Substance Use Problems and Associated Psychiatric Symptoms Among

Adolescents in Primary Care

Lydia A. Shrier, MD, MPH*¶; Sion K. Harris, PhD‡¶; Martha Kurland, LICSW§¶; and John R. Knight, MD*储¶

ABSTRACT. Objective. Substance use disorders (SUDs) are associated with other mental disorders in adolescence, but it is unclear whether less severe sub-stance use problems (SUPs) also increase risk. Because youths with SUPs are most likely to present first to their site of primary care, it is important to establish the pres-ence and patterns of psychiatric comorbidity among ad-olescent primary care patients with subdiagnostic use of alcohol or other drugs. The objective of this study was to determine the association between level of substance use and psychiatric symptoms among adolescents in a pri-mary care setting.

Methods. Patients who were aged 14 to 18 years and receiving routine care at a hospital-based adolescent clinic were eligible. Participants completed the Problem Oriented Screening Instrument for Teenagers Substance Use/Abuse scale, which is designed to detect social and legal problems associated with alcohol and other drugs, and the Adolescent Diagnostic Interview, which evalu-ates forDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Dis-orders, Fourth Editiondiagnoses of substance abuse/de-pendence and 8 types of psychiatric symptoms. We examined gender-specific associations of no/nonprob-lematic substance use (NSU), SUP, and SUD with psy-chiatric symptom presence (any symptoms within each type), score (symptom scores summed across all types), and number of types (number of different symptom types endorsed).

Results. Of 538 adolescents (68% female; mean ⴞ standard deviation age: 16.6ⴞ1.4 years), 66% were clas-sified with NSU, 18% with SUP, and 16% with SUD, and 80% reported having at least 1 type of psychiatric symp-tom in the previous 12 months. Sympsymp-toms of anxiety were most common (60% of both boys and girls), fol-lowed by symptoms of depression among girls (51%) and symptoms of attention-deficit disorder (ADD) among boys (47%). Compared with those with NSU, youths with SUP and those with SUD were more likely to report symptom presence for several types of psychiatric symp-toms. Girls with SUP or SUD had increased odds of reporting symptoms of mania, ADD, and conduct disor-der; girls with SUD were at increased risk for symptoms of depression, eating disorders, and hallucinations or delusions. Boys with SUP had increased odds of ADD symptoms, whereas boys with SUD had increased odds

of reporting hallucinations or delusions. Boys with SUP or SUD had increased odds of reporting symptoms of conduct disorder. Youths with SUP and SUD also had higher psychiatric symptom scores and reported a wider range of psychiatric symptom types (number of types) compared with youths with NSU.

Conclusions. Like those with SUD, adolescents with subdiagnostic SUP were at increased risk for experienc-ing a greater number of psychiatric symptoms and a wider range of psychiatric symptom types than youths with NSU. Specifically, adolescents with SUP are at in-creased risk for symptoms of mood (girls) and disruptive behavior disorders (girls and boys). These findings sug-gest the clinical importance of SUP and support the con-cept of a continuum between subthreshold and diagnos-tic substance use among adolescents in primary care. Identification of youths with SUP may allow for inter-vention before either the substance use or any associated psychiatric problems progress to more severe levels. Pe-diatrics 2003;111:e699 –e705. URL: http://www.pediatrics. org/cgi/content/full/111/6/e699; substance use, substance abuse, substance use disorder, psychiatric symptoms, co-morbidity, adolescent.

ABBREVIATIONS. SUD, substance use disorder; ADHD, atten-tion-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; SUP, substance use problem; DSM-PC,Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Primary Care; POSIT, Problem Oriented Screening Instrument for Teenagers; ADI, Ad-olescent Diagnostic Interview;DSM-IV,Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition; NSU, no/nonproblem-atic substance use; ADD, attention-deficit disorder.

S

ubstance use disorders (SUDs) in adolescents have been correlated with other psychiatric di-agnoses, including dysthymia and major de-pression, conduct disorder, attention-deficit/hyper-activity disorder (ADHD), eating disorders, and psychosis.1–13However, less is known about the psy-chiatric comorbidity for adolescents with less severe but more prevalent substance use problems (SUPs). In publishing theDiagnostic and Statistical Manual for Primary Care (DSM-PC) Child and Adolescent Ver-sion, the American Academy of Pediatrics has recog-nized the importance of subdiagnostic mental health problems in the primary care clinician’s office.14TheDSM-PC identifies “substance use problem” as a diagnostic category that is along the same develop-mental spectrum as yet distinct from SUD (ie, abuse or dependence). Common manifestations of SUP in adolescents include using a substance because of behavioral or emotional problems and having occa-sional impaired memory or motor dysfunction as a result of substance use.14

From the *Division of Adolescent/Young Adult Medicine, ‡Clinical Re-search Programs Office, §Department of Psychiatry,储Division of General Pediatrics, and ¶Center for Adolescent Substance Abuse Research, Chil-dren’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts. Received for publication Nov 5, 2002; accepted Feb 19, 2003.

