_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

*Corresponding author: E-mail: aichabentekaya@gmail.com;

www.sciencedomain.org

Neuropathic Pain in Patients with Sciatica:

Prevalence and Related Factors

Ben Tekaya Aicha

1*, Tekaya Rawdha

1, Mahmoud Ines

1, Sahli Hana

2,

Saidane Olfa

1, Zaghdani Imen

1and Abdelmoula Leila

11

Department of Rheumatology, Charles Nicolle Hospital, Tunis, Tunisia.

2

Department of Rheumatology, Mohamed Taher Al Maamouri Hospital, Nabeul, Tunisia.

Authors’ contributions

This work was carried out in collaboration between all authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Article Information

DOI: 10.9734/BJMMR/2016/24688

Editor(s):

(1) Vijay K Sharma, Division of Neurology, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, National University Hospital, Singapore.

Reviewers:

(1) Dariusz Szarek, Wroclaw Medical University, Wroclaw, Poland. (2)Tarush Rustagi, Topiwala National Medical College & B.Y.L. Nair Hospital, Mumbai, India. Complete Peer review History:http://sciencedomain.org/review-history/13835

Received 29th January 2016 Accepted 13th March 2016 Published 24th March 2016

ABSTRACT

Aim: To assess the prevalence of neuropathic pain (NP) in patients with sciatica and to determine the associated factors with increased incidence of neuropathic component in sciatica.

Methods: A cross-sectional study enrolled 80 patients with sciatica from a rheumatology outpatient Hospital. Pain severity was measured using the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS). The prevalence of NP was assessed according to the Douleur Neuropathique 4 (DN4). Statistical analysis was performed to find the factors closely related with NP.

Results: A total of 70% of the participants were classified as having NP. The DN4 score≥4 was not

significantly correlated with VAS, but was significantly associated with gender (sex ratio=0.9; p=0,013), low educational level (p=0,008), illiteracy (p=0,012), chronic disease (p=0,019) and facet joint osteoarthritis (p=0,06). In multivariate logistic regression analysis, only chronicity of the disease remained an independent factor associated with NP in sciatica (OR=5,8).

Conclusion: In the present study, NP was a major contributor to sciatica and the DN4 scale was a practical and rapidly administered screening tool for distinguishing the relative contributions of neuropathic component. The knowledge of the associated factors with NP in sciatica may improve the management of NP when these factors can be modified and targeted for treatment.

Keywords: Sciatica; neuropathic pain; douleur neuropathique 4.

1. INTRODUCTION

Neuropathic pain (NP) occurs as a result of lesion or disease affecting the somatosensory nervous system and is present in a diverse set of peripheral and central pathologies [1]. NP is associated with more severe pain for patients than nociceptive pain with suffering, disability, impaired health-related quality of life and increased health care cost [2]. Thus, early identification of NP is crucial, as it requires targeted management [3]. Screening tools have been developed in an attempt to facilitate the diagnosis of NP. The Douleur Neuropathique 4 (DN4) was the most universally well performing screening tool, showing reasonable accuracy in all patient populations in which it was assessed except those with failed back surgery syndrome (FBSS) [4]. An exemplary condition provoking mixed pain is sciatica, including both nociceptive and neuropathic components. However, nociceptive component was more considered than neuropathic component in patients with sciatica. Therefore, we conducted a cross-sectional study to assess the prevalence of NP component and to investigate the correlations between the DN4 and epidemiological, clinical and paraclinical parameters in patients suffering of sciatica.

2. METHODS

This cross-sectional study enrolled patients who were admitted to the rheumatology outpatient in Charles Nicolle Hospital with sciatica. The study was approved by the Hospital local Ethics Committee, and informed consent was obtained from all subjects. Participants were recruited over a seven month period. Exclusion criteria were: symptomatic sciatica (caused by other conditions such as tumors, infections, or inflammatory diseases), spinal cord compression/injury pain, previous surgery for the lower back, psychiatric disorders and any existing systemic or central conditions (eg, cancer, diabetes, multiple sclerosis, stroke) which might produce radicular syndrome. Socio-demographic data including age, gender, marital status, number of children, education level, and occupation were recorded. Clinical data including path of sciatica (L5/S1 or poorly systematized), side of sciatica and disease duration in months were determined. Radiographic analysis of the lumbar spine focused on: intervertebral lumbar disc disease, lumbar stenosis, facet joint osteoarthritis and

spondylolisthesis. Details of reeducation and pharmacological treatments were mentioned. Medications included Non steroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs), muscle relaxants, vitamin therapy and epidural steroid injection were recorded.

2.1 Measurement of Variables

The severity of pain was measured using the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS; 0–10 mm). The presence of NP was established by using the DN-4 questionnaire. This questionnaire contains seven items relating to symptoms of pain (e.g. sensations of burning, electric shock, painful cold, tingling, pins and needles, numbness, itching) and three items relating to the physical examination, i.e. hypoesthesia to brushing, hypoesthesia to fine tactile stimuli and brush-evoked allodynia. Each element is scored as present (1) or absent (0). A score of 4 or higher in this test was judged as representing NP.

2.2 Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) for Windows, version 11.5. A descriptive analysis was conducted in order to present the socio-demographic and clinical variables of the study. The quantitative variables were described in terms of the mean and standard deviation (SD), whereas the categorical variables were summarized by calculating the frequencies and or the percentages. The one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was used for comparisons of parametric continuous data. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used for nonparametric continuous data. The chi-square test of Pearson was used to compare categorical variables between the groups, and in case of non-validity, the Fisher exact test bilateral. Univariate analysis was performed to identify independent predictors of the NP (DN4≥4/10). Multivariate logistic

regression analysis was performed to find the independent factors associated with NP in sciatica. In all cases, statistical significance was set at a p value of <0.05.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Patient’s Characteristics

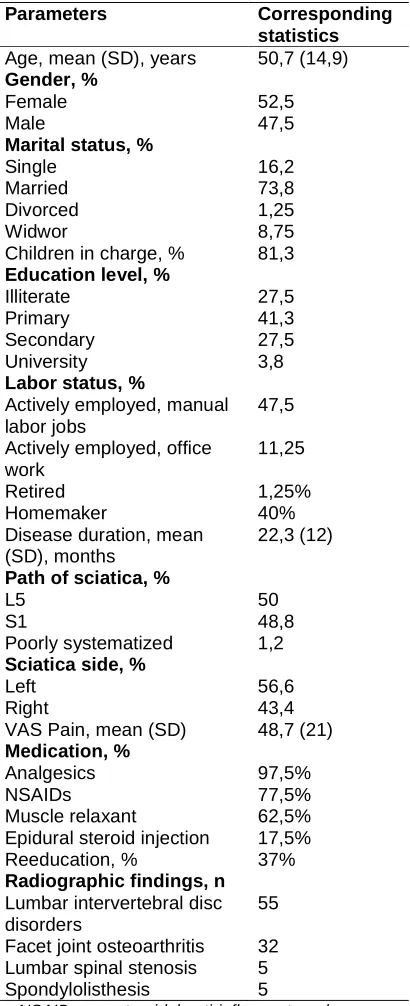

years. The patients with an age of 40–69 constituted 66,25% of the entire participants. Patients over 70 years old constituted 11,25%; 52,5% were workers and 40% were jobless and the cause was independent of sciatica. Seventy two percent completed at least a primary education while 27,5% did not receive primary education. The majority of patients were married (73,8%) and have children in charge (81,3%). The mean illness duration was 22,3 (±12) months, with 88,7% patients having chronic sciatica pain for at least 3 months. The mean score on VAS pain was 48,7 mm (±21). Radiographic investigations showed lumbar disc disease in 55 cases, facet joint osteoarthritis in 32 cases, lumbar stenosis in 5 cases and spondylolisthesis in 5 cases. Seventeen patients have two radiographic abnormalities; the most frequent was the association between lumbar disc disease and lumbar stenosis. More than half of the patients included in the study were taking analgesics, NSAIDs, muscle relaxant (97,5%, 77,5%, 62,5%, respectively). Epidural steroid injection was proposed in 17,5%. Up to 37% of the participants performed reeducation. Table 1 summarized the patients’ socio-demographic, clinical characteristics and radiographic results.

3.2 Assessment of NP and Correlations with Patients’ Characteristics

The mean (SD) score by the study participants on the DN4 was 4,41 (±1,8). The prevalence of NP based on the DN4 was 70% of the patients included. The most common items checked were: pins and needles (item4), tingling (item5) and numbness (item6). Among the three items relating to the physical examination (items 8, 9 and 10) hypoesthesia to fine tactile stimuli was the most frequent. A DN4 score≥4 was

significantly associated with female (p=0,013), low educational level (p=0,008), illiteracy (p=0,012), chronic disease (p=0,019) and facet joint osteoarthritis (p=0,06). However, All these variables (age, labor status, type of work, marital status, number of children in charge, path of sciatica, side of sciatica, VAS pain, current

treatment) were not significantly associated with higher DN4≥4. Both groups with and without

NP have benefited from reeducation, but were not influenced by the presence of NP

(p=0,313).

In multivariate logistic regression analysis, only chronic disease appears to be an independent factor associated with NP in sciatica (OR=5,8).

Table 1. Patients’ characteristics and spinal disorders (n = 80)

Parameters Corresponding

statistics Age, mean (SD), years 50,7 (14,9) Gender, %

Female 52,5

Male 47,5

Marital status, %

Single 16,2

Married 73,8

Divorced 1,25

Widwor 8,75

Children in charge, % 81,3 Education level, %

Illiterate 27,5

Primary 41,3

Secondary 27,5

University 3,8

Labor status, %

Actively employed, manual labor jobs

47,5

Actively employed, office work

11,25

Retired 1,25%

Homemaker 40%

Disease duration, mean (SD), months

22,3 (12)

Path of sciatica, %

L5 50

S1 48,8

Poorly systematized 1,2 Sciatica side, %

Left 56,6

Right 43,4

VAS Pain, mean (SD) 48,7 (21) Medication, %

Analgesics 97,5%

NSAIDs 77,5%

Muscle relaxant 62,5%

Epidural steroid injection 17,5% Reeducation, % 37% Radiographic findings, n

Lumbar intervertebral disc disorders

55

Facet joint osteoarthritis 32 Lumbar spinal stenosis 5

Spondylolisthesis 5

NSAIDs: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, n: number, SD: standard deviation, VAS: visual analogue

scale

4. DISCUSSION

outpatient rheumatology department in a tertiary general hospital in Tunisia, therefore, the sample was representative to whole region. A validated questionnaire (DN4) was used to assess NP. Besides, exclusion of patients with FBSS had avoided any bias in the assessment of pain.

However, the mean VAS pain was low. It can be partly explained by the higher percentage of

low educational level of the sample. Thus, patients failed to appreciate the severity of pain and distinguish between nociceptive pain and NP.

Nevertheless, some limitations have to be considered. The primary limitation of the present study was its cross-sectional study design, which provided only correlation findings. It is difficult to discern whether the burden of NP is a consequence of the adverse impact of the disease-related problems, or other factors associated with sciatica. Second, the number of participants was relatively small. However it has allowed us statistically reliable results, but studies with larger groups should be considered. A methodological problem was the third limit; the inclusion of patients from a tertiary general hospital underestimated the prevalence of NP in patients with acute sciatica.

Pain was defined as an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage or described in terms of such damage [5]. Different pathophysiological mechanisms are thought to operate in sciatica. In fact, sciatica was variously considered to reflect the activation of nociceptive sensory endings (normal or sensitized by inflammation), or a neuropathic process in the peripheral nervous

system [6]. According to the

nociception/inflammation hypothesis, sciatica pain results from electrical impulses originating in sensory endings in deep peripheral tissues (eg, disc, annulus, muscle, joints, ligaments). These tissues are innervated primarily by nerve branches of the dorsal ramus [6,7]. The neuropathy hypothesis, in contrast, holds that leg pain is a consequence of ectopic impulse discharge (ectopia) generated paraspinally in compressed or irritated ventral ramus afferents that is, in sensory axons of the spinal nerves and roots that innervate the leg, and/or in their cell bodies in the corresponding dorsal root ganglia. Thus, NP in sciatica may be caused by mechanical compression of the nerve root (mechanical neuropathic root pain), or by action of inflammatory mediators (inflammatory neuropathic root pain) originating from the

degenerative disc even without any mechanical compression [8,9]. To this hypothesis, sciatica pain may have 2 causes: neuropathic ectopia in injured dorsal ramus afferents or sensitized nociceptor endings in deep back tissues. In most patients, both mechanisms probably contribute, yielding qualitatively different pain sensations with different secondary consequences. Diagnosis of NP typically consists of a thorough history together with an extensive neurosensory examination. In fact, NP pain is generally identified by its spontaneous pain and evoked pain. Spontaneous pain could occur so continuous or intermittent and paroxysmal and may include: burning, prickling, tingling, itching, electric shock–like and stabbing sensations. Evoked pain was described as an exaggerated pain provoked by tactile or thermal stimuli: ‘allodynia’ is a pain induced by light touch or moderate thermal stimuli and ‘hyperalgesia’ refer to particularly severe pain elicited by normally mild nociceptive stimuli. An individual with NP may exhibit all or only a few of these components of NP. Patients describe being especially sensitive in the area of pain.

NP is associated with several heterogeneous rheumatic diseases, however underestimated since often intertwined with nociceptive pain. They correspond more to peripheral NP. The main pathologies in question are: chronic low back pain, chronic radicular pain (sciatica, cervicobrachial neuralgia), spinal cord injury, FBSS, pathologies with sympathetic induced pain, tunnel syndromes, autoimmune inflammatory polyneuropathies and complex regional pain syndrome Type I and II.

In our sample, the prevalence of NP sciatica was 70%. These results were higher than the reported prevalence of NP component in sciatica which was estimated between 17 and 66% [14-21]. Variability in results may arise from different screening tools used for assessing NP, demographic diversities, or translation imperfections in different language versions of the NP questionnaires. The substantial higher scoring for NP in our cohort can be partly explained by the fact that patients were selected from a third line hospital including severe cases. Our choice of the screening tool for NP fell on DN4 to its reliability, sensitivity and sensibility in detecting NP [22].

There is no recognized objective gold standard for assessing NP. Screening tools have been developed in an attempt to facilitate the diagnosis of NP. These strategies include: the DN4, the LANSS, the Pain Detect and the Neuropathic Pain Questionnaire [23-27]. Screening tools are comprised of an interview component and, in some cases, the addition of a brief bedside clinical assessment. Many of these tools have been translated for application in other languages and populations. A systematic review assessed the diagnostic accuracy of methods of assessing NP in adults found that the DN4 was the most universally well performing screening tool, showing reasonable accuracy (sensitivity: 76 to 100%; specificity: up to 92%) in all patient populations in which it was assessed except those with FBSS (sensitivity: 62%; specificity: 44%) [4]. In addition, the Special Interest Group on Neuropathic Pain (NeuPSIG) of the IASP has set out a grading system that has been used to guide clinical assessment and diagnosis. This approach involves multiple steps including obtaining a clinical history of pain, assessing the neuroanatomical plausibility of pain, using sensory assessments to confirm nervous system involvement, and running diagnostic tests to confirm nervous system lesions or disease [28].

In our study, the female gender was found to be correlated with NP in sciatica as it has been reported in others studies [29,30]. When looking at other characteristics, patients in our cohort have higher age and lower educational level. Advanced age was reported to be associated with NP in sciatica [15,30]. In harmony with Si Young Park et al. [20], we haven’t found correlation between NP and advanced age. However, low educational level and illiteracy were significantly associated with the presence of NP in our sample. Previous national

epidemiological investigation in United Kingdom has showed that low educational attainment and joblessness were independent risk factor for chronic NP [11]. Regarding the disease duration, our results are in line with those described by Yamashita T et al. [15] and Kyung Hyun Kim et al. [29] who reported that chronic disease duration was an independent risk factor for NP. There are some controversies about the correlation between VAS pain and the NP component in sciatica. While Tutoglu A et al. [31] found no evidence of any associated factor for sciatica with NP, others confirmed that incidence of NP tended to increase with increasing severity of pain [15,17,20,21,29]. In our study, VAS pain was not correlated with the presence of NP. Recently, there has been growing interest in the role of psychological factors in contributing to the development of NP, and the impact of NP on the quality of life in patients with low back pain and leg pain. As previously reported in the literature, increased neuropathic component in sciatica patients was significantly associated with elevated levels of depression and anxiety [21,31,32]. Furthermore, several reports confirmed that worse quality of life was significantly associated with NP in sciatica [17-21,29,33]. Unfortunately, psychological factor and quality of life didn’t be assessed in our study. A recent systematic review, which aim was to provide a systematic overview of predictors for persistent NP found three predictors for persistence of radicular NP: negative outcome expectancies, pain-related fear of movement, and passive pain coping [34]. Thereby, the knowledge of predictors and associated factors with NP in sciatica may improve the management of NP when these factors can be modified and targeted for treatment.

techniques such as nerve conduction studies, somatosensory evoked potentials, quantitative sensory testing and the laser evoked potentials [35,36].

Although NP is common in sciatica, treatment is difficult and is still a challenge. Thus, several consensus guidelines and recommendations have been established in pharmacotherapy for NP in adults [37,38]. A systematic review and meta-analysis based on the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) and revised recommendations of NeuPSIG has been recently published [38]. Authors demonstrated that tricyclic antidepressants, serotonin-noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor antidepressants (particularly duloxetine), pregabalin, gabapentin, gabapentin extended release and enacarbil have strong GRADE recommendations for use in NP and are proposed as first-line treatments. As for Gabapentin and pregabalin each bind to voltage-gated calcium channels at the α2-δ subunit and

inhibit neurotransmitter release. The results of a new paper point out the statistically significant improvements in pain-related sleep interference, pain, function, and health status relative to usual

treatments in patients with chronic low back pain and radicular pain suffering from NP treated

with pregabalin, already after 4 weeks [39]. Moreover, because many patients treated with a single efficacious medication do not obtain satisfactory pain relief, the guidelines emphasize that patients may benefit from use of combinations of efficacious NP medications. The results of Cochrane review of combination pharmacotherapy for the treatment of NP showed superior efficacy of two-drug combinations in multiple, good-quality studies [40]. However, combination pharmacotherapy may increase the risk of toxicity particularly when the combined drugs produce common adverse effects, thus practical use of analgesic drug combinations requires vigilant risk-benefit assessment during combination treatment. Patients with NP are also receptive to nonpharmacologic treatments. The benefit of including these types of therapies is their general lack of side effects and the ability to combine them with other nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic treatments without significant risk. Based on survey studies, the most commonly reported nonpharmacologic treatments tried for NP were: transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), psychological/cognitive interventions, massage or relaxation therapy, and acupuncture [41]. In the present study,

current treatment was not found to be significantly associated with NP, however no patients was treated with tricyclic antidepressants or pregabalin/gabapentin. Additional study is needed to assess whether DN4 score is predictive of treatment response when these drugs are used in NP associated with sciatica.

5. CONCLUSION

Given our results, NP is highly prevalent in patients with chronic sciatica according to the DN4. Female gender, low educational level and chronic disease duration were independent risk factors for increased incidence of NP in sciatica. Consequently, patients with these risks factors should benefit from screening. By using screening tools such as the DN4, it is possible to evaluate the involvement of NP at an early time point, which enables rheumatologists to implement a focused strategy to appropriate treatments targeting modifiable factors in high-risk patients and could help prevent its persistence. More extensive, longitudinal studies are needed to investigate other associated factors in the development of NP.

COMPETING INTERESTS

Authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

REFERENCES

1. Jensen TS, Baron R, Haanpää M, et al. A new definition of neuropathic pain. PAIN. 2011;152:2204–2205.

2. Doth AH, Hansson PT, Jensen MP, Taylor RS. The burden of neuropathic pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis of health utilities. PAIN. 2010;149:338–344. 3. Baron R, Binder A., Wasner G.

Neuropathic pain: diagnosis, pathophysio-logical mechanisms, and treatment. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:807–819.

4. Diagnostic methods for neuropathic pain: A review of diagnostic accuracy. Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. Ottawa; 2015.

6. Bogduk N. On the definitions and physiology of back pain, referred pain, and radicular pain. PAIN. 2009;147:17–19. 7. Hayashi K, Shiozawa S, Ozaki N,

Mizumura K, Graven-Nielsen T. Repeated intramuscular injections of nerve growth factor induced progressive muscle hyperalgesia, facilitated temporal summation, and expanded pain areas. PAIN. 2013;154:2344–2352.

8. Smart KM, Blake C, Staines A, Thacker M, Doody C. Mechanisms-based classifi-cations of musculoskeletal pain: Part 2 of 3: symptoms and signs of peripheral neuropathic pain in patients with low back (± leg) pain. Man Ther. 2012;17(4):345-351.

9. La Cesa S, Tamburin S, Tugnoli V, et al. How to diagnose neuropathic pain? The contribution from clinical examination, pain questionnaires and diagnostic tests. Neurol Sci. 2015;36(12):2169-2175. 10. Bouhassira D, Lantéri-Minet M, Attal N,

Laurent B, Touboul C. Prevalence of chronic pain with neuropathic charac-teristics in the general population. Pain. 2008;136(3):380-387.

11. Torrance N, Smith BH, Bennett MI, Lee AJ. The epidemiology of chronic pain of predominantly neuropathic origin. Results from a general population survey. J Pain. 2006;7(4):281-289.

12. van Hecke O, Austin SK, Khan RA, Smith BH, Torrance N. Neuropathic pain in the general population: A systematic review of epidemiological studies. Pain. 2014; 155(4):654-662.

13. Fishbain DA, Cole B, Lewis JE, Gao J. What is the evidence that neuropathic pain is present in chronic low back pain and soft tissue syndromes? An evidence-based structured review. Pain Med. 2014;15(1):4-15.

14. Walsh J, Rabey MI, Hall TM. Agreement and correlation between the self-report leeds assessment of neuropathic symptoms and signs and Douleur Neuropathique 4 Questions neuropathic pain screening tools in subjects with low back-related leg pain. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2012;35(3):196-202.

15. Yamashita T, Takahashi K, Yonenobu K, Kikuchi S. Prevalence of neuropathic pain in cases with chronic pain related to spinal disorders. J Orthop Sci. 2014;19(1):15-21.

16. Urban LM, MacNeil BJ. Diagnostic accuracy of the slump test for identifying neuropathic pain in the lower limb. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2015;45(8):596-603.

17. Hiyama A, Watanabe M, Katoh H, Sato M, Sakai D, Mochida J. Evaluation of quality of life and neuropathic pain in patients with low back pain using the Japanese Orthopedic Association Back Pain Evaluation Questionnaire. Eur Spine J. 2015;24(3):503-512.

18. Freynhagen R, Baron R, Tölle T, et al. Screening of neuropathic pain components in patients with chronic back pain associated with nerve root compression: A prospective observational pilot study (MIPORT). Curr Med Res Opin. 2006; 22(3):529-537.

19. Attal N, Perrot S, Fermanian J, Bouhassira D. The neuropathic components of chronic low back pain: A prospective multicenter study using the DN4 Questionnaire. J Pain. 2011;12(10):1080-1087.

20. Park SY, An HS, Moon SH, et al. Neuropathic pain components in patients with lumbar spinal stenosis. Yonsei Med J. 2015;56(4):1044-1050.

21. Beith ID, Kemp A, Kenyon J, Prout M, Chestnut TJ. Identifying neuropathic back and leg pain: A cross-sectional study. Pain. 2011;152(7):1511-1516.

22. Mathieson S, Maher CG, Terwee CB, Folly de Campos T, Lin CW. Neuropathic pain screening questionnaires have limited measurement properties. A systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68(8):957-966.

23. Freynhagen R, Baron R, Gockel U, Tolle TR. Pain DETECT: A new screening questionnaire to identify neuropathic components in patients with back pain. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22(10):1911– 1920.

24. Portenoy R. Development and testing of a neuropathic pain screening questionnaire: ID pain. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22:1555–1565.

25. Bennett M. LANSS pain scale: The leeds assessment of neuropathic symptoms and signs. PAIN. 2001;92:147-157.

diagnostic questionnaire (DN4). Pain. 2005;114:29-36.

27. Krause SJ, Backonja MM. Development of a neuropathic pain questionnaire. Clin J Pain. 2003;19:306-314.

28. Treede RD, Jensen TS, Campbell JN, et al. Neuropathic pain: redefinition and a grading system for clinical and research purposes. Neurology. 2008;70:1630-1635. 29. Kim KH, Moon SH, Hwang CJ, Cho YE.

Prevalence of neuropathic pain in patients scheduled for lumbar spine surgery: Nationwide, Multicenter, Prospective Study. Pain Physician. 2015;18(5):889-897.

30. El Sissi W, Arnaout A, Chaarani MW, Fouad M, El Assuity W, Zalzala M, et al. Prevalence of neuropathic pain among patients with chronic low-back pain in the Arabian Gulf Region assessed using the leeds assessment of neuropathic symptoms and signs pain scale. J Int Med Res.2010;38(6):2135-2145.

31. Tutoglu A, Boyaci A, Karababa IF, Koca I, Kaya E, Kucuk A, et al. Psychological defensive profile of sciatica patients with neuropathic pain and its relationship to quality of life. Z Rheumatol 2015;74(7): 646-651.

32. Uher T, Bob P. Neuropathic pain, depressive symptoms, and C-reactive protein in sciatica patients. Int J Neurosci. 2013;123(3):204-208.

33. Morsø L, Kent PM, Albert HB. Are self-reported pain characteristics, classified using the Pain DETECT questionnaire, predictive of outcome in people with low back pain and associated leg pain? Clin J Pain.2011;27(6):535-541.

34. Boogaard S, Heymans MW, de Vet HC, Peters ML, Loer SA, Zuurmond WW,et al. Predictors of persistent neuropathic pain - A systematic review. Pain Physician. 2015;18(5):433-457.

35. Marchettini P, Marangoni C, Lacerenza M, Formaglio F. The Lindblom roller. Eur J Pain. 2009;7(4):359–364.

36. Cruccu G, Aminoff MJ, Curio G, Guerit JM, Kakigi R, Mauguiere F, et al. Recommendations for the clinical use of somatosensory-evoked potentials. Clin Neurophysiol. 2008;119(8):1705–1738. 37. Robert H. Dworkin, Alec B. O'Connor,et al.

Recommendations for the pharmacological management of neuropathic pain: An overview and literature update. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85:3-14.

38. Finnerup NB, Attal N, Haroutounian S, et al. Pharmacotherapy for neuropathic pain in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14(2):162-173.

39. Taguchi T, Igarashi A, Watt S, et al. Effectiveness of pregabalin for the treatment of chronic low back pain with accompanying lower limb pain (neuropathic component): A non-interventional study in Japan. J Pain Res. 2015;8:487-497.

40. Chaparro LE, Wiffen PJ, Moore RA, Gilron I. Combination pharmacotherapy for the treatment of neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012; 11;7:CD008943.

41. Guastella V, Mick G, Laurent B. Non pharmacologic treatment of neuropathic pain. Presse Med. 2008;37:354-357. _________________________________________________________________________________ © 2016 Aicha et al.; This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Peer-review history: