Sleep Position of Low Birth Weight Infants

Louis Vernacchio, MD, MSc*‡; Michael J. Corwin, MD*; Samuel M. Lesko, MD, MPH*;

Richard M. Vezina, MPH*; Carl E. Hunt, MD§; Howard J. Hoffman, MA储; Marian Willinger, PhD¶; and Allen A. Mitchell, MD*

ABSTRACT. Objectives. To describe sleep positions among low birth weight infants, variations in sleep po-sition according to birth weight, and changes in sleep position over time. To analyze risk factors and influences associated with prone sleep.

Design. Prospective cohort study.

Setting. Massachusetts and Ohio, 1995–1998.

Study Participants. Mothers of 907 low birth weight infants.

Results. At 1, 3, and 6 months after hospital dis-charge, the prevalence of prone sleeping was 15.5%, 26.8%, and 28.3%, respectively. The corresponding rates for supine sleeping were 23.8%, 37.9%, and 50.2% and for side sleeping were 57.3%, 32.4%, and 20.6%. Very low birth weight (VLBW) infants (<1500 g) were most likely to be placed in the prone position. From 1995 through 1998, prone sleeping 1 month after hospital discharge declined among all low birth weight infants from 19.9% to 11.4%; among VLBW infants, the decline in prone sleeping was replaced almost entirely by an increase in side sleeping, whereas in larger low birth weight infants, it was replaced primarily by supine sleeping. Among mothers who placed their infants to sleep in nonprone positions, professional medical advice was cited most frequently as the most influential reason, whereas among mothers of prone-sleeping infants, the infant’s prefer-ence was cited most frequently. However, mothers of prone-sleeping VLBW infants also frequently cited the influence of medical professionals and nursery practices as most important in the choice of sleeping position. The factors most strongly associated with prone sleeping were single marital status (odds ratio [OR]: 3.0; 95% con-fidence interval [CI]: 1.5– 6.2), black race (OR: 2.6; 95% CI: 1.5– 4.5), birth weight<1500 g (OR: 2.4; 95% CI: 1.3– 4.3), and multiparity (OR: 2.1, 95% CI: 1.2–3.5).

Conclusions. Prone sleep decreased among low birth weight infants from 1995 to 1998. However, VLBW in-fants, who are at very high risk for sudden infant death syndrome, are more likely to sleep prone than larger low birth weight infants.Pediatrics2003;111:633– 640;sudden infant death syndrome, low birth weight, sleep.

ABBREVIATIONS. SIDS, sudden infant death syndrome; AAP, American Academy of Pediatrics; SD, standard deviation; VLBW, very low birth weight; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

S

udden infant death syndrome (SIDS) is the leading cause of death among infants beyond the neonatal period. The SIDS-specific infant mortality rate was 66.9 per 100 000 live births in the United States in 1999.1 A number of studies have shown that low birth weight and preterm infants are at especially high risk for SIDS, approximately 3 to 6 times that of full-term, non-low birth weight in-fants.2– 8Furthermore, the association between prone sleeping and SIDS seems to be even stronger among low birth weight infants than it is known to be among non-low birth weight infants.9The only pub-lished data to date on the sleeping position of low birth weight infants came from the National Infant Sleep Position Study, a telephone survey conducted from 1992 through 1996.10 Data from this study did not demonstrate a difference in the rate of prone sleeping between low birth weight and non-low birth weight infants; however, only 4% of the sample were low birth weight, and additional stratification of the low birth weight sample was not possible.The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) has recommended against prone sleep since 1992. The initial AAP statement regarding positioning and SIDS made a general recommendation that healthy infants be placed on their side or back for sleep.11 The statement, however, mentioned several caveats including that “for premature infants with respira-tory distress . . . prone may well be the position of choice.” In 1996, the AAP modified the previous recommendation to emphasize that supine sleeping was preferred over side sleeping and stated “there are no studies suggesting that recovered preterm infants are exempt from the increased risk of SIDS when placed prone.”12 The AAP strengthened its comments about preterm infants in 2000, stating “There are no data suggesting that strategies de-signed to reduce risk in full-term infants should not also be applied to premature infants. The relation-ship to prone sleeping, for example, has been shown From the *Slone Epidemiology Center, Boston University, Boston,

Massa-chusetts; ‡Department of Pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Mas-sachusetts; §Department of Pediatrics, Medical College of Ohio, Toledo, Ohio;储National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland; and ¶National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland.

Dr Hunt is currently at National Center on Sleep Disorders Research, National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland.

Received for publication Feb 27, 2002; accepted Jul 12, 2002.

The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does men-tion of trade names, commercial products, or organizamen-tions imply endorse-ment by the US governendorse-ment.

Reprint requests to (L.V.) Slone Epidemiology Center at Boston University, 1010 Commonwealth Ave, Boston, MA 02215. E-mail: lvernacchio@slone. bu.edu

to hold for infants of low birth weight as well as for those born with a normal birth weight at term.”13

Indeed, there have been a number of recent studies on the physiologic effects of sleep position in pre-term and low birth weight infants that support the AAP’s recommendations. No differences have been observed among preterm infants in the incidence of periodic breathing, apnea, bradycardia, or desatura-tions below 80% according to sleep position.14,15 Fur-thermore, preterm and low birth weight infants placed prone have higher heart rates, reduced car-diac variability, and reduced respiratory variability in quiet and active sleep, and less frequent awaken-ings in quiet sleep compared with those placed su-pine.14,16,17These characteristics have been observed in infants who later die of SIDS and may predispose them to a life-threatening event during sleep.18

We used a cohort of infants from the Infant Care Practices Study to describe the prevalence of various sleep positions among low birth weight infants, vari-ations in sleep position according to birth weight, and changes in sleep position trends from 1995 through 1998. We also analyzed risk factors and in-fluences associated with prone sleep.

METHODS

Infant Care Practices Study is a prospective, longitudinal cohort study with enrollments occurring between 1995 and 1998. A de-tailed description of the study design has been published previ-ously.19Briefly, women-infant pairs were recruited during obstet-rical admissions in Boston, Lowell, and Lawrence, Massachusetts, and Toledo, Ohio. To obtain the sample of low birth weight infants included in the current study, study personnel reviewed obstetri-cal records each working day to identify women who had deliv-ered live infants weighing ⬍2500 g in the previous 24 hours. Women were ineligible if they resided out-of-state or intended to move out-of-state in the subsequent 6 months, were not to be caring for the child, were not fluent in English or Spanish, or had a child with a major congenital malformation. Eligible women were contacted according to a list ordered by the terminal 2 digits of the mother’s medical record number. Baseline data were col-lected at the time of enrollment and follow-up mail questionnaires were administered at 1, 3, and 6 months after the infant’s hospital discharge. Mothers not responding to mailed questionnaires were interviewed by telephone.

In each of the questionnaires, the question related to sleep position was: “Last evening when you put your infant to bed for the night, how did you place him/her?” Answer options included: “Lying on stomach with face down,” “Lying on stomach with face to side,” “Lying on back,” “Lying on side,” “Propped in a sitting position,” “Other (specify),” and don’t know/can’t remember. For analysis, the first 2 options were combined into the category prone sleep and the other categories were maintained. Respondents were also asked if the last 24 hours had been typical for their infant.

In each questionnaire, respondents were asked: “What helped you decide what position to place your infant in to sleep?” Pos-sible answers included “Doctor,” “Nurse or other medical profes-sional,” “Family members or friends,” “Educational material given in hospital, office, or mail,” “Childbirth/prenatal classes,” “Books,’ ”Magazines, or newspapers,“ ”TV or radio,“ ”Followed what I did for other children,“ ”Followed what the nursery did,“ or ”Other (specify)“; multiple answers were allowed. Respondents were then asked: ”Which was the most important in helping you decide?“ with only 1 answer allowed.

