Children

’

s Experiences of Cystic Fibrosis: A Systematic

Review of Qualitative Studies

abstract

BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVE:Cysticfibrosis (CF) is a common

life-shortening genetic disease and is associated with poor psychosocial and quality of life outcomes. The objective of this study was to describe the experiences and perspectives of children and adolescents with CF to direct care toward areas that patients regard as important.

METHODS:MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, and Cumulative Index to

Nurs-ing and Allied Health Literature were searched from inception to April 2013. We used thematic synthesis to analyze thefindings.

RESULTS:Forty-three articles involving 729 participants aged from 4 to 21

years across 10 countries were included. We identified 6 themes: gaining resilience (accelerated maturity and taking responsibility, acceptance of prognosis, regaining control, redefining normality, social support), lifestyle restriction (limited independence, social isolation, falling behind, physical incapacity), resentment of chronic treatment (disempowerment in health management, unrelenting and exhausting therapy, inescapable illness), temporal limitations (taking risks, setting achievable goals, valuing time), emotional vulnerability (being a burden, heightened self-consciousness,financial strain, losing ground, overwhelmed by transition), and transplant expectations and uncertainty (confirmation of disease severity, consequential timeliness, hope and optimism).

CONCLUSIONS:Adolescents and children with CF report a sense of

vul-nerability, loss of independence and opportunities, isolation, and dis-empowerment. This reinforces the importance of the current model of multidisciplinary patient-centered care that promotes shared decision-making, control and self-efficacy in treatment management, educational and vocational opportunities, and physical and social functioning, which can lead to optimal treatment, health, and quality of life outcomes.Pediatrics2014;133:e1683–e1697

AUTHORS:Nathan Jamieson,aDominic Fitzgerald, PhD,b,c

Davinder Singh-Grewal, PhD,b,cCamilla S. Hanson, B Psych

(Hons),a,dJonathan C. Craig, PhD,a,dand Allison Tong, PhDa,d

aKids Research Institute,bRespiratory Medicine, andcPaediatrics

& Child Health, Children’s Hospital at Westmead, Westmead, NSW, Australia; anddSchool of Public Health, The University of Sydney,

Sydney, NSW, Australia

KEY WORDS

cysticfibrosis, qualitative research, pediatrics, adolescent, systematic review

ABBREVIATIONS

CF—cysticfibrosis

CINAHL—Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature Mr Nathan Jamieson carried out the data collection and analyses, coded the data, and drafted the initial manuscript; Dr Fitzgerald, Dr Singh-Grewal, Ms Hanson, and Dr Craig contributed to the initial analyses and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Dr Tong conceptualized and designed the study and drafted the initial manuscript; and all authors approved thefinal manuscript as submitted.

www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2014-0009 doi:10.1542/peds.2014-0009

Accepted for publication Mar 10, 2014

Address correspondence to Allison Tong, PhD, Centre for Kidney Research, The Children’s Hospital at Westmead, Westmead, NSW 2145. E-mail: allison.tong@sydney.edu.au

PEDIATRICS (ISSN Numbers: Print, 0031-4005; Online, 1098-4275). Copyright © 2014 by the American Academy of Pediatrics

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE:The authors have indicated they have nofinancial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING:No external funding. Dr Tong is supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council Fellowship (1037162).

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a common life-shortening inherited disease with an estimated incidence of 1 in 2500 new-borns.1–4Most patients with CF develop

chronic pulmonary disease and bron-chiectasis, as well as pancreatic insuf-ficiency and subsequent malnutrition.5–7

Because of advances in screening, treatment, and infection control, patients diagnosed with CF within the past decade are now expected to survive into their 50s.8,9However, treatment of CF involves

daily adherence to intensive antibiotic regimens, vitamin and enzyme supple-ments, consumption of a calorie-rich diet, inhaler use, and physically de-manding chest physiotherapy. Limited daily functioning, poor adherence to treatment, low self-esteem, short stat-ure, and impaired psychosocial out-comes have been reported.10–15

What remains less well known is how young patients cope with the symptoms, prognostic uncertainty, and treatment burden of CF. In-depth insights into people’s beliefs and attitudes can be gained by qualitative research, and synthesis of multiple qualitative studies can provide a broader scope of data across different health care contexts and generate new and more compre-hensive understandings of social phe-nomena.16 We aimed to describe the

breadth of experiences and per-spectives of children and adolescents with CF, to inform ways to deliver patient-centered care for optimal treat-ment, health, and quality of life out-comes, and to direct care toward areas that patients regard as important.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We followed the Enhancing Trans-parency of Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative research framework.16

Selection Criteria

Qualitative studies that explored the experiences and perspectives of chil-dren and adolescents (#21 years of

age) diagnosed with CF were included. We excluded observational studies, randomized controlled trials, genetic and microbiological studies, non–primary re-search articles (letters, commentaries, and reviews), studies that did not elicit data from children and adolescents with CF, quantitative surveys, and non-English articles due to lack of resources for translation.

Data Sources and Searches

The search strategy is provided in Supplemental Table 3. We conducted searches in Medline, Embase, PsycINFO, and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Al-lied Health Literature (CINAHL) from in-ception to April 2013. We also searched Google Scholar and the reference lists of relevant studies and reviews. We screened the abstracts and excluded those that that did not meet the inclusion criteria, then assessed the full-text ver-sions of potentially relevant studies.

Comprehensiveness of Reporting

We evaluated the transparency of re-porting of each qualitative study using the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Health Research.17 This

framework included criteria specific to the research team, study methods, context of the study, analysis, and interpretations. Two reviewers (N.J. and C.H.) assessed each study indepen-dently, and disagreements were re-solved by discussion with A.T.

Data Analysis

We used thematic synthesis as described by Thomas and Harden.18For each study,

all participant quotations and text under the “Results/Findings” or “Conclusion/ Discussion”sections were extracted and entered verbatim into HyperRESEARCH (version 3.5.2; ResearchWare, Inc, Randolph, MA), software for storing, cod-ing, and searching qualitative data. N.J. conducted line-by-line coding of the text into concepts inductively derived from the

data and transferred concepts between studies by adding coded text into existing concepts or creating additional codes for new concepts. Similar codes were grouped into themes. The preliminary themes were discussed in a research team meeting to ensure that the themes reflected the full range of experiences reported across all studies. Patterns and relationships within and across themes were examined and mind mapped to develop an analytical thematic schema.

RESULTS

Literature Search

Our search yielded 1862 articles. Of these, 43 articles involving at least 729 children with CF were included (Fig 1). The number of participants was not reported in 7 studies (Table 1).

Comprehensiveness of Reporting

Studies reported between 7 and 20 of the 24 Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Health Research (Supple-mental Table 4). Fifteen studies (35%) described the participant selection strategy. Twenty-eight studies (65%) reported researcher triangulation, and 15 (35%) reported on theoretical satu-ration, defined as a lack of new concepts found after subsequent data collection. Member checking (seeking feedback on the researchfindings from participants) was reported in 2 (5%) studies.

Synthesis

We identified 6 main themes: gaining resilience, lifestyle restriction, resent-ment of chronic treatresent-ment, temporal limitations, emotional vulnerability, and transplant expectations and uncertainty. Selected participant quotations that conveyed the meaning of the theme were chosen from the included the studies and integrated as examples in the results. Additional illustrative quotations are presented in Table 2.

with CF experienced emotional vulner-ability and at the same time expressed capacities to gain resilience in coping with their illness. Heightened self-consciousness due to manifestations of CF contributed to participants’sense of vulnerability. The chronic treatment burden imposed restrictions on life-style and independence, which in-tensified participants’ resentment of their illness. Regaining control con-tributed to the development of resil-ience but also reinforced risk-taking attitudes and decisions, particularly in adolescents who sought to demon-strate independence and ability to make their own choices. The need to value time and reprioritize was driven by an acute awareness and realization of their disease severity.

Gaining Resilience

Accelerated Maturity and Taking Responsibility

Participants felt that they were more mature and compassionate compared with their well peers. Having faced the challenges of living with CF, some be-lieved they gained coping skills, resil-ience, and appreciation of life and were less concerned about trivial matters. One adolescent stated, “I feel that having CF has pushed me into adult-hood...in a good way.”19They

empha-sized the importance of a positive attitude in staying motivated to take their medications. Signs and symp-toms such as hemoptysis encouraged some participants to be more health conscious.

Acceptance of Prognosis

Some participants described having to accept the reality of their incurable condition and shortened life expectancy to live an “enjoyable life.”20 Although

they could not be optimistic about their survival, some believed in the need to maintain a positive attitude and to“be happy and make the most of it.”21

Regaining Control

Invasive medical procedures caused some participants to feel a loss of control of their own body. One participant ex-plained,“If you have a [IV] line, the con-trol is with the other people.”22However,

strategies such as needle plans and play therapy helped alleviate their anxieties as participants felt that they had reclaimed control. Also, participants FIGURE 1

TABLE 1 Char acteristics of Included Studies Study ID P atients (n) Sex (M:F) Age Range (y) Con ceptual Me thodolog ical Fr amewo rk Data Col lection (Qu alitative ) Ana lysis Resear ch Topic and Scope Aus tr alia Brum fi eld 20 04 77 3 2:1 19 – 20 Qualit ative desig n Unstru ctur ed face -to-face interviews Themat ic ana lysis Tr ansit ion to adu lt health car e se rvices Fer eda y 20 09 56 5N S 4 – 16 Interp retive phe nomenolo gy Foc us gr oups Themat ic ana lysis Physical ac tivity Gr aetz 2000 78 35 17 :18 11 – 18 NS Struc tur ed fa ce-to-f ace intervi ews and que stionnai res NS Suppor t fr om fa mily and fri ends Rus sell 1996 79 7 2:5 11 – 20 Roy adapt ation model Semis tructur ed fa ce-to-face intervi ews Adapt ive categor ization Tr ansit ion to adu lt health services Willi s 2001 36 40 19 :21 16 – 20 NS Semis tructur ed fa ce-to-face intervi ews Themat ic ana lysis Gende r differ ences Br

azil Piz

zign a cco 2006 80 8N S 7 – 18 Qualit ative desig n Semis tructur ed fa ce-to-face intervi ews Themat ic ana lysis Daily routine Can

ada Eller

believed that the ability to manage their own health and to participate in physical and recreational activities meant that CF had not defeated or limited them. They derived a sense of normality,“mastery,” and “competence” from taking control over their health, with 1 girl describing physical activity as her“sanctuary.”23

Redefining Normality

Over time, some believed that they be-came less concerned about the differ-ences in their physical appearance and capabilities compared with their healthy peers. One participant described that he had “nothing to hide and nothing to advertise.”24 By meeting other young

people with CF, some learned to respect and accept their own physical capaci-ties rather than compare themselves with their well peers. Younger children reported a loss of having a normal identity at the time of diagnosis:“I just thought she must be insane...because I always thought I was just like everybody else.”25

Social Support

Emotional and practical support from carers, friends, and family was described as a resource that enabled participants to cope with their day-to-day disease management. Having a shared experi-ence and interacting with other patients with CF promoted social connectedness and sharing of coping strategies and information. Children and adolescents, particularly girls, reported that they depended on their parents to encourage adherence to medications and therapy. One participant believed that the loss of accountability to their parents after moving out of home contributed to the onset of depression.

Lifestyle Restriction

Falling Behind

The participants felt socially“out of the loop”26 and out of place because of

frequent absences from school and

extracurricular activities, mainly due to pulmonary exacerbations and lung deterioration. Some felt they lacked capacity and support to perform aca-demically. For example, 1 adolescent described having to leave school being unable to achieve second grade literacy.

Limited Independence

Most participants felt their lives were marked by a loss of freedom and op-portunities because of their poor health and time-consuming treatments. Some described their parents as interfering, domineering, and overprotective. They felt exasperated and patronized by constant reminders from parents about taking medications; however, some felt that these reminders were essential“or else [they] won’t do it.”27 Others felt

that they should be given more re-sponsibility as they got older,28and 1

participant suggested they should be given a trial period to prove they could independently manage their illness.29

To avoid having additional restrictions imposed, some refrained from asking for advice from their doctors about high-risk activities such as drinking alcohol, which led to high-risk behav-iors including defiance29 and hiding

problems with adherence: “I’ll not do [physical therapy] just to spite them.”27 Being highly dependent on

care, some older participants stated that their career and education options were limited to those that were located in close proximity to their home or CF clinic.

Physical Incapacity

Short stature, weakness, fatigue, and susceptibility to infections contributed to participants’frustration, social iso-lation, and feelings of being different. They had“to try twice as hard...to do as good as the other kids”30 and found

that physical exertion took a toll on their health and energy. Children felt upset about being too tired to play. Adolescents, particularly boys, were

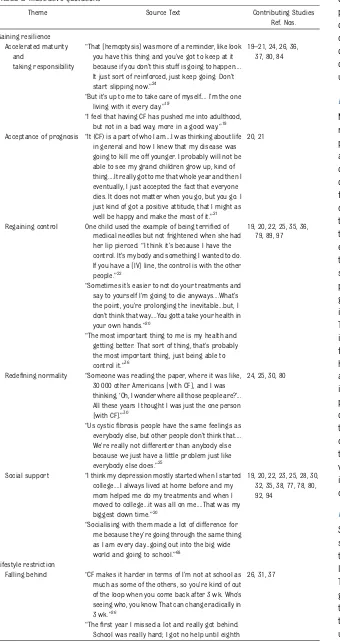

TABLE 2 Illustrative Quotations

Theme Source Text Contributing Studies Ref. Nos. Gaining resilience

Accelerated maturity and

taking responsibility

“That [hemoptysis] was more of a reminder, like look you have this thing and you’ve got to keep at it because if you don’t this stuff is going to happen.... It just sort of reinforced, just keep going. Don’t start slipping now.”24

19–21, 24, 26, 36, 37, 80, 84

“But it’s up to me to take care of myself.... I’m the one living with it every day.”19

“I feel that having CF has pushed me into adulthood, but not in a bad way, more in a good way.”19 Acceptance of prognosis “It (CF) is a part of who I am....I was thinking about life

in general and how I knew that my disease was going to kill me off younger. I probably will not be able to see my grand children grow up, kind of thing....It really got to me that whole year and then I eventually, I just accepted the fact that everyone dies. It does not matter when you go, but you go. I just kind of got a positive attitude, that I might as well be happy and make the most of it.”21

20, 21

Regaining control One child used the example of being terrified of medical needles but not frightened when she had her lip pierced.“I think it’s because I have the control. It’s my body and something I wanted to do. If you have a [IV] line, the control is with the other people.”22

19, 20, 22, 25, 35, 36, 79, 89, 97

“Sometimes it’s easier to not do your treatments and say to yourself I’m going to die anyways....What’s the point, you’re prolonging the inevitable...but, I don’t think that way....You gotta take your health in your own hands.”20

“The most important thing to me is my health and getting better. That sort of thing, that’s probably the most important thing, just being able to control it.”36

Redefining normality “Someone was reading the paper, where it was like, 30 000 other Americans [with CF], and I was thinking,‘Oh, I wonder where all those people are?’... All these years I thought I was just the one person [with CF].”30

24, 25, 30, 80

“Us cysticfibrosis people have the same feelings as everybody else, but other people don’t think that.... We’re really not differenter than anybody else because we just have a little problem just like everybody else does.”25

Social support “I think my depression mostly started when I started college....I always lived at home before and my mom helped me do my treatments and when I moved to college...it was all on me....That was my biggest down time.”20

19, 20, 22, 23, 25, 28, 30, 32, 35, 38, 77, 78, 80, 92, 94

“Socialising with them made a lot of difference for me because they’re going through the same thing as I am every day...going out into the big wide world and going to school.”68

Lifestyle restriction

Falling behind “CF makes it harder in terms of I’m not at school as much as some of the others, so you’re kind of out of the loop when you come back after 3 wk. Who’s seeing who, you know. That can change radically in 3 wk.”26

26, 31, 37

concerned about being unable to ach-ieve their ideal masculine physique.

Social Isolation

Participants felt ostracized when oth-ers avoided them because of their coughing or differences in their physi-cal appearance, such as finger club-bing. Frequent absences from school also made it harder to establish friendships, because participants “never got to know people as well.”26

Children described being bullied or abandoned by others who thought CF was contagious: “All the kids saying ‘eww’...then they would say‘Oh shut up AIDS girl.’”30Some felt that others

ac-cused them of using CF as an excuse to avoid school. CF was also believed to “jeopardize” romantic relationships, with 1 participant reporting that her past boyfriend“split”31when he found

out she had CF. Having to avoid“ high-risk”environments and being isolated from other patients in wards, partic-ipants felt socially excluded and expressed“boredom.”32

Resentment of Chronic Treatment

Inescapable Illness

Participants wanted “escape” or a “break”from their illness. However, the relentless need to take medications and undergo physical therapy served as constant reminders of their incurable illness. One participant stated that“it drives the nail home that you do have lung disease,”23and another was “

un-bearably depressed”33 about how the

treatment reminded her of her illness. Some saw treatment as another in-dication of being different or weaker than their well peers.

Disempowerment in Health Management

Some participants felt that doctors used only “high level talk”31 and complex

medical terminology. When they perceived their doctors were communicating solely

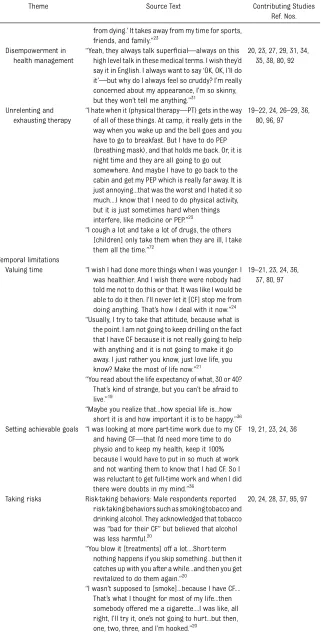

TABLE 2 Continued

Theme Source Text Contributing Studies Ref. Nos. grade so I dropped out. The next year they told me I

could graduate. Well, I got mad and my mom agreed. I couldn’t read at a second grade level, do math, or write. So I went to a special school and learned more there than ever before. School has always been a pain in the neck. I never did like it.”31 Limited independence Alternatively, some participants revealed that

a reason for not asking their doctor questions (eg, drinking alcohol, taking part in risky activities such as extreme fairground rides) was because they might not want to hear about restrictions to their lifestyle.78

19, 21, 27–29, 32, 36, 37, 80, 92, 97

“I don’t think I could have gone to a school far away because I had to be close to the CF Center and my parents in case I got sick.”19

Older children with more severe symptoms who were independently performing their own physiotherapy techniques also felt it was too much hassle to stay away from home because of the amount of medication and equipment they needed and because they felt emotionally uncomfortable (embarrassed) about doing their physiotherapy away from home.83

Physical incapacity “It just started to get harder like to do sports and baseball and cheerleading. I’d start getting more short of breath and tired and coughing.”26

19, 23, 26, 30, 32, 34, 36, 38, 89, 91, 96

“We play a game called‘Capture’in our

neighborhood....I can’t play that too much in a row, or I really don’t feel good the next day.”

“I don’t do the activities I used to do because I get too out of breath....I would love to be able to run again, I get too out of breath and I used to love to run.... Now I get in a coughing spell and I can’t breathe.”76

Social isolation When friends asked one participant about his“big

fingers”(clubbing), he told them,“It was because my Dad had really bigfingers. I remember getting a really big sinking feeling in my stomach like,‘My gosh somebody noticed something different/ weird about me.’I felt like I was different. I resented....I didn’t like myfingers, you know. I didn’t want them to be that way. I wanted them to be like everybody else’sfingers.”26

19, 26, 27, 30–32, 95

“I have to be real careful when I tell my boyfriend I have CF. In all times past, once they’ve found out, they’ve split.”31

Resentment of chronic treatment

Inescapable illness The treatments that became part of their routine served as a constant reminder that they had CF, and only in this sense did they feel different from others.24

20, 21, 23–25, 30, 33, 80, 93, 97

to their parents, participants felt ignored and devalued. They wanted clinicians to listen to their needs rather than “just clinically going through [the illness and treatment],”34and they believed doctors

should communicate directly with them. Some participants appreciated nurses who“treat you like you are part of their family.”35

Unrelenting and Exhausting Therapy

Treatment of CF, particularly medications, physical therapy, and lung clearance, was described as intensive, invasive, and physically strenuous. Children were frightened of the pain of injections, and they experienced fatigue due to pre-scribed physical exercise. Despite the physical demands of treatment, some adolescents believed that persevering with therapy was necessary to prevent health deterioration and lung infections. One participant said,“I’m justfighting to get rid of something for a certain amount of time.... It’s a never-ending battle.”26

Temporal Limitations

Valuing Time

Being acutely aware of their“shadowy future”21and shortened life expectancy,

some participants chose to “make the most out of life now”21rather than waste

time worrying about the future. Some were concerned that they had wasted their time so far (“I just sometimes feel I haven’t done much with my life”36) and

despaired at how their physical therapy “robbed”23them of their precious time.

Participants chose to spend as much time as possible with family and friends.

Setting Achievable Goals

Some participants accounted for the health and lifestyle limitations caused by CF when they set career and relation-ships goals, and they needed to consider air quality and associated workplace risks, employment benefits and health insurance, and the availability offlexible hours or part-time work. They also

TABLE 2 Continued

Theme Source Text Contributing Studies Ref. Nos. from dying.’It takes away from my time for sports,

friends, and family.”23 Disempowerment in

health management

“Yeah, they always talk superficial—always on this high level talk in these medical terms. I wish they’d say it in English. I always want to say‘OK, OK, I’ll do it’—but why do I always feel so cruddy? I’m really concerned about my appearance, I’m so skinny, but they won’t tell me anything.”31

20, 23, 27, 29, 31, 34, 35, 38, 80, 92

Unrelenting and exhausting therapy

“I hate when it (physical therapy—PT) gets in the way of all of these things. At camp, it really gets in the way when you wake up and the bell goes and you have to go to breakfast. But I have to do PEP (breathing mask), and that holds me back. Or, it is night time and they are all going to go out somewhere. And maybe I have to go back to the cabin and get my PEP which is really far away. It is just annoying...that was the worst and I hated it so much....I know that I need to do physical activity, but it is just sometimes hard when things interfere, like medicine or PEP.”23

19–22, 24, 26–29, 36, 80, 96, 97

“I cough a lot and take a lot of drugs, the others [children] only take them when they are ill, I take them all the time.”72

Temporal limitations

Valuing time “I wish I had done more things when I was younger. I was healthier. And I wish there were nobody had told me not to do this or that. It was like I would be able to do it then. I’ll never let it [CF] stop me from doing anything. That’s how I deal with it now.”24

19–21, 23, 24, 36, 37, 80, 97

“Usually, I try to take that attitude, because what is the point. I am not going to keep drilling on the fact that I have CF because it is not really going to help with anything and it is not going to make it go away. I just rather you know, just love life, you know? Make the most of life now.”21

“You read about the life expectancy of what, 30 or 40? That’s kind of strange, but you can’t be afraid to live.”19

“Maybe you realize that...how special life is...how short it is and how important it is to be happy.”36 Setting achievable goals “I was looking at more part-time work due to my CF

and having CF—that I’d need more time to do physio and to keep my health, keep it 100% because I would have to put in so much at work and not wanting them to know that I had CF. So I was reluctant to get full-time work and when I did there were doubts in my mind.”36

19, 21, 23, 24, 36

Taking risks Risk-taking behaviors: Male respondents reported risk-taking behaviors such as smoking tobacco and drinking alcohol. They acknowledged that tobacco was“bad for their CF”but believed that alcohol was less harmful.20

20, 24, 28, 37, 95, 97

“You blow it [treatments] off a lot....Short-term nothing happens if you skip something...but then it catches up with you after a while...and then you get revitalized to do them again.”20

developed alternative strategies if they could not pursue their initial vocational goals. In particular, boys expressed op-timism and refused to allow their con-dition to define their career goals. Conversely, some adolescent girls felt insecure about their future career pathway and doubted their opportuni-ties for full-time employment.

Taking Risks

Some adolescents wanted to take risks because they felt they had nothing to lose in their limited time. They described taking drugs, drinking alcohol, smoking, and“blow[ing] off treatment,”20choices

that allowed them to show CF had not restricted their lifestyle. Some acknowl-edged that certain environments would expose them to infection risk but be-lieved that complete avoidance “could take it too far” and lead to “missing out.”32 For some, the consequences of

poor health after smoking or refusing treatment and therapy“caught up”with them, and in turn they became motivated to continue with their treatments.

Emotional Vulnerability

Being a Burden

Some participants deemed themselves highly dependent on family members for day-to-day medical treatment. For this reason, they felt guilty for taking parental attention away from their siblings and for depriving their families of vacation time because of their ill health. One participant believed that her parents’ arguments about her CF care caused their marital problems.

Financial Strain

In a study conducted in the United States, adolescents were anxious about thefinancial burden of their disease, including insurance, medications, and costs of nutrient-dense foods. A major concern was negotiating with insur-ance companies to cover the costs of equipment and medications.

TABLE 2 Continued

Theme Source Text Contributing Studies Ref. Nos. These risk-taking behaviors demonstrated the

conflict between the adolescent’s cognitive ability to make rational decisions and his developmental needs for independence and control.30 Where infection risk was not apparently considered,

social factors were often cited as a reason for the decision.“At the end of the day you cannot sort of shut yourself away....I think it’s really important to think about infection, but I think some people could take it too far.”95

Transplant expectations and uncertainty Confirmed severity

of disease

“Being listed [for transplant] signified a point in the chronic illness trajectory at which there was no longer any advantage in delaying the transplant procedure.”37

37, 38

“The introduction of discussions regarding referral for transplant displaces this status quo of‘normal life’. . . while considering that transplant may be something that will be required in the future, are not usually prepared for the conversation when it is raised, despite being given cues from health professionals indicating a deteriorating picture over time.”38

“I was shocked that he had even thought, how dare they say I was as bad, that I have only got so long to live or something like that.”38

“I was angry, I thought it was too soon.”38 Consequential

timeliness

“Everyone on the team admits don’t do it until the precise time. It is a very strange balance, you know. You have tofind the exact point at which to get you on the list, because if you go too early, you are sacrificing maybe a year of good health.”38

37, 38

“If I was a video recorder, I’d be on pause at the moment. I’m not really living, I’m just getting by.”38

Hope and optimism “Increased health, that is the obvious benefit. It is hard work after the transplant. The surgery is no fun, it is painful. But the rewards—the possible benefits, you know, I think, far outweigh that.”37

37, 38, 79, 80

“It was an exciting feeling, it was like, God, I’m going on the transplant list, I’m going to be normal like everyone else.”38

Emotional vulnerability

Being a burden “I always got sick when we went on vacations and it... ruined it for the rest of the family....My brother would get really mad at me because we had to cut it short or because it wasn’t as fun as it would have been.”20

20, 26, 94

“My CF has always been an issue between them [parents] because the lastfive years I’ve been in and out of the hospital and...they’ve hadfights over the phone a lot about who should be taking care of me and how stressful it is....It’s been awful.”20

Financial strain “The insurance is the biggest concern. It’s really the only thing with my CF that I worry about. I have learned how to deal with the insurance people.... It’s like you have to reallyfight for yourself....It’s probably the hardest thing I’ve had to deal with.”19

19

Heightened Self-Consciousness

Many participants expressed embarrass-ment about their small physical stature, coughing, and taking medications in public. Feelings of being different were exacerbated by symptoms that pro-hibited them from engaging in social and physical activities. Some participants developed a“private cough and a social cough”30or avoided taking medications

in an effort to appear normal. Being defined as“patients or handicapped”24

and being treated differently by their peers, teachers, and coaches caused

frustration, and participants felt de-meaned. In an effort to appear normal, many participants chose not to tell their friends and teachers about their CF.

Losing Ground

Some participants felt powerless as the illness progressed:“I feel helpless, how I used to be able to do [activities], and now, I can’t.”21Participants were

anx-ious about potentially developing other illnesses that they perceived were as-sociated with CF, including diabetes and depression.

Overwhelmed by Transition

Many participants felt overwhelmed and unprepared for the transition from pediatric to adult care. Some felt that there had been“no real discussion”34

about transition until it had occurred. They had difficulty coping with the un-familiar setting and lack of rapport with new health care workers. One participant was concerned about per-ceived greater exposure to infection in the adult setting. Conversely, some found the transition process beneficial and enjoyed experiencing what they felt was age-appropriate care.

Transplant Expectations and Uncertainty

Confirmation of Disease Severity

Being listed for lung transplantation was alarming for some participants because it signaled that their health had deteriorated to a critical stage. Some believed they were listed too soon be-cause they did not perceive themselves to be seriously ill, and they felt un-prepared and shocked.

Consequential Timeliness

The importance of timing of being waitlisted or receiving a lung transplant at the right time was described by some as being a“very strange balance”having to“find the exact point at which to get you on the list, because if you go too early, you are sacrificing maybe a year of good health.”37The time from being

placed on the transplant list to being transplanted was marked by uncer-tainty, anxiety, disappointing false ala-rms, and the feeling that life was like a “video recorder...on pause. I’m not really living, I’m just getting by.”38Some

felt that more regular contact with the transplant center would reassure them that they had not been forgotten.

Hope and Optimism

Some participants held hope that a transplant would provide them with

TABLE 2 Continued

Theme Source Text Contributing Studies Ref. Nos. and the healthy foods seem to be the most

expensive.”19 Heightened

self-consciousness

Younger children (6–9 y) did not understand that they were born with CF and thought peers avoided them because they were afraid of“catching”CF.25

19, 20, 23–31, 36, 66, 80, 93, 97

Several described developing a private cough and a social cough to minimize their differences and avoid negative social consequences.30

“There was one person in my school who, because we all had a packed lunch, he’d always say‘Oh, druggy!’...He was older than me, and he’d say it,

‘Druggy. Druggy.’He’d shout it out really loud.”79

“When I cough, it sounds like I’m choking. The kids are scared to be around me. I don’t have a lot of friends.”31

Losing ground “Two years ago I was capable of downhill skiing, walking to class without oxygen—running around. Now, I am a lot sicker. I am in the hospital a lot more, which is taking away from both my social life and my academic performance.”37

20, 21, 26, 36, 37, 92

“I also know that I am not going to live as long as everybody else, so that is hard. I feel like it is out of my control, I feel helpless, how I used to be able to do it (physical activity), and now, I can’t. It is kind of depressing. It makes me think that it is a progressive disease, and it makes me think that it is getting worse....It makes me worried.”21 Overwhelmed by

transition

For example, one participant noted the lack of detail:

“Ah, very little, almost nothing. I mean all they do is to tell you that you are transferring.”34

29, 34, 35, 77, 79, 80, 84, 85

But most young adults and especially parents said it had been more stressful and difficult than anticipated. Those who had had frequent contact with pediatric health care providers found it hard to establish trust and familiarity with the new staff, as reflected by metaphors like“being lost,”

better health, greater life expectancy, and the chance to be“normal like ev-eryone else.”Transplant was perceived to offer a chance of good health, with-out “[lungs with] scars and years of infection and damage.”37Others were

optimistic about the potential for fu-ture medical advances to find a cure and improve their health.

DISCUSSION

Children and adolescents with CF have a shortened life expectancy, significant comorbidities, and treatment burdens that impair their identity, daily func-tioning, and life goals. Our study highlights the personally significant ex-periences of children with CF, including their emotional vulnerabilities and their strategies and capacities to develop resilience. Challenges of living with CF include accepting their prognosis, ad-hering to a demanding treatment regi-men, losing independence, transitioning to adult care, limiting social participa-tion, and missing education and career opportunities, which reinforced their sense of abnormality, resentment, and disempowerment. Social support from family, friends, and other patients with CF is valued, and internal coping strat-egies encompass redefining normality, taking responsibility, setting achievable or realistic goals, and holding hope

for lung transplantation and medical advances.

The feeling of being different from others appeared to be more acute in younger children. Some adolescents believed that CF caused them to mature beyond their chronological age, which motivated them to accept their illness and adhere to their prescribed treatment, but others chose to engage in high-risk behaviors to demonstrate that they were not limited by CF. Those with milder diseases were still able to retain a sense of control through participation in physical, school, and social activities. However, patients with more severe CF contended with feelings of powerlessness.

The themes identified in our review may help explain why some children and adolescents with CF report lower quality of life than their well peers.40,41Of note,

girls with CF have reported more emo-tional symptoms and greater pain, spend more time in the hospital than boys with a similar level of illness,41–43 and have

a worse prognosis than boys.44–48 Our

findings suggest that boys may em-phasize taking responsibility for their treatments and maintaining a positive attitude, whereas some girls expressed the value of sharing responsibility for their health management with, for ex-ample, their parent or doctor. Some boys reported body image concerns and were

motivated to exercise to achieve a more muscular physique. Studies have also found that a decrease in lung function predicts a poor health-related quality of life over time.49This is supported by our

findings that many of the psychosocial issues in CF relate to issues of fatigue and physical incapacity.

Children and adolescents living with other chronic and life-limiting illnesses including cancer, juvenile idiopathic ar-thritis, and chronic kidney disease also experience a loss of normality and of control over their bodies because of regular invasive procedures, social isolation, lifestyle restraints, and height-ened self-consciousness about the dif-ferences in their physical appearance compared with their well peers.50–55

Being able to participate in physical ac-tivity is viewed as important in both the CF and asthma populations.56

What may be unique in children and adolescents with CF is how their sus-ceptibility to infections (including cross-infection necessitating segrega-tion32,57,58) limits their lifestyle, reduces

their capacity to participate in physical activity, and perpetuates anxiety, iso-lation, and uncertainty. Also, some felt embarrassed and worried that they would be abandoned by peers who thought their illness was spread by coughing.

FIGURE 2

In our review, we undertook a compre-hensive search and a rigorous indepen-dent assessment of the transparency of study reporting. Researcher triangulation was achieved by involving several re-searchers in the process of analyzing the data, which ensured that the coding framework captured the breadth of data reported in the primary studies. Software was used to code the data, allowing an auditable development of the findings. However, our study has some limitations. Wewereunabletodescribeagedifferences because the majority of the data (quota-tions) from the included studies were not tagged to a specific age or age group. Most studies were conducted in developed countries, and non–English language articles were excluded, making the transferability of ourfindings uncertain.

CF care sets a benchmark in terms of providing comprehensive multidisciplin-ary care in pediatrics.59–61Nonadherence

to treatment remains a significant prob-lem, particularly in the pediatric pop-ulation.62–64Our study suggests that this

may result from self-consciousness and striving to appear normal, engaging in risk-taking behaviors to gain a sense of control and independence, needing to “escape”the illness and exhaustion from the demands of treatment, and a sense of disempowerment. Motivating factors for treatment adherence included deter-mination to maintain health in their hope for transplantation and the desire to take responsibility and demonstrate maturity.

To promote independence, empowerment, and confidence in self-management, which may lead to improved adherence, we suggest shared decision-making pro-cesses where patients are actively in-volved in decisions about their own

treatment and feel in control of their treatment.65,66

There is now a need to better meet the longer-term needs of patients with CF who will live longer, especially their psy-chosocial needs, as described in our re-view. The Home, Education, Activities, Drug and Alcohol Use, Sexuality and Suicide Youth is a validated tool that can be used to assess psychosocial status and health-risk behaviors in adolescents.67 Such

tools may be used to identify patients who will benefit from psychosocial ser-vices,68,69which could be adapted for the

CF population and thereby support clini-cians in promoting psychosocial coping among children with CF.

