The Transnationalization of Protest:

A Case Study of the World Social Forum as a

Transnational Social Movement

Course Name: Comparative and International Politics Bachelor Project Teacher: Dr. D.R. Piccio

Student Name: Amna Durrani Student Number: 0951129 Word Count: 8677

Pages: 75

Date: 17.06.2013

1

Introduction

The World Social Forum (WSF), first held in 2001 in Brazil, is a global public meeting of different civil society organizations which offers a critical effort to develop a better world order, and provides an alternative to neoliberal globalization. First, it can be seen as an experimentation arena with different forms of participation and representation in a large global system. The Forum represents the further, important, testing of the democratic global governance as a whole. Second, it creates the opportunity to share a bundle of ideas, analyses and skills of people around the world. Third, the WSF is the most important space where diverse social movements come together to expand and organize their initiatives on issues. These issues mostly address towards global social norms and hold (global) corporations around the world responsible. Yet, in line with the theoretical debate about transnationalism and protest, it is unclear where the targets of the WSF are since most of the organizations do operate at the national level of protest as well (Smith 2008: 200-3).The last World Social Forum meeting was held in Tunis (2013) and is the most recent meeting where global movements come together to discuss and share their views on the world. But the question remains if their aim is to target the national, regional or transnational level. The World Social Forum 2013 has not been researched before and this will help creating my research to present new perspectives around the absence or lack of the transnational dimension, which I will discuss more briefly in the next section.

there are researchers like Giugni, Bandler and Eggert (2006) that are skeptical about the transnational contention and claim that transnational protest is still embedded within the national arena. But scholars such as Merter (2004) argue that the transnational contention of movements is growing and becoming more important than the national contexts. To understand its dynamic and this theoretical debate about the different dimensions, I shall analyze the WSF as the transnational movement par excellence.

The academic attention on transnational social movements lacks in analyzing the targets of the World Social Forum and their different dimensions. As a consequence of little academic interest in targets of protest movements a case study of the most important space where these groups come together can explain the theoretical debate on the (trans)national contention of social movements. In terms of the scientific relevance of this research thesis, the case study of a relatively new and underexposed phenomenon such as the World Social Forum is important in understanding the process of transnationalization, and in particular its targets.

2

Theoretical Framework

2.1 16th, 17th century: the nation-stateTo understand transnationalization of social movements, it is important to put it in a broader historical perspective. I will do this by confronting the growth of transnationalization with the classic social movement scenario based on the national level. In this theoretical framework I shall discuss the five main historical phases in the development of the social movement adapted from Cattacin et al.

(1997). In order to explain the emergence of transnational social movements since the 1970s, this framework will provide a brief history of the origins of transnational social movements and organizational networks (Pianta and Marchetti 2007: 31-2). Finally, I shall present a number of different academic views about the growing transnationalization of social movements.

The historical antecedents of social movements go back to the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. This is the period in which the popularity of the concept of the nation-state grew, changing the relationship between the subjects and their authority in a more profound way. The main conflict in this historical period was the state expansion, which structured the political contention. In other words, the main target of popular struggle was the dominating form of power at that time, explicitly the absolutist state affianced in war making (Giugni et al. 2006: 4).

The reliance of the states upon the resources of people meant that these people could wield some influence over the state about whether or not they were willing to cooperate with the authorities. This process of give-and-take, whereby the state expanded their armies while also providing services and platforms for political representation of citizens, challenged the old order and increased tension between different groups. Nevertheless, this conflict created the shift from a more hierarchical, aristocratic order into a more decentralized and egalitarian one (Smith 2008: 37). The seventeenth and eighteenth centuries were important in understanding the role of the state as the war-hungry absolutist and in putting the emphasis on the role of citizens. Yet we cannot speak of a genuine social movement, as the central conflicts were rather local in character, predominantly patronized by local elites and reactive (Giugni et al. 2006: 5).

2.2 The early 20th century: the labour movement

The second phase of the social movement was witnessed in the nineteenth centuries. In this period of history, the main social conflict was the class struggle and poverty, with the labour movement as the main source of collective action. The central claim throughout this period was to improve work and living condition by changing certain policies that withheld that. In order to accomplish the redistribution of policies, the labour movement took action with strikes and mass demonstration. The impact of this form of collective action had become institutionalized in other phases of development of the social movement because the rise of the national welfare systems improved the living condition of workers. In other words, the institutionalization of the labour movement had an major impact in the first half of the twentieth century, although there were signs of new movements such as the peace movement (Giugni et al. 2006: 5).

2.3 The mid-1960s: the new social movements

NGOs participated from inside and outside the official meeting. In parallel to the official UN Conference, a number of associations, scientists and research institutes organized a ‘counter-conference’. These types of global events were possible because of the importance of the issues, and perhaps a more essential reason is that these issues did not challenge the Cold War ideologies of that time (Pianta and Marchetti 2007: 34).

