1

THE LONDON SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS AND POLITICAL SCIENCE THE SOCIAL CONTEXT OF BUSINESS AND THE TAX SYSTEM IN NIGERIA:

THE PERSISTENCE OF CORRUPTION

MICHAEL OGHENEVO OVIE AKPOMIEMIE

A thesis submitted to the Department of Law of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy

2

Declaration

I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the PhD degree of the London

School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work.

The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that

full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written

consent.

I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any

third party.

3

Abstract

This thesis examines the means by which corruption sustains itself in the relationship between

business and the tax system. It is predicated on a desire to understand the possibility of

sheltering the relationship from corruption and other similar societal challenges. It relies on the

intuition that certain structural elements of this relationship permit the infiltration and

sustenance of corruption. With the aid of both qualitative and quantitative data obtained from

empirical research in Nigeria, it constructs a model that exposes these structural elements.

This thesis argues that a ‘two-way relationship’ between businesses and the tax system

not only exists but is anchored in the interaction between the actors (businesses, tax

policy-makers, tax law-policy-makers, tax administrators and tax arbiters) that represent both institutions. It

explores four mechanisms (‘access’, ‘awareness’, ‘distortion’ and ‘inaction’) that affect the

interaction and consequently the relationship between business and the tax system.

It also addresses the difficulty in defining corruption by adopting a process definition

of this phenomenon. In this definition, the tag ‘corruption’ applies where an act or state of

affairs and the gain derived therefrom breach the expectations of the legal, economic, political

or moral dimension of a given society.

This thesis then argues that corruption sustains itself in the two-way relationship by

exploiting a ‘power gap’ between the actual and institutional powers of actors in the said

relationship. It defines the ‘institutional power of actors’ as that which accords with the

institutional limits of their social setting. An actor’s ‘actual power’, in contrast, refers to that

which the actor may exercise in any given circumstance.

This power gap is potentially increased or decreased by the levels of the four

mechanisms in the relationship. Therefore, any real effort to tackle corruption in the

relationship between businesses and the tax system must seek to address these four mechanisms

in a manner that limits the power gap and opportunities for corruption.

The concept of the power gap and its four mechanisms is a novel approach to

understanding and tackling corruption. It aspires to support the design of tax systems with the

capacity to adequately balance competing interests, especially in countries where corruption is

4

Acknowledgements

This thesis would never have seen the light of day without the assistance of family, friends and

most importantly my supervisors. I thank my mum who has stood by me all through my

education. Without her consistent encouragement, love and dedication, I would be nowhere.

Although my Dad did not live long enough to see me complete this process, I am confident

that, wherever he is, he is proud that I have come this far. I have countless friends who have

contributed in different ways to the completion of this project. I am sure that they are in as

much of a celebratory mood as I am.

My supervisors, Ian and Eduardo, have been brilliant all through the process. Unlike

me, they never lost faith in my ability to complete this task. Finally, I want to thank the LSE

and Chartered Institute of Taxation who provided funding for my project. I pray that they

5

Table of Contents

Declaration ... 2

Abstract ... 3

Acknowledgements ... 4

Table of Contents ... 5

THE SOCIAL CONTEXT OF BUSINESS AND THE TAX SYSTEM IN NIGERIA: ‘THE PERSISTENCE OF CORRUPTION’ – INTRODUCTORY CHAPTER ... 9

1.1 Introduction ... 9

1.2 The Two-Way Relationship ... 11

1.3 Actor Network Theory as the Theoretical Approach ... 12

1.4 The Influence of New Institutional Sociology ... 13

1.5 Why Corruption? ... 14

1.5.1 Nature and Forms of Corruption ... 16

1.5.2 Impact of Corruption... 19

1.6 The Formulation of Tax Policies and Enactment of Laws ... 20

1.7 Administration of Tax Policies and Laws ... 21

1.8 Resolution of Tax Disputes ... 22

1.9 The Interaction between the Terminals ... 24

1.10 Methodology ... 26

1.11 Nigeria as the Case Study ... 28

1.12 A Synopsis of the Thesis ... 31

1.13 Conclusion ... 34

CHAPTER 2 THE TWO-WAY RELATIONSHIP AND THE FOUR MECHANISMS ... 35

2.1 Introduction ... 35

2.2 Understanding the Communication Link ... 38

2.2.1 The Communication Route ... 41

2.2.2 Communications as Evidence of Power ... 45

2.3 Forms of Communication... 45

2.4 Purpose of Communication ... 46

2.5 Channels of Communication ... 48

2.6 Actors, Interests and Instruments ... 49

2.6.1 Businesses ... 49

2.6.2 Associations and Professionals ... 52

6

2.6.4 Civil/Public Servants ... 54

2.6.5 Ministers/Representatives of Government ... 55

2.6.6 Tax Law-Makers ... 57

2.6.7 Tax Administrators/Officials ... 59

2.6.8 Arbiters... 61

2.6.9 Other Actors ... 65

2.7 Applying Actor Network Theory ... 66

2.7.1 Actor Network Theory ... 67

2.7.2 Actor Network Theory and the Communication Link ... 69

2.8 Issues Affecting the Communication Link ... 71

2.8.1 Distortion of Communications ... 71

2.8.2 Deficiency in Awareness ... 76

2.8.3 Restriction of Access ... 79

2.8.4 Inaction ... 82

2.9 Conclusion ... 83

CHAPTER 3 THE POWER GAP, CORRUPTION AND THE FOUR MECHANISMS ... 85

3.1 Introduction ... 85

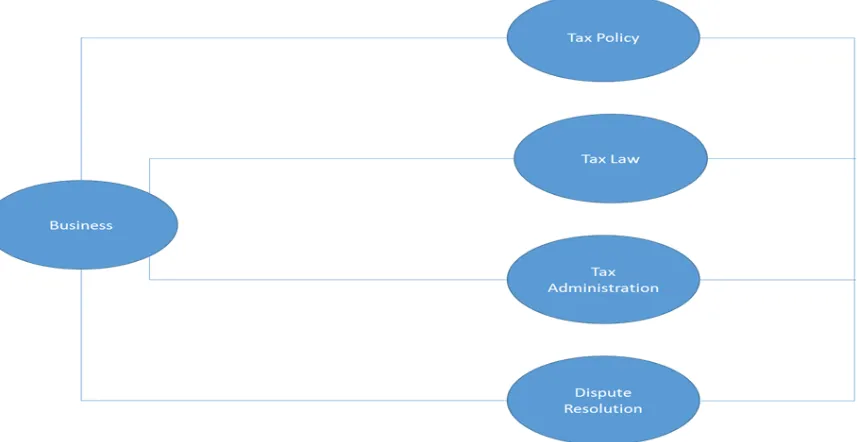

Figure 1 Communication Link ... 85

3.2 Institutional Limits to Communicative Actions ... 86

3.2.1 Origin and Evolution of Rules, Expectations and Dimensions ... 87

3.2.2 Rules, Actors and Expectations ... 90

3.2.3 Legality of Communicative Actions ... 92

The Petroleum Investment Allowance dispute ... 97

3.3 The Power Dynamics in the Two-Way Relationship ... 101

3.3.1 Understanding Power ... 102

Permutations of the exercise of power ... 109

3.3.2 The Power Gap ... 111

3.4 Understanding Corruption: A Process Definition... 115

3.4.1 Abuse of Power ... 118

3.4.2 Corrupt Gain ... 126

3.5 Corruption and the Power Gap ... 129

3.5.1 Corruption and the Expectations of the Dimension ... 129

3.5.2 Corruption and Social Expectations ... 130

7

3.6 Conclusion ... 132

CHAPTER 4 THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN BUSINESS AND THE TAX SYSTEM: EMPIRICAL RESEARCH FINDINGS (1) ... 133

