ARTICLE

Associations Between Maternal Age and Infant Health

Outcomes Among Medicaid-Insured Infants in South

Carolina: Mediating Effects of Socioeconomic Factors

William B. Pittard, III, MD, PhD, MPHa, James N. Laditka, DA, PhD, MPAb, Sarah B. Laditka, PhD, MA, MBAc

aDivision of Pediatric Epidemiology and Health Systems Research, Department of Pediatrics, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, South Carolina;

Departments ofbEpidemiology and Biostatistics andcHealth Services Policy and Management, Arnold School of Public Health, University of South Carolina, Columbia,

South Carolina

The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

What’s Known on This Subject

Health status and health care utilization of infants of adolescent mothers has been less well described than their mothers’ reproductive outcomes. Studies of this issue, which are primarily descriptive, have had mixed results.

What This Study Adds

This study provides well-controlled empirical investigation of health care use by infants of adolescent mothers needed by physicians and policy makers to appropriately design interventions to improve health status and coordinate health service use.

ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVE.The objective of this study was to investigate whether infants who are born to adolescent mothers are at greater risk for health problems than those who are born to older mothers.

METHODS.Data represent all health care encounters for infants who were born in South Carolina between 2000 and 2002 and were healthy at birth and continuously enrolled in fee-for-service Medicaid (n⫽ 41 696). We separately examined in the first and second years of life use of preventive care doctor visits, sick-infant doctor visits, emergency department visits, hospital admissions, and both emergency de-partment visits and hospitalizations for ambulatory care–sensitive conditions. We compared these outcomes for infants of adolescent mothers (aged 11–17 years) and older mothers (aged 18 – 47 years), adjusting for individual characteristics of mothers and infants.

RESULTS.In unadjusted results, infants of adolescent mothers used more health care in 9 of 12 use categories. For example, in year 1, they had an average of 1.71 emergency department visits and 1.39 hospitalizations, compared with 1.26 and 1.18, respec-tively, for infants of older mothers. In results that were adjusted only for infant and delivery characteristics, they similarly used more services in most categories. After adjustment for either mothers’ characteristics alone or those of both the infant/ delivery and mothers, there was evidence that they had modestly more sick-infant doctor visits and hospital admissions in year 1 and notably more hospital admissions for ambulatory care–sensitive conditions.

CONCLUSIONS.Infants of adolescent mothers are more likely than infants of older mothers to use a variety of health care services that suggest poorer health. A considerable proportion of this greater use seems to be attributable to specific characteristics of mothers, such as socioeconomic characteristics, rather than to an inability that is common among adolescents to promote infant health or to use health care appropriately.Pediatrics2008;122:e100–e106

A

DOLESCENT PREGNANCY ISa public health concern with striking psychological, social, and physiologic ramifica-tions for young women and their infants.1,2Numerous studies have described poor reproductive outcomes foradolescent pregnancy, attributing adverse events to a variety of causes, including lifestyle, ethnic and cultural background, socioeconomic status, marital status, education, place of residence, and inadequate accessibility and use of health care.3–8Some researchers suggested that socioeconomic status is a primary determinant of adverse outcomes

for adolescent pregnancies.9,10

Health status and health care use of infants of adolescent mothers has been less well described than their mothers’ reproductive outcomes. Studies of this issue, which are primarily descriptive, have mixed results. Some indicated more intentional and unintentional injury and hospitalization for infants of adolescents and a lack of

immuniza-www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/ peds.2007-1314

doi:10.1542/peds.2007-1314

Key Words

Medicaid, adolescent mothers, infant health care, socioeconomic status, ambulatory care sensitive conditions

Abbreviations

ED— emergency department FFS—fee for service

ACSC—ambulatory care–sensitive condition

FPL—federal poverty level EPSDT—Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment

AAP—American Academy of Pediatrics RR—rate ratio

CI— confidence interval

Accepted for publication Jan 2, 2008

Address correspondence to William B. Pittard III, MD, PhD, MPH, Medical University of South Carolina, Department of Pediatrics, Division of Pediatric Epidemiology and Health Systems Research, 165 Ashley Ave, PO Box 250917, Charleston, SC 29425. E-mail: pittardw@musc. edu.

tion.11–13 Others described no differences in emergency

department (ED) visits, hospitalizations, or immuniza-tions for infants of younger and older mothers.14–16

Limited available research suggested that the average adolescent mother has lower income than the average older mother, less education, and less awareness of her infant’s medical needs, suggesting less ability to promote infant health.2,8,17–19 The association between infant

health and socioeconomic status limits the usefulness of most studies of this issue, which typically rely on health care claims data that do not permit individual-level con-trols for characteristics such as education or income.20

Results of studies without individual-level controls for socioeconomic characteristics provide uncertain evi-dence about risks for infant health that may actually be attributable to characteristics of young mothers, such as an ability to promote infant health by using health care appropriately. Thus, well-controlled empirical investiga-tion of health care use by infants of adolescent mothers is needed by physicians and policymakers for appropri-ate design of interventions to improve health status and to coordinate health service use. If poor infant outcomes are an independent function of adolescent mothering, then efficient interventions might differ from those that would be appropriate if other factors account for these outcomes, such as mothers’ socioeconomic characteris-tics or serious conditions that affect infants at birth.

