Intention to Return for Papanicolaou Smears in Adolescent Girls

and Young Women

Jessica A. Kahn, MD, MPH*; Elizabeth Goodman, MD*; Gail B. Slap, MD*; Bin Huang, MS*; and S. Jean Emans, MD‡

ABSTRACT. Objective. Sexually active adolescent girls have high rates of abnormal cervical cytology. However, little is known about factors that influence intention to return for Papanicolaou screening or follow-up. The aim of this study was to determine whether a theory-based model that assessed knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors pre-dicted intention to return.

Methods. The study design consisted of a self-admin-istered, cross-sectional survey that assessed knowledge, beliefs, perceived control over follow-up, perceived risk, cues for Papanicolaou smears, impulsivity, risk behav-iors, and past compliance with Papanicolaou smear fol-low-up. Participants were recruited from a hospital-based adolescent clinic that provides primary and subspecialty care, and the study sample consisted of all sexually active girls and young women who were aged 12 to 24 years and had had previous Papanicolaou smears. The main outcome measure was intention to return for Papanicolaou smear screening or follow-up.

Results. The enrollment rate was 92% (N ⴝ 490), mean age was 18.2 years, 50% were black, and 22% were Hispanic. Eighty-two percent of participants intended to return. Variables that were independently associated with intention to return included positive beliefs about follow-up (odds ratio [OR]: 1.07; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.02–1.11), perception that important others believe that the participant should obtain a Papanicolaou smear (OR: 1.93; 95% CI: 1.38 –2.74), perceived control over turning (OR: 1.24; 95% CI: 1.06 –1.46), and having re-ceived cues to obtain a Papanicolaou smear (OR: 1.31; 95% CI: 1.08 –1.60).

Conclusions. Analysis of this novel theoretical frame-work demonstrated that knowledge and previous behav-iors were not associated with intention to return for Papanicolaou smear screening and follow-up in this pop-ulation of young women. However, modifiable attitudi-nal components, including persoattitudi-nal beliefs, perception of others’ beliefs, and cues to obtaining Papanicolaou smears, were associated with intention to return.

Pediatrics 2001;108:333–341; Papanicolaou smears, ado-lescent, intention to return.

ABBREVIATIONS. HPV, human papillomavirus; ASCUS, atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance; SIL, squamous in-traepithelial lesion.

G

enital human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is the most common sexually transmitted vi-ral infection in the United States, with a prev-alence of approximately 50% in young sexually ac-tive women.1,2 These young women are at risk forabnormal cervical cytology and cervical dysplasia,3– 6

which may progress to carcinoma in situ and inva-sive cervical cancer. National data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention indicate that of 31 569 women who were younger than 30 years and screened with Papanicolaou smears between 1991 and 1993, 8.0% had atypical squamous cells of unde-termined significance (ASCUS), 9.4% had low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (SIL), 2.1% had high-grade SIL, and ⬍0.1% had squamous cell cancer.7

Although HPV infection frequently is transient in adolescents and the natural history of cytologic ab-normalities in adolescents is still being elucidated,8

adolescents have a relatively high incidence of ab-normal cytology. A recent study demonstrated that the incidence of SIL was higher in adolescents 10 to 19 years of age than in adult women.9In addition, it

is likely that many adults with high-grade lesions were infected as adolescents. Postulated mechanisms for the high rates of abnormal cytology in young women include early initiation of sexual intercourse, high number of sexual partners, high incidence of sexually transmitted infections including HPV, high incidence of smoking, and susceptibility of the ado-lescent cervix to the acquisition of sexually transmit-ted infections and initiation of carcinogenesis.10 –14

The incidence and the mortality of cervical cancer have decreased dramatically during the past 30 years as a result of a comprehensive national effort to screen women for cervical dysplasia using Papanico-laou smears and improved treatment of carcinoma in situ and early-stage cervical cancer. The 5-year sur-vival rate of 96% for localized cancer drops to 66% if the cancer has spread regionally.15Compliance with

periodic Papanicolaou smear screening, evaluation of abnormal Papanicolaou smears, and treatment of precursor lesions correlate with decreased incidence and mortality of cervical cancer.16,17Despite this, the

estimated rate of noncompliance with follow-up ap-pointments for abnormal Papanicolaou smears ranges from 23% to 80%.14,18 –23Noncompliance has

been associated with younger age, lower educational level, unmarried status, Medicaid or no health insur-ance, better overall health, and lower grade cervical lesions.14,19,22

From the *Division of Adolescent Medicine, Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, Ohio; and ‡Division of Adolescent/Young Adult Med-icine, Children’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts.

Received for publication Sep 27, 2000; accepted Dec 21, 2000.

Address correspondence to Jessica A. Kahn, MD, MPH, Division of Ado-lescent Medicine, Children’s Hospital Medical Center, 3333 Burnet Ave, Cincinnati, OH 45229. E-mail: kahnj1@chmcc.org

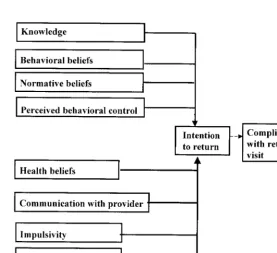

Despite the risk imposed by young age, little is known about the cognitive, attitudinal, and behav-ioral factors that differentiate adolescent and young adult women who do and do not comply with rec-ommendations for screening and follow-up. The fac-tors that predict adolescents’ preventive health be-haviors may differ from those of adults because of developmental and psychological processes that are specific to adolescence. Furthermore, although a large body of research supports the utility of specific behavioral theories in predicting health-related be-haviors,24 –27 complex behaviors (eg, adherence to

medical recommendations regarding Papanicolaou smear screening) often cannot be explained by one theory. We therefore developed a conceptual model that integrates several behavioral theories to explain both intention to return and actual return for Papa-nicolaou smear follow-up specifically in adolescent girls and young women (Fig 1).28 –35The significance

of developing such models is that behavioral theory-based interventions guided by these frameworks may be successful in increasing intention to return and actual return for Papanicolaou smear screening among adolescent girls and young women who are at risk for cervical dysplasia.

The model that was tested in this study incorporates 4 theories that have been useful in predicting cancer prevention behaviors: the Theory of Planned Behav-ior,36Health Belief Model,37Social Cognitive Theory,38

and the Transtheoretical Model and Stages of Change.39Each theory consists of a set of interrelated

concepts, also termed constructs, that specify the rela-tionships between specific variables to explain or pre-dict health-related behaviors.40 For example, the

The-ory of Planned Behavior proposes that attitudes about performing a behavior, perceived beliefs of others re-garding its performance, and perceived control over one’s ability to perform it all affect intention to perform

the behavior. Intention to perform the behavior, in turn, predicts actual behavior. A primary purpose of the Theory of Planned Behavior is to explain behavioral intention, and the success of the theory in explaining actual behavior is dependent on a number of factors, including the degree to which the behavior is under volitional control.40 In addition to the theories noted

above, the conceptual model incorporates 2 other con-structs hypothesized to predict follow-up intentions and behaviors: impulsivity and risk behaviors. The as-sociation between impulsivity and follow-up is sup-ported by focus group and individual interview find-ings reported previously.34 The association between

risk behaviors and follow-up is supported by the well-established clustering of behaviors that threaten health and well-being.41

This article summarizes the findings of the first phase of a longitudinal study designed to explore Papanicolaou smear follow-up by adolescent girls and young women. The overall goals of the study were to explore predictors of intention to return for Papanicolaou smear screening and follow-up, as well as the relationship between intention to return and actual return. Intention to return was chosen as the outcome measure in these analyses for the following reasons. First, behavioral intention is one of the most robust and consistent predictors of health-related be-haviors. A meta-analysis that examined the utility of the Theory of Planned Behavior in predicting health-related behaviors demonstrated that the model ex-plained 34% of the variance in behavior on average and that 66% of the explained variance in behavior was attributed to intention.24Furthermore, the

liter-ature on the utility of these specific behavioral theo-ries, particularly the Theory of Planned Behavior, in predicting adolescent behaviors is scarce. Little is known about the factors that have a direct impact on an adolescent’s plan to perform a behavior. Finally,

interventions to change behavior may be directed toward the immediate predictors of intention to per-form a behavior, as often occurs in clinical settings, as well as toward the pathway between intention and behavior. This article therefore examines in de-tail the associations between cognitive, attitudinal, and behavioral factors and intention to return for Papanicolaou smear follow-up. The constructs on the left in Fig 1 are hypothesized to influence compliance with a return visit indirectly, through intention to return. The pathways indicated by solid lines repre-sent the components of the model that were tested in this analysis. The specific hypotheses tested in this phase of the study are that the following variables are associated with intention to return: 1) knowledge about Papanicolaou smears and HPV, 2) positive personal beliefs and perceived beliefs of others about Papanicolaou smear follow-up, 3) high perceived control over follow-up, 4) health beliefs, including high perceived risk of abnormal Papanicolaou smears and cervical cancer and cues to obtaining a Papanicolaou smear, 5) communication with the pro-vider regarding Papanicolaou smears, 6) low impul-sivity, and 7) previous compliance with Papanico-laou smear follow-up.

METHODS Participants

The target population consisted of a consecutive sample of all 558 females who were aged 12 to 24 years and seen in an urban, hospital-based adolescent clinic between October 1998 and June 1999 and who had a history of sexual intercourse and previous Papanicolaou smear(s) done at the hospital. Patients who were unable to complete a written questionnaire independently (N⫽

24) were ineligible. Of the 534 eligible patients, 44 declined par-ticipation because of competing time commitments or lack of interest. The study sample therefore consisted of 490 participants (enrollment rate: 92%). All participants provided informed con-sent, and the protocol was approved by the hospital Committee on Clinical Investigation. The data presented were obtained from a survey instrument administered to all participants on enrollment in the study.

Clinic Procedures and Data Collection

Although all participants attended the adolescent clinic, an estimated 10% of the participants had had 1 or more previous Papanicolaou smears done in the adolescent gynecology clinic or teen-tot clinic. All clinics are located in the same hospital, all samples are sent to the same laboratory, and results are available on the same computerized cytology result information system. Procedures to inform clinic patients of abnormal results and stan-dards for screening and follow-up are as follows. Clinic patients

are asked to return once a year for screening Papanicolaou smears after they become sexually active or at approximately age 18. Since 1993, all patients with abnormal Papanicolaou smear reports on specimens collected in these 3 clinics have been informed of the abnormality by letter. Patients with a first Papanicolaou smear demonstrating ASCUS were instructed to have a repeat Papani-colaou smear in 4 months. Patients with a second PapaniPapani-colaou demonstrating ASCUS or any Papanicolaou demonstrating low-or high-grade SIL were instructed to make 2 appointments, 1 to discuss the result and another for colposcopy. Patients with high-grade SIL also received a telephone call from 1 of 2 nurses in the adolescent clinic. Patients who missed their colposcopy appoint-ments were sent a letter advising them to reschedule and were called by a nurse to help them reschedule. Patients who missed 2 colposcopy appointments were sent a registered letter and again called by a nurse.

