1

The politics of health care: examining the role of

partisanship in health care

Leiden University

Public administration: Economics and Governance Track Master’s

thesis

Name:

Samir Mustafa Negash

Student id: s1280309

Date:

06/11/2018

2

Table of contents

1. Introduction ... 3

2. Theoretical framework ... 7

2.1 Partisan politics and the power resource theory ... 7

2.2 The new politics of the welfare state ... 9

2.3 Health care retrenchment in a social rights perspective ... 12

2.4 Hypotheses ... 18

3. Methodology ... 21

3.1 Case selection and operationalization ... 23

3.2 Dependent variable ... 23

3.3 Independent variable ... 24

3.4 Data ... 29

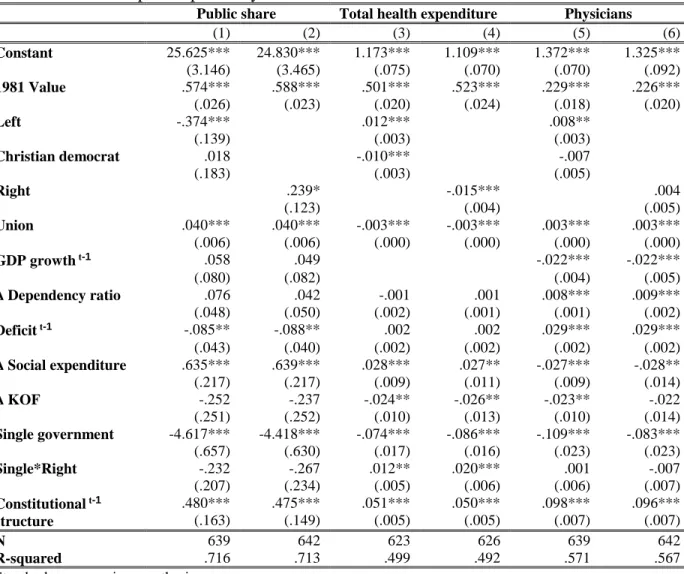

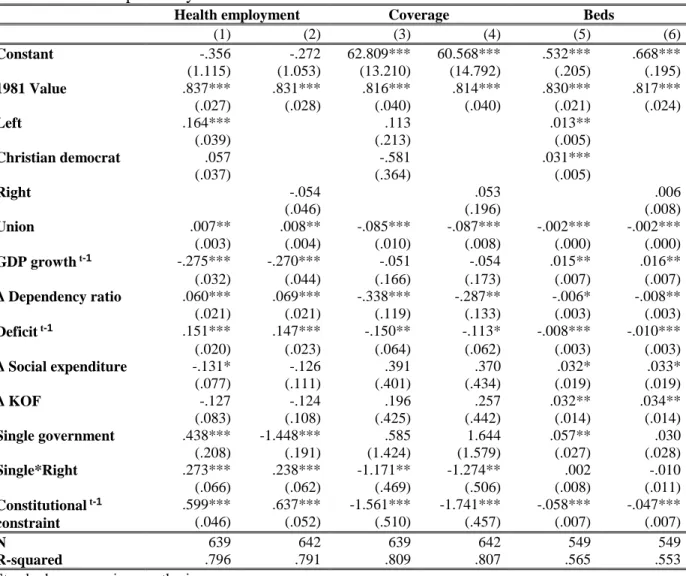

4. Results ... 30

4.1 Descriptive statistics ... 30

4.2 Inferential statistics ... 32

4.3 New politics models ... 42

4.4 Analysis and discussions ... 51

5. Conclusion ... 53

Literature ... 56

3

1. Introduction

Following the golden-age of the welfare state (1960-1980), welfare scholarship has described the

welfare state as being in a perpetual state of austerity. According to Paul Pierson (1994), the period

after 1980 constitutes a period of permanent austerity and is characterized by welfare retrenchment

and restructuring. The period of welfare expansion ended in most mature western democracies as

countries were confronted with stagflation, i.e., high unemployment and persistent inflation.

Structural changes in the economy exert downward pressures on welfare states to reduce their

social wage, e.g., by reducing social spending and cutting taxes and social contributions in order

to maintain attractive investment climates. As governments are dependent on business and capital

to create jobs and generate revenues for taxes, they are receptive to the demands made by capital,

albeit their receptivity to these claims comes in varying degrees. The implications for the welfare

state are a potential regulatory and welfare ‘race to the bottom’ (Myles & Quadagno, 2002: p. 43).

A range of domestic and international developments have made the financing and delivery

of welfare programs more difficult. On the international front, these changes have been a function

of changes associated with globalisation. Internationalisation of the economy has pushed states

toward fiscal and monetary discipline. This has been the result of increased trade with low wage

countries in the global south, which generates inter-industry competition between developed and

developing countries and has led to offshoring and deindustrialisation. Increased capital mobility – enabled by the removal and reductions in restrictions of capital flows – has also incentivised

states to be more receptive to market forces (Raess & Pontusson, 2015: p. 3; Burgoon, 2001; Autor,

Dorn & Hansen, 2015). Additionally, for European welfare states, membership to the European

Union (EU) and European Monetary Union (EMU) has functioned as another means of fiscal and

monetary constraint on the welfare state. Membership to these institutions has resulted in reduced

autonomy of states to conduct social policy by privileging low deficits and low inflation rates over

full employment or risk-sharing (Brady and Lee, 2014; Korpi, 2003: p. 604).

Domestically, the shift from industrial to post-industrial economies with high employment

rates in the services industry has resulted in lower economic growth rates (Iversen & Cusack,

2000). This shift toward post-industrial economies has also shifted risks across actors in the

economy. This shift has complicated welfare provision by creating additional budgetary pressures

on the welfare state (Korpi, 2003: p. 590). Demographic changes such as population aging, a

4 constellation of the labour market due to the increased participation of women, has increased

pressure on welfare states to adapt. This has resulted in an emphasis on social investment, active

labour market policies and a focus on capacity enhancing services such as child care and education,

rather than providing passive wage replacement. (Busemeyer et al, 2018: p. 802; Esping-Andersen,

1999: p. 182). Long term unemployment or structural unemployment has also become more

prevalent due to technological advances. This has also made funding the welfare state more

difficult and poses another major challenge for contemporary welfare states (Pierson, 2001b;

Schwartz, 2001: p. 19; Korpi, 2003: p. 603).

These developments have constituted pressures on the welfare state as a whole. Their impact

has varied across different policy areas. Health care systems, for example, have experienced cost

pressures uniquely related to developments in the policy area of health care. As with other

components of the welfare state, health care seems to have been subject to the same general pattern:

a golden age of expansion (1960-1980) and a subsequent period of stagnation and restructuring

after 1980s (Freeman & Moran, 2000: p. 37). Health care cost have been rising in all OECD

members, more than doubling in total expenditures since 1970. It is no wonder then that from the

1980s onward, governments in OECD countries began to raise questions regarding the efficiency

of their health care systems. Consequently, mature welfare states started examining the

expenditures on health care and re-evaluated their health care systems in an effort to enhance

efficiency and restrain costs (Mackenbach et al, 2012: pp. 341-342).