Reprint requests to (L.A.S.) Division of Adolescent/Young Adult Medicine, Children’s Hospital, 300 Longwood Ave, Boston, MA 02115. E-mail: lydia.shrier@tch.harvard.edu

Researchers as well as clinicians have recognized that substance use exists along a continuum and that patterns of use below the diagnostic threshold for abuse/dependence may still be associated with sub-stantial morbidity.2 In 1 large community-based study of adolescents, increasing levels of alcohol use—from abstention to experimentation, social drinking, problem drinking, and abuse/depen-dence—were associated with increasing lifetime oc-currence ofDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition, Reviseddiagnoses of depres-sive disorders and disruptive behavior disorders, as well as problematic use of tobacco and other drugs.2 Because youths with SUPs are most likely to present first to their site of primary care, it is important to establish the presence and patterns of psychiatric comorbidity among adolescent clinic outpatients with subdiagnostic use of alcohol or other drugs.

Gender differences have been described in the ep-idemiology of substance use15and in psychiatric co-morbidity.16 Epidemiologic studies in adults have found that although substance use is more common in men than in women,17substance-abusing women experience higher rates of comorbidity.18 Boys and girls with problematic substance use (SUP or SUD) may also differ in psychiatric comorbidity, which has important implications for designing gender-appro-priate approaches to treatment. Some studies have found higher rates of depression among adolescent girls with SUD,11,19although others have reported no difference between the genders.2Conduct and other disruptive behavior disorders have been more prev-alent among adolescent boys with SUD in some stud-ies5but not others.2,19Previous studies have exam-ined gender differences for disorders that meet

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

criteria2and in adolescents in substance abuse treat-ment.5,20

The objective of this study was to examine the gender-specific associations between SUPs and SUDs and the quantity, quality, and variety of correlated psychiatric symptoms among patients of a general adolescent medicine practice. We hypothesized that SUPs, like SUDs, would be associated with signifi-cant psychiatric comorbidity and that gender differ-ences would exist in the patterns of substance use and psychiatric comorbidity.

METHODS Participants

The study protocol and data management procedures have been previously described in detail.21Patients who were 14 to 18

years of age and presented for routine care to an urban, hospital-based adolescent clinic between March 1999 and September 2000 were invited to participate in the study at the conclusion of the medical visit. Patients were excluded when their provider deter-mined that they were in a medical or emotional crisis at the time of the visit or when they were unable to read and understand English. Participants were offered a $25 merchandise certificate as compensation for their time. After a research assistant explained the study and answered any questions, each participant provided informed assent. The institutional review board of the hospital approved the study and waived parental consent in accordance with federal regulations22and the Society for Adolescent Medicine

guidelines for adolescent health research.23

Participants completed an assessment battery that included the

17-item Substance Use/Abuse Scale from the Problem Oriented Screening Instrument for Teenagers (POSIT)24and the structured

Adolescent Diagnostic Interview (ADI) for substance use.25,26The

self-administered (paper and pencil) POSIT Substance Use/Abuse Scale is designed to detect social and legal problems associated with alcohol and other drugs. The reliability and validity of the POSIT has been tested in several studies of adolescents, including high school students,27 youths in outpatient27,28 and inpatient

drug treatment,27arrested youths,29and youths attending a

gen-eral adolescent clinic.30 The POSIT Substance Use/Abuse Scale

differentiates heavy substance users from nonusers (ie, demon-strates good concurrent differential validity)27and correlates with

other measures of substance use.28The internal consistency

reli-ability of the Substance Use/Abuse Scale is generally very good to excellent, ranging from 0.77 to 0.93,27,30and the 1-week test-retest

reliability in 1 study of well adolescent clinic patients was 0.77.30

The POSIT Substance Use/Abuse Scale includes questions such as, “During the past month, have you driven a car while you were drunk or high?” and, “Do you miss out on activities because you spend too much money on drugs or alcohol?” A positive POSIT Substance Use/Abuse score is considered to be 1 or more “yes” answers (possible score range: 0 –17).

