Prevalence and Correlates of Obesity and Overweight in

Tunisian Bipolar I Patients

Asma Ezzaher1,2*, Anwar Mechri2, Dhouha Haj Mouhamed1,2, Wahiba Douki1,2, Lotfi Gaha2, Mohamed Fadhel Najjar1

1Biochemistry and ToxicologyLaboratory, Monastir University Hospital, Monastir, Tunisia; 2Research Laboratory “Vulnerability to

Psychotic Disorders LR 05 ES 10”, Department of Psychiatry, Monastir University Hospital, Monastir, Tunisia. Email: *ezzaherasma@yahoo.fr

Received January 11th, 2013; accepted February 12th, 2013; accepted March 2nd, 2013

Copyright © 2013 Asma Ezzaher et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

ABSTRACT

Objective: We aim to determine the prevalence of obesity and overweight in bipolar I patients, and to examine their

associations with the demographic, clinical and therapeutic characteristics of this population. Patients and Methods:

Our study included 120 bipolar I patients (79 men and 41 women, mean age = 39.5 ± 11.9 years). Weight and height were evaluated by body mass index (BMI). Obesity was defined when BMI ≥ 30 kg/m² and overweight when BMI ≥ 25 kg/m². Results: The prevalence of obesity and overweight was respectively 32.5% and 30.8%. Obesity was signifi-

cantly more frequent in women than men. The illness duration was significantly longer in obese patients than in those with normal weight. Moreover, the family history of medical disorders and concomitant medical disorders was signifi- cantly more frequent in obese patients than in those with normal weight. However, any significant association between therapeutic characteristics and obesity or overweight was found. Conclusions: Obesity and overweight were frequent in

bipolar I patients. Obesity was significantly frequent in women and significantly associated with illness duration, medi- cal disorders, and concomitant medical disorders. These results emphasized the need for specific treatment strategies and programs for weight control for these patients.

Keywords: Bipolar I Disorder; Obesity; Overweight

1. Introduction

Bipolar disorder (previously also labelled as manic-depres- sive illness) is typically referred to as an episodic, yet lifelong and clinically severe affective (or mood) disorder, affecting approximately 3.5% of the population [1-5]. It is a chronic disease that is associated with a potentially de- vastating impact on patients’ wellbeing and social, oc- cupational, and general functioning [6]. The disorder ranks as the sixth leading cause of disability in the world, with an economic burden that in the US alone that is es- timated more than a decade ago at $7 billion in direct medical costs and $38 billion (1991 values) in indirect costs [7].

A number of reviews and studies have shown that people with severe mental illness, including bipolar dis- order, have an excess mortality, being two or three times as high as that in the general population. This mortality gap, which translates to a 13 - 30 year shortened life ex-

pectancy in severe mental illness patients, has widened in recent decades, even in countries where the quality of the health care system is generally acknowledged to be good. About 60% of this excess mortality is due to physical illness especially cardiovascular disease [8].

Cardiovascular risk factors in this pathology include nonmodifiable risk factors, such as sex, family history, personal history, and age, as well as such modifiable risk factors as obesity, smoking, diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia [9].

Obesity is the condition of having an abnormally high proportion of body fat. It is most commonly operation- ally defined as a body mass index (BMI) of 30 or greater. Abdominal obesity reflects fat that is centrally distributed between the thorax and pelvis as opposed to lower body obesity, which reflects fat that is distributed around the hips, thighs, and buttocks. Abdominal obesity is often operationally defined by the waist circumference or the waist-to-hip ratio. In contrast to lower body obesity, ab-dominal obesity is particularly associated with type 2

diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, hypertension, coronary heart disease, stroke, and early mortality.

Although the pathogenesis of obesity is unknown, it is often viewed as a polygenic, heterogeneous metabolic disorder due to consuming more calories than expended as energy.

Factors etiologically associated with obesity are family history of obesity, overeating, and physical inactivity. Low resting metabolic rate is not thought to play a major role in causing or maintaining most obesity. Of theoreti- cal note, dysfunction in neurotransmitter and neuropep- tide systems hypothesized to underlie various mental disorders, including bipolar disorder, has also been hy- pothesized to be involved in obesity. Implicated shared neurotransmitter systems have included serotonin, dopa- mine and norepinephrine. Implicated neuropeptides have included corticotrophin-releasing factor and neuropeptide Y [10].

