ARTICLE

Age of Alcohol-Dependence Onset: Associations With

Severity of Dependence and Seeking Treatment

Ralph W. Hingson, ScD, MPH, Timothy Heeren, PhD, Michael R. Winter, MPH

Youth Alcohol Prevention Center, Boston University School of Public Health, Boston, Massachusetts

The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVE.We explored whether people who become alcohol dependent at younger ages are more likely to seek alcohol-related help or treatment or experience chronic relapsing dependence.

METHODS.In 2001–2002 the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism completed a face-to-face interview survey with a multistage probability sample of

43 093 adults agedⱖ18, with a response rate of 81%. We focused on 4778 persons

diagnosable as alcohol dependent ever in their lives usingDiagnositic and Statistical

Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition criteria. Logistic regression examined whether respondents ever sought alcohol-related help or treatment, controlling for respondent demographics, number of dependence symptoms experienced, smoking and illicit drug use, childhood antisocial personality and depression, family history of alcoholism, and age of drinking onset.

RESULTS.Of persons ever alcohol dependent, 15% were diagnosable before age 18, 47% before age 21, and two thirds before age 25. Twenty-eight percent reported

ⱖ2 dependence episodes, 45% experienced an episode exceeding 1 year, and 34%

reported 6 or 7 dependence criteria. Relative to those first alcohol dependent at

ⱖ30 years, 21% of those ever dependent, the odds of ever seeking help were lower

among those first dependent before ages 18, 20, and 25. Yet, persons first

depen-dent atⱕ25 years had significantly greater odds of experiencing multiple

depen-dence episodes, episodes exceeding 1 year, and more dependepen-dence symptoms. Analyses indicated that the previously reported increased odds that persons who start to drink at an early age develop features of chronic relapsing dependence may have resulted from early drinkers being more likely to develop alcohol dependence at younger ages. This, in turn, increased their odds of experiencing multiple and longer episodes of alcohol dependence with more symptoms.

CONCLUSIONS.Adolescents need to be screened and counseled about alcohol, and treatment services should be reinforced by programs and policies to delay age of first alcohol dependence.

www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/ peds.2006-0223

doi:10.1542/peds.2006-0223

Key Words

alcohol dependence, duration, severity, drinking onset age

Abbreviations

NESARC—National Epidemiologic Study of Alcohol Related Conditions

DSM-IV—Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition NIAAA—National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism

OR— odds ratio CI— confidence interval

Accepted for publication Apr 6, 2006 Address correspondence to Ralph W. Hingson, ScD, MPH, Youth Alcohol Prevention Center, Boston University School of Public Health, 715 Albany St, Boston, MA 02118. E-mail: rhingson@mail.nih.gov

A

CCORDING TO ANALYSISof the NationalEpidemio-logic Study of Alcohol Related Conditions

(NESARC), 12.5% of US adults (⬎26 million Americans)

met Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) alcohol-dependence criteria at

some point in their lives.1Onset of alcohol dependence

peaks at age 18, with rapidly declining onsets after age 25.2

Starting to drink at younger ages has been linked to a greater likelihood of ever experiencing alcohol

depen-dence3after controlling for family history of alcoholism,

age, gender, race, and ethnicity,4history of cigarette and

other drug use, education, marital status,5and history of

childhood antisocial behavior and major depression.6

This relationship has been observed in cross-sectional3,4

and longitudinal7 studies. Early onset of drinking has

also been linked among adolescents and adults to epi-sodes after drinking of unintentional injuries, motor

ve-hicle crashes, and physical fights,5,8–10 unplanned and

unprotected sex,11and nicotine dependence, illicit

sub-stance use, antisocial personality, conduct disorder, and

academic underachievement.12

Most recently, early drinking onset was found to be associated with onset of alcohol dependence within 10 years of drinking onset, before age 25, and chronic re-lapsing dependence characterized by experiencing mul-tiple episodes of dependence, past-year dependence among adults of all ages, and, if dependent, episodes of longer duration and a wider array of diagnostic symp-toms. These relations were found after controlling for demographic and other characteristics related to age of drinking onset as well as childhood antisocial behavior,

major depression, and family history of alcoholism.6

Unexplored, and our focus in this study, is whether early onset of alcohol dependence is associated with seeking alcohol-related help or treatment and experi-encing chronic relapsing dependence independent of age of first starting to drink. We hypothesized that those who develop dependence at younger ages are less likely to seek treatment, in part because heavier drinking pat-terns are more common among adolescents and young adults. We also hypothesized that earlier age of first dependence would be associated with chronic relapsing dependence.

METHODS

In 2001–2002 the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse

and Alcoholism (NIAAA) conducted the NESARC.1

Un-der contract with and supervised by the NIAAA, the US Census Bureau conducted face-to-face interviews with a multistage probability sample of 43 093 adults, with a response rate of 81%. The survey methods and other

quality-control procedures were detailed by Grant et al.1

The research protocol, including informed-consent pro-cedures, received full ethical review and approval from

the US Census Bureau and Office of Management and Budget.

Diagnostic Assessment of Alcohol Dependence

The NESARC used the NIAAA Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview (schedule DSM-IV ver-sion), a state-of-the-art structured diagnostic interview designed for use by nonclinician lay interviewers. Com-puter algorithms were designed to produce diagnoses of abuse and dependence consistent with the final DSM-IV criteria.

Numerous national and international studies have documented the reliability and validity of the NIAAA Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Inter-view (schedule DSM-IV version) alcohol abuse and

de-pendence criteria,4,13–21including clinical reappraisals by

psychologists in clinical and general-population samples. Lifetime and past-year alcohol dependence based on DSM-IV variables from the NESARC was defined by 7 diagnostic criteria: tolerance; the withdrawal syndrome or drinking to relieve or avoid withdrawal symptoms; drinking larger amounts or for a longer period than intended; persistent desire or unsuccessful attempts to cut down on drinking; spending a great deal of time obtaining alcohol, drinking, and recovering from effects of drinking; giving up important social, occupational, or recreational activities in favor of drinking; and contin-ued drinking despite physical or psychological problems caused by drinking. A diagnosis of alcohol dependence required that respondents satisfy 3 of 7 criteria for de-pendence in the past year or during any year before the past year. Past-year dependence also required clustering, as specified in DSM-IV, of at least 3 dependence criteria in any 1 year of the respondent’s life. Lifetime diagnosis included all respondents dependent in the past year or before the past year. Alcohol-dependence withdrawal criteria required at least 2 positive symptoms of with-drawal as defined by the DSM-IV alcohol-withwith-drawal

diagnosis. Age of dependence was categorized as⬍18, 18

to 20, 21 to 24, 25 to 29, andⱖ30 years.

Duration criteria associated with dependence criteria in the NESARC define the repetitiveness with which these diagnostic criteria must occur for dependence. They were operationalized by using qualifiers such as “recurrent,” “often,” and “persistent” and embedded di-rectly into the symptom questions.

We examined several dependence outcomes: lifetime dependence, past-year dependence, chronic relapsing

dependence characterized by experiencing ⱖ2 episodes

of dependence, and dependence episodes exceeding 1 year and experiencing 6 to 7 dependence-symptom cri-teria for lifetime and past-year dependence.

Persons who met DSM-IV dependence criteria were asked how old they were the first time some of these experiences began to happen around the same time.

respondents who ever experienced dependence were asked, “In your entire life how many separate periods like this did you have when some of these experiences were happening around the same time? By separate periods, I mean times that were separated by at least 1 year when you either stopped drinking entirely or you didn’t have any of the experiences you mentioned with alcohol at all.”

Among persons ever diagnosed as dependent, dura-tion of longest dependence was ascertained by asking about the longest period those respondents had when some of these experiences were happening around the same time.

Persons with lifetime alcohol dependence or past-year dependence were stratified into those who met 6 to 7 vs 3 to 5 dependence diagnostic criteria.

Other Variables

To examine drinking patterns, respondents were asked, “During the past 12 months, about how often did you drink any alcoholic beverages? How many drinks did you usually have on days when you drank? What was the largest number of drinks that you drank in a single day? How often did you drink enough to feel intoxicated or drunk, that is, your speech was slurred, you felt unsteady on your feet, or you had blurred vision?” Re-spondents were also asked their age when they first started to drink, not counting tastes or sips of alcohol.

Family history of alcohol problems was positive if any first-degree relatives (mother, father, sister[s], broth-er[s], son[s], or daughter[s]) had an alcohol problem. Antisocial behavior was positive if respondents reported

ⱖ3 antisocial behaviors before age 15, and depression

was based on meeting DSM-IV criteria before age 14. These were the age cutoffs in the NESARC instrument.

Reliability for depression has been found to be good (⫽

0.64).22,23

Respondents were asked if they ever or in the past year used 1 of 10 types of drugs: sedatives, tranquilizers, pain killers, stimulants, marijuana, cocaine, hallucino-gens, inhalants, heroin, or other medicines. Tobacco

us-ers were respondents who ever smokedⱖ100 cigarettes.

Respondents were also asked, “Have you ever gone anywhere or seen anyone for a reason that was related in any way to your drinking—a physician, counselor, Alcoholics Anonymous, or any other community agency or professional?” Thirteen different counseling or treat-ment options were explored, including both inpatient and outpatient treatment ranging from detoxification clinics to self-help groups such as Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous. They were also asked their age when they first sought help, whether they ever thought they should seek help for their drinking but did not go, and reasons for not getting help.