This study aims to contribute to the welfare state scholarship by zooming in on developments

in on the field of health care. It seeks to gauge how health care systems of 22 industrialised

democracies have adapted to these pressures. Using a Large-N design and studying the period

1981-2014, this project studies whether there is a relationship between partisanship and various

measures of health care policy output over time. Previous studies on the importance of partisan

makeup of governments for the organizing health care systems have produced mixed results (see

references). It builds on these previous works by expanding the scope of research from the

financing of health care (e.g. Jordan, 2011; Potrafke, 2010) to service provision capacity and

regulation. The research question guiding this study is thus as follows: What effects have different

partisan makeups of governments had on degree of retrenchment in the field of health care?

To answer this question, the explanatory power of the power resource theory (Korpi, 2006;

5 1996; 1994) will be tested. These two theories make competing claims about the role and

importance of partisanship, as well as the likelihood of large scale retrenchment. The power

resource theory holds that the distribution of power resources matters for welfare expansion. It

posits that organizations that help wage earners engage in collective action, e.g. through

unionization or translating their demands into policy via voting for left wing parties, are critical in

understanding outcomes of distributive conflicts. Left and right wing parties have different

preferences and pursue different policies according to the power resource theory. Left parties

favour expansion of the welfare state and pursue higher degrees of redistributions. Right wing

parties pursue retrenchment and restructuring of the welfare state.

The new politics approach’s claims differ from this, as the role of partisanship is more

circumspect according to this theory. Due to differences in the goals and consequences of welfare

expansion and retrenchment, the political logic of retrenchment varies substantially from

expansion. The behaviour of left and right parties becomes more similar according to the new

politics thesis. That is, left wing parties do not or cannot pursue large expansion, right parties by

contrast cannot pursue expansion. The new politics school also holds that large scale retrenchment is unlikely due to the welfare state’s staying power. The existence of the welfare state alters the

political landscape and creates powerful constituencies that will come to the aid of social programs.

Governments can choose from a range of options in response to cost pressures in health

care. The specific responses to these challenges are the often subject of political and distributive

conflicts. Health care can be profoundly political as it concerns an object of collective consumption

with a large role for the state in all mature welfare state (Moran, 2000: pp. 141-142). The chosen

methods may reflect partisan preferences as some previous studies have indicated (Montanari &

Nelson, 2013a; 2013b). Overall, governments have to contend with balancing multiple goals in

organizing health care and making decisions about cost containment. These goals include ensuring

equity and access; having health systems that are efficient and delivering high quality health care

services. (Blank et al, 2007: p. 93). These goals are inherently in conflict as it is impossible to

deliver on all fronts. The choices made could then, to a certain degree, reflect the values and

priorities of the actors involved. This makes them a relevant area of research for politics

researchers.

What is unclear from the existing literature on welfare retrenchment and partisanship is

6 systems systematically vary according to partisan makeup of governments and distribution of other

power resources. The types of administrative changes pursued affect the degree to which health

care services can readily be accessed and the degree to which health care is provided as a social

right. Health care constitutes a crucial element of the social right to citizenship in most mature

welfare states. This study expands the scope of analysis to include these dimensions, in line with

previous research (Montanari & Nelson, 2013a; 2013b; Bambra, 2005). The analysis will examine

how partisan makeup of government affects the range of health care resources available in a

western democracy. Since the 1980s, the private share of health care financing has increased in all

members of the Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). This suggests

some degree of retrenchment in health care. The following sections will argue that financing is not

the only relevant dimension of health care retrenchment. Instead, financing is but one dimension

of health care in which retrenchment can take place. This study hopes to contribute to the welfare

scholarship by examining how partisanship affects health care service provision. It does this by

applying two theories often used to explain developments in cash benefits schemes to services

such as health care which have different underlying logic. In so doing it tries to expand current

scholarship on the determinants of public services as well as the politics underlying services such

as health care.

This thesis is structured as follows: in the next section the power resource theory is

presented and elaborated on. This is followed by a discussion of the new politics thesis. After a

discussion of the power resource theory and the new politics thesis, the politics of health care

retrenchment are discussed. Special attention is paid to the differences between services and

in-kind benefits versus cash benefits. Following this theoretical discussion, the research design is

presented. This study uses time-series data on 21 members of the OECD and performs statistical

analysis using linear regression with panel-corrected standard errors to answer the research

question. After the research design, the results are presented and analysed. The final chapter

7

2. Theoretical framework

2.1 Partisan politics and the power resource theory

One of the main approaches used to study the development of the welfare state is the power

resource theory (Bradley et al, 2003: p. 193). According to scholars in the power resource school

of thought, contemporary welfare states are the product of class-based distributional conflicts.

Socioeconomic class is related to the types of life course risks individuals are exposed to. As such,

the fault lines of distributive conflicts are likely to reflect these class-based differences in risk

exposure. Moreover, socioeconomic class shapes the range of power resources individuals have at

their disposal. Consequently, researchers in the power resource school have argued that welfare

state development mirrors the class-based distributive conflicts and partisan political distribution

of power in different countries (Korpi, 2006: p. 168). Therefore, differences in the distribution of

power resources as well as the types of cross-class coalitions present in individual countries

accounts for the variation in welfare states (Esping-Andersen, 1990, chapter 1).

Power resources reflect the ability of individuals or groups to sanction or reward other

actors (Korpi, 1985: p. 33; Korpi, 2006: p. 172). Their relevance to welfare state development

stems from the fact that they enable wage earners to equalize or erase their inherently

disadvantaged position vis-à-vis employers and business interests e.g. through unionization or

organizing politically in class-based political parties (Korpi, 1985: p. 41; Korpi, 2006: p. 171). The difference between wage earners and capital owners’ position stems from the differences between

physical capital and human capital, i.e., the specific means of production owned by different

groups in society. Employers’ power flows from their ownership of physical capital. Physical

capital lends itself to concentration, is scarcer and is easier to divest or apply as it requires low

mobilization cost. Wage earners on the other hand tend to rely on human capital rather than

physical capital. Labour power is the primary basis of human capital, this is derived from education

and occupational skills for example. This power resource is more difficult to mobilise, is less

scarce and, importantly, harder to concentrate and difficult to divest from its owner. It is their

advantage in numbers that gives their form of power resource its potency. If wage earners do not pool their resources, then employers’ capital derived power resources can be leveraged to bend

distributive conflicts to their will (Bradley et al, 2003: p. 197). For these reasons wage earners

8 favour (Korpi, 1985: p. 34).