We used unique data from South Carolina to examine whether there were differences in infant health out-comes associated with maternal age, controlling for in-dividual-level socioeconomic characteristics of mothers and several infant characteristics. We hypothesized that, among term, appropriately grown infants who are in-sured by fee-for-service (FFS) Medicaid in South Caro-lina, those of adolescents and those of older mothers would have similar health care use, generally indicating similar health status, in their first 24 months of life, when socioeconomic characteristics are controlled. Spe-cifically, we hypothesized that infants of adolescent and older mothers use similar numbers of preventive-care doctor visits, sick-infant doctor visits, ED visits, hospital-izations, and both ED visits and hospitalizations for am-bulatory care–sensitive conditions (ACSCs).

METHODS

Population Studied

A total of 61 112 births were insured by Medicaid in South Carolina in 2000, 2001, and 2002. Among these, 59 216 (96.9%) were enrolled in FFS Medicaid at some time dur-ing the first 2 years of life. Infants are often not enrolled in their Medicaid insurance plan until sometime during the first month of life. Thus, we studied infants who were continuously enrolled in FFS Medicaid from the second through the 24th months of life and calculated the number of visits or stays for the first year on the basis of the second through 12th months of life. The requirement that infants must have been continuously enrolled in FFS excluded 1215 infants who switched from FFS to Medicaid managed care in the first 24 months. Another 25 infants whose insurance switched from Medicaid managed care to FFS

were also excluded from the analysis. The term “adolescent mother” is defined for this investigation as a mother who was younger than 18 years at the time of delivery. The threshold distinguishing adolescent and older mothers, age 18, was selected for consistency with previous studies.19,21

This age is consistent with high school graduation, voting, and increased independence.

The data, obtained from the South Carolina Budget and Control Board, Office of Research and Statistics, linked state Medicaid claims and birth certificate files. All infants who are insured by South Carolina Medicaid have low income (up to 185% of the federal poverty level [FPL]); therefore, restricting the investigation of infant health to those who were insured by Medicaid provided a useful degree of control for socioeconomic status. Furthermore, the South Carolina statewide Med-icaid data include detailed individual-level measures of socioeconomic characteristics of mothers, such as mari-tal status, level of income, and education, information that is not available in administrative data. Our previous research using the South Carolina Medicaid data indi-cated that the data and linkages required for this re-search have a high degree of completeness and validi-ty.21–24In this study, the linkage was successful for 94%

of the infants who were covered by Medicaid during the study years.

The usual expectation in research on this topic is that health outcomes are likely to be associated with mothers’ abilities to maintain infant health, to identify health prob-lems, and to seek an appropriate level of care in a timely manner when infant health care needs arise. Thus, it was desirable to exclude infants who had conditions that might predispose them to use the health care services that we examined. The study excluded infants with birth admis-sions that lastedⱖ7 days or with major heart diseases or conditions (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revi-sion, Clinical Modificationcodes 745.4, 745.5, 759.9, 747.41, 747.0, 745.1, 745.2, 746.7, 747.10, 746.87, and 745.0), central nervous system malformations (742.3, 742.1, 655.0, 653.60, and 653.63), genitourinary anomalies (752.7, 752.61, 752.62, and 752.51), gastrointestinal anomalies (751.2, 530.1, 750.3, and 751.4), musculoskeletal anoma-lies (756.9), and recognizable genetic malformations (758.0, 758.1, 758.2, 760.71, and 282.6).

Infants were also restricted to those who were term and appropriately grown at birth, by requiring at least 37 weeks’ gestational age, and infant birth weight within published fetal growth norms.25,26 Infants with birth

weight below the fifth percentile for infants aged 37 to 42 weeks or above the 95th percentile were excluded from the analysis. These restrictions excluded 16 280 infants; the majority of exclusions were attributed to birth anomalies (n⫽11 552), birth weight outside fetal growth norms (n ⫽ 6878), and gestational age ⬍37 weeks (n⫽7491). Of the infants excluded, 5913 met⬎1 of these criteria.

the South Carolina Data Oversight Commission, which supervises use of Office of Research and Statistics data.

Dependent Variables

Dependent variables that were analyzed in separate models included the number of Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment (EPSDT; preventive care) doctor visits; sick-infant doctor visits; ED visits; hospital admissions; and both ED visits and hospital admissions specifically for ACSCs. The specific diagnoses for ACSC ED visits and hospitalizations, identified using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clini-cal Modificationcodes, are those previously reported to be the most common ACSC diagnoses in ED and hospital settings for infants who are insured by Medicaid27:

asth-ma; seizure; cellulites; ear, nose, and throat infections; bacterial pneumonia; kidney/urinary tract infection; and gastrointestinal infections.

