R E S E A R C H A R T I C L E

Open Access

Limited utilization of serologic testing in patients

undergoing duodenal biopsy for celiac disease

Homer O Wiland 4th, Walter H Henricks and Thomas M Daly

*Abstract

Background:Clinical algorithms for the workup of celiac disease often recommend the use of serologic assays for initial screening, followed by duodenal biopsy for histologic confirmation. However, the majority of duodenal biopsies submitted to pathology for“rule out celiac”are negative. The objective of this study was to determine the underlying causes for this low diagnostic yield.

Methods:We performed a retrospective review of pathology reports from 1432 consecutive duodenal biopsies submitted for pathologic assessment to“rule out celiac”and correlated biopsy results with results for concurrent serologic testing for celiac autoantibodies.

Results:The majority of patients had no record of serologic testing prior to biopsy, and evidence of positive serology results was found in only 5% of patients. Most duodenal biopsies were submitted as part of a multi-site GI sampling strategy that included biopsies from other locations. In this context, serologic results correlated with the likelihood of significant duodenal and non-duodenal findings, and were also helpful in evaluating patients with in-determinate duodenal histology.

Conclusions:The presence of a positive screening test for celiac autoantibodies does not appear to be a major driver in the decision to submit duodenal biopsies for evaluation of celiac disease, which accounts for the low incidence of findings in these samples. In patients where celiac serology testing was performed, the results were a good predictor of the likelihood of findings on biopsy.

Keywords:Celiac disease, Serology, Duodenal biopsy, Utilization

Background

Celiac disease is one of the most common autoimmune diseases, with an estimated prevalence of approximately 1% in various populations [1-3]. The disease is caused by an autoimmune response to gluten which leads to pro-gressive villous atrophy in the small bowel, resulting in malabsorption. Gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms can be relatively nonspecific, such as diarrhea and abdominal pain. Systemic complications are common, and can in-clude iron deficiency anemia and fatigue. Accurate rec-ognition and diagnosis of celiac disease is important because implementation of a gluten-free diet can ameli-orate many symptoms. If left untreated, celiac disease is associated with increased mortality in adult life from a

range of causes, including autoimmune diseases and malignancy [4,5].

For patients with an appropriate clinical history, diag-nostic tools for the workup of celiac disease can be di-vided into three categories; serologic assays to measure celiac-associated autoantibodies, genetic assays to iden-tify HLA-DQ2 or -DQ8, and duodenal biopsy to docu-ment the presence of villous atrophy. Although many groups have published guidelines on the diagnosis and management of celiac disease and the role of testing in this process [6,7], surveys have found that there can be significant variation in adherence to these guidelines in different practice settings [8]. While the exact steps of the algorithms can vary slightly depending upon the spe-cific population being tested, most approaches recom-mend using serologic assays either prior to duodenal biopsy [9,10] or concurrently with biopsy in cases with a strong clinical suspicion [11].

* Correspondence:dalyt@ccf.org

Robert J. Tomsich Pathology and Laboratory Medicine Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Clinical Pathology, LL3-3, 9500 Euclid Avenue, 44195 Cleveland, OH, USA

The most commonly-used serologic assays measure autoantibodies against tissue transglutaminase (tTG), dea-midated gliadin (dGDN), and endomysial tissue (EMA). Antibodies against native gliadin are losing popularity be-cause of inferior performance when compared to the newer dGDN assays [12,13]. Although most assays meas-ure IgA antibodies against these targets, IgG versions are also available for use in patients with IgA deficiency, a dis-order commonly associated with celiac disease [14]. The diagnostic characteristics of celiac serology tests have been well-described in many populations, and in general show analytical performance sufficient for use as a screening test [15-18]. tTG-IgA and EMA-IgA assays have shown the best diagnostic performance in most studies, with pooled sensitivities of 89- 90% and specificities of 98 – 99% in a recent systematic review of the literature [16]. Recent studies have suggested that the use of serologic testing prior to endoscopy could potentially reduce the need for intestinal biopsy to diagnose celiac disease [19].

Given the high sensitivity and specificity of serologic testing, one would expect to find a fairly high diagnostic yield in duodenal biopsies for celiac disease. In a popula-tion with a disease prevalence of 1%, a test with the char-acteristics described above (90% Sn, 98% Sp) would have an expected positive predictive value (PPV) of roughly 47%. However, the historical experience at our institution has been that the majority of duodenal biopsies submitted for“rule out celiac”are histologically normal. In an effort to understand the causes for this discrepancy, we retro-spectively examined the utilization of celiac serology in a cohort of patients who had been sent for duodenal biopsy.

Methods

Case finding

An automated query was run on the pathology laboratory information system (CoPath, Cerner Corp, Waltham MA) to identify any biopsy submissions that contained the words“celiac”,“gluten”, or“sprue”in the clinical data field (which is the field completed by the ordering physician to describe the reason for the submission). Case finding and subsequent chart review were performed following proto-col approval by the institutional review board of the Cleveland Clinic Foundation. All biopsy specimens were initially reviewed and signed out by one of twelve path-ology staff members belonging to the subspecialty gastro-intestinal pathology group at the Cleveland Clinic, each of whom has fellowship training in gastrointestinal pathology or extensive experience in the field. Only samples with adequate material for a final report to be issued were in-cluded in the analysis. 1465 unique patients were identi-fied during the 6 month period covered by the study (Figure 1). A manual review of reports eliminated 33 pa-tients without duodenal biopsies, leaving 1432 for final re-view. Gender ratio of this cohort was 34:66 M:F, with a

median age of 45 (IQR 24–61). Histologic findings as re-ported by the gastrointestinal pathologist who signed out the original specimen were classified into one of four categories; villous atrophy consistent with celiac disease (CD), intact villous architecture with increased intrae-pithelial lymphocytes (IVA-IEL) [20,21], normal duode-num, or other findings. Samples were not classified in a graded system (such as the Marsh score). Additionally, we examined reports to determine if biopsies were simultan-eously submitted from sites other than the duodenum, and what additional findings were present in those sites.

Serologic testing

An automated electronic medical record search was per-formed to identify any celiac serology results for the 1432 patients identified above. Serologic assays included in the search were tTG (IgA or IgG), dGDN (IgA or IgG) and EMA (IgA only). tTG IgA and IgG antibodies were measured using the respective QUANTA Lite h-tTG ELISA assays (INOVA Diagnostics, San Diego, CA), which utilize human RBC-derived tTG as the capture antigen. dGDN IgA and IgG antibodies were measured using QUANTA Lite Gliadin II ELISAs (INOVA Diagnostics,

Pathology reports identified from keyword search (n=1465)

No duodenal biopsy (n=33)

EMR search for concurrent serology results (n=1432)

Positive serology (n=76)

Chart review (n=85) Negative serology (n=466)

No serology performed (n=890)

Chart review (n=76)

Pathology review for abnormal histology (any location)

No abnormal findings (n=381)

San Diego, CA), which utilize purified gliadin peptides for capture. The EMA IgA assay was performed using an in-direct immunoflourescent assay (INOVA Diagnostics, San Diego, CA) with primate distal esophagus as the slide substrate. Total IgA results were also included in the rou-tine panel to identify patients with IgA deficiency. All tests were performed in-house at the Cleveland Clinic as part of routine clinical testing in accordance with manufac-turer’s recommendations. Patients with a non-negative re-sult for any of the four assays were classified as having positive serology in the analyses that follow. tTG, dGDN, and EMA antibodies were detected in 51%, 54%, and 28% of patients with positive serologic results, respectively.

Chart review

Clinical records were reviewed for the subset of 161 pa-tients with either positive serology or biopsy results. In the cases reviewed the following information was noted: previous history of celiac disease, consumption of a glu-ten free diet, timing of the gluglu-ten free diet (before or after biopsy/serology), response to gluten free diet, HLA testing results, and the final clinical diagnosis. Patients were considered to have a diagnosis of celiac disease based on positive biopsy or serologic results in the con-text of appropriate clinical findings (such as response to gluten-free diet or prior history of CD). Finally, endos-copy reports were reviewed in the patients where sero-logic testing was performed to identify the indication for endoscopy.