The rising cross-border activism can be seen as the projection of the NSMs into the transnational arena of that time by mobilizing issues related to women rights, ecology, peace and antinuclear. For instance, the solidarity movement can be considered as a big part of these moment family, both in terms of goals and social foundation. Mass demonstrations, direct actions, lobbying and the use of media were all actions of these NSMs that had a major impact on acknowledging the pluralism of society (Giugni et al. 2006: 5-6). An example of cross-border activism in this period is the international demonstrations held in 1974 against the international nuclear reactor project in Kalkar (Germany)1. However, the limited

development of global governance institutions and of powerful supranational political processes reduced the access by civil society organizations and thereby controlled cross-border activism. This explains why the NSMs were relatively successful in addressing issues in the fields of peace, women rights and international solidarity, but did not entirely address cross-border targets of this period (Pianta and Marchetti 2007: 34). This changed with the rise of the transnational social movement as a new field in the study of movements.

2.4 The 1990s: transnational social movements

From the 1990s these fragmented movements gained political awareness, together with a capacity for strengthening self-organizational networks. The end of the Cold War and the weakening of traditional ideologies supported the transition to the transnational social movements. This new form of contention emerged around both distributive and emancipatory issues. Transnational social

movements more or less address conflicts that were present during the phases of both labour movements and NSMs. Yet they differ in the scope of the conflict, which is no longer limited to the local and national level, but reaches the transnational level of protest. The central conflicts here are justice and

democracy. These concept can be addressed beyond national borders and thereby

1 Nuclear News, November 2002, James Acord: Atomic Artist. Accessed June, 2013.

reach citizens around the world. These conflicts are emblazoned in a power structure where the nation-state is losing control which leads to sharing its power with other influential actors in a system based on multilevel governance (Giugni et al. 2006:5).

The transformation of transnational social movements from the 1970s to the 1990s has left a major impact on global problems and political environment. In the first wave of transnational social movements there was not much space for transnational institutions, which made it easy for governments to indirectly control cross-border activism. By strengthening their organizational network, TSMs were successful in organizations international campaigns, counter-summits and independent global meetings. These actions allowed fragmented movements to gain political awareness against national powers. Another driver of their

success was the political context of that period. This well-defined political context made it easy for transnational social movements to grow support from public opinion and in taking advantages of favorable political opportunities (Pianta & Marchetti 2007: 37).

2.5 The process of transnationalization

The past few decades have witnessed the emergence and development of transnational social movements that oppose the neoliberal agenda of (economic) globalization. By protesting against cooperations, national governments or even supranational institutions like the World Trade Organization, the transnational social movement attempts to challenge the global (economic) processes by means of collective action at the international level. Simultaneously, organizations within this process of cross-border interest also lead campaigns at the national level, partially because local obstacles make it difficult to promote international campaigns. In other words, transnational organizations are confronted with a paradox where they might ''think globally'', but are constrained to ''act locally'' (della Porta and Kriesi 1999: 20). Koopmans (2009) is right when he argues that national patterns and conditions played a major role in shaping the extent to which people mobilized in different countries. Nevertheless, this does not mean that a transnational protest only targets the national level actors.

comprised of mobilized networks of individuals, groups and organizations which attempt to achieve or prevent social change, predominantly by means of collective protest.” Attached to this definition, it is important to understand the non-hierarchical structure of interactions between actors through the concept of

network provided by Keck and Sikkink (1998). These so-called advocacy networks may be key contributors to a convergence of social, political and cultural norms able to support processes of transnationalization. By building links among civil societies, states and international organizations, they increase the level of opportunities for dialogue and exchange. As a consequence of this interaction, these networks blur the boundaries between a state's relationship with its own nationals and the recourse both citizens and states have towards the international system (Keck and Sikkink 1998: 92-93).

Transnational advocacy network includes those actors working internationally on a issue, who are bound together by shared values, a common discourse, and dense exchanges of information and services. These networks are called 'advocacy' networks because, just like advocates, they plead the causes of others or defend a proposition; they are stand ins for persons and ideas. When the pleading of causes or ideas takes place beyond the national borders, the networks can be seen as agents operating transnationally. Transnational networks are most likely to emerge around issues where the relationship between domestic groups and their governments are severed, where such relationship is ineffective for resolving a conflict, and where activists or 'political entrepreneurs' believe that networking will contribute their missions and campaigns. The emergence of transnational networks also depends heavily on how international conferences and other forms of international contact create arenas for forming and strengthening networks. The metaphor of the '''boomerang effect'' describes this strategy whereby movements enter the international arenas to change behaviours of governments (Keck and Sikkink 1998: 92-93; Smith 2004: 216).

with power-holders in at least one state other than their own, or against an international institution, or a multinational economic factor.” In other words, the transnational aspects refers to different dimensions of a movement, such as issues, targets, mobilization, and organizations, even when one of these dimensions appears as transnational, the others may remain national. For this reason, one cannot automatically assume that transnational movement are exclusively or even primarily focused on international politics (Rucht 1999: 207).

