ARTICLE

Survey of Pediatricians’ Opinions on Donation After

Cardiac Death: Are the Donors Dead?

Ari R. Joffe, MD, Natalie R. Anton, MD, Allan R. deCaen, MD

Department of Pediatrics, University of Alberta and Stollery Children’s Hospital, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada

The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

What’s Known on This Subject

DCD may increase organ donation and reduce transplant list mortality. When absent circulation is irreversible and, hence, constitutes death is controversial. Most DCD pro-grams pronounce death after 2 to 5 minutes of absent circulation.

What This Study Adds

Pediatricians are not comfortable that absent circulation for 5 minutes is the irreversible state of death, which suggests that additional debate about the concept of irreversibility as applied to DCD is needed.

ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVE.There has been debate in the ethics literature as to whether the

donation-after-cardiac-death donor is dead after 5 minutes of absent circulation. We set out to determine whether pediatricians consider the donation-after-cardiac-death donor as dead.

METHODS.A survey was mailed to all 147 pediatricians who are affiliated with the

university teaching children’s hospital. The survey had 4 pediatric patient scenarios in which a decision was made to donate organs after 5 minutes of absent circulation. Background information described the organ shortage, and the debate about the term “irreversibility” applied to death in donation after cardiac death. Descriptive statistics were used, with responses between groups compared by using the 2

statistic.

RESULTS.The response rate was 54% (80 of 147). In each scenario, when given a

patient described as dead with absent circulation for 5 minutes,ⱕ60% of respon-dents strongly agreed/agreed that the patient is definitely dead, ⱕ50% responded that the patient is in the state called “dead,” andⱕ56% strongly agreed/agreed that the physicians are being truthful when calling the patient dead. On at least 1 of the scenarios, 38 (48%) of 147 responded uncertain, disagree, or strongly disagree that the patient is definitely dead. Although the patients in the 4 scenarios were in the identical physiologic state, with absent circulation for 5 minutes, 12 (15%) of 80

respondents did not consistently consider the patients in the state called “dead” between scenarios. Fewer than 5% of respondents answered strongly agree/agree to allow donation after cardiac death while also answering disagree/ strongly disagree that the patient is definitely dead, suggesting little support to abandon the dead-donor rule.

CONCLUSIONS.Most pediatrician respondents were not confident that a donation-after-cardiac-death donor was dead.

This suggests that additional debate about the concept of irreversibility applied to donation after cardiac death is needed.Pediatrics2008;122:e967–e974

T

HERE ARE EFFORTSto increase the supply of organs as a result of increasing length of the transplant waiting lists and increasing mortality while on these waiting lists. One way to improve supply is to allow organ donation after cardiac death (DCD). After death is pronounced by using cardiocirculatory criteria, a consenting patient would allow his or her organs to be removed for transplantation.1,2Some surveys have suggested public and medical support forDCD.3–6Although at first DCD would seem ethically defensible, it has turned out to be surprisingly problematic.7

A central problem with all DCD practice is determining when death has occurred. Death is defined as the irreversible loss of the integration of the organism; when death occurs, the organism is irreversibly dis-integrated.8

According to currently accepted standards, there are 2 ways to determine that this final state of death has occurred: brain death and cardiocirculatory death.8,9 By using either of these determinations, the state is death when it is

irreversible.

Several professional societies, including the Society for Critical Care Medicine and the Institute of Medicine (in 3 separate reports), have argued for a weak construal of irreversibility, whereby the state will not be reversed (ie, there is a do-not-resuscitate order).1,2,10–13 This construal is actually based on the premise that loss of circulation ought not be

reversed, rather than will not be reversed. Other individuals argue for a stronger construal, whereby the state cannot be reversed even when resuscitation is attempted.14–19 By the weak construal of irreversibility, patients in the identical

www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/ peds.2008-1210

doi:10.1542/peds.2008-1210

Key Words

death, donation after cardiac death, end of life, organ donation, pediatrics

Abbreviations

DCD— donation after cardiac death CPR— cardiopulmonary resuscitation SA/A—strongly agree or agree D/SD— disagree or strongly disagree

Accepted for publication Jul 29, 2008 Address correspondence to Ari R. Joffe, MD, Department of Pediatrics, 3A3.07 Stollery Children’s Hospital, 8440 112 St, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada T6G 2B7. E-mail: ajoffe@cha. ab.ca

physiologic state are dead or alive on the basis of their location and prediction of a future event (attempted resus-citation). By current DCD protocols, 1 patient whose heart has stopped for 2 minutes (in Pittsburgh14and according to

the Society of Critical Care Medicine11) or 5 minutes (in

Canada1 and most sites in the United States11–13) or 10

minutes (in some parts of Europe13) is pronounced dead for

organ donation, whereas another identical patient whose heart has stopped for 10 minutes and then has cardiopul-monary resuscitation (CPR) is not pronounced dead and survives. If irreversible means “not capable of being re-versed” then, after 10 minutes of absent circulation, with-out the intention to intervene, the patient’s prognosis may be death, and the physiologic state may be dying.7,14,19–21

There are⬎30 case reports of the “Lazarus phenomenon” in which a patient is found to have spontaneous circula-tion, sometimes with good neurologic outcome, after hav-ing been declared dead minutes earlier on the basis of absent circulation.7,22–24 With resuscitation attempted,

ab-sent circulation for⬎10 minutes may be reversible and not associated with inevitable brain death.25–27

We set out to determine whether pediatricians agree that the patient who undergoes DCD is truly dead. We hypothesized that different ways of asking this question would reveal whether these pediatricians believe that the patient who undergoes DCD is dead.

METHODS

Questionnaire Administration

All pediatricians who are affiliated with the Stollery Chil-dren’s Hospital were mailed the survey. A cover letter emphasized the need to read the background information before answering the questions and that “the questions are not concerned with the decision to be allowed to die. In each ‘scenario,’ the decision to be allowed to die has al-ready been made and, thus, is not relevant to the question-naire.” Nonresponders were sent the survey at 3-week intervals for up to 2 additional mailings.

Questionnaire Development

The survey was modified from our previous survey of university student opinions about DCD.28 To generate

the items for the questionnaire, we searched Medline from 1980 to 2005 for articles on DCD. This process was followed by collaborative creation of the background section and questions for the survey by the authors. Pilot testing of the survey was done by nonmedical, univer-sity-educated lay people (n⫽9) and an ethics professor at our university. Each pilot test was followed by an informal semistructured interview by 1 of the authors to ensure clarity, realism, validity, and ease of completion of the questionnaire. After minor modifications, the sur-vey was approved by all of the authors.

Questionnaire Content

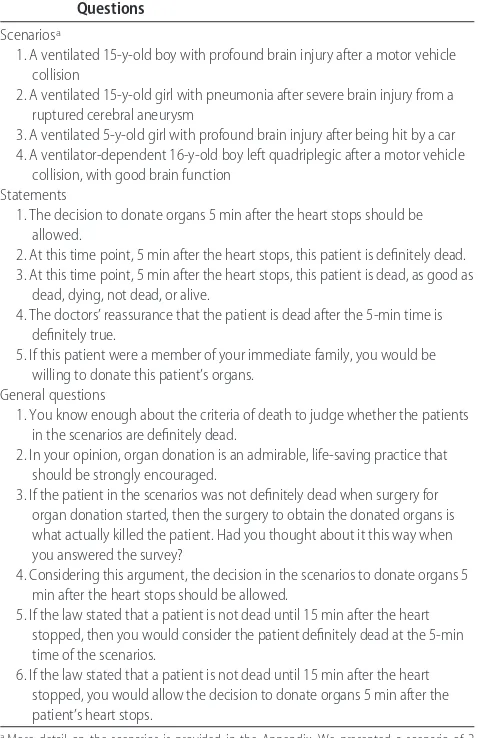

The background section described the organ shortage and explained that organ donation after death pro-nounced by cardiocirculatory criteria is possible and, with consent, is done 5 minutes after absent circulation. Also described were autoresuscitation (and the Lazarus phenomenon), the construals of irreversibility, the lack of brain death after 5 minutes of absent circulation, and the potential unconscious conflicts of interest of the physician (Table 1).1,2,7,10 –20,22–24,29 –33We presented 4

pa-tient scenarios. Each scenario was followed by the same 5 statements to be answered on a 5-point Likert-type scale. Each question referred to decisions after 5 minutes of absent circulation, the currently accepted time of death in DCD protocols. The final page of the survey asked some general questions and comfort level in re-sponding to the survey (Table 2). The study was ap-proved by the health research ethics board of our uni-versity, and return of a completed survey was considered consent to participate.

Statistics

Anonymous data were entered into a computer database (Microsoft Excel [Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA]).

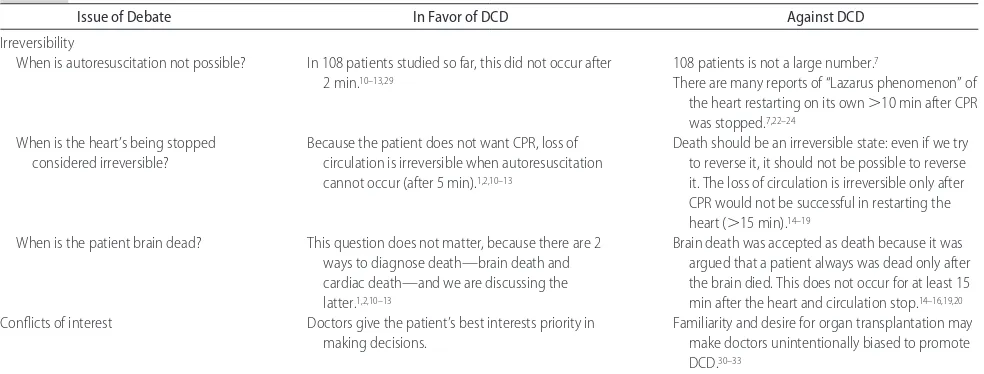

Re-TABLE 1 Summary of Presented Issues That Are Debated Regarding DCD

Issue of Debate In Favor of DCD Against DCD

Irreversibility

When is autoresuscitation not possible? In 108 patients studied so far, this did not occur after 108 patients is not a large number.7

