Psychiatric Symptoms in Preadolescents With Musculoskeletal Pain and

Fibromyalgia

Marja Mikkelsson, MD*; Andre Sourander, MD, PhD‡; Jorma Piha, MD, PhD‡§; and

Jouko J. Salminen, MD, PhD

i

ABSTRACT. Objectives. To study the association of musculoskeletal pain with emotional and behavioral problems, especially depressive symptoms in Finnish preadolescents.

Study Design. A structured pain questionnaire was completed by 1756 third- and fifth-grade schoolchildren for identifying children with widespread pain (WSP), children with neck pain (NP), and pain-free controls for the comparative study. There were 124 children with WSP (mean age, 10.7 years), 108 children with NP (mean age, 11.1 years), and 131 controls (mean age, 10.7 years) who completed the Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) and a sleep questionnaire. A blinded clinical ex-amination was done to detect fibromyalgia. For parental evaluation, the Child Behavior Checklist and a sociode-mographic questionnaire were used. For teacher evalua-tion the Teacher Report Form was used.

Results. Children with WSP had significantly higher total emotional and behavioral scores than controls, ac-cording to child and parent evaluation. A significant difference in the mean total CDI scores was also found between the WSP and NP groups. Children with fibro-myalgia had significantly higher CDI scores than the other children with WSP.

Conclusions. Musculoskeletal pain, especially fibro-myalgia, and depressive symptoms had high comorbid-ity. Pain and depressive symptoms should be recognized to prevent a chronic pain problem. Pediatrics 1997;100: 220 –227;musculoskeletal, pain, fibromyalgia, depression, preadolescent.

ABBREVIATIONS. WSP, widespread pain; NP, neck pain; CI, confidence interval; SD, standard deviation; CDI, Children’s De-pression Inventory; CBCL, Child Behavior Checklist; TRF, Teacher Report Form; E, externalizing; I, internalizing.

C

hronic widespread musculoskeletal pain and

tenderness, together with several

nonmuscu-loskeletal symptoms, are included in the

cri-teria for fibromyalgia,

1a syndrome causing

func-tional disability in adults as well as children and

adolescents.

2– 4Fibromyalgia with decreased pain

threshold

5,6may represent one extreme of the

wide-spread musculoskeletal pain disorders, although

symptoms previously described as specific to

fibro-myalgia have also been found in other patients with

widespread pain (WSP).

2Symptoms of depression

and anxiety are often found in patients with

fibro-myalgia,

7,8with the estimated lifetime prevalence of

depression ranging from 20% to 83% in clinical

stud-ies.

9 –12However, all these studies had small sample

sizes (from 7 to 35 patients) and the highest

preva-lence was found in the study with seven patients and

using a nonstructured interview method.

10Subjec-tive complaints of sleep disturbance are a prominent

feature of many with fibromyalgia,

13,14and

nonrapid-eye-movement sleep disturbance has been

hypothe-sized to be related to musculoskeletal symptoms of

fibromyalgia.

15The prevalence of depressive symptoms among

children in the United States and in Finland has been

estimated at 9.7% to 12.4%.

16 –18Symptoms of

depres-sion and anxiety have been found to a greater extent

in children with somatic complaints compared with

healthy controls.

19 –24Population studies

25,26or clinical

population studies of children with WSP

27have not

evaluated depression or other mood disturbances or

sleep disturbances.

The aim of the study was to evaluate the

associa-tion of musculoskeletal pain with emoassocia-tional and

be-havioral problems, especially symptoms of

depres-sion. To address this question, we compared children

with WSP with children with regional neck pain

(NP) and with pain-free controls. Because it is known

that cross-informant correlations are, in general, low

to moderate,

28,29we collected data from children,

par-ents, and teachers. Additionally, we were interested

in whether children with fibromyalgia had more

emotional and behavioral problems than other

chil-dren with WSP.

MATERIALS AND METHODS Study Design

Pick-up Procedure of Children With Musculoskeletal Pain

The study took place in Lahti, a town in southern Finland with 94 827 inhabitants (1995). All 21 primary schools were asked to take part in the study, but 2 schools refused. The Steiner school, the hospital school, and the schools for the hearing disabled, physically disabled, and the mentally handicapped were excluded because the methods used in this study were not suitable. All pupils from the third and fifth grades completed a pain question-naire, except those who were not at school on the day of the study.30

A structured pain questionnaire was developed and pretested for the study. The test-retest reliability of the questionnaire in

From the *Rehabilitation Center, Rheumatism Foundation Hospital, Heinola, Finland; ‡Department of Child Psychiatry, University Hospital of Turku, Turku, Finland; §University of Turku, Turku, Finland; and the iDepartment of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, University Hospital of Turku, Turku, Finland.

Received for publication Jun 6, 1996; accepted Dec 26, 1996.

Reprint requests to (M.M.) Rehabilitation Center, Rheumatism Foundation Hospital, 18120 Heinola, Finland.

detecting those who have pains at least once a week was good (k, .9).30The concurrent validity of the pain questionnaire was

exam-ined by comparing it with interviews of 31 third-grade and 25 fifth-grade children. The questions from the pain questionnaire were used as the basis of the interview. The children completed the pain questionnaire during a lesson and then were interviewed individually on the same day. The interviewer (M.M.) did not know the answers to the pain questionnaires. The observed agree-ment of pain questionnaire and interview technique was 86% [95% confidence interval (CI), 74% to 94%] andkwas .67.

During a lesson in the last week of March 1995, the pain questionnaire was completed by 1756 of the third- and fifth-grade schoolchildren, representing 82.9% of all schoolchildren of these grades in Lahti. The mean age of the third-grade children was 9.8 [standard deviation (SD), .34] years, and the mean age of the fifth-grade children 11.8 (SD, .37) years. There were questions about whether they had pain or aches during the previous 3 months (“since Christmas”) in the neck, lower back, lower extrem-ities, or other regional areas (upper extremextrem-ities, chest, upper back, or buttocks). They were also asked how often they have muscu-loskeletal pain and aches in these areas (almost every day, more than once a week, once a week, once a month, seldom, or never). Those who had pain at least once a week were classified into different pain groups on the basis of the painful area (neck, lower back, lower extremities, and other regional pain and WSP). WSP was determined according to the criteria for fibromyalgia1(Table

1). Those who seldom or never had pain formed the controls. If the children had pain attributable to an injury, they were asked to mark the area of the injury on the pain drawing with a different color. Pain attributable to injuries was not accepted for the pain classification.30Of those who had pain at least once a week, the

following two groups were selected for the comparative study: children with WSP and children with regional NP. The pain-free controls were randomly selected from the children who had pain seldom or never.

Comparative Study

The comparative study was carried out in May 1995. There were 132 children (7.5%) who reported WSP, 114 children (6.5%) with NP, and 506 children (28.8%) having pain seldom or never. For the children with WSP, sex- and age-matched controls were sought from the 506 children having pain seldom or never and a sample of 131 sex- and age-matched controls was randomly se-lected. One child with WSP was excluded because a matched control could not be found for him. Because the number of chil-dren with NP was less than the number of chilchil-dren with WSP, we could not find sex- and age-matched pain controls for the WSP group from the NP group as we had planned.

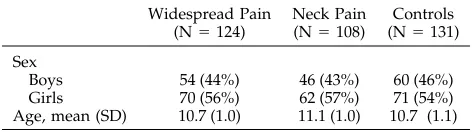

The age and sex distributions of the children in the comparative study are presented in Table 2. There was no significant difference between the age and sex distributions among the three groups. Of the 13 who were excluded, 8 were not at school on the day of examination. One child was excluded attributable to incorrect preliminary classification, two boys refused to take part in the clinical examination (one had a psychiatric illness), and two fa-thers refused to allow their sons to take part in the study. Of the

124 children with WSP, 22 (17.7%) fulfilled the criteria for fibro-myalgia.

Procedure

The Figure shows the procedure of the study. A physiatrist (M.M.) and a nurse went to the schools during May 1995. For the comparative study, a blinded clinical examination with tender point palpation was done of the 363 children by the physiatrist to detect fibromyalgia.1 Children were asked to

complete a Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI)31and a sleep

questionnaire.32The nurse supervised the children while they

completed the questionnaire. They were also asked to take home to their parents the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL)33,34

and a sociodemographic questionnaire with a prepaid enve-lope. Teachers were asked to complete the Teacher’s Report Form (TRF)35,36and mail it in a prepaid envelope to the research

group.

Instruments

Child Evaluation

Children’s Depression Inventory. Children were asked to com-plete the CDI, a well-known and validated instrument for de-tecting depression.31The Finnish version includes 26 of the 27

items in the English version. For ethical reasons the question about suicide was excluded.17The results were processed on the

basis of two cutoff points both previously used in epidemio-logical studies in Finland.17,18The cutoff point of$13, which has

also been used in a Swedish epidemiological study,37separated

out 12.4% of the 8- to 9-year-old Finnish children having a possible depressive disorder.17For the following studies, the

board of the National Epidemiological Study chose a cutoff point of 17, which was estimated to distinguish approximately 10% of the children as depressed. This cutoff point resulted in 7.6% of the 1186 8- to 9-year-old children having a possible depressive disorder on the basis of the CDI. A subpopulation of this study with their parents were interviewed. When the re-sults of the CDI and the interview were combined, 9.7% of the children were depressed.18A cutoff point$13 has since been

found to be the more appropriate than 17 for general screening purposes (Kresanov K, Tuominen J, Piha J, Almqvist F. Valida-tion of child psychiatric screening methods. Unpublished data). Sleep Questionnaire. The children also completed a sleep ques-tionnaire, which was a shorter, Finnish version of the

question-TABLE 1. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 Criteria for the Classification of Fibromyalgia* 1. History of widespread pain for at least 3 months.

Definition. Pain is considered widespread when all of the following are present: pain in the left side of the body, pain in the right side of the body, pain above the waist, and pain below the waist. In addition, axial skeletal pain (cervical spine or anterior chest or thoracic spine or low back) must be present. In this definition, shoulder and buttock pain is considered as pain for each involved side. Low back pain is considered lower segment pain.

2. Pain in 11 of 18 tender point sites on digital palpation with an approximate force of 4 kg. The subject must state that the palpation was painful.

Occiput: bilateral, at the suboccipital muscle insertions.

Low cervical: bilateral, at the anterior aspects of the intertransverse spaces at C5 to C7. Trapezius: bilateral, at the midpoint of the upper border.

Supraspinatus: bilateral, at origins, above the scapula spine near the medial border.

Second rib: bilateral, at the second costochondral junctions, just lateral to the junctions on upper surfaces. Lateral epicondyle: bilateral, 2 cm distal to the epicondyles.

Gluteal: bilateral, in upper outer quadrants of buttocks in anterior fold of muscle. Greater trochanter: bilateral, posterior to the trochanteric prominence.

Knee: bilateral, at the medial fat pad proximal to the joint line.

* The presence of a second clinical disorder does not exclude the diagnosis of fibromyalgia.

TABLE 2. Sex and Age Distributions of the Groups in the Comparative Study

Widespread Pain (N5124)

Neck Pain (N5108)

Controls (N5131)

Sex

Boys 54 (44%) 46 (43%) 60 (46%)

Girls 70 (56%) 62 (57%) 71 (54%)

naire developed by Cook and Burd32including six questions with

five to six alternative answers per question. The questions con-cerned day tiredness, problems in falling asleep, naps, nightmares, and problems of waking up in the night.

Parental Evaluation

Child Behavior Checklist. The CBCL is a questionnaire for par-ents consisting of 118 behavior items, each scored from 0 to 2. The validity and reliability of the instrument has been well docu-mented, eg, in the United States33,34and in Finland.38The

instru-ment gives a total behavior problem score and two broad-band

subscores, externalizing (E) and internalizing (I). The E-scale in-cludes variables such as aggression, disorderly conduct, delin-quent behavior, hyperactivity, and cruelty. The I-scale includes variables such as depression, anxiety, withdrawal, and somatiz-ing. The age- and sex-specific cutoff points at the 83rd percentile were used for the limit of normal range functioning.33,34,38Of the

parents, 302 (83.2%) returned the questionnaire. The analysis of dropouts showed that children of parents who returned the ques-tionnaire did not differ from all those included in the study according to the mean depression and sleep scores or mean total fibromyalgia tender point count. There were 24 (18.3%) from the

WSP group, 19 (17.6%) from the NP group, and 18 (13.7%) from the control group whose parental evaluation was missing.

Sociodemographic Questionnaire. The sociodemographic ques-tions dealt with the structure of the family, the number of chil-dren, and the education of parents. Parents were also asked about any diseases in the family and, if so, who has the disease. Demo-graphic data gathered from the returned questionnaires are pre-sented in Table 3.

Teacher Evaluation

Teacher Report Form. The TRF is a questionnaire for teachers consisting of 118 behavior problem items, each scored from 0 to 2.35,36The instrument gives total problem score and subscores like

the CBCL. There are age- and sex-specific cutoff points for the limit of normal range functioning, and the cutoff point at the 83rd percentile was used. The validity and reliability of the instrument have been well documented.36Teachers returned 276

question-naires (76.0%). Of the teachers’ evaluation, the data of 25 children (19.1%) of the WSP group, 30 children (27.8%) of the NP group, and 32 (24.4%) of the control group were missing. However, the mean depression and sleep score and the mean total fibromyalgia tender point count of those whose data were received from teach-ers did not differ significantly from the mean values of all children included in the study.

Statistical Methods

The descriptive values of variables were expressed as mean and standard deviations, median frequencies, or percentages. The most important descriptive values were expressed with confi-dence intervals. The differences between groups were evaluated by thex2test, Fisher’s exact test, the nonparametric

Mann-Whit-ney rank sum test, or the Wallis test. When the Kruskall-Wallis test revealed a significant difference (P,.05), the differ-ences between the groups were localized by the Bonferroni multiple comparison method. The statistical computation was performed with the SPSS statistical program package.

RESULTS

The significance of differences in family structures

between the groups in the comparative study

dichot-omously compared families with biological parents

versus other family structure. No significant

differ-ence was found. The groups did not differ on the

basis of parent’s educational status. Although there

was a minor difference in the percentages of sickness

in the families of WSP children compared with the

families of NP children and the control families, the

difference did not reach statistical significance (Table

3).

Comparison of Total Scores Among Different Groups

Depressive Symptoms and Sleep Problems

Table 4 shows the mean and median scores of the

CDI and the sleep questionnaire and the mean and

median counts of tender points of the three groups.

Both pain groups had higher scores on the CDI and

the sleep questionnaire and had more tender points

than the controls. The pain groups differed

signifi-cantly from the controls in all these variables. There

was also a significant difference in the mean total

scores of the CDI between the two pain groups.

Of the children with WSP, 37 (29.8%) had

depres-sion scores of

$

13 on the CDI, as did 17 (15.7%) of

the children with NP, and 3 (2.3%) of the controls.

On the basis of the higher cutoff point on the CDI

(

$

17), 22 (17.7%) of the children with WSP, 9 (8.3%)

of the children with NP, and 2 (1.5%) of the control

children had significant depressive symptoms. There

was a statistically significant difference between the

groups at both cutoff points (P

,

.001).