Our study aims to determine the prevalence of obesity and overweight in patients with bipolar I disorder, and to examine their associations with the demographic, clinical and therapeutic characteristics of this population.

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. Subjects

Our study included 120 patients with bipolar I disorder from the psychiatry department of the University Hospital of Monastir, Tunisia, aged 39.5 ± 11.9 years, 79 men (39.6 ± 10.9 years) and 41 women (39.3 ± 13.7 years). Con- sensus on the diagnosis, according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV) criteria [11], was made by psychiatrists. The exclusion criteria were age < 18 years, other psychiatric illnesses, epilepsy or mental retardation. This study was approved by the local ethical committee and all subjects

were of Tunisian origin. Written informed consent was

obtained from all voluntary participants.

All subjects were questioned about their age, gender, cigarette and alcohol consumption habits and clinical and therapeutic history. The socio-demographic and clinical characteristics (age at onset, the total number of episodes, number of manic episodes, depressive polarity at index episode, severity of index episode, duration of illness and the number of lifetime suicide attempts) are shown in

Table 1.

2.2. Body Mass Index (BMI) Determination

BMI was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height (m²). For the present study, we adopted the classification of overweight and obesity formalized by the World Health Organization [12]. This classification uses the same cutoff points reported in the evidence-based clinical guidelines for the identification, evaluation, and treatment of over-

weight and obesity in adults, published by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health [13]. Men and women were considered to be underweight if their BMI was less than 18.5, normal weight if their BMI was between 18 and 24.9, overweight if their BMI was between 25 and 29.9, and obese if their BMI was equal to or greater than 30 kg/m².

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 17.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).Quantitative variables were presented as mean ± SD and comparisons were performed using the Student’s t test. Qualitative variable compari- sons were performed using the Chi-squared test (χ2) and

Fisher’s exact test (when n < 5).

The statistical significance level was set at P < 0.05. All variables with a p value < 0.25 between the two studied groups were considered as potential confounder factors for this analysis.

3. Results

In bipolar I patients, the prevalences of obesity and overweight were 32.5% and 30.8% respectively (Table 1).

Obesity was more frequent in women than men (46.3%

Vs 25.3%, p = 0.04) (Tables 1 and 2). Women have also

the highest rate of unemployment (63.4% Vs 31.6%, P = 0.001) (Table 1).

We noted that men were so much more likely to be smokers and alcoholic consumers than women (91.1% Vs

2.4%, P < 0.0001; 57% Vs 2.4%, P < 0.0001). In addition, they have the highest number of manic episodes (3.8 ± 2.3

Vs 2.8 ± 2.6; P = 0.04) (Table 1).

We showed that there were no significant differences in demographic characteristics, in terms of age, education years and unemployed status, between study groups (obese, overweight and normal patients). Tobacco and alcoholic use were also not significantly associated with obesity or overweight.

Concerning clinical characteristics, we showed that the duration of disease was longer inobese patients (14.8 ± 7.8 years) and overweight patients (12.6 ± 8.4 years) than in those with normal weight (9.6 ± 7.7 years), with sig- nificant difference only between the first and the last groups (P = 0.01) (Table 2).

The family history of medical disorders and concomi- tant medical disorders were significantly more frequent in obese patients (41.7% for the two) than other groups.

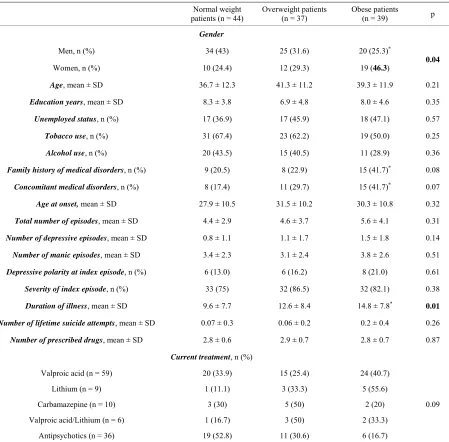

Table 1. Subject characteristics.