2 min.10–13,29 There are many reports of “Lazarus phenomenon” of

the heart restarting on its own⬎10 min after CPR was stopped.7,22–24

When is the heart’s being stopped considered irreversible?

Because the patient does not want CPR, loss of circulation is irreversible when autoresuscitation cannot occur (after 5 min).1,2,10–13

Death should be an irreversible state: even if we try to reverse it, it should not be possible to reverse it. The loss of circulation is irreversible only after CPR would not be successful in restarting the heart (⬎15 min).14–19

When is the patient brain dead? This question does not matter, because there are 2 ways to diagnose death—brain death and cardiac death—and we are discussing the latter.1,2,10–13

Brain death was accepted as death because it was argued that a patient always was dead only after the brain died. This does not occur for at least 15 min after the heart and circulation stop.14–16,19,20

Conflicts of interest Doctors give the patient’s best interests priority in

making decisions.

sponses were analyzed by using standard tabulations. Variables expressed as percentages were used to report the proportion of respondents with different answers. The responses of 2 predefined groups of pediatricians (transplant specialties including gastroenterology, pul-monology, cardiology, and nephrology versus all others) were compared using the2test, withP⬍.05 without

correction for multiple comparisons considered signifi-cant. For comparisons, responses were divided into 3 categories: strongly agree or agree (SA/A), uncertain, and disagree or strongly disagree (D/SD). For the ques-tion about the state of the patient, the 3 categories were (1) dead, (2) as good as dead, and (3) dying, not dead, or alive.

RESULTS

During the academic year 2006 –2007, the question-naire was mailed to 147 pediatricians. The response rate was 80 (54%) of 147. The pediatricians had been

in practice for⬍5 years for 18 (23%), 5 to 10 years for 19 (24%), and ⬎10 years for 40 (50%). Of respon-dents, 41 (51%) were male, 54 (68%) were subspe-cialized, and 11 (14%) were in transplant specialties (with a response rate of 58% [11 of 19]).

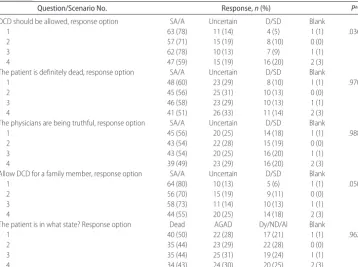

Responses to the Scenarios: All Pediatricians

The responses to each of the questions are shown in Table 3. When given a patient described as dead accord-ing to DCD protocols,ⱕ60% of pediatricians responded SA/A that the patient is definitely dead, ⱕ50% re-sponded that the patient is dead, andⱕ56% responded SA/A that the physicians are being truthful when calling the patient dead. More than 70% of all respondents were willing to allow donation of organs at the 5-minute time of absent circulation, except for scenario 4 (Table 3). Of respondents, 68 (85%) responded SA/A that DCD should be allowed on at least 1 scenario, and 38 (48%) responded uncertain or D/SD that DCD should be al-lowed on at least 1 scenario.

Although the patients in the 4 scenarios were in the identical physiologic state, with absent circulation for 5 minutes, 8 (10%) of respondents did not consistently consider the patients definitely dead between scenarios (Fig 1). Similarly, 12 (15%) respondents did not consis-tently consider the patients in the state called “dead” between scenarios (Fig 2). On at least 1 of the scenarios, 38 (48%) responded uncertain or D/SD that the patient is definitely dead. More respondents were uncomfort-able with allowing DCD for the patient in the scenario or a family member in scenario 4 (although there was no difference in their response to the questions about whether the donor would be dead).