Results

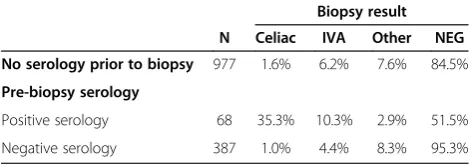

During the 6 month period of the study, 1432 duodenal biopsies were received where celiac disease was part of the differential specified in the pathology request. Less than one-third of these patients had evidence of celiac serology results in the medical record, and even in pa-tients with pre-biopsy testing the majority were sero-logically negative (Table 1). Celiac disease was noted as an indication for endoscopy in 11% of patients where serologic testing was performed (Table 2). Although only

5% (68/1432) of the study cohort had evidence of posi-tive serologic results prior to biopsy, the likelihood of findings consistent with CD was significantly higher in this group when compared to patients with negative serology or patients without serologic testing (Table 1, p < 0.001 for both comparisons, Fisher’s exact test). The overall inci-dence of histologic findings consistent with CD in the entire cohort was 3% (44/1432).

To understand why such a high proportion of these bi-opsies were sent in the absence of serologic findings, we looked for the presence of additional biopsy locations submitted concurrently with the duodenal biopsy. Virtu-ally all duodenal biopsies in this study (88%) were sub-mitted as part of a multi-site GI workup which included biopsies from at least one other location. The most com-mon combinations were stomach and duodenum (26%) and stomach, esophagus, and duodenum (24%). The pres-ence of a positive serology did seem to influpres-ence the deci-sion to limit biopsy to the duodenum, as patients with a positive celiac serology result had a slightly lower number of biopsy sites (average 2.5 vs 2.9 for negative serology) and were the most likely group to have only a single sample submitted (Figure 2). However, even in patients with positive serology, multiple biopsy sites were a com-mon occurrence.

Given that serologic status correlated well with the presence of celiac disease on biopsy, we examined the diagnostic yield of additional biopsy sites in these patients. We first evaluated the likelihood of significant findings in non-duodenal sites of patients with positive celiac ser-ology. 58% of patients with positive celiac serology had findings noted in at least one non-duodenal site (Table 3). Although the majority of these findings were non-specific inflammatory changes, significant celiac-related disease findings such as lymphocytic gastritis and colitis were noted in non-duodenal sites for three patients. These data Table 1 Serologic testing in patients sent for duodenal

biopsy

Biopsy result

N Celiac IVA Other NEG

No serology prior to biopsy 977 1.6% 6.2% 7.6% 84.5%

Pre-biopsy serology

Positive serology 68 35.3% 10.3% 2.9% 51.5%

Negative serology 387 1.0% 4.4% 8.3% 95.3%

N = total number of biopsies in each serologic category. Biopsy results refer only to findings from the duodenal biopsy. IVA = intact villous architecture with intra-epithelial lymphocytes. Findings consistent with celiac disease were significantly higher in patients with positive pre-biopsy serologic results when compared to either group (p < 0.001, Fisher’s exact test).

Table 2 Indication for endoscopy in patients where serologic testing was performed

Indication for endoscopy # Occurrences % Patients

Abdominal pain 260 52%

Diarrhea 99 20%

Reflux-type symptoms 91 18%

Nausea/vomiting 67 13%

Workup of celiac disease 53 11%

Weight loss 37 7%

Anemia 23 5%

GI bleeding 15 3%

Other 28 6%

are in line with previous publications which note an in-creased rate of such findings in CD patients [22,23]. Con-versely, in patients who had duodenal sections submitted despite having negative celiac serologic results only 14% had abnormal histology, with the most common findings being IVA-IEL and various presentations of non-specific duodenitis (Table 2). Villous atrophy was noted in four serology-negative cases, which included one case of col-lagenous sprue and two patients with known CD being evaluated for response to a gluten-free diet.

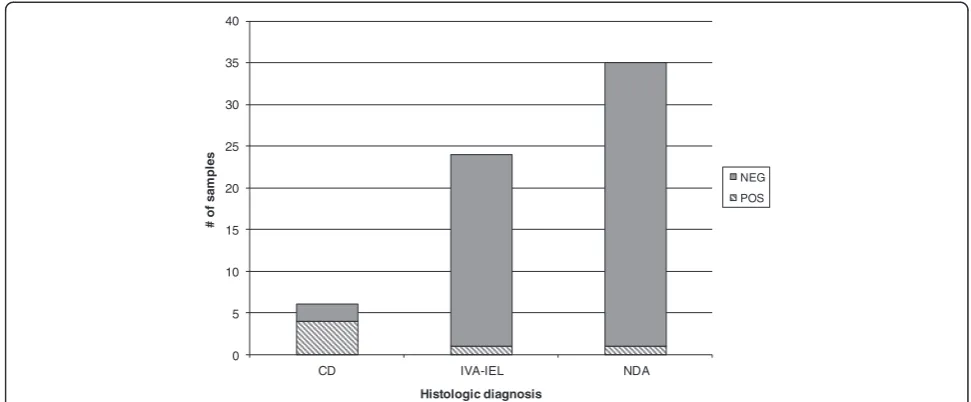

Finally, we identified a subset of 65 patients where ser-ology had been ordered after the biopsy was performed. The majority of these were patients with indeterminate