The EPSDT benefit, added to Medicaid in 1967, was designed to prevent disease in children and to detect and treat health problems before they become more seri-ous.28–30The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP)

rec-ommends 6 EPSDT visits in the first year of life and 3 in the second year.31,32These recommendations have been

endorsed by the South Carolina Department of Health and Human Services for infants who are enrolled in Medicaid. The number of infant EPSDT visits represents the combined number of visits for immunizations and/or screening services. EPSDT visits were identified using the Health Care Financing Administration Common Proce-dure Coding System codes and definitions published in the Physician’s Current Procedural Terminology.33 We

also examined, for each year of the analysis, whether the infant received the AAP-recommended number of EPSDT visits.

Exposure Variable

The exposure variable, or independent variable of pri-mary interest, was maternal age at delivery. For statisti-cal comparisons, this analysis dichotomizes infants into 2 groups: those whose mother was 11 to 17 years of age at the time of delivery and those whose mother was 18 to 47 years of age.

Control Variables

Control variables included a number of characteristics of mothers, such as education in years. Dummy variables indicated whether the mother was married; whether the mother was non-Hispanic white, black, Hispanic, another race or ethnicity, or had a missing value for race/ethnicity; family incomeⱕ50% of the FPL or greater (up to 185% of the FPL); maternal parity; whether the delivery was vagi-nal; whether the mother smoked, drank alcohol, or used illicit drugs during pregnancy; and whether the mother received adequate prenatal care, as defined by the Kessner Index of Prenatal Care Adequacy.34,35 Information about

maternal use of alcohol, tobacco, and illicit drugs during pregnancy was obtained by health care providers by asking the mothers about use during their postpartum hospital-ization and examining the mothers’ responses recorded on

birth certificates using specific diagnosis-related groups: al-cohol use (65811), tobacco use (65651), and illicit drug use (65801). We controlled for type of delivery, vaginal or cesarean section, because it has been reported that the birth of a child in any way out of the ordinary (surgical delivery) may create parental emotional discomfort that affects infant care through the first 2 years of life or longer.36

Also included in the model were several controls for infant characteristics. Rural/urban residential status was assigned on the basis of the largest town in the infant’s county of residence. Infants who resided in counties with a town of at least 25 000 residents were considered to reside in urban areas; those in remaining counties were considered to reside in rural areas. Additional in-fant controls were birth weight in grams, gender, and gestational age in weeks. These controls were included because parenting behaviors have been associated with such factors. Although we excluded infants with low birth weight or congenital conditions, it remained useful to include in the models individual-level measures of infant development because parental behavior is clearly influenced by even minor deviations from expecta-tion.37,38Gestational age and birth weight were

exam-ined for nonlinear associations with the outcome vari-ables by entering each measure into the models as a set of dummy variables. The results suggested that the as-sociations between both measures and the outcomes were generally linear, a result that is consistent with previous research. Thus, for providing the maximum adjustment for potential confounding across all levels of these measures, both were entered into the final models as continuous variables.

Statistical Analysis

Bivariate analyses compared characteristics of mothers and infants according to mother’s age group. 2 tests

were conducted for categorical data, and t tests were conducted for continuous measures.

Because the count data in the analysis exhibited overd-ispersion, negative binomial regression was used to com-pare rates of health care use for adolescent and older moth-ers. Overdispersion occurs when the variance of the dependent variable notably exceeds its mean. This data characteristic can seriously challenge the analysis of count data. When present, this phenomenon can produce under-estimates of SEs, leading to faulty conclusions about statis-tical significance. Negative binomial regression corrects the SEs.39Multivariate analyses assessed effects of maternal age

at delivery on each dependent variable, adjusted for rele-vant characteristics of the mothers and infants. Multicol-linearity was assessed for each regression model; multicol-linearity was not a problem for any of the analyses. Stata statistical software (Stata Corp, College Station, TX) was used for all analyses.

RESULTS

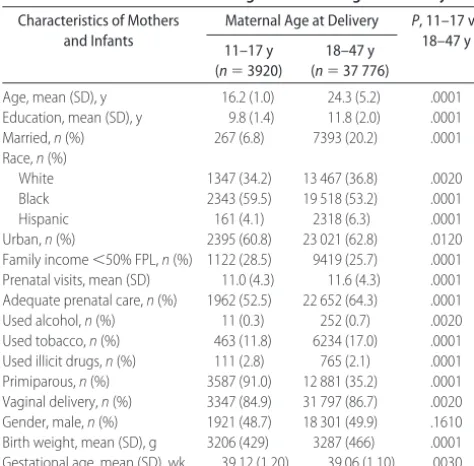

com-pared with 24.3 years for the older mothers. Adolescent mothers were less likely to be married (6.8% vs 20.2%), were more likely to be primiparous (91.0% vs 35.2%), and, as expected for adolescents, had lower educational attainment (9.8 vs 11.8 years; all P ⬍ .0001). Other differences between adolescent and older mothers were in most instances minor, although adolescents were less likely than older mothers to have an adequate rating on the Kessner Index of Prenatal Care Utilization (52.5% vs 64.3%;P⬍.0001).