4.1 Introduction ... 133

4.2 Maintaining a Good Relationship... 133

4.3 Small Businesses vs Large/Multinational Businesses ... 135

4.4 The Tax Law Terminal ... 141

4.5 The Dispute Resolution Terminal ... 146

4.5.1 Independence and Objectivity of the Tax Appeal Tribunal ... 147

4.5.2 Tax Expertise of Judges/Commissioners ... 148

4.5.3 Legality of the Tax Appeal Tribunal ... 150

4.6 Undue Delays ... 152

4.7 Tax Administration and Tax Policy-Making ... 154

4.8 Third Party Organisations ... 160

4.9 Conclusion ... 162

CHAPTER 5 CORRUPTION AND THE TWO-WAY RELATIONSHIP EMPIRICAL RESEARCH FINDINGS (II) 163 5.1 Introduction ... 163

5.2 Revisiting the Meaning of Corruption ... 163

5.2.1 Expectations of the Economic Dimension ... 164

5.2.2 Expectations of the Legal Dimension ... 165

5.2.3 Expectations of the Moral Dimension ... 166

5.3 Corruption in the Two-Way Relationship ... 167

5.4 Corruption in the Tax Administration Terminal ... 171

5.5 Corruption and Protest Mechanisms ... 174

5.6 The Role of Businesses in Tackling Corruption ... 180

5.7 Conclusion ... 181

CHAPTER 6 THE LAW, CORRUPTION AND THE TWO-WAY RELATIONSHIP ... 183

6.1 Introduction ... 183

6.2 The Direct Impact of the Law on Corruption ... 183

6.3 The Indirect Impact of Law on Corruption in the Two-way Relationship ... 189

6.3.1 Awareness ... 189

6.3.2 Access ... 192

6.3.3 Distortion of Communication ... 195

8

6.4 Conclusion ... 197

CHAPTER 7 SHIFTING THE FOCUS TO THE POWER GAP AND ITS MECHANISMS: CONCLUDING CHAPTER ... 199

7.1 Introduction ... 199

7.2 Shifting the Focus? ... 199

7.2.1 Monopoly ... 199

7.2.2 Discretion ... 200

7.2.3 Transparency ... 202

7.2.4 Accountability ... 203

7.3 Further Research ... 203

7.4 Conclusion ... 206

Appendices ... 208

Table of Cases ... 230

Table of Legislation and Conventions ... 232

Bibliography ... 233

Books, Book Chapters and Reports ... 233

9

THE SOCIAL CONTEXT OF BUSINESS AND THE TAX SYSTEM IN NIGERIA: ‘THE PERSISTENCE OF CORRUPTION’ – INTRODUCTORY CHAPTER

1.1 Introduction

As the world recovers from the recent economic downturn, and given that revenues from the

exploitation of natural resources remain volatile, developed and developing countries are

increasingly prioritising the need to encourage, attract and sustain private sector investments.

The motivation for this are the benefits that increased or sustained investments may yield.

These benefits include a reduction in the level of unemployment; an increase in technology

transfer; the improvement of infrastructure; and, in time, an increase in government revenue.

The ability of a polity to encourage, attract and sustain investments largely depends on

it possessing the ‘right investment climate’.1 This in turn depends on several factors such as nearness to market, level of infrastructure, availability of qualified pool of labour, access to

raw materials and government policy.

One form of government policy which has attracted a considerable amount of interest

from academics and policy-makers is taxation. Governments of both developed and developing

countries try to use their tax systems to improve their investment climate. This usually involves

striking a balance, at least in the short run, between investments and the primary revenue

generation role of the tax system. Irrespective of the structure and contents of the tax system,

whether the right balance will be struck inevitably depends on the actions or responses of the

vehicles behind private sector investments (i.e. businesses).

Businesses, for their part, passively and actively play a role in directing the attempts by

States to improve their investment climate via their tax systems. Through their interactions

with the arms of government, businesses endeavour to steer the tax system in a direction

conducive to the achievement of their individual and collective goals. The success of such

endeavours depends on how they are perceived and responded to by the tax system.

1 For a survey of businesses about factors that affect the investment climate of a given state, see Geeta Batra,

Daniel Kaufmann and Andrew H Stone, Investment Climate Around the World: Voices of the Firms from the

10

Even without a deliberate attempt by one institution to influence the other, the goals of

business and the tax system are such that a state of constant interactions between both

institutions in a modern society is the norm. These interactions form the basis of an important

relationship between business and the tax system. This relationship is, however, susceptible to

the vagaries of the societal factors that pervade polities. One societal factor – corruption – has

the potential to alter the dynamics of this relationship owing to its ability to determine the

nature, frequency, context, goals and results of the interactions between business and the tax

system. Corruption is widely believed to be detrimental to both this relationship and the general

fabric of society. Despite wide condemnation across societies, corruption still persists,

especially in the relationship between business and the tax system.

This research is therefore born out of a desire to understand the mechanisms through

which corruption sustains itself in the relationship between business and the tax system. In

arriving at the research question, the relationship between business and the tax system was

artificially separated from its harbouring society so as to inquire whether this relationship can

be cocooned from the vices in its site of existence.

One may imagine the relationship as a container floating in polluted waters (that is, a

corruption-infested society). One may then ask: what structural features of this container may

prevent it from being infiltrated by the polluted waters? What aspects of this container make

infiltration by the polluted waters possible? In line with this analogy, my research question is:

what aspects of the relationship between business and the tax system does corruption exploit

in order to sustain itself in the said relationship? What structural features of this relationship

may prevent or reduce infiltration by corruption? To answer this question, I conducted an

empirical study of the relationship between business and the tax system in Nigeria, where

corruption is reputedly rife.

Following this study, my central argument is that corruption remains a part of the

relationship between business and the tax system by exploiting a ‘power gap’. This refers to

the gap between the institutional and the actual powers of actors in the relationship. This power

gap is increased or decreased by the levels of four mechanisms (‘access’, ‘awareness’,

‘distortion’ and ‘inaction’). Therefore, any comprehensive attempt to address corruption in the

relationship between business and the tax system must tackle the levels of these four

mechanisms so as to reduce the power gap and opportunities for corruption in the said

relationship. This argument is supported by a descriptive analysis of data obtained from the

empirical research in Nigeria.

11

1.2 The Two-Way Relationship

In order to construct a firm foundation for answering the research question, this thesis critically

examines the relationship between business and the tax system.

The term ‘tax system’ in this research refers to the entire machinery used by

government to generate tax revenue. It comprises rules, policies, institutions and persons.

Equating the tax system with the tax administration alone would shield this research from the

analysis of important interactions that take place during the formulation of tax instruments and

the resolution of tax disputes. Focusing only on policies, laws and regulations, and thus leaving

out the institutions and processes by which they are formed, also suffers from the same

weakness. The term ‘tax system’ is given a broad meaning to enable proper analysis of the core

question of this research.

However, defining the tax system as a machinery of government excludes business (and

other taxpayers) from its purview. This restriction is apt due to the nature of this research. This

is because by separating business from the tax system, it enables the proper analysis of the

interactions between both institutions.

In this thesis, I will argue that the relationship between business and the tax system is

a product of the interactions that take place in four key ‘terminals of the tax system’. I have

named these terminals to signify the fact that the interactions between business and the tax

system through which both institutions receive information take place at these locations. These

terminals, named according to their output, are the ‘tax policy terminal’, ‘tax law (statute)

terminal’, ‘tax administration terminal’ and ‘dispute resolution terminal’. Reference to these

terminals rather than to the arms of government (executive, legislature and court/judiciary) is

due to two main reasons. Firstly, it enables the research to focus only on the relevant aspects

of these arms of government. Secondly, the customary appellations do not adequately describe

the various functions performed in the tax system. The courts (judiciary), for example, may not

be the only institution charged with the responsibility to resolve disputes. Therefore, using the

term court/judiciary in place of the term dispute resolution terminal will be unduly limiting.

I will also contend that business and the tax system partake in a two-way relationship

in which each institution has the potential to influence the operations of the other. The tax

system, on the one hand, may influence the levels of investments, location of investments, the

12

compliance and other operations of businesses.2 Business, on the other hand, may exert political, practical and judicial influence on the tax rates, the tax rules, tax administration and

other facets of the tax system.3

1.3 Actor Network Theory as the Theoretical Approach

In order to understand how corruption may sustain itself in the relationship between business

and the tax system, it is important to look beyond businesses and the terminals of the tax system

and identify other less conspicuous actors that may play a role in this relationship.

I apply ‘Actor-Network Theory’ (ANT) in order to achieve this task. With this, I argue

that the relationship between the tax system and a business or group of businesses at any given

point in time is the product of ‘a network of human and non-human actors’.4 This network is ‘transient’ and ‘heterogeneous’ in nature.5 This implies that the actors that form the network

are varied and constantly changing. The network is also unstable and may collapse with the

loss of an important actor.6

The durability of the relationship between the tax system and a particular business or

group of businesses depends on the nature of the actors that comprise this network or, to put

differently, it depends on the materials of this network or relationship.7 These actors have their private interests. The existence of these private interests may lead to conflict and consequently

the disintegration of the entire network if these interests are not properly managed.8

2 For a general review of the impact of the tax system on the decisions of businesses, see Michael P Devereux,

‘The Impact of Taxation on the Location of Capital, Firms and Profit: A Survey of Empirical Evidence’ (Oxford University Centre for Business Taxation, Working Paper No 07/02, April 2006)

<http://eureka.sbs.ox.ac.uk/3395/1/WP0702.pdf> accessed 5 July 2015; See also James Hines, ‘Tax Policy and the Activities of Multinational Corporations’ (NBER Working Paper No 5589, 1996)

<https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4609> accessed 5 July 2015, in which the author analysed existing (US-related) research which suggests that taxation influences FDI, corporate borrowing, transfer pricing, dividend and royalty payments, research and development activity, exports, bribe payments and location decisions.

3 On the power of businesses to influence government on matters pertaining to taxation, see Dennis P Quinn and

Robert Y Shapiro, ‘Business Political Power: The Case of Taxation’ (1991) 85(3) American Political Science Review851.

4 See Bruno Latour, Science in Action: How to Follow Scientists and Engineers Through Society (Oxford

University Press 1987); John Law, ‘Notes on the Theory of the Actor-Network: Ordering and Strategy and Heterogeneity’ (1992) 5 Systems Practice 379.

5 Law (n 4).

6 ibid.

7 ibid.

13

Therefore, the classification of the relationship between the tax system and a business

as one of compliance,9 for example, can only be temporary. Understanding the state (the durability) of this network will require identifying and examining the actors that constitute it,

their private interests and the process by which they were co-opted or enrolled into the said

network. It is also important to understand how the potentially conflicting interests of the

different actors are controlled so as to prevent the breakdown of the entire network.10

In sum, ANT uncovers certain less conspicuous actors in the two-way relationship. It

also provides a framework through which these actors (in particular, corruption) may be

examined so as to understand their individual and collective impact on the relationship between

business and the tax system. ANT also encourages the conducting of an empirical study11 of these actors using a qualitative methodology12 which is in keeping with this research.

1.4 The Influence of New Institutional Sociology

Although ANT is the main theoretical approach adopted in this thesis, it is pertinent to

acknowledge the influence of ‘New Institutional Sociology’ (NIS) as well. NIS influenced the

analysis of the behavioural dynamics behind the responses of the terminals of the tax system

and business to the interactions that take place via the communication link.

The use of NIS is not without the challenges associated with a theory that has been

subject to different interpretations within and across academic fields. The elusiveness of its

core concept of ‘institution’ or ‘institutional environment’ from comprehensive definition

threatens to deprive the entire theory of validity On the meaning of institution, for example,

Williamson remarked in 2000 that ‘we are still very ignorant about institutions’.13

Nevertheless, NIS’ recognition of the imperfections of the decision frame of actors, the

contextual nature of their interests, the duality of their relationship with their institutional

environment, and diverse instruments of influence14 make it a suitable tool for elucidating the

9 See Karen Boll, ‘Taxing Assemblages: Laborious and Meticulous Achievements of Tax Compliance’ (PhD

Thesis, IT University of Copenhagen 2011).

10 Law (n 4).

11 See Bruno Latour, Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network Theory (Oxford University

Press 2005).

12 See John Roberts, ‘Poststructuralism against Poststructuralism: Actor-Network Theory, Organisations and

Economic Markets’ (2012) 15 European Journal of Social Theory 35, 41.

13 Oliver Williamson, ‘The New Institutional Economics: Taking Stock, Looking Ahead’ (2000) 38 Journal of

Economic Literature 595; See also Douglas North, ‘Institutions’ (1991) 5 Journal of Economic Perspectives 97, 111; Douglas North, ‘Institutions and Credible Commitment’ (1993) 149 Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics11.

14 Paul J DiMaggio and Walter W Powell, ‘The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism And Collective

14

rationality of the operations of the actors in the two-way relationship. NIS postulates that the

interactions between actors and their institutional environment give rise to certain social

expectations which influence the structure, decision frame and actions of these actors as well

as shape the existing institutional environment.15 It suggests a two-way relationship of influence between an actor and its institutional environment, which aligns with the

understanding of the relationship between business and the tax system in this thesis.