Responses to the General Questions: All Pediatricians

The majority, 78 (98%), responded SA/A that “organ donation is an admirable life-saving practice that should be strongly encouraged.” When stated, “You know enough about the criteria of death to judge whether the patients in the scenarios are definitely dead,” 48 (60%) responded SA/A, 18 (23%) were uncertain, and 12 (15%) responded D/SD. When asked, “If the patient in the scenarios was not definitely dead when surgery for organ donation started, then the surgery to obtain the donated organs is what actually killed the patient. Had you thought about it this way when you answered the survey?” 51 (64%) responded “yes,” and 28 (35%) re-sponded “no.” This argument had not been suggested in the background information. When the survey stated, “Considering this argument, the decision in the scenar-ios to donate organs 5 minutes after the heart stops should be allowed,” 48 (60%) of 80 responded SA/A, 22 (28%) of 80 were uncertain, and 9 (11%) of 80 re-sponded SD/D. The responses to the same question be-fore the given argument (excluding scenario 4) were as follows: SA/A 182 (76%) of 240, uncertain 36 (15%) of 240, and SD/D 19 (8%) of 240 (P⫽.018).

More specific questions were asked about the timing of pronouncing death (Table 4). For those who re-sponded SA/A to allow DCD at 5 minutes on at least 1

TABLE 2 Survey Content: Scenarios, Statements, and General Questions

Scenariosa

1. A ventilated 15-y-old boy with profound brain injury after a motor vehicle collision

2. A ventilated 15-y-old girl with pneumonia after severe brain injury from a ruptured cerebral aneurysm

3. A ventilated 5-y-old girl with profound brain injury after being hit by a car 4. A ventilator-dependent 16-y-old boy left quadriplegic after a motor vehicle

collision, with good brain function Statements

1. The decision to donate organs 5 min after the heart stops should be allowed.

2. At this time point, 5 min after the heart stops, this patient is definitely dead. 3. At this time point, 5 min after the heart stops, this patient is dead, as good as

dead, dying, not dead, or alive.

4. The doctors’ reassurance that the patient is dead after the 5-min time is definitely true.

5. If this patient were a member of your immediate family, you would be willing to donate this patient’s organs.

General questions

1. You know enough about the criteria of death to judge whether the patients in the scenarios are definitely dead.

2. In your opinion, organ donation is an admirable, life-saving practice that should be strongly encouraged.

3. If the patient in the scenarios was not definitely dead when surgery for organ donation started, then the surgery to obtain the donated organs is what actually killed the patient. Had you thought about it this way when you answered the survey?

4. Considering this argument, the decision in the scenarios to donate organs 5 min after the heart stops should be allowed.

5. If the law stated that a patient is not dead until 15 min after the heart stopped, then you would consider the patient definitely dead at the 5-min time of the scenarios.

6. If the law stated that a patient is not dead until 15 min after the heart stopped, you would allow the decision to donate organs 5 min after the patient’s heart stops.

scenario, if the law stated that the patient was not dead until 15 minutes after circulation stops, then 27 (40%) would still consider the patient definitely dead at 5 min-utes, whereas only 17 (25%) would still allow the do-nation to start at 5 minutes. Fewer than 5% of respon-dents answered SA/A to allow DCD while also answering D/SD that the patient is definitely dead.

Responses of Pediatricians in Versus Not in a Transplant Specialty

There were no differences in the survey response rate or in the responses to any of the questions between the 11

pediatricians in a transplant specialty versus the 69 who were not in a transplant specialty.

DISCUSSION

There are several important findings from this study of pediatricians’ opinions regarding DCD. First, ⱕ60% of the respondents consider the patients in the DCD sce-narios dead, andⱕ56% consider the physicians truthful in describing the patients as definitely dead. Second, in 15% of cases, respondents were inconsistent in consid-ering patients in the different scenarios as dead, despite their identical physiologic state of absent circulation for

FIGURE 1

Pediatrician responses to the question on the state of the patient after 5 minutes of absent circulation. AGAD indicates as good as dead.o, those who responded that the patient was in that state;f, those who responded that the patient was not in that state.

FIGURE 2

Pediatrician responses to the statement that the patient was definitely dead after 5 minutes of absent circulation. U indicates uncertain.o, those who had the stated re-sponse;f, those who did not have the stated response.

TABLE 3 Responses of Pediatricians to the 4 Scenarios Describing Patients Eligible for DCD (nⴝ80)

Question/Scenario No. Response,n(%) Pa

DCD should be allowed, response option SA/A Uncertain D/SD Blank

1 63 (78) 11 (14) 4 (5) 1 (1) .036

2 57 (71) 15 (19) 8 (10) 0 (0)

3 62 (78) 10 (13) 7 (9) 1 (1)

4 47 (59) 15 (19) 16 (20) 2 (3)

The patient is definitely dead, response option SA/A Uncertain D/SD Blank

1 48 (60) 23 (29) 8 (10) 1 (1) .970

2 45 (56) 25 (31) 10 (13) 0 (0)

3 46 (58) 23 (29) 10 (13) 1 (1)

4 41 (51) 26 (33) 11 (14) 2 (3)

The physicians are being truthful, response option SA/A Uncertain D/SD Blank

1 45 (56) 20 (25) 14 (18) 1 (1) .988

2 43 (54) 22 (28) 15 (19) 0 (0)