Secular trends in sleep position were analyzed by Mantel Ex-tension2test. Risk factors for prone sleep were analyzed using multiple logistic regression. Variables included in the model were: year and site of enrollment; infant’s sex, gender, birth weight, singleton versus multiple birth, and postconceptional age at hos-pital discharge; mother’s race/ethnicity, age, education, marital status, and parity; and annual household income. For multiple

logistic regression analysis, if the value for a given variable was unknown for⬍5 subjects, those individuals were included in the reference category. If a value for a given variable was unknown for 5 or more subjects, a separate category for “unknown” was used in the model.

RESULTS

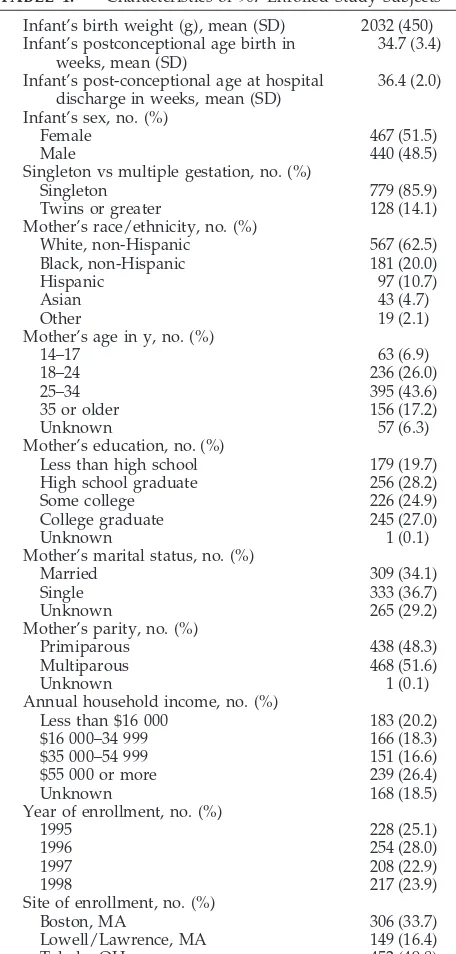

A total of 907 mother-infants pairs was enrolled. Characteristics of the study subjects are summarized in Table 1. The mean postconceptional age of the infants was 34.7 weeks (standard deviation [SD]⫾ 3.4 weeks) at birth, 36.4 weeks (SD⫾ 2.0 weeks) at the time of hospital discharge, 42.5 weeks (SD⫾3.6 weeks) at the 1-month interview, 52.0 weeks (SD⫾ 3.9 weeks) at the 3-month interview, and 66.0 weeks (SD ⫾ 5.0 weeks) at the 6-month interview. Fol-low-up data at 1, 3, and 6 months after hospital discharge were obtained on 744 (82.0%), 720 (79.4%), and 689 (76.0%) subjects, respectively. Response

TABLE 1. Characteristics of 907 Enrolled Study Subjects Infant’s birth weight (g), mean (SD) 2032 (450) Infant’s postconceptional age birth in

weeks, mean (SD)

34.7 (3.4)

Infant’s post-conceptional age at hospital discharge in weeks, mean (SD)

36.4 (2.0)

Infant’s sex, no. (%)

Female 467 (51.5)

Male 440 (48.5)

Singleton vs multiple gestation, no. (%)

Singleton 779 (85.9)

Twins or greater 128 (14.1) Mother’s race/ethnicity, no. (%)

White, non-Hispanic 567 (62.5) Black, non-Hispanic 181 (20.0)

Hispanic 97 (10.7)

Asian 43 (4.7)

Other 19 (2.1)

Mother’s age in y, no. (%)

14–17 63 (6.9)

18–24 236 (26.0)

25–34 395 (43.6)

35 or older 156 (17.2)

Unknown 57 (6.3)

Mother’s education, no. (%)

Less than high school 179 (19.7) High school graduate 256 (28.2)

Some college 226 (24.9)

College graduate 245 (27.0)

Unknown 1 (0.1)

Mother’s marital status, no. (%)