1.5 Why Corruption?

There is hardly another phenomenon that remains as highly relevant to modern societies as

corruption does. Its existence can be traced as far back as Babylon16 in the 22nd century BC, Egypt17 and India18 in the 14th century BC, and the biblical stories of Luke.19

In the contemporary world, while corruption is usually discussed as a problem of

developing countries, it remains a problem in their developed counterparts.20 This is because the development or modernisation of a country does not eradicate corruption; corruption

merely adapts to the changed circumstances.21 Corruption exists in all forms of government, albeit at different levels of pervasiveness.22 Amongst states with similar socio-economic structures, the levels of corruption may also differ.23 However, statistics show that poorer countries or areas are likely to be more corrupt.Lipset, for example, argues that the levels of

corruption are higher in areas with low levels of education and income.24 This may not be unconnected with the fact that corruption allegedly thrives on financial, social and mental

poverty, and opportunity. However, other researchers point out the lack of clarity over whether

corruption increases poverty or poverty increases corruption due to the inability of poor

countries to fight corruption. For instance, Gupta and others argue that corruption increases

15 ibid.

16 Law Code of Hammurabi, King of Babylon.

17 Great Edict of Horemheb, King of Egypt.

18 Kautilya’s Arthashastra.

19 Such as the stories of Zacchaeus the tax collector (Luke 19:8) and the parable of the unjust steward (Luke

16:3-8).

20 Carl J Friedrich, Man and his Government (New York 1963) 167.

21 See John Girling, Corruption, Capitalism and Democracy (Routledge 1997).

22 See Carl J Friedrich, The Pathology of Politics: Violence, Betrayal Corruption, Secrecy and Propaganda

(Harper & Row 1972) 128.

23 See Jens Chr. Andvig and Karl Ove Moene, ‘How Corruption May Corrupt’ (1990) 13 Journal of Economic

Behavior & Organization 63; Francis T Lui, ‘A Dynamic Model of Corruption Deterrence’ (1986) 31 Journal of Public Economics 1.

24 See Seymour Lipset, Political Man: The Social Bases of Politics (John Hopkins University Press 1981);

15

poverty.25 For his part, Husted points out that some countries may simply lack the resources to tackle corruption adequately.26 Some have described the relationship between corruption and poverty as a two-way relationship.27 Research has shown a negative correlation between corruption and economic development.28 Research also shows that corruption and human development influence each other.29 In general, some causes of corruption are weak institutions

that allow for wide discretionary powers, poor internal control and detection mechanisms, poor

wages and working conditions of staff, and political interference in bureaucracy and culture.30

From an extensive list of societal factors, corruption was picked for consideration in

this thesis for two main reasons. The first and well recognised reason is the importance of

corruption and its impact on the ability of modern states to achieve their goals. The second

reason is the seeming affinity between corruption and tax compliance. Both refer to the extent

to which an act accords with certain expectations in society, albeit that the source and value of

expectations regarding corruption are more likely to be contested. To the extent that both

corruption and non-compliance are punishable legal, moral or economic wrongs, their likely

occurrence, from an economic perspective, can be surmised as dependent on a comparison of

their uncertain costs and benefits. The costs include the severity of the penalties for both acts

as multiplied by the probability that these penalties will be administered. The benefits include

the tax burden avoided or corrupt gain secured.

In order to give weight to the above reasons, the following subsections discuss the form,

nature and impact of corruption. This discussion assumes a prior understanding of the meaning

of corruption. However, a detailed consideration of the controversy over the definition of

corruption is carried out in Chapter 3. It is sufficient to state at this point that a process

definition of corruption is adopted in this thesis. By this definition, an act will be corrupt where

25 Sanjeev Gupta, Hamid Davoodi and Rosa Alonso-Terme, ‘Does Corruption Affect Income Inequality and

Poverty?’ (International Monetary Fund, IMF WP98/76, May 1998).

26 Bryan W Husted, ‘Wealth, Culture and Corruption’ (1999) 30 Journal of International Business Studies 339,

341-2.

27 Robert E Hall and Charles I Jones, ‘Why Do Some Countries Produce So Much More Output Per Worker

Than Others?’ (1999) 114 The Quarterly Journal of Economics 83; Jakob Svensson, ‘Eight Questions About Corruption’ (2005) 19 Journal of Economic Perspectives 19.

28 Alfredo Del Monte and Erasmo Papagni, ‘The Determinants of Corruption in Italy: Regional Panel Data

Analysis’ (2007) 23 European Journal of Political Economy 379; Ghulam Shabbir and Mumtaz Anwar, ‘Determinants of Corruption in Developing Countries’ (2007) 46(4) The Pakistan Development Review 751.

29 Eleanor RE O’Higgins, ‘Corruption, Underdevelopment, and Extractive Resource Industries: Addressing the

Vicious Cycle’ (2006) 16(2) Business Ethics Quarterly 235.

30 For these and other causes of corruption, see Daniel Treisman, ‘The Cause of Corruption: A Cross-National

Study’ (2000) 76 Journal of Public Economics 399; Susan Rose-Ackerman, Corruption and Government:

16

both the act and the gain derived therefrom breach the ideal expectations of the legal, moral,

economic or other relevant dimension of society.

1.5.1 Nature and Forms of Corruption

This thesis focuses on corruption that may exist in the two-way relationship between business

and the tax system. It recognises that a considerable amount of corruption may exist solely

within the tax system or solely within business. These may have an indirect effect on the

relationship between business and the tax system but are not central to this thesis. Three forms

of actions are identifiable as constituting corruption in the two-way relationship. These actions

are:

1) the demand for, offer of or receipt of social or economic gain for the performance of

public services that should be provided ordinarily;

2) the demand for, offer of or receipt of social or economic gain for the performance of a

service that should not be provided; and

3) the extortion of social or economic gain from or by businesses.

Some have divided these forms of corruption into two main categories. Langseth and

others, for example, state that corruption can be categorised as either according-to-rule or

against-the-rule. The first and second category involve situations where the service provided

by the official is in accordance with or against the law respectively.31

In this thesis, however, emphasis is placed, not on these aforementioned forms but on

the expectations of actors in the two-way relationship as the barometer for what constitutes

corruption. These expectations are sourced from different ‘dimensions’ (such as economic,

moral or legal dimensions) in society which possess institutional mechanisms through which

they secure compliance with their dictates. Consequently, there can be no fixed and exhaustive

list of forms of corruption. The content of any such list is likely to change as the expectations

of the different dimensions in society change.

Two models have been developed by academics to aid the analysis of corruption. They

are: the principal-agent-client model32 and the collective action model.33 Under the principal-agent-client model,a principal seeking to maintain a relationship with a client but constrained

31 See Petter Langseth, Rick Stapenhurst and Jeremy Pope, ‘The Role of a National Integrity System in Fighting

Corruption’ (1997) 23 Commonwealth Law Bulletin 3.