The self-administered pencil-and-paper survey instrument was administered during the clinic visit and consisted of 116 items that assessed sociodemographic and health care characteristics as well as intention to return for follow-up, knowledge about Papanico-laou smears and HPV, attitudes about PapanicoPapanico-laou smear screen-ing and follow-up, impulsivity, and risk behaviors. Past compli-ance with Papanicolaou smear follow-up visits was determined with the use of computerized medical and laboratory reports. Sociodemographic characteristics, intention to return, and knowl-edge were assessed in part 1 of the survey. After part 1 was collected, participants completed part 2 of the survey, which as-sessed attitudes and beliefs about Papanicolaou smear screening and follow-up, impulsivity, and risk behaviors. Part 2 was pre-ceded by a paragraph that defined a Papanicolaou smear and gave routine recommendations for screening and follow-up. The pur-pose of the introductory paragraph was to ensure that participants would have baseline knowledge on which to base their responses to questions about attitudes and beliefs; it was included because preliminary interviews and pilot tests of the survey indicated that knowledge about Papanicolaou smears and HPV was poor.

Intention to return was assessed with the following question: “How sure or unsure are you that you will return for your next Pap smear?” Responses, on a 5-point Likert scale, were “you are very sure,” “you are somewhat sure,” “you are neither sure nor unsure,” “you are somewhat unsure,” and “you are very unsure.” Knowledge about Papanicolaou smears was measured with the use of 5 items with a possible score range of 0 (no correct items) to 5 (all correct items). Knowledge about HPV was measured with the use of a 6-item scale with a possible score range of 0 (the participant had never heard of HPV) to 6 (the patient had heard of HPV and answered all other items correctly). See Table 1 for psychometric characteristics of scales.

The items that assessed attitudes were divided into the follow-ing 5 domains: behavioral beliefs, normative beliefs, perceived behavioral control, health beliefs, and communication with the provider, all regarding Papanicolaou smears. Behavioral beliefs about Papanicolaou smear follow-up specific to this population were elicited through individual interviews and focus groups. Responses were measured with the use of a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree,” and re-sponses were summed to create a scale score. Normative beliefs are defined by Ajzen36as an individual’s perception of important

others’ beliefs about outcomes attributed to a behavior. Normative

TABLE 1. Psychometric Characteristics of Survey Scales

Survey Scale Number

of Items

Mean⫾

Standard Deviation

Range Intraclass Correlation Coefficient Between

Test and Retest*

Cronbach’s␣

(Standardized Item␣)

Knowledge about Papanicolaou smears

5 0.96⫾1.50 0–5 0.79 0.85

Knowledge about HPV 6 0.63⫾1.29 0–6 0.95 0.78

Behavioral beliefs 14 58.9⫾7.0 40–70 0.86 0.81

Normative beliefs 5 4.6⫾0.7 0–5 0.69 0.85

Perceived behavioral control 2 8.28⫾1.68 2–10 0.83 0.49

Communication with provider regarding Papanicolaou smears

7 9.72⫾4.34 7–35 0.77 0.91

Impulsivity 13 5.0⫾3.0 0–13 0.89 0.77

beliefs regarding the participant’s mother, friends, best friend, boyfriend, and doctor were elicited by asking, “How do you think the following people feel about your getting a Pap smear?” Re-sponses were on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “you defi-nitely should get a Pap smear” to “you defidefi-nitely should not get a Pap smear.” Responses were summed to create a scale score. Perceived behavioral control (one’s perceived ability to perform a behavior) was measured with the use of 2 items. Responses to, “How easy or difficult would it be for you to come in for your next Pap smear?” were measured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “extremely easy” to “extremely difficult.” Responses to, “I have total control over whether I come in for my next Pap smear,” were measured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree.” Responses to the 2 questions were summed for analysis.

Health beliefs measured included perceived risk and cues to action. Perceived benefits and barriers were included in the as-sessment of behavioral beliefs. Perceived susceptibility was mea-sured with the use of the following 3 items: “How likely is it that you would have an abnormal Pap smear?” “If you had a Pap smear which was abnormal but left untreated, how likely is it that it would become cancer?” and, “How likely is it that you will get cancer of the cervix sometime in your life?” Responses were on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “extremely likely” to “extremely unlikely.” Perceived severity was measured with the use of the following 3 items (responses to each item were in the form of 5-point Likert scales with the extremes indicated in parentheses): “How serious a health problem would an abnormal Pap smear be for you?” (“the most serious” to “not at all serious”), “If you get cervical cancer in the future, it’s not a big problem because it is easy to treat and to cure” (“strongly agree” to “strongly dis-agree”), and, “If you get cervical cancer in the future, how likely is it that you would die from it?” (“extremely likely” to “extremely unlikely”). Cues to action were measured with the use of 6 yes/no items that assessed whether the participant had heard that she should have a Papanicolaou smear from specific sources: a doctor or a nurse, her mother, a friend, the clinic, health/sexuality edu-cation classes at school, or the media/Internet. Cues were summed to create an index score.

Communication with the provider was assessed with the use of a 7-item scale, derived from individual interviews and focus groups conducted previously with the same clinic population34as

well as the work of Freed et al42and Ginsburg et al.43The scale

was designed to assess key elements of the 3 components of doctor–patient communication44: mutual exchange of information,

medical decision making, and creation of an interpersonal rela-tionship. Beliefs about communication with the provider were measured by asking the participant how likely it is on a 5-point Likert scale (ranging from “will definitely not happen” to “will definitely happen”) that the doctor will display a particular com-municative behavior, such as explaining the participant’s condi-tion to her. Scoring was performed by summing the results.

Behavioral variables included measures of impulsivity, risk behaviors and associated health outcomes linked to the develop-ment of abnormal Papanicolaou smears or cervical cancer (age of first sexual intercourse, number of lifetime sexual partners, con-traception use at last sexual intercourse, condom use at last sexual intercourse, smoking in the past 30 days, history of pregnancy, history of any sexually transmitted infection, and history of an abnormal Papanicolaou smear) and past compliance with Papani-colaou smear follow-up.

Impulsivity was assessed with the use of a scale derived from the work of Eysenck and Eysenck.45,46The subscale that we used

measured “narrow impulsiveness,” a construct specific for impul-sive traits. The wording of the original items was changed slightly to reflect American language (eg, “queue” was changed to “line”). Versions of this subscale have been tested and normed in both adults and adolescents.47The scale consisted of 13 yes/no items

and was scored by summing the responses that indicated higher impulsivity.

Past compliance with Papanicolaou screening and follow-up was assessed with the use of computerized medical and cytology records. Past compliance, which was derived from practices stan-dard in the clinic, was defined as having kept an appointment for 1) routine Papanicolaou smear within 15 months of the previous test, 2) follow-up Papanicolaou smear within 6 months of a smear that demonstrated ASCUS, 3) colposcopy within 2 months of a second smear that demonstrated ASCUS, and 4) colposcopy

within 2 months of a smear that demonstrated low- or high-grade SIL or carcinoma.

Statistical Methods

Intention to return and the knowledge scales were analyzed as dichotomous variables. For the item that assessed intention to return, responses of “very sure” or “somewhat sure” were cate-gorized as “intends to return.” Responses of “neither sure nor unsure,” “somewhat unsure,” and “very unsure” were catego-rized as “does not intend to return.” The item was dichotomized in this way because responses to this item were highly skewed (the great majority of respondents reported that they were sure that they would return) and for theoretical reasons: responses to Lik-ert-type questions frequently are dichotomized for analysis into neutral through negative responses and positive responses. Anal-yses also were performed with the use of the intention-to-return variable as a continuous variable and dichotomized as “very sure” versus all other responses, and results were similar in terms of significant findings. Scales that assessed knowledge about Papa-nicolaou smears and HPV also were dichotomized into 0 (none of the items was answered correctly) and greater than or equal to 1, because the scales were highly skewed and the majority of partic-ipants received a score of 0. Individual items that composed the scales that measured behavioral beliefs, normative beliefs, and perceived behavioral control were analyzed as ordinal variables. Individual health belief items that assessed risk were dichoto-mized to represent high versus low susceptibility and severity (eg, those who reported that they were “extremely likely” or “likely” to develop an abnormal Papanicolaou smear were categorized as “high susceptibility”). Summary scales that measured beliefs about Papanicolaou smear follow-up, normative beliefs, perceived behavioral control, communication with the provider, impulsivity, and cues to action were analyzed as continuous variables.

Associations between dichotomized or categorical variables and intention to return were determined with the use of2tests.

Associations between ordinal variables or non-normally distrib-uted continuous variables and intention to return were deter-mined with the use of Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. Associations between continuous scale scores and intention to return were analyzed with the use of Student’sttests if the scale scores were normally distributed and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests if the scale scores were not normally distributed. Variables that were associ-ated with intention to return at P ⬍ .05 were entered into a stepwise logistic regression procedure to identify variables that were independently associated with intention to return. Adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals are reported for the model, both unadjusted and adjusted for age, race, and insurance status.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics of the study sample are presented in Table 2. Approximately 50% of the par-ticipants were younger than 18 years, 50% were black, 22% were Hispanic, and 52% had Medicaid insurance. Twenty-seven percent had a history of at least 1 abnormal Papanicolaou smear, and 39% of those who were expected to return for follow-up had not complied with previous appointments for fol-low-up Papanicolaou smears or colposcopy. Eighty-two percent intended to return for Papanicolaou fol-low-up. Papanicolaou smear and HPV knowledge scores were low: 68% scored 0 on the Papanicolaou smear knowledge subscale, and 75% scored 0 on the HPV knowledge subscale.

scales and indices that measured attitudes and be-liefs about Papanicolaou smear follow-up were asso-ciated significantly with intention to return (data not shown but are available from the first author). Twelve of 14 behavioral beliefs about Papanicolaou smear follow-up were associated with intention to return. Behavioral beliefs that were positively asso-ciated with intention to return included the follow-ing: returning would enable her to find out that something is wrong that she cannot see, give her peace of mind, help her take control of her health, and help protect her health. Behavioral beliefs that were negatively associated with intention to return included the following: the procedure would be painful or embarrassing, she doesn’t want to look for trouble, she is afraid her parents might find out, she doesn’t have a consistent provider, her provider doesn’t communicate, she doesn’t have time, and she can’t get transportation. All normative beliefs (per-ceived beliefs of mother, friends, best friend, boy-friend, and doctor) and both items that assessed per-ceived control over returning (ease of returning and control over returning) were associated significantly with intention to return. Two of 6 health beliefs regarding risk (perceived susceptibility to the devel-opment of cervical cancer and perceived severity of

cervical cancer in terms of ease of cure), 4 of 6 cues to action (doctor, mother, letter or telephone call from clinic, and school health/sexuality classes), and all 7 beliefs about communication with the provider were associated significantly with intention to return.

All scales or indices (Table 4) that measured atti-tudes about Papanicolaou smear follow-up were as-sociated with intention to return, including behav-ioral beliefs about Papanicolaou smear follow-up, normative beliefs, perceived behavioral control, cues to action, and communication with the provider. In addition, 2 dichotomized attitudinal variables that assessed perceived susceptibility and perceived se-verity were associated with intention to return. Those who perceived themselves to be highly sus-ceptible to an abnormal Papanicolaou smear pro-gressing to cervical cancer were more likely to intend to return (85%) than those who did not (75%; P ⫽ .008). Those who perceived cervical cancer to be se-vere (unlikely to be able to be treated or cured) were more likely to intend to return (85%) than those who did not (77%;P ⫽.043). Impulsivity was associated negatively with intention to return (Table 4), and history of an abnormal Papanicolaou smear was as-sociated positively with intention to return (Table 5). However, risk behaviors, related health outcomes other than an abnormal Papanicolaou smear, and past compliance with Papanicolaou smear follow-up were not significantly associated with intention to return.