The mean depression and sleep scores of the 22

children with fibromyalgia, a subgroup of the

chil-dren with WSP, were 14.7 and 7.4, respectively. The

median of the CDI was 12.0 and of the sleep score 6.

The mean count of tender points in children with

fibromyalgia was 13.4. Children with fibromyalgia

had higher scores on the CDI than the other children

with WSP, and the difference between the groups

reached statistical significance (P

5

.001). The

differ-TABLE 3. Demographic Data

Widespread Pain (N5100)

Neck Pain (N589)

Controls (N5113)

Third grade

Boys (N558) 23 13 22

Girls (N585) 31 16 38

Fifth grade

Boys (N575) 22 24 29

Girls (N584) 24 36 24

Number of children at home

#2 67 (67%) 64 (72%) 75 (66%)

$3 33 (33%) 25 (28%) 38 (34%)

Family structure*

Biological parents 74 (74%) 67 (75%) 91 (81%)

One-parent family 19 (19%) 13 (15%) 10 (9%)

Remarried 7 (7%) 7 (8%) 9 (8%)

Institutional care or other 0 (0%) 1 (1%) 1 (1%)

Adoption 0 (0%) 1 (1%) 1 (1%)

Mother’s education

Comprehensive or/and vocational school 57 (57%) 49 (56%) 65 (65%)

Further or higher education 36 (36%) 36 (40%) 45 (45%)

Not known 7 (7%) 4 (4%) 3 (3%)

Father’s education

Comprehensive or/and vocational school 52 (52%) 44 (49%) 57 (51%)

Further or higher education 27 (27%) 31 (35%) 44 (37%)

Not known 21 (21%) 14 (16%) 14 (12%)

Sickness in family 20 (26%)† 14 (19%)‡ 21 (21%)§

* One observation was missing.

ence between mean tender point counts of children

with fibromyalgia and other children with WSP was

also statistically significant (P

,

.001).

Of the children with fibromyalgia, 10 (45.5%) had

a depressive symptom score on the CDI, whereas 27

(26.5%) of the other children with WSP had CDI

scores

$

13. These 10 children with fibromyalgia

rep-resented 27.0% of the children with WSP who scored

greater than the cutoff point of 13. Using the CDI

$

13 criterion for depressive symptoms, no significant

difference between children with fibromyalgia and

other children with WSP was identified (P

5

.12).

However, when the cutoff point of 17 was used, 8

children (36.4%) with fibromyalgia met the criterion,

whereas 14 (13.7%) of the other children with WSP

met this criterion. At this cutoff point the difference

between groups was significant (P

5

.026).

Parental Evaluation

Table 5 shows the mean raw scores of the CBCL for

the three groups and the statistical significance of the

differences among the groups. Children with WSP

and children with NP differed from the controls in

CBCL total scores, E-scores and I-scores, and in

sub-scores of withdrawn, somatic complaints, anxious/

depressive, social, attention, and aggressive behavior

problems. Differences between children with WSP

and children with NP were not statistically

signifi-cant.

We determined the effect of sex and school grade

on the CBCL scores. Differences between the sexes

on the third and fifth grades were not statistically

significant (P

5

.44 and P

5

.96, respectively).

Like-wise differences between children in the third

and fifth grades were not statistically significant

(P

5

.35).

Sixteen (16%) of the children with WSP, 14 (15.7%)

of the children with NP, and 10 (8.8%) of the controls

achieved scores more than the cutoff point. The

dif-ference in abnormal functioning between the groups

did not reach statistical significance. The effects of

age and sex on the difference in abnormal

function-ing were not significant.

There were 15 children with fibromyalgia whose

parents had completed the CBCL. On the basis of

median CBCL scores, children with fibromyalgia did

not differ from other children with WSP.

Of the children with fibromyalgia, 4 (26.7%)

achieved scores more than the cutoff point compared

with 12 (14.1%) of the other children with WSP. The

difference was not statistically significant.

Teacher Evaluation

Table 6 shows the mean raw TRF scores of the

three groups and the statistical significance of the

differences among the groups. Children with WSP

differed from controls in TRF total scores, E-scores,

and subscores of somatic complaints, attention, and

aggressive behavior problems.

Twenty (20.2%) of the children with WSP, 13

(16.7%) of the children with NP, and 8 (8.1%) of the

controls achieved scores more than the cutoff point.

With the

x

2test, the differences among the groups

reached statistical significance (P

5

.049).

Twenty-three (20.4%) of the third-grade children and 18

(10.8%) of the fifth-grade children scored more than

the cutoff point. There was not a significant

differ-ence between the two groups (P

5

.04).

TABLE 4. Mean and Median Values of Tender Points, Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) Scores, and Sleep Scores Widespread Pain (WSP)

(N5124)

Neck Pain (NP) (N5108)

Controls (C) (N5131)

P Value Between Groups, (Multiple Comparison)

Mean (SD) Median Mean (SD) Median Mean (SD) Median

Count of tender points 5.6 (4.8) 4 4.5 (4.4) 3 2.2 (3.2) 0 P,.0001 (WSP/C, NP/C)

CDI 10.0 (6.5) 10 7.7 (5.2) 7 4.5 (3.9) 4 P,.0001 (WSP/C, NP/C, WSP/NP)

Sleep score 5.7 (4.0) 5 4.2 (2.9) 4 2.2 (2.3) 2 P,.0001 (WSP/C, NP/C)

* WSP group includes the children with fibromyalgia.