32 See Rose-Ackerman (n 30); Robert Klitgaard, Controlling Corruption (University of California Press 1988). 33 See, for example, Heather Marquette, Vinod Pavarala and Kanchan K Malik, ‘Religion and Attitudes Towards

17

by time or expertise may co-opt an agent to interact with the client on his behalf. This

constitutes a restatement of the principal-agent problem. The tax system, for instance, has been

described as a hierarchy of contracts between the principal, the agent and a supervisor. Under

this model, the principal is often the elected representative of the people, the agent is the

taxpayer and the supervisor is the tax official who ensures that the taxpayer complies with his

civic duty.34 The principal sets the agenda for this relationship, which the agent should comply with when dealing with the client. The principal may directly monitor the relationship between

the agent and the client or may do so indirectly with the aid of other agents. The principal may

similarly appoint other agents to provide parallel services to the client in line with his set

agenda.

The first step in applying this model to the relationship between business and the tax

system involves the identification of the principal, agent and the client. This task involves

hidden complexities which may be easily neglected. These complexities lie in the power play,

contributed to by the surrounding economic and political circumstances, which determines the

identity of the actor that sets, enforces and monitors the agenda in a given case.

Though with differing levels of probability, any actor in the two-way relationship may

hold the position of principal in accordance with whose interests and under whose direction the

agenda is set for the tax system as a whole. However, researchers commonly award this role to

either the people35 (as will be the case in a representative democracy) or to the political actors (tax policy-/law-makers) who stipulate the laws and policies by which the tax system is

administered and adjudged.36

Under this principal-agent-client model, corruption is usually perceived as a function

of the ability of the principal to monitor the actions of the agents and demand accountability,

which is affected by the extent of the agent’s discretionary powers.In line with this, Klitgaard37 argued that within the principal-agent-client model, corruption equals monopoly power plus

discretionary power minus accountability. However, despite access to an adequate mechanism

for monitoring and demanding accountability, passive or active collusion between the principal

34 See Jean Tirole, ‘Hierarchies and Bureaucracies: On the Role of Collusion in Organisations’ (1986) 2(2)

Journal of Law, Economics and Organisation 181; R Antle, ‘An Agency Model of Auditing’ (1982) 20 Journal of Accounting Research 503.

35 Nico Groenendijk, ‘A Principal-Agent Model of Corruption’ (1997) 27 Crime, Law & Social Change 207.

36 Tim Besley, Principled Agents? The Political Economy of Good Government (Oxford University Press 2006);

Susan Rose-Ackerman (n 30).

18

and the agent in flouting the agenda may be sufficient to sustain corruption. It is this foundation

that forms the basis for introducing the theory of collective actionto the concept of corruption.

Collective action theoristsacknowledge the potential unwillingness or incapacity of the

principal to defend the agenda or its inherent interests. They propose a study into the causes of

this unwillingness or incapacity. These causes may include the usurpation of the mantle of the

majority by minority interests due to the superior organisational prowess of the latter.38 It may also include the loss of faith in the essence of the agendaor the often misguided hope for present

or future profit from its violation on the part of the principal.39 This is captured by Besley’s

call for ‘principled principals’.40

Arguably, there is no substantive difference between an approach based on the

principal-agent-client model and that based on collective action. The formal difference between

both approaches resides in the identification of the principal whose interests the set agenda

seeks to protect. Where a contextual attempt to identify the true principal is conducted, rather

than adopting a pre-defined view of this actor, principal-agent-client and collective action

approaches become, by and large, similar.

For the purpose of this thesis, corruption will be addressed as a potential actor in the

network that constitutes the relationship between business and the tax system. It may serve as

an actor (or intermediary) through which other actors are enrolled or co-opted into the network

that forms the two-way relationship. For instance, compliance (or non-compliance) may be the

result of the presence or absence of corruption in the network. Compliance (or non-compliance)

may also be an actor in the network that produces corruption. Likewise, businesses may only

be able to reach out to the various terminals of the tax system and attain influence at a distance

where corruption is present (or absent) in the network.

Corruption is, in essence, a transient network composed of a potentially diverse

collection of human and non-human actors. Its strength and durability in any system depends

on the variety of actors that make up its network. A strong culture ingrained in the psyche of

persons in the tax system, for example, may be an actor in the network that produces corruption.

This, together with other actors, may account for the strength and durability of corruption

within that system.

38 For example, by applying Olson’s logic of collective action. Mancur Olson, The Logic of Collective Action

(Harvard University Press 1965).

39 See, for instance, Monika Bauhr and Marcia Grimes, ‘Indignation or Resignation: The Implications of

Transparency for Societal Accountability’ (2013) 27 Governance 291.

19

1.5.2 Impact of Corruption

A considerable amount of research has been carried out on corruption, especially as it relates

to tax administration.41 It has been held to have a negative correlation with economic growth,42 as well as an adverse effect on tax effort,43 tax morale,44 rule of law,45 human capital,46 domestic

firm growth,47 firm value48 and foreign direct investments (FDIs)49. Egger and others distinguish between ‘grabbing hand’ and ‘helping hand’ corruption and state that the former

(which suggests a negative correlation with FDI) outweighs the latter (which suggests a

positive correlation).50 They also found that corruption is an important determinant of FDI in developing countries but not in developed countries.51 Uhlenbruck and others argue that multinational companies are more likely to enter into a jurisdiction where corruption is highly

pervasive via a wholly owned subsidiary rather than through a local partner.52 Hope and others

41 Odd-Helge Fjelstad, ‘Corruption in Tax Administration: Lessons from Institutional Reforms in Uganda’ (Chr

Michelsen Institute Working Paper No 10, 2005); Odd-Helge Fjeldstad and Bertil Tungodden, ‘Fiscal Corruption: A Vice or a Virtue?’ (2003) 31 World Development 1459; Odd-Helge Fjeldstad, ‘Fighting Fiscal Corruption: Lessons from the Tanzania Revenue Authority’ (2003) 23(2) Public Admin Dev 165; Sheetal K Chand and Karl O Moene, ‘Controlling Fiscal Corruption’ (1999) 27(7) World Development 1129.

42 Andrei Shleifer and Robert Vishny, ‘Corruption’ (1993) 108 Quarterly Journal of Economics 591 (cf

Nathaniel Leff, ‘Economic Development through Bureaucratic Corruption’ (1964) 82(2) American Behavioural Scientists 337; Francis Lui, ‘An Equilibrium Queuing Model of Bribery’ (1985) 93 Journal of Political

Economy 760. See Pranab Bardhan, ‘Corruption and Development: A Review of the Issues’ (1997) 35 Journal of Economic Literature 1320 for a review of literature on corruption and development.

43 Tax effort is usually measured by the ratio of tax revenue generated from the Gross Domestic Product of a

country. See, Richard Bird, Jorge Martinez-Vazquez and Benino Torgler, ‘Tax Effort in Developing Countries and High Income Countries: The Impact of Corruption, Voice and Accountability’ (2008) 38(1) Economic Analysis and Policy 55; Dhaneshwar Ghura, ‘Tax Revenue in Sub Saharan Africa: Effects of Economic Policies and Corruption’ in George T Abed and Sanjeev Gupta (eds), Governance, Corruption and Economic

Performance (International Monetary Fund 2002).

44 Tax morale refers to the attitude of taxpayers to compliance. Fjeldstad and Tungodden (n 41).

45 Vito Tanzi, ‘Corruption around the World: Causes, Consequences, Scope and Cures’ (International Monetary

Fund, IMF WP98/63, May 1998).

