Femoropatellar Ligament for Canine

Medial Patellar Luxation

Five dogs of varying breeds and ages were presented for evaluation of medial patellar luxation

that was unresponsive to conservative treatment. Arthroscopy of each affected stifle was

per-formed, and adequacy of the femoral trochlea and patellar tracking in the trochlea were

assessed. Medial femoropatellar ligament release was then performed using a bipolar

radiofre-quency electrosurgical system with or without a tibial tuberosity transposition. The procedure

resulted in good to excellent outcomes for four dogs and a fair outcome for a fifth dog.

J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2004;40:321-330.John M. Bevan, DVM Robert A. Taylor, DVM, MS, Diplomate ACVS

Introduction

Patellar luxation is a disease in which the patella deviates medially or lat-erally from its normal tracking position within the femoral trochlea. Medial patellar luxation occurs more commonly than lateral luxation in the dog, but both have been associated with direct trauma or congenital musculoskeletal abnormalities. Patellar luxation is a common orthopedic disease in the dog and has been reported in cats.1Similar patellar disease

has also been reported in humans.2-7

Patellar luxation is often a congenital, bilateral disease and is com-monly found in female, small-breed dogs.8Clinical signs are variable but

usually include chronic, intermittent, weight-bearing pelvic-limb lame-ness. Ultimately, the severity of the disease is related to the degree of lux-ation; thus, a generalized grading system has been developed for classification of canine patellar luxations [Table 1].9-12Diagnosis is based

on signalment, history, physical examination findings, and radiography. Standard and specialized radiographic views of the stifle help to confirm the luxation and often reveal both degenerative joint disease (DJD) and anatomical abnormalities of the trochlea, distal femur, and proximal tibia. Differential diagnoses for patellar luxation include soft-tissue injury of the stifle (e.g., cruciate ligament, collateral ligament, meniscal, or joint cap-sule injury), osteochondritis dessicans, and muscle strain.13

The patella is the largest sesamoid bone in the dog and acts as a lever arm to alter the direction of pull of the quadriceps muscles, thereby decreasing the amount of force required to extend the stifle joint. The extensor mechanism of the pelvic limb is composed of the quadriceps muscles, the patella, the femoral trochlea, the patellar ligament, and the tibial tuberosity. Any abnormality of one or more of these components can predispose the patella to medial or lateral luxation. The patella is supported and maintained in appropriate articulation with the femoral trochlea by the medial and lateral trochlear ridges, the joint capsule and associated femoral fascia, the parapatellar fibrocartilages, and the femoropatellar ligaments. The medial and lateral parapatellar fibrocarti-lages help support the patella by extending from either side of the patella

CS

JOURNAL of the American Animal Hospital Association 321

From the Alameda East Veterinary Hospital, 9870 East Alameda Avenue, Denver, Colorado 80247.

into the adjacent femoral fascia.14The femoropatellar

liga-ments are bands of loose connective tissue that connect the patella to the fabella laterally and to the periosteum of the femoral epicondyle medially.14

The majority of animals with patellar luxation have some degree of structural deformity of the pelvic limb, ranging from soft-tissue changes to marked skeletal abnormalities. The abnormalities associated with medial patellar luxation include coxa vara, medial displacement of the quadriceps muscles, lateral torsion and/or lateral bowing of the distal femur, femoral epiphyseal dysplasia (i.e., shallow trochlea, hypoplastic medial trochlear ridge), medial bowing of the proximal tibia, and internal rotation of the distal tibia.12,15,16 Different theories exist about the origin and

progression of these developmental changes, and the causal relationship between patellar luxation and these abnormali-ties has yet to be determined.15,16Despite the origin of these

changes, the final result is malalignment of the extensor mechanism, which places abnormal forces on the patella, predisposing it to luxation.

A thorough understanding of these underlying abnormali-ties is very important to properly manage the disease. Conventional surgical options are categorized into joint stabi-lization (e.g., medial release and lateral imbrication of the joint capsule) and reconstruction (e.g., trochleoplasty, tibial tuberosity transposition, and femoral/tibial osteotomies) tech-niques.12,15,17These options, often used in combination, have

been successful, because the goal of treatment is correction of the luxation in conjunction with neutralization of mechanical forces caused by underlying structural abnormalities. Typically, conventional techniques provide a good to excel-lent prognosis, and treatment recommendations have been suggested for each grade of luxation [Table 2].9,10,12,16,18

In general, the decision to surgically treat a Grade I medial patellar luxation is reserved for symptomatic cases, and treatment of dogs with a Grade II medial patellar luxation is usually recommended if lameness is frequent and persist-ent. The benefits of early surgical correction include resolu-tion of the clinical signs; cessaresolu-tion of progression of cartilage erosion of the medial trochlear ridge and the artic-ular surface of the patella secondary to patellar luxation; and prevention of rupture of the cranial cruciate ligament that

may occur in middle-aged and older dogs with chronic patellar luxation.18Treatment of young, asymptomatic dogs

with patellar luxation has also been recommended to pre-vent abnormal physeal development and subsequent skele-tal abnormalities.12,13,16The purpose of this study was to

investigate the effectiveness of arthroscopic release of the medial femoropatellar ligament in conjunction with a tibial tuberosity transposition for management of Grade I or II medial patellar luxations.