3 43 (54) 20 (25) 16 (20) 1 (1)

4 39 (49) 23 (29) 16 (20) 2 (3)

Allow DCD for a family member, response option SA/A Uncertain D/SD Blank

1 64 (80) 10 (13) 5 (6) 1 (1) .050

2 56 (70) 15 (19) 9 (11) 0 (0)

3 58 (73) 11 (14) 10 (13) 1 (1)

4 44 (55) 20 (25) 14 (18) 2 (3)

The patient is in what state? Response option Dead AGAD Dy/ND/Al Blank

1 40 (50) 22 (28) 17 (21) 1 (1) .962

2 35 (44) 23 (29) 22 (28) 0 (0)

3 35 (44) 25 (31) 19 (24) 1 (1)

4 34 (43) 24 (30) 20 (25) 2 (3)

AGAD indicates as good as dead; Dy/ND/Al, dying/not dead/alive.

5 minutes. In at least 1 of the scenarios, 48% responded uncertain or D/SD that the patient is definitely dead. Third, many (35%) respondents had not considered the following possibility: if the patient was not dead, then organ donation is what killed the patient. After consid-ering this possibility, only 60% of all respondents re-sponded SA/A that DCD should be allowed after 5 min-utes of absent circulation. Finally, although most (85%) respondents answered SA/A that DCD should be al-lowed on at least 1 scenario, only 3.8% were willing to allow DCD despite responding D/SD that the patient was definitely dead, suggesting support for the dead-donor rule. These results have important implications for pub-lic popub-licy.

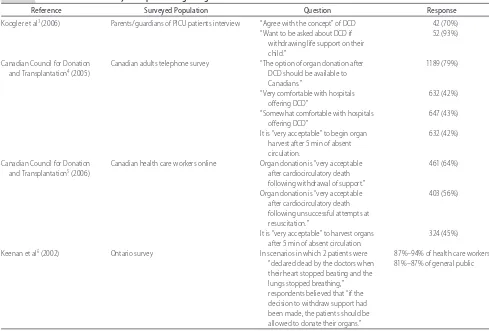

Previous surveys of health care workers and the pub-lic are not directly comparable to our survey (Table 5).3–6

These surveys did not communicate that the ethical concern of when to declare a person dead, with irrevers-ible cessation of circulation, is central to the debate regarding DCD. There is a significant difference between asking whether organs can be donated after death and asking when death has occurred. Consistent with these other surveys, we found that a majority (76%) of re-spondents responded SA/A with the statement that “the decision to donate organs 5 minutes after the heart stops should be allowed” (excluding scenario 4), yet only 60% responded SA/A to this same statement (P⫽.018) when asked to consider the possibility that “if the patient in the

TABLE 4 Pediatrician Responses to Questions About the Timing of Death in DCD Scenarios

Question/Scenario SA/A to Allow DCD in at

Least 1 Scenario (n⫽68),n(%)

SA/A to Allow DCD and D/SD

That the Patient Is Definitely Dead,n(%)

SA/A Uncertain D/SD

If the law stated that a patient is not dead until 15 min after circulation stopped, then you would still consider the patient definitely dead at 5 min after the patient’s heart stopped.

27 (40) 11 (22) 11 (22)

If the law stated that a patient is not dead until 15 min after the circulation stopped, then you would allow the donation to start 5 min after the patient’s heart stopped.

17 (25) 24 (35) 26 (38)

Scenario 1 3/80 (3.8)

Scenario 2 3/80 (3.8)

Scenario 3 3/80 (3.8)

Scenario 4 3/80 (3.8)

All scenarios 2/80 (2.5)

Any 1 scenario 4/80 (5.0)

TABLE 5 Selected Previous Surveys for Opinions Regarding DCD

Reference Surveyed Population Question Response

Koogler et al3(2006) Parents/guardians of PICU patients interview “Agree with the concept” of DCD 42 (70%)

“Want to be asked about DCD if withdrawing life support on their child.”

52 (93%)

Canadian Council for Donation and Transplantation4(2005)

Canadian adults telephone survey “The option of organ donation after DCD should be available to Canadians.”

1189 (79%)

“Very comfortable with hospitals offering DCD”

632 (42%)

“Somewhat comfortable with hospitals offering DCD”

647 (43%)

It is “very acceptable” to begin organ harvest after 5 min of absent circulation.

632 (42%)

Canadian Council for Donation and Transplantation5(2006)

Canadian health care workers online Organ donation is “very acceptable after cardiocirculatory death following withdrawal of support.”

461 (64%)

Organ donation is “very acceptable after cardiocirculatory death following unsuccessful attempts at resuscitation.”

403 (56%)

It is “very acceptable” to harvest organs after 5 min of absent circulation.