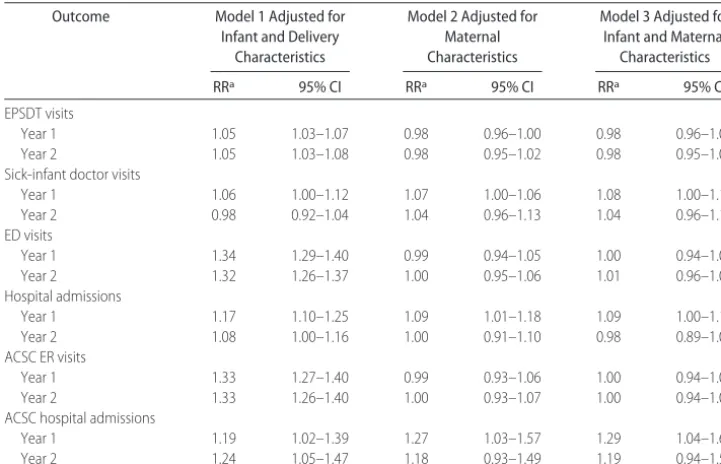

Table 2 shows the mean number of times each type of service was used by infants of adolescent and older mothers. Table 2 also shows the unadjusted ratios of these means (rate ratios [RRs]) and their confidence intervals (CIs), where the rate for infants of adolescent mothers is the numerator. An RR⬎1.00 indicates that infants of adolescent mothers used more of the service than infants of older mothers. For example, in year 1, infants of adolescents had an average of 1.71 ED visits, compared with 1.26 for infants of older mothers. Thus, the rate of ED visits in year 1 was 36% greater for infants of adolescent mothers than for infants of older mothers (RR: 1.36 [95% CI: 1.30 –1.41]). In these unadjusted results, infants of adolescent mothers used more health care in 9 of 12 service categories. Moreover, these dif-ferences seemed to be clinically significant in all but 2 of the comparisons: EPSDT visits in years 1 and 2. There were no significant differences between maternal age groups in the percentage of infants who received the AAP-recommended number of EPSDT visits in either year 1 or 2 (data not shown).

Table 3 presents results adjusted for socioeconomic factors and delivery characteristics shown in Table 1. Model 1 shows the results adjusted for infant and

deliv-ery characteristics only. Model 2 reports results adjusted only for maternal characteristics. Model 3 shows results adjusted for both infant/delivery characteristics and ma-ternal characteristics. For each model and outcome, Ta-ble 3 presents the adjusted RR associated with the co-variate indicating whether the mother was an adolescent or an adult and the corresponding CI. An RR of⬎1.00 suggested that infants of adolescent mothers had greater adjusted use of the given outcome. In model 1, the results suggested that infants of adolescent mothers were more likely to use services in 11 of the 12 categories, controlling for infant and delivery characteristics. The RRs suggesting this greater use were particularly notable for ED visits in both years 1 and 2 (respectively, RR: 1.34 [95% CI: 1.29 –1.40] and RR: 1.32 [95% CI: 1.26 – 1.37]), hospital admissions in year 1 (RR: 1.17 [95% CI: 1.10 –1.25]), ACSC ED visits in both years 1 and 2 (re-spectively, RR: 1.33 [95% CI: 1.27–1.40] and RR: 1.33 [95% CI: 1.26 –1.40]), and ACSC hospitalizations in both years 1 and 2 (respectively, RR: 1.19 [95% CI: 1.02–1.39] and RR: 1.24 [95% CI: 1.05–1.47]), with additional evidence of modestly greater use of sick-in-fant doctor visits in year 1 (RR: 1.06 [95% CI: 1.00 – 1.12]). When only mothers’ characteristics were con-trolled (model 2), there was again evidence of modestly greater use of sick-infant doctor visits in year 1 for in-fants of adolescents (RR: 1.07 [95% CI: 1.00 –1.06]) and of notably more hospital admissions in year 1 (RR: 1.27

TABLE 1 Bivariate Comparisons of Maternal and Infant Characteristics According to Maternal Age at Delivery

Characteristics of Mothers and Infants

Maternal Age at Delivery P, 11–17 vs 18–47 y 11–17 y

(n⫽3920)

18–47 y (n⫽37 776)

Age, mean (SD), y 16.2 (1.0) 24.3 (5.2) .0001 Education, mean (SD), y 9.8 (1.4) 11.8 (2.0) .0001 Married,n(%) 267 (6.8) 7393 (20.2) .0001 Race,n(%)

White 1347 (34.2) 13 467 (36.8) .0020 Black 2343 (59.5) 19 518 (53.2) .0001

Hispanic 161 (4.1) 2318 (6.3) .0001

Urban,n(%) 2395 (60.8) 23 021 (62.8) .0120 Family income⬍50% FPL,n(%) 1122 (28.5) 9419 (25.7) .0001 Prenatal visits, mean (SD) 11.0 (4.3) 11.6 (4.3) .0001 Adequate prenatal care,n(%) 1962 (52.5) 22 652 (64.3) .0001 Used alcohol,n(%) 11 (0.3) 252 (0.7) .0020 Used tobacco,n(%) 463 (11.8) 6234 (17.0) .0001 Used illicit drugs,n(%) 111 (2.8) 765 (2.1) .0001 Primiparous,n(%) 3587 (91.0) 12 881 (35.2) .0001 Vaginal delivery,n(%) 3347 (84.9) 31 797 (86.7) .0020 Gender, male,n(%) 1921 (48.7) 18 301 (49.9) .1610 Birth weight, mean (SD), g 3206 (429) 3287 (466) .0001 Gestational age, mean (SD), wk 39.12 (1.20) 39.06 (1.10) .0030

Data Source: South Carolina Office of Research and Statistics; poverty measure is the federal poverty threshold; adequacy of prenatal care based on the Kessner Index.

TABLE 2 Unadjusted Mean Service Use Counts and Unadjusted RRs Comparing Infant Health Care Use for Infants of

Adolescent Mothers (Aged 11–17) and Infants of Older Mothers (Aged 18 – 47): South Carolina Medicaid, 2000 –2002

Outcome Infants of Mothers Aged 11–17,

Mean

Infants of Mothers Agedⱖ18,

Mean

RRa 95% CI

EPSDT visits

Year 1 3.90 3.70 1.05 1.04–1.07

Year 2 1.84 1.74 1.06 1.03–1.08

Sick-infant doctor visits

Year 1 1.93 1.84 1.05 0.99–1.11

Year 2 1.66 1.71 0.97 0.91–1.03

ED visits

Year 1 1.71 1.26 1.36 1.30–1.41

Year 2 1.42 1.07 1.33 1.27–1.38

Hospital admissions

Year 1 1.39 1.18 1.17 1.11–1.25

Year 2 0.70 0.64 1.09 1.01–1.17

ACSC ED visits

Year 1 0.85 0.63 1.34 1.28–1.41

Year 2 0.75 0.56 1.34 1.27–1.41

ACSC hospital admissions

Year 1 0.07 0.06 1.20 1.03–1.40

Year 2 0.07 0.05 1.24 1.05–1.46

Data Source: South Carolina Office of Research and Statistics; sample size for infants of adoles-cent mothers⫽3920; sample size for infants of adult mothers⫽37 776.

aThe RR is the ratio of the mean value for each age group for each outcome, where the rate for

[95% CI: 1.03–1.57]). Adjusted for both infant/delivery and mothers’ characteristics (model 3), results again sug-gested modestly greater use of sick-infant doctor visits in year 1 for infants of adolescents (RR: 1.08 [95% CI: 1.00 –1.17]) and also more hospital admissions in year 1 (RR: 1.09 [95% CI: 1.01–1.18]), as well as notably higher rates of hospitalization for ACSCs in year 1 (RR: 1.29 [95% CI: 1.04 –1.60]).

DISCUSSION

This study compared health care use by infants of ado-lescent mothers with that by infants of older mothers. Consistent with previous research, our expectation is that use of these services is an indicator both of infant health and of mothers’ ability to promote infant health and use health care appropriately. Unadjusted results suggested a number of differences in health care use between infants of younger and older mothers. Most of these differences persisted after adjustment for charac-teristics of infants and deliveries; however, most of these differences did not persist after adjustments either for maternal characteristics only or for both infant/delivery and maternal characteristics. Holding all else constant, for both years 1 and 2, there were no differences in EPSDT visits, ED visits, or ED visits for ACSCs. Moreover, again holding all else constant, there were no differences in year 2 in the number of sick-infant doctor visits, the number of hospital admissions, and the number of hos-pitalizations for ACSCs. There was modestly greater use by infants of adolescents of sick-infant doctor visits and hospital admissions in year 1. The only large significant

adjusted difference among the outcome variables was for hospitalization for ACSCs in year 1, for which infants of adolescent mothers were at higher risk. Considered to-gether, these findings are consistent with our hypothe-sis, suggesting similar health status and patterns of health care use for infants of adolescent and older moth-ers, particularly after adjusting for individual-level char-acteristics of mothers. Furthermore, the proportion of infants who received the AAP-recommended number of EPSDT visits in both years 1 and 2 was the same for infants of adolescent and older mothers, and the ad-justed results also suggested no difference between these groups for EPSDT visits. These findings support the hy-pothesis that adolescent mothers generally provide for needed infant care as well as older mothers who other-wise share similar characteristics.

Several factors should be considered when evaluating these results. The analysis required a successful linkage of health care use data from Medicaid and birth certifi-cates. This linkage could not be made for 6% of the infants covered by Medicaid during the study years. There were no meaningful differences in the character-istics of infants whose data could be linked and those whose data could not.