The ADI generatesDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) diagnoses of alcohol/drug abuse and dependence31and has demonstrated sound

psychomet-ric properties (interrater agreements, test-retest reliability, concur-rent validity, and criterion validity) in adolescents.26The ADI is

administered by a trained interviewer and takes 30 to 90 minutes to complete. The ADI was scored by a research assistant using the ADI manual instructions25and by computer with an SPSS syntax

algorithm developed by the author of the ADI. Two study inves-tigators who were blinded to the study hypotheses reviewed the data and resolved by consensus any discrepancies in scoring of the ADI or assignment of a diagnosis. For the purposes of this study, substance use was classified as no/nonproblematic substance use (NSU; no alcohol/drug use in previous 12 months, or some use in previous 12 months and POSIT score⫽0), SUP (POSIT scoreⱖ1 but no ADI diagnosis of substance abuse or dependence), and SUD (ADI diagnosis of either alcohol or drug abuse or depen-dence).

The ADI also evaluates 3 to 5 psychiatric symptoms in the previous 12 months from each of the following domains: depres-sion, mania, eating disorder, delusional thinking and hallucina-tions (combined for these analyses), attention-deficit disorder (ADD), anxiety, and conduct disorder. Psychiatric symptomatol-ogy was examined in 3 different ways. First, report of any symp-tom (psychiatric sympsymp-tom presence) within each of the sympsymp-tom types was noted. Second, a psychiatric symptom score was created to reflect the degree of psychiatric distress. The sum of reported symptoms within each symptom type was normalized (ie, con-verted to az score) for each gender, then the normalized sums were summed across all symptom types. Thus, a higher psychiat-ric symptom score represented more reported symptoms. The actual values of the psychiatric symptom scores are derived from normalized data and thus have no clinical relevance as numbers. Therefore, for avoiding confusion, the results of statistical com-parisons are reported but the scores themselves are not presented. Third, for quantifying the variety of different symptoms reported by an individual, a variable for the number of psychiatric tom types was created by summing the number of different symp-tom types for which at least 1 sympsymp-tom was reported.

Associations of category of substance use with psychiatric symptoms (presence, score, and number of types) were examined with 2and analysis of variance in SPSS. Multivariate logistic

interaction terms with the substance use variable.32The presence

of confounding by demographic variables was determined using the change inestimate method (ie, whether the estimate of the for the substance use variable and its standard error changed by at least 10% with inclusion of each demographic variable in the model).32

RESULTS Descriptive Analyses

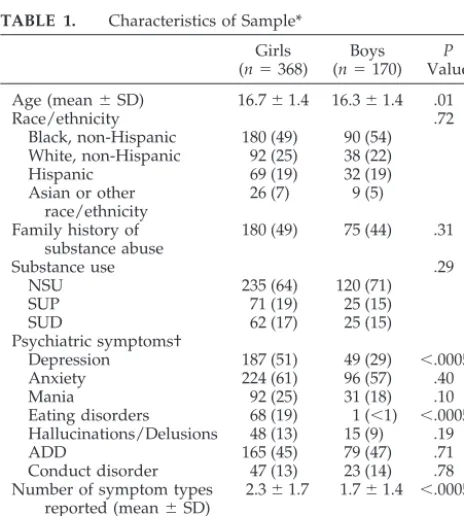

The 538 adolescents were 68% female and of di-verse race/ethnicity (Table 1). Girls in our sample were slightly older than were boys. Nearly one half of girls and boys reported a family history of sub-stance use. Two thirds (66%) of the participants were classified with NSU, 18% with SUPs, and 16% with SUDs; there were no differences by gender in sub-stance use classification.

Sixty percent of adolescents reported the presence of at least 1 type of psychiatric symptom in the past 12 months; girls were more likely than boys were to report any psychiatric symptoms. Anxiety symptoms were most commonly reported, followed by symp-toms of depression among girls and ADD among boys. Girls were more likely than boys were to report symptoms of depression and eating disorders. There were no differences between the genders in rates of reporting symptoms of mania, anxiety, delusions or hallucinations, ADD, or conduct disorder. Although girls and boys reported similar degrees of psychiatric distress (had similar psychiatric symptom scores), girls reported a greater number of psychiatric symp-tom types compared with boys.

Bivariate Analyses

Compared with girls with NSU, girls with SUDs were more likely to report experiencing symptoms of

depression and eating disorders. Girls with SUPs as well as those with SUDs were more likely to report symptoms of mania, ADD, and conduct disorder (Table 2). Compared with boys with NSU, boys with SUPs were more likely to report experiencing symp-toms of ADD. Increasing severity of substance use was associated with increasing likelihood of conduct disorder symptoms in boys. Boys with SUDs were much more likely than were boys with NSU to report hallucinations or delusions.

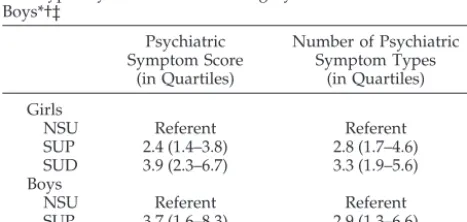

The psychiatric symptom score was higher for ad-olescents with SUPs and SUDs compared with those with NSU (Pⱕ .0005 for both boys and girls). Both boys and girls using substances reported greater number of psychiatric symptom types compared with those with NSU (mean number of symptom types reported: 2.7 SUPs and 3.0 SUDs vs 1.7 NSU;

Pⱕ.0005).

Multivariate Analyses

Table 3 displays the adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for adolescents with SUPs and those with SUDs reporting each type of psychiatric symptom, by gender. The models for girls controlled for age and family history of substance use, and the models for boys controlled for age. Girls with SUPs as well as girls with SUDs had increased odds of symptoms of mania, ADD, and conduct disorder. Girls with SUDs were at increased risk of symptoms of depression, eating disorders, and hallucinations or delusions. Boys with SUPs had increased odds of ADD symptoms, and boys with SUDs had increased odds of reporting hallucinations or delusions. Boys with either SUPs or SUDs had increased odds of symptoms of conduct disorder. Post hoc testing re-vealed that SUPs and SUDs did not significantly differ from each other in any of the models. None of the interaction terms between covariates and sub-stance use category was significant. There was no evidence of confounding by the covariates in any of the models.

Adjusting for family history of substance abuse, SUPs and SUDs were associated with higher psychi-atric symptom score and number of symptom types for both boys and girls (Table 4). For example, com-pared with those with NSU, adolescent girls with SUPs had 2.4 times the odds of being 1 quartile higher on psychiatric symptom score. SUPs and SUDs did not significantly differ from each other in any of the models. The interaction between family history of substance abuse and substance use cate-gory was not significant in any of the models. Family history of substance abuse did not seem to confound the observed associations.

DISCUSSION

This study showed that adolescents with SUPs, like those with SUDs, report a greater number and variety of symptoms of psychiatric distress com-pared with those with NSU. These findings support a continuity approach to substance use among ado-lescents in primary care and are consistent with stud-ies of subclinical substance use in other populations. In a community sample of high school students,

TABLE 1. Characteristics of Sample* Girls (n⫽368)

Boys (n⫽170)

P Value

Age (mean⫾SD) 16.7⫾1.4 16.3⫾1.4 .01

Race/ethnicity .72

Black, non-Hispanic 180 (49) 90 (54) White, non-Hispanic 92 (25) 38 (22) Hispanic 69 (19) 32 (19) Asian or other

race/ethnicity

26 (7) 9 (5)

Family history of substance abuse

180 (49) 75 (44) .31

Substance use .29

NSU 235 (64) 120 (71)

SUP 71 (19) 25 (15)

SUD 62 (17) 25 (15)

Psychiatric symptoms†

Depression 187 (51) 49 (29) ⬍.0005 Anxiety 224 (61) 96 (57) .40

Mania 92 (25) 31 (18) .10

Eating disorders 68 (19) 1 (⬍1) ⬍.0005 Hallucinations/Delusions 48 (13) 15 (9) .19

ADD 165 (45) 79 (47) .71

Conduct disorder 47 (13) 23 (14) .78 Number of symptom types

reported (mean⫾SD)

2.3⫾1.7 1.7⫾1.4 ⬍.0005

Reported⬎1 symptom type

234 (64) 87 (51) .008

Rohde et al2 similarly found that the likelihood of

DSM-IVpsychiatric disorder increased with increas-ing level of problematic alcohol use.

As theDSM-PC suggests, primary care clinicians care for youths with psychological issues that do not meet criteria for a disorder but still warrant a re-sponse.14 Identification of youths with SUPs may allow for intervention before either the substance use or any associated psychiatric problems progress to more severe levels. Indeed, primary care providers are increasingly placed on the front lines of diagnosis and management of mental disorders. A study con-ducted in an urban general medicine practice found

that clinically important substance use, anxiety, and depression were common and associated with sub-stantial functional impairment.33 Limited research has been done to identify the prevalence of psychi-atric problems among adolescents who attend sites of primary care,34but school- and community-based surveys suggest that the rates are high.35,36 Health maintenance visits provide an important opportu-nity to screen for substance use and other psychiatric problems.