324 (45%)

Keenan et al6(2002) Ontario survey In scenarios in which 2 patients were 87%–94% of health care workers

“declared dead by the doctors when their heart stopped beating and the lungs stopped breathing,” respondents believed that “if the decision to withdraw support had been made, the patients should be allowed to donate their organs.”

scenarios was not definitely dead when surgery for or-gan donation started, then the surgery to obtain the donated organs is what actually killed the patient.” If a patient is not dead when organ harvest begins, then some may still argue that the organ harvest is not the cause of death, because the patient would surely be dead some minutes after harvest begins (well before, eg, death from kidney failure occurs); however, we believe that the surgical incisions, with removal of kidneys (liver and possibly lungs and heart), attendant blood loss, and or-gan preservation techniques have a high risk for hasten-ing death and preventhasten-ing any possibility of autoresusci-tation.

Some of the background information provided may be considered controversial (Table 1). The information contained the following: “From studies of a total of 108 adult patients, we know that none had their heart restart on its own after 2 minutes.10,11,29 However, there are

many case reports of a patient’s heart restarting on its own 5 to 10 minutes after it could not be started with CPR in the hospital (called the ‘Lazarus phenomenon’). In these cases, some of the patients have survived with good brain function.”7,22–24They were also given that, “to

legally diagnose death, a doctor should know that the heart has stopped irreversibly.8,9Some think this should

mean that the heart cannot restart on its own (cannot autroresuscitate).1,2,10–13They argue that because a

deci-sion has been made to not try to restart the heart with CPR, it is autoresuscitation that is important. Others think irreversibility means that the heart cannot be started even if we try.14–19 For example, if we try to

restart a heart with our modern medicine and CPR, even after 10 to 15 minutes of no heartbeat, often the heart can be restarted and the patient survives.25–27They claim

it does not make sense that 1 patient whose heart has stopped for 5 minutes is pronounced dead for organ donation, while another identical patient whose heart has stopped for 5 minutes and has CPR is not pro-nounced dead and survives.”7We believe the

informa-tion is accurate and reflects an honest interpretainforma-tion of the debate concerning the ethics of DCD.

This survey indicates that when death is defined as the irreversible absence of circulation, it is not clear that a weak construal of irreversibility is acceptable. Across the 4 scenarios, 38 (48%) of 80 responded uncertain or D/SD on at least 1 scenario when told, “at this time point, 5 minutes after his heart stops, this patient is definitely dead.” This point has been argued by ethicists and philosophers, many of whom suggest that irrevers-ible means “not capable of being reversed.” Accordingly, after 5 or 10 minutes of absent circulation, without the intention to intervene, the patient’s prognosis is death, and their physiologic state is dying.7,14,19–21

We do not believe that the frequent response that DCD should be allowed was based on a decision to ignore the dead-donor rule. We did not ask respondents whether they agreed with the consideration that organ harvest is what kills the donor. It is possible that those who allowed DCD despite this argument (60%) did not agree with the argument. Similarly, we did not ask re-spondents whether DCD should be allowed if the donor

is not dead. On each scenario (Table 3), 59% to 78% responded SA/A to allow DCD, and 84% to 89% re-sponded SA/A or uncertain that the donor is definitely dead, suggesting support for the dead-donor rule. On each scenario (Table 4), only 3.8% of respondents an-swered SA/A to allow DCD and D/SD that the patient is definitely dead, again suggesting support for the dead-donor rule. Furthermore, we did not present the com-plex ethical, religious, and legal implications of abandon-ing the dead-donor rule.

The strengths of this survey include the acceptable response rate (54%) and the rigorous survey develop-ment methods, including pretesting confirmation of the clarity of the questions and possible responses. Limita-tions include the absence of open-ended quesLimita-tions and possible discrepancies between stated behavior and ac-tual practice when faced with DCD clinically. Because this survey targeted pediatricians at our hospital, it may not be representative of pediatricians elsewhere. Never-theless, for similar questions, the results of our survey are remarkably similar to other health care worker sur-veys regarding DCD (Table 5).3–6 Some surveys showed

that many health care workers and designated request-ors for organ donation were not comfortable that the DCD donor is dead.33,34

CONCLUSIONS

We believe that these limitations do not affect our main conclusion. We found that, among the surveyed pedia-tricians, there is far from uniform acceptance that the DCD patient is dead or that DCD should be allowed. In the least, this survey suggests that additional debate about the concept of irreversibility as it applies to card-iocirculatory death is needed. We suggest that when considering DCD and when asking for consent to DCD, those involved be fully informed of this debate. This is important if we are to follow the dead-donor rule.35

APPENDIX

Scenario 1

A 15-year-old boy was in a motor vehicle collision. Two weeks after the injury, he is still in a coma. The neurol-ogists think that he will have very profound brain dam-age if he survives. He needs life support with a ventilator and inotropes. This boy told his parents a few times in the past that if he were ever in a coma and going to have severe brain damage, then he wanted them to let him die. The doctors discuss this request with the family, and they decide to take him off life support and let him die. The parents say that he always wanted to donate his organs after he dies. The doctors tell them that this is possible. He can be taken to the operating room and have the life support stopped. Five minutes after his circulation stops, he will be pronounced dead. Then surgeons could make incisions to recover both of his kidneys for organ donation. The family decides that this is what the patient would have wanted.