Materials and Methods

The diagnosis of medial patellar luxation was made based on physical examination findings and radiography. Each affect-ed stifle was assignaffect-ed a luxation grade, and the animal was considered a surgical candidate if a Grade I or II medial patellar luxation was diagnosed as the only cause of lame-ness; if clinical signs persisted despite conservative therapy (i.e., restricted exercise and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug [NSAID] therapy); and if radiographic and arthroscop-ic findings confirmed trochlea adequacy and minimal carti-lage wear of the patella and the medial trochlear ridge.

Preanesthetic medications included glycopyrrolate (0.01 mg/kg intramuscularly [IM]), acepromazine (0.02 mg/kg IM), and morphine (1.0 mg/kg IM). Anesthesia was induced with propofol (4.0 to 6.0 mg/kg intravenously [IV] slowly to effect) and was maintained with isoflurane. Morphine (0.3 to 0.5 mg/kg IM q 4 to 6 hours) was given postoperatively for pain management. Preoperative axial radiography of the stifle in flexion was performed to help assess the depth and adequacy of the femoral trochlea [Figure 1].

The affected stifle was clipped and surgically prepared. A 2.7-mm arthroscopeawas introduced through a cannula

in the standard cranial lateral arthroscopic portal (lateral to the edge of the patellar ligament and just proximal to the proximal surface of the tibia near an unnamed bony protu-berance, commonly referred to as Gerdy’s tubercle).19A

fluid pump system was attached to the scope cannula, and sterile lactated Ringer’s solution was infused into the joint space to aid visualization. A 2.9-mm egress cannulabwas

introduced into the medial joint pouch through a proximal medial portal located just proximal and medial to the patella.19A thorough examination of the stifle joint was

performed, including examination of the trochlea and

Table 1

Grades of Severity of Canine Patellar Luxation

Grade I Patella luxates with manual pressure, and luxation spontaneously resolves with release of the pressure. Grade II Patellar luxation occurs frequently during stifle flexion or with manual pressure. The patella remains

luxated but reduces with manual pressure.

Grade III The patella is permanently luxated, but temporary manual reduction is still possible. Grade IV The patella is permanently luxated and cannot be manually reduced.

assessment of patellar tracking in the trochlea through a full range of motion.

A bipolar radiofrequency electrosurgical systemc was

introduced into the joint through a 2.9-mm cannula via a cra-nial medial portal (same level as the lateral portal but at the medial edge of the patellar ligament).19 The standardized

default settings of the radiofrequency unit for each particular

probe were used. Adequate joint capsule distension was achieved by increasing the fluid rate to provide an approxi-mate pressure of 80 mm Hg to facilitate release of the medi-al femoropatellar ligament. Following distension of the joint capsule, the fibrous bands of the medial femoropatellar liga-ment were visualized. The bipolar radiofrequency probe with a hook tip was used to sever the ligament and adjacent joint capsule and femoral fascia in a slow, continuous, sweeping arc motion [Video 1; legend on next page]. The incision was made just medial and parallel to the patella, extending from the distal pole of the patella to just proximal to the proximal pole of the patella, as dictated by the physi-cal limitations of the arthroscopy unit. Arthroscopic visuali-zation and probing of the tissues assisted in determining the adequacy of the incision (i.e., fluid extravasation into the subcutaneous tissue) and avoiding damage to the medial parapatellar fibrocartilage. When using the radiofrequency unit, a high fluid flow rate (approximately 100 to 120 mL per minute) was used to help dissipate the heat generated by the unit and protect any surrounding cartilage.

If thermal shrinkage of the lateral joint capsule was per-formed (as in case no. 3), the scope was reintroduced into the joint via the medial portal, and the radiofrequency unit was introduced into the lateral portal. The bipolar radiofre-quency probe was used in a unidirectional sweeping man-ner over the inman-ner aspect of the lateral joint capsule to cause lateral capsular shrinkage [Videos 2, 3; legends on next page]. The surgeon relied on visual assessment of the mor-phological tissue changes (e.g., darkening, roughening, and contraction of the treated joint capsule) and capsular vol-ume reduction to quantify the degree of capsular shrinkage. The patella was again observed tracking in the trochlea through a full range of motion. The bipolar radiofrequency system, instrument cannula, egress cannula, and scope were removed, and 1.0 mL of bupivacainedwas injected into the

joint. If needed, a tibial tuberosity transposition was accom-plished via a small incision made medially to the tibial crest. The osteotomized tibial tuberosity was reattached laterally

Figure 1—Technique for acquiring an axial view of the sti-fle with the central radiographic beam imaging the relation-ship between the patella and femoral trochlea. The views were obtained with the dog in dorsal recumbency, with the stifle in approximately 90˚ of flexion or more. The film was held distal to the stifle and perpendicular to the central beam to avoid distortion of the image. The angle of the central beam and stifle flexion were adjusted to obtain the most appropriate image.

Table 2

Recommended Treatments for Canine Patellar Luxations

Grade I Soft-tissue stabilization (minimal lateral imbrication and medial desmotomy) or no treatment if the dog is asymptomatic

Grade II Soft-tissue stabilization and tibial tuberosity transposition

Grade III Soft-tissue stabilization, tibial tuberosity transposition, and trochleoplasty

Grade IV Soft-tissue stabilization, tibial tuberosity transposition, trochleoplasty, and possible femoral and/or tibial osteotomy

in a position to achieve femoropatellar axis neutrality with multiple Kirschner wires or Steinmann pins.13,16,17If

per-formed, a tension band fixation was completed using ortho-pedic wire. The subcutaneous tissue was closed with 3-0 polydioxanoneein a simple continuous pattern, and the skin

incisions were closed with sterile skin staples.f

A soft-padded bandage was applied to the affected stifle for 24 to 48 hours postoperatively, depending on the degree of fluid extravasation. Each animal was discharged on oral NSAID therapy. Home care instructions prohibited running, jumping, and all off-leash activities. Application of ice packs to the area was advised for 10 to 15 minutes three to four times a day for 1 week, and crate rest was recommend-ed when the dog was left alone. Short, controllrecommend-ed leash walks were allowed for 10 to 15 minutes two to three times a day for 4 to 6 weeks.