The power resources theory is distinctly different from other partisan accounts of welfare

state development. What the power resource account has in common with other non-power

resource-based partisan approaches to studying welfare development is the emphasis they put on

distribution of partisan political power. As such, both the power resource theory and partisan

approaches of welfare state development essentially hold that parties represent different social

constituencies with different needs and interests, that parties’ social profiles mirror the social

preferences of their constituencies and that they are policy-seeking as well office-seeking

(Schmidt, 2010: p. 213). Where they differ though, is that power resource accounts of welfare

development also emphasises other means wage earners have at their disposal to organise

collective action, e.g. unionization, electoral turnout. Moreover, regarding the partisan effects,

power resource scholars have correctly identified Christian democratic parties as playing a large

role in developing welfare states as well. In many western European countries Christian democrats

have been successful in mobilising parts of the working and middle classes by catering to them

with their distinct type of social policy (Van Kersbergen, 1995). Therefore, researchers in the

power resource school not only take into account strength of left parties, but they also take into

consideration the strength of Christian democratic parties (Korpi, 2006: p. 196; Huber & Stephens,

1993; Korpi & Palme, 2003; Esping-Andersen, 1990:).

There is, generally speaking, a substantial amount of support for the power resource

account in the comparative welfare states literature. Especially in the old politics era (i.e. from

the1960s until roughly 1980), a lot of studies confirm that incumbency of left parties is associated

with various indicators of welfare expansion (Korpi and Palme, 2003; Allan & Scruggs, 2004;

reference) For example, Huber and Stephens: (2001: p. 41; 78) find that incumbency of left wing parties and Christian democratic parties lead to distinctly different outcomes with regards to

redistribution, development of social expenditures and transfer payments. They argue that

incumbency of left parties that facilitate the translation of preferences, mobilization and

organization of the working and lower-middle classes generates generous and redistributive

welfare states. This account finds support in other studies as well (Bradley et al, 2003). Social

democracy with strong unions has been linked to expansions of the public economy by expanding

the public sector, greater degrees of decommodification, redistribution and the provision of goods

9 Christian democratic parties tends to result in overall higher expenditures, primarily through higher

transfer payments, Christian democratic governments are less likely to lead spend more on social

expenditures. Christian democracy is also associated with lower degrees of decommodification, as

Christian democrats pursue social policy that reproduces inequality instead of ameliorating or

exterminating it, and Christian democrats are also not associated with expansions of public

economy (Huber et al, 1993: pp. 717-718). In the same vein, Brady and Lee (2014) trace the causes

of cuts or changes in government spending. They find support for the power resources account as

the presence of strong trade unions is associated with lower cuts to government spending.

The main takeaway of these studies seem to be that the different social bases parties

represent affects the social policy they pursue in government. These parties’ ability to achieve their

policy goals is not only determined by their representation in parliament or government, but is also

contingent on workers mobilising outside of parliamentary politics. Moreover, changes or shifts

in the distribution of power resources can thus be expected to affect distributive conflicts (Korpi,

1985: p. 39).

2.2 The new politics of the welfare state

The claims advanced by the new politics of the welfare state perspective contradict those of the

power resource and partisan theories of welfare development. The new politics approach describes

the political logic of welfare development in an age of permanent austerity. According to Pierson

(1994; 1996; 2001), the politics of welfare retrenchment differ markedly from the politics of

welfare expansion. Welfare retrenchment is not simply the mirror image of expansion and the

politics of welfare retrenchment has its own distinctive logic. The differences in goals and political

context make the new politics fundamentally different from the “old politics” of the expansion

period (Pierson, 1996: p. 144). In contrast to could be expected based on the power resource

account, increasing power of the right and declining power of the left and unions does not appear

to have enabled large scale retrenchment of social programs (Pierson, 1996: p. 150).

Welfare state expansion often entailed the enactment of popular policies, conversely,

retrenchment is an exercise in taking away or reducing the generosity of benefits people receive.

As such, politicians enacting new social programs can engage in credit claiming, whereas

politicians advocating for and implementing restructuring or retrenching the welfare state will

10 seek to cut back on programs, they will shy away from visible cuts and retrenchment is only

possible limitedly and they will only enact them in broad based coalitions (Starke, 2006: p. 106).

Enacting cutbacks to social programs is difficult for a variety of reasons: Enacting

retrenchment can be challenging because of social psychological reasons, i.e. taking away is more

difficult than granting benefits and engenders weaker responses. Consequently, recipients and

citizens in general experience cuts more negatively, regardless of how government intends to

compensate citizens. Moreover, another factor that further compounds the challenges inherent to

welfare retrenchment is the logic of collective action: retrenchment typically imposes high and

concentrated cost on a (comparatively) small group of recipients, while promising diffuse and

often uncertain benefits on a larger group of people. Lastly, policy feedback and policy legacies

are additional factors that complicate the process of retrenchment. These factors are more

institutional in nature. They have bearing on the ways in which the welfare state has become part

of the political landscape and how this has altered the basic political calculus of actors in the welfare state. The welfare state’s existence led to the formation of new interest groups and

entrenched constituencies who rely on the welfare state, e.g. pensioner’s rights groups and patients’ rights groups. These groups have become the greatest proponents and protectors of

welfare programs. In so doing they have replaced trade unions as the interest group of greatest

significance, as was the case in the power resource account. Moreover, welfare retrenchment is

also likely to engender opposition from existing clientele due to the double payment problem and constrain government’s capacity to change policy due to lock-in effects and pre-commitments and

associated problems such as double payment. Moreover, formal institutions such as veto players

in the system also make enacting retrenchment more difficult (Pierson, 2001: p. 411-414; Levy,

2010: pp. 554-555).

The implications of the new politics for the relationship between partisanship and welfare

state development are clear: in the new politics era, partisanship is likely to matter less as the

welfare state has changed actors’ political calculus. For left parties it means they cannot, or are

restricted, in their pursuit of their preferred options of expanding existing programs or enacting

new programs. This is largely a consequence of the structural changes to the economy that have

created budgetary pressures on welfare states. For right parties this means that they are restricted

in advancing their preferred policy agenda of welfare retrenchment. As radical retrenchment is not

11 forced to obfuscate their goals or trim social programs around the edges. Therefore, the new

politics thesis would lead to the expectation that left and right parties behave more similarly with

regards to welfare development. It should be noted here that the new politics account provides

explanations for the behaviour of left and right parties. It is worth noting here that this approach

does not provide an account of Christian democrats’ preferences. It unclear whether Christian

democrats would pursue retrenchment and how they would rearrange risks.