Married 309 (34.1)

Single 333 (36.7)

Unknown 265 (29.2)

Mother’s parity, no. (%)

Primiparous 438 (48.3)

Multiparous 468 (51.6)

Unknown 1 (0.1)

Annual household income, no. (%)

Less than $16 000 183 (20.2) $16 000–34 999 166 (18.3) $35 000–54 999 151 (16.6) $55 000 or more 239 (26.4)

Unknown 168 (18.5)

Year of enrollment, no. (%)

1995 228 (25.1)

1996 254 (28.0)

1997 208 (22.9)

1998 217 (23.9)

Site of enrollment, no. (%)

Boston, MA 306 (33.7)

Lowell/Lawrence, MA 149 (16.4)

rates were somewhat lower among women with the following characteristics: black, non-Hispanic race (71.3%, 68.0%, 58.0% at 1, 3, and 6 months, respec-tively), Hispanic ethnicity (77.3%, 68.0%, 52.6%), ed-ucated less than high school (68.7%, 63.1%, 51.4%), single (74.1%, 71.2%, 61.2%), and from households with an annual income ⬍$16 000 (68.9%, 66.7%, 56.8%).

Overall, the number of infants placed to sleep in the prone position the evening before the survey at 1, 3, and 6 months after hospital discharge was 115 (15.5%), 193 (26.8%), and 195 (28.3%), respectively. The corresponding figures for supine sleep were 177 (23.8%), 273 (37.9%), and 346 (50.2%) and for side sleep were 426 (57.3%), 233 (32.4%), and 142 (20.6%). Less than 4% of infants slept in sitting or other po-sitions at any time point. When asked if the previous 24 hours had been typical for their infant, 88.6%, 87.9%, and 92.0% responded affirmatively at 1, 3, and 6 months, respectively. Limiting the analysis to those respondents did not substantially change the results. Stratification by birth weight categories demon-strated that very low birth weight (VLBW) infants (⬍1500 g at birth) were most likely to be placed in the prone position at all 3 time points, especially the first follow-up (P ⫽.004 at 1 month; Fig 1).

Analysis of the secular trends in sleeping position 1 month after hospital discharge showed a declining

prevalence of prone sleep and an increasing preva-lence of supine sleep (Fig 2). For the enrollment years 1995 through 1998, the prevalence of prone sleep decreased from 19.9% to 11.4% (P for trend ⫽ .03), whereas the prevalence of supine sleeping increased from 13.7% to 36.2% (P for trend ⬍.0001). Secular trends in sleep position 1 month after hospital dis-charge stratified by birth weight are shown in Fig 3. Among VLBW infants, prone sleeping declined from 33.9% in 1995–1996 to 17.5% in 1997–1998, while side sleeping increased and supine sleeping remained un-changed. Among larger low birth weight infants, prone sleeping and side sleeping declined from 1995–1996 to 1997–1998, while supine sleeping in-creased.