All dogs were reevaluated 10 days postoperatively for sta-ple removal. Tracking of the patella was palpated, and mod-est attempts to manually induce patellar luxation were made. Assessment of the surgical site and evaluation of the gait at a walk were also performed. Follow-up evaluations occurred initially at approximately 1 and 2 months postoperatively. The dog’s gait was evaluated at a walk and a trot, and modest attempts to luxate the patella were made. The affected stifle joint was evaluated for effusion and pain, and patellar track-ing was assessed through a full range of motion. Standard radiographic views of each treated stifle were obtained to assess healing of the tibial tuberosity (if performed) and to monitor for evidence of DJD and stifle effusion. As previous-ly described, axial radiography of the affected stifle was also performed to evaluate the position of the patella and the ade-quacy of trochlear depth. Fluoroscopygof the stifle was

per-formed to assess patellar tracking along the trochlea and patellar stability through an almost full range of motion. The fluoroscopy was performed using a similar technique to that described for axial radiography.

Any postoperative lameness was assigned a Grade of 0, I, II, III, or IV, based on the following definitions: Grade 0 was a normal stance (full weight bearing) and no apparent lameness at a walk or trot; Grade I was a slightly abnormal

stance (partial weight bearing) with lameness, but weight bearing on >95% of strides at a walk and trot; Grade II was a moderately abnormal stance (toe-touch weight bearing) and lameness, with weight bearing on >50% and <95% of strides at a walk and trot; Grade III was a severely abnormal stance (dog holds limb off the floor) and lameness, with weight bearing on >5% and <50% of strides at a walk and trot; Grade IV was the inability to stand on the affected limb and nonweight-bearing lameness or weight bearing on <5% of strides at a walk and trot.hThe overall results of each case

were assigned a rating of excellent, good, fair, or poor. “Excellent” was defined as a normal gait, normal limb func-tion, no patellar luxafunc-tion, and normal patellar tracking through a full range of motion. “Good” was defined as a normal gait, normal limb function, normal patellar tracking, and patellar luxation occurring only with modest manual pressure (not occurring spontaneously) but reducing imme-diately. “Fair” was defined as a mild lameness that improved when compared to the preoperative condition, normal patellar tracking most of the time, and patellar luxa-tion occurring both spontaneously and with manual pres-sure. “Poor” was defined as a marked lameness and a grade of patellar luxation that was worse than before surgery.

Results

Case No. 1

A 2-year-old, 23-kg, spayed female Dalmatian was present-ed for an acute, Grade IV lameness of the left pelvic limb after falling from a porch. Physical examination revealed pain on manipulation of the left stifle joint as well as mild left stifle effusion. A traumatic medial patellar luxation was confirmed with standard radiographic views of the stifle joint. Surgery was recommended, and a tibial tuberosity transposition, trochlear wedge recession, medial desmotomy, and lateral imbrication of the joint capsule were performed.

The animal was reassessed 1 month later. There were no abnormalities of the left pelvic limb, but physical examina-tion revealed a Grade I to II right medial patellar luxaexamina-tion and a Grade I right pelvic-limb lameness. There was no Legends for Video Clips

Video 1—Video clip showing the arthroscopic medial femoropatellar ligament release. A bipolar radiofrequency probe with a hook tip is utilized. The joint capsule is distended prior to the release, and the transverse fibers of the ligament can be easily identified. The release is started just medial and proximal to the patella. It is continued dis-tally in a plane parallel to the longitudinal axis of the patella.

To view video: http://www.jaaha.org/cgi/content/full/40/4/321/DC1

Video 2—Video clip showing thermal shrinkage of the lateral joint capsule. The patella can be visualized on the left side of the screen, and the lateral femoral trochlear ridge can be seen on the right. Thermal capsular shrinkage is achieved by applying the radiofrequency probe to the capsular tissue in multiple, focal areas. Capsular volume reduction can be visualized. To view video: http://www.jaaha.org/cgi/content/full/40/4/321/DC2

Video 3—Video clip showing thermal shrinkage of the lateral joint capsule. A closer view of focal applications of the radiofrequency probe to the lateral joint capsule is shown. The morphological changes and volume reduction of the capsular tissue are easily identified following each application. The lateral femoral trochlear ridge can be visualized at the bottom of the screen. The patella comes into view on the right side of the screen at the end of the clip. To view video: http://www.jaaha.org/cgi/content/full/40/4/321/DC3

radiographic evidence of effusion or DJD in the right stifle. A medial femoropatellar ligament release and a tibial tuberosity transposition, using three 0.062-inch Kirschner wires, were performed on the right stifle. Mild fluid extrava-sation from the medial aspect of the stifle occurred postop-eratively but resolved spontaneously within 1 to 2 days. The dog was evaluated at 10 days, 1 month, 5 months, and 17 months postoperatively [Table 3]. Physical examination revealed luxation of the right patella medially with signifi-cant manual pressure, with spontaneous reduction occurring immediately (Grade I luxation). Patellar tracking and the gait at the walk and the trot were both normal.

Upon reexamination at 17 months, there was no radio-graphic evidence of stifle effusion or DJD, and the tibial tuberosity was healed. On fluoroscopy of the stifle, trochlear depth appeared adequate, and there was no evi-dence of patellar luxation or subluxation unless significant manual pressure was applied to the patella. Further treat-ment was not recommended, and the overall outcome was rated as “good.”

Case No. 2

A 1-year-old, 25-kg, male neutered mixed-breed dog was presented for a right pelvic-limb lameness of 1-month duration. Physical examination revealed a Grade II right lameness, a Grade II right medial patellar luxation, a pos-itive Ortolani sign of the right coxofemoral joint, and a Grade I left medial patellar luxation. Radiographic find-ings of both stifles included mild effusion and the presence of small osteophytes on the periarticular surfaces. Axial radio-graphic views revealed normal patellar positioning and adequate trochlear depth. A medial femoropatellar lig-ament release and a tibial tuberosity transposition, using two 3/32-inch Steinmann pins, were performed on the right stifle.

Two months later, examination revealed a Grade I lame-ness of the left hind leg. A medial femoropatellar ligament release and a tibial tuberosity transposition, using two 0.062-inch Kirschner wires, were performed on the left sti-fle. Mild fluid extravasation from the medial aspect of each stifle occurred postoperatively but resolved spontaneously within 1 to 2 days. The only abnormality noted on physical examination of each limb at the respective 10-day, 1-month, and 2-month postoperative examinations was a Grade I lameness of the left pelvic limb at the 10-day examination [Table 3]. At the 2-month postoperative examination for the left limb (4 months postoperative for the right limb), no sig-nificant radiographic abnormalities of either stifle were found, and return to normal activity was recommended.

Five months later, the only abnormality reported by the owner was abduction of the right pelvic limb while the ani-mal was in a sitting position and intermittent pelvic-limb skipping (i.e., holding the limb in a flexed position for one to two strides and then returning to a normal gait). Physical examination revealed no lameness at a walk, a Grade III left medial patellar luxation, a Grade II right medial patellar luxation, and no significant pain on palpation of either

sti-fle. Radiographs of the right stifle revealed mild DJD simi-lar to that seen preoperatively. Radiographs of the left stifle revealed a tibial tuberosity avulsion and patella alta. Fluoroscopy of the right stifle revealed adequate trochlear depth and no evidence of patellar luxation or subluxation through an almost full range of motion. Fluoroscopy of the left stifle revealed inadequate trochlear depth, medial patel-lar luxation throughout the full range of motion, and patella alta, but no apparent movement of the tibial tuberosity. The overall outcome was rated as “fair” for the right pelvic limb and “poor” for the left pelvic limb.

Case No. 3

A 16-month-old, 32-kg, spayed female golden retriever was presented for a Grade II right pelvic-limb lameness. Physical examination revealed a Grade II medial patellar luxation. There was no radiographic evidence of effusion or DJD. A medial femoropatellar ligament release and a tibial tuberosi-ty transposition, using two 3/32-inch Steinmann pins, were performed with the addition of thermal shrinkage of the lat-eral joint capsule. The bipolar radiofrequency probe was used as previously described in a unidirectional sweeping manner over the inner aspect of the lateral joint capsule. The result was visible shrinkage of the capsule, leading to imbri-cation of the lateral soft-tissue supporting structures.

Upon reexamination postoperatively, no lameness (Grade 0 lameness) or patellar luxation was detected [Table 3]. Mild fluid extravasation from the medial aspect of the stifle was present postoperatively, but it resolved spontaneously within 1 to 2 days. Radiographically, no evidence of stifle effusion or DJD was noticed 2 months and 7 months after surgery. At 7 months postoperatively, fluoroscopy indicated that the trochlear depth was adequate, and there was no evidence of patellar luxation or subluxation. The overall outcome was rated as “excellent.”

Case No. 4

A 3-year-old, 18-kg, intact male soft-coated wheaten terrier was presented for an intermittent, left pelvic-limb lameness. Physical examination revealed a Grade I left medial patellar luxation and a Grade II lameness with short, intermittent episodes of nonweight-bearing lameness. Radiography did not reveal significant abnormalities of either the coxo-femoral or stifle joint. Axial radiographic views showed normal patellar positioning and adequate trochlear depth.

The dog remained unresponsive to conservative therapy (i.e., exercise restriction), and a medial femoropatellar liga-ment release was performed 1 month later. Mild fluid extrava-sation from the medial aspect of the stifle occurred postoperatively, but it resolved spontaneously within 1 to 2 days. At suture removal 10 days later, no significant abnor-malities were noted [Table 3]. On reexamination 3 weeks later, modest manual pressure did not luxate the patella, and no lameness (Grade 0 lameness) was observed at a walk. However, intermittent episodes of a toe-touching lameness of the left pelvic limb were observed at a trot. Physical therapy was performed, including underwater treadmill exercises and