Scenario 2

recovered with severe disability. The doctors say that she will never be able to walk or feed herself. Although she can speak a few words with people, she has severe brain damage. Two weeks later, she develops severe pneumo-nia from choking on her food. She is taken back to intensive care and needs life support with a ventilator and inotropes. The doctors think that she may not sur-vive this pneumonia even with the ventilator. The girl’s parents say that she told them several times before her brain aneurysm that she would not want to live if she had severe brain damage. The doctors discuss this with the family, and the family and doctors decide to take her off life support and let her die.

The family says that she always wanted to donate her organs after she dies. The doctors tell the family that this is possible. She can be taken to the operating room and have the life support stopped. Five minutes after her circulation stops, she will be pronounced dead. Then surgeons could make incisions to recover both of her kidneys for organ donation. The family decides that this is what the patient would have wanted.

Scenario 3

A 5-year-old girl was hit by a car crossing the street. It is now 2 wk after the injury, and she is still in a coma. She needs life support with a ventilator and inotropes. The doctors tell the parents that she may never wake up, and, if she does, that she will not be able to walk or feed herself and will have profound brain damage. After dis-cussion with the family and doctors, the parents decide that it is best for the patient to take her off life support and let her die.

The parents ask whether the girl can donate her or-gans. The doctors tell the parents that this is possible. She can be taken to the operating room and have the life support stopped. Five minutes after her circulation stops, she will be pronounced dead. Then surgeons could make incisions to recover both of her kidneys for organ dona-tion. The parents decide that this should be done.

Scenario 4

A 16-year-old boy was in a car collision and has had a severe injury to the cervical spine. This has left him permanently and completely paralyzed from the neck down and unable to breath on his own. He has had a tracheostomy so that he can be on a ventilator perma-nently. Two months later, he discussed with his parents that he does not want to be kept on a ventilator. He tells them that he wants to be taken off the ventilator and allowed to die. He tells them that he does not want to live paralyzed and on a ventilator. The patient and his parents discuss this with the doctors, and it is decided to do what he wishes and take him off the ventilator and allow him to die.

The boy says that he wants to donate his organs after he dies. The doctors tell him and his family that this is possible. He can be taken to the operating room and have the ventilator stopped. Five minutes after his cir-culation stops, he will be pronounced dead. Then sur-geons could make incisions to recover both of his

kid-neys for organ donation. The boy and his family decide that this is what they want to be done.

REFERENCES

1. Shemie SD, Baker AJ, Knoll G, et al. Donation after cardiocir-culatory death in Canada.CMAJ.2006;175(8):S1

2. Bernat JL, D’Alessandro AM, Port FK, et al. Report of a na-tional conference on donation after cardiac death.Am J

Trans-plant.2006;6(2):281–291

3. Koogler TK, Stark A, Kaplan B, Myers GR. Parents’/guardians’ views on donation after cardiac death. Crit Care Med. 2006; 33(12 suppl):A105

4. Canadian Council for Donation and Transplantation. Public awareness and attitudes on organ and tissue donation and transplantation including donation after cardiac death; Decem-ber 2005. Available at: www.ccdt.ca/english/publications/ surveys.html. Accessed March 31, 2008

5. Canadian Council for Donation and Transplantation. Health professional awareness and attitudes on organ and tissue do-nation and transplantation; August 2006. Available at: www. ccdt.ca/english/publications/surveys.html or www.zoomerang. com/web/SharedResults/SharedResultsSurveyResultsPage.aspx? ID⫽L22GV2MKQ9ZS. Accessed March 31, 2008

6. Keenan SP, Hoffmaster B, Rutledge F, Eberhard J, Chen LM, Sibbald WJ. Attitudes regarding organ donation from non-heart-beating donors.J Crit Care.2002;17(1):29 –38

7. Joffe AR. The ethics of donation and transplantation: are def-initions of death being distorted for organ transplantation?

Philos Ethics Humanit Med.2007;2:28

8. President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research. Defining Death: Medical, Legal and Ethical Issues in the Determination of

Death. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 1981

9. Bernat JL, Culver CM, Gert B. On the definition and criterion of death.Ann Intern Med.1981;94(3):389 –394

10. Ethics Committee, American College of Critical Care Medicine, Society of Critical Care Medicine. Recommendations for non-heartbeating organ donation. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(9): 1826 –1831

11. Institute of Medicine; Potts J. Non-heart-beating Organ

Transplantation: Medical and Ethical Issues in Procurement.