Data Analysis

SUDAAN,24 a software program that uses Taylor series

linearization to adjust for the complex survey design, was used for all analyses.

Analyses focused only on respondents who met

alco-hol-dependence criteria at some point in their lives.2

analyses tested the significance of associations between age of onset of alcohol dependence, background charac-teristics, other dependence outcomes, and whether those who were alcohol dependent at some point in their lives ever sought help or treatment related to their alcohol problems.

With logistic-regression analysis we examined the re-lationship between age of first alcohol dependence and whether respondents sought help or treatment related to their drinking while controlling for the numbers of the 7 DSM-IV dependence criteria that respondents met when they were first diagnosable with alcohol dependence. The analysis also controlled for background characteris-tics known to be related to age of first alcohol depen-dence (namely, age, gender, race/ethnicity, income, marital status, past and current history of smoking and illicit drug use, expression of antisocial behavior before age 15 and depression before age 14, family history of alcoholism, and age of drinking onset).

With another series of logistic-regression analyses we examined the relationships between age of first alcohol dependence and the various dependence outcomes while controlling for the background characteristics known to be related to age of first dependence cited above as well as whether respondents ever sought alco-hol-related help or treatment. A similar series of logistic regressions examined, among respondents who were alcohol dependent during the survey year, relationships between age of first alcohol dependence and whether in

the past year respondents on ⱖ1 occasion per week

drank ⱖ5 drinks and to intoxication. These regressions

were repeated by entering age of drinking onset as a covariate.

The NESARC surveyed adults 18 and older. In anal-yses focusing on events that may occur after the onset of alcohol dependence, respondents’ time at risk varies; a 35-year-old respondent with first dependence at 21 has had more opportunity for relapse than a 35-year-old with first dependence at 31. To control for time since dependence onset, we stratified the sample into 3

groups: those surveyed within 5, 5 to 10, and⬎10 years

after initial dependence onset. Secondary analyses as-sessed the association between age of dependence onset

and subsequent dependence episodes, episodes⬎1 year,

and 6 to 7 dependence symptoms within each of these subsamples. Current age was not included as a covariate, because within each of these subpopulations current age is highly correlated with age of dependence onset.

alcohol dependence to those first dependent at age 30 or older (referent group) on the likelihood of seeking alco-hol-related help or treatment and other dependence outcomes. For those dependent in the past year, we also

examined frequency of ⱖ5 drinks on an occasion and

drinking to intoxication.

RESULTS

As noted earlier, at some point in their lives, 12.5% of the NESARC sample met DSM-IV alcohol-dependence criteria, 19% of people who ever drank alcohol. In the survey year, 3.8% of the sample (representing 8 million people) met alcohol-dependence criteria. Of those ever dependent, 15% were first dependent before age 18, 32% age 18 to 20, 22% age 21 to 24, 11% ages 25 to 29, and 21% at age 30 or older. Twenty-eight percent

re-portedⱖ2 alcohol-dependence episodes. Forty-five

per-cent experienced an episode⬎1 year, and 34% reported

at least 6 of 7 dependence criteria.

Of note, earlier age of alcohol-dependence onset was predictably associated with a shorter duration between ages of drinking onset and first dependence (Pearson

correlation:r⫽0.91;P⬍.0001).

Twenty-five percent of those who were ever alcohol dependent at some point sought help or treatment for a reason related their drinking. Most (80%) sought help during the same year that they became dependent or later. The mean time between onset of dependence and first seeking help was 4 years (median: 2 years). Respon-dents first dependent at younger ages were less likely to have sought help (28% of persons with alcohol depen-dence before age 18 and 17% between age 18 and 20

compared with 35% of those first dependent at ageⱖ30

[P⬍.0001]). Among those who sought help, those with

earlier onset took longer to do so. The percentage that

waited ⱖ10 years after dependence onset to seek help

was 31%, 24%, 28%, 21%, and 10% for those first dependent before age 18, between 18 and 20, between

20 and 24, between 25 and 30, and after 30 (P⬍.0001),

respectively.

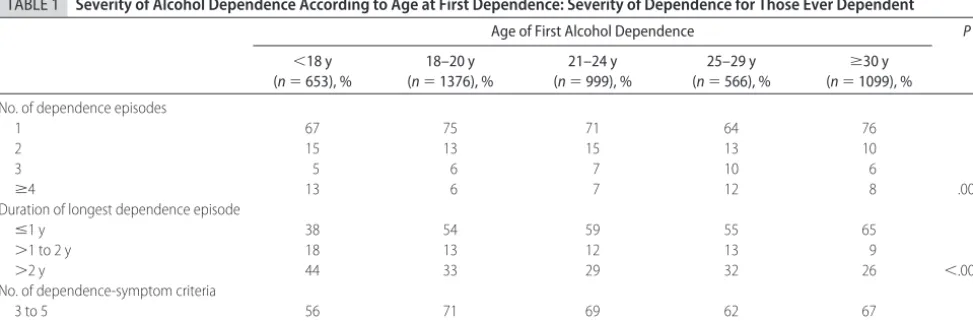

Respondents who were first alcohol dependent at younger ages were also more likely to have experienced multiple episodes of alcohol dependence, episodes of longer duration, and a wider array of alcohol-depen-dence diagnostic symptoms (Tables 1 and 2).