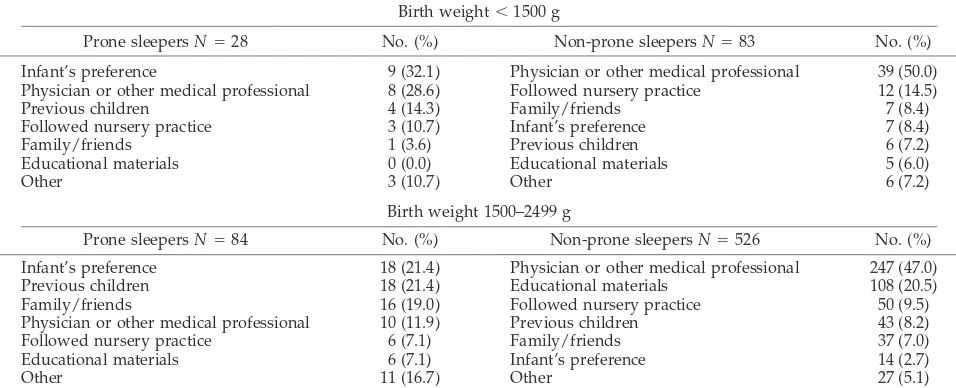

The factors reported by mothers to have the great-est influence on the choice of infant sleeping position are shown in Table 2. Among women whose infants slept in nonprone positions, physicians, and other medical professionals were cited most commonly as the primary influence (50.0% among mothers of VLBW infants and 47.0% among mothers of infants with birth weight 1500 –2499 g). Among those women whose infants slept prone, mothers of VLBW infants most frequently cited infant’s preference (32.1%) and physician or other medical professionals (28.6%), whereas mothers of infants with birth weight 1500 to 2499 g mentioned infant’s preference

and experience with previous children most fre-quently (21.4% each).

Multivariate analysis showed that birth weight

⬍1500 g, black race, single marital status, and mul-tiparity were all significant risk factors for prone sleep 1 month after hospital discharge (Table 3). A similar analysis of risk factors for prone sleep at 3 months after hospital discharge (which included the same variables as the 1-month model plus sleep po-sition at 1 month) identified prone sleep at 1 month as the strongest predictor (odds ratio [OR]: 14.8; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 8.3–26.6]). After adjustment for prone sleep at 1 month, the only factors that were significantly associated with prone sleep at 3 months after hospital discharge were enrollment in 1998 compared with 1995 (OR: 0.52; 95% CI: 0.28 – 0.96) and maternal age 14 to 17 years compared with 25 to 34 years (OR: 4.1; 95% CI: 1.4 –11.9).

DISCUSSION

This study documents the prevalence of various sleeping positions from 1 to 6 months after hospital discharge in a large and diverse cohort of low birth weight infants in the United States. An understand-ing of the sleep positions of low birth weight infants is particularly important considering the very high risk for SIDS associated with prone sleep in these infants.9

Overall, the sleeping position of these low birth weight infants is quite similar to that described for non-low birth weight infants, with a preponderance of side sleeping 1 month after hospital discharge and an increasing prevalence of both prone and supine sleeping at 3 and 6 months after hospital discharge as side sleeping becomes less common.19 A striking finding of this study, however, is that infants weigh-ing⬍1500 g at birth were substantially more likely to be placed to sleep in the prone position than infants with a birth weight of 1500 to 2499 g. At 1 month after hospital discharge, VLBW infants were placed to sleep in the prone position almost twice as often as infants of birth weight 1500 –2499 g (25.7% vs 13.6%).

Because VLBW infants are at an especially high risk for SIDS (3– 4 times the risk of non-low birth weight infants in recent US studies), their propensity for prone sleeping may contribute to significant mortal-ity.7,8

Analysis of the trends in sleeping position 1 month after hospital discharge between 1995 and 1998 shows that the prevalence of both prone and side sleeping decreased while supine sleeping increased substantially. Notably, the decline in prone sleep over time was most dramatic in VLBW infants. These trends may reflect the impact of the “Back to Sleep” campaign, as well as the 1996 AAP statement on positioning and SIDS which recommended supine sleep as the preferred position for term and preterm infants alike.12

As prone sleeping declined over time among the VLBW infants, there was a corresponding increase in side sleeping with no change in supine sleeping. In contrast, for infants weighing 1500 to 2499 g at birth, the decline in prone sleeping over time was accom-panied by a larger increase in supine sleeping and a decline in side sleeping. Thus, as of 1997–1998, while caregivers of low birth weight infants were generally moving away from the prone sleeping position, those caring for VLBW infants were reluctant to em-brace the supine position.