Most infants who were insured by Medicaid during the study years were enrolled in FFS. They were auto-matically enrolled in FFS unless the parent or guardian elected to enroll in managed care. In other states, infants who are covered by Medicaid are much more commonly enrolled in managed care. In previous research, we ex-tensively analyzed the characteristics of infants who

TABLE 3 Adjusted RRs Comparing Infant Health Care Use for Infants of Adolescent Mothers (Aged 11– 17) and Infants of Older Mothers (Aged 18 – 47): South Carolina Medicaid, Years 2000 –2002

Outcome Model 1 Adjusted for Infant and Delivery

Characteristics

Model 2 Adjusted for Maternal Characteristics

Model 3 Adjusted for Infant and Maternal

Characteristics

RRa 95% CI RRa 95% CI RRa 95% CI

EPSDT visits

Year 1 1.05 1.03–1.07 0.98 0.96–1.00 0.98 0.96–1.00

Year 2 1.05 1.03–1.08 0.98 0.95–1.02 0.98 0.95–1.01

Sick-infant doctor visits

Year 1 1.06 1.00–1.12 1.07 1.00–1.06 1.08 1.00–1.17

Year 2 0.98 0.92–1.04 1.04 0.96–1.13 1.04 0.96–1.12

ED visits

Year 1 1.34 1.29–1.40 0.99 0.94–1.05 1.00 0.94–1.05

Year 2 1.32 1.26–1.37 1.00 0.95–1.06 1.01 0.96–1.07

Hospital admissions

Year 1 1.17 1.10–1.25 1.09 1.01–1.18 1.09 1.00–1.18

Year 2 1.08 1.00–1.16 1.00 0.91–1.10 0.98 0.89–1.08

ACSC ER visits

Year 1 1.33 1.27–1.40 0.99 0.93–1.06 1.00 0.94–1.08

Year 2 1.33 1.26–1.40 1.00 0.93–1.07 1.00 0.94–1.08

ACSC hospital admissions

Year 1 1.19 1.02–1.39 1.27 1.03–1.57 1.29 1.04–1.60

Year 2 1.24 1.05–1.47 1.18 0.93–1.49 1.19 0.94–1.50

Data Source: South Carolina Office of Research and Statistics; sample size for infants of adolescent mothers⫽3920; sample size for infants of adult mothers⫽37 776.

aThe adjusted RR is the ratio of the mean value for each age group for each outcome, where the rate for infants of adolescent mothers is the

were insured by FFS and managed care in the South Carolina Medicaid system, finding few systematic differ-ences between those in FFS and the state’s 2 managed care programs,23although those in FFS were less likely to

have adequate prenatal care than those in managed care. Results of this study may not be generalizable to infants who are insured by Medicaid managed care.

It was desirable to control for infants’ conditions that might especially predispose them to use the health care services that we examined. Thus, infants with congenital conditions or low birth weight and/or preterm infants were excluded from the analysis, and control subjects were included in the models for other characteristics of infants and their deliveries. Inferences from the results should not be extended to infants in the excluded cate-gories. Also controlled were characteristics of the moth-ers that may confound the relationship between mater-nal age and infant outcomes, such as education, income, and marital status. Unmeasured selection factors may nonetheless bias the results.

Furthermore, our controls for maternal use of alco-hol, tobacco, or illicit drugs during pregnancy relied on birth certificate data, which originate from mothers’ reports. Available studies suggested that women self-report smoking during pregnancy with reasonable accu-racy.40,41 There is no accepted biological marker for

diagnosing long-term ethanol exposure in utero,42

al-though studies that used available biological markers for ethanol exposure, such as fatty acid ethyl esters, sug-gested little correlation between maternal self-reporting of ethanol use during pregnancy and the presence of this marker.41 Thus, although available data provide mixed

results, relying on maternal self-reports of substance use during pregnancy may introduce bias associated with measurement error.

It should be noted that the large number of compar-isons shown in Table 1 may have given rise to type 1 error for some comparisons, particularly those for which the associatedPvalue provides more modest evidence of statistical significance (eg, rural/urban residence). We also note that the large sample studied in this analysis is likely to produce statistically significant differences, in part as a function of sample size alone. For example, illicit drug use differed between adolescent and older mothers (P⬍.0001); however, the difference between the rate for adolescents (2.8%) and the rate for older mothers (2.1%) may not be clinically relevant.

Research has suggested that at hospital discharge, most first-time mothers expect to be the infant’s primary caregiver.17 Nonetheless, whether adolescent mothers

lived with their parents or other potential caregivers may have contributed to the results, potentially influ-encing perceived need for clinical care and its use. To the extent that this is a characteristic limited to adolescent mothering, the results would nonetheless accurately re-flect risks of adolescent mothering; however, the lack of a measure in our data for such living arrangements and their effects on care use, for both adolescent and older mothers, may have resulted in unmeasured confound-ing and potential bias. Also, the income measure that was available for this research provided only limited

information about the level of income. It is possible that alternative measures of income might affect the results. It is also possible that there may be residual confounding associated with the sites at which either adolescents or older mothers received care or with the type of outpa-tient setting. These factors were not controlled in our models. Concern about this potential should be amelio-rated considerably by the likelihood that such factors may be associated with the socioeconomic characteristics for which the models controlled.