T

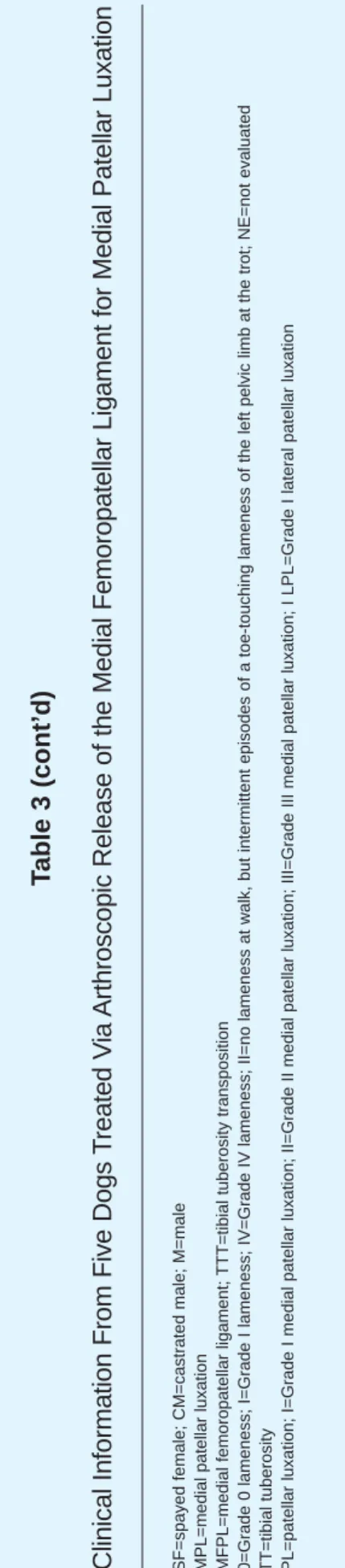

able 3

Clinical Information From Five Dogs

T

reated V

ia

Arthroscopic Release of the Medial Femoropatellar Ligament for Medial Patellar

Luxation Case Clinical Post-op Patellar Final No. Signalment * Findings † Surgery ‡ T ime W alk § T rot § Complications \ PL ¶ T racking Outcome 1 2-y-old, 23-kg,

Right Grade I-II

MFPL release 10 d 0 NE None None Normal Good SF Dalmatian MPL and and TTT 1 mo 0 0 I Normal Grade I 5 mo 0 0 I Normal lameness 17 mo 0 0 I Normal 2 1-y-old, 25-kg, Right Grade II MFPL release 10 d 0 0 None None Normal Fair CM, mixed-breed MPL and and TTT 1 mo 0 0 None Normal dog Grade II 2 mo 0 0 None Normal lameness 9 mo 0 N E II Normal Left Grade I Staged MFPL 10 d I 0 None Normal Poor MPL and release 1 mo 0 0 None Normal Grade I and TTT 2 mo 0 0 None Normal lameness 7 mo 0 N E Left TT avulsion III Permanent luxation 3 16-mo-old, Right Grade II MFPL release, 10 d 0 0 None None Normal Excellent 32-kg, SF golden MPL and lateral joint 1 mo 0 0 None Normal retriever Grade II capsule 2 mo 0 0 None Normal lameness shrinkage, 7 mo 0 0 None Normal and TTT 4 3-y-old, 18-kg, Left Grade I MFPL release 10 d 0 NE None None Normal Good-M soft-coated MPL and 1 mo 0 II None Normal Excellent wheaten terrier Grade II 3 mo 0 0 I LPL Normal lameness 4 mo 0 0 None Normal 5 6-mo-old, 36-kg,

Right Grade II-III

Right MFPL 14 d 0 0 None None Normal Good-CM Labrador MPL and release 6 wks IV NE TT avulsion III Permanent Excellent retriever Grade II and TTT 2 mo I-II NE Partial dehiscence None luxation lameness 3 mo 0 0 None None Normal 17 mo 0 0 None None Normal Left Grade II Not operated MPL

T

able 3 (cont’d)

Clinical Information From Five Dogs

T

reated V

ia

Arthroscopic Release of the Medial Femoropatellar Ligament for Medial Patellar

Luxation

*SF=spayed female; CM=castrated male; M=male †MPL=medial patellar luxation ‡MFPL=medial femoropatellar ligament;

TTT=tibial tuberosity transposition

§0=Grade 0 lameness; I=Grade I lameness; IV=Grade IV lameness; II=no lameness at walk, but intermittent episodes of a toe-touchi

ng lameness of the left pelvic limb at the trot; NE=not evaluated

\TT=tibial tuberosity ¶PL=patellar luxation; I=Grade I medial patellar luxation; II=Grade II medial patellar luxation; III=Grade III medial patellar l

electrical stimulation of the vastus lateralis muscle every 3 to 4 days for 1 month.

Three months postoperatively, no lameness was seen at a walk, but occasional flexing of the limb occurred at a trot. Physical examination with mild sedation (to avoid interfer-ence with pain sensation) revealed a normal range of motion, no pain on palpation of both stifles, and an inability to man-ually luxate the left patella medially. Significant manual pressure was able to luxate the left patella laterally, but the patella would return to its normal position spontaneously.

Approximately 6 weeks later, the dog was reexamined, and at this time the left patella could not be luxated lateral-ly. No evidence of effusion or DJD was seen on radiographs, and fluoroscopy indicated adequate depth to the trochlea and no evidence of patellar luxation or subluxation. The overall outcome was rated as “good-excellent.”

Case No. 5

A 6-month-old, 36.8-kg, neutered male Labrador retriever was presented for a lameness evaluation. Physical examina-tion revealed a Grade II-III right medial patellar luxaexamina-tion, a Grade II right pelvic-limb lameness, a Grade II left medial patellar luxation, and a positive Ortolani sign of the left coxo-femoral joint. Radiographic findings included bilateral medial patellar luxation, bilateral stifle effusion, and mild hip dysplasia. Trochlear depth and patellar positioning appeared adequate on axial radiographic views. The dog did not respond to further exercise restriction.