TABLE 5. Mean Raw Scores on Child Behavior Checklist and Statistical Significances Between Groups Widespread Pain

(WSP)*

Neck Pain (NP) Controls (C) P Value Between Groups,

Both Sexes Combined (Multiple Comparison) Boys

(N545) Mean (SD)

Girls (N555) Mean (SD)

Boys (N537) Mean (SD)

Girls (N552) Mean (SD)

Boys (N551) Mean (SD

Girls (N562) Mean (SD)

Total score 25.3 (17.0) 21.4 (13.0) 18.8 (12.4) 24.5 (17.2) 16.1 (15.3) 16.6 (16.3) P,.0001 (WSP/C, NP/C)

External score 9.1 (6.5) 6.6 (4.5) 6.5 (5.3) 7.0 (5.7) 5.7 (6.1) 5.0 (5.5) P,.001 (WSP/C, NP/C)

Internal score 6.8 (6.0) 7.4 (5.5) 5.8 (5.6) 8.7 (7.0) 4.8 (5.3) 5.0 (5.7) P,.0001 (WSP/C, NP/C)

Subscores

Withdrawn 1.8 (2.1) 1.4 (1.4) 1.6 (2.4) 1.9 (2.3) 1.5 (2.2) 1.2 (2.0) .049

Somatic 2.1 (1.6) 3.0 (2.6) 2.2 (1.9) 3.2 (2.2) 1.6 (1.9) 1.7 (1.8) P,.0001 (WSP/C, NP/C)

Anxious/depressive 3.0 (3.7) 3.2 (2.9) 2.1 (2.4) 3.8 (3.9) 1.8 (2.5) 2.2 (3.0) P,.0001 (WSP/C, NP/C)

Social 1.8 (1.8) 1.4 (1.4) 1.2 (1.3) 1.4 (1.7) 1.1 (2.2) 1.4 (2.2) .009 (WSP/C)

Thought 0.5 (0.9) 0.3 (0.6) 0.2 (0.6) 0.6 (1.5) 0.2 (0.4) 0.3 (0.6) NS

Attention 3.8 (2.9) 2.9 (2.3) 2.4 (2.3) 3.4 (2.4) 2.4 (3.0) 2.3 (2.7) P,.001 (WSP/C, NP/C)

Delinquent 1.4 (1.6) 0.8 (0.9) 1.3 (1.4) 1.1 (1.5) 1.2 (1.6) 0.6 (1.1) NS

Aggressive 7.7 (5.2) 5.8 (4.0) 5.2 (4.5) 5.8 (4.6) 4.6 (4.9) 4.4 (4.8) .0001 (WSP/C, NP/C)

There were 12 children with fibromyalgia whose

teachers returned the questionnaire. The median of

the TRF total score was 16 in children with

fibromy-algia and 12 in other children with WSP. However,

the difference did not reach statistical significance

(P

5

.63).

Of the children with fibromyalgia, 4 (33.3%) were

rated more than the cutoff point by teachers, whereas

14 (16.1%) of the other children with WSP achieved

scores more than the TRF cutoff point.

DISCUSSION

Our study shows that children with WSP had

more emotional and behavioral problems than

con-trols, according to the children themselves and

par-ents. Furthermore, children with musculoskeletal

pain had depressive symptoms and sleep problems

to a greater extent than controls. In regard to

depres-sive symptoms, children with WSP achieved higher

mean scores than children with NP or controls on the

CDI. There were more children from the WSP group

who exceeded the cutoff level of depression

com-pared with controls. Moreover, the role of depressive

symptoms emerged in children with fibromyalgia.

Although children with WSP and NP rated higher

scores on the CDI, the mean scores still remained at

normal level. However, children with fibromyalgia

had a mean depression score more than the lower

cutoff point and more than one-third of children

with fibromyalgia reached the higher cutoff point.

Thus, musculoskeletal pain, especially fibromyalgia,

and symptoms of depression had high comorbidity.

Comparing adult fibromyalgia patients with other

patients with chronic pain, there was not a

signifi-cant difference in depression or anxiety symptoms

on the SCL-90R scale. Patients with fibromyalgia had

a greater extent of somatization.

39In that study the

chronic pain group included regional chronic pain

patients but the duration of pain was at least 6

months compared with 3 months in our study. In our

study, not only children with fibromyalgia but all the

children with WSP had significantly higher

depres-sive symptom scores than children with NP, and the

difference persisted when the questions about

so-matic symptoms were excluded.

According to parents and teachers, both pain

groups had more aggressive behavior problems than

controls. Depression in childhood typically includes

irritability.

16One explanation is that aggressive

be-havior is a manifestation of depressive mood in

chil-dren. Sleep disturbance, found to a greater extent in

children with pain, may also be one of the depressive

symptoms. It has been reported that a child with

depressive symptoms is more aware of sleep

distur-bance than parents realize.

16As far as we know, this is the first

population-based epidemiological study of the associations

be-tween widespread musculoskeletal pain and

psychi-atric symptoms in children. In a clinical study of

psychosomatic musculoskeletal pain, clinical

depres-sion (CDI

$

17) was lower than in our study among

children with WSP (11% vs 17.7%). If we compare the

mean rate of depressive symptoms of both of our

pain groups to that in the clinical study, the rate of

depressive symptoms is similar (12% vs 11%).

40The

results of the present study raise clinically important

questions, eg, how to recognize depression behind

multiple somatic complaints in children, to what

ex-tent do milder depressive symptoms become more

serious, and what is the effect of age on the process?

This cross-sectional study is unable to give answers

to these questions and, as some authors have pointed

out, longitudinal studies of somatization and pain

problems in children are needed.

27,41Importantly, the

present study design does not imply causalities

between

musculoskeletal

pain

and

depressive

symptoms.

One problem in previous epidemiological studies

of pediatric pain has been that classification of

sim-ple occurrence or nonoccurrence of pain has been

used.

42In our study we classified pain according to

extent and frequency. The shortcoming of our study

was that severity of pain was not determined in the

pickup procedure. Another shortcoming was that

information about behavioral symptoms was based

on questionnaires, a method which does not give a

clinical diagnosis. However, it was not possible to

carry out diagnostic child interviews in this

popula-tion-based study. The assessment of the validity of

the pain questionnaire was limited because we did

TABLE 6. Mean Raw Scores on Teacher Report Form and Statistical Significances Between Groups Widespread Pain

(WSP)*

Neck Pain (NP) Controls (C) P Value Between Groups,

Both Sexes Combined (Multiple Comparison) Boys

(N545) Mean (SD)

Girls (N554) Mean (SD)

Boys (N532) Mean (SD)

Girls (N546) Mean (SD)

Boys (N547) Mean (SD

Girls (N552) Mean (SD)

Total score 21.4 (25.8) 23.1 (25.5) 21.2 (22.2) 18.5 (26.6) 16.1 (16.4) 11.9 (18.3) .027 (WSP/C) External score 6.7 (10.7) 6.5 (10.6) 7.9 (12.3) 4.6 (8.9) 4.8 (8.5) 1.5 (4.5) ,.001 (WSP/C)

Internal score 4.9 (5.6) 7.9 (7.9) 4.7 (4.7) 5.9 (7.7) 4.0 (3.6) 5.9 (7.9) NS

Subscores

Withdrawn 1.2 (1.7) 2.0 (2.9) 1.8 (2.6) 1.5 (2.2) 1.7 (2.1) 2.2 (3.5) NS

Somatic 1.0 (1.9) 1.8 (2.5) 0.7 (0.9) 1.1 (2.1) 0.5 (0.8) 0.6 (1.6) .0064 (WSP/C)

Anxious/depressive 2.7 (3.3) 4.3 (4.9) 2.4 (2.8) 3.5 (4.7) 1.9 (2.3) 3.2 (4.2) NS

Social 2.2 (3.7) 2.6 (3.7) 1.5 (2.1) 2.2 (3.6) 1.2 (1.8) 1.4 (2.7) NS

Thought 0.4 (1.3) 0.3 (0.7) 0.2 (0.5) 0.3 (1.0) 0.3 (0.8) 0.2 (0.8) NS

Attention 7.3 (8.1) 6.0 (7.1) 6.7 (7.1) 5.3 (8.3) 5.7 (6.2) 3.2 (5.5) .04 (WSP/C)

Delinquent 0.7 (1.6) 1.3 (2.2) 1.2 (2.0) 0.6 (1.2) 0.6 (1.0) 0.2 (0.5) NS

Aggressive 6.0 (9.4) 5.2 (8.9) 6.3 (10.4) 4.1 (8.1) 4.3 (7.7) 1.3 (4.1) .0012 (WSP/C)

not test the three-month recall of pain among

chil-dren with pain diaries or collect reports from

par-ents. The fairly high prevalence rates of

musculoskel-etal pain in our study may raise a question whether

Finnish children are prone to pain. However, Finnish

children have reported local musculoskeletal pain

symptoms to the same amount or less than children

in other European countries.

43– 46Probably, children

are reporting fairly low intensities of pain symptoms.

Both fibromyalgia and depression may be

patho-physiological disturbances related to serotonin

me-tabolism.

47,48However, only some adult fibromyalgia

patients have reacted as depression patients in the

dexamethasone suppression test.

49,50The methods of

this study are not accurate enough to make a

diag-nosis of depression, but the results indicate that

de-pression should be kept in mind when children

com-plain of musculoskeletal symptoms. The methods of

this study do not exclude somatic diseases, and

fol-low-up of the children will show any need for more

accurate examinations.

To prevent a chronic pain state from developing,

both depression

16and musculoskeletal pain should

be recognized and treated as early as possible. To

prevent the chronic pain syndrome in adulthood, it is

important to know whether chronic musculoskeletal

pain symptoms are already developed in childhood.

In a 30-month, prospective follow-up study of

fibro-myalgia in children, fibrofibro-myalgia symptoms had a

tendency to disappear spontaneously.

26This is

con-trary to the results of longitudinal studies in

adults,

51,52which show that only 9% to 25% of

pa-tients improve during follow-up, whereas 75% of

patients report an unchanged or worsened situation.

The results of our study provide evidence that

children with WSP form a heterogeneous group,

chil-dren with fibromyalgia representing those with more

tenderness and overpresenting depressive

symp-toms. In addition, children with NP showed a

ten-dency for an increased number of psychological

symptoms, and, in the future, our follow-up will

show whether children with NP develop multiple

musculoskeletal and/or behavioral symptoms. As

Wolfe

14has suggested, nociceptive input leading to

sustained hyperalgesia might be causally related to

fibromyalgia. High levels of psychological distress in

adult fibromyalgia patients and their families have

been found,

14and high levels of life stress found in

patients with fibromyalgia may affect psychological

responses.

53The present study suggests that there is

an association between musculoskeletal pain and

de-pressive symptoms in children. However, what is

most important is that both pain and depression in

children are recognized and treated to prevent the

limitations of a chronic pain problem.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by the Signe and Ane Gyllenberg Foundation.

We are also grateful to Mr Hannu Kautiainen, BA, for statistical assistance.

REFERENCES

1. Wolfe F, Smythe HA, Yunus MB, et al. The American College of Rheu-matology 1990 criteria for the classification of fibromyalgia: report of

the Multicenter Criteria Committee. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33:160 –172 2. Jacobsen S, Petersen IS, Danneskiold-Samsøe B. Clinical features in

patients with chronic muscle pain—with special reference to fibromy-algia. Scand J Rheumatol. 1993;22:69 –76

3. Hawley DJ, Wolfe F, Cathey MA. Pain, functional disability, and psy-chological status: a 12-month study of severity in fibromyalgia. J Rheu-matol. 1988;15:1551–1556

4. Yunus MB, Masi AT. Juvenile primary fibromyalgia syndrome. A clin-ical study of thirty-three patients and matched normal controls. Arthritis Rheum. 1985;28:138 –145

5. Mikkelsson M, Latikka P, Kautiainen H, Isomeri R, Isoma¨ki H. Muscle and bone pressure pain threshold and pain tolerance in fibromyalgia patients and controls. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1992;73:814 – 819 6. Tunks E, Crook J, Norman G, Kalaher S. Tender points in fibromyalgia.

Pain. 1988;34:11–19

7. Wolfe F, Cathey MA, Kleinheksel SM, et al. Psychological status in primary fibrositis and fibrositis associated with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1984;11:500 –506

8. Wolfe F, Ross K, Anderson J, Russel IJ, Hebert L. The prevalence and characteristics of fibromyalgia in the general population. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;1:19 –28

9. Hudson JI, Hudson MS, Pliner DL, Goldenberg DL, Pope HG Jr. Fibro-myalgia and major affective disorder: a controlled phenomenology and family history study. Am J Psychiatry. 1985;142:441– 446

10. Tariot PN, Yocum D, Kalin NH. Psychiatric disorders in fibromyalgia. Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143:812– 813

11. Kirmayer LJ, Robbins JM, Kapusta MA. Somatization and depression in fibromyalgia syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 1988;145:950 –954

12. Ahles TA, Khan SA, Yunus MB, Spiegel DA, Masi AT. Psychiatric status of patients with primary fibromyalgia, patients with rheumatoid arthri-tis, and subjects without pain: a blind comparison of DSM-III diagnoses. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:1721–1726

13. Waylonis GW, Heck W. Fibromyalgia syndrome. New associations. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1992;71:343–348

14. Wolfe F, Ross K, Anderson J, Russell IJ. Aspects of fibromyalgia in the general population: sex, pain threshold, and fibromyalgia symptoms. J Rheumatol. 1995;22:151–156

15. Moldofsky H, Scarisbrick P, England R, Smythe H. Musculoskeletal symptoms and non-REM sleep disturbance in patients with “fibrositis syndrome” and healthy subjects. Psychosom Med. 1975;4:341–351 16. Dolgan JI. Depression in children. Pediatr Ann. 1990;19:45–50 17. Almqvist F, Tuompo-Johansson E, Panelius E, Aronen E, Kairemo A-C.

Depressive symptoms according to the Children’s Depression Inven-tory developed by Kovacs. Reports of Psychiatrica Fennica. Report No. 91. 1991:47–52

18. Puura K, Tamminen T, Bredenberg P, Escartin T, et al. Psychiatric disturbances in children within the catchment area of Tampere Univer-sity Hospital. Foundation for Psychiatric Research. Publication Series 110 (in Finnish). Helsinki, Finland: Psychiatria Fennica Oy; 1995 19. Kowal A, Pritchard D. Psychological characteristics of children who

suffer from headache: a research note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1990; 31:637– 639

20. Stevenson J, Simpson J, Bailey V. Research note: recurrent headaches and stomachaches in preschool children. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1988;29:897–900

21. Tamminen TM, Bredenberg P, Escartin T, et al. Psychosomatic symp-toms in preadolescent children. Psychother Psychosom. 1991;56:70 –77 22. Walker LS, Greene JW. Negative life events and symptom resolution in

pediatric abdominal pain patients. J Pediatr Psychol. 1991;16:341–360 23. Wasserman AL, Whitington PF, Rivera FP. Psychogenic basis for

ab-dominal pain in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1988;27:179 –184

24. Zuckerman B, Stevenson J, Bailey V. Stomachaches and headaches in a community sample of preschool children. Pediatrics. 1987;79:677– 682 25. Buskila D, Press J, Gedalia A, et al. Assessment of non-articular

tender-ness and prevalence of fibromyalgia in children. J Rheumatol. 1993;20: 368 –370

26. Buskila D, Neumann L, Hershman E, Gedalia A, Press J, Sukenik S. Fibromyalgia syndrome—an outcome study. J Rheumatol. 1995;22: 525–528

27. Malleson PN, Al-Matar M, Petty RE. Idiopathic musculoskeletal pain syndromes in children. J Rheumatol. 1992;19:1786 –1789

28. Sourander A. Child Psychiatric Short-Term Inpatient Treatment. A Prospec-tive Study on Content and Outcome. Annales Universitatis Turkuensis, Ser. D, Medica-Odontologica; 1995:105–106; Thesis

30. Mikkelsson M, Salminen JJ, Kautiainen H. Joint hypermobility is not a contributing factor to musculoskeletal pain. J Rheumatol. 1996;23: 1963–1967

31. Kovacs M. Rating scales to assess depression in school-aged children. Acta Paedopsychiatr. 1980/81;46:305–315

32. Cook J, Burd L. Preliminary report on construction and validation of a pediatric sleep disturbance questionnaire. Percept Mot Skills. 1990;70: 259 –267

33. Achenbach TM, Edelbrock C. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist and Revised Child Behavior Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1983

34. Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist and 1991 Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1991 35. Achenbach TM, Edelbrock CS. Manual for the Teacher’s Report Form and Teacher Version of the Child Behavior Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1986

36. Achenbach TM. Manual for the Teacher’s Report Form and 1991 Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1991 37. Larsson B, Melin L. Prevalence and short-term stability of depressive

symptoms in schoolchildren. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1992;85:17–22 38. Almqvist F, Bredenberg P, Suominen I, Leijala H. Social kompetens och

beteendeproblem bland skolbarn och barnpsykiatriska patienter– en empirisk studie med CBCL. Nord J Psychiatry. 1988;42:311–319 39. Birnie DJ, Knipping AA, van Rijswijk MH, de Blecourt AC, de Voogd N.

Psychological aspects of fibromyalgia compared with chronic and non-chronic pain. J Rheumatol. 1991;18:1845–1848

40. Sherry DD, McGuire T, Mellins E, Salmonson K, Wallace CA, Nepom B. Psychosomatic musculoskeletal pain in childhood: clinical and psycho-logical analyses of 100 children. Pediatrics. 1991;88:1093–1099 41. Campo JV, Fritsch S. Somatization in children and adolescents. J Am

Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1994;33:1223–1235

42. Goodman JE, McGrath PJ. The epidemiology of pain in children and adolescents: a review. Pain. 1991;46:247–264

43. King A, Wold B, Tudor-Smith C, Harel Y. The Health of Youth—A Cross-National Survey. Canada: WHO Regional Publications; European Series No. 69. 1996:69

44. Balague F, Dutoit G, Waldburger M. Low back pain in schoolchildren. Scand J Rehabil Med. 1988;20:175–179

45. Fairbank JCT, Pynsent PB, van Poortvliet JA, Phillips H. Influence of anthropometric factors and joint laxity in the incidence of adolescent back pain. Spine. 1984;9:461– 464

46. Salminen JJ, Pentti J, Terho P. Low back pain and disability in 14-year-old schoolchildren. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1992;81:1035–1039

47. Russel IJ, Michalek JE, Viprais GA, Fletcher EM, Javors MA, Bowden CA. Platelet 3H-imipramine uptake receptor density and serum

seroto-nin levels in patients with fibromyalgia/fibrositis syndrome. J Rheuma-tol. 1992;19:104 –109

48. Meltzer HY, Lowy MT. The serotonin hypothesis of depression. In: Meltzer HY, ed. Psychopharmacology: The Third Generation of Progress. New York, NY: Raven Press; 1987:513–526

49. Griep EN, Boersma JW, de Kloet EP. Altered reactivity of the hypothal-amus-pituitary-adrenal axis in the primary fibromyalgia syndrome. J Rheumatol. 1993;20:469 – 474

50. Ferraccioli G, Cavalieri F, Salaffi F, et al. Neuroendocrinologic findings in primary fibromyalgia (soft tissue chronic pain syndrome) and in other chronic rheumatic conditions (rheumatoid arthritis, low back pain). J Rheumatol. 1990;17:869 – 873

51. Nørregaard J, Bu¨low PM, Prescott E, Jacobsen S, Danneskiold-Samsøe B. A 4-year follow-up study in fibromyalgia. Relationship to chronic fatigue syndrome. Scand J Rheumatol. 1993;22:35–38

52. Henriksson CM. Longterm effects of fibromyalgia in everyday life. A study of 56 patients. Scand J Rheumatol. 1994;23:36 – 41