Men (n = 79) Women (n = 41) P Total population (n = 120)

Characteristics

Age (years) 39.6 ± 10.9 39.3 ± 13.7 0.24 39.5 ± 11.9

BMI (kg /m²)

<25, n (%) 34 (43) 10 (24.4) 44 (36.7)

[25-30], n (%) 25 (31.6) 12 (29.3) 37 (30.8)

≥30, n (%) 20 (25.3) 19 (46.3)

0.04

39 (32.5)

Education years, mean ± SD 8.2 ± 3.9 7.1 ± 5.3 0.23 7.8 ± 4.4

Unemployed status, n (%) 25 (31.6) 26 (63.4) 0.001 51 (42.5)

Family history of medical disorders, n (%) 19 (24.1) 13 (31.7) 0.36 32 (26.7)

Concomitant medical disorders, n (%) 26 (32.9) 11 (26.8) 0.54 37 (30.8)

Age at onset, mean ± SD 30.3 ± 9.9 29.1 ± 11.7 0.58 29.9 ± 10.5

Total number of episodes, mean ± SD 5.1 ± 3.3 4.4 ± 4.1 0.30 4.9 ± 3.6

Number of depressive episodes, mean ± SD 1.0 ± 1.3 1.3 ± 1.9 0.49 1.1 ± 1.5

Number of manic episodes, mean ± SD 3.8 ± 2.3 2.8 ± 2.6 0.04 3.4 ± 2.4

Depressive polarity at index episode, n (%) 13 (16.5) 8 (19.5) 0.67 21 (17.5)

Severity of index episode, n (%) 65 (87.8) 32 (82.1) 0.40 97 (80.8)

Duration of illness, mean ± SD 12.6 ± 7.9 11.8 ± 8.7 0.58 12.3 ± 8.2

Number of lifetime suicide attempts, mean ±SD 0.09 ± 0.29 0.10 ± 0.30 0.89 0.09 ± 0.30

Number of prescribed drugs, mean ± SD 2.9 ± 0.5 2.8 ± 0.8 0.42 2.8 ± 0.6

Tobacco use, n (%) 72 (91.1) 1 (2.4) 0.001 73 (60.8)

Alcohol use, n (%) 45 (57) 1 (2.4) 0.001 46 (38.3)

Current treatment

Mood stabilizers, n (%) 59 (74.7) 25 (61) 84 (70)

Valproic acid, n (%) 41 (51.9) 18 (43.9) 59 (49.2)

Lithium, n (%) 6 (7.6) 3 (7.3) 9 (7.5)

Carbamazepine, n (%) 7 (8.9) 3 (7.3) 10 (8.3)

Valproic acid/Lithium, n (%) 5 (6.3) 1 (2.4) 6 (5)

Antipsychotics, n (%) 20 (25.3) 16 (39)

0.57

36 (30)

No significant difference was found between study groups for age at onset, the total number of episodes, number of manic episodes, severity of index episode and the number of lifetime suicide attempts.

The study of the therapeutic characteristics showed that was no significant difference in the study groups for the type of medication uses and the number of prescribed drugs. However, obesity and overweight were more fre- quent (76.3% and 48.6%; respectively) in patients taking valproic acid or lithium (Table 2).

4. Discussion

Our study showed that the prevalences of obesity and overweight in bipolar I patients were respectively 32.5% and 30.8%. These findings were similar to those reported by Elmslie et al. (2000) and Fagiolini et al. (2002) (36% and 32%) [14,15]. However, higher values were reported by McElroy et al. (2004) (44% and 20%) [16]. Addition-ally, the prevalenceof obesity greatly exceeded that found

Table 2. Differences in demographic, clinical and therapeutic characteristics between obese, overweight and neither obese or overweight patients.

Normal weight patients (n = 44)

Overweight patients (n = 37)

Obese patients

(n = 39) p

Gender

Men, n (%) 34 (43) 25 (31.6) 20 (25.3)*

Women, n (%) 10 (24.4) 12 (29.3) 19 (46.3) 0.04

Age, mean ± SD 36.7 ± 12.3 41.3 ± 11.2 39.3 ± 11.9 0.21

Education years, mean ± SD 8.3 ± 3.8 6.9 ± 4.8 8.0 ± 4.6 0.35

Unemployed status, n (%) 17 (36.9) 17 (45.9) 18 (47.1) 0.57

Tobacco use, n (%) 31 (67.4) 23 (62.2) 19 (50.0) 0.25

Alcohol use, n (%) 20 (43.5) 15 (40.5) 11 (28.9) 0.36

Family history of medical disorders, n (%) 9 (20.5) 8 (22.9) 15 (41.7)* 0.08

Concomitant medical disorders, n (%) 8 (17.4) 11 (29.7) 15 (41.7)* 0.07

Age at onset, mean ± SD 27.9 ± 10.5 31.5 ± 10.2 30.3 ± 10.8 0.32

Total number of episodes, mean ± SD 4.4 ± 2.9 4.6 ± 3.7 5.6 ± 4.1 0.31

Number of depressive episodes, mean ± SD 0.8 ± 1.1 1.1 ± 1.7 1.5 ± 1.8 0.14

Number of manic episodes, mean ± SD 3.4 ± 2.3 3.1 ± 2.4 3.8 ± 2.6 0.51

Depressive polarity at index episode, n (%) 6 (13.0) 6 (16.2) 8 (21.0) 0.61

Severity of index episode, n (%) 33 (75) 32 (86.5) 32 (82.1) 0.38

Duration of illness, mean ± SD 9.6 ± 7.7 12.6 ± 8.4 14.8 ± 7.8* 0.01

Number of lifetime suicide attempts, mean ± SD 0.07 ± 0.3 0.06 ± 0.2 0.2 ± 0.4 0.26

Number of prescribed drugs, mean ± SD 2.8 ± 0.6 2.9 ± 0.7 2.8 ± 0.7 0.87

Current treatment, n (%)

Valproic acid (n = 59) 20 (33.9) 15 (25.4) 24 (40.7)

Lithium (n = 9) 1 (11.1) 3 (33.3) 5 (55.6)

Carbamazepine (n = 10) 3 (30) 5 (50) 2 (20)

Valproic acid/Lithium (n = 6) 1 (16.7) 3 (50) 2 (33.3)

Antipsychotics (n = 36) 19 (52.8) 11 (30.6) 6 (16.7)

0.09

*Significant difference between obese and normal weight patients (p < 0.05).

Obesity in patients with bipolar I disorder thus consti- tutesa major public health problem and suggests that the development and testing of specific interventions that target the obesityepidemic in this particular population are urgently needed.Bipolar disorder and obesity both have a tremendous impact onthe physical and mental well-being of affected individuals. Therefore, both ill- nesses should be treated with a coordinatedintensive and multifaceted treatment [18].

Moreover, these results could be one of the missing factors in understanding the relationship between psychi- atric disorders and increased cardiovascular risk. In fact, some studies have reported that psychiatric disorders,

is synthesized by adipocytes, regulates appetite and body weight by activating leptin receptors in the satiety center of the hypothalamus. Adiponectin a hormone that plays a significant role in regulating insulin sensitivity is reduced in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Adiponectin is involved in lipid and glucose metabolism and insulin resistance. Administration of recombinant adiponectin stimulates glucose uptake and lipid oxidation in muscles while re- ducing lipid uptake and glucose synthesis in the liver, and increases the overall insulin resistance. In addition to these effects, adiponectin acts as an anti-inflammatory factor and reduces the risk of atherosclerosis, hyperten- sion and coronary heart disease. Excess body fat, par- ticularly abdominal visceral lipid deposition, is frequently accompanied by hypoadiponectinemia, which mediates the relationship between obesity and atherosclerotic vas- cular diseases [20,21].

Obesity was more frequent in women than men. These results are in consistent with the Wang et al. (2006) and McIntyre et al. (2006) studies [22,23]. In addition, this finding could be related to lack of exercise in women, indeed, we showed that approximately 60% of them were unemployed.

Our study showed that men were so much more likely to be smokers and alcoholic consumers than women. These results were in agreement with those reported by previous studies [19,24].

In addition, men have the highest number of manic episodes. This confirms the higher risk of cardiovascular diseases in men compared with women. In fact, previous studies suggested that mania, either directly (through factors intrinsic to illness) or indirectly (through other mediators or associated variables), increased the risk of cardiovascular disease [25].

No significant association was observed between obe- sity or overweight and age, year number of education, the employment status, tobacco status, and alcohol use. These results are in consistent with those reported by Fagiolini et al. (2002) [15]. In contrast, other studies showed that obesity had psychosocial consequences, including dis- crimination and stigmatization in multiple areas of daily life, such as health care, education and employment.

The study of clinical characteristics showed that the number of previous depressive episodes was higher in obese and in overweight patients than normal patients. Additionally, the depressive polarity at index episode was also more frequent in obese and overweight patients than the other group. Previous studies reported that patients who had depressive symptomatology were more likely to have excessive caloric and cholesterol intake, to smoke and to be inactive than non-depressed subjects. Another explanation might involve biological mechanisms: it is ascertained that hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis dysregulation and high cortisol blood levels lead to

increasing visceral fat. HPA axis dysregulation has been a common finding in both unipolar and bipolar disorders; recently, some studies reported that increased cortisol blood levels correlated to the amount of intra-abdominal fat in major depression [26].

In addition, we showed that the duration of disease was longer inobese and in overweight patients than in those with normal weight. This could confirm the effect of bipolar disorder on the weight gain.

The family history of medical disorders and concomi- tant medical disorders was significantly more frequent in obese patients than in those with normal weight. Our findings are in agreement with previous studies [16,23, 27].

No significant difference was found between study groups for age at onset, the total number of episodes, severity of index episode and the number of lifetime sui- cide attempts. These results are in part in consistent with the Maina et al. (2008) study [26]. In contrast, Fagiolini et al. (2002) [15] showed that appetite, diet and energy ex- penditure are greatly influenced by both the polarity and acuity of an episode. Obesity may contribute to the se- verity of bipolar disorder by negatively impacting pa- tients’ general physical health and functioning, quality of life, self-esteem, and psychological well-being. Obese patients have an increased risk of sleep apnea, which causes sleep disruptions and may lead to mood destabili- zation in patients with bipolar disorder [18,28,29].

Additionally, no significant difference was found be- tween study groups for a number of manic episodes. Our findings are in agreement with those reported by Fagiolini

et al. (2003) [18].

About therapeutic characteristics, we found that obe- sity and overweight were more frequent (76.3% and 48.6%; respectively) in patients taking valproic acid or lithium. These findings are in line with those reported by De Hert et al. (2011) [8]. Moreover, Casey et al. (2005) [9] reported that lithium have been shown to stimulate appetite through different mechanisms. The “carbohy- drate craving” that is thought to be one of the mecha- nisms of increased calorie intake in people taking lithium is well known. In addition, it is believed that valproate also stimulates weight gain through a variety of mecha- nisms, especially the development of insulin resistance and diabetes mellitus type. Valproic acid also decreases leptin secretion and mRNA levels in adipocytes in vitro, suggesting that valproic acid therapy may be associated with altered leptin homeostasis contributing to weight gain in vivo [30,31].

over, the family history of medical disorders and con- comitant medical disorders were significantly more fre- quent in obese patients than in those with normal weight. However, any significant association between therapeutic characteristics and obesity or overweight was found. These results emphasize the need for specific treatment strategies and programs for weight control for these pa- tients. Ideally, diet and exercise counselling should be provided to all bipolar disorder patients-before weight gain and definitely provided once weight gain has oc- curred. Exercise, diet, and individual or group behavioral therapy are the principal nonpharmacological means for inducing and maintaining weight loss. However, these may be particularly difficult to implement in individuals suffering from mood disorders.

5. Acknowledgements

The authors thank the patients and control subjects for their assistance in this study.

REFERENCES

[1] F. Marmol, “Lithium: Bipolar Disorder and Neurodegen- erative Diseases Possible Cellular Mechanisms of the Therapeutic Effects of Lithium,” Progress in Neuro-Psy- chopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry, Vol. 32, No. 8, 2008, pp. 1761-1771. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2008.08.012 [2] G. E. Simon, “Social and Economic Burden of Mood

Disorders,” Biological Psychiatry, Vol. 54, No. 3, 2003, pp. 208-215. doi:10.1016/S0006-3223(03)00420-7 [3] H. U. Wittchen, S. Muhlig and L. Pezawas, “Natural

Course and Burden of Bipolar Disorders,” The Interna- tional Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology, Vol. 6, No. 2, 2003, pp. 145-154. doi:10.1017/S146114570300333X [4] S. W. Woods, “The Economic Burden of Bipolar Dis-

ease,” Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, Vol. 61, 2000, pp. 38-41.