A right medial femoropatellar ligament release and a tib-ial tuberosity transposition were performed, using two 0.062-inch Kirschner wires and 18-gauge orthopedic wire in a tension band fixation. Mild fluid extravasation from the medial aspect of the stifle occurred postoperatively but resolved spontaneously within 1 to 2 days. At suture removal 2 weeks later, no significant abnormalities were found [Table 3].

The animal was presented 1 month later for evaluation of an acute-onset Grade IV right pelvic-limb lameness. There was a Grade III right medial patellar luxation, and radio-graphs of the right stifle revealed a tibial tuberosity avulsion and a medial patellar luxation. The avulsion was corrected using fluoroscopy to place a tension band fixation using two 0.062-inch Kirschner wires and 18-gauge orthopedic wire. A lateral splint was applied, and the dog was sent home with instructions for owners to provide strict crate rest for 3 to 4 weeks.

The animal was reevaluated 12 days later, after having prematurely removed the splint. Physical examination revealed partial proximal wound dehiscence secondary to self-inflicted trauma. The wound was cultured (no growth occurred after 48 hours), a 10-day course of antibiotics (cephalexin 22 mg/kg per os [PO]) was initiated, and the splint was reapplied. One month later, the pins were removed from the proximal tibia. No lameness (Grade 0 lameness) was evident at a walk or trot, no patella luxation developed, and radiographs revealed adequate healing of the tibial tuberosity and resulting patella alta.

Fourteen months later, no lameness was seen at a walk or trot, no obvious effusion or pain was noticed on palpation of either stifle, and modest attempts to manually luxate the right patella were unsuccessful. The dog was easily restrained for examination, and sedation was not used. Radiographs of the right stifle joint revealed the tibial tuberosity was healed, and there was no evidence of effusion, DJD, or medial patellar luxation. On fluoroscopy, trochlear depth appeared adequate, and no evidence of patellar luxa-tion or subluxaluxa-tion was seen. Fluoroscopy in a lateral view did not reveal movement of the tibial tuberosity, and the patella appeared to be in an anatomically normal position. The overall outcome was rated as “good-excellent.”

Discussion

Treatment of Grade I patellar luxations includes soft-tissue stabilization techniques and is usually restricted to sympto-matic cases. Historically, treatment for Grade II patellar luxa-tions has involved soft-tissue stabilization (e.g., medial desmotomy and lateral joint capsule imbrication) with a tibial tuberosity transposition.9,12,17 Realignment of the extensor

mechanism is the goal of these conventional techniques. The arthroscopic-assisted procedure described in this report pro-vides an alternative means to achieve the same realignment.

Preoperative radiography and direct arthroscopic visual-ization of the stifle joint allow assessment of concurrent anatomical abnormalities (including trochlea adequacy), patellar tracking in the trochlea, the presence or degree of osteoarthritis, the status of the cruciate ligaments and menisci, and the health of the articular cartilage. Arthroscopic transection of the medial femoropatellar liga-ment provides medial release of the patella, and lateral imbrication can be achieved by arthroscopic thermal shrink-age of the lateral joint capsule. With the surgical technique employed in this report, tibial tuberosity transposition is performed as previously described, but without a standard arthrotomy.13Based upon results in the five cases reported

here, the advantages of this procedure included less tissue trauma, a quicker healing time, and a more rapid return to function. However, prospective studies are required to quan-tify and compare postoperative pain and limb functionality in dogs treated with this procedure versus conventional techniques requiring an arthrotomy.

Four of the five cases reported here had a good or excel-lent outcome [Table 3]. In case nos. 3, 4, and 5, the patellar luxation and the associated clinical signs resolved com-pletely. In case no. 1, clinical signs resolved completely, and the grade of the patellar luxation improved. The results of these four cases appear similar to those obtained with con-ventional techniques, but further studies comparing the effi-cacy of conventional surgical techniques to this procedure are warranted.

Clinical signs resolved in case no. 2, but there was wors-ening of the luxation grade of the left pelvic limb and no change in luxation grade of the right pelvic limb. The poor outcome for the left pelvic limb was attributed to the post-operative tibial tuberosity avulsion that caused malalignment

of the quadriceps mechanism. A variety of factors may have contributed to the outcomes for each of the stifles in this case, including inadequate medial femoropatellar ligament release, failure to identify inadequacy of the trochlea, insuf-ficient neutralization of the musculoskeletal deformity with the tibial tuberosity transposition, and failure to imbricate the lateral joint capsule and retinaculum. The results of this case reflect the importance of case selection prior to utiliz-ing this surgical technique.

Although the arthroscopic release of the medial femoropatellar ligament involves transection of the medial joint capsule, the medial femoropatellar ligament release remains less invasive than a standard arthrotomy and medial desmotomy, and it may allow earlier use of the limb postop-eratively. In all five cases reported here, significant use of the operated limb was seen within 4 to 5 days (as reported by the owners), and almost normal use of the limb was observed within 10 days. Although controlled use of the limb postop-eratively is beneficial to strengthen the supporting structures of the patella in its proper alignment, overuse of the limb in the early postoperative period may result in recurrent luxa-tion and complicaluxa-tions associated with the tibial tuberosity transposition. Thus, strict exercise restriction for at least 6 weeks is important to allow adequate healing of the tibial tuberosity and reestablishment of muscle function and sup-port. Physical therapy activities aimed at strengthening the supporting musculature (e.g., electrical stimulation of the vastus lateralis muscle and home exercises to strengthen quadriceps muscles) are strongly recommended for at least 1 month to hasten the development of a stable quadriceps mechanism.