The independent variables that composed the final logistic regression model included beliefs about Pa-panicolaou smear follow-up, normative beliefs, per-ceived behavioral control, susceptibility to an ab-normal Papanicolaou smear progressing to cancer, TABLE 2. Baseline Characteristics of the Study Sample

Characteristic N(%)

Age

⬍18 y 233 (48.2)

ⱖ18 y 250 (51.8)

Race

White 116 (23.7)

Black 244 (49.9)

Other 129 (26.3)

Ethnicity

Non-Hispanic 378 (77.8)

Hispanic 108 (22.2)

Education

In school 396 (80.8)

Not in school 94 (19.2)

Health insurance

Private 151 (31.3)

Medicaid 248 (51.5)

None 35 (7.3)

Don’t know 48 (10.0)

History of abnormal Papanicolaou smear

No 360 (73.5)

Yes 130 (26.5)

Past compliance with Papanicolaou follow-up

Compliant 188 (38.4)

Noncompliant 120 (24.5)

Not applicable 182 (37.1)

Result of the highest grade of abnormal cytology

ASCUS 63 (13.2)

Low-grade SIL 44 (9.0)

High-grade SIL 16 (3.4)

SIL, difficult to grade 5 (1.0)

Intention to return for Papanicolaou follow-up

Very sure 361 (73.7)

Somewhat sure 40 (8.2)

Neither sure nor unsure 44 (9.0)

Somewhat unsure 16 (3.3)

Very unsure 29 (5.9)

TABLE 3. Associations Between Intention to Return for Papa-nicolaou Follow-up and Demographic Variables, Health Care Characteristics, and Knowledge

Variable Intention to Return

N(%) P

Value*

Demographic and health care characteristics

Age .001

⬍18 y 177 (76.0)

ⱖ18 y 219 (87.6)

Race .029

Nonwhite 298 (79.9)

White 103 (88.8)

Ethnicity NS

Hispanic 82 (75.9)

Non-Hispanic 315 (83.3)

Insurance .004

Medicaid 191 (77.0)

Private 135 (89.4)

None 31 (88.6)

Knowledge

Knowledge of Papanicolaou smears

NS

Score 0 255 (79.9)

Scoreⱖ1 133 (86.9)

Knowledge of HPV NS

Score 0 294 (80.1)

Scoreⱖ1 105 (86.8)

severity of cervical cancer in terms of effectiveness of treatment or cure, cues to action, communication with provider, impulsivity, and history of an abnor-mal Papanicolaou smear. Logistic regression analysis (Table 6) demonstrated that the variables that were independently associated with intention to return included scales that measured beliefs about Papani-colaou smear follow-up, normative beliefs, perceived behavioral control, and cues to action. Each increase of 1 point on the scale that measured beliefs about Papanicolaou smear follow-up was associated with a 7% increase in the odds that a participant would intend to return for follow-up. Each increase of 1 point on the scale of normative beliefs was associated with a 93% increase in the odds that a participant would intend to return. Each increase of 1 point on the scale of perceived control over returning was

associated with a 24% increase in the odds that a participant would intend to return. As an example, for individuals who differed by 1 point on the scale of perceived control over returning, the odds ratio was 1.24. For those who differed by 2 points on the scale, the odds ratio increased to 1.53. Each addi-tional cue to obtain a Papanicolaou smear increased by 31% the odds that a participant would intend to return. Controlling for age, race, and insurance status did not affect which variables were significantly as-sociated with intention to return.

DISCUSSION

This article describes the development and initial testing of a new conceptual model designed to explain cervical cancer screening and follow-up in adolescent TABLE 4. Associations Between Intention to Return for Papanicolaou Smear Follow-up and

Scales/Indices that Measure Attitudes and Impulsivity

Scale/Index Intends to Return (Mean⫾SD)

Does Not Intend to Return (Mean⫾SD)

P

Value*

Beliefs about Papanicolaou smear follow-up 59.8⫾6.7 54.9⫾7.2 ⬍.0001

Normative beliefs 4.7⫾0.58 4.1⫾1.0 ⬍.0001

Perceived behavioral control 8.5⫾1.6 7.4⫾1.8 ⬍.0001

Cues to action 3.1⫾1.4 2.3⫾1.5 ⬍.0001

Communication with provider 11.5⫾6.1 9.3⫾3.7 ⬍.0001

Impulsivity 4.9⫾3.0 5.8⫾2.9 .01

SD indicates standard deviation.

*Pvalue obtained fromttest comparing means for normally distributed scales and Wilcoxon rank sum test for non-normally distributed scales.