The analysis controlled for individual-level measures of infant development, because parental behavior may often be influenced by even minor deviations from ex-pectation.36–38,43–45Researchers have speculated that this

effect may cross all levels of socioeconomic status,46

al-though there has been little empirical study of this pos-sibility. This effect may differ depending on the type of infant anomaly47 or on family structure or ethnicity.48

Thus, the estimates in this study may be affected by some degree of residual confounding, despite the control for infant characteristics.

CONCLUSIONS

We found that infants of adolescent mothers are more likely than infants of older mothers to use a variety of health care services that suggest poorer health and that a considerable proportion of this greater use seems to be attributable to specific characteristics of mothers, such as socioeconomic characteristics, rather than to some in-ability of adolescents to promote infant health or to use health care appropriately. These results suggest that pol-icies that aim to provide additional social support to adolescent mothers49 or additional financial resources

may be useful ways to improve the health outcomes of infants who are born to younger women. Additional research is needed, however, to identify specific inter-ventions that may improve health outcomes for infants of adolescents.

REFERENCES

1. Knopf D, Gordon TE. Adolescent health. In: Kotch D, ed.

Maternal and Child Health: Programs, Problems, and Policy in Public Health. Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen Publishers; 1997:195–202 2. McIntosh N. Baby of a schoolgirl.Arch Dis Child.1984;59(10):

915–917

3. Scholl TO, Hediger ML, Belsky DH. Prenatal care and maternal health during adolescent pregnancy: a review and meta-analysis.J Adolesc Health.1994;15(6):444 – 456

4. Isberner F, Wright WR. Comprehensive prenatal care for preg-nant teens.J Sch Health.1987;57(7):288 –292

5. Dott AB, Fort AT. Medical and social factors affecting early teenage pregnancy: literature review and summary of the find-ings of the Louisiana Infant Mortality Study.Am J Obstet Gy-necol.1976;124(4):532–536

6. Erkan KA, Rimer BA, Stine OL. Juvenile pregnancy: role of physiologic maturity.Md State Med J.1971;20(3):50 –52 7. Jolly MC, Sebire N, Harris J, Robinson S, Regan L. Obstetric

risks in women less than 18 years old.Obstet Gynecol. 2000; 96(6):962–966

9. Geronimus AT. On teenage childbearing and neonatal mortal-ity in the United States.Popul Dev Rev.1987;13(2):54 – 61 10. Makinson C. The health consequences of teenage fertility.Fam

Plann Perspect.1985;17(3):132–139

11. Stevens-Simon C, Kelly LS, Singer D. Pattern of prenatal care and infant immunization status in the comprehensive adoles-cent-oriented maternity program. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med.

1996;150(8):829 – 833

12. Koniak-Griffin D, Verzemnieks IL, Anderson NL, et al. Nurse visitation for adolescent mothers: two-year infant health and maternal outcomes.Nurs Res.2003;52(2):127–136

13. Kelly LE. Adolescent mothers: what factors relate to level of preventive health care sought for their infants.J Pediatr Nurs.

1995;10(2):105–113

14. Smolen PL, Miller C, O’Neal R, Lawless MR. Health problems during the first year of life in infants born to adolescent moth-ers.South Med J.1984;77(1):17–20

15. Baldwin W, Cain VS. The children of teenage parents. Fam Plann Perspect.1980;12(1):34 –39

16. Blum RW, Goldhagen J. Teenage pregnancy in perspective.

Clin Pediatr (Phila).1981;20(5):335–340

17. Bagge MJ, Roberts JE, Norr KF. A comparative study of plans for infant care made by adolescent and adult mothers.J Adolesc Health Care.1989;10(6):537–540

18. Dibble JC. ABC for teens: parent education after the baby comes.Pediatr Nurs.1981;7(4):21–23

19. McCarthy J, Hardy J. Age at first birth. J Res Adolesc.1993; 3(Aug):373–392

20. Starfield B. Child health care and social factors: poverty, class, race.Bull N Y Acad Med.1989;65(3):299 –306

21. Laditka SB, Laditka JN, Probst JC. Racial and ethnic disparities in potentially avoidable delivery complications among preg-nant Medicaid beneficiaries in South Carolina. Matern Child Health J.2006;10(4):339 –350

22. Pittard WB, Laditka JN, Laditka SB. Associations between Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment and infant health outcomes among Medicaid-insured infants in South Carolina.J Pediatr.2007;151(4):414 – 418

23. Pittard WB 3rd, Laditka SB, Laditka JN, Xirasagar S, Lovelace OF Jr. Infant health outcomes differ notably among Medicaid insurance models: evidence of a successful case management program in South Carolina. J S C Med Assoc. 2007;103(8): 188 –193

24. Pittard WB, Laditka JN, Laditka SB, Xirasagar S. Infant health care costs for Medicaid-insured infants in South Carolina en-rolled in three insurance plans from birth to 24 months.J S C Med Assoc.2007;103(7):234 –237

25. Alexander GR, Himes JH, Kaufman RB, Mor J, Kogan M. A United States national reference for fetal growth.Obstet Gynecol.