One of the key elements of any transnational social movement is the spread of its ideas from one country to another. The shift of issues beyond national borders is known as diffusion (Smith 2004: 325). This process of transnationalization can be seen in both directly and indirectly forms, and is also known as relational and non-relational diffusion. Relation diffusion depends on existing relationships between individuals or groups. Whereas non-relational diffusion focuses on how to gather useful information indirectly through mass media (della Porta and Kriesi 1999: 6). These forms of transnationalization depend on how actors identify with each other. Diffusion may occur when these actors share the same general culture or have a common border. It is important to understand that the mechanism of diffusion can only be successful if political opportunities at the national level are also presented (Tarrow and McAdam 2005: 127-128).

The international environment has an important impact on social movements that try to engage in that arena, yet transnational social movements are still dependent on the national context from which they emerge. Though, several academics argue that the relevance of the nation-state idea is declining because of the loss of sovereignty towards international institutions. The targets of any movement are at least partially relying on nation-state structures for success or failure (Marks and McAdam 1999: 99-105). The openness of national political institutions, support of political parties in the government and effective mobilization structures play a major role in whether or not movements are able to address their targets (Kriesi et al. 1995; della Porta and Kriesi 1999: 9-10). In a similar vein, many social movements use opportunities created by international institutions to gain leverage against their national governments, who they may consider to be their main targets. This process is also known as externalization

(Rootes 2005; della Porta and Tarrow 2005: 9).

An important strategy of TSMs, and a form of global integration, is the campaigning at the national level with the aim to affect global issues. This form of transnationalization, whereby movements operate at the national level of conflicts but have their origin externally, is knowns as internationalization. An example of internalization is the 2009 protest of French fishermen against EU fishing quotas.2 Because internalization is attached to multilayered polity,

responsibility is often difficult to locate (della Porta and Kriesi 1999: 15). Nevertheless, internalization may be a suitable strategy when it is difficult to directly target a movement's opponents. Since national governments are represented in international institutions, they can be held responsible for the policies of these institutions. In general, internalization can be seen as a limited form of transnationalization because it only happens when groups are prevented to deal with international issues directly (Daly 2002: 1).

Another part of the global integration is known as the ongoing phenomenon of ‘‘globalization’’ or “the global economic integration of formerly national economies into one global economy...the effective erasure of national boundaries of economic purposes” (Held and McGrew 2000; Scholte 2000). This process involves a fundamental shift in the scale of social movements and expands the reach of power relations across the world. In other words, one may

argue that the uneven nature of economic globalization can form a greater security threat for some states. On one hand protests to seek change can often become violent, and on the other hand economic globalization accentuates differences in societies which may create instability in regions and challenge the world order. Many would claim that globalization challenges national sovereignty. Though states have not (yet) lost their authority. However, the process of globalization has a significant impact on domestic politics and power structures (Lamy 2008: 136-137).

In many ways transnational social movements have successfully shifted issues away from the state. One may argue that transnational protest against nuclear, by using the internet, the press and activists networks, undermines the power and security of a state. In terms of targets, this shift in power can be seen when movements try to address issues on a more global, transnational level instead of the national contexts. Conversely, this does not mean that national governments do not play the critical role in implementing the reforms advocated by social movement actors (Van Dyke et al. 2004: 28). National governments are often targets of many issues since they still have the major power to decide which issues make it onto the policy agendas. Targets are the institutions, governments and networks movements are trying to address. Even when mobilization takes place at the national level and thereby withholding a 'global civil society', there is a ongoing trend where transnational protest target transnational level actors. In the next section I shall provide a protest case scenario and discuss the academic debate about the different dimensions of protest.

3

The theoretical debate

3.1 Protest case scenario: globalization or national politics?

movements rely mostly on the national contention in accomplishing their goals. The most interesting case to start with is the one about the Gulf War because it illustrates the importance of international protest in general, and the transnationalization of the protest dimension (Koopmans 2009: 57).