In terms of influences on the choice of sleeping position, mothers who placed their infants in non-prone positions most frequently mentioned physi-cians and other medical professionals as the most important influence. Among those who placed their infants prone, the infant’s preference was cited most commonly, suggesting that many mothers perceive the prone position as the most comfortable for their infants. However, it is also notable that mothers of prone-sleeping VLBW infants mentioned the recom-mendation of a physician or other medical profes-sional 28.6% of the time and following the practices of the nursery 10.7% of the time, compared with only 11.9% and 7.1%, respectively, among prone sleeping infants with higher birth weight. One explanation for

TABLE 2. Primary Influence on Infant Sleep Position 1 Month After Hospital Discharge Stratified by Sleep Position and Birth Weight Category

Birth weight⬍1500 g

Prone sleepersN⫽28 No. (%) Non-prone sleepersN⫽83 No. (%) Infant’s preference 9 (32.1) Physician or other medical professional 39 (50.0) Physician or other medical professional 8 (28.6) Followed nursery practice 12 (14.5)

Previous children 4 (14.3) Family/friends 7 (8.4)

Followed nursery practice 3 (10.7) Infant’s preference 7 (8.4)

Family/friends 1 (3.6) Previous children 6 (7.2)

Educational materials 0 (0.0) Educational materials 5 (6.0)

Other 3 (10.7) Other 6 (7.2)

Birth weight 1500–2499 g

Prone sleepersN⫽84 No. (%) Non-prone sleepersN⫽526 No. (%) Infant’s preference 18 (21.4) Physician or other medical professional 247 (47.0) Previous children 18 (21.4) Educational materials 108 (20.5) Family/friends 16 (19.0) Followed nursery practice 50 (9.5) Physician or other medical professional 10 (11.9) Previous children 43 (8.2) Followed nursery practice 6 (7.1) Family/friends 37 (7.0) Educational materials 6 (7.1) Infant’s preference 14 (2.7)

this disparity is that VLBW infants suffer from a higher prevalence of certain medical conditions, such as gastrointestinal reflux and upper airway prob-lems, that leads some medical professionals to rec-ommend the prone sleep position. It is also possible that physicians, neonatal intensive care nurses, and other medical professionals remain uncomfortable recommending nonprone sleeping for VLBW infants, despite the AAP’s recommendations and the physi-ologic data that support it.

Among infant characteristics, birth weight⬍1500 g was a strong predictor of prone sleep one month after hospital discharge. Several maternal character-istics were also associated with prone sleep including black race, single motherhood, and multiparity, all with a two- to threefold higher risk. Maternal age

⬍18 years old was associated with a similar, al-though not statistically significant, increase in the risk of prone sleep. These maternal risk factors for prone sleep are consistent with those previously identified in non-low birth weight infants.10,19

In analyzing the risk factors for prone sleep among low birth weight infants, we chose to focus on the data collected 1 month after hospital discharge. This time point best represents the time of transition from hospital to home care for these infants and also the point at which interventions may have been imple-mented. When we examined risk factors for prone sleep at 3 months after hospital discharge, by far the greatest predictor was prone sleep at 1 month after hospital discharge, suggesting that once a sleep po-sition is established for a given low birth weight infant, that choice dwarfs the influence of any other infant or maternal characteristic in determining fu-ture sleep position.

The present analysis provides the first detailed evaluation to date of sleep position among low birth weight infants, and it is strengthened by the rela-tively large size of the cohort and its diversity. There are several limitations, however. Subjects were en-rolled only in Massachusetts and Ohio and infant sleep patterns may vary in other parts of the country. The Hispanic participants in the study were mainly of Puerto Rican and Dominican origin, with few Mexican Americans, and the representation of Asian Americans in the cohort was small. Response rates to the survey were good (82.0%, 79.4%, and 76.0% at 1, 3, and 6 months, respectively), but loss to follow-up was proportionately greater among minorities, sin-gle women, and those with lower income and less education.

Overall, these data demonstrate that although the prevalence of prone sleeping among low birth weight infants declined from 1995 through 1998, VLBW infants, who are at the highest risk for SIDS, were the most likely to sleep prone. Furthermore, the decline in prone sleeping among VLBW infants over this time period was accompanied by an increase in side sleeping, not supine sleeping. It also seems from these data that physicians and nurses caring for VLBW infants frequently recommend the prone sleeping position. Additional research that quantifies the cumulative risks and benefits—in terms of SIDS as well as aspiration, airway obstruction, apnea, and other medical problems— of various sleep positions among low birth weight (especially VLBW) infants may be needed to help physicians and other medical personnel to make evidence-based recommendations for these at-risk infants.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by contract N01-HD-4 –3221 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, National Institutes of Health, Rockville, Maryland.