Wash-ington, DC: National Academies Press; 1997

12. Institute of Medicine, Committee on Non-heart-beating Trans-plantation.Non-heart-beating Organ Transplantation. Washing-ton, DC: National Academies Press; 2000

13. Institute of Medicine, Childress JF, Liverman CT, eds.Organ

Donation: Opportunities for Action. Washington, DC: National

Academies Press; 2006

14. Lynn J. Are the patients who become organ donors under the Pittsburgh protocol for “non-heart-beating donors” really dead?Kennedy Inst Ethics J.1993;3(2):167–178

15. Zamperetti N, Bellomo R, Ronco C. Defining death in non-heart beating organ donors.J Med Ethics.2003;29(3):182–185 16. Whetstine L, Streat S, Darwin M, Crippen D. Pro/con ethics debate: when is dead really dead?Crit Care.2005;9(6):538 –542 17. Bartlett ET. Differences between death and dying.J Med Ethics.

1995;21(5):270 –276

18. Weisbard AJ. A polemic on principles: reflections on the Pitts-burgh protocol.Kennedy Inst Ethics J.1993;3(2):217–230 19. Menikoff J. The importance of being dead: non-heart-beating

organ donation.Issues Law Med.2002;18(1):3–20

20. Menikoff J. Doubts about death: the silence of the Institute of Medicine.J Law Med Ethics.1998;26(2):157–165

21. McMahan J. An alternative to brain death.J Law Med Ethics.

2006;34(1):44 – 48

return of spontaneous circulation after cessation of resuscita-tion (Lazarus phenomenon). Resuscitation. 1998;39(1–2): 125–128

23. Adhiyaman V, Sundaram R. The Lazarus phenomenon.J R Coll

Physicians Edinb.2002;32:9 –13

24. Ka¨ma¨ra¨inen A, Virkkunen I, Holopainen L, Erkkila EP, Yli-Hankala A, Tenhunen J. Spontaneous defibrillation after ces-sation of resuscitation in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a case of Lazarus phenomenon.Resuscitation.2007;75(3):543–546 25. Lo´pez-Herce J, Garcia C, Dominguez P, et al. Characteristics

and outcome of cardiorespiratory arrest in children.

Resuscita-tion.2004;63(3):311–320

26. Lo´pez-Herce J, Garcia C, Dominguez P, et al. Outcome of out-of-hospital cardiorespiratory arrest in children. Pediatr

Emerg Care.2005;21(12):807– 815

27. Herlitz J, Svensson L, Engdahl J, Angquist KA, Silfverstolpe J, Holmberg S. Association between interval between call for ambulance and return of spontaneous circulation and survival in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2006;71(1): 40 – 46

28. Joffe AR, Byrne R, Anton NR, deCaen RA. Donation after cardiac death: a survey of university student opinions on death

and donation.Intensive Care Med.August 1, 2008 [epub ahead of print]

29. Youngner SJ, Arnold RM, DeVita MA. When is “dead”?

Hast-ings Cent Rep.1999;29:14 –21

30. Doig CJ, Rocker G. Retrieving organs from non-heart-beating organ donors: a review of medical and ethical issues. Can J

Anesth.2003;50(10):1069 –1076

31. Doig CJ. Is the Canadian health care system ready for donation after cardiac death? A note of caution. CMAJ.2006;175(8): 905–906

32. Rady MY, Verheijde JL, McGregor J. Organ donation after circulatory death: the forgotten donor?Crit Care.2006;10(5): 166

33. Mandell MS, Zamudio S, Seem D, et al. National evaluation of healthcare provider attitudes toward organ donation after car-diac death.Crit Care Med.2006;34(12):2952–2958

34. D’Alessandro AM, Peltier JW, Phelps JE. An empirical exami-nation of the antecedents of the acceptance of doexami-nation after cardiac death by health care professionals.Am J Transplant.

2008;8(1):193–200

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2008-1210

2008;122;e967

Pediatrics

Ari R. Joffe, Natalie R. Anton and Allan R. deCaen

Donors Dead?

Survey of Pediatricians' Opinions on Donation After Cardiac Death: Are the

Services

Updated Information &

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/122/5/e967 including high resolution figures, can be found at:

References

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/122/5/e967#BIBL This article cites 28 articles, 4 of which you can access for free at:

Subspecialty Collections

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/ethics:bioethics_sub Ethics/Bioethics

following collection(s):

This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

Permissions & Licensing

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml in its entirety can be found online at:

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

Reprints

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2008-1210

2008;122;e967

Pediatrics

Ari R. Joffe, Natalie R. Anton and Allan R. deCaen

Donors Dead?

Survey of Pediatricians' Opinions on Donation After Cardiac Death: Are the

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/122/5/e967

located on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 1073-0397.