TABLE 5. Associations Between Intention to Return for Papanicolaou Follow-up and Risk Be-haviors, Related Outcomes, and Past Compliance with Papanicolaou Follow-up

Variable Intention to Return

N(%) PValue*

Risk behaviors/outcomes

Age of first sexual intercourse NS

ⱖ14 y 314 (82.6)

⬍14 y 87 (79.1)

Number of lifetime sexual partners NS

⬍5 299 (80.8)

ⱖ5 102 (85.0)

Contraception at last intercourse NS

Yes 333 (82.6)

No 68 (81.0)

Condom use at last intercourse NS

Yes 257 (81.3)

No 144 (84.2)

Smoked past 30 days NS

No 255 (81.0)

Yes 146 (83.4)

Previous pregnancy NS

No 271 (81.6)

Yes 128 (82.6)

History of a sexually transmitted disease NS

No 275 (80.4)

Yes 122 (84.7)

History of abnormal Papanicolaou smear

No 265 (78.6) .006

Yes 136 (88.9)

Past compliance

Compliance with previous Papanicolaou follow-up NS

Compliant 167 (88.8)

Noncompliant 103 (85.8)

girls and young women. A critical issue in the study of adolescent behaviors is whether theories of adult be-havior can help predict or explain adolescent bebe-havior. Our findings suggest that constructs tested primarily in adult populations also are useful in understanding ad-olescent intention to return for Papanicolaou smear follow-up. Although knowledge, risk behaviors, and past compliance with appointments for Papanicolaou smear screening and follow-up were not associated with intention to return as hypothesized, all attitudinal components of the model as well as lower impulsivity were associated with intention to return in univariate analyses. Positive beliefs about Papanicolaou smear fol-low-up, strong normative beliefs regarding folfol-low-up, high perceived behavioral control for follow-up, and cues to action for obtaining a Papanicolaou smear were associated independently with intention to return for Papanicolaou smear follow-up. These data therefore extend the findings of previous investigations that ex-amined the utility of specific behavioral theories28 –32,48

in predicting cervical cancer screening intentions and behaviors in adult women. First, the findings demon-strate that a conceptual model composed of several behavioral theories predicts intention to return for Pa-panicolaou smear follow-up; second, they suggest that constructs derived from these behavioral theories are generalizable to an adolescent population.

Central implications of these findings are that inter-ventions guided by behavioral theories may promote intended or actual return for Papanicolaou smear fol-low-up by adolescent girls and young women who are at risk for cervical dysplasia. Our findings suggest that patient attitudes about screening and follow-up, rather than knowledge or past behavior, are associated with intention to return. Although attitudes may be more difficult to change than knowledge, theoretically they are modifiable. Components of interventions designed to increase intention to return for Papanicolaou smear follow-up might include enhancing positive attitudes about follow-up, such as protecting one’s health or discovering an asymptomatic problem, emphasizing that providers and parents believe that Papanicolaou screening and follow-up is important, increasing young women’s sense of control over returning, and instituting clinic reminders or providing information on Papanicolaou smear screening and follow-up in school health and sexuality classes. Strategies to edu-cate providers about appropriate recommendations for screening and follow-up and provide guidance as to how they might improve their communication with young women also may be valuable. Effective

interven-tions may need to use multiple but consistent messages delivered in a variety of ways to target the model components identified in this study as important for intention to return for Papanicolaou smear screening and follow-up.

An important consideration in the utilization of these findings for interventions is that the theoretical constructs that predicted intention to return may not explain actual return in a subset of adolescents49;

some adolescents do not keep appointments despite positive intentions.50 Although⬎80% of the

partici-pants in our study intended to return, actual return rates are likely to be substantially lower23; thus,

so-ciodemographic or attitudinal factors may mediate or moderate the pathway between intention to return and actual return. Sheeran and Orbell48,49 have

be-gun to examine the relationship between intention and behavior and to propose interventions that may enhance compliance in women with high intentions to return for Papanicolaou smear screening. In addi-tion, the pathways may change in a full model in-cluding data on actual return. Whether adolescent attitudes have an impact on actual return indirectly, through intention, or directly will have implications for interventions. Future studies therefore are needed to address the following questions, to design evidence-based, effective interventions to enhance follow-up. To what extent does intention to return predict actual return in adolescent girls and young women, and what factors influence the pathway be-tween intention and behavior? Do interventions de-signed to change attitudes enhance intention to re-turn and actual rere-turn rates? In adult populations, interventions aimed at changing the attitudinal pre-dictors of intention to return (involving reminder letters, telephone counseling, educational programs, educational brochures, transportation incentives, and tracking systems) have enhanced actual compli-ance for screening and follow-up Papanicolaou smears, but the effectiveness of these interventions in adolescents remains to be tested.51–56

There are several limitations to this study. First, the model was tested in an urban, hospital-based sample with a relatively high proportion of black and Hispanic young women and may perform differently in other settings and populations. Second, it was necessary to create several new measures for this survey because there were no available instruments specific to knowledge and attitudes about Papanico-laou smears in adolescents. Third, the scales that measured knowledge, susceptibility, and severity TABLE 6. Logistic Regression Analyses: Independent Predictors of Intention to Return

Predictor Variable Unadjusted Adjusted for Age, Race,

Insurance Status

Odds Ratio

95% Confidence

Interval

Odds Ratio

95% Confidence

Interval

Beliefs about Papanicolaou smear follow-up

1.07 1.02–1.11 1.06 1.01–1.10

Normative beliefs 1.93 1.38–2.74 1.89 1.34–2.70

Perceived behavioral control 1.24 1.06–1.46 1.23 1.06–1.44

were skewed and therefore were dichotomized for analysis, which may have limited our ability to de-tect significant associations between the variables and intention to return. Finally, previous compliance with Papanicolaou smear follow-up recommenda-tions did not predict intention to return in the future. There are a number of potential explanations for this finding, including the possibility that participants answered the item that assessed intention to return in what they perceived to be a socially desirable way. It also may reflect an increasing sense of responsibil-ity for one’s health that these participants are acquir-ing as they become older.

Despite these limitations, our data provide a start-ing point for future theoretically grounded observa-tional and intervenobserva-tional studies of young women’s intentions and behaviors regarding Papanicolaou smear screening and follow-up visits. Ensuring com-pliance with cervical cancer prevention recommen-dations in young women is a complex issue and ultimately is likely to require comprehensive inter-ventions that not only focus on changing adolescent attitudes and intentions but also involve education of health care providers and the support of public health agencies.57

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the Deborah Munroe Noonan Memorial Fund and by Project Nos. 6 T71 MC 00009-09 and 5 T71 MC 00001-24 from the Maternal Child Health Bureau, Health Resources and Services Administration, US Department of Health and Human Resources.