Age of first dependence was not associated with a greater likelihood of being alcohol dependent during the survey year. However, among persons who were alcohol dependent during the survey year, 58% of those first dependent before age 18 drank to intoxication at least once per week compared with 19% of those first

depen-dent at age 30 or older (P⬍.0001).

Logistic-regression analysis controlling for the num-ber of DSM-IV alcohol-dependence criteria that respon-dents met when they were first diagnosable for alcohol dependence confirmed that the earlier the age of first dependence, the less likely respondents were to seek alcohol-related help or treatment. Compared with per-sons first diagnosable after age 30, the odds of ever seeking help were lower among those first alcohol de-pendent before age 18 (OR: 0.50; 95% CI: 0.35– 0.70), between 18 and 20 (OR: 0.44; 95% CI: 0.34 – 0.59), and between 21 and 24 (OR: 0.59; 95% CI: 0.44 – 0.79).

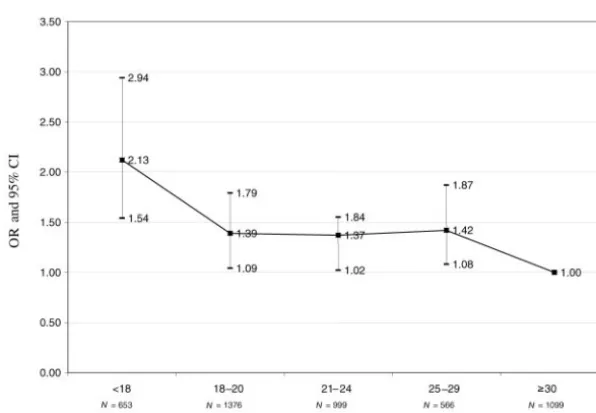

Also, after controlling for background characteristics associated with early dependence onset and whether they ever sought alcohol-related treatment, compared with respondents first dependent at age 30 or older, those who were alcohol dependent before age 18 had

higher odds of havingⱖ2 alcohol-dependence episodes

(OR: 2.03; 95% CI: 1.51–2.73), episodes lasting⬎1 year

(OR: 10.13; 95% CI: 7.38 –13.91), and 6 to 7 vs 3 to 5 dependence symptoms (OR: 2.13; 95% CI: 1.54 –2.94) (Figs 1–3).

Those who were first dependent before age 18, at ages 18 to 20, and at ages 21 to 24 were also more likely if they were dependent in the past year to experience 6 to

TABLE 1 Severity of Alcohol Dependence According to Age at First Dependence: Severity of Dependence for Those Ever Dependent

Age of First Alcohol Dependence P

⬍18 y (n⫽653), %

18–20 y (n⫽1376), %

21–24 y (n⫽999), %

25–29 y (n⫽566), %

ⱖ30 y (n⫽1099), % No. of dependence episodes

1 67 75 71 64 76

2 15 13 15 13 10

3 5 6 7 10 6

ⱖ4 13 6 7 12 8 .0036

Duration of longest dependence episode

ⱕ1 y 38 54 59 55 65

⬎1 to 2 y 18 13 12 13 9

⬎2 y 44 33 29 32 26 ⬍.0001

No. of dependence-symptom criteria

3 to 5 56 71 69 62 67

7 vs 3 to 5 alcohol-dependence symptoms, compared with those first dependent after 30 (OR: 3.17; 95% CI: 1.52– 6.62; OR: 3.75; 95% CI: 1.68 – 8.38; and OR: 2.61; 95% CI: 1.28 –5.29, respectively). Age of first

depen-dence was the strongest predictor in the regression anal-yses of this outcome. Generally, each age grouping ear-lier than 30 that respondents first became alcohol dependent, the higher the odds that they would

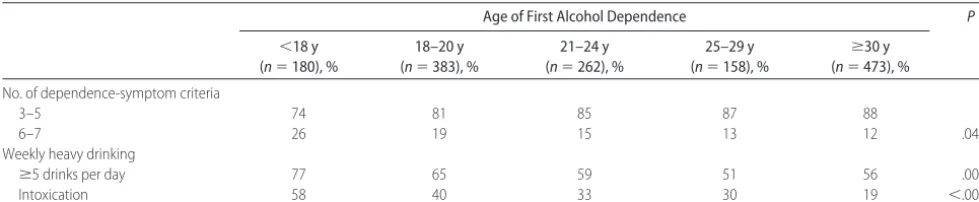

experi-TABLE 2 Severity of Alcohol Dependence According to Age at First Dependence: Severity of Dependence for Those Dependent 1 Year Before the Survey