In terms of cross-national influences on political behaviour and in study of social movement mobilization in particular, the protest against the Gulf War is a very interesting object of analysis. The phrase ‘No Blood for Oil’ became the global slogan of that phase. In this sense, the Gulf War can be seen as the first major global war, backed by United Nations resolutions. The most important element that distinguishes the Gulf War from others was the extent to which it was covered by the media. In other words, the global scope of the Gulf War issue and the extraordinary similarities between the information citizens all over the world received, make it an almost perfect case to see how far globalization has advanced and to what extend the national contention matters. Koopmans (2009) argues that the Gulf War has been the political event in which globalization has become the most prominent. For the first time, the United Nations acted as a world government and social movements across the globe were exposed to this global event. Nevertheless, the domain of politics remains in the context of the nation-state. The national contention is still the principal framework in this case. Protests in France, Germany and the Netherlands showed that there were strong differences in the volume and forms of mobilization. Even the role of transnational movements differed between the countries (Koopmans 2009: 68).

3.2 Different dimensions of the debate

The statement that the national contention is the most important in influencing the transnational dimension of protest is also backed up by Giugni et al. (2006) in their article ‘The Global Justice Movement’. Unlike certain of number of scholars, that I will discuss later, Giugni et al. are quite skeptical about this so-called transnational protest cycle. In their view it overlooks the crucial impact of a number of domestic factors and overstates the idea of a 'global civil society.' Giugni et al. (2006) stress out that every protest cycle rests on previous mobilizing structures and episodes of contention.

In their article Giugni et al. put the Global Justice Movement in a broader context to show that the national context remains crucial for transnational contention, such as those staged by GJM. They have argued that movements such as GJM act within a multilevel political opportunity level where national contexts impinge on their mobilizations. The degree of openness of the political system, the pattern of political alignments, the presence of powerful allies, the strategies of the authorities, but also the pre-existing social networks in which participants of movements are entrenched, explain why the mobilization of GJM differs from one country to another. In other words, protests that occur on the transnational level still rely on networks of actors within the national arena (Giugni et al. 2006: 3-18).

Sidney Tarrow (1989, 2001) and Tim Mertes (2004) claim that the protest cycle attests to the emergence of a “movement of movements” and argues that the nationally based forms of contention are declining. Both of them put the emphasis on a new civil society; one that is based at the transnational level. In particular Tarrow (1989) describes in his book ‘Democracy and Disorder: Protest and Politics in Italy, 1965-1975’ the process towards a global civil society where the national context matters less than the impact of transnationalization. Yet, as pointed out earlier, this debate about the (trans)nationalization of protest does not involve two different, rival camps but instead shows how scholars themselves find it hard to take a cut-clear position regards this matter.

transnational level. The volume’s editors conclude on this point that “because we do not believe in a distinct transnational sphere, we think that these domestic factors are crucial determinants of the strategies of movements active transnationally” (Tarrow and Della Porta 2005: 242).

On one hand, there is a resemblance among diverse protests that arise across the globe and in targeting supranational organizations. This can be seen by using slogans such as “Another World is Possible” (George 2004). On the other hand, one should be careful in using concepts and slogans such as “movement of movements” (Mertes 2004) and ‘’Another World is Possible’’ because they imply the emergence of a single world protest movement, a conclusion which is, at best, presumptuous (Giugni et al. 2006: 12).

Another scholar, Jackie Smith, tries to justify how transnational networks of social movement activists have worked to promote human rights and sustainability over the neoliberal system, and that the transnational dimension of protest is growing in reaching its targets. However, in Transnational Processes and Movements (2004), she argues that transnational movement strategies and processes are parallel to developments of national social movements. In other words, the global political processes are a continuation of the same kind of dynamics contributed to the formation of nation-states. Similar to this argument, Smith also states that “in many ways, the form and dynamics of movements we see in the transnational arena resemble their national and local predecessors, even as they are adapted to fit a transnational political context” (2004: 320).

4

The World Social Forum Process

4.1 Background

Global Justice Movements became increasingly influential throughout the 1980s and 1990s. The Zapatista movement in Mexico organized these types of events, such as the ‘’Meeting for Humanity and against Neoliberalism’’ in 1996, to put regional struggles on the map. The Zapatista movement can be seen as an inspiration to hold more events in the same spirit in Spain in 1997 and Brazil in 1999. The emergence of these movements in global sphere received plenty of media attention but they did not have any influence on how they were portrayed by the mass media. Particularly, when mass protests were extremely violent with the help of radical groups, there was less these movements could do in terms of the space of information, deliberation and decision-making. No one was surprised that the idea of a World Social Forum was met with great enthusiasm (Rucht 2006: 3).The World Social Forum can be seen as a new platform of protest for people around the globe. During its inception, the WSF was sit in opposition to the World Economic Forum. The latter was held first in Davos (Switzerland) in 1971 as an informal and exclusive space for economic leaders. The WSF takes place at the same time as the WES, but the WSF focuses on the social, rather than the economic dimension. The WSF sees itself as a global platform for the ‘people’ instead of the ‘elites’ and after its inception, the fundamental ideas of the forum were also spread to the continental, national and local level (Rucht 2006: 3).