Transitioning from pediatric to adult health care services remain a challenge,70–73

with some adolescents reporting diffi -culties in coping with pressures of their new health care responsibilities.71 Our

findings suggest the need to individu-alize the transition approach, focusing on the individual’s readiness and expec-tations for transition, which can be fa-cilitated by creating a care plan with the patient and their family.74A collaborative

process through introduction of the adult-style clinic in the pediatric setting has been implemented in CF clinics in the United Kingdom and Australia. Suc-cessful collaboration can be promoted through the appointment of a transition coordinator within the CF team to liaise between the pediatric and adult teams and provide education to families.

Also, ourfindings highlight the benefits of peer support from other patients with CF, but face-to-face interaction is not possible if patients are physically isolated to prevent cross-infection in clinical set-tings.75,76 Therefore, social media and

facilitated online support networks for pediatric patients with CF may be par-ticularly useful, but they must be closely monitored to ensure exchange of accu-rate information. There is some reported success in the literature in thefield of peer-to-peer health care, where patients and their families use the Internet tofind and share practical health care tips.

We suggest that more qualitative re-search is needed to assess the attitudes and experiences of children and ado-lescents regarding lung transplantation. Also, there is a paucity of qualitative data on perceptions and concerns about sexuality and infertility that could be explored further. Comprehensive and validated CF-specific quality of life instruments, such as the Cystic Fibrosis Questionnaire–Revised, are available but may be adapted to capture domains re-lating to decision-making in health care, empowerment, financial and employ-ment concerns, and future outlook.

Children and adolescents living with CF experience vulnerability, resentment, and disempowerment. Health care decision-making can be challenging given the high treatment burden and uncertainties about their prognosis, and it is arguably more difficult in the context of lung transplantation because the marked the severity of their disease and timing of waitlisting have consequences for expec-ted survival and life goals. We suggest that multidisciplinary patient-centered care should encompass strategies that pro-mote shared decision-making, control and self-efficacy in treatment management, educational and vocational opportunities, and physical and social functioning, which may lead to optimal treatment, health, and quality of life outcomes.

REFERENCES

1. Grody WW, Cutting GR, Klinger KW, Richards CS, Watson MS, Desnick RJ; Subcommittee on Cystic Fibrosis Screening, Accreditation

of Genetic Services Committee, ACMG. American College of Medical Genetics. Laboratory standards and guidelines

2. Comeau AM, Accurso FJ, White TB, et al; Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. Guidelines for implementation of cysticfibrosis newborn screening programs: Cystic Fibrosis Foun-dation workshop report.Pediatrics. 2007; 119(2). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/ cgi/content/full/119/2/e495

3. Martin B, Schechter MS, Jaffe A, Cooper P, Bell SC, Ranganathan S. Comparison of the US and Australian cysticfibrosis registries: the impact of newborn screening. Pediat-rics. 2012;129(2). Available at: www.pediat-rics.org/cgi/content/full/129/2/e348 4. Davies JC, Alton EWFW, Bush A. Cystic fi

-brosis.BMJ. 2007;335(7632):1255–1259 5. Geddes DM, Shiner R. Cysticfibrosis—from

lung damage to symptoms.Acta Paediatr Scand Suppl. 1989;363:52–56, discussion 56–57

6. Proesmans M, Vermeulen F, De Boeck K. What’s new in cysticfibrosis? From treating symptoms to correction of the basic defect.

Eur J Pediatr. 2008;167(8):839–849 7. O’Connor GT, Quinton HB, Kneeland T, et al.

Median household income and mortality rate in cysticfibrosis.Pediatrics. 2003;111 (4 Pt 1). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/ cgi/content/full/111/4/e333

8. Reid DW, Blizzard CL, Shugg DM, Flowers C, Cash C, Greville HM. Changes in cysticfi -brosis mortality in Australia, 1979–2005.

Med J Aust. 2011;195(7):392–395 9. Barr HL, Britton J, Smyth AR, Fogarty AW.

Association between socioeconomic status, sex, and age at death from cysticfibrosis in England and Wales (1959 to 2008): cross sectional study.BMJ. 2011;343:d4662 10. Aguiar KC, Nucci NA, Marson F, Hortencio

TD, Ribeiro AF, Ribeiro JD. How is living with cystic fibrosis for adolescents? Pediatr Pulmonol. 2012;47(S35):437

11. Bayer JK, Nicholson JM. Problems with sleep, eating, and adherence to therapy are common among children with cysticfi bro-sis.J Pediatr. 2009;155(5):759–760 12. Canning EH. Mental disorders in chronically

ill children: case identification and parent-child discrepancy.Psychosom Med. 1994;56 (2):104–108

13. Arrington-Sanders R, Yi MS, Tsevat J, Wilmott RW, Mrus JM, Britto MT. Gender differences in health-related quality of life of adolescents with cystic fibrosis.Health Qual Life Out-comes. 2006;4:5

14. Czyzewski DI, Mariotto MJ, Bartholomew LK, LeCompte SH, Sockrider MM. Measurement of quality of well being in a child and ad-olescent cystic fibrosis population. Med Care. 1994;32(9):965–972

15. Szyndler JE, Towns SJ, van Asperen PP, McKay KO. Psychological and family functioning and

quality of life in adolescents with cysticfi -brosis.J Cyst Fibros. 2005;4(2):135–144 16. Tong A, Flemming K, McInnes E, Oliver S,

Craig J. Enhancing transparency in report-ing the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ.BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12:181 17. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups.Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357

18. Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the the-matic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Meth-odol. 2008;8:45

19. Palmer ML, Boisen LS. Cysticfibrosis and the transition to adulthood. Soc Work Health Care. 2002;36(1):45–58

20. Berge JM, Patterson JM, Goetz D, Milla C. Gender differences in young adults’ per-ceptions of living with cysticfibrosis during the transition to adulthood: a qualitative investigation.Fam Syst Health. 2007;25(2): 190–203

21. Moola FJ, Norman ME.“Down the rabbit hole”: enhancing the transition process for youth with cysticfibrosis and congenital heart dis-ease by re-imagining the future and time.

Child Care Health Dev. 2011;37(6):841–851 22. Ayers S, Muller I, Mahoney L, Seddon P.

Understanding needle-related distress in children with cystic fibrosis. Br J Health Psychol. 2011;16(Pt 2):329–343

23. Moola FJ, Faulkner GE, Schneiderman JE.

“No time to play”: perceptions toward physical activity in youth with cystic fi -brosis.Adapt Phys Activ Q. 2012;29(1):44– 62

24. Admi H. Growing up with a chronic health condition: a model of an ordinary lifestyle.

Qual Health Res. 1996;6(2):163–183 25. D’Auria JP, Christian BJ, Richardson LF.

Through the looking glass: children’s per-ceptions of growing up with cysticfibrosis.

Can J Nurs Res. 1997;29(4):99–112 26. D’Auria JP, Christian BJ, Henderson ZG,

Haynes B. The company they keep: the

in-fluence of peer relationships on adjust-ment to cysticfibrosis during adolescence.

J Pediatr Nurs. 2000;15(3):175–182 27. Barker DH, Driscoll KA, Modi AC, Light MJ,

Quittner AL. Supporting cysticfibrosis dis-ease management during adolescence: the role of family and friends. Child Care Health Dev. 2012;38(4):497–504

28. Hafetz J, Miller VA. Child and parent per-ceptions of monitoring in chronic illness management: a qualitative study. Child Care Health Dev. 2010;36(5):655–662 29. Bregnballe V, Schiøtz PO, Lomborg K.