Scholars have sought to corroborate the claims made by the new politics theory of welfare

development with overall mixed results. By and large Kittel and Obinger (2003: pp. 33-34) find

support for a declining importance of party politics on welfare state development in the new

politics era. They conclude that partisan effect decreased overt time, and stress that the importance

of partisanship for welfare development declined after 1980s. They claim that a particular type of

catch-up dynamic is unfolding. Generous states are in the process of retrenching or scaling down

their welfare state, while less generous welfare states on the other hand have expanded. As a results

welfare states are converging. Furthermore, they attribute much of the changes in welfare

development to the increasing dependency ratio due to aging and rising unemployment. Kwon and

Pontusson (2010) also argue that partisan differences seem to have disappeared in how

governments compensate domestic workers with welfare in response to globalisation. They argue

however that the rate of decline seems to be mediated by the presence of strong labour unions.

Brooks and Manza (2006: p. 822) provide additional support for the new politics approach. They

argue that welfare state resilience is explained by popular support for the welfare state. This seems

to be unrelated to distribution of power resources. They also find no significant association

between left power or the continued cabinet participation of left parties and welfare state

development in new politics era.

There are studies that find continued support for the power resource account, even in the

new politics age. For example, Allan and Scruggs (2004) test the implications of both the power

resource theory and new politics thesis and find that in the new politics age, right-wing parties

continue to be associated with retrenchment. This seems to disprove the new politics’ account,

according to which right wing parties are constrained in pursuing their preferred goal of

retrenchment. Korpi and Palme (2003: p. 41) also find that compared to secular and conservative

right parties, left-wing parties are more likely to increase, or at least, less likely to reduce the

12 finds that left parties are significantly and positively related to expansions of unemployment

insurance, pension and sick pay replacement rates. Her analysis includes data between 1980 and

2010, and the focus of the analysis is thus new politics period.

2.3 Health care retrenchment in a social rights perspective

Thus far the discussion has centred on the potential effects of partisanship on the development of

the overall welfare state. Authors across multiple disciplines, e.g. economics, sociology and

political science, have honed in on and examined the relationship between partisanship and

retrenchment in the domain of health care (see for example Jordan, 2011; Montanari & Nelson,

2013a; Potrafke, 2010; Herwartz & Theilen, 2010; Herwartz, & Theilen, 2014; Béland, 2010;

Freeman & Moran, 2000; Fervers, Oster & Picot, 2016; Pavolini & Österle, 2013; Companje,

Veraghtert & Widdershoven, 2009). What stands out is the diversity in theoretical perspectives

employed, the methods used and the variables of interest in these studies.

The causes attributed to the rising cost of health care are varied and are the result of

multiple mechanisms. The primary factors commonly cited as explaining increased health

spending are: First of all, increases in per capita gross domestic product (GDP) arguably lead to

increases in health care expenses. GDP per capita has long been a powerful explanatory variable

in explaining rises in aggregate health care expenditures, as health care appears to be a (somewhat)

elastic good (Aron-Dine et al, 2013). This means that consumption of health care increases as

national income increases. This increased consumption will then naturally be reflected in increases

in aggregate spending levels in health care (Hacker, 2004a: p. 699). Secondly, another commonly

cited factor explaining the continued increases in healthcare expenses is Baumol’s disease. Baumol’s disease refers to the limited room for productivity growth in the public sector. The

incomes of employees in the services sector have to keep pace with the incomes of employees in

the non-service sector. Over time, this combination of stagnant productivity and rising wages leads

to higher overall costs in the services sector. Given that health care is a policy field where services

make up a large part of the output, stagnant productivity will thus likely be reflected in higher

expenditures in health care (Baumol, 1967: p. 417). Thirdly, advancements in medical technology

and medicine are another commonly cited factor that could account for rises in health care

spending. These new technologies can improve health, but often come at high financial cost. Once

13 access to these technologies (Barr, 2010: p. 252; Giaimo, 2001: p. 336). Lastly, increased volume

in health care e.g. due to aging population and new treatments being available are other factors

that contribute to the increases in overall healthcare expenditures (Mackenbach, Stronks & Anema,

2012: pp. 343-344). Increases in overall healthcare expenditures are not necessarily problematic.

The increases in healthcare expenditures could simply reflect overall taste for healthcare and could

therefore constitute an entirely legitimate endeavour for governments to spend their money.

Increased healthcare expenditures could also reflect increased need for and use of healthcare

services due to demographic changes. Increased use of health services shows need for these

services and also shows why cutting back on them or otherwise shifting costs could be unpopular

(Freeman & Moran, 2000: p. 39).

Increasing expenditures on health care could nevertheless still be problematic in so far as

increased health care expenditures also constitute an opportunity cost; governments can invest a

euro only once. Spending more on health care essentially walls off, that is, forecloses expenditures

on other facets of the economy or the welfare state. Moreover, the ever-increasing expenses on

health care could have an impact on the overall economy as well. The effect of increases in health

care cost – in instances where employers cover the costs – are potential lower rates of investments.

The effects of rising health expenses in systems where employees bear the burden are potentially

higher marginal tax rates which act as disincentives for labour (Mackenbach et al, 2012: p. p. 343).

This argument finds at least some empirical support, for example by Fervers, Oser and Picot (2016) who extend Burgoon’s (2001) argument that various kinds of trade openness have dissimilar

effects in different policy areas. They examine a range of indicators for globalisation and public

share of health spending and conclude that increased openness does seem to lead to lower growth

in public health care expenses. This indicates that governments are under pressure to reduce public

health care spending to remain competitive in the face of increased international completion.

There are good reasons to assume that efforts at retrenchment in health care will differ from

efforts in other domains of social policy. Government’s health care cost containment strategies can

target the supply side or the demand side. Supply side cost containment strategies could be

agreements with preferred providers, restricting the number of doctors by putting restricting access

to the medical profession. There are also a number of demand side cost containment strategies.

These measures are aimed at making users of health care more conscious of the cost of health care

14 costs. Demand side cost containment can also be achieved through achieving slower rates of rises,

stopping cost rises in real terms or in rare instances reducing real costs (Blank, Burau and

Kuhlmann, 2007: p. 97). Governments will thus tend to shy away from achieving cost-cutting via

imposing costs on health care users. This is also apparent as in practice governments try to pursue

cost containment through stimulating competition, putting restrictions on providers and other

administrative changes. (Freeman & Moran, 2010: pp. 40-42).

Multiple authors have conducted Small-N comparative studies to research various episodes

of health care reform pursued by governments, and explore the politics underlying these reforms

(e.g. Hann, 2007; Gingrich, 2011; Giaimo, 2001). Hacker (2004a) for example examines recent

health care reforms in a couple of wealthy democracies (US, UK, Netherlands, Canada and

Germany). He argues that reform processes have been marked by change without reform and

reform without change. Toth (2010) looked at different waves of reform in health care in multiple

countries. He finds that each wave of reform is followed by a wave of counter reforms where the

effects of the previous reform are (partially) reversed. Interestingly, he notes that ideology seems

to matter in dynamic of reform and counter reform. The starting point of these studies is often the

cost pressures countries face to contain the growing costs of health care. They, however, rarely

examine explicitly the role of partisanship on attempts at implementing cost containment policies,

or the degree to which choice of cost containment strategy is tied to partisan and ideological

differences. So, while they contribute valuable information on the intentions and preferences of

actors in reform episodes, these studies do not allow for systematically quantifying the effects of

left, right or Christian democratic parties on health care.