(IVA-IEL) or negative histologic findings. In these patients, positive post-biopsy serologic findings were almost en-tirely limited to patients who had characteristic celiac dis-ease findings on the biopsy (Figure 3).

Discussion

Evaluation for celiac disease is one of the most common reasons for duodenal biopsy. Positive findings in these biopsies are relatively uncommon, despite the widespread availability of screening assays for celiac-associated auto-antibodies. The data presented here suggests that this is because the vast majority of duodenal samples being sub-mitted for“rule out celiac”are not targeted biopsies driven

0% 5% 10% 15% 20% 25% 30% 35% 40% 45%

0 1 2 3 4

# of non-duodenal biopsy sites

% o

f s

a

mp

le

s No serology

Negative serology Positive serology

Figure 2Influence of serology results on number of biopsy sites.Non-duodenal biopsy sites included esophagus, stomach, ileum, and colon. Patients were grouped according to pre-biopsy serology results as described in methods. The frequency of duodenal-only biopsy was significantly higher in patients with positive serology than in other groups (p < 0.01, chi-squared).

Table 3 Non-celiac findings in patients with multiple biopsy sites

Non-duodenal findings in patients with positive pre-biopsy serology Duodenal findings in patients with negative pre-biopsy serology

Finding Site N % Finding N %

Chronic gastritis S 18 26% IVA - IEL 17 4%

Active esophagitis E 3 4% Focal active inflammation 15 4%

Lymphocytic gastritis S 2 3% Peptic injury 11 3%

Helicobacter pylori S 2 3% Celiac disease 4 1%

Other gastric S 2 3% Chronic duodenitis 3 1%

Reflux, EE E 2 3% Intramucosal granulomas 2 1%

Ilietis I 2 3% Ulcer 1 0.3%

Active colitis C 2 3% Mild increased lymphocytes 1 0.3%

Other colon C 2 3%

Lymphocytic colitis C 1 1%

Results were tabulated for 409 patients with pre-biopsy serologic results and multiple biopsy sites. S = stomach. E = esophagus. I = ileum. C = colon.“Other gastric”

by positive serologic results, but rather are part of a multi-site sampling strategy for a larger GI workup. In this type of clinical application, the diagnostic yield will necessarily be low. One limitation of the study is that because the analysis was based on EMR results, we cannot rule out the possibility that some patients were tested for celiac serology prior to referral to our system. However, these data suggest that when serologic results are available prior to biopsy, the information can be used to guide potential sampling strategies.

In patients with positive celiac serology results, non-duodenal findings were present in better than half of the patients. While many of these were non-specific changes such as chronic gastritis, significant findings such as lymphocytic gastritis and colitis were present in several patients. Because these entities are more common in pa-tients with celiac disease [23], the endoscopist may wish to procure additional biopsies from sites such as stom-ach and colon in patients who have a positive serologic result prior to biopsy. In contrast, the value of duodenal biopsy in patients with a negative pre-biopsy serology is less clear. Histologic findings consistent with celiac dis-ease were very uncommon in patients with negative se-rologies. One potential limitation of this study is that the frequency of duodenal bulb sampling was not noted, which could potentially lead to underdiagnosis of celiac disease in patients who were not adequately sampled. In the four patients where villous atrophy was observed despite a negative pre-biopsy serology, two were known CD patients, while a third patient had collagenous sprue, a variant of duodenal disease not associated with positive

serology [24]. The majority of duodenal findings in this cohort were non-specific duodenitis or IVA-IEL. Based on chart review, no patients with IVA-IEL and negative serology were ultimately determined to have celiac dis-ease. This suggests that in the setting of negative sero-logic studies, duodenal biopsies rarely provide clinically useful information that support the diagnosis of celiac disease.