4.2 The World Social Fora

The first WSF was based on an initiative of eight organizations3 in February 20004 and took place in Porto Alegre (Brazil) in January 2001. The meeting was

hosted by the local and regional Labor Party (PT) and roughly 20,000 participants attended the Forum. These participants came from over more than 100 countries, with several thousands of delegates from NGOs and hundreds of Members of Parliament from various countries. The reason why the organizers chose Porto Alegre as their first location was because the Brazilian NGOs promoted it and the

3 The initiative for the first WSF gathering came from Brazilian organizations such as ABONG (a

Brazilian NGO), CBJP (the Brazilian Committee for Peace and Justice), CIVES (an organization of entrepreneurs for civil rights), CUT (workers and employees alliance), IBASE (a scientific

institute for socio-economics), CJB (Global Center for Justice), and MST (the movement of landless peasants). (adapted from Rucht 2006: 3)

city uses a “participatory budget” in order to incorporate ‘ordinary’ people who did not have a say in the local decision-making. Another important reason is that both the city and the state of Rio Grande do Sul promised to provide financial and infrastructural assistance in hosting the event (Rucht 2006: 5).

The following two events in 2002 and 2003 were also held in Porto Alegre (Brazil). The events were organized by an almost identical committee of those eight Brazilian founding organizations. The next event was held in Mumbai (India) in 2004 and backed by the “Indian Organizing Committee”. The event in Mumbai had a different character from the previous ones because hundreds of Indian groups attended it. These marginalized people, mostly ranged at the bottom of the Indian caste system, were present in large numbers and kind of changed the scope of the event. In 2005 the event once again took place in Porto Alegre, which by now formed the home base of the WSF. This time, the ‘Brazilian Organizing Committee’ was extended to 23 groups5 and subdivided

into eight work groups (Rucht 2006: 5-6).

In 2006 three ‘’polycentric WSFs’’ were held in Bamako (Mali), Caracas (Venezuela) and Karachi (Pakistan). The event in Venezuela received plenty of media attention because of the prominent role of president Hugo Chaves but the other two events passed by rather unnoticed from the global mass media. The WSF event in 2007 that took place in Nairobi (Kenya) was chosen to symbolically to strengthen the role of GJM’s in Africa. More than 50,000 participants attended this meeting; most of them were Africans (Rucht 2006: 6).

The WSF event of 20086 was not organized at one particular place, but on a

more global level. This is the first time the WSF is trying to put the emphasis on one global, open space for people around the world. The global element derives from thousands of autonomous, local networks known as the ‘’Global Call for Action’’. Approximately 1,900 indigenous people that represented 190 ethnic groups attended the event to raise concern about the rights of stateless peoples and the difficulties they face. The tenth edition of the World Social Forum took place across the world with 35 different national, regional and local forums7. In

5 Open Space Forum, March 2013. Accessed in May 2013.

http://www.openspaceforum.net/twiki/tiki-read_article.php?articleId=276

6WSF event, 2008. Accessed in May 2013.http://www.wsf2008.net/eng/home

Porto Alegre, the major events were held in celebration of the ten years anniversary of the Forum. The seminar that received the most attention was the one about challenges. This edition of WSF helped setting up regional forums such as the US Social Forum held in Detroit (Michigan).

The WSF meeting in 2011 took place in Dakar (Senegal) with more than 75,000 participants from 132 countries. Many prominent figures such as the Canadian social activist and author Naomi Klein and the Bolivian president Evo Morales attended the event. The event had some big obstacles to overcome, mainly because of the poor logistic facilities and a student strike against President Abdoulaye Wade’s policies. Last but not least, the changes in Egypt and the Arabic Spring in particular, were received with great enthusiasm among the attendees. The meeting in 2012 provided an alternative discussion on topics about the environmental crisis and the creation of a global society. The most recent meeting of the WSF was held in Tunis and was centered on the Arab Spring case and the future of democracy.

5

Methodology: data and method

5.1 Data

Countless reports and opinions published about the WSF did not capture the context of themes and organizations, nor did they provide information where I could extrapolate data from. In order to explain what kind of organizations took part at WSF 2013, where they are located and on what level they address their targets, I performed a content analysis on 9 PDF files8 which can be found on the

WSF website. These files contained 923 themes of the event and 769 organizations that arranged those theme discussions during the event held in Tunis on 27th, 28th and 29th of March. Firstly, I captured all the main themes

discussed during the event and counted how often they targeted the national, regional or the national levels and did the same with the organizations. The reason I chose to go through themes and organizations separately is because often national organizations covered transnational themes and vice versa. Given priority to the context of the theme and its main organizations, I then proceeded to distinguish them based on their target level and geographical scope. For

example, the Arab NGO Network for Development organized the theme “Rethinking the Development Models after Peoples’ Revolutions in the Arab Region” which clearly targets the Arab region as a whole and is organized at the regional level. For this reason, I shall now make clear on what grounds the distinction is made and present the three types of level that were observed through the data I collected from the WSF programme list.