We thank Victoria Chiou, BA, and Rebekah Kaplowitz, MD, for their assistance with data collection and interpretation; Lawren Daltroy, PhD, and Karen Emmons, PhD, for their thoughtful con-tributions to survey development and analysis; and Jonathan Ellen, MD, MPH, and Lorraine Freed, MD, MPH, for their major contribution to the development of the communication scale.

REFERENCES

1. Koutsky LA, Galloway DA, Holmes KK. Epidemiology of genital hu-man papillomavirus infection.Epidemiol Rev. 1988;10:122–163 2. Ho GY, Bierman R, Beardsley L, Chang CJ, Burk RD. Natural history of

cervicovaginal Papillomavirus infection in young women.N Engl J Med. 1998;338:423– 428

3. Koutsky L, Holmes K, Critchlow C. A cohort study of the risk of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or 3 in relation to papillomavirus infection.N Engl J Med. 1992;327:1272–1278

4. Lungu O, Sun XW, Felix J, Richart RM, Silverstein S, Wright TC. Relationship of human Papillomavirus type to grade of cervical intra-epithelial neoplasia.JAMA. 1992;267:2493–2496

5. Ho GY, Burk RD, Kelin S, et al. Persistent genital human papillomavirus infection as a risk factor for persistent cervical dysplasia.J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87:1365–1371

6. Wallin K, Wiklund FTA, Bergman F, et al. Type-specific persistence of human papillomavirus DNA before the development of invasive cervi-cal cancer.N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1633–1638

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Results from the national breast and cervical cancer early detection program, October 1, 1991–September 30, 1993. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1994;43: 530 –534

8. Moscicki AB, Shiboski S, Broering J, et al. The natural history of human papillomavirus infection as measured by repeated DNA testing in adolescent and young women.J Pediatr. 1998;132:277–284

9. Mount SL, Papillo JL. A study of 10,296 pediatric and adolescent Papa-nicolaou smear diagnoses in northern New England.Pediatrics. 1999; 103:539 –545

10. Roye CF. Abnormal cervical cytology in adolescents: a literature review.

J Adolesc Health. 1992;13:643– 650

11. Moscicki AB, Winkler B, Irwin C, Schachter J. Differences in biologic maturation, sexual behavior, and sexually transmitted disease between

adolescents with and without cervical intraepithelial neoplasia.J Pedi-atr. 1989;115:487– 493

12. Edebiri A. Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: the role of age at first coitus in its etiology.J Reprod Med. 1990;35:246 –259

13. Shew ML, Fortenberry JD, Miles P, Amortegui AJ. Interval between menarche and first sexual intercourse, related to risk of human papil-lomavirus infection.J Pediatr. 1994;125:661– 666

14. Michielutte R, Disekar RA, Young LD, May WJ. Noncompliance in screening follow-up among family planning clinic patients with cervical dysplasia.Prev Med. 1985;14:248 –258

15. American Cancer Society.Cancer Facts and Figures.Atlanta, GA: Amer-ican Cancer Society; 1998

16. IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of the Cervical Cancer Screen-ing Program. ScreenScreen-ing for squamous cervical cancer: duration of low risk after negative results on cervical cytology and its implications for screening policies.BMJ. 1986;293:659 – 664

17. Van der Graaf Y, Vooijs GP, Zeilhuis GA. Cervical screening revisited.

Acta Cytol. 1990;34:366 –372

18. Lane DS. Compliance with referrals from a cancer-screening project.J Fam Pract. 1983;17:811– 817

19. Eger RR, Peipert JF. Risk factors for noncompliance in a colposcopy clinic.J Reprod Med. 1996;41:671– 674

20. Cartwright PS, Reed G. No-show behavior in a county hospital colpos-copy clinic.Am J Gynecol Health. 1990;4:181

21. Frisch LE. Effectiveness of a case management protocol in improving follow-up and referral of Papanicolaou smears indicating cervical in-traepithelial neoplasia.J Am Coll Health. 1986;35:112–115

22. Laedtke TW, Dignan M. Compliance with therapy for cervical dysplasia among women of low socioeconomic status.South Med J. 1992;85:5– 8 23. Lavin C, Goodman E, Perlman S, Kelly LS, Emans SJ. Follow-up of

abnormal Papanicolaou smears in a hospital-based adolescent clinic.

J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 1997;10:141–145

24. Godin G, Kok G. The theory of planned behavior: a review of its applica-tions to health-related behaviors.Am J Health Promot. 1996;11:87–98 25. Janz NK, Becker MH. The health belief model: a decade later.Health

Educ Q. 1984;11:1– 47

26. Strecher VJ, DeVellis BM, Becker MH, Rosenstock IM. The role of self-efficacy in achieving health behavior change.Health Educ Q. 1986; 13:73–91

27. Prochaska JO, Redding C, Evers K. The transtheoretical model and stages of change. In: Glanz K, Lewis F, Rimer BK, eds.Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research and Practice. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1997:60 – 84

28. Hill D, Gardner G, Rassaby J. Factors predisposing women to take precautions against breast and cervix cancer.J Appl Soc Psychol. 1985; 15:59 –79

29. Hennig P, Knowles A. Factors influencing women over 40 years to take precautions against cervical cancer. J Appl Soc Psychol. 1990;20: 1612–1621

30. Funke BL, Nicholson ME. Factors affecting patient compliance among women with abnormal Pap smears.Patient Educ Counsel. 1993;20:5–15 31. Burak LJ, Meyer M. Using the Health Belief Model to examine and

predict college women’s cervical cancer screening beliefs and behavior.