In case nos. 2 and 5, tibial tuberosity avulsion was a post-operative complication. In both cases, the owners reported difficulty restricting the dog’s level of activity during the first 6 weeks postoperatively. Although different procedures were used to stabilize the tuberosity in each of the two cases, the authors are aware that surgical technique may have contributed to the tibial tuberosity avulsions. However, overuse of the limb early in the postoperative period and overbearing forces on the tibial tuberosity may have result-ed in the tibial tuberosity avulsion. Thus, it is the authors’ opinion that conservative, significant postoperative exercise restriction and rehabilitation should be utilized with the pro-cedure described in this study.

A less severe complication found in all five cases was fluid extravasation into the medial subcutaneous tissue of the stifle. During transection of the medial femoropatellar ligament, the underlying joint capsule and femoral fascia were also transected to allow sufficient medial release of the patella, allowing varying amounts of synovial and arthro-scopically infused fluid to extravasate into the subcutaneous tissue. No related complications were observed in the cases of this report, but further studies are required to assess com-plications that may result from this fluid extravasation.

Fluoroscopy and axial radiographic views of the stifle were utilized in this study to evaluate adequacy of trochlear depth and patellar tracking through an almost complete

range of motion of the stifle joint. The authors are unaware of any standardized recommendations for performing and interpreting these diagnostic modalities, so the results should be considered as subjective. As previously described by Merchant, et al., comparative medical imaging modali-ties exist in humans, but further studies in the dog are required to develop a standardized technique for the axial view of the stifle.20A limitation of the axial view is the

inability to evaluate the seating of the patella in the most proximal aspect of the trochlea, where patellar luxation is most likely to occur during extension of the stifle. However, the fluoroscopic and axial radiographic findings in each case were consistent with those found on standard radio-graphic views, arthroscopy, and physical examination. While these specialized imaging techniques helped with postoperative assessments of the surgical procedure, addi-tional studies are required to standardize the techniques.

Electrosurgical (i.e., radiofrequency energy) devices are widely used in human medicine.21 The thermal effect of

radiofrequency energy can be modified to perform a wide range of tasks, from coagulation to cutting.21 Currently,

radiofrequency units are available as monopolar and bipolar devices. The bipolar units have the advantage of increased cutting efficiency and decreased thermal damage to the adjacent tissues. Despite the type of unit used, contact with articular cartilage must be avoided, since both devices have been shown to destroy cartilage cells and underlying sub-chondral bone.22,23

In contrast, the effects of radiofrequency energy on joint capsule tissue have proven to be beneficial. The application of radiofrequency energy to capsular tissue in multiple, sin-gle linear passes causes significant tissue shrinkage related to collagen denaturation and contraction.24-26 Prolonged

application of the radiofrequency energy results in ablation of the tissue, as is the case when performing the described medial femoropatellar ligament release procedure. The prin-ciples, procedures, and equipment used in this study to incise and release the components of the medial supporting structures, as well as to provide thermal shrinkage of the lat-eral joint capsule of the stifle, were similar to those described in humans.

The procedures used in this study have only recently been described in the veterinary literature.19Similar disease

processes and corrective procedures have been well docu-mented in humans.2-7 Recently, techniques utilizing only

arthroscopy have been reported for lateral patellar instabili-ty that involved placement of medial joint capsule sutures and a lateral capsular release using a standard electrosurgi-cal device in people.2-4The majority of people in each study

had minimal anatomical changes and good to excellent results (e.g., significant improvement in pain, swelling, and function).2-4Other studies have shown that young children

with congenital luxation of the patella that were surgically treated with primarily soft-tissue techniques to realign the patella had a good long-term outcome and developed nor-mal femoral trochleae, despite the almost complete absence of a trochlea preoperatively.6,7Similarly, a clinical study in

dogs showed that tibial tuberosity transposition performed before 60 days of age in puppies with medial patellar luxa-tion and associated distal femur abnormalities corrected these abnormalities completely.27 The authors believe

results similar to those found in infants treated with soft-tis-sue techniques to correct patellar luxation may be possible in dogs with medial patellar luxation when treated early in the disease process (<6 to 11 months of age), before radio-graphic closure of the femoral and tibial physes.28

Realignment of the patella with soft-tissue techniques alone may prevent the development of the anatomical abnormali-ties seen with patellar luxation, resulting in an anatomically correct and stable extensor mechanism. The combination of an arthroscopic medial femoropatellar ligament release and lateral joint capsule shrinkage provides a procedure that is minimally invasive and may be appropriately utilized in younger animals to combat the occurrence of these anatom-ical abnormalities and patellar luxation. Unfortunately, the limited number of cases in this report does not allow statis-tically significant conclusions to be drawn. Further studies are warranted to evaluate the use of an entirely arthroscopic procedure (i.e., medial femoropatellar ligament release and lateral joint capsule shrinkage) in the management of Grade I-II patellar luxation in young dogs.