Age of First Alcohol Dependence P

⬍18 y (n⫽180), %

18–20 y (n⫽383), %

21–24 y (n⫽262), %

25–29 y (n⫽158), %

ⱖ30 y (n⫽473), % No. of dependence-symptom criteria

3–5 74 81 85 87 88

6–7 26 19 15 13 12 .0447

Weekly heavy drinking

ⱖ5 drinks per day 77 65 59 51 56 .0007

Intoxication 58 40 33 30 19 ⬍.0001

FIGURE 1

Relative odds of persons experiencingⱖ2 alcohol-depen-dence episodes according to age at first depenalcohol-depen-dence. ORs are relative to those who were first dependent at age 30 or older. Age, gender, race/ethnicity, highest grade in school, current marital status, former and current smoking, former and current drug use, family history of alcoholism, antisocial behavior be-fore age 15, depression bebe-fore age 14, and whether respon-dents ever sought alcohol treatment were controlled for.

FIGURE 2

ence multiple episodes of dependence, episodes of longer

duration, and episodes with ⱖ6 diagnostic symptoms

during their first dependence episode and during the survey year. If dependent during the survey year, they were also more likely to experience weekly episodes of intoxication.

To more directly control for time at risk in the analysis of subsequent dependence episodes, we conducted sep-arate analyses for respondents surveyed within 5 years

(n⫽1325), between 5 and 10 years (n⫽658), and⬎10

years from the initial onset of dependence (n⫽2710).

Generally, the effect of early dependence was strongest for those surveyed within 5 years of initial dependence. Comparing those with first dependence before 18 vs

ⱖ30 while controlling for other demographic and risk

factors, the ORs of experiencing subsequent dependence episodes for those surveyed within 5 years, 5 to 10 years,

and⬎10 years after first dependence were 3.80 (95% CI:

1.69, 8.54), 0.86 (95% CI: 0.43–1.72), and 0.84 (95% CI: 0.58 –1.22), respectively. For duration of dependence

⬎1 year, the ORs were 7.20 (95% CI: 3.21–16.16), 2.21

(95% CI: 1.02– 4.75), and 2.08 (95% CI: 1.43–3.02), and for having 6 or 7 dependence symptoms the ORs were 2.04 (95% CI: 1.03– 4.02), 3.28 (95% CI: 1.53–7.05), and 1.19 (95% CI: 0.79 –1.80), respectively.

Among persons who were ever alcohol dependent (the focus of this study), when age of drinking onset was added to the regression analyses as a covariate, relations were not altered between age of first alcohol depen-dence and chronic relapsing dependepen-dence measures such as number of dependence episodes and experiencing

episodes⬎1 year. In most analyses, age of drinking onset

was not significantly related to measures of chronic re-lapsing dependence, whereas early age of first depen-dence was related (data are available on request).

There was, however, one exception. Compared with

persons who began drinking at age 21 or older, persons who began before age 14 (OR: 2.09; 95% CI: 1.37–3.21) and at ages 14 (OR: 2.42; 95% CI: 1.60 –3.65), 15 (OR: 1.90; 95% CI: 1.33–2.72), 16 (OR: 1.44; 95% CI: 1.04 – 1.98), and 19 (OR: 1.94; 95% CI: 1.31–2.88) were more likely to have 6 to 7 alcohol-dependence symptoms. Simultaneously, when age of drinking onset was a co-variate in the regression, the relation between age of first dependence and experiencing 6 to 7 vs 3 to 5 symptoms was weakened among those first dependent before age 18 (OR: 1.64; 95% CI: 1.16 –2.32) and at ages 18 to 20 (OR: 1.26; 95% CI: 0.97–1.65), 21 to 24 (OR: 1.31; 95% CI: 0.97–1.77), and 25 to 29 (OR: 1.41; 95% CI: 1.06 – 1.86).