5.2 National, regional and transnational level of protest

The national level of protest refers to links among non-state actors and social movement mobilization within the national borders. For this reason, the target of participation, meaning the actors that people are attempting to influence, remains in the context of the nation-state. The regional level links states, non-state actors and institutions within a specific geographical area or political region. However, this does not mean that regional organizations only operate within regional borders; they often try to target local and national levels of protest as well. To make a precise distinguish for my research, the regional level can only be seen as ’regional’ if the theme attached to that level has a direct relationship to a specific region and the organization targets the regional level primarily. The transnational level connects states, non-state actors and international institutions. At this level there is a class with social networks that aims to build bridges between the local, national and the so-called global level (Tarrow 2005: 23). As pointed out by Della Porta (2005) these entrepreneurs are “rooted cosmopolitans”. They are ‘cosmopolitan’ because they have multiple, flexible identities and they are ‘rooted’ for the reason that national societies motivate them to target levels beyond the nation-state.

National level the actors that people are trying to influence operate within the national context.

Regional level the actors that people are trying to influence are linked by a geographical relationship and by a degree of mutual interdependence (Nye 1968). Transnational level refers to the links among non-state actors that

mobilize beyond the nation-state and targets mainly global issues by using the goals of transnational actors (Nye and Keohane 1972).

The data gathered through the progamme list is coded by analyzing the words in themes and searching the main organization attached to that specific theme. For coding the national level I have simply focused on words such as ‘national’, a specific country's name and looked if the main organization operated at the national level as well. An example from the coding sheet is the theme ''Role of Tunisian Labour Unions in the Democratic Transition''. The topic is directly linked to the Tunisian labour unions so I classified the theme as national. However, since sometimes regional or even transnational organizations covered national themes, I also looked at what level the main organization tries to address the targets the most. The organization Confédération Générale Tunisienne du Travail (CGTT) is a Tunisian organization that mainly targets the national contexts. The theme and the context of this example indicate that it targets the national level the most, so I coded this as national.

For the regional level I maintained the same procedure as for the national level. However, I looked more specifically at the main organizations and their websites to know on what level they operate the most. For instance, the theme ''World markets versus food security. Where is Africa headed? How to advocate for sustainable food security?'', covers the sustainable food insecurity in the region of Africa so I coded the theme as 'regional'. The organization that arranged this theme discusion is FECCIWA. This organization is located in Africa and is mainly concerned about regional targets and issues; therefore I coded this theme as 'regional'. In some cases the themes were constructed more broadly and the organization attached to it did not give the operation level away. In this case, I usually went through their website to see what they have achieved so far in terms of targets and issues.

targets can be made. When no information about the theme or organization was available I simply excluded the topic as 'unknown'.

5.3 Method

The method used in this research is content analysis. Ole Hostli (1969) defines this methodology as “a summarising, quantitative analysis of messages that relies on the scientific method (including attention to objectivity, intersubjectivity, a priori design, reliability, validity, generalisability, replicability, and hypothesis testing) and is not limited as to the types of variables that may be measured or the context in which the messages are created or presented.” By performing a quantitative content analysis, combined with Keyword in Context routines, words can be analysed in their specific context, which helps eliminate any doubtfulness or uncertainty as regards of interpretation. The distinction between these different levels of operation was important because it displays how the content analysis goes beyond word or number count in categorizing and classifying the programme list of WSF 2013. The process of an in-depth content analysis on WSF documentations identifies what exists at the event. It also helps to understand who take part of the WSF event and what these organizations are sharing. It can also be used as a tool to comprehend the large, geographical scope of the WSF. The data of this research made it possible to relate the theme and organizational context of the analysis, which lead to the classification (see Appendix). A lot of these organizations referred the ‘national commission’, or stated that they were a ‘Tunisian organization for Arab women’, or were a ‘global network’. Ultimately, in keeping the context in mind and in getting results through the programme list, the content analysis proves to be the most suitable research method.

6

Results

6.1 The ideology of WSF

The ideological roots of the WSF are laid out their Charter 9. Throughout the

history of WSF many charters and declarations at events were published, but these charters reflected the opinions and reports of their authors. Nonetheless, the Charter presented on their website reflects the ideological base of WSF and

summarizes their process. Its mission is reflected in the first and fourth paragraph in of a total of fourteen points:

“The World Social Forum is an open meeting place for reflective thinking, democratic

debate of ideas, formulation of proposals, free exchange of experiences and interlinking for effective action, by groups and movements of civil society that are opposed to neoliberalism and to domination of the world by capital and any form of imperialism, and are committed to building a planetary society directed towards fruitful relationships among Humankind and between it and the Earth” (WSF 2013: 1).