1996;87(2):163–168

26. Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Sutton PD; Centers for Disease Con-trol and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Births: preliminary data for 2003. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2004; 53(9):1–17

27. Falik M, Needleman J, Wells BL, Korb J. Ambulatory care sensitive hospitalizations and emergency visits: experiences of Medicaid patients using federally qualified health centers.Med Care.2001;39(6):551–561

28. Rosenbaum S. Medicaid.N Engl J Med.2002;346(8):635– 640 29. Iglehart JK. The American health care system: Medicaid.

N Engl J Med.1999;340(5):403– 408

30. Rosenbach M, Gavin NI. Early and Periodic Screening,

Diag-nosis, and Treatment and managed care. Annu Rev Public Health.1998;19:507–525

31. Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine. Recommen-dations for Preventive Pediatric Health Care: States Congress Commit-tee on Energy and Commerce, SubcommitCommit-tee on Health and Environ-ment. Healthy Children: Investing in the Future. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 1988

32. Gavin NI, Adams EK, Herz J. The use of EPSDT and other health care services by children enrolled in Medicaid: the im-pact of OBRA ’89.Milbank Q.1998;76(2):207–232

33. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. HCPCS release and code sets. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/HCPCSReleaseCode Sets/ANHCPCS/list.asp. Accessed December 15, 2007

34. Kessner D.Infant Death: An Analysis by Maternal Risk and Health Care. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine and National Academy of Sciences; 1973:50 – 65

35. Kotelchuck M. An evaluation of the Kessner Adequacy of Prenatal Care Index and a proposed Adequacy of Prenatal Care Utilization Index.Am J Public Health.1994;84(9):1414 –1420 36. Klaus MH, Kennell JH. Care of the parents. In Klaus MH,

Fanaroff AA, eds.Care of the High Risk Neonate.Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 2001:189 –211

37. Siegel E, Bauman KE, Schaefer ES, Saunders MM, Ingram DD. Hospital and home support during infancy: impact on maternal attachment, child abuse, and neglect, and health care utiliza-tion.Pediatrics.1980;66(2):183–190

38. Solnit AJ, Stark M. Mourning and the birth of a defective child.

Psychoanal Study Child.1961;16:523–537

39. Ver Hoef JM, Boveng PL. Quasi-poisson vs negative binomial regression: how should we model overdispersed count data?

Ecology.2007;88(11):2766 –2772

40. Klebanoff MA, Levine RJ, Clemmens JD, et al. Serum cotinine concentration and self-reported smoking during pregnancy.

Am J Epidemiol.1998;148(3):259 –262

41. Derauf C, Katz AR, Easa D. Agreement between maternal self reported ethanol intake and tobacco use during pregnancy and meconium assays for fatty acid ethyl esters and cotinine.Am J Epidemiol.2003;158(7):705–709

42. Musshoff F, Daldrup T. Determination of biological markers for alcohol abuse. J Chromatogr B Biomed Sci Appl.1998;713(1): 245–264

43. Landsman GH. Reconstructing motherhood in the age of “per-fect” babies: mothers of infants and toddlers with disabilities.

Signs.1998;24(1):69 –99

44. Singer GHS, Powers LE, eds. Families, Disabilities, and Empowerment: Active Coping Skills and Strategies for Family Interven-tions. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes; 1993

45. Tunali B, Power T. Creating satisfaction: a psychological per-spective on stress and coping in families of handicapped chil-dren.J Child Psychol Psychiatry.1993;34(6):945–957

46. Bellew M, Kay SP. Early parental experiences of obstetric brachial plexus palsy.J Hand Surg [Br].2003;28(4):339 –346 47. Hodapp RM, Dykens EM, Evans DW, Merighi JR. Maternal

emotional reactions to young children with different types of handicaps.J Dev Behav Pediatr.1992;13(2):118 –123

48. Ferguson PM. A place in the family: an historical interpretation of research on parental reactions to having a child with a disability.J Spec Educ.2002;36(3):124 –130

49. Norbeck JS, Dejoseph JF, Smith RT. A randomized trial of an empirically-derived social support intervention to prevent low birthweight among African American women. Soc Sci Med.

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2007-1314

2008;122;e100

Pediatrics

William B. Pittard III, James N. Laditka and Sarah B. Laditka

Factors

Socioeconomic

Medicaid-Insured Infants in South Carolina: Mediating Effects of

Associations Between Maternal Age and Infant Health Outcomes Among

Services

Updated Information &

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/122/1/e100

including high resolution figures, can be found at:

References

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/122/1/e100#BIBL

This article cites 43 articles, 2 of which you can access for free at:

Subspecialty Collections

vices_sub

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/community_health_ser

Community Health Services

_sub

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/community_pediatrics

Community Pediatrics

following collection(s):

This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

Permissions & Licensing

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml

in its entirety can be found online at:

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

Reprints

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2007-1314

2008;122;e100

Pediatrics

William B. Pittard III, James N. Laditka and Sarah B. Laditka

Factors

Socioeconomic

Medicaid-Insured Infants in South Carolina: Mediating Effects of

Associations Between Maternal Age and Infant Health Outcomes Among

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/122/1/e100

located on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 1073-0397.