[5] A. Ezzaher, D. Haj Mouhamed, A. Mechri, F. Neffati, W. Douki, L. Gaha and M. F. Najjar, “Association between Bipolar I Disorder and the L55M and Q192R Polymor- phisms of the Paraoxonase 1 (PON1) Gene,” Journal of Affective Disorders, Vol. 139, No. 1, 2012, pp. 12-17. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2011.06.029

[6] D. A. Revicki, L. S. Matza, E. Flood and A. Lloyd, “Bi- polar Disorder and Health-Related Quality of Life: Re- view of Burden of Disease and Clinical Trials,” Pharma- coeconomics, Vol. 23, 2005, pp. 583-594.

doi:10.2165/00019053-200523060-00005

[7] R. J. Wyatt and I. Henter, “An Economic Evaluation of Manicdepressive Illness: 1991,” Social Psychiatry and Psy- chiatric Epidemiology, Vol. 30, No. 5, 1995, pp. 213-219. [8] M. De Hert, C. U. Correll, J. Bobes, M. Cetkovich-Bak-

mas, D. Cohen, I. Asai J. Detraux, S. Gautam, H. J. Möller, D. M. Ndetei, J. W. Newcomer, R. Uwakwe and S. Leucht, “Physical Illness in Patients with Severe Men- tal Disorders. I. Prevalence, Impact of Medications and

Disparities in Health Care,” World Psychiatry, Vol. 10, 2011, pp. 52-77.

[9] D. E. Casey, “Metabolic Issues and Cardiovascular Dis- ease in Patients with Psychiatric Disorders,” American Journal of Medicine, Vol. 118, 2005, pp. 15-22. [10] S. Malhotra and S. L. McElroy, “Medical Management of

Obesity Associated with Mental Disorders,” Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, Vol. 63, 2002, pp. 24-32.

[11] American Psychiatric Association, “Diagnostic and Sta- tistical Manual of Mental Disorders,” 4 Edition, Ameri- can Psychiatric Association, Washington DC, 2004. [12] World Health Organization, “Obesity: Preventing and

Managing the Global Epidemic (publication WHO/NUT/ NCD/98.1),” WHO, Geneva, 1997.

[13] H. Pijil and A. E. Meinders, “Bodyweight Change as an Adverse Effect of Drug Treatment: Mechanisms and Ma- nagement,” Drug Safety, Vol. 14, 1996, pp. 329-342. doi:10.2165/00002018-199614050-00005

[14] J. L. Elmslie, J. T. Silverstone, J. L. Mann, S. M. Wil- liams and S. E. Romans, “Prevalence of Overweight and Obesity in Bipolar Patients,” Journal of Clinical Psychia- try, Vol. 61, 2000, pp. 179-184.

doi:10.4088/JCP.v61n0306

[15] A. Fagiolini, E. Frank, P. R. Houck, A. G. Mallinger, H. A. Swartz, D. J. Buysse, H. Ombao and D. J. Kupfer, “Prevalence of Obesity and Weight Change during Treat- ment in Patients with Bipolar I Disorder,” Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, Vol. 63, 2002, pp. 528-533.

doi:10.4088/JCP.v63n0611

[16] S. L. McElroy, R. Kotwal, S. Malhotra, E. B. Nelson, P. E. Keck and C. B. Nemeroff, “Are Mood Disorders and Obesity Related? A Review for the Mental Health Profes- sional,” Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, Vol. 65, 2004, pp. 634-651. doi:10.4088/JCP.v65n0507

[17] F. G. Haddad, H. Brax, E. Zein and T. Abou el Hessen, “L’obésité et les Pathologies Associées dans un Centre de Soins au Liban,” Journal Medical Libanais, Vol. 54, 2006, pp. 152-155.