We thank Sandra Hatfield, Dottie Powers, and Debra Zagaeski for research assistance and Maria Francescon, MPH, Patricia Brousseau, Chris DeArmond, Cynthia Nagle, Grace Adeya, and Heather Wightman for recruiting subjects and conducting inter-views. We are indebted to the physicians and nurses at the fol-lowing hospitals: Boston Medical Center and Beth Israel Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts; Lowell General Hospital, Lowell, Massa-chusetts; Lawrence General Hospital, Lawrence, MassaMassa-chusetts; and St Vincent’s Medical Center and Toledo Hospital, Toledo, Ohio.

TABLE 3. Analysis of Risk Factors for Prone Sleep 1 Month After Hospital Discharge Among 744 Low Birth Weight Infants

Risk factor Adjusted OR* (95% CI)

Infant’s sex

Female 1.0†

Male 1.3 (0.82–2.0)

Infant’s birth weight (g)

Less than 1500 2.4 (1.3–4.3) 1500–1999 1.4 (0.79–2.5)

2000–2499 1.0†

Mother’s race/ethnicity

White, Non-Hispanic 1.0† Black, Non-Hispanic 2.6 (1.5–4.5) Hispanic 1.9 (0.97–3.9)

Other 0.13 (0.02–1.0)

Mother’s age in y

14–17 2.8 (0.97–8.1)

18–24 1.5 (0.79–2.8)

25–34 1.0†

35 or older 1.1 (0.54–2.1)

Unknown 1.9 (0.74–4.7)

Mother’s education

Less than high school 0.67 (0.25–1.8) High school graduate 1.0 (0.44–2.3) Some college 1.8 (0.84–3.8) College graduate 1.0† Mother’s marital status

Married 1.0†

Single 3.0 (1.5–6.2)

Unknown 3.4 (0.84–13.8) Mother’s parity

Primiparous 1.0†

Multiparous 2.1 (1.2–3.5) Annual household income

Less than $16 000 2.0 (0.76–5.0) $16 000–34 999 2.4 (0.98–5.7) $35 000–54 999 1.9 (0.82–4.5) $55 000 or more 1.0† Year of enrollment

1995 1.0†

1996 0.76 (0.41–1.4)

1997 0.53 (0.27–1.0)

1998 0.54 (0.27–1.1)

* Adjusted for all covariates shown plus postconceptional age at hospital discharge (tertiles), site of enrollment, and singleton ver-sus multiple birth.

REFERENCES

1. Hoyert DL, Freedman MA, Strobino DM, Guyer B. Annual summary of vital statistics: 2000.Pediatrics.2001;108:1241–1255

2. Black L, David RJ, Brouillette RT, Hunt CE. Effects of birth weight and ethnicity on incidence of sudden infant death syndrome. J Pediatr. 1986;108:209 –214

3. Grether JK, Schulman J. Sudden infant death syndrome and birth weight.J Pediatr.1989;114:561–567

4. McGlashan ND. Sudden infant deaths in Tasmania, 1980 –1986: a seven year prospective study.Soc Sci Med.1989;29:1015–1026

5. Adams MM, Rhodes PH, McCarthy BJ. Are race and length of gestation related to age at sudden death in the sudden infant death syndrome? Pediatr Perinat Epidemiol.1990;4:325–339

6. Mitchell EA, Scragg R, Stewart AW, et al. Results from the first year of the New Zealand cot death study.N Z Med J.1991;104:71–76 7. Malloy MH, Hoffman HJ. Prematurity, sudden infants death syndrome,

and age of death.Pediatrics.1995;96:464 – 471

8. Malloy MH, Freeman DH. Birth weight- and gestation age-specific sudden infant death syndrome mortality: United States, 1991 versus 1995.Pediatrics.2000;105:1227–1231