Both boys and girls with problematic substance use (SUP or SUD) had increased odds of reporting symptoms of disruptive behavior disorders. The as-sociation of SUD with ADHD and conduct disorder has been well described.6 – 8,37,38One study of behav-iorally disordered, substance-using adolescents found that symptoms of ADHD were common in adolescents with conduct disorder and were posi-tively correlated with severity of substance depen-dence.7 Among incarcerated youths, the number of symptoms of conduct disorder was shown to in-crease with the level of substance abuse.8Research suggests that conduct disorder may account in part for the association between ADHD and SUD.6

According to problem behavior theory, adoles-cents who engage in problem behaviors such as sub-stance use may tend toward psychosocial unconven-tionality and thus may be more likely to experience alienation and impaired social functioning.39,40 Con-duct disorder and its associated delinquent behav-iors would also be a part of this deviant, norm-violating lifestyle. This theory is consistent with the developmental trajectory of antisocial behavior,

TABLE 2. Percentage of Girls and Boys Reporting Psychiatric Symptom Type, by Substance Use Category* Psychiatric symptom type Girls (n⫽368) Boys (n⫽170)

NSU SUP SUD PValue NSU SUP SUD PValue

Depression 44.3 57.7 67.7 .002* 25.0 32.0 44.0 .15

Anxiety 56.6 67.6 69.4 .08 53.8 60.0 68.0 .40

Mania 17.9 40.8 33.9 ⬍.0005*† 15.1 24.0 28.0 .23

Eating disorders 14.5 22.5 29.0 .02* — — — —‡

Hallucinations/delusions 11.1 12.9 21.0 .12 5.9 8.0 24.0 .02*

ADD 35.0 62.0 62.9 ⬍.0005*† 39.5 72.0 56.0 .008†

Conduct disorder 27.7 29.8 42.6 ⬍.0005*† 6.7 20.0 40.0 ⬍.0005*

* SUD significantly different from NSU by2test,P⬍.05.

† SUP significantly different from NSU by2test,P⬍.05.

‡ Analyses could not be performed because of small cell sizes.

TABLE 3. Adjusted Odds Ratios (95% CI) for Psychiatric Symptom Type by Substance Use Category in Adolescent Girls and Boys Psychiatric Symptom Type

Depression Mania Eating Disorders

Hallucinations/ Delusions

Attention Deficit Disorder

Conduct Disorder

Girls*

NSU Referent Referent Referent Referent Referent Referent

SUP 1.6 (0.9–2.7) 3.1 (1.7–5.6) 1.6 (0.8–3.1) 1.3 (0.6–3.0) 3.0 (1.7–5.4) 4.2 (1.8–9.8) SUD 2.4 (1.3–4.4) 2.3 (1.2–4.4) 2.2 (1.1–4.4) 2.4 (1.1–5.3) 3.2 (1.8–5.9) 8.3 (3.7–18.8) Boys†

NSU Referent Referent Referent

SUP 1.5 (0.3–7.6) 4.1 (1.6–10.7) 3.6 (1.0–12.0)

SUD 6.4 (1.8–23.6) 2.2 (0.9–5.5) 10.2 (3.2–32.2)

CI indicates confidence interval.

* Models adjusted for age and family history of substance use. † Models adjusted for age.

TABLE 4. Proportional Odds (95% CI) of Increasing Quartile for Psychiatric Symptom Score and Number of Psychiatric Symp-tom Types by Substance Use Category for Adolescent Girls and Boys*†‡

Psychiatric Symptom Score

(in Quartiles)

Number of Psychiatric Symptom Types

(in Quartiles)

Girls

NSU Referent Referent

SUP 2.4 (1.4–3.8) 2.8 (1.7–4.6) SUD 3.9 (2.3–6.7) 3.3 (1.9–5.6) Boys

NSU Referent Referent

SUP 3.7 (1.6–8.3) 2.9 (1.3–6.6) SUD 5.9 (2.5–14) 4.4 (1.3–6.6)

which includes substance use as a component of the pattern of conduct problems.8 Furthermore, im-paired social functioning may substantially worsen outcomes associated with psychiatric illness,41 in-cluding the development of SUDs.38,42

In our study, girls with SUDs reported internaliz-ing as well as externalizinternaliz-ing symptoms of emotional distress. This finding is consistent with a previous study of adolescents referred for substance abuse, in which girls engaged in externalizing behaviors as extensively as their male counterparts but were dis-tinguished by higher levels of internalizing symp-toms.16Other studies have found gender differences in the associations between psychiatric distress and substance use.7,43However, the predominance of de-pressive symptoms in substance-abusing girls has not always been seen. In 1 longitudinal study, de-pressive symptoms at 11 years of age was shown to predict substance use at 15 years of age for boys but not for girls.37In another study, depression and dis-ruptive behavior disorders were correlated with sub-stance use and abuse in both male and female ado-lescents.4Although anxiety symptoms were common in our study, we did not observe an association with substance use in girls, which has been previously reported.44,45

The gender differences in which and how psychi-atric symptoms are associated with substance use suggest that causative and/or vulnerability factors for the comorbidities may be different for boys and girls. For example, substance-using girls have more comorbidity and more family dysfunction than boys,16 suggesting that they have more severe psy-chological disturbance. Parents of depressed, sub-stance-using girls have reported that their daughters exhibited more psychosocial dysfunction, including more impaired relationships with their parents, than did parents of girls with depression alone, whereas no differences were seen in the reports by parents of depressed boys with and without substance use.46 Future research is needed to determine the temporal ordering of the development of psychosocial dys-function, SUPs, and other psychiatric morbidity in girls and boys.

There are several limitations to this study. The participants were primarily middle adolescents re-cruited from a single adolescent clinic in an urban children’s hospital and were largely nonwhite. Our findings may not be generalizable to younger chil-dren or young adults or to adolescents seen in other settings. Because this was a convenience sample, se-lection bias may be present. Older adolescents and those with serious SUPs or other psychiatric prob-lems may be less likely to seek routine health care,47 although youths with comorbid conditions may also be more likely to present for treatment of their symp-toms48(Berkson’s bias). Knowing the purpose of the study, clinic providers may have been more likely to refer patients with substantial substance use. Ado-lescent substance users may have been less likely to consent to participate in research, but there was no evidence of this sort of self-selection. Eighty percent of adolescents who were invited to participate con-sented to the study, and there were no differences

between those who refused and those who agreed to participate with regard to age; gender; race/ethnic-ity; or provider impressions of alcohol use, drug use, or any substance use.21 Patients in emotional crisis were excluded from this study, which would bias the results toward the null hypothesis. Nonetheless and not surprising, across all substance use groups, the rates of psychiatric symptoms reported by our sam-ple are substantially higher than the rates of psychi-atric diagnoses reported in previous research.2 The data were collected by self-report, which is subject to both recall and social desirability bias. As such, we would expect participants to minimize their sub-stance use, which would result in underestimation of the associations of interest. Finally, sample size pro-hibited the differentiation in the analyses between use of alcohol and use of other drugs.

It is important to note that causality cannot be inferred from this cross-sectional study. Individuals with psychiatric disorders may self-medicate their symptoms through the use of nonprescribed sub-stances.49,50Substance use may also worsen preexist-ing psychiatric symptoms51or precede the develop-ment of psychiatric disorder.10,52,53 Finally, there may be genetic or environmental factors that predis-pose to both psychiatric disorders and substance use.49,54,55Indeed, there are conflicting findings from longitudinal studies about the causal nature of the relationship between SUDs and other psychiatric dis-orders.4,13,37,56,57 Depending on the temporal and causal pathways, different treatments targeting the primary psychopathological process may be appro-priate for patients with comorbidity.

This study of adolescents in primary care adds to the growing literature supporting the clinical rele-vance of subclinical substance use and other psychi-atric problems. Whether SUP represents an earlier point on the continuum to SUD, serves as a marker for other psychological or social problems, or is as-sociated with medical or psychiatric morbidity in its own right, its identification warrants additional eval-uation and intervention. In particular, our findings suggest that primary care clinicians should screen adolescents with SUPs for the presence of a wide range of other psychiatric symptoms. Early interven-tion may prevent the development of more severe morbidity from substance use and correlated psychi-atric disorders among at-risk adolescents.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by grant R01 AA12165 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and grant 036126 from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Other support provided by grant 5 K23 MH01845 from the National Institute of Mental Health (to Dr Shrier) and grants 6T71MC 00009-10 (to Drs Shrier and Harris) and 5T20MC000-11-06 (to Dr Knight) from the Maternal and Child Health Bureau.

REFERENCES

1. Boyle MH, Offord DR. Psychiatric disorder and substance use in ado-lescence.Can J Psychiatry.1991;36:699 –705

2. Rohde P, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR. Psychiatric comorbidity with prob-lematic alcohol use in high school students.J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry.1996;35:101–109

3. Zeitlin H. Psychiatric comorbidity with substance misuse in children and teenagers.Drug Alcohol Depend.1999;55:225–234

4. Costello E, Erkanli A, Federman E, Angold A. Development of psychi-atric comorbidity with substance abuse in adolescents: effects of timing and sex.J Clin Child Psychol.1999;28:298 –311

5. Hovens J, Cantwell D, Kiriakos R. Psychiatric comorbidity in hospital-ized adolescent substance abusers.J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1994;33:476 – 483

6. Milberger S, Biederman J, Faraone S, Wilens T, Chu M. Associations between ADHD and psychoactive substance use disorders. Findings from a longitudinal study of high-risk siblings of ADHD children.Am J Addict.1997;6:318 –329

7. Whitmore EA, Mikulich SK, Thompson LL, Riggs PD, Aarons GA, Crowley TJ. Influences on adolescent substance dependence: conduct disorder, depression, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and gen-der.Drug Alcohol Depend.1997;47:87–97