Health Care Women Int. 1997;18:251–262

32. Murray MCM. Health beliefs, locus of control, emotional control and women’s cancer screening behaviour.Br J Clin Psychol. 1993;32:87–100 33. Curry SJ, Emmons KM. Theoretical models for predicting and improv-ing compliance with breast cancer screenimprov-ing.Ann Behav Med. 1994;16: 302–316

34. Kahn JA, Chiou V, Allen J, et al. Beliefs about Papanicolaou smears and compliance with Papanicolaou smear follow-up in adolescents: a qual-itative analysis.Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:1046 –1054 35. Gritz ER, Bastani R. Cancer prevention— behavior changes: the short

and the long of it.Prev Med. 1993;22:676 – 688

36. Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Org Behav Hum Decision Processes. 1991;50:179 –211

37. Becker MH, Maiman LA. Strategies for enhancing patient compliance.

J Commun Health. 1980;6:113–135

38. Bandura A.Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory.Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1986

39. Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Transtheoretical therapy: toward a more integrative model of change. Psychother Theory Res Pract. 1982;19: 161–173

40. Glanz K, Lewis FM, Rimer BK.Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice, 2nd Ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1997 41. Jessor R. Risk behavior in adolescence: a psychosocial framework for

understanding and action.J Adolesc Health. 1992;21:597– 605

adoles-cents’ satisfaction with health care providers and intentions to keep follow-up appointments.J Adolesc Health. 1998;22:475– 479

43. Ginsburg KR, Slap GB, Cnaan A, Forke CM, Balsley CM, Rouselle DM. Adolescents’ perceptions of factors affecting their decisions to seek health care.JAMA. 1995;273:1913–1918

44. Ong LML, De Haes JCJM, Hoos AM, Lammes FB. Doctor-patient communication: a review of the literature.Soc Sci Med. 1995;40:903–918 45. Eysenck SBG, Eysenck HJ. The place of impulsiveness in a dimensional system of personality description.Br J Soc Clin Psychol. 1977;16:57– 68 46. Eysenck SBG, Eysenck HJ. Impulsiveness and venturesomeness: their

position in a dimensional system of personality description.Psychol Rep. 1978;43:1247–1255

47. Eysenck SBG, Easting G, Pearson PR. Age norms for impulsiveness, ven-turesomeness and empathy in children.Person Individ Diff. 1984;5:315–321 48. Sheeran P, Orbell S. Using implementation intentions to increase

atten-dance for cervical cancer screening.Health Psychol. 2000;19:283–289 49. Orbell S, Sheeran P. “Inclined abstainers”: a problem for predicting

health behaviour.Br J Soc Psychol. 1998;37:151–165

50. Irwin CE, Millstein SG, Ellen JM. Appointment-keeping behavior in adolescents: factors associated with follow-up appointment-keeping.

Pediatrics. 1993;92:20 –23

51. Paskett ED, Carter WB, Chu J, White E. Compliance behavior in women with abnormal Pap smears. Developing and testing a decision model.

Med Care. 1990;28:643– 656

52. Lerman C, Hanjani P, Caputo C, et al. Telephone counseling improves adherence to colposcopy among lower-income minority women.J Clin Oncol. 1992;10:330 –333

53. Marcus AC, Crane LA, Kaplan CP, et al. Improving adherence to screening follow-up among women with abnormal pap smears: results from a large clinic-based trial of three intervention strategies.Med Care. 1992;30:216 –230

54. Bowman J, Sanson-Fisher R, Boyle C, Pope S, Redman S. A randomised controlled trial of strategies to prompt attendance for a Pap smear.J Med Screen. 1995;2:211–218

55. Mitchell H, Medley G. Adherence to recommendations for early repeat cervical smear tests.BMJ. 1989;298:1605–1607

56. Stewart DE, Buchegger PM, Lickrish GM, Sierra S. The effect of educa-tional brochures on follow-up compliance in women with abnormal Papanicolaou smears.Obstet Gynecol. 1994;83:583–585

57. Igra V, Millstein SG. Current status and approaches to improving preventive services for adolescents.JAMA. 1993;269:1408 –1412

THE 20TH CENTURY

. . . Real consumer spending rose in 70 of the 84 years between 1900 and 1984. In 1990 an hour’s work earned 6 times as much as in 1900. Most Americans walked to work at the start of the century, but by 1990 very few did and nearly 90% of families had a car. By 1987 most households had a fridge and a radio, nearly all had a TV, and about three-quarters had a washing machine. Per capita spending on food rose more than 75% between 1900 and 1990, with a marked increase in meat consumption.

Twitchell JB.Lead Us Into Temptation.New York, NY: Columbia University Press; 1999

DOI: 10.1542/peds.108.2.333

2001;108;333

Pediatrics

Jessica A. Kahn, Elizabeth Goodman, Gail B. Slap, Bin Huang and S. Jean Emans

Women

Intention to Return for Papanicolaou Smears in Adolescent Girls and Young

Services

Updated Information &

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/108/2/333

including high resolution figures, can be found at:

References

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/108/2/333#BIBL

This article cites 53 articles, 4 of which you can access for free at:

Subspecialty Collections

icine_sub

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/adolescent_health:med Adolescent Health/Medicine

following collection(s):

This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

Permissions & Licensing

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml

in its entirety can be found online at:

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

Reprints

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml

DOI: 10.1542/peds.108.2.333

2001;108;333

Pediatrics

Jessica A. Kahn, Elizabeth Goodman, Gail B. Slap, Bin Huang and S. Jean Emans

Women

Intention to Return for Papanicolaou Smears in Adolescent Girls and Young

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/108/2/333

located on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 1073-0397.