9. Oyen N, Markestad T, Skaerven R, et al. Combined effects of sleeping position and prenatal risk factors in sudden infant death syndrome: the Nordic Epidemiological SIDS Study.Pediatrics.1997;100:613– 621 10. Willinger M, Hoffman HJ, Wu K, et al. Factors associated with the

transition to nonprone sleep positions of infants in the United States: the National Infants Sleep Position Study.JAMA.1998;280:329 –335

11. American Academy of Pediatrics, Task Force on Infant Positioning and SIDS. Positioning and SIDS.Pediatrics.1992;89:1120 –1126

12. American Academy of Pediatrics, Task Force on Infant Positioning and SIDS. Positioning and sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS): update. Pediatrics.1996;98:1216 –1218

13. American Academy of Pediatrics, Task Force on Infant Positioning and SIDS. Positioning and sudden infant death syndrome: changing con-cepts of sudden infant death syndrome: implications for infant sleeping environment and sleep position.Pediatrics.2000;105:650 – 656 14. Goto K, Mimiran M, Adams MM, et al. More awakenings and heart rate

variability during supine sleep in preterm infants.Pediatrics.1999;103: 603– 609

15. Keene DJ, Wimmer JE, Matthew OP. Does supine positioning increase apnea, bradycardia, and desaturation in preterm infants?J Perinatol. 2000;20:17–20

16. Sahni R, Schulze KF, Kashyap S, Ohira-Kist K, Fifer WP, Myers MM. Postural differences in cardiac dynamics during quiet and active sleep in low birthweight infants.Acta Paediatr.1999;88:1396 –1401

17. Sahni R, Schulze KF, Kashyap S, Ohira-Kist K, Myers MM, Fifer WP. Body position, sleep states, and cardiorespiratory activity in low birth-weight infants.Early Hum Dev.1999;54:197–206

18. Harper RM, Kinney, Fleming PJ, Thach BT. Sleep influences on homeo-static functions: implications for sudden infant death syndrome.Respir Physiol.2000;119:123–132

19. Lesko SM, Corwin MJ, Vezina RM, et al. Changes in sleep position during infancy.JAMA.1998;280:336 –340

TELEVISION ENDORSES OUR PREJUDICES

“. . . Everyone acknowledges that news program can be stage-managed. What is bad news for the human being in the street is often good news for television, for the individual is always outnumbered by the audience and it is the requirement of spectators rather than participants that wins currency. It is not that we, the viewers, support the bad guys against the good. Nor is it that television, in any obvious sense, is a Great Persuader. It is merely a blank check. Whatever we see tends to endorse our prejudices, helps to grow a cuticle of insensitivity, and pays us dividends in virtuous indignation.”

Holroyd M. Works on paper.Counterpoint. 2002

DOI: 10.1542/peds.111.3.633

2003;111;633

Pediatrics

Hunt, Howard J. Hoffman, Marian Willinger and Allen A. Mitchell

Louis Vernacchio, Michael J. Corwin, Samuel M. Lesko, Richard M. Vezina, Carl E.

Sleep Position of Low Birth Weight Infants

Services

Updated Information &

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/111/3/633

including high resolution figures, can be found at:

References

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/111/3/633#BIBL

This article cites 19 articles, 8 of which you can access for free at:

Subspecialty Collections

sub

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/fetus:newborn_infant_ Fetus/Newborn Infant

following collection(s):

This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

Permissions & Licensing

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml

in its entirety can be found online at:

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

Reprints

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml

DOI: 10.1542/peds.111.3.633

2003;111;633

Pediatrics

Hunt, Howard J. Hoffman, Marian Willinger and Allen A. Mitchell

Louis Vernacchio, Michael J. Corwin, Samuel M. Lesko, Richard M. Vezina, Carl E.

Sleep Position of Low Birth Weight Infants

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/111/3/633

located on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 1073-0397.