Parent-ing adolescents with cysticfibrosis: the

ado-lescents’ and young adults’ perspectives.

Patient Prefer Adherence. 2011;5:563–570 30. Christian BJ, D’Auria JP. The child’s eye:

memories of growing up with cysticfi bro-sis.J Pediatr Nurs. 1997;12(1):3–12 31. Patton AC, Ventura JN, Savedra M. Stress

and coping responses of adolescents with cystic fibrosis.Child Health Care. 1986;14 (3):153–159

32. Russo K, Donnelly M, Reid AJM. Segregation: the perspectives of young patients and their parents.J Cyst Fibros. 2006;5(2):93–99 33. Bywater EM. Adolescents with cysticfi

bro-sis: psychosocial adjustment. Arch Dis Child. 1981;56(7):538–543

34. Al-Yateem N. Child to adult: transitional care for young adults with cysticfibrosis.

Br J Nurs. 2012;21(14):850–854

35. Zack J, Jacobs CP, Keenan PM, et al. Per-spectives of patients with cysticfibrosis on preventive counseling and transition to adult care.Pediatr Pulmonol. 2003;36(5):376–383 36. Willis E, Miller R, Wyn J. Gendered embodiment

and survival for young people with cysticfi -brosis.Soc Sci Med. 2001;53(9):1163–1174 37. Christian BJ, D’Auria JP, Moore CB. Playing

for time: adolescent perspectives of lung transplantation for cysticfibrosis.J Pediatr Health Care. 1999;13(3 pt 1):120–125 38. Macdonald K. Living in limbo: patients with

cysticfibrosis waiting for transplant.Br J Nurs. 2006;15(10):566–572

39. Palermo TM, Harrison D, Koh JL. Effect of disease-related pain on the health-related quality of life of children and adolescents with cysticfibrosis.Clin J Pain. 2006;22(6):532–537 40. Ingerski LM, Modi AC, Hood KK, et al.

Health-related quality of life across pediatric chronic conditions.J Pediatr. 2010;156(4):639–644 41. Groeneveld IF, Sosa ES, Pérez M, et al.

Health-related quality of life of Spanish children with cysticfibrosis.Qual Life Res. 2012;21(10):1837–1845

42. Schmidt A, Wenninger K, Niemann N, Wahn U, Staab D. Health-related quality of life in children with cystic fibrosis: validation of the German CFQ-R. Health Qual Life Out-comes. 2009;7:97

43. Simmons RJ, Corey M, Cowen L, Keenan N, Robertson J, Levison H. Emotional adjust-ment of early adolescents with cysticfi bro-sis.Psychosom Med. 1985;47(2):111–122 44. Nick JA, Chacon CS, Brayshaw SJ, et al.

Effects of gender and age at diagnosis on disease progression in long-term survivors of cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182(5):614–626

46. Thomas C, Mitchell P, O’Rourke P, Wainwright C. Quality-of-life in children and adoles-cents with cysticfibrosis managed in both regional outreach and cysticfibrosis cen-ter settings in Queensland.J Pediatr. 2006; 148(4):508–516

47. Gee L, Abbott J, Conway SP, Etherington C, Webb AK. Quality of life in cystic fibrosis: the impact of gender, general health per-ceptions and disease severity. J Cyst Fibros. 2003;2(4):206–213

48. Hegarty M, Macdonald J, Watter P, Wilson C. Quality of life in young people with cystic fi -brosis: effects of hospitalization, age and gender, and differences in parent/child perceptions.

Child Care Health Dev. 2009;35(4):462–468 49. Abbott J, Hurley MA, Morton AM, Conway SP.

Longitudinal association between lung function and health-related quality of life in cysticfibrosis.Thorax. 2013;68(2):149–154 50. Tong A, Jones J, Craig JC, Singh-Grewal D.

Children’s experiences of living with juve-nile idiopathic arthritis: a thematic syn-thesis of qualitative studies.Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64(9):1392–1404 51. Woodgate RL. Adolescents’ perspectives of

chronic illness:“it’s hard.”J Pediatr Nurs. 1998;13(4):210–223

52. Tong A, Henning P, Wong G, et al. Experi-ences and perspectives of adolescents and young adults with advanced CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;61(3):375–384

53. Tjaden L, Tong A, Henning P, Groothoff J, Craig JC. Children’s experiences of dialysis: a systematic review of qualitative studies.

Arch Dis Child. 2012;97(5):395–402 54. Darcy L, Knutsson S, Huus K, Enskar K. The

everyday life of the young child shortly af-ter receiving a cancer diagnosis, from both children’s and parent’s perspectives (pub-lished online ahead of print January 8, 2014).Cancer Nurs. 2014.

55. Williamson H, Harcourt D, Halliwell E, Frith H, Wallace M. Adolescents’and parents’ experi-ences of managing the psychosocial impact of appearance change during cancer treatment.

J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2010;27(3):168–175 56. Fereday J, MacDougall C, Spizzo M, Darbyshire

P, Schiller W.“There’s nothing I can’t do—I just put my mind to anything and I can do it”: a qualitative analysis of how children with chronic disease and their parents account for and manage physical activity. BMC Pediatr. 2009;9(1):1

57. Kidd TJ, Ramsay KA, Hu H, et al; ACPinCF Investigator Group. Shared Pseudomonas aeruginosa genotypes are common in Australian cystic fibrosis centres. Eur Respir J. 2013;41(5):1091–1100

58. Bonestroo HJ, de Winter-de Groot KM, van der Ent CK, Arets HG. Upper and lower

airway cultures in children with cysticfi -brosis: do not neglect the upper airways.J Cyst Fibros. 2010;9(2):130–134

59. Grosse SD, Schechter MS, Kulkarni R, Lloyd-Puryear MA, Strickland B, Trevathan E. Models of comprehensive multidisciplinary care for individuals in the United States with genetic disorders.Pediatrics. 2009;123(1):407–412 60. Cohen-Cymberknoh M, Shoseyov D, Kerem

E. Managing cysticfibrosis: strategies that increase life expectancy and improve quality of life.Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(11):1463–1471

61. Flume PA, Taylor LA, Anderson DL, Gray S, Turner D. Transition programs in cysticfi -brosis centers: perceptions of team mem-bers.Pediatr Pulmonol. 2004;37(1):4–7 62. Withers AL. Management issues for

ado-lescents with cystic fibrosis (published online ahead of print September 6, 2012).

Pulm Med. 2012: 134132

63. Ball R, Southern KW, McCormack P, Duff AJ, Brownlee KG, McNamara PS. Adherence to nebulised therapies in adolescents with cystic

fibrosis is best on week-days during school term-time.J Cyst Fibros. 2013;12(5):440–444 64. Bregnballe V, Schiøtz PO, Boisen KA,

Pressler T, Thastum M. Barriers to adher-ence in adolescents and young adults with cystic fibrosis: a questionnaire study in young patients and their parents. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2011;5:507–515 65. Lipstein EA, Muething KA, Dodds CM, Britto MT.

“I’m the one taking it”: adolescent participa-tion in chronic disease treatment decisions.