Conclusion

The decision to pursue a duodenal biopsy on a patient involves both clinical and serological factors, and the presence of high risk symptoms such as anemia or diar-rhea is sufficient cause for biopsy in many published rec-ommendations for the workup of celiac disease [25]. In addition, some authors have advocated that duodenal bi-opsy should routinely be performed in patients undergo-ing endoscopy for GERD [26]. However, in lower-risk patients the use of pre-endoscopy serology has been ad-vocated as a tool that could optimize the decision to bi-opsy without reducing clinical sensitivity [27]. The data shown here support this contention, but suggest that this approach has not been widely adopted when decid-ing to pursue duodenal biopsy. In patients where sero-logic data is available, the results can help in the selection of GI locations to include in a multi-site biopsy strategy. The expanded use of serology to screen patients sent for endoscopy could potentially reduce the oper-ational expenses associated with processing and evaluat-ing large numbers of negative biopsies, resultevaluat-ing in more cost-effective treatment of these patients.

0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40

CD IVA-IEL NDA

# o

f sam

p

les

Histologic diagnosis

NEG

POS

Competing interest

The authors have no competing interest to disclose.

Authors’contributions

HW performed chart review and clinical classification of patient results, and drafted substantial portions of the primary manuscript. WH provided review of pathologic report findings and key suggestions on the analytical approach for the anatomic pathology portions of the manuscript. TD conceived of the study, participated in study design and primary data analysis of serologic results, and prepared the initial draft of the manuscript. All authors participated in revision and preparation of the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Support for EMR queries and manuscript preparation was provided from departmental resources of the Robert Tomsich Pathology and Laboratory Medicine Institute. No external funding was utilized for this study.

Received: 27 February 2013 Accepted: 4 November 2013 Published: 9 November 2013

References

1. Rewers M:Epidemiology of celiac disease: what are the prevalence, incidence, and progression of celiac disease?Gastroenterology2005, 128(4 Suppl 1):S47–51.

2. Riddle MS, Murray JA, Porter CK:The incidence and risk of celiac disease in a healthy US adult population.Am J Gastroenterol2012,107(8):55–1248. 3. Reilly NR, Green PH:Epidemiology and clinical presentations of celiac

disease.Semin Immunopathol2012,34(4):8–473.

4. Corrao G, Corazza GR, Bagnardi V, Brusco G, Ciacci C, Cottone M, Sategna Guidetti C, Usai P, Cesari P, Pelli MA,et al:Mortality in patients with coeliac disease and their relatives: a cohort study.Lancet2001,358(9279):356–361. 5. Peters U, Askling J, Gridley G, Ekbom A, Linet M:Causes of death in

patients with celiac disease in a population-based Swedish cohort. Arch Intern Med2003,163(13):1566–1572.

6. Hill ID, Dirks MH, Liptak GS, Colletti RB, Fasano A, Guandalini S, Hoffenberg EJ, Horvath K, Murray JA, Pivor M,et al:Guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of celiac disease in children: recommendations of the north american society for pediatric gastroenterology, hepatology and nutrition.J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr2005,40(1):1–19.

7. Institute AGA:AGA institute medical position statement on the diagnosis and management of celiac disease.Gastroenterology2006,131(6):1977–1980. 8. Parakkal D, Du H, Semer R, Ehrenpreis ED, Guandalini S:Do gastroenterologists

adhere to diagnostic and treatment guidelines for celiac disease?J Clin Gastroenterol2012,46(2):e12–20.

9. Evans KE, Sanders DS:What is the use of biopsy and antibodies in coeliac disease diagnosis?J Intern Med2011,269(6):572–581.

10. Katz KD, Rashtak S, Lahr BD, Melton LJ 3rd, Krause PK, Maggi K, Talley NJ, Murray JA:Screening for celiac disease in a North American population: sequential serology and gastrointestinal symptoms.Am J Gastroenterol 2011,106(7):1333–1339.

11. Tack GJ, Verbeek WH, Schreurs MW, Mulder CJ:The spectrum of celiac disease: epidemiology, clinical aspects and treatment.Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol2010,7(4):204–213.