8. Neighbors B, Kempton T, Forehand R. Co-occurrence of substance abuse with conduct, anxiety, and depression disorders in juvenile de-linquents.Addict Behav.1992;17:379 –386

9. Rao U, Ryan ND, Dahl RE, et al. Factors associated with the develop-ment of substance use disorder in depressed adolescents.J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry.1999;38:1109 –1117

10. Rao U, Daley SE, Hammen C. Relationship between depression and substance use disorders in adolescent women during the transition to adulthood.J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry.2000;39:215–222 11. Deykin EY, Buka SL, Zeena TH. Depressive illness among chemically

dependent adolescents.Am J Psychiatry.1992;149:1341–1347

12. Deykin EY, Levy JC, Wells V. Adolescent depression, alcohol and drug abuse.Am J Public Health.1987;77:178 –182

13. Biederman J, Wilens T, Mick E, et al. Is ADHD a risk factor for psycho-active substance use disorders? Findings from a four-year prospective follow-up study.J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry.1997;36:21–29 14. Wolraich M, Felice M, Drotar D, eds.The Classification of Children and

Adolescent Mental Diagnoses in Primary Care: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Primary Care (DSM-PC) Child and Adolescent Version. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 1996

15. Brady KT, Randall CL. Gender differences in substance use disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am.1999;22:241–252

16. Dakof G. Understanding gender differences in adolescent drug abuse: issues of comorbidity and family functioning. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2000;32:25–32

17. Grant B, Harford T, Dawson D, Chou P, Dufour M, Pickering R. Prev-alence of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence.Alcohol Health Res World.1994;18:243–248

18. Bucholz KK. Nosology and epidemiology of addictive disorders and their comorbidity.Psychiatr Clin North Am.1999;22:221–240

19. Bukstein OG, Glancy LJ, Kaminer Y. Patterns of affective comorbidity in a clinical population of dually diagnosed adolescent substance abusers. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry.1992;31:1041–1045

20. Clark DB, Pollock N, Bukstein OG, Mezzich AC, Bromberger JT, Don-ovan JE. Gender and comorbid psychopathology in adolescents with alcohol dependence. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36: 1195–1203

21. Knight JR, Sherritt L, Shrier LA, Harris SK, Chang G. Validity of the CRAFFT substance abuse screening test among adolescent clinic pa-tients.Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med.2002;156:607– 614

22. DHHS. Protection of Human Subjects (Title 45, Code of Federal Regu-lations, Part 46). US Department of Health and Human Services, Na-tional Institutes of Health, Office for Protection from Research Risks (on-line). Available at: grants.nih.gov/grants/oprr/humansubjects/ 45cfr46.htm. Accessed January 17, 2000

23. Anonymous. Guidelines for adolescent health research. Society for Ad-olescent Medicine.J Adolesc Health.1995;17:264 –269

24. Rahdert E.The Adolescent Assessment/Referral System Manual. Washing-ton, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administrations; 1991 (DHHS Publication No [ADM] 91-1735)

25. Winters K, Henly G.Adolescent Diagnostic Interview (ADI) Manual.Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services; 1993

26. Winters K, Stinchfield R, Fulkerson J, Henly G. Measuring alcohol and

cannabis use disorders in an adolescent clinical sample.Psychol Addict Behav.1993;7:185–196

27. Melchior L, Rahdert E, Huba G.Reliability and Validity Evidence for the Problem Oriented Screening Instruments for Teenagers (POSIT). Washing-ton, DC: American Public Health Association; 1994

28. McLaney M, Boca FD, Babor T. A validation study of the Problem Oriented Screening Instrument for Teenagers (POSIT).J Mental Health. 1994;3:363–376

29. Dembo R, Schmeidler J, Brodern P, Sue CC, Manning D. Examination of the reliability of the Problem Oriented Screening Instrument for Teen-agers (POSIT) among arrested youth entering a juvenile assessment center.Subst Use Misuse.1996;31:785– 824

30. Knight JR, Goodman E, Pulerwitz T, DuRant RH. Reliability of the Problem Oriented Screening Instrument for Teenagers (POSIT) in ado-lescent medical practice.J Adolesc Health.2001;29:125–130

31. American Psychiatric Association.Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994

32. Hosmer D, Lemeshow S.Applied Logistic Regression.New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 1989

33. Olfson M, Shea S, Feder A, et al. Prevalence of anxiety, depression, and substance use disorders in an urban general medicine practice.Arch Fam Med.2000;9:876 – 883

34. McQuaid JR, Stein MB, Laffaye C, McCahill ME. Depression in a pri-mary care clinic: the prevalence and impact of an unrecognized disor-der.J Affect Disord.1999;55:1–10

35. Grunbaum JA, Kann L, Kinchen SA, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance–United States, 2001.MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep.2002; 51(SS 4):1– 62