‘”The alternatives proposed at the World Social Forum stand in opposition to a process of globalization commanded by the large multinational corporations and by the governments and international institutions at the service of those corporations interests, with the complicity of national governments. They are designed to ensure that globalization in solidarity will prevail as a new stage in world history. This will respect universal human rights, and those of all citizens - men and women - of all nations and the environment and will rest on democratic international systems and institutions at the service of social justice, equality and the sovereignty of peoples” (WSF 2013: 1).

In other words, the WSF is a process that wants to introduce the global agenda and encourage its participants in seeking an active role in transnational contexts. They present themselves as global democratic governance with more than thousands of organizations attached to their events. By looking at the targets of the WSF we may expect to see if the WSF is truly a global, democratic space. The analysis of their programme list gives a good indication on what level the targets of the WSF meetings operate and from which part of the world the organizations of the WSF come from. The latter can be analyzed through looking at the geographical scope of the event.

6.2 Targets

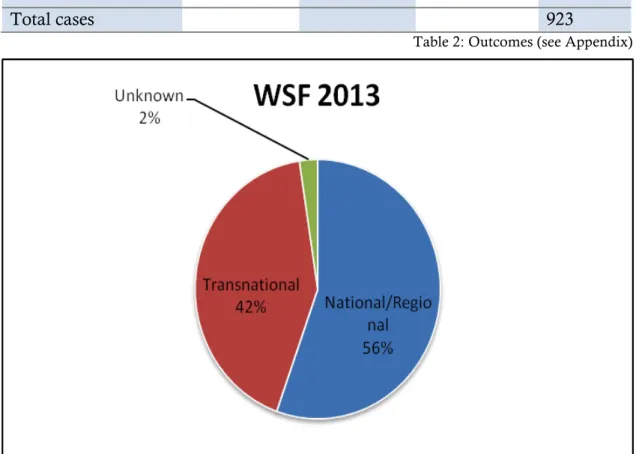

As mentioned before, the cases are the WSF themes within their organizational context and distinguished on three levels: national, regional and transnational. 22 cases were unknown, meaning that no particular theme was discussed or no information about the organization was available. From the total cases, 303 targeted the national levels, 205 cases addressed the regional levels and 386 targeted levels beyond the national and regional scope. However, at first (see Appendix) it looks like that these organizations target the transnational the most, but combining the national and regional brings the total of everything ‘not’ transnational to 508 cases, which is significantly more than 386.

Targets

organizations WSF 2013

National

level Regional level Transnational level Unknown cases

Total cases 923

Table 2: Outcomes (see Appendix)

Figure 1 (See Appendix)

Another remarkable observation is that most of the organizations that operated as transnational networks were actually accumulations of national organizations targeting global themes such as “the climate change’’ or “the struggles of the minors in Europe in Arab”, the latter containing only national organizations that joined together in a transnational network. This means that transnational networks are rooted within national organizations and are not (yet) an entirely autonomic phenomenon within the study of social movements. Furthermore, the national and regional levels are covering 56 percent of the full programme, whereas the transnational level controls 42 percent of the targets (see Appendix). This means that the organizations are targeting the national and regional levels more than that they are targeting the transnational level.

6.3 The geographical scope of WSF

that the WSF marks an important milestone in the global arena by presenting alternatives to neoliberal globalization, it relies on activism within the national tradition. On one hand, the national and regional social forums dictate the power to politically influence the ones that can change policies; on the other hand it depends on transnational network as well. However, it is comprehensible that not only more than half of organizations are based at the national and regional level; they also come from specific regions. This finding shows how the WSF fails to get those people involved that disadvantage the most from the “danger of neoliberal globalization.”

Geographical scope WSF 2013

50%

13% 10%

3% 1%

5% 1%

17%

MENA region EU SOUTH AMERICA

NORTH AMERICA ASIA CENTRAL AFRICA CENTRAL AMERICA UNKNOWN

Geographical scope WSF 2013 held in Tunisia (see Appendix).

7 Conclusion

state. In terms of targets, this shift is exposed when targets at the transnational level are addressed increasingly more, than targets at the national level. In my research I tried to explain the relationship between these two through a content analysis on the programme list of the WSF 2013. By distinguishing the levels that organizations try to target, it was possible to see what levels are being addressed the most. The observation that the targets were met more at the national and regional levels rejects the hypothesis that the transnational level is the most important one for organizations to reach their targets. To see whether the WSF is a global, transnational reality I looked at the geographical scope of the meeting in 2013. This analysis of the scope supported the claim that national level is still very important in addressing targets and showed that half of the cases were from the MENA region. Even the so-called transnational organizations, were actually networks of various national organizations targeting issues on a more transnational level. Consequently, patterns of national and regional contexts were in majority presented at the WSF meeting in 2013. Some scholars are still skeptical about the transnational contention of the social movement agenda, yet the World Social Forum proves to be an outlet of global, transnational issues.