46 Pak Hung Mo, ‘Corruption and Economic Growth’ (2001) 29 Journal of Comparative Economics 66.

47 Raymond Fisman and Jakob Svensson, ‘Are Corruption and Taxation Really Harmful to Growth? Firm Level

Evidence’ (World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No 2485, 2000).

48 Michael Long and Rao Spuma, ‘The Wealth Effect of Unethical Business Behaviour’ (1995) 19 Journal of

Economics and Finance 65.

49 Shang-Jin Wei, ‘Why is Corruption So Much More Taxing than Tax? Arbitrariness Kills’ (NBER Working

Papers No 6255, 1997). Corruption may also affect the choice of entry modes, Peter Rodriguez, Klaus Uhlenbruck and Lorraine Eden, ‘Government Corruption and the Entry Strategies of Multinationals’ (2005) 30(2) Academy of Management Review 383.

50 Peter Egger and Hannes Winner, ‘How Corruption Influences Foreign Direct Investment: A Panel Data

Study’ (2006) 54(2) Economic Development and Cultural Change 459; cf Peter Egger and Hannes Winner, ‘Evidence on Corruption as an Incentive for Foreign Direct Investment’ (2005) 21 European Journal of Political Economy 932.

51 ibid.

20

argue that corruption increases business costs and deters investments as a result.53 Furthermore, corruption has been held to lead to inefficient governments, faltering economic

competitiveness,54 distrust amongst citizens55 and general lowering of social capital.56 It has been argued that corruption also leads to the inefficient diversion of talent57 and government expenditure.58 Participating in corruption may be seen as an option for businesses that wish to

operate in the formal economy while avoiding an associated regulatory burden.59 It may also enable firms to continue operating in the shadow economy without detection from the

authorities.60

Though not central to this thesis, it is worthwhile to briefly discuss the nature and

possible impact of corruption on the formulation of tax policies and enactment of laws, the

administration of tax laws and policies and the resolution of tax disputes. This provides added

justification for a study into the persistence of corruption in the two-way relationship between

business and the tax system.

1.6 The Formulation of Tax Policies and Enactment of Laws

Although the actors operating at the tax policy and law terminals may be different – hence the

separation of the terminals – the issues arising from both terminals are broadly similar. This is

why they are discussed under the same heading in this section.

Corruption at these terminals may involve the grant of favourable tax policies and laws

(such as exemptions and tax holidays) in return for some form of social or economic

consideration from businesses. It may also involve the outright demand for such considerations

in order to avoid unfavourable tax policies or laws. Corruption may construct formal or

substantive barriers that restrict certain businesses from interacting with the tax system at the

53 Kempe Ronald Hope and Bornwell C Chikulo, Corruption and Development in Africa (Macmillan 1999). 54 Alberto Ades and Rafael Di Tella, ‘Rents, Competition and Corruption’ (1999) 89(4) The American

Economic Review 982.

55 Manuel Villoria, Gregg G Van Ryzin and Cecilia F Lavena, ‘Social and Political Consequences of

Administrative Corruption: A Study of Public Perceptions in Spain’ (2012) 73 Public Administration Review 85.

56 Stephen Knack and Philip Keefer, ‘Does Social Capital Have an Economic Payoff? A Cross-Country

Investigation’ (1997) 112(4) The Quarterly Journal of Economics 1251.

57 Kevin Murphy, Andrei Shleifer and Robert W Vishny, ‘Why is Rent-Seeking So Costly to Growth?’ (1993)

83 The American Economic Review 409; William J Baumol, ‘Entrepreneurship: Productive, Unproductive and Destructive’ (1990) 98 Journal of Political Economy 893; Tanzi (n 45).

58 Vito Tanzi and Hamid Davoodi, ‘Corruption, Public Investment and Growth’ (International Monetary Fund,

IMF WP97/139, October 1997).

59 Jay Pil Choi and Marcel Thum, ‘Corruption and the Shadow Economy’ (2005) 46 International Economic

Review 817.

60 Stravox Katsios, ‘The Shadow Economy and Corruption in Greece’ (2006) 1 South-Eastern European Journal

21

tax policy and tax law terminals. It may also trigger voluntary withdrawal by businesses from

interaction with the tax system at these terminals. These consequences may deprive the

terminals concerned of information about the plight of these businesses, thus reducing the level

of responsiveness between the tax system and the disaffected businesses.

Conversely, corruption may increase the level of interaction between these terminals

and businesses that benefit from the state of affairs. It may also lead to an increase in interaction

between the disaffected businesses and other terminals of the tax system. For instance, the

promulgation of ‘corrupt laws’ may lead to increased recourse by businesses to the dispute

resolution terminal to challenge these laws.

The grant of tax exemptions, holidays and other policies or laws which result in the

narrowing of the tax base as a result of corruption may lead to the increase (concentration) of

the tax burden on a limited number of businesses. This grant of specific exemptions may also

increase the complexity of the tax system, which may in turn increase uncertainty, discretionary

powers of officials and the compliance costs of businesses. Corruption may also lead to a high

perception of unfairness and inequality by businesses in relation to these terminals. It may

cause these businesses to seek both legal and illegal means of escaping the tax net such as by

tax evasion, avoidance or by leaving the jurisdiction altogether.

1.7 Administration of Tax Policies and Laws

Corruption also has a significant impact on the interaction between business and the tax system

at the tax administration terminal. At this terminal, the interaction between business and the

tax system is most direct.

By the use of corrupt methods, businesses may escape the tax net, reduce their tax

liability or reduce the burden of administrative compliance on them. Apart from giving an

unfair advantage to favoured businesses, corruption at this terminal may lead to the narrowing

of the tax base. This may in turn result in the increase of the tax burden of those remaining

within the tax net. The increased tax burden may result from the reaction of the tax system to

the need to generate the required level of revenue for the provision of infrastructure or the

maintenance of the welfare state. This reaction may, for instance, take the form of increased

tax rates or the reduction in the number of general tax exemptions. The shortfall may also be

replenished through over-enthusiastic or excessive enforcement of the tax laws on

non-participating businesses.

The increment of tax rates or intensification of tax audits targeted at generating more

22

positions. These corrupt tax officials may view this increment or intensification as an added

opportunity to negotiate or obtain higher bribes. Businesses may be pushed to hide more

revenue from the tax net. Consequently, the increment or intensification may yield less revenue

for the state.61

Where businesses obviate oppressive compliance requirements or the application of

archaic laws through corruption, this may reduce the incentive on these businesses to instigate

change through their influence on the tax system. This may in turn reduce the interaction

between business and the tax system at the tax policy and tax law terminals on this issue,

thereby depriving these terminals of information and reducing the responsiveness of the tax

system to the needs of business in this regard. Corruption in the relationship between business

and the tax system may therefore be partly responsible for the continued existence of archaic

and burdensome policies, laws and administrative requirements in certain tax systems. Corrupt

tax officials may also resist any simplification of the tax system which may endanger their

rent-seeking activities.