Conclusion

The combination of an arthroscopic medial femoropatellar ligament release and tibial tuberosity transposition with or without thermal shrinkage of the lateral joint capsule appeared to be a viable treatment option in dogs with Grade I or II medial patellar luxation. Although the limited num-ber of cases did not allow statistical analysis, four of the five cases had good to excellent outcomes. These results were consistent with conventional surgical techniques. A well-designed prospective study is warranted to compare the morbidity and efficacy of this procedure with those of con-ventional surgical techniques.

a 2.7-mm 30˚ arthroscope; Smith and Nephew, Andover, MA b 2.9-mm cannula with flow port; Smith and Nephew, Andover, MA c VARP II; Mitek Products, Westwood, MA

d Bupivacaine; Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, IL e PDS-II; Ethicon, Inc., Sommerville, NJ

f Royal 35W; United States Surgical Corporation, Norwalk, CT g XISCAN 1000; Xitec, Inc., Windsor Locks, CA

h Personal communication with Carrie Adamson, MSPT, CCRP

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Dr. Jennifer Warnock for providing the illustration.

References

11. Umphlet RC. Feline stifle disease. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim

Pract 1993;23:897-913.

12. Halbrecht JL. Arthroscopic patella realignment: an all-inside

tech-nique. Arthroscopy 2001;17:940-945.

13. Ahmad CS, Lee FY. An all-arthroscopic soft-tissue balancing

tech-nique for lateral patellar instability. Arthroscopy 2001;17:555-557.

14. Haspl M, Cicak N, Klobucar H, et al. Fully arthroscopic stabilization

of the patella. Arthroscopy 2002;18:E2.

15. Eilert RE. Congenital dislocation of the patella. Clin Orthop

2001;389:22-29.

16. Ghanem I, Wattincourt L, Seringe R. Congenital dislocation of the

patella part I: pathologic anatomy. J Pediatr Orthop 2000;20:812-816.

17. Gordon EJ, Schoenecker PL. Surgical treatment of congenital

dislo-cation of the patella. J Pediatr Orthop 1999;19:260-264.

18. Hayes AG, Boudrieau RJ. Frequency and distribution of medial and

lateral patellar luxation in dogs: 124 cases (1982-1992). J Am Vet Med Assoc 1994;205:716-720.

19. Harari J. Treatments for patellar luxations in dogs and cats.

Proceedings, 57th Ann Meeting, Am Anim Hosp Assoc 1990:287-288.

10. Willauer CC, Vasseur PB. Clinical results of surgical correction of medial luxation of the patella in dogs. Vet Surg 1987;16:31-36. 11. Remedios AM, Basher AP, Runyon CL, et al. Medial patellar

luxa-tion in 16 large dogs: a retrospective study. Vet Surg 1992;21:5-9. 12. Trotter E. Medial patellar luxation in the dog. Compend Contin Educ

Pract Vet 1980;2:58-66.

13. Hulse DA, Johnson AL. Medial patellar luxation. In: Fossum T, ed. Small Animal Surgery. St. Louis: Mosby-Year Book, 1997:976-983. 14. Evans HE. Arthrology. In: Evans HE, ed. Miller’s Anatomy of the

Dog. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1993:252.

15. Hulse DA. Medial patellar luxation in the dog. In: Bojrab MJ, ed. Disease Mechanisms in Small Animal Surgery. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lea and Febiger, 1993:808-817.

16. Roush JK. Canine patellar luxation. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 1993;23:855-868.

17. Arnoczky SP, Tarvin GB. Surgical repair of patellar luxations and fractures. In: Bojrab MJ, ed. Current Techniques in Small Animal Surgery. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins, 1998:1237-1244. 18. Piermattei DL, Flo GL. The stifle joint. In: Brinker, Piermattei, and

Flo’s Handbook of Small Animal Orthopedics and Fracture Repair. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1997:516-581.

19. Whitney WO. Arthroscopically assisted surgery of the stifle joint. In: Beale BS, Hulse DA, Schulz KS, et al., eds. Small Animal

Arthroscopy. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2003:117-157. 20. Merchant AC, Mercer RL, Jacobsen RH, et al. Roentgenographic

analysis of patellofemoral congruence. J Bone Joint Surg 1974;56(A):1391-1396.

21. Polousky JD, Hedman TP, Vangsness CT. Electrosurgical methods for arthroscopic menisectomy: a review of the literature. Arthroscopy 2000;16:813-821.

22. Yan L, Edwards RB, Kalscheur VL, et al. Effect of bipolar radiofre-quency energy on human articular cartilage: comparison of confocal laser microscopy and light microscopy. Arthroscopy 2001;17:117-123.

23. Edwards RB, Lu Y, Rodriguez E, et al. Thermometric determination of cartilage matrix temperatures during thermal chondroplasty: com-parison of bipolar and monopolar radiofrequency devices.

Arthroscopy 2002;18:339-346.

24. Medvecky MJ, Ong BC, Rokito AS, et al. Thermal capsular shrink-age: basic science and clinical applications. Arthroscopy

2001;17:624-635.

25. Obrzut SL, Hecht P, Hayashi K, et al. The effect of radiofrequency energy on the length and temperature properties of the glenohumeral joint capsule. Arthroscopy 1998;14:395-400.

26. Lopez MJ, Hayashi K, Fanton GS, et al. The effect of radiofrequency energy on the ultrastructure of joint capsular collagen. Arthroscopy 1998;14:495-501.

27. Nagaoka K, Orima H, Fujita M, et al. A new surgical method for canine congenital patellar luxation. J Vet Med Sci 1995;57:105-109. 28. Ticer JW. Radiographic Techniques in Small Animal Practice.