67:510 –519 20. Dinckal MH, Davutoglu V, Akdemir I, Soydinc S, Kirilmaz A,

Aksoy M. Incessant monomorphic ventricular tachycardia dur-ing febrile illness in a patient with Brugada syndrome: fatal electrical storm.Europace.2003;5:257–261

21. Schwartz PJ, Priori SG, Dumaine R, et al. A molecular link between the sudden infant death syndrome and the long-QT syndrome.N Engl J Med.2000;343:262–267

22. Wedekind H, Smits JP, Schulze-Bahr E, et al. De novo muta-tion in theSCN5Agene associated with early onset of sudden infant death.Circulation.2001;104:1158 –1164

23. Skinner JR, Chung SK, Montgomery D, et al. Near-miss SIDS due to Brugada syndrome.Arch Dis Child.2005;90:528 –529 24. Chen Q, Kirsch GE, Zhang D, et al. Genetic basis and molecular

mechanism for idiopathic ventricular fibrillation.Nature.1998; 392:293–296

25. Schott JJ, Alshinawi C, Kyndt F, et al. Cardiac conduction defects associate with mutations inSCN5A.Nat Genet.1999;23: 20 –21

26. Ackerman MJ, Siu BL, Sturner WQ, et al. Postmortem

molec-ular analysis of SCN5A defects in sudden infant death syn-drome.JAMA.2001;286:2264 –2269

27. Todd SJ, Campbell MJ, Roden DM, Kannankeril PJ. Novel BrugadaSCN5Amutation causing sudden death in children.

Heart Rhythm.2005;2:540 –543

28. Mizusawa Y, Sakurada H, Nishizaki M, Hiraoka M. Effects of low-dose quinidine on ventricular tachyarrhythmias in pa-tients with Brugada syndrome: low-dose quinidine therapy as an adjunctive treatment. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2006;47: 359 –364

29. Aouate P, Clerc J, Viard P, Seoud J. Propranolol intoxication revealing a Brugada syndrome.J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol.2005; 16:348 –351

30. Sugiura Y, Aoki T, Sugiyama Y, Hida C, Ogata M, Yamamoto T. Temperature-sensitive sodium channelopathy with heat-induced myotonia and cold-heat-induced paralysis.Neurology.2000; 54:2179 –2181

31. Abou-Khalil B, Ge Q, Desai R, et al. Partial and generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures plus and a novelSCN1Amutation.

Neurology.2001;57:2265–2272

32. Wallace RH, Scheffer IE, Barnett S, et al. Neuronal sodium-channel alpha1-subunit mutations in generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures plus.Am J Hum Genet.2001;68:859 – 865 33. Tan HL, Bink-Boelkens MT, Bezzina CR, et al. A

sodium-channel mutation causes isolated cardiac conduction disease.

Nature.2001;409:1043–1047

34. Keller DI, Huang H, Zhao J, et al. A novelSCN5Amutation,

F1344S, identified in a patient with Brugada syndrome and fever-induced ventricular fibrillation.Cardiovasc Res.2006;70: 521–529

35. Yang Y, Wang Y, Li S, et al. Mutations inSCN9A, encoding a sodium channel alpha subunit, in patients with primary er-ythermalgia.J Med Genet.2004;41:171–174

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2006-2628 originally published online April 9, 2007;

2007;119;e1206

Pediatrics

Mark Ian Rees

Jackie Robyn Crawford, Neil McKenzie, Ralph Pinnock, John Kerswell French and

Jonathan Robert Skinner, Seo-Kyung Chung, Carey-Anne Nel, Andrew Neil Shelling,

Brugada Syndrome Masquerading as Febrile Seizures

Services

Updated Information &

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/119/5/e1206

including high resolution figures, can be found at:

References

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/119/5/e1206#BIBL

This article cites 36 articles, 13 of which you can access for free at:

Subspecialty Collections

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/genetics_sub

Genetics

following collection(s):

This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

Permissions & Licensing

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml

in its entirety can be found online at:

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

Reprints

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2006-2628 originally published online April 9, 2007;

2007;119;e1206

Pediatrics

Mark Ian Rees

Jackie Robyn Crawford, Neil McKenzie, Ralph Pinnock, John Kerswell French and

Jonathan Robert Skinner, Seo-Kyung Chung, Carey-Anne Nel, Andrew Neil Shelling,

Brugada Syndrome Masquerading as Febrile Seizures

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/119/5/e1206

located on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 1073-0397.