The increased tax burden, the general perception of unfairness or the sense of

disillusionment which may result from the prevalence of corruption may incentivise

disgruntled businesses to look for ways to avoid or limit their exposure to the tax system

through tax avoidance, evasion62 or by leaving the jurisdiction entirely.

1.8 Resolution of Tax Disputes

Consideration of the impact of corruption on the interaction that takes place between business

and the tax system at the courts, tribunals and other bodies that make up the dispute resolution

terminal is essential.This mainly falls under the umbrella of judicial corruption which has been

defined as utilising the court’s authority for the private benefit of the court officials or other

public officials.63

The dispute resolution terminal plays a crucial role in the relationship between business

and the tax system. Businesses as well as other actors rely on this terminal as the final regulator

of actions and meaning. Its impartiality is integral to the performance of its functions.

Therefore, where corruption is rife at this terminal, the entire foundation of the relationship

61 Amal Sanyal, Ira N Gang and Omkar Goswami, ‘Corruption, Tax Evasion and the Laffer Curve’ (2000) 105

Public Choice 61.

62 For instance, Smith has argued that businesses may resist tax laws and authorities as a result of corruption by

tax officials. See Kent W Smith, ‘Reciprocity and Fairness: Positive Incentives’ in Joel Slemrod (ed), Why

People Pay Taxes: Tax Compliance and Enforcement (University of Michigan Press 1992) 227.

63 See Petter Langseth, ‘Judicial Integrity and its Capacity to Enhance the Public Interest’ (UNODC, CICP8,

23

between business and the tax system may be put at risk. For example, in a valedictory speech

a former justice of the Nigerian Supreme Court described the impact of a corrupt arbiter in the

following words:

A corrupt judge is more harmful to the society than a man who runs amok with a dagger in a crowded street. The latter can be restrained physically. But a corrupt judge deliberately destroys the moral foundations of society and causes incalculable distress to individuals through abusing his office while still being referred to as honourable.64

The decisions of the arbiters in the dispute resolution terminal may be steered by their

receipt of financial or other corrupt considerations from businesses. Where corruption of this

nature is rampant, the decisions of these arbiters will not only be unfair but will also be

inconsistent. This will in turn increase the general level of uncertainty on the state of the law.

While increased uncertainty may empower the tax administration with regard to

businesses that do not socially or economically purchase decisions, it may weaken the tax

administration with regard to those that do and create an unfair advantage in favour of the latter.

However, the number of persons in the latter group may be reduced by the high cost of

purchasing decisions – which includes both the cost of instituting the action and the payment

to (or some form of relationship with) the arbiter – leaving the majority at the mercy of the tax

administration.

Uncertainty may also lead to an increased recourse to the dispute resolution terminal

by businesses wishing to challenge the application of the law by the tax administration. This

may in turn increase the transaction costs of these businesses. Conversely, where businesses

perceive that corruption is prevalent in the dispute resolution terminal, these businesses may

lose faith not just in the dispute resolution terminal but in the entire tax system. This may serve

to limit their recourse to this terminal in the face of what they believe is a contravention or

misapplication of the law by tax officials, thereby increasing the powers of the tax

administration with regard to these businesses.

Corruption in the dispute resolution terminal may heighten the sense of unfairness and

the disillusionment of non-participating businesses as well as increase their transaction costs.

This may consequently incentivise them to seek legal or illegal means to reduce or escape their

tax liability.

24

1.9 The Interaction between the Terminals

Actors within a terminal of the tax system may possess and utilise a power to alter the impact

of corruption at a different terminal of the tax system. However, this ability depends on the

structural relationship between the terminals. It may also depend on the presence of different

levels of corruption in these terminals.

It is important not only to consider whether an actor possesses the power to alter the

impact of corruption but also the practicalities of the exercise of such power. This alteration

can be achieved either by changing the constitution of the other terminal or by changing the

nature of its output.

In terms of altering the constitution, actors within the tax policy terminal may have the

power to determine the amount of corruption in the tax law terminal and vice versa. These

actors may do this by investigating the activities of the members of the other terminal and

facilitating the removal and prosecution of erring members. However, the relationship between

these terminals may make the exercise of this power impractical or may lead to the infection

of one with the ‘disease’ of the other. This is more likely to be the case in a system of

government which lacks clear separation of powers and independent arms of government or a

one party state as opposed to a system of government with clear separation of powers and

independent arms of government or a multi-party state.

Actors within the tax policy and tax law terminals may also affect the amount of

corruption in the tax administration and dispute resolution terminals through the exercise of

their powers to appoint, promote and discipline staff of those terminals.For instance, they may

increase the level of corruption and ethnic bias by appointing officers that are corrupt or share

their ethnic bias.

Furthermore, actors within the tax policy and tax law terminals may enact (and enforce)

policies and laws that regulate the procedures in other terminals in a manner that curtails or

increases corruption. By a similar token, actors within the dispute resolution terminal may

entertain (or refuse to entertain) challenges to policies and laws specifying procedures which

may give rise to corruption.Businesses may be indicted for corruption by the tax policy, tax

law and dispute resolution terminals, thereby curtailing their use of this societal factor to

achieve their private goals. The aforementioned actions have the effect of changing the

constitution of the receiving terminals, and thus regulating the impact of corruption on their

activities.

As for altering the output of the terminal, in the process of enacting laws, actors within

25

terminal. For instance, these actors may reject corrupt bills or tone down the effect of unduly

discriminatory bills after taking into account the interests of businesses that were hitherto

excluded. Conversely, they may intensify the impact of corruption on these outputs by their

amendments to it.

Actors within the tax administration may reduce the effect of discriminatory laws by

granting extra-statutory concessions targeted at extending favourable policies to excluded

businesses. These actors may also decide not to enforce laws that discriminate against a

particular kind of business. Conversely, they may strengthen the discriminatory effect of laws

or policies in the manner in which they implement them.

Actors within the dispute resolution terminals in most jurisdictions are authorised to

modify the output of the tax policy and the tax administration terminals where this is tainted

by corruption. These actors may also alter the output of the tax law terminal for a similar reason.

However, this is usually only legally (as opposed to factually) justified in common law

jurisdictions where there is a superior law which the said output contravenes. They may,

however, intensify the effect of corruption through their exercise of (or failure to exercise)

these powers.

Nevertheless, the power of the actors within the dispute resolution terminal to modify

the effect of the societal factors in other terminals is limited by the fact that the said actors can

only act when a dispute is brought before them for adjudication. Where the outputs of the other

terminals are not challenged by businesses, these actors usually have no power to modify them.

This has the effect of safeguarding outputs which are unduly favourable to certain businesses

as a result of corruption from the scrutiny of the actors within the dispute resolution terminal.

This is because a business that has avoided or mitigated its tax obligations with the aid of

corruption would not challenge this state of affairs. Furthermore, other businesses that may

wish to challenge this state of affairs through the dispute resolution terminal may be hindered

from doing so by either a lack of information or procedural rules such as the requirement of

locus standi.

Finally, actors within the tax policy and tax law terminals can alter the outputs of the

tax administration and dispute resolution terminals by creating a new policy or law to

counteract them.