Bibliography

Cattacin, Sandro, Marco G. Giugni and Florence Passy. 1997. Etats et mouvements sociaux. La dialectique de la société politique et de la société civile. Arles: Actes Sud. Daly, Herman E. 2002. Globalization Versus Internationalization, and Four Economic Arguments for why Internationalization Is a Better Model for World Community.

http://bsos.umd.edu/socy/conference/newpapers/daly.rtf(Accessed June,

2013).

della Porta, Donatella, Hanspeter Kriesi, and Dieter Rucht, eds. 1999. Social Movements in a Globalizing World. New York: St. Martin's Press.

della Porta, Donatella and Hanspeter Kriesi. 1999. “Social Movements in a Globalizing World: an Introduction.” In Social Movements in a Globalizing World, ed. Donatella della Porta, Hanspeter Kriesi, and Dieter Rucht. New York: St. Martin's Press, 3-22.

della Porta and Mario Diani. 2006. Social Movements: An Introduction. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

della Porta and Sidney Tarrow. 2005. Transnational Protest and Global Activism.

New York, Rowman and Littlefield.

Diani, M. 1992. "The concept of social movements". The Sociological Review,

Volume 40, Issue 1, 1-25.

Giugni, M. et al. 2006. The Global Justice Movement: How Far Does The Classic Social Movement Agenda Go In Explaining Transnational Contention? In United Nations Research Institute for Social Development.

Held, David and Anthony McGrew , eds. 2000. The Global Transformations Reader: An Introduction to the Globalization Debate. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Keck, Margaret and Kathryn Sikkink. 1998. “Transnational Advocacy Networks in

International Politics: An Introduction.” In Activist Without Borders. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1-38.

Lamy, S.L. 2008. “Contemporary Mainstream approaches: realism and neo-liberalism.” In The Globalization of World Politics, eds. John Baylis, Steve Smith en Patricia Owens. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 127-133.

Marks, Gary and Doug McAdam. 1999. “On the relationship of political opportunities to the form of collective action: the case of the European Union.” In Social Movements in a Globalizing World, ed. Donatella della Porta, Hanspeter Kriesi, and Dieter Rucht. New York: St. Martin's Press, 97-111.

Nye, Joseph S. 1968. International regionalism; readings. Harvard University. Center for International Affairs. Boston : Little, Brown.

Hostli. Ole R. 1969. Content Analysis for the Social Sciences and Humanities.

Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Pianta, M. and R. Marchetti. 2007. '”The Global Justice Movements. The transnational Dimension.” In The Global Justice Movement: cross-national and transnational perspectives, eds. Donatela della Porta. Boulder, Co: Paradigm, 29-30. Rootes, Christopher. 2005. “A Limited Transnationalization? The British Environmental Movement.” In Transnational Protest and Global Activism, ed. Donatella della Porta and Sidney Tarrow. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 21-44.

Rucht, Dieter. 1999. “The transnationalization of social movements: Trends, Causes,

Problems.” In Social Movements in a Globalizing World, ed. Donatella della Porta, Hanspeter Kriesi, and Dieter Rucht. New York: St. Martin's Press, pp. 206-222.

Rucht, D. 2006. "Social Fora as Public Stage and Infrastructure of Global Justice Movements." Presented at the Annual Conference of Contentious Politics and Social Movements in the 21st Century, Atene, Grecia.

Scholte, Jan Aart. 2000. Globalization: A Critical Introduction. New York: St. Martin’s.

Smith, J. 2004. "Transnational Processes and Movements." In The Blackwell Companion to Social Movements, eds. A. Snow, S.A. Soule and H. Kriesi.

Cambridge: Blackwell Publishing, 311-335.

Smith, J. 2008. Social Movements for Global Democracy. Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Tarrow, S. 1989. Democracy and Disorder: Protest and Politics in Italy, 1965-1975.

Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Tarrow, S. 2001. “Transnational Politics: Contention and Institutions in International Politics.” Annual Review of Political Science 4:1-20.

Tarrow, S. 2005. The New Transnational Activism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tarrow, Sidney, and Doug McAdam. 2005. “Scale Shift in Transnational Contention.” In Transnational Protest and Global Activism, ed. Donatella della Porta and Sidney Tarrow. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 121-147.

Tilly, C. 1990. Coercion, Capital, and European States, AD 990–1990. Cambridge, MA:Blackwell.

Tilly, C. 2004. Social Movements, 1768-2004. Boulder, London: Paradigm Publishers.

Touraine, A. 1981. The voice and the eye: An analysis of social movements. New York: Cambridge University Press.