In addition to the case study approach, numerous studies have attempted to map the long

term patterns in the development of health care expenses and the extent of retrenchment in health

care. These studies have also researched the relationship between partisan distribution of power

and changes in health care. Studies of retrenchment politics and welfare retrenchment have often

looked at cash benefits programs such as pensions or unemployment insurance (e.g.

Esping-Andersen, 1990; Korpi & Palme, 2003; or Allan & Scruggs, 2004). Studies of health care politics

have often emphasized the financing aspect by using the public share of health care expenditures

as the dependent variable. For example, in mapping health care retrenchment, Jordan (2011) tries

to gauge the effects of partisanship on health care retrenchment. His findings suggest that after

15 on the development of the public share of health spending.

In a similar vein, other authors have examined the relationship between partisan makeup

of governments and overall developments of the public share of health spending. These studies

have tended to produce mixed results as well with regards to the relationship between partisanship

and the public share of healthcare. Some find that while the private share of health spending seems

to be increasing in OECD countries (and therefore the public share has to be decreasing), there

does not seem to be an ideological basis for this, i.e. left and right parties seem to behave broadly

similarly, which would seem to disconfirm the partisan accounts (Fervers et al., 2016; Potrafke,

2010).

However, some authors (e.g. Huber and Stephens, 2001: p. 270; Herwartz, & Theilen,

2014) have found evidence of a relationship between the partisan makeup of government and

health care expenditures. The differences in results could in part be explained by differences in

how partisanship is operationalized in those studies and different statistical methods applied.

Potrafke (2010) for example uses government ideology as an explanatory, a variable which ranges

from 1-5 based on the degree of dominance of right wing parties in government. This allows for

identifying differences between left and right parties, but neglects the role of Christian democrats

in accounting for developments of public health care expenditures. Huber and Stephens (2001: p.

53) on the other hand use cabinet portfolio of left and Christian democratic parties as an

explanatory variable. This has the upside of including Christian democrats, however, their

approach also fails to include right parties. This is at least questionable; right wing parties are often

the actors most likely to pursue retrenchment. Excluding right parties from the analysis could

potentially understate the role of partisanship (Alan and Scruggs, 2004: p. 504).

These studies have a number of conceptual limitations. The majority of the studies

reviewed thus far have analysed retrenchment in health care by looking at the shifts in financial

burdens. That is, they have looked at how the public share of health care spending has changed

over time. However, health care as an area of social policy differs significantly from other cash

benefits social programs. The numerous actors involved, the set of regulations in place regarding

remuneration of providers and coverage, the range of services covered by different insurance plans

in addition to the types of health care resources available in a country, are all decisions that could

16 for what services are therefore not the only relevant changes governments make with regards to

health care. This follows from the fact that healthcare is primarily about services, and not about

providing income replacement. This calls for a different approach to studying retrenchment in

healthcare. One that takes a broader view of healthcare and does not relegate itself to looking at

financing.

There are studies that have reckoned with the difference between cash benefits and services. In this regard, Bambra’s (2005) approach to the study of health care politics tries to

elaborate on this distinction. Bambra argues that welfare states differ with regard to how much

value they place on service provision or cash benefits. Some welfare states, notably those that

belong to the social democratic welfare regime, spend more on services and cash benefits, whereas

liberal and conservatives spend comparatively little on services. Unlike other authors

(Esping-Andersen, 1990; Ferreira, 1996) who have classified welfare states based on cash benefits

schemes, she classifies welfare states based on the types of in-kind benefits they provide. Taking

a more indirect approach, some authors have also linked the specific political traditions of

countries to differences in health outcomes. In this line of research, the argument goes as follows:

Belonging to a specific welfare regime implies presence of a particular political tradition, i.e. social

democratic, Christian democratic and liberal traditions. These political traditions in turn structure

social outcomes through the types of welfare arrangements that are likely to be in place. Lastly,

these social outcomes affect health outcomes (Hurrelmann et al., 2011; Eikemo et al., 2008).

This is something Navarro and Shi (2001) argue as well. Examining the significance of

partisanship and policies implemented by parties in government on inequality, and by extension

their [political parties’] impact on health inequalities. They conclude that, political parties in

government affect levels of inequality though redistributive policies they implement. This in turn

affects concrete health outcomes such as infant mortality. They find that social democrats are both

most inclined to redistribute and also associated with the highest scores for health outcome

indicators. Furthermore, the Christian democratic and liberal tradition also differ with regards to

how much they redistribute and the central institutions for delivering and organising health care

(Navarro & Shi, 2001). These studies thus suggest that politics seems to matter not only for

expenditure levels. Instead, politics also has implications for how services are organised and these

choices result in different outcomes. There are thus also qualitative differences between how

17 Esping-Andersen (1990, chapter 2), Korpi and Palme (2003), Korpi (1989; 1998) and others in the

power resource school who also emphasise the social rights accorded by different welfare states.

These qualitative differences have been studied using a social rights perspective. Social

citizenship refers to the rights and duties of individuals in society to benefits and services that

allow them to meet social needs enhance their capabilities and guarantee the resources necessary

to finance them. Social citizenship is based on three values, namely: reciprocity, inclusion and

trust (Taylor-Gooby, 2008: p. 5). Social rights are a critical component of citizenship in most

welfare states. As such, social rights are accorded to individuals as part of their rights as citizens.

Social rights can, however, also be based on employment as is often the case for example with

schemes such as unemployment insurance (Korpi, 1989: p. 310). This is the case with Esping-Andersen’s conception (1990). According to him benefits are provided as social rights, i.e.

decommodifying, when they at least allow for an individual to exit the market freely and not

experience large drop-off in quality of living (Stephens, 2010: p. 512).

Health care can be commodified as well. Social citizenship in health care includes an

entitlement to health care and is fundamentally aimed at eliminating this commodification

(Bambra, Fox and Scott-Samuel, 2006: p. 188). It is conceivable that the forces exerting downward

pressure on welfare states, also result in a reduction in the degree to which health care can be

provided as a social right. To empirically verify this claim, a number of aspects of health care

systems can be studied. Health care systems can be classified along three dimensions: service

provision, financing and regulation. Service provision entails the main health services, i.e.

inpatient and outpatient care, dental care and provision of pharmaceuticals. Financing pertains to

method of financing health care, e.g. social insurance, taxes or private and out of pocket expenses.

Lastly, regulation pertains to coverage, access of users to provider’s services and remuneration of

providers (Böhm et al., 2013: p. 260). These three dimensions can be used to gauge the degree to

which health care is commodified, or decommodified.