DISCUSSION

Previous research indicated that the earlier people begin to drink, the more likely they are to experience alcohol dependence within 10 years of drinking onset, and be-fore age 25. Analyses controlled for numerous sociode-mographic characteristics associated with starting to drink at a younger age as well as drug use and smoking history, family history of alcoholism, and childhood his-tory of antisocial personality and major childhood

de-pression.6Earlier drinkers are also more likely to

expe-rience chronic relapsing dependence characterized by more and longer episodes and more dependence

symp-toms.6

This study reveals that among persons who were ever alcohol dependent, those diagnosable before age 25 were less likely to seek alcohol-related help or treatment after controlling for number of dependence symptoms. In addition, if they sought help, they waited longer after dependence onset to do so. After controlling for whether they ever sought alcohol treatment and age of drinking onset, they were also more likely to experience

indica-FIGURE 3

tors of chronic relapsing alcohol dependence including multiple dependence episodes and longer episodes with a wider variety of symptoms. These associations were strongest among persons interviewed within 5 years of first dependence, where recall may be most clear. These relations were observed although persons who experi-enced these indicators were more likely to have sought treatment. Among those still alcohol dependent during the survey year, the earlier they were first diagnosable, the more likely they were to drink to intoxication at least once per week.

All of the observed relations persisted after also con-trolling for numerous characteristics associated with early age onset of alcohol dependence, including demo-graphics, personal history of smoking and illicit drug use, family history of alcoholism, childhood antisocial per-sonality disorder, and major depression. This suggests that the association of early age of onset of alcohol dependence and chronic relapsing dependence may not be solely a function of greater risk taking of those first dependent at a young age as reflected by these measures. Of course, there may be other markers of risk taking not included in the study that could not be analytically controlled.

Given these relations, it is a great concern that the peak year of alcohol-dependence onset is age 18 and that nearly half of the persons in this national survey of adults who met DSM-IV dependence criteria first did so before the age of 21, the minimum legal drinking age in all states.

Several issues should be considered in interpreting these results. First, this survey required some respon-dents to recall onset of drinking and symptoms of de-pendence, childhood depression, and antisocial behavior many years earlier. Despite excellent response rates and analytic controls for respondent age and numerous other personal and behavioral characteristics, prospective studies are needed to establish causality.

Second, social desirability biases may foster underre-ported alcohol use and problems prompting underdiag-nosis of alcohol dependence. On the other hand, persons willing to report heavy drinking may be less hesitant than others to report adverse drinking consequences. Also, people with alcohol dependence may be more likely to remember when they started to drink and early dependence symptoms because of drinking conse-quences later in life. That could have contributed to observation of stronger relations between age of first dependence and measures of chronic relapsing depen-dence.

Third, although the reliability of the DSM-IV depen-dence measure has been extensively measured and es-tablished, similar work is needed for measures of num-ber of alcohol-dependence episodes and duration of those episodes. Evaluations of those outcomes should proceed cautiously.

Fourth, some researchers have questioned whether the meaning of DSM-IV alcohol-dependence criteria dif-fers in adolescents and adults. During adolescence, in-creased tolerance is probably a normal developmental

phenomenon.25Also, the criteria “using more than

in-tended” may have more to do with social influences

than compulsion to drink.26,27This might result in

non-dependent adolescents qualifying as non-dependent. In this study, almost all persons diagnosed as alcohol dependent reported both of these symptoms. Given this concern, the relation observed between diagnosis of alcohol de-pendence at an early age and measures of chronic re-lapsing dependence is more remarkable.

Fifth, although this analysis analytically controlled for numerous potential variables that might confound relations between first alcohol dependence and charac-teristics of chronic relapsing dependence, questions re-garding the causality of the associations remain. Con-founding variables not considered in the survey may be associated both with early alcohol-dependence onset and features of chronic relapsing dependence. Persons who acquire early onset of alcohol dependence may be genetically predisposed to chronic relapsing dependence and may have other life experiences not explored here that contribute to chronic relapsing dependence (eg, physical or psychological abuse as children, parental psy-chopathology, or parental separation when they were children). Persons with these childhood experiences may start drinking at an early age and may continue to drink excessively even after becoming dependent to cope with posttraumatic stress syndrome. It is also pos-sible that very early onset contributes to neural changes or greater tolerance to intoxication or pleasurable effects of alcohol, thereby prompting greater maladaptive ex-posure to alcohol to obtain the desired effects. Of note, some persons with early alcohol dependence perma-nently overcome this dependence, although as a group they are less likely to do so than persons who first became dependent after age 30.

Sixth, some respondents may have been too young to have developed alcohol dependence at the ages studied in this analysis. For example, respondents younger than age 30 could not have developed dependence at age 30 or older in this cross-sectional survey. To adjust for this, we entered age as a variable in our analysis. We also repeated the analysis only among respondents age 35 and older. A similar pattern of relationships was ob-served, although most were stronger among persons ever dependent who were younger than age 35, where recall problems are less likely (data are available on request).

However, unlike age of first alcohol dependence, age of drinking onset was not a significant independent predic-tor of multiple and longer episodes of dependence. The previously reported increased odds of persons who start to drink at an early age developing features of chronic

relapsing dependence6may be largely a function of their

developing alcohol dependence at an early age, which in turn increases the odds of multiple and longer episodes of alcohol dependence.