This summary depicts the considerable role that corruption may potentially play in the

two-way relationship between business and the tax system. It also provides sufficient basis for

a study into the means by which corruption persists in the said relationship. This study will be

26

1.10 Methodology

This research is socio-legal in nature. It seeks to determine the means by which corruption is

sustained in the two-way relationship between business and the tax system. Using ANT, the

researcher isolated and examined corruption as a possible actor-network in the two-way

relationship between business and the tax system. The researcher gathered information needed

to answer the core question of this research through an empirical study. Conducting an

empirical study follows from the use of ANT as the theoretical approach in this research.As

Law states, ‘Actor-Network Theory almost always approaches its task empirically’.65

The empirical research used a mixed methods approach, comprising both qualitative

and quantitative methods. Using qualitative methodology is appropriate for this research due

to the delicate nature of its subject matter and the information it seeks to derive. This

information includes the beliefs, fears, attitudes and perceptions of individuals on sensitive

issues such as corruption, which may be too diverse to be captured by a rigid quantitative study.

However, while a qualitative methodology may be used to obtain information on the potentially

broad experiences of actors in the field, a quantitative methodology may be used to provide

statistical data to back up certain conclusions reached, as was done in this research. This serves

to mitigate concerns about anecdotism often associated with the usage of qualitative data.

Hence, the research was divided into two phases: qualitative methodology was used in phase

one, and quantitative methodology in phase two.

In phase one of the empirical research, semi-structured interviews were used as the

primary tool for gathering data. Fifty participants were interviewed comprising business

representatives (including tax practitioners) and tax officials. Interviews were conducted either

face to face or by telephone depending on what was practicable in the circumstances. There is

a concern that telephone interviews produce data of poorer quality than face-to-face interviews

due to the potential for reduced rapport between the interviewer and interviewee.66 Also, certain

data such as body language may not be captured by telephone interview.67 Nevertheless, telephone interviews remain a valid way of obtaining data, especially on sensitive and

65 Law (n 4) 385.

66 Roger W Shuy, ‘In-person versus Telephone Interviewing’ in James Holstein and Jaber Gubrium (eds), Inside

Interviewing: New Lenses, New Concerns (Sage Publications 2003).

67 Gina Novick, ‘Is There a Bias against Telephone Interviews in Qualitative Research?’ (2008) 31 Research in

27

potentially embarrassing issues such as corruption and taxation.68 In the view of the researcher after conducting the research, there was no noticeable difference in the quality of data derived

from both interview methods.69

The face-to-face interviews took place at various locations including the offices or

homes of the participants, and in restaurants and malls. With the permission of the participants,

every interview was audio tape-recorded by the researcher and a transcript produced as soon

as possible after the interview.

The researcher made direct approaches to various potential participants via LinkedIn or

by visiting their offices. After concluding an interview, participants were asked to refer the

researcher to fellow tax practitioners who may be willing to participate in the research. Owners

of small businesses, who participated directly in the research, were randomly approached by

the researcher at their offices or other place of business for the research.

The researcher sought information about the experiences of these participants at or with

the terminals of the tax system, in relation to their business activities. The interview was

conducted based on a topic guide which covered the following issues: the existence of

interaction; the means of interaction; the frequency of interaction; issues affecting interaction;

the expectations of businesses; the responses of businesses to unexpected actions, and the

reasons for these responses.

On completion of phase one of the empirical research, the data collated was subjected

to qualitative content analysis. The themes or codes used were partly derived from an analysis

of the raw data and partly based on the research undertaken on the theoretical aspects of the

thesis.

Based on the results of the qualitative content analysis, certain issues were identified

which formed the subjects of the quantitative study (phase two). These issues included:

business attitudes to compliance; the likelihood and means of protest against wrongdoing; the

perception of the level of discretionary powers of tax officials and vagueness of the law; the

levels of corruption engaged in by the different actors in the two-way relationship; the levels

of access which businesses have to the various terminals of the tax system; and the levels of

awareness of the main actors in the two-way relationship.

The researcher developed a questionnaire to elicit information that addressed these

issues and tested the same in a pilot with three tax practitioners. The researcher also made

68 Judith E Sturges and Kathleen J Hanrahan, ‘Comparing Telephone and Face-To-Face Qualitative

Interviewing: A Research Note’ (2004) 4 Qualitative Research 107.

28

amendments to the questionnaire based on the results of the pilot before it was administered on

the participants directly or online. About 90% of respondents in phase two of the research

project completed the questionnaire on paper. The researcher met these respondents either in

tax conferences in Nigeria or at their offices. Before handing the questionnaire over to them,

the researcher introduced himself as a research student at the London School of Economics and

gave a brief introduction to the topic of his research. The researcher also assured respondents

that they would be accorded complete anonymity and that their responses would be used solely

for his PhD research. The other 10% of participants completed the survey online through a link

provided to them by email. The email also introduced the researcher and his research topic and

promised anonymity to the online participants.

The results of the survey were analysed using the Qualtrics software. The hard copy

responses were inputted manually into the software by the researcher, while the online

responses were automatically recorded upon completion of the survey by the respondents. The

results are mainly represented in tables and percentages. While the results of the qualitative

phase form the primary basis for empirical findings in this research, the results of the

quantitative phase provide valuable measures for various assertions and conclusions reached

from the data obtained through the qualitative study.

1.11 Nigeria as the Case Study

Nigeria, a middle income country, is not only the most populous country in Africa but also has

the highest GDP on the continent, following the rebasing of its GDP in 2014.70 It is a rentier state as about 80% of government revenue is derived from the exploitation of oil and gas. The

recent drop in the price of oil has severely affected the ability of the governments of Nigeria,

at the state and federal levels, to meet their basic obligations such as the payment of government

staff salaries.71 This has also brought to the fore the urgent need for a vibrant tax system capable

of generating sufficient revenue to fund the cost of government, amongst other things.

70 See Morten Jerven and others, ‘GDP Revisions and Updating Statistical Systems in Sub-Saharan Africa:

Reports from the Statistical Offices in Nigeria, Liberia and Zimbabwe’ (2015) 51(2) The Journal of

Development Studies 194; Olumuyiwa Olamade, ‘Nigeria in Global Competitiveness Comparison’ (2015) 3(2) Journal of Economics 146, 147.

71 See Editorial Board, ‘Public Workers and Unpaid Salaries’ (The Guardian, 9 June 2015)

29

By current estimates, the GDP to tax ratio in Nigeria is at an abysmal level, ranging

between 4% and 12%.72 This reveals huge potential for the ongoing reforms of the Nigerian tax system targeted at establishing a viable revenue generating alternative to the unreliability

of oil and gas exploitation. To the extent that these reforms relate to business, the Nigerian

government, in its drive to secure more revenue, must carefully consider the impact of whatever

policy it introduces on the movement of capital. This is especially the case as capital becomes

increasingly mobile against the backdrop of globalisation and advancements in technology.

Prior to Nigeria’s independence in 1960, corruption was already conspicuous and

featured prominently in the country’s discourse.73 The perpetration of corrupt acts, however, predates the country’s creation in 1914 or its subjugation to British colonial rule in the late 19th century.74 Powerful actors in pre-colonial times engaged in acti