[18] A. Fagiolini, D. J. Kupfer, P. R. Houck, D. M. Novick and E. Frank, “Obesity as a Correlate of Outcome in Pa- tients with Bipolar I Disorder,” American Journal of Medicine, Vol. 160, 2003, pp. 112-117.

[19] M. P. Garcia-Portilla, P. A. Saiz, M. T. Bascaran, S. Mar- tinez, A. Benabarre, P. Sierra, P. Torres, J. M. Montes, M. Bousoño and J. Bobes, “Cardiovascular Risk in Patients with Bipolar Disorder,” Journal of Affective Disorders, Vol. 115, No. 3, 2009, pp. 1-7.

doi:10.1016/j.jad.2008.09.008

[20] A. Ezzaher, D. Haj Mouhamed, A. Mechri, F. Neffati, W. Douki, L. Gaha and M. F. Najjar, “Cardiovascular Risk in Tunisian Patients with Bipolar I Disorder,” Dyslipidemia- From Prevention to Treatment, Rijeka, 2012.

[21] J. Pinkney, “Implications of Obesity for Diabetes and Coronary Heart Disease in Clinical Practice,” Britsh Jour- nal of Diabetes and Vascular Disease, Vol. 1, No. 2, 2001, pp. 103-106. doi:10.1177/14746514010010020701 [22] P. W. Wang, G. S. Sachs, C. A. Zarate, L. B. Marangell, J.

and T. A. Ketter, “Overweight and Obesity in Bipolar Disorders,” Journal of Psychiatric Research, Vol. 40, No. 8, 2006, pp. 762-764.

doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.01.007

[23] R. S. McIntyre, J. Z. Konarski, K. Wilkins, J. K. Soczyn- ska and S. H. Kennedy, “Obesity in Bipolar Disorder and Major Depressive Disorder: Results from a National Community Health Survey on Mental Health and Well- Being,” Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, Vol. 51, No. 5, 2006, pp. 274-280.

[24] P. J. R. Teixeira and F. L. Rocha, “The Prevalence of Metabolic Syndrome among Psychiatric Inpatients in Bra- zil,” Brazilian Journal of Psychiatry, Vol. 29, No. 4, 2007, pp. 330-336.

[25] A. Ezzaher, D. Haj Mouhamed, A. Mechri, F. Neffati, W. Douki, L. Gaha and M. F. Najjar, “Lower Paraoxonase 1 Activity in Tunisian Bipolar I Patients,” Annals of Gen- eral Psychiatry, Vol. 9, 2010, p. 36.

doi:10.1186/1744-859X-9-36

[26] G. Maina, V. Salvi , A. Vitalucci, V. D’Ambrosio and F. Bogetto, “Prevalence and Correlates of Overweight in Drug-Naïve Patients with Bipolar Disorder,” Journal of

Affective Disorders, Vol. 110, No. 1-2, 2008, pp. 149-155. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2007.12.233

[27] A. J. Stunkard, M. S. Faith and K. C. Allison, “Depres- sion and Obesity,” Biological Psychiatry, Vol. 54, No. 3, 2003, pp. 330-337. doi:10.1016/S0006-3223(03)00608-5 [28] G. Cheymol, “Effects of Obesity on Pharmacokinetics

Implications for Drug Therapy,” Clinical Pharmacokinet- ics, Vol. 39, No. 3, 2000, pp. 215-231.

doi:10.2165/00003088-200039030-00004

[29] D. T. Plante and J. W. Winkelman, “Sleep Disturbance in Bipolar Disorder: Therapeutic Implications,” American Journal of Psychiatry, Vol. 165, No. 7, 2008, pp. 830-843. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08010077

[30] A. Ezzaher, D. Haj Mouhamed, A. Mechri, F. Neffati, W. Douki, L. Gaha and M. F. Najjar, “Obesity and Dyslipi- demia in Tunisian Bipolar Subjects,” Annales de Biologie Clinique, Vol. 68, 2010, pp. 277-284.

[31] D. C. Lagace, R. S. Mcleod and M. W. Nachtigal, “Val- proic Acid Inhibits Leptin Secretion and Reducesleptin Messenger Ribonucleic Acid Levels in Adipocytes,” En- docrinology, Vol. 145, No. 12, 2004, p. 5493.