Eighth, in this survey, age of first dependence was not associated with whether respondents who believed they needed help declined to seek it. However, younger age of first dependence was associated with a greater likeli-hood of citing several reasons for not seeking help. Rel-ative to those first dependent at age 30 or older, those first dependent by age 18 were more likely to indicate that they wanted to continue drinking (26% vs 16%), thought the problem would get better by itself (44% vs 30%), did not think anyone could help (22% vs 12%), did not know where to go (14% vs 3%), could not afford to pay for treatment (21% vs 15%), did not have time (15% vs 6%), and were afraid they would be hospital-ized (17% vs 8%).

Questions in this survey do not explain why persons diagnosable with alcohol dependence at early ages are less likely to recognize their drinking-related problems. Fewer marital, family, or work responsibilities among younger persons are one possible explanation. Also, be-cause episodes of heavy drinking are more common among youth in general, those with early dependence onset and their family and friends may be less likely to recognize their dependence.

Those considerations not withstanding our analyses underscore the importance of systematically exploring and counseling adolescent patients about their drinking. A recent study found that pediatric medical care provid-ers considerably underdiagnose alcohol use, abuse, and

dependence among patients 14 to 18.21Yet, early onset

of drinking predicts early onset of dependence.6In

ad-dition, this analysis indicated that 15% of persons who were ever alcohol dependent are dependent before age 18, 47% are dependant before the legal drinking age of 21, and early onset of dependence is, in turn, associated with features of chronic relapsing dependence. Screen-ing and brief motivational counselScreen-ing can reduce alco-hol-related problems among adolescents and college

stu-dents who are heavy risky drinkers29,30and needs to be

expanded. Also, raising the legal drinking age to 21 reduced drinking, alcohol-related traffic deaths, and deaths from other unintentional injuries among persons

under 21.31–33A national analysis found that the law also

reduced drinking among people when they became 21

to 25 years of age,33 but the effect of the law on the

proportion of persons who develop alcohol dependence during adolescent or adult years has not been studied. Additional research is needed to explore why many

adolescents become alcohol dependent at an early age and why some who do are more likely to develop chronic relapsing dependence. Whether this greater like-lihood of chronic relapsing dependence results primarily from lack of exposure to alcohol-related treatment or other factors warrants immediate investigation. Studies are needed to examine the effects of screening adoles-cent populations for alcohol problems and offering counseling in a wider variety of settings such as school-based clinics and general pediatric settings. Most impor-tant, research is urgently needed to identify ways to prevent development of alcohol dependence, particu-larly at an early age.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

REFERENCES

1. Grant B, Dawson D, Stinson F, Chou S, Dufour M, Pickering R. The 12-month prevalence and trends in DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: United States, 1991–1992 and 2001–2002. Drug Alcohol Depend.2004;74:223–234

2. Li TK, Hewett BG, Grant BF. Alcohol use disorders and mood disorders: a National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcohol-ism perspective.Biol Psychiatry.2004;56:718 –720

3. Grant BF, Dawson DA. Age at onset of alcohol use and its association with DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: re-sults from the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey.J Subst Abuse.1997;9:103–110

4. Grant B. The impact of family history of alcoholism on the relationships between age at onset of alcohol use and DSM IV dependence.Alcohol Health Res World.1998;22:144 –147 5. Hingson R, Heeren T, Jamanka A, Howland J. Age of drinking

onset and unintentional injury involvement after drinking. JAMA.2000;284:1527–1533.

6. Hingson RW, Heeren T, Winter MR. Age at drinking onset and alcohol dependence: age at onset, duration, and severity.Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med.2006;160:739 –746

7. Grant BF, Stinson FS, Harford TC. Age at onset of alcohol use and DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: a 12-year follow-up.J Subst Abuse.2001;13:493–504

8. Hingson R, Heeren T, Zakocs R. Age of drinking onset and involvement in physical fights after drinking.Pediatrics.2001; 108:872– 877

9. Hingson R, Heeren T, Levenson S, Jamanka A, Voas R. Age of drinking onset, driving after drinking, and involvement in alcohol related motor-vehicle crashes.Accid Anal Prev.2002;34: 85–92

10. Hingson R, Heeren T, Zakocs R, Winter M, Wechsler H. Age of first intoxication, heavy drinking, driving after drinking and risk of unintentional injury among U.S. college students.J Stud Alcohol.2003;64:23–31

11. Hingson R, Heeren T, Winter MR, Wechsler H. Early age of first drunkenness as a factor in college students’ unplanned and unprotected sex attributable to drinking.Pediatrics.2003;111: 34 – 41