Some researchers have tried to map these qualitative differences and tried to find

distinctions in health care policy output. Montanari and Nelson (2013a), for instance, have

examined the role of partisanship in shaping healthcare reform. Approaching the topic via a social citizenship perspective, they focused on service provision. Their approach differs from Bambra’s

18 commodification and decommodification in health care is a function of whether services are

privately or publicly provided, and whether provision is privately or publicly organized. Publicness

indicates collective risk sharing. Bambra equates this with smaller probabilities of exclusion or

being denied important services which could be more prevalent in private schemes. But this is at

odds with studies that find that retrenchment and restructuring is often more probable and severe

in national health systems (NHS) (Giaimo, 2001: pp. 339-340). This effect is likely mediated by

private or public financing. Therefore, the difference between private and public coverage is a

fruitful way to classify health care systems. It is not the most suitable way to study retrenchment

though. Because health care is fundamentally about service provision. Whether services are

organised publicly or privately, whether costs are public or private matters of course. However,

they need not have any bearing on the degree to which health care can be provided as a social right.

Accounting for service provision in research is thus a more promising track.

2.4 Hypotheses

Having argued that studies of retrenchment in health care should incorporate more facets of health

care than financing, the specific expectations to be tested are more ambiguous. There are

theoretically grounded reasons for why partisanship could matter in health care. What is apparent,

though, is that health care is a policy area where partisanship may matter, but in more constrained

ways than in other policy areas. Jensen (2011: p. 913) provides a theoretical account of the different

preferences of left and right wing parties in health care. He posits that health care politics differ

from the politics of other areas of social policy, which have a more direct link to the labour market.

This is a function of generic social risks being correlated with income, whereas health risks are

only weakly correlated with income, and instead, mainly related to life-course risks. Furthermore,

right wing parties practice a form of marketization via compensation. This essentially means that

they will – for electoral reasons – spend roughly as much as the left. Right parties will behave this

way in order to avoid alienating middle class voters who would otherwise be harmed by pure

private provision and financing of health care. However, they will do their best to ensure private

or market based health provision, i.e. through supplementary systems of health care. This has two

advantages: private provision is likely to be used by high incomes and second may instil in the

population a form of market values and loyalties (in some the opposite of broad solidarities

19 healthcare is going to differ to a degree from other policy areas. It will not be based entirely on the

distribution of risks.

Gingrich’s (2011) provides a comparable account of policy preferences of left, right and confessional party’s. According to her, left and right wing parties organise markets for public

services differently in ways that reflect their own relative ideological predispositions. Accordingly,

left parties are more likely to favour linking the fates and risks of individuals in different classes,

so as to engender collective solidarity. Right parties, in contrast, favour more private involvement

and greater competition, less generous schemes and are more likely to pursue reforms that

fragment risks (Gingrich, 2011: pp. 37-38). These changes are often independent of private or

public financing.

Therefore, left wing parties will likely support public provision of health care, public

funding of health care and universal and broad coverage. Confessional and right parties will likely

be more willing to have a larger share of health care financing privately taken care of, be more

willing to introduce and tolerate supplemental systems and more likely to fragment risks where

possible. To test for the results of these different preferences on health care, the impact of partisan

makeup of government on the three dimensions of health care systems will be tested Based on the

following reading, the following hypotheses have been formulated:

The first hypothesis tests the dimension of health care where political contestation should

be most similar to that of other social programs. That is because the financing of health care is

fundamentally also about how risks are shared. To test for the differences between left,

confessional and secular right wing parties on health care financing, the first hypothesis is as

follows:

H1a: Left party cabinet seat shares is associated with increases in the public share of HCE. H1b: Confessional party cabinet seat shares is associated with smaller increases in the public share of HCE.

H1c: Secular and conservative right party cabinet seat shares are associated with stabilisation or small increases in the public share of HCE.

Hypothesis two and three will be used to test for the effects of the partisan makeup of government

on the availability of health care resources, which are critical for ensuring the social right to health

20 Taking Montanari and Nelson (2013a; 2013b) as starting point, and considering what previous

studies have shown about health care regimes, the following hypotheses has been formulated:

H2a: Left and Confessional party participation in cabinets are associated with increases in the number health care resources available.

H2b: Secular and conservative right party cabinet seat share is associated with weaker growth, or even declines in the number of health care resources available.

H 3a: Left parties cabinet seat shares is most strongly associated with increases in employment in health care sector.

H3b: Confessional party cabinet seat share is less so associated with increases in employment in health care sector.

H3c: Secular and conservative right parties are associated with the smallest increase – or potentially even with decreases – in employment in the health care sector.

Hypothesis four tests the effects of partisanship on regulation of access to health care. It extends

the argument from hypothesis one. Specifically assuming that different parties have different

degrees of preference and commitment vis-à-vis types of health insurance coverage. Even if parties

do not differ on how they finance health care, they should care whether or not health insurance is

privately organized or publicly organized. As such, hypothesis 4 is as follows:

H4a: Left party cabinet seat share is associated with the largest share of the population covered and the largest share covered in public schemes.

H4b: Confessional party cabinet shares are associated with smaller shares of the population covered and smaller shares covered in public schemes.

This is expected to be a result of Christian democrats’ commitment to the principle of subsidiarity

and their preference for the social insurance model (Van Kersbergen, 1995: p. 2).

H4c: Secular and conservative right parties are associated with the smallest shares of the population covered and coverage of a smaller share of the population in public schemes.

Hypothesis 5 tests a claim advanced by the new politics theory. It tests whether or not path

dependency explains developments in health care. One of the takeaways from the new politics

thesis is that welfare programs are resistant to change and that they are path dependent. The fifth

hypothesis is thus as follows:

21

H5b: The value of total health care expenditure in 1981 is associated with public share of health care financing in the period analysed.

H5c: The values of health care resources in 1981 are associated with health care resources in the period analysed.

H5d: The value of coverage in 1981 is associated with coverage in the period analysed.

In accordance with the power resource theory, labour unions are assumed to pursue similar

outcomes as left parties. Hence the expected association between trade union density and the

various outcome variables is in the same direction as with left parties.

3. Methodology

The research design used for this study will be a Large-N statistical analysis. The aim of this study

is to test whether the power resource theory or the new politics theory hold up as explanations for

the developments in the health care system of various OECD members. The goal is thus

explanatory in nature. Additionally, this study tries to replicate and test claims advanced by

previous studies for robustness (Leavy, 2017: p. 89). The politics of health care can be studied

using multiple designs, such as Small-N research designs, e.g. by performing single case studies Table 1: Summary of hypotheses

Variable Expected association

Hypothesis 1 Left cabinet share

Christian democratic cabinet share

+ +

Right cabinet share 0/+

Hypothesis 2

Left cabinet share +

Christian democrat 0/+

Right cabinet share -/0

Hypothesis 3 Left cabinet share

Christian democrat cabinet share

+ +

Right cabinet share -/0

Hypothesis 4

Left cabinet share +

Christian democratic cabinet share 0/+

Right cabinet share 0

Hypothesis 5

22 or comparative case study designs. These designs lend themselves to accounting for particular

outcomes, or identifying the motivations of actors involved in the process. For establishing general

patterns, however, Large-N designs are more suitable. This applies to the current study, as the goal

is to gauge whether there is a relationship between partisanship and organization of health care.