J Adolesc Health. 2013;53(2):253–259 66. Miller VA. Parent–child collaborative

de-cision making for the management of chronic illness: a qualitative analysis.Fam Syst Health. 2009;27(3):249–266

67. Hagel LD, Mainieri AS, Zeni CP, Wagner MB. Brief report: accuracy of a 16-item question-naire based on the HEADSS approach (QBH-16) in the screening of mental disorders in adolescents with behavioral problems in secondary care.J Adolesc. 2009;32(3):753–761 68. Palmer S, Patterson P, Thompson K. A na-tional approach to improving adolescent and young adult (AYA) oncology psychoso-cial care: the development of AYA-specific psychosocial assessment and care tools.

Palliat Support Care. 2013;10:1–6 69. Ehrman WG, Matson SC. Approach to

assess-ing adolescents on serious or sensitive issues.

Pediatr Clin North Am. 1998;45(1):189–204 70. Tuchman LK, Schwartz LA, Sawicki GS, Britto

MT. Cystic fibrosis and transition to adult medical care.Pediatrics. 2010;125(3):566–573 71. Al-Yateem N. Guidelines for the transition from child to adult cystic fibrosis care.

Nurs Child Young People. 2013;25(5):29–34

72. Conway SP. Transition programs in cystic fi -brosis centers.Pediatr Pulmonol. 2004;37(1):1–3 73. Ly CN. Adolescent experiences in a major metropolitan adult hospital within the in-ner Sydney area.J Adolesc Health. 2013;52 (2 Suppl 1):S111–S112

74. American Academy of Pediatrics; American Academy of Family Physicians; American College of Physicians–American Society of Internal Medicine. A consensus statement on health care transitions for young adults with special health care needs.Pediatrics. 2002;110(6 Pt 2):1304–1306

75. Tierney S, Deaton C, Webb K, et al. Isolation, motivation and balance: living with type 1 or cystic fibrosis–related diabetes. J Clin Nurs. 2008;17(7B):235–243

76. Britton LJ, Gutierrez H, Hardy J. Patient acceptance and satisfaction with complete segregation while hospitalized. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2012;47(S35):403

77. Brumfield K, Lansbury G. Experiences of adolescents with cysticfibrosis during their transition from paediatric to adult health care: a qualitative study of young Australian adults.Disabil Rehabil. 2004;26(4):223–234 78. Graetz BW, Shute RH, Sawyer MG. An Australian

study of adolescents with cysticfibrosis: per-ceived supportive and nonsupportive behaviors from families and friends and psychological adjustment.J Adolesc Health. 2000;26(1):64–69 79. Russell MT, Reinbold J, Maltby HJ. Trans-ferring to adult health care: experiences of adolescents with cystic fibrosis.J Pediatr Nurs. 1996;11(4):262–268

80. Pizzignacco TMP, De Lima RAG. Socialization of children and adolescents with cystic fi -brosis: Support for nursing care.Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2006;14(4):569–577 81. Ellerton ML, Stewart MJ, Ritchie JA, Hirth AM.

Social support in children with a chronic condition.Can J Nurs Res. 1996;28(4):15–36 82. Henry B, Aussage P, Grosskopf C, Goehrs

JM. Development of the Cystic Fibrosis Questionnaire (CFQ) for assessing quality of life in pediatric and adult patients.Qual Life Res. 2003;12(1):63–76

83. Sinnema G, Bonarius HC, Van der Laag H, Stoop JW. The development of independence in adolescents with cysticfibrosis.J Adolesc Health Care. 1988;9(1):61–66

84. van Staa AL, Jedeloo S, van Meeteren J, Latour JM. Crossing the transition chasm: experiences and recommendations for im-proving transitional care of young adults, parents and providers. Child Care Health Dev. 2011;37(6):821–832

85. Boyle MP, Farukhi Z, Nosky ML. Strategies for improving transition to adult cysticfibrosis care, based on patient and parent views.

86. Dashiff C, Suzuki-Crumly J, Kracke B, Britton L, Moreland E. Cysticfibrosis–related diabetes in older adolescents: parental support and self-management.J Spec Pediatr Nurs. 2013; 18(1):42–53

87. Pendleton SM, Cavalli KS, Pargament KI, Nasr SZ. Religious/spiritual coping in childhood cysticfibrosis: a qualitative study.Pediatrics. 2002;109(1). Available at: www.pediatrics. org/cgi/content/full/109/1/e8

88. Sawyer SM, Tully MAM, Dovey ME, Colin AA. Reproductive health in males with cystic

fibrosis: knowledge, attitudes, and experi-ences of patients and parents. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1998;25(4):226–230

89. Swisher AK, Erickson M. Perceptions of phys-ical activity in a group of adolescents with cysticfibrosis.Cardiopulm Phys Ther J. 2008; 19(4):107–113

90. Tivorsak TL, Britto MT, Klostermann BK, Nebrig DM, Slap GB. Are pediatric practice settings adolescent friendly? An exploration of attitudes and preferences.Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2004;43(1):55–61

91. Abbott J, Holt A, Morton AM, et al. What defines a pulmonary exacerbation? The perceptions of children with cysticfibrosis.

J Cyst Fibros. 2009;8(5):356–359

92. Beresford BA, Sloper P. Chronically ill ado-lescents’ experiences of communicating with doctors: a qualitative study.J Adolesc Health. 2003;33(3):172–179

93. Foster C, Eiser C, Oades P, et al. Treatment demands and differential treatment of patients with cystic fibrosis and their siblings: patient, parent and sibling accounts.Child Care Health Dev. 2001;27 (4):349–364

94. Macdonald K, Greggans A.“Cool friends”: an evaluation of a community befriending pro-gramme for young people with cysticfi bro-sis.J Clin Nurs. 2010;19(17–18):2406–2414 95. Reynolds L, Latchford G, Duff AJA, Denton M,

Lee T, Peckham D. Decision making about risk of infection by young adults with CF (published online ahead of print January 10, 2013). Pulm Med. 2013: doi: 10.1155/ 2013/658638

96. Savage E, Callery P. Weight and energy: parents’ and children’s perspectives on managing cystic fibrosis diet. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90(3):249–252

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2014-0009 originally published online May 19, 2014;

2014;133;e1683

Pediatrics

Jonathan C. Craig and Allison Tong

Nathan Jamieson, Dominic Fitzgerald, Davinder Singh-Grewal, Camilla S. Hanson,

Studies

Children's Experiences of Cystic Fibrosis: A Systematic Review of Qualitative

Services

Updated Information &

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/133/6/e1683

including high resolution figures, can be found at:

References

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/133/6/e1683#BIBL

This article cites 94 articles, 15 of which you can access for free at:

Subspecialty Collections

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/pulmonology_sub Pulmonology

ub

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/psychosocial_issues_s Psychosocial Issues

al_issues_sub

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/development:behavior Developmental/Behavioral Pediatrics

following collection(s):

This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

Permissions & Licensing

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml

in its entirety can be found online at:

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

Reprints

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2014-0009 originally published online May 19, 2014;

2014;133;e1683

Pediatrics

Jonathan C. Craig and Allison Tong

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/133/6/e1683

located on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/suppl/2014/05/14/peds.2014-0009.DCSupplemental

Data Supplement at:

by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 1073-0397.