12. McGue M, Iacono WG, Legrand LN, Elkins I. Origins and consequences of age at first drink. II.Familial risk and herita-bility. Alcohol Clin Exp Res.2001;25:1166 –1173

mea-sured by AUDADIS-ADR, CIDI, and SCAN.Drug Alcohol De-pend.1997;47:195–205

14. Grant BF. DSM-III-R and ICD-10 alcohol and drug abuse/ harmful use and dependence, United States, 1992; a nosolog-ical comparison.Alcohol Clin Exp Res.1996;21:79 – 84 15. Grant BF, Harford TC, Dawson DA, Chou PS, Pickering R. The

Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Schedule (AUDADIS): reliability of alcohol and drug modules in a gen-eral population sample.Drug Alcohol Depend.1995;39:37– 44 16. Hasin D, Li Q, McCloud S, Endicott J. Agreement between

DSM-III-R, DSM-IV and ICD-10 alcohol diagnosis in a US community-sample of heavy drinkers. Addiction. 1996;91: 1517–1527

17. Hasin D, Carpenter KM, McCloud S, Smith M, Grant BF. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule (AUDADIS): reliability of alcohol and drug modules in a clinical sample.Drug Alcohol Depend.1997;44:133–141 18. Hasin D, Grant BF, Cottler L, et al. Nosological comparisons of

alcohol and drug diagnoses: a multisite, multi-instrument in-ternational study.Drug Alcohol Depend.1997;47:217–226 19. Hasin D, Van Rossem R, McCloud S, Endicott J. Differentiating

DSM-IV alcohol dependence and abuse by course: community heavy drinkers.J Subst Abuse.1997;9:127–135

20. Hasin DS, Paykin A. Alcohol dependence and abuse diagnosis: concurrent validity in a nationally representative sample. Al-cohol Clin Exp Res.1999;23:144 –150

21. Ustun B, Compton W, Mager D, et al. WHO study on the reliability and validity of the alcohol and drug use disorder instruments: overview of methods and results [published cor-rection appears inDrug Alcohol Depend. 1998;50:185–186].Drug Alcohol Depend.1997;47:161–170

22. Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, et al. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions.Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:807– 816

23. Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou PS, Kay W, Pickering R. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Inter-view Schedule-IV (AUDADIS-IV): reliability of alcohol

con-sumption, tobacco use, family history of depression and psy-chiatric diagnostic modules in a general population sample. Drug Alcohol Depend.2003;71:7–16

24. Software for Survey Data Analysis (SUDAAN) [computer soft-ware]. Version 8.1. Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Tri-angle Institute; 2002

25. Martin C, Winter K. Diagnosis and assessment on alcohol use disorders among adolescents.Alcohol Health Res World.1998;22: 95–105

26. Chung T, Martin C. Concurrent and discriminate validity of DSM IV symptoms of impaired control over alcohol consump-tion in adolescents.Alcohol Clin Exp Res.2002;26:485– 492 27. Cooper M. Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents:

development and validation of a four factor model. Psychol Assess.1994;117–128

28. Wilson C, Sherritt L, Gates E, Knight JR. Are clinical impres-sions of adolescent substance abuse use accurate? Pediatrics. 2004;114(5). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/ full/114/5/e536

29. O’Leary Tevyaw T, Monti P. Motivational environment and other brief interventions for adolescent substance abuse: foun-dations, applications and evaluations.Addiction.2004;99(suppl 2):63–75

30. Larimer M, Cronce J. Identification, prevention and treatment: a review of individual focused strategies to reduce problematic alcohol consumption by college students.J Stud Alcohol Suppl. 2002;(14):148 –163

31. Shults RA, Elder RW, Sleet DA, et al. Reviews of evidence regarding interventions to reduce alcohol impaired driving [published correction appears inAm J Prev Med. 2002;23:72]. Am J Prev Med.2001;21(4 suppl):66 – 88

32. Wagenaar AC, Toomey TL. Effects of minimum drinking age laws: review and analysis of the literature from 1960 to 2000. J Stud Alcohol Suppl.2002;(14):206 –225

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2006-0223

2006;118;e755

Pediatrics

Ralph W. Hingson, Timothy Heeren and Michael R. Winter

and Seeking Treatment

Age of Alcohol-Dependence Onset: Associations With Severity of Dependence

Services

Updated Information &

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/118/3/e755 including high resolution figures, can be found at:

References

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/118/3/e755#BIBL This article cites 29 articles, 2 of which you can access for free at:

Subspecialty Collections

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/substance_abuse_sub Substance Use

following collection(s):

This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

Permissions & Licensing

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml in its entirety can be found online at:

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

Reprints

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2006-0223

2006;118;e755

Pediatrics

Ralph W. Hingson, Timothy Heeren and Michael R. Winter

and Seeking Treatment

Age of Alcohol-Dependence Onset: Associations With Severity of Dependence

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/118/3/e755

located on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 1073-0397.