To accomplish this, this study compares of a large number of cases on a limited number of relevant

variables across a sufficiently large number of years (Toshkov, 2016: p. 256; Huber & Stephens,

2001: p. 37).

This thesis will analyse pooled data, that is, time-series-cross-sectional (TSCS) data. It

includes 33 time periods and 21 units, which yields (in the most optimal scenario) 735 observed

values per variable. The specific statistical analysis technique used is linear regression. TSCS have

observations on set number of units, in these studies countries are units, for multiple time periods.

Ordinary least squares (OLS) models cannot be carried out, or at least yield inaccurate estimates,

without regard for the fact that time-series data in TSCS likely violates core assumptions of the

OLS models. In particular, the assumptions of homoscedasticity and an absence of correlation of

standard errors in units at different time periods is potentially violated as observations are rarely

independent of each other (Beck and Katz, 1995: pp. 534-636). The use of panel corrected standard

errors (PCSE) helps to account for the heteroscedasticity and autocorrelation in standard errors

(Plümper, Troeger & Manow, 2005: p. 330). Using PCSE with a lagged dependent variable can

counteract these deficiencies of TSCS. However, the inclusion of the lagged dependent variable

as an explanatory variable can also be problematic, as this could artificially reduce the explanatory

power of other independent variables. So all the tests will also be conducted by differencing the

dependent variables. These additional tests serve as a robustness check. (Janoski & Isaac, 1993: p.

33).

The research design applied in this study has the advantage of being highly reliable. The

variables constructed and results produced using this data can be replicated by other scholars. The

data used for this study is freely available from authoritative organizations such as the OECD.

Regarding validity, the results are only generalizable to a set of industrialised democratic countries. So this study’s external validity is limited to the set of countries studied and other similar countries.

Another limitation of TSCS includes the somewhat uncertain validity of inferences across cases.

23 so for other units. This is an innate feature of TCSC and has to be considered when interpreting

results.

3.1 Case selection and operationalization

Cases have been selected for their theoretical relevance and availability of data to conduct analysis.

The analysis includes 21 members of the OECD from 1981 until 2014. This is an appropriate

starting point as the 1970s are often considered the end of the old politics era, signalling the

paradigm shift to the new politics era. The following countries included in the analysis: Australia,

Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Japan, the

Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom and

the United States. These countries are highly comparable on the theoretically relevant dimensions.

This means that all of these countries are industrial welfare states, and all countries were

democracies in the period under analysis. This makes the partisan accounts potentially relevant.

Some scholars prefer to exclude countries such as Portugal, Greece and Spain from the analysis;

they are not mature democracies and thus the dynamics of democratic politics may differ in those

countries (Huber and Stephens, 2001: p. 33). It is conceivable the shift to the new politics context

did not arrive in these countries at the same period in time it did for other OECD countries. As

such, these cases may inflate the effect of the power resource account. A number of other studies

include these countries however. Therefore, in the interest of comparability, the analysis conducted

includes Spain, Greece and Portugal. The tests will also be run excluding Spain, Portugal and

Greece to see if excluding these countries changes the results substantially.

3.2 Dependent variable

In debates about welfare retrenchment or resilience, the exact operationalization of the dependent

variable used could affect the results. Using aggregate or per capita expenditure data, using

replacement rates or net replacement rates yields different results (Allan and Scruggs, 2004;

Green-Pedersen, 2004; Esping-Andersen, 1990; Starke, 2006: p. 112). An examination of the

dependent variable used in studies of retrenchment of health care shows numerous authors using

public share of health care as dependent variable (Jordan, 2011; Potrafke, 2010). The public share

does not incorporate important features such as tax expenditures, subsidies or other more nuanced

24 organized, how costs and risk are distributed and shared (Brady et al, 2016: pp. 356-357).

Therefore, to gauge retrenchment in the financing of health care, the public share of health care

expenditures is used.

It is worth noting that retrenchment in these studies does not mean reductions in total health

care spending. Retrenchment reflects a decline in the public share of total healthcare spending, or

a decline in the public share of health spending as a percentage of GDP. This difference between

the specific ways of measuring it could have consequences: when the public share is expressed as

a share of GDP, the public share of health care may decline or increase irrespective of changes to

health care expenditures. This would not be the case when public health care expenses are

expressed as a share of overall health care expenses. Therefore, to gauge retrenchment in the

financing of health care, the public share of health care expenditures is used for this study. As

health care financing is but one dimension that characterizes the performance of health care

systems, the other two dimensions, regulation and health care provision, need to be accounted for

as well. Montanari & Nelson (2013a: pp. 261-262) operationalized health care provision as an

additive index, which is comprised of: health employment (number of nurses and physicians per

1000 inhabitants), hospital beds and medical technology (additive index of five categories of

medical technology per 1000 inhabitants). For this study, health care resources are operationalized

in the following two things: first, the number of physicians (additive index of nurses and physicians

per 1.000 residents). Second, the number of hospital bed. This is also an additive index comprising

the number curative and hospital beds per 1.000 residents. The variable health employment is also

included to gauge the importance of health care and social employment in the economy. This

variable is expressed as health care and social employment as a share of overall civilian

employment (OECD, 2016). Lastly, for regulation, this study includes an additive index of

coverage in public scheme and overall coverage. The score ranges from 0 to 200. This variable is

meant to give an indication of how accessible the health care system is. As is customary, this study

includes lagged values of all variables to account for time lag between changes in partisan

distribution of power and policy responses (Fervers et al., 2016: p. 365).

3.3 Independent variable

For the main independent variable of interest, partisan power, previous studies have used multiple

25 at cabinet seat shares of left, right and Christian democratic parties. This approach is an

appropriate way of studying power resources. This study will use the cabinet composition as the

main measure of partisanship. However, it is important to note that there are other approaches to

operationalizing this variable. Another method of operationalizing cabinet composition is the

Schmidt index for government ideology. It is a five-point scale indicating dominance of right and

centre parties in government. The value 1 indicates hegemony, 2 indicates dominance of the right,

3 indicates parity, 4 dominance of the left and 5 hegemony of the left. A notable drawback of the

Schmidt index is that it does not include an independent measure of Christian democrats in

government. The assumption underlying the Schmidt index seems to be that the difference between

left and right wing parties is the only relevant one. This makes the Schmidt index an unsatisfactory

indicator for this study. However, a number of other studies into health care retrenchment use the

Schmidt index. In the interest of comparability, the tests will also be run using Schmidt index to

test whether this significantly alters the estimation of partisan effects.

The other main power resource independent variables used will be unionization rate. This

is a superior and more relevant approximation of union strength than other measures such as

collective bargaining coverage rates, or wage bargaining centralization. It directly relates to union’s strength at that moment. Health insurance is an important fringe benefit in some countries.

However, this is often not the case. Using unionization rate should capture the effects of union

strength for countries where health care is a fringe benefit and where health insurance is provided

by the government. The per capita GDP growth rate is also included to account for health care

spending being driven by increases in income and improvements in the overall economy. The net

government deficit is included to account for budgetary pressures which might drive retrenchment.

Total social expenditure is included to capture whether or not potential retrenchment in health care

is compensated by increasing social expenditures in other programs. The dependency ratio is

included to control for the effects of elderly or underage population as explanatory factors of

budgetary pressure. The KOF globalisation index is also included in the analyses to assess whether

increased openness and international competition disciplines welfare states to pursue retrenchment

26 Additionally, this study has included a dummy variable for single party government (1 if

single party majority government, 0 for all other types of governments). This variable is included

to account for the fact that single party governments face fewer restraints in pursuing their ideal

policy goals than coalition or minority governments do. They do not have to rely on coalition

partners or others in parliament to legislate. I have also included an interaction term between single

party government and right wing cabinet share, this variable accounts for single party governments

formed by the right wing. Additionally, constitutional constraints are included as well. This

variable is included to assess whether states with more constraints in policymaking and veto

players present in the system exhibit some status quo bias. It hampered expansion in the old politics

era, and halted retrenchment in the new politics era (Huber, Ragin and Stephens, 2001: p. 32). The

ability of governments to unilaterally impose cost containment is lower in social and private health

insurance systems due to various factors, e.g. corporatism and the role of social and private actors

in regulating access and provision (Fervers et al, 2016: p. 202; Böhm et al, 2013). Whereas in

National Health Service systems, the capacity for governments to act is larger and they can more

directly enact cost containment measures. To account for this, this study uses state run health care

system as an additional control variable. The expectation is that countries with state run health care

systems will be successful in imposing cost containments and reducing the availability of health

care resources. Lastly, the values of the dependent variable at 1981 are included, in order to assess

whether path dependency accounts for outcomes. This test is meant to rule out whether the

arrangements in 1981 explain the outcome in 2014.

Table 2: Summary of association with non-power resource independent variables

Control variable Expected association

Social expenditure -

Deficit -

Dependency ratio +

GDP growth +

Single government -/+

Right wing single party government -

Globalization -

Centralization of health care system -

27

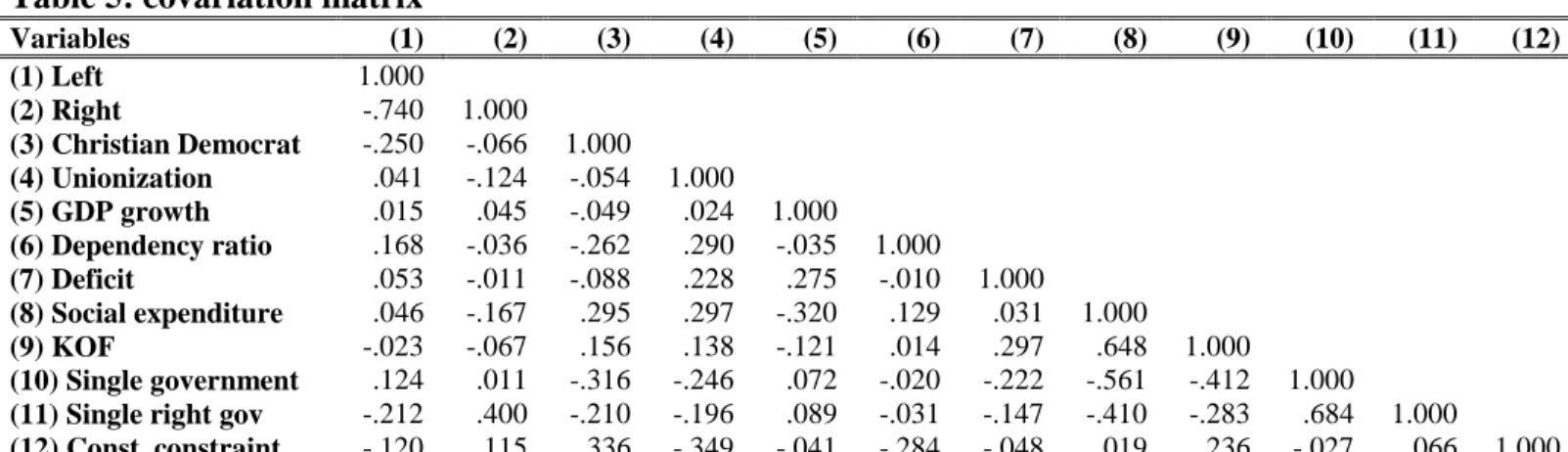

Table 3: Overview of variables used

Operationalization Source

Dependent variable

Health care financing Share of total health care expenditures that is publicly financed OECD (2017c)

Total health care expenditure as a percentage of GDP

Health care regulation Additive index combining share covered by the largest public

scheme and overall share covered with health insurance

OECD (2017c)

Health care resources Hospital beds per 1.000 inhabitants combined with curative care beds

per 1.000 inhabitants

OECD (2017c)

Physicians per 1.000 inhabitants combined with nurses per 1.000

inhabitants

Health and social service employment as a share of civilian

employment

Independent variable

Left cabinet Share of cabinet seats held by social democratic parties and parties

to their left

Swank (2013)

Right cabinet Share of cabinet seats held by secular and conservative right wing

parties

Swank (2013)

Christian democratic cabinet

Share of cabinet seats held by Christian democratic parties Swank (2013)

Schmidt index Cabinet composition: (1) hegemony of right-wing (and centre)

parties, (2) dominance of right-wing (and centre) parties, (3)

balance of power between left and right, (4) dominance of

democratic and other left par-ties, (5) hegemony of

social-democratic and other left parties.

Armingeon et al (2017)

Union density Net union membership as a proportion of wage and salary earners in

employment.

Visser (2016)

GDP growth Growth of real GDP, percent change from previous year OECD (2017b)

Dependency ratio Age dependency ratio is the ratio of dependents–people younger than

15 or older than 64–to the working-age population–those ages 15-64.

Jan et al (2018)

Social security expenditures Total public and mandatory private social expenditure as a percentage of GDP.

OECD (2017a)

Government deficit Annual deficit (overall balance / net lending of general government)

as a percent-age of GDP.