36. Lewinsohn PM, Hops H, Roberts RE, Seeley JR, Andrews JA. Adoles-cent psychopathology: I. Prevalence and incidence of depression and other DSM-III-R disorders in high school students.J Abnorm Psychol. 1993;102:133–144

37. Henry B, Feehan M, McGee R, Stanton W, Moffitt TE, Silva P. The importance of conduct problems and depressive symptoms in predict-ing adolescent substance use.J Abnorm Child Psychol.1993;21:469 – 480 38. Greene R, Biederman J, Faraone S, Sienna M, Garcia-Jetton J. Adolescent

outcome of boys with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and so-cial disability: results from a 4-year longitudinal follow-up study.J Consult Clin Psychol.1997;65:758 –767

39. Jessor R, Jessor S. Problem Behavior and Psychosocial Development: A Longitudinal Study of Youth.New York, NY: Academic; 1977

40. Jessor R. Risk behavior in adolescence: a psychosocial framework for understanding and action.J Adolesc Health.1991;12:597– 605

41. Greene R, Biederman J, Faraone S, Ouellette C, Penn C, Griffine S. Toward a new psychometric definition of social disability in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder.J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry.1996;35:571–578

42. Greene R, Biederman J, Faraone S, Wilens T, Mick E, Blier H. Further validation of social impairment as a predictor of substance use disorders: findings from a samples of siblings of boys with and without ADHD.J Clin Child Psychol.1999;28:349 –354

43. Coelho R, Rangel R, Ramos E, Martins A, Prata J, Barros H. Depression and the severity of substance abuse.Psychopathology.2000;33:103–109 44. Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR. Adolescent psychopathology: III.

The clinical consequences of comorbidity. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry.1995;34:510 –519

45. Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, Hibbard J, Rohde P, Sack WH. Cross-sectional and prospective relationships between physical morbidity and depression in older adolescents.J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35:1120 –1129

46. King CA, Ghaziuddin N, McGovern L, Brand E, Hill E, Naylor M. Predictors of comorbid alcohol and substance abuse in depressed ado-lescents.J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry.1996;35:743–751 47. Ford C, Bearman P, Moody J. Foregone health care among adolescents.

JAMA.1999;282:2227–2234

48. Bukstein O, Brent D, Kaminer Y. Comorbidity of substance abuse and other psychiatric disorders in adolescents.Am J Psychiatry.1989;146: 1131–1141

49. Mueser KT, Drake RE, Wallach MA. Dual diagnosis: a review of etio-logical theories.Addict Behav.1998;23:717–734

50. Khantzian E. The self-medication hypothesis of substance use disorders: a reconsideration and recent applications.Harv Rev Psychiatry.1997;4: 231–244

51. Treece C, Khantzian EJ. Psychodynamic factors in the development of drug dependence.Psychiatr Clin North Am.1986;9:399 – 412

Psychiatric diagnoses of treatment-seeking cocaine abusers.Arch Gen Psychiatry.1991;48:43–51

53. Castillo-Mezzich A, Tarter R, Giancola P, Lu S, Kirisci L, Parks S. Substance use and risky sexual behavior in female adolescents.Drug Alcohol Depend.1997;44:157–166

54. Kelder SH, Murray NG, Orpinas P, et al. Depression and substance use in minority middle-school students.Am J Public Health. 2001;91:761–766

55. Kendler KS, Neale MC, MacLean CJ, Heath AC, Eaves LJ, Kessler RC.

Smoking and major depression. A causal analysis.Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50:36 – 43

56. Dixit A, Crum R. Prospective study of depression and the risk of heavy alcohol use in women.Am J Psychiatry.2000;157:751–758

DOI: 10.1542/peds.111.6.e699

2003;111;e699

Pediatrics

Lydia A. Shrier, Sion K. Harris, Martha Kurland and John R. Knight

Adolescents in Primary Care

Substance Use Problems and Associated Psychiatric Symptoms Among

Services

Updated Information &

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/111/6/e699

including high resolution figures, can be found at:

References

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/111/6/e699#BIBL

This article cites 49 articles, 0 of which you can access for free at:

Subspecialty Collections

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/substance_abuse_sub

Substance Use

y_sub

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/psychiatry_psycholog

Psychiatry/Psychology

following collection(s):

This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

Permissions & Licensing

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml

in its entirety can be found online at:

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

Reprints

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml

DOI: 10.1542/peds.111.6.e699

2003;111;e699

Pediatrics

Lydia A. Shrier, Sion K. Harris, Martha Kurland and John R. Knight

Adolescents in Primary Care

Substance Use Problems and Associated Psychiatric Symptoms Among

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/111/6/e699

located on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 1073-0397.