12. Giersiepen K, Lelgemann M, Stuhldreher N, Ronfani L, Husby S, Koletzko S, Korponay-Szabo IR, Diagnosis EWGoCD:Accuracy of diagnostic antibody tests for coeliac disease in children: summary of an evidence report. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr2012,54(2):229–241.

13. Vermeersch P, Geboes K, Marien G, Hoffman I, Hiele M, Bossuyt X:Diagnostic performance of IgG anti-deamidated gliadin peptide antibody assays is comparable to IgA anti-tTG in celiac disease.Clin Chim Acta2010, 411(13–14):931–935.

14. Chow MA, Lebwohl B, Reilly NR, Green PH:Immunoglobulin A deficiency in celiac disease.J Clin Gastroentero2012,46(10):4–850.

15. Rostom A, Dube C, Cranney A, Saloojee N, Sy R, Garritty C, Sampson M, Zhang L, Yazdi F, Mamaladze V,et al:The diagnostic accuracy of serologic tests for celiac disease: a systematic review.Gastroenterology2005, 128(4 Suppl 1):S38–46.

16. van der Windt DA, Jellema P, Mulder CJ, Kneepkens CM, van der Horst HE: Diagnostic testing for celiac disease among patients with abdominal symptoms: a systematic review.JAMA2010,303(17):1738–1746.

17. Collin P, Kaukinen K, Vogelsang H, Korponay-Szabo I, Sommer R, Schreier E, Volta U, Granito A, Veronesi L, Mascart F,et al:Antiendomysial and antihuman recombinant tissue transglutaminase antibodies in the diagnosis of coeliac disease: a biopsy-proven European multicentre study.Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol2005,17(1):85–91.

18. Reeves GE, Squance ML, Duggan AE, Murugasu RR, Wilson RJ, Wong RC, Gibson RA, Steele RH, Pollock WK:Diagnostic accuracy of coeliac serological tests: a prospective study.Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol2006, 18(5):493–501.

19. Burgin-Wolff A, Mauro B, Faruk H:Intestinal biopsy is not always required to diagnose celiac disease: a retrospective analysis of combined antibody tests.BMC Gastroenterol2013,13:19.

20. Aziz I, Evans KE, Hopper AD, Smillie DM, Sanders DS:A prospective study into the aetiology of lymphocytic duodenosis.Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2010,32(11–12):1392–1397.

21. Brown I, Mino-Kenudson M, Deshpande V, Lauwers GY:Intraepithelial lym-phocytosis in architecturally preserved proximal small intestinal mucosa: an increasing diagnostic problem with a wide differential diagnosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med2006,130(7):1020–1025.

22. Brown IS, Smith J, Rosty C:Gastrointestinal pathology in celiac disease: a case series of 150 consecutive newly diagnosed patients.Am J Clin Pathol2012,138(1):42–49.

23. Chetty R, Govender D:Lymphocytic and collagenous colitis: an overview of so-called microscopic colitis.Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol2012, 9(4):209–218.

24. Xiao Z, Dasari VM, Kirby DF, Bronner M, Plesec TP, Lashner BA:Collagenous sprue: a case report and literature review.Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2009,5(6):418–424.

25. Goddard AF, McIntyre AS, Scott BB:Guidelines for the management of iron deficiency anaemia. British society of gastroenterology.Gut2000, 46(Suppl 3–4):IV1–IV5.

26. Lebwohl B, Bhagat G, Markoff S, Lewis SK, Smukalla S, Neugut AI, Green PH: Prior endoscopy in patients with newly diagnosed celiac disease: a missed opportunity?Dig Dis Sci2013,58(5):1293–1298.

27. Hopper AD, Cross SS, Hurlstone DP, McAlindon ME, Lobo AJ, Hadjivassiliou M, Sloan ME, Dixon S, Sanders DS:Pre-endoscopy serological testing for coeliac disease: evaluation of a clinical decision tool.BMJ2007, 334(7596):729.

doi:10.1186/1471-230X-13-156

Cite this article as:Wilandet al.:Limited utilization of serologic testing in patients undergoing duodenal biopsy for celiac disease.BMC Gastroenterology201313:156.

Submit your next manuscript to BioMed Central and take full advantage of:

• Convenient online submission

• Thorough peer review

• No space constraints or color figure charges

• Immediate publication on acceptance

• Inclusion in PubMed, CAS, Scopus and Google Scholar

